Abstract

Background

Pulmonary radioaerosol mucociliary clearance (PRMC) is a reliable method for assessing in vivo whole lung mucociliary clearance and has been used at the Danish PCD Centre as a supplementary diagnostic test for primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) for more than two decades. This study aimed to investigate genotype-specific differences in PRMC measures and evaluate its potential as an outcome parameter.

Material and methods

The study was based on a retrospective analysis of PRMC tests performed over a 24-year period (1999–2022) in individuals referred for PCD work-up and included patients with genetically confirmed PCD and non-PCD controls. Patients inhaled nebulised technetium-albumin-colloid before static and dynamic imaging was obtained. Three parameters were evaluated: 1-h lung retention (LR1), tracheobronchial velocity (TBV) and cough clearance.

Results

The study included 69 patients from the Danish PCD cohort, representing 26 different PCD genotypes. Mucociliary clearance by PRMC was consistently absent in most PCD patients, regardless of genotype. However, a single patient with a CCDC103 mutation, preserved ciliary function and normal nasal nitric oxide levels exhibited normal LR1 and low TBV values. Voluntary cough significantly improved clearance, with a median improvement of 11% (interquartile range 4–24%).

Conclusion

Absent mucociliary clearance by PRMC should be expected in PCD regardless of genotype but residual ciliary function could result in measurable PRMC. This indicates a potential for PRMC to detect improvements in ciliary function if this can be restored. Addressing involuntary cough and peripheral deposition of radioaerosol is important if PRMC is to be used as an outcome measure in future clinical PCD trials.

Tweetable abstract

Novel insights into PRMC results across PCD genotypes reveal that most PCD patients exhibit a complete absence of lung mucociliary clearance as the baseline but with potential to improve if ciliary function is partially restored https://bit.ly/46LTZwT

Introduction

Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) (Mendelian Inheritance in Man (MIM) 244400) is a multisystem ciliopathy that includes dyskinetic respiratory cilia. The resulting impairment of mucociliary clearance (MC) leads to chronic, destructive, infectious and inflammatory disease of the upper and lower airways.

To date, approximately 50 genes have been identified that harbour variants that cause PCD [1–3]. Most mutations associated with PCD are autosomal recessive. Less frequently, X-chromosomal recessive and de novo autosomal dominant inheritance has been described [4].

Pulmonary radioaerosol mucociliary clearance (PRMC) has been used as a supplementary diagnostic tool in the investigation of PCD in the national Danish PCD Centre for over two decades. It effectively identifies abnormal clearance patterns in patients with PCD caused by impaired MC due to abnormal ciliary motility. The test is noninvasive and involves minimal radiation exposure (<1 mSv). Whole lung retention (LR) of the radioaerosol is visualised by use of a γ-camera. Previous studies have shown PRMC's high sensitivity in predicting PCD and its ability to rule out PCD in non-PCD cases, even in children as young as 5 years old [5–9].

Growing interest in developing ciliary protein correctors for PCD treatment has highlighted the need to establish relevant outcome parameters for future clinical trials. Currently, PRMC is the only available in vivo indicator of ciliary function and MC in the lungs [10]. PRMC has already been used as an outcome parameter in randomised controlled trials for cystic fibrosis [11, 12] and is an obvious candidate for future clinical trials in PCD.

Long-term lung function decline in patients with PCD is heterogeneous [13, 14] and growing evidence indicates that specific PCD gene defects may be related to different lung disease outcomes [14–16]. With patient-specific therapies targeting specific PCD genes on the horizon, exploring genotype–phenotype relationships within subgroups of patients with PCD is more important than ever. With this study, we evaluated PCD PRMC phenotypes in relation to a wide range of PCD genotypes.

Hypothesis and aims

We hypothesised that different PCD genotypes could result in different PRMC measures. Our primary aim was to assess these differences in patients from the Danish PCD cohort.

Three parameters were evaluated: 1-h lung retention (LR1), tracheobronchial velocity (TBV) and cough clearance. By introducing data on TBV as a new, not previously investigated PRMC parameter, we aimed to add this to the PRMC armamentarium of possible outcome measures. We also studied the impact of voluntary and involuntary cough on PRMC measures, because coughing is both unavoidable and encouraged as a treatment manoeuvre in PCD.

As a secondary aim, we evaluated PRMC's usefulness for generating outcome parameters in future PCD clinical trials.

Material and methods

Study design

This retrospective, cross-sectional single-centre study utilised data from the Danish PCD Registry, including re-analysed diagnostic PRMC tests performed from 1999 to 2022. Additional exploratory diagnostic test results, including high-speed video microscopy (HSVM) assessment of nasal ciliary motility and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) assessment of nasal ciliary ultrastructure, as well as PCD genetics and nasal nitric oxide (nNO), were incorporated from outpatient visits during this time.

Inclusion criteria were patients with PCD aged >5 years; confirmation of biallelic mutations in a known PCD-causing gene; previous PRMC test and a complete PRMC record for cough, conducted as part of PCD evaluation, with reliable determination of at least one of the defined PRMC outcome parameters of 1) retention in the lung of the inhaled radioaerosol after 1 h (LR1), 2) TBV or 3) voluntary cough clearance assessment; and presence of clinical symptoms consistent with PCD and positive diagnostic tests (nNO, HSVM and TEM) that align with the current European Respiratory Society (ERS) criteria for PCD diagnosis [17].

Exclusion criteria comprised cough registered within the first 1 h after radioaerosol inhalation and peripheral aerosol deposition that resulted in lack of visible central radioaerosol in the trachea and main bronchi within the first 1 h.

The control group consisted of individuals who underwent PRMC testing in 2022 as part of a full PCD evaluation including HSVM, TEM and nNO in addition to PRMC, with unambiguous negative results and where PCD ultimately had been ruled out. These patients needed to have conclusive PRMC results, including normal LR1, TBV and 24-h LR.

PRMC method

PRMC tests were performed using an identical technique and procedure throughout the 24 years of data acquisition. The PRMC imaging technique has previously been described [5, 7, 10].

In the present study, data were re-analysed with a view to assess the following three defined parameters: PRMC LR1, PRMC TBV and PRMC voluntary controlled and involuntary random cough clearance.

Whereas PRMC LR1 and TBV measurements were confined to only 60 min, cough clearance investigation was prolonged to 120 min. Cough was strictly monitored within these 2 h.

The test lasted 2 h: this included welcoming the patient, placing reference (cobalt-57) markers on the neck and back of the patient and taking the zero-acquisition with the markers, training the patient to do correct slow inhalation and forced exhalation technique with isotonic saline, inhaling the technetium-99m (99mTc)-albumin colloid radioaerosol, measuring static and dynamic PRMC acquisitions, monitoring for cough, removing the reference markers and sending the patient home.

Examples of tracer movement from static acquisitions at 0, 30 and 60 min after radioaerosol inhalation in a patient with PCD and a non-PCD referral are displayed in the supplementary material.

Regional ventilation distribution was visualised by a Krypton-81m (81mKr) gas scintigram. The initial 99mTc aerosol distribution was compared to the 81mKr ventilation distribution to indicate how far the radioaerosol had penetrated into the airways and lungs and hence had to move before being cleared from the airways. This penetration index (PI) was used to calculate each subject's predicted values of LR from previously published reference equations (supplementary material) [10].

Determination of PRMC TBV

To determine PRMC TBV, we re-read the existing digital films from the dynamic acquisitions performed during a PRMC test. Read directly from the screen, we identified distinctive radiomucous boli formed in the tracheobronchial area that further ascended within the main bronchi and the trachea, as displayed in supplementary movie 1 from a patient with PCD and in supplementary movie 2 from a non-PCD referral, which allowed for determination of PRMC TBV, if present. Two dynamic acquisitions of 20-min duration obtained within the first hour of the PRMC investigation were reviewed and analysed for all included patients. Two readers re-analysed each acquisition in a blinded fashion to the original diagnostic report. The transport distance between each frame was measured for any upward boli transport in the main bronchi and trachea.

Because one frame equals 2 min (10 frames in a 20-min acquisition), the PRMC TBV was calculated in mm·min−1 using the following equation:

PRMC TBV=mm of bolus transportation/(Y frames×2 min)

PRMC voluntary controlled and involuntary random cough clearance

Voluntary controlled cough clearance was performed in a subset of patients as repeatable cough manoeuvres at the end of the PRMC measurements. To avoid false-negative results caused by cough clearance, any cases of involuntary random cough during the first hour of a PRMC test were discarded.

We compared these previously discarded tests for LR values at 30, 60 and 120 min with PRMC measurements in patients who did not cough during the PRMC investigation. This allowed us to analyse the impact of involuntary cough on PRMC.

Additional diagnostic testing

PCD genetics

A next-generation sequencing gene panel was used to analyse the PCD genes mentioned below. Gene names are given according to the latest updated gene nomenclature (Human Genome Organisation Gene Nomenclature Committee; https://www.genenames.org/). For the convenience of the reader, previous gene names are given in parenthesis: ODAD1 (CCDC114), ODAD2 (ARMC4), ODAD3 (CCDC151), DNAH5, DNAH9, DNAI1, DNAI2, DNAL1, CFAP298 (C21orf59), CCDC103, CCDC65, CCDC39, CCDC40, CCNO, DNAH11, DNAAF1 (LRRC50), DNAAF2 (KTU), DNAAF3 (C19orf151), DNAAF4 (DYX1C1), DNAAF6 (PIH1D3), DRC1 (CCDC164), GAS8, HYDIN, DNAAF11 (LRRC6), MCIDAS, OFD1, RSPH1, RSPH3, RSPH4A, RSPH9, SPAG1, ZMYND10 and FOXJ1.

nNO measurement

Triple nNO measurements (ppb) was performed using the CLD88sp stationary NO chemiluminescence analyser (ECO MEDICS AG, Duernten, Switzerland) according to recommended standards [18]. Nasal NO measurement sampling flow rate was 0.33 L·min−1. Conversion from nNO concentration to nNO production rate (nL·min−1) was determined by multiplying nNO (ppb) by flow rate (L·min−1).

HSVM and TEM

Ciliary beat pattern and frequency were determined from HSVM analysis of nasal brush biopsy material, and nasal ciliary ultrastructure by TEM as per ERS criteria for PCD diagnosis [17]. TEM material was obtained from a nasal scraping biopsy. There are no current consensus guidelines for performing HSVM for PCD diagnostics; thus, our laboratory adheres to standards given by Kempeneers et al. [19]. The normal ciliary beat frequency reference range was 8–11 Hz in our laboratory. TEM analyses were performed as standard diagnostic testing in all participants and according to ERS guidelines [20].

Statistical analysis

Nonparametric statistics were used to analyse the data due to the small sample size. Fisher's exact test was used to compare count data in tables, while the Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare three or more independent groups. Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare means of individual and independent groups.

All statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.2.0 (www.r-project.org). p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethics

Data collection was based on existing PCD registry data, for which written informed consent from all patients had already been obtained. Hence, supplemental ethical approval was not necessary for this study.

Results

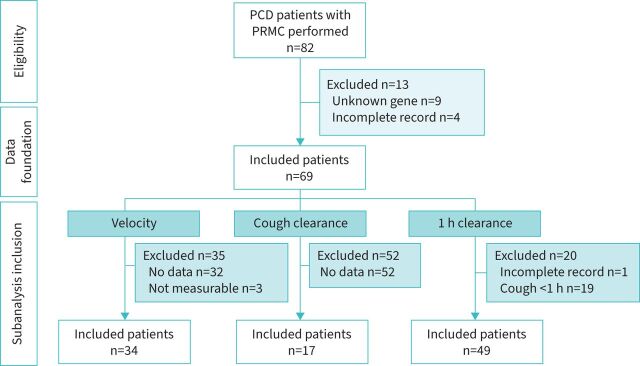

Out of the 82 patients in our Danish PCD cohort who had undergone a previous PRMC test, we included 69 with verified biallelic PCD mutations. Patient characteristics are given in table 1 and the flow diagram for inclusion and exclusion in figure 1. We were able to include 49 of these 69 patients (71%) for PRMC LR1 assessments and 34 out of 69 (49%) for dynamic PRMC TBV assessments. Only 17 patients had a record for controlled cough assessment and could be included for voluntary cough clearance investigation.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of non-PCD controls and patients with PCD included in the overall study and each sub-study based on outcome parameter

| Characteristics | Non-PCD controls | Patients with PCD | |||

| Overall | LR1 | TBV | Voluntary controlled cough clearance | ||

| Participants (n) | 6 | 69 | 49 | 34 | 17 |

| Age (years) | 23 (18–27) | 15 (11–28) | 14 (11–20) | 13 (9–19) | 10 (9–20) |

| Male sex | 2 (33) | 31 (45) | 24 (49) | 12 (35) | 4 (24) |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | IRR | 10 (5–18) | 9 (4–17) | 8 (5–17) | 7 (5–13) |

| Situs inversus | 0 | 25 (36) | 15 (31) | 12 (34) | 8 (47) |

| nNO (ppb) | 475 (453–497) | 44 (26–80) | 51 (28–86) | 38 (26–82) | 34 (26–54) |

Data presented as median (IQR) or n (%), unless otherwise indicated. PCD: primary ciliary dyskinesia; LR1: l-h lung retention; TBV: tracheobronchial velocity; IRR: irrelevant; nNO: nasal nitric oxide.

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of patient inclusion. PCD: primary ciliary dyskinesia; PRMC: pulmonary radioaerosol mucociliary clearance.

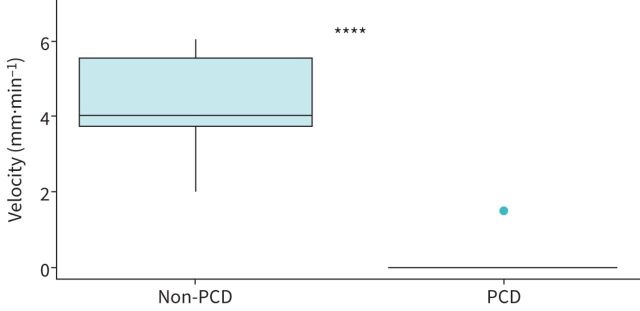

Six non-PCD controls provided PRMC TBV values for comparison (table 1, figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Comparison of pulmonary radioaerosol mucociliary clearance velocity between included patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) (n=34) and non-PCD controls (n=6). ****: p<0.00001.

Our previous publication on PRMC in PCD from 2007 [5] also included LR1 data. There was an overlap of 26 out of 49 patients (53%) with reported LR1 data in our previous study [5] and the LR1 data reported in the current cohort. Hence, nearly half of the LR1 data reported here are new. TBV data and cough clearance data are all new because these data have not been previously published.

PRMC measures and PCD genotype

We compared the five most common genotypes in our PCD cohort (CCDC39/CCDC40, DNAH11, DNAH5, DNAI1 and HYDIN), the TEM defects and the HSVM results and found no significant differences in either the LR1 values or retention z-scores (tables 2–4).

TABLE 2.

Pulmonary radioaerosol mucociliary clearance LR1 and association with genotypes

| Characteristic | CCDC39/CCDC40 | DNAH11 | DNAH5 | DNAI1 | HYDIN | Other | p-value |

| Participants (n) | 7 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 4 | 21 | |

| Age (years) | 11 (10–23) | 10 (8–17) | 15 (13–19) | 19 (15–31) | 16 (12–19) | 14 (11–20) | 0.5 |

| Male sex | 5 (71) | 3 (50) | 0 (0) | 5 (71) | 2 (50) | 9 (43) | 0.2 |

| PI | 0.52 (0.40–0.65) | 0.56 (0.45–0.67) | 0.63 (0.58–0.70) | 0.55 (0.42–0.73) | 0.42 (0.36–0.50) | 0.42 (0.34–0.57) | 0.4 |

| LR1 | 0.995 (0.992–1.000) | 0.996 (0.979–1.000) | 1.000 (0.996–1.000) | 1.000 (1.000–1.000) | 0.995 (0.979–1.000) | 0.990 (0.970–1.000) | 0.2 |

| Predicted LR1 | 0.84 (0.80–0.86) | 0.84 (0.81–0.87) | 0.85 (0.83–0.86) | 0.81 (0.80–0.89) | 0.80 (0.79–0.81) | 0.80 (0.78–0.84) | 0.5 |

| Z-score | 1.69 (1.46–2.23) | 1.66 (1.36–2.01) | 1.62 (1.53–1.73) | 2.11 (1.20–2.26) | 2.13 (1.84–2.28) | 1.93 (1.35–2.23) | 0.8 |

Data are presented as median (IQR) or n (%), unless otherwise indicated. p-values calculated by Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test or Pearson's Chi-squared test. PI: penetration index; LR1: 1-h lung retention.

TABLE 4.

Pulmonary radioaerosol mucociliary clearance LR1 and association with HSVM motility pattern

| Characteristic | Hyperkinetic/reduced proximal bending | Non-motile | Non-motile/residual flickering | Reduced number of cilia | Severely reduced amplitude/rigid axonemes | Slow rotational | Subtle abnormalities | p-value |

| Participants (n) | 6 | 6 | 14 | 2 | 8 | 5 | 8 | |

| Age (years) | 10 (8–17) | 12 (9–16) | 18 (15–28) | 11 (10–13) | 14 (10–33) | 12 (10–14) | 15 (13–19) | 0.2 |

| Male sex | 3 (50) | 2 (33) | 6 (43) | 1 (50) | 5 (62) | 2 (40) | 5 (62) | >0.9 |

| PI | 0.56 (0.45–0.67) | 0.35 (0.34–0.41) | 0.53 (0.41–0.71) | 0.27 (0.19–0.34) | 0.48 (0.42–0.62) | 0.50 (0.43–0.68) | 0.51 (0.36–0.59) | 0.5 |

| LR1 | 0.996 (0.979–1.000) | 0.990 (0.975–0.997) | 1.000 (0.999–1.000) | 0.944 (0.927–0.960) | 0.994 (0.988–1.000) | 0.995 (0.987–1.000) | 0.995 (0.965–1.000) | 0.088 |

| Predicted retention | 0.84 (0.81–0.87) | 0.79 (0.78–0.81) | 0.81 (0.80–0.87) | 0.76 (0.74–0.78) | 0.83 (0.78–0.86) | 0.83 (0.80–0.86) | 0.82 (0.79–0.84) | 0.7 |

| Z-score | 1.66 (1.36–2.01) | 2.11 (1.91–2.22) | 2.06 (1.39–2.24) | 2.01 (1.95–2.07) | 1.82 (1.49–2.13) | 1.87 (1.39–2.25) | 1.63 (0.92–2.06) | 0.9 |

Data are presented as median (IQR) or n (%), unless otherwise indicated. p-values calculated by Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test or Pearson's Chi-squared test. LR1: 1-h lung retention; HSVM: high-speed video microscopy, PI: penetration index.

TABLE 3.

Pulmonary radioaerosol mucociliary clearance LR1 and association with transmission electron microscopy ultrastructure

| Characteristic | BB mislocated | CC defect | No abnormalities detected |

ODA

defect |

ODA+IDA

defect |

Tubular disorganisation+IDA defect | p-value |

| Participants (n) | 2 | 6 | 12 | 16 | 5 | 8 | |

| Age (years) | 11 (10–13) | 13 (11–20) | 13 (10–19) | 18 (15–29) | 11 (9–13) | 14 (10–33) | 0.12 |

| Male sex | 1 (50) | 3 (50) | 7 (58) | 6 (38) | 2 (40) | 5 (62) | 0.9 |

| PI | 0.27 (0.19–0.34) | 0.51 (0.45–0.64) | 0.52 (0.43–0.68) | 0.52 (0.39–0.69) | 0.35 (0.34–0.41) | 0.48 (0.42–0.62) | 0.4 |

| LR1 | 0.944 (0.927–0.960) | 0.998 (0.989–1.000) | 0.996 (0.974–1.000) | 1.000 (0.997–1.000) | 0.989 (0.970–0.999) | 0.994 (0.988–1.000) | 0.2 |

| Predicted LR1 | 0.76 (0.74–0.78) | 0.83 (0.81–0.85) | 0.82 (0.81–0.87) | 0.81 (0.79–0.87) | 0.79 (0.78–0.81) | 0.83 (0.78–0.86) | 0.6 |

| Z-score | 2.01 (1.95–2.07) | 1.89 (1.51–2.16) | 1.66 (1.28–2.08) | 2.01 (1.28–2.23) | 2.11 (1.91–2.22) | 1.82 (1.49–2.13) | >0.9 |

Data are presented as median (IQR) or n (%), unless otherwise indicated. p-values calculated by Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test or Pearson's Chi-squared test. LR1: 1-h lung retention; BB: basal body; CC: central complex; ODA: outer dynein arm; IDA: inner dynein arm; PI: penetration index.

Subgroup analyses of PRMC values across TEM and HSVM groups also revealed no significant differences.

The complete list of included and excluded patients according to genotypes, HSVM ciliary motility patterns and TEM ultrastructure is provided in the supplementary material.

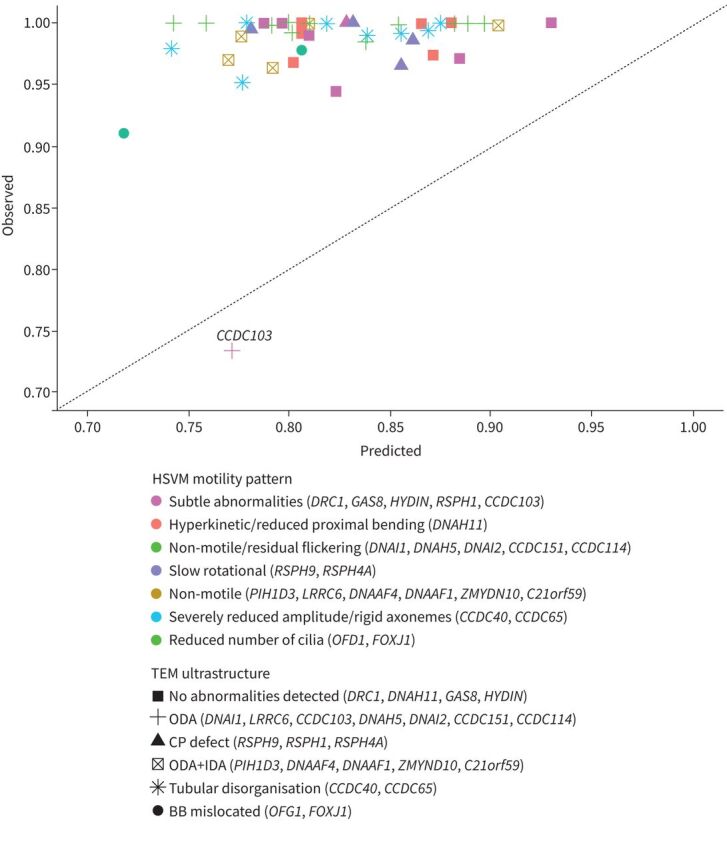

Of the 34 patients included for dynamic PRMC assessment, all but one patient (33 out of 34) had abnormal LR1 (91–100% retention) and no measurable velocity, i.e. 0 mm·min−1. Only one patient exhibited normal LR1 (73% retention) and a measurable TBV of 1.5 mm·min−1 (figure 2). TBV was significantly lower compared to the non-PCD referrals in the control group with a median TBV of 4.0 mm·min−1 (range 2.0–6.0 mm·min−1, p<0.00001; figure 3).

FIGURE 2.

1-h lung retention and indirect genotype measures. HSVM: high-speed video microscopy; TEM: transmission electron microscopy; ODA: outer dynein arm; CP: central pair; IDA: inner dynein arm; BB: basal body.

The patient with normal LR1 had a homozygous p.His154Pro CCDC103 defect, normal nNO levels of 968 ppb (319 nL·min−1), residual (subtle abnormal) ciliary beating with a low-to-normal ciliary beat frequency of 3.5–8.9 Hz on HSVM, and a moderate outer dynein arm (ODA) deficiency (TEM cross sections counted n=119, deficient ODAs found in 56 out of 119 (47%), no inner dynein arm (IDA) or microtubule deficiency was detected).

PRMC voluntary cough clearance

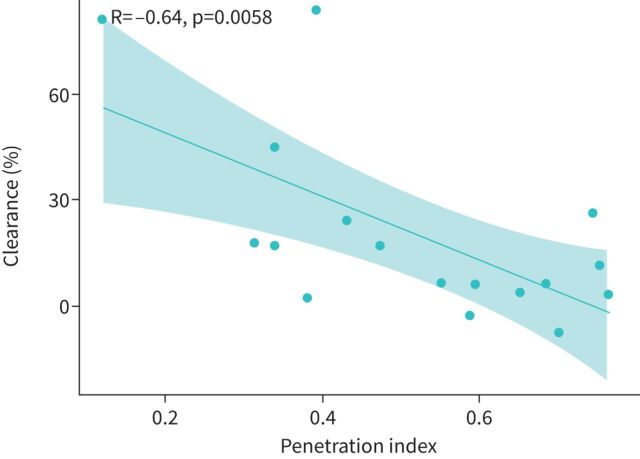

Voluntary controlled cough clearance from the central parts of the lungs was a median of 11% (IQR 4–24%) in 17 patients with PCD. We found a statistically significant moderate negative linear correlation between voluntary cough clearance and the PI, indicating that peripherally deposited aerosol (high PI value) is less easily coughed up from the main bronchi and the trachea than a centrally deposited aerosol (low PI value) (figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Correlation between voluntary cough clearance and aerosol deposition.

Impact on involuntary cough clearance and peripheral aerosol deposition on PRMC results

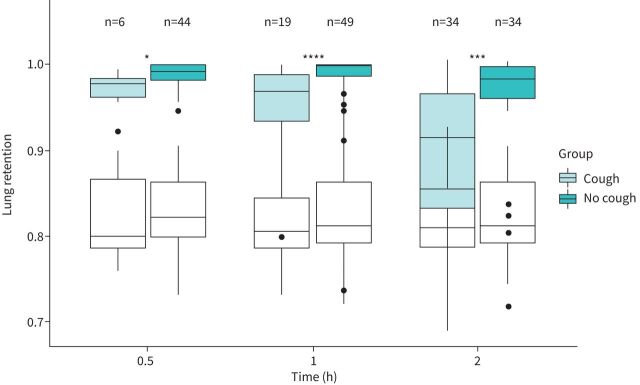

The majority of excluded LR1 data (19 out of 20) were caused by cough within the first 1 h (figures 1 and 5).

FIGURE 5.

Boxplots of retention measurements for the included patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia stratified by records of cough. The clear boxes represent expected lung retention values calculated from reference equations (the reference equations are given in the supplementary material). *: p<0.05; ***: p<0.001; ****: p<0.0001.

Overall, involuntary cough resulted in significant differences in LR at all timepoints, indicating false-positive MC that accumulated over time from 30 min to 120 min after inhalation of the radioaerosol (figure 5). LR at 30-min was 99.2% (98.1–100%) in the no cough group (n=44) versus 97.6% (96.2–98.3%) in the cough group (n=6) (p=0.02544). LR at 60-min (LR1) was 99.9% (98.6–100%) in the no cough group (n=49) versus 96.8% (93.5–98.8%) in the cough group (n=19) (p<0.0001). LR at 120-min was 98.2% (96–99.6%) in the no cough group (n=34) versus 91.4% (83.2–96.5%) in the cough group (n=34) (p=0.0006).

The differences in LR between groups (no cough versus cough) could not be explained by differences in PIs because they were similar between groups at all timepoints (at 30 min: p=0.7653; at 60 min: p=0.9778; at 120 min: p=0.8952).

The excluded TBV measurements (n=35) were caused by peripheral deposition in two out of 35 cases, as indicated by no visible tracer in the central airways at the time for the dynamic TBV assessments and by involuntary cough in one out of 35 cases. In 32 out of 35 cases, where PRMC measurements had been performed in the first period of the 24 years of data collection, no digital films were available to re-read because only the paper files existed.

Discussion

Overall, our study showed that PRMC was extremely low or unmeasurable in all parameters regardless of PCD genotype, TEM ultrastructure and ciliary motility patterns. These findings are consistent with recently published data on nasal MC, which similarly demonstrated complete absence of clearance across various PCD genotypes [21]. This is interesting given that previous studies have shown that certain PCD genes can be associated with either more severe or less pronounced clinical symptoms. Patients with CCDC39/40 defects, which are associated with ciliary ultrastructural microtubular disorganisation combined with IDA deficiency, tend to have poorer lung function outcomes and more severe high-resolution computed tomography abnormalities [14, 15, 22]. Conversely, patients with DNAH11 defects, which are associated with normal ciliary ultrastructure [23], may have milder respiratory symptoms [14], higher forced respiratory volume in 1 s z-scores and fewer neonatal respiratory symptoms [24]. Even though TEM is normal in patients with the DNAH11 defect, the ciliary motility pattern is markedly compromised in these patients, given that HSVM is characterised by stiff hyperkinetic and minimal movement [4, 16].

In this study, we found no indications that PRMC differed between groups of genotypes where PCD would be expected to be related to either more severe or more mild disease. In line with this, previous investigations by Vali et al. [9] have demonstrated that PRMC results are not associated with lung function.

One case was an exception. This patient was the only one to show normal LR1 values and measurable, although low, TBV and had a homozygous p.His154Pro CCDC103 defect, subtle ciliary motility pattern abnormalities, a normal nNO and only a moderate ODA deficiency. This particular defect has previously been associated with reduced-to-normal ciliary beating as well as normal range nNO [25]. Even though it was only a single case and the result should be interpreted cautiously, this finding illustrates that the PRMC method may be able to reflect even smaller variations in ciliary beating within PCD, which potentially could extrapolate to detectable improvement in PRMC as an outcome if ciliary function could be restored in patients with PCD.

PRMC cough clearance

This study provides novel insights into the impact of cough on pulmonary clearance in patients with PCD. Involuntary cough, which is challenging to suppress for patients with PCD, had a notable impact on PRMC, resulting in significant MC at all measured timepoints. Similarly, voluntary cough resulted in increased PRMC with a median 11% reduction in LR1.

With that, this study underscores that cough clearance plays a crucial role in PRMC measurements, because coughing during the test can significantly increase PRMC values and lead to false near-normal results. Additionally, our findings suggest that regular controlled coughing may significantly optimise airway clearance in patients with PCD.

Strengths and limitations

Our study offers new insights into the potential use of the PRMC test as a source of outcome parameters for clinical trials. It is known that PRMC test results can significantly differentiate between individuals with PCD and healthy individuals [5, 7–9] while still retaining diagnostic capability even with a shortened 60-min test [9]. However, the relationship between PRMC test results and specific PCD genotypes has not been previously described. In our study, we demonstrated the absence of PRMC across various genotypes in PCD. Although the evidence is limited because it is based on a single patient, our findings suggest that residual ciliary function in PCD could lead to measurable PRMC, providing support for the use of PRMC testing as a valuable outcome parameter for detecting improvements in medically enhanced ciliary function.

Furthermore, the PRMC test can be conducted with relative speed and efficiency, given that a complete measurement can be completed within a 2-h timeframe. This convenience enables the inclusion of patients from a wide hospital service area. Moreover, PRMC testing holds promise for studies involving younger children because even children as young as 5 years old can actively participate and cooperate in PRMC measurements [5].

Data were collected retrospectively from our local PCD registry spanning 24 years. Despite the lengthy period of data collection, our study was limited by small groups.

During the 24 years, many cases of PCD were diagnosed using HSVM, TEM and nNO measurements, along with more recent genetic work-up, without the inclusion of a supplementary PRMC test. This limited the overall number of included patients.

In our pursuit of identifying PRMC variations among different PCD genotypes, we implemented rigorous data cleaning and, in this process, excluded numerous recordings to maintain analysis integrity and mitigate the impact of cough. However, given the challenge of suppressing cough in these patients, we acknowledge that our data-cleaning approach may have been overly stringent, which also explains low success rates for including LR1 data (71%) and TBV data (41%).

There are several challenges to consider concerning the use of PRMC in clinical trials, including radiation exposure, age restrictions, involuntary cough and the potential impact on peripheral deposition.

The inhaled amount of radioaerosol is the same for all individuals while the retention and thus radiation exposure differs. The half time of 99mTc is 6 h, rendering radioactivity after 24 h <7% owing to physical decay. Because of the additional biological clearance, which is slower in patients with abnormal MC, residual activity is even lower than 7% in both healthy and diseased people. The effective exposure is 0.2–0.5 mSv per PRMC test, slightly higher in diseased patients than in healthy subjects, and will therefore always be lower than 1 mSv as stated, irrespective of a normal or abnormal PRMC where there still may be visible retention after 24 h.

Although the radiation exposure associated with a PRMC measurement is low, it is still important to take into consideration, especially if multiple measurements are planned, e.g. before, during and at the end of a clinical trial. Yet, even with three consecutive studies performed in a patient, the radiation exposure is lower than the yearly background radiation in Denmark of 4 mSv.

The successful execution of PRMC testing relies on the close cooperation of patients, who need to perform controlled radioaerosol inhalation and lie still for a minimum of 20 min during the scintigraphy phase of the test. These requirements make PRMC unsuitable for children aged <5 years [5]. Furthermore, age has been found to influence PRMC LR in healthy individuals, with children exhibiting faster MC. Currently, there are no established normal reference values for PRMC LR or TBV specific to different age groups [7]. However, in a clinical trial using PRMC for outcome parameters, such as baseline measurements at inclusion, during a trial and at the end of trial, the patients would serve as their own controls. This approach would minimise the impact of age-related differences on the interpretation of the results.

In this study we demonstrated a significant impact of cough and peripheral radioaerosol deposition on PRMC outcomes, the latter in alignment with previous published data on PI impact on LR values [10]. Uncontrolled cough should be avoided to prevent possible false-positive PRMC outcomes. Minimising peripheral deposition should be attempted to avoid false-negative PRMC measures because peripherally deposited aerosol is less easily cleared than centrally deposited aerosol. Additionally, too peripheral radioaerosol deposition makes TBV evaluation difficult because the tracer never reaches the central airways within the time for assessment.

If repeated PRMC measurements are planned during a clinical trial, it will be crucial to target consistent PI values in the patients throughout the trial period. Deposition of the inhaled radioaerosol is predominantly influenced by aerosol particle size, inhalation pattern and the extent of airway obstruction. While the particle size remains constant and the inhalation pattern can be controlled, the final aerosol deposition and resulting PI are primarily determined by the degree of airway obstruction. Because patients with PCD often exhibit heterogeneous and variable peripheral obstruction, this poses an important limitation that requires attention.

To address these limitations, it is worth considering strategies aimed at reducing bronchial obstruction and tendency to cough where PRMC would be used as outcome parameter.

Conclusion

Most patients with PCD demonstrated a complete absence of PRMC, and no significant differences in PRMC were observed among different PCD genotypes. However, our study suggests that PRMC parameters have the potential to improve with partial restoration of ciliary function.

Controlled coughing was found to enhance MC and could be beneficial for airway clearance in patients with PCD. The PRMC test, completed within a convenient 2-h timeframe, allows for the inclusion of patients from a wide range of hospital service areas.

Overall, our results suggest that, after careful adjustment for pitfalls, PRMC measurements could potentially provide valuable outcome parameters for future clinical trials aimed at restoring ciliary motility and increasing MC. The main methodological challenges to address would be involuntary coughing and peripheral radioaerosol deposition.

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material 00685-2023.supplement2 (88.7KB, pdf)

Appendix 1 00685-2023.supplement1 (184.9KB, pdf)

Acknowledgement

Many thanks to the staff at the Department of Clinical Physiology and Nuclear Medicine at Rigshospitalet for their skilful help in performing the pulmonary radioaerosol mucociliary studies throughout the many years.

Provenance: Submitted article, peer reviewed.

Author contributions: J.K. Marthin, M.G. Holgersen, K.G. Nielsen and J. Mortensen all meet the four International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria for authorship. This manuscript has been seen and approved by all listed authors.

Conflict of interest: J.K. Marthin, M.G. Holgersen, K.G. Nielsen and J. Mortensen have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Lucas JS, Davis SD, Omran H, et al. Primary ciliary dyskinesia in the genomics age. Lancet Respir Med 2020; 8: 202–216. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30374-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horani A, Ferkol TW. Understanding primary ciliary dyskinesia and other ciliopathies. J Pediatr 2021; 230: 15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.11.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raidt J, Maitre B, Pennekamp P, et al. The disease-specific clinical trial network for primary ciliary dyskinesia: PCD-CTN. ERJ Open Res 2022; 8: 00139-2022. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00139-2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallmeier J, Nielsen KG, Kuehni CE, et al. Motile ciliopathies. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2020; 6: 77. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-0209-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marthin JK, Mortensen J, Pressler T, et al. Pulmonary radioaerosol mucociliary clearance in diagnosis of primary ciliary dyskinesia. Chest 2007; 132: 966–976. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marthin JK. Nasal nitric oxide and pulmonary radioaerosol mucociliary clearance as supplementary tools in diagnosis of primary ciliary dyskinesia. Dan Med Bull 2010; 57: B4174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Munkholm M, Nielsen KG, Mortensen J. Clinical value of measurement of pulmonary radioaerosol mucociliary clearance in the work up of primary ciliary dyskinesia. EJNMMI Res 2015; 5: 118. doi: 10.1186/s13550-015-0118-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walker WT, Young A, Bennett M, et al. Pulmonary radioaerosol mucociliary clearance in primary ciliary dyskinesia. Eur Respir J 2014; 44: 533–535. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00011814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vali R, Ghandourah H, Charron M, et al. Evaluation of the pulmonary radioaerosol mucociliary clearance scan as an adjunctive test for the diagnosis of primary ciliary dyskinesia in children. Pediatr Pulmonol 2019; 54: 2021–2027. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mortensen J, Lange P, Nyboe J, et al. Lung mucociliary clearance. Eur J Nucl Med 1994; 21: 953–961. doi: 10.1007/BF00238119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donaldson SH, Laube BL, Corcoran TE, et al. Effect of ivacaftor on mucociliary clearance and clinical outcomes in cystic fibrosis patients with G551d-Cftr. JCI Insight 2018; 3: e122695. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.122695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donaldson SH, Laube BL, Mogayzel P, et al. Effect of lumacaftor-ivacaftor on mucociliary clearance and clinical outcomes in cystic fibrosis: results from the PROSPECT MCC sub-study. J Cyst Fibros 2022; 21: 143–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2021.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marthin JK, Petersen N, Skovgaard LT, et al. Lung function in patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia: a cross-sectional and 3-decade longitudinal study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010; 181: 1262–1268. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200811-1731OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis SD, Rosenfeld M, Lee HS, et al. Primary ciliary dyskinesia: longitudinal study of lung disease by ultrastructure defect and genotype. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019; 199: 190–198. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201803-0548OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pifferi M, Bush A, Mulé G, et al. Longitudinal lung volume changes by ultrastructure and genotype in primary ciliary dyskinesia. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2021; 18: 963–970. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202007-816OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brennan SK, Ferkol TW, Davis SD. Emerging genotype–phenotype relationships in primary ciliary dyskinesia. Int J Mol Sci 2021; 22: 8272. doi: 10.3390/ijms22158272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lucas J, Barbato A, Collins SA, et al. European Respiratory Society guidelines for the diagnosis of primary ciliary dyskinesia. Eur Respir J 2017; 49: 1601090. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01090-2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beydon N, Kouis P, Marthin JK, et al. Nasal nitric oxide measurement in children for the diagnosis of primary ciliary dyskinesia: European Respiratory Society technical standard. Eur Respir J 2023; 61: 2202031. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02031-2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kempeneers C, Seaton C, Espinosa BG, et al. Ciliary functional analysis: beating a path towards standardization. Pediatr Pulmonol 2019; 54: 1627–1638. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shoemark A, Boon M, Brochhausen C, et al. International consensus guideline for reporting transmission electron microscopy results in the diagnosis of primary ciliary dyskinesia (beat PCD TEM criteria). Eur Respir J 2020; 55: 1900725. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00725-2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marthin JK, Nielsen KG, Mortensen J. Quantitative 99mTc-albumin colloid nasal mucociliary clearance as outcome in primary ciliary dyskinesia. ERJ Open Res 2023; 9: 00345-2023. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00345-2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kinghorn B, Rosenfeld M, Sullivan E, et al. Genetic airway disease in children with primary ciliary dyskinesia: impact of ciliary ultrastructure defect and genotype. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2023; 20: 539–547. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202206-524OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knowles MR, Leigh MW, Carson JL, et al. Genetic mutations of DNAH11 in patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia with normal ciliary ultrastructure. Thorax 2012; 67: 433–441. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shoemark A, Rubbo B, Legendre M, et al. Topological data analysis reveals genotype–phenotype relationships in primary ciliary dyskinesia. Eur Respir J 2021; 58: 2002359. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02359-2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shoemark A, Moya E, Hirst RA, et al. High prevalence of CCDC103 P.his154pro mutation causing primary ciliary dyskinesia disrupts protein oligomerisation and is associated with normal diagnostic investigations. Thorax 2018; 73: 157–166. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-209999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material 00685-2023.supplement2 (88.7KB, pdf)

Appendix 1 00685-2023.supplement1 (184.9KB, pdf)