Abstract

Brominated disinfection by-products (Br-DBPs) can form during the chlorination of drinking water in treatment plants (DWTP). Regulations exist for a small subset of Br-DBPs; however, hundreds of unregulated Br-DBPs have been detected, and limited information exists on their occurrence, concentrations, and seasonal trends. Here, a data-independent precursor isolation and characteristic fragment (DIPIC-Frag) method were optimized to screen chlorinated waters for Br-DBPs. There were 553 Br-DBPs detected with m/z values ranging from 170.884 to 497.0278 and chromatographic retention times from 2.4 to 26.2 min. With MS2 information, structures for 40 of the 54 most abundant Br-DBPs were predicted. The method was then applied to a year-long study in which raw, clear well, and finished water were analyzed monthly. The 54 most abundant unregulated Br-DBPs were subjected to trend analysis. Br-DBPs with higher oxygen-to-carbon (O/C) and bromine-to-carbon (Br/C) ratios increased as water moved from the clear well to the finished stage, which indicated the dynamic formation of Br-DBPs. Monthly trends of unregulated Br-DBPs were compared to raw water parameters, such as natural organic matter, temperature, and total bromine, but no correlations were observed. It was found that total concentrations of bromine (TBr) in finished water (0.04–0.12 mg/L) were consistently and significantly greater than in raw water (0.013–0.038 mg/L, P < 0.001), suggesting the introduction of bromine during the disinfection process. Concentrations of TBr in treatment units, rather than raw water, were significantly correlated to 34 of the Br-DBPs at α = 0.05. This study provides the first evidence that monthly trends of unregulated Br-DBPs can be associated with the concentration of TBr in treated waters.

Keywords: Natural organic matter, Bromine, Chlorination, Drinking water treatment, High-resolution mass spectrometry

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Ultrahigh-resolution mass spectrometry was used to identify novel brominated disinfection by-products in a Canadian water treatment facility.

-

•

Several hundred novel brominated compounds were identified of which 54 were assigned chemical structures.

-

•

Seasonal variation in the generated DBPs was assessed over 11 months of sampling.

-

•

Increases in total bromine in drinking water were noted with progress through the treatment process.

1. Introduction

Disinfection by-products (DBPs) can form during the treatment of drinking water when chlorine disinfectants, in the form of hypochlorous acid, react with natural organic matter (NOM) to produce a diverse range of chlorinated compounds (Cl-DBPs). Hypochlorous acid (HClO) also reacts with bromide found in the source water to produce hypobromous acid (HBrO) [1], which can then react with NOM, possibly already brominated, or Cl-DBPs to produce brominated DBPs (Br-DBPs) [2,3,4]. DBPs are ubiquitous in drinking water with particular attention given to the four regulated trihalomethanes (THMs) and five regulated haloacetic acids (HAAs). In bench-scale experiments, these regulated DBPs cause cyto- and genotoxicity, and in epidemiological studies, they have been linked to elevated risks of bladder cancer and adverse pregnancy outcomes [5,6,7]. A wide range of currently unregulated DBPs often have greater toxic potencies than THMs or HAAs do, and a common trend has emerged that Br-DBPs are more potent than their Cl-DBP analogs [8,9,10,11,12]. However, due to their small abundances, chemical diversity, and lack of available authentic standards, most unregulated Br-DBPs remain uncharacterized.

High-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) is a promising method for characterizing previously unknown Br-DBPs in drinking water [13,14,15]. To date, approximately 700 halogenated DBPs have been identified, and more continue to be described [16]. For example, Fourier-transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry (FT-ICR-MS) was used to detect approximately 478 Br-DBPs in laboratory-produced drinking water from China [15]. Limited information is available on the occurrences of Br-DBPs in actual samples of drinking water, mainly due to the presence of complicated analytical interferences and lesser abundances of Br-DBPs in drinking water compared to Cl-DBPs. In addition, the limited scanning speeds of FT-ICR-MS make it less compatible with current high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) techniques, which means direct infusion mass spectrometry is the most commonly used approach. This method can be limited by matrix effects and thereby poses a challenge for comparative analysis of Br-DBPs, especially since authentic standards are not available for most unregulated Br-DBPs.

Seasonal variations in concentrations of regulated DBPs have been well documented during previous studies, and many factors have been demonstrated to impact the seasonal trends. Most often, the formation of THMs has been reported to be favored in summer due to warmer temperatures, greater rates of reaction, and greater production of organic precursors by algae [17,18,19,20,21]. Other reports indicated that THMs and HAAs are more abundant in spring and fall when concentrations of dissolved organic carbon (DOC) are greatest [22,23]. Some studies have investigated seasonal trends of unregulated classes of DBPs, such as haloacetonitriles, haloketones, and halonitromethanes, but still, limited information is available on seasonal variations of unregulated Br-DBPs. One study found that the concentrations of bromochloroacetonitrile and dibromoacetonitrile were greater in winter [24], while another study reported the greater occurrence of bromochloroacetonitrile in spring and autumn due to the elevated concentrations of bromide [21]. With limited studies and conflicting findings as mentioned above, there are still gaps in knowledge about seasonal trends in concentrations of unregulated Br-DBPs in drinking water and variables that drive their formation.

The objectives of this study were to use full-spectrum, non-targeted screening to investigate Br-DBPs in drinking water, explore monthly trends of selected unregulated Br-DBPs at a drinking water treatment plant (DWTP) in Saskatchewan, Canada, and identify factors that could predict occurrences of unregulated Br-DBPs. To do this: (1) the data-independent precursor isolation and characteristic fragment (DIPIC-Frag) method [25] was optimized and applied to screen unregulated Br-DBPs; (2) trends of the most abundant, unregulated Br-DBPs were investigated by comparing peak abundances through the treatment process as well as over time; and (3) correlation analysis was used to identify factors (e.g., bromine (Br), temperature, and UV254) that could be driving the monthly trends in relative abundances of unregulated Br-DBPs.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals and reagents

Bromoacetic acid, 4-bromophenol, iodoacetic acid, and bromomethanesulfonic acid were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Oasis HLB (6 cc, 500 mg, 30 μm), Oasis WAX (6 cc, 150 mg, 30 μm), and C18 (6 cc, 1 g, 30 μm) solid-phase extraction (SPE) cartridges were purchased from Waters (Milford, MA, USA). Hydrochloric acid, ammonium hydroxide, and pH indicator strips (ColorpHast, pH 0–6) as well as dichloromethane (DCM), methanol, and acetonitrile, Omni-Solv grade, were purchased from EMD Chemicals (Gibbstown, NJ, USA). G4 glass fiber filter circles were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Nepean, ON, Canada).

2.2. Collection of water samples

A total of 33 water samples were collected from a DWTP located in central Saskatchewan, Canada. Sampling began on April 19, 2016, twelve days after the ice-out on the river and continued on a monthly schedule, except August, 2016 until March 8, 2017. Samples of chlorinated water underwent five different SPE pre-treatment methods for method development. Details of sample collection and preparation are provided in the supporting information (SI). For the seasonal study, water was extracted by HLB cartridges with pH adjustment (pH < 2). Total organic and inorganic bromine (TBr) was analyzed by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) at the Environmental Analytical Laboratories of the Saskatchewan Research Council. The water characteristics, including turbidity, total organic carbon (TOC), total bromine, and other parameters, are provided in Table S1.

2.3. Quality control and quality assurance

To avoid contamination of samples, all equipment was rinsed regularly with methanol. One procedural blank using ultrapure water was incorporated in the analytical procedure. Background contamination from the blank was subtracted from samples for downstream data analysis, and those Br-DBPs whose abundances were less than three times the background abundance in blanks were considered non-detected. Some halogenated compounds were also detected in raw water, and thus only those compounds showing more than three-fold higher abundance in chlorinated water samples compared to raw water samples were considered to be Br-DBPs produced during the treatment process.

Because most of the detected Br-DBPs were unregulated compounds for which no authentic standards were available, intensities and height of peaks were used to semi-quantify their abundances in samples, as has been done previously for organobromine compounds in sediments [25]. To enhance comparability among samples and avoid potential shifts in sensitivity among compounds during multiple injections, the same set of methods (four methods in total for each sample to cover all the mass range) was run at the same time for all samples. Method detection limits (MDLs) could not be calculated for Br-DBPs, but a peak intensity cut-off of 50,000 was incorporated into the DIPIC-Frag method as described previously [26], and this was used as the MDL for the DBPs. For the DBPs peaks detected in blanks, 3 × the peak abundance in the blank was used as the MDL for samples.

2.4. Characterization of Br-DBPs and natural organic matter by UHRMS

Br-DBPs in extracts were analyzed using a Q Exactive™ ultrahigh-resolution mass spectrometer (UHRMS, negative ion mode) equipped with a Dionex™ UltiMate™ 3000 ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Data were acquired in data-independent acquisition (DIA) mode using the previously described DIPIC-Frag method [25]. Parameters for DIA were one full MS1 scan recorded at resolution R = 70,000 (at m/z 200) with a maximum of 3 × 106 ions collected within 100 ms, followed by six DIA MS/MS scans recorded at a resolution R = 35,000 (at m/z 200) with a maximum of 1 × 105 ions collected within 60 ms. DIA data were collected using 5-m/z-wide isolation windows per MS/MS scan. Each DIA MS/MS scan was chosen for analysis from a list of all 5 m/z isolation windows. In these experiments, eighty 5-m/z-wide windows between 100 and 500 m/z were grouped into four separate methods, each containing 20 windows. Mass spectrometric settings for atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI) mode were as follows: discharge current, 10 μA; capillary temperature, 225 °C; sheath gas, 20 L/h; auxiliary gas, 5 L/h; and probe heater temperature, 350 °C. Mass spectrometric settings for electrospray ionization (ESI) mode were as follows: spray voltage, 2.8 kV; capillary temperature, 300 °C; sheath gas, 35 L/h; auxiliary gas, 8 L/h; and probe heater temperature, 325 °C. In accordance with previous studies [27,28], only negative ionization mode was used in this current study, considering the complexity of spectra in positive ion mode and the better ionization efficiency of most DBPs in negative ion mode.

NOM was characterized by direct infusion on a Q Exactive™ HF Hybrid Quadrupole-Orbitrap™ mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Further analytical details are provided in the SI.

2.5. Data analyses

Correlation analyses were used to identify factors that could predict occurrences of 54 selected, unregulated Br-DBPs in finished water based on their measured peak abundances. Analyses were performed with eleven monthly measures of raw water parameters (temperature, turbidity, ultraviolet transmittance (UVT), color, river level), treatment conditions (pre- and post-chlorine doses), and total Br (TBr) at the raw, clear well, and finished treatment stages. Seven monthly measures (September–March) of TOC, UV254, and normalized specific absorbance (SUVA; UV245/DOC) of raw water were available from the DWTP (Table S1).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Non-targeted screening of unregulated Br-DBPs

To adapt the DIPIC-Frag method for full-scan, non-targeted screening of Br-DBPs in drinking waters, the chemometric strategy (see method section in SI) and analytical conditions (i.e., ionization source, HPLC column, and SPE) were optimized to enhance coverage of Br-DBPs. In previous DIPIC-Frag studies of sediments, better chemical coverage was achieved using APCI [29]; however, in this study, ESI was used and resulted in 10-fold greater sensitivity (Fig. S1). This might be because most DBPs are polar compounds, which can be preferentially ionized by ESI. Consistent with this, the hydrophilicity of Br-DBPs leads to poorer retention on the C18 column, with most of the Br-DBPs eluting in the first 3 min (Fig. S2). Thus, several hydrophilic columns (amide, T3, hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography [HILIC, XBridge™ HILIC, and Waters], and C18) were tested. The amide column with 0.1% NH4OH in water as the mobile phase gave the best separation, with multiple Br-DBPs peaks detected throughout the 2–15 min retention window (Fig. S2).

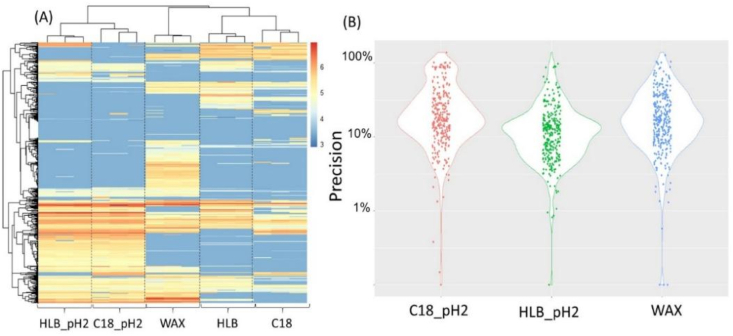

Five SPE methods were compared to achieve the best coverage: weak anion exchange (WAX), hydrophile-lipophile balance (HLB), C18, HLB_pH2, and C18_pH2. The first three SPE methods indicated the type of cartridge used and that no pH adjustment was made prior to extraction. HLB_pH2 and C18_pH2 indicated that the water samples were adjusted to pH < 2 prior to extraction. Triplicate analyses were conducted for each condition. While more than 200 unregulated Br-DBPs were detected by each method, heat maps of the detected Br-DBPs show complementary chemical coverage of the five SPE methods (Fig. 1A). When a peak intensity cut-off of 50,000 was used, 226 and 238 Br-DBPs were detected in samples extracted by C18 and HLB cartridges, respectively. As authentic standards are not available for the majority of detected Br-DBPs, the elemental compositions of Br-DBPs were predicted based on exact mass, isotopic peaks, and fragmentation patterns. Thus, all Br-DBPs were detected at confidence levels 3 or 4 according to the Schymanski scale [30]. Similar strategies or confidence levels were also adapted for FT-ICR-MS-based DBP screening as documented in several recent studies [13,14,15].

Fig. 1.

Peak intensities of Br-DBPs detected under various SPE conditions and associated method precisions. (A) Heat map and hierarchical clustering of log-transformed peak intensities of detected Br-DBPs. The color is proportional to the log-transformed peak intensities of Br-DBPs as indicated in the graph legend. (B) Method precision for each Br-DBP represented by violin plots. Precision was calculated as the relative standard deviation of each DBP to the mean value of intensities. The width of the violin indicates the frequency at that precision. HLB_pH2 and C18_pH2 represent the water samples concentrated with HLB and C18 SPE cartridges under pH < 2; C18, HLB, and WAX represent the water samples concentrated with C18, HLB, and WAX cartridges without pH adjustment.

When samples were adjusted to pH < 2 before extraction, a greater number of Br-DBPs were detected (291 and 290 Br-DBPs for C18_pH2 and HLB_pH2, respectively), which suggested that some acidic Br-DBPs have low pKa values (i.e., HAAs), and thus, their adsorptions on hydrophobic C18/HLB cartridges were improved [31]. Supporting this hypothesis, the greatest number of Br-DBPs (313) was detected in samples extracted by WAX cartridges, which specifically capture acidic compounds (Fig. 1A). Compared to direct infusion FT-ICR-MS [15], the advantage of the DIPIC-Frag method is the potential for the separation of isobaric compounds as well as the potential for fewer matrix effects provided by coupling to HPLC. Thus, semi-quantitative comparative analysis can be conducted as has been previously demonstrated for sediments and house dust [29]. The precision of three SPE methods (C18_pH2, HLB_pH2, and WAX) was determined by calculating relative standard deviations (RSD) of individual DBPs among triplicate samples. While a few DBPs exhibited relatively poor precision (RSD > 30%), the best overall reproducibility was achieved for HLB_pH2 with a mean RSD of 13.3% (Fig. 1B), compared to 22.4% and 18.6% for C18_pH2 and WAX methods (Fig. S2). This is comparable to targeted DBP methods using surrogate standards (RSD 10%–12% for chlorinated nonylphenol) in drinking water [32]. Therefore, the DIPIC-Frag method could be applied for the comparative analysis of Br-DBPs. Considering the better coverage and reproducibility, the acidified HLB method is preferred for analyses of unregulated Br-DBPs.

When compounds derived by use of the five SPE methods were combined, using retention times and predicted formulae, a non-redundant list containing 553 Br-DBPs was established. Detected Br-DBPs exhibited variations in m/z (170.884–497.0278), retention times (2.4–26.2 min), and number of bromine atoms (1–3). It was found that 447 (81%) of the Br-DBPs contained only one bromine atom, which is different from brominated compounds detected in sediments from Lake Michigan, many of which contained multiple bromine atoms [29]. The relatively small number of bromine atoms observed in DBPs was consistent with the results of previous studies [13,15]. Abundances of peaks associated with Br-DBPs were distributed from 104 to 8.4 × 106 (Fig. S3), with about two orders of magnitude variation. Identifications of two of the most abundant Br-DBPs, bromophenol, and bromoacetic acid were successfully confirmed using commercially available, authentic standards. HAAs were among the most abundant Br-DBPs, but other Br-DBPs were detected with similar or even greater abundances than HAAs. In particular, a Br-DBP with predicted [M-X]- formula of CHSO3ClBr (8.4 × 106) (Fig. S4) was more abundant than HAAs (6.8 × 106). The nature of this abundant sulfur-containing DBP was confirmed, with an authentic standard, as a halogenated methanesulfonic acid (Fig. S3). The occurrence of this DBP in drinking water is consistent with the results of a recent study conducted on European waters, in which CHSO3ClBr, or bromochloromethanesulfonic acid, as well as six additional halogenated methanesulfonic acids were observed [33].

3.2. Proposed chemical structures of the most abundant DBPs

Despite variations in abundances of Br-DBPs, a limited number of high-abundance DBPs were detected with peak abundances greater than 106. In fact, of the 553 Br-DBPs, the 54 most abundant Br-DBPs contributed 46.3% of the total peak abundance (Fig. S4). Thirty-two of the 54 Br-DBPs were detected with the highest abundances in water samples enriched by HLB cartridges under pH < 2, compared to four other SPE methods. While greater ion abundance is not indicative of greater risk to public health because it does not consider toxic potency, the characterization of the structures of these more abundant Br-DBPs is an important task to begin the process of identifying unregulated Br-DBPs of potential concern.

Compared to direct infusion, high-resolution MS1 and MS2 spectra were acquired simultaneously by the use of DIPIC-Frag method. Due to the relatively small molecular masses (m/z < 400) of more abundant Br-DBPs, the searching space for possible formulae is relatively small, reducing the potential for false identifications. By combining fragment patterns and possible structures searched from public databases (e.g., ChemSpider™), structures for 40 of the 54 most abundant Br-DBPs were predicted (Table S2). For instance, the compound detected with m/z = 258.9249 was assigned as C8H4O5Br ([M−H]-), which is consistent with an almost identically abundant isotopic peak detected at m/z = 260.9228 (Δm = 1.99795 for the two stable Br isotopes) (Fig. S5). Next, we searched the molecular formula of the hydrocarbon analog (C8H6O5) against the ChemSpider™ to evaluate possible structures. Eighty-eight structures were found in the ChemSpider™ database. To further narrow the potential structure, the MS2 spectra were extracted from the corresponding DIA window (260 ± 2.5 Da). In addition to the Br fragment (m/z = 80.9152), two other high-intensity fragments (m/z = 172.9420 and 216.9323) were also detected, which were assigned as the sequential neutral losses of CO2 (Fig. S6). This clearly demonstrated two carboxylic acid moieties on the molecule. Among 88 tentative structures from the ChemSpider™, 11 structures contain two carboxylic acids, while 77 other structures containing one carboxylic acid or aldehyde were excluded. Among the 11 possible structures, six of them are the isomers of hydroxybenzoic acid containing a phenol group which should be the most possible structures. Similarly, by combining formula assignment ([M−H]-, C5O3BrCl), ChemSpider™ database searching, and MS2 spectra, we predicted the other Br-DBP at m/z = 256.8413 (Fig. S5) as halo-hydroxy-cyclopentenedione according to the neutral loss of –CO as detected in the MS2 spectra (Fig. S6). Then, we compared our results to previous nontarget analysis studies on DBPs. Among 54 high-intensity Br-DBPs, 33 of them have been reported in previous studies as shown in Table S2, including haloacetic acids, halo-hydroxy-cyclopentenedione, and halogenated hydroxybenzoic acid.

Many of the Br-DBPs are acidic or methoxylated compounds, which was demonstrated by neutral loss of CO2 or CH4O (Fig. S6). Eighteen of the Br-DBPs were predicted to be aromatic acids or phenols, representing the largest class of abundant Br-DBPs. This result is consistent with the results of FT-ICR-MS [27], in which aromatic acids or phenols were also observed at relatively great abundances. Considering the similarities of these DBP structures to those of lignin phenols [34], the most abundant plant component and one of the major precursors for DBPs, future studies are warranted to clarify the exact contributions of lignin phenols to DBPs.

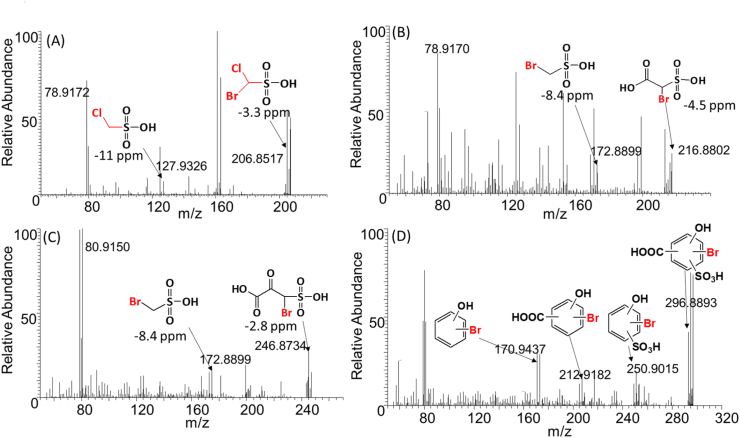

Several high-intensity, heteroatomic Br-DBPs-containing nitrogen or sulfur were predicted (Table S2 and Fig. 2). The most intense Br-DBP, CHSO3ClBr, was detected at intensities greater than those of HAAs (Fig. 2A). Several other sulfonic acid DBPs were also detected (Fig. 2B–D), but bromomethanesulfonic acid (CHSO3Br) was the only compound for which an authentic standard was available. Indeed, halomethanesulfonic acids have been reported in recent studies [35,33]. Several nitrogen-containing Br-DBPs, including C4H2NO3Br2 as predicted to be an oxazole carboxylic acid (Fig. S6), were also detected. Several classes of nitrogen-containing DBPs (N-DBPs), including halonitriles and haloamides, have been observed previously in drinking water [9,7,10,36], but those structures were different from the N-DBPs observed during the present study. These sulfur- or nitrogen-containing DBPs have not been observed during previous untargeted screening studies that used FT-ICR-MS [27,14,15], which further indicated complementary advantages of the FT-ICR and DIPIC-Frag methods. Since N- and S-containing DBPs have been suggested to exhibit greater toxic potencies than purely carbonaceous DBPs (C-DBPs) [9], the relatively great abundances of heteroatomic DBPs detected during the present study indicated that there is a potential risk associated with these DBPs.

Fig. 2.

MS–MS spectra for most intense sulfonic acid DBPs. Panels A–D represent MS2 spectra and the proposed structures derived from them. Positions of bromine (Br) atoms, sulfonic acid, carboxylic acid, or hydroxyl groups in compounds from panel B–D could not be determined exactly. Y-axis is peak abundance (%) relative to the largest peak.

3.3. Comparison of high-abundance Br-DBPs in monthly samples

Occurrences of the 54 most abundant, unregulated Br-DBPs were further analyzed in raw, clear well, and finished water collected over 12 months. While the most abundant Br-DBPs varied among stages of treatment and seasons, these 54 Br-DBPs were detected with relatively great frequencies (53/54, 98.1%) (Table S3) in finished water collected monthly. Notably, 52 of 54 (96.3%) Br-DBPs were detected in clear well water, even though only relatively small pre-chlorination dosages were applied prior to the clear well (0.46 ± 0.17 mg/L, compared to 2.0 ± 0.23 mg/L as the post-chlorine dose). The detection of most Br-DBPs in clear well water indicated the formation of Br-DBPs even at lesser chlorination dosages. This is consistent with the results of a previous study, in which THMs, bromo-acids, and other halogenated DBPs were also detected after pre-chlorination during treatment at a DWTP in Israel [19]. Peak abundances of these 54 Br-DBPs showed large variations with several orders of magnitude difference, ranging from not being detected (ND) to an ion abundance of 1.64× 107 in clear well water and from ND to 1.24 × 107 in finished water (Table S3).

A Spearman’s correlation matrix was used to explore co-occurrences of Br-DBPs based on peak intensities detected in clear well and finished waters during the year (Fig. 3A). Most of the relationships were positive, which indicated similar trends through the treatment process and/or similar monthly trends in the abundances of unregulated Br-DBPs. Positive correlations were still observed when only finished water was included in the correlation analysis (Fig. S7), albeit with lesser significance partly due to smaller sample sizes. Based on the correlation matrix, three clusters of positively correlated Br-DBPs were identified (Fig. 3A). Isomers and structural analogs were often placed into the same cluster. In the blue square (Fig. 3A) are ions of two trihalo-HCDs (C5O3Cl2Br and C5O3ClBr2) as well as two dihalo-HCDs with the formula C5HO3ClBr. A significantly positive relationship (R2 = 0.95, P = 1.89e-14) was observed between abundances of C5O3Cl2Br and C5O3ClBr2 (Fig. 3B). In the red square (Fig. 3A) are four dihalo-hydroxybenzoic acids, two with the formula C7H3O3ClBr, and two with the formula C7H3O3Br2 (R2 = 0.78–0.99, P ranges from 1.27e-8 to ≤2.20e-16) (Fig. S8). The observation of strong positive relationships between analogs was not surprising since analogs generally form via the same reaction route and precursor compounds [37,38,33]. Also, the red square was 7 of the 10 sulfur-containing DBPs with R2 values ranging from 0.11 to 0.99 (P = 0.14 to <<0.001) (Table S4). Limited information is available on formation mechanisms and precursor compounds for sulfur-containing DBPs. The positive relationships found here indicate that they may form from common precursor compounds. Further studies to identify the precursor compounds of sulfur-containing DBPs are warranted.

Fig. 3.

Correlations between Br-DBPs. (A) Spearman’s correlation matrix is based on ion intensities of 54 Br-DBPs detected in clear well and finished water at 11 monthly time points. Representative compounds are indicated, and a full list can be found in Table S5. The color scale indicated in the legend represents the value of the Spearman correlation coefficient between Br-DBPs. Examples are shown for (B) a strong positive correlation between two trihalo-HCDs analogs (red circles) and (C) a weak negative correlation between C7H6O6Br and C7H3O3ClBr. Red points represent ion intensities detected in clear well water, blue points represent ion intensities detected in finished water, and the dashed lines represent the 95% confidence interval of the Spearman correlation coefficient.

Unexpectedly, poor or even negative correlations were observed between some Br-DBPs, as highlighted by black rectangles in Fig. 3A. An example is shown in Fig. 3C between ions of C7H6O6Br and C7H3O3ClBr (R2 = 0.10, slope = −0.16, P = 0.16). Further investigation of the relationship showed that the poor trend was driven by the low abundance of C7H6O6Br in clear well water contrasted with the small abundance of C7H3O3ClBr in finished water (Fig. 3C). These results indicated that some Br-DBPs, e.g., C7H3O3ClBr, are degraded or removed as water is processed from the clear well to finished water. Indeed, a previous study reported aromatic DBPs, including halogenated hydroxyl-benzoic acids (e.g., C7H3O3ClBr), as intermediate DBPs to decompose and form smaller DBPs [39].

3.4. Fates of Br-DBPs related to chemical properties

Soft clustering analysis was used to investigate the fates of Br-DBPs through the treatment process, and three general trends were identified (Fig. 4A). Cluster I Br-DBPs, such as C5O3Cl2Br, increased in abundance from raw to clear well water, then decreased in finished water. Cluster II Br-DBPs, as exemplified by C8H4O5Br, increased greatly from raw to clear well water and then continued to increase in finished water, albeit at a lesser rate. The majority of investigated Br-DBPs (33/54), including all sulfur-containing Br-DBPs, were classified as cluster III, which exhibited a modest increase from raw to clear well water, followed by a greater increase in finished water. The decrease of cluster I but increase of cluster II and III Br-DBPs from clear well to finished water suggested the possibility that cluster I Br-DBPs could be converted to other Br-DBPs, such as cluster II and III Br-DBPs, with the application of the greater, post-chlorine dosage. For example, the trihalo-HCD (C5O3Cl2Br, as shown in Fig. 4B) was classified as cluster I, and its average intensity decreased from 5.1e6 in clear well water to 6.6e5 in finished water (P < 0.01). Results of previous studies have shown that, with the increased chlorine contact time, trihalo-HCDs form rapidly upon chlorination and then degrade to DBPs of lesser molecular mass, such as THMs or HAAs [40,41]. Identification of these trends supports the dynamic vision model described by Li and Mitch [42], in which the percent contribution of DBPs to total organic halide shifts as the water interacts with chlorine longer and moves through treatment processes and distribution systems.

Fig. 4.

Trends of Br-DBPs through the drinking water treatment process. (A) Three trend clusters were identified for Br-DBPs based on the change in ion intensity. Each colored line represents one of the 54 unregulated Br-DBPs. (B) Representative compounds are shown for each of the three clusters defined in (A). Data from eleven months are included to highlight that these trends were consistent throughout the year. The upper and lower edges of the box represent the third and first quartiles, respectively, and the line across the middle of the box represents the median.

The chemical diversity of unregulated Br-DBPs provides a unique chance to investigate the potential effects of chemical properties on formation dynamics among stages of treatment. No significant differences were observed between molecular masses, numbers of carbon atoms, or number of bromine atoms for Br-DBPs of each cluster. Instead, the ratio of Br/C in cluster III Br-DBPs was greater compared to that of clusters I and II Br-DBPs (P = 0.02) (Fig. S9). In addition, compared to cluster I, Br-DBPs in cluster II and III had greater ratios of O/C (P = 0.01 and 0.06, respectively) (Fig. S9). Notably, all 10 sulfur-containing Br-DBPs were grouped in cluster III, demonstrating their persistence during disinfection. Thus, the results of the study presented here confirmed that, in drinking water, Br-DBPs can exhibit various reaction dynamics closely related to their chemical properties.

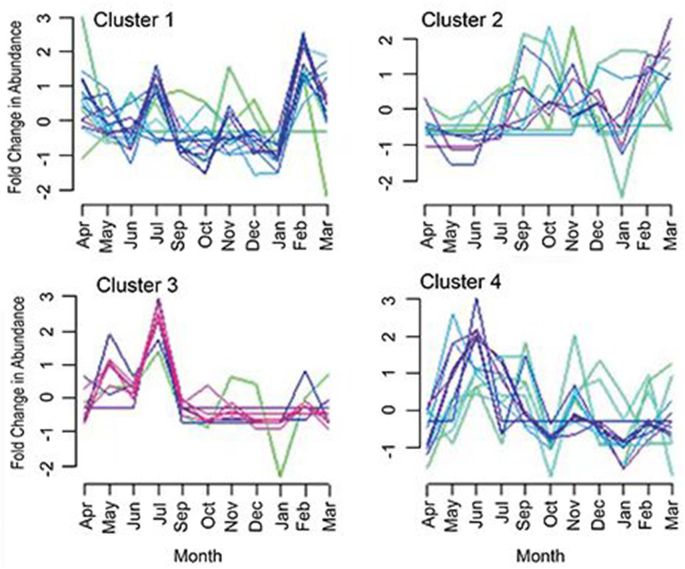

3.5. Monthly variations of Br-DBPs are not correlated to NOM

When monthly trends of intensities of Br-DBPs in finished water were investigated by soft clustering (Fig. 5), four diverse trends were observed, and the concentrations of three of four clusters (clusters 1, 3, and 4) had common peaks in abundance in summer (i.e., June or July), with decreased abundance in fall and winter for clusters 3 and 4. Similarities in monthly trends for most Br-DBPs are supported by their positive correlations (Fig. 3A), which indicate common factors driving their co-occurrences.

Fig. 5.

Four temporal trends identified by soft clustering analysis for the detection of 54 unregulated Br-DBPs in finished water over 11 months (April to March, Excl. August).

Since NOM is known to provide precursors for the formation of DBPs, the same samples of raw, clear well, and finished water were analyzed for NOM by direct infusion Orbitrap MS. A total of 394 peaks were assigned predicted formulas, with CHO NOM as the major class (316 compounds), which contributed to 86.6% ± 2.2% of total NOM ion abundance (Fig. S10). Detections of CHO compounds as the major class of NOM are consistent with the results of previous studies [43,44]. Sulfur-containing NOM was detected at relatively great abundances, with 11 CHOS compounds (4.5% ± 2.4%) and 56 CHOSN compounds (8.5% ± 0.7%). Ubiquitous occurrences of sulfur-containing NOM compounds, detection of sulfur-containing Br-DBPs at relatively great abundances, together with reported toxic potencies of heteroatomic DBPs, suggest that sulfur-containing DBPs are compounds of emerging concern [9,33].

Soft clustering analysis was used to identify four trends in the monthly variation of abundances of NOM (Fig. S11). All four clusters of NOM peaked in December, showing distinct trends from Br-DBPs. Correlations between individual Br-DBPs and individual compounds of NOM were further explored. A positive correlation between C7H6O6Br and NOM was observed for > 50% of NOM with O/C ratio > 0.5 and H/C ratio < 1 (Fig. S12A). This is consistent with the results of a recent bench-scale study in which NOM molecules with high O/C ratios and low H/C ratios were found to have the greatest potential to form chlorinated THM and HAA [28]. However, significant correlations were not observed between any other Br-DBPs and NOM (Fig. S12B), especially when P values were adjusted for multiple comparisons. Previous studies have documented the effects of NOM on the spatial distribution of regulated DBPs [17,28,45]. In those studies, samples were collected from various locations, and a larger variation of NOM was observed with spatial distributions of DBPs. In contrast, for monthly trends of Br-DBPs in drinking water collected from the same location, the magnitude of variation of NOM is minor, and thus might not be a major driving factor for monthly variations of Br-DBPs. Overall, NOM is not a strong predictor of monthly variations of unregulated Br-DBPs.

3.6. Monthly variations of Br-DBPs are primarily correlated to TBr

Correlations were further investigated between Br-DBPs in finished water and monthly measured raw water parameters, including river level, turbidity, color, temperature, UV254, and UVT, as well as applied doses of chlorine (pre- and post-chlorine dose) (Figs. S13–S14). With the exception of temperature, these parameters exhibited very few strongly significant correlations (α = 0.01) with individual Br-DBPs. At α = 0.05, temperature demonstrated significantly positive correlations with seven Br-DBPs, but at α = 0.01, only three of these correlations remained significant (Fig. S13). Temperature is a variable often identified as a strong predictor for occurrences of regulated DBPs [17,46,20], but as temperature was only significantly correlated with 3 of 54 (5.6%) Br-DBPs at α = 0.01, it should not be considered the major factor driving the monthly variation of most Br-DBPs in this study.

It was expected that the concentration of bromide (Br−) in raw water would correlate well with the detection of Br-DBPs in finished water. However, the concentration of Br− in raw water at the studied DWTP was particularly low, and traditional ion chromatography detection (detection limit is approximately 0.04 mg/L) was not sufficiently sensitive to quantify Br−. Thus, a more sensitive ICP-MS was adopted, and small concentrations (0.013–0.038 mg/L) of TBr were measured in samples of raw water. As inorganic bromide is the major bromine species in raw water [47], the TBr in raw water measured by ICP-MS should be mainly contributed by bromide. With this result, TBr in raw water was not found to be significantly correlated with any investigated, unregulated Br-DBPs at α = 0.05.

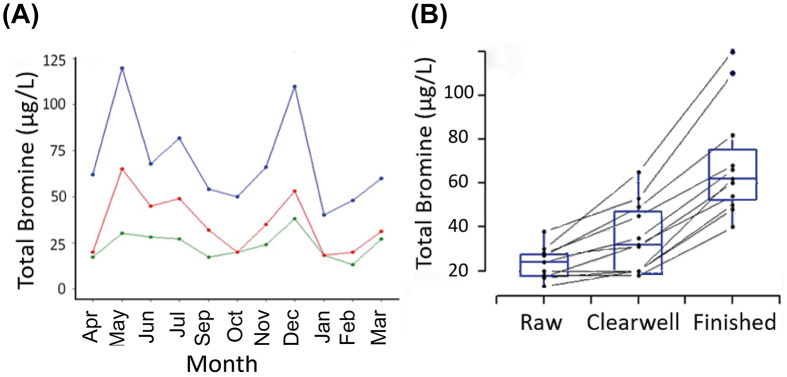

With ICP-MS, only TBr could be measured in treated waters since Br− and other inorganic and inorganic bromine species are converted to elemental bromine for the TBr analysis. Interest was created in exploring TBr in more depth due to the unexpected observation that it increased through the treatment process (P = 1.98e-6) (Fig. 6). Concentrations of bromine increased from 0.013 to 0.038 mg/L in raw water to 0.018–0.065 mg/L (P < 0.001) in clear well water, then further increased to 0.040–0.120 mg/L (P < 0.001) in finished water (Fig. 6B). These findings were unexpected because Br− in drinking water is suggested to be present primarily due to natural background concentrations in source waters; thus, concentrations of TBr among stages of treatment units should be similar. Concentrations of TBr in raw water sampled in the present study are 3–10 fold less than those reported for Br− in other regions, e.g., 0.095 ± 0.013 mg/L (mean ± SD) in the US drinking water sources and as much as 0.09 mg/L in a Saskatchewan lake located approximately 300 km from the DWTP studied here [48]. While the exact source of additional bromine throughout the treatment process remains unknown, it must be related to the disinfection process since the only treatment step between clear well and finished water is post-chlorination. Bromine (Br2), bromine chloride (BrCl), and other brominated compounds are known to occur as impurities in chlorine gas used for the disinfection of drinking water, and current NSF 60 criteria specify 1 mg/L bromine as the single product allowable concentration for any reagents used in the production of chlorine disinfectants (chemicals). Indeed, a recent study reported the ubiquitous occurrences of bromine impurities in hypochlorite solutions applied to the Canada DWTPs [49]. Similar to our study, elevated bromate levels were observed in treated waters collected from 15 Canada DWTPs, albeit with lower levels (0.5–11.2 μg/L) than in the present study (22–90 μg/L). The acceptable amount of bromine impurities is small, but might be sufficient to affect concentrations of bromine in water at the DWTP studied here, where background concentrations of TBr in raw water were particularly small.

Fig. 6.

Concentrations of TBr in water collected on a monthly basis at three stages of water treatment. (A) The results are shown for raw (green), clear well (red), and finished water (blue). (B) Monthly trends demonstrate that TBr consistently increased across stages of treatment throughout the year. The upper and lower edges of the box represent the third and first quartiles, respectively, and the line across the middle of the box represents the median.

Motivated by this observation, potential correlations between Br-DBPs and concentrations of TBr in finished water, rather than raw water, were explored. Significant associations were observed for nine Br-DBPs (Fig. S13). When data from clear well and finished stages of treatment were used to increase the sample size and statistical power, the majority of Br-DBPs (34/54) were significantly correlated to concentrations of TBr at α = 0.05, with 14 of those significant at α = 0.01 and 12 significant at α = 0.001 (Fig. 7A). For example, the sulfur-containing Br-DBP CHO3SClBr was significantly and positively correlated with concentrations of TBr (R2 = 0.59, P = 2.8e-5) (Fig. 7B). The positive correlation was preserved when finished and clear well data were considered separately (Fig. 7C). While previous studies have documented the effects of concentrations of Br− on the formation of Br-DBPs in both laboratory and field studies, this is the first field study to observe that concentrations of TBr, not background concentrations of Br− in source water, are a major driving factor for monthly variations of concentrations of most unregulated Br-DBPs.

Fig. 7.

Correlations between concentrations of TBr at the clear well and finished stages and abundances of Br-DBP ions. (A) Distribution of retention times and m/z values for 54 abundant Br-DBPs, with the significance (P value) of the correlation to TBr represented by color. The relationship between CHO3SClBr and TBr is shown with (B) one linear model incorporating both clear well and finished data (R2 = 0.59, P = 2.8e-5), and (C) two linear models that consider clear well and finished water data separately (clear well: R2 = 0.51, P = 0.013; finished: R2 = 0.41, P = 0.034). Red points and the red line represent data from the clear well, and blue points and the blue line represent data from finished water, with 95% confidence intervals shown in grey.

4. Conclusions

Unregulated Br-DBPs are of concern since multiple studies have documented their increased toxicities compared to regulated DBPs. The HRMS-based, non-targeted chemical analysis provides a new strategy to investigate the occurrence and even spatial and temporal trends of unregulated Br-DBP concentrations. In the present study, the largest plant-scale list of Br-DBPs was tentatively identified, and then chemical-specific temporal trends of unregulated Br-DBPs were reported for the first time. The observation that concentrations of TBr increased through the treatment process and the hypothesis that it may be a major factor driving monthly variation of unregulated Br-DBPs is significant at two levels: (i) reduction of concentrations of TBr might be the most effective way to decrease concentrations of Br-DBPs; (ii) if Br is added during disinfection from impurities of disinfection reagents, there may be an early process modification that could reduce concentrations of many Br-DBPs. However, this conclusion might be region-specific. For other regions where background concentrations of Br are greater, Br introduced during disinfection might not be a significant factor in determining the formation of Br-DBPs. Further application of full-scan chemical analysis strategies to more DWTPs for investigation of spatial and temporal trends of Br-DBPs should be of great interest.

There are several limitations of the current study. First, while one of the most abundant detected Br-DBP, bromomethanesulfonic acid, was confirmed with authentic standards, the majority of detected Br-DBPs could not be verified due to the lack of authentic standards. Extensive efforts are warranted in the future to synthesize standards and confirm the tentatively identified Br-DBPs. Second, the dynamic formation of Br-DBPs is closely related to their chemical properties, but the exact reaction pathways should be investigated in the future.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have declared no conflicts of interests.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Discovery Grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada of Canada (Project # 326415-07) and a grant from the Western Economic Diversification Canada (Projects # 6578, 6807, and 000012711). Prof. Giesy was supported by the Canada Research Chair program, and the 2014 “High Level Foreign Experts” (#GDT20143200016) program funded by the State Administration of Foreign Experts Affairs, the P.R. China to Nanjing University, the Einstein Professor Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and a Distinguished Visiting Professorship in the School of Biological Sciences of the University of Hong Kong. Prof. Peng was supported by a Discovery Grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada of Canada (Project # RGPIN-2018-06511) and University of Toronto Start-up Funds.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eehl.2022.06.002.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Farkas L., Lewin M., Bloch R. The reaction between hypochlorite and bromides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1941;71(6):1988–1991. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richardson S.D., Thruston A.D., Caughran T.V., Chen P.H., Collette T.W., Floyd T.L. Identification of new drinking water disinfection byproducts formed in the presence of bromide. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1999;33(19):3378–3383. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richardson S.D., Plewa M.J., Wagner E.D., Schoeny R., DeMarini D.M. Occurrence, genotoxicity, and carcinogenicity of regulated and emerging disinfection by-products in drinking water: a review and roadmap for research. Mutat. Res. Rev. Mutat. Res. 2007;636(1–3):178–242. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang Y., Komaki Y., Kimura S.Y., Hu H.Y., Wagner E.D., Marinas B.J., et al. Toxic impact of bromide and iodide on drinking water disinfected with chlorine or chloramines. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014;48(20):12362–12369. doi: 10.1021/es503621e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bull R.J., Reckhow D.A., Li X.F., Humpage A.R., Joll C., Hrudey S.E. Potential carcinogenic hazards of non-regulated disinfection by-products: haloquinones, halo-cyclopentene and cyclohexene derivatives, N-halamines, halonitriles, and heterocyclic amines. Toxicology. 2011;286(1–3):1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeong C.H., Wagner E.D., Siebert V.R., Anduri S., Richardson S.D., Daiber E.J., et al. Occurrence and toxicity of disinfection byproducts in European drinking waters in relation with the HIWATE epidemiology study. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012;46(21):12120–12128. doi: 10.1021/es3024226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Plewa M.J., Wagner E.D., Jazwierska P., Richardson S.D., Chen P.H., McKague A.B. Halonitromethane drinking water disinfection byproducts: chemical characterization and mammalian cell cytotoxicity and genotoxicity. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004;38(1):62–68. doi: 10.1021/es030477l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li J.H., Moe B., Vemula S., Wang W., Li X.F. Emerging disinfection byproducts, halobenzoquinones: effects of isomeric structure and halogen substitution on cytotoxicity, formation of reactive oxygen species, and genotoxicity. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016;50(13):6744–6752. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b05585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muellner M.G., Wagner E.D., McCalla K., Richardson S.D., Woo Y.T., Plewa M.J. Haloacetonitriles vs. regulated haloacetic acids: are nitrogen-containing DBPs more toxic? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007;41(2):645–651. doi: 10.1021/es0617441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Plewa M.J., Muellner M.G., Richardson S.D., Fasanot F., Buettner K.M., Woo Y.T., et al. Occurrence, synthesis, and mammalian cell cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of haloacetamides: an emerging class of nitrogenous drinking water disinfection byproducts. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008;42(3):955–961. doi: 10.1021/es071754h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang M.T., Zhang X.R. Comparative developmental toxicity of new aromatic halogenated DBPs in a chlorinated saline sewage effluent to the marine polychaete platynereis dumerilii. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013;47(19):10868–10876. doi: 10.1021/es401841t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang X.R., Echigo S., Minear R.A., Plewa M.J. Characterization and comparison of disinfection by-products from using four major disinfectants. Abstr. Pap. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;217:U736. U736. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang G., Jiang P., Li X.F. Mass spectrometry identification of N-chlorinated dipeptides in drinking water. Anal. Chem. 2017;89(7):4204–4209. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b00228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang H.F., Zhang Y.H., Shi Q., Hu J.Y., Chu M.Q., Yu J.W., et al. Study on transformation of natural organic matter in source water during chlorination and its chlorinated products using ultrahigh resolution mass spectrometry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012;46(8):4396–4402. doi: 10.1021/es203587q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang H.F., Zhang Y.H., Shi Q., Zheng H.D., Yang M. Characterization of unknown brominated disinfection byproducts during chlorination using ultrahigh resolution mass spectrometry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014;48(6):3112–3119. doi: 10.1021/es4057399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang M.T., Zhang X.R. Current trends in the analysis and identification of emerging disinfection byproducts. Trends Environ Anal Chem. 2016;10:24–34. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dominguez-Tello A., Arias-Borrego A., Garcia-Barrera T., Gomez-Ariza J.L. Seasonal and spatial evolution of trihalomethanes in a drinking water distribution system according to the treatment process. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2015;187(11) doi: 10.1007/s10661-015-4885-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim J. Fate of THMs and HAAs in low TOC surface water. Environ. Res. 2009;109(2):158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richardson S.D., Thruston A.D., Rav-Acha C., Groisman L., Popilevsky I., Juraev O., et al. Tribromopyrrole, brominated acids, and other disinfection byproducts produced by disinfection of drinking water rich in bromide. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003;37(17):3782–3793. doi: 10.1021/es030339w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodriguez M.J., Serodes J.B. Spatial and temporal evolution of trihalomethanes in three water distribution systems. Water Res. 2001;35(6):1572–1586. doi: 10.1016/s0043-1354(00)00403-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Serrano M., Montesinos I., Cardador M.J., Silva M., Gallego M. Seasonal evaluation of the presence of 46 disinfection by-products throughout a drinking water treatment plant. Sci. Total Environ. 2015;517:246–258. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.02.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen C., Zhang X.J., Zhu L.X., Liu J., He W.J., Han H.D. Disinfection by-products and their precursors in a water treatment plant in North China: seasonal changes and fraction analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2008;397(1–3):140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uyak V., Ozdemir K., Toroz I. Seasonal variations of disinfection by-product precursors profile and their removal through surface water treatment plants. Sci. Total Environ. 2008;390(2–3):417–424. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2007.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shanks C.M., Serodes J.B., Rodriguez M.J. Spatio-temporal variability of non-regulated disinfection by-products within a drinking water distribution network. Water Res. 2013;47(9):3231–3243. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2013.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peng H., Chen C.L., Saunders D.M.V., Sun J.X., Tang S., Codling G., et al. Untargeted identification of organo-bromine compounds in lake sediments by ultrahigh-resolution mass spectrometry with the Data-Independent Precursor Isolation and Characteristic Fragment method. Anal. Chem. 2015;87(20):10237–10246. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b01435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peng H., Chen C.L., Cantin J., Saunders D.M.V., Sun J.X., Tang S., et al. Untargeted screening and distribution of organo-bromine compounds in sediments of take Michigan. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016;50(1):321–330. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b04709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gonsior M., Schmitt-Kopplin P., Stavklint H., Richardson S.D., Hertkorn N., Bastviken D. Changes in dissolved organic matter during the treatment processes of a drinking water plant in Sweden and formation of previously unknown disinfection byproducts. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014;48(21):12714–12722. doi: 10.1021/es504349p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang X., Zhang H.F., Zhang Y.H., Shi Q., Wang J., Yu J.W., et al. New insights into trihalomethane and haloacetic acid formation potentials: correlation with the molecular composition of natural organic matter in source water. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017;51(4):2015–2021. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b04817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peng H., Saunders D.M.V., Sun J.X., Jones P.D., Wong C.K.C., Liu H.L., et al. Mutagenic azo dyes, rather than flame retardants, are the predominant brominated compounds in house dust. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016;50(23):12669–12677. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b03954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schymanski E.L., Jeon J., Gulde R., Fenner K., Ruff M., Singer H.P., et al. Identifying small molecules via high resolution mass spectrometry: communicating confidence. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014;48(4):2097–2098. doi: 10.1021/es5002105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang L.Y., Chen X.M., She Q.H., Cao G.M., Liu Y.D., Chang V.W.C., Tang C.Y. Regulation, formation, exposure, and treatment of disinfection by-products (DBPs) in swimming pool waters: a critical review. Environ. Int. 2018;121:1039–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fan Z.L., Hu J.Y., An W., Yang M. Detection and occurrence of chlorinated byproducts of bisphenol A, nonylphenol, and estrogens in drinking water of China: comparison to the parent compounds. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013;47(19):10841–10850. doi: 10.1021/es401504a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zahn D., Fromel T., Knepper T.P. Halogenated methanesulfonic acids: a new class of organic micropollutants in the water cycle. Water Res. 2016;101:292–299. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2016.05.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hua G.H., Kim J., Reckhow D.A. Disinfection byproduct formation from lignin precursors. Water Res. 2014;63:285–295. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2014.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gonsior M., Mitchelmore C., Heyes A., Harir M., Richardson S.D., Petty W.T., Wright D.A., Schmitt-Kopplin P. Bromination of marine dissolved organic matter following full scale electrochemical ballast water disinfection. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015;49(15):9048–9055. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b01474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shah A.D., Mitch W.A. Halonitroalkanes, halonitriles, haloamides, and N-nitrosamines: a critical review of nitrogenous disinfection byproduct formation pathways. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012;46(1):119–131. doi: 10.1021/es203312s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pan Y., Zhang X.R. Four groups of new aromatic halogenated disinfection byproducts: effect of bromide concentration on their formation and speciation in chlorinated drinking water. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013;47(3):1265–1273. doi: 10.1021/es303729n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pan Y., Wang Y., Li A.M., Xu B., Xian Q.M., Shuang C.D., et al. Detection, formation and occurrence of 13 new polar phenolic chlorinated and brominated disinfection byproducts in drinking water. Water Res. 2017;112:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2017.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang J.Y., Zhang X.R., Zhu X.H., Li Y. Removal of intermediate aromatic halogenated DBPs by activated carbon adsorption: a new approach to controlling halogenated DBPs in chlorinated drinking water. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017;51(6):3435–3444. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b06161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhai H.Y., Zhang X.R., Zhu X.H., Liu J.Q., Ji M. formation of brominated disinfection byproducts during chloramination of drinking water: new polar species and overall kinetics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014;48(5):2579–2588. doi: 10.1021/es4034765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhai H.Y., Zhang X.R. Formation and decomposition of new and unknown polar brominated disinfection byproducts during chlorination. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011;45(6):2194–2201. doi: 10.1021/es1034427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li X.F., Mitch W.A. Drinking water disinfection byproducts (DBPs) and human health effects: multidisciplinary challenges and opportunities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018;52(4):1681–1689. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.7b05440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koch B.P., Dittmar T., Witt M., Kattner G. Fundamentals of molecular formula assignment to ultrahigh resolution mass data of natural organic matter. Anal. Chem. 2007;79(4):1758–1763. doi: 10.1021/ac061949s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang H.F., Zhang Y.H., Shi Q., Ren S.Y., Yu J.W., Ji F., et al. Characterization of low molecular weight dissolved natural organic matter along the treatment trait of a waterworks using Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry. Water Res. 2012;46(16):5197–5204. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ye B.X., Wang W.Y., Yang L.S., Wei J.R., E X.L. Factors influencing disinfection by-products formation in drinking water of six cities in China. J. Hazard Mater. 2009;171(1–3):147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.05.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Obolensky A., Singer P.C. Development and interpretation of disinfection byproduct formation models using the Information Collection Rule database. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008;42(15):5654–5660. doi: 10.1021/es702974f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shi H.L., Adams C. Rapid IC–ICP/MS method for simultaneous analysis of iodoacetic acids, bromoacetic acids, bromate, and other related halogenated compounds in water. Talanta. 2009;79:523–527. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2009.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.VanBriesen JM. Potential Drinking Water Effects of Bromide Discharges from Coal-Fired Electric Power Plants.

- 49.Anranda-Rodriguez R., Lemieux F., Jin Z.Y., Hantiw J., Tugulea A.M. Challenges for water treatment plants: potential contribution of hypochlorite solutions to bromate, chlorate, chlorite and perchlorate in drinking water. J. Water. Supply. Res. T. 2017;66:621–631. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.