Abstract

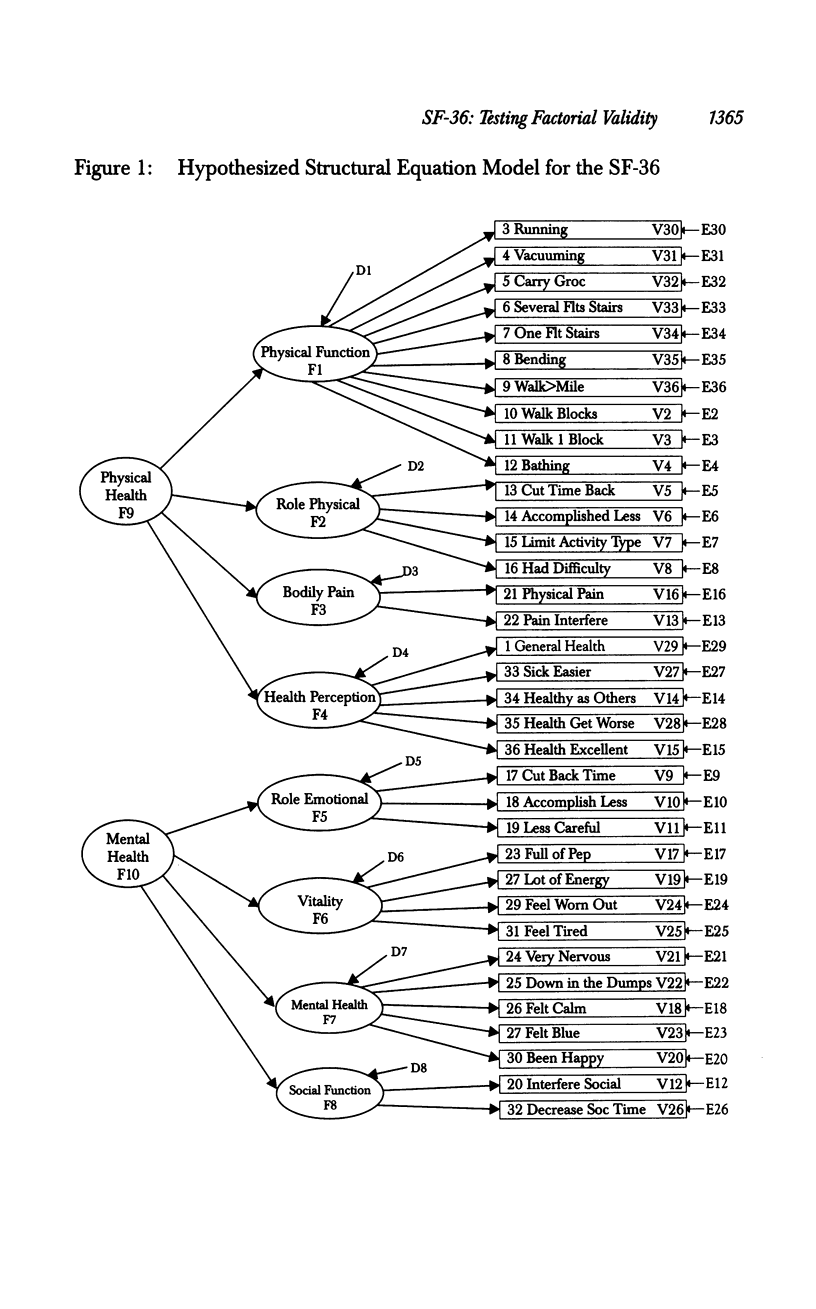

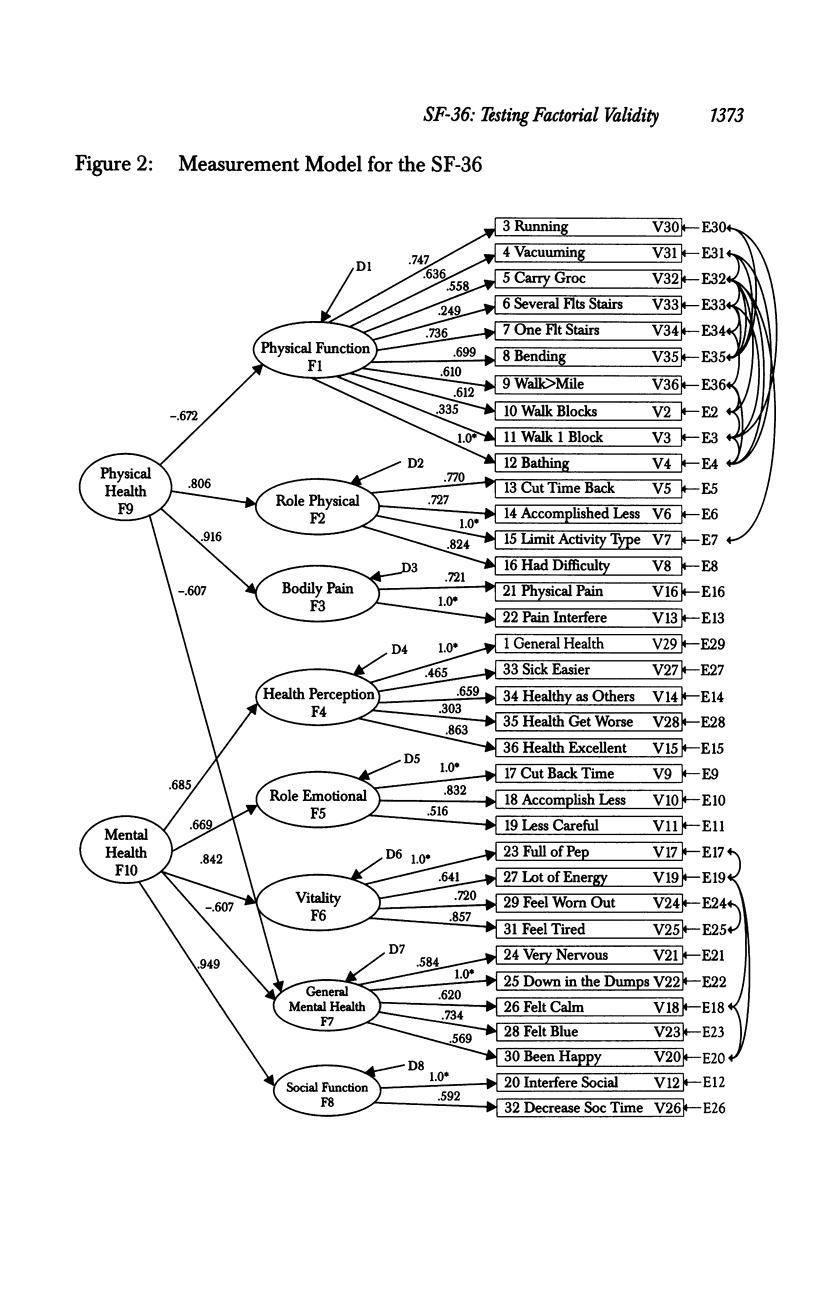

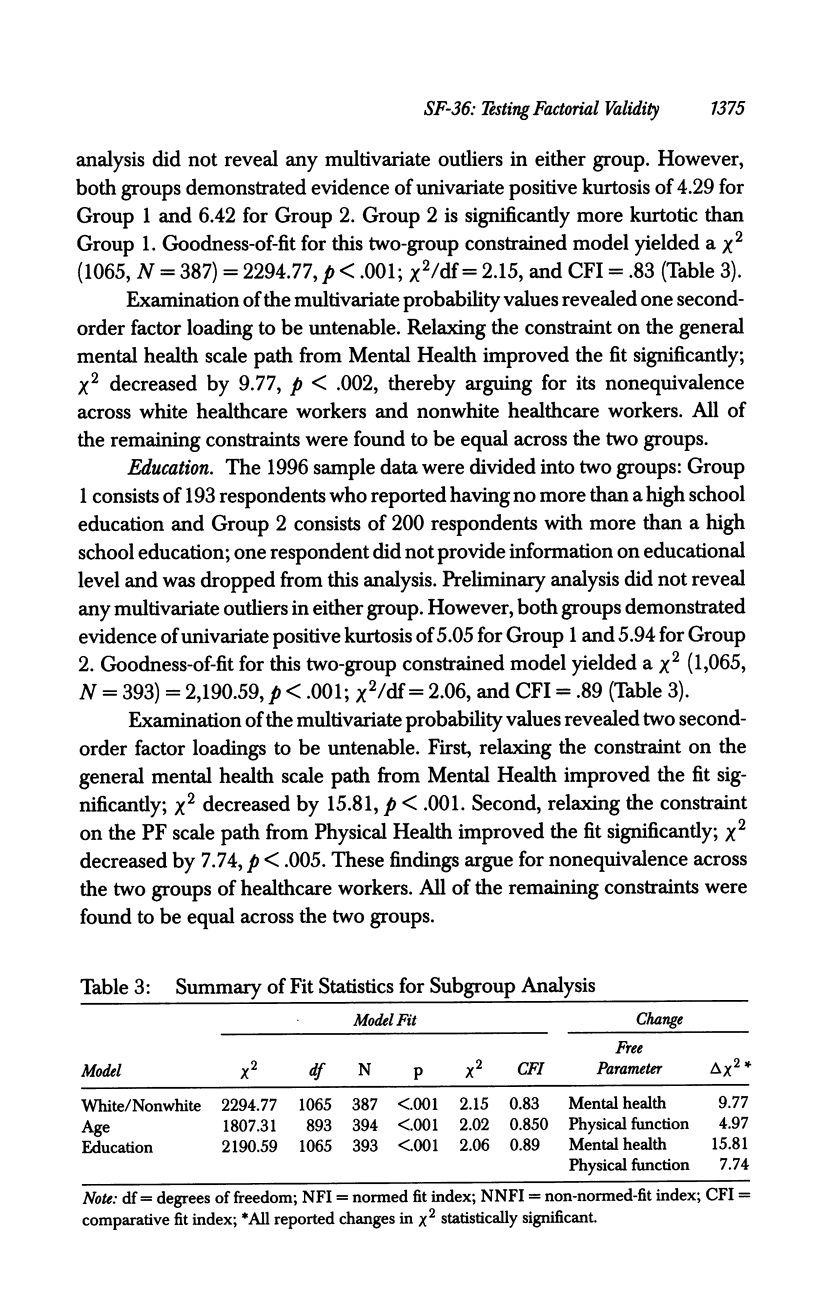

OBJECTIVE: To test the factorial validity of the SF-36. DATA SOURCE: Sample data collected in 1995 and 1996 using telephone interviews with health system employees as part of a study of health status. METHODS OF ANALYSIS: Confirmatory factor analysis and structural equation modeling techniques were used to evaluate the data. PRINCIPAL FINDINGS: The results of this study suggest that (1) Mental Health and Physical Health are not independent; (b) Mental Health cross-loads onto Physical Health; (c) general health loads onto Mental Health instead of Physical Health; (d) many of the error terms are correlated; (e) the physical function subscale is not reliable across the samples or the "age" or "education" subgroups; and (f) the mental health subscale path from Mental Health is not reliable across some subgroups. This hierarchical factor pattern was replicated across both samples. CONCLUSIONS: This study supports the second-order factorial structure of the SF-36. Adding the covariance path between the variables Physical Health and Mental Health improved model fit. Two paths from the second-order latent variables to the first-order latent variables differ from the original hypothesized structure of the SF-36. Health perception was influenced by Mental Health rather than Physical Health, and mental health was influenced by both Mental Health and Physical Health. This cross-loading suggests that the perception of Physical Health greatly affects mental health. Scale instabilities in the SF-36 across subgroups suggest that a comparison of mean scores or summary scores is inappropriate. Data interpretation can be improved if multigroups structural equation modeling is used.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bentler P. M. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol Bull. 1990 Mar;107(2):238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulton C. J., Hyduk C. M., Chow J. C. An assessment of the Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales in 3 ethnic groups. J Rheumatol. 1989 Aug;16(8):1110–1115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deyo R. A. Pitfalls in measuring the health status of Mexican Americans: comparative validity of the English and Spanish Sickness Impact Profile. Am J Public Health. 1984 Jun;74(6):569–573. doi: 10.2105/ajph.74.6.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L. T., Bentler P. M., Kano Y. Can test statistics in covariance structure analysis be trusted? Psychol Bull. 1992 Sep;112(2):351–362. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.2.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson P. A., Goldman L., Orav E. J., Garcia T., Pearson S. D., Lee T. H. Comparison of the Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form 36-Item Health Survey in black patients and white patients with acute chest pain. Med Care. 1995 Feb;33(2):145–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. M., Jay G. M. What do global self-rated health items measure? Med Care. 1994 Sep;32(9):930–942. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199409000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHorney C. A., Ware J. E., Jr, Lu J. F., Sherbourne C. D. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Med Care. 1994 Jan;32(1):40–66. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199401000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHorney C. A., Ware J. E., Jr, Raczek A. E. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993 Mar;31(3):247–263. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder S. A. Outcome assessment 70 years later: are we ready? N Engl J Med. 1987 Jan 15;316(3):160–162. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198701153160309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart A. L., Hays R. D., Ware J. E., Jr The MOS short-form general health survey. Reliability and validity in a patient population. Med Care. 1988 Jul;26(7):724–735. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198807000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware J. E., Jr, Kosinski M., Bayliss M. S., McHorney C. A., Rogers W. H., Raczek A. Comparison of methods for the scoring and statistical analysis of SF-36 health profile and summary measures: summary of results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Med Care. 1995 Apr;33(4 Suppl):AS264–AS279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware J. E., Jr, Sherbourne C. D. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992 Jun;30(6):473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D., Pennebaker J. W. Health complaints, stress, and distress: exploring the central role of negative affectivity. Psychol Rev. 1989 Apr;96(2):234–254. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.96.2.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolinsky F. D., Stump T. E. A measurement model of the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey in a clinical sample of disadvantaged, older, black, and white men and women. Med Care. 1996 Jun;34(6):537–548. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199606000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]