Summary

Background

Characterizing prediabetes phenotypes may be useful in guiding diabetes prevention efforts; however, heterogeneous criteria to define prediabetes have led to inconsistent prevalence estimates, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. Here, we estimated trends in prediabetes prevalence in Mexico across different prediabetes definitions and their association with prevalent cardiometabolic conditions.

Methods

We conducted a serial cross-sectional analysis of National Health and Nutrition Surveys in Mexico (2016–2022), totalling 22 081 Mexican adults. After excluding individuals with diagnosed or undiagnosed diabetes, we defined prediabetes using ADA (impaired fasting glucose [IFG] 100–125 mg/dL and/or HbA1c 5.7–6.4%), WHO (IFG 110–125 mg/dL), and IEC criteria (HbA1c 6.0–6.4%). Prevalence trends of prediabetes over time were evaluated using weighted Poisson regression and its association with prevalent cardiometabolic conditions with weighted logistic regression.

Findings

The prevalence of prediabetes (either IFG or high HbA1c [ADA]) in Mexico was 20.9% in 2022. Despite an overall downward trend in prediabetes (RR 0.973, 95% CI 0.957–0.988), this was primarily driven by decreases in prediabetes by ADA-IFG (RR 0.898, 95% CI 0.880–0.917) and WHO-IFG criteria (RR 0.919, 95% CI 0.886–0.953), while prediabetes by ADA-HbA1c (RR 1.055, 95% CI 1.033–1.077) and IEC-HbA1C criteria (RR 1.085, 95% CI 1.045–1.126) increased over time. Prediabetes prevalence increased over time in adults >40 years, with central obesity, self-identified as indigenous or living in urban areas. For all definitions, prediabetes was associated with an increased risk of cardiometabolic conditions.

Interpretation

Prediabetes rates in Mexico from 2016 to 2022 varied based on defining criteria but consistently increased for HbA1c-based definitions and high-risk subgroups.

Funding

This research was supported by Instituto Nacional de Geriatría in Mexico. JAS was supported by NIH/NIDDK Grant# K23DK135798.

Keywords: Prediabetes, Glucose metabolism, Insulin resistance, Cardiometabolic risk

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Understanding risk factors for progression to diabetes is pivotal to guide prevention efforts in high-risk settings. However, describing the epidemiology of prediabetes, one of the most well-known risk factors for diabetes, has proved challenging in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), including Mexico. Prediabetes has at least five distinct definitions, which have led to inconsistent prevalence estimates and have made comparisons across time and populations complicated. We conducted a PubMed database search without language restriction for studies evaluating the prevalence of prediabetes in Mexico published between September 1, 2017, and September 1, 2023. The search terms were “prediabetes” AND “prevalence” AND “Mexico”. We identified a number of studies on the topic, most of which were conducted in specific regions or health centres in Mexico and only two studies estimating prevalence with nationally representative data, one using data from the Mexican Health and Aging Study from 2016 and one from the National Health and Nutrition Survey in 2022. No study to date has evaluated the changes over time in prediabetes phenotypes using varied definitions or evaluated factors which modified its prevalence.

Added value of this study

This study adds to the existing literature by providing new insights into the prevalence of prediabetes phenotypes using different prediabetes definitions and their determinants and changes over time during the 2016–2022 period. For this, we leveraged nationally representative cross-sectional data from the Mexican adult population for the evaluated period. Our study shed light on the heterogeneity of prediabetes definitions and their impact on prevalence estimates of prediabetes over time. Notably, HbA1c-based definitions showed an increasing prevalence trend over time, but with an overall decrease in impaired fasting glucose phenotypes. Furthermore, we identified subgroups with increasing trends of prediabetes prevalence, such as adults ≥40 years, individuals with central obesity, indigenous populations, and individuals living in urban settings. Notably, heterogeneity in prediabetes criteria often leads to inconsistent evaluations of prediabetes prevalence, which may complicate screening and effective preventive policies. Regardless of defining criteria, prediabetes was consistently associated with prevalent cardiometabolic conditions in Mexico, indicating that it represents a risk group which clusters individuals at higher cardio-metabolic risk.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our findings underscore the significance of early identification and preventive measures for individuals with prediabetes in Mexico, especially among high-risk subgroups. Our observations of heterogeneous trends of prediabetes prevalence according to different definitions emphasize the necessity for further research to understand prediabetes in underserved settings. This also highlights the urge to harmonize the definition of prediabetes to facilitate screening and improve reproducibility in studies focused on the epidemiology prediabetes, considering that the prevalence of this condition will likely increase in the coming years in LMICs, including Mexico.

Introduction

Prediabetes is a stage of altered glucose metabolism associated with risk of progression to diabetes mellitus and an elevated burden of cardiovascular risk factors.1,2 While comprehensive data on the global burden of prediabetes are lacking, the International Diabetes Federation estimates a global prevalence of Impaired Glucose Tolerance (IGT) of 7.5% (374 million adults), of whom 72.2% reside in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).3 Ethnicity is a known modifier of metabolic risk in individuals with prediabetes,4,5 in particular, Mexican mestizo populations have an increased risk of diabetes, which manifests at younger ages and lower body-mass index levels.6, 7, 8 However, epidemiological data on prediabetes among ethnically diverse populations are limited, including in Mexico, where diabetes mellitus is a leading cause of disability and death.9 Given that prediabetes is the earliest identifiable stage of glucose dysregulation and progression to diabetes mellitus can be prevented at this stage,2,10,11 a more nuanced understanding of prediabetes epidemiology in Mexico could help inform diabetes prevention efforts.2 Despite being a potentially reversible risk factor for diabetes, an important challenge in the timely identification of prediabetes in clinical and public health contexts lies in the heterogeneity and controversy of its definition.2,12,13 Five definitions of prediabetes have been proposed by professional societies and are in current practice14, 15, 16: The American Diabetes Association (ADA) defines prediabetes as either fasting plasma glucose (FPG, 100–125 mg/dL), glycated haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c, 5.7–6.4%), or 2-h post 75-g oral glucose load (140–199 mg/dL).16 The World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Expert Committee (IEC) proposed definitions that also include 2-h post 75-g oral glucose load or FPG (WHO) or HbA1c-only (IEC), but with distinct cut-offs.14,15 These discrepancies have led to heterogeneous estimates of prediabetes prevalence and conflicting data on the utility of its identification.2,13,17 In this study, we aimed to provide reliable estimates on prevalence trends of prediabetes in Mexican adults from 2016 to 2022 using a series of nationally representative surveys and to assess potential modifiers of prediabetes prevalence. Finally, we also quantified the extent to which prediabetes is associated with prevalent cardiometabolic comorbidities.

Methods

Study design

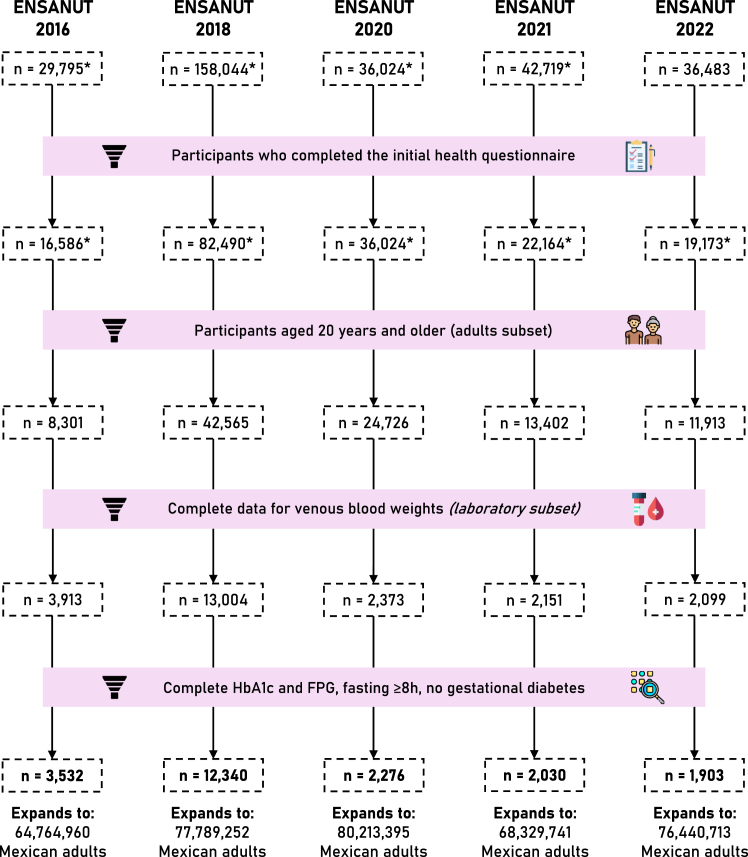

We conducted a serial cross-sectional analysis using data from the Mexican National Health and Nutrition Survey (ENSANUT) for the years 2016, 2018, 2020, 2021, and 2022.18, 19, 20, 21, 22 Briefly, ENSANUT is a population-based survey that aims to assess the health and nutritional status of Mexican adults. ENSANUT is representative at a national, regional, and rural/urban level, as it uses two-stage probabilistic cluster stratified sampling based on households and individuals, such that the sample size expands to the size of the population it represents; this expansion factor is calculated according to household (state, municipality, and rural/urban area) and individual (age group) characteristics of each participant. Sample weights are further corrected using the expected response rate (obtained from the response rate observed the previous year) and calibrated using a post-stratification correction factor to account for over- or underrepresentation of specific subgroups.23 Participants underwent a comprehensive questionnaire collecting demographic, socioeconomic, and health-related data and a physical exam including measurement of blood pressure and anthropometry. A random subsample of each cycle had an additional biochemical evaluation with serum samples for fasting glucose, insulin, lipid profile, and glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c); these biomarkers were used to estimate the prevalence of glucose metabolism disturbances. For this study, ENSANUT 2006 and 2012 were not included because of insufficient biomarkers to perform adequate classification of alterations in glucose metabolism. Details on the study design and a complete flowchart for the selection of participants are outlined in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of participant selection for each year of the survey. We show the total number of participants surveyed per year, followed by the number of them who completed the health questionnaire. The general population is comprised of subjects ≥20 years old, and the laboratory subset includes those with complete venous blood weights. Lastly, to obtain national estimates of diabetes and prediabetes prevalence we removed individuals with missing A1c/FPG data, with fasting <8 h, or with gestational diabetes. This diagram was designed using resources created by Freepik from www.flaticon.com.

Variable definitions

Diagnosed and undiagnosed diabetes

Previously diagnosed diabetes was defined by self-report among individuals who answered “yes” to the question “Has a doctor ever told you that you have diabetes (or high blood sugar)?” or a report of using insulin or oral diabetes medications. Individuals who did not meet the criteria for prior diagnosis, but who had either fasting plasma glucose (FPG) ≥126 mg/dL or hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) ≥6.5% were categorized as having undiagnosed diabetes. The prevalence of diabetes according to these definitions was estimated using individual-level data from all ENSANUT cycles.

Prediabetes and insulin resistance

We defined prediabetes using two different biomarker-based definitions. Impaired fasting glucose (IFG) was defined using fasting plasma glucose levels between 100 and 125 mg/dL and high HbA1c was defined using HbA1c levels between 5.7–6.4%, as proposed by the ADA.16 To further evaluate concordance and discordance of these criteria, we defined variables for individuals with IFG but HbA1c within the normal range (IFG-Normal A1c), individuals with elevated HbA1c but normal fasting glucose (NFG-High A1c), and individuals who fulfilled both criteria (IFG- High A1c). Finally, we sought to study the impact of higher diagnostic thresholds by using the prediabetes definitions proposed by the WHO (FPG 110–125 mg/dL) and IEC (HbA1c 6.0–6.4%).14,15 For all these definitions, we excluded individuals with previously diagnosed or undiagnosed diabetes mellitus. Furthermore, we defined insulin resistance (IR) as HOMA2-IR values ≥ 2.5, as previously defined for the Mexican population.24,25 Prediabetes definitions used for this study are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Prediabetes as defined by the ADA, WHO and IEC using various diagnostic tests.

| Criteria | Association | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| IFG (Using fasting plasma glucose) | ADA | 100–125 mg/dL |

| WHO | 110–125 mg/dL | |

| High HbA1c | ADA | 5.7–6.4% |

| IEC | 6.0–6.4% | |

| IGT (Using 2-h glucose in OGTT) | ADA | 140–199 mg/dL |

| WHO | Not available for this study | |

| Any ADA criteria | Either IFG or high HbA1c Definition used in this study unless stated otherwise |

|

| Both ADA criteria | Both IFG and high HbA1c | |

The default definition used throughout this study—unless stated otherwise—is having either IFG or high HbA1c as defined by the ADA. Abbreviations. ADA: American Diabetes Association. WHO: World Health Organization. IEC: International Expert Committee. IFG: Impaired fasting glucose. IGT: Impaired glucose tolerance. OGTT: Oral glucose tolerance test.

Covariates

We used body mass index (BMI) to categorize participants with normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (≥25 kg/m2) or obesity (≥30 kg/m2), and waist circumference ≥90 cm for men or ≥80 cm for women to define central obesity based on IDF criteria.26 Family history of diabetes was defined in individuals who responded “yes” to the question “Has your relative been previously diagnosed with diabetes (or high blood sugar)?” for either the mother, father, or siblings of the participant (siblings were not assessed in 2016). Participants who responded “yes” to the question “Do you speak an indigenous language?” were considered to have an indigenous identity. To assess state-level social disadvantage we used the 2020 density-independent social lag index (DISLI) by obtaining the residuals from a linear regression of population density onto social lag index, which is a composite measure of access to education, health care, dwelling quality, and basic services in Mexico.27, 28, 29

Cardiometabolic conditions

Hypertension was defined by either a self-reported prior diagnosis, use of blood pressure-lowering medications, a systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg, or a diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg (using the mean of at least two different measurements). Hypercholesterolemia was defined by fasting total cholesterol ≥200 mg/dL or the use of cholesterol-lowering drugs (statins or ezetimibe), and hypertriglyceridemia was defined as fasting triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL or the use of triglyceride-lowering drugs (fibrates). Additionally, C-reactive protein was measured for the years 2021 and 2022, where we defined high CRP (as a surrogate of low-grade inflammation) as having a value equal to or greater than the 80th percentile, which we found to be 0.55 mg/L. The IDF defines metabolic syndrome as having obesity (by either BMI or waist circumference) plus two of the following: triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL (or specific treatment for this condition), HDL-cholesterol <40 mg/dL for men or <50 mg/dL for women (or specific treatment), arterial blood pressure ≥130/85 mmHg (or specific treatment), FPG ≥100 mg/dL or prior diagnosis of type 2 diabetes.26 In this study, we modified this definition to exclude FPG ≥100 or T2D from the criteria to avoid overestimation of the association with prediabetes. Cardiovascular disease was defined as a self-reported prior diagnosis of either myocardial infarction, heart failure or stroke.

Statistical analyses

Weighted prevalence of prediabetes and its modifying factors

The prevalence of prediabetes and insulin resistance was estimated using sample weights from ENSANUT for participants with available HbA1c/IFG measures; all estimations were conducted using the survey R package.30 We further performed weighted subgroup analyses for prevalence trends stratified by age category (20–39, 40–59 or ≥60 years old), sex, BMI category, central obesity, family history of diabetes, indigenous identity, living in a rural or urban area, and DISLI category (high or low/middle). To assess trends in prediabetes prevalence, we implemented weighted Poisson models with an interaction term between ENSANUT year and each modifying factor. We estimated the population at risk by subtracting the total population with diabetes (using survey package) from the National Population Council (CONAPO) estimates of total population31 (total population–population with diabetes), which we included as an offset to model annual rates of prediabetes and obtain prevalence rate ratios (RR). Missing data was not imputed and was excluded under the assumption of data missing completely at random; a full report of data missingness patterns is reported in Supplementary Materials.

Prediabetes as a predictor of cardiometabolic conditions

To assess whether participants with prediabetes (using the ADA, WHO and IEC definitions) showed an association with prevalent cardiometabolic conditions compared to euglycemic individuals, we fitted weighted mixed logistic regression models adjusting for age, sex, and BMI, and with each ENSANUT cycle as a clustering effect. The outcomes for these models were arterial hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia, insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease. We did not exclude participants with diabetes to compare the risk conferred by this condition with that of prediabetes. All statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.1.2 and p-value thresholds are estimated for a two-sided significance level of α = 0.05.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This project was registered and approved by the Research and Ethics Committee at Instituto Nacional de Geriatría, project number DI-PI-006/2020.

Role of the funding source

This research was supported by Instituto Nacional de Geriatría in Mexico. JAS was supported by NIH/NIDDK Grant# K23DK135798. The funding bodies had no involvement in study design; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of data or the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Study population

We included adults aged 20 years or older who completed the health questionnaire, totalling 100,907 participants (2016: 8301, 2018: 42,565, 2020: 24,726, 2021: 13,402, 2022: 11,913). Among them, 23,540 provided a venous blood sample (2016: 3913, 2018: 13,004, 2020: 2373, 2021: 2151, 2022: 2099). After excluding participants with missing data for HbA1c or FPG, with less than 8 h of fasting, or with gestational diabetes, we obtained a final sample of 3532 for 2016, 12,340 for 2018, 2276 for 2020, 2030 for 2021, and 1903 for 2022, which expanded to 64,764,960, 77,789,252, 80,213,395, 68,329,741, and 76,440,713 Mexican adults after weighting, respectively. A flowchart diagram of participant selection is available in Fig. 1. We observed a consistent predominance of women (57.8%) and an overall median age of 44 years (32–57 years). The proportion of participants with indigenous identity ranged from 4.7% (626/13,402 in 2021) to 12% (964/8301 in 2016) and those living in urban areas ranged from 50% (4155/8301 in 2016) to 79% (19,606/24,726 in 2020). A complete outline of population characteristics is shown in Supplementary Table S1. The final analytic sample was obtained by randomly sampling the original sample of adults ≥20 years. A comparison of the two populations and the percentages of missing values for each variable are shown in Supplementary Table S2. The only characteristics with substantial differences between these populations were indigenous language, urban area, and presence of hypertension.

Trends in the prevalence of glucose metabolism disturbances in Mexico

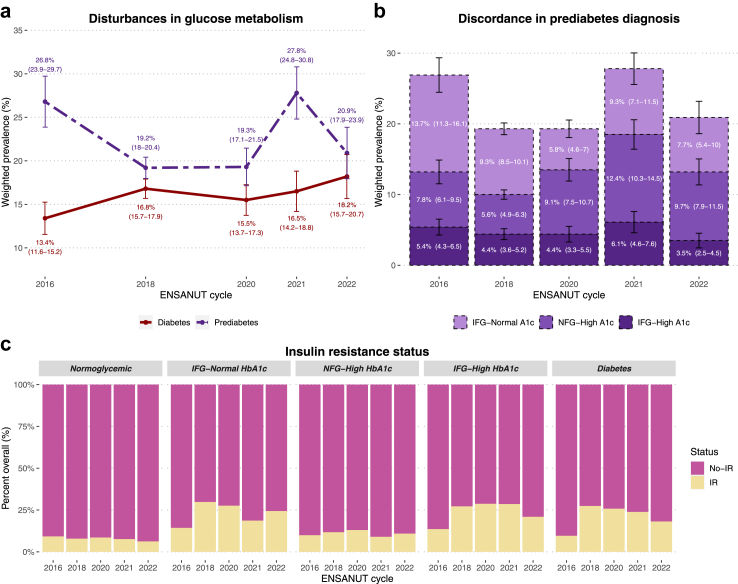

The prevalence of prediabetes by any definition was higher than that of diabetes in Mexico for all years. However, the pattern we observed was irregular, with a steep decrease from 2016 to 2018, followed by a marked increase from 2020 to 2021; finally, we observed a prevalence of 20.9% (95% CI 17.9–23.9) in 2022 (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Table S3). Poisson models showed an overall decline in prediabetes prevalence per year (RR 0.973, 95% CI 0.957–0.988); however, we observed discrepant trends depending on the definition, with an increase using ADA-HbA1c criteria (RR 1.055, 95% CI 1.033–1.077) and a decrease using ADA-IFG criteria (RR 0.898, 95% CI 0.880–0.917). A similar overall trend was observed for the stricter IEC-HbA1c (RR 1.085, 95% CI 1.045–1.126) and WHO-IFG criteria (RR 0.919, 95% CI 0.886–0.953), indicating that the overall decreasing trend for prediabetes using any criteria was driven by decreases in IFG which offset increases in high HbA1c. Poisson models were tested for overdispersion, which was non-significant in all models.

Fig. 2.

Change in prevalence of diabetes and prediabetes from 2016 to 2022 in Mexico (a). Participants with prediabetes (either high HbA1c or IFG) are categorized according to the diagnostic criteria they fulfilled (IFG only, high HbA1c only, or both), revealing that changes in prevalence were primarily driven by subjects with high HbA1c (b). The percentage of participants with insulin resistance (HOMA-2IR ≥ 2.5) in each category is also shown (c). Abbreviations. IFG: Impaired fasting glucose. NFG: Normal fasting glucose. IR: Insulin resistance.

To further characterize this phenomenon, we classified individuals with prediabetes into those who had both high HbA1c and IFG and those who displayed only one of these alterations (Fig. 2b). Among participants with discordance in these criteria, we observed an increase in the proportion of high HbA1c and a decline in IFG over the years, with an increase in individuals with concordant IFG-high HbA1c, likely indicating increases in sustained alterations in glucose metabolism (Fig. 2b). Furthermore, individuals with prediabetes with alterations in both parameters had the highest proportions of insulin resistance (IR), comparable to the IR levels of subjects with diabetes (Fig. 2c).

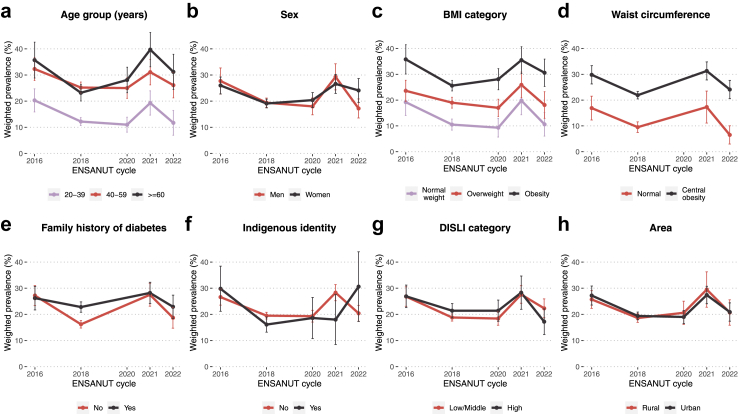

Determinants of prediabetes prevalence in Mexico

Several factors were significantly associated with prediabetes prevalence such as older age, BMI ≥25 and ≥30 kg/m2, central obesity, and a family history of diabetes. Although the overall trend was a decrease, some groups displayed an increment in prediabetes prevalence over the years, namely participants ≥40 years, those with obesity, and those with a family history of diabetes (Fig. 3, Table 2). When assessing only high HbA1c as the diagnostic criteria for prediabetes, we found that indigenous identity was an additional risk factor (Supplementary Figure S2, Supplementary Tables S4 and S5). Lastly, to address potential explanations for the observed differences in prediabetes prevalence related to ethnic background, we contrasted rates of insulin resistance and various demographic and health-related parameters between participants with and without indigenous identity. Although we observed lower rates of insulin resistance among indigenous individuals, this population displayed higher age, DISLI, HbA1c and triglycerides, but lower HOMA2-IR, HOMA2-β (indicating lower β-cell function), BMI and waist circumference (Supplementary Figure S3).

Fig. 3.

Change in prevalence of prediabetes (either high HbA1c or IFG) from 2016 to 2022 in Mexico stratified by age group (a), sex (b), BMI category (c), waist circumference (d), family history of diabetes (e), indigenous identity (f), DISLI category (g) and area (h). Abbreviations. BMI: Body mass index. DISLI: Density-independent social lag index. IFG: Impaired fasting glucose.

Table 2.

Prevalence rate ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals from mixed-effects poisson models to quantify the influence of modifiers on prediabetes rates over time (either high HbA1c or IFG).

| Model | Predictor | RR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 20–39 | Ref |

| 40–59 | 2.080 (1.855–2.334) | |

| ≥60 | 2.164 (1.901–2.465) | |

| ENSANUT year | 0.920 (0.890–0.950) | |

| Year∗Age 40–59 | 1.051 (1.010–1.094) | |

| Year∗Age ≥60 | 1.104 (1.057–1.154) | |

| Sex | Men | Ref |

| Women | 1.017 (0.923–1.121) | |

| ENSANUT year | 0.970 (0.946–0.996) | |

| Year∗Women | 1.005 (0.973–1.038) | |

| BMI categories | Normal weight | Ref |

| Overweight | 1.573 (1.358–1.822) | |

| Obesity | 2.228 (1.934–2.567) | |

| ENSANUT year | 0.930 (0.890–0.973) | |

| Year∗Overweight | 1.030 (0.977–1.085) | |

| Year∗Obesity | 1.053 (1.002–1.107) | |

| Waist circumference | Normal | Ref |

| Central obesity | 1.814 (1.558–2.112) | |

| ENSANUT year | 0.890 (0.839–0.943) | |

| Year∗Obesity | 1.106 (1.041–1.176) | |

| Family history of diabetes | No | Ref |

| Yes | 1.169 (1.063–1.286) | |

| ENSANUT year | 0.946 (0.924–0.969) | |

| Year∗Yes | 1.058 (1.024–1.094) | |

| Indigenous language | No | Ref |

| Yes | 1.069 (0.916–1.247) | |

| ENSANUT year | 0.976 (0.960–0.992) | |

| Year∗Yes | 0.976 (0.918–1.037) | |

| DISLI | Low-Middle | Ref |

| High | 1.087 (0.981–1.204) | |

| ENSANUT year | 0.980 (0.962–0.998) | |

| Year∗High | 0.979 (0.944–1.015) | |

| Area | Rural | Ref |

| Urban | 1.036 (0.942–1.140) | |

| ENSANUT year | 0.965 (0.939–0.991) | |

| Year∗Urban | 1.010 (0.976–1.044) |

Abbreviations. BMI: Body mass index. DISLI: Density-independent social lag index.

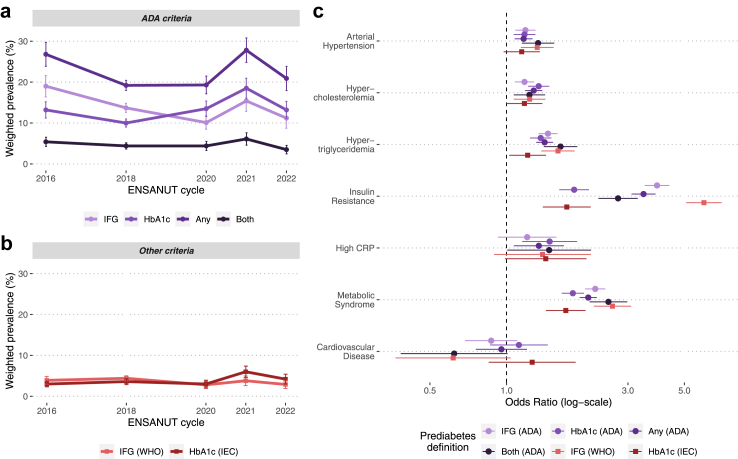

Prediabetes as a predictor of cardiometabolic conditions

We estimated the prevalent cardiometabolic risk (age, sex and BMI-adjusted) associated with different prediabetes definitions, which displayed substantial variability in prevalence (Fig. 4a and b). First, we observed that IFG—but not high HbA1c—was associated with prevalent arterial hypertension. Moreover, almost all prediabetes definitions displayed roughly comparable estimates for prevalent hypercholesterolemia and hypertriglyceridemia, except for the definition suggested by the IEC, which was poorly associated with these conditions. For insulin resistance, the strongest association was observed with the IFG-WHO definition and the weakest association with the high HbA1c-IEC definition. We also found ADA definitions to be associated with low-grade inflammation (CRP ≥0.55 mg/L defined by the 80th percentile). Prediabetes was also associated with metabolic syndrome, and individuals with alterations in both ADA criteria had a higher likelihood of having this condition. Lastly, we found no association with a history of cardiovascular disease for any of the definitions of prediabetes (Fig. 4c). All odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals are specified in Supplementary Table S5, where we also include the association of each outcome with diabetes mellitus.

Fig. 4.

Prevalence of prediabetes in Mexico from 2016 to 2022 according to different definitions used by the ADA (a) and by other organizations (b). We also present an odds ratio plot displaying the association between each of these definitions with multiple cardiovascular outcomes, adjusted for age, sex, and body mass index. Abbreviations. ADA: American Diabetes Association. CRP: C-Reactive Protein. IEC: International Expert Committee. WHO: World Health Organization. IFG: Impaired fasting glucose.

Discussion

In this serial cross-sectional study of nationally representative surveys spanning 2016–2022, totalling 22,079 Mexican adults, we found that prediabetes by any definition currently affects 20.9% (95% CI 17.9–23.9) of the adult population. While the prevalence of prediabetes has decreased over time overall, largely driven by a decrease in IFG using both ADA and WHO criteria, we observed a consistent increase in prevalence when using HbA1c. As expected, we observed a consistent increase in prediabetes prevalence among adults over 40 years, individuals with obesity and individuals who had a family history of diabetes. Finally, clustering of cardio-metabolic conditions varied widely using different prediabetes definitions, which highlights the need for a consensus to better characterize prediabetes-associated cardiometabolic burden.

Prevalence of prediabetes

Providing a precise estimate of prediabetes prevalence has been challenging, as estimates widely vary according to definition and study settings. In 2019, the IDF estimated that 7.5% of adults worldwide had IGT, with the highest prevalence (13.8%) observed in North America and the Caribbean.3 Compared to what we observed here for the Mexican population prevalence of prediabetes in the U.S. was estimated to be higher, with 43% using the ADA-IFG definition, 15.4% with WHO-IFG, 12.3% with ADA-HbA1c, and 4.3% with IEC-HbA1c, using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from 2015–2016.2 A report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) using data from NHANES 2017–202032 showed that the prevalence of prediabetes was also higher than those observed in our study, with 38% using either high HbA1c or IFG (ADA-Any) and 10.8% using both. These discrepancies could be attributed to differences in study design, sampling, and analysis (e.g., some studies used participants aged ≥18 years and provided an age-adjusted prevalence) or due to ethnic differences, which need further exploration. Regarding the Mexican population, a recent study by Gallardo-Rincón and colleagues33 described the disease profile of 743,000 Mexican adults ≥20 years using a digital screening platform, and they observed a prediabetes prevalence of 13.4% (using the ADA-IFG definition) during the 2014–2018 period, which was similar to the rates for ADA-IFG observed in our study. Notably, we did not find a consistent increase in the overall prevalence of prediabetes; however, we observed an increase using the ADA-HbA1c and IEC-HbA1c definitions and an increase in the prevalence of concordant IFG and high HbA1c over time. Indeed, reports from different regions of the world suggest that the prevalence of prediabetes has increased over the last few decades regardless of the definition; a trend projected to continue.2,3

Factors associated with increased prediabetes prevalence

We also found that participants of older age, with obesity, and with a family history of diabetes are more likely to have prediabetes than other populations. This finding is consistent with previous studies that report a strong association of age and obesity with prediabetes.2 Moreover, a similar report from ENSANUT focusing on diabetes also found urban area and limited access to education to significantly increase its prevalence,34 outlining the impact of sociodemographic and structural factors in the development of glucose metabolism disturbances. Interestingly, we found that Indigenous participants have lower rates of obesity and insulin resistance, which aligns with an earlier study reporting a reduced prevalence of prediabetes and diabetes (defined only with FPG and OGTT) in the Indigenous Mexican population.35 Nonetheless, in our study, Indigenous participants had an elevated prevalence of high HbA1c, were older, had higher triglycerides, and had lower HDL cholesterol. Indigenous participants also showed lower values of HOMA2-IR and HOMA2- β, which could indicate a certain degree of insulin deficiency rather than insulin resistance in this population. This could indicate that results are not only explained by socioeconomic factors but probably also by inherent differences in the pathophysiology of glucose metabolism disturbances in the Indigenous population, possibly driven by genetic ancestry. These results also give rise to the idea that specific populations (allegedly due to ethnic and racial differences) are at higher risk of specific diabetes phenotypes,36, 37, 38 which should be further explored in future studies. Two caveats should be considered when interpreting these results: 1) the definition of indigenous identity in our study is based on self-report of speaking an indigenous language, which may exclude individuals with indigenous ancestry who are Spanish speakers, and 2) we also acknowledge that ENSANUT is not specifically designed to be representative of the indigenous population and that the sample of individuals who report speaking an indigenous language is rather small. This calls for further studies designed to be representative of this subset of the population and which consider more robust measures of indigenous identity, including self-recognized indigenous identity or ancestry data.

Cardiometabolic risk conferred by prediabetes

We also evaluated the risk conferred by prediabetes diagnosis by the different definitions and observed that WHO-IFG and the combination of both ADA criteria were associated with the highest cardio-metabolic risk. Notably, IEC-HbA1c displayed the weakest associations, and no definition was associated with cardiovascular disease. Previously, Tabák and colleagues39 delineated a timeline of the events that tie initial glycemic dysregulation to the onset of diabetes, in which there is a prolonged period of impaired insulin sensitivity and secretion, even before the biochemical criteria for prediabetes is met.39 Thus, subjects diagnosed with prediabetes are likely to already present with insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction, which is why some authors have suggested changes in the diagnostic approach of high-risk subjects to detect earlier disturbances in glucose homeostasis (e.g., replace 2-h glucose with 1-h glucose in OGTT).40 During this prediabetic period, insulin resistance interacts with other risk factors, such as visceral obesity, to precipitate an unfavourable metabolic state characterized by a decline in β-cell mass and function, increased lipolysis, changes in adipokine profiles, systemic inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction, among others.39,41,42 The intersection of these variables is reflected by the association of prediabetes with dyslipidemia, hypertension, low-grade inflammation, and metabolic syndrome in our results. Eventually, a subset of these individuals may progress to overt diabetes—which further accelerates these mechanisms—and may ultimately develop micro and macrovascular complications.39 Conversely, a significant number of individuals with prediabetes may never develop diabetes at all, or even revert to normoglycemia,39 which is often influenced by lifestyle or pharmacological interventions.2 Of note, a recent study by Rooney and colleagues found that older adults with prediabetes display low rates of progression to diabetes and high rates of regression to normoglycemia,43 which may generate debate on the utility of the diagnosis of prediabetes in older subjects for risk stratification. Nonetheless, several meta-analyses using data from prospective studies have shown that all prediabetes definitions increase the risk of incident diabetes,44,45 cardiovascular disease, and mortality,46 with WHO-IFG and HbA1c-based definitions showcasing the highest risk in most cases. Many authors consider prediabetes and diabetes as a continuum of glucose metabolism disturbances, which is supported by transitions from prediabetes to both diabetes and normoglycemia,13 and, as such, the changes in prevalence of diabetes and prediabetes may be inversely associated. However, we did not observe a significant increase or decrease in the prevalence of total diabetes (diagnosed and undiagnosed) from 2016 to 2020 (RR: 1.010 [95% CI: 0.992–1.029]); this was also previously explored by Basto-Abreu and colleagues, with similar results.34 This discrepancy may be in part accounted for by the relatively small number of points in time studied, however, it is important to note that the risk of developing diabetes or reverting to normoglycemia varies greatly from person to person and cannot be properly assessed in cross-sectional population studies.

In this study, we found no association between prediabetes and cardiovascular disease, however, the cross-sectional design of our study cannot capture the long-term effects of these conditions. Furthermore, this discordance in prevalence and conferred risk driven by different definitions can also be attributed to the inherent properties of each diagnostic test and threshold. For instance, high HbA1c has shown high specificity for the diagnosis of prediabetes and is likely to identify individuals who also meet the other two criteria.2 However, this lowers its utility for screening in the general population, which is why the WHO does not recommend using HbA1c for diagnosis of prediabetes.14 In this regard, IFG is highly sensitive, but there is skepticism about the use of lower cut-offs (i.e., 100–125 mg/dL), as this increases the risk of false positives and possibly captures individuals with lower cardiometabolic risk. Preferably, various diagnostic tests should be used to tailor prevention and therapeutic strategies. For the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus, the ADA recommends using two different tests and not relying on isolated elevations of a single measurement,16 and it has been questioned whether this recommendation should be extended to prediabetes; our results show that combining multiple criteria (ADA-both) does improve the association with metabolic disease while reducing the proportion of detected individuals.

Strengths and limitations

This study is, to our knowledge, the first to estimate the prevalence of prediabetes in the Mexican population by different definitions using precise and nationally representative data spanning multiple years. Given the large burden of diabetes and metabolic diseases in the Mexican population, our estimates are likely to provide useful information for policymakers regarding screening strategies for prediabetes and to identify populations with higher prediabetes prevalence. However, we also acknowledge some limitations which should be considered to adequately interpret our results. First, crucial data was not available in ENSANUT, such as the use of specific medications (e.g., metformin, GLP-1R agonists, SGLT2 inhibitors, etc.), and oral glucose tolerance test (prevalence of prediabetes may be underestimated as a result). Second, the number of cross-sectional points over time are not enough to use time series analysis, which would allow us to explore non-linear trends in prediabetes prevalence. Third, for cardiovascular disease, we only used self-reported data, which may underestimate the prevalence of this condition, as well as its association with prediabetes. Lastly, while probabilistic surveys are essential to provide reliable estimates at a national level, the cross-sectional setting of this study hinders the assessment of long-term pathophysiological changes, and further studies are needed to evaluate the risk of incident diabetes, cardiometabolic disease, and cause-specific mortality in individuals living with prediabetes.

Conclusion

In summary, we observed a high prevalence of prediabetes in the Mexican population which varied widely according to the diagnostic test and cut-off being used. Overall, the prevalence of IFG decreased over time, with increases observed in prediabetes as defined by HbA1c criteria. Nevertheless, our results emphasize the importance of early detection and prevention of alterations in glucose metabolism (particularly in populations at high risk), as prediabetes is associated with an increased risk of poor cardiometabolic outcomes regardless of the definition. This also highlights the urge to conduct more research and harmonize the definition of prediabetes, considering that the prevalence of this condition will likely increase in the coming years in LMICs.

Contributors

Research idea and study design: CDPC, CAFM, OYBC; data acquisition and processing: RR, CAFM, CDPC, NEAV, AVV, LFC, DRG; statistical analysis: CAFM, CDPC, OYBC; analysis/interpretation: CAFM, CDPC, OYBC, NEAV, AVV, LFC, DRG; manuscript drafting: JPE, MRBA, PSC, ANL, KCH, LCQ, CDPC, CAFM, JAS, OYBC; supervision or mentorship: JAS, OYBC. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. CAFM, CDPC had OYBC had full access to the data and verified it prior to and after statistical analyses.

Data sharing statement

All code, datasets and materials are available for reproducibility of results at http://github.com/oyaxbell/prediabetes_ensanut/.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

CAFM and JPE are enrolled at the PECEM Program of the Faculty of Medicine at UNAM. CAFM and DRG are supported by CONACyT.

Funding: This research was supported by Instituto Nacional de Geriatría in Mexico. JAS was supported by NIH/NIDDK Grant# K23DK135798.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lana.2023.100640.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Rett K., Gottwald-Hostalek U. Understanding prediabetes: definition, prevalence, burden and treatment options for an emerging disease. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35:1529–1534. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2019.1601455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Echouffo-Tcheugui J.B., Selvin E. Prediabetes and what it means: the epidemiological evidence. Annu Rev Public Health. 2021;42:59–77. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090419-102644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saeedi P., Petersohn I., Salpea P., et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: results from the international diabetes federation diabetes atlas, 9th edition. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;157 doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2019.107843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vatcheva K.P., Fisher-Hoch S.P., Reininger B.M., McCormick J.B. Sex and age differences in prevalence and risk factors for prediabetes in Mexican-Americans. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;159 doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2019.107950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaheen M., Schrode K.M., Tedlos M., Pan D., Najjar S.M., Friedman T.C. Racial/ethnic and gender disparity in the severity of NAFLD among people with diabetes or prediabetes. Front Physiol. 2023;14 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2023.1076730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Almeda-Valdes P., Gómez Velasco D.V., Arellano Campos O., et al. The SLC16A11 risk haplotype is associated with decreased insulin action, higher transaminases and large-size adipocytes. Eur J Endocrinol. 2019;180:99–107. doi: 10.1530/EJE-18-0677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams A.L., Jacobs S.B.R., Moreno-Macías H., et al. Sequence variants in SLC16A11 are a common risk factor for type 2 diabetes in Mexico. Nature. 2014;506:97–101. doi: 10.1038/nature12828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bello-Chavolla O.Y., Rojas-Martinez R., Aguilar-Salinas C.A., Hernández-Avila M. Epidemiology of diabetes mellitus in Mexico. Nutr Rev. 2017;75:4–12. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuw030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bello-Chavolla O.Y., Antonio-Villa N.E., Fermín-Martínez C.A., et al. Diabetes-related excess mortality in Mexico: a comparative analysis of national death registries between 2017–2019 and 2020. Diabetes Care. 2022;45:2957–2966. doi: 10.2337/dc22-0616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knowler W.C., Barrett-Connor E., Fowler S.E., et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group Long-term effects of lifestyle intervention or metformin on diabetes development and microvascular complications over 15-year follow-up: the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3:866–875. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00291-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Echouffo-Tcheugui J.B., Perreault L., Ji L., Dagogo-Jack S. Diagnosis and management of prediabetes: a review. JAMA. 2023;329:1206–1216. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.4063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blond M.B., Færch K., Herder C., Ziegler D., Stehouwer C.D.A. The prediabetes conundrum: striking the balance between risk and resources. Diabetologia. 2023 doi: 10.1007/s00125-023-05890-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization, Federation ID . World Health Organization; 2006. Definition and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and intermediate hyperglycaemia : report of a WHO/IDF consultation.https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43588 [Google Scholar]

- 15.International Expert Committee International Expert Committee report on the role of the A1C assay in the diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1327–1334. doi: 10.2337/dc09-9033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.ElSayed N.A., Aleppo G., Aroda V.R., et al. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of care in diabetes—2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46:S19–S40. doi: 10.2337/dc23-S002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ford E.S., Zhao G., Li C. Pre-diabetes and the risk for cardiovascular disease: a systematic review of the evidence. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1310–1317. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.10.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romero-Martínez M., Shamah-Levy T., Cuevas-Nasu L., et al. Diseño metodológico de la Encuesta nacional de Salud y nutrición de Medio Camino 2016. Salud Publica Mex. 2017;59:299. doi: 10.21149/8593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Romero-Martínez M., Shamah-Levy T., Vielma-Orozco E., et al. Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición 2018-19: metodología y perspectivas. Salud Publica Mex. 2019;61:917–923. doi: 10.21149/11095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Romero-Martínez M., Barrientos-Gutiérrez T., Cuevas-Nasu L., et al. Metodología de la Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición 2020 sobre Covid-19. Salud Publica Mex. 2021;63:444–451. doi: 10.21149/12580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Romero Martínez M., Barrientos-Gutiérrez T., Cuevas-Nasu L., et al. Metodología de la Encuesta nacional de Salud y nutrición 2021. Salud Publica Mex. 2021;63:813–818. doi: 10.21149/13348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Romero-Martínez M., Barrientos-Gutiérrez T., Cuevas-Nasu L., et al. Metodología de la Encuesta nacional de Salud y nutrición 2022 y planeación y diseño de la Ensanut continua 2020-2024. Salud Publica Mex. 2022;64:522–529. doi: 10.21149/14186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sepúlveda J., Tapia-Conyer R., Velásquez O., et al. Diseño y metodología de la Encuesta Nacional de Salud 2000. Salud Publica Mex. 2007;49:s427–s432. [Google Scholar]

- 24.HOMA2 calculator: overview. https://www.dtu.ox.ac.uk/homacalculator/

- 25.Arellano-Campos O., Gómez-Velasco D.V., Bello-Chavolla O.Y., et al. Development and validation of a predictive model for incident type 2 diabetes in middle-aged Mexican adults: the metabolic syndrome cohort. BMC Endocr Disord. 2019;19:41. doi: 10.1186/s12902-019-0361-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.The IDF consensus worldwide definition of the metabolic syndrome. Obes Metabol. 2005;2:47–49. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Índice rezago social 2020. https://www.coneval.org.mx/Medicion/IRS/Paginas/Indice_Rezago_Social_2020.aspx

- 28.Antonio-Villa N.E., Fernandez-Chirino L., Pisanty-Alatorre J., et al. Comprehensive evaluation of the impact of sociodemographic inequalities on adverse outcomes and excess mortality during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Mexico City. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;74:785–792. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Antonio-Villa N.E., Bello-Chavolla O.Y., Fermín-Martínez C.A., et al. Socio-demographic inequalities and excess non-COVID-19 mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic: a data-driven analysis of 1 069 174 death certificates in Mexico. Int J Epidemiol. 2022;51:1711–1721. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyac184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Survey.pdf. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/survey/survey.pdf

- 31.Proyecciones de la Población de México y de las Entidades Federativas, 2016-2050–datos.gob.mx/busca. https://datos.gob.mx/busca/dataset/proyecciones-de-la-poblacion-de-mexico-y-de-las-entidades-federativas-2016-2050

- 32.Prevalence of prediabetes among adults | diabetes | CDC. 2022; published online sept 21. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics-report/prevalence-of-prediabetes.html

- 33.Gallardo-Rincón H., Montoya A., Saucedo-Martínez R., et al. Integrated Measurement for Early Detection (MIDO) as a digital strategy for timely assessment of non-communicable disease profiles and factors associated with unawareness and control: a retrospective observational study in primary healthcare facilities in Mexico. BMJ Open. 2021;11 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-049836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Basto-Abreu A.C., López-Olmedo N., Rojas-Martínez R., et al. Prevalence of diabetes and glycemic control in Mexico: national results from 2018 and 2020. Salud Publica Mex. 2021;63:725–733. doi: 10.21149/12842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jimenez-Corona A., Nelson R.G., Jimenez-Corona M.E., et al. Disparities in prediabetes and type 2 diabetes prevalence between indigenous and nonindigenous populations from Southeastern Mexico: the Comitan Study. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2019;16 doi: 10.1016/j.jcte.2019.100191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahlqvist E., Storm P., Käräjämäki A., et al. Novel subgroups of adult-onset diabetes and their association with outcomes: a data-driven cluster analysis of six variables. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6:361–369. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bello-Chavolla O.Y., Bahena-López J.P., Vargas-Vázquez A., et al. Clinical characterization of data-driven diabetes subgroups in Mexicans using a reproducible machine learning approach. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2020;8 doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2020-001550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yacamán Méndez D., Zhou M., Trolle Lagerros Y., et al. Characterization of data-driven clusters in diabetes-free adults and their utility for risk stratification of type 2 diabetes. BMC Med. 2022;20:356. doi: 10.1186/s12916-022-02551-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tabák A.G., Herder C., Rathmann W., Brunner E.J., Kivimäki M. Prediabetes: a high-risk state for diabetes development. Lancet. 2012;379:2279–2290. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60283-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bergman M. The 1-hour plasma glucose: common link across the glycemic spectrum. Front Endocrinol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.752329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brannick B., Wynn A., Dagogo-Jack S. Prediabetes as a toxic environment for the initiation of microvascular and macrovascular complications. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2016;241:1323–1331. doi: 10.1177/1535370216654227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang P.L. A comprehensive definition for metabolic syndrome. Dis Models Mech. 2009;2:231–237. doi: 10.1242/dmm.001180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rooney M.R., Rawlings A.M., Pankow J.S., et al. Risk of progression to diabetes among older adults with prediabetes. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:511. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.8774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Richter B., Hemmingsen B., Metzendorf M.-I., Takwoingi Y. Development of type 2 diabetes mellitus in people with intermediate hyperglycaemia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;10:CD012661. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012661.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morris D.H., Khunti K., Achana F., et al. Progression rates from HbA1c 6.0-6.4% and other prediabetes definitions to type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2013;56:1489–1493. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-2902-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cai X., Zhang Y., Li M., et al. Association between prediabetes and risk of all cause mortality and cardiovascular disease: updated meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;370:m2297. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.