Abstract

Soil microorganisms are indispensable for a healthy soil environment, where the fate of pesticides is contingent on microbial activity. Conversely, soil ecosystems can be distorted by all kinds of variables, such as agrochemicals. These crop protection products have been universally in use for decades in agriculture.

In modern crop cultivation, fungicides are increasingly applied because of their high and broad effectivity on plant pathogens. While their use can enhance harvest yields, fungicides, particularly broad-spectrum ones, are responsible for the alteration of the soil microflora. Furthermore, successive and combined application of pesticides is an agronomic routine, which aggravates the concurrent existence of synthetic chemicals in the soil and marine environments. Mutual interactions of such different molecules, or their effects on soil life, can negatively impact the dissipation of biodegradable pesticides from the ecosystems. The direct effects of individual agrochemicals on microbial soil parameters, as well as agronomic efficiency and interactions of mixtures have been thoroughly studied over the past 80 years. The indirect impacts of mixtures on soil and aquatic ecosystems, however, may be overlooked. Moreover, the current regulatory risk assessment of agrochemicals is based on fate investigations of individual substances to derive predicted environmental concentrations, which does not reflect real agricultural scenarios and needs to be updated.

In this article, we summarized the results from our own experiments and previous studies, demonstrating that the degradation of pesticides is impacted by the co-existence of fungicides by their effects on microbial and enzymatic activities in soil.

Keywords: Pesticides, Mixtures, Soil, Biomass, Degradation, Half-life

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Pesticide mixtures are typical for the agricultural practice and residues may accumulate in soil.

-

•

Fungicides can enhance crop yields, but they affect the soil microflora.

-

•

Fungicides can adversely impact the biodegradation of herbicides in soil.

-

•

Regulatory environmental risk assessment should consider pesticide mixtures.

1. Introduction

Synthetic chemicals of environmental relevance are now found in many places on Earth, some of which are distributed worldwide and far away from the respective emission sources. Important pathways for contamination of our water and soil ecosystems include emissions from industry, farms, sewage treatment plants, and in the case of pharmaceuticals, outflows from households and clinics. Chemical pollution plays a role in the concept of planetary boundaries, suggesting that crossing critical thresholds can lead to disturbances in environmental processes [[1], [2], [3]].

For the environmental risk assessment of chemicals, both their fate and impact on organisms and ecosystem services must be studied. In this article, we will focus on the fate, more specifically the degradation, of pesticides, an important group of chemicals because of their permanent and extensive use in conventional agriculture, and their impact on ecosystems. It should be noted that conclusions drawn in this article will also be subject to other chemical use classes. Chemical pesticides are used to protect crops and plant products from harmful organisms and the diseases they cause. They contain one or more chemicals that are most often synthetically manufactured active substances, although pesticides from biological sources are also in use. Pesticides combat organisms that harm crops, for example, insects or rodents, offer protection from diseases such as fungal infections, thus simplifying agricultural production of food and feed. Pesticides also include herbicides which are used to control weeds. Other applications include plant growth regulation and the conservation of plant products.

If pesticides are used correctly, there should be no harmful effects on human and animal health or any unjustifiable effects on the environment. Only the target species should be harmed. To achieve that, the environmental impact of pesticides is assessed in a tiered process ranging from laboratory tests with standard organisms to more complex studies in mesocosms or fields under real environmental conditions and organism communities. The principle of the risk assessment is to compare the expected concentration of a pesticide in the environment (PEC—predicted environmental concentration) with concentrations below which no adverse effects on non-target organisms have been observed (NOEC—no observed effect concentration). In general, the more realistic the test, the lower the uncertainty factor to be applied for the environmental risk assessment of a chemical.

Diverse research groups have frequently demonstrated that the present use of pesticides has a significant adverse impact on ecosystems and biodiversity. Herbicides reduce the diversity and abundance of flowering plants and weeds on arable land and the surroundings. This loss of food resources and habitat is a major reason for the loss of the biodiversity of insects, not only in biotopes in the field boundaries [[4], [5], [6]] but throughout the entire agricultural landscape. The vast reduction in biomass, habitat structures, and food resources does not only affect insects but also their predators such as small mammals and birds [[7], [8], [9], [10], [11]]. The worldwide invertebrate population and the number of species have declined dramatically due to the use of pesticides, though other causes such as habitat loss also play a role.

Empirical data for the exposure assessment, that is, from metabolic pathways and degradation rates of pesticides in soil and water, are collected in studies with individual substances. In the agricultural reality, however, the presence of multiple pesticide residues in soil and water is widespread. Ciaia et al. [12] investigated the presence of 80 polar pesticides and corresponding transformation products in topsoil samples from the Swiss Soil Monitoring Network from 1995 to 2008 with known pesticide application patterns. At most sites, 10–15 pesticides were identified with concentrations between 1 and 330 μg/kg (soil dry weight). Metabolites were detected in almost half of the sites where the parent compound was applied. Residues of about 80% of all applied pesticides could be detected, with half of these found as metabolites that persisted for more than ten years. Similarly, Riedo et al. [13] investigated 100 agricultural fields under organic and conventional management screening for 46 target pesticides. Pesticides were detected in each site, including organic fields where only half the number of residues and a one-ninth concentration were detected compared with that in conventional fields. Even 20 years after the change from conventional to organic agriculture at the investigated sites, up to 16 different pesticide residues were still present. Silva et al. [14] focused on the analysis of 76 target pesticides in more than 300 agricultural fields across the European Union. Almost 60% of the soils contained mixtures of two or more pesticide residues in various combinations.

These studies have revealed that the presence of mixtures of pesticide residues in agricultural soils is the rule rather than the exception. There are several reasons for this. First, pesticides are often applied as tank mixtures, individually prepared by the farmer depending on the infection pressure of the crop. Second, repeated pesticide applications, so called spray series, during the season have become standard, with fruit cultivation sites leading the way, often with up to 20 rounds or more per year [15]. Third, the binding of the chemicals to the soil matrix leads to a reduced bioavailability and thus a significantly retarded degradation, resulting in the accumulation of residues.

The impact of such mixtures on soil biota has been assessed: simulation of a real pesticide spray series indicated that the threshold value defined in the risk assessment for certain organisms can be exceeded, as shown in Sybertz et al. [16] for earthworms. In the study, modeling considered both the frequency of pesticide applications and the different degradation behavior of the individual substances applied [16]. Likewise, in aquatic ecosystems, pesticide mixtures and the resulting body burden of organisms can cause a high toxic pressure [17].

Ecosystems are stressed by the input of pesticides [18], other chemical pollutants [19], and non-chemical stressors like soil compaction and natural disturbance like drought. In this article, we focused on the degradation of pesticides in soil and its dependence on the presence of further pesticide residues. We compared the fate of individual substances, the standard scenario in regulatory pesticide studies, with the fate of the substance when present in mixtures. Only a few studies on this aspect are available, which will be discussed below, including our own experiments on the impact of fungicides on the degradation of herbicides. Fungicides are often used for effective crop protection. Due to their inhibitory capabilities, they play a dominant role in the alteration of the soil fungi and microflora and, therefore, the degradation potential of soils.

2. Methods

Studies to investigate the dependence of degradation rates of pesticides on the presence of other interfering substances can be designed according to guidelines such as OECD or U.S. EPA [20,21]. Soil samples are filled into all-glass flasks that allow trapping volatile metabolites including carbon dioxide and are incubated at defined moisture conditions and temperature. Test substances are applied to the soil and flasks are sampled at defined time intervals at which soil is extracted with organic solvents. If radioactively labeled chemicals are used, it is possible to establish a mass balance and recovery, comprising volatile, extractable, and non-extractable residues, the latter being determined by combustion and trapping of the evolved labeled carbon dioxide. In our experiment, application was divided into controls, that is, soil incubated with the test substance alone, and those with additionally added fungicides as interfering agents. Co-application can be simultaneous, mimicking the application as a tank mixture, or subsequent corresponding to the agricultural practice in the form of spray series.

2.1. General and soil information

We investigated the fate of the herbicide [14C]-iodosulfuron-methyl-sodium in a loamy sand soil (Table 1), either applied alone or together with the fungicides tebuconazole and prothioconazole. The choice was based on the fact that the prevalent group of antifungal chemicals are conazole fungicides, comprising triazoles and imidazoles. Residues of this group of substances are often detected in arable soils [22,23]. The mechanism of action of conazole fungicides is based on the inhibition of ergosterol biosynthesis [24,25]. Tebuconazole and prothioconazole disrupt growth and sterol biosynthesis of various plant pathogenic fungi such as ascomycetes, basidiomycetes, and deuteromycetes, for example, Botrytis cinerea and Pyrenophora teres, by inhibiting sterol 14α-demethylase cytochrome P450 (CYP51), which is responsible for the morphology and functionality of the fungal cell membrane. The 14α-demethylated products represent intermediates in the pathways leading to the formation of ergosterol in fungi [24,25].

Table 1.

Soil characteristics.

| Parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| Texture (USDA) | Loamy sand |

| Particle size analyses: | |

| Clay (<0.002 mm, %) | 4.1 |

| Silt (0.002–0.05 mm, %) | 9.3 |

| Sand (>0.05 mm, %) | 86.6 |

| Water holding capacity: | |

| at pF 2 (g water/100 g soil) | 7.3 |

| pH (0.01 M CaCl2) | 4.7 |

| Organic carbon (%) | 0.6 |

| Cation exchange capacity (mmol/100 g soil) | 3.7 |

| Biomass (mg Corg/100 g soil) | 11.6 |

Both active ingredients can be applied in combination with other pesticides, for instance, the sulfonylurea post-emergence herbicide iodosulfuron-methyl-sodium [26].

2.2. Sample preparation

The soil was stored at about 4 °C in the dark upon usage, following biomass determination by the substrate-induced respiration method [27]. Individual soil samples consisting of 100 g of dry-weight soil are contained in 1-L all-glass flasks, with an inner diameter of about 10.6 cm. The soil moisture content was adjusted to pF 2 (gravimetrically by adding purified water, if needed) prior to acclimatization in the dark for one week in an environmental chamber at a controlled temperature of 20 ± 2 °C. The test vessels were constantly aerated with moist air.

2.3. Test substances

The herbicide iodosulfuron-methyl-sodium (Izotop, Budapest, Hungary) was 14C-uniform-labeled in the phenyl moiety of the molecule at a specific activity of 4.359 MBq/mg. The radiochemical purity was determined to be above 95% by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC-UV/RAM) prior to and post applications. The unlabeled fungicides tebuconazole and prothioconazole (Sigma Aldrich, Buchs, Switzerland) had a chemical purity of 99.3% and 99.9%, respectively.

2.4. Application

Each test vessel containing 100 g of dry-weight soil was individually treated with 13 μg of [14C]-iodosulfuron-methyl-sodium, corresponding to a tenfold exaggerated target rate of 0.100 kg/ha [28], assuming an even distribution of the chemical in the top 5 cm soil layer and a soil bulk density of 1.5 g/cm3, to ensure higher analytical reliability. This dose rate did not affect the degradation velocity of iodosulfuron-methyl-sodium in the tested soil types as shown in preliminary tests using the recommended dose (data not shown). One set of triplicate individual test vessels per interval was treated with the radiolabeled herbicide only (controls) and one set of triplicate individual test vessels per interval was subjected to fungicidal applications simulating agricultural field practice of combined treatments. These fungicidal applications represented three sequential treatments per respective soil samples (100 g); each was with unlabeled fungicides tebuconazole (67 μg/100 g or 0.500 kg/ha [29]) and prothioconazole (27 μg/100 g or 0.200 kg/ha [30,31]), dissolved in acetonitrile/acetone (1/1; v/v), and at recommended field rates. The first fungicidal treatment was performed at the end of the one-week acclimation period. Fungicides were applied 14 days prior to, then on the same day as, and again 5 days after the application of the herbicide. This application pattern simulated a typical spray series in agricultural fields. The control soil samples received an equivalent amount of organic solvent (0.3 mL of acetonitrile/acetone [1/1; v/v]) at each fungicide treatment interval. After dosing the soil surface, the treated soils were mixed thoroughly to allow the organic solvent to evaporate, and the soil moisture content was adjusted to pF 2. The total amount of organic solvent added to each soil sample throughout the complete application procedure was 1.0 mL per 100 g of dry-weight soil, corresponding to 1.0% (v/w) and in accordance with regulatory guidelines [32,33].

2.5. Incubation

Each test vessel was equipped with an inlet and outlet for gases and was maintained under aerobic conditions by constant aeration with moist air. The exhaust air was passed through an individual trapping system per sample equipped with two absorption traps containing ethylene glycol and 2N NaOH (in this sequence), allowing trapping organic volatiles and 14CO2, respectively. The soil samples were incubated for up to 77 days after treatment with the radiolabeled herbicide at a controlled temperature of 20 ± 2 °C in the dark. The soil moisture content was monitored weekly and adjusted to pF 2 if needed.

2.6. Work-up

At eight different timepoints, triplicate test vessels were harvested, and respective soils were extracted four times with acetonitrile/water (4/1; v/v) until less than 5% of applied radioactivity (AR) could be extracted in a single extraction step. Subsequently, if less than 90% AR was extracted by the acetonitrile/water (4/1; v/v) extractions, soils were additionally extracted with different solvents of decreasing polarity respectively, following the order of acetone, ethyl acetate, and hexane. The recovery of each extraction step was determined by duplicate liquid scintillation counting (LSC) measurements. Since less than 5% AR was recovered by the less polar extracts, these samples were not further processed. For each sample, the acetonitrile/water (4/1; v/v) soil extracts were combined, and the resulting pool was measured by LSC for recovery; subsequently, an aliquot was concentrated under a gentle stream of nitrogen at about 35 °C. Procedural recoveries consistently were >90% AR. The residual radioactivity remaining in the soil after the extraction procedure was quantified by LSC after combusting the aliquots of the air-dried and homogenized soil. Additionally, radioactivity in the absorption traps containing ethylene glycol or 2N NaOH was determined by LSC.

2.7. Analysis

Concentrated soil extracts were subjected to HPLC-UV/RAM for the determination of iodosulfuron-methyl-sodium and potential degradation products by co-chromatography using authenticated reference standards. For selected samples, the chromatographic results obtained by HPLC were confirmed by high-performance thin-layer chromatography (HPTLC) analysis.

2.8. Evaluation

Data were processed using Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft® Office 365, USA), GraphPad Prism (version 8.0.2, GraphPad Software, USA), and R (version 3.0.0, USA). Outliers were identified by Grubbs’s test (α = 0.05). Raw data were tested for normality distribution with Shapiro-Wilk test (α = 0.05). Degradation kinetics evaluation for the datasets of iodosulfuron-methyl-sodium was performed by the computer-assisted kinetic evaluation (CAKE) software tool [34] using a step-wise approach according to the FOCUS guidance [35] on estimating persistence and degradation kinetics from Environmental Fate Studies. Three different kinetic models, that is, single first-order (SFO), first-order multi-compartment (FOMC), and double first-order in parallel (DFOP), were fitted to the degradation data, respectively. Endpoints were found by an iterative procedure, which was implemented in the CAKE software [34], and used for the calculations.

3. Results

3.1. Our experiment

The distribution of radioactivity during incubation is shown in Fig. 1, confirming that reasonable recoveries have been obtained (controls: 103.3% ± 2.2% AR; fungicides: 103.5% ± 2.6% AR). Mineralization was low at mean amounts of up to 0.9% AR, and other volatiles detected in the ethylene glycol traps remained <0.1% AR in any sample throughout the experiment. Non-extractable residues steadily increased throughout incubation and reached means of 15.3% AR in the control, and 14.1% AR in the fungicide-treated soils. The limit of detection and the limit of quantification were estimated to be <0.5% and <1.0% AR for LSC and HPLC, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Mass balances of [14C]-iodosulfuron-methyl-sodium in loamy sand soil samples treated with iodosulfuron-methyl-sodium only (left), or together with tebuconazole and prothioconazole (right). The application pattern is described in the text. Mean values and standard deviations (1SD) were derived from triplicates (n = 3) and are expressed as the percentage of applied radioactivity (% AR).

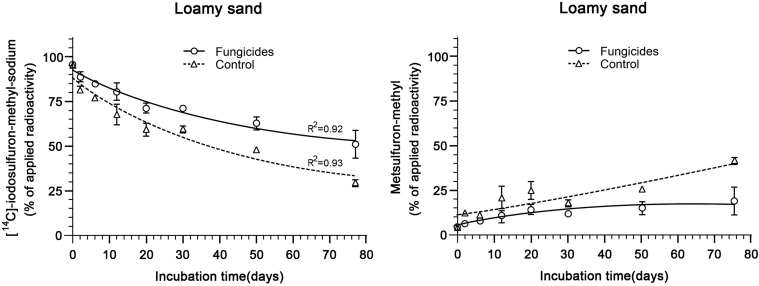

Degradation of iodosulfuron-methyl-sodium proceeded via reductive elimination of iodine from the phenyl ring to metsulfuron-methyl as main degradation product, and by hydrolysis of the phenyl-based carboxylate ester. The degradation rate of the herbicide was considerably reduced in the presence of the fungicides (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Recovery (in % AR) of [14C]-iodosulfuron-methyl-sodium (left) and its main metabolite metsulfuron-methyl (right) from a loamy sand soil (n = 3; 1SD). Triangular data with dotted fit depict soil samples treated with iodosulfuron-methyl-sodium only (control), circular data with solid fit describe soil samples treated with tebuconazole and prothioconazole 14 days prior to, then on the same day as, and again 5 days after application of radiolabeled iodosulfuron-methyl-sodium, thus simulating a typical pesticide spray series. R2 depicts the goodness of the fit (observed versus predicted data).

Time for 50% and 90% of the disappearance of the herbicide in the loamy sand soil were 40.3 (DT50) and 134 days (DT90) in the absence of the fungicides but were about two times longer under co-application of the fungicides (89.2 and 296 days, respectively), as calculated by CAKE software tool [34] using the single first-order kinetic model, which returned optimal statistical output and was evaluated as best-fit [35].

3.2. Literature

Swarcewicz and Gregorczyk [36] studied the dependence of the degradation of pendimethalin, a herbicide, asking the question of whether the presence of other pesticides, the fungicide mancozeb, and the insecticide thiamethoxam, has an impact on its fate. Mixtures of pendimethalin with mancozeb only or with mancozeb and thiamethoxam significantly retarded the degradation of pendimethalin under controlled conditions (Table 2). However, co-application of the herbicide metribuzin or thiamethoxam had no significant impact on pendimethalin degradation.

Table 2.

Influence of the presence of other pesticides on the dissipation of pendimethalin in soil under laboratory conditions [36].

| Treatment | DT50 (in days) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Sandy loam soil | Clay loam soil | |

| Pendimethalin alone | 26.9 | 44.4 |

| Pendimethalin + thiametoxam | 35.6 | 54.4 |

| Pendimethalin + metribuzin | 28.7 | 37.7 |

| Pendimethalin + mancozeb | 46.1 | 63.9 |

| Pendimethalin + thiametoxam + mancozeb | 62.2 | 63.3 |

The same authors investigated the effect of mancozeb in mixtures with the insecticides bromfenvinphos, diazinon, and metribuzin on the respiration and nitrification activities in soil, indicating reduced microbiological activity of the soil by the insecticides. From this finding, they suggested the degradation potential of the soil being lower [36].

Kaufman [37] showed that the herbicide dalapon is more persistent in soil when applied in combination with amitrole. The rate of dalapon degradation decreased with increasing concentrations of amitrole. The author explained this finding with the inhibition of dalapon-decomposing microorganism by amitrole. The presence of the antifungal fumigant Vorlex resulted in increased persistence of linuron [38]. Swarcewicz et al. [39] showed that the mixture of the herbicide linuron with the fungicide mancozeb in both soils significantly increased the persistence of linuron, whereas mixtures of linuron with chlorothalonil, thiamethoxam and clothianidin did not have any effect. The degradation of the herbicide diclofop-methyl in soil and the influence of pesticide mixtures on its persistence were investigated by Karanth et al. [40]. Ninety percent of the applied herbicide disappeared from the soil within 2 days approximately, if applied alone, mainly by forming non-extractable residues (>60% of the applied amount) and mineralization (ca. 25%). When the insecticides parathion and demeton-S-methyl sulphoxide were added to the herbicide, at the end of soil incubation (day 105) the degradation of diclofop-methyl compared with the degradation of the herbicide alone was reduced by ca. 20%.

The above examples show that mixture components may have a negative impact on the degradation of individual substances in the mixture. Other reports reveal that the degradation behavior does not or only slightly differ between single substances and mixtures. The effect of different herbicides, fungicides, and insecticides on the degradation of pendimethalin in soil was investigated by Plieth and Börner [41]. They showed that co-application of mecoprop, triadimefon, thiophanate methyl, bromophos, and oxydementon methyl did only slightly reduce the degradation of pendimethalin under field conditions, whereas the addition of straw significantly reduced pendimethalin degradation, probably because of the adsorption of pendimethalin to the straw material and reduced bioavailability. Smith [38] reported that the loss of both triallate and trifluralin from plots treated with the mixture was the same as from plots treated with the individual compounds.

4. Discussion

Soils are ecological drivers for biological flux and essential preservers of groundwater and plant contamination [42]. Pesticides, however, can endanger microbial soil life such as mycorrhizal fungi, which stimulate plants’ stress defense and nutrient uptake [13,43]. Although ammonification is usually not impaired by stress, the few microbial communities running nitrification processes are prone to be impacted by xenobiotic soil input such as pesticides [44]. Bacteria, fungi, and algae are largely responsible for the biodegradation of agrochemicals in the soil and aquatic environment. Representative bacterial species encompass Pseudomonas, Bacillus, Alcaligenes, Flavobacterium, and actinomycetes Micromonospora, Actinomyces, Nocardia, and Streptomyces. Representative fungi include Aspergillus, Penicillium, Fusarium, Mucor, Trichoderma spp, Morteriella sp., Rhizopus, Cladosporium, as well as lignin degraders white-rot fungi. Numerous microbial species foster metabolization of agrochemicals in soil. This biodegradation embraces multiple distinct reactions, and advances via mineralization, as well as co-metabolism [45,46].

The fungicides tebuconazole and prothioconazole, when applied to the soil according to good agricultural practice, were found to significantly hamper the degradation velocity of the herbicide iodosulfuron-methyl-sodium in loamy sand soil. Tebuconazole can harm soil microbes, as demonstrated by Muñoz-Leoz et al. [47]. They showed that when compared with non-treated control soils, the microbiota in tebuconazole-treated soils at various concentrations (5, 50, and 500 mg per kg of soil) was adversely affected and did not recover over time (90 days). Negative effects on basal respiration were concentration independent [47]. Throughout the first 30 days of incubation, nitrification was inhibited and a shift in bacterial composition was observed. An adverse effect of denitrifying soil bacteria by tebuconazole was demonstrated [48], as well as the similar effects of tebuconazole [49]. Besides, Zhang et al. [50] indicated that difenoconazole, another widely used triazole fungicide, has a concentration- and soil-type-dependent adverse impact on the heterogeneity of soil bacteria in diverse soils incubated for up to two months. However, it remains undisclosed how the fungicides tebuconazole and prothioconazole affected the soil microflora, and hence lead to the retarded metabolization of the herbicide iodosulfuron-methyl-sodium. Investigations on these processes would provide interesting topics for further research.

4.1. Tebuconazole

The fungicide mixture Falcon 460 EC containing tebuconazole, triadimenol, and spiroxamine was applied to a sandy loam soil at the manufacturer’s recommended dose of 0.092 mg of each active ingredient per kg of soil (dry weight), as well as at a 300-time exaggerated dose of 27.6 mg/kg, followed by incubation of the soils for up to 50 days [49]. Subsequently, the activities of enzymes dehydrogenases, catalase, urease, acid phosphatase, and alkaline phosphatase were assessed, which are essential in the terrestrial environment and of utmost importance for the degradation of chemicals. Falcon 460 EC used in both the recommended and exaggerated doses had a toxic effect on all soil enzymes tested with a major influence on catalase activity [49]. Catalase is known as an antioxidant enzyme that catalyzes the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide into water and oxygen in the cells exposed to environmental stress [51]. Saha et al. [52] showed that tebuconazole adversely impacts denitrification in clayey calcareous soil, but invigorates ammonification and nitrification. These effects were transient at lower tebuconazole concentrations of 188 and 375 g/ha but increased at 1875 g/ha along with a decrease in microbial activity. In a similar experiment, Falcon 460 EC was applied to a sandy clay soil at the manufacturer’s recommended dose of 0.092 mg of each active ingredient per kg of soil (dry weight), as well as at 2.76, 13.80, and 27.60 mg/kg, followed by wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cultivation after 7 days and subsequent incubation for up to 50 days [53]. At both intervals, numbers of actinomycetes, fungi, and organotrophic bacteria were counted, and soil enzymatic activities (acid phosphatase, alkaline phosphatase, catalase, dehydrogenases, and urease) were determined. The fungicide mixture was shown to reduce the numbers of actinomycetes, fungi, and organotrophic bacteria along with all enzymatic activities, except for alkaline phosphatase. Also, wheat yields decreased. In terms of microbial abundance and enzyme activity, fungi and urease were most sensitive to contamination with the fungicide combination. However, the composition of fungi increased, eventually due to evolving tolerant fungi species and enhanced aliment supply by release from dead microbe cells, while heterogeneity of organotrophic bacteria and actinomycetes tapered. The adverse effects of the fungicide mixture on the tested biological soil parameters were positively correlated with its concentration.

Staley et al. [54] reviewed a collection of studies examining the direct effects of herbicides, insecticides, and fungicides on microbial populations of algae, bacteria, protozoa, and fungi in water bodies. They concluded that all three pesticide types induced direct adverse effects on all four microbial species. Aquatic algae and fungi were equally highly sensitive to herbicides, insecticides, and fungicides. Bacteria were most susceptible to fungicides compared with exposure to herbicides and insecticides.

4.2. Other fungicides

Although information about the influence of tebuconazole and prothioconazole on soil parameters is scarce, numerous studies describing the impact of other fungicides on microbial soil life can be found. For instance, the mitochondrial respiration constraining broad-spectrum fungicide azoxystrobin was applied to a sandy loam alkali soil at a manufacturer’s recommended dose of 0.075 mg/kg, as well as at exaggerated concentrations of 2.250, 11.250, and 22.500 mg/kg, followed by incubation at 25 °C for up to 90 days [55]. After 30, 60, and 90 days of incubation, counts of organotrophic bacteria, actinomycetes, and fungi were determined. Additionally, dehydrogenases, catalase, and urease activities, as well as acid and alkaline phosphatase were assessed. Azoxystrobin was found to induce increasing distortion of soil microorganisms counts, diversity, and enzymatic activity with rising fungicide concentrations. Nonetheless, selected bacterial and fungal strains indicated resilience to soil pollution with azoxystrobin.

In addition, the fungicides cyprodinil, dimoxystrobin, and epoxiconazole were demonstrated to have a concentration- as well as a dwelling-time-dependent negative effect on soil enzymatic activity in a loamy sand soil, as measured by dehydrogenase, urease, acid phosphatase, and alkaline phosphatase ranges [56].

4.3. Herbicides

Similar findings were obtained in soil enzyme activity studies with other agrochemicals than fungicides. A mixture of herbicides terbuthylazine, mesotrione, and S-metolachlor was revealed to affect the microbial composition in a sandy loam soil [57]. After 30 and 60 days of herbicidal incubation, proportions of oligotrophic spores, organotrophic bacteria, and fungi in soil declined, whereas oligotrophic bacteria and endospore-forming oligotrophic bacteria increased. Additionally, enzymatic dehydrogenase, urease, β-glucosidase, catalase, arylsulfatase, and phosphatase activities were inhibited.

The herbicide iodosulfuron-methyl-sodium also impacts the soil fungal biomass. Vazquez and Bianchinotti [58] found that three fungal soil strains, Mucor, Penicillium, and Trichoderma, can digest metsulfuron-methyl from the major soil residue and structural analogue of iodosulfuron-methyl-sodium. However, the agrochemical hindered the development of the Penicillium strain. Further, He et al. [59] noted that Penicillium can degrade metsulfuron-methyl after overcoming an initial phase of chemical-induced stress.

The herbicide metazachlor was applied to a sandy loam soil at various concentrations ranging from 0.333 mg/kg (a recommended dose) to 213.3 mg/kg, with subsequent cultivation of spring oilseed rape. Soil samples were analyzed for microorganism counts, diversity, and enzymatic activities after 30 and 60 days of incubation [60]. This experiment illustrated that the soil biological activity, represented by all tested parameters, including spring oilseed rape, was sensitive to the herbicide metazachlor. The adverse effect again was positively correlated with increasing metazachlor concentration.

A resemblant study was performed by Tomkiel et al. [61], who investigated the effects of combined application of herbicides flufenacet and isoxaflutole on the count and diversity of microorganisms, as well as on the enzymatic activity in a sandy clay soil under maize growth. The herbicides were applied at different concentrations from 0.25 to 160 mg per kg of soil. Soil samples were analyzed after 30 and 60 days of incubation. In the soil treated with the herbicides, numbers of Azotobacter, organotrophic bacteria, actinobacteria, and fungi were adversely affected with time by the herbicide mixture. Additionally, the enzymatic catalase, urease, alkaline phosphatase, and arylsulfatase soil activities were impeded, and dehydrogenase and β-glucosidase activities were dwarfed. Azotobacter bacteria were most sensitive to flufenacet and isoxaflutole, and the respective impact increased with increasing herbicide concentrations. In terms of enzymatic activity, the strongest and concentration-dependent effect was observed on catalase and dehydrogenase. Furthermore, a drop in maize yield was detected. Analogous findings were obtained by Niewiadomska et al. [62]. They tested the effects of selected post-emergence herbicides on the activity of a loamy sand soil after 3, 30, and 60 days of incubation, and discovered herbicide-induced reductions of actinobacteria, and dehydrogenase and alkaline phosphatase activities. Tomkiel et al. [63] addressed the impact of herbicide mixture pethoxamid and terbuthylazine on the numbers and diversity of microbes, and enzymatic activities in a sandy loam soil at varying concentrations incubated for up to 160 days. The herbicides invigorated the growth of actinomycetes, and oligotrophic and organotrophic bacteria but hindered Azotobacter spp. and fungal development. The inhibition of the activity of dehydrogenases, urease, acid phosphatase, arylsulfatase, and β-glucosidase was positively correlated with the herbicides dose rate, among which urease activity is the most adversely impacted.

4.4. Interactions in soil

The fate of agrochemicals depends not only on soil microbial activity, but also on physical and chemical soil properties. One of these drivers is the competition for soil adsorption sites. Pesticides that are adsorbed to soil particles are not yet reached by microorganisms, and hence are not available for biodegradation. Several studies have shown that with decreasing adsorption capacity of the soil, the degradation of herbicides is accelerated due to higher accessibility for soil microorganisms. Additionally, nutrients with similar chemical structures to the pesticide, such as phosphate and glyphosate, might compete for soil binding sites and influence the pesticide’s fate in the soil environment. If the nutrient is the preferred constituent for soil adsorption and saturates the soil environment, the structurally similar pesticide might be more mobile. As a result, pesticide leaching to groundwater and nearby water bodies may be a potential risk [64]. Furthermore, Šudoma et al. [23] indicated that longer interaction between soil and conazole pesticides, such as tebuconazole, does not necessarily lead to less bioaccumulation in earthworms and bioconcentration in plants. Sorption processes of chemicals to the soil, namely ageing, are related to the soil organic matter content, texture or clay content, cation exchange capacity, and surface area. By ageing in finer soils with higher clay content, bioaccumulation of conazole pesticides in earthworms was reduced, compared to being elevated in coarse (sandy) soils. By contrast, bioaccumulation was enhanced in soils with higher organic matter content, probably due to the affection of composter E. Andrei to organic matter.

4.5. Summary

In summary, agrochemicals that enter the soil environment can affect microbial soil life directly by deranging extracellular enzymatic activity, or indirectly through disturbing enzyme biosynthesis and population composition of microbes [65]. Soil microorganisms are usually studied as markers of soil quality due to their sensitivity, which contributes to the ability to adjust to changing environmental conditions much faster than other soil components [61]. In recent years, the use of soil microcosms, or terrestrial model ecosystems approaches have been promoted in literature to establish the influence of agrochemicals on joint ecological processes. Although various publications have stated only a few effects of pesticides on microbial soil life when applied at recommended dose rates, simultaneous, cumulative, and persistent presence of one or more xenobiotic compounds in the soil environment can induce biochemical imbalance, reducing soil fertility and productivity through striking metabolism and enzymatic activities. To enhance the identification of custom enzymatic activity responses to chemical treatment of soils, further studies built on new analytical technologies, such as real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR), are needed to assess the expression of genes that encompass important ecological tasks. Nevertheless, designing such studies is difficult in different aspects, such as selecting the correct agrochemicals and dosing rates to be applied, as well as the soil parameters and enzymatic activities to be evaluated [66]. Furthermore, elucidation of ecotoxicological effects on soil embracing a large scale of parameters can be delicate, as toxicologically induced dead biomass might be used as nutrition for the remaining microorganisms to grow. Hence, this process can distort scientific results [67].

5. Conclusion

We conclude that the breakdown of major herbicides is not significantly affected by application in combination with other herbicides; however, in the presence of fungicides, such an effect may occur.

We demonstrated that the fungicides tebuconazole and/or prothioconazole have a significant adverse effect on the biodegradation of the herbicide iodosulfuron-methyl-sodium in soil. This effect was illustrated by inhibited biotic transformation of the herbicide to its main soil metabolite, metsulfuron-methyl. Nonetheless, the precise fungicide-induced processes in soil leading to hampered biodegradation of the herbicide remain unclear and are a topic for further studies, for example, by next-generation sequencing and qPCR on specific functional genes.

Many articles have been published about the effects of pesticides on microbial soil life. Conduction of additional studies investigating the effect of pesticide combinations on the degradation of single chemical compounds in the environment is of utmost importance. Pesticide use continues to boost and generate an increasing number and concentrations of agrochemicals to contaminate terrestrial, freshwater, and marine ecosystems. This demands more environmentally realistic laboratory research on pesticide mixtures in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. Therefore, it is crucial to improve the perception of pesticides and, specifically, fungicide effects in the natural environment [68]. New perceptions can subsequently be incorporated in smarter regulatory frameworks on pesticide risk assessments.

Furthermore, soils are of utmost environmental importance through impelling biological processes. Therefore, it is highly desirable to reduce the use of agricultural fungicides by promoting sustainable food production in conjunction with impeding the progression of arable land into surrounding areas and minimizing agrochemical leakage to the aquatic environment.

Conflicts of interest

Both authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank MSc Kim Nguyen for valuable discussions.

References

- 1.Persson L.M., Breitholtz M., Cousins I.T., de Wit C.A., MacLeod M., McLachlan M.S. Confronting unknown planetary boundary threats from chemical pollution. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013;47(22):12619–12622. doi: 10.1021/es402501c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rockstrom J., Steffen W., Noone K., Persson Å., Chapin F.S., III, Lambin E.F., Lenton T.M., Scheffer M., Folke C., Schellnhuber H.J., et al. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature. 2009;461(7263):472–475. doi: 10.1038/461472a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steffen W., Richardson K., Rockström J., Cornell S.E., Fetzer I., Bennett E.M., Biggs R., Carpenter S.R., de Vries W., de Wit C.A., et al. Planetary boundaries: guiding human development on a changing planet. Science. 2015;347(6223):737–746. doi: 10.1126/science.1259855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Legrand A., Gaucherel C., Baudry J., Meynard J.M. Long-term effects of organic, conventional, and integrated crop systems on Carabids. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2011;31(3):515–524. doi: 10.1007/s13593-011-0007-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hahn M., Schotthofer A., Schmitz J., Franke L.A., Bruhl C.A. The effects of agrochemicals on Lepidoptera, with a focus on moths, and their pollination service in field margin habitats. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2015;207:153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2015.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmitz J., Hahn M., Bruhl C.A. Agrochemicals in field margins - An experimental field study to assess the impacts of pesticides and fertilizers on a natural plant community. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2014;193:60–69. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2014.04.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hallmann C.A., Foppen R.P.B., van Turnhout C.A.M., de Kroon H., Jongejans E. Declines in insectivorous birds are associated with high neonicotinoid concentrations. Nature. 2014;511(7509):341. doi: 10.1038/nature13531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hallmann C.A., Sorg M., Jongejans E., Siepel H., Hofland N., Schwan H., Stenmans W., Müller A., Sumser H., Hörren T., et al. More than 75 percent decline over 27 years in total flying insect biomass in protected areas. PLoS One. 2017:1–21. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woodcock B.A., Isaac N.J.B., Bullock J.M., Roy D.B., Garthwaite D.G., Crowe A., Pywell R.F. Impacts of neonicotinoid use on long-term population changes in wild bees in England. Nat. Commun. 2016;7 doi: 10.1038/ncomms12459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goulson D. An overview of the environmental risks posed by neonicotinoid insecticides. J. Appl. Ecol. 2013;50(4):977–987. doi: 10.1111/1365-2664.12111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rundlof M., Andersson G.K.S., Bommarco R., Fries I., Hederström V., Herbertsson L., Jonsson O., Klatt B.K., Pedersen T.R., Yourstone J., et al. Seed coating with a neonicotinoid insecticide negatively affects wild bees. Nature. 2015;521(7550):77–U162. doi: 10.1038/nature14420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiaia-Hernandez A.C., Keller A., Wächter D., Steinlin C., Camenzuli L., Hollender J., Krauss M. Long-Term persistence of pesticides and TPs in archived agricultural soil samples and comparison with pesticide application. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017;51(18):10642–10651. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.7b02529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riedo J., Wettstein F.E., Rösch A., Herzog C., Banerjee S., Büchi L., Charles R., Wächter D., Martin-Laurent F., Bucheli T.D., et al. Widespread occurrence of pesticides in organically managed agricultural soils-the ghost of a conventional agricultural past? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021;55(5):2919–2928. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c06405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silva V., Mol H.G.J., Zomer P., Tienstra M., Ritsema C.J., Geissen V. Pesticide residues in European agricultural soils - A hidden reality unfolded. Sci. Total Environ. 2019:1532–1545. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.10.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schäfer R.B., Liess M., Altenburger R., Filser J., Hollert H., Roß-Nickoll M., Schäffer A., Scheringer M. Future pesticide risk assessment: narrowing the gap between intention and reality. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2019;31(1) doi: 10.1186/s12302-019-0203-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sybertz A., Ottermanns R., Schäffer A., Scholz-Starke B., Daniels B., Frische T., Bär S., Ullrich C., Roß-Nickoll M. Simulating spray series of pesticides in agricultural practice reveals evidence for accumulation of environmental risk in soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;710:135004. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shahid N., Becker J.M., Krauss M., Brack W., Liess M. Pesticide body burden of the Crustacean gammarus pulex as a measure of toxic pressure in agricultural streams. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018;52(14):7823–7832. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b01751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schaeffer A., Amelung W., Hollert H., Kaestner M., Kandeler E., Kruse J., Miltner A., Ottermanns R., Pagel H., Peth S., et al. The impact of chemical pollution on the resilience of soils under multiple stresses: a conceptual framework for future research. Sci. Total Environ. 2016;568:1076–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.06.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bernhardt E.S., Rosi E.J., Gessner M.O. Synthetic chemicals as agents of global change. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2017;15(2):84–90. doi: 10.1002/fee.1450. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.OECD Guidelines for the testing of chemicals, Section 3. Environ. Fate Behav. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 21.U. S. EPA . 2008. Fate, Transport and Transformation Test Guidelines: United States Environmental Protection Agency, 7101. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hvězdová M., Kosubová P., Košíková M., Scherr K.E., Šimek Z., Brodský L., Šudoma M., Škulcová L., Sáňka M., Svobodová M., et al. Currently and recently used pesticides in Central European arable soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2018;613–614:361–370. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Šudoma M., Peštálová N., Bílková Z., Sedláček P., Hofman J. Ageing effect on conazole fungicide bioaccumulation in arable soils. Chemosphere. 2021;262:127612. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.127612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kwok I.M.-Y., Loeffler R.T. The biochemical mode of action of some newer azole fungicides. Pestic. Sci. 1993;39(1):1–11. doi: 10.1002/ps.2780390102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lepesheva G.I., Waterman M.R. Sterol 14alpha-demethylase cytochrome P450 (CYP51), a P450 in all biological kingdoms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1770(3):467–477. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bayer CropScience Limited . 2020. Tank-mix sheet: Prosaro.https://cropscience.bayer.co.uk/data/documents/fungicides/prosaro/prosaro-tank-mixes/ Revised May 2020. [Online]. Available: [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson J., Domsch K.H. A physiological method for the quantitative measurement of microbial biomass in soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1978;10(3):215–221. doi: 10.1016/0038-0717(78)90099-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) Peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance iodosulfuron-methyl-sodium (approved as iodosulfuron) EFS2. 2016;14(4) doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2016.4453. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.FAO . Report of the Joint Meeting of the FAO Panel of Experts on Pesticide Residues in Food and the Environment. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; Rome, Italy: 1997. Tebuconazole: Part I: residues.http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/agphome/documents/Pests_Pesticides/JMPR/Evaluation97/Tebucon.PDF [Online]. Available: [Google Scholar]

- 30.U.S. EPA . United States Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Prevention, Pesticides and Toxic Substances; Washington D.C. 20460, U.S.A.: 2007. Prothioconazole: Pesticide Fact Sheet; p. 7501. [Google Scholar]

- 31.European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) Conclusion regarding the peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance prothioconazole. EFS2. 2007;5(8):106r. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2007.106r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.OECD . Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD); 2002. OECD Guideline for the Testing of Chemicals: Test no. 307: Aerobic and Anaerobic Transformation in Soil. [Google Scholar]

- 33.U.S. EPA . United States Environmental Protection Agency; 2008. Fate, Transport and Transformation Test Guidelines: OPPTS 835.4100 Aerobic Soil Metabolism, OPPTS 835.4200 Anaerobic Soil Metabolism; p. 7101.https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyNET.exe/P100J6WF.TXT?ZyActionD=ZyDocument&Client=EPA&Index=2006+Thru+2010&Docs=&Query=&Time=&EndTime=&SearchMethod=1&TocRestrict=n&Toc=&TocEntry=&QField=&QFieldYear=&QFieldMonth=&QFieldDay=&IntQFieldOp=0&ExtQFieldOp=0&XmlQuery=&File=D%3A%5Czyfiles%5CIndex%20Data%5C06thru10%5CTxt%5C00000035%5CP100J6WF.txt&User=ANONYMOUS&Password=anonymous&SortMethod=h%7C-&MaximumDocuments=1&FuzzyDegree=0&ImageQuality=r75g8/r75g8/x150y150g16/i425&Display=hpfr&DefSeekPage=x&SearchBack=ZyActionL&Back=ZyActionS&BackDesc=Results%20page&MaximumPages=1&ZyEntry=1&SeekPage=x&ZyPURL [Online]. Available: [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tessella . UK for Syngenta; Abingdon, Oxfordshire: 2020. Computer Assisted Kinetic Evaluation (CAKE) [Google Scholar]

- 35.FOCUS . Guidance Document on Estimating Persistence and Degradation Kinetics from Environmental Fate Studies on Pesticides in EU Registration: Report of the FOCUS Work Group on Degradation Kinetics. 10058th ed. 2006. https://esdac.jrc.ec.europa.eu/public_path/projects_data/focus/dk/docs/finalreportFOCDegKinetics.pdf [Online]. Available: [Google Scholar]

- 36.Swarcewicz M.K., Gregorczyk A. The effects of pesticide mixtures on degradation of pendimethalin in soils. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2012;184(5):3077–3084. doi: 10.1007/s10661-011-2172-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaufman D.D. Microbial degradation of herbicide combinations: amitrole and Dalapon. Weeds. 1966;14:130–134. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith A.E. Soil persistence experiments with C-14 2,4-D in herbicidal mixtures, and field persistence studies with tri-allate and trifluralin both singly and combined. Weed Res. 1979;19(3):165–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3180.1979.tb01523.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Swarcewicz M., Gregorczyk A., Sobczak J. Comparison of linuron degradation in the presence of pesticide mixtures in soil under laboratory conditions. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2013;185(10):8109–8114. doi: 10.1007/s10661-013-3158-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karanth N.G.K., Anderson J.P.E., Domsch K.H. Degradation of the herbicide diclofop-methyl in soil and influence of pesticide mixtures on its persistence. J. Biosci. 1984;6(6):829–837. doi: 10.1007/BF02716843. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Plieth H.E., Borner H. Degradation of pendimethalin in the soil of barley crop under the influence of other pesticides and straw. Zeitschrift Fur Pflanzenkrankheiten Und Pflanzenschutz-Journal of Plant Diseases and Protection. 1985;92(3):288–304. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baćmaga M., Borowik A., Kucharski J., Tomkiel M., Wyszkowska J. Microbial and enzymatic activity of soil contaminated with a mixture of diflufenican + mesosulfuron-methyl + iodosulfuron-methyl-sodium. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2015;22(1):643–656. doi: 10.1007/s11356-014-3395-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Begum N., Qin C., Ahanger M.A., Raza S., Khan M.I., Ashraf M., Ahmed N., Zhang L. Role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in plant growth regulation: implications in abiotic stress tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2019;10:1068. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Monkiedje A., Spiteller M. Effects of the phenylamide fungicides, mefenoxam and metalaxyl, on the microbiological properties of a sandy loam and a sandy clay soil. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 2002;35(6):393–398. doi: 10.1007/s00374-002-0485-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang Y., Xiao L., Li F., Xiao M., Lin D., Long X., Wu Z. Microbial degradation of pesticide residues and an emphasis on the degradation of cypermethrin and 3-phenoxy benzoic acid: a review. Molecules. 2018;23(9) doi: 10.3390/molecules23092313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aislabie J., Lloyd-Jones G. A review of bacterial-degradation of pesticides. Soil Res. 1995;33(6):925. doi: 10.1071/SR9950925. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Muñoz-Leoz B., Ruiz-Romera E., Antigüedad I., Garbisu C. Tebuconazole application decreases soil microbial biomass and activity. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011;43(10):2176–2183. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2011.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cycoń M., Piotrowska-Seget Z., Kaczyńska A., Kozdrój J. Microbiological characteristics of a sandy loam soil exposed to tebuconazole and lambda-cyhalothrin under laboratory conditions. Ecotoxicology. 2006;15(8):639–646. doi: 10.1007/s10646-006-0099-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baćmaga M., Wyszkowska J., Kucharski J. The biochemical activity of soil contaminated with fungicides. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part B Pestic. Food Contam. Agric. Wastes. 2019;54(4):252–262. doi: 10.1080/03601234.2018.1553908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang H., Song J., Zhang Z., Zhang Q., Chen S., Mei J., Yu Y., Fang H. Exposure to fungicide difenoconazole reduces the soil bacterial community diversity and the co-occurrence network complexity. J. Hazard Mater. 2021;405:124208. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sharma I., Ahmad P. Oxidative Damage to Plants. Elsevier; 2014. Catalase; pp. 131–148. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saha A., Pipariya A., Bhaduri D. Enzymatic activities and microbial biomass in peanut field soil as affected by the foliar application of tebuconazole. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016;75(7) doi: 10.1007/s12665-015-5116-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baćmaga M., Kucharski J., Wyszkowska J. Microbiological and biochemical properties of soil polluted with a mixture of spiroxamine, tebuconazole, and triadimenol under the cultivation of Triticum aestivum L. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2019;191(7):416. doi: 10.1007/s10661-019-7539-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Staley Z.R., Harwood V.J., Rohr J.R. A synthesis of the effects of pesticides on microbial persistence in aquatic ecosystems. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2015;45(10):813–836. doi: 10.3109/10408444.2015.1065471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baćmaga M., Kucharski J., Wyszkowska J. Microbial and enzymatic activity of soil contaminated with azoxystrobin. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2015;187(10):615. doi: 10.1007/s10661-015-4827-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jastrzębska E., Kucharski J. Dehydrogenases, urease and phosphatases activities of soil contaminated with fungicides. Plant Soil Environ. 2008;53(No. 2):51–57. doi: 10.17221/2296-pse. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Borowik A., Wyszkowska J., Kucharski J., Baćmaga M., Tomkiel M. Response of microorganisms and enzymes to soil contamination with a mixture of terbuthylazine, mesotrione, and S-metolachlor. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2017;24(2):1910–1925. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-7919-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vázquez M.B., Bianchinotti M.V. Isolation of metsulfuron methyl degrading fungi from agricultural soils in Argentina. Phyton - Int. J. Exp. Botany Ba Argentina. 2013;82(1):113–118. [Google Scholar]

- 59.He Y.H., Shen D.S., Fang C.R., Zhu Y.M. Rapid biodegradation of metsulfuron-methyl by a soil fungus in pure cultures and soil. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2006;22(10):1095–1104. doi: 10.1007/s11274-006-9148-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Baćmaga M., Kucharski J., Wyszkowska J., Borowik A., Tomkiel M. Responses of microorganisms and enzymes to soil contamination with metazachlor. Environ. Earth Sci. 2014;72(7):2251–2262. doi: 10.1007/s12665-014-3134-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tomkiel M., Baćmaga M., Borowik A., Kucharski J., Wyszkowska J. Effect of a mixture of flufenacet and isoxaflutole on population numbers of soil-dwelling microorganisms, enzymatic activity of soil, and maize yield. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part B Pestic. Food Contam. Agric. Wastes. 2019;54(10):832–842. doi: 10.1080/03601234.2019.1636601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Niewiadomska A., Sulewska H., Wolna-Maruwka A., Waraczewska Z., Budka A., Ratajczak K. An assessment of the influence of selected herbicides on the microbial parameters of soil in maize (Zea mays) cultivation. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2018;16:4735–4752. doi: 10.15666/aeer/1604_47354752. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tomkiel M., Wyszkowska J., Kucharski J., Baćmaga M., Borowik A. Response of microorganisms and enzymes to soil contamination with the herbicide Successor T 550. Environ. Protect. Eng. 2014;40(4) doi: 10.37190/epe140402. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kanissery R. Herbicide - nutrient interactions in soil: a short review. ARTOAJ. 2018;15(2) doi: 10.19080/ARTOAJ.2018.15.555951. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Niewiadomska A., Skrzypczak G., Sobiech Ł., Wolna-Maruwka A., BOROWIAK K., Budka A. The effect of diflufenican and its mixture with S-metolachlor and metribuzin on nitrogenase and microbial activity of soil under yellow lupine (Lupinus luteus L.) Tarim Bilimleri Dergisi. 2018;24:130–142. doi: 10.15832/ankutbd.446412. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Riah W., Laval K., Laroche-Ajzenberg E., Mougin C., Latour X., Trinsoutrot-Gattin I. Effects of pesticides on soil enzymes: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2014;12(2):257–273. doi: 10.1007/s10311-014-0458-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bending G.D., Rodríguez-Cruz M.S., Lincoln S.D. Fungicide impacts on microbial communities in soils with contrasting management histories. Chemosphere. 2007;69(1):82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2007.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fernández D., Voss K., Bundschuh M., Zubrod J.P., Schäfer R.B. Effects of fungicides on decomposer communities and litter decomposition in vineyard streams. Sci. Total Environ. 2015;533:40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.06.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]