Abstract

Question

Recent data suggest that anxiety disorders are as often comorbid with bipolar disorder (BD) as with unipolar depression. The literature on panic disorder (PD) comorbid with BD has been systematically reviewed and subject to meta-analysis.

Study selection and analysis

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines were thoroughly followed for literature search, selection and reporting of available evidence. The variance-stabilising Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation was used in the meta-analysis of prevalence estimates. Both fixed-effect and random-effects models with inverse variance method were applied to estimate summary effects for all combined studies. Heterogeneity was assessed and measured with Cochran’s Q and I2 statistics.

Findings

Overall, 15 studies (n=3391) on cross-sectional prevalence and 25 independent lifetime studies (n=8226) were used to calculate pooled estimates. The overall random-effects point prevalence of PD in patients with BD, after exclusion of one potential outlier study, was 13.0% (95% CI 7.0% to 20.3%), and the overall random-effects lifetime estimate, after exclusion of one potential outlier study, was 15.5% (95% CI 11.6% to 19.9%). There were no differences in rates between BD-I and BD-II. Significant heterogeneity (I2 >95%) was found in both estimates.

Conclusions

Estimates that can be drawn from published studies indicate that the prevalence of PD in patients with BD is higher than the prevalence in the general population. Comorbid PD is reportedly associated with increased risk of suicidal acts and a more severe course. There is no clear indication on how to treat comorbid PD in BD. Findings from the current meta-analysis confirm the highly prevalent comorbidity of PD with BD, implicating that in patients with BD, PD might run a more chronic course.

Background

Patients with bipolar disorder (BD) are exposed to psychiatric comorbidity, with longitudinal rates that can be higher than 50% and may reach even 70%. Psychiatric comorbidity is one of the major reasons BD is often as severe as schizophrenia.1

Psychiatric comorbidity in BD goes often undetected and undertreated in the clinical setting.2 This may depend on clinicians’ inclination to use a single, comprehensive primary diagnosis to deal with the patients, often neglecting the residuals symptomatology. Some symptoms—such as anxiety—may also hide within the multifaceted landscape of BD. Residual untreated symptoms are not unusual in BD with psychiatric comorbidity, and sometimes treatments aimed at the ‘primary’ condition might negatively impact on the course of the comorbid condition, worsening its course.

In patients with BD, anxiety is extremely common, and it can be expressed both as an isolated symptom and as a full-blown syndrome. Kraepelin included anxiety in the core features of BD, also considering it a typical feature of the different clinical subtypes of the major condition. However, it was not until the latest decades that the interest in the manifestations of anxiety in the course of BD peaked in the published literature.

In general, comorbid anxiety is related to worse outcome, may affect recovery, leading to longer time from index mood episode to full remission of symptoms, particularly in depression, may favour earlier relapse, and associates to lower quality of life.3 4 Its treatment is problematic.5–8

Age at onset in patients with comorbid panic disorder (PD) was reported to be younger than in those without comorbidity.9 More depressive episodes, and possibly higher risk of suicide and suicide attempt, also were reported.10 11 Indeed, a negative impact of comorbidity of PD with the course and outcome of BD has been described.

Studies reported a wide variability of the cross-sectional prevalence of PD in BD, ranging from 2.3% to 62.5%, while the longitudinal prevalence ranged from 2.9% to 56.5%.12–15

Overall, data on cross-sectional and longitudinal prevalence suggest that patients with BD share with patients with schizophrenia, or unipolar an equivalent rate of PD, which, nevertheless, is several times higher than the rate expected for the general population. However, detailed analysis is lacking. Precise information on comorbidity of PD with BD may serve the purpose of targeting those conditions that are known to affect treatment response and recovery, and that may increase the risk of suicidality and the chance of developing a substance use disorder. Moreover, the treatment of comorbid PD may reveal challenging, both because of the increased risk of adverse effects and the greater chance of medication-induced mood switch.

Objective

This study set out to systematically review the literature about BD comorbid with PD BD. Retrieved data were subject to meta-analysis to extract both cross-sectional (point) and longitudinal rates of comorbidity.

Study selection and analysis

The recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement were followed in performing the review.

Data on the comorbidity of PD with BD were extracted from published literature, which were retrieved from PubMed/MEDLINE, from inception until 1 August 2017, on the basis of a search code that was developed by two authors (KNF, JV).

The following terms were used to scan PubMed database: ‘Bipolar’ (all fields) OR ‘manic’ (all fields) OR ‘mania’ (all fields) OR ‘manic depression’ (all fields) OR ‘manic depressive’ (all fields) AND ‘panic’ (all fields).

Online details the combination of search terms that were used in the PubMed/MEDLINE interrogation, as well as all other search details.

Only studies in the English language were included. The search was enriched by a thorough scan of the reference lists of relevant books and reviews.13–17

A first reviewer (KNF) conducted a screen of titles and abstracts of the extracted list of references for inclusion, with a validation check by a second reviewer (JV). In case of uncertainty on inclusion, the full-text article was accessed. Discrepancies were solved through discussion, until the achievement of a consensus.

Criteria for study selection

Studies that included primary data concerning the comorbidity of PD in adult (over 18 years old) patients with BD: essentially, the number of patients with confirmed diagnosis of BD and with a comorbid diagnosis of PD.

Studies published in the English language.

Data abstraction and quality assessment

A previously pilot-tested standardised coding system was used by two authors (JV, KNF) for data extraction. The following information was derived from the articles: authors’ name, publication year, location, sample size, criteria for diagnosis, procedure for diagnosis (either clinical decision or diagnosis based on standardised or semistandardised interview), number of cases with BD, number of cases with PD and number of cases with any other diagnostic group when used as comparison. For each study, one reviewer (KNF) abstracted the relevant data and a second reviewer (JV) verified the extraction for completeness and accuracy. Discrepancies in extraction/scoring were solved through discussion.

Findings

Eventually, 16 studies with cross-sectional data and 26 with longitudinal data were included in the analysis. Overall, nine studies with data on BD-I were entered in the related sensitivity analysis, while four studies with data on BD-II were entered in the sensitivity analysis on BD-II.

The PRISMA flow chart is shown in the online. The detailed results are also shown in the online supplementary appendix. The included studies with cross-sectional estimates are reported in table 1, while the details on included studies with lifetime estimates are reported in table 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis concerning the cross-sectional prevalence of panic disorder in patients with bipolar disorder

| Study | Location | Diagnostic group | Criteria for diagnosis | Procedure for diagnosis | n | % Male | Age | Prevalence, n (%) |

Comments |

| Bellani et al (2012) | University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, USA | BD | DSM-IV | SCID | 205 | 60 (29.3%) | 36.6±11.5 | 60 (29.3) | Rates of depressive episodes are similar in the two study groups. |

| MDD | 105 | 31 (29.5%) | 38.0±13.1 | 10 (9.8) | |||||

| Boylan et al (2004) | McMaster Regional Mood Disorders Program (Hamilton, Ontario, Canada) |

BD | DSM-IV | SCID | 138 | 31.9% | ~41 | 37 (26.8) | Outpatient sample, including 70.3% BD-I and 29.7% rapid cycling. |

| Ciapparelli et al (2007) | Department of Psychiatry, Neurobiology, Pharmacology and Biotechnology, University of Pisa, Italy | Schiz | DSM-IV | SCID | 23 | 19 (82.6%) | 36.5±8.8 | 24 (24.5) | BD with psychotic features. |

| Schizoaff | 19 | 14 (73.7%) | 34.9±10.6 | ||||||

| BD | 56 | 46 (83.6%) | 35.8±12.1 | ||||||

| Coryell et al (2009) | Multisite (USA) | BD-I (mania) | DSM-IV | SCID | 92 | 63 | 36.5±13.3 | 1 (1.1) | |

| BD-I (depression) | 168 | 59 | 36.6±14.4 | 9 (5.4) | |||||

| BD-I (cycling) | 167 | 75 | 35.9±11.9 | 7 (4.2) | |||||

| Dilsaver and Chen (2003) | Harris County Psychiatric Hospital, Houston, Texas, USA | BD-I (mania) | DSM-III-R | SCID | 19 | 47.4% | 30.9±8.8 | 1 (4.0) | In the sample of patients with pure mania, >90% had psychotic features. In the sample with depressive mania, >90% had psychotic features. |

| BD-I (depressive mania) | 25 | 56.0% | 34.7±8.9 | 16 (84.2) | |||||

| Dilsaver et al (1997) | Harris County Psychiatric Center, University of Texas, Houston, USA | Bipolar depression | DSM-III-R | SCID | 53 | 33 (62.3) | |||

| Pure mania | 32 | 1 (2.3) | |||||||

| Depressive mania | 44 | 20 (62.5) | |||||||

| Okan Ibiloglu and Caykoylu (2011) | Psychiatry Outpatient Clinics, Ataturk Training and Teaching Hospital, Ankara, Turkey | BD-I | DSM-IV | SCID | 50 | 17 (34.0%) | 37.8±9.51 | 30 (60.0) | |

| BD-II | 46 | 12 (26.1%) | 22 (47.8) | ||||||

| Pini et al (2003) | Department of Psychiatry, Neurobiology, Pharmacology and Biotechnology, University of Pisa, Italy | BD-I | DSM-III-R | SCID | 151 | 43.7% | 35 (23.2) | ||

| Strakowski et al (1992) | Psychotic Disorders Program, McLean Hospital and the Consolidated Department of Psychiatry, Harvard University Medical School | BD-I (manic or mixed) | DSM-III-R | SCID | 41 | 39.0% | 29.5±12.7 (manic) | 2 (4.9) | Sample of inpatients with first episode of mania or mixed status. |

| 40.4±11.7 (mixed) | |||||||||

| Vieta et al (2001) | BDs Programme of the Hospital Clinic and University of Barcelona | BD-I | DSM-III-R | SCID | 129 | 14 (35%) | 39.7±10.96 (with psychiatric comorbidity) | 3 (2.3) | Sample of patients in remission, all with BD-I. |

| 39 (39%) | 41.51±15.21 (without) | ||||||||

| Cosoff and Hafner (1998) | Adelaide, Australia | BD | DSM-III-R | SCID | 20 | 60% | 34.8±10 (men) | 3 (15.0) | |

| Schiz | 60 | 34.9±9.6 (women) | 3 (5.0) | ||||||

| Schizoaff | 20 | ||||||||

| Dell’Osso et al (2011) | University Department of Psychiatry of Milan, Italy | BD | DSM-IV | SCID | 508 | 224 (44.1%) | >40 | 32 (6.3) | 56.7% BD-I, 76.1% without any substance or alcohol abuse. |

| Mantere et al (2006) | Mood Disorders Research Unit, NPHI, Helsinki, Finland | BD | DSM-IV | SCID | 191 (90: BD-I; 101: BD-II) | 47.1% | 37.7±12.2 | 46 (24.1) | Acute-phase BD, 47.1% BD-I, inpatients or outpatients. 32.5% with rapid cycling. 16.2% with psychotic symptoms. |

| MDD | 269 | 26.8% | NA | 45 (16.7) | |||||

| McElroy et al (2001) | Multisite (USA and the Netherlands) | BD | DSM-IV | SCID | 288 | 44.0% | 42.8±11.3 | 27 (9.4) | STANLEY Foundation data. |

| Simon et al (2004) | Multisite (USA) | BD-I | DSM-IV | SCID | 360 | 40.6% | 41.7±12.8 | 33 (9.2) | First 500 patients of STEP-BD. |

| BD-II | 115 | 5 (4.4) | |||||||

| Otto et al (2006) | Multisite (USA) | BD | DSM-IV | SCID | 918 | 41.0% | 40.6±12.7 | 78 (8.5) | First 1000 patients of STEP-BD. >75% BD-I, 50% in recovery, ~25% depressed. |

| Tamam and Ozpoyraz (2002) | Cukurova University, Adana, Turkey | BD-I | DSM-IV | SCID | 70 | 29 (41.6%) | 33.4±10.3 | 4 (5.7) | Included only patients with BD-I. |

| Zutshi et al (2006) | National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore, India | BD | DSM-IV | SCID | 80 | 57 (71.3%) | 30.06±7.77 | 4 (5.0) | Patients with BD in remission; the controls were relatives of neurological patients. |

| Controls | 50 | 38 (76.0%) | 31.44±7.85 | 0 (0) |

BD, bipolar disorder; DSM, Diagnostic Statistic Manual; MDD, major depressive disorder; Schiz, schizophrenia; NA, not available; Schizoaff, schizo-affective disorder; SCID, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM; STEP-BD, Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for BD.

Table 2.

Characteristics of studies included in meta-analysis concerning the lifetime prevalence of panic disorder in patients with bipolar disorder (see online

| Study | Location | Diagnostic group | Criteria for diagnosis | Procedure for diagnosis | n | Age | Male (%) | Prevalence, n (%) |

Comments |

| Altshuler et al (2010) | Stanley Foundation Bipolar Treatment Outcome Network | BD-I BD-II |

DSM-IV | SCID | 572 139 |

Male: 43.5±12.4 Female: 40.7±10.9 |

34 (4.78%) | 96 (13.5) | >80% BD-I, STANLEY Foundation data |

| Azorin et al (2009) | Sainte Marguerite Hospital, University of Marseilles | BD-I | DSM-IV | SCID | 1090 | 43±14 | 56 (5.1) | Hospitalised patients with acute mania | |

| Chen and Dilsaver (1995); Robins and Regier (1991) | Harris County Psychiatric Centre (HCPC), University of Texas, Houston | BD-I | DSM-III | SCID | 168 | 9 (17.3%) | 35 (20.8) | Epidemiological catchment area | |

| MDD | 557 | 17 (8.3%) | 56 (10.0) | ||||||

| General population | 17 143 | 138 (0.8) | |||||||

| Coryell et al (2009) | Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia-Presbyterian Hospital in New York City, Rush Presbyterian Hospital in Chicago, Washington University in St Louis, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics in Iowa City | BD-I | DSM-IV | SADS | 290 | Mania: 36.5±13.3 Depression: 36.6±14.4 Cycling: 35.9±11.9 |

17 (4.0) | ||

| BD-II | 143 | ||||||||

| Craig et al (2002) | Suffolk County Mental Health Project (12 inpatient facilities of Suffolk County, New York) Public sector outpatient clinic for the destitute in Starr County National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions |

BD with psychosis | DSM-III-R | SCID, Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-DSM-IV Version | 138 | 15–60 years | 4 (2.9) | BD with psychosis | |

| MDD with psychosis | 87 | 6 (5.2) | |||||||

| Schiz/schizoaff | 225 | 9 (4.0) | |||||||

| Dilsaver et al (2008) | Suffolk County Mental Health Project (12 inpatient facilities of Suffolk County, New York) | BD | DSM-IV | SCID | 69 | BD: 34.9±11.8 Unipolar: 36.9±12.8 |

BD: 36.2% Unipolar: 31.2% |

39 (56.5) | Data from Latinos |

| MDD | 118 | 27 (22.9) | |||||||

| Goldstein and Levitt (2008) | Public sector outpatient clinic for the destitute in Starr County | BD | DSM-IV | SCID | 1411 | Male: 35.3±16.7 Female: 40±16.2 |

432 (74.6%) | 853 (60.4) | 2001–2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions |

| Henry et al (2003) | Charles Perrens Hospital, Bordeaux, Chenevier Hospital, Creteil | BD | DSM-IV | French version of DIGS | 318 | 53.3±15.1 | 41% | 52 (16.4) | 75% BD-I, half psychotic currently or longitudinal |

| Kawa et al (2005) | South Island Bipolar Study in New Zealand (Otago, Southland, and Canterbury regions of New Zealand) | BD | DSM-IV | DIGS | 211 | Male: 43 Female: 44 |

17 (15.0%) | 41 (19.4) | |

| Kessler et al (1997) | National Comorbidity Survey of the USA | BD | DSM-III-R | CIDI | 29 | 15–54 | 49.1% | 8 (33.1) | BD-I National Comorbidity Survey |

| Levander et al (2007) | Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network (University of California Los Angeles; University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas; University of Cincinnati; NIMH, Bethesda; University Medical Centre, Utrecht; University of Munich | BD-I | DSM-IV | SCID | 276 | AUD: 41.6±11.2 No AUD: 41.7±11.2 |

28 (8.0%) | 54 (19.5) | STANLEY Foundation data, 2/3 with alcohol use |

| BD-II | 71 | 18 (25.4) | |||||||

| Schizoaff | 3 | 0 (0) | |||||||

| McElroy et al (2001b) | Stanley Foundation Bipolar Treatment Outcome Network | BD | DSM-IV | SCID-P and clinician-administered and self-rated questionnaires | 288 | 42.8±11.3 | 58 (20.1) | STANLEY Foundation data | |

| Mula et al (2008) | Multicentre Italian study University Hospital Outpatient Psychiatric Department of the University of Pisa and from three collaborating community mental health centre outpatient clinics |

BD-I | DSM-IV | SCID-I, SCID-P | 70 | 41.3±11.6 | 43% | 50 (27.6) | |

| BD-II | 51 | 48.1±11.7 | 43% | ||||||

| MDD | 60 | 49.2±11 | 30% | ||||||

| Nakagawa et al (2008) | Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network (University of California Los Angeles; University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas; University of Cincinnati; NIMH, Bethesda; University Medical Centre, Utrecht; University of Munich | BD | DSM-III-R | SCID | 116 | 18–73 years | 34.5% | 37 (31.9) | BD depression |

| Pini et al (1997) | Stanley Foundation Bipolar Treatment Outcome Network | BD | DSM-III-R | SCID-P and clinician-administered and self-rated questionnaires | 24 | 37.9±12.0 | 11 (45.4%) | 9 (36.8) | BD depression |

| MDD | 38 | 15 (24.0) | |||||||

| Dysthymia | 25 | ||||||||

| Rihmer et al (2001) | BD-I | DSM-III-R | Hungarian version of the DIS | 95 | 18–64 years | 7 (7.4) | Patients with BD-I and BD-II, Hungarian epidemiological study | ||

| BD-II | 24 | 3 (12.5) | |||||||

| MDD | 443 | 55 (12.4) | |||||||

| Schaffer et al (2006) | Canadian Community Health Survey: Mental Health and Well-Being | BD | DSM-IV | WMH-CIDI | 852 | 37.3±13.7 | 60 (15.5%) | 164 (19.3) | Canadian Community Health Survey: Mental Health and Well-Being |

| Simon et al (2004) | STEP-BD (multicentre project funded by the NIMH, USA) | BD-I | DSM-IV | Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI Plus V.5.0) | 360 | 41.7±12.8 | 40.6% | 66 (18.3) | STEP-BD data |

| BD-II | 115 | 16 (13.9) | |||||||

| Slama et al (2004) | Two university-affiliated hospitals (in Paris and Bordeaux, France) | BD | DSM-IV | Semistructured diagnostic interviews (the DIGS and the Family Interview for Genetic Studies) | 307 | 44.2±14.7 | 124 (40.4%) | 25 (7.9) | Patients in remission |

| Szadoczky et al (1998) | BD | DSM-III-R | Hungarian version of the DIS | 149 | 44% | 16 (10.6) | Epidemiological study | ||

| MDD | 443 | 55 (12.4) | |||||||

| Tamam and Ozpoyraz (2002) | Balcali Hospital, Cukurova University, Adana, Turkey | BD-I | DSM-IV | SCID, Hamilton Depression Scale, Bech-Rafaelsen Mania Scale | 70 | 33.4±10.3 | 29 (41.6%) | 7 (10.0) | BD-I |

| Yerevanian et al (2001) | Mood disorders clinic of a major university centre Bipolar Clinic of the Mood Disorders Programme, Clarke Institute of Psychiatry, University of Toronto |

BD-I: 8 | DSM-III | SCID-P SADS-Longitudinal Version |

8 | 40.4±15.1 | 5 (62.5%) | 2 (5.7) | Most patients with BD-II |

| BD-II: 27 | 27 | 39.5±11.8 | 13 (51.9%) | ||||||

| MDD | 98 | 18 (18.4) | |||||||

| Young et al (1993) | Psychotic disorders unit, McLean Hospital, Belmont, Massachusetts, USA | BD | NA | SCID-I | 81 | 37.6 | 32 (39.5%) | 26 (32.1) | |

| Young et al (2013) | National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore, India | BD | DSM-IV-TR | SCID-CV | 304 | 36.92±13.55 | 49.34% | 21 (6.9) | |

| Zutshi et al (2006) | Hospitals of Taiwan | BD | DSM-IV | Chinese versions of CIDI and SCID | 80 | 30.06±7.77 | 57 (71%) | 6 (7.5) | BD patients in remission |

| Controls | 50 | 0 (0.0) | |||||||

| Tsai et al (2012) | BD-I | DSM-IV | Hungarian version of the DIS | 306 | 37.07±12.3 | 147 (48.03%) | 36 (12.6) |

AUD, alcohol use disorder; BD, bipolar disorder; CIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Interview; DIGS, Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies; DIS, Diagnostic Interview Schedule; DSM, Diagnostic Statistic Manual; DSM-III-R, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition, Revised; DSM-IV-TR, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition (Text Revision); MDD, major depressive disorder; NA, not available; NIMH, National Institute of Mental Health; SADS, Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizofrenia; Schiz, schizophrenia; Schizoaff, schizo-affective disorder; SCID, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM; SCID-I, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Axis I Disorders; SCID-CV, Structured Clinic Interview for DSM, Clinician Version; SCID-P; Structured Clinic Interview for DSM, Patient Version; STEP-BD, Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for BD; WMH, WHO World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative.

Cross-sectional (point) prevalence of comorbid PD

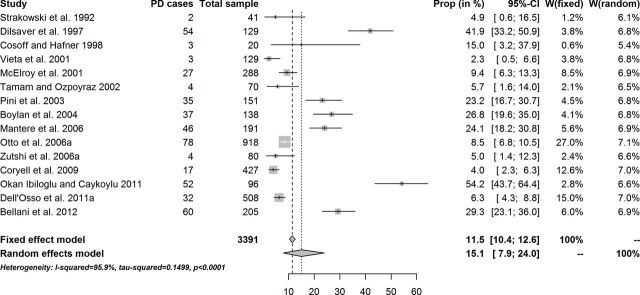

The overall cross-sectional estimate of PD in patients diagnosed with BD was 11.5% (95% CI 10.4% to 12.6%) in the fixed-effect model, and it was 15.1% (95% CI 7.9% to 24.0%) in the random-effects model (figure 1). Across studies there was a variation in the cross-sectional prevalence of PD in BD, a likely reflection of the sociodemographics and clinical characteristics of the samples (figure 1). No relevant publication bias emerged from the funnel plot and the Egger’s or Begg and Mazumdar rank correlation test. Heterogeneity was substantial: I2=95.9% (95% CI 94.5% to 97.0%), estimated between-study variance=0.15 (figure 1 and table 3). However, the Baujat plot suggested that the studies with the greatest contribution to the overall heterogeneity had a small to moderate influence on the result but one. The standardised residuals plot and the radial plot suggested just one sample was potential outlier.

Figure 1.

Cross-sectional prevalence of panic disorder (PD) in patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

Table 3.

Effect sizes in the meta-analysis of studies on panic disorder in patients with bipolar disorder

| k | n | Prevalence, n (%) | 95% CI (%) | Q | P value | I2, n (%) | 95% CI (%) | |

| Cross-sectional studies | ||||||||

| FE model | 15 | 3391 | 11.5 | 10.4 to 12.6 | ||||

| RE model | 15 | 3391 | 15.1 | 7.9 to 23.9 | 343.5 | <0.001 | 95.9 | 94.5 to 97.0 |

| RE model without outliers | 14 | 3295 | 13.0 | 7.0 to 20.3 | 253.9 | <0.001 | 94.9 | 92.9 to 96.3 |

| RE in subgroup analysis 1 | 7 | 1228 | 12.3 | 1.2 to 31.3 | 120.9 | <0.001 | 95.0 | 92.0 to 96.9 |

| FE in subgroup analysis 2 | 2 | 161 | 12.9 | 8.0 to 18.7 | ||||

| Subgroup analysis 1: BD-I samples only. Subgroup analysis 2: BD-II samples only; since there were two studies only, the FE model was reported. | ||||||||

| Longitudinal studies | ||||||||

| FE model | 25 | 8226 | 15.5 | 14.7 to 16.3 | ||||

| RE model | 25 | 8226 | 16.8 | 12.2 to 22.0 | 546.5 | <0.001 | 95.6 | 94.5 to 96.5 |

| RE model without outliers | 24 | 8157 | 15.5 | 11.6 to 19.9 | 491.7 | <0.001 | 95.3 | 94.0 to 96.3 |

| RE in subgroup analysis 1 | 9 | 2852 | 14.0 | 8.0 to 20.9 | 137.7 | <0.001 | 94.2 | 91.0 to 96.3 |

| RE in subgroup analysis 2 | 4 | 217 | 14.8 | 1.7 to 35.8 | 11.1 | 0.011 | 73.1 | 24.2 to 90.4 |

| Subgroup analysis 1: BD-I samples only. Subgroup analysis 2: BD-II samples only. | ||||||||

BD, bipolar disorder; FE, fixed-effect model; k, number of included studies; n, number of patients in the included studies; RE, random-effects model with empirical Bayes estimator.

Indeed, this sample, with patients with both BD-I and BD-II, had one of the highest cross-sectional estimated prevalence of PD.

After exclusion of this outlier, the overall fixed-effect cross-sectional estimate of PD in patients diagnosed with BD went to a small decrease, being now 10.6% (9.5%–11.7%), while the random-effects estimate was 13.0% (7.0%–20.3%) (table 3).

Subgroup analyses, with inclusion/exclusion of studies according to the nature of the sample, did not reveal relevant changes in the estimates of the random-effects model, nor a substantial attenuation of heterogeneity (see table 3 for details).

No difference in cross-sectional prevalence rates was found between BD-I and BD-II.

The meta-regression of data without the outlier on age and gender ratio showed that neither age (coefficient=0.011; z=−0.48; P=0.64; I2=94.6%) nor gender ratio (coefficient=−0.150; z=−0.94; P=0.36; I2=94.6%) was related to the cross-sectional prevalence estimate of PD in BD.

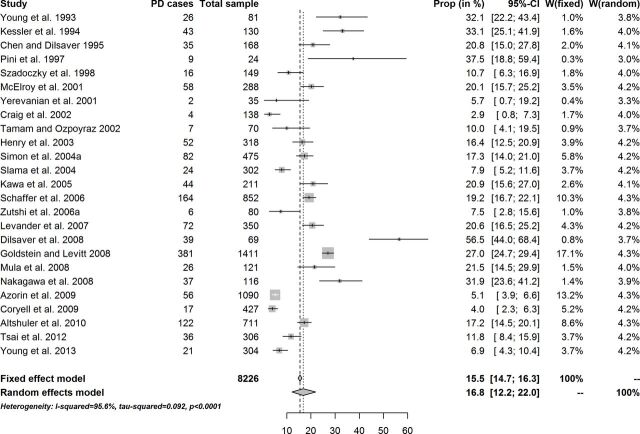

Longitudinal prevalence of comorbid PD

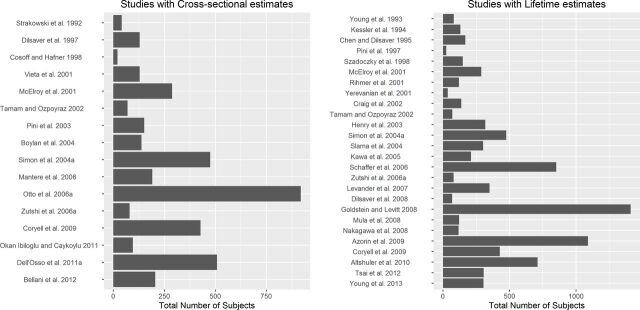

There were 26 studies detailing data on lifetime prevalence of PD in patients diagnosed with BD (figure 2), yielding 25 rates, some of them further grouped into BD-I and BD-II estimates (table 2). The longitudinal estimate of PD in patients diagnosed with BD was 15.5% (95% CI 14.7% to 16.3%) in the fixed-effect model, and it was 16.8% (95% CI 12.2% to 22.0%) in the random-effects model. Again, the composition of the sample by sociodemographic (male:female ratio, age range) and clinical (BD subtypes, phase of the disorder at assessment) variables conditioned a wide variability of the longitudinal prevalence of PD across studies (figure 3).

Figure 2.

Lifetime prevalence of panic disorder (PD) in patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

Figure 3.

Graphical representation of the sample size of studies reporting cross-sectional and lifetime estimates of panic disorder in patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

Some asymmetry, suggesting publication bias, emerged from the funnel plot, but the Egger’s or Begg and Mazumdar rank correlation test did not reveal statistically significant bias. Heterogeneity was substantial: I2=95.6% (95% CI 94.5% to 96.5%). The Baujat plot suggested that two studies among those with the greatest contribution to the overall heterogeneity also had the greatest influence on the result. However, the radial plot and the standardised residuals plot suggested just one potential outlier, and a different one.

After exclusion of one potential outlier study, the longitudinal estimate of PD in patients diagnosed with BD was 15.5% (95% CI 11.6% to 19.9%) in the random-effects model. No difference in longitudinal prevalence rates was found between BD-I and BD-II (table 3).

Heterogeneity remained substantial in analyses by subgroup, suggesting the sample diagnosis or phase of the disorder was not the main reason explaining it (table 3). Meta-regression showed no relationship of estimates with age (coefficient=0.005; z=0.44; P=0.66; I2=95.9%), gender ratio (coefficient=−0.029; z=−0.38; P=0.70; I2=92.8%) or the diagnostic procedure (Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic Statistic Manual (DSM) vs any other: coefficient=0.039; z=0.34; P=0.73; I2=95.5%).

Comparison of BD with other diagnoses

Table 3 summarises the details on the prevalence rates of PD in patients with BD. Cross-sectional pooled rates indicate that 13% of patients with BD suffer from PD. This estimate is roughly similar to that reported for patients with schizophrenia or unipolar depression, and it is several times higher than the rate expected for the general population. The pooled longitudinal rate for PD in patients with BD is 15.5%, which is similar to that reported for patients with unipolar depression but several times higher in comparison with that reported in the control population.

PD probably presents with a chronic rather than episodic course in patients with BD and unipolar depression, as suggested by the negligible difference between cross-sectional and longitudinal prevalence.

The prevalence of PD in people without comorbid disorder was reported in just one study, and it was 0% (out of 50 subjects), way much lower than the prevalence found in patients with BD in the same study (5%) or the estimates found in the present meta-analysis.

Cross-sectional estimates of PD in patients with BD were confronted with those observed in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) in two studies only. A higher cross-sectional prevalence of PD in patients with BD was found than in patients with MDD: test for subgroup differences (based on random-effects model): Q=7.98, df=1, P=0.0047. However, in these two studies the cross-sectional estimates of PD in patients with BD were higher than the pooled estimates in the overall meta-analysis on cross-sectional data. Moreover, heterogeneity was substantial: I2=86.4% (66.9%–94.4%); Q=22.0, df=3, P<0.0001.

Six studies (published in seven papers) reported longitudinal estimates of PD in patients with BD and with MDD. No statistically significant difference was detected in the longitudinal prevalence of PD in patients with BD or MDD: test for subgroup differences (based on random-effects model): Q=0.05, df=1, P=0.82. Heterogeneity was substantial: I2=88.2% (81.3%–92.6%); Q=93.3, df=11, P<0.0001.

Conclusions and clinical implications

There is a consensus in the literature of higher rate of psychiatric comorbidity in patients with BD, but with some inconclusiveness about the rates of specific comorbid disorders. Several methodological issues contribute to these inconsistencies. Studies differ in the characteristics of the population under study, by gender, age and composition of samples in terms of BD subtypes or phase of the disorder at the time of assessment. The methods of assessment also influence the chance of correct detection of the cases. Trained lay interviewers are usually employed in epidemiological studies, while clinical studies more often rely on highly experienced researchers. Thus, reliability is often higher in clinical studies, at the expense of the inclusion of more severe cases. Conversely, epidemiological studies, which apply structured interviews, may yield artificially inflated rates because of the multiple allocation of the same symptom.16

The current paper analysed 15 studies with data on cross-sectional (point) prevalence of PD in BD (n=3391). It also analysed 25 studies with longitudinal data (n=8226). Cross-sectional prevalence of PD ranged in these studies from 2.3% to 62.5%, while longitudinal prevalence ranged from 2.9% to 56.5%. The analysis returned a random-effects point prevalence (after exclusion of one potential outlier study) of 13.0% (95% CI 7.0% to 20.3%), and a random-effects lifetime estimate (after exclusion of one potential outlier study) of 15.5% (95% CI 11.6% to 19.9%).

Significant heterogeneity was found in both cross-sectional and longitudinal meta-analysis (94.9% and 95.3%, respectively). In a previous meta-analysis, lifetime comorbidity of PD in patients with BD was equal to 16.8% (95% CI 13.7 to 20.1),18 a similar estimate to ours.

There is some evidence that patients with pure mania quite never report panic, which, conversely, is much more prevalent in patients with mixed states or depression (up to 80%, depending on the sample), and often the picture is very complex.19 Patients regularly admitted to hospital are likely to display higher rates of psychiatric comorbidity, including PD, than those treated primarily in the community. As a consequence, clinical samples including hospitalised patients with BD will include a higher proportion of patients with psychiatric comorbidity.

As far as PD is concerned, in the general population the 12-month prevalence of PD was found to vary from 0.8% to 2.8%,20–25 while the lifetime prevalence was reported to range from 1.4% to 5.1%.21 23 24 26–28 Thus the reported rates for patients with BD are approximately more than 7-fold higher for cross-sectional prevalence, and more than 4.5-fold higher for longitudinal prevalence, than in the general population. It is worth noticing that the longitudinal rates are approximately double of the cross-sectional rates in the general population (although some overlap was also reported), while in patients with BD these rates are very close. It can be advanced that in patients with BD, PD is rather exclusively chronic and not episodic, and probably related to temperament,29 which does not seem to be the case in the general population.

In the current analysis, both point and longitudinal estimates of PD in BD were related to significant heterogeneity, which probably reflects heterogeneity in sample composition, differences in methodology and medical settings, as well as geographical differences. No relationship of the prevalence rates with age or gender ratio was found, which is consistent with the incidence and prevalence of PD in the general population.

This widely accepted worst outcome of BD when comorbid with PD may depend on PD being often complicated by symptoms of depression,30–32 which may trigger a depressive phase in the course of the BD or agitation.33

A higher risk of suicide and suicide attempt was reported in patients with BD comorbid with PD. The frequent association of PD with major depression or substance use and related disorders might explain this finding. As a matter of fact, the evidence in so far is inconclusive. Some studies reported an increased risk of suicide attempts and self-harm in BD comorbid with PD, while other studies failed to find such an association.10

Overall, the treatment of BD is complex, while the treatment of many of its facets remains poorly researched.5–8 While in general antidepressants are the treatment of choice for PD, this might not be the case in patients with BD (at least not in monotherapy) because of the risk of inducing or exacerbating mania. Patients with BD comorbid with PD are ideal candidates to the use of mood stabilisers, since there is evidence that lithium, lamotrigine and valproic acid/divalproex sodium may alleviate symptoms of anxiety both alone and in combination with antidepressants or second-generation antipsychotics, especially in mixed and rapid cycling patients.34–39 However, the impact of PD on mood stabilisation and the load of caregiver burden is unclear,40 and hard data are not available for the treatment of PD in the frame of BD, neither concerning pharmacotherapy nor psychotherapy.41 42 The true risk for committing suicide under antiepileptic drugs is still a matter of debate,43–45 while psychosocial interventions do not seem to attenuate it.46–49

It is worth noticing that most of the papers included in this systematic review were not identified through the scanning of the search engine (PubMed/MEDLINE), but instead they were derived from reference lists of review papers and books. There is no clear explanation for this, but it is possible that the MEDLINE algorithm was unable to locate the information when the search is aimed at data that were not clearly related to the main objective of the study. Overall, accuracy and completeness of review and meta-analytic studies cannot be assured when the data are retrieved from secondary sources, since there always might be an additional secondary source unknown to the authors.

An additional problem hampers the validity of the findings that can be derived from systematic reviews and meta-analysis studies that are based on psychiatric comorbidity in BD. Standard criteria assume that a comorbid anxiety disorder should be diagnosed in BD only if one can ascertain the independence of the symptoms of the comorbid disorder from those of the main disorder. However, it is probable that most studies reviewed here had used the very simple approach of merely adding up the symptoms. As a matter of fact, no DSM edition made explicit the requirement for independency of symptoms and diagnosis; thus, it cannot be excluded PD symptoms at least partially overlap with some core features of BD (eg, irritability, excitement).

In conclusion, this meta-analysis proved that there is high rate of comorbidity between BD and PD, with prevalence rates that are several times higher than in the general population, although with wide variation across studies. PD probably runs a more chronic course in patients with BD than in the general population. These findings highlight the importance of early detection and treatment of PD in BD to prevent chronic outcome, lessen symptom severity, increase chance of remission from a manic or depressive episode, and reduce the risk of suicide and self-harm.

Footnotes

Funding: AAV is funded by the Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship Program from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Fountoulakis KN, Popovic D, Mosheva M, et al. Mood Symptoms in Stabilized Patients with Schizophrenia: A Bipolar Type with Predominant Psychotic Features? Psychiatr Danub 2017;29:148–54. 10.24869/psyd.2017.148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goodwin GM, Haddad PM, Ferrier IN, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: Revised third edition recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol 2016;30:495–553. 10.1177/0269881116636545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Das A. Anxiety disorders in bipolar I mania: prevalence, effect on illness severity, and treatment implications. Indian J Psychol Med 2013;35:53–9. 10.4103/0253-7176.112202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Coryell W, Solomon DA, Fiedorowicz JG, et al. Anxiety and outcome in bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2009;166:1238–43. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09020218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fountoulakis KN, Grunze H, Vieta E, et al. The International College of Neuro-Psychopharmacology (CINP) Treatment Guidelines for Bipolar Disorder in Adults (CINP-BD-2017), Part 3: The Clinical Guidelines. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2017;20:180–95. 10.1093/ijnp/pyw109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fountoulakis KN, Vieta E, Young A, et al. The International College of Neuropsychopharmacology (CINP) Treatment Guidelines for Bipolar Disorder in Adults (CINP-BD-2017), Part 4: Unmet Needs in the Treatment of Bipolar Disorder and Recommendations for Future Research. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2017;20:196–205. 10.1093/ijnp/pyw072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fountoulakis KN, Yatham L, Grunze H, et al. The International College of Neuro-Psychopharmacology (CINP) Treatment Guidelines for Bipolar Disorder in Adults (CINP-BD-2017), Part 2: Review, Grading of the Evidence, and a Precise Algorithm. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2017;20:121–79. 10.1093/ijnp/pyw100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fountoulakis KN, Young A, Yatham L, et al. The International College of Neuropsychopharmacology (CINP) Treatment Guidelines for Bipolar Disorder in Adults (CINP-BD-2017), Part 1: Background and Methods of the Development of Guidelines. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2017;20:98–120. 10.1093/ijnp/pyw091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schürhoff F, Bellivier F, Jouvent R, et al. Early and late onset bipolar disorders: two different forms of manic-depressive illness? J Affect Disord 2000;58:215–21. 10.1016/S0165-0327(99)00111-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kilbane EJ, Gokbayrak NS, Galynker I, et al. A review of panic and suicide in bipolar disorder: does comorbidity increase risk? J Affect Disord 2009;115(1–2):1–10. 10.1016/j.jad.2008.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Neves FS, Malloy-Diniz LF, Corrêa H. Suicidal behavior in bipolar disorder: what is the influence of psychiatric comorbidities? J Clin Psychiatry 2009;70:13–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. El-Mallakh RS, Hollifield M. Comorbid anxiety in bipolar disorder alters treatment and prognosis. Psychiatr Q 2008;79:139–50. 10.1007/s11126-008-9071-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fountoulakis K. Clinical Description. In: Fountoulakis K, ed. Bipolar disorder: an evidence-based guide to manic depression: Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, 2015:27–80. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fountoulakis K. Long-Term Course. In: Fountoulakis K, ed. Bipolar disorder: an evidence-based guide to manic depression: Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, 2015:81–107. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fountoulakis K. Comorbidity. In: Fountoulakis K, ed. Bipolar disorder: an evidence-based guide to manic depression: Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, 2015:225–340. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fountoulakis KN. Bipolar disorder: an evidence-based guide to manic depression: Springer, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Goodwin F, Jamison K. Manic-depressive illness. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nabavi B, Mitchell AJ, Nutt D. A lifetime prevalence of comorbidity between bipolar affective disorder and anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis of 52 interview-based studies of psychiatric population. EBioMedicine 2015;2:1405–19. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ferentinos P, Fountoulakis KN, Lewis CM, et al. Validating a two-dimensional bipolar spectrum model integrating DSM-5’s mixed features specifier for major depressive disorder. Compr Psychiatry 2017;77:89–99. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2017.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in Europe: results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 2004;420:21–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Grant BF, Hasin DS, Stinson FS, et al. The epidemiology of DSM-IV panic disorder and agoraphobia in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67:363–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Andrade LH, Wang YP, Andreoni S, et al. Mental disorders in megacities: findings from the São Paulo megacity mental health survey, Brazil. PLoS One 2012;7:e31879. 10.1371/journal.pone.0031879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Roy-Byrne PP, Stang P, Wittchen HU, et al. Lifetime panic-depression comorbidity in the national comorbidity survey. Association with symptoms, impairment, course and help-seeking. Br J Psychiatry 2000;176:229–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Jin R, et al. The epidemiology of panic attacks, panic disorder, and agoraphobia in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006;63:415–24. 10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Eaton WW, Kessler RC, Wittchen HU, et al. Panic and panic disorder in the United States. Am J Psychiatry 1994;151:413–20. 10.1176/ajp.151.3.413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. de Jonge P, Roest AM, Lim CC, et al. Cross-national epidemiology of panic disorder and panic attacks in the world mental health surveys. Depress Anxiety 2016;33:1155–77. 10.1002/da.22572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, et al. The cross-national epidemiology of panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997;54:305–9. 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160021003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Eaton WW, Anthony JC, Romanoski A, et al. Onset and recovery from panic disorder in the baltimore epidemiologic catchment area follow-up. Br J Psychiatry 1998;173:501–7. 10.1192/bjp.173.6.501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fountoulakis KN, Gonda X, Koufaki I, et al. The role of temperament in the etiopathogenesis of bipolar spectrum illness. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2016;24:36–52. 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Carvalho AF, Nunes-Neto PR, Castelo MS, et al. Screening for bipolar depression in family medicine practices: prevalence and clinical correlates. J Affect Disord 2014;162:120–7. 10.1016/j.jad.2014.03.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bittner A, Goodwin RD, Wittchen HU, et al. What characteristics of primary anxiety disorders predict subsequent major depressive disorder? J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65:618–26. 10.4088/JCP.v65n0505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lamers F, van Oppen P, Comijs HC, et al. Comorbidity patterns of anxiety and depressive disorders in a large cohort study: the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA). J Clin Psychiatry 2011;72:341–8. 10.4088/JCP.10m06176blu [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Garriga M, Pacchiarotti I, Kasper S, et al. Assessment and management of agitation in psychiatry: expert consensus. World J Biol Psychiatry 2016;17:86–128. 10.3109/15622975.2015.1132007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Reinares M, Rosa AR, Franco C, et al. A systematic review on the role of anticonvulsants in the treatment of acute bipolar depression. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2013;16:485–96. 10.1017/S1461145712000491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Carvalho AF, McIntyre RS, Dimelis D, et al. Predominant polarity as a course specifier for bipolar disorder: a systematic review. J Affect Disord 2014;163:56–64. 10.1016/j.jad.2014.03.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Carvalho AF, Dimellis D, Gonda X, et al. Rapid cycling in bipolar disorder: a systematic review. J Clin Psychiatry 2014;75:e578–86. 10.4088/JCP.13r08905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fountoulakis KN, Kontis D, Gonda X, et al. A systematic review of the evidence on the treatment of rapid cycling bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 2013;15:115–37. 10.1111/bdi.12045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fountoulakis KN, Kontis D, Gonda X, et al. Treatment of mixed bipolar states. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2012;15:1015–26. 10.1017/S1461145711001817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fountoulakis KN, Kasper S, Andreassen O, et al. Efficacy of pharmacotherapy in bipolar disorder: a report by the WPA section on pharmacopsychiatry. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2012;262(Suppl 1):1–48. 10.1007/s00406-012-0323-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pompili M, Harnic D, Gonda X, et al. Impact of living with bipolar patients: Making sense of caregivers’ burden. World J Psychiatry 2014;4:1–12. 10.5498/wjp.v4.i1.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Miziou S, Tsitsipa E, Moysidou S, et al. Psychosocial treatment and interventions for bipolar disorder: a systematic review. Ann Gen Psychiatry 2015;14:19. 10.1186/s12991-015-0057-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pompili M, Innamorati M, Gonda X, et al. Pharmacotherapy in bipolar disorders during hospitalization and at discharge predicts clinical and psychosocial functioning at follow-up. Hum Psychopharmacol 2014;29:578–88. 10.1002/hup.2445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fountoulakis KN, Gonda X, Baghai TC, et al. Report of the WPA section of pharmacopsychiatry on the relationship of antiepileptic drugs with suicidality in epilepsy. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 2015;19:1–10. 10.3109/13651501.2014.1000930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Fountoulakis KN, Gonda X, Samara M, et al. Antiepileptic drugs and suicidality. J Psychopharmacol 2012;26:1401–7. 10.1177/0269881112440514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Siamouli M, Samara M, Fountoulakis KN. Is antiepileptic-induced suicidality a data-based class effect or an exaggeration? A comment on the literature. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2014;22:379–81. 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Fountoulakis KN, Gonda X, Rihmer Z. Suicide prevention programs through community intervention. J Affect Disord 2011;130(1–2):10–16. 10.1016/j.jad.2010.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fountoulakis KN, Gonda X, Siamouli M, et al. Psychotherapeutic intervention and suicide risk reduction in bipolar disorder: a review of the evidence. J Affect Disord 2009;113:21–9. 10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gonda X, Fountoulakis KN, Kaprinis G, et al. Prediction and prevention of suicide in patients with unipolar depression and anxiety. Ann Gen Psychiatry 2007;6:23. 10.1186/1744-859X-6-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rihmer Z, Gonda X, Fountoulakis KN. Suicide prevention programs through education in the frame of healthcare. Psychiatr Hung 2009;24:382–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.