Abstract

Ambient particles severely threaten human health worldwide. Compared to larger particles, ultrafine particles (UFPs) are highly concentrated in ambient environments, have a larger specific surface area, and are retained for a longer time in the lung. Recent studies have found that they can be transported into various extra-pulmonary organs by crossing the air-blood barrier (ABB). Therefore, to understand the adverse effects of UFPs, it is crucial to thoroughly investigate their bio-distribution and clearance pathways in vivo after inhalation, as well as their toxicological mechanisms. This review highlights emerging evidence on the bio-distribution of UFPs in pulmonary and extra-pulmonary organs. It explores how UFPs penetrate the ABB, the blood-brain barrier (BBB), and the placental barrier (PB) and subsequently undergo clearance by the liver, kidney, or intestine. In addition, the potential underlying toxicological mechanisms of UFPs are summarized, providing fundamental insights into how UFPs induce adverse health effects.

Keywords: Ambient ultrafine particles, Bio-distribution of particles, Clearance pathways, Toxicity mechanisms

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Ambient UFPs are widely deposited in various pulmonary and extra-pulmonary organs.

-

•

Ambient UFPs have the potential to penetrate through ABB, BBB, and PB.

-

•

The predominant clearance pathway for ambient UFPs is by the kidney.

-

•

Ambient UFPs induce toxic effects through intricate and diverse mechanisms and pathways.

List of abbreviations

- ABB

air-blood barrier

- AD

Alzheimer disease

- Ag NPs

silver nanoparticles

- AKT

protein Kinase B

- AP-1

activator protein 1

- Apaf-1

apoptotic protease activating factor-1

- ARE

AU-rich element

- ATF4

activating transcription factor-4

- Au NPs

gold nanoparticles

- Aβ

β-amyloid

- Bax

BCL2 associated X

- BBB

blood-brain barrier

- CAT

catalase

- CB NPs

carbon black nanoparticles

- CeO2 NPs

cerium oxide nanoparticles

- CHD

coronary heart disease

- CHOP

C/EBP homologous protein

- CNS

central nervous system

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- CytC

cytochrome c

- DMT1

divalentmetal-iontransporter-1

- DSBs

DNA double-strand breaks

- eIF2α

eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- FA

filtered air

- FeNO

fractional exhaled nitric oxide

- FOXO3a

forkhead box O3

- GIT

gastrointestinal tract

- GSH

glutathione

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- HIF-1α

hypoxia inducible factor-1α

- HR

hazard ratio

- HSPA5

heat shock protein family A member 5

- IKK

IκB kinase

- IP3R

inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate receptor

- IRE

inositol requiring enzyme

- Itgam

integrin alpha M

- Keap1

Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- LFs

lung fibrocytes

- LT-MC

long-term mediated pathway of alveolar macrophages

- M cells

microfold cells

- MCP-1

monocyte chemotactic protein-1

- MDA

malondialdehyde

- miR-210

microRNA 210

- MnO2 NPs

manganese oxide nanoparticles

- NADPH

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- NCOA4

nuclear receptor coactivator 4

- NF-κB

nuclear factor kappa-B

- Ni NPs

nickel nanoparticles

- NO2

nitrogen dioxide

- Nrf2

Nuclear factor-E2-related factor-2

- O3

ozone

- PB

placental barrier

- PERK

double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase-like ER kinase

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- PKR

double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase

- PM10

ambient inhalable particles

- PM2.5

ambient fine particles

- PNC

particle number concentration

- QDs

quantum dots

- Rad52

DNA repair protein RAD52 homolog

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- STEAP3

six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of prostate 3

- TiO2 NPs

titanium dioxide nanoparticles

- UFPs

ultrafine particles

- WHO

World Health Organization

- XBP-1

X-box binding protein 1

- ZnO NPs

zinc oxide nanoparticles

- γH2AX

phosphorylated H2AX

1. Introduction

Air pollution is one of the major global public health concerns. In 2021, the World Health Organization (WHO) released updated global air quality guidelines, which lowered reference values for most air pollutants, including ambient particles, ozone (O3), and nitrogen dioxide (NO2), with the intention of urging countries worldwide to implement related policies to further reduce air pollution [1,2]. As mentioned in the new guidelines, ambient ultrafine particles (UFPs) are recommended to be quantified according to the particle number concentration (PNC). In addition, it is important to distinguish between low and high PNC levels in order to determine which sources of UFPs should be prioritized for emission control. The suggested threshold for low PNC is less than 1,000 particles/cm3 (24-h mean), while high PNC is greater than 10,000 particles/cm3 (24-h mean) or 20,000 particles/cm3 (1-h mean). Thus, it is necessary to pay special attention to the adverse health outcomes caused by UFPs, and actions such as UFPs monitoring should be taken [1,2].

UFPs are widely dispersed in the atmosphere, with complex compositions and various sources, including marine aerosols and natural events such as forest fires, motor vehicle exhaust, factory exhaust, and kitchen fumes in the combustion process [3]. Meanwhile, UFPs from engineering processes, such as carbon powder, engineering materials, and microelectronics, are referred to as nanoparticles. Some toxicological studies have used engineered nanoparticles as models, as they are more stable and easier to control compared to naturally occurring UFPs, which are more dispersed and have complex compositions [4,5]. However, it is essential to acknowledge their differences. The size, composition, shape, surface charge, and coating of nanoparticles may influence their distribution, clearance pathways, and toxic effects in organisms [6]. Especially engineered nanoparticles and naturally occurring particles may differ greatly in chemical properties. The composition of environmental particles in the real world is generally heterogeneous, complex, and varies in different environments, while engineered nanoparticles are often made of single-components [7]. Thus, attention should be paid while using engineered nanoparticles to represent ambient UFPs [8]. To minimize the impacts of these differences, engineered nanoparticles with appropriate properties should be chosen based on the research objectives in combination with the actual environmental conditions.

Ambient particulate matter is usually classified according to its aerodynamic diameter, including inhalable particulate matter (PM10, indicating particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter less than or equal to 10 μm), fine particulate matter (PM2.5, indicating particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter less than or equal to 2.5 μm), and ultrafine particulate matter (PM0.1 or UFPs, indicating particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter less than or equal to 0.1 μm). Size is a critical factor when considering the toxicity of particulate matter [9]. Recently, several studies have confirmed that, compared to PM2.5, UFPs may induce a more severe lung inflammatory response and tissue remodeling [10]. Meng et al. reported that particles smaller than 0.5 μm in diameter might be the most significant cause of adverse health effects attributable to ambient particles [11]. Due to their small size, it has been believed that UFPs have unique distribution and clearance modes within the organism and can disturb cellular functions through several signaling pathways [4].

While there have been some previous reviews on UFPs, most of them have focused on the sources, exposure routes, toxicity, or a specific health outcome of a certain type of UFP. Few have mentioned the bio-distribution and clearance pathways of UFPs in the organism, especially the inhaled UFPs. This review thus aims to fill the gap by providing a comprehensive and in-depth summary of the various health effects, bio-distribution, clearance patterns, and toxicological mechanisms of UFPs after inhalational exposure, hoping to provide readers with a systemic and insightful understanding of the latest research developments in the field of UFPs as well as a prospect of future research directions. As mentioned above, considering that some engineered particles are applied in toxicological studies as models of ambient UFPs, studies using nanoparticles for inhalation exposure are also included in this article.

2. Study selection

The present study used the PubMed search engine, one of the most authoritative and widely used biomedical literature databases, for literature searches. The search strategy was optimized using Boolean logical operators and "AND/OR" combined with keyword sets and restriction terms. According to the framework of this review, we first searched for different health effects of UFPs, then quickly assessed whether the articles met the search requirements by examining the title and abstract, and further divided the qualified articles into epidemiological and toxicological studies. To ensure the quality of the selected articles, the following exclusion criteria were established: (1) exclude studies that are not focused on ambient ultrafine particles or engineered particles for inhalational exposure; (2) exclude duplicate studies from multiple searches; (3) exclude studies with design flaws; (4) exclude studies with incomplete data; (5) for epidemiological studies, exclude studies with statistical method errors; (6) for toxicological studies, exclude studies with unclear outcomes.

In total, we have conducted nine searches, including: (1) “ultrafine particles” or “PM0.1” or “nanoparticles” and “respiratory system”; (2) “ultrafine particles” or “PM0.1” or “nanoparticles” and “cardiovascular system”; (3) “ultrafine particles” or “PM0.1” or “nanoparticles” and “digestive system”; (4) “ultrafine particles” or “PM0.1” or “nanoparticles” and “central nervous system”; (5) “ultrafine particles” or “PM0.1” or “nanoparticles” and “internal distribution”; (6) “ultrafine particles” or “PM0.1” or “nanoparticles” and “clearance” or “metabolism” or “transfer”; (7) “ultrafine particles” or “PM0.1” or “nanoparticles” and “blood-brain barrier” or “BBB”; (8) “ultrafine particles” or “PM0.1” or “nanoparticles” and “placental barrier” or “PB”; (9) “ultrafine particles” or “PM0.1” or “nanoparticles” and “toxicity mechanisms” or “action modes.”

All searches were restricted to publications after 2000, with the language limited to English. A total of 116 research papers were included in this review. For background knowledge or professional terms mentioned in this review, supplementary searches were performed accordingly.

3. Adverse health effects of ambient ultrafine particles

3.1. Pulmonary effects

An increasing number of epidemiological and toxicological studies have reported that UFPs can induce significant adverse effects in the lung, the primary target organ of inhaled particles (Table 1). For example, Strak et al. reported that for every 33,000 particles/cm3 increase in the PNC of UFPs, the fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) level, a biomarker of airway inflammation widely used in the diagnosis and monitoring of respiratory diseases, increased by approximately 12% [12]. In addition, UFPs may aggravate the condition of patients with respiratory diseases. For example, studies have demonstrated that exposure to UFPs is strongly associated with reduced lung function, increased systemic inflammation, and an increased risk of respiratory symptoms in adult asthmatics [13,14]. Notably, prenatal exposure to UFPs may also affect fetal health. A recent study found that prenatal exposure to UFPs was associated with asthma development in children [15].

Table 1.

Summary of the epidemiological studies on the adverse health effects of ambient UFPs.

| Targeting system | Method | Effect | Indicator | Main results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory system |

Randomized crossover study | Asthma in adulthood | FEV1 | Exposure to UFPs was considerably associated with FEV1 (HR = −1.52, 95% CI: −2.28, −0.77). | [13] |

| Cohort study | Asthma during childhood | Asthma incidence | During the entire pregnancy period, the risk of childhood asthma exacerbation increased by a OR of 4.28 (95% CI: 1.41, 15.7) for every doubling of exposure concentration to UFPs. | [15] | |

| Semiexperimental design | Acute airway inflammation | FeNO | For every increase of one IQR in UFPs (33,000 particles/cm3), there is a corresponding increase of 11% (95% CI: 5%, 17%) in FeNO levels immediately after exposure and 12% (95% CI: 6%, 17%) in FeNO levels 2 h after exposure relative to the baseline. | [12] | |

| Cohort study | COPD | COPD incidence | Each IQR increase in ambient UFPs was associated with incident COPD (HR = 1.06, 95% CI: 1.05, 1.09). However, when adjusted for NO2, the association weakened, and the HR no longer increased (HR = 1.01, 95% CI: 0.98, 1.03). | [16] | |

| Cohort study |

Respiratory disease |

Respiratory mortality |

There was a delayed and prolonged association between UFPs and increased respiratory system mortality (9.9%, 95% CI: −6.3%, 28.8%), which was associated with an average increase of 2,750 particles/cm3 over 6 days. |

[17] |

|

| Cardiovascular system |

Cohort study | Cardiovascular disease | Cardiovascular mortality | The association between UFPs and ischemic heart disease mortality was the strongest (daily increase in mortality rate of 7.1%, 95% CI: 2.9%, 11.5%, for every increase of 6,250 particles/cm3). | [24] |

| Cross-sectional study | Microvascular dysfunction | MVF | Personal exposure to UFPs during outdoor activities was significantly negatively correlated with MVF (decreased by 1.3% per IQR, 95% CI: 0.1%, 2.5%) and pulse amplitude, and positively correlated with leukocyte and neutrophil counts. | [27] | |

| Cross-sectional study | Microvascular dysfunction | MVF | There was a significant negative correlation between MVF and outdoor UFPs (MVF decreases by 9% for every increase in IQR value). | [28] | |

| Cross-sectional study |

Cardiovascular disease |

CRP |

An increase in the IQR (2,000 particles/cm3) of UFP was associated with a 6.3% increase (95% CI: 0.4%, 12.5%) in high sensitivity CRP levels. |

[25] |

|

| Digestive system |

Cohort study |

liver cancer |

Liver cancer incidence |

Positive linear association was observed between black carbon [HR = 1.15, 95% CI: (1.00, 1.33) per 0.5 × 10−5/m] and liver cancer incidence. |

[41] |

| Central nervous system | Cohort study | Malignant brain cancer | Malignant brain cancer mortality | The overall risk of malignant brain cancer increased by 12% (95% CI: −2%, 27%) among all participants with each IQR increase in airport-related UFP exposure (6,700 particles/cm3). | [56] |

| Cohort study | Incident brain tumors | Brain tumors incidence | After adjusting for confounding factors, there was a positive correlation between UFPs and incidence of brain tumors, with a HR of 1.133 (95% CI: 1.032, 1.245) for every increase of 10,000/cm3 | [57] | |

| Case-crossover design | Ischemic stroke | Hospitalization for ischemic stroke | Exposure to UFPs lead to a 21% increase (95% CI: 4%, 41%) in the number of hospitalizations for mild ischemic stroke without AF. | [58] |

AF, atrial fibrillation; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 sec; IQR, interquartile range; MVF, microvascular function; OR, odds ratio.

In contrast, several studies have reported no positive associations between exposure to UFPs and respiratory diseases independent of other air pollutants. For example, a cohort study found that the association between UFPs and the incidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease lost statistical significance after adjusting for the covariate of NO2 [16]. Likewise, a cohort study conducted in five European cities observed positive but not statistically significant associations between prolonged exposure to UFPs and respiratory mortality [17]. Comparing results across different studies on the health effects of UFPs is challenging due to inconsistencies in approaches for measuring UFP size and variables included in the statistical models. As discussed previously [16], different models are utilized for different air pollutants, which may result in errors when assessing the association between UFPs and respiratory diseases, and the inclusion or exclusion of variables can significantly affect study results. Furthermore, differences in the study location or population can also contribute to inconsistent findings since different groups of people may vary in susceptibility to diseases, and the sources or/and components of UFPs may differ across regions. Overall, the epidemiological evidence on the pulmonary effects of UFPs remains limited, and more multi-center studies are necessary to achieve solid conclusions.

Studies have shown that compared with PM2.5, UFPs have a longer residence time after being deposited in the lung, possibly causing more serious adverse health effects [18]. In a mouse model, it was found that UFPs induce more severe chronic pulmonary inflammation, alveolar wall thickening, and macrophage infiltration than PM2.5 [10]. Similar to epidemiological findings, toxicological studies have found that prenatal exposure to UFPs suppressed the immune response of the offspring’s lungs, making them more susceptible to respiratory infections [19], as shown in Table 2. Various pollutants existing in real-world environments may also interact with each other and affect the toxic effects. For example, co-exposure to UFPs and O3 has been proven to enhance the biological effects of UFPs by exacerbating airway damage and inflammatory responses [20].

Table 2.

Summary of the toxicological studies on the adverse health effects of ambient UFPs.

| Targeting system | PM source or material | Particle size | Animal model | Exposure method | Effect | Potential toxicological mechanisms | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory system |

Ambient sampling | 188 nm (average) | BALB/c mice | Nasal instillation | Chronic pneumonia | Il-6, Il-1b, Il-10 increase Cyp1a1, Cyp1b1 increase |

[10] |

| CuO NPs | 200 nm (average) | C57BL/6 mice | Intratracheal instillation | Acute lung injury | T cell subset imbalance | [134] | |

| CB NPs | 40 nm (average) | C57BL/6 mice | Whole-body exposure | Small airway obstruction | CC16 decrease SP-A increase |

[135] | |

| Ambient sampling |

50 nm (average) |

C57BL/6 mice BALB/c mice |

Whole-body exposure |

Offspring pulmonary immunosuppression |

Th2-driven pulmonary inflammation decrease |

[19] |

|

| Cardiovascular system |

DEP | 24 nm (average) | Rat cardiomyocytes | Cellular contamination | Cardiomyocyte dysfunction | The reduction in contractility and calcium handling in cardiomyocytes | [36] |

| Ambient sampling | <100 nm | Sprague Dawley rat | Intratracheal instillation | Cardiac I/R injury | mPTP Ca2+ Sensitization | [136] | |

| Ambient sampling | 76 nm (average) | C57BL/6 mice | Whole-body exposure | Cardiac arrhythmias | GTR decrease Cardiac contractility decrease |

[29] | |

| Ambient sampling | <60 nm | C57BL/6 mice | Intratracheal instillation | Offspring hypertension | Alterations in methylation of promoter regions of RAS-related elements | [33] | |

| Road traffic | <180 nm | ApoE−/− mice | Whole-body exposure | Atherosclerosis | Activates the Nrf2 signaling | [34] | |

| Road traffic | 45 nm (average) | Ldlr−/− mice | Whole-body exposure | Vascular calcification | Activates the NF-κB signaling | [37] | |

| Road traffic | 45 nm (average) | Ldlr−/− mice | Whole-body exposure | Atherosclerosis | Lipid metabolism and HDL dysfunction | [35] | |

| Ambient sampling |

<100 nm |

C57BL/6 mice |

Thoracic aorta exposure |

Impaired vasomotor responses |

Oxidative stress Loss of anti-oxidant defenses |

[137] |

|

| Digestive system |

CB NPs | 100 nm (average) | C57BL/6 mice | Oral administration | Acute hepatitis | ROS, CAT increase | [42] |

| CB NPs | 51 nm (average) | C57BL/6 mice hepatocytes | Cellular contamination | Hepatocytes apoptosis | ROS increase Lipid peroxidation increase |

[44] | |

| CB NPs | 35 nm (average) | C57BL/6 mice | Intravenous injection | Hepatic genotoxicity | Oxidative DNA damage | [47] | |

| Road traffic | 82 nm (average) | Ldlr-null mice | Whole-body exposure | Gastrointestinal inflammation | The levels of oxidized fatty acids and LPA in intestine increase | [50] | |

| Road traffic | 45 nm (average) | Ldlr−/− mice | Oral administration | Intestinal microbial composition disorders | LPC 18:1 level increase | [51] | |

| Ambient sampling |

66 nm (average) |

C57BL/6 mice |

Whole-body exposure |

Lipid metabolism disorders |

Activate the FXR/LXR and Hnf4a signaling |

[52] |

|

| Central nervous system | Ambient sampling | Natural occurreda | C57BL/6 mice | Whole-body exposure | AD | Amyloid deposition, tangles, and plaque increase | [54] |

| Fuel combustion | 178 nm (average) | C57BL/6 mice | Whole-body exposure | AD | Perturbation in hippocampal redox homeostasis | [59] | |

| Road traffic | 83 nm (average) | 3xTgAD mice | Whole-body exposure | AD | Neuroinflammation | [60] | |

| BB and DEP | <50 nm | BALB/c mice | Intratracheal instillation | Neurodegeneration | HO-1, Hsp70, Cyp1b1 increase iNOS, COX-2 increase | [62] | |

| Diesel Exhaust | <100 nm | Fischer rats | Whole-body exposure | Neuroinflammation | TNFα, α Synuclein, Aβ42 increase Tau hyperphosphorylation |

[63] | |

| Ambient sampling | Natural occurreda | B6C3F1 hybrid mice | Whole-body exposure | Neurodevelopmental disorders | Enlarged brain ventricles, increased corpus callosum area, decreased hippocampal | [64] |

Aβ42, β-amyloid (1–42); BB, biomass burning-derived; CC16, clara cell secretory protein; COX-2, cyclooxygenase 2; Cyp1b1, Cytochrome P450 1b1; DEP, diesel exhaust particles; FXR, farnesoid X receptor; GTR, glutathione S-transferase; Hnf4a, hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha; HO-1, heme oxygenase-1; Hsp70, heat-shock protein 70; I/R, cardiac ischemia/reperfusion; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; LPA, lysophosphatidic acids; LPC 18:1, lysophosphatidylcholine; LXR, liver X receptor; mPTP, mitochondrial permeability transition pore; RAS, renin-angiotensin system; SP-A, lung surface viability protein A; Tau, microtubule-associated protein tau; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor-α.

Particle size is not presented in this study.

3.2. Extra-pulmonary effects

In recent years, increasing evidence has shown that UFPs deposited in the lung may enter circulation by penetrating the air-blood barrier (ABB) and subsequently translocating to extra-pulmonary organs, inducing health risks to the cardiovascular, digestive, nervous systems, and so forth [9]. In addition, UFPs can penetrate the blood-brain barrier (BBB) or placental barrier (PB), causing toxic effects on brains or fetuses [21,22].

3.2.1. Effects on the cardiovascular system

The cardiovascular system, also known as the “circulatory system,” plays an important role in maintaining normal physiological functions in the body. It is reported that cardiovascular diseases account for 40%–60% of premature mortality due to air pollution, and UFPs from vehicle exhaust are one of the most critical contributors [23], as shown in Table 1. A cohort study conducted in China reported that concentrations of UFPs were strongly correlated with cardiovascular mortality, with a 7.1% (95% CI: 2.9%, 11.5%) increase in mortality from ischemic heart disease for every 6,250 particles/cm3 increase in daily average UFP concentration [24]. In addition, long-term exposure to UFPs can result in elevated levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), a well-known biomarker of coronary heart disease (CHD) [25,26]. Cross-sectional studies suggested that ambient UFP concentration was associated with decreased microvascular function [27,28]. Moreover, the co-exposure effects of UFPs with other pollutants should be noted. For example, arrhythmias may be induced when exposed to O3 and UFPs [29]. Evidence suggests that UFPs may cross the placental barrier and deposit on the fetal side [30]. Therefore, UFPs may not only disturb the development and morphology of the placenta [31,32] but also have harmful effects on the offspring. For example, in-utero exposure to UFPs has been found to induce increased susceptibility to cardiovascular diseases such as elevated blood pressure among offspring [33].

Toxicological studies have also associated UFP pollution with several endpoints underpinning cardiovascular conditions (Table 2). For example, by assessing the condition of atherosclerosis and the anti-inflammatory activity of high-density lipoprotein (HDL), it was found that exposure to UFPs induced significant early atherosclerotic lesions compared with PM2.5 or the filtered air (FA) group [34]. Studies using Ldlr−/− mice, a widely used model of atherosclerosis, reported that UFP exposure promotes atherosclerosis, disturbs lipid metabolism, and dramatically reduces the antioxidant capacity of HDL [35]. Using in vitro models, it was found that UFPs are capable of directly and indirectly inducing cardiomyocyte dysfunctions, such as impairing cardiomyocyte contractility, calcium regulation, and response to epinephrine stimulation and promoting vascular calcification via monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) [36] or nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) signaling pathways [37].

3.2.2. Effects on the digestive system

The adverse health effects of ambient particles on digestive organs, such as the gastrointestinal tract and liver, have been reported in both epidemiological and toxicological studies [[38], [39], [40]], as shown in Table 1, Table 2. A recent study including six cohorts from five countries reported a positive association between exposure to carbon black nanoparticles (CB NPs) and liver cancer incidence [41]. Using in vivo and in vitro models, CB NPs have been shown to induce acute inflammation in the liver and change the architecture and viability of hepatocytes [42,43]. Further studies using different types of nanoparticles and animal exposure methods showed that hepatic genotoxicity was directly induced by the translocated nanoparticles in the liver rather than by the secondary effects of pulmonary inflammation or the hepatic acute phase response [44]. In addition, various nanoparticles with different chemical properties, including titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2 NPs), cerium oxide nanoparticles (CeO2 NPs), and manganese oxide nanoparticles (MnO2 NPs), have been shown to be hepatotoxic and even carcinogenic [[45], [46], [47], [48], [49]].

Exposure to UFPs has a prominent effect on the intestine. Studies have shown that UFP exposure induces an inflammatory response in the intestine, alters intestinal microbiota, and disturbs lipid metabolism [50,51]. As a vital and intricate process for maintaining the normal physiological function of the body, lipid metabolism in the placenta is found to be disturbed by UFPs exposure during pregnancy, suggesting that UFPs may have adverse effects on the lipid metabolism of offspring [52].

3.2.3. Effects on the central nervous system

Studies have shown that UFPs may deposit in the brain and affect the central nervous system (CNS) [53,54]. However, there are conflicting opinions about whether UFPs enter the brain through the BBB (from the lung via the ABB to the circulation) or the nasal cavity along the olfactory nerve from the olfactory bulb [21,55]. Most of the epidemiological evidence linking UFPs to brain diseases is obtained from cohort studies (Table 1). For instance, a multi-ethnic cohort study showed that regardless of race, exposure to UFPs is a potential risk factor for malignant brain cancer [56]. In this study, African Americans, the subgroup with the highest exposure, showed a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.32 (95% CI: 1.07, 1.64) for malignant brain cancer per interquartile range of UFP exposure [56]. A Canadian cohort study also supports these findings, in which, after adjusting for PM2.5, NO2, and sociodemographic factors, an increase in UFPs concentration by 10,000 particles/cm3 was positively associated with the incidence of brain tumors (HR = 1.112; 95% CI: 1.042, 1.188) [57]. A time-stratified case-crossover design study reported that exposure to UFPs resulted in a 21% increase in the number of hospitalizations for mild ischemic stroke (average of 5 days in each quartile range; 95% CI: 4%, 41%) [58].

As major pathological hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), β-amyloid (Aβ), neurofibrillary tangles, and plaques were found to be significantly upregulated in the brains of UFPs-exposed mice [54,59]. Using an AD mouse model (3xTgAD), Herr et al. also found that Aβ levels were elevated in the hippocampus after exposure to UFPs [60]. Studies have shown that UFPs may affect the CNS through both direct and indirect pathways. Except for direct deposition in the brain, some inhaled UFPs in primary deposit organs, such as the lung, may induce soluble inflammatory mediators [61]. These mediators are transported to the brain through the circulation, resulting in increased susceptibility to neuroinflammation or neurodegeneration and potentially contributing to the development of neurodegenerative diseases like AD [62,63]. Additionally, animal studies have shown that exposure to UFPs during pregnancy can also induce CNS dysfunctions in offspring after birth, including enlarged brain ventricles, increased corpus callosum area, and decreased hippocampal area, which are all typical features of neurodevelopmental disorders [64]. All the findings indicate that UFPs may have broad and detrimental effects on both the placenta and offspring, highlighting the importance of avoiding periconceptional exposure to UFPs and conducting a more in-depth and comprehensive investigation into the health effects of UFPs.

4. Bio-distribution and clearance of ambient ultrafine particles in vivo

4.1. Bio-distribution of ambient ultrafine particles within the body

Ambient particles can be absorbed into the body through the respiratory system, skin, eyes, or gastrointestinal tract, with the respiratory system being the most dominant exposure pathway [18]. Inhaled particles are widely distributed in the body and are first deposited in the nasopharynx. The majority of PM10 is deposited in the respiratory mucosa and upper airways, whereas PM2.5 and UFPs reach the pulmonary alveoli. A study in Germany found that intratracheally inhaled nanoparticles (Au NPs) were mainly deposited in the lower part of the lung [65]. To better explore the real-time within-body deposition patterns of inhaled UFPs, researchers used two-photon microscopy and reported that the deposition of 200 nm particles in the lung was mainly influenced by Brownian motion, which leads to an even distribution in the lung with the highest concentration in the bronchial region [66].

After deposition in the lung, UFPs may penetrate the ABB and reach extrapulmonary organs through circulation, as shown in Fig. 1a [67,68]. For example, both real-time observation and analysis of frozen sections have shown that nanoparticles can migrate from the lung to mediastinal lymph nodes [6]. Swiss scholars also reported that the size of nanoparticles affects the uptake of particles by antigen-presenting cells in the lung and their migration to the lymph node region [69]. Furthermore, intratracheally instilled TiO2 NPs were observed in the heart and liver tissues of a mouse model, and the number of particles in the liver was higher than that in the heart [70]. As expected, many studies have shown high retention of UFPs in the liver, probably because the liver is one of the most important metabolic organs [[71], [72], [73]].

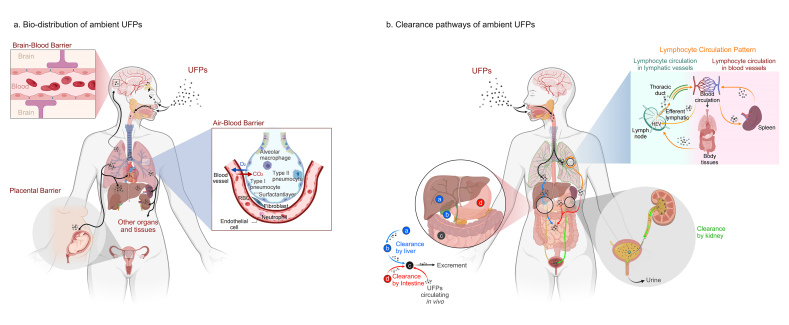

Fig. 1.

Bio-distribution and clearance pathways of ambient UFPs in the body. After inhaling via the respiratory system, UFPs are first deposited in the lung, and then they may penetrate the ABB and be deposited in extra-pulmonary organs such as the heart, liver, kidney, and spleen through blood circulation. In addition, UFPs in the circulation may also penetrate the BBB and PB, leading to deposition in the brain and placenta. It is worth noting that there is also a nasal olfactory pathway regarding the deposition of UFPs in the brain. The main clearance pathway of UFPs in the body is by the kidney, with the vast majority of particles excreted in urine. In addition, clearance by liver and gastrointestine also plays an important role in some cases. The lymphatic circulation also plays an essential role in the clearance process of UFPs in vivo.

Ambient UFPs have also been observed in the brain, but the mechanistic pathway of their transfer remains unclear [53]. Two primary theories have been proposed. As shown in Fig. 1a, the first theory is that UFPs in circulation can penetrate the BBB to reach the brain, which may alter the structure of the BBB and increase its permeability. The second theory is that after being inhaled in the nasal cavity, UFPs may damage the olfactory neurons and translocate from the olfactory bulb into the brain via the olfactory nerve [21,55,74]. Further studies are needed to clarify the specific migration pathways of UFPs into the brain [[75], [76], [77], [78]].

Increasing evidence has shown that UFPs are found in the placenta of human and animal models, yet whether UFPs penetrate the PB and transfer to the fetus is not well understood [79,80]. Recently, it was found that UFPs from maternal exposure can be deposited in fetal tissues, including the liver, lung, and kidney [22]. In addition, in vitro studies validated the possibility of UFPs being deposited in the embryo through the PB using a human placenta model [81,82]. However, several other studies have also reported contradictory results. For example, Austin et al. reported that maternal exposure to silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs) leads to almost no deposition in the embryo but extremely high concentrations of nanoparticles in the maternal yolk sac [83].

4.2. Clearance pathways of ambient ultrafine particles

The clearance pathways of UFPs differ in different organs and tissues. Studies have found that the main clearance modes of UFPs in the nasal cavity, trachea, and bronchi are the mucociliary system and epithelial endocytosis; particles in the bronchi can also be cleared by lymphatic drainage [84]. After deposition in the lungs, the most important clearance pathway for UFPs is phagocytosis by alveolar macrophages [84]. Subsequently, the liver, kidney, and intestine may play critical roles as UFPs are transferred to extra-pulmonary organs, as shown in Fig. 1b. Overall, the primary clearance pathway for UFPs in the body is through the kidney, with the majority of particles ultimately excreted in urine [85].

4.2.1. Clearance by liver

The liver is a critical hub for numerous physiological processes, and metabolism is one of its main functions [86]. It is generally accepted that hepatobiliary clearance is processed through the hepatic sinusoids, space of discharge, hepatocytes, and bile ducts, eventually to the intestines, and excreted in the feces, as shown in Fig. 1b [87]. It has been found that UFPs have relatively high deposition in the liver but are removed in small amounts and in long cycles [88,89]. As the resident macrophage population in the liver accounts for 80%–90% of all macrophages within the body, Kupffer cells play an important role in removing foreign substances [90]. Studies have demonstrated that after removing the majority of Kupffer cells in the mouse liver, Au NPs eliminated through the liver are increased by more than ten times, suggesting that non-parenchymal cells such as Kupffer cells can influence the clearance of UFPs [87]. In addition, Tsoi et al. found that, except for Kupffer cells, endothelial cells and B cells in the liver also play a significant role in the clearance of particles [91].

4.2.2. Clearance by kidney

There is evidence that Au NPs smaller than 5 nm can be detected in both human and animal urine 24 h or 3 months after exposure [92], suggesting that the kidney is one of the major clearance pathways for UFPs. To further investigate the association between particle size and kidney elimination, Choi et al. used intravenously administered quantum dots (QDs) as a model and reported that the amount of QDs detected in urine decreased as particle size increased [93]. Han et al. also reported a size-dependent clearance pattern of Au NPs in the kidneys [94]. In addition to particle size, clearance of UFPs via the kidney is also influenced by time. A study on the biokinetics of inhaled Au NPs (20 nm) found that the proportion of Au NPs excreted via urine was low during the first five days and increased rapidly from day 7 to day 28 [65], and these results were also verified using TiO2 NPs [95].

4.2.3. Clearance by intestine

In addition to removal by the liver and then excretion via the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) in feces, UFPs in circulation can also be transferred to the intestine directly by penetrating the intestinal barrier through several mechanisms, such as diffusion in the intestinal mucus layer, cellular transport, and endocytosis by intestinal epithelial cells [96]. During this process, UFPs must pass through the mucus layer and the epithelium. Active uptake by endocytosis, including receptor-mediated permeation, adsorption endocytosis, and liquid-phase endocytosis, is the most common way for UFPs to enter intestinal epithelial cells, during which microfold cells (M cells) play a critical role [97]. A study from Germany reported that approximately 30% of Au NPs deposited in the airway epithelium could be cleared by the mucus-cilia system and finally excreted via the GIT, whereas approximately 80% of Au NPs deposited in the alveoli would relocate from the epithelium into the interstitium within 24 h [65]. During long-term interstitial retention, Au NPs could remigrate back to the epithelium via the long-term mediated pathway of alveolar macrophages (LT-MC) and finally be excreted through the GIT [65].

5. Toxicological action modes of ambient ultrafine particles

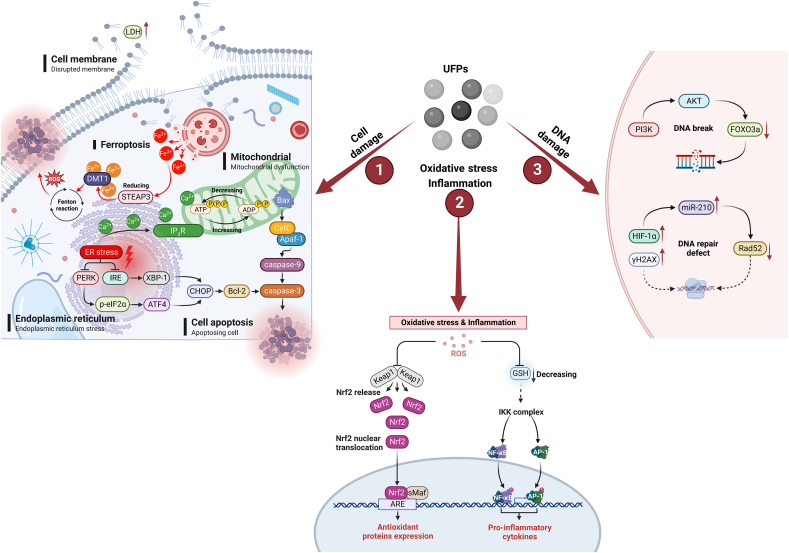

5.1. Disruption of cell structure

Increasing evidence has shown that UFPs may cause structural damage in cells. For instance, experiments using isolated lung fibrocytes (LFs), the most common cells in the lung interstitium with important roles in the physiological functions of the lung [98], have shown that CB NPs can inhibit LFs proliferation, increase lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) content, which is a well-known indicator of cell membrane damage, and induce cell apoptosis (increased from 0.24% to 35.2% within 24 h after particle exposure) [99]. Further studies have demonstrated the size effect of UFPs. For hepatocyte damage and apoptosis due to CB NP exposure, a negative correlation was observed between the particle size and magnitude of cytotoxicity [43]. This suggests that the impact of UFPs on health may depend partially on their size. On the one hand, the increase in the specific surface area of particles as their size decreases contributes to increased binding affinity with protein molecules and more disruption of protein structure [43], which may lead to higher molecular toxicity. On the other hand, smaller particles are thought to easily cross the cell membrane, interact with or penetrate into cellular organelles, finally causing cytotoxicity. Similarly, a dose–response relationship was found between Ag NPs and their toxic effects on cells [100].

In addition, histological analysis showed that zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) could cause mechanical damage to cells by connecting the cell divider, resulting in the distortion of cell membranes, mitochondrial damage, and the outflow of specific organelles [42,101]. Except for particle size, exposure concentration, and duration [102], the extent of cellular structural damage caused by UFPs may also be influenced by particle morphology. While ambient particles are typically irregularly shaped, most studies on UFPs have utilized spherical particles. Therefore, investigation of the morphological effects of UFPs is necessary for future studies.

5.2. Endoplasmic reticulum stress

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a dynamic organelle that controls lipid metabolism, calcium storage, and proteostasis [103]. UFPs were found to induce ER stress, which can subsequently activate double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase (PKR)-like ER kinase (PERK) or inositol-requiring enzyme (IRE) signaling pathways to induce cell apoptosis [104]. In the PERK signaling pathway, after ER stress activates PERK, the α-subunit of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 (eIF2α) becomes phosphorylated, which then leads to the activation of transcription factor-4 (ATF4) and the subsequent transcription of C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) [104]. In the IRE signaling pathway, activated IRE-1 cleaves X-box binding protein 1 (XBP-1) by removing an intron to generate spliced XBP-1 (XBP-1s), which then initiates transcription of CHOP [104]. Finally, CHOP may further regulate the activity of anti-apoptotic proteins such as bcl-2 and/or apoptosis-associated proteases, including caspase-3.

In addition, UFP-induced ER stress may lengthen ER-mitochondrial contact sites, increase Ca2+ uptake by mitochondria by enhancing the function of the inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate receptor (IP3R), and ultimately disrupt mitochondrial homeostasis [105]. This can result in upregulation of the BCL2-associated X (Bax, an apoptosis regulator) in mitochondria, leading to the release of cytochrome c (CytC) into the cytoplasm [106,107]. The binding of CytC with apoptotic protease activating factor-1 (Apaf-1) can activate downstream caspase-related signaling pathways, ultimately resulting in mitochondrial apoptosis [106].

Studies have shown that classically programmed cell death processes such as apoptosis, pyroptosis, and autophagy are closely linked to ER stress caused by UFPs [108,109]. For example, pyroptosis, a newly confirmed type of programmed cell death, has been found to be mediated by particles and cause adverse health effects in some studies [[110], [111], [112]]. However, current studies have focused on fine particles or a mixture of particles of different sizes, making it difficult to tell the causal relationship between UFPs exposure and pyroptosis, which requires further investigation in the future.

5.3. Stimulation of inflammation response and oxidative stress

Inflammatory responses and oxidative stress are highly implicated in the pathogenesis of UFP-induced adverse health effects. Studies have found that exposure to UFPs can cause an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels, which in turn destabilizes the binding of nuclear factor-E2-related factor-2 (Nrf2) and Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1) [[113], [114], [115]]. Once Nrf2 is released into the cytoplasm and binds to the AU-rich element (ARE), downstream genes are activated, leading to the expression of antioxidant proteins [116,117]. This is one of the classical mechanisms by which UFPs induce oxidative stress and inflammatory responses. Another pro-inflammatory pathway is triggered by a change in the level of an important antioxidant, glutathione (GSH). In this pathway, exposure to UFPs reduces the expression of GSH, leading to the activation and phosphorylation of the IκB kinase (IKK) complex, which activates downstream NF-κB and activator protein 1 (AP-1) pathways, ultimately stimulating the inflammatory response [[118], [119], [120]].

Previous studies have also demonstrated that exposure to CB NPs can increase the level of malondialdehyde (MDA) and the relative activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD) while decreasing the activity of catalase (CAT), an important antioxidant enzyme in the body [43,99]. These findings provide further evidence that exposure to UFPs can lead to oxidative damage and redox imbalance. In addition, CB NPs are found to be recognized by the integrin alpha M (Itgam) receptor on the surface of microglia, activating nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase and causing oxidative damage to dopamine neurons [121]. Similarly, QDs have been shown to activate microglia in the olfactory bulb, inducing inflammatory reactions in the central nervous system, and the underlying molecular mechanisms still require further investigation [74].

5.4. DNA damage

DNA is critical for storing genetic information, and both exogenous and endogenous factors can lead to DNA damage. Several studies have been conducted to elucidate DNA damage induced by UFPs [[122], [123], [124]]. For instance, a significant increase in the level of phosphorylated H2AX (γH2AX), a histone necessary for DNA damage repair, was observed in cells after exposure to UFPs, suggesting that UFPs successfully induced DNA damage [117,125]. In terms of potential biological mechanisms, studies showed that the oxidative stress caused by UFPs exposure can activate the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-protein Kinase B (AKT) signaling pathway, which inhibits the activity of the forkhead box O3 (FOXO3a) protein, finally leading to DNA damage [126,127].

It is worth noting that UFPs exposure may not only induce DNA damage but also affect the repair of DNA defects. Studies have found that nickel nanoparticles (Ni NPs) can induce the accumulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) and upregulate microRNA 210 (miR-210) upon contacting cells, thereby inhibiting the expression of the RAD52 homolog (Rad52), which is responsible for repairing DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) [128]. Numerous studies have indicated that DNA damage is closely related to oxidative stress and inflammatory responses [127,129]. Thus, the ROS and inflammatory cytokines induced by UFPs exposure may play a crucial role in activating DNA damage (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The potential toxicity mechanisms of ambient UFPs. UFPs may induce toxicity mainly through pathways including the introduction of cell damage (such as cell membrane disruption marked by LDH extravasation, endoplasmic reticulum stress, cell apoptosis, IP3R-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction and lysosomal damage, STEAP3/DMT1-mediated ferroptosis), oxidative stress and inflammatory response (such as Nrf2-mediated oxidative stress, NF-κB and AP-1-mediated inflammatory responses), and DNA damage (such as PI3K/AKT/FOXO3a-mediated double-strand breakage and HIF-1α/miR-210/Rad52-mediated DNA repair defect).

5.5. Ferroptosis

Apart from the above toxicological mechanisms, studies have found that UFPs may also impact ferroptosis, an iron-dependent programmed cell death characterized by lipid peroxidation proposed in 2012 [130]. For instance, ferrous nanoparticles can release Fe3+ when decomposed by lysosomes in cells, and the six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of prostate 3 (STEAP3) then reduces Fe3+ to Fe2+, which can be transported to the cytoplasm by divalent metal-ion transporter-1 (DMT1) [131]. The accumulation of excess iron in cells can lead to the Fenton reaction, a process that generates ROS and finally results in ferroptosis [131]. Additionally, exposure to ferrous nanoparticles may suppress the expression of heat shock protein family A member 5 (HSPA5), a negative regulator of ferritin deposition, and nuclear receptor coactivator 4 (NCOA4), which is known to be involved in ferritin degradation and ferroptosis [131].

Although most ambient UFPs contain iron ions, it’s yet to be known whether UFPs without iron ions could induce ferroptosis. A study showed that ZnO NPs without iron ions successfully induced ferroptosis by releasing Zn2+ into the cytoplasm after lysosomal degradation, which then activates P53 (a tumor suppressor gene), disrupts iron metabolism, alters mitochondrial function, and redox homeostasis [132]. It’s worth noting that both engineered nanoparticles and ambient UFPs are found to be capable of inducing ferroptosis through mitochondrial-related pathways [133], suggesting that the ability of UFPs to trigger ferroptosis may not be limited to metal ions alone. Despite these results, the complex physical and chemical characteristics of ambient UFPs underscore the need for further investigation, which may greatly contribute to a better understanding of molecular mechanisms in UFP-induced ferroptosis and help identify potential strategies for mitigating their harmful effects.

6. Conclusion and perspective

An increasing number of epidemiological and toxicological studies have indicated that UFPs with small particle sizes and complex compositions and sources may induce more severe adverse health effects than larger particles such as PM10 or PM2.5. To date, several studies have highlighted that UFPs may be distributed in various pulmonary and extra-pulmonary organs, including the brain, liver, kidney, and placenta, by penetrating the ABB, BBB, or PB and eventually being removed through the liver, kidney, or intestine. In addition, recent advances in sequencing and in vivo and in vitro toxicological models have improved our understanding of the toxicological mechanisms of ambient UFPs, including damage to cell structure, the introduction of endoplasmic reticulum stress, DNA damage, cell apoptosis, inflammatory responses, and oxidative stress. Despite recent studies, there are still many unknowns and uncertainties related to UFPs, which include but not limited to: (1) UFPs are found to be capable of penetrating biological barriers, cell membranes or even intracellular organelles, yet the underlying molecular mechanisms or their transportation characteristics is not clear; (2) although it’s challenging to separate UFPs and other air pollutants in real-world studies, it’s of great importance to clarify the specific health effect of UFPs and its interactions (additive, synergistic or enhanced effects) with other classical air pollutants such as O3, VOCs and NOx; (3) considering that many physical and chemical properties including size, morphology, surface charge, reactivity and solubility can influence the toxicity and health effects of UFPs, interdisciplinary studies combining novel detection technologies and well-controlled toxicological models are needed to fully investigate their bio-distribution, clearance pathways and toxic effects in vivo; (4) the development of nanotechnology present new opportunities for studying ambient UFPs, but the differences between engineered nanoparticles and naturally occurred particles should not be ignored, and appropriate ones should be chosen carefully according to the research purposes and application conditions to obtain reliable conclusions. As concerns about UFP pollution grow worldwide, the WHO released an updated Global Air Quality Guideline in which UFPs monitoring is recommended to expand the current air quality assessment strategies in 2021. With contributions from novel technologies and models in toxicology, epidemiology, and environmental science, a comprehensive understanding of the health effects and action modes of UFPs and effective prevention or therapeutic strategies are expected in the near future.

Author contributions

D.Y.H. contributed to writing the original draft, and writing, reviewing & editing of the manuscript. R.J.C. contributed to the conceptualization, and reviewing & editing of the manuscript. H.D.K. contributed to conceptualization, and reviewing & editing of the manuscript. Y.Y.X. contributed to conceptualization, and writing, reviewing & editing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

This work was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2019YFC1804503 to YX) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82003414 to YX).

References

- 1.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2021. WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines: Particulate Matter (PM2.5 and PM10), Ozone, Nitrogen Dioxide, Sulfur Dioxide and Carbon Monoxide. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carvalho H. New WHO global air quality guidelines: more pressure on nations to reduce air pollution levels. Lancet Planet. Health. 2021;5:e760–e761. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00287-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schraufnagel D.E. The health effects of ultrafine particles. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020;52:311–317. doi: 10.1038/s12276-020-0403-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li N., Georas S., Alexis N., Fritz P., Xia T., Williams M.A., et al. A work group report on ultrafine particles (American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology): why ambient ultrafine and engineered nanoparticles should receive special attention for possible adverse health outcomes in human subjects. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016;138:386–396. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang W., Lin Y., Yang H., Ling W., Liu L., Zhang W., et al. Internal exposure and distribution of airborne fine particles in the human body: methodology, current understandings, and research needs. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022;56:6857–6869. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.1c07051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi H.S., Ashitate Y., Lee J.H., Kim S.H., Matsui A., Insin N., et al. Rapid translocation of nanoparticles from the lung airspaces to the body. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:1300–1303. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwon H.S., Ryu M.H., Carlsten C. Ultrafine particles: unique physicochemical properties relevant to health and disease. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020;52:318–328. doi: 10.1038/s12276-020-0405-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu S., Zhang W., Zhang R., Liu P., Wang Q., Shang Y., et al. Comparison of cellular toxicity caused by ambient ultrafine particles and engineered metal oxide nanoparticles. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2015;12:5. doi: 10.1186/s12989-015-0082-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kreyling W.G., Hirn S., Möller W., Schleh C., Wenk A., Celik G., et al. Air-blood barrier translocation of tracheally instilled gold nanoparticles inversely depends on particle size. ACS Nano. 2014;8:222–233. doi: 10.1021/nn403256v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saleh Y., Antherieu S., Dusautoir R., Alleman L.Y., Sotty J., De Sousa C., et al. Exposure to atmospheric ultrafine particles induces severe lung inflammatory response and tissue remodeling in mice. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019;16:1–18. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16071210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meng X., Ma Y., Chen R., Zhou Z., Chen B., Kan H. Size-fractionated particle number concentrations and daily mortality in a Chinese city. Environ. Health Perspect. 2013;121:1174–1178. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1206398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strak M., Janssen N.A.H., Godri K.J., Gosens I., Mudway I.S., Cassee F.R., et al. Respiratory health effects of airborne particulate matter: the role of particle size, composition, and oxidative potential-the RAPTES project. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012;120:1183–1189. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Habre R., Zhou H., Eckel S.P., Enebish T., Fruin S., Bastain T., et al. Short-term effects of airport-associated ultrafine particle exposure on lung function and inflammation in adults with asthma. Environ. Int. 2018;118:48–59. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turner A., Brokamp C., Wolfe C., Reponen T., Ryan P. Personal exposure to average weekly ultrafine particles, lung function, and respiratory symptoms in asthmatic and non-asthmatic adolescents. Environ. Int. 2021;156 doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2021.106740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wright R.J., Hsu H.L., Chiu Y.M., Coull B.A., Simon M.C., Hudda N., et al. Prenatal ambient ultrafine particle exposure and childhood asthma in the Northeastern United States. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021;204:788–796. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202010-3743OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weichenthal S., Bai L., Hatzopoulou M., Van Ryswyk K., Kwong J.C., Jerrett M., et al. Long-term exposure to ambient ultrafine particles and respiratory disease incidence in in Toronto, Canada: a cohort study. Environ. Health. 2017;16:64. doi: 10.1186/s12940-017-0276-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lanzinger S., Schneider A., Breitner S., Stafoggia M., Erzen I., Dostal M., et al. Associations between ultrafine and fine particles and mortality in five central European cities - results from the UFIREG study. Environ. Int. 2016;88:44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen R., Hu B., Liu Y., Xu J., Yang G., Xu D., et al. Beyond PM2.5: the role of ultrafine particles on adverse health effects of air pollution. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1860:2844–2855. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2016.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rychlik K.A., Secrest J.R., Lau C., Pulczinski J., Zamora M.L., Leal J., et al. In utero ultrafine particulate matter exposure causes offspring pulmonary immunosuppression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2019;116:3443–3448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1816103116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wong E.M., Walby W.F., Wilson D.W., Tablin F., Schelegle E.S. Ultrafine particulate matter combined with ozone exacerbates lung injury in mature adult rats with cardiovascular disease. Toxicol. Sci. 2018;163:140–151. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfy018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu X., Sui B., Sun J. Blood-brain barrier dysfunction induced by silica NPs in vitro and in vivo: involvement of oxidative stress and Rho-kinase/JNK signaling pathways. Biomaterials. 2017;121:64–82. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fournier S.B., D'Errico J.N., Adler D.S., Kollontzi S., Goedken M.J., Fabris L., et al. Nanopolystyrene translocation and fetal deposition after acute lung exposure during late-stage pregnancy. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2020;17:55. doi: 10.1186/s12989-020-00385-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller M.R., Newby D.E. Air pollution and cardiovascular disease: car sick. Cardiovasc. Res. 2020;116:279–294. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvz228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Breitner S., Liu L., Cyrys J., Brüske I., Franck U., Schlink U., et al. Sub-micrometer particulate air pollution and cardiovascular mortality in Beijing, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2011;409:5196–5204. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pilz V., Wolf K., Breitner S., Rückerl R., Koenig W., Rathmann W., et al. C-reactive protein (CRP) and long-term air pollution with a focus on ultrafine particles. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health. 2018;221:510–518. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2018.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koenig W., Khuseyinova N., Baumert J., Thorand B., Loewel H., Chambless L., et al. Increased concentrations of C-reactive protein and IL-6 but not IL-18 are independently associated with incident coronary events in middle-aged men and women: results from the MONICA/KORA Augsburg case-cohort study, 1984-2002. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2006;26:2745–2751. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000248096.62495.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olsen Y., Karottki D.G., Jensen D.M., Bekö G., Kjeldsen B.U., Clausen G., et al. Vascular and lung function related to ultrafine and fine particles exposure assessed by personal and indoor monitoring: a cross-sectional study. Environ. Health. 2014;13:112. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-13-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karottki D.G., Bekö G., Clausen G., Madsen A.M., Andersen Z.J., Massling A., et al. Cardiovascular and lung function in relation to outdoor and indoor exposure to fine and ultrafine particulate matter in middle-aged subjects. Environ. Int. 2014;73:372–381. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2014.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurhanewicz N., McIntosh-Kastrinsky R., Tong H., Walsh L., Farraj A.K., Hazari M.S. Ozone co-exposure modifies cardiac responses to fine and ultrafine ambient particulate matter in mice: concordance of electrocardiogram and mechanical responses. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2014;11:54. doi: 10.1186/s12989-014-0054-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.D'Errico J.N., Doherty C., Reyes George J.J., Buckley B., Stapleton P.A. Maternal, placental, and fetal distribution of titanium after repeated titanium dioxide nanoparticle inhalation through pregnancy. Placenta. 2022;121:99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2022.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pasquiou A., Pelluard F., Manangama G., Brochard P., Audignon S., Sentilhes L., et al. Occupational exposure to ultrafine particles and placental histopathological lesions: a retrospective study about 130 cases. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18 doi: 10.3390/ijerph182312719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Behlen J.C., Lau C.H., Pendleton D., Li Y., Hoffmann A.R., Golding M.C., et al. NRF2-dependent placental effects vary by sex and dose following gestational exposure to ultrafine particles. Antioxidants (Basel) 2022;11 doi: 10.3390/antiox11020352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morales-Rubio R.A., Alvarado-Cruz I., Manzano-León N., Andrade-Oliva M.D., Uribe-Ramirez M., Quintanilla-Vega B., et al. In utero exposure to ultrafine particles promotes placental stress-induced programming of renin-angiotensin system-related elements in the offspring results in altered blood pressure in adult mice. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2019;16:7. doi: 10.1186/s12989-019-0289-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Araujo J.A., Barajas B., Kleinman M., Wang X., Bennett B.J., Gong K.W., et al. Ambient particulate pollutants in the ultrafine range promote early atherosclerosis and systemic oxidative stress. Circ. Res. 2008;102:589–596. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.164970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li R., Navab M., Pakbin P., Ning Z., Navab K., Hough G., et al. Ambient ultrafine particles alter lipid metabolism and HDL anti-oxidant capacity in LDLR-null mice. J. Lipid Res. 2013;54:1608–1615. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M035014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gorr M.W., Youtz D.J., Eichenseer C.M., Smith K.E., Nelin T.D., Cormet-Boyaka E., et al. In vitro particulate matter exposure causes direct and lung-mediated indirect effects on cardiomyocyte function. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2015;309:H53–H62. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00162.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li R., Mittelstein D., Kam W., Pakbin P., Du Y., Tintut Y., et al. Atmospheric ultrafine particles promote vascular calcification via the NF-κB signaling pathway. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2013;304:C362–C369. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00322.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pritchett N., Spangler E.C., Gray G.M., Livinski A.A., Sampson J.N., Dawsey S.M., et al. Exposure to outdoor particulate matter air pollution and risk of gastrointestinal cancers in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiologic evidence. Environ. Health Perspect. 2022;130 doi: 10.1289/EHP9620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Deng H., Eckel S.P., Liu L., Lurmann F.W., Cockburn M.G., Gilliland F.D. Particulate matter air pollution and liver cancer survival. Int. J. Cancer. 2017;141:744–749. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guo C., Chan T.C., Teng Y.C., Lin C., Bo Y., Chang L.Y., et al. Long-term exposure to ambient fine particles and gastrointestinal cancer mortality in Taiwan: a cohort study. Environ. Int. 2020;138 doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.So R., Chen J., Mehta A.J., Liu S., Strak M., Wolf K., et al. Long-term exposure to air pollution and liver cancer incidence in six European cohorts. Int. J. Cancer. 2021;149:1887–1897. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang R., Zhang X., Gao S., Liu R. Assessing the in vitro and in vivo toxicity of ultrafine carbon black to mouse liver. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;655:1334–1341. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.11.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li X., Chu S., Song Z., He F., Cui Z., Liu R. Discrepancy of apoptotic events in mouse hepatocytes and catalase performance: size-dependent cellular and molecular toxicity of ultrafine carbon black. J. Hazard Mater. 2022;421 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Modrzynska J., Berthing T., Ravn-Haren G., Jacobsen N.R., Weydahl I.K., Loeschner K., et al. Primary genotoxicity in the liver following pulmonary exposure to carbon black nanoparticles in mice. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2018;15:2. doi: 10.1186/s12989-017-0238-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kumari M., Kumari S.I., Kamal S.S., Grover P. Genotoxicity assessment of cerium oxide nanoparticles in female Wistar rats after acute oral exposure. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2014;775–776:7–19. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shukla R.K., Kumar A., Gurbani D., Pandey A.K., Singh S., Dhawan A. TiO2 nanoparticles induce oxidative DNA damage and apoptosis in human liver cells. Nanotoxicology. 2013;7:48–60. doi: 10.3109/17435390.2011.629747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shukla R.K., Kumar A., Vallabani N.V., Pandey A.K., Dhawan A. Titanium dioxide nanoparticle-induced oxidative stress triggers DNA damage and hepatic injury in mice. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2014;9:1423–1434. doi: 10.2217/nnm.13.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Singh S.P., Kumari M., Kumari S.I., Rahman M.F., Mahboob M., Grover P. Toxicity assessment of manganese oxide micro and nanoparticles in Wistar rats after 28 days of repeated oral exposure. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2013;33:1165–1179. doi: 10.1002/jat.2887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wallin H., Kyjovska Z.O., Poulsen S.S., Jacobsen N.R., Saber A.T., Bengtson S., et al. Surface modification does not influence the genotoxic and inflammatory effects of TiO2 nanoparticles after pulmonary exposure by instillation in mice. Mutagenesis. 2017;32:47–57. doi: 10.1093/mutage/gew046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li R., Navab K., Hough G., Daher N., Zhang M., Mittelstein D., et al. Effect of exposure to atmospheric ultrafine particles on production of free fatty acids and lipid metabolites in the mouse small intestine. Environ. Health Perspect. 2015;123:34–41. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1307036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li R., Yang J., Saffari A., Jacobs J., Baek K.I., Hough G., et al. Ambient ultrafine particle ingestion alters gut microbiota in association with increased atherogenic lipid metabolites. Sci. Rep. 2017;7 doi: 10.1038/srep42906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Behlen J.C., Lau C.H., Li Y., Dhagat P., Stanley J.A., Hoffman A.R., et al. Gestational exposure to ultrafine particles reveals sex- and dose-specific changes in offspring birth outcomes, placental morphology, and gene networks. Toxicol. Sci. 2021;184:204–213. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfab118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maher B.A., Ahmed I.A., Karloukovski V., MacLaren D.A., Foulds P.G., Allsop D., et al. Magnetite pollution nanoparticles in the human brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016;113:10797–10801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605941113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hameed S., Zhao J., Zare R.N. Ambient PM particles reach mouse brain, generate ultrastructural hallmarks of neuroinflammation, and stimulate amyloid deposition, tangles, and plaque formation. Talanta Open. 2020;2 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kreyling W.G. Discovery of unique and ENM- specific pathophysiologic pathways: comparison of the translocation of inhaled iridium nanoparticles from nasal epithelium versus alveolar epithelium towards the brain of rats. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2016;299:41–46. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu A.H., Fruin S., Larson T.V., Tseng C.C., Wu J., Yang J., et al. Association between airport-related ultrafine particles and risk of malignant brain cancer: a multiethnic cohort study. Cancer Res. 2021;81:4360–4369. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-21-1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weichenthal S., Olaniyan T., Christidis T., Lavigne E., Hatzopoulou M., Van Ryswyk K., et al. Within-city spatial variations in ambient ultrafine particle concentrations and incident brain tumors in adults. Epidemiology. 2020;31:177–183. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000001137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Andersen Z.J., Olsen T.S., Andersen K.K., Loft S., Ketzel M., Raaschou-Nielsen O. Association between short-term exposure to ultrafine particles and hospital admissions for stroke in Copenhagen, Denmark. Eur. Heart J. 2010;31:2034–2040. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Park S.J., Lee J., Lee S., Lim S., Noh J., Cho S.Y., et al. Exposure of ultrafine particulate matter causes glutathione redox imbalance in the hippocampus: a neurometabolic susceptibility to Alzheimer's pathology. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;718 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Herr D., Jew K., Wong C., Kennell A., Gelein R., Chalupa D., et al. Effects of concentrated ambient ultrafine particulate matter on hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease in the 3xTgAD mouse model. Neurotoxicology. 2021;84:172–183. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2021.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Genc S., Zadeoglulari Z., Fuss S.H., Genc K. The adverse effects of air pollution on the nervous system. J. Toxicol. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/782462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Milani C., Farina F., Botto L., Massimino L., Lonati E., Donzelli E., et al. Systemic exposure to air pollution induces oxidative stress and inflammation in mouse brain, contributing to neurodegeneration onset. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21 doi: 10.3390/ijms21103699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Levesque S., Surace M.J., McDonald J., Block M.L. Air pollution & the brain: subchronic diesel exhaust exposure causes neuroinflammation and elevates early markers of neurodegenerative disease. J. Neuroinflammation. 2011;8:105. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Klocke C., Allen J.L., Sobolewski M., Mayer-Pröschel M., Blum J.L., Lauterstein D., et al. Neuropathological consequences of gestational exposure to concentrated ambient fine and ultrafine particles in the mouse. Toxicol. Sci. 2017;156:492–508. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfx010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kreyling W.G., Möller W., Holzwarth U., Hirn S., Wenk A., Schleh C., et al. Age-dependent rat lung deposition patterns of inhaled 20 nanometer gold nanoparticles and their quantitative biokinetics in adult rats. ACS Nano. 2018;12:7771–7790. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b01826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li D., Li Y., Li G., Zhang Y., Li J., Chen H. Fluorescent reconstitution on deposition of PM2.5 in lung and extrapulmonary organs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2019;116:2488–2493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1818134116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rattanapinyopituk K., Shimada A., Morita T., Togawa M., Hasegawa T., Seko Y., et al. Ultrastructural changes in the air-blood barrier in mice after intratracheal instillations of Asian sand dust and gold nanoparticles. Exp. Toxicol. Pathol. 2013;65:1043–1051. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Furuyama A., Kanno S., Kobayashi T., Hirano S. Extrapulmonary translocation of intratracheally instilled fine and ultrafine particles via direct and alveolar macrophage-associated routes. Arch. Toxicol. 2009;83:429–437. doi: 10.1007/s00204-008-0371-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Blank F., Stumbles P.A., Seydoux E., Holt P.G., Fink A., Rothen-Rutishauser B., et al. Size-dependent uptake of particles by pulmonary antigen-presenting cell populations and trafficking to regional lymph nodes. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2013;49:67–77. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0387OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Husain M., Wu D., Saber A.T., Decan N., Jacobsen N.R., Williams A., et al. Intratracheally instilled titanium dioxide nanoparticles translocate to heart and liver and activate complement cascade in the heart of C57BL/6 mice. Nanotoxicology. 2015;9:1013–1022. doi: 10.3109/17435390.2014.996192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kreyling W.G., Semmler M., Erbe F., Mayer P., Takenaka S., Schulz H., et al. Translocation of ultrafine insoluble iridium particles from lung epithelium to extrapulmonary organs is size dependent but very low. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A. 2002;65:1513–1530. doi: 10.1080/00984100290071649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mercer R.R., Scabilloni J.F., Hubbs A.F., Wang L., Battelli L.A., McKinney W., et al. Extrapulmonary transport of MWCNT following inhalation exposure. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2013;10:38. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-10-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sadauskas E., Jacobsen N.R., Danscher G., Stoltenberg M., Vogel U., Larsen A., et al. Biodistribution of gold nanoparticles in mouse lung following intratracheal instillation. Chem. Cent. J. 2009;3:16. doi: 10.1186/1752-153X-3-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hopkins L.E., Patchin E.S., Chiu P.L., Brandenberger C., Smiley-Jewell S., Pinkerton K.E. Nose-to-brain transport of aerosolised quantum dots following acute exposure. Nanotoxicology. 2014;8:885–893. doi: 10.3109/17435390.2013.842267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Elder A., Gelein R., Silva V., Feikert T., Opanashuk L., Carter J., et al. Translocation of inhaled ultrafine manganese oxide particles to the central nervous system. Environ. Health Perspect. 2006;114:1172–1178. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Oberdörster G., Sharp Z., Atudorei V., Elder A., Gelein R., Kreyling W., et al. Translocation of inhaled ultrafine particles to the brain. Inhal. Toxicol. 2004;16:437–445. doi: 10.1080/08958370490439597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bejgum B.C., Donovan M.D. Uptake and transport of ultrafine nanoparticles (quantum dots) in the nasal mucosa. Mol. Pharm. 2021;18:429–440. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.0c01074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Oppenheim H.A., Lucero J., Guyot A.C., Herbert L.M., McDonald J.D., Mabondzo A., et al. Exposure to vehicle emissions results in altered blood brain barrier permeability and expression of matrix metalloproteinases and tight junction proteins in mice. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2013;10:62. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-10-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bové H., Bongaerts E., Slenders E., Bijnens E.M., Saenen N.D., Gyselaers W., et al. Ambient black carbon particles reach the fetal side of human placenta. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:3866. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11654-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Liu N.M., Miyashita L., Maher B.A., McPhail G., Jones C.J.P., Barratt B., et al. Evidence for the presence of air pollution nanoparticles in placental tissue cells. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;751 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Grafmueller S., Manser P., Diener L., Diener P.A., Maeder-Althaus X., Maurizi L., et al. Bidirectional transfer study of polystyrene nanoparticles across the placental barrier in an ex vivo human placental perfusion model. Environ. Health Perspect. 2015;123:1280–1286. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1409271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Aengenheister L., Dietrich D., Sadeghpour A., Manser P., Diener L., Wichser A., et al. Gold nanoparticle distribution in advanced in vitro and ex vivo human placental barrier models. J. Nanobiotechnology. 2018;16:79. doi: 10.1186/s12951-018-0406-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Austin C.A., Hinkley G.K., Mishra A.R., Zhang Q., Umbreit T.H., Betz M.W., et al. Distribution and accumulation of 10 nm silver nanoparticles in maternal tissues and visceral yolk sac of pregnant mice, and a potential effect on embryo growth. Nanotoxicology. 2016;10:654–661. doi: 10.3109/17435390.2015.1107143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Oberdörster G., Oberdörster E., Oberdörster J. Nanotoxicology: an emerging discipline evolving from studies of ultrafine particles. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005;113:823–839. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Qi Y., Wei S., Xin T., Huang C., Pu Y., Ma J., et al. Passage of exogeneous fine particles from the lung into the brain in humans and animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2022;119 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2117083119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Trefts E., Gannon M., Wasserman D.H. The liver. Curr. Biol. 2017;27:R1147–R1151. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]