Abstract

Variants in the gap junction beta-2 (GJB2) gene are the most common cause of hereditary hearing impairment. However, how GJB2 variants lead to local physicochemical and structural changes in the hexameric ion channels of connexin 26 (Cx26), resulting in hearing impairment, remains elusive. In this study, using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, we showed that detached inner-wall N-terminal “plugs” aggregated to reduce the channel ion flow in a highly prevalent V37I variant in humans. To examine the predictive ability of the computational platform, an artificial mutant, V37M, of which the effect was previously unknown in hearing loss, was created. Microsecond simulations showed that homo-hexameric V37M Cx26 hemichannels had an abnormal affinity between the inner edge and N-termini to block the narrower side of the cone-shaped Cx26, while the most stable hetero-hexameric channels did not. From the perspective of the conformational energetics of WT and variant Cx26 hexamers, we propose that unaffected carriers could result from a conformational predominance of the WT and pore-shrinkage-incapable hetero-hexamers, while mice with homozygous variants can only harbor an unstable and dysfunctional N-termini-blocking V37M homo-hexamer. Consistent with these predictions, homozygous V37M transgenic mice exhibited apparent hearing loss, but not their heterozygous counterparts, indicating a recessive inheritance mode. Reduced channel conductivity was found in Gjb2V37M/V37M outer sulcus and Claudius cells but not in Gjb2WT/WT cells. We view that the current computational platform could serve as an assessment tool for the pathogenesis and inheritance of GJB2-related hearing impairments and other diseases caused by connexin dysfunction.

Keywords: Hereditary hearing impairment, Cx26, Molecular dynamics simulation, Ion channel, Transgenic mice

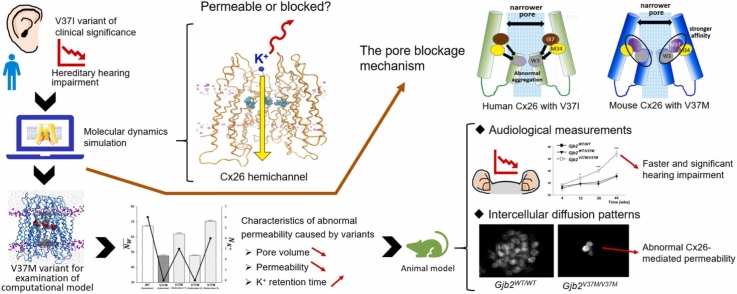

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

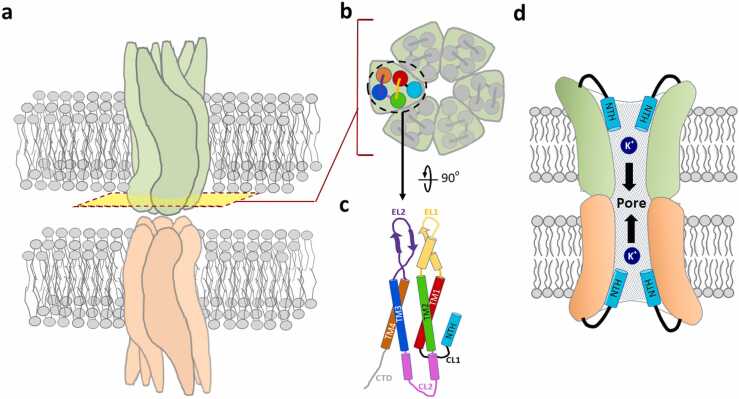

Gap junctions (GJs), which are formed by two hemichannels assembled from hexameric connexin subunits (Figs. 1a and 1b), are crucial for electrolyte and metabolite homeostasis in the mammalian inner ear [1]. The connexin 26 (Cx26) channel protein, encoded by gap junction beta-2 (GJB2), is the most important connexin in the inner ear. The tertiary structure of the Cx26 monomer (Fig. 1c) is characterized by four transmembrane domains (TM1–4), the N-terminal helix (NTH), and other connecting cytoplasmic and extracellular loops (CLs/ELs), and the inner pore inside the gap junctional channel is responsible for the intercellular transport of molecules, including the transfer of potassium ions (Fig. 1d). GJB2 variants are the most common genetic cause of sensorineural hearing impairment (SNHI) in humans, and can be inherited in autosomal recessive and dominant modes [2], [3]. Expressed in the supporting cells of the organ of Corti, stria vascularis, spiral ligament, and spiral limbus [4], [5], [6] in the cochlea, Cx26 has been implicated in potassium recycling [7], [8], [9], intercellular signaling [10], and the development of the organ of Corti [11], [12].

Fig. 1.

Representative constitution of gap junctional channel formed by oligomerizedGJB2-encoded protein Cx26 with multiple domains in the monomer. (a) Gap-junctional channel composed of head-to-head docking of two hexameric Cx26 hemichannels. (b) Sectional view of hemichannel consisting of six monomers with one N-terminal helix (NTH) and four transmembrane (TM) domains. (c) The side view of Cx26 monomer with multiple domains. (CL: cytoplasmic loop; EL: extracellular loop; CTD: C-terminal domain) (d) Side view of the inner pore in the gap junctional channel responsible for the transfer of potassium ions or other biological molecules.

To date, > 400 pathogenic GJB2 variants have been recorded in the Deafness Variation Database (http://deafnessvariationdatabase.org/) [13] as listed in Tables S1 and S2, and missense variants comprising 2/3 of them are mainly related to the recessively inherited SNHI; however, they are sporadically reported as dominantly inherited variants (e.g. R75Q [14], R143Q [15], and others [16]). The phenotypic spectrum of GJB2-related SNHI is diverse, and its severity is highly related to the genotypes [17], [18]. For example, genotypes with bi-allelic nonsense variants (e.g., frameshift or truncating variants) are associated with severe-to-profound SNHI in early-onset patients. In contrast, genotypes with at least one allele of a non-truncating variant are associated with milder SNHI [3], [17], [18]. Among these variants, the V37I (c .109 G>A) variant is of particular interest because of its high prevalence and enigmatic pathogenicity. This variant is prevalent in the normal Asian population, with an allele frequency of 8.35% (gnomAD, v2.1.1) [19], ranging from ∼1.0% in Japanese [20] and Korean [21], 4.3% in Thai [22], and 6.2–8.9% in Han Chinese populations [23], [24]. At least five million Asian people are estimated to be homozygous for V37I [25], indicating that V37I might be the single most common deafness-associated variant worldwide. Owing to its high allele frequency, V37I was previously regarded as a benign polymorphism [22], [24]. However, subsequent studies have indicated that V37I might be a recessive pathogenic variant contributing to mild-to-moderate SNHI with incomplete penetrance [3], [21], [23], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30]. In a recent longitudinal study, we described the progressive nature of SNHI in subjects homozygous for V37I; however, hearing levels varied remarkably among individuals [17], [31].

Changes in the amino acid residues of Cx26 may confer physicochemical [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37] effects on the gating of gap junction channels. In silico molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have been applied to investigate the structural effects of several missense GJB2 variants, including M34T [34], T8M [38], G12R [39], and N14K [40], on the gating mechanisms of the Cx26 hemichannel (see Table S3 for more details). Biochemical assays of V37I revealed reduced permeability of gap junctions [41], [42], [43], suggesting that V37I may exert structural effects implicated in the plug-mediated gating mechanism similar to M34T [37], [44]; however, the detailed mechanisms underlying V37I-mediated reduced permeability remain unclear. Spatially, residue 37 (Res 37) is located in the middle of 1st transmembrane domain (TM1, residue 21–40) and adjacent to the NTH (residue 1–13) and CL1 (residue 14–20), wherein the TM1-CL1-NTH domain constitutes the major component of the inner edge of the pore. Therefore, it is of interest to clarify how V37I exerts its effects on Res 37 and leads to conformational changes in Cx26.

MD simulations can potentially predict the functionality of other missense variants of Cx26. To test this hypothesis, an in silico model was constructed using a mouse-based Cx26 homolog with a novel mutant at Res 37, namely V37M, in homo-hexameric (hereafter called homomeric) and hetero-hexameric (hereafter called heteromeric) arrangements. There are no clinical data on the pathogenicity of the V37M variant to confound or bias our MD-based prediction. Our simulations showed normal functional Cx26 channels for Gjb2WT/WT and Gjb2WT/V37M, but not Gjb2V37M/V37M, which was confirmed by hearing loss/noise vulnerability tests in homozygous V37M transgenic mice. The reduced molecular conductivity of Gjb2V37M/V37M was confirmed using in vitro dye transport assays.

2. Results

2.1. V37I in human in silico Cx26 hemichannels reveals reduced pore volume and potassium permeability

In this study, we used a coarse-grained molecular dynamics (CG-MD) simulation to investigate abnormal gating mechanisms influenced by the missense variant V37I. CG-MD simulations characterized by a simplified representation of the all-atom (AA) model have the advantage of efficiently performing longer simulations (generally tens of microseconds in CG-MD versus hundreds of nanoseconds in AA-MD simulation) and consequently exploring larger conformational changes than AA models [45]. The CG force field Martini [46] has been developed over 20 years and has been widely applied in academic research [47], where studies have demonstrated successful CG simulations using Martini force field to reproduce experimental observables [48], [49]. Martini 3 contains a separate bead type optimized for water, and different bead types to define the behavior of charged species like monovalent ions [47]. The ability of Martini in capturing the interaction of proteins with water and ions have been exemplified by studies on adenosine A2A receptor, Fragaceatoxin C (FraC) nanopore and cellulose-binding domain [47]. Thus, a standard CG model based on the crystal structure of the human Cx26 hemichannel (hereafter called “hCx26”; PDBID: 2ZW3 [50]) was first constructed, which was embedded into the 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC) bilayer and solvated under physiological conditions that mimicked the endolymph of the cochlea (Fig. 2a; “WT-hCx26”) and its mutant with the homomeric V37I variant (“V37I-hCx26”) (Fig. 2b).

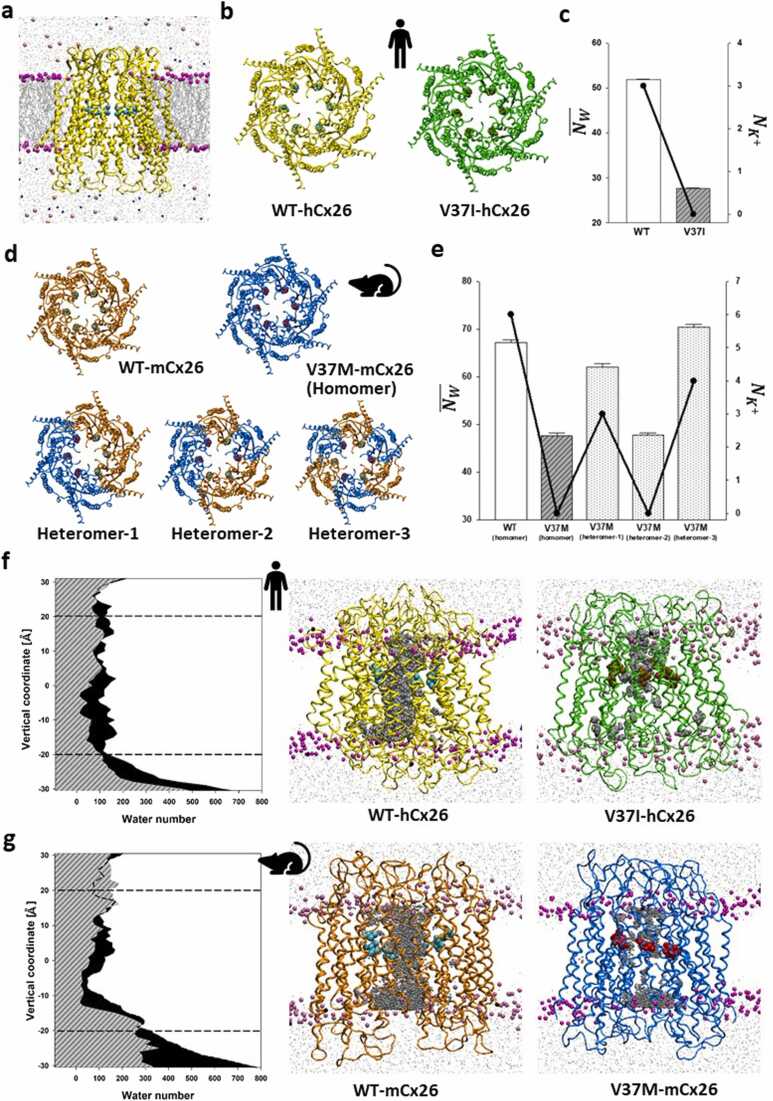

Fig. 2.

Overview of membrane-embedded Cx26 hemichannel and changes in pore volume, potassium ion permeability, and water channels caused by Res37 variants in human and mouse Cx26 models. (a) Side view of the membrane-embedded human wild-type Cx26 hemichannel [WT-hCx26 (yellow) with hexameric Val37 (cyan)] (violet: choline groups of the DOPC membrane; indigo: potassium ions; pink: chloride ions). (b and d) Top views of WT-hCx26 and its homo-V37I mutant [V37I-hCx26 (green) with hexameric Ile37 (ochre)], and the homologous wild type mouse model [WT-mCx26 (orange) with hexameric Val37 (cyan)] and its homo-V37M mutants [V37M-mCx26 (blue) with hexameric Met37 (red)] and heteromeric counterparts (heteromers-1 to −3 of V37M-mCx26 at an equal ratio of 3:3 under different arrangements of WT and V37M monomers). (c and e) Mixed graphs of (as bar plots along the left axis) and (as line charts along the right axis) for the series of hCx26 and mCx26 models, respectively. (f and g) Left panel: area plots of accumulated water distribution in wild-type (in black) and homomeric mutants (dashed gray) of hCx26 and mCx26 models, respectively, during equilibrated 4 μs simulations along the membrane normal of the waterbox (dashed lines: average vertical coordinates of choline groups on both leaflets of the DOPC membrane in the waterbox). Right panel: accumulated trajectories of water molecules inside the pore (in gray) during the equilibrated 4 μs of molecular dynamic (MD) simulations in wild-type and homomeric mutants of hCx26 and mCx26 models, respectively.

Four microsecond-long CG-MD simulations were performed to investigate the conformations of WT-hCx26 and V37I-hCx26 using two metrics: pore volume (inner channel space), potassium permeability. The water channeling of V37I-hCx26, represented by the average water number inside the hemichannel (), was found reduced as compared with the wild-type (WT vs. mutant was 51.76 ± 0.34 vs. 26.52 ± 0.22 water molecules, per Student’s t-test, p < 0.001, see Fig. 2c and Table 1). For the potassium permeability, as defined by the number of potassium ions that passed through the pore during the simulations (), three ions passed through the pore of WT-hCx26, whereas no potassium ions passed through V37I-hCx26 (see line chart of Fig. 2c and Table 1). The difference in potassium permeabilities between WT-hCx26 and V37I-hCx26 is further illustrated in Supplementary Videos 1 and 2, respectively. These results indicate that the V37I variant could lead to the dysfunction of human Cx26 through a reduced pore volume, and impaired permeability of potassium ions in the hemichannel. The same trend was also observed in the replication of the simulation between WT-hCx26 and V37I-hCx26 (55.45 ± 0.49 vs. 45.00 ± 0.42 in and 9 vs. 1 in ) as shown in Figs. S1a and S1b. The findings from the MD simulations are consistent with the reduced permeability observed in previous biochemical cell line studies of Cx26 with V37I [41], [42], [43].

Table 1.

Average water number inside the channel () and potassium permeability () among various hCx26 or mCx26 hemichannels.

| Cx26 hemichannel | a | b |

|---|---|---|

| WT-hCx26 | 51.83 ± 0.19 | 3 |

| V37I-hCx26 | 27.62 ± 0.12 * ** | 0 |

| WT-mCx26 | 67.22 ± 0.60 | 6 |

| V37M-mCx26 homomer | 47.67 ± 0.54 * ** | 0 |

| V37M-mCx26 heteromer-1 | 62.09 ± 0.68 * ** | 3 |

| V37M-mCx26 heteromer-2 | 47.84 ± 0.35 * ** | 0 |

| V37M-mCx26 heteromer-3 | 70.50 ± 0.60 * ** | 4 |

| Spearman ρc | 0.85 |

Average water number inside the hemichannel during the 4 μs simulation (mean ± SEM; ***: p < 0.001 of Student’s t-test, where each mutant is compared to the wild type);

potassium permeability, defined as the frequency of potassium ions passing through the hemichannel during the 4 μs simulation.

Spearman correlation coefficients of and for various mCx26 oligomers.

Supplementary material related to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.csbj.2023.11.026.

The following is the Supplementary material related to this article Video S1..

The following is the Supplementary material related to this article Video S2..

2.2. V37M in mouse in silico Cx26 hemichannel reveals impaired channeling from homomeric assembly and not from heteromeric counterparts

We sought to develop a predictive platform coupled with experimental validation using animal model. Irrespective of the lack of an experimentally determined mouse Cx26 structure, a homology structural model of mouse Cx26 (mCx26) was constructed in silico using SWISS-MODEL [51] based on the crystal structure of hCx26 (“WT-mCx26”) given the high (93%) amino acid sequence identity shared between hCx26 and mCx26 (Fig. 2d). We first chose the V37I variant, whose homozygous genotype had been confirmed to cause SNHI in murine models [52], to construct a mouse mutant structural model (V37I-mCx26 in Fig. S2). After four microseconds of CG-MD simulations based on the conditions mentioned above for human models, compared with WT-mCx26, V37I-mCx26 demonstrated pore blockage (67.22 ± 0.6 vs. 51.69 ± 0.66 for ) and reduced permeability (6 vs. 0 for ), which was consistent with previously reported experimental results [52].

To further examine the predictive ability of our MD models, we chose another missense variant, V37M, as our main research target. The Met residue is characterized by its high physicochemical similarity with Val based on BLOSUM62 matrix scores [53] (i.e. highly frequent substitutions between Val and Met in organism revolutions), and the V37M variant has not been reported in SNHI-related clinical studies; therefore, its influence on the functionality of hemichannels remains unknown. Our computer model from this study could be used to identify subtle differences prior to experimental confirmation through animal studies. After the same pipeline of model construction for V37M variants in the mouse model (“V37M-mCx26”) and following CG-MD simulation over the same timescale as indicated above, V37M-mCx26 demonstrated pore blockage and therefore reduced permeability compared with WT-mCx26, where WT-mCx26 vs. V37M-mCx26 for was 67.22 ± 0.6 vs. 47.67 ± 0.54 water molecules, for was 6 vs. 0 potassium ions (see Table 1 for definition). As illustrated in Supplementary Videos 3 and 4, V37M-mCx26 demonstrated obstruction of potassium ions, which was in line with the reduced pore volume and permeability.

Supplementary material related to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.csbj.2023.11.026.

The following is the Supplementary material related to this article Video S2.

.

The following is the Supplementary material related to this article Video S3..

In addition to the homomeric hemichannel, we wondered whether the V37M variant was haploinsufficient to compromise the hemichannel function; to examine this, three in silico models with heteromeric V37M mCx26 (called heteromer-1 to −3 of V37M-mCx26) were constructed, which were composed of the same 1:1 ratio of WT and V37M monomers but with different hexameric arrangements (Fig. 2d). In 4 μs MD simulations, both heteromer-1 and − 3 retained the normal pore volume, similar to WT-mCx26 (see Fig. 2e and Table 1), while heteromer-2 showed a reduced permeability. However, heteromer-1 and − 3 have a lower configurational potential (Econf) − 6.54 × 104 and − 6.50 × 104 kJ mol-1, respectively, than that of heteromer-2 (−6.41 ×104 kJ mol-1), indicating that heteromer-1 and − 3 are predominant in conformational population according to Boltzmann relation (probability of a conformation ∼ exp(-Econf/kBT), where kB and T are Boltzmann constant and temperature, respectively).

Overall, our in silico mCx26 models demonstrated that V37M could result in dysfunction of the hemichannel in homomers and sufficient function in the predominant heteromers. The pore volume in our mCx26 models also exhibited high correlation with potassium permeability (Spearman ρ = 0.85), suggesting that the compromised permeability of the hemichannel was strongly associated with the shrunken pore volume.

2.3. Reduced water channeling in both V37I-hCx26 and V37M-mCx26 as a function of the depth of hemichannels

To monitor the mutant-caused pore shrinkage longitudinally, the distribution of water molecules inside the pore was monitored by a cumulative count of water molecules in all the snapshots during the last microsecond of the simulation. V37I-hCx26 showed a notable shrinkage in the lower half, 0–5 Å above the membrane center (where 0 Å is at), (Fig. 2f), which is below the location of Res37, at average 6.4 Å above the membrane center. The reduced water channeling can also be observed in the replication of the simulations of V37I-hCx26, compared to WT-hCx26 (Fig. S1c).

Regarding the mCx26 models, WT-mCx26 demonstrated an hourglass-like water channel, with the narrowest point located toward the cytoplasm end. V37M-mCx26 exhibited an apparent narrowing of the channel from 8 (near the mutated residue Met 37, called 37 M) to − 4 Å along the membrane normal (Fig. 2g). These observations suggest that V37I-hCx26 and V37M-mCx26 may contribute to hemichannel obstruction through different mechanisms.

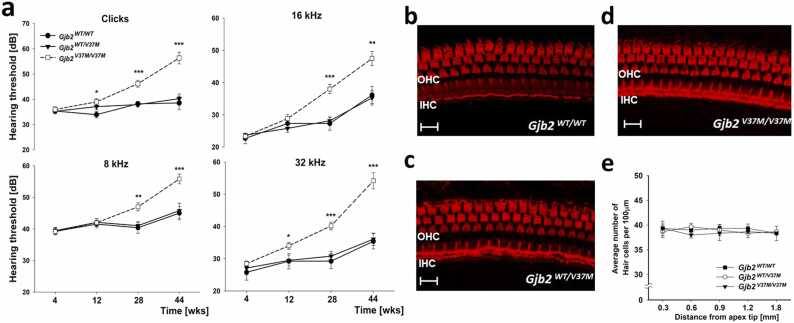

2.4. Gjb2V37M/V37M mice demonstrates a faster deterioration of hearing with age

To validate our structural dynamics models, knock-in mouse models were constructed in a C57BL/6 background harboring homozygous and heterozygous Gjb2 V37M variants (that is, Gjb2V37M/V37M and Gjb2WT/V37M mice, respectively). The hearing thresholds were recorded for 13 Gjb2WT/WT, 19 Gjb2V37M/WT, and 30 Gjb2V37M/V37M mice at 4, 12, 28, and 44 weeks. Consistent with previous studies, C57BL/6 mice developed progressive hearing loss with increasing age [54]. There was no significant difference in hearing thresholds between Gjb2V37M/WT and Gjb2WT/WT mice at any frequency and age, whereas Gjb2V37M/V37M mice demonstrated a faster and significant deterioration of hearing with age compared to Gjb2WT/WT and Gjb2V37M/WT mice mainly in 28 and 44 weeks (Fig. 3a and Table S4), indicating that V37M was inherited in an autosomal recessive manner in mice. All three genotypes demonstrated normal appearance of hair cells in the organ of Corti (Figs. 3b to 3d) without significant differences in the cochleogram (hair-cell-count graph) at 4 weeks (Fig. 3e). These results indicate that the progressive hearing loss in Gjb2V37M/V37M mice was found without loss of hair cells.

Fig. 3.

Faster deterioration of hearing loss without significant changes of hair cells inGjb2V37M/V37Mmice. (a) Progressive hearing loss with age in Gjb2V37M/V37M mice with a faster rate of deterioration for all frequencies than Gjb2WT/WT and Gjb2V37M/WT mice (unit: dB of sound pressure level; n > 10 for each strain, mean ± SEM). (b–d) Cochleograms of all three genotypes at four weeks without significant changes of viable outer hair cell numbers in the middle turn of the organ of Corti. (e) The average number of hair cells for each genotype was counted using high-power field of per cochleogram from regions progressively distant from the apex of the cochlea (n = 3 for each strain, mean ± SEM). Student’s t-test is calculated and displayed as follows: * , p < 0.05; * * p < 0.01; * ** , p < 0.001. (IHC, inner hair cells; OHC, outer hair cells; Bar = 10 µm).

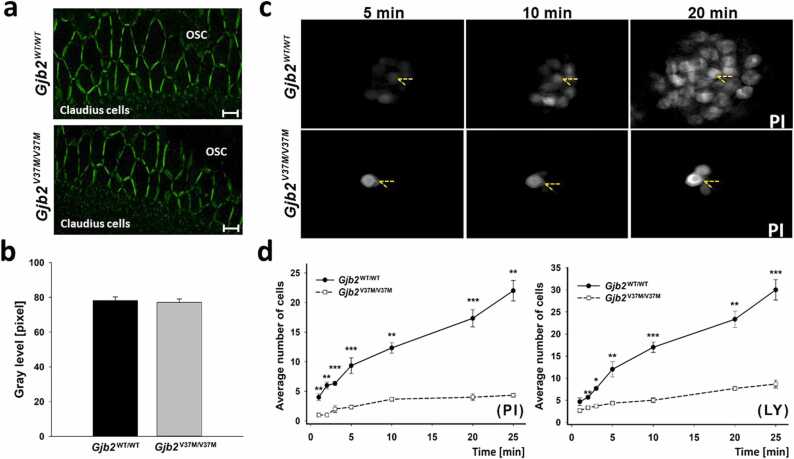

2.5. Normal expression and localization of Cx26 is shown, but compromised GJ-mediated metabolite transfer occurred in V37M mice

To investigate whether the V37M variant affects the expression and trafficking of the protein, the formation of GJs in the supporting cells of the cochlea was examined using immunolabeling for mCx26. GJ plaques, as revealed by the clustering of mCx26 immunoreactivities, were identified in the outer sulcus cells and Claudius cells (Fig. 4). The sizes of the GJ plaques were similar in Gjb2WT/WT and Gjb2V37M/V37M mice (Fig. 4a). This observation was confirmed by quantification of the density of mCx26 immunoreactivities using the MetaMorph software: the fluorescence intensity of mCx26 immunoreactivities was 78.2 ± 2.15 pixels in Gjb2WT/WT mice (n = 3) and 77.2 ± 1.93 pixels in Gjb2V37M/V37M mice (n = 3), showing no difference between the two groups (Fig. 4b; Student’s t-test, p > 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Normal expression of Cx26 but abnormal channel permeability inGjb2V37M/V37Mmice. (a) Patterns of Cx26 immunoreactivity in outer sulcus and Claudius cells of Gjb2WT/WT and Gjb2V37M/V37M mice. (OSC, outer sulcus cells; bar = 5 µm). (b) Density of Cx26 immunoreactivity with no significant difference between the two strains (n = 3 for each strain, mean ± SEM). (c) Time-lapse recordings of intercellular dye transfer in Gjb2WT/WT and Gjb2V37M/V37M mice after fluorescent dyes propidium iodide (PI) was injected into a single Claudius cell in Gjb2WT/WT (upper row panels) and Gjb2V37M/V37M (lower row panels) mice (dotted arrows: injection site). (d) Consistently reduced number of cells (y-axis) receiving PI (left panel) and another dye lucifer yellow (LY, right panel), respectively, by GJ-mediated diffusion in Gjb2V37M/V37M mice compared to Gjb2WT/WT mice with time (x-axis) (n = 5 for each strain, mean ± SEM). * : p < 0.05; * *: p < 0.01; * ** : p < 0.001 (Student’s t-test).

We then investigated whether V37M affected GJ-mediated metabolic coupling in supporting cells using dye diffusion assays in flattened cochlear preparations. Two well-characterized fluorescent dyes, positively charged propidium iodide (PI) and negatively charged lucifer yellow (LY), are known to pass through the cochlear GJs. PI and LY were injected into single Claudius cells [55] to quantify the differences in metabolic coupling among cells. Time-lapse recordings were performed to assess the time course of PI and LY diffusion (Fig. 4c). Data obtained from Gjb2WT/WT and Gjb2V37M/V37M mice at various time points after the start of dye injection showed that the extent of fluorescent dye diffusion gradually increased with time (Fig. 4d). These data were quantified by plotting the number of dye-recipient cells as a function of time after dye injection. This demonstrated that the number of cells undergoing dye transfer in the sensory epithelium of Gjb2V37M/V37M mice was consistently lower at all time points, indicating that V37M caused a deficit in GJ-mediated metabolite transfer among cells in the sensory epithelium of the cochlea.

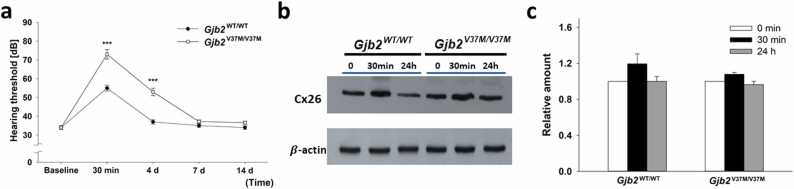

2.6. Gjb2V37M/V37M mice reveals higher shifts in hearing thresholds after noise exposure

Consistent with our previous report [56], mice of all genotypes after 3 h noise exposure in the level of 115 dB (unit of Sound Pressure Level, SPL), developed significant elevation of hearing thresholds immediately (30 min) and recovered gradually over 14 days (Fig. 5a). Notably, Gjb2V37M/V37M mice (n = 5 for each background) revealed significantly higher shifts in hearing thresholds within the first few days after noise exposure than Gjb2WT/WT mice. The significant difference in the hearing threshold shift between Gjb2V37M/V37M and Gjb2WT/WT mice persisted for longer than 4 days (Fig. 5a). Overall, these data indicate that Gjb2V37M/V37M mice were more vulnerable to noise than Gjb2WT/WT mice.

Fig. 5.

Higher vulnerability to noise inGjb2V37M/V37Mmice. (a) Gjb2V37M/V37M mice after 3 h of noise exposure revealed a significantly higher shift in hearing thresholds than Gjb2WT/WT mice at 30 min and 4 d (n = 5 for each strain; baseline: no noise exposure). (b) Western blot and (c) relative amounts of Cx26 expression after noise exposure (mean ± SEM) normalized to the counterpart before noise (0 min) in Gjb2WT/WT and Gjb2V37M/V37M mice, respectively. Both slightly increased immediately (30 min); however, they recovered to baseline levels after 24 h without significant differences between the two groups. (***: p < 0.001, Student’s t-test).

To investigate the mechanisms underlying vulnerability to external noise, the expression of mCx26 was measured after noise exposure in the cochlea. The expression of mCx26 in the cochlea increased immediately after 30 min in both Gjb2WT/WT and Gjb2V37M/V37M mice but recovered to baseline levels after 24 h (Fig. 5b). When normalized to the baseline Cx26 expression level before noise, there was no significant difference in the fold change of Cx26 expression at 30 min between Gjb2WT/WT and Gjb2V37M/V37M mice (1.19 ± 0.11 vs. 1.08 ± 0.02, Student’s t-test, p = 0.41; Fig. 5c). These data indicate that the vulnerability of Gjb2V37M/V37M mice to noise may be related to protein malfunction rather than decreased protein expression.

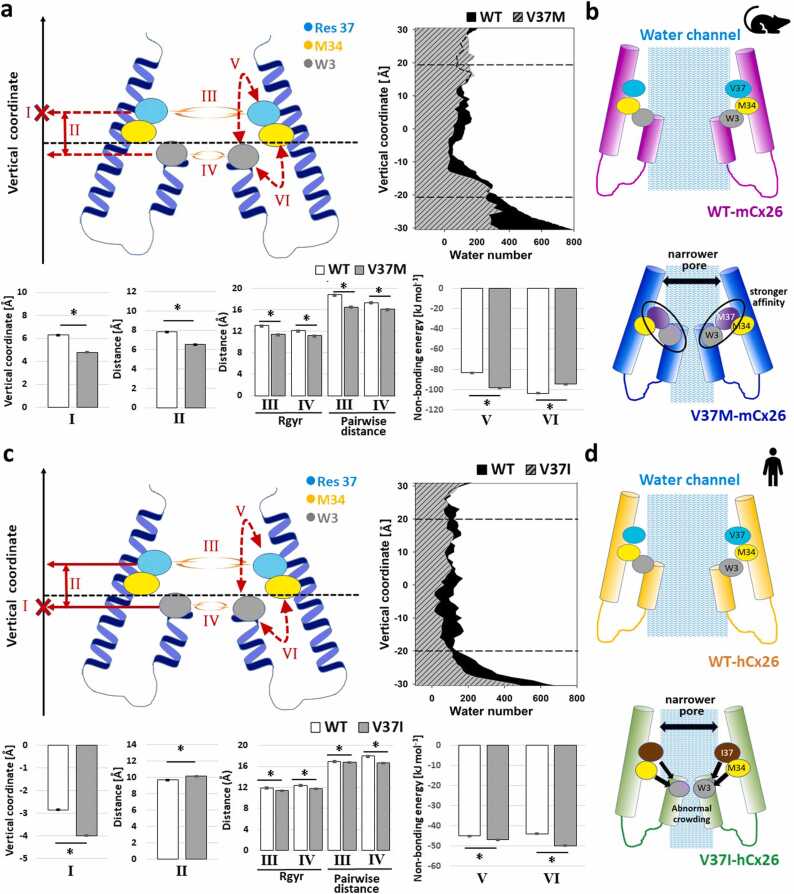

2.7. V37M results in aberrant interaction patterns between amino acid residues and blocked the mCx26 hemichannel

The blockage mechanisms caused by the missense V37M variant was elucidated using in silico model. Based on the reported crystal structures (PDBID: 2ZW3) [50], Maeda et al. proposed that the gating mechanism of the Cx26 hemichannel was driven by a plug-mediated model with the plug (that is, the NTH domains) mainly stabilized by the Trp3-Met34 (W3-M34) sulfur-aromatic interaction. This interaction was ∼6 kJ/mol stronger than regular hydrophobic interactions [57] and could make the NTHs adhere to the inner edge of the pore [34], [50] to maintain the open state of the pore. Several previous studies have argued that M34A and M34T variants would destabilize the affinity between NTHs and TM1, which would significantly disturb the open conformation of the hemichannel [33], [34].

V37M, situated at the inner edge of the pore near M34, may spatially disturb the normal W3-M34 interaction. In our simulations with centralized vertical coordinates, the hexameric mutated Met 37 (6–37 M, where “hexameric” was represented as “6-”) in V37M-mCx26 demonstrated downward shift and shorter distance from hexameric W3 (6-W3) compared to the hexameric V37 (6-V37) in WT-mCx26 (Fig. 6a-I and II). Both the 6-W3 and 6–37 M groups in V37M-mCx26 suggested a higher degree of crowding than the WT (Fig. 6a-III and IV). This result was rationalized by the affinity differences between the two pairs of hexameric groups, [6-Res37, 6-W3] and [6-M34, 6-W3] (stronger affinity corresponds to a larger negative quantity of binding free energy). Affinity of [6-V37, 6-W3] in WT-mCx26 was weaker than that of [6–37 M, 6-W3] in V37M-mCx26 (−83.43 ± 0.16 vs. −98.25 ± 0.2 [kJ mol-1] in Fig. 6a-V), whereas affinity of [6-M34, 6-W3] in WT-mCx26 was stronger than that of [6-M34, 6-W3] in V37M-mCx26 (−103.46 ± 0.17 vs. −94.72 ± 0.15 [kJ mol-1] in Fig. 6a-IV). It could be inferred that 6–37 M competed with 6-M34 for the binding for 6-W3, resulting in a downward shift of 6–37 M that were “dragged” by 6-W3, tilting the inner edge to shrink the upper opening of the channel (Fig. 6b), which was consistent with the reduced number of water molecules in V37M-Cx26 (right panel of Fig. 6a). Collectively, our simulations indicate that the abnormal ion permeability of V37M-mCx26 could be attributed mainly to the increased affinity of 37 M for the W3-containing NTHs, which caused the upper wall to tilt and collapse, resulting in pore shrinkage (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6.

Characteristics of conformational changes and energetics derived from MD simulations to summarize blockage mechanisms of Cx26 hemichannels. (a and b) Computational quantities from wild-type and mutant with homomeric V37M variants in mCx26. (c and d) Corresponding quantities from wild-type and mutant with homomeric V37I variants in the hCx26 protein. The vertical axis in (a) and (c) aligns with the membrane normal and meets the dash-lined horizontal axis at the membrane center (where 0 Å is at), defined as the averaged vertical coordinates of choline groups in both upper and lower leaflets of DOPC membrane; The “X” symbol marks the vertical coordinate of the target residue described in bar plot I, which is residue 37 and W3 in panels (a) and (c), respectively. The area plots in the right panel of (a) and (c) regarding the average water number along the vertical axis (WT colored in black; mutants colored in dashed gray) are copied from the left panel of Figs. 2g and 2f, respectively. Means ± SEM of computational quantities calculated from all snapshots of the equilibrated MD simulation systems are illustrated as bar plots with error bar. (*: p < 0.0001, Student’s t-test).

2.8. V37I causes abnormal NTHs crowding and blocked the hCx26 hemichannel

The different interrupted ranges of water channels (right panel of Figs. 6a and 6c) suggest different blockage mechanisms between V37I-hCx26 and V37M-mCx26. Our simulations revealed a downward shift of 6-W3 with increased distance from hexameric mutated Ile37 (6–37I) in V37I-hCx26 (Fig. 6c-I and -II), and both 6–37I and 6-W3 in V37I-hCx26 demonstrated higher crowding than those in WT-hCx26 (Fig. 6c-III and -IV). The 6-W3 of V37I-hCx26 also revealed a similar affinity with 6-Res37 but a stronger affinity with 6-M34 compared to the counterparts of WT-hCx26 (Fig. 6c-V and -VI). This indicated that 6-W3 would cause not only the blockage of the pore but also the proximity of the TM1 helices.

Accordingly, the abnormal shrinkage in V37I-hCx26 was initially attributed to the weaker affinity between 37I and NTHs, followed by the abnormal approaching of W3-containing NTHs at the lower location of the hemichannel, and 6-W3 would further attract both 6–37I and 6-M34 to form a narrower pore (Fig. 6d), which interrupted the water channel (right panel of Fig. 6c). The crowding of NTHs also generated an environment unfavorable for the water molecules to stay in the pore and attracted the TM1 domain closer. Based collectively on these results, our in silico models indicate that the abnormal permeability of V37I-hCx26 was mainly attributed to abnormal NTHs approaching caused by the reduced affinity with 37I, which narrowed the pore volume and finally blocked the hemichannel.

3. Discussion

In this study, we established a MD simulation platform to investigate the structural dynamics of dysfunctional Cx26 hemichannels associated with GJB2 variants. Our results deciphered the conformational changes of the Cx26 hemichannel conferred by the highly prevalent GJB2 V37I variant in humans and successfully predicted the functional consequences and inheritance mode of the artificial Gjb2 V37M variant in mice. Our MD simulations consistently demonstrated a narrow pore volume and reduced potassium permeability in both the V37I-hCx26 and V37M-mCx26 hemichannels. However, the blockage mechanisms of these two variants appeared different: the V37I variant in hCx26 caused abnormal approaching of NTHs, leading to the subsequent shrunken pore volume and interrupted water channel, whereas the V37M variants in mCx26 resulted in aberrant binding patterns around 37 M and tilted the inner edge of the hemichannel, followed by pore blockage (Fig. 6). Both blocking mechanisms involved no ionizable groups and therefore the pore shrinkage due to the variants can be minimally influenced by fluctuations in electrostatic environment such as concentration of ions [58] or the pH value [59]). The changes in pore hydrophobicity caused by V37I or V37M trigger global conformational changes of Cx26 hemichannels, leading to impaired GJ-mediated channeling [41], [42], [43] and observed hearing loss in both mice and humans [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [52] (Fig. 3).

Our MD simulations of V37I-hCx26 demonstrated a reduced number of water molecules and an interruption in the lower part of the water channel (0 to −15 Å along the membrane normal shown in the right panel of Fig. 6c), which was highly correlated with the closer contact of the NTHs (represented by the higher crowding of 6-W3 in Fig. 6c-IV). Therefore, it could be inferred that V37I would cause abnormal approaching of NTHs, which is promoted by a weakened affinity initially between 6 and 37I and NTHs. This is followed by the whole TM1 domains attracted toward already crowded TM1 domains, which in turn narrows the pore volume (Fig. 6d). Furthermore, according to structure-ensemble-derived empirical potentials [60], the residue pair [Ile, Ile] had stronger inter-residue contact energies than the pair [Val, Val] (−5.69 vs. −4.81 in RT units for [Ile, Ile] and [Val, Val], respectively; R: gas constant (8.314 J K−1 mol−1); T: temperature (K)), especially when sometimes [Ile, Ile] and [Val, Val] pairs can come within 5–7 angstroms from each other, which was in line with the higher crowding of 6-Res37 in V37I-hCx26 than in WT-hCx26. We also performed AA-MD simulations for WT-hCx26 and V37I-hCx26 for 700 ns with CHARMM36m [61] forcefield via the OpenMM package [62]. The results (Supplementary Video 5) showed that during the 700 ns simulations, WT-hCx26 possessed higher potassium permeability than V37I-hCx26 (16 vs. 13), consistent with the results of CG-MD simulations. By elucidating the conformational changes underlying the reduced permeability and conductance reported in previous in vitro biochemical studies [41], [42], [43], our MD simulations provide novel structural dynamics insights into the dysfunction of hCx26 caused by the V37I variant.

Supplementary material related to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.csbj.2023.11.026.

The following is the Supplementary material related to this article Video S4..

The following is the Supplementary material related to this article Video S5..

Until now, several studies have investigated the pathogenic mechanisms of known variants by exploring their mutational effects on the Cx26 (Table S3), including the perturbation of conformational stability (e.g. R143Q [63] and C169Y [64]) or calcium-binding sites (e.g. T8M [38], S17F [65]), abnormal gating functions (e.g. G12R [39], T86L [66]), and higher energy barrier (e.g. M34T [34]). In this study we further focused on the verification for the predictive ability of our MD simulation model in assessing the pathogenicity of other GJB2 variants, an in silico mCx26 model was constructed with the artificial V37M variant and functional assays were performed using transgenic mice. Our MD simulations of the homomeric V37M-mCx26 hemichannel demonstrated a reduced number of water molecules and an interrupted water channel around the 37 M residue (see vertical axis ranging from 0 to 10 Å parallel to the membrane normal, shown in the right panel of Fig. 6a, which was highly correlated with the crowding between 6-W3 and 6–37 M. The conformational change was mainly attributed to the stronger affinity between 6-W3 and 6-Res37 in V37M-mCx26 than that in the wild-type mCx26, which was in line with the reported stronger inter-residue contact energies (−5.37 vs. −5.04 in RT units for [Met, Trp] and [Val, Trp], respectively) [60] ([Met, Met] and [Val, Val] pairs sometimes can come closer within 5.5–8.5 angstroms apart from each other). Consistent with these results, the subsequent animal studies showed that mice with the homozygous V37M variant (Gjb2V37M/V37M) developed hearing loss. Further functional experiments revealed that the expression and localization of Cx26 and GJs remained unchanged in homozygous mice; however, GJ-mediated metabolite transfer was affected by the V37M variant, indicating that the permeability of GJs was compromised in the cochlear sensory epithelium of homozygous mice.

Furthermore, our MD simulations demonstrated that heteromeric V37M-mCx26 did not compromise the functionality of the hemichannel, as the two predominant heteromeric V37M-mCx26 forms (that is, heteromer-1 and −3 in Fig. 2d) retained normal pore volume compared to the WT-mCx26 hemichannel. Interestingly, this finding provides a plausible explanation for the normal hearing observed in mice with the heterozygous V37M variant (Gjb2WT/V37M): given that WT-mCx26 and V37M-mCx26 are equally expressed, the physiological function of GJs could be preserved. Notably, among the five mCx26 systems shown in Table 1, the revealed high correlation with , suggesting that compromised permeability was mainly attributed to the shrunken pore volume, and the three metrics could serve as reliable indicators to assess the dysfunction of Cx26 conferred by novel missense GJB2.

One question that arises from the clinical study is why the homozygous mutants of GJB2 are more affected than the heterozygous counterparts. Two aspects of protein stability and conformational dynamics can be used to explain this phenomenon. For the former, the configurational energies of the mutants, including the V37M heteromers and homomer, were calculated and compared to the wild type. The results showed that the wild type had the most stable conformation with the lowest potential (−7.17 ×104 kJ mol-1), followed by heteromer-1 (−6.54 ×104 kJ mol-1), heteromer-3 (−6.50 ×104 kJ mol-1), and homomer (−6.49 ×104 kJ mol-1), indicating that the wild type was the predominant conformational population. We hypothesized that in unaffected carriers, who have both types of Cx26 monomer (WT and mutant), the WT hexamers are more abundant than the heteromers and thus maintain normal channeling function. In contrast, for those with homozygous mutants, only high-energy homomers with poor channeling are present, leading to pathogenicity. For the aspect of conformational dynamics, a relatively stable heteromer, heteromer-3, which was one of the most predominant conformers, had abundant water molecules inside the pore (Fig. S3a), triggering less crowding of 6-W3 groups, and lower affinity of [6-Res37, 6-W3] than the V37M-Cx26 homomer (Fig. S3b-c), suggesting that the heterozygous V37M exhibited haplosufficiency pattern, meaning that hexameric Cx26 with heterozygous mutant was still open enough to provide normal channeling ability (Fig. S3d).

Our animal studies revealed that mice homozygous for V37M were more vulnerable to noise exposure. These findings are consistent with those of a previous study that reported increased susceptibility to noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL) in Gjb2 knockout mice [67]. Several clinical studies have documented an association between NIHL and certain GJB2 variants [68], [69]. The increased susceptibility to NIHL in patients with specific GJB2 genotypes, as demonstrated in Gjb2 knockout mice and our V37M knock-in mice, could be attributed to the compromised permeability of GJs to small metabolites or ions, such as potassium. Previous studies have revealed that potassium recycling in the cochlea may play a crucial role in preventing apoptosis of hair cells caused by NIHL [70], [71]. These findings may have important clinical implications because patients with specific GJB2 variants should avoid noise exposure.

Apart from GJB2-related SNHI, the connexin gene family has been associated with various genetic disorders and tumor formation via gap junctional intercellular communication or signaling regulation of protein-protein interaction [72], wherein Cx26 is reported to increase cellular metastatic capability of melanoma cells [73]; however, it decreases tumor proliferation and invasion in breast cancer cells [74], indicating its complex roles and clinical significance in oncology. Although only focusing on genetic SNHI, the strength of this study lies in the comprehensive in silico demonstrations and structural insights into the blocking mechanisms conferred by the missense variants (human GJB2 V37I of clinical significance and artificial mutant V37M of interest) by visualizing conformational changes through microsecond-scale simulations. Our subsequent in vitro and in vivo experiments in mice with Gjb2 V37M verified the predictive potential of our MD simulations for assessing the pathogenicity and inheritance modes of GJB2 variants. Notably, in the structural study regarding the connexin Cx46/Cx50 proposed by Myers et al. [75] suggested that the landscape of the pore energy barrier in Cx46, Cx50 and Cx26 preferred the transports of potassium ions, and in our CG model we observed the same results in both human and mouse wild-type Cx26 (K+ vs. Cl-: 3 vs. 1 in WT-hCx26 and 6 vs. 4 in WT-mCx26) and the further delineation of pore blockage around the V37I/V37M variants that caused a physical barrier affecting potassium permeability (Fig. 6). Furthermore, Myers et al. proposed that compared to Cx46/Cx50, Cx26 harboring a less regular NTH conformer would be an intrinsic feature related to the its lower stability of the open conformation [75], which was consistent with our MD simulations in which NTHs in WT-hCx26/mCx26 exhibited soft contact of the pore inner edge; however, it remained sufficiently open to permit the transmission of potassium ions (Supplementary Videos 1 and 3).

However, there are limitations of our current methodology. In this study we focused on dysfunctional permeability related to conformational changes involving the N-terminal and TM1 domains of Cx26. The pathogenicity of missense variants located in other domains of Cx26 requires further studies, and our model is not suitable to study pathogenicity of null/mis-splicing/mis-trafficking variants [76], [77], [78]. Furthermore, the prediction platform we described in the study is based on established MD methods and straightforward quantities such as the number of potassium ions passing through the channel. However, the mechanistic revelation and explanation of the effect of the mutation could be analyzed by other methods [79], [80] in the future.

Furthermore, it has been reported that GJB2 variants can lead to SNHI through digenic inheritance with GJB6 [81] and GJB3 variants [82], respectively. In parallel with clinical findings, Cx26 can oligomerize with Cx30 and Cx31 to form heteromeric or heterotypic Cx26/Cx30 [83] and Cx26/Cx31[84] channels in the cochlea. In principle, each Cx26 monomer in our model could be freely replaced with isoforms of other SNHI-related connexins to co-assemble a heteromeric hemichannel or a heterotypic GJ channel. Unfortunately, the crystal or cryo-electron microscopy structures for most SNHI-related connexins remain unsolved for the time being. Putative structures constructed using homology modeling [85], [86] or AlphaFold [87] may enable the generation of heteromeric/heterotypic channels for investigating digenic pathogenetics in the future.

In conclusion, we revealed the channel closure mechanism of the highly prevalent GJB2 V37I variant, and the functional consequences as well as the inheritance pattern of the tested Gjb2 V37M variant in mice were cogently predicted. Our MD simulations demonstrated that both variants led to a narrowed pore volume and reduced potassium permeability through different blockage mechanisms. As a proof-of-concept, our MD simulations could be developed as an assessment tool for addressing the pathogenesis and inheritance of GJB2-related SNHI as well as other diseases caused by connexin dysfunction.

4. Materials & Methods

4.1. Construction of the membrane-embedded Cx26 model in silico

The original tertiary crystal structure of human connexin 26 (Cx26) protein [50] (PDB ID: 2ZW3) had missing residues (residues 110–124) and N-terminal amino acid residue (Met1). We used SWISS-MODEL [51] and open-source software PyMOL (Version 2.3.3, Schrödinger, LLC) [88] to structurally model the missing loop and Met1 based on the primary sequence of human Cx26 protein (UniProt ID: P29033), while the hexameric hemichannel was constructed by superimposing the single-chain homology model onto each chain of the crystal structure (PDB ID: 2ZW3). The protonation state of protein in this wild-type human Cx26 hemichannel (WT-hCx26) at neutral pH was suggested by PROPKA [89] (Version 3.1). Next, the coarse-grained (CG) model of WT-hCx26 embedded in a phospholipid bilayer composed of 444 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC) molecules in a 14 × 14 × 19 (nm3) rectangular box was generated using CHARMM-GUI [90], [91], which was solvated in bulk non-polar water molecules with 150 mM KCl to mimic a high potassium concentration in the endolymph of the scala media [92]. The Positioning of Proteins in Membrane (PPM 2.0) method deposited in the Orientations of Proteins in Membranes (OPM) database [93] was incorporated into the CHARMM-GUI platform to provide the recommended arrangement of proteins spanning the lipid bilayer, such as the position of membrane boundaries and orientation-related parameters (e.g., title angle and membrane penetration depth).

A protein mutant with the homomeric variant V37I (V37I-hCx26) was constructed based on this WT-hCx26 model using the same pipeline. In a similar vein, using SWISS-MODEL [51], a structural model of mouse connexin 26 (mCx26) and its V37M variant were constructed using mouse Cx26 protein sequence (UniProt ID: Q00977) and the crystal structure of human connexin 26 (Cx26) protein (PDB ID: 2ZW3) [50].

4.2. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations

All CG-MD simulations (∼30 μs in total) were performed using the GROMACS package program [94] and Martini force field [95], [96]. The pressure and temperature were maintained at 1 bar and 310 K, respectively, and the cut-off values for both Coulomb and van der Waals forces was 1.1 nm. All simulations were performed for 4 μs in NPT ensemble (i.e., simulation in isothermal-isobaric ensemble maintaining constant particle N, pressure P, and temperature T) controlled by Parrinello–Rahman barostat and Berendsen thermostat after at least 30 ns of equilibration. All trajectories of the CG-MD simulations were calculated at 20 fs per step, and the coordinates were recorded every 1 ns. Subsequently, the vertical coordinates of the rectangular periodic boundary box per frame were centered on the mean vertical coordinates of all the choline groups in both the upper and lower leaflets.

AA-MD simulations (1.4 μs in total) were performed using the OpenMM package [62] and CHARMM36m forcefield [61]. The temperature was set at 310 K using Langevin integrator, and the pressure was maintained at 1 bar using Monte Carlo membrane barostat. Particle mesh Ewald method with a cutoff distance of 12 Å was used for calculating nonbonded interactions. TIP3 water model was used. All simulations were performed for 700 ns in NPT ensemble after 1.5 ns of equilibration, followed by taking snapshots throughout MD trajectories at the interval of 1 ns for the assessment of potassium permeability.

4.3. Determination of pore volume, and potassium permeability

The pore volume of Cx26 hemichannel was represented by the average number of water molecules () inside the hemichannel pore per snapshot (10 ns per frame in a 4 μs simulation) and within the average vertical coordinates of DOPC beads located in both the upper and lower leaflets. The potassium permeability () was calculated as the total number of potassium ions passing through the pore of the hemichannel that was determined according to the trajectory at which they entered from either entrance and finally left from the opposite gate (see Supplementary Videos 1 and 3 as examples) during the 4 μs simulation.

4.4. Generation of knock-in mice

A mutant gene-targeting vector was constructed using recombineering approach, previously developed by Copeland et al. [97], [98] A BAC clone (clone no. bMQ369p05 Geneservice™) from 129S7/AB2.2 BAC library, containing the mouse Gjb2 genomic region, was used to construct the gene-targeting vector (Fig. S4a). The BAC was transferred to the modified E. coli strain, EL350, by electroporation. The subcloned 15.9 kb genomic region was modified in a subsequent targeting round by inserting a neomycin (neo) cassette from PL452 plasmid and creating the V37M variant. The conditional targeting vector was linearized by NotI digestion and electroporated into R1 embryonic stem (ES) cells. G418 (240 μg mL−1) and ganciclovir (2 μM) double-resistant clones were analyzed using Southern blot hybridization (Fig. S4b). The retained neo cassette flanked by loxP sites was excised in vivo by transfection of the targeted clone with a plasmid transiently expressing Cre recombinase. The established ES clones were identified by PCR screening and subsequently injected into C57BL/6 blastocysts to produce chimeras. The mice were maintained on a C57BL/6 genetic background for further experiments. Heterozygous mice were bred to obtain Gjb2WT/WT, Gjb2V37M/WT, and Gjb2V37M/V37M mice (Fig. S4c). All animal experiments were carried out in accordance with the animal welfare guidelines approved by the National Taiwan University Hospital (approval no. 200700204).

4.5. Audiological measurements

Mice were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (35 mg kg−1), delivered intraperitoneally and maintained in a head-holder within an acoustically and electrically insulated and grounded test room. An evoked potential detection system (Smart EP 3.90, Intelligent Hearing Systems, Miami, FL) was used to measure the auditory brainstem response (ABR) thresholds in mice. Click sounds as well as 8, 16, and 32 kHz tone bursts at varying intensities (from 10 dB to 130 dB SPL), were given to evoke ABRs in mice [56].

4.6. Inner ear morphology

The inner ear tissues of mice were subjected to hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and whole-mount studies [99]. The H&E-stained tissues were examined using a Nikon Optiphot-2 microscope. For whole-mount studies, the tissues were stained with rhodamine–phalloidin (1:100 dilution; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) and images were obtained using a laser scanning confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 510, Germany).

4.7. Protein expression

Flattened cochlear preparations [55] obtained from P8 mice were fixed in paraformaldehyde (4%), permeabilized in Triton X-100 (0.5%), and blocked in goat serum (10%). After incubation with primary antibodies against Cx26 (Zymed Labs, South San Francisco, CA, USA) and FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies, the samples were examined using a laser scanning confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 510, Carl Zeiss, Germany). The fluorescence intensity of Cx26 immunoreactivities was quantified using Metamorph 7.1 software (Universal Imaging Corporation, Downingtown, PA) in three Gjb2WT/WT and three Gjb2V37M/V37M mice. For the density of Cx26 immunoreactivities plot in the inner ear sample of each animal, five images of each mouse were randomly selected for the calculation, and the mean of fluorescence intensity of Cx26 was calculated in triplicate and compared between Gjb2WT/WT and Gjb2V37M/V37M mice.

4.8. Fluorescent dye diffusion

Flattened cochlear preparations [55] obtained from P8 mice (C57BL/6 background) were placed in a recording chamber mounted on an upright microscope (Axioskop2 FX plus; Carl Zeiss, Germany). An extracellular solution (HBSS) was perfused at a rate of 1 drop s−1. DIC optics enabled us to directly recognize different cochlear cell types in the acutely isolated cochlear segment. Membrane-impermeable fluorescent dyes were injected into the cytoplasm of a single cell by forming the whole-cell patch-clamp recording mode that was confirmed by monitoring the whole-cell resistance and capacitance using a standard protocol (Axonpatch 200 B, Axon Instruments, CA). For the preparation of fluorescent dyes, PI (0.75 mM, MW= 668 Da, charge = +2, catalog no. P1304MP), and LY (1 mM, MW=457 Da, charge = −2, catalog no. L-453) were added to the pipette solution containing KCl (120 mM), MgCl2 (1 mM), HEPES (10 mM), and EGTA (10 mM). Intercellular dye diffusion patterns were recorded using a digital single-lens reflex (D700, Nikon, Japan) at various time points after the establishment of the whole-cell recording conformer.

4.9. Noise exposure experiments

Twelve-week-old mice were exposed to octave band noise for 3 h with a Bruel & Kjaer 2238 sound level meter peak at 4 kHz and 115 dB SPL [54]. The noise room was fitted with a speaker (model NO. 1700–2002, Grason-Stadler Inc., MN) driven by a noise generator (GSI-61, Grason-Stadler Inc., MN) and power amplifier (5507-Power, TECHRON, Union City, IN). After 3 h noise exposure, ABR thresholds at clicks were then recorded in mice after 30 min and 4, 7, and 14 d.

In addition to hearing levels, Cx26 expression after the noise exposure was also investigated. Protein extracts of the inner ear were supplemented with DTT, heated for 5 min at 95 °C, separated by SDS gel electrophoresis, and transferred to a PVDF membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Little Chalfont, UK) by semi-dry electroblotting. The PVDF membranes were developed using an enhanced chemiluminescence western blot detection kit (Pierce SuperSignal® West Dura, Rockford, IL) and exposed to Lumi-Film chemiluminescent detection films (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). The experiment was replicated five times, and the results were averaged.

4.10. Analyses of affinities between pairs of hexameric residue/NTHs clusters

The affinity calculated between two targeted hexameric residue clusters was determined by non-bonding energies composed of both electrostatic and van der Waals forces based on the Martini force fields. Each hexameric residue cluster was defined as a group of six residues from each monomer of the hexameric Cx26 hemichannel. The affinities were recorded every 1 ns during the 4 μs simulation to calculate the mean ± SEM.

4.11. Assessment of the degree of crowding in the Cx26 hemichannel

Two physical quantities were calculated to assess the degree of crowding: average pairwise distance and radius of gyration (Rgyr). The pairwise distance was determined by recording the average residue-residue distance within each hexameric residue cluster (i.e., the average distances of a total of 15 pairs of residues for each hexameric residue cluster) per snapshot (1 ns per frame) during the 4 μs simulation and represented as mean ± SEM. The Rgyr was determined by recording all 3D coordinates of residues within each hexameric residue cluster to calculate Rgyr per snapshot during the 4 μs simulation and represented as mean ± SEM. The Rgyr equation is as follows:

| (1) |

where and are the position and molecular mass of the th residue within each hexameric residue cluster, respectively, and is the weighted average position per hexameric residue cluster.

Funding statement

This study was supported by research grants from National Health Research Institutes (NHRI-EX111-10914PI), as well as the collaborative project between National Tsing Hua University and National Taiwan University Hospital Hsin-Chu Branch (110Q2528E1).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Cheng-Yu Tsai: Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft. Ying-Chang Lu: Validation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. Yen-Hui Chan: Validation, Investigation. Navaneethan Radhakrishnan: Visualization. Yuan-Yu Chang: Visualization. Shu-Wha Lin: Methodology, Resources. Tien-Chen Liu: Resources. Chuan-Jen Hsu: Resources. Pei-Lung Chen: Resources. Lee-Wei Yang: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Chen-Chi Wu: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank technical support from the Taiwan Mouse Clinic and Transgenic Mouse Models Core Facility of National Core Facility Program for Biotechnology supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology.

Supporting information

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.csbj.2023.11.026.

Contributor Information

Lee-Wei Yang, Email: lwyang@life.nthu.edu.tw.

Chen-Chi Wu, Email: chenchiwu@ntuh.gov.tw.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material.

.

References

- 1.Wingard J.C., Zhao H.B. Cellular and deafness mechanisms underlying connexin mutation-induced hearing loss–a common hereditary deafness. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:202. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kenneson A., Van Naarden Braun K., Boyle C. GJB2 (connexin 26) variants and nonsyndromic sensorineural hearing loss: a HuGE review. Genet Med. 2002;4(4):258–274. doi: 10.1097/00125817-200207000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Snoeckx R.L., Huygen P.L., Feldmann D., Marlin S., Denoyelle F., et al. GJB2 mutations and degree of hearing loss: a multicenter study. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77(6):945–957. doi: 10.1086/497996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kikuchi T., Kimura R.S., Paul D.L., Adams J.C. Gap junctions in the rat cochlea: immunohistochemical and ultrastructural analysis. Anat Embryol. 1995;191(2):101–118. doi: 10.1007/BF00186783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forge A., Becker D., Casalotti S., Edwards J., Marziano N., Nevill G. Gap junctions in the inner ear: comparison of distribution patterns in different vertebrates and assessement of connexin composition in mammals. J Comp Neurol. 2003;467(2):207–231. doi: 10.1002/cne.10916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao H.B., Yu N. Distinct and gradient distributions of connexin26 and connexin30 in the cochlear sensory epithelium of guinea pigs. J Comp Neurol. 2006;499(3):506–518. doi: 10.1002/cne.21113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kelsell D.P., Dunlop J., Stevens H.P., Lench N.J., Liang J., et al. Connexin 26 mutations in hereditary non-syndromic sensorineural deafness. Nature. 1997;387:80–83. doi: 10.1038/387080a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wangemann P. K+ cycling and the endocochlear potential. Hear Res. 2002;165(1–2):1–9. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5955(02)00279-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen P., Wu W., Zhang J., Chen J., Li Y., et al. Pathological mechanisms of connexin26-related hearing loss: potassium recycling, ATP-calcium signaling, or energy supply? Front Mol Neurosci. 2022;15 doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2022.976388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beltramello M., Piazza V., Bukauskas F.F., Pozzan T., Mammano F. Impaired permeability to Ins (1, 4, 5) P3 in a mutant connexin underlies recessive hereditary deafness. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7(1):63–69. doi: 10.1038/ncb1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang Q., Tang W., Kim Y., Lin X. Timed conditional null of connexin26 in mice reveals temporary requirements of connexin26 in key cochlear developmental events before the onset of hearing. Neurobiol Dis. 2015;73:418–427. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Y., Chang Q., Tang W., Sun Y., Zhou B., et al. Targeted connexin26 ablation arrests postnatal development of the organ of Corti. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;385(1):33–37. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azaiez H., Booth K.T., Ephraim S.S., Crone B., Black-Ziegelbein E.A., et al. Genomic landscape and mutational signatures of deafness-associated genes. Am J Hum Genet. 2018;103(4):484–497. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uyguner O., Tukel T., Baykal C., Eris H., Emiroglu M., et al. The novel R75Q mutation in the GJB2 gene causes autosomal dominant hearing loss and palmoplantar keratoderma in a Turkish family. Clin Genet. 2002;62(4):306–309. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2002.620409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Löffler J., Nekahm D., Hirst-Stadlmann A., Günther B., Menzel H.J., et al. Sensorineural hearing loss and the incidence of Cx26 mutations in Austria. Eur J Hum Genet. 2001;9(3):226–230. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yum S.W., Zhang J., Scherer S.S. Dominant connexin26 mutants associated with human hearing loss have trans-dominant effects on connexin30. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;38(2):226–236. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen P.Y., Lin Y.H., Liu T.C., Lin Y.H., Tseng L.H., et al. Prediction model for audiological outcomes in patients with GJB2 mutations. Ear Hear. 2020;41(1):143–149. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan D.K., Chang K.W. GJB2–associated hearing loss: systematic review of worldwide prevalence, genotype, and auditory phenotype. Laryngoscope. 2014;124(2):E34–E53. doi: 10.1002/lary.24332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Q., Pierce-Hoffman E., Cummings B.B., Alföldi J., Francioli L.C., et al. Landscape of multi-nucleotide variants in 125,748 human exomes and 15,708 genomes. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1) doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12438-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abe S., Usami S.I., Shinkawa H., Kelley P.M., Kimberling W.J. Prevalent connexin 26 gene (GJB2) mutations in Japanese. J Med Genet. 2000;37(1):41–43. doi: 10.1136/jmg.37.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim S.Y., Park G., Han K.H., Kim A., Koo J.W., et al. Prevalence of p.V37I variant of GJB2 in mild or moderate hearing loss in a pediatric population and the interpretation of its pathogenicity. PLoS One. 2013;8(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wattanasirichaigoon D., Limwongse C., Jariengprasert C., Yenchitsomanus P., Tocharoenthanaphol C., et al. High prevalence of V37I genetic variant in the connexin‐26 (GJB2) gene among non‐syndromic hearing‐impaired and control Thai individuals. Clin Genet. 2004;66(5):452–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2004.00325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li L., Lu J., Tao Z., Huang Q., Chai Y., et al. The p.V37I exclusive genotype of GJB2: a genetic risk-indicator of postnatal permanent childhood hearing impairment. PLoS One. 2012;7(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hwa H.L., Ko T.M., Hsu C.J., Huang C.H., Chiang Y.L., et al. Mutation spectrum of the connexin 26 (GJB2) gene in Taiwanese patients with prelingual deafness. Genet Med. 2003;5(3):161–165. doi: 10.1097/00125817-200305000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chai Y., Chen D., Sun L., Li L., Chen Y., et al. The homozygous p.V37I variant of GJB2 is associated with diverse hearing phenotypes. Clin Genet. 2015;87(4):350–355. doi: 10.1111/cge.12387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pollak A., Skórka A., Mueller‐Malesińska M., Kostrzewa G., Kisiel B., et al. M34T and V37I mutations in GJB2 associated hearing impairment: evidence for pathogenicity and reduced penetrance. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2007;143A:2534–2543. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsukada K., Nishio S., Usami S., Consortium D.G.S. A large cohort study of GJB2 mutations in Japanese hearing loss patients. Clin Genet. 2010;78(5):464–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang S., Huang B., Wang G., Yuan Y., Dai P. The relationship between the p.V37I mutation in GJB2 and hearing phenotypes in Chinese individuals. PLoS One. 2015;10(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gallant E., Francey L., Tsai E.A., Berman M., Zhao Y., et al. Homozygosity for the V37I GJB2 mutation in fifteen probands with mild to moderate sensorineural hearing impairment: further confirmation of pathogenicity and haplotype analysis in Asian populations. Am J Med Genet Part A 161A. 2013:2148–2157. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kenna M.A., Feldman H.A., Neault M.W., Frangulov A., Wu B.L., et al. Audiologic phenotype and progression in GJB2 (Connexin 26) hearing loss. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;136(1):81–87. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2009.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu C.C., Tsai C.H., Hung C.C., Lin Y.H., Lin Y.H., et al. Newborn genetic screening for hearing impairment: a population-based longitudinal study. Genet Med. 2017;19(1):6–12. doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jara O., Acuña R., García I.E., Maripillán J., Figueroa V., et al. Critical role of the first transmembrane domain of Cx26 in regulating oligomerization and function. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23(17):3299–3311. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e11-12-1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oshima A., Tani K., Toloue M.M., Hiroaki Y., Smock A., et al. Asymmetric configurations and N-terminal rearrangements in connexin26 gap junction channels. J Mol Biol. 2011;405(3):724–735. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zonta F., Buratto D., Cassini C., Bortolozzi M., Mammano F. Molecular dynamics simulations highlight structural and functional alterations in deafness–related M34T mutation of connexin 26. Front Physiol. 2014;5:85. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Purnick P.E., Benjamin D.C., Verselis V.K., Bargiello T.A., Dowd T.L. Structure of the amino terminus of a gap junction protein. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;381(2):181–190. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oshima A., Doi T., Mitsuoka K., Maeda S., Fujiyoshi Y. Roles of Met-34, Cys-64, and Arg-75 in the assembly of human connexin 26: implication for key amino acid residues for channel formation and function. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(3):1807–1816. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207713200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oshima A. Structure and closure of connexin gap junction channels. FEBS Lett. 2014;588(8):1230–1237. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Batool A., Yasmeen S., Rashid S. T8M mutation in connexin-26 impairs the connexon topology and shifts its interaction paradigm with lipid bilayer leading to non-syndromic hearing loss. J Mol Liq. 2017;227:168–177. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2016.12.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.García I.E., Villanelo F., Contreras G.F., Pupo A., Pinto B.I., et al. The syndromic deafness mutation G12R impairs fast and slow gating in Cx26 hemichannels. J Gen Physiol. 2018;150(5):697–711. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201711782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Valdez Capuccino J.M., Chatterjee P., García I.E., Botello-Smith W.M., Zhang H., et al. The connexin26 human mutation N14K disrupts cytosolic intersubunit interactions and promotes channel opening. J Gen Physiol. 2019;151(3):328–341. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201812219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bruzzone R., Veronesi V., Gomes D., Bicego M., Duval N., et al. Loss-of-function and residual channel activity of connexin26 mutations associated with non-syndromic deafness. FEBS Lett. 2003;533:79–88. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)03755-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palmada M., Schmalisch K., Böhmer C., Schug N., Pfister M., et al. Loss of function mutations of the GJB2 gene detected in patients with DFNB1-associated hearing impairment. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;22(1):112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim J., Jung J., Lee M.G., Choi J.Y., Lee K.-A. Non-syndromic hearing loss caused by the dominant cis mutation R75Q with the recessive mutation V37I of the GJB2 (Connexin 26) gene. Exp Mol Med. 2015;47(6) doi: 10.1038/emm.2015.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Del Castillo F.J., Del Castillo I. DFNB1 non-syndromic hearing impairment: Diversity of mutations and associated phenotypes. Front Mol Neurosci. 2017;10 doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kmiecik S., Gront D., Kolinski M., Wieteska L., Dawid A.E., Kolinski A. Coarse-grained protein models and their applications. Chem Rev. 2016;116(14):7898–7936. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Monticelli L., Kandasamy S.K., Periole X., Larson R.G., Tieleman D.P., Marrink S.J. The MARTINI coarse-grained force field: extension to proteins. J Chem Theory Comput. 2008;4(5):819–e834. doi: 10.1021/ct700324x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Souza P.C., Alessandri R., Barnoud J., Thallmair S., Faustino I., et al. Martini 3: a general purpose force field for coarse-grained molecular dynamics. Nat Methods. 2021;18:382–388. doi: 10.1038/s41592-021-01098-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sengupta D., Chattopadhyay A. Identification of cholesterol binding sites in the serotonin1A receptor. J Phys Chem B. 2012;116(43):12991–12996. doi: 10.1021/jp309888u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Song W., Duncan A.L., Sansom M.S. Modulation of adenosine A2a receptor oligomerization by receptor activation and PIP2 interactions. Structure. 2021;29(11):1312–1325. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2021.06.015. e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maeda S., Nakagawa S., Suga M., Yamashita E., Oshima A., et al. Structure of the connexin 26 gap junction channel at 3.5 Å resolution. Nature. 2009;458:597–602. doi: 10.1038/nature07869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Biasini M., Bienert S., Waterhouse A., Arnold K., Studer G., et al. SWISS-MODEL: modelling protein tertiary and quaternary structure using evolutionary information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(W1):W252–W258. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen Y., Hu L., Wang X., Sun C., Lin X., et al. Characterization of a knock-in mouse model of the homozygous p.V37I variant in Gjb2. Sci Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep33279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Henikoff S., Henikoff J.G. Amino acid substitution matrices from protein blocks. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1992;89(22):10915–10919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zheng Q.Y., Johnson K.R., Erway L.C. Assessment of hearing in 80 inbred strains of mice by ABR threshold analyses. Hear Res. 1999;130(1–2):94–107. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5955(99)00003-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chang Q., Tang W., Ahmad S., Zhou B., Lin X. Gap junction mediated intercellular metabolite transfer in the cochlea is compromised in connexin30 null mice. PLoS One. 2008;3(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lu Y.C., Wu C.C., Yang T.H., Lin Y.H., Yu I.S., et al. Differences in the pathogenicity of the p.H723R mutation of the common deafness-associated SLC26A4 gene in humans and mice. PLoS One. 2013;8(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Valley C.C., Cembran A., Perlmutter J.D., Lewis A.K., Labello N.P., et al. The methionine-aromatic motif plays a unique role in stabilizing protein structure. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(42):34979–34991. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.374504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bennett B.C., Purdy M.D., Baker K.A., Acharya C., McIntire W.E., Stevens R.C., et al. An electrostatic mechanism for Ca2+-mediated regulation of gap junction channels. Nat Commun. 2016;7 doi: 10.1038/ncomms9770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Khan A.K., Jagielnicki M., McIntire W.E., Purdy M.D., Dharmarajan V., Griffin P.R., et al. A steric “ball-and-chain” mechanism for pH-mediated regulation of gap junction channels. Cell Rep. 2020;31(3) doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.03.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bahar I., Jernigan R.L. Inter-residue potentials in globular proteins and the dominance of highly specific hydrophilic interactions at close separation. J Mol Biol. 1997;266(1):195–214. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Huang J., Rauscher S., Nawrocki G., Ran T., Feig M., et al. CHARMM36m: an improved force field for folded and intrinsically disordered proteins. Nat Methods. 2017;14:71–73. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Eastman P., Swails J., Chodera J.D., McGibbon R.T., Zhao Y., et al. OpenMM 7: rapid development of high performance algorithms for molecular dynamics. PLoS Comput Biol. 2017;13(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Araya-Secchi R., Perez-Acle T., Kang S.G., Huynh T., Bernardin A., et al. Characterization of a novel water pocket inside the human Cx26 hemichannel structure. Biophys J. 2014;107(3):599–612. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zonta F., Girotto G., Buratto D., Crispino G., Morgan A., et al. The p.Cys169Tyr variant of connexin 26 is not a polymorphism. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24(9):2641–2648. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Abbott A.C., García I.E., Villanelo F., Flores-Muñoz C., Ceriani R., et al. Expression of KID syndromic mutation Cx26S17F produces hyperactive hemichannels in supporting cells of the organ of Corti. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2023;10:2457. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2022.1071202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zonta F., Buratto D., Crispino G., Carrer A., Bruno F., et al. Cues to opening mechanisms from in silico electric field excitation of Cx26 hemichannel and in vitro mutagenesis studies in HeLa transfectans. Front Mol Neurosci. 2018;11 doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhou X.X., Chen S., Xie L., Ji Y.Z., Wu X., et al. Reduced connexin26 in the mature cochlea increases susceptibility to noise-induced hearing loss in mice. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(3):301. doi: 10.3390/ijms17030301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pawelczyk M., Van Laer L., Fransen E., Rajkowska E., Konings A., et al. Analysis of gene polymorphisms associated with K+ Ion circulation in the inner ear of patients susceptible and resistant to noise‐induced hearing loss. Ann Hum Genet. 2009;73(4):411–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2009.00521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li W.S., Gang Y.L., Ping L.R., Zhan Z.W., Min G.W., et al. Gene-gene interaction of GJB2, SOD2, and CAT on occupational noise-induced hearing loss in Chinese Han population. Biomed Environ Sci. 2014;27(12):965–968. doi: 10.3967/bes2014.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zdebik A.A., Wangemann P., Jentsch T.J. Potassium ion movement in the inner ear: insights from genetic disease and mouse models. Physiology. 2009;24(5):307–316. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00018.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cohen-Salmon M., Ott T., Michel V., Hardelin J.P., Perfettini I., et al. Targeted ablation of connexin26 in the inner ear epithelial gap junction network causes hearing impairment and cell death. Curr Biol. 2002;12(13):1106–1111. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)00904-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sinyuk M., Mulkearns-Hubert E.E., Reizes O., Lathia J. Cancer connectors: connexins, gap junctions, and communication. Front Oncol. 2018;8 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ito A., Katoh F., Kataoka T.R., Okada M., Tsubota N., et al. A role for heterologous gap junctions between melanoma and endothelial cells in metastasis. J Clin Invest. 2000;105(9):1189–1197. doi: 10.1172/JCI8257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Momiyama M., Omori Y., Ishizaki Y., Nishikawa Y., Tokairin T., et al. Connexin26–mediated gap junctional communication reverses the malignant phenotype of MCF‐7 breast cancer cells. Cancer Sci. 2003;94(6):501–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01473.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Myers J.B., Haddad B.G., O’Neill S.E., Chorev D.S., Yoshioka C.C., et al. Structure of native lens connexin 46/50 intercellular channels by cryo-EM. Nature. 2018;564:372–377. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0786-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Thönnissen E., Rabionet R., Arbonès M., Estivill X., Willecke K., Ott T. Human connexin26 (GJB2) deafness mutations affect the function of gap junction channels at different levels of protein expression. Hum Genet. 2002;111:190–197. doi: 10.1007/s00439-002-0750-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Xiao Z., Yang Z., Liu X., Xie D. Impaired membrane targeting and aberrant cellular localization of human Cx26 mutants associated with inherited recessive hearing loss. Acta Otolaryngol. 2011;131(1):59–66. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2010.506885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cook J., de Wolf E., Dale N. Cx26 keratitis ichthyosis deafness syndrome mutations trigger alternative splicing of Cx26 to prevent expression and cause toxicity in vitro. R Soc Open Sci. 2019;6(8) doi: 10.1098/rsos.191128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang J., Liu J., Gisriel C.J., Wu S., Maschietto F., Flesher D.A., et al. How to correct relative voxel scale factors for calculations of vector-difference Fourier maps in cryo-EM. J Struct Biol. 2022;214(4) doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2022.107902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wang J., Shi Y., Reiss K., Maschietto F., Lolis E., Konigsberg W.H., et al. Structural Insights into Binding of Remdesivir Triphosphate within the Replication–Transcription Complex of SARS-CoV-2. Biochemistry. 2022;61(18):1966–1973. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.2c00341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cama E., Melchionda S., Palladino T., Carella M., Santarelli R., et al. Hearing loss features in GJB2 biallelic mutations and GJB2/GJB6 digenic inheritance in a large Italian cohort. Int J Audio. 2009;48(1):12–17. doi: 10.1080/14992020802400654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chen K., Wu X., Zong L., Jiang H. GJB3/GJB6 screening in GJB2 carriers with idiopathic hearing loss: Is it necessary? J Clin Lab Anal. 2018;32 doi: 10.1002/jcla.22592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]