Abstract

The wide application of nanomaterials and plastic products generates a substantial number of nanoparticulate pollutants in the environment. Nanoparticulate pollutants are quite different from their bulk counterparts because of their unique physicochemical properties, which may pose a threat to environmental organisms and human beings. To accurately predict the environmental risks of nanoparticulate pollutants, great efforts have been devoted to developing reliable methods to define their occurrence and track their fate and transformation in the environment. Herein, we summarized representative studies on the preconcentration, separation, formation, and transformation of nanoparticulate pollutants in environmental samples. Finally, some perspectives on future research directions are proposed.

Keywords: Nanomaterials, Nanoplastics, Preconcentration, Separation, Analysis, Formation

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Nanoparticulate pollutants pose a threat to environmental organisms and humans.

-

•

Reliable approaches to determine the occurrence and characterize the properties of nanoparticulate pollutants in environments are imperative.

-

•

Transformations of nanoparticulate pollutants affect their final fate and biosafety.

-

•

We call for more sensitive techniques to track nanoparticulate pollutants in the environment.

1. Introduction

Nanoparticulate pollutants commonly refer to contaminants with a size falling in the nanometer range. Nanomaterials (NMs, 1–100 nm) and small-sized plastic debris (<5 mm) have been considered emerging contaminants in recent years [1]. Their potential risks have raised general public concerns, and research on these topics is also increasing exponentially. In this review, nanoparticulate pollutants mainly refer to NMs and nanoplastics (NPLs, 1–1000 nm). Although the scientific community has not yet reached a consensus on the clear definition of NPLs [[2], [3], [4], [5]], here we set the upper size limit to 1000 nm based on a recent article reported by Hartmann et al. [6].

Rapid advances in nanotechnology over the past two decades have led to a boom in NMs. The application of NMs covers various fields, such as agriculture, medicine, food, and textile [7]. An optimistic estimation suggests that the global NMs market can exceed 55.0 billion US dollars by 2022 [8]. The most widely used NMs include nano-TiO2, nano-SiO2, nano-Ag, nano-ZnO, and other carbonaceous NMs [9,10]. NMs can be inevitably released into the environment via the production, transportation, abrasion, and discard of NM-containing products.

Plastics materials are a large family of synthetic polymers, including polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polystyrene (PS), and polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) that are frequently used in the daily life and have brought great benefits to the society. The global production of plastics reached 390.7 million tonnes in 2021. However, about 79% of the produced plastics end up in landfills, rivers, oceans, and other natural systems [11]. The breakdown of large plastic debris, either by ultraviolet (UV) irradiation and mechanical wear or by biological corrosion, can result in the generation of small plastic items, even the formation of nano-scale particles, also called secondary NPLs [5]. On the other hand, some micro- and nano-beads are incorporated in personal care products, such as shampoos, facial cleansers, and toothpaste. The production and use of these products can result in the direct release of NPLs to the environment as primary NPLs [12].

The occurrence of nanoparticulate pollutants in the complex environmental matrix has been extensively reported. Ti-, Ce-, Ag-, and Zn-bearing nanoparticles (NPs) were widely detected in global surface water and precipitation samples [[13], [14], [15], [16]]. Accumulation of Ti-, Cu-, Zn-, and Ag- based NPs in marine bivalve mollusks was observed [17]. The existence of NPLs in river water [18], seawater [19], sand [20], soils [21], and even in snow [22] were also reported. Being in the nano-scale range, nanoparticulate pollutants typically possess a large specific surface area and high surface energy, making them rather active in the environment. The unique physicochemical properties of nanoparticulate pollutants make them quite different from their bulk counterparts in transformation, migration, and bioavailability [23]. Thus, the potential hazards of nanoparticulate pollutants have aroused public concerns [[24], [25], [26]].

To accurately predict the environmental risks of nanoparticulate pollutants, reliable approaches to determine the occurrence and characterize the properties of nanoparticulate contaminants in the environment are imperative. Because of the low concentrations, small sizes, and diverse chemical compositions of nanoparticulate contaminants, as well as the complexity of the environmental matrix, the analysis of nanoparticulate pollutants in real samples is still a great challenge. Meanwhile, due to the susceptibility of nanoparticulate pollutants to environmental conditions, nanoparticulate pollutants can undergo different transformations in the natural system, such as aggregation, oxidation, dissolution, sulfidation, and secondary formation, which may significantly affect the final fate and biosafety [9,[27], [28], [29]]. Ongoing efforts have been devoted to determining and tracking nanoparticulate pollutants in the environment.

In this review, we begin with a summarization of some representative articles on the extraction, separation, and analysis of nanoparticulate pollutants in the environment. The applicability of different methods is also scrutinized, and their advantages and limitations are discussed. As nanoparticulate pollutants are widely detected in the environment, we further discuss their possible formation, especially the natural generation of some typical NMs, to trace the sources of nanoparticulate pollutants. Due to their small sizes and relatively high surface energy, nanoparticulate pollutants are highly dynamic in the environment. Once they enter the natural system, they can undergo various physical and chemical transformations. Therefore, we finally outline the possible transformations of nanoparticulate pollutants, both in the aquatic system and in organisms, to bring some insights into their fate in the environment. Some perspectives on future research directions are also proposed.

2. Analytical methods

2.1. Extraction and preconcentration

2.1.1. Membrane extraction

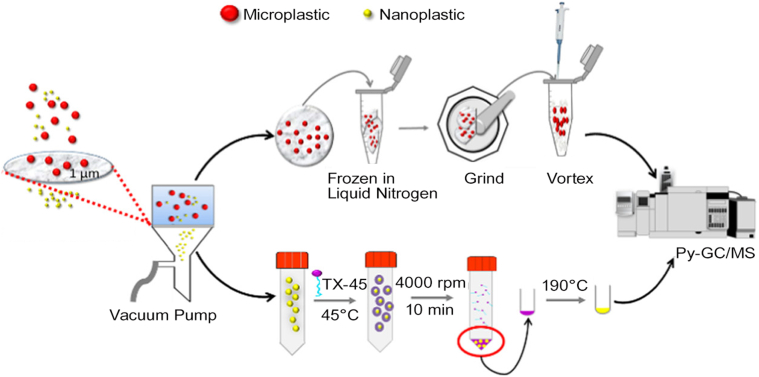

Due to the low cost, easy handling, and high efficiency, membrane separation is popular in collecting and concentrating particles [4,5]. The separation is mainly based on the size exclusion effect that particles with sizes larger than the pore size can be trapped on the filtration membrane, while smaller particles remain in the filtrate. Both NMs and NPLs can be concentrated by filtration with proper pore sizes. However, membrane extraction may be hampered by the undesirable capture of non-target particles, as previous studies reported that several kinds of filtration membranes were prone to adsorb NPs [30,31]. After comparing the adsorption performance of different membranes, Li et al. [32] found that the glass membrane showed negligible adsorption of NPLs. Therefore, NPLs could be easily separated from microplastics using glass membranes with 1 μm pore sizes for further quantification (Fig. 1). Using sequential filtration with different pore-sized membranes (20–25, 2.5, 0.45, and 0.1 μm), NPLs in commercial facial scrubs can be isolated and enriched [33].

Fig. 1.

Sequential separation and concentration of microplastics and NPLs by membrane filtration and CPE, followed by Py-GC/MS determination. Reprinted with permission from ref. [32]. Copyright (2021) American Chemical Society. NPLs, nanoplastics; CPE, cloud point extraction; Py-GC/MS, pyrolysis gas chromatography–mass spectrometry.

Theoretically, nanoparticulate pollutants can be readily concentrated by membrane filtration with proper pore sizes. However, when the particle size decreases, the increased filtration resistance and the clog of pore size by large particles resist its wide application [5,32]. Organic membranes, such as polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) and nylon, showed high affinity to NPs and NPLs, which could act as the adsorbents to capture the targets even though the pore size was much larger than the diameter of particles [[30], [31], [32]]. By using the PVDF membrane (0.45 μm) as the filter, Zhou et al. [30] reported a disk-based solid phase extraction for the concentration of Ag NPs in water. The extraction system consisted of a two-channel syringe pump and a syringe filter holder, which allowed the filtration of two samples simultaneously. Meanwhile, as the large pore size of membranes significantly reduced the filtration resistance, the treatment of large-volume environmental waters (1 L) is available. Ag NPs trapped on the membrane could be eluted by 1 mL of 2% (m/v) FL-70 (a kind of mixed surfactant) with an enrichment factor of 1000. As Ag+ could not be captured by the membrane, Ag NPs and Ag+ could be easily separated as well. Additionally, the PVDF micropore membrane could adsorb other metal and metal oxide NMs, such as Au, NiO, ZnO, Fe2O3, and ZrO2, without disturbing their pristine size and shape [31]. Hence, it is a promising candidate for the analysis of nanoparticulate pollutants in environmental waters.

2.1.2. Cloud point extraction

Based on the cloud points and solubilization ability of nonionic surfactants, cloud point extraction (CPE) was first proposed by Watanabe et al. in 1978 [34,35]. Specifically, CPE includes three steps. First, sufficient nonionic surfactants (concentrations higher than the critical micelle concentration) are added to the sample solution to solubilize the analytes. Then, the cloud point is triggered by changing the solution conditions, such as the temperature, pH, and ion strength. Finally, the phase separation is facilitated by centrifugation or prolonged standing. After that, the targets can be extracted and concentrated into the surfactant-rich phase [36]. Due to the high extraction efficiency and low costs, CPE was frequently used to extract metal ions, biopolymers, and other organic contaminants [37,38].

Further studies revealed that nonionic surfactants could also adsorb on the surface of NMs to form NM-micelles, which makes the extraction of NMs possible. Liu et al. showed that the CPE method was capable of thermoreversible separating and concentrating several NMs, including Ag NPs, fullerene, titanium dioxide, Au NPs, and single-walled carbon nanotubes by using a common nonionic surfactant Triton X-114 [39]. Several parameters, including salinity, pH, surfactant concentration, temperature, and incubation time, could affect the extraction efficiency [40]. Typically, Coulomb repulsion between neighboring NPs can keep NPs stable in the solution. To facilitate the extraction, salts are added to the extraction system to reduce the electrostatic repulsion to promote phase separation. The concentration of salts should be optimized to avoid the undesirable aggregation of NMs [39]. Meanwhile, the surface charges are dependent on the solution’s pH. The highest extraction efficiency is usually obtained at the zero-point charge’s pH. When zeta potential is close to zero, it is beneficial for the gathering of NMs [41]. Sufficient surfactant concentrations are required to ensure the complete extraction of NMs. On the other hand, excessive amounts of surfactant may increase the volume of the surfactant-rich phase and thus reduce the enrichment factor. Notably, the size and morphology could be preserved during the CPE extraction [40], which allows to track the original state of NMs.

For some metal and metal oxide NMs, the coexisting metal ions may disturb the quantification of NMs. However, the separation and selective determination of NPs and dissolved ions is challenging. Some chelating agents, such as Na2S2O3 and ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA), could associate with metal ions to form hydrophilic complexes, which are preserved in the upper aqueous phase in CPE, whereas NMs could be transferred to the surfactant-rich phase [42,43]. Therefore, NMs and the corresponding metal ions can be isolated. This method has been successfully applied to determine Ag NPs and Ag+ in real samples, including commercial products, HepG2 cells, environmental waters, and wastewaters [[42], [43], [44], [45], [46]]. Recently, a dual-CPE method was developed for the selective determination of Se NPs, inorganic Se(IV), and Se(VI) in water. Triton X-45 (TX-45) could adsorb on the surface of Se NPs to form Se NP-TX-45 micelle, which assisted the extraction of Se NPs into the TX-45-rich phase, whereas inorganic Se(VI) and Se(IV) were kept in the aqueous phase. In the second CPE, diethyldithiocarbamate was introduced into the aqueous phase to specifically interact with Se(IV) to form hydrophobic complexes, which could be trapped in the TX-45-rich phase to separate Se(IV) from Se(VI). Thus, different Se species could be readily isolated in water [47].

The CPE method was also proposed to extract NPLs in environmental waters [48]. Under the optimized conditions, NPLs could be transferred into the TX-45 phase with an enrichment factor of about 500. After thermal treatment at 190 °C for 3 h, the coexisting TX-45 in the extract was decomposed. Therefore, NPLs could be further analyzed by pyrolysis gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (Py-GC/MS) without the disturbance of surfactants (Fig. 1). Low detection limits of 11.5 and 2.5 fM were obtained for PS and PMMA NPLs, respectively. In the real water sample determination, 76.5%–96.6% of NPLs could be recovered at spiking levels of 0.4–88.6 fM, showing the capability to detect NPLs in aquatic systems.

2.1.3. Magnetic solid-phase extraction

Magnetic solid-phase extraction (MSPE) is an improved solid phase extraction technique that employs magnetic materials (such as Fe, Fe2O3, and Fe3O4 particles) as adsorbents. These magnetic particles have large surface areas and are easily modified, enabling the capture of various nanoparticulate pollutants in a short time. Meanwhile, due to their superparamagnetic properties, the adsorbents, along with targets, can be magnetized using a magnetic field, and rapidly separated from the matrix [49,50]. MSPE has been successfully used to enrich and selectively separate Au NPs and Ag NPs from their corresponding metal ions in environmental waters. The extraction efficiency is affected by various factors, including surface modification compositions, sorbent dosage, temperature, pH, and equilibrium time [49,51].

Aged magnetic ferric tetroxide (Fe3O4) particles synthesized by the hydrothermal method were reported to selectively extract silver-containing NPs, including zero-valent silver, silver chloride, and silver sulfide, in the presence of Ag ions [52]. After adsorption, different Ag species could be eluted sequentially. Ag NPs and AgCl NPs could be eluted as Ag(I) complexes by 2% (v/v) acetic acid in the presence of aged Fe3O4 particles. Then Ag2S NPs remaining on the adsorbents could be further oxidized to Ag(I) by 10 mM thiourea in 2% (v/v) acetic acid. Therefore, different Ag species could be determined, respectively. This method offered a low detection limit of 0.068 μg/L for Ag2S NPs under the optimized conditions, which was an effective method to detect Ag2S NPs in environmental waters.

Recently, the MSPE method was also used to extract NPLs from environmental waters [18,53]. Li et al. [18] reported the extraction of NPLs by using Fe3O4 particles (300 nm) as the adsorbents. As most NPLs in the environment are negatively charged and hydrophobic, all common NPLs could be readily adsorbed on Fe3O4 particles by electrostatic interaction and hydrophobic forces. Moreover, adding Ca2+ into the extraction system induced the aggregation of NPLs to form Fe3O4-NP agglomerates, which could effectively reduce the adsorption of NPLs on vessel walls. The Fe3O4-NP agglomerates could be effectively collected by a magnetic field because of the large size of magnetic adsorbents. Besides, the Fe3O4-NP aggregates could also be recovered by a glass membrane with large pores to reduce the filtration resistance, which facilitated further quantification by Py-GC/MS [18].

2.2. Size separation and characterization

Because the environmental and biological effects of NPs and NPLs strongly depend on the particle size, various methods have been developed to separate them based on the sizes for further characterization and quantification.

2.2.1. Size exclusion chromatography

To avoid particle alteration during the pretreatment process, some online methods have been developed to simultaneously separate and quantify nanoparticulate pollutants. Among them, the size exclusion chromatography (SEC) method exhibits great potential, especially in the separation of metal-based NPs and their corresponding ions. Currently, the SEC method is able to separate NPs with sizes below 1 nm from ions [54,55], which is almost an impossible task for other online methods. In addition, SEC combined with inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (SEC-ICP-MS) allows the identification and quantification of different species. Theoretically, different-sized NPLs can also be isolated by SEC based on the size exclusion mechanism, although no related studies were reported.

The SEC technique also suffered from a critical defect, i.e., the adsorption of particles and ions onto packing materials of the SEC column, which may affect their accurate quantification. To overcome the obstacle, Zhou et al. [56] introduced the complexing agent Na2S2O3 into the mobile phase to separate Ag NPs and Ag ions. Na2S2O3 could complex with Ag ions to prevent their adsorption on the column, whereas the surfactant FL-70 in the mobile phase could protect Ag NPs from dissolution. Based on this strategy, the quantification of dissoluble Ag(I) and Ag NPs (1–100 nm) in antibacterial products and environmental waters was realized. This approach was extended to the separation and quantification of other types of NPs by selecting different complexing agents and surfactants. Metal oxide NPs were successfully separated from their corresponding ions in environmental waters by using an acetate buffer (pH 7.0, 10 mM) containing sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS, 10 mM) as the mobile phase [57]. Using the mixture of SDS (0.2 wt%) and EDTA (0.1 mM) as the mobile phase, an SEC-ICP-MS-based quantification method was established to investigate the risk of Cd2+ leaching from Cd-containing quantum dots in simulated body fluids [58].

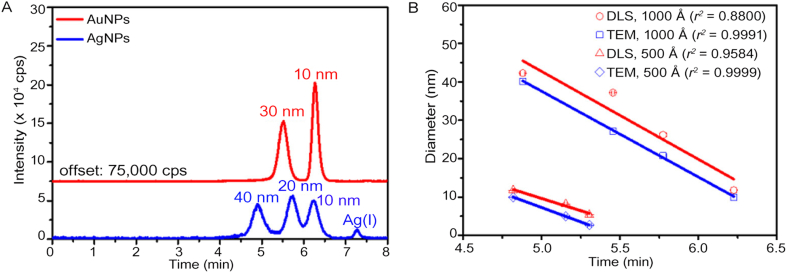

After optimizing separation conditions, 10 and 30 nm Au NPs, as well as 10, 20, and 40 nm Ag NPs, and Ag+ could be separated by SEC in a single measurement. More importantly, the SEC retention time of NPs shows an excellent linear relationship with their transmission electron microscopy (TEM) diameters, suggesting that the SEC method could accurately characterize the size distribution of NPs. The size resolution of the method is down to 0.27 nm (Fig. 2) [59]. Due to high operating costs and tedious sample preparation, the TEM instrument is sometimes inaccessible. In contrast, the SEC method is much more economical, showing an overwhelming advantage in the characterization of NP size distributions, especially in biological and environmental matrices. By coupling with ICP-MS, this approach could be applied to identify composite NMs and quantify NMs at concentration levels of sub μg/L, showing great potential in real-time monitoring of the transformation of NPs in the environment. On contrast, the TEM method requires a high concentration of NPs in samples.

Fig. 2.

Size characterization of NPs by using SEC-ICP-MS. (A) Chromatograms of a mixture of Au NPs (10 and 30 nm) and Ag NPs (10, 20, and 40 nm) recorded by SEC-ICP-MS. (B) Linear fitting of TEM and DLS particle diameter with the SEC-ICP-MS retention time of the three Ag NPs (10, 20, and 40 nm) and 30 nm Au NPs separated with a 1000 Å column, as well as 2.7, 5.0, and 10 nm Ag NPs separated with a 500 Å column. Reprinted with permission from ref. [59]. Copyright (2017) American Chemical Society. NPs, nanoparticles; SEC-ICP-MS, size exclusion chromatography combined with inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry; DLS, dynamic light scattering; TEM, transmission electron microscopy.

When NPs enter organisms, a large amount of biomolecule could adsorb on their surface to form bio-corona, which would greatly influence the final fate of NPs. Traditional characterization methods for bio-corona, e.g., TEM, could not provide quantitative information on bio-corona thickness. The sample preparation is tedious and time-consuming. The SEC technique is promising to characterize NPs in biota. After digesting the biological tissues by tetramethylammonium hydroxide, Dong et al. [60] successfully separated and characterized biocorona-coated Ag NPs and Ag(I) species in rat liver by SEC-ICP-MS. The biocorona thickness of Ag NPs was found to be core size independent, and the effective diameter was linearly related to the core diameter of Ag NPs in extracted tissues. This method could also quantitatively distinguish Ag NPs and Ag(I) species in Escherichia Coli., HepG2, and A549 cells to trace the transformation of NPs in organisms [61,62].

2.2.2. Field-flow fractionation

Field-flow fractionation (FFF) is a flow-based separation technique first developed by Giddings et al. in 1966 [63]. The separation of targets (e.g., macromolecules, colloids, and particles) is accomplished by the interaction of an external field force perpendicularly applied to the main flow direction and the diffusion force of the sample itself. FFF can be categorized into different types based on the applied external field forces, including cross flow/radial flow, centrifugal force, thermal gradient, electrical force, and so on [64]. Among these sub-techniques, flow FFF (F4) is the universal one to separate and characterize nanoparticulate pollutants due to its excellent separation ability in the entire particle size range (1–100 nm), the possibility of online clean-up of complex matrices owing to a semipermeable membrane, and easy installation and operation [65,66]. In a typical F4 run, the carrier liquid delivers the target analytes with different sizes into an ultra-thin separation channel, in which the analytes are pushed toward one side of the separation channel (i.e., accumulation wall) by the external field and simultaneously pushed away from the accumulation wall due to the diffusion force. The particle distribution in the separation channel is closely dependent on their sizes. The main flow is laminar with a parabolic flow, which indicates that the target near the channel center will elute faster than that located near the accumulation wall, and hence separation is achieved. The separated target will elute in sequence into the following detectors for detection and characterization. For instance, asymmetrical F4 (AF4) has been coupled with various detectors, such as UV-visible spectroscopy (UV-vis), multiangle light scattering (MALS), and ICP-MS, to obtain comprehensive information, including size, concentration, and composition of NMs [[67], [68], [69]].

Conventional F4 techniques, including symmetrical F4 (SF4) and AF4, use a rectangular separation channel [70]. The top and bottom walls of the separation channel in SF4 are both permeable, while only the bottom wall of the channel in AF4 is permeable. The AF4 has gradually replaced SF4 due to its lower cost and better separation performance. F4 techniques are reported to be ideal methods to monitor nanoparticulate pollutants in various environmental systems. To evaluate the risk of ZnO NPs in aquatic environments, Amde et al. coupled AF4 with UV-vis for characterization, separation, and quantification of ZnO NPs in environmental waters [71]. Under the optimized separation conditions, a limit of detection of sub mg/L was achieved for two different-sized ZnO NPs (i.e., <35 nm and <100 nm NPs) after ultracentrifugation. Engineered and natural NPs always coexist in the environment, although their physicochemical properties, abundance, and risk are different. To distinguish natural and engineered NPs, AF4 coupled with ICP-MS (AF4-ICP-MS) was used to analyze and characterize TiO2 and CeO2 based on the elemental ratios of Ti or Ce with rare earth elements [72]. NPLs are emerging nanopollutants that have drawn increasing attention due to the wide application of plastic products. Gigault et al. demonstrated the feasibility of AF4 methods to separate PS NPLs with sizes ranging from 80 to 900 nm using five different flow conditions [73]. The report indicated that submicron particles (e.g., 200–800 nm) could be separated from NPs using the AF4 method with programmed cross-flow rates without changing channel components and compositions of the carrier liquid. However, it is difficult to predict their size based on the retention time, as NPLs in the environment are irregular in shape, including fibers, disks, and plates, rather than spherical. This problem can be partly solved by coupling AF4 with other detectors like MALS. Notably, more specific detectors are needed to identify and quantify fractionated NPLs, either online or offline, considering that NPLs in the environment are usually made from different polymers. Recently, our group advised the total organic carbon (TOC) as an index for plastic pollution in environmental waters, demonstrating the possibility of TOC analyzers as the AF4 detectors for quantifying NPLs [74].

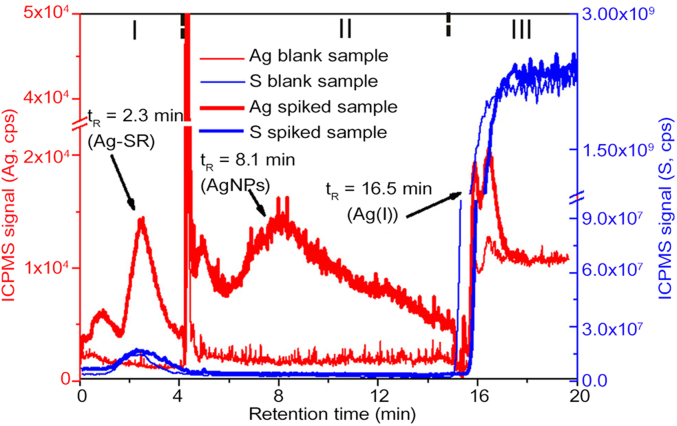

In contrast to conventional F4, hollow-fiber flow FFF (HF5) utilizes a disposable hollow fiber as the separation channel. In addition to the comparable separation ability with AF4, the radial flow of HF5 is usually much lower than the cross-flow of AF4, making HF5 easier to couple with highly sensitive detectors such as ICP-MS [69]. Accordingly, Tan et al. devised HF5-ICP-MS online coupling systems to separate and characterize Ag NPs with sizes ranging from 1.4 to 60 nm for the first time [75]. Moreover, a minicolumn packed with Amberlite IR120 was used to discern free Ag(I) or weak and strong Ag(I) complexes, facilitating full spectrum speciation analysis of Ag NPs and ionic silver in two successive runs. The HF5-ICP-MS system was also successfully used to track the aggregation of Ag NPs at environmentally relevant concentrations and the inter-transformation of Ag(I) and Ag NPs in domestic wastewater (Fig. 3) [76]. These findings demonstrated the power of online HF5-ICP-MS in the characterization of nanoparticulate pollutants in complex media and the necessity of studying the environmental behaviors of nanopollutants at low concentrations. Recently, Tan et al. developed an online hyphenated system using a photoinduced chemical vapor generation reactor and a point discharge-optical emission spectrometry to quantify graphene oxide at sub mg/L [77]. It indicates the great potential of the hyphenated system as the detector of HF5 in studying the environmental transformation and risk of graphene oxide discharged into the environment.

Fig. 3.

Transformation of Ag NPs and Ag(I) (both were spiked at 10 ng/mL) in an influent of a waste water treatment plant. Reprinted with permission from ref. [76]. Copyright (2017) American Chemical Society. NPs, nanoparticles; ICPMS, inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry.

2.3. Identification and quantification

2.3.1. Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy

Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) has been a powerful identification technique since its discovery in the 1970s [78]. To date, SERS applications have been extended to medicine [79], food safety [80], environmental monitoring [81], and other fields. Generally, noble metal nanostructures such as nanospheres, nanoflowers, and nanowires were used as SERS substrates to enhance electric fields generated by conducting electrons on their surface, improve Raman scattering of analytes, and eliminate background interferences [82,83]. Among the reported metal nanostructures, Ag NPs are one of the most widely used particles owing to a wide plasmonic spectral window and great SERS enhancement ability. Guo et al. used Rhodamine 6G adsorbed on Ag NPs as the probe to monitor the enrichment of Ag NPs in the surface microlayer (SML) by depth scanning mode of SERS [84]. Results showed that the Raman intensity at 0–250 μm on the water surface was significantly higher than that in the bulk phase and using R6G only. The signal also increased with time, demonstrating that SERS is helpful in tracking the migration of Ag NPs in aqueous environments. Recently, the same group proposed a feasible SERS method to identify PS NPLs in water [85]. Due to the strong surface enhancement performance of Ag NPs, when PS NPLs were surrounded by Ag NPs, their Raman spectra could be largely enhanced, which can be used as a sensitive probe to detect small PS NPLs (50 nm). This study proposed an effective method to identify unknown plastic particles in water samples since SERS can record “fingerprint” molecular vibrations at the nano-scale.

2.3.2. Single particle ICP-MS

ICP-MS is a commonly used technique to quantify metal and metalloid elements. When analyzing NPs, a sample-digestion step is always needed to avoid the incomplete atomization of particles. However, this destructive operation hinders the speciation analysis of different species, e.g., the particles and the ions, unless a pre-isolation process is conducted before digestion [86]. In recent years, single particle ICP-MS (sp-ICP-MS) has shown great potential in the quantification of NPs in environmental samples. In the single-particle detection mode, ionic species would generate a constant signal, whereas particles would produce a pulse of ions. Therefore, when the NP suspension is sufficiently diluted to ensure only one particle is introduced into ICP-MS within the integral time, the frequency of the pulses is proportional to the number of the NPs, while the intensity of the pulse is related to the number of atoms in the particle [87]. Therefore, besides the low detection of limit, multiple types of information on NPs can be obtained by sp-ICP-MS, including the particle mass concentration, the particle number concentration, and the particle size distribution, which makes sp-ICP-MS a powerful technique for NP characterization in complex matrices.

However, sp-ICP-MS also suffers from many difficulties in the determination of NPs. On the one hand, the sensitivity of some elements is relatively low, resisting the detection of small particles. For instance, the Au-, Ag-, and Pd-based NPs can be easily detected with size detection limits below 20 nm due to the high sensitivity, while the analysis of Se- and Si-based NPs is rather difficult [88]. Currently, the determination of NPs with diameters below 10 nm remains a challenge. On the other hand, it is hard to set the threshold to distinguish NPs from background signals in some situations. Due to the coexistence of ionic counterparts and the broad size distribution of NPs, the boundary between NPs and ions is vague, making the quantification rather difficult. To address this challenge, many efforts have been devoted, including using alternative isotopes [89,90], suppressing isobaric/polyatomic interferences by using reaction gas [91,92], and removing coexisted ions by pretreatment steps [93]. Through these approaches, the performance has been improved to a certain degree. Furthermore, the commonly used sp-ICP-MS can only detect one isotope, which limits its application in the determination of composite NPs. This problem can be solved by the time-of-flight (TOF) mass analyzer [94]. This multi-element determination shows a promising application in source tracking. For example, elements in engineered NMs mainly exist as pure or single ones, while natural NMs usually contain multi-elements, which can be used to differentiate engineered and natural NMs [95].

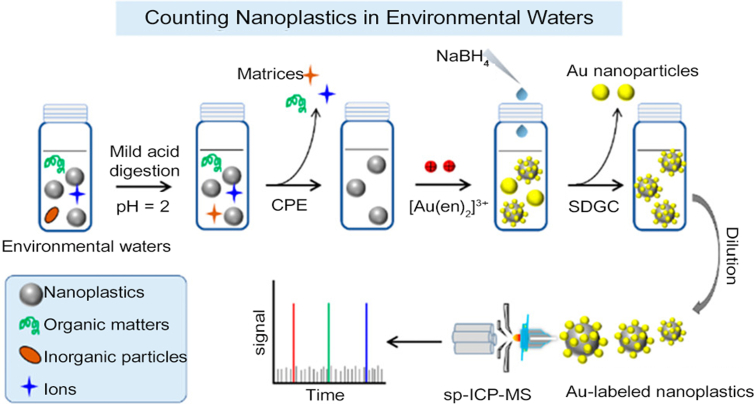

The sp-ICP-MS technique also shows potential in NPL determination. Although great progress has been made during the past decade, quantification of the particle number concentration of NPLs remains a great challenge due to their small sizes. Through tracking 13C+ by sp-ICP-MS, Bolea-Fernandez et al. [96] first proposed a facile method for the quantification of plastic particles with sizes down to 1 μm. However, due to the low sensitivity of carbon, it is rather difficult to detect smaller particles in a direct analysis manner. Great efforts have been made on the indirect determination, i.e., labeling metals on plastic surfaces and then counting NPLs by the number of metal pulses with sp-ICP-MS. Jiménez-Lamana et al. [97] labeled negatively charged carboxylated PS NPLs with positively charged Au NPs and thus realized the particle number concentration quantification. Given the complexity of NPLs in the real environment, the grafting by electrostatic attraction would not be universal. Recently, Lai et al. [98] developed a systematic method for the pretreatment and counting of NPLs in environmental waters. A pretreatment procedure, including mild acid digestion and sequential dual CPE, was performed to eliminate the interference of salt, natural organic matter (NOM), and other inorganic NPs in environmental waters. After that, all types of common NPLs, such as PE, PET, PS, and PVC, could be labeled by in situ growth of Au NPs, which allowed the counting of NPLs by sp-ICP-MS. Even NPLs with sizes down to 50 nm could be detected (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Schematic diagram of counting NPLs in environmental waters based on sp-ICP-MS technique. Reprinted with permission from ref. [98]. Copyright (2021) American Chemical Society. NPLs, nanoplastics; sp-ICP-MS, single particle inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry; SDGC, sucrose density gradient centrifugation; CPE, cloud point extraction.

2.3.3. Py-GC/MS

Py-GC/MS is one of the most effective methods for the analysis of organic particles, such as plastics, black carbon, and other materials that are difficult to be decomposed [5,[99], [100], [101]]. Samples are pyrolyzed into gaseous products in a furnace without oxygen, which are transferred into GC for separation. The degraded products are then introduced to MS for detection and quantification based on the fingerprint of each polymer [18,102,103]. Typically, pyrolysis conditions (e.g., the pyrolysis temperature and time) and the mass of the sample could affect the products of plastics [104]. To improve the sensitivity of Py-GC/MS, an optimization step can be conducted.

Py-GC/MS is still hampered by the relatively high limit of detection (about 4 mg/L for PS) for the direct analysis of NPLs in the environment [105]. Thus, an enrichment procedure is always required. The CPE method coupled with thermal decomposition allowed 500 times enrichment of NPLs in water, and a detection limit of 0.6 μg/L could be achieved by Py-GC/MS [48]. Recently, alkylated Fe3O4 particles have been shown to efficiently capture NPLs by forming Fe3O4-NPL agglomerates. After membrane filtration, the aggregates along with the membrane could be directly determined by Py-GC/MS, allowing the detection of PS NPLs as low as 0.02 μg/L in real environmental waters [18].

The pyrolysis products of different plastics and organic substances in the environment may overlap, which increases the difficulty in plastic identification. For example, styrene, the main pyrolysis product of PS, may also originate from the degradation of PET and chitin in the environment [19,105]. For some types of plastics lacking the characteristic pyrolysis products, such as PE and PVC, it is not an easy task to distinguish them from various environmental materials by traditional Py-GC/MS.

In order to understand the application scope of different analytical methods more intuitively, these extraction, separation, and identification approaches were further compared, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of different analytical methods.

| Analytical methods | Applicability | Advantages | Limitations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extraction methods | ||||

| Membrane filtration | Nanomaterials and nanoplastics | Low cost, easy handling, and high efficiency Some materials can be used as adsorbents. |

No selectivity, high filtration resistance for small particles, and clog of pore size during operation | [[30], [31], [32], [33]] |

| CPE | Nanomaterials and nanoplastics | Low cost, easy handling, high extraction efficiency, and the original size and shape of nanoparticles preserved | Limited enrichment factor | [[39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48]] |

| MSPE | Nanomaterials and nanoplastics | High selectivity after surface modification, easy handling, easy separation and collection, and high enrichment factor | Specific surface modification for different targets, adsorption of tiny materials on vessel surfaces | [18,49,51,52] |

| Separation methods | ||||

| SEC | Nanomaterials and nanoplastics | High separation efficiency, easy operation, and capable to coupling with various detector | Only a small volume of sample can be analyzed. | [54,[56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62]] |

| FFF | Nanomaterials and nanoplastics | High separation efficiency and capable of coupling with various detector Large volume samples can be analyzed. |

This technique is complex that experienced workers are needed to optimize multistep parameters. | [71,73,[75], [76], [77]] |

| Detection methods | ||||

| SERS | Nanomaterials and nanoplastics | Non-destructive No sample preparation is normally required. |

Expensive instruments Probe molecules are needed to detect NMs, and only several NMs can be detected. The detection of NPLs needs to be improved. |

[84,85] |

| sp-ICP-MS | Nanomaterials and nanoplastics | High sensitivity, and easy sample preparation for metal NMs | NPLs need to be labeled with Au NPs for detection. Multi-elements detection is restricted. |

[[87], [88], [89], [90], [91], [92], [93], [94], [95], [96], [97], [98]] |

| Py-GC/MS | Nanoplastics | Independent on particle size and shape | Destructive, and relatively high detection limits It may be not representative for heterogenous samples. |

[18,32,48,101,102,104] |

3. Sources and formation

3.1. Anthropogenic sources

Due to their unique optical, electronic, magnetic, and catalytic properties, as addressed above, NMs demonstrate a broad application in a variety of fields. Nano-TiO2, one of the most commercialized NMs, is extensively incorporated in cosmetics, foods, and daily used items, such as candies, sunscreens, toothpaste, papers, and paints because of the chemical inertness and excellent UV filtering function [106]. The entire life cycle of these products, from the production and transportation of NMs, the fabrication of NM-containing goods, to the abrasion during use and the final disposal, can lead to the release of NMs into the environment [107].

Apart from engineered NMs, unintentionally generated nanoparticulate pollutants (e.g., NPLs) are also abundant in some compartments. It was estimated that about 6300 Mt of plastic waste had been produced in 2015, most of which was dumped or landfilled in the natural system [11]. The marine environment is one of the main sinks for plastic fragments. Previous studies reported that more than 5 trillion plastic items were floating in the sea [108]. The formation of NPLs is due to the continuous degradation of plastic debris. Some researchers even predicted that NPLs would be ubiquitous in the environment. Some human-related activities also lead to the incidental production of NPs. For example, silver bromide is wildly used in the photography industry due to its photosensitivity. Once silver bromide enters the environment, light exposure can trigger its decomposition, possibly resulting in the formation of Ag NPs [109].

3.2. Natural sources

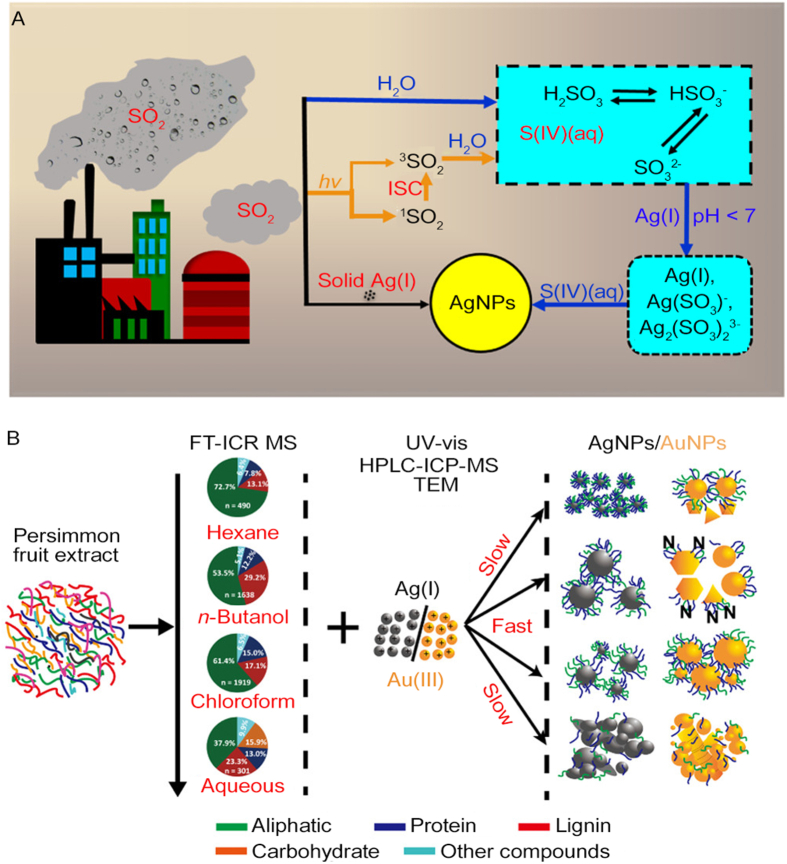

Before the large-scale production and application of NMs, the presence of nanoparticulate Au and Ag in deposits, mining regions, and even fluvial and estuarine waters were reported [[110], [111], [112]], showing that nanoparticulate pollutants could be formed naturally. A prior study [113] revealed that after Ag and Cu objects (such as wires, earrings, knives, and forks) were exposed to air with a humidity greater than 50% for several weeks, Ag NPs and Cu NPs could be generated spontaneously in the vicinity of these bulk objects. A three-stage pathway was proposed. In stage 1, the oxidation of Ag and Cu objects in the air resulted in the formation of metal ions. Due to the high air humidity, a water layer could be formed on the objects, and metal ions could then diffuse away from the parent materials through the water layer. In the final stage, the reduction of metal ions induced the generation of NPs. However, the exact reduction mechanism was not revealed. Recently, the SO2-related reduction of Ag ions was reported [114]. In moist environments, the dissolution of gaseous SO2 in water induced the formation of sulfite ions, which acted as the reductant to promote the nucleation and growth of silver atoms. Furthermore, sunlight irradiation induced the formation of triplet SO2, which could significantly accelerate the occurrence of Ag NPs (Fig. 5A). Since pH values influenced the speciation of Ag(I) and S(IV), the SO2-dominated generation of Ag NPs was pH-dependent.

Fig. 5.

Natural sources of nanomaterials. (A) Pathway for the generation of Ag NPs reduced by sulfur dioxide. Reprinted with permission from ref. [114]. Copyright (2021) American Chemical Society. (B) Phytosynthesis mechanism of Au NPs and Ag NPs. Reprinted with permission from ref. [126]. Copyright (2022) American Chemical Society.

NOM, mainly derived from the decomposition of terrestrial and aquatic organisms, is rich in a variety of functional groups, including carboxyls, hydroxyls, ketones, and quinones [29]. NOM is ubiquitous in the ecosystem and has long been considered a natural reducing agent. Sharma et al. [112,115] revealed that humic acid (HA) and fulvic acid from different sources could trigger the generation of Ag NPs under environmentally relevant conditions. High temperatures significantly improved the reaction rate. The characteristic surface plasmon resonance of Ag NPs appeared within 90 min at 90 °C, while it took several days at 22 °C. The reduction of ionic Au (III) to Au NPs by NOM was also reported [116]. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy results revealed that phenolic, alcoholic, and aldehyde groups in NOM played key roles in the reductive process. NOM also acted as the capping agent to keep the stability of Ag NPs and Au NPs. Further studies revealed that sunlight irradiation dramatically accelerated the NOM-mediated formation of Ag NPs and Au NPs [117,118]. The generation of NPs was favored at high pH values due to the relatively low redox potential of HA. Photoirradiation of phenolic groups of NOM induced the production of superoxide, which was responsible for the photoreduction of NPs. Furthermore, the dissolved O2 greatly promoted the formation of Ag NPs, showing the complex roles of O2 in the transformation of Ag NPs, as dissolved O2 is generally believed to facilitate the oxidation of Ag NPs and induce the dissolution of Ag ions.

NOM is a mixture that contains complex substances with various molecular weights (MWs). To reveal the specific roles of different components in the reduction of Ag NPs, Suwannee River NOM was fractionated by MW to examine the photoreduction ability. Though different fractions of NOM exhibited distinct apparent reaction rates, monochromatic radiation, and light attenuation correction implied that the difference mainly originated from their varied light attenuation effects. However, the high MW components have better stabilization ability due to their stronger steric hindrance effect [119]. The natural generation of Ag NPs was also affected by other environmental conditions. Common metal ions in the aquatic environment, such as Fe2+ and Fe3+, could act as effective electron shuttles between Ag ions and NOM to enhance the formation of Ag NPs [120]. Freezing in cold regions could accelerate the photoreduction of Ag ions, probably due to the increased local Ag ion concentrations after freezing [121].

Plants and microorganisms in the environment also can reduce some metallic or non-metallic ions to form NPs. The extracts of various plants, such as Allium ampeloprasum and Alcea rosea leaf, marine alga, and persimmon fruit, could synthesize Au NPs and Ag NPs at room temperature [[122], [123], [124], [125]]. However, because of the complex components of plant extracts, the reduction mechanism is still unclear. Recently, Huo et al. explored the mechanisms of phytosynthesis of NPs by molecular characterization of different fractions of plant extracts [126]. By taking persimmon fruit as the model, a sequential extraction strategy was used to separate the pristine extract into four fractions with distinct polarities (Fig. 5B). Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry (FT-ICR MS) measurements showed that the hexane fraction was rich in aliphatic compounds, and near-spherical NPs with high stability could be produced. However, the reduction rate was relatively low due to their weak reducing ability. The n-butanol fraction contained a large number of phenolic structures, which contributed to the fast reduction of metal ions. Both strong and weak reducing compositions were included in the chloroform fraction, while the remaining aqueous fraction mainly contained carbohydrates. The aliphatic compounds with low oxygen contents acted as the capping agent to keep the stability of NPs, whereas cyclic and aromatic substances played key roles in shaping the morphology of NPs.

Biosynthesis of NPs, such as Ag NPs, Au NPs, and Se NPs, is considered to resist the toxicity of some metallic or non-metallic ions [[127], [128], [129]]. Several mechanisms have been proposed, including non-enzymatic reduction, enzyme-mediated reduction, and free radical-mediated reduction [109]. It was demonstrated that the fungus Fusarium oxysporum could produce superoxide after Ag+ exposure, which contributed to the extracellular biosynthesis of Ag NPs. Further investigation showed that the addition of a superoxide scavenger or the inhibitor of NADH oxidases could hinder the generation of Ag NPs, proving the superoxide-dependent mechanism for the formation of Ag NPs [130].

4. Transformations

4.1. Physical transformation

Due to the large specific surface area and high surface energy, nanoparticulate pollutants are thermodynamically unstable [131]. Although the capping agents or the coating of macromolecules in the natural system can stabilize particles to some extent, the variation of surrounding environments may change the surface chemistry, inducing the attachment of neighboring particles. The aggregation of nanoparticulate pollutants was influenced by a series of factors, including the surface coating agent, ionic strength, electrolyte types, NOM, and other natural colloids [[132], [133], [134], [135], [136], [137]].

Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) and citrate are two common capping agents in the synthesis of NMs, which can provide steric repulsion and electrostatic interaction, respectively, to maintain the stability of NMs. Typically, PVP-capped NMs are more resistant to high salinity. For example, critical coagulation concentration (CCC) values of PVP-coated, citrate-coated, and baer Ag NPs were 447.27, 109.68, and 8.10 mM in NaCl solutions, respectively. Other polymers, such as polyethylenimine and polyvinyl alcohol, are also frequently used as coating agents. Their stabilizing effects are closely related to the adsorption mechanism, their MWs, the attached amount, and the conformation of the adsorbed layer [131].

As most nanoparticulate pollutants are charged, electrolytes can compress the electrical double layer, thereby inducing the adhesion of adjacent particles [138]. Polyvalent electrolytes are more effective in reducing the repulsion than monovalent ions, and thus their destabilizing ability is stronger. For example, the CCC value of PS NPLs was 309.7 mM in NaCl solutions, while reduced to 28.9 mM in CaCl2 [134].

NOM in the environment was reported to adsorb on the surface of nanoparticulate pollutants to affect their dispersal state. Generally, NOM can exhibit both electrostatic repulsion and steric forces to improve the stability of particles. The cation bridging effect can occur at high concentrations of NOM and polyvalent electrolytes, inducing the attachment of particles to form cross-linking aggregates [134]. However, the specific components in NOM accounting for this phenomenon remain elusive. By fractionating Suwannee River NOM based on MW, Shen et al. [135] found that the stability of fullerene was positively correlated with the MW of NOM fractions in NaCl and low concentrations of Ca2+/Mg2+solutions, indicating that the high MW components played key roles in enhancing the stability of nanoparticulate pollutants. However, at high concentrations of Ca2+/Mg2+, high MW fractions (>30 kD) accelerated the coalescence of fullerene. As Ca2+/Mg2+ were prone to associate with the hydrophobic regions of NOM, high MW fractions of NOM were more hydrophobic [139], thus attracting the binding of these cations.

Natural colloids are also omnipresent in the environment. Their concentrations typically range from 1 to 20 mg/L [140], which is much higher than that of nanoparticulate pollutants. Therefore, nanoparticulate pollutants are more likely to encounter natural colloids than themselves. Electrostatic attraction was the dominant force triggering the formation of heteroaggregates [133]. NOM adsorption can modify the surface charges, thus influencing the interaction with natural colloids.

In the aquatic environment, nanoparticulate pollutants tend to be concentrated in the water–air interface, called SML. SML enrichment was observed for Ag NPs with different surface coatings and sizes in indoor simulation experiments [84]. The enrichment factors ranged from 58.6 to 135.7 after 72 h. Brownian motion was regarded as the driving force inducing the SML enrichment, while electrostatic repulsion between neighboring particles hindered the migration of particles to SML. Therefore, nanoparticulate pollutants with different charges exhibited distinct enrichment behaviors. As environmental factors, such as pH, ionic strength, and NOM, can affect the surface properties of nanoparticulate pollutants, the fate of nanoparticulate pollutants may vary significantly under different environmental conditions [141]. Meanwhile, nanoparticulate pollutants trapped in the SML are more likely to be exposed to O2, sunlight, and other co-existing contaminants, which may accelerate their aging and further transformation [84].

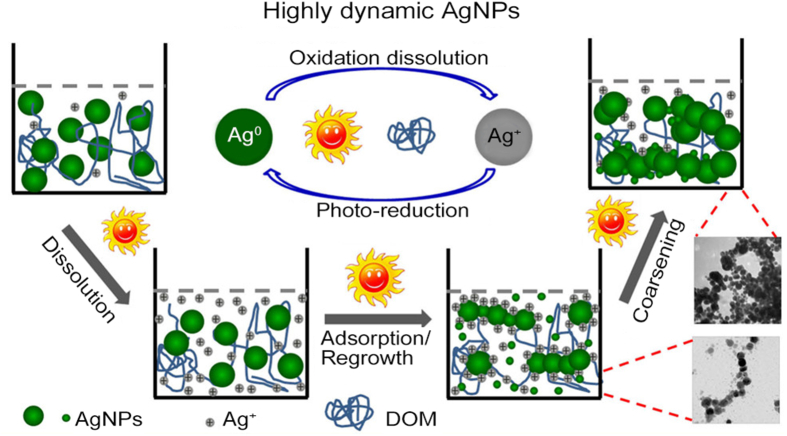

4.2. Chemical transformation

Once released into the environment, nanoparticulate pollutants may undergo various chemical transformations, especially for metal and metal oxide NMs, such as Ag, Fe, ZnO, and CuO NPs. Ag NPs have been extensively studied due to their highly dynamic nature and large production and application. Liu et al. [142] showed that the release of dissolved silver was a cooperative oxidation process related to O2 and protons. High temperature and decreasing pH values accelerated the ion release, whereas the presence of NOM inhibited the release. Ag NP suspensions (0.05 mg/L) could even be completely dissolved after several days in air-saturated water at room temperature. Sunlight could enhance the oxidation of Ag NPs initially due to the increase in local temperature. However, long-time light irradiation could induce the aggregation of Ag NPs, resulting in the decrease of ion release kinetics. Meanwhile, the oxidation of Ag NPs and reduction of released Ag+ to form Ag NPs could both occur in the sunlit NOM-rich water due to the medium redox potential of silver ( V) (Fig. 6). This phenomenon was general in natural aquatic systems under different environmental conditions, even in the presence of strong ligands Cl and S2− [143]. As the two reverse processes occur simultaneously, the dual stable isotope labeling method could be used to monitor the transformation kinetics of Ag NPs and Ag+ [144]. When both Ag NPs and Ag+ were present in the environment, the transformation between them seemed much more complicated and closely dependent on the surrounding water chemistry, such as sunlight, pH values, temperature, and co-existing ions.

Fig. 6.

Pathway for the transformation of Ag NPs in aquatic environments. Reprinted with permission from ref. [143]. Copyright (2014) American Chemical Society.

In the presence of other ligands, such as chloride and sulfide, metallic NPs can undergo further chlorination and sulfidation. Previous studies showed that Cl ions in Ag NP suspensions could affect the stability of Ag NPs, and the formation of AgCl layers on the surface of Ag NPs induced the crosslinking of neighboring NPs [145]. The final Ag species in the system was dependent on the Cl/Ag ratio [146]. In the anoxic environment, such as river and lake sediment and wastewater treatment plants, sulfidation of metallic NPs, such as Ag NPs, Cu NPs, and ZnO NPs, is easily happened [[147], [148], [149], [150]]. The solubility of metal sulfide largely reduced, resulting in a much lower release of metal ions, and thus decreased the toxicity of metallic NPs [147,149]. Therefore, sulfidation of metallic NPs in the environment is regarded as a natural detoxification pathway [151].

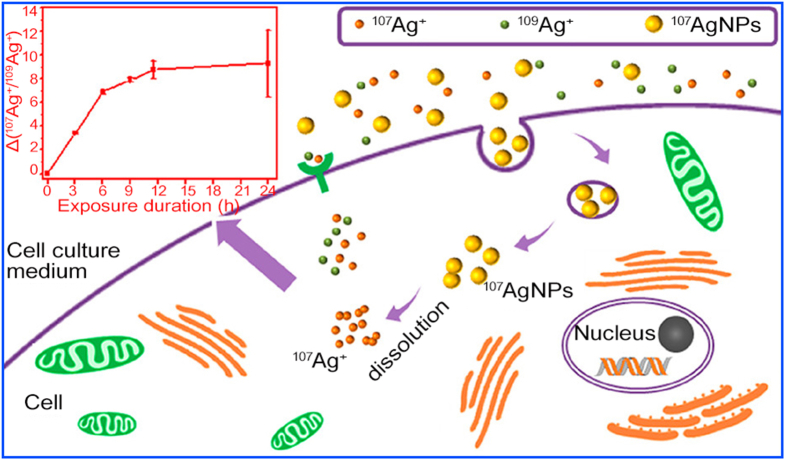

4.3. Biological transformation

Nanoparticulate pollutants released into the natural ecosystem can pose a threat to the environmental biota. Due to the small size, nanoparticulate contaminants may pass through the cellular barrier and be internalized by organisms. PS NPLs (100 nm) could be ingested by the root of cucumber and be further transported to stems and leaves after several days. The presence of PS NPLs in the tissues was directly identified by scanning electron microscopy [152]. NPLs in the plants were relatively stable, whereas, for other NMs, such as Ag NPs, CuO NPs, and ZnO NPs, complex transformation can occur in organisms [[153], [154], [155]]. The Trojan-horse mechanism, i.e., the dissolution of high concentrations of metal ions after internalization, is thought to be the main source of toxicity for these NPs. By labeling Ag NPs and Ag ions with two enriched stable Ag isotopes (107Ag NPs and 109AgNO3), Yu et al. [62] studied the transformation of Ag NPs and Ag ions in HepG2 and A549 cells to further identify the mechanism. Cells were co-exposed with 107Ag NPs and 109AgNO3 at non-toxic doses, and then 107Ag NPs, ionic 109Ag+ and 107Ag+ in cells were determined separately. Results showed that the fractions of 107Ag + to total 107Ag and the ratios of 107Ag+/109Ag+ in cells increased gradually over time. Based on the almost identical uptake rates of 107Ag+ and 109Ag+, the observation proved the intracellular dissolution of 107Ag NPs (Fig. 7). The biotransformation of Ag NPs was also reported in E. coli [61] and rats [156]. After intravenous injection of Ag NPs in rats, Ag could be transferred and accumulated in almost all organs, including the heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, and even brain, of which most were present as complex Ag(I) forms. Only small proportions of Ag NPs were detected in the liver and lung, indicating the fast oxidation of Ag NPs in vivo. The contact with thiols could induce the complete dissolution of Ag NPs in a short time. Otherwise, Ag NPs could retain the pristine core size. Meanwhile, the co-exposure of Ag+ could significantly enhance the dissolution of administered Ag NPs by the overexpression of metallothioneins [61].

Fig. 7.

Intracellular dissolution of Ag NPs in cells revealed by double stable isotope tracing. Reprinted with permission from ref. [62]. Copyright (2019) American Chemical Society.

5. Conclusion

Due to the vast production and application of NMs and plastics, nanoparticulate pollutants ultimately find their way into the ecosystem. Great efforts have been made in the analysis of nanoparticulate pollutants over the past two decades, both in the development of new analytical methods and the improvement of instrument resolution and sensitivity. In particular, the progress of coupled technologies and sp-ICP-MS enables the separation, characterization, and quantification of target pollutants in a single run. However, there is still a long way to go. Most of these methods focus on relatively simple samples (e.g., water samples), while the capability to analyze complex environmental samples is still questioned. Once released into the environment or uptake by organisms, nanoparticulate pollutants would be trapped in “coronas”, such as NOM, proteins, biofilms, and minerals. A proper pretreatment process is needed to liberate them from these matrices. However, the main concern is that the dispersion state and surface properties of nanoparticulate pollutants may alter after treatment. Reliable pretreatment methods that can preserve the pristine state of nanoparticulate pollutants are still required. In situ characterization techniques may solve this problem during analysis and deserve further investigation. Advanced MS techniques, such as laser ablation ICP-MS, FT-ICR MS, and secondary ion mass spectrometry with a TOF mass analyzer, are promising for the in-situ analysis [23].

The physical and chemical transformations of nanoparticulate pollutants significantly affect their ultimate fate in the environment. Although extensive studies have been focused on this topic, most of them were conducted under simulated conditions in the laboratory. Additionally, the concentrations (mg/L and μg/L levels) are often several orders of magnitude higher than those in the natural environment (ng/L and pg/L levels or even lower). The behaviors of nanoparticulate pollutants ought to be studied under more environmentally relevant conditions. Long-term field experiments or mesocosm simulation experiments may contribute to predicting their fate and risks in the environment.

NPLs refer to hundreds of synthetic polymers with different components. The determination of each type of NPLs is impossible. In addition, NPLs have similar compositions to environmental organic substances, making it even harder to track and detect them. A universal index for determining NPLs, such as the total carbon content, is urgently needed [74]. Meanwhile, NPLs are believed to be ubiquitous in the natural system. The increasing use of plastic products, especially the abuse of disposable plastic bags, cups, and fast-food boxes, contributes to the generation of NPLs. Proper disposal of plastic waste and the development of proper substitutes are highly demanded.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42192571, 22076198, and 21827815).

References

- 1.Richardson S.D., Ternes T.A. Water analysis: emerging contaminants and current issues. Anal. Chem. 2022;94:382–416. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.1c04640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nguyen B., Claveau-Mallet D., Hernandez L.M., Xu E.G., Farner J.M., Tufenkji N. Separation and analysis of microplastics and nanoplastics in complex environmental samples. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019;52:858–866. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gigault J., Halle A.T., Baudrimont M., Pascal P.Y., Gauffre F., Phi T.L., et al. Current opinion: what is a nanoplastic? Environ. Pollut. 2018;235:1030–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li P., Li Q.C., Hao Z.N., Yu S.J., Liu J.F. Analytical methods and environmental processes of nanoplastics. J. Environ. Sci. 2020;94:88–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2020.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ivleva N.P. Chemical analysis of microplastics and nanoplastics: challenges, advanced methods, and perspectives. Chem. Rev. 2021;121:11886–11936. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hartmann N.B., Hüffer T., Thompson R.C., Hassellöv M., Verschoor A.J., Daugaard A.E., et al. Are we speaking the same language? Recommendations for a definition and categorization framework for plastic debris. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019;53:1039–1047. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b05297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malakar A., Kanel S.R., Ray C., Snow D.D., Nadagouda M.N. Nanomaterials in the environment, human exposure pathway, and health effects: a review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;759 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inshakova E., Inshakov O. MATEC Web of Conferences. 2017. World market for nanomaterials: structure and trends. 129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Y., Lei C., Lin D. Environmental behaviors and biological effects of engineered nanomaterials: important roles of interfacial interactions and dissolved organic matter. Chin. J. Chem. 2021;39:232–242. doi: 10.1002/cjoc.202000466. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li X., He F., Wang Z., Xing B. Roadmap of environmental health research on emerging contaminants: inspiration from the studies on engineered nanomaterials. Eco Environ. Health. 2022;1:181–197. doi: 10.1016/j.eehl.2022.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geyer R., Jambeck J.R., Law K.L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 2017;3 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1700782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ivleva N.P., Wiesheu A.C., Niessner R. Microplastic in aquatic ecosystems. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:1720–1739. doi: 10.1002/anie.201606957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azimzada A., Jreije I., Hadioui M., Shaw P., Farner J.M., Wilkinson K.J. Quantification and characterization of Ti-, Ce-, and Ag-nanoparticles in global surface waters and precipitation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021;55:9836–9844. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.1c00488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gondikas A.P., von der Kammer F., Reed R.B., Wagner S., Ranville J.F., Hofmann T. Release of TiO2 nanoparticles from sunscreens into surface waters: a one-year survey at the old danube recreational lake. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014;48:5415–5422. doi: 10.1021/es405596y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Labille J., Slomberg D., Catalano R., Robert S., Apers-Tremelo M.L., Boudenne J.L., et al. Assessing UV filter inputs into beach waters during recreational activity: a field study of three French mediterranean beaches from consumer survey to water analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;706 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.136010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim B., Park C.-S., Murayama M., Hochella M.F., Jr. Discovery and characterization of silver sulfide nanoparticles in final sewage sludge products. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010;44:7509–7514. doi: 10.1021/es101565j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu L., Wang Z., Zhao J., Lin M., Xing B. Accumulation of metal-based nanoparticles in marine bivalve mollusks from offshore aquaculture as detected by single particle ICP-MS. Environ. Pollut. 2020;260 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Q., Lai Y., Li P., Liu X., Yao Z., Liu J., et al. Evaluating the occurrence of polystyrene nanoparticles in environmental waters by agglomeration with alkylated ferroferric oxide followed by micropore membrane filtration collection and Py-GC/MS analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022;56:8255–8265. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.2c02033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.ter Halle A., Jeanneau L., Martignac M., Jardé E., Pedrono B., Brach L., et al. Nanoplastic in the north atlantic subtropical gyre. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017;51:13689–13697. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.7b03667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davranche M., Lory C., Juge C.L., Blancho F., Dia A., Grassl B., et al. Nanoplastics on the coast exposed to the north atlantic gyre: evidence and traceability. NanoImpact. 2020;20 doi: 10.1016/j.impact.2020.100262. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wahl A., Le Juge C., Davranche M., El Hadri H., Grassl B., Reynaud S., et al. Nanoplastic occurrence in a soil amended with plastic debris. Chemosphere. 2021;262 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.127784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Materić D., Kasper-Giebl A., Kau D., Anten M., Greilinger M., Ludewig E., et al. Micro- and nanoplastics in alpine snow: a new method for chemical identification and (semi)quantification in the nanogram range. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020;54:2353–2359. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.9b07540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang C., Liu S., Zhang T., Liu Q., Alvarez P.J.J., Chen W. Current methods and prospects for analysis and characterization of nanomaterials in the environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022;56:7426–7447. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.1c08011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hochella M.F., Mogk D.W., Ranville J., Allen I.C., Luther G.W., Marr L.C., et al. Natural, incidental, and engineered nanomaterials and their impacts on the earth system. Science. 2019;363:1414. doi: 10.1126/science.aau8299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dang F., Wang Q.Y., Huang Y.N., Wang Y.J., Xing B.S. Key knowledge gaps for one health approach to mitigate nanoplastic risks. Eco Environ. Health. 2022;1:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.eehl.2022.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Helal M., Hartmann N.B., Khan F.R., Xu E.G. Time to integrate “one health approach” into nanoplastic research. Eco Environ. Health. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.eehl.2023.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu S., Yin Y., Liu J. Silver nanoparticles in the environment. Environ. Sci. Process Impacts. 2013;15:78–92. doi: 10.1039/c2em30595j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dwivedi A.D., Dubey S.P., Sillanpää M., Kwon Y.N., Lee C., Varma R.S. Fate of engineered nanoparticles: implications in the environment. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2015;287:64–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.12.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu S.J., Liu J.F., Yin Y.G., Shen M.H. Interactions between engineered nanoparticles and dissolved organic matter: a review on mechanisms and environmental effects. J. Environ. Sci. 2018;63:198–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2017.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou X.X., Lai Y.J., Liu R., Li S.S., Xu J.W., Liu J.F. Polyvinylidene fluoride micropore membranes as solid-phase extraction disk for preconcentration of nanoparticulate silver in environmental waters. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017;51:13816–13824. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.7b04055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang L., He S., Wang D., Li C., Zhou X., Yan B. Polyvinylidene fluoride micropore membrane for removal of the released nanoparticles during the application of nanoparticle-loaded water treatment materials. J. Clean. Prod. 2020;261 doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121246. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Q.C., Lai Y.J., Yu S.J., Li P., Zhou X.X., Dong L.J., et al. Sequential isolation of microplastics and nanoplastics in environmental waters by membrane filtration, followed by cloud-point extraction. Anal. Chem. 2021;93:4559–4566. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.0c04996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hernandez L.M., Yousefi N., Tufenkji N. Are there nanoplastics in your personal care products? Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2017;4:280–285. doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.7b00187. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goto K., Taguchi S., Fukue Y., Ohta K., Watanabe H. Spectrophotometric determination of manganese with 1-(2-pyridylazo)-2-naphthol and a nonionic surfactant. Talanta. 1977;24:752–753. doi: 10.1016/0039-9140(77)80206-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watanabe H., Tanaka H. Nonionis surfactant as a new solvent for liquid-liquid-extraction of zinc (ii) with 1-(2-pyridylazo)-2-2naphthol. Talanta. 1978;25:585–589. doi: 10.1016/0039-9140(78)80151-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hinze W.L., Pramauro E. A critical review of surfactant-mediated phase separations (cloud-point extractions): theory and applications. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 1993;24:133–177. doi: 10.1080/10408349308048821. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bezerra M.D., Arruda M.A.Z., Ferreira S.L.C. Cloud point extraction as a procedure of separation and pre-concentration for metal determination using spectroanalytical techniques: a review. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2005;40:269–299. doi: 10.1080/05704920500220880. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quina F.H., Hinze W.L. Surfactant-mediated cloud point extractions: an environmentally benign alternative separation approach. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1999;38:4150–4168. doi: 10.1021/ie980389n. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu J.F., Liu R., Yin Y.G., Jiang G.B. Triton X-114 based cloud point extraction: a thermoreversible approach for separation/concentration and dispersion of nanomaterials in the aqueous phase. Chem. Commun. 2009:1514–1516. doi: 10.1039/b821124h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu J.F., Chao J.B., Liu R., Tan Z.Q., Yin Y.G., Wu Y., et al. Cloud point extraction as an advantageous preconcentration approach for analysis of trace silver nanoparticles in environmental waters. Anal. Chem. 2009;81:6496–6502. doi: 10.1021/ac900918e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tan Z.Q., Liu J.F., Liu R., Yin Y.G., Jiang G.B. Visual and colorimetric detection of Hg2+ by cloud point extraction with functionalized gold nanoparticles as a probe. Chem. Commun. 2009:7030–7032. doi: 10.1039/b915237g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chao J.B., Liu J.F., Yu S.J., Feng Y.D., Tan Z.Q., Liu R., et al. Speciation analysis of silver nanoparticles and silver ions in antibacterial products and environmental waters via cloud point extraction-based separation. Anal. Chem. 2011;83:6875–6882. doi: 10.1021/ac201086a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hartmann G., Hutterer C., Schuster M. Ultra-trace determination of silver nanoparticles in water samples using cloud point extraction and etaas. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2013;28:567–572. doi: 10.1039/c3ja30365a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yu S., Chao J., Sun J., Yin Y.G., Liu J.F., Jiang G.B. Quantification of the uptake of silver nanoparticles and ions to HepG2 cells. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013;47:3268–3274. doi: 10.1021/es304346p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li L.X., Hartmann G., Döblinger M., Schuster M. Quantification of nanoscale silver particles removal and release from municipal wastewater treatment plants in Germany. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013;47:7317–7323. doi: 10.1021/es3041658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hartmann G., Baumgartner T., Schuster M. Influence of particle coating and matrix constituents on the cloud point extraction efficiency of silver nanoparticles (Ag-NPs) and application for monitoring the formation of Ag-NPs from Ag+ Anal. Chem. 2014;86:790–796. doi: 10.1021/ac403289d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang R., Li Q., Zhou W., Yu S., Liu J. Speciation analysis of selenium nanoparticles and inorganic selenium species by dual-cloud point extraction and ICP-MS determination. Anal. Chem. 2022;94:16328–16336. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.2c03018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou X.X., Hao L.T., Wang H.T.Z., Li Y.J., Liu J.F. Cloud-point extraction combined with thermal degradation for nanoplastic analysis using pyrolysis gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2019;91:1785–1790. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b04729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Su S., Chen B., He M., Xiao Z., Hu B. A novel strategy for sequential analysis of gold nanoparticles and gold ions in water samples by combining magnetic solid phase extraction with inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2014;29:444–453. doi: 10.1039/c3ja50342a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baig R.B.N., Varma R.S. Organic synthesis via magnetic attraction: benign and sustainable protocols using magnetic nanoferrites. Green Chem. 2013;15:398–417. doi: 10.1039/c2gc36455g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tolessa T., Zhou X.X., Amde M., Liu J.F. Development of reusable magnetic chitosan microspheres adsorbent for selective extraction of trace level silver nanoparticles in environmental waters prior to ICP-MS analysis. Talanta. 2017;169:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2017.03.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou X., Liu J., Yuan C., Chen Y. Speciation analysis of silver sulfide nanoparticles in environmental waters by magnetic solid-phase extraction coupled with ICP-MS. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2016;11:2285–2292. doi: 10.1039/C6JA00243A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sarcletti M., Park H., Wirth J., Englisch S., Eigen A., Drobek D., et al. The remediation of nano-/microplastics from water. Mater. Today. 2021;48:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.mattod.2021.02.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Knoppe S., Boudon J., Dolamic I., Dass A., Bürgi T. Size exclusion chromatography for semipreparative scale separation of Au-38(SR)(24) and Au-40(SR)(24) and larger clusters. Anal. Chem. 2011;83:5056–5061. doi: 10.1021/ac200789v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sivamohan R., Kasuya A. Direct production of nearly monosize and monodispersed Cds with a size near 1 nm. J. Electron. Mater. 1999;28:442–444. doi: 10.1007/s11664-999-0093-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhou X.X., Liu R., Liu J.F. Rapid chromatographic separation of dissoluble Ag(I) and silver-containing nanoparticles of 1-100 nanometer in antibacterial products and environmental waters. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014;48:14516–14524. doi: 10.1021/es504088e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhou X.X., Liu J.F., Geng F.L. Determination of metal oxide nanoparticles and their ionic counterparts in environmental waters by size exclusion chromatography coupled to ICP-MS. NanoImpact. 2016;1:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.impact.2016.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lai Y., Dong L., Sheng X., Chao J., Yu S., Liu J. Monitoring the Cd2+ release from Cd-containing quantum dots in simulated body fluids by size exclusion chromatography coupled with ICP-MS. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2022;414:5529–5536. doi: 10.1007/s00216-022-03976-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhou X., Liu J., Jiang G. Elemental mass size distribution for characterization, quantification and identification of trace nanoparticles in serum and environmental waters. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017;51:3892–3901. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b05539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dong L.J., Zhou X.X., Hu L.G., Yin Y.G., Liu J.F. Simultaneous size characterization and mass quantification of the in vivo core-biocorona structure and dissolved species of silver nanoparticles. J. Environ. Sci. 2018;63:227–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2017.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dong L.J., Lai Y.J., Yu S.J., Liu J.F. Speciation analysis of the uptake and biodistribution of nanoparticulate and ionic silver in escherichia coli. Anal. Chem. 2019;91:12525–12530. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b03359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yu S., Lai Y., Dong L., Liu J. Intracellular dissolution of silver nanoparticles: evidence from double stable isotope tracing. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019;53:10218–10226. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.9b03251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Giddings J.C. A new separation concept based on a coupling of concentration and flow nonuniformities. Separ. Sci. 1966;1:123–125. doi: 10.1080/01496396608049439. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Giddings J.C. Field-flow fractionation: analysis of macromolecular, colloidal, and particulate materials. Science. 1993;260:1456–1465. doi: 10.1126/science.8502990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Reschiglian P., Moon M.H. Flow field-flow fractionation: a pre-analytical method for proteomics. J. Proteonomics. 2008;71:265–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Qureshi R.N., Kok W.T. Application of flow field-flow fractionation for the characterization of macromolecules of biological interest: a review. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2011;399:1401–1411. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-4278-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Baalousha M., Stolpe B., Lead J.R. Flow field-flow fractionation for the analysis and characterization of natural colloids and manufactured nanoparticles in environmental systems: a critical review. J. Chromatogr. A. 2011;1218:4078–4103. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2011.04.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Moon M.H. Flow field-flow fractionation and multiangle light scattering for ultrahigh molecular weight sodium hyaluronate characterization. J. Separ. Sci. 2010;33:3519–3529. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201000414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bai Q., Yin Y., Liu Y., Jiang H., Wu M., Wang W., et al. Flow field-flow fractionation hyphenated with inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry: a robust technique for characterization of engineered elemental metal nanoparticles in the environment. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2021:110–131. doi: 10.1080/05704928.2021.1935272. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fraunhofer W., Winter G. The use of asymmetrical flow field-flow fractionation in pharmaceutics and biopharmaceutics. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2004;58:369–383. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2004.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Amde M., Tan Z.Q., Liu J. Separation and size characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles in environmental waters using asymmetrical flow field-flow fractionation. Talanta. 2019;200:357–365. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2019.03.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yi Z., Loosli F., Wang J., Berti D., Baalousha M. How to distinguish natural versus engineered nanomaterials: insights from the analysis of TiO2 and CeO2 in soils. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020;18:215–227. doi: 10.1007/s10311-019-00926-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gigault J., El Hadri H., Reynaud S., Deniau E., Grassl B. Asymmetrical flow field flow fractionation methods to characterize submicron particles: application to carbon-based aggregates and nanoplastics. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2017;409:6761–6769. doi: 10.1007/s00216-017-0629-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Li P., Lai Y.J., Li Q.C., Dong L.J., Tan Z.Q., Yu S.J., et al. Total organic carbon as a quantitative index of micro- and nano-plastic pollution. Anal. Chem. 2022;94:740–747. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.1c03114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]