Abstract

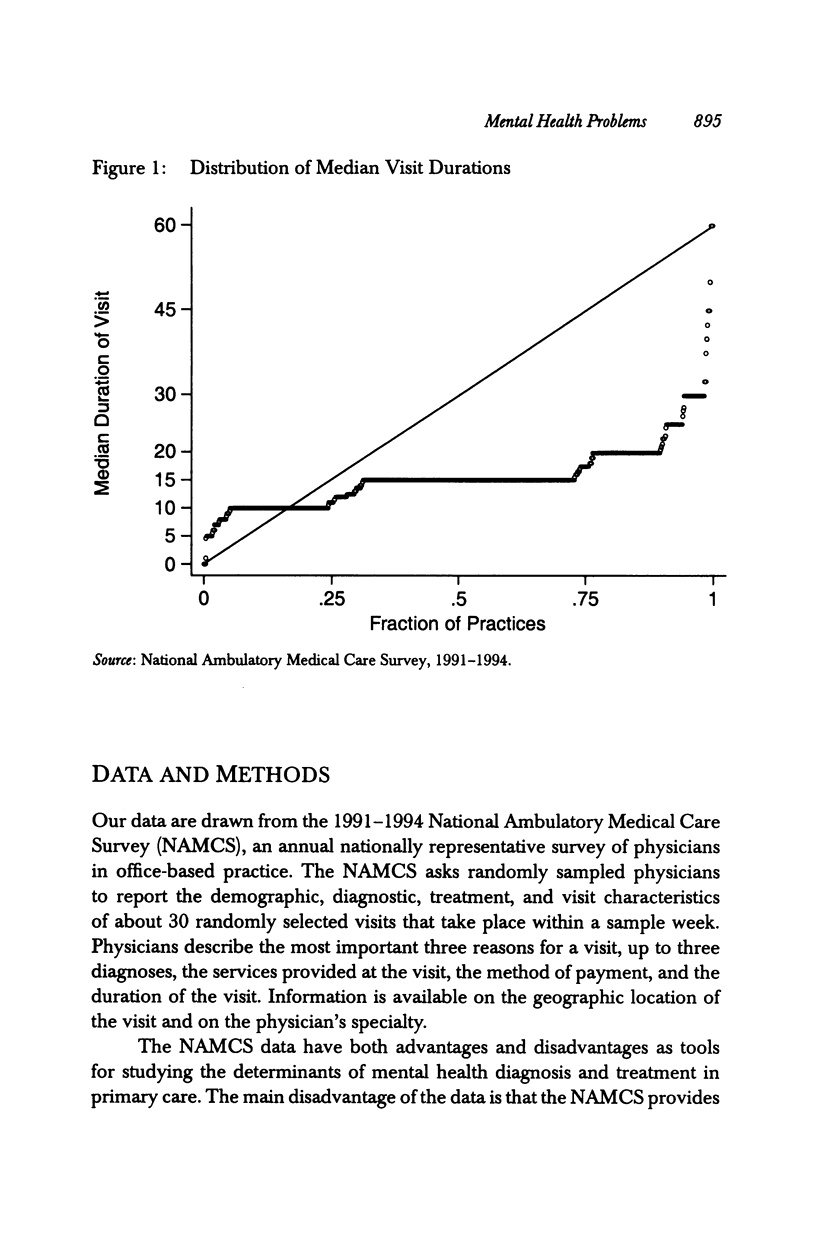

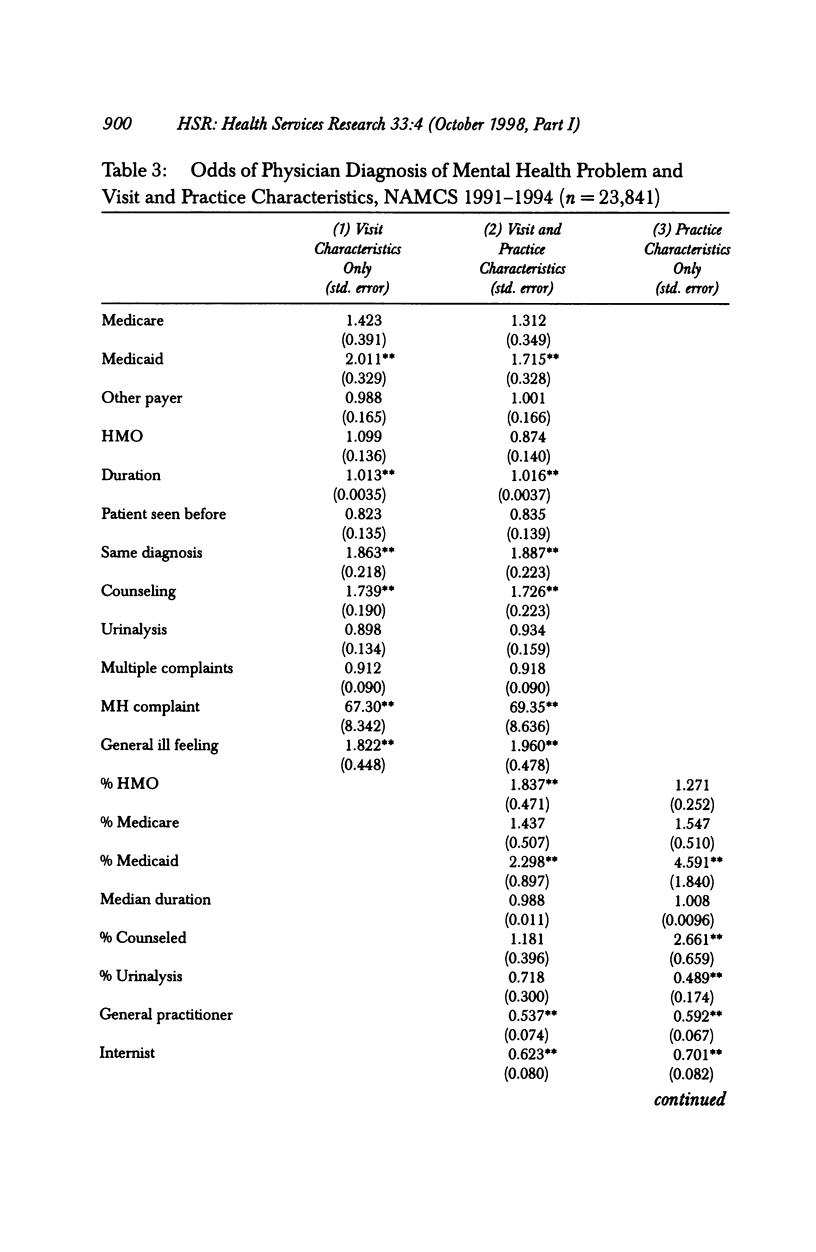

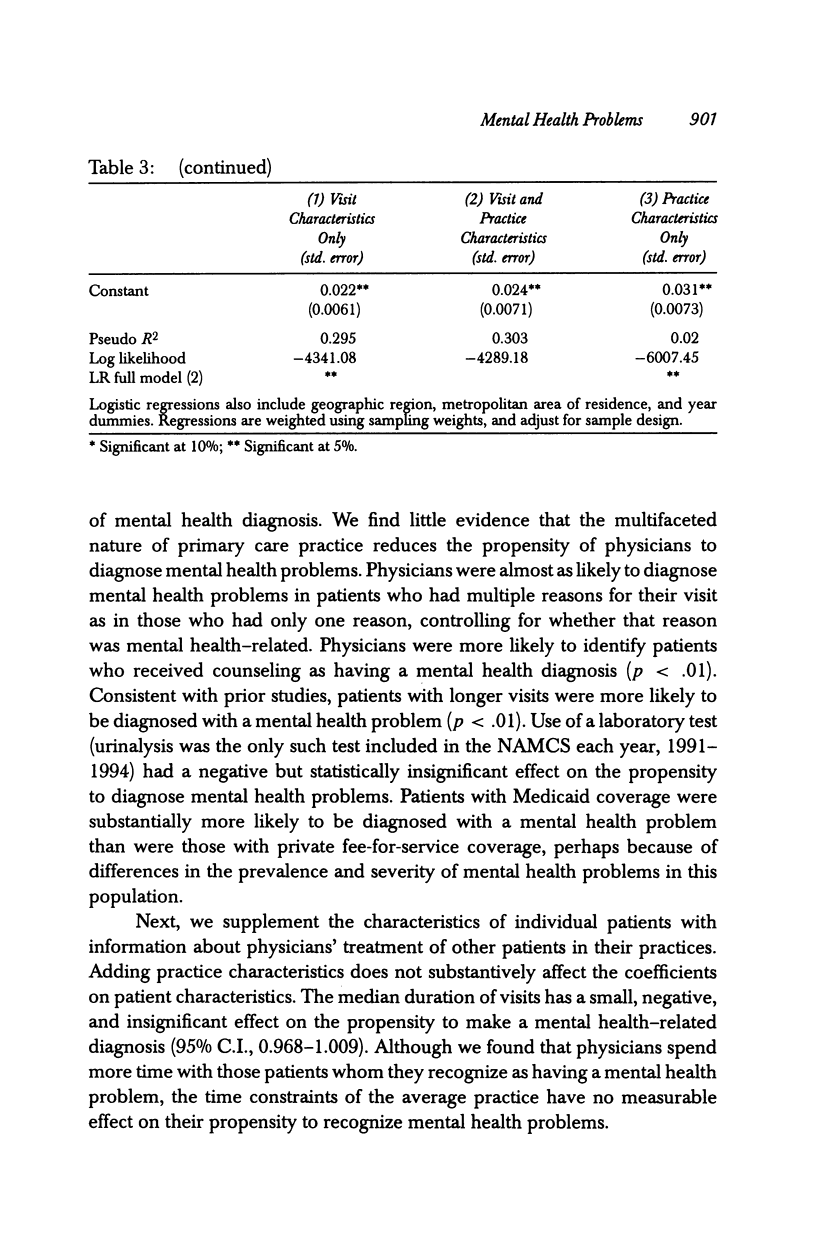

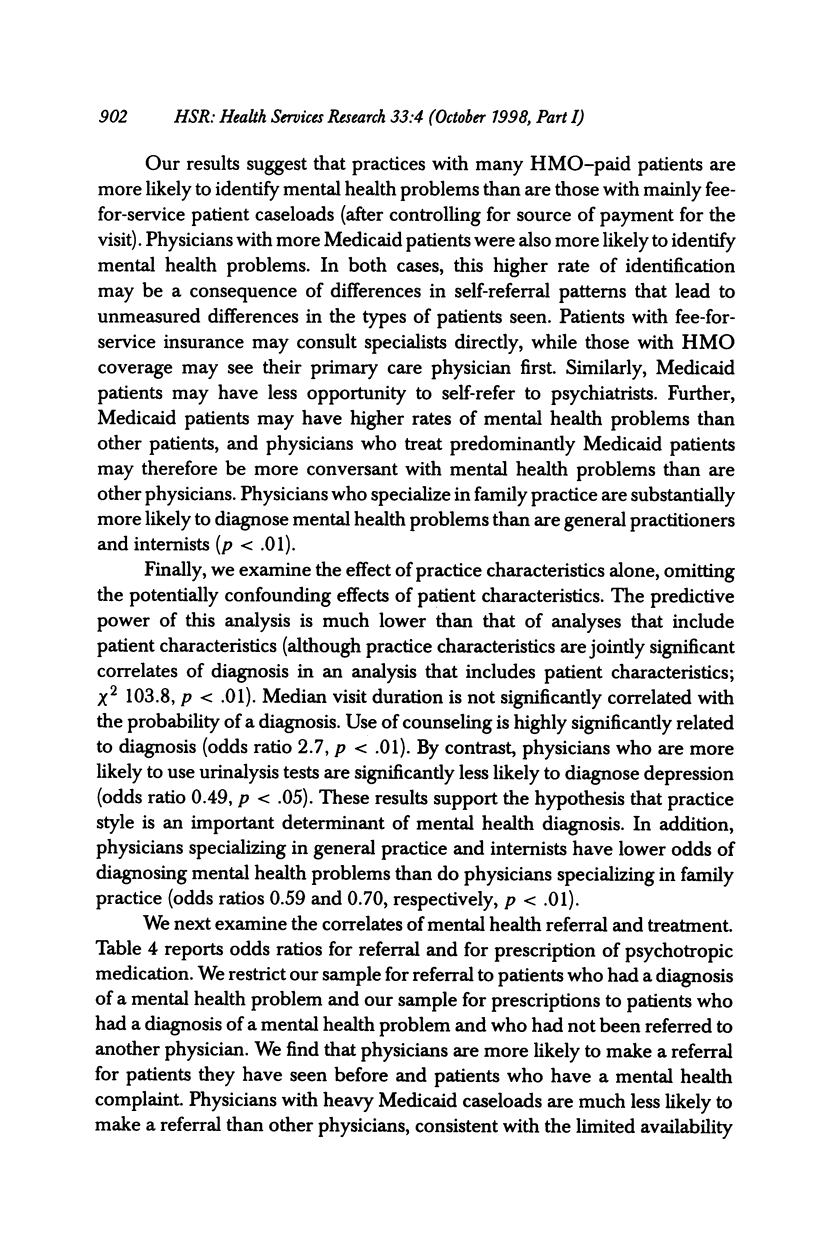

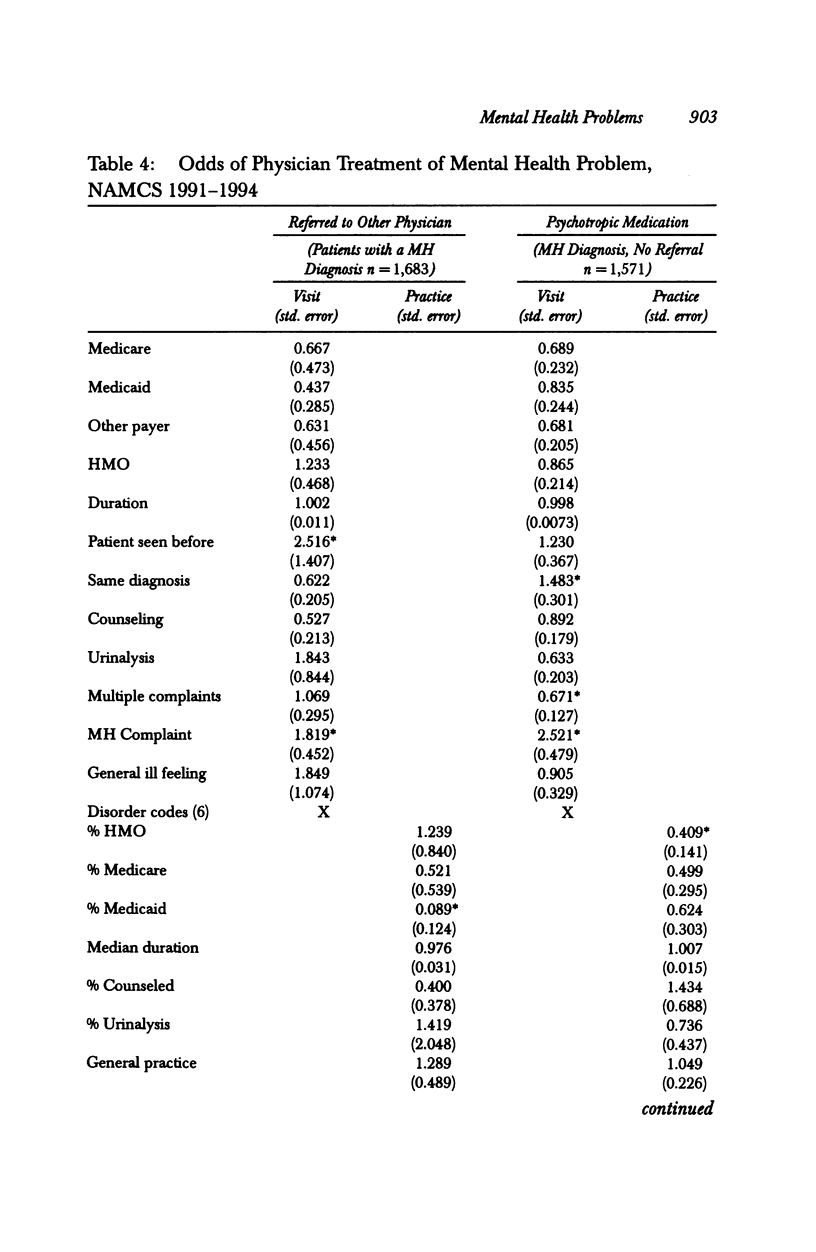

OBJECTIVES: To assess the effect of practice characteristics on the diagnosis and treatment of mental health problems in primary care. DATA SOURCE: National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) 1991-1994. STUDY DESIGN: We examine the effect of visit characteristics and practice characteristics on rates of diagnosis of mental health problems, rates of referral, and rates of use of psychotropic medications. We characterize each primary care physician's practice using information about the ways in which that physician treated patients who did not have mental health problems. PRINCIPAL FINDINGS: We find that median visit duration has a small, statistically insignificant effect on the rate of diagnosis and treatment of mental health problems. Physicians with large HMO caseloads are slightly more likely to diagnose mental health problems, but less likely to prescribe psychotropic medications, than are physicians who see few HMO patients. Practice style and specialty are important determinants of diagnosis and, to a lesser extent, of treatment. CONCLUSIONS: Physicians specialty and practice style are more strongly related to mental health diagnosis and treatment than are system characteristics such as visit duration and insurance composition.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Badger L. W., deGruy F. V., Hartman J., Plant M. A., Leeper J., Ficken R., Maxwell A., Rand E., Anderson R., Templeton B. Psychosocial interest, medical interviews, and the recognition of depression. Arch Fam Med. 1994 Oct;3(10):899–907. doi: 10.1001/archfami.3.10.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett J. E., Barrett J. A., Oxman T. E., Gerber P. D. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders in a primary care practice. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988 Dec;45(12):1100–1106. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800360048007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg L. Treating depression and anxiety in primary care. Closing the gap between knowledge and practice. N Engl J Med. 1992 Apr 16;326(16):1080–1084. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199204163261610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg D. P., Jenkins L., Millar T., Faragher E. B. The ability of trainee general practitioners to identify psychological distress among their patients. Psychol Med. 1993 Feb;23(1):185–193. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700038976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith J. C., Goran M. J. Managed care mythology: supply-side dreams die hard. Healthc Forum J. 1996 Nov-Dec;39(6):42-4, 46-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K. Discovering depression in medical patients: reasonable expectations. Ann Intern Med. 1997 Mar 15;126(6):463–465. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-6-199703150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaf P. J., Bruce M. L., Tischler G. L., Freeman D. H., Jr, Weissman M. M., Myers J. K. Factors affecting the utilization of specialty and general medical mental health services. Med Care. 1988 Jan;26(1):9–26. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198801000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaf P. J., Livingston M. M., Tischler G. L., Weissman M. M., Holzer C. E., 3rd, Myers J. K. Contact with health professionals for the treatment of psychiatric and emotional problems. Med Care. 1985 Dec;23(12):1322–1337. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198512000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemelin J., Hotz S., Swensen R., Elmslie T. Depression in primary care. Why do we miss the diagnosis? Can Fam Physician. 1994 Jan;40:104–108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Main D. S., Lutz L. J., Barrett J. E., Matthew J., Miller R. S. The role of primary care clinician attitudes, beliefs, and training in the diagnosis and treatment of depression. A report from the Ambulatory Sentinel Practice Network Inc. Arch Fam Med. 1993 Oct;2(10):1061–1066. doi: 10.1001/archfami.2.10.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks J. N., Goldberg D. P., Hillier V. F. Determinants of the ability of general practitioners to detect psychiatric illness. Psychol Med. 1979 May;9(2):337–353. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700030853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanic D. Treating mental illness: generalist versus specialist. Health Aff (Millwood) 1990 Winter;9(4):61–75. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.9.4.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers W. H., Wells K. B., Meredith L. S., Sturm R., Burnam M. A. Outcomes for adult outpatients with depression under prepaid or fee-for-service financing. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993 Jul;50(7):517–525. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820190019003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro S., German P. S., Skinner E. A., VonKorff M., Turner R. W., Klein L. E., Teitelbaum M. L., Kramer M., Burke J. D., Jr, Burns B. J. An experiment to change detection and management of mental morbidity in primary care. Med Care. 1987 Apr;25(4):327–339. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198704000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarlov A. R., Ware J. E., Jr, Greenfield S., Nelson E. C., Perrin E., Zubkoff M. The Medical Outcomes Study. An application of methods for monitoring the results of medical care. JAMA. 1989 Aug 18;262(7):925–930. doi: 10.1001/jama.262.7.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells K. B., Manning W. G., Jr, Valdez R. B. The effects of a prepaid group practice on mental health outcomes. Health Serv Res. 1990 Oct;25(4):615–625. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]