Abstract

Research about farmland pollution by heavy metals/metalloids in China has drawn growing attention. However, there was rare information on spatiotemporal evolution and pollution levels of heavy metals in the major grain-producing areas. We extracted and examined data from 276 publications between 2010 and 2021 covering five major grain-producing regions in China from 2010 to 2021. Spatiotemporal evolution characteristics of main heavy metals/metalloids was obtained by meta-analysis. In addition, subgroup analyses were carried out to study preliminary correlations related to accumulation of the pollutants. Cadmium (Cd) was found to be the most prevailing pollutant in the regions in terms of both spatial distribution and temporal accumulation. The Huang-Huai-Hai Plain was the most severely polluted. Accumulation of Cd, mercury (Hg) and copper (Cu) increased from 2010 to 2015 when compared with the 1990 background data. Further, the levels of five key heavy metals (Cd, Cu, Hg, lead [Pb] and zinc [Zn]) showed increasing trends from 2016 to 2021 in all five regions. Soil pH and mean annual precipitation had variable influences on heavy metal accumulation. Alkaline soil and areas with less rainfall faced higher pollution levels. Farmlands cropped with mixed species showed smaller effect sizes of heavy metals than those with single upland crop, suggesting that mixed farmland use patterns could alleviate the levels of heavy metals in soil. Of various soil remediation efforts, farmland projects only held a small market share. The findings are important to support the research of risk assessment, regulatory development, pollution prevention, fund allocation and remediation actions.

Keywords: Heavy metal, Agricultural soil, Soil pollution, Meta-analysis, Spatiotemporal evolution

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Spatiotemporal evolution of 8 metals in 5 major ag-regions in China was obtained.

-

•

Increasing trends of Cd, Hg, Pb, Cu, and Zn were found in all 5 regions from 1990 to 2021.

-

•

Cadmium was not only the most detected metal but showed the highest increasing trend.

-

•

Huanghuaihai Plain was the most polluted region with heavy metals/metalloids.

-

•

Mixed farmland use patterns may alleviate soil accumulation of heavy metals.

1. Introduction

Heavy metals in farmland have drawn growing attention for their potential threat to human health and ecosystem safety [[1], [2], [3]]. China has been confronted with growing challenges to protect its farmland from heavy metals pollution since 1990 [4]. In 2014, the Ministry of Environmental Protection of the People’s Republic of China (MEP, Currently the Ministry of Ecology and Environment [MEE]) and the Ministry of Land and Resources of China (MLR, currently the Ministry of Natural Resources [MNR]) published Report of National Soil Pollution Investigation [5]. This document reported that 16.1% of the farmland soil exceeded the soil quality standards (GB 15168-1995). Among the polluted sites, 82.8% were contaminated by eight heavy metals/metalloids, including cadmium (Cd), mercury (Hg), arsenic (As), lead (Pb), chromium (Cr), copper (Cu), nickel (Ni), and zinc (Zn). To control the risk of soil pollution and protect the quality and safety of agricultural products, China upgraded its national farmland soil quality standards from GB 15168-1995 [6] to GB 15168-2018 [7]. The previous standard (GB 15168-1995) was set for all kinds of soil and named “Environmental quality standard for soils”. It classified the soil quality into three levels based on the heavy metal content (the most polluted as Level 3). The new standard (GB 15168-2018) was named “Soil environmental quality—Risk control standard for soil contamination of agricultural land”, and mainly focused on farmland protection and food safety. The new standard sets risk screening values (corresponding to Level 2 in the previous standard) and risk intervention values of heavy metals for different crop lands. Therefore, systematic investigation and updates on the spatiotemporal evolution of heavy metals in China’s farmland are highly in need.

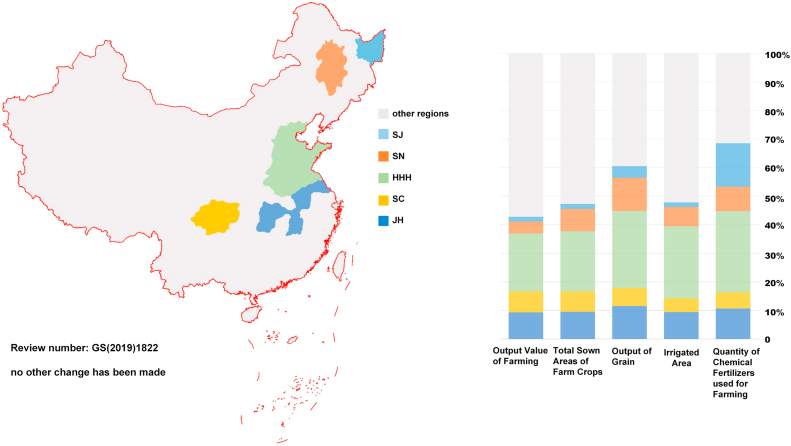

Some previous studies in China have been focused on heavy metals in farmland, they have been confined with limited scopes and relatively small study areas, including Tangshan, Hebei [8], Xuzhou, Jiangsu [9], and Beijing [10]. Given the massive scale and diverse agricultural practices in China, there are growing calls for information in large spatial scales and extended span of time. To this end, Huang et al. [11] attempted to find out the status of agricultural soil pollution by heavy metals in China using a meta-analysis approach, and Yuan et al. [12] systematically compared the heavy metal pollution in farmland and urban soils in China over the past 20 years. In China, major grain-producing regions are playing important roles in food production, large-scale agriculture, water and fertilizer application, etc., and should be systematically investigated. San-Jiang Plain (referred as SJ), Song-Nen Plain (SN), Huang-Huai-Hai Plain (HHH), Sichuan Basin (SC), and the area covering the middle of Yangtze River and Jiang-Huai Region (JH) are five important major grain-producing regions [13,14] (Fig. 1). According to China Statistical Yearbook 2020 [15], the five major regions were responsible for 42.75% of the total farming output in China, 47.30% of sown area of crops, 60.50% of grain output, 47.80% of irrigated area and 68.52% chemical fertilizers usage. The background values of heavy metals, soil pH, precipitation, temperature, and farmland use pattern in these five regions varied greatly. However, correlations between those preliminary factors and heavy metals pollution were still unclear. In the previous studies, national average values were often adopted as the only standard without consideration of the discrepancies on background heavy metal between regions [11,12]. The regional heavy metals background values from The China Environmental Background Values of Soil (published in 1990) [16] can be used to give a more region-specific spatiotemporal study. The region-specific investigation can help us understand more on risk assessment, regulatory development, pollution prevention, fund allocation and remediation actions for these major grain-producing regions.

Fig. 1.

Location of five major grain producing areas and their contributions to the total agricultural production in China. SJ, Sanjiang Plain; SN, Songnen Plain; HHH, Huanghuaihai Plain; SC, Sichuan Basin; JH, an area covering middle of Yangtze River and Jianghuai Region.

Meta-analysis is a method to obtain a general understanding of the effect size against preliminary correlations [17]. Moreover, it examines differences between groups per subgroup analyses [18]. In recent years, meta-analysis has been widely used in the ecology and agriculture fields [[19], [20], [21], [22], [23]]. Meta-analysis was used to analyze the situation of heavy metal pollution in China in a large-scale and extended span of time [11,12,24]. These studies focused on using this approach to analyze the bias of publications and data sensitivity. They used different pollution indices to illustrate the heavy metal pollution levels, and compared the mean heavy metal values with current standards. However, different pollution indices had different thresholds. In addition, most of previous publications only focused on reporting mean concentration values with standard deviations of heavy metals without normalized analysis. Meta-analysis can demonstrate overall status of heavy metal pollution using a statistically uniform threshold (effect size) with both means and standard deviations [25]. Abundant data about heavy metals in the Chinese farmland has been published in the last two decades. However, there was no thorough study on the spatiotemporal evolution of heavy metals in these major grain-producing regions. To fulfill this knowledge gap, meta-analysis can be applied to systematically investigate the level and evolutional trend of heavy metal pollution in these regions.

The objectives of this work were to: 1) provide an updated overview on the spatiotemporal evolution of heavy metal pollution in the five major grain-producing regions over the past 12 years through meta-analysis; 2) examine the evolution trends of eight major heavy metals between 2010–2015 and 2016–2021; 3) explore the relationship between some preliminary factors and the status of heavy metals by computing data of disparate subgroups; 4) summarize the policies and measures against heavy metal pollution in China. In general, the findings will provide an update on the status of heavy metal pollution on a large-scale in China’s main agricultural regions and may facilitate prediction of the future trends.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Literature selection and data extraction

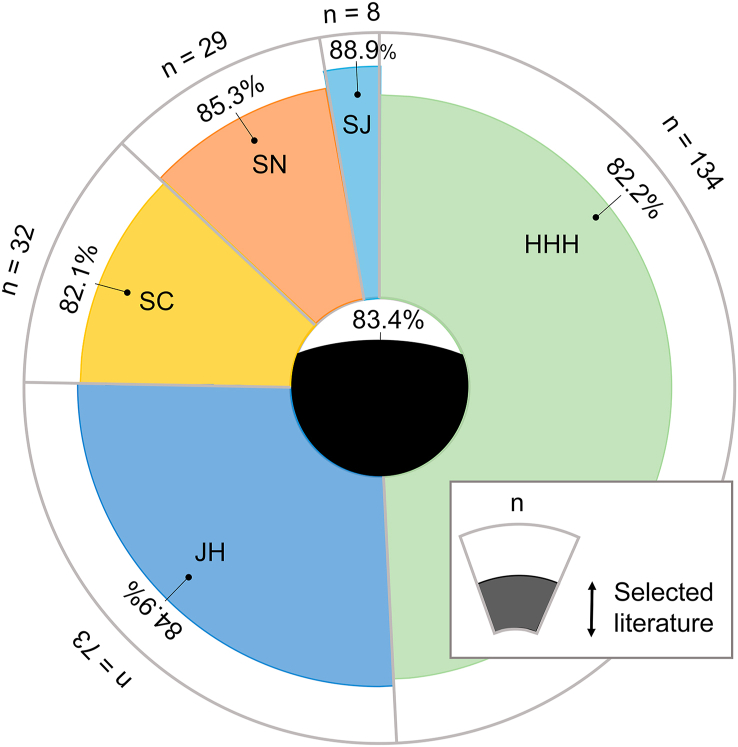

To obtain mean values and standard deviation data of the total amount of heavy metals in the five major producing regions, we conducted a comprehensive literature search in September 2021 on the Web of Science and China National Knowledge Infrastructure using key words “heavy metal∗” (or using individual heavy metal) AND (“soil” OR “farmland” OR “arable land”) AND “China” (or names of the five major regions) with a publication date of “2010–2021”. As a result, 439 articles were found and then screened for those reported in the five major regions. From the resulting 331 articles, we adopted those that reported data with both mean values and standard deviations of heavy metals in the top 0–20 cm soil. Consequently, a total of 276 articles were used as the raw data source in the meta-analysis. According to the 331 articles, the HHH region had the most cases (134), while the SJ region had only 8 cases (Fig. 2). We extracted 1778 pairs of means and standard deviation for the experimental group. The background values of each area were extracted from the China Environmental Background Values of Soil for the control group [16].

Fig. 2.

Available studies in the open literature on heavy metals pollution in the five major grain-producing regions of China. n, numbers of selected literature.

From the 276 studies, we extracted the key factors related to the soil pollution, including soil pH and farmland use pattern. In addition, we acquired data of mean annual precipitation (MAP) and mean annual temperature (MAT) from the China Statistical Yearbook (2010–2020) [15] to conduct the subgroup analyses.

2.2. Meta-analysis

To obtain the general distribution and evolution trend of heavy metals in the farmland, we compared the data extracted from the literature with different background values by meta-analysis. Generally, the response ratios were used to calculate the effect size when two groups of data are non-negative [26]. Firstly, the log response ratios were calculated via Eq. 1 along with its variances (Eq. 2). Secondly, the random-effect model was used to calculate the effect size and confidence interval (CI) of each study (Eqs. (3), (4)). The weight of individual study was not identical due to varied study areas and sample size. Although both fixed- and random-effect models can be used to calculate the weight [27], the random-effect model was chosen based on the Q statistic test (Eq. 5) of the literature heterogeneity [28], where a P-value of <0.001 reveals a heterogeneous case [25]. Thirdly, the resulting effect size (Eq. 1) and confidence interval (Eq. 5) from each single study were used to compute the sum. Finally, we classified data with diverse factors in different groups to conduct subgroup analysis. The R studio with a metaphor package was used to analyze the data.

| (1) |

where lnR is the effect size of each study, R is the response ratio, XE is the mean value of experimental groups, and XC is the mean value of the control groups.

| (2) |

where VlnR is the variance of the effect size, SE is standard deviation of the experimental groups, SC is the standard deviation of control groups, nE is the number of samples for experimental groups, nC is the number of samples for control groups, and XE and XC have the same meaning as in Eq. 1.

| (3) |

where wi is the reciprocal of variance of a single study, σb is the between-study variance, and σi is the within-study variance.

| (4) |

where CI95% is the confidence interval of each study, , μ is the true mean effect size over all studies, Li is the effect size estimated in a single study.

| (5) |

where Q is the statistic of Q-test, wi and Li are the same as in Eq. 4.

2.3. Publication bias test and adjustment

Publication biases may exist due to the large and diverse pool of the source data, [29,30]. To evaluate the degree of the publication bias, the Egger’s test was conducted on the source data [31]. A PE-value of <0.05 from the Egger’s test indicates a significant publication bias. Tables S1 and S2 show the resulting PE values, where 30 data from the five major regions showed significant publication bias.

Furthermore, we used the trim-and-fill method to adjust the publication bias for the subsequent meta-analysis [32]. It aims to add or delete studies in the database until it becomes symmetric [33]. Tables S3 and S4 present the adjusted results through the trim-and-fill method. It is noteworthy that some dataset results may still bear with significant publication biases (PE < 0.05) even with the trim-and-fill method adjustments. However, the biases after the adjustment do not affect the effect sizes, indicating that results are robust.

2.4. Assessment of soil pollution levels

We chose the monomial pollution index (Pi) to assess the pollution levels:

| (6) |

where Ci is the concentration of metals (mg/kg), Si is the background concentration (mg/kg). The resulting pollution levels based on the Pi values are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Pollution level classification according to Pi.

| Pi | Pollution level |

|---|---|

| Pi ≤ 1.0 | clean |

| 1.0 < Pi ≤ 2.0 | trace |

| 2.0 < Pi ≤ 3.0 | light |

| 3.0 < Pi ≤ 5.0 | moderate |

| Pi > 5.0 | severe |

2.5. Weight calculation

We aimed to examine the current status of heavy metal pollution against the latest Chinese regulatory standards (Table S5) by considering the characteristics of the studied regions. Proper weighting factors were determined per Eq. 7 for each area to obtain sound mean values of the heavy metals from the data we extracted. Generally, a case with larger study regions (Ai), more samples (Ni) and smaller variances (SDi) is more reliable to infer the general level, and thus, was assigned a greater weight [11].

| (7) |

where wi' is the weight of individual study.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Spatiotemporal evolution of heavy metal pollution in five major grain-producing regions: 2010–2021 vs. 1990 background data

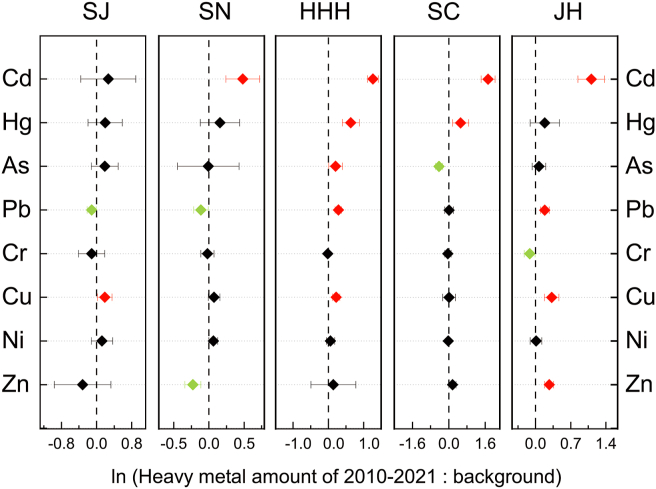

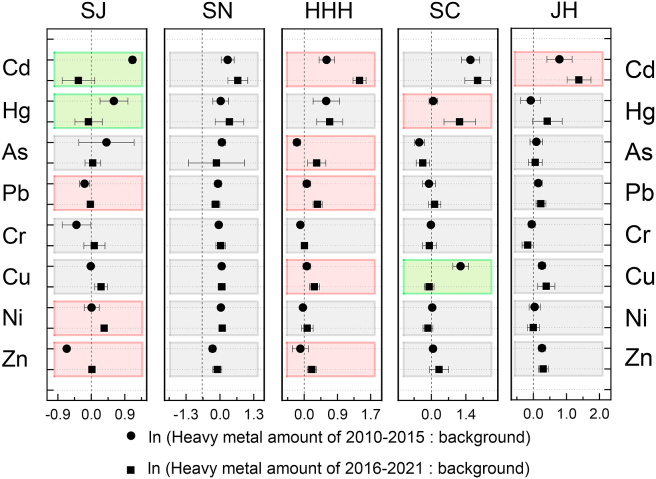

Changes can be observed for the 8 primary pollutants in the five major grain-producing regions from 2010 to 2021 when compared to the benchmark values of 1990 (Fig. 3). While the variations differed among the different areas, Cd, Hg, Pb and Cu showed the most aggressive increase (with more than 2 red markers in Fig. 3), with Cd being the worst in terms of both number of impacted regions and effect size (with 4 red markers and large effect size). Based on the number of regions where the pollutants showed an increasing trend, the impact severeness of the pollutants is ranked in the order of: Cd (4 regions) > Cu (3) > Hg (2) = Pb (2) > Zn (1) = As (1) > Ni (0) = Cr (0). The highest increase of Cd (up to 1.73 [1.42–2.04] in SC when compared to the 1990 background levels) was found in SN, HHH, SC and JH regions, indicating that Cd was the most severe heavy metal pollutant in those regions (Fig. 3). Interestingly, regions in the north (SJ, SN and HHH) faced lighter Cd pollution than in the south (SC and JH). Notable accumulation of Cu was found in three major regions (SJ, HHH, and JH) with a much smaller ratio than for Cd. The increase of Hg in HHH and SC was more significant than other metals. All the effect sizes of Hg exceeded the ratio of 0, though its increase was not significant in SJ, SN, and JH. These results indicate that Hg in most cases showed an increasing trend when compared to the background levels, though these data showed great variances among studies. The accumulation of Pb was significant in HHH and JH, while a decrease of Pb was found in SJ and SN. The levels of both Zn and As increased in one of the five regions, while Zn decreased in SN and As decreased in SC. In contrast, Ni displayed no significant changes in all the five major grain-producing regions. Cr decreased in JH without significant differences when compared with the background levels in other four regions. HHH was most polluted with five heavy metals (Cd, Hg, As, Pb, and Cu) showing a growing trend, followed by JH (4), SC (3), SN (1), and SJ (1). It is noteworthy that some reduction of heavy metal concentration was found in SN (Pb and Zn), SJ (Pb), SC (As) and JH (Cr).

Fig. 3.

Effect sizes of 8 metals during 2010–2021 normalized to the background (1990) levels. X-axis means the response ratio of heavy metal amount of past 12 years: background in a natural log scale. Values are effect sizes with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A ratio of 0 (or CIs overlapped with 0) means statistically no significant difference between the 12-year data and the background levels. A ratio larger than 0 (marked in red) indicates an increase of a pollutant compare with the background levels, and whereas a ratio smaller than 0 (green) indicates a decrease.

The results indicate that Cd pollution is the most severe issue for the farmland, which is consistent with other reports [1,[34], [35], [36]]. The MEP (currently MEE) reported that Cd showed the highest over-standard rate (7.0%) followed by Ni (4.8%), As (2.7%), and Cr (1.1%) in Chinese soil [5]. The MEE also set the lowest limitation for Cd (0.3 mg/kg in paddy land with a pH ≤ 5.5) as a national soil risk control standard (0.5 mg/kg for Hg under the same conditions) (Table. S5). Huang et al. [11] reviewed the literature published from 2005 to 2017 and indicated that Cd had the highest exceedance ratio (29.4%) when compared to other heavy metals (all of them were under 0.1%) in Chinese farmland. Our results of the Cd pollution status in the five major farmland regions agree with these reports. In addition, there were no significant differences between the amount of Cd in SJ region and background values (Fig. 3). Since the sample sizes for the SJ region were the smallest and the data in SJ showed larger variance among studies, all the results for SJ were uncertain.

Our results show that Cu accumulation in most major farmlands was much worse than that in previous work. Some studies claimed that the contamination of farmland by Cu was minor in the southern China, while no Cu contamination was detected in the north [11,12,24]. It was found that one pitfall of these prior studies was the evaluation of the pollution status of Cu based on national average background (22.6 mg/kg), which can deviate largely geographically. To overcome the drawback, this work used the background values that are specific for each major region (Table S6). The average regional background values of Cu were 20 mg/kg in SJ, 19.76 mg/kg in SN and 21.48 mg/kg in HHH, all of which were below the national average. Those regions are all located in the northern China. Namely, the new data showed that severe Cu pollution in both northern and southern farmlands.

As one of the most widely investigated heavy metals, Hg is extremely poisonous to humans and its pollution in farmland has been under close scrutiny [37,38]. Yuan et al. [12] indicated that Cd and Hg were the major pollutants in Chinese farmlands, because both had higher geo-accumulation indices than control groups (Cd as 76.99%, Hg as 59.31%, Zn as 31.49%, Cu as 30.65% and Pb as 29.72%). Ren et al. [24] surveyed data from 1998 to 2019 and showed that only Cd and Hg had a positive geo-accumulation index (numbers of As, Pb, Cr, Cu, and Zn were negative). The results of this work also found Hg pollution was significantly severe in HHH and SC (Fig. 3). In other major producing areas (SJ, SN, and JH), the Hg concentration also exceeded the background values, though the data had larger variance between studies.

Researchers have also paid substantial attention to Pb and Zn pollution issues [39,40]. Huang et al. [11] reported that in addition to high Cd-levels (exceedance percentage = 29.4%), significant exceedance percentages were found for Hg (0.07%), Zn (0.07%) and Pb (0.06%). Ren et al. [24] retrieved 112 county-level study cases and concluded that Pb, Cu and Zn had increased more seriously in Chinese farmlands. Our study also found Pb and Zn showed more severe pollution status when compared with other metals (Cr, Ni and As) in these five major producing regions.

Our results indicate that Cr pollution of the farmlands was less severe than other metals in the five regions. This observation agrees with the previous study that the exceedance percentage of Cr was the lowest among 8 heavy metals (0.007% for Cr and higher than 0.01% for all other heavy metals) [11]. Li et al. [22] summarized literature data from 1989 to 2016 and reported that Cr concentration decreased more significantly in farmlands in southern China than in northern China. Likewise, we also found the concentration of Cr decreased in JH region (located in southern China). However, it is noteworthy that the background value of Cr (70.59 mg/kg) in JH was much higher than the national average (61 mg/kg) (Table. S6). In addition, our results show that Ni and As were similar to Cr in the effect size and geographic distribution. Yuan et al. [12] indicated that Cr, Ni and As had smaller Pi values than other heavy metals (1.04 for Ni, 1.01 for Cr and 0.97 for As, while more than 1.2 for other metals). We also found that the concentration of As showed no significant difference from the background values in SJ, SN, and JH, and even decreased in SC. Although the amount of As increased in HHH, the effect size and CI were close to 0 (Fig. 3), suggesting a smaller increase than in other cases. In general, the pollution of Cr, Ni and As appeared largely alleviated in the five major grain-producing regions during the past 12 years.

3.2. Spatiotemporal evolution of heavy metals pollution in five major grain-producing areas: 2010–2015 vs. 2016–2021

To examine the spatiotemporal evolution trends of the eight heavy metals, we split the data into two groups, i.e., data from 2010 to 2015 and 2016 to 2021. The Z-test was carried out to assess the variation between the data from these two groups, where a P-value > 0.05 indicates no significant difference between the two periods (Fig. 4). The spatiotemporal evolution of the heavy metals pollution was then assessed based on three aspects: 1) the meta-analysis of the data; 2) the mean values and SDs of the metal concentrations; and 3) the exceedance percentages of the metals against the 1990 background values or risk control standards.

Fig. 4.

Changes of heavy metals pollution from the period of 2010–2015 to 2016–2021. Values are effect sizes with 95% CIs. Blocks marked in grey indicate no significant changes in the mean metal levels between two periods, those marked in red indicate an increase from the (2010–2015) to (2016–2021), and those marked in green suggests the pollution levels were alleviated.

Changes in amounts of the eight metals in the five regions over the two periods are shown in Fig. 4. It is evident that 67.5% of the data showed no significant difference (grey), 25% showed an increasing trend (red), and only 7.5% showed a mild decrease (green). The most consistent increase was observed for HHH, where five of the eight pollutants increased (red blocks in Fig. 4). In addition, elevated Cd, Pb, and Zn were found in two regions, Hg, As, Cu, and Ni in one region, and Cr showed no significant differences in any region. Meanwhile, the mean values of all the heavy metals exceeded the 1990 background values during the two periods (Fig. S2). Figs. S3 and S4 give the exceedance percentages of the heavy metals in the five areas compared with background values/risk control standards. Compared with the background values (Fig. S3), all heavy metals increased during at least one of the periods. Compared with the risk control standards (Fig. S4), the exceedance percentages were all under 20% except for Cd in HHH, SC, and JH and Zn during 2016–2021 in SJ.

Cd: The results revealed that Cd was the most challenging pollutant, and the trend of Cd pollution intensified during 2016–2021 in HHH and JH. This conclusion is based on three aspects. First, according to meta-analysis (Fig. 4), effect sizes of Cd in 2016–2021 were higher than those in 2010–2015 in the two regions. For SN and SC, although there was no statistically significant difference in the effect sizes between the two time periods, the effect sizes of 2016–2021 were all larger than those of the 2010–2015 data. Second, the mean values and SDs of the Cd levels in 2016–2021 were significantly higher than those in 2010–2015 (Fig. S2). Third, the exceedance percentages of the Cd levels against the background values or risk control standards showed an increasing trend during 2016–2021 (Figs. S3 and S4). Earlier, Huang et al. (2019) observed that the Cd levels in agricultural soil in China showed an upward trend during 2004–2016. Our work suggests that this trend continued during 2016–2021.

Although the Cd level in SJ showed a decreasing trend, the mean values of Cd exceeded the 1990 background values in all five regions. Moreover, except for SJ, the mean values of Cd all exceeded the risk control standards in 2016–2021. Compared with background values (Fig. S3), the increase in the Cd levels in four out of the five regions (except for SJ) was higher than those of other metals. Accordingly, in reference to the risk control standards (Fig. S4), the exceedance percentages of Cd (up to 79%) were the largest of all the metals (<30% for all heavy metals, except 100% for Zn during 2016–2021 in SJ), and exhibited the highest increasing trend during the two periods in four areas (SN, HHH, SC, and JH region).

Pb: Based on the meta-analysis (Fig. 4), the Pb levels increased during 2016–2021 in SJ and HHH, and the small gaps between two effect sizes suggested that the increases were rather modest. Similar trends were found with the mean values and sample exceedance percentages (Figs. S2–S4). After extracting information from more than 1900 published articles, a study conducted by Shi et al. [41] found the concentration of Pb in agricultural soil across China increased rapidly from 1979 to 2000, followed by a subsequent slow upward trend from 2001 to 2016. Our results showed that this slow upward trend continued during 2016–2021 in SJ and HHH.

Zn: The spatiotemporal evolution of Zn displayed a worsening trend from 2010 to 2015 to 2016–2021 in two (SJ and HHH) out of the five regions (Fig. 4), although the 12-year average showed no severe change when compared to the 1990 baseline data (1 red dot in Fig. 3). Meanwhile, the mean values of Zn (Fig. S2) showed increasing trends during 2016–2021 in all the five regions compared to the background values (Fig. S3), and the Zn levels all exceeded the risk control standards (Fig. S4). Huang et al. [11] found the concentration of Zn in farmlands in China increased during 2004–2012 and then decreased during the 2012–2016 period, while Yuan et al. [12] indicated Zn in farmlands declined gradually between 1999 and 2019 in China. However, the data from our study suggested an increasing trend of Zn pollution during 2016–2021 in the major farmlands in China.

Hg: The accumulation of Hg in SC during 2016–2021 was more profound than that during 2010–2015. Meanwhile, a decreasing trend was found in SJ (Fig. 4). Although significant Hg accumulation was observed in SC, the mean values of Hg were all under the risk control standards (Fig. S2), with only one sample exceeding the threshold during 2010–2015 in HHH and another during 2016–2021 in JH. Wang et al. [42] surveyed 444 articles published during 2005–2015 and concluded that Hg concentration in farmland soil was higher in southern China than that in the north. Our results suggested that this distribution remained true in the most recent 6-year period.

Cu: The spatiotemporal evolution of Cu showed a worsening trend in HHH, but alleviated in SC (Fig. 4). The mean value and SD of Cu (Fig. S2) were higher than the risk control standards during 2016–2021 in JH. Compared with the background values (Fig. S3), the exceedance percentages of Cu increased in HHH and SC, though a slight decrease in JH. Considering the results from both meta-analysis and exceedance percentages, the Cu accumulation in HHH was remarkable. Based on 482 published papers from 2004 to 2017, Liu et al. [43] found a larger spatial cluster of Cu in Hunan and Fujian provinces, while a smaller cluster in Chongqing. Our results showed that the accumulation of Cu had no significant difference in JH, which includes part of Hunan and Fujian, and decreased in SC, including Chongqing, suggesting that this spatial distribution continued to grow in the recent six years in SC.

As, Cr, and Ni: Overall, the pollution status of Cr, Ni, and As appeared not as severe as the other heavy metals (Cd, Hg, Pb, Cu, Zn) during 2016–2021 in the five regions (Fig. 4). However, As exhibited a severe increase in HHH (with a big gap between effect sizes of two time periods). A significant increase in Ni was only found in SJ region, whereas no significant difference was found for Cr between those two periods. Fig. S2 shows that the mean values and SDs of Cr and Ni were all under the risk control standards. Compared with the 1990 background values (Fig. S3), the levels of Ni showed a diminishing trend during 2016–2021 in three regions, and the levels of Cr and As decreased significantly in JH and SJ, respectively. With regard to the risk control standards (Fig. S4), both Cr and Ni appeared to be within limits in all five areas. However, some samples showed that during 2016–2021, exceedance percentages of As accumulated from 0% to 22% in HHH. Gong et al. [44] investigated 1684 sites collected from 1985 to 2016 and concluded that the growth rate of As pollution in Chinese farmlands slowed down during 2012–2016. Our study suggested that this trend continued during 2016–2021 in these major agricultural areas except for HHH.

With data from 3672 soil samples (extracted before 2016) in China, Zhang et al. [14] reported that Cd, Ni, Cu, Zn, and Hg were the primary heavy metals found in the five major grain-producing areas, accounting for 17.39%, 8.41%, 4.04%, 2.84%, and 2.56%, respectively of total heavy metals pollutants. While in our study with the data after 2016, combining the results of meta-analysis, weighted mean values and SDs, and exceedance percentages, the pollution levels of Cd, Hg, Cu, Pb, and Zn appeared exacerbated during 2016–2021 in the five regions.

Based on the number of red blocks in Fig. 4 and other results, the severity of metal pollution follows the order of HHH > SJ > JH > SC > SN. In HHH, five heavy metals kept increasing, and the difference between the effect sizes of the two periods was the largest. The results indicated that the concentrations of three pollutants increased in SJ, but the sample size (n = 8) was much smaller than those from other regions. In general, HHH, SC, and JH all showed a severely increasing trend during 2016–2021. The results agree with those by Ren et al. [24], who reported that the main trend of the standard deviational ellipse changed significantly in the “east-to-west” direction during 2013–2019.

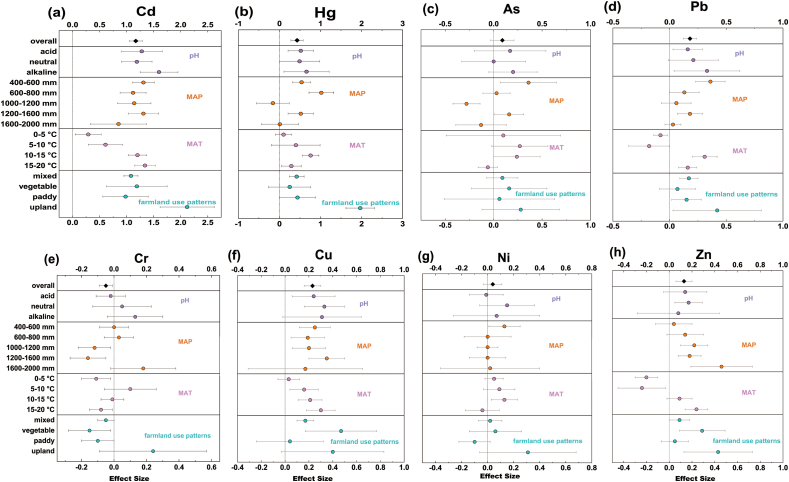

3.3. Relationships between heavy metals pollution and some key factors

Preliminary correlations exist between the accumulation of heavy metals and some key factors [45,46]. To examine the relationships, the data from the five regions were combined and reorganized based on the soil pH, MAP, MAT, and farmland use pattern. As shown in Fig. 5, compared with the 1990 background values, concentrations of Cd, Hg, Cu, Pb, and Zn all increased, with Cd having the sharpest increase with a value of 1.17 (1.05–1.29), followed by Hg (0.43 [0.28–0.58]), Cu (0.23 [0.16–0.30]), Pb (0.18 [0.12–0.24]), and Zn (0.13 [0.06–0.20]). Concentrations of As and Ni exhibited no significant difference from the background values, whereas Cr demonstrated a significant decline with an effect size value of −0.05 (−0.01 to −0.09).

Fig. 5.

Relationship between effect size of 8 heavy metals and the soil pH, mean annual precipitation (MAP), mean annual temperature (MAT), and farmland use patterns based on data during 2010–2021 and the background values in 1990. Values of effect sizes are calculated at the 95% CIs. A ratio of 0 (or CI = 0) means statistically no significant difference between the 12-year data and the background levels. A ratio greater than 0 indicates an increase of a pollutant compared with the background levels, whereas a ratio less than 0 indicates a decrease.

3.3.1. Relationships between heavy metals pollution and soil pH, MAP, and MAT

According to GB 15168-2018 [7] (Table. S5), soil pH data extracted from 276 publications were classified into three groups: acidic (5.5 < pH ≤ 6.5), neutral (6.5 < pH ≤ 7.5), and alkaline (7.5 < pH ≤ 8.5). As shown in Fig. 5, the soil pH critically impacted the accumulation of heavy metals in all five regions (most values > 0). For Cd, Hg, and Pb, more significant increases were observed under more alkaline conditions, with effect size values being 1.6 (1.25–1.95), 0.66 (0.11–1.21), and 0.33 (0.04–0.62), respectively, in reference to the 1990 background levels. Significant positive values were also found for Cu (0.33 [0.16–0.50]) and Zn (0.17 [0.05–0.29]) under neutral soil pH conditions. However, no significant difference was observed for Cr, As, and Ni, suggesting these metals/metalloids were not closely related to soil pH. Because the soil in HHH was mainly alkaline, while the soil in other areas was acidic or neutral, the data of HHH contributed more to these results. To demonstrate the change in pollution levels with various ranges of soil pH in different regions (Fig. S5a), we used the mean values and calculated the pollution levels with Eq. 6 in the different pH ranges. The moderate to severe (red to dark red) pollution levels were mainly found for Cd and Hg in HHH and SC (Fig. S5a). In particular, severe Cd pollution was found in HHH under neutral or alkaline conditions. In the SC region (with no data within 7.5 < pH ≤ 8.5), Cd and Hg pollution levels turned more severe with acidic soil than neutral.

To test the relationships between heavy metals pollution and precipitation, we classified MAP into five ranges: 400–600, 600–800, 1000–1200, 1200–1600, and 1600–2000 mm (Fig. 5). For Cd and Cu, significant accumulations were found in all MAP ranges except for 1600–2000 mm for Cu. Both metals were substantially increased with 1200–1600 and 400–600 mm. Hg, As, Pb, and Ni tended to accumulate more with 400–800 mm, whereas Cr decreased in 1000–1600 mm, and no significant change was found in other ranges. Zn accumulated in 1000–2000 mm, especially in 1600–2000 mm (0.46 [0.19–0.73]). The pollution levels of Cd were moderate with a MAP of 400–800 mm in HHH (marked in red), and turned moderate to severe (dark red) with a range of 1000–2000 mm in SC and JH (Fig. S5b).

MAT was mainly 0–10 °C in SJ and SN, 10–15 °C in HHH, and 15–20 °C in SC and JH. Cd, Hg, Pb, Cu, Ni, and Zn showed higher accumulations in the MAT range of 10–15 °C or 15–20 °C. No significant difference with the background levels was found under various MAT ranges for As, suggesting MAT might not significantly affect the As pollution status. In contrast, Cr showed a significant decrease in 0–5 °C (−0.11 [−0.02 to −0.2]). As shown in Fig. S5c, the Cd pollution levels turned from moderate to severe in HHH, SC, and JH in 10–20 °C.

Previous studies have demonstrated that soil pH greatly influenced the concentration and phyto-availability of heavy metals in farmland soil [47,48]. With increasing soil pH, the mobility and solubility of cationic heavy metals (Cd2+, Hg2+, Cu2+, Pb2+, and Zn2+) decreased [48,49] due to more favorable adsorption and high surface precipitation. In HHH, the soil pH ranged between 6.5 and 8.5, and MAP between 400 and 800 mm. Generally, these immobilized heavy metals tend to remain stable under basic soil conditions (6.5 < soil pH ≤ 8.5) and low levels of MAP (400–800 mm). Therefore,Cd, Hg, Pb, Cu, Zn severely accumulated under neutral or alkaline soil conditions (data of HHH took the greatest weight in the overall results) (Fig. 5), and the pollution levels of Cd (Fig. S5a–b) were more severe with basic soil pH and low MAP in HHH. In addition, acid deposition was more common in SC and JH than in the other regions [50]. Under acidic soil conditions, heavy metals tend to be dissolved as mobile ions, and a higher MAP would result in a lower accumulation of the metals. However, in our results, a higher MAP did not appear to lead to decreased heavy metal concentrations in soil. This may be because more heavy industries are present in these southern regions (SC and JH) than in HHH [11], and a larger MAP could transport more heavy metals from the industrial sites to the farmland and/or promote atmospheric deposition of metals-laden industrial waste gases. This is supported by the fact that researchers have observed that atmospheric deposition could contribute up to 86% to the total soil Cd in farmland in SC [14].

3.3.2. Relationships between heavy metals and farmland use patterns

To investigate the relationships between farmland use patterns and heavy metals accumulation in the five major areas, we divided the data into four groups based on the type of species: mixed (≥ two patterns), vegetable, paddy, and upland. The accumulation of heavy metals (except As) varied greatly under different farmland use patterns. As shown in Fig. 5, Cd (2.12 [1.62–2.62]), Hg (1.97 [1.62–2.32]), Pb (0.42 [0.03–0.81]), and Zn (0.43 [0.13–0.73]) accumulated most severely in upland cropping soils, Cd (0.98 [0.56–1.40]) and Pb (0.15 [0.02–0.28]) showed a significant increase in the paddy soils, and Cu (0.47 [0.17–0.77]) and Zn (0.29 [0.09–0.49]) in the vegetable-growing soils. Only Cr showed a decreasing trend (−0.15 [−0.02 to −0.28]) in the vegetable-growing soil. Some heavy metals (Cd, Hg, Pb, and Zn) increased in mixed-cropping soils, but the values were lower than those in the upland cropping soils. This observation suggested that, compared with single farmland use pattern, mixed patterns might help alleviate levels of heavy metals in soil.

Previous studies demonstrated that heavy metals in farmlands accumulated differently in farmland use patterns. Based on 81 samples, Xu et al. [51] found that accumulation of Cd followed the order of vegetable (rape field) > paddy (paddy field) > upland (wheat field). While Cu pollution was more severe in vegetable fields than in paddies. Huang et al. [52] observed that higher contents of Cu and Zn in vegetable fields than in upland fields, due to the long-term use of excessive chemical fertilizers and organic manures in vegetable fields. Bai et al. [53] reported that the accumulation of total heavy metals was in the order of greenhouse field > vegetable field > upland field > forest field, and addressed the main reason for the varied application of fertilizer and pesticides in different patterns. In this study, we found that in five major farmland areas, the accumulation of Cd and Zn was more significant in upland fields than in vegetable fields, while a higher amount of Pb was found in the upland field than in the paddy field. Meanwhile, the accumulation of Cd, Hg, Pb, and Zn showed alleviated in mixed land use patterns than in upland fields, suggesting that mixed patterns might help alleviate heavy metal levels in soil. Moreover, Yang et al. [54] found that after one-year of cultivation in varied farmland patterns, the levels of Cd and Pb in the soil were reduced by at least 31.5 g/ha and 268.7 g/ha.

Moderate to severe pollution levels were mainly found for Cd in HHH, SC, and JH (Fig. S5d). In HHH, the pollution levels of Cd appeared more severe in soil with mixed-cropping patterns or upland farmland use pattern. In JH, the Cd concentration was higher in the vegetable-growing and paddy soils. While in JH, the pollution levels of Cd were rated moderate or severe with all kinds of species.

3.4. Control and prevention policies and measures of soil pollution by heavy metals in China

An overview of actions taken by policymakers in China to reduce the risks posed by soil pollution from 1958 to 2022 is given in Fig. S6, including national soil surveys, national standards & laws, and research & development related to heavy metals.

National soil surveys: China first started to monitor concentrations of heavy metals in soil in the middle of the last century. The first National Soil Survey was conducted from 1958 to 1960, which initiated the buildup of a soil science database and the first agricultural soil classification system in China [55]. After nearly 20 years of interruption, the second National Soil Survey was carried out during 1979–1985, which collected information on soil nutrients and various soil improvement measures [[56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62]]. Based on the data from these two national surveys, the China Environmental Background Values of Soil were established in 1990 [16], which included the background values of heavy metals at the provincial scale. During 2005–2014, a Survey of National Soil Pollution Status was performed [5], and the resulting report was published in 2014, listing the exceedance ratios of eight heavy metals (Cd at 7.0%, Hg at 1.6%, As at 2.7%, Cu at 2.1%, Pb at 1.5%, Cr at 1.1%, Zn at 0.9%, and Ni at 4.8%). It also pointed out that farmland pollution was more severe in the south than in the north. In addition, Cd, Hg, As, and Pb concentrations in soils increased gradually from the northwest to the southeast, and from northeast to southwest of the country. In 2022, the third National Soil Survey was launched [63], aiming to thoroughly examine soil quality, soil types and their distribution, present and possible future conditions of soil resources.

National Standards and Laws: To regulate the pollutants discharged into farmland systems, China enacted a series of national standards. The first national standard for irrigation water quality control was enacted in 1985 (GB 5084-85), and then amended in 1992, 2005, and 2021, to limit seven heavy metals (Hg, Cd, As, Cr, Pb, Cu, and Zn) [64]. In addition, in 2007, GB 20922-2007 was established, which specifies the urban recycling irrigation normative references, terms and definitions, quality requirements, other requirements, and monitoring and analytical methods. It sets standards for Hg, Cd, As, Cr, and Pb in irrigation water when applied to four classes of crops (fiber crops, dry grain, wet grain, and open-air vegetables) [65]. Then in 1995, soil quality regulations (GB 15168-1995) were established [6], which specify the maximum concentrations for eight heavy metals according to the soil pH. The standards were further amended in 2018 (GB 15168-2018) [7], establishing risk screening values and risk intervention values for heavy metals in upland and paddy farmlands. In addition, two standards (GB/T 36783-2018 and GB/T 36869-2018) were established regulating the allowable levels of heavy metals in soils for root stalk vegetables and rice fields with varying organic matters [66,67].

In recent years, the Chinese government has taken additional steps to mitigate or prevent soil pollution by heavy metals [68]. The 2015 amended Environmental Protection Law prohibits the application of heavy metals to soils during agricultural production [69]. In 2016, the Soil Contamination Prevention and Control Action Plan, also known as the “Soil Ten Plans”, was released [70]. Moreover, the Soil Pollution Prevention and Control Law of the People’s Republic of China was promulgated in 2019, creating a specific regulatory framework for soil pollution control [71].

Research, Development, and Deployment: The Chinese government has also enacted an ambitious research, development, and deployment (RD&D) agenda to promote the development of innovative technologies for pollution mitigation and prevention. During the 12th Five-Year Plan (2011–2015), the government laid out a prevention and control system for heavy metals [72]. The 13th Five-Year Plan (2016–2020) established a goal to cut heavy metal emissions from major industries by 10% by 2020 compared with the 2013 level [73]. Recently, the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021–2025) required that heavy metal emissions be further decreased by 5%, compared with 2020, by 2025 [74].

Driven by these Five-Year Plans and the RD&D, various measures have been taken to protect agricultural soil quality. For example, a “VIP + N” technology system (V, low cadmium rice variety; I, irrigation in whole growth period; P, soil pH; N, auxiliary measures) for Cd reduction was first initiated in Hunan province in 2014. Since then, the average Cd content in rice was reduced by >60% with improved quality and production [75].

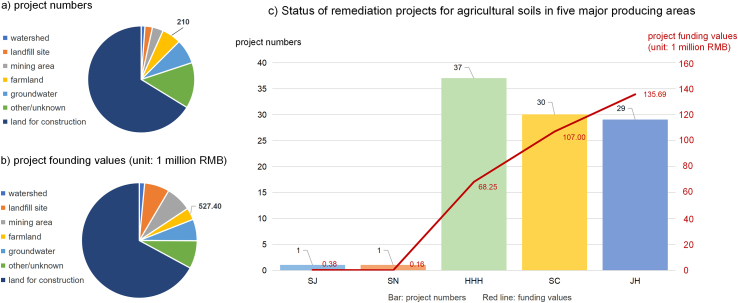

The market of farmland remediation: In 2021, approximately 3600 site remediation projects were implemented in China at an expenditure of 15.7 billion RMB. These remediation projects included watersheds, landfills, mines, farmland, groundwater, land for construction, and others. As shown in Fig. 6a and b, only 5.8% of projects (210 projects, details can be found in Table S13) and 3.4% of project funding (527 million RMB) were devoted to farmland remediation. For the five major grain-producing areas (Fig. 6c), there were fewer projects in SJ and SN than in the other three regions, and these projects were generally of smaller size. HHH had the largest number of remediation projects, but the total funding was lower than for JH and SC. This contradicts our findings in this study that HHH showed the most severe heavy metals pollution, which demands more remediation investment. The total cost of remediating all contaminated land in China to fit crops or livestock was estimated at about 5 trillion RMB [76]. As such, a huge amount of investment and more cost-effective technologies are urgently needed.

Fig. 6.

Proportion of farmland remediation projects in total remediation projects in five major grain-producing areas in 2021 in terms of (a) project numbers and (b) project funding values. (c) Status of remediation projects for agricultural soils.

4. Conclusions and perspectives

In this study, we extracted and analyzed data from 276 publications during 2010–2021 and used meta-analysis to obtain an overall spatiotemporal evolution profile of eight priority heavy metals in five major grain-producing regions in China. The key findings are summarized as follows:

1) Compared with the region-specific background values, five heavy metals (Cd, Hg, Cu, Pb, and Zn) represented the most severe pollutants in the five regions, and the pollutant concentrations followed the order of Cd > Cu > Pb > Zn > Hg. Cd showed the largest effect size values, highest exceedance percentages to the regulatory limits, and most severe pollution levels. Cu increased in both northern and southern farmlands compared with the 1990 background values. Of the five areas, the HHH region exhibited the most severe pollution status, with five kinds of heavy metals (Cd, Hg, As, Pb, and Cu) severely accumulated.

2) Levels of Cd, Hg, Cu, Pb, and Zn showed certain increasing trends during 2016–2021 in some areas compared to 2010–2015 and the 1990 background levels. Cd was the number one pollutant with the largest difference between the two effect sizes of the two periods and exceedance percentages compared with the risk control standards. The highest accumulations of Cd, As, Pb, Cu, and Zn were all found in HHH.

3) Subgroup meta-analyses revealed that the pollution levels of Cd were more severe with alkaline soil and lower MAP in HHH, while more severe with acidic soil and higher MAP in SC and JH. Compared with single species in the upland crop pattern, smaller effect sizes of some heavy metals were found in soils used for mixed-cropping systems, indicating that mixed farmland use patterns could help alleviate the accumulation of heavy metals in soil.

4) With new environmental regulations enacted and more remediation and prevention actions taking place, the upward accumulation trends of some metals (e.g., As and Cr) appeared to have slowed down. However, farmland remediation projects make up only a small share of the overall remediation market in terms of the number of projects and overall expenditures. In addition, more investment should be geared towards regions such as HHH that show high levels of pollutants and a fast accumulation trend.

The findings from this work provide an improved understanding of the status and trend of heavy metals in major Chinese farming regions. The information is essential for guiding sound risk assessment, regulatory development, pollution prevention measures, funding allocation, and the best remediation practices.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Xiao Zhao is grateful for the support by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51809267), the Chinese Universities Scientific Fund (No. 00109018), and the 2115 Talent Development Program of China Agricultural University (No. 00109018).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eehl.2022.10.004.

Contributor Information

Xiao Zhao, Email: xiaozhao88@cau.edu.cn.

Dongye Zhao, Email: zhaodon@auburn.edu.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Zhang L., Zhu G., Ge X., Xu G., Guan Y. Novel insights into heavy metal pollution of farmland based on reactive heavy metals (RHMs): pollution characteristics, predictive models, and quantitative source apportionment. J. Hazard Mater. 2018;360:32–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.07.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu H., Jia Y., Sun Z., Su J., Liu Q.S., Zhou Q., Jiang G. Environmental pollution, a hidden culprit for health issues. Eco-Environ. Health. 2022;1:31–45. doi: 10.1016/j.eehl.2022.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang H., Wang W., Lin C., Feng X., Shi J., Jiang G., Larssen T. Decreasing mercury levels in consumer fish over the three decades of increasing mercury emissions in China. Eco-Environ. Health. 2022;1:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.eehl.2022.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao F., Ma Y., Zhu Y., Tang Z., McGrath S.P. Soil contamination in China: current status and mitigation strategies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015;49:750–759. doi: 10.1021/es5047099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ministry of Environment Protection of the People’s Republic of China (MEP), Ministry of Land and Resources of China (MLR), Report of National Soil Pollution Investigation. MEP and MLR; Beijing: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ministry of Environment Protection of the People’s Republic of China. The State Bureau of Quality and Technical Supervision, Environmental quality standard for soils, Standards Press of China; Beijing: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ministry of Environment Protection of the People’s Republic of China, State Administration for Market Regulation . China Environmental Press; Beijing: 2018. Soil Environmental Quality Risk Control Standard for Soil Contamination of Agricultural Land. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang L., Yang M., Wang L., Peng F., Li Y., Bai H. Heavy metal contamination and ecological risk of farmland soils adjoining steel plants in Tangshan, Hebei, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018;25:1231–1242. doi: 10.1007/s11356-017-0551-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liang Y., Zhang J., Xiao X., Xing M., Lu Y., Wang L. Risk assessment of heavy metals in overlapped areas of farmland and coal resources in Xuzhou, China. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2021;107:1065–1069. doi: 10.1007/s00128-021-03337-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wei J., Zheng X., Liu J., Zhang G., Zhang Y., Wang C., Liu Y. The levels, sources, and spatial distribution of heavy metals in soils from the drinking water sources of beijing, China. Sustainability. 2021;13:3719. doi: 10.3390/su13073719. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang Y., Wang L., Wang W., Li T., He Z., Yang X. Current status of agricultural soil pollution by heavy metals in China: a meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;651:3034–3042. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.10.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yuan X., Xue N., Han Z. A meta-analysis of heavy metals pollution in farmland and urban soils in China over the past 20 years. J. Environ. Sci. 2021;101:217–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2020.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shang E., Xu E., Zhang H., Huang C. Spatio-temporal variation and pollution source of heavy metals in arable land in China’s main producing areas. Environ. Sci. 2018;39:4670–4683. doi: 10.13227/j.hjkx.201802139. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang H., Shang E., Yu Z., Li H. Chinese Academy of Sciences; Beijing: 2019. Research on the Strategy for Improving Cultivated Land Quality in China (Arable Land Volume) [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Bureau of Statistics . China Statistics Press; Beijing: 2010. China Statistical Yearbook. [Google Scholar]

- 16.China National Environmental Monitoring Centre . China Environmental Press; Beijing: 1990. China Environmental Background Values of Soil. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gurevitch J., Hedges L.V. Statistical Issues in ecological meta-analyses. Ecology. 1999;80:1142–1149. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(1999)080[1142. SIIEMA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gates S. Review of methodology of quantitative reviews using meta-analysis in ecology. J. Anim. Ecol. 2002;71:547–557. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2656.2002.00634.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Challinor A.J., Watson J., Lobell D.B., Howden S.M., Smith D.R., Chhetri N. A meta-analysis of crop yield under climate change and adaptation. Nat. Clim. Change. 2014;4:287–291. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klümper W., Qaim M. A meta-analysis of the impacts of genetically modified crops. PLoS One. 2014;9:e111629. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knapp S., van der Heijden M.G.A. A global meta-analysis of yield stability in organic and conservation agriculture. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:3632. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05956-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li X., Zhang J., Ma J., Liu Q., Shi T., Gong Y., Yang S., Wu Y. Status of chromium accumulation in agricultural soils across China (1989–2016) Chemosphere. 2020;256 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.127036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shang Z., Abdalla M., Xia L., Zhou F., Sun W., Smith P. Can cropland management practices lower net greenhouse emissions without compromising yield? Global Change Biol. 2021;27:4657–4670. doi: 10.1111/gcb.15796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ren S., Song C., Ye S., Cheng C., Gao P. The spatiotemporal variation in heavy metals in China’s farmland soil over the past 20 years: a meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;806 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Michael B., Larry V.H., Julian P.T.H., Hannah R.R. Introd. Meta-Analysis. John Wiley and Sons Ltd Publication; United Kingdom: 2009. From narrative reviews to systematic reviews; pp. 21–24. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hedges L.V., Gurevitch J., Curtis P.S. The meta-analysis of response rations in experimental ecology. Ecology. 1999;80:1150–1156. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(1999)080[1150. TMAORR]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hedges L.V., Vevea J.L. Fixed- and random-effects models in meta-analysis. Psychol. Methods. 1998;3:486–504. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.486. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huedo-Medina T.B., Sánchez-Meca J., Marín-Martínez F., Botella J. Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I2 index? Psychol. Methods. 2006;11:193–206. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.11.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Begg C.B., J.A. B. Publication bias: a problem in interpreting medical data. J. R. Stat. Soc. Series A. 1988:419–463. doi: 10.2307/2982993. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rücker G., Schwarzer G., Carpenter J. Arcsine test for publication bias in meta-analyses with binary outcomes. Stat. Med. 2008;27:746–763. doi: 10.1002/sim.2971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Egger M., Davey Smith G., Schneider M., Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duval S., Tweedie R. A nonparametric “trim and fill” method of accounting for publication bias in meta-analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2012;95:89–98. doi: 10.1080/01621459.2000.10473905. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duval S., Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56:455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hou S., Zheng N., Tang L., Ji X., Li Y., Hua X. Pollution characteristics, sources, and health risk assessment of human exposure to Cu, Zn, Cd and Pb pollution in urban street dust across China between 2009 and 2018. Environ. Int. 2019;128:430–437. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang P., Chen H., Kopittke P.M., Zhao F.-J. Cadmium contamination in agricultural soils of China and the impact on food safety. Environ. Pollut. 2019;249:1038–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.03.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang Q., Li Z., Lu X., Duan Q., Huang L., Bi J. A review of soil heavy metal pollution from industrial and agricultural regions in China: pollution and risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2018;642:690–700. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.06.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rai P.K., Lee S.S., Zhang M., Tsang Y.F., Kim K.-H. Heavy metals in food crops: health risks, fate, mechanisms, and management. Environ. Int. 2019;125:365–385. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.01.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang L., Hou D., Cao Y., Ok Y.S., Tack F.M.G., Rinklebe J., O’Connor D. Remediation of mercury contaminated soil, water, and air: a review of emerging materials and innovative technologies. Environ. Int. 2020;134 doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.105281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zeng G., Wan J., Huang D., Hu L., Huang C., Cheng M., Xue W., Gong X., Wang R., Jiang D. Precipitation, adsorption and rhizosphere effect: the mechanisms for Phosphate-induced Pb immobilization in soils—a review. J. Hazard Mater. 2017;339:354–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Y., Hou D., O’Connor D., Shen Z., Shi P., Ok Y.S., Tsang D.C.W., Wen Y., Luo M. Lead contamination in Chinese surface soils: source identification, spatial-temporal distribution and associated health risks. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019;49:1386–1423. doi: 10.1080/10643389.2019.1571354. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shi T., Ma J., Zhang Y., Liu C., Hu Y., Gong Y., Wu X., Ju T., Hou H., Zhao L. Status of lead accumulation in agricultural soils across China (1979–2016) Environ. Int. 2019;129:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang S., Zhong T., Chen D., Zhang X. Spatial distribution of mercury (Hg) concentration in agricultural soil and its risk assessment on food safety in China. Sustainability. 2016;8:795. doi: 10.3390/su8080795. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu L., Zhang X., Zhong T., Wang S., Zhang W., Zhao L. Spatial distribution and risk assessment of copper in agricultural soils, China. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 2017;23:1404–1416. doi: 10.1080/10807039.2017.1320938. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gong Y., Qu Y., Yang S., Tao S., Shi T., Liu Q., Chen Y., Wu Y., Ma J. Status of arsenic accumulation in agricultural soils across China (1985–2016) Environ. Res. 2020;186 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao Q., Yu P., Mahendran R., Huang W., Gao Y., Yang Z., Ye T., Wen B., Wu Y., Li S., et al. Global climate change and human health: pathways and possible solutions. Eco-Environ. Health. 2022;1:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.eehl.2022.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schaeffer A., Wijntjes C. Changed degradation behavior of pesticides when present in mixtures. Eco-Environ. Health. 2022;1:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.eehl.2022.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hussain B., Ashraf M.N., Shafeeq-ur-Rahman, Abbas A., Li J., Farooq M. Cadmium stress in paddy fields: effects of soil conditions and remediation strategies. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;754 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zeng F., Ali S., Zhang H., Ouyang Y., Qiu B., Wu F., Zhang G. The influence of pH and organic matter content in paddy soil on heavy metal availability and their uptake by rice plants. Environ. Pollut. 2011;159:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Palansooriya K.N., Shaheen S.M., Chen S.S., Tsang D.C.W., Hashimoto Y., Hou D., Bolan N.S., Rinklebe J., Ok Y.S. Soil amendments for immobilization of potentially toxic elements in contaminated soils: a critical review. Environ. Int. 2020;134 doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.105046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dianwu Z., Jiling X., Yu X., Chan W.H. Acid rain in southwestern China. Atmospheric Environ. 1967. 1988;22:349–358. doi: 10.1016/0004-6981(88)90040-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu D., Shen Z., Dou C., Dou Z., Li Y., Gao Y., Sun Q. Effects of soil properties on heavy metal bioavailability and accumulation in crop grains under different farmland use patterns. Sci. Rep. 2022;12:9211. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-13140-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang S.-W., Jin J.-Y. Status of heavy metals in agricultural soils as affected by different patterns of land use. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2008;139:317–327. doi: 10.1007/s10661-007-9838-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bai L., Zeng X., Li L., Pen C., Li S. Effects of land use on heavy metal accumulation in soils and sources analysis. Agric. Sci. China. 2010;9:1650–1658. doi: 10.1016/S1671-2927(09)60262-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang Y., Zhou X., Tie B., Peng L., Li H., Wang K., Zeng Q. Comparison of three types of oil crop rotation systems for effective use and remediation of heavy metal contaminated agricultural soil. Chemosphere. 2017;188:148–156. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.08.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.National Soil Survey Office . China Agricultural Press; Beijing: 1964. Agricultural Soils in China. [Google Scholar]

- 56.National Soil Survey Office . vol. 1. China Agricultural Press; Beijing: 1993. Soil Species of China. [Google Scholar]

- 57.National Soil Survey Office . vol. 2. China Agricultural Press; Beijing: 1994. Soil Species of China. [Google Scholar]

- 58.National Soil Survey Office . vol. 3. China Agricultural Press; Beijing: 1994. Soil Species of China. [Google Scholar]

- 59.National Soil Survey Office . vol. 4. China Agricultural Press; Beijing: 1995. Soil Species of China. [Google Scholar]

- 60.National Soil Survey Office . vol. 5. China Agricultural Press; Beijing: 1995. Soil Species of China. [Google Scholar]

- 61.National Soil Survey Office . vol. 6. China Agricultural Press; Beijing: 1996. Soil Species of China. [Google Scholar]

- 62.National Soil Survey Office . China Agricultural Press; Beijing: 1998. Soils of China. [Google Scholar]

- 63.The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, China to Start 3rd Nationwide Soil Census. 2022. https://english.www.gov.cn/policies/latestreleases/202202/16/content_WS620caf99c6d09c94e48a51cb.html accessed July 22, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China (MEE), State Administration for Market Regulation. Standard for irrigation water quality; Beijing: 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 65.General Administration of Quality Supervision . Quality of farmland irrigation water; Beijing: 2007. Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China (AQSIQ), Standardization Administration, the Reuse of Urban Recycling Water. [Google Scholar]

- 66.State Administration for Market Regulation, Standardization Administration . 2018. Safety Threshold Values of Cadmium, Lead, Chromium, Mercury, and Arsenic in Upland Soils for Planting Rootstalk Vegetables. Beijing. [Google Scholar]

- 67.State Administration for Market Regulation, Standardization Administration . 2018. Safety Threshold Values of Cadmium, Lead, Chromium, Mercury, and Arsenic in Soil for Rice Production. Beijing. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sun Y., Li H., Lei S., Semple K.T., Coulon F., Hu Q., Gao J., Guo G., Gu Q., Jones K.C. Redevelopment of urban brownfield sites in China: motivation, history, policies and improved management. Eco-Environ. Health. 2022;1:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.eehl.2022.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Environmental Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ministry of Ecology and Environmentof the People’s Republic of China, the State Council of the People’s Republic of China, the Soil Contamination Prevention and Control Action Plan. 2016. https://www.mee.gov.cn/home/ztbd/rdzl/trfz/ accessed July 22, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 71.The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, the Soil Pollution Prevention and Control Law of the People’s Republic of China. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 72.The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, Outline of the 12th Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development. 2011. http://www.gov.cn/zhuanti/2011-03/16/content_2623428.htm accessed July 22, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 73.The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, Outline of the 13th Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development of the People’s Republic of China. 2016. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2016-03/17/content_5054992.htm accessed July 22, 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 74.The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, Outline of the 14th Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development of the People’s Republic of China and the Vision for 2035. 2021. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-03/13/content_5592681.htm accessed July 22, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chen X., Zhong H., Wang Q., Peng C., Yan S., Qin Q. Application and research progress of “VIP+n” remediation measures for heavy metal pollution of farmland in hunan province. Mod. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2019:149–150+152. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1007-5739.2019.06.085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Debra T., Dawn M. 2016. China’s Soil Ten, China Water Risk.https://www.chinawaterrisk.org/resources/analysis-reviews/chinas-soil-ten/ accessed July 28, 2022. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.