Summary

Background

Infectious diseases and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has become pressing concerns in China. We aimed to comprehensively investigate the burden of them.

Methods

Data on infectious diseases and AMR were collected by the Global Antimicrobial Resistance Burden study 2019. Multinomial network meta-regression, logistic regression, and ensemble Spatiotemporal Gaussian process regression were used to fit the number and rate in DisMod-MR 2.1 modelling framework. We reported the number and rates of the disease burdens of 12 infectious syndromes by age and sex; described the burden caused by 43 pathogens; estimated the AMR burden of 22 bacteria and bacteria–antibiotics combinations.

Findings

There were an estimated 1.3 million (95% uncertainty intervals, UI 0.8–1.9) infection-related deaths, accounting for 12.1% of the total deaths in China 2019. Males were 1.5 times more affected than females. Bloodstream infections (BSIs) were most lethal infectious syndrome, associating with 521,392 deaths (286,307–870,583), followed by lower respiratory infections (373,175), and peritoneal and intra-abdominal infections (152,087). These five leading pathogens were S aureus, A baumannii, E coli, S pneumoniae, and E spp., which were associated with 41.2% (502,658/1,218,693) of all infection-related deaths. The pathogens of different infectious syndromes exhibited significant heterogeneity. In 2019, more than 600 thousand deaths were associated with AMR, including 145 thousand deaths attributable to AMR. The top 3 AMR attributable to death were carbapenems-resistance A baumannii (18,143), methicillin-resistance S aureus (16,933) and third-generation cephalosporins-resistance E coli (8032).

Interpretation

Infectious diseases and bacterial antimicrobial resistance were serious threat to public health in China, related to 1.3 million and more than 600 thousand deaths per-year, respectively. Antimicrobial stewardship was urgent.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (82270626); China Mega-Project for Infectious Diseases (2017ZX10203202, 2013ZX10002005); the Project of Beijing Science and Technology Committee (Z191100007619037).

Keywords: Burden of infectious diseases, Antimicrobial resistance, Death, DALYs, China

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We used the key words “burden”, “infectious diseases”, “antimicrobial resistance”, “incidence”, and “mortality” to search in PubMed database from inception to April 8, 2022. GBD 2019 Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators study showed that 13.7 million people died of infectious diseases in 2019 globally. Five leading pathogens-S aureus, E coli, S pneumoniae, K pneumoniae, and P aeruginosa were responsible for 54.9% of deaths among the investigated bacteria. Furthermore, there were an estimated 4.95 million deaths associated with bacterial AMR, including 1.27 million deaths attributable to bacterial AMR. The six leading pathogens for deaths associated with resistance (E coli, followed by S aureus, K pneumoniae, S pneumoniae, A baumannii, and P aeruginosa) were responsible for 929,000 deaths attributable to AMR and 3.57 million deaths associated with AMR in 2019. An epidemiological study in China showed that only 15% of outpatient prescriptions containing antibiotics issued from 2014 to 2018 were reasonable, while 51% were clearly unreasonable. The total number of unreasonable antibiotic prescriptions in China each year may exceed 173 million. However, to the best of our knowledge, there was no systematic report on the burden of infectious diseases and bacterial antimicrobial resistance in China. Therefore, it was necessary for us to comprehensively investigate the burden of infectious diseases and AMR in China.

Added value of this study

We used data from the subset of input data describing China from the Global Antimicrobial Resistance Burden study. Our analyses showed that infectious diseases were a clinically significant cause of health loss, accounting for 12.1% (1.3 million) of the total deaths in China. Three mainly infectious syndromes accounted for 82.2% of deaths in 2019: bloodstream infections, lower respiratory infections, and peritoneal and intra-abdominal infections. These five leading pathogens were S aureus, A baumannii, E coli, S pneumoniae, and E spp., which were associated with 41.2% of all infection-related deaths. In 2019, 0.6 million deaths were associated with bacterial AMR, including 0.15 million deaths attributable to bacterial AMR. The top 3 AMR attributable to death were carbapenems-resistance A baumannii, methicillin-resistance S aureus and third-generation cephalosporins-resistance E coli.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our estimates indicated that deaths caused by infectious diseases, especially drug-resistant bacteria, was a significant issue that could not be overlooked in China. Bloodstream infections was the predominant cause of mortality. S aureus, A baumannii, and E coli were the main antibiotic-resistant microorganisms. Reducing mortality required collective action from the entire society: strengthen infection control measures in medical institutions (such as aseptic surgery); hand hygiene of medical staff; early identification of mild to moderate infections and rational use of antibiotics; researching priorities in the field of antibiotics and vaccines; rationale using of antibiotics in agriculture and the environment; patient awareness.

Introduction

Among the top ten global health threats released by World Health Organization (WHO) in 2019, six were related to infectious diseases (global influenza pandemic; antimicrobial resistance; Ebola and other high-threat pathogens; vaccine hesitancy; dengue; HIV).1 It was estimated that in 2019, the number of deaths due to infectious diseases was 13.7 million (95% uncertainty intervals, UI 10.9–17.1), while deaths associated with bacteria ranked as the second leading cause of death globally.2 Whether on a global scale or within China, the issue of bacterial antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has become a pressing concern. It was estimated that AMR cause 1.27 million (95% UI 0.911–1.71) deaths directly, and contribute to 4.95 million (95% UI 3.62–6.57) deaths indirectly worldwide.3 Globally, lower respiratory infections were responsible for over 1.5 million deaths associated with resistance, making it the most burdensome infectious syndrome.3 A meta-analysis by Allel et al., which included 109 studies (49 from China) from low and middle-income countries, showed that compared with antibiotic-sensitive bacteria, antibiotic-resistant bacteria significantly increased the crude mortality (odds ratio, OR 1.58, 95% UI [1.35–1.80]), total length of hospital stay (standardized mean difference, SMD 0.49, 95% UI [0.20–0.78]), and ICU admission (OR 1.96, 95% UI [1.56–2.47]) in bloodstream infections. Besides, the total excess hospital cost per patient exceeded $10,000, while the total excess cost and productivity loss caused by premature death was approximately $70,000 in China.4 By 2050, antibiotic-resistant bacteria are projected to claim the lives of 10 million people annually, surpassing deaths caused by malignant tumors.5

The burden of infectious diseases in China were also substantial. A sepsis epidemiological survey among residents in the Yuetan Subdistrict, Beijing with 21,191 residents between 2012 and 2014 revealed that the incidence rates of sepsis, severe sepsis, and septic shock were 667 cases, 103 cases, and 91 cases per 100,000 population, respectively. The overall hospital mortality rate for sepsis was 20.6%, and the standardized mortality rate was 79 cases per 100,000 population.6 Additionally, a nationwide descriptive analysis showed that there was a total of 1,025,997 cases of sepsis-related deaths in China in 2015. Male gender (relative risk, RR 1.58, 95% UI 1.57–1.60), increasing age (5-year group, RR 1.91, 95% UI 1.91–1.92), and underlying comorbidities (RR 2.32, 95% UI 2.30–2.34) were associated with increased mortality.7 The China antimicrobial surveillance network (CHINET) indicated that in the total of 339,513 strains in 2022, Escherichia coli (18.69%), Klebsiella pneumoniae (13.99%), Staphylococcus aureus (9.47%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (8.03%), and Acinetobacter baumannii (7.5%) ranked the 5 leading pathogens.8 Moreover, Zhao et al. study (data from 139 hospitals in 28 provincial-level regions in Chinese Mainland) indicated that over half of the antibiotic prescriptions were inappropriate each year in secondary-level and tertiary-level hospitals, exceeding 173 million.9

Given the current severe situation of infectious diseases and antibiotic resistance in China, it was necessary for us to systematically clarify the burden of infectious diseases, and rationale use of antibiotics. This study aimed to comprehensively investigate the burden infectious diseases by syndromes and pathogens. Then, we portrayed the burden of AMR by infectious syndromes, pathogens, and species and pathogen-drug combinations.

Methods

Overview and data sources

In this study, we used a subset of input data describing China from the Global Antimicrobial Resistance Burden (GARB) study to estimate the burden of infectious diseases and bacterial antimicrobial resistance.2,3 The global overall input data from 471.3 million sample size and 9324 number of study-location-years. A total of 142 inputted data, including 24 administrative data, 15 epi surveillances, 1 modeled data, 4 reports, 96 scientific literatures, and 2 surveys, were available for mainland China (Table S1). The input data can be categorized into the 10 types: multiple causes of death and vital registration (MCoD-VR), hospital discharge, microbial data with outcome, microbial data without outcome, literature studies, single drug–resistance profiles, pharmaceutical sales and antibiotic use, antibiotic use among children younger than 5 years with reported illness, mortality surveillance, linkage (mortality only). The data input sources (could be found at: https://ghdx.healthdata.org/record/ihme-data/global-bacterial-antimicrobial-resistance-burden-estimates-2019) in the GARB study included nine categories: administrative data, demographic surveillance, epi surveillance, estimate, modeled data, report, scientific literature, survey, and vital registration. The data for this study were obtained from a publicly available database and did not require ethical review or informed consent.

Estimation steps

Detailed methods on the estimation process for infectious syndromes and AMR have been published previously.2,3,10 The estimation consisted of 5 steps (Figure S1):

Estimation steps 1: deaths in which infection played a role by infectious syndrome. We used data from multiple causes of death to develop random-effects logistic regression models to predict each communicable and non-communicable cause of death. We then multiplied the sepsis fraction predicted by the logistic regression model by the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) cause-specific mortality estimates to determine the mortality envelope.

where is sex and healthcare access and quality index, as a covariate and a nested random effect; is a nested random effect on underlying cause of death.

Next, we further subdivided the causes of death into 12 major infection syndromes and one residual category using multiple detailed causes of death in a second stage random effects logistic regression model.

where is a nested random effect on underlying cause of death.

Estimation steps 2: pathogen distribution for deaths and incident cases. Data linking pathogen-specific disease incidence and mortality rates was used to develop pathogen-specific case-fatality rate (CFR) models that vary by age and syndrome. Then, we used the Bayesian meta-regression tool MR-BRT to estimate CFR as functions of healthcare access and quality indices, as well as various bias covariates. To integrate these heterogeneous data, polynomial estimation with partial and composite observations were used to develop models.

where = number of cases of pathogen in a total sample of infections ().

Modelling the probabilities using a composition of a link function with a linear predictor:

for observations , a vector of covariates , and a vector of coefficients for each pathogen .

These models allowed for the inclusion of covariates in network analysis and permits the inclusion of Bayesian prior probability distributions.

Estimation steps 3: prevalence of resistance by pathogen. We used data from 52.8 million isolations to analyze the proportion of AMR for each pathogen-drug combination. Antibiotic consumption at the national level as a covariate in the stacked ensemble models for the prevalence of resistance was also considered.

Estimation steps 4: relative risk of death for drug-resistant infection compared with drug-sensitive infections. We estimated the relative risk of death for each pathogen-drug combination using a two-stage nested mixed-effects meta-regression model (age, admission diagnosis, hospital-acquired vs. community-acquired infections, and site of infection as covariates). To estimate the burden of multiple pathogen-drug combinations that were mutually exclusive within a given pathogen, we generated population attributable fractions (PAF) for each resistance spectrum with resistance to at least one drug. Based on an international expert consensus, multidrug-resistant bacteria was defined as acquired non-susceptibility to at least one agent in three or more antimicrobial categories.11

Estimation step 5: computing burden attributable to drug resistance and burden associated with drug-resistant infections. We calculated two counterfactuals to estimate drug resistance burden: the bacterial resistance burden based on the counterfactual of drug-sensitive infections and the bacterial resistance-related burden based on the counterfactual of no infections. Disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) were the sum of YLLs and YLDs.

Deaths associated with resistance was calculated by:

where = deaths, = fraction related to infection, = infectious syndrome fraction, = fatal pathogen fraction, = fatal prevalence of resistance, = cause, = syndrome, = pathogen, = drug.

Deaths attributable to resistance was calculated by:

where is the drug in the resistance profile with the highest relative risk; = deaths, = fraction related to infection, = infectious syndrome fraction, = fatal pathogen fraction, = fatal prevalence of resistance, = cause, = syndrome, = pathogen, = drug.

Analysis steps

Our analysis consisted of 5 main steps. In step 1, we estimated the disease burdens (death number/rate, DALYs number/rate) of the total and 12 infectious syndromes (Table 1) in China in 2019 by age and sex. In step 2, we described the disease burden (death number/rate, DALYs number/rate) caused by 43 pathogens and estimated the proportion of pathogens in different infection syndromes. These 43 microorganisms were in 6 major categories: 34 bacteria, 4 viruses, 2 protozoa, fungi, polymicrobial, and other pathogens (Table S2).

Table 1.

Death and DALYs burden of infectious syndrome in China, 2019.

| Deaths |

DALYs |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (95% UI) | Rate, per 100,000 (95% UI) | Number (95% UI) | Rate, per 100,000 (95% UI) | |

| All infectious syndromes | 1,272,747 (837,156–1,904,522) | 89.5 (58.9–133.9) | 35,499,953 (24,400,822–52,030,412) | 2495.9 (1715.5–3658.1) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 501,247 (329,528–760,664) | 71.9 (47.2–109.1) | 13,293,669 (9,172,598–19,605,430) | 1905.8 (1315.0–2810.7) |

| Male | 771,500 (488,058–1,170,858) | 106.4 (67.3–161.5) | 22,206,253 (14,870,721–32,992,850) | 3063.7 (2051.6–4551.9) |

| Infectious syndrome | ||||

| Bloodstream infections | 521,392 (286,307–870,583) | 36.7 (20.1–61.2) | 12,989,294 (7,263,020–21,411,719) | 913.2 (510.6–1505.4) |

| Lower respiratory infections and all related infections in the thorax | 373,175 (268,557–526,381) | 26.2 (18.9–37) | 7,657,177 (5,584,127–10,511,742) | 538.3 (392.6–739) |

| Peritoneal and intra-abdominal infections | 152,087 (89,323–250,500) | 10.7 (6.3–17.6) | 3,811,459 (2,140,611–6,405,286) | 268 (150.5–450.3) |

| Bacterial infections of the skin and subcutaneous systems | 54,872 (14,406–130,989) | 3.9 (1–9.2) | 1,117,429 (307,726–2,675,670) | 78.6 (21.6–188.1) |

| Urinary tract infections and pyelonephritis | 40,244 (18,267–74,036) | 2.8 (1.3–5.2) | 836,355 (391,753–1,546,148) | 58.8 (27.5–108.7) |

| Tuberculosis | 36,566 (30,863–42,824) | 2.6 (2.2–3) | 1,373,596 (1,117,708–1,694,750) | 96.6 (78.6–119.2) |

| Endocarditis and other cardiac infections | 13,042 (7097–22,096) | 0.9 (0.5–1.6) | 336,061 (186,728–560,171) | 23.6 (13.1–39.4) |

| Diarrhea | 11,460 (6557–20,625) | 0.8 (0.5–1.5) | 1,641,428 (890,474–3,190,267) | 115.4 (62.6–224.3) |

| Meningitis and other bacterial central nervous system infections | 9088 (5467–16,504) | 0.6 (0.4–1.2) | 386,802 (229,678–687,863) | 27.2 (16.1–48.4) |

| Infections of bones, joints, and related organs | 5343 (1632–12,522) | 0.4 (0.1–0.9) | 123,220 (36,575–290,843) | 8.7 (2.6–20.4) |

| Typhoid fever, paratyphoid fever, and invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella | 1173 (710–1853) | 0.1 (0–0.1) | 67,914 (38,814–110,988) | 4.8 (2.7–7.8) |

| Gonorrhoea and chlamydia | 253 (188–314) | 0 (0–0) | 41,933 (27,706–60,163) | 2.9 (1.9–4.2) |

In step 3, we calculated the disease burden of total and 12 infection syndromes caused by bacterial AMR in two scenarios (AMR associated deaths, AMR attributable deaths), respectively. Associated deaths were the inclusive estimate of AMR burden, which measures people with a drug-resistant infection that contributed to their death. The infection was implicated in their death, but resistance may or may not have been a factor. Attributable deaths were the conservative estimate of AMR burden, which measures people who would not have died of infection if it was treatable (i.e., if there was no AMR).12 In step 4, we estimated the AMR burden (death number/rate, DALYs number/rate) of 22 bacteria in aforementioned two scenarios. In step 5, we calculated the burden of AMR by 22 bacteria and 19 antibiotics combinations (Table S3). This study was reported in accordance with the Guidelines for Accurate and Transparent Health Estimates Reporting (GATHER) statement (Table S7).

Role of the funding source

All funders had no role in study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The data for this study is sourced from public databases and previously published literature, therefore it was exempt from approval by the Ethics Committee.

Results

Burden of infectious diseases by syndromes

In 2019, there were an estimated 1.3 million (95% UI 0.8–1.9) infection-related deaths in China, accounting for 12.1% of the total deaths for that year (10.7 million [95% UI 9.3–12.1]13), and 9.5% of the total deaths related to infections worldwide (13.7 million [95% UI 10.9–17.1]2). Males were 1.5 times more affected than females (0.8 million [0.5–1.2] vs. 0.5 million [0.3–0.8], Table 1). Only bloodstream infections (BSIs) were associated with more than 500,000 deaths in 2019 (521,392 [286,307–870,583]). Two additional infectious syndromes were associated with more than 100,000 deaths each in 2019: lower respiratory infections (373,175 [268,557–526,381]), and peritoneal and intra-abdominal infections (152,087 [89,323–250,500]). Combined, these three syndromes accounted for 82.2% of deaths attributable to sepsis in 2019.

The number of DALYs were 35.5 (24.4–52.0) million, with males experiencing 1.7 times more DALYs than females (Table 1, Figure S2). The DALYs rates for males and females were 3063.7 (2051.6–4551.9) and 1905.8 (1315.0–2810.7) per 100,000 population, respectively. The leading three infectious syndromes by DALYs burden were similar with the mortality estimates: BSIs were associated with the greatest DALYs burden with 13.0 million (7.3–21.4) DALYs.

The number of deaths from infectious syndrome in males exceeded that in females, except for gonorrhoea and chlamydia (Fig. 1). Most deaths from infectious syndromes occurred in people over 50 years of age. Deaths from diarrhea and meningitis and other bacterial central nervous system infections had two peaks, one in children under 5 years old and the other in people over 50 years old. Typhoid fever, paratyphoid fever, and invasive non-typhoidal salmonella mainly occurred in children and young adults aged under 30 years old (54.8%). The rate of deaths and DALYs across different sex and ages were shown in Figure S3 and Figure S4.

Fig. 1.

Number of deaths in different infectious syndrome by age group and sex in 2019. Bacterial infections of the skin: Bacterial infections of the skin and subcutaneous systems; Endocarditis: Endocarditis and other cardiac infections; Infections of bones: Infections of bones, joints, and related organs; Lower respiratory infections: Lower respiratory infections and all related infections in the thorax; Meningitis: Meningitis and other bacterial central nervous system infections; Peritoneal infections: Peritoneal and intra-abdominal infections; Typhoid fever: Typhoid fever, paratyphoid fever, and invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella; Urinary tract infections: Urinary tract infections and pyelonephritis; Neonatal: <28 days; Post-neonatal: 28 days to <1 year old.

Burden of infectious diseases by pathogens

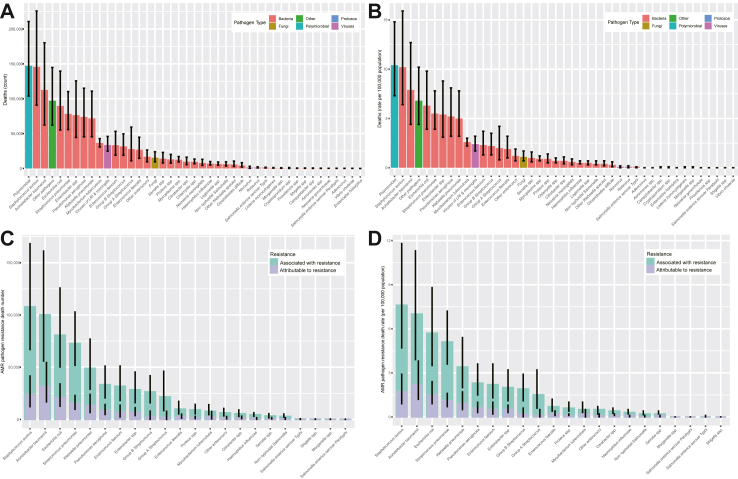

Among all age groups, and both sexes, the most common organism was polymicrobial infections 147,258 (103,762–210,754) (Fig. 2). The five leading pathogens were Staphylococcus aureus (145,711 [90,858–225,824]), Acinetobacter baumannii (112,621 [62,397–180,317]), Escherichia coli (89,670 [55,253–139,629]), Streptococcus pneumoniae (78,296 [55,839–110,279]), and Enterobacter spp. (76,360 [44,537–125,668]), which were associated with 41.2% (502,658/1,218,693) of all infection-related deaths. Two additional pathogens were associated with more than 50,000 deaths each in 2019: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Klebsiella pneumoniae. The deaths number caused by fungal sepsis exceeded 10,000 cases (15,431 [9465–24,050]).

Fig. 2.

Number and rate of deaths by pathogens and antimicrobial resistance in China, 2019. (A) Number of deaths by pathogens; (B) Rate of deaths by pathogens; (C) Number of deaths by antimicrobial resistance; (D) Rate of deaths by antimicrobial resistance. The black vertical line represented the 95% confidence interval. “Other pathogens” represented the sum of residual categories of all pathogens that were not explicitly estimated.

The pathogens of different infectious syndromes exhibited significant heterogeneity (Fig. 1, Figure S5, and Figure S6). The three leading bacteria causing deaths in BSIs were Acinetobacter baumannii (93,719 [49,711–157,179]), Staphylococcus aureus (75,329 [41,466–126,241]), and Enterobacter spp. (56,737 [31,039–95,728]), which accounted for 43.3% of all deaths from BSIs. Meanwhile, Polymicrobial, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Staphylococcus aureus were the most common bacteria in lower respiratory infections, accounting for 52.6% (196,284/373,175) of this infection syndrome death counts. The most common bacterium causing death in peritoneal and intra-abdominal infections was Escherichia coli (36,753 [21,522–60,189], Figure S8).

Burden of AMR by infectious syndromes

It was estimated that 602,561 (378,084–928,696) deaths were associated with bacterial AMR, accounting for 12.2% of the total deaths related to AMR worldwide (4.95 million [3.62–6.57]3), with the rate of 42.4 (26.6–65.3) per 100,000 population. There were 145,465 (89,593–222,609) deaths were directly attributable to resistance, accounting for 11.4% of the total deaths related to AMR worldwide (1.27 million [0.91–1.71]3), with the rate of 10.2 (6.3–15.7) per 100,000 population (Table 2). The largest lethal burden in China came from BSIs (290,481 deaths [159,641–486,428] or 48.2%), followed by lower respiratory infections (134,188 deaths [93,075–193,120] or 22.3%) and peritoneal and intra-abdominal infections (93,968 deaths [55,059–154,951] or 15.6%). Combined, these three fatal infectious syndromes accounted for 86.1% of deaths attributable to AMR in 2019. The three infectious syndromes dominated the burdens attributable to AMR (87.3%, 126,973/145,465) in 2019 also: with the count of deaths 73,173 (38,183–121,964), 30,569 (19,979–45,195), and 23,231 (13,475–38,805), separately. BSIs alone accounted for more than 50% attributable deaths (50.3%, 73,173/145,465).

Table 2.

Deaths and DALYs (in counts and all-age rates) associated with and attributable to bacterial antimicrobial resistance in China, 2019.

| Associated with resistance |

Attributable to resistance |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deaths |

DALYs |

Deaths |

DALYs |

|||||

| Number (95% UI) | Rate, per 100,000 (95% UI) | Number (95% UI) | Rate, per 100,000 (95% UI) | Number (95% UI) | Rate, per 100,000 (95% UI) | Number (95% UI) | Rate, per 100,000 (95% UI) | |

| All infectious syndromes | 602,561 (378,084–928,696) | 42.4 (26.6–65.3) | 14,583,291 (9,193,347–22,463,290) | 1025.3 (646.3–1579.3) | 145,465 (89,593–222,609) | 10.2 (6.3–15.7) | 3,457,030 (2,144,036–5,328,606) | 243.1 (150.7–374.6) |

| Infectious syndrome | ||||||||

| Bloodstream infections | 290,481 (159,641–486,428) | 20.4 (11.2–34.2) | 7,076,456 (3,890,686–11,577,398) | 497.5 (273.5–814) | 73,173 (38,183–121,964) | 5.1 (2.7–8.6) | 1,753,840 (941,902–2,913,997) | 123.3 (66.2–204.9) |

| Lower respiratory infections and all related infections in the thorax | 134,188 (93,075–193,120) | 9.4 (6.5–13.6) | 3,034,796 (2,191,306–4,225,035) | 213.4 (154.1–297) | 30,569 (19,979–45,195) | 2.1 (1.4–3.2) | 681,843 (464,594–988,283) | 47.9 (32.7–69.5) |

| Peritoneal and intra-abdominal infections | 93,968 (55,059–154,951) | 6.6 (3.9–10.9) | 2,333,171 (1,323,192–3,944,295) | 164 (93–277.3) | 23,231 (13,475–38,805) | 1.6 (0.9–2.7) | 575,375 (324,470–968,793) | 40.5 (22.8–68.1) |

| Bacterial infections of the skin and subcutaneous systems | 32,066 (8286–80,488) | 2.3 (0.6–5.7) | 658,886 (182,680–1,646,088) | 46.3 (12.8–115.7) | 4965 (942–14,049) | 0.3 (0.1–1) | 102,381 (21,193–293,030) | 7.2 (1.5–20.6) |

| Urinary tract infections and pyelonephritis | 27,112 (12,365–50,066) | 1.9 (0.9–3.5) | 571,407 (266,612–1,061,676) | 40.2 (18.7–74.6) | 6830 (3065–12,928) | 0.5 (0.2–0.9) | 143,753 (65,980–270,988) | 10.1 (4.6–19.1) |

| Endocarditis and other cardiac infections | 8283 (4519–13,993) | 0.6 (0.3–1) | 213,417 (118,418–355,119) | 15 (8.3–25) | 2075 (1132–3524) | 0.1 (0.1–0.2) | 52,365 (28,933–86,853) | 3.7 (2–6.1) |

| Tuberculosis | 7765 (4598–14,120) | 0.5 (0.3–1) | 269,628 (166,163–479,953) | 19 (11.7–33.7) | 2831 (568–7550) | 0.2 (0–0.5) | 74,854 (17,217–193,791) | 5.3 (1.2–13.6) |

| Meningitis and other bacterial central nervous system infections | 4342 (2628–7943) | 0.3 (0.2–0.6) | 177,682 (105,959–311,601) | 12.5 (7.4–21.9) | 951 (539–1734) | 0.1 (0–0.1) | 38,094 (22,075–66,161) | 2.7 (1.6–4.7) |

| Infections of bones, joints, and related organs | 3337 (1016–7802) | 0.2 (0.1–0.5) | 77,295 (22,843–183,567) | 5.4 (1.6–12.9) | 630 (185–1525) | 0 (0–0.1) | 14,443 (4067–35,782) | 1 (0.3–2.5) |

| Typhoid fever, paratyphoid fever, and invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella | 541 (304–938) | 0 (0–0.1) | 31,144 (17,224–56,019) | 2.2 (1.2–3.9) | 111 (39–238) | 0 (0–0) | 6337 (2123–13,698) | 0.4 (0.1–1) |

| Diarrhea | 479 (185–1099) | 0 (0–0.1) | 131,120 (28,729–376,200) | 9.2 (2–26.4) | 100 (26–254) | 0 (0–0) | 12,808 (2000–39,715) | 0.9 (0.1–2.8) |

| Gonorrhoea and chlamydia | – | – | 8288 (4360–14,020) | 0.6 (0.3–1) | – | – | 936 (352–1821) | 0.1 (0–0.1) |

The total burden of AMR DALYs in 2019 to be 14,583,291 (9,193,347–22,463,290) associated with AMR and 3,457,030 (2,144,036–5,328,606) attributable to AMR. The preponderant three infectious syndromes by DALYs burden were similar with the associated with (or attributable to) resistance estimated counts. Table 2 provided detailed estimates of deaths and DALYs from AMR for 12 infectious syndromes.

Burden of AMR by pathogens

In 2019, nine pathogens were responsible for more than 25,000 deaths associated with AMR (Fig. 2): Staphylococcus aureus (107,800 deaths), Acinetobacter baumannii (100,114 deaths), Escherichia coli (80,623 deaths), Streptococcus pneumoniae (72,724 deaths), Klebsiella pneumoniae (48,939 deaths), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (33,353 deaths), Enterococcus faecium (31,803 deaths), Enterobacter spp. (28,423 deaths), and Group B Streptococcus (26,425 deaths) by order of number of deaths. Together, these nine pathogens were responsible for 88.0% (530,204/602,562) associated with AMR in 2019. For deaths attributable to AMR, Acinetobacter baumannii (31,581 deaths) was responsible for the most deaths in 2019, followed by Staphylococcus aureus (23,750 deaths), Escherichia coli (20,951 deaths), Streptococcus pneumoniae (15,434 deaths), and Klebsiella pneumoniae (13,431 deaths).

Five pathogens were responsible for more than 1 million DALYs associated with AMR (Figure S7): Staphylococcus aureus (2,497,398 DALYs), Acinetobacter baumannii (2,287,442 DALYs), Streptococcus pneumoniae (1,875,144 DALYs), Escherichia coli (1,829,790 DALYs), and Klebsiella pneumoniae (1,126,193 DALYs). The five leading pathogens accounted for 65.9% associated DALYs.

Burden of AMR by species and pathogen-drug combinations

Regarding specific pathogen-drug combinations, seven antibiotics were responsible for more than 100,000 deaths associated with pathogens (Fig. 3A): fluoroquinolones (262,127 deaths), third-generation cephalosporins (220,870 deaths), macrolides (217,531 deaths), carbapenems (166,056 deaths), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (164,768 deaths), beta lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitors (145,604 deaths), and fourth-generation cephalosporins (108,399 deaths). Thirteen pathogen-drug combinations each caused between 50,000 and 100,000 resistance-attributable deaths in 2019 (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Number of bacterial antimicrobial resistance deaths by pathogen-drug combination in China, 2019. (A) associated with deaths; (B) attributable to deaths.

In 2019, carbapenems resistance Acinetobacter baumannii (18,143 deaths), and methicillin resistance Staphylococcus aureus (16,933 deaths) were the two pathogen-drug combinations with more than 10,000 deaths attributable to resistance (Fig. 3B). Six combinations each caused between 5000 and 10,000 deaths attributable to AMR (Fig. 3B). Associated with and attributable to AMR for pathogen-drug combinations death rate (Table S4), DALYs counts (Table S5), and DALYs rate (Table S6) were shown in Supplementary Material.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study was the first comprehensive report of the burden of infectious diseases and AMR in China. It was estimated that 1.3 million deaths were attributed to infections, which accounted for 12.1% of the total deaths during in China, 2019.14 The AMR burden assessed across 88 pathogen-drug combinations in 2019 was an estimated 602,561 (378,084–928,696) deaths, of which 145,465 (89,593–222,609) deaths were directly attributable to drug resistance. In other words, if all drug-resistant infections were replaced by no infection, 600 thousand deaths could have been prevented in 2019. Alternatively, if all drug-resistant infections were replaced by drug-susceptible infections, 145 thousand lives could have been saved.

Bloodstream, lower respiratory, and peritoneal/intra-abdominal were the three most common sites of infection accounted for 82.2% of deaths (1.04 million). The most common site of infectious related death in China (bloodstream, 41%; lower respiratory, 29%) and globally (lower respiratory, 29%; bloodstream, 21%) were different. This may be related to the level of development, as the incidence and mortality of lower respiratory infections were significantly negatively correlated with economic level.15,16 In 2017, the global number of deaths of sepsis was 11.0 million (10.1–12.0), with low- and middle-income countries accounting for 84.8% of the total.16 Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS) Report 2021 indicated that BSIs caused by E. coli resistance to 3rd generation cephalosporins in low and middle-income countries were 3.3 times higher than that in high-income countries (58.3% vs. 17.5%); BSIs caused by methicillin-resistant S. aureus was 2.2 times (33.3% vs. 15.0%).17 The common sites of death due to drug resistance were still the bloodstream, lower respiratory, and peritoneal/intra-abdominal, whether in China, Europe,10 or globally.3 A multicenter study of 1150 ICUs (15,202 patients) worldwide showed that while respiratory infections were the leading cause of patient deaths, BSIs had higher overall mortality rates (38.1% vs. 31.9%) and ICU mortality rates (31.4% vs. 24.8%) than respiratory infections.18

Our study indicated that polymicrobial infections (147,258) were the leading cause of mortality among patients in China, with the lower respiratory tract being the primary sites of infection. Polymicrobial infections referred to the concurrent infection of two or more pathogenic microorganisms (viruses, bacteria, fungi, and parasites).19,20 A study in China involving 230,000 people from 2009 to 2019 showed that the most common co-infections in acute respiratory infections were caused by S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, M. pneumonia, and HRV.21 The patterns of co-infections vary among different age groups, with HRV-S. pneumoniae and HRV-H. influenzae, being the main co-infections in children; S. pneumoniae-M. pneumonia in school-age children; IFV-A-H. influenzae in adults, and S. pneumoniae-H. influenzae in the elderly.21 Polymicrobial infections in respiratory system infections were not only common but also fatal. Specifically, the risk of requiring mechanical ventilation was 4.14 times higher, and the risk of death was 2.35 times higher in SARS-CoV-2 co-infection with influenza virus patients.22

Staphylococcus aureus was the single bacterium causing the highest number of deaths, primarily through BSIs (75,329 deaths, Fig. 2) in China. It was also the most common microorganism causing bone and joint infections (1617 deaths, Figure S8). A meta-analysis including 536,791 patients (341 studies) showed that the estimated mortality rate of Staphylococcus aureus-related bacteraemia was 18% at 1 month, 27% at 3 months, and 30% at 1 year.23 Our study was also consisted with this conclusion, as AMR accounted for the highest proportion of Staphylococcus aureus-related deaths (107,800 deaths, Fig. 3A). Furthermore, a study involving 171,262 individuals (171 studies) in bloodstream bacterial infection with COVID-19 patients, revealed that Staphylococcus aureus was the most common pathogen in both co-infections (25%) and secondary infections (16%).24

Acinetobacter baumannii was the second leading bacterium causing monomicrobial infections in China (Fig. 2), and it was also the most lethal bacterium in bloodstream and cardiac infections (Figure S8). Over the past decade, Acinetobacter baumannii has become a challenging problem in antimicrobial therapy due to its widespread resistance to most antibiotics, especially carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB). Our data indicates that it was highly resistant to carbapenems (most prominent), third/fourth-generation cephalosporins, aminoglycosides, beta-lactamase inhibitors, and fluoroquinolones (Fig. 3A and B). The management of CRAB was difficult for several reasons. Firstly, CRAB was most isolated from respiratory specimens. Therefore, it was difficult to distinguish colonization from true infection in patients with potential host status, such as those requiring mechanical ventilation.25 Secondly, once Acinetobacter baumannii exhibited carbapenem resistance, it often develops cross-resistance to other antibiotics, such as β-lactams, fluoroquinolones, and aminoglycosides.26 Lastly, for CRAB infections, we lacked “standardized treatment” antibiotic regimen to assess the effectiveness of various therapies.25 The CHINET revealed that the resistance rate of Acinetobacter baumannii to imipenem increased rapidly from 31% in 2005 to 71.2% in 2022, and the resistance rate to meropenem rose from 39% in 2005 to 71.9% in 2022.8

Since the first reported case of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in the United States in 2001,27 carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) has rapidly spread globally.28 Data from the CHINET showed that the isolation rate of CRE increased from 2.1% in 2005 to 11.4% in 2019.8 Among them, the resistance rates of Klebsiella pneumoniae to imipenem and meropenem increased from 3.0% to 2.9% in 2005 to 25.3% and 26.8% in 2019, respectively. Escherichia coli remained relatively stable, with resistance rates to imipenem and meropenem at 1.1% and 1.4% in 2005, and 2.0% and 2.1% in 2019, respectively.8 Han et al., study revealed that the major types of CRE were KPC-2 (51.6%, 482/935), followed by NDM (35.7%, 334/935), and OXA-48-like carbapenemases (7.3%, 68/935). Among Klebsiella pneumoniae strains (64.6%, 457/709) and CRE isolates from adult patients (70.3%, 307/437), the most prevalent carbapenemase gene was KPC-2. In Escherichia coli (96.0%, 143/149) and pediatric CRE strains, the most common carbapenemase gene was NDM, accounting for 49.0% (247/498) of cases.29 Vancomycin was an important antibiotic for treating Gram-positive bacterial infections. Our results showed that the death associated with and attributable to vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus were 1143 and 328, respectively (Fig. 3A and B). The term “vancomycin resistance” here refers to treatment failure with vancomycin, including vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (VRSA), vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (VISA) and heterogeneous VISA (hVISA). Currently, there were no reports of vancomycin resistance in China, while the proportions of VISA and hVISA were 0.5% (0.1–1.0) and 10.0% (5.5–14.4), respectively.30

Our study had several inevitable limitations. Firstly, we did not differentiate between community-acquired infections and hospital-acquired infections. Almost all of the input data relies on hospital-based sampling, excluding community infections and deaths in this analysis. This may lead to an underestimation of the total number of deaths. Besides, differences in microbial species between them may have an impact on the estimates of the proportions of different microorganisms. Secondly, there were potential sources of bias, because the raw data predominantly were English. Thirdly, global antibiotic abuse has increased significantly due to COVID-19 pandemic from 2020 to 2023.31 While this would have little impact on estimates of AMR-related deaths in 2019, extrapolation of the 2019 estimates to 2020 and beyond was likely to underestimate AMR-related deaths. Fourth, this study was supported by the framework of and estimates from the GBD study and GARB study, which had their own limitations that have been discussed elsewhere.3,13 Fifth, infectious diseases and AMR might have geographical distribution heterogeneity. Unfortunately, our study did not discuss this due to data limitations. A study involving nearly 10 million participants (from 2017 to 2019) by Weng et al. showed that there were substantial geographic variations for incidence of hospitalized sepsis across China. The provinces with high incidence of sepsis were concentrated in the northwest of China, while lower in the southeast (spatial autocorrelation test based on global Moran's Index with p values all <0.05).32 Sixth, most of our results were based on the national level, which might lead to ecological fallacies (i.e., directly applying results from groups to individuals). In the future, more regional (or provincial) and detailed data were needed to ensure the robustness of the results.

Conclusion

In summary, our analyses showed that infectious diseases were a clinically significant cause of health loss, accounting for 12.1% (1.3 million) of the total deaths in China. Three mainly infectious syndromes accounted for 82.2% of deaths in 2019: BSIs, lower respiratory infections, and peritoneal and intra-abdominal infections. These five leading pathogens were S aureus, A baumannii, E coli, S pneumoniae, and E spp., which were associated with 41.2% of all infection-related deaths. In 2019, 0.6 million deaths were associated with bacterial AMR, including 0.15 million deaths attributable to bacterial AMR. The top 3 AMR attributable to death were carbapenems-resistance A baumannii, methicillin-resistance S aureus and third-generation cephalosporins-resistance E coli. Hence, the expedited initiation of an antimicrobial stewardship program was a matter of urgency.

Contributors

CZ designed this study and drafted the manuscript; CZ, XHF, and YQL participated in the creation of figures and tables; HZ and GQW provided the overall principle and direction of the study. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data sharing statement

All data used in this study can be freely accessed at the GBD 2019 (http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-2019) and Global Antimicrobial Resistance Burden study (https://vizhub.healthdata.org/microbe/).

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors thanks to Xiao Ming and Yuancun Li (lyc@jsiec.org, Joint Shantou International Eye Center of Shantou University and The Chinese University of Hong Kong) for their work in the GBD database. Their excellent sharing of GBD database analysis procedure and other public database, makes it easier for us to explore the GBD database.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanwpc.2023.100972.

Contributor Information

Hong Zhao, Email: zhaohong_pufh@bjmu.edu.cn.

Guiqiang Wang, Email: john131212@126.com, john131212@sina.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.World Health Organization Ten threats to global health. 2019. https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019 Available from:

- 2.Collaborators GAR Global mortality associated with 33 bacterial pathogens in 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2022;400(10369):2221–2248. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02185-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collaborators A.R. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2022;399(10325):629–655. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02724-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allel K., Stone J., Undurraga E.A., et al. The impact of inpatient bloodstream infections caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2023;20(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1004199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Band V.I., Hufnagel D.A., Jaggavarapu S., et al. Antibiotic combinations that exploit heteroresistance to multiple drugs effectively control infection. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4(10):1627–1635. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0480-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou J., Tian H., Du X., et al. Population-based epidemiology of sepsis in a subdistrict of beijing. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(7):1168–1176. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weng L., Zeng X.Y., Yin P., et al. Sepsis-related mortality in China: a descriptive analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44(7):1071–1080. doi: 10.1007/s00134-018-5203-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.CHINET China antimicrobial surveillance network (CHINET) http://www.chinets.com/Data/AntibioticDrugFast Available from:

- 9.Zhao H., Wei L., Li H., et al. Appropriateness of antibiotic prescriptions in ambulatory care in China: a nationwide descriptive database study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21(6):847–857. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30596-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collaborators EAR The burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in the WHO European region in 2019: a cross-country systematic analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2022;7(11):e897–e913. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(22)00225-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Magiorakos A.P., Srinivasan A., Carey R.B., et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(3):268–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Measuring infectious causes and resistance outcomes for burden estimation. 2023. https://vizhub.healthdata.org/microbe/ Available from:

- 13.Collaborators GdaI Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1204–1222. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Global burden of disease study 2019 (GBD 2019) data resources. https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/ Available from:

- 15.Estimates of the global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of lower respiratory infections in 195 countries, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(11):1191–1210. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30310-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rudd K.E., Johnson S.C., Agesa K.M., et al. Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and mortality, 1990-2017: analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 2020;395(10219):200–211. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32989-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Organization WH Global antimicrobial resistance and use surveillance system (GLASS) report 2021. 2021. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/341666/9789240027336-eng.pdf?sequence=1 Available from:

- 18.Vincent J.L., Sakr Y., Singer M., et al. Prevalence and outcomes of infection among patients in intensive care units in 2017. JAMA. 2020;323(15):1478–1487. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stacy A., McNally L., Darch S.E., Brown S.P., Whiteley M. The biogeography of polymicrobial infection. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2016;14(2):93–105. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2015.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brogden K.A., Guthmiller J.M., Taylor C.E. Human polymicrobial infections. Lancet. 2005;365(9455):253–255. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17745-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Z.J., Zhang H.Y., Ren L.L., et al. Etiological and epidemiological features of acute respiratory infections in China. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):5026. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-25120-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swets M.C., Russell C.D., Harrison E.M., et al. SARS-CoV-2 co-infection with influenza viruses, respiratory syncytial virus, or adenoviruses. Lancet. 2022;399(10334):1463–1464. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00383-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bai A.D., Lo C.K.L., Komorowski A.S., et al. Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022;28(8):1076–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2022.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Langford B.J., So M., Leung V., et al. Predictors and microbiology of respiratory and bloodstream bacterial infection in patients with COVID-19: living rapid review update and meta-regression. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022;28(4):491–501. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tamma P.D., Aitken S.L., Bonomo R.A., Mathers A.J., van Duin D., Clancy C.J. Infectious diseases society of America guidance on the treatment of AmpC β-lactamase-producing enterobacterales, carbapenem-resistant acinetobacter baumannii, and stenotrophomonas maltophilia infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;74(12):2089–2114. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun K., Pan L., Jin F.G. Advances in the treatment of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii pneumonia (in Chinese) Zhonghua Jiehe He Huxi Zazhi. 2021;44(6):582–587. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112147-20201013-01034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yigit H., Queenan A.M., Anderson G.J., et al. Novel carbapenem-hydrolyzing beta-lactamase, KPC-1, from a carbapenem-resistant strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45(4):1151–1161. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.4.1151-1161.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zeng M., Xia J., Zong Z., et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control of infections caused by carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacilli. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2023;56(4):653–671. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2023.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han R., Shi Q., Wu S., et al. Dissemination of carbapenemases (KPC, NDM, OXA-48, IMP, and VIM) among carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolated from adult and children patients in China. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10:314. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shariati A., Dadashi M., Moghadam M.T., van Belkum A., Yaslianifard S., Darban-Sarokhalil D. Global prevalence and distribution of vancomycin resistant, vancomycin intermediate and heterogeneously vancomycin intermediate Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):12689. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-69058-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Russell C.D., Fairfield C.J., Drake T.M., et al. Co-infections, secondary infections, and antimicrobial use in patients hospitalised with COVID-19 during the first pandemic wave from the ISARIC WHO CCP-UK study: a multicentre, prospective cohort study. Lancet Microbe. 2021;2(8):e354–e365. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(21)00090-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weng L., Xu Y., Yin P., et al. National incidence and mortality of hospitalized sepsis in China. Crit Care. 2023;27(1):84. doi: 10.1186/s13054-023-04385-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.