Abstract

Cells are exposed to a wide variety of internal and external stresses. Although many studies have focused on cellular responses to acute and severe stresses, little is known about how cellular systems adapt to sublethal chronic stresses. Using mammalian cells in culture, we discovered that they adapt to chronic mild stresses of up to two weeks, notably proteotoxic stresses such as heat, by increasing their size and translation, thereby scaling the amount of total protein. These adaptations render them more resilient to persistent and subsequent stresses. We demonstrate that Hsf1, well known for its role in acute stress responses, is required for the cell size increase, and that the molecular chaperone Hsp90 is essential for coupling the cell size increase to augmented translation. We term this translational reprogramming the ‘rewiring stress response’, and propose that this protective process of chronic stress adaptation contributes to the increase in size as cells get older, and that its failure promotes aging.

Research organism: Human

Introduction

Stress has shaped the interactions between organisms and their environment since the origin of the first cell (Kültz, 2020b). Throughout their lifetime, cells and organisms are exposed to different kinds of environmental and cell-intrinsic stresses such as heat, genotoxic agents, oxidative agents, alterations of external pH, hypoxia, nutrient deficiency, osmotic changes, protein misfolding and aggregation, and various pathological conditions (Kristensen et al., 2020). While intense acute stresses can cause lethal damage, in a physiological environment, cells are mostly exposed to mild and often chronic stresses, so that cells have a chance to adapt (Bijlsma and Loeschcke, 2005; Kültz, 2020a). For example, body or tissue temperature increases of only a few degrees constitute a mild heat stress at the cellular level (Mainster et al., 1970; Evans et al., 2015; van Norren and Vos, 2016; Baker et al., 2020; Rzechorzek et al., 2022). Similarly, the ecosystem may contain several pollutants that cause a continuous mild oxidative stress (Taborsky et al., 2021). Cells and organisms cannot easily escape such stresses and must therefore adapt.

Because cells and organisms need to live with such lifelong stresses, evolution has endowed them with highly conserved stress response pathways (Liu et al., 1997). Heat-shock factor 1 (Hsf1), a transcription factor, is the master regulator of cellular stress management (Li et al., 2017). Hsf1 governs a protective transcriptional program known as the heat-shock response (HSR), which involves the selective transcription of stress response proteins known as heat-shock proteins (Hsps), most of which are molecular chaperones (Lindquist and Craig, 1988; Richter et al., 2010; Vihervaara and Sistonen, 2014). Molecular chaperones collectively promote the initial folding of newly made proteins, the refolding of unfolded or misfolded proteins, the dissociation of protein aggregates, and the degradation of terminally misfolded or aggregated, and potentially toxic, proteins (Hartl et al., 2011). Overall, this process of maintaining protein homeostasis is known as proteostasis. During acute stress of different kinds, apart from the Hsf1-mediated transcriptional response, eukaryotic cells elicit a specific adaptive stress response, known as the integrated stress response (ISR). The ISR reprograms translation to avoid overloading the proteostasis system (Persson et al., 2020). In the ISR, global cap-dependent protein translation is reduced, while the translation of some proteins, needed to deal with the challenge, is specifically enhanced.

Hsps are not only required for cells to respond to stress. Even without stress, cells need a basal level of Hsps for folding nascent polypeptide chains, refolding partially denatured or misfolded proteins, or for their degradation (Balchin et al., 2016). Hsps are categorized into different families based on their molecular weights. Among those, Hsp90 is essential for the viability and growth of eukaryotic cells and organisms, and it is a major hub of cellular proteostasis through a large number of client proteins (Taipale et al., 2010; Echeverría et al., 2011; Johnson, 2012; Fierro-Monti et al., 2013; Bhattacharya et al., 2020; Bhattacharya and Picard, 2021). It is one of the most abundant proteins in cells (Nollen and Morimoto, 2002; Mollapour et al., 2010; Finka and Goloubinoff, 2013), and in mammals, a large fraction of it is indeed required during prenatal development, and for tissues and cells (Bhattacharya et al., 2022). In mammalian cells, there are two different cytosolic Hsp90 isoforms, which are encoded by two different genes, Hsp90α (encoded by the gene HSP90AA1) and Hsp90β (encoded by HSP90AB1) (Sreedhar et al., 2004). Hsp90α is the more stress-inducible isoform, whereas Hsp90β is more constitutively expressed. There are extensive overlapping functional similarities between the two Hsp90 isoforms, which are 84% identical in humans, but there is also some evidence for isoform-specific functions (Maiti and Picard, 2022). However, to what extent mammalian cells require these two isoforms during stress adaptation is not clear.

Cellular stress responses, molecular chaperones, and proteostasis are interconnected with cellular and organismal aging (Labbadia and Morimoto, 2015; Hipp et al., 2019; Bhattacharya and Picard, 2021). Although the process of aging is broadly influenced by genetic, epigenetic, and extrinsic factors, it is increasingly apparent that most of these factors ultimately interface with cellular stress response mechanisms (Kourtis and Tavernarakis, 2011; Vilchez et al., 2014; Lu et al., 2020). One of the hallmarks of aging is cellular senescence (Childs et al., 2015; McHugh and Gil, 2018; Calcinotto et al., 2019), which is characterized by a number of features, including a larger cell size. Earlier studies claimed that, as cells become senescent, they stop dividing. But since cell growth, defined as the addition of cell mass, continues, senescent cells become larger (Hayflick and Moorhead, 1961; Mitsui and Schneider, 1976; Adolphe et al., 1983; Yang et al., 2011). That is why cells of older mammalian indiviuals are often two or three times larger than those of younger ones (Cristofalo and Kritchevsky, 1969; Treton and Courtois, 1981; Demidenko and Blagosklonny, 2008; Mammoto et al., 2019). Remarkably, recent studies have established that a larger cell size is not a consequence, but rather the cause of senescence. If cells fail to scale the amount of their macromolecules as they become larger, this causes cytoplasmic dilution and induces senescence (Neurohr et al., 2019; Lanz et al., 2022). The question remains why mammalian cells increase their size to the point of becoming senescent. There are a number of indications that some cells increase their size in response to external cues or functional needs (Dhawan et al., 2007; Boehlke et al., 2010; Hall et al., 2012; Samak et al., 2016). However, it is poorly understood whether the cell size itself is the target of regulation or a byproduct of some other adaptation (Ginzberg et al., 2015).

Here, we report that mammalian cells gradually enlarge their size to adapt to chronic mild stress (or ‘chronic stress’ for short). Whereas the cellular response to acute stress has been extensively characterized (Richter et al., 2010; Somero, 2020), little is known about how cells adapt to chronic mild stress and to what extent certain Hsps or molecular chaperones are involved. We exposed cells to several chronic stresses to investigate these issues, notably also the role of specific cytosolic Hsp90 isoforms. We discovered that in response to chronic stress cells increase their size in an Hsf1-dependent fashion, and that their adaptation to chronic stress is different from the response to acute stress. Unlike acute stress, which causes a shutdown of global translation to reduce the protein burden, chronic stress induces global translation to increase the amount of total proteins. Hsp90, irrespective of its isoform, supports the increase in translation and, through this adaptation, the cell size increase.

Results

A mammalian cell model to study the effects of chronic mild stress

To study how mammalian cells adapt to chronic mild stress, we applied several stressors, such as mild heat shock (HS), hypoxia, the chemical stressor sodium arsenite, the protein misfolding agent L-azetidine-2-carboxylic acid (AZC), and tunicamycin (TM) as stressor of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), to several cell lines (Figure 1A, Figure 1—figure supplement 1A). To gage the level of chronic stress, which we would consider mild for a given stressor, we decided that it would be the duration or the intensity, where cell death is ≤10%. To determine the chronic mild HS conditions, we kept all cell lines at different temperatures for seven days. We found the threshold for chronic HS to be 39 °C for HEK293T (HEK) and HCT116 cancer cells, and 40 °C for A549 cancer cells and the normal epithelial cell line RPE1. For hypoxia, we determined that 4 days of hypoxia (1% oxygen) are the appropriate threshold for chronic hypoxic stress. For both sodium arsenite and AZC, 5 μM for 5 days is an appropriate threshold for oxidative and proteotoxic stresses, respectively. For TM, we established the optimal dose at 250 nM for 4–5 days. For all stress treatments, to exclude the additional stress and confounding effects of overcrowding, we optimized the seeding density and the size of the cell culture plate such that cells were never more than 70–75% confluent on the day of the analysis (Figure 1—figure supplement 1B) (see Materials and Methods for further details).

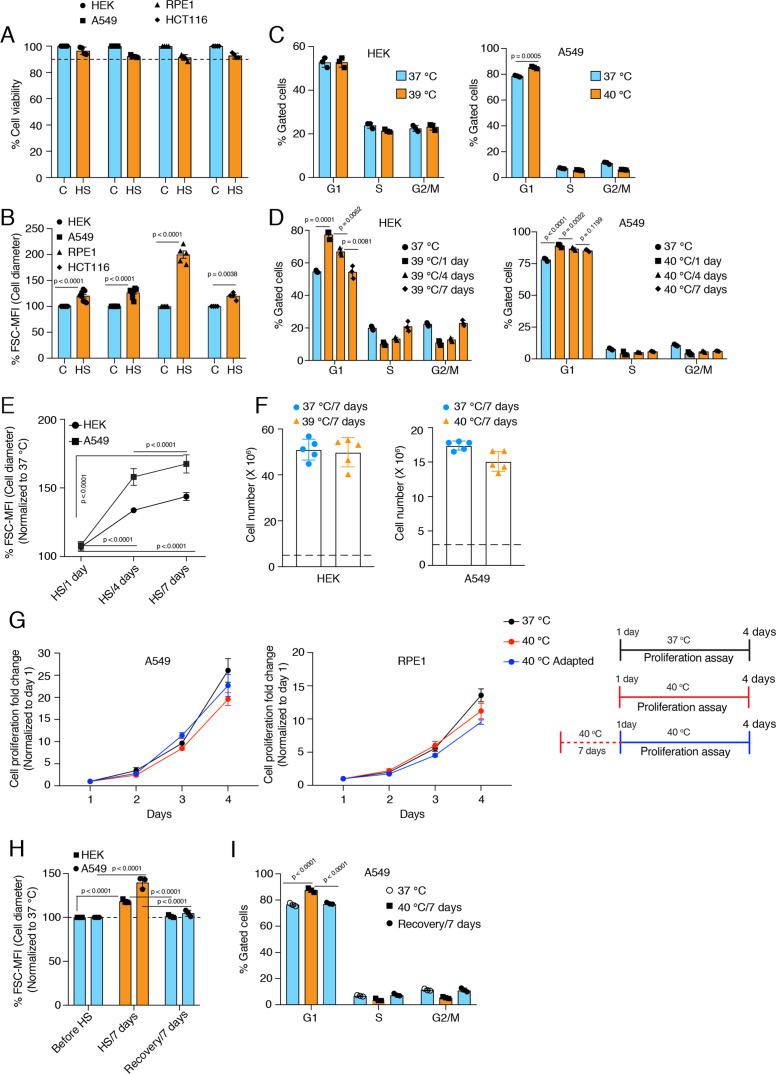

Figure 1. Cells increase their size in response to chronic stress.

(A) Flow cytometric quantification of cell viability under chronic HS for 7 days (HS = 39 °C for HEK and HCT116 cells; HS = 40 °C for A549 and RPE1 cells) (n = 4 biologically independent samples). (B) Flow cytometric quantification of cell size after 7 days of chronic HS (biologically independent samples: n = 6 for HEK and A549; n=5 for RPE1; n = 4 for HCT116). (C and D) Flow cytometric analysis of cell cycle (n=3 biologically independent samples). (E) Flow cytometric quantification of cell size during different time intervals of chronic HS (n=4 biologically independent samples). (F) Proliferation of HEK and A549 cells at the indicated temperature for the indicated period presented as cell numbers. Cells were seeded at a density of 5x106 and 3x106 per 15 cm plate for HEK and A549 cells, respectively. The numbers of live cells counted after 7 days are plotted (n=5 biologically independent experiments). (G) Proliferation of A549 and RPE1 cells measured with a crystal violet assay (n=3 biologically independent experiments). The adapted cells were maintained at 40 °C for 1 week before this experimental start point and continued at 40 °C during the experiment. See scheme of the experiment on the right. Note that the data are normalized to cell numbers on day 1. (H) Flow cytometric quantification of cell size in chronic HS and recovery (n=3 biologically independent samples). (I) Flow cytometric analysis of cell cycle in chronic HS and post HS recovery (n=3 biologically independent samples). The data are represented as mean values ± SEM for all bar and line graphs. The statistical significance between the groups was analyzed by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-tests.

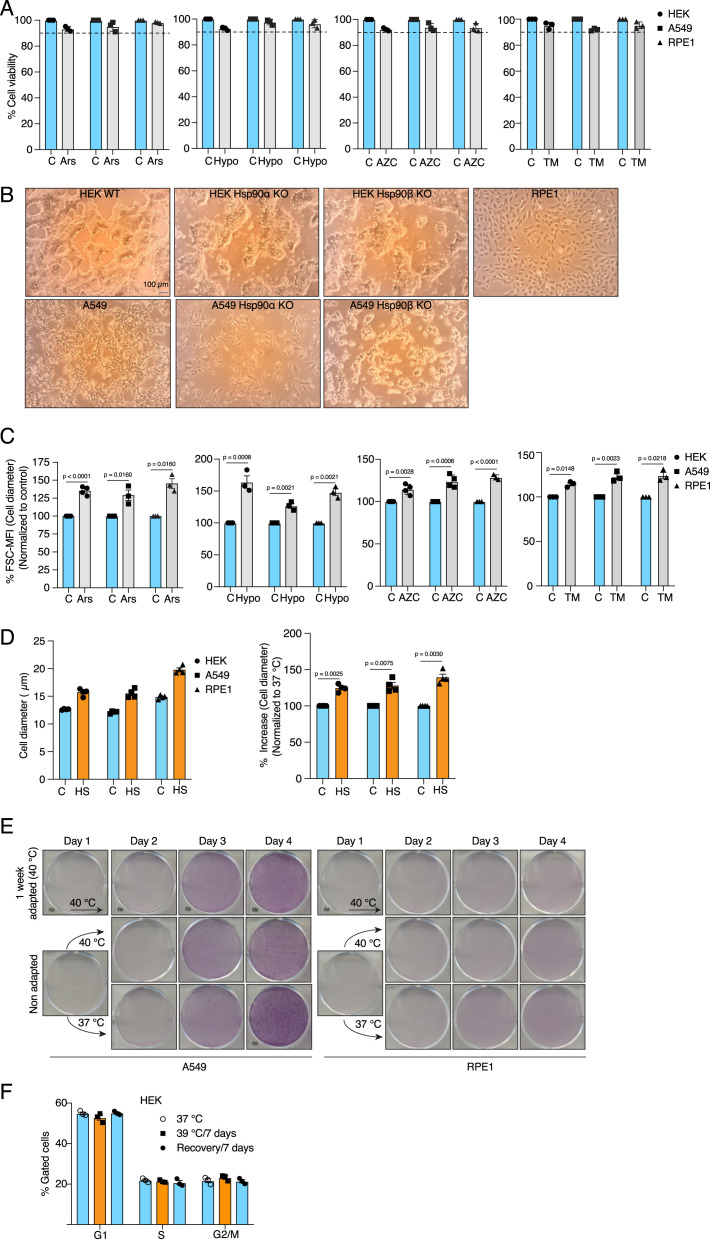

Figure 1—figure supplement 1. Cells increase their size in response to different types of chronic stress.

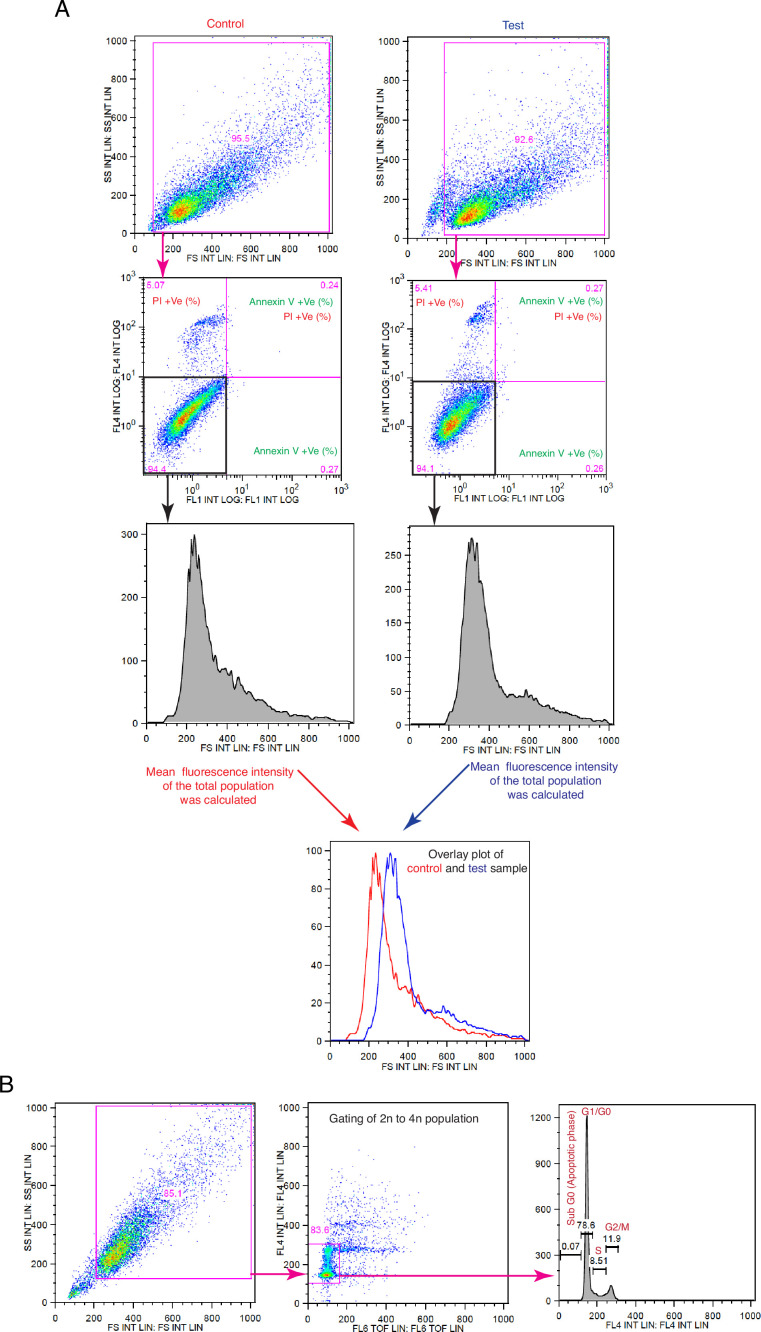

Figure 1—figure supplement 2. Schematic representation of the flow cytometric strategies for cell size and cell cycle analyses.

Chronic mild stress causes an increase in cell size

While we were checking cell death by flow cytometry to optimize the threshold for the different chronic stresses, we noticed that in all types of chronic stresses, cells increased their size over time (Figure 1B, Figure 1—figure supplement 1C), as indicated by the forward scatter (FSC) intensity, which is proportional to the diameter (d) of the cell (Tzur et al., 2011). Measuring the cell diameter by microscopy (Figure 1—figure supplement 1D) confirmed the size increase suggested by the FSC values after 7 days of mild HS. Even though FSC values cannot give absolute numbers, they allow relative changes to be determined and are a reasonable semi-quantitative proxy for cell diameter. Assuming cells in suspension are a round ball, note that a 10% increase in cell diameter translates to more than a 30% increase in cell volume since volume = (4/3) × π × (d/2)3. It is well supported that mammalian cells control their size via modulation of the cell cycle (Ginzberg et al., 2015; Miettinen et al., 2017; Varsano et al., 2017; Cadart et al., 2018). Specifically, a lengthening of the G1 phase is responsible for cell size increases. Hence, we determined whether this increase in cell size is caused by a cell cycle arrest. After seven days of chronic HS, we checked the cell cycle profiles of HEK and A549 cells (Figure 1C). Interestingly, the two cell lines showed different cell cycle patterns in chronic HS. While A549 cells have a slightly increased G1 population, HEK cells maintain a similar cell cycle profile. We repeated the analyses at different time points of chronic HS and found that at the initiation of chronic stress, there is a substantial number of cells in the G1 population for both cell lines (Figure 1D). Over time, the cell cycle stabilizes in a cell line-specific fashion, suggesting that cells are able to adapt to chronic HS. Importantly, despite the stabilization of the cell cycle during continued chronic stress, cells maintain an enlarged cell size (Figure 1E) with an almost equal proliferation rate (Figure 1F and G, Figure 1—figure supplement 1E) in the beginning of the stress or after 7 days of stress adaptation. Note that the proliferation rates confirm that our experimental conditions avoid overcrowding. To check if this cell size enlargement is reversible, we put the cells back at 37 °C after 7 days of chronic HS. During this recovery period at 37 °C, both HEK and A549 cells returned to their usual size (Figure 1H), and A549 cells also reverted back to a normal cell cycle profile (Figure 1I, Figure 1—figure supplement 1F).

A minimal level of Hsp90 is required for chronic stress adaptation

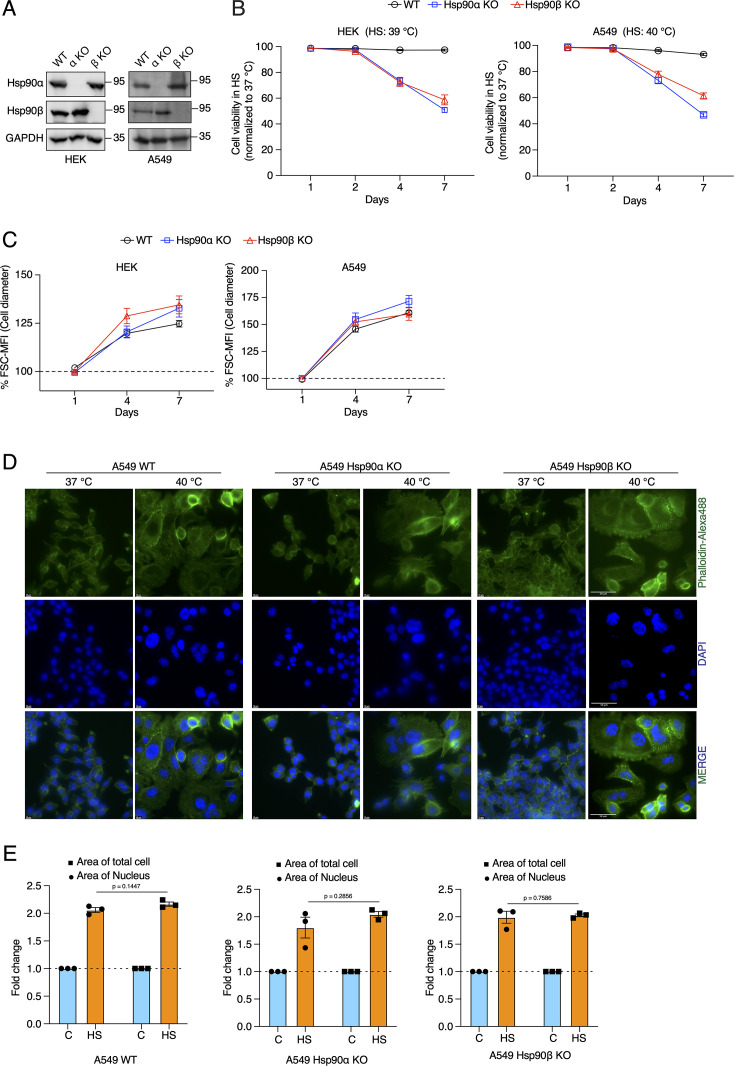

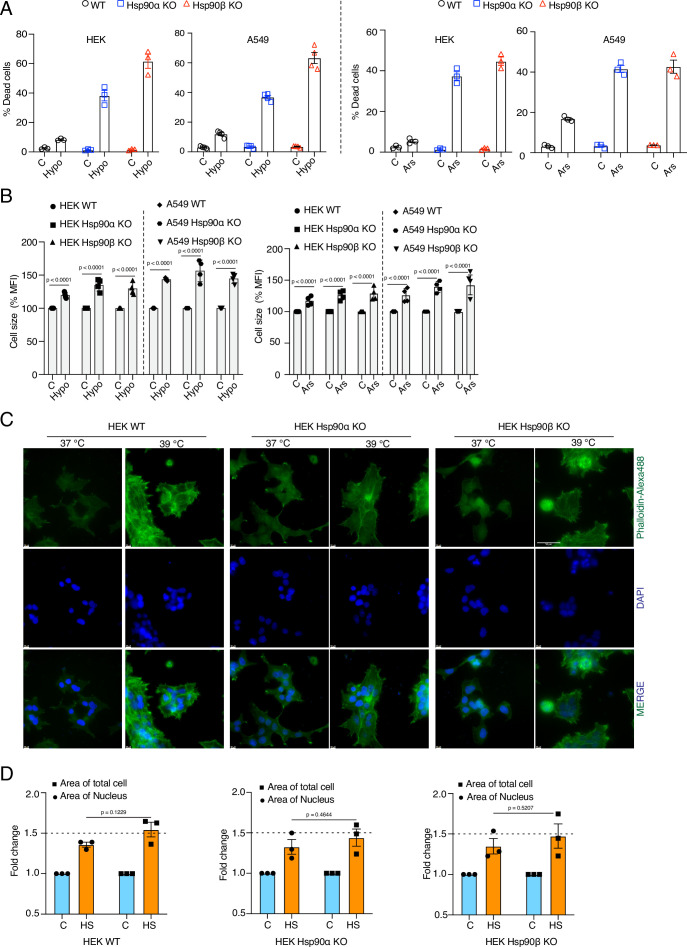

A key question is how cells cope with and adapt to these chronic stresses. A complex network of molecular chaperones and their respective co-chaperones acts as a buffer to the myriad of changes during stress (Bijlsma and Loeschcke, 2005; Richter et al., 2010; Horwich, 2014; Labbadia and Morimoto, 2015). The cytosolic Hsp90 isoforms are the most abundant molecular chaperones (Jakob and Buchner, 1994; Mayer and Bukau, 1999; Young et al., 2001; Picard, 2002). Since Hsp90 had been found to support the size increase of cardiomyocytes following myocardial infarction (Tamura et al., 2019), we wondered whether it plays any role in the stress-induced cell size increase, and if so, which one of the two cytosolic Hsp90 isoforms, that is Hsp90α or Hsp90β (Maiti and Picard, 2022). To address this, we used our human Hsp90α knockout (KO) and Hsp90β KO HEK and A549 cells (Figure 2A; Bhattacharya et al., 2022). Note that total Hsp90 levels are correspondingly reduced since there is very little compensation in expression of one isoform when the other one is absent (Bhattacharya et al., 2022), and that combined KOs of all cytosolic isoforms (two in humans) are not viable in eukaryotes. Hereafter we will refer to cells lacking one or the other isoform as Hsp90α/β KO cells. We observed that the loss of either one of the two isoforms makes them vulnerable to different chronic stresses (Figure 2B, Figure 2—figure supplement 1A), in contrast to what has recently been reported to happen with Hsp90α/β KO fibrosarcoma cells, which resist as well as wild-type (WT) cells to acute heat and oxidative stress (Petrenko et al., 2023). However, even in the absence of one Hsp90 isoform, cells enlarged their size during chronic HS, and hypoxic and oxidative stress conditions (Figure 2C and D, Figure 2—figure supplement 1B and C). This suggests that the stress-induced cell size increase is not directly associated with a particular cytosolic Hsp90 isoform. So far, we have only considered overall increases of cell size, but it is known that cell size increases are correlated with increases of the size of the nuclei (Wu et al., 2022 and therein). We therefore measured the size of nuclei and corresponding cell size increase. In this case, we fixed the cells, stained them for filamentous actin and DNA, and measured the areas of the attached cells and their nuclei. We found that both increase proportionately in cells subjected to chronic HS, and as for the total cell size, this is independent of a specific Hsp90 isoform (Figure 2E, Figure 2—figure supplement 1D).

Figure 2. Cells increase their overall size and their nuclei, but are unable to adapt to chronic HS in the absence of one of the cytosolic Hsp90 isoforms.

(A) Immunoblots of Hsp90α and Hsp90β in WT HEK and A549 cells, and their respective Hsp90α/β KO cells. GAPDH serves as the loading control (α KO; Hsp90α KO and β KO; Hsp90β KO) (representative images of n=4 biologically independent experiments). (B) Flow cytometric quantification of cell viability of HEK, A549, and their respective Hsp90α/β KO cells in chronic HS at different time points during a period of 7 days (n=5 biologically independent samples). Note that the X axis does not have a linear scale and that lines connecting the data points are drawn as a visual aid. (C) Flow cytometric quantification of cell size in chronic HS at different time points during a period of 7 days (HS = 39 °C for HEK and 40 °C for A549) (n=4 biologically independent samples) The data are represented as mean values ± SEM for all bar graphs. (D) Fluorescence microscopy images of A549 WT and Hsp90α/β KO cells fixed after 4 days of chronic HS. The cytoskeleton is stained with phalloidin-Alexa488 (green), and the nucleus is stained with DAPI (blue). Images were captured with a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Germany). The scale bars on the images in the far right column are 50 μM. (E) Bar graphs of the area of nuclei and whole cells determined from fluorescent micrographs (representative images are shown in panel D) using ImageJ. We used micrographs from three biologically independent experiments. From each experiment, we measured 30 randomly chosen cells, and their average values were used as one data point. The data for all bar graphs are represented as mean values ± SEM. The statistical significance between the groups was analyzed by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-tests.

Figure 2—figure supplement 1. Cells are unable to adapt to chronic stress in the absence of one of the Hsp90 isoforms, but still get larger.

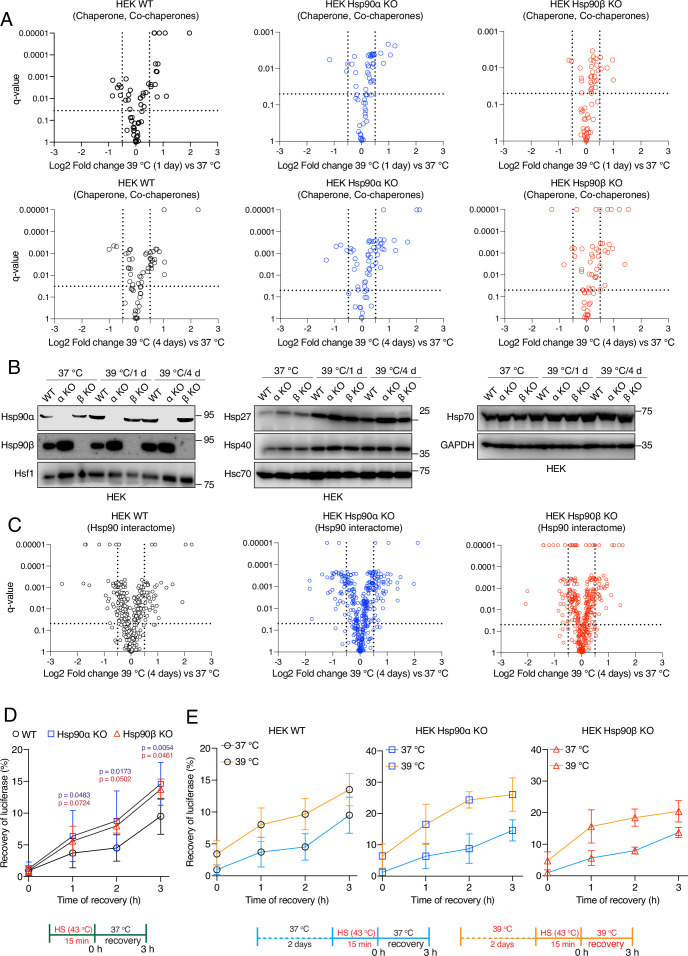

The canonical Hsf1 activity regulates the cell size increase in response to chronic stress

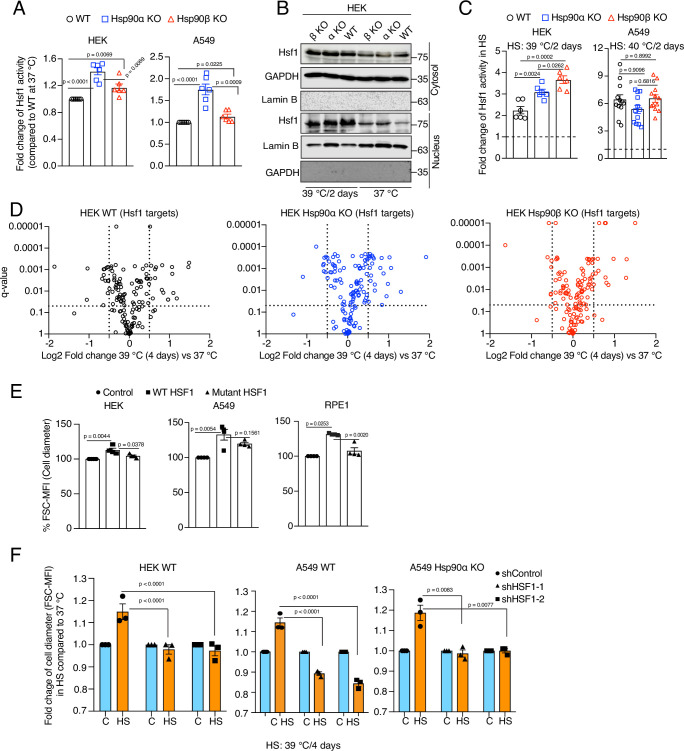

Hsf1 is an evolutionarily conserved transcription factor that mediates the cytoprotective HSR throughout the eukaryotic kingdom (Anckar and Sistonen, 2011; Gomez-Pastor et al., 2018). It is well established that Hsf1 activity increases in response to acute stresses (Li et al., 2017). During stress, mammalian Hsf1 monomers in the cytosol are activated to form trimers, which localize to the nucleus, bind DNA sequences known as heat shock elements (HSE), and trigger the transcription of target genes (Vihervaara and Sistonen, 2014). It has been proposed that Hsp90 controls Hsf1 activity by titrating Hsf1 under non-stress conditions (Zou et al., 1998; Leach et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2013; Hentze et al., 2016; Kijima et al., 2018). Using an Hsf1 reporter plasmid, we found that Hsp90α/β KO cells, and most prominently Hsp90α KO cells, have a higher basal level of Hsf1 activity (Figure 3A). In Hsp90α/β KO cells, the higher basal Hsf1 activity could be due to a larger number of Hsp90-free Hsf1 molecules. We did observe that there is more Hsf1 in the nucleus of Hsp90α/β KO HEK cells in non-stressed conditions (Figure 3B), and yet Hsf1 becomes even more nuclear in cells of all three genotypes during chronic HS (Figure 3B). This also translates to a higher Hsf1 activity, as we could observe with an Hsf1 reporter assay (Figure 3C). It is worth pointing out that there are substantial cell-line-specific differences of Hsf1 activity in chronic HS. While A549 cells of all three genotypes show a similarly strong increase, the Hsp90α/β KO HEK cells display significantly stronger stimulation of Hsf1 than WT HEK cells (Figure 3C). This suggests a tissue- or cell line-specific role of Hsp90 isoforms or total Hsp90 levels in regulating the Hsf1-mediated heat shock response. To characterize the proteomic changes associated with Hsp90α/β KO and chronic HS, we performed quantitative label-free proteomic analyses of cells maintained in non-stressed conditions, and after one day and four days of HS (Source data 1). The proteomic data confirmed the increased basal Hsf1 activity that we had seen in Hsp90α/β KO cells with the Hsf1 reporter assay. Many proteins whose expression was known to be regulated by Hsf1 proved to be upregulated in Hsp90α/β KO cells (Figure 3—figure supplement 1A and Source data 1). Under chronic HS, cells of all three genotypes were able to increase the expression of several Hsf1 target genes (Figure 3D), reminiscent of what we had seen with the Hsf1 reporter assay. Thus, cells are perfectly capable of mounting a HSR in the absence of either one of the two Hsp90 isoforms, suggesting that their increased vulnerability to stress may be due to something else.

Figure 3. Hsf1 regulates cell size in response to stress.

(A) Fold change of Hsf1 activity of HEK WT, A549 WT, and their respective Hsp90α/β KO cells at 37 °C as measured by luciferase reporter assay (n=3 biologically independent samples and 2 experimental replicates each time). (B) Immunoblots of Hsf1 in the cytosolic and nuclear fractions of HEK WT and Hsp90α/β KO cells (α KO, Hsp90αKO; β KO, Hsp90βKO). GAPDH and lamin B1 serve as loading controls (representative blots of n=2 biologically independent experiments). (C) Fold change of Hsf1 activity of HEK WT, A549 WT, and their respective Hsp90α/β KO cells in chronic HS as measured by luciferase reporter assay (n=3 biologically independent samples, and 2 experimental replicates each time for HEK; n=3 biologically independent samples, and 4 experimental replicates each time for A549). (D) Volcano plots of the normalized fold changes in protein levels of some core Hsf1 target genes (list obtained from https://hsf1base.org/) in chronic HS, determined by quantitative label-free proteomic analysis of Hsp90α/β KO and WT HEK cells. Molecular chaperones, whose expression is regulated by Hsf1, are excluded from this dataset. Each genotype was compared with its respective 37 °C control (n=3 biologically independent samples). Log2 fold changes of >0.5 or <–0.5 with q-values (adjusted p-values) of <0.05 were considered significant differences for a particular protein. (E) Flow cytometric quantification of cell size of HEK, A549, and RPE1 cells upon overexpression of WT Hsf1 (with plasmid pcDNA-Flag HSF1 wt) or mutant Hsf1 (with plasmid pcDNA-Flag HSF1 C205; retaining only the first 205 amino acids)(Kijima et al., 2018), and with plasmid pcDNA3.1(+) as empty vector control. Transfected cells to be measured were identified on the basis of their coexpression of EGFP (n=4 biologically independent experiments). (F) Flow cytometric quantification of cell size in chronic HS after knockdown of Hsf1 in HEK WT, A549 WT and Hsp90αKO cells. Here the chronic HS for A549 cells is at 39 °C instead of 40 °C to reduce HS-induced damage in Hsf1 knockdown conditions (n=3 biologically independent samples). For all bar graphs, the statistical significance between the groups was analyzed by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-tests.

Figure 3—figure supplement 1. Hsf1 induces cell size in response to stress.

To obtain more direct experimental evidence for a role of Hsf1 in the cell size increase induced by chronic HS, we overexpressed WT Hsf1 and a transcriptionally defective Hsf1 mutant (Kijima et al., 2018) in HEK, A549, and RPE1 cells. We observed a strong induction of basal Hsf1 activity in cells overexpressing WT Hsf1 but not the mutant form (Figure 3—figure supplement 1B), correlating with an increase in cell size under normal non-stress conditions (Figure 3E). Taken together, our observations suggest a correlation between the canonical transcriptional Hsf1 activity and cell size. We further strengthened this correlation by determining the effect of inducing Hsf1 activity pharmacologically with capsaicin, which is known to trigger a calcium influx and HSR through the vanilloid receptor TRPV1 (Hagenacker et al., 2005; Bromberg et al., 2013). We found that A549 cells of all three genotypes display a capsaicin-induced and dose-dependent transcriptional Hsf1 activity (Figure 3—figure supplement 1C) and cell size increase (Figure 3—figure supplement 1D). Collectively, these results indicate that the transcriptional Hsf1 activity is sufficient to cause a cell size increase. To determine whether Hsf1 is necessary for the cell size increase, we used RNA interference to knock down Hsf1 expression in HEK WT, A549 WT, and Hsp90α KO cells (Figure 3—figure supplement 1E). Hsf1 knockdown cells exposed to chronic HS failed to induce Hsf1 activity (Figure 3—figure supplement 1F), and could not increase their cell size during adaptation to chronic HS (Figure 3F).

So far, we have only shown results obtained with established human cell lines. We also explored the link between Hsp90 and Hsf1 activity in mouse adult fibroblasts (MAFs) established from mice with only a single allele for cytosolic Hsp90 left. These are both homozygous hsp90α KO and heterozygous hsp90β KO, and will be referred to as 90αKO 90βHET (Bhattacharya et al., 2022). These MAFs proved to be substantially bigger than WT MAFs (Figure 3—figure supplement 1G), and to display a several-fold higher basal Hsf1 activity (Figure 3—figure supplement 1H). It should be emphasized that these MAFs were obtained from adult mice that had escaped the stringent developmental attrition of embryos with this genotype through translational reprogramming of Hsp90β expression (Bhattacharya et al., 2022). This may explain why these mutant MAFs, unlike WT MAFs, could not augment their Hsf1 activity nor increase their size any further in chronic HS (Figure 3—figure supplement 1I and J). At this point, we conclude that the HSR correlates with cell size during chronic stress, and that both outcomes are mediated by Hsf1.

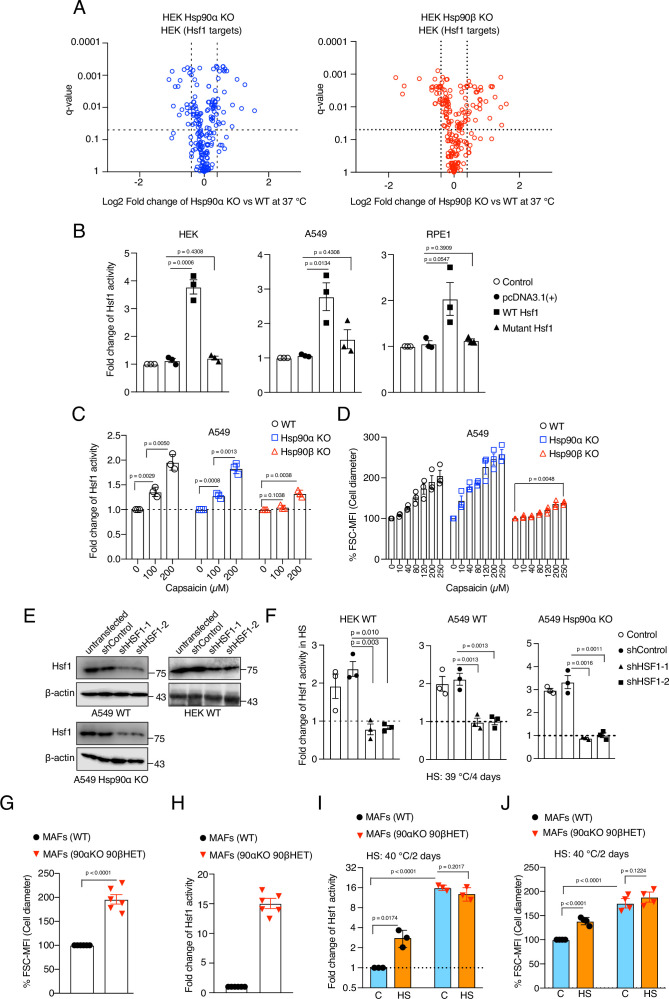

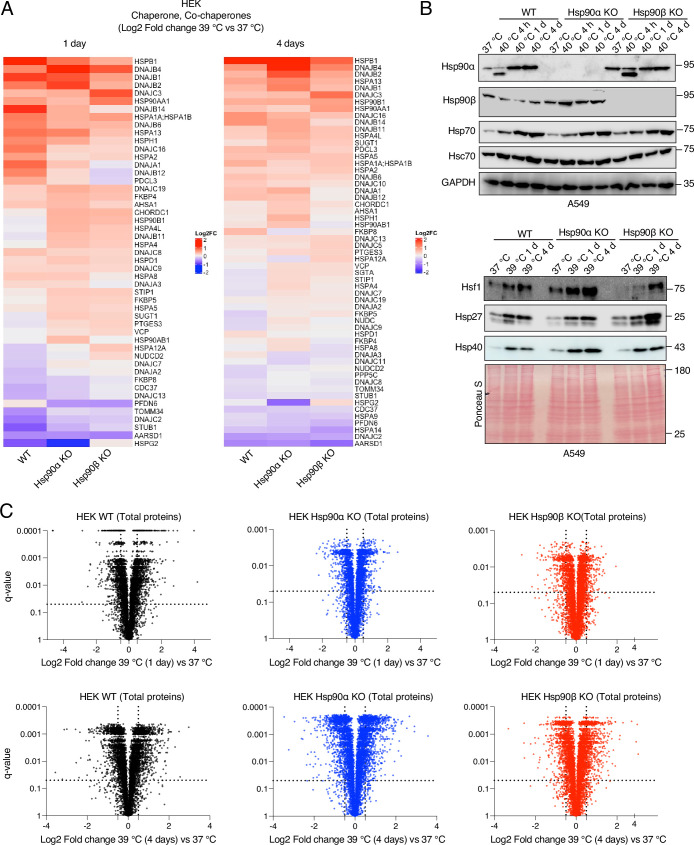

Hsp90α/β KO cells overall maintain their chaperome and proteome complexity during chronic stress

Under normal physiological conditions, cells maintain proteostasis through a complex network of molecular chaperones and co-chaperones, a protein collective referred to as the cellular chaperome (Joshi et al., 2018; Yan et al., 2020). Cellular adaptation to stress does not only require increased Hsf1 activity, but it is also modulated by complex functional relationships between Hsf1 and the cellular chaperome (Li et al., 2017). Even though the HSR in chronic stress is not impaired by the loss of one of the Hsp90 isoforms, Hsp90α/β KO cells gradually die off during the chronic HS adaptation period (Figure 2B). This raises the question whether the chaperome is compromised in the absence of Hsp90α or β. Using the proteomic data sets mentioned above, we focused on the protein levels of all molecular chaperones and co-chaperones at 37 °C and in chronic HS at different time points. This analysis revealed that Hsp90α/β KO cells could still maintain or increase expression of molecular chaperones and co-chaperones during chronic HS similarly to WT cells (Figure 4A, Figure 4—figure supplement 1A). Immunoblots confirmed the upregulation of the heat-inducible molecular chaperones Hsp90α (in some instances also Hsp90β), Hsp70, Hsp40, and Hsp27 throughout the chronic stress in cells of all three genotypes (Figure 4B, Figure 4—figure supplement 1B). This suggests that the chaperome of Hsp90α/β KO cells is not compromised by chronic stress. Similarly, at the whole proteome level, standardized to the same amount of protein, and although there are genotype-specific differences, the proteome remained complex during chronic stress indicating that proteostasis was largely intact (Figure 4—figure supplement 1C). Next, we analyzed the Hsp90 interactome. We found that the Hsp90α or Hsp90β KO cells could largely maintain the Hsp90 interactors throughout the chronic stress. These data demonstrate that one Hsp90 isoform is sufficient to support most interactors (Figure 4C, Figure 4—figure supplement 2). We conclude from these proteomic analyses that there are no major genotype-specific global changes in levels of chaperones and Hsp90 interactors of cells exposed to chronic HS, but there are some genotype-specific differences that might be worth investigating further in the future.

Figure 4. Hsp90α/β KO cells maintain chaperones, co-chaperones, and Hsp90 interactors during chronic stress adaptation.

(A) Volcano plots of the normalized fold changes of molecular chaperones and co-chaperones after 1 and 4 days (first and second rows, respectively) of chronic HS determined by quantitative label-free proteomic analyses of Hsp90α/β KO and WT HEK cells. Each genotype was compared with its respective 37 °C control (n=3 biologically independent samples). Log2 fold changes of >0.5 or <–0.5 with q-values (adjusted p-values) of <0.05 (indicated as stippled lines) were considered significant differences for a particular protein. (B) Immunoblots of different molecular chaperones in HEK WT and Hsp90α/β KO cells (α KO, Hsp90αKO; β KO, Hsp90βKO). GAPDH serves as the loading control for all three panels (representative of n=2 independent experiments). (C) Volcano plots of the normalized fold changes of the Hsp90 interactors (list obtained from https://www.picard.ch/Hsp90Int) after 4 days of chronic HS determined by quantitative label-free proteomic analyses of Hsp90α/β KO and WT HEK cells. Each genotype was compared with its respective 37 °C control (n=3 biologically independent samples). (D and E) In vivo refolding of heat-denatured luciferase of control cells (blue line) and cells heat-adapted to 39 °C (orange line). Luciferase activity before the acute HS (at 43 °C) is set to 100% (n=3 biologically independent samples). See scheme of the experiment below. Note the different scales of the Y axes of the bar graphs in panel E. The data are represented as mean values ± SEM for all bar graphs. The statistical significance between the groups was analyzed by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-tests. The p-values for Hsp90α and Hsp90β KO cells are in blue and red, respectively. All p-values are for comparisons to the respective WT.

Figure 4—figure supplement 1. Hsp90α/β KO cells maintain molecular chaperones, co-chaperones, and total proteins.

Figure 4—figure supplement 2. Hsp90α/β KO cells maintain Hsp90 interactors in chronic stress.

To address the protein folding ability of Hsp90α/β KO cells more directly, we performed an in vivo refolding assay with exogenously expressed firefly luciferase subjected to unfolding by a short HS at 43 °C. We found that Hsp90α/β KO cells do even better than WT cells under basal conditions (37 ° C; Figure 4D). The KO cells also showed an increased luciferase refolding ability when they were cultured for 2 days at 39 °C prior to luciferase unfolding (Figure 4E). This higher refolding activity of the Hsp90α/β KO cells at 37 ° C might be due to the elevated basal activity of Hsf1 (see above) driving higher expression of some other molecular chaperones compared to WT cells (Figure 4B). Similarly, Hsp90α/β KO cells might do better than WT cells when subjected to a mild HS for 2 days because of their ability to further increase the levels of other molecular chaperones, such as Hsp27, Hsp40, and Hsp70, during chronic HS. So far, these observations suggest that a reduced level of Hsp90 is at least in part functionally compensated by other molecular chaperones in these assays.

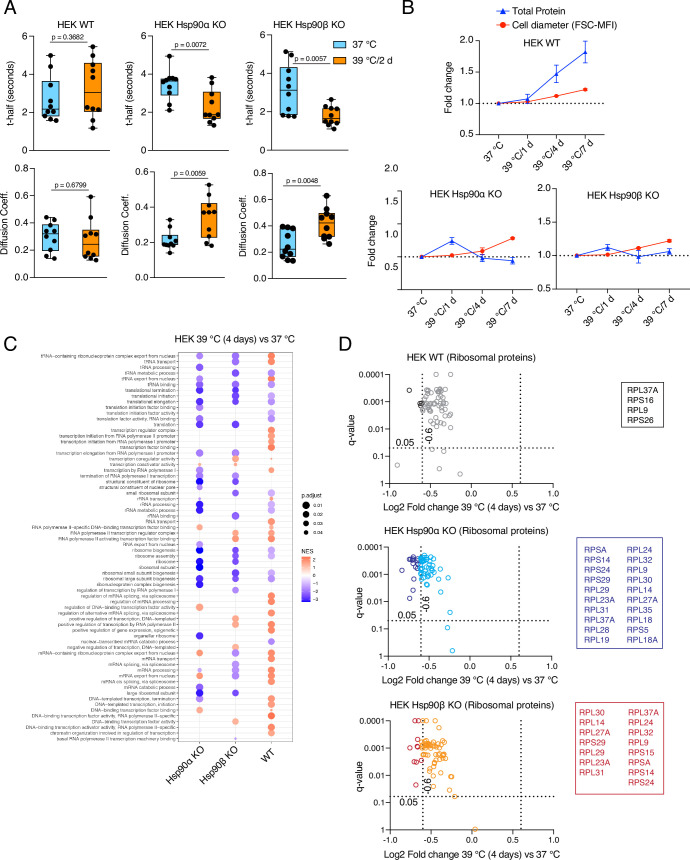

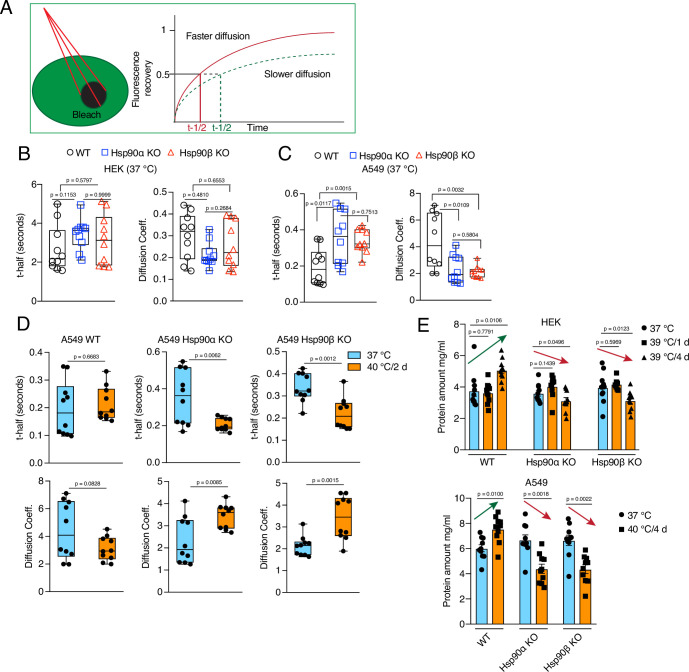

A normal level of Hsp90 is required to maintain the cytoplasmic protein density in chronic stress

If Hsp90α/β KO cells do as well or even better than WT cells for almost all parameters investigated so far, what causes them to be more sensitive to stress (Figure 2B)? Water accounts for about 70% of the weight of a typical cell, with proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, and polysaccharides contributing most of the remaining mass. The largest contribution to cellular dry mass is typically from proteins, followed by nucleic acids and lipids. It is known that when cells grow larger, they must maintain all macromolecules at proportionate levels (Lloyd, 2013; Kempe et al., 2015; Lin and Amir, 2018; Berenson et al., 2019; Lanz et al., 2022; Miettinen et al., 2022). To achieve this for proteins, cells need to increase the total amount of proteins proportionately to their size increase, a process that can be referred to as scaling. Uncoupling of protein synthesis and cellular volume, for example in excessively large cells, causes a dilution of the cytoplasm, which results in cellular senescence and aging (Neurohr et al., 2019).

We tested cytoplasmic density by measuring the mobility of EGFP in vivo using fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) experiments (Figure 5—figure supplement 1A). We calculated the t-half values and diffusion rates (Persson et al., 2020), and found that only WT cells could maintain the same cytoplasmic density under chronic HS as at 37 °C (Figure 5A, Figure 5—figure supplement 1B–D). Hsp90α/β KO cells of both cell lines showed lower t-half values and higher diffusion coefficients in chronic stress indicating that they have a reduced cytoplasmic density (Figure 5A, Figure 5—figure supplement 1B–D). This observation suggests that a full complement of cytosolic Hsp90 is necessary to maintain the cytoplasmic density with the increase of cell size in chronic stress. There is no significant difference between Hsp90α/β KO cells, which indicates that total Hsp90 levels rather than a specific isoform are critical for maintaining the cytoplasmic density.

Figure 5. Hsp90α/β KO cells suffer from cytoplasmic protein dilution during adaptation to chronic stress.

(A) FRAP experiments with control and heat-adapted live cells expressing EGFP. The respective box plots show the t-half values of recovery of EGFP fluorescence and the apparent EGFP diffusion coefficients (n=10 cells from two biologically independent experiments). The statistical significance between the groups was analyzed by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-tests. (B) Fold change of cell size (represented by the FSC-MFI values) and total proteins (determined as MFI-FL1 values) in chronic HS as analyzed by flow cytometry. Cells were fixed, and total proteins were stained using Alexa Fluor 488 NHS ester (n=3 biologically independent experiments). Lines connecting the data points are drawn as a visual aid. (C) GSEA plot showing the up- or down-regulation (red and blue, respectively) of pathways associated with cellular transcription and translation after 4 days of chronic HS compared to the respective 37 °C controls; NES, normalized enrichment score. (D) Volcano plots of the normalized fold changes of the ribosomal proteins (list obtained from http://ribosome.med.miyazaki-u.ac.jp/) after 4 days of chronic HS determined by quantitative label-free proteomic analysis in Hsp90α/β KO and WT HEK cells. Each genotype was compared with its respective 37 °C control (n=3 biologically independent samples). Log2 fold changes of >0.6 or <–0.6 with q-values (adjusted p-values) of <0.05 (indicated as stippled lines) were considered significant differences for a particular protein. The boxes beside the volcano plots list the corresponding proteins that were significantly downregulated.

Figure 5—figure supplement 1. Wild-type cells maintain cytoplasmic density and total protein ratio during stress-induced cell size increase.

If the cytosol is more diluted, this should be reflected in the total amount of proteins. Therefore, we collected the same number of non-stressed and stressed enlarged cells after 1 day and 4 days of chronic HS, lysed them in the same amount of lysis buffer, and measured the protein concentrations in the lysates. We found that after 4 days of chronic stress, the total amount of proteins was higher in WT cells, whereas it decreased in Hsp90α/β KO cells (Figure 5—figure supplement 1E). Quantitation by flow cytometric analysis of total cellular protein stained with an amine-reactive dye revealed qualitatively similar results. The total amount of proteins per cell increased with cell size in WT but not in Hsp90α/β KO cells (Figure 5B, Figure 5—figure supplement 1E). These results demonstrate that cells are unable to maintain the ratio of total protein to cell size in chronic stress when Hsp90 levels are reduced.

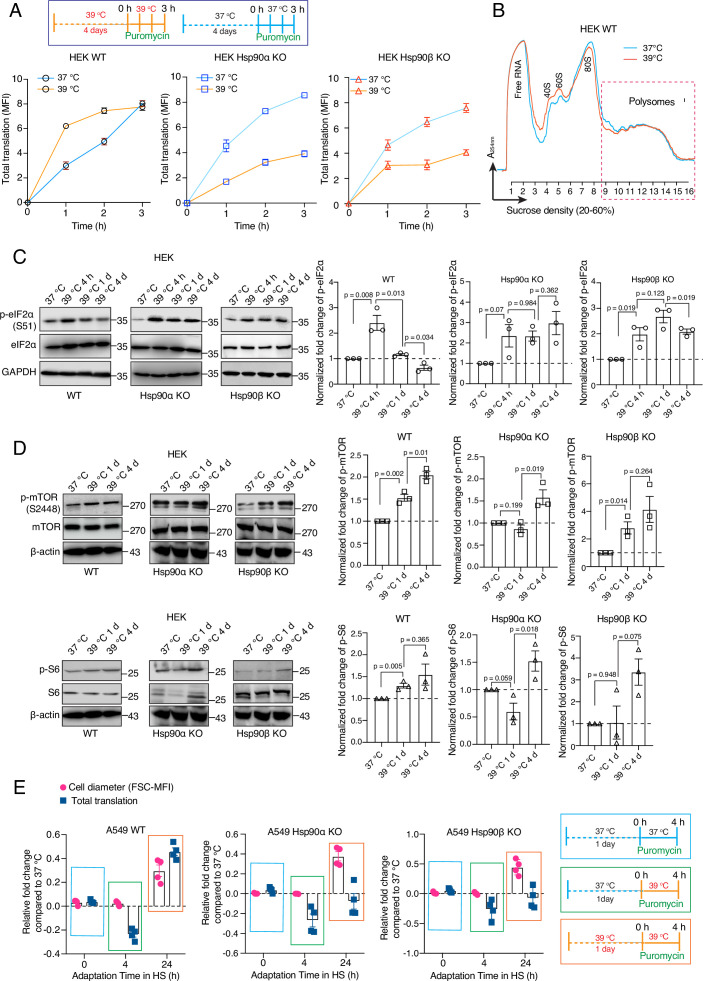

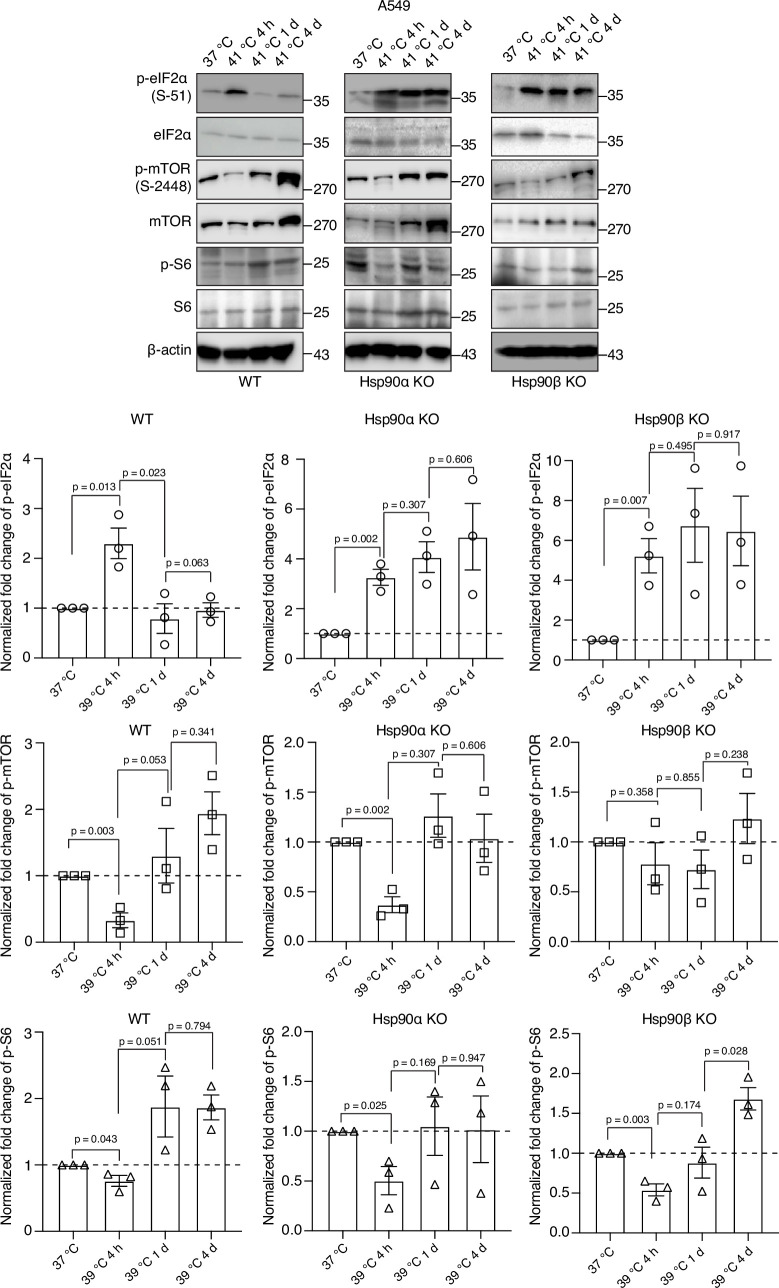

Normal levels of Hsp90 are required to scale protein biosynthesis during stress-induced cell size enlargement

One of the key features of the acute stress response of mammalian cells is a global inhibition of translation (Liu et al., 2013; Shalgi et al., 2013; Advani and Ivanov, 2019; Jobava et al., 2021). We demonstrated here that WT cells exposed to chronic stress increase the total amount of proteins as they get larger, raising the question of how they do it. Revisiting our proteomic data set, we performed a gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) and used an output list of enriched gene ontology (GO) terms focused on the pathways related to transcription and translation. Although even WT cells appear to have some deficits associated with the protein translation machinery, Hsp90α/β KO cells are more severely affected (Figure 5C). For example, the levels of ribosomal proteins are reduced the least in WT compared to Hsp90α/β KO cells under chronic stress (Figure 5D). A reduction of the core machinery of translation may explain why Hsp90α/β KO cells have decreased amounts of total proteins compared to WT in chronic stress. However, it does not explain the observation of the increased amount of total proteins in WT cells under chronic stress. To address this issue, we checked global translation by labelling nascent polypeptide chains with a fluorescent version of puromycin, which allows measurements for individual cells by flow cytometry. We saw a strong increase of labelled nascent polypeptides in WT HEK cells both on day 1 (Figure 6—figure supplement 1A) and day 4 (Figure 6A) of adaptation to chronic HS. By comparison, Hsp90α/β KO HEK cells failed to maintain the same rate of protein biosynthesis under chronic HS (Figure 6A, Figure 6—figure supplement 1A). While the stress-adapted bigger cells have a higher level of total translation (Figure 6A), it is known that acute HS causes ribosomal pausing of translating mRNAs (Shalgi et al., 2013). Polysome profiling of WT cells adapted to stress for four days showed that the polysome profiles of cells grown at 37 °C or in chronic HS are largely similar (Figure 6B). Similar peaks of single ribosomal particles (40 S and 60 S), monosomes (80 S), and polysomes (both small and large) suggest that the association of ribosomes and mRNAs in WT cells is not affected during adaptation to chronic stress. This raises the question of whether the ISR is not triggered when the stress is chronic. To address this, we did puromycin labeling at earlier time points of chronic HS. We observed that at the beginning of chronic stress (4 hr), reminiscent of the ISR (Persson et al., 2020), translation is reduced as seen by flow cytometry (Figure 6—figure supplement 1B) and puromycin labelling of nascent chains detected by immunoblotting (Figure 6—figure supplement 1C). Moreover, both HEK and A549 cells of all three genotypes displayed an increased inhibitory phosphorylation of the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 A (eIF2α), a hallmark of the ISR (Pakos-Zebrucka et al., 2016; Wek, 2018), after 4 hr of HS (Figure 6C, Figure 6—figure supplement 2). After having been exposed to chronic HS for one day and more, WT cells increase total translation, to an even higher level than the basal translation at 37 °C (Figure 6—figure supplement 1B), consistent with the higher translation rate observed by puromycin labeling of nascent chains (Figure 6A, Figure 6—figure supplement 1A). As cells remained in chronic HS, the phosphorylation of eIF2α only dropped in WT but not Hsp90α/β KO cells (Figure 6C, Figure 6—figure supplement 2). These findings indicate that at the very beginning of chronic HS, an ISR is induced with the accompanying inhibitory phosphorylation of eIF2α and global reduction of translation. WT cells but not Hsp90α/β KO cells, once adapted to the stress, recover normal or even increased global translation. Translational recovery of WT cells is also reflected in several other translation markers and regulators. After an initial drop in some cases, we could see an increase in the phosphorylation of mTOR and S6 during adaptation to chronic HS (Figure 6D, Figure 6—figure supplement 2), consistent with earlier reports demonstrating increased phosphorylation mTOR and S6 upon stress (Kakigi et al., 2011; Yoshihara et al., 2013; Gao et al., 2015). In our case, after 4 days of chronic HS, even Hsp90α/β KO cells displayed an increase in mTOR and S6 phosphorylation, suggesting that eIF2α dephosphorylation may constitute a critical (or perhaps the critical) and Hsp90-dependent aspect of stress adaptation.

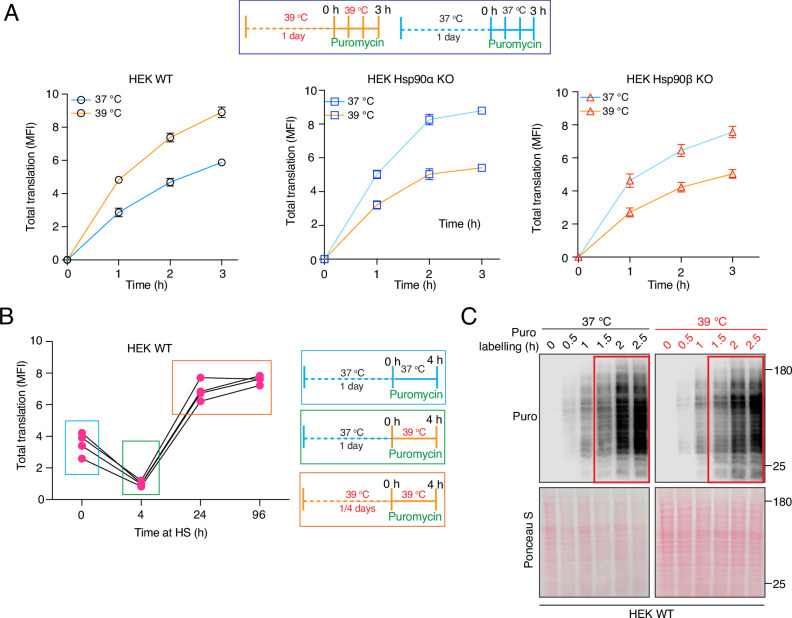

Figure 6. Hsp90 is crucial for adapting translation to chronic stress.

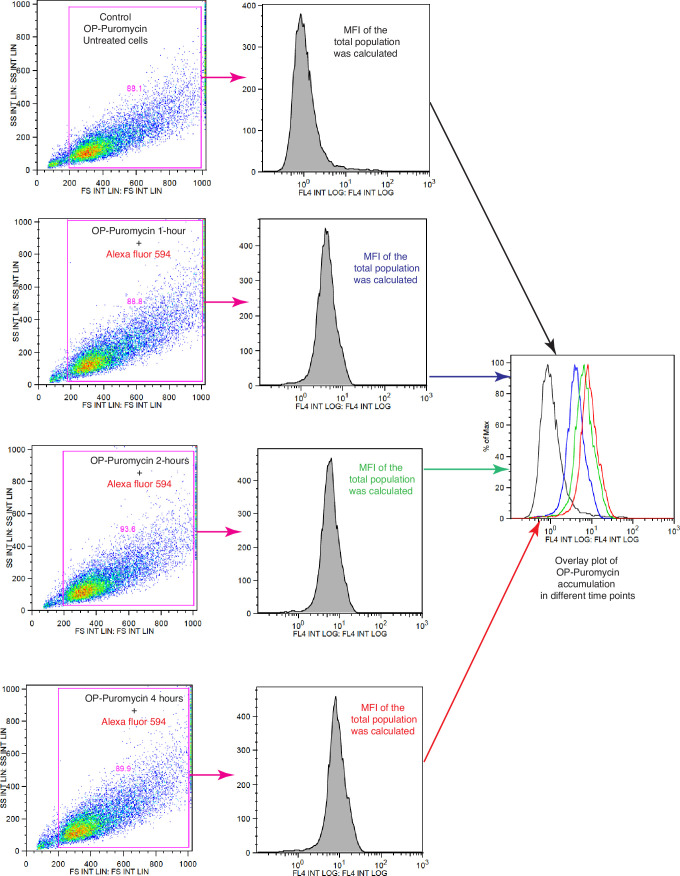

(A) Flow cytometric analysis of total translation of HEK WT and Hsp90α/β KO cells at 37 °C and after 4 days of chronic HS (see scheme of the experiment on the top). Nascent polypeptide chains were labeled with OP-puromycin during cell culture, and the incorporation of puromycin at different time points was analyzed (n=4 experimental samples). (B) Representative polysome profiles of HEK WT cells at 37 °C and after 4 days of chronic HS (representative of n=2 biologically independent experiments). (C and D) Immunoblots of the translation-related proteins eIF2α, mTOR, and S6. GAPDH and β-actin serve as loading controls. Note that the same β-actin immunoblot is used twice as internal loading control since the other immunoblots of panel D are from the same experiment. Representative immunoblots are shown, but the corresponding bar graphs on the right are based on the quantitation of three biological replicates. Values were normalized to the loading controls, and the phosphoproteins were normalized to their respective total protein. (E) Relative fold changes of total translation and cell size in the early phase of adaptation to chronic HS (see schemes of experiments on the right) for A549 WT and Hsp90α/β KO cells. The data are represented as mean values ± SEM for all bar graphs. The statistical significance between the groups was analyzed by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-tests.

Figure 6—figure supplement 1. Hsp90 requirement for cellular translation during adaptation to chronic stress, and early time points of translational adaptation of wild-type cells.

Figure 6—figure supplement 2. Differential effects of Hsp90 levels on eIF2α, mTOR, and S6.

Figure 6—figure supplement 3. Schematic representation of the flow cytometric strategies to measure translation.

The mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) is known to regulate cell size by regulating cellular translation (Fingar et al., 2002). Hsf1 in a non-transcriptional mode has been linked to regulating organ and cell size by preserving mTORC1 activity (Su et al., 2016). And yet, we saw that Hsp90α/β KO cells increase their size in chronic HS despite failing to augment global translation. We therefore determined cell size and translation with A549 cells at different time points following exposure to chronic HS (Figure 6E). In contrast to WT cells for which cell size and translation appear to be coupled, Hsp90α/β KO cells increase cell size while translation is still reduced. Thus, cell size and translation must be coupled for adaptation to chronic stress. It remains to be seen how Hsp90α/β KO cells manage to increase their size without a concomitant scaling of translation and to what extent the mTORC1-mediated regulation of translation is involved.

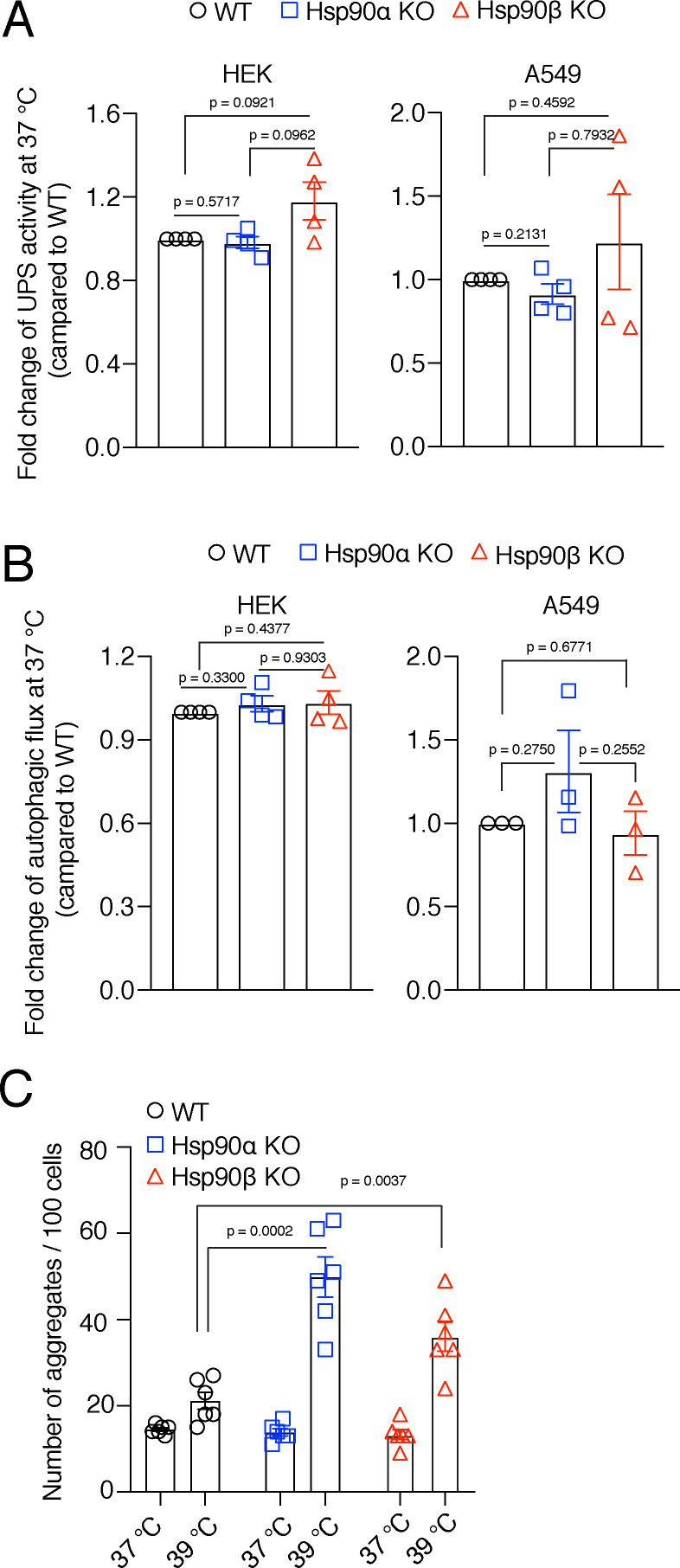

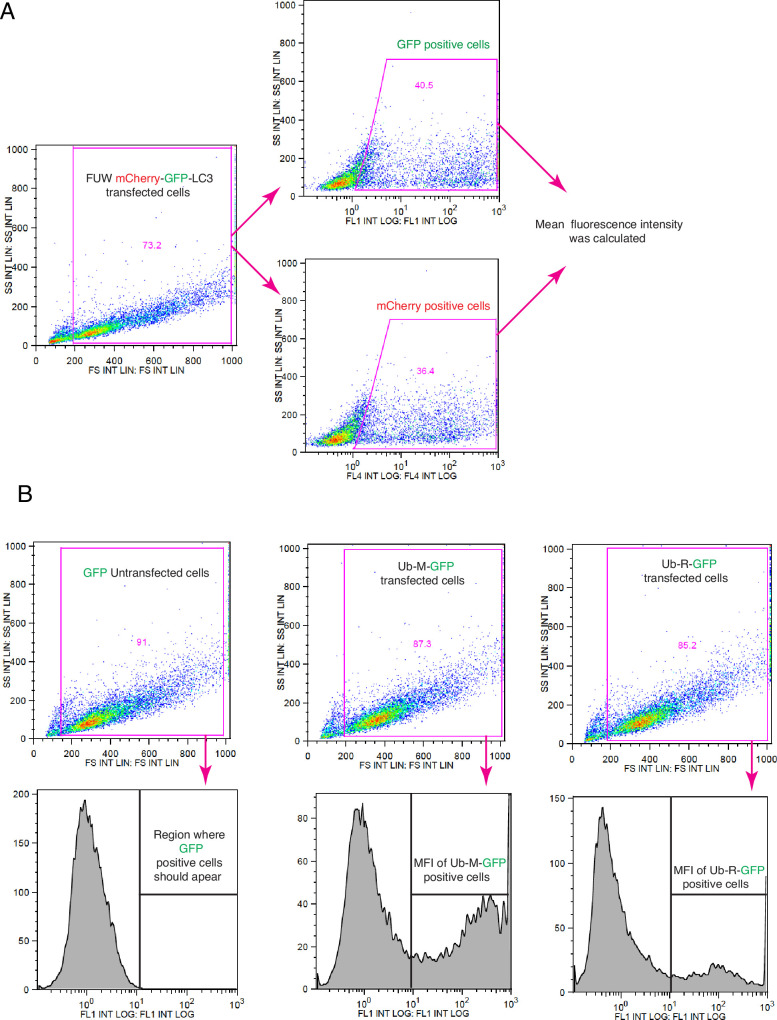

Hsp90α/β KO cells are efficient at maintaining cellular proteostasis under normal unstressed conditions

In experiments presented above, we showed that the loss of one Hsp90 isoform does not impair the protein refolding ability (Figure 4D and E), but reduces translation under chronic stress. Proteolysis is complementary to translation and folding, and crucial to prevent cytotoxicity by eliminating damaged proteins (Hipp et al., 2019). Cells promote the degradation of terminally misfolded proteins via the autophagy-lysosomal pathway (ALP) or the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) (Glickman and Ciechanover, 2002; Klaips et al., 2018). We performed an in vivo activity assay for the UPS, which involved the transient expression and flow cytometric quantitation of a degradation-prone ubiquitin-GFP fusion protein (Ub-R-GFP) and its stable counterpart (Ub-M-GFP) as a control (Dantuma et al., 2000). We observed no significant differences in the UPS activity of Hsp90α/β KO cells compared to WT cells at 37 °C (Figure 7—figure supplement 1A). We checked the ALP by measuring the autophagic flux using a mCherry-GFP-LC3 reporter (Leeman et al., 2018). Here also, we observed that the autophagic flux remains unchanged in Hsp90α/β KO cells (Figure 7—figure supplement 1B). These results lead us to conclude that one Hsp90 isoform is sufficient to maintain cellular proteostasis under normal, unstressed conditions.

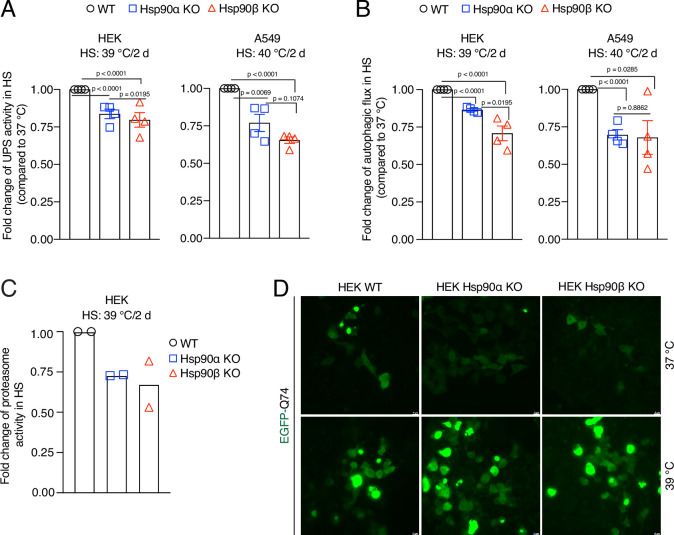

A normal level of Hsp90 is required to maintain cellular proteostasis in chronic stress

We recently reported that Hsp90α/β KO HEK cells accumulate insoluble proteins in long-term mild HS (Bhattacharya et al., 2022). We therefore checked the above-mentioned cellular proteostasis axes after two days of adaptation to chronic stress. We found that the absence of either one of the two Hsp90 isoforms causes a deficit in UPS activity in vivo (Figure 7A) and autophagic flux (Figure 7B). Hsp90α/β KO cells subjected to chronic HS also had reduced proteasomal activity when measured in vitro (Figure 7C). When we expressed the aggregation-prone model protein EGFP-Q74 (Narain et al., 1999) in stress-adapted Hsp90α/β KO cells, more and larger aggregates of EGFP-Q74 were readily detectable (Figure 7D, Figure 7—figure supplement 1C). This suggests that Hsp90α/β KO cells cannot efficiently maintain proteostasis in chronic stress. Since Hsp90α KO and Hsp90β KO cells are largely affected the same way, we conclude that there is no isoform specificity for maintaining proteostasis during stress, but that total Hsp90 levels above a certain threshold might be the critical parameter.

Figure 7. Hsp90 is crucial for cellular proteostasis during adaptation to chronic stress.

(A) Flow cytometric determination of the in vivo UPS activity in chronic HS compared to 37 °C, using the Ub-M-GFP and Ub-R-GFP reporter proteins (n=4 biologically independent samples). (B) Flow cytometric measurement of autophagic flux in chronic HS compared to 37 °C, using a mCherry-GFP-LC3 reporter. Flux is calculated as the ratio of the mean fluorescence intensities of mCherry and GFP-positive cells (n=4 biologically independent samples). (C) In vitro steady-state proteasomal activity with lysates of HEK WT, and Hsp90α and Hsp90β KO cells determined by measuring fluorescence of the cleaved substrate suc-LLVY-AMC (n=2 biologically independent samples). (D) Fluorescence micrographs of cells expressing the fusion protein EGFP-Q74 visible as aggregates with green fluorescence. The scale bars in the zoomable micrographs indicate 10 μm (images are representative of n=2 independent biological samples). The data are represented as mean values ± SEM for all bar graphs. The statistical significance between the groups was analyzed by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-tests.

Figure 7—figure supplement 1. Hsp90α/β KO cells maintain WT levels of protein degradation activities in unstressed conditions, but have more protein aggregates.

Figure 7—figure supplement 2. Schematic representation of the flow cytometric strategies for measuring autophagic flux and in vivo UPS activities.

Enlarged cells are more resistant to subsequent stress

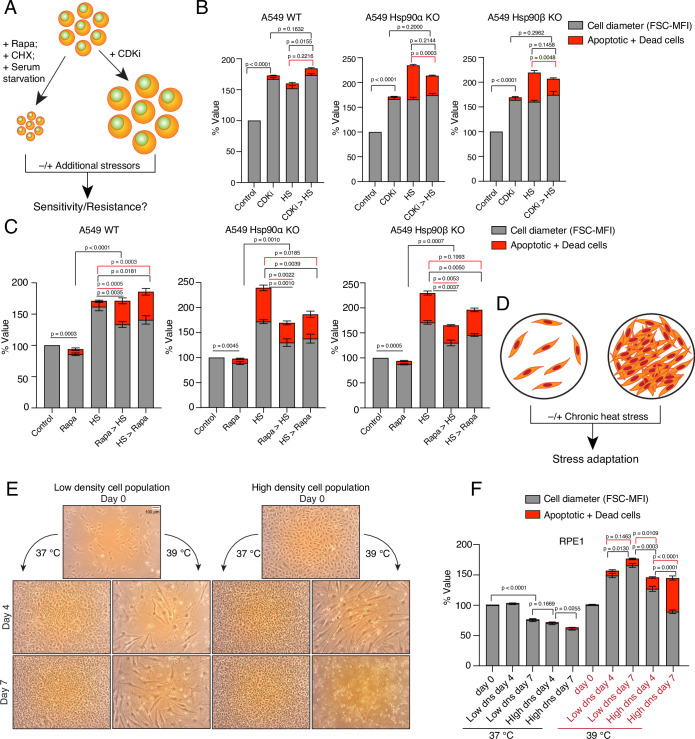

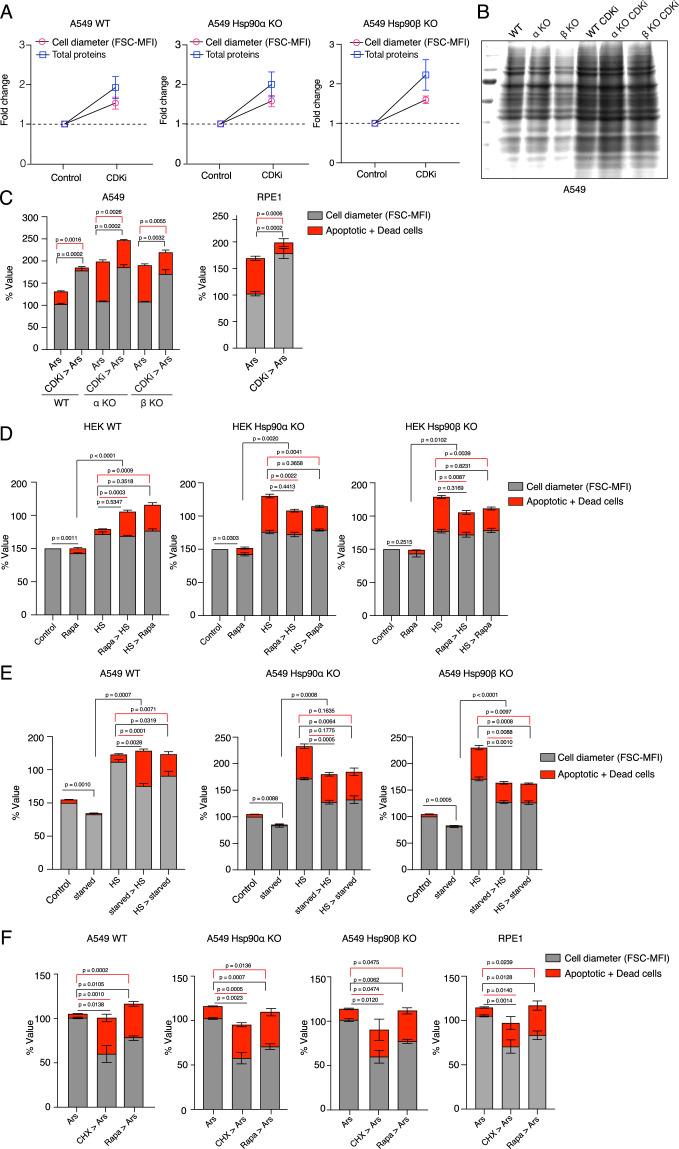

We hypothesized that the stress-induced cell size enlargement is a protective adaptation. To address this, we induced the enlargement or reduction of cell size with different inhibitors and examined how cell size affects cell survivability (Figure 8A). At first, we enlarged the A549 WT and Hsp90α/β KO cells by treating them with a CDK4/6 inhibitor (Figure 8B), which is known to promote a G1 arrest-associated increase in cell size (Neurohr et al., 2019). In contrast to what we had seen with chronic HS, upon becoming bigger in response to treatment with the CDK4/6 inhibitor, Hsp90α/β KO cells were able to scale the amount of total proteins (Figure 8—figure supplement 1A and B). This demonstrates that scaling total protein is possible even in the absence of one Hsp90 isoform and a reduced amount of total Hsp90 when cells are not in chronic HS. We showed above that Hsp90α/β KO cells were dying in chronic HS, possibly because they could not scale their protein with increasing cell size. We therefore wondered whether Hsp90α/β KO cells, enlarged with prior treatment with the CDK4/6 inhibitor, might be more resistant to chronic HS because they would already have scaled their total protein. After treatment with CDK4/6 inhibitors for three days, we washed off the inhibitors and subjected the cells to chronic HS for three days. We observed that cells that were already enlarged due to the CDK4/6 inhibitor treatment did not get even bigger in chronic HS. As predicted, these pre-enlarged Hsp90α/β KO cells were more resistant and less prone to apoptosis and cell death (Figure 8B). Thus, when given a chance to get bigger with protein scaling, even cells lacking one Hsp90 isoform are more resistant to chronic stress.

Figure 8. Enlarged cells are more resistant to additional stress.

(A) Scheme of cell size enlargement or reduction experiments. CHX, cycloheximide; CDKi, CDK4/6 inhibitor. (B) Cell size was first enlarged by treating cells with 100 nM CDKi for 3 days; then, cells were washed and subjected to chronic HS at 40 °C for 3 more days (CDKi >HS). Cell size (% FSC-MFI; grey part of the bars) and cell death (% annexin V and PI-positive; red part of the bars) were measured by flow cytometry. The values for cell size and death in the different experimental conditions are normalized to the respective 37 °C controls (n=3 biologically independent experiments). (C) Cells were first pretreated with 7.5 nM rapamycin (Rapa) for 3 days to reduce the cell size. After that, the cells were subjected to chronic HS at 40 °C for 3 days (Rapa >HS). HS >Rapa, the two treatments were done the other way around. The cell size (% FSC-MFI) and relative cell death (% annexin V and PI-positive) were quantified by flow cytometry. The values for cell size and death in different experimental conditions are normalized to the respective 37 °C control (n=3 biologically independent experiments). (D) Scheme of experiments aimed at determining impact of limiting physical space on cell size increase. (E and F) Phase-contrast micrographs of RPE1 cells seeded in different numbers to restrict the space for cell size increase during adaptation to chronic HS (representative images of n=4 biologically independent experiments). The size bar in the top left panel indicates 100 µM. The cell size (% FSC-MFI) and relative cell death (% annexin V-PI positive) are quantified by flow cytometry. For the bar graphs, the values for cell size and death in different conditions are normalized to the low density (dns) cell population at 37 °C day 0 (n=4 biologically independent experiments). The data are represented as mean values ± SEM for all bar graphs. The statistical significance between the groups was analyzed by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-tests.

Figure 8—figure supplement 1. Smaller cells are more susceptible to additional stress.

We further explored the connection between increase in cell size and scaled protein, and stress resistance with other stresses and cell lines. We treated the cells pre-enlarged with the CDK4/6 inhibitor with an acutely toxic concentration of sodium arsenite for one day. Again, pre-enlarged A549 cells of all three genotypes and the normal RPE1 cells were more resistant to this subsequent stress (Figure 8—figure supplement 1C). We then wondered whether reducing cell size would have the opposite effect. We treated HEK and A549 WT, and Hsp90α/β KO cells with rapamycin to inhibit mTOR-induced cell growth (Fingar et al., 2002; Figure 8C, Figure 8—figure supplement 1D). Cell size was indeed reduced after three days of rapamycin treatment (Figure 8C, Figure 8—figure supplement 1D). Surprisingly, we found that even in the presence of rapamycin cells enlarged their size under chronic HS, albeit not up to the level of cells without rapamycin pretreatment. More of these comparatively smaller rapamycin-treated WT cells were apoptotic than of the bigger cells not treated with rapamycin (Figure 8C, Figure 8—figure supplement 1D). The increased cell death could also be due to the translational inhibition, in light of the fact that WT cells display increased total translation and mTOR activity to adapt to chronic stress (Figure 6D, Figure 6—figure supplement 2). In contrast, we observed that comparatively smaller rapamycin-treated Hsp90α/β KO cells were less prone to apoptosis than the non-treated bigger cells. It remains to be seen whether the ratio of total protein to cell size is slightly more favorable in Hsp90α/β KO cells under these conditions. To further support the importance of mTOR, we treated the larger cells adapted to chronic HS with rapamycin. We observed that WT cells became more apoptotic when we added rapamycin after three days of stress adaptation (Figure 8C, Figure 8—figure supplement 1D). As rapamycin pre-treatment failed to restrict the cell size increase caused by chronic stress, we then tried to limit the cell size increase with serum starvation (Figure 8—figure supplement 1E). We observed that even serum-starved cells enlarged their size in additional chronic stress as they did with rapamycin. Here again, the size enlargement was not up to the level of non-starved cells. We observed that the serum-starved smaller WT cells died more under stress than the non-starved bigger cells (Figure 8—figure supplement 1E). As with the rapamycin treatment, in most cases, the serum-starved smaller Hsp90α/β KO cells survived better than the bigger non-starved cells. In both experiments, we did not succeed in preventing the cell size increase upon exposing cells to chronic HS. As a control experiment, we subjected smaller cells obtained with cycloheximide or rapamycin treatment to an acute stress with arsenite for one day. We found that smaller cells were more sensitive to acute stress irrespective of Hsp90 isoform and levels (Figure 8—figure supplement 1F). The above-mentioned control experiments also argue that stress resistance is not per se afforded by increased autophagy, as induced by rapamycin, nor by cellular quiescence as induced, for example, by starvation.

We then wondered what would happen if we limited the cell size increase by limiting the available space (Figure 8D). We used RPE1 cells, as these cells always grow in single layers and do not grow on top of each other once they are entirely confluent. We observed that at 37 °C, once they become confluent, they do not stop dividing, but become smaller and smaller (Figure 8E and F). In contrast, in chronic HS, over time, they enlarge their size and keep dividing when seeded at low density. Next, we seeded a comparatively higher number of cells, such that the culture plate would already be confluent from the beginning, and put it in chronic HS. We observed that the cells in the 'already-confluent' plate at 37 °C kept dividing and shrinking, without obvious cell death (Figure 8E and F). However, in chronic HS, the cells in the 'already-confluent' plate, while they were initially able to enlarge their size to some extent, when their size eventually shrank because of the limited space, they started dying off (Figure 8F).

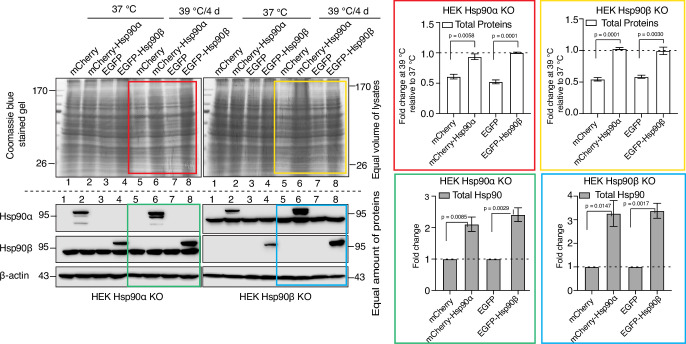

Adaptation to chronic stress requires cytosolic Hsp90 above a threshold level irrespective of Hsp90 isoform

So far, our experiments did not reveal any obvious functional differences between the two cytosolic Hsp90 isoforms. This supports the conclusion that the observed phenotypes in chronic stress, rather than being linked to a specific isoform, are due to below threshold levels of total Hsp90. To address this more directly, we exogenously overexpressed Hsp90α or Hsp90β as mCherry or EGFP fusion proteins, respectively, in Hsp90α/β KO cells. This caused an overall increase in total Hsp90 levels (Figure 9). The transfected cells were subjected to chronic HS. After four days, we checked the scaling of total protein by loading an equal volume of cell lysate on a protein gel (see Materials and Methods for details). We found that when the total levels of Hsp90 are elevated by either one of the two isoforms, Hsp90α/β KO cells are able to scale total protein under chronic HS (Figure 9). This result complements our previous findings that Hsp90α/β KO cells become more resistant to both acute and chronic HS upon increasing total Hsp90 levels, irrespective of Hsp90 isoform (Bhattacharya et al., 2022).

Figure 9. Adaptation to chronic stress requires cytosolic Hsp90 above a threshold level.

Immunoblots in the lower panels show the endogenous Hsp90α and Hsp90β, and the exogenously overexpressed larger fusion proteins of Hsp90α (as mCherry-Hsp90α) and Hsp90β (as EGFP-Hsp90β). Images of the Coomassie-stained gels in the upper panels show the corresponding levels of total proteins. Colored boxes indicate lanes for samples from cells subjected to chronic HS. The bar graphs on the right show the corresponding quantitation of three biologically independent experiments, with the colored rectangles using the same color code as the rectangles over the immunoblots on the left. The band densities of all blots were normalized to the loading controls. The data are represented as mean values ± SEM. The statistical significance between the groups was analyzed by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-tests.

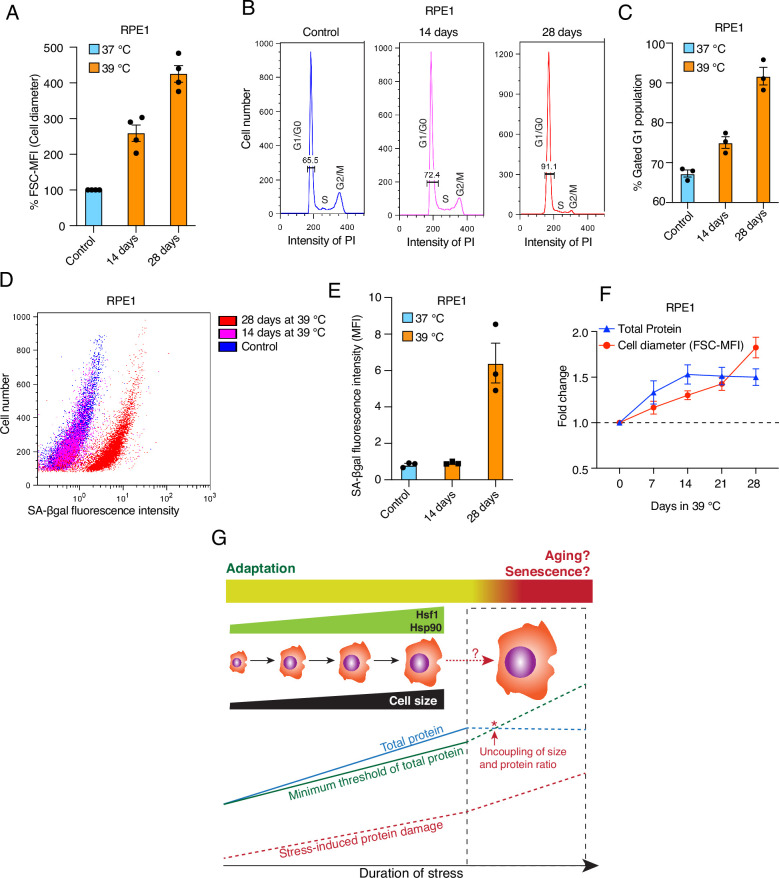

Prolonged mild stress leads to excessively bigger cells with an unbalanced cell size to protein ratio associated with senescence

Increased cell size is a hallmark of senescence and aging (Childs et al., 2015; McHugh and Gil, 2018; Calcinotto et al., 2019), whereas we demonstrate here that enlarging cell size is beneficial, at least within the timeframe of our chronic stress paradigm (4–7 days). To determine whether stress-induced cell size enlargement eventually leads to senescence and aging, we maintained RPE1 cells at 39 °C for up to 4 weeks. We observed that these cells continued to enlarge their size (Figure 10A). Preliminary results (not shown) suggest this is also true for HEK cells. The cell cycle analysis of RPE1 cells revealed that over time more and more cells became arrested in G1 (Figure 10B and C), potentially indicating senescence. To obtain more direct evidence for senescence, we assessed the activity of the senescence-associated marker β-galactosidase (SA-βgal) using flow cytometry. We observed that with chronic stress prolonged beyond two weeks, cells showed a strong increase in SA-βgal activity (Figure 10D and E). Intriguingly, when we measured both cell size and total protein over a time course of 4 weeks, we found that cells failed to scale total protein beyond two weeks of mild stress (Figure 10F), akin to what had been reported by Neurohr and colleagues for excessively large cells (Neurohr et al., 2019). This suggests that the benefits of a larger cell size are lost with much prolonged stress as cells get excessively larger, cannot adjust total protein anymore, and therefore begin to senesce. Thus, while chronic stress initially leads to a protective cell size increase, there is a threshold of chronic stress, possibly in a cell type-specific fashion, beyond which cells cannot cope anymore (Figure 10G).

Figure 10. Prolonged mild chronic stress triggers excessively bigger cell size and senescence.

(A) Flow cytometric quantification of cell size of RPE1 cells exposed to prolonged mild HS (n = 4 biologically independent samples). (B) Histograms representing the cell cycle distribution of RPE1 cells exposed to prolonged mild HS as indicated, as determined by flow cytometry. (C) Quantitation of flow cytometric analyses of the cell cycle (n=3 biologically independent samples). (D) Dot plot representing numbers of cells as a function of SA-βgal staining analyzed by flow cytometry. (E) Bar graph showing the mean fluorescent intensities of three biologically independent SA-βgal staining experiments of the type shown in panel D. (F) Fold change of cell size (represented by the FSC-MFI values) and total proteins (determined as MFI-FL1 values) in prolonged chronic HS, as analyzed by flow cytometry. Cells were fixed, and total proteins were stained using Alexa Fluor 488 NHS ester (n=3 biologically independent experiments). Lines connecting the data points are solely drawn as a visual aid. Note that the quantitative differences of cell size increases between panels A and F may be due to technical differences (live cell versus fixed cell analyses, respectively; see Materials and Methods for further details). (G) Schematic representation of the impact of chronic mild stress on cells. Wild-type cells initially adapt by enlarging their size and increasing total protein to maintain a minimum threshold level of functional proteins. The right part of the scheme (surrounded by a stippled box), shows what happens if stress persists for much longer: cell size enlargement and total amount of proteins are uncoupled, and because of protein damage, which continues to accumulate, cells become senescent and/or die. The data for all the bar graphs are represented as mean values ± SEM.

Discussion

It is now increasingly recognized that exposure to mild environmental stressors is not necessarily detrimental to the organism. Instead, such experiences may foster a resistant or adapted phenotype through hormesis (Agathokleous and Calabrese, 2022). Hormesis is a core mechanism of developmental plasticity by which an organism’s response to a stressor varies with exposure (Schirrmacher, 2021). In contrast, hormetic priming is confined to specific temporal windows and can be considered a preparation to cope with stress. The biological process of aging is claimed to be associated with hormesis (Gems and Partridge, 2008). Therefore, physiological cellular responses to mild rather than severe stresses may be more important to address in order to comprehend the biology of aging.

Cell size enlargement is a prerequisite for chronic stress adaptation

We report that cells adapt to chronic stress by gradually enlarging their size, through a process coupled with increased translation. Stress-induced cell size enlargement is a step towards stress adaptation as part of an intrinsic stress response. Even when we used inhibitors known for restricting the cell size, chronic stress still induced a cell size increase (Figure 8, Figure 8—figure supplement 1). This suggests that cell size enlargement is a necessity for cells to adapt to prolonged stress. Cell size enlargement has also been linked to cellular senescence, which is a state of long-term cell cycle arrest (Childs et al., 2015; McHugh and Gil, 2018; Calcinotto et al., 2019). In contrast, stress-adapted bigger cells continue to proliferate. It has been reported that bigger cells, when they cannot scale their cellular macromolecules, suffer from cytoplasmic dilution and become senescent (Neurohr et al., 2019). The adaptive cell size enlargement in response to chronic stress is coupled with increased translation, which enables cells to maintain their cytoplasmic density and macromolecular crowding. Maintaining macromolecular crowding is necessary to control the kinetics of cellular reactions and to avoid an aging-related deterioration of cellular biochemical processes (Mourão et al., 2014). Hence, the adaptive cell size increase in response to chronic stress is different from that associated with cellular senescence. Our observations demonstrate that the coupling of cell size enlargement and translation is essential for cells to adapt to chronic stress. Failure to do so causes their elimination during stress exposure, as we observed with Hsp90-deficient cells.

Hsp90 enables the rewiring of the stress response

Hsp90-deficient cells subjected to chronic stress suffer from cytoplasmic dilution. For long-term survival under intrinsic or environmentally imposed chronic stress, cells must maintain an equilibrium of protein synthesis, maintenance, and degradation (Labbadia and Morimoto, 2015; Hipp et al., 2019). Our results indicate that Hsp90 is a key molecule for sustaining translation under these conditions. Unlike during the ISR, in which global cap-dependent protein translation is specifically reduced by the hyperphosphorylation of eIF2α (Costa-Mattioli and Walter, 2020; Persson et al., 2020), during adaptation to chronic stress, we observed a different phenomenon, which we term "rewiring stress response" (RSR). During RSR, cells initially reduce global translation as happens during an ISR. Then, they turn global translation back on, even when they continue to be exposed to the same stress. This leg of the response requires a threshold level of Hsp90. A hallmark of these transitions is the phosphorylation status of eIF2α and its accompanying impact on global translation. At the beginning of a chronic stress, eIF2α is hyperphosphorylated and global translation is inhibited, whereas prolonged exposure to chronic stress results in the reduction of eIF2α phosphorylation and resumption of translation (Figure 6C and E, Figure 6—figure supplements 1 and 2). Thus, the dephosphorylation of eIF2α is central to this phase of the RSR, as it is to terminating the ISR (Pakos-Zebrucka et al., 2016). While WT cells switch translation back on, the status of eIF2α phosphorylation and puromycin labeling show that Hsp90α/β KO cells are unable to support this transition, even though they continue to express stress-inducible chaperones and co-chaperones at high levels (Figure 4). It appears that Hsp90-deficient cells are stuck at the ISR stage of the RSR. While the ISR is a powerful survival strategy in acute stress, it fails to support the survival of Hsp90-deficient cells during chronic stress adaptation. The ability to mount a RSR is pivotal for the adaptation of cells to chronic stress. The translational recovery and the expression of some of the stress-inducible genes in response to acute stress of the ER and oxidative stress depend on protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) and its regulator GADD34 (Novoa et al., 2003; Carrara et al., 2017; Krzyzosiak et al., 2018). However, our proteomic data indicated that there are no significant changes of PP1 or GADD34 protein levels when one compares cells of different genotypes and stress conditions. Hence, what factors and mechanisms allow cells to transition to RSR remains to be discovered. We report here that a threshold level of total Hsp90 is important to turn on the RSR, not the presence of a particular Hsp90 isoform. If one experimentally elevates the levels of either one of the isoforms, cells can activate the RSR (Figure 9).

Larger cells may be more stress-resistant because of above-threshold levels of macromolecules

When acute stress triggers the ISR, cells only translate selected proteins. With persistent intense stress, the ISR cannot support proteostasis and shifts cells toward apoptosis (Tian et al., 2021). When stress is chronic, cells need more than this limited set of proteins. This is where the RSR comes in, allowing cells to get bigger, and to accumulate more protein molecules, and potentially other macromolecules, per cell. It is conceivable that there is an evolutionarily optimized range or a minimal threshold level for all macromolecules, and that this depends on the specific biological needs of a given cell type subjected to a particular type of stress (Figure 10G). If the absolute numbers per cell of certain molecules are more important than concentration to adapt and to survive under chronic stress, then bigger cells, which have larger stocks of those molecules, may be better at coping with limited damage than smaller cells. This may even apply to proteins involved in translation, including ribosomal proteins, which did not fully scale even in WT cells. As long as individual cells are above the threshold levels for all relevant macromolecules, they can adapt. Hence, growing bigger is an adaptive response that confers higher stress resistance.

This notion is also supported by our recent findings with mouse KOs (Bhattacharya et al., 2022). When we reduced the number of alleles for the cytosolic Hsp90 isoforms from four to one, only embryos that could reestablish the threshold levels of Hsp90 protein by translational reprogramming survived and displayed no apparent phenotype, despite the fact that Hsp90 levels were still lower than those of WT littermates (Bhattacharya et al., 2022). There is also evidence that cells can maintain favorable macromolecular crowding by reducing the concentration of highly abundant proteins. The mTORC1 pathway modulates the effective diffusion coefficient within the cytoplasm by reducing the number of ribosomes (Delarue et al., 2018). This can avoid increasing molecular crowding, which has been shown to hinder the kinetics of biochemical reactions (Trappe et al., 2001; Zhou et al., 2008; Miermont et al., 2013; Mourão et al., 2014). Increased macromolecular crowding might affect protein folding, final shape, conformational stability, binding of small molecules, enzymatic activity, protein-protein interactions, protein-nucleic acid interactions, and pathological aggregation (Kuznetsova et al., 2014). Hence, cells that are exposed to prolonged proteotoxic stress might try to maintain a threshold of all the required proteins instead of scaling all proteins at a particular concentration, while tuning molecular crowding to maintain optimal cytoplasmic diffusion coefficients.

Hsf1-dependent cell size enlargement drives the activation of translation in chronic stress

We found that cell size enlargement during chronic stress depends on Hsf1 activity. This is reminiscent of prior evidence that demonstrated that Hsf1 is linked to the regulation of cell size in different tissues in mammals (Sakamoto et al., 2006; Koya et al., 2013; Su et al., 2016; Obi et al., 2019). Hsf1 had been reported to maintain cell growth in a noncanonical way by preserving mTORC1 activity and translation by binding and inactivating the kinase JNK, a known inhibitor of mTORC1 activity (Su et al., 2016). In contrast, the cell size increase in response to chronic stress appears to be a canonical Hsf1-mediated HSR phenomenon, which is upstream and independent of the scaling of cellular translation. This is supported by several experiments. Hsp90α/β KO cells subjected to chronic stress could increase their size despite reduced translation. Chronic stress still induced an increase of cell size upon inhibition of translation with rapamycin or cycloheximide, or by serum starvation (Figure 8, Figure 8—figure supplement 1). We conclude from all of these observations that increased translation is not necessary for cells to increase their size under chronic stress. WT cells start enlarging their size as a response to chronic stress and then translation follows to scale total protein levels. Hsp90α/β KO cells also increase their size in response to stress but fail to couple that to translation, which causes cytoplasmic dilution.

In keeping with the motto ‘more is better’ for increased stress resistance under chronic stress, we found that cells proportionately increase the size of their nuclei. Although the mechanism and potential adaptive advantage of this organellar enlargement remain to be elucidated, it seems unlikely that it reflects an increase in genomic DNA, such as polyploidy. At the scale of the observed increase in nuclear size, we would have noticed it in our flow cytometric analyses, and cell size enlargement was readily reversible once chronic stress subsided (Figure 1H). Heat stress is known to induce chromatin rearrangements, and Hsf1-mediated transcription of repeat sequences and regions of constitutive heterochromatin (Rizzi et al., 2004; Sun et al., 2020; Vourc’h et al., 2022). It is therefore imaginable that genome ‘unfolding’ underlies the enlargement of the nucleus and that it facilitates a global increase in expression.

Aging as a failure to adapt to chronic stress

Overall, our findings are relevant to understanding aging. It is well established that mammalian cells get bigger as they grow older (Cristofalo and Kritchevsky, 1969; Treton and Courtois, 1981; Demidenko and Blagosklonny, 2008; Mammoto et al., 2019). We speculate that cells enlarge their size with aging as a protective adaptation to accumulating intra- and extracellular stressors. As long as cells manage to scale the biosynthesis of macromolecules such as proteins, their increasing size mitigates the impact of aging (Figure 10G). Eventually, the accumulation of stressors, and the breakdown of proper scaling of macromolecules, cannot completely prevent the development of features of aging.

Our findings may have implications for rejuvenation therapies aimed at delaying or even reverting cellular aging (Blagosklonny, 2019). Treatment with the mTORC1 inhibitor rapamycin has been reported to improve the function of aged cells and to lengthen the life span of laboratory animals (Hansen et al., 2007; Selman et al., 2009; Bjedov et al., 2010). Despite the low doses that are experimentally used to prevent an age-related decline, there are several adverse side effects. Our data indicate that treatment with mTORC1 inhibitors should be personalized based on the cellular stress level. For healthy cells, where translation plays a vital role in chronic stress adaptation, long-term treatment with rapamycin might affect cellular homeostasis and precipitate aging, or even induce apoptosis. For aged cells with a weakening proteostatic system, rapamycin may rejuvenate cells by reducing translation and inducing autophagy. This is supported by our observation that Hsp90α/β KO cells, where proteostasis is compromised, rapamycin treatment helped the cells to survive better under chronic stress (Figure 8, Figure 8—figure supplement 1) (see also Bhattacharya et al., 2022). We conclude that rather than running the risk of inducing premature aging with prolonged rapamycin treatment from a relatively early age, efforts should focus on developing compounds that induce Hsp90 expression and/or activity, which one could expect to delay aging.

Physiological changes of cell size

Our observations demonstrate that changes of cell size do not have to be the result of physical constraints, but can be a regulated adaptation. There is evidence for changes in cell size that are induced by physiological conditions (Ginzberg et al., 2015), and, of course, aging would be one of them. For example, for rat pancreatic β-cells, insulin secretion, metabolic activity, and global protein production rates are positively correlated with cell size (Bernal-Mizrachi et al., 2001). In the kidney, epithelial cells modulate their size in response to fluid flow rates (Boehlke et al., 2010). Muscle fibers increase their size in an Hsf1-mediated response to heat generated by exercise (Obi et al., 2019). Hsf1 null mice cannot increase the size of their skeletal muscle cells (Koya et al., 2013). Furthermore, Hsf1 plays a critical role in the adaptive increase of the size of cardiac cells (Sakamoto et al., 2006). In many organs, when cell numbers decrease due to aging, this is compensated by an increase in cell size to maintain the overall functional capacity (Ginzberg et al., 2015). Pancreatic β cells increase their size by over 25% during pregnancy in response to increased insulin demand (Dhawan et al., 2007). Similarly, the size of the liver increases during pregnancy through hepatocyte hypertrophy (Milona et al., 2010), and liver organ and cell size undergo circadian oscillations (Sinturel et al., 2017). Hepatocyte size was also found to increase in organisms continuously exposed to toxic environments (Hall et al., 2012). These examples support the idea that it is advantageous for a specific cell type to adopt a specific size under particular physiological conditions. Based on our findings with chronic stress, it would be worth investigating whether Hsp90 more generally supports translational scaling in the context of these physiological changes in cell size.

Limitations of this study

Hsf1 mediates the cell size increase stimulated by chronic stress, but how chronic stress is sensed and relayed to Hsf1 remains to be established. The underlying mechanism may not be exactly the same as the one involved in mediating acute stress, which itself remains poorly understood. Furthermore, how Hsf1 induces the cell size increase is unknown, and the role of Hsp90 in stimulating translation needs to be dissected in more detail. The latter undoubtedly would be very challenging considering that many of the factors involved in translation, in addition to the eIF2α kinases (Kudlicki et al., 1987; Rose et al., 1987; Matts and Hurst, 1989; Donzé and Picard, 1999; Donzé et al., 2001; Marcu et al., 2002; Ota and Wang, 2012; Zhao et al., 2019), are likely to be Hsp90 clients. Finally, our experiments with prolonged chronic stress, which demonstrate that eventually even wild-type RPE1 cells cannot maintain homeostasis anymore, raise new questions; above all, it will have to determined whether this is generally true for different cell lines and cell types, and for different types of stresses. Moreover, it is conceivable based on these findings with prolonged stress that there may be limits to how much long-term chronic stress, or combinations of stresses, cells and organisms can handle, even at very low stress levels, with potentially far-reaching consequences.

Materials and methods

Key resources table.

| Reagent type (species) or resource | Designation | Source or reference | Identifiers | Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell line (Homo-sapiens) | HEK293, Human embryonic kidney cells | ATCC | CRL-3216 | corresponding Hsp90α/β KO cell lines were generated |

| Cell line (Homo-sapiens) | A549, human lung epithelial carcinoma cells | ATCC | CCL-185 | corresponding Hsp90α/β KO cell lines were generated |