Abstract

A divE mutant, which has a temperature-sensitive mutation in the tRNA1Ser gene, exhibits differential loss of the synthesis of certain proteins, such as β-galactosidase and succinate dehydrogenase, at nonpermissive temperatures. In Escherichia coli, the UCA codon is recognized only by tRNA1Ser. Several genes containing UCA codons are normally expressed after a temperature shift to 42°C in the divE mutant. Therefore, it is unlikely that the defect in protein synthesis at 42°C is simply caused by a defect in the decoding function of the mutant tRNA1Ser. In this study, we sought to determine the cause of the defect in lacZ gene expression in the divE mutant. It has also been shown that the defect in lacZ gene expression is accompanied by a decrease in the amount of lacZ mRNA. To examine whether inactivation of mRNA degradation pathways restores the defect in lacZ gene expression, we constructed divE mutants containing rne-1, rnb-500, and pnp-7 mutations in various combinations. We found that the defect was almost completely restored by introducing an rne-1 pnp-7 double mutation into the divE mutant. Northern hybridization analysis showed that the rne-1 mutation stabilized lacZ mRNA, whereas the pnp-7 mutation stabilized mutant tRNA1Ser, at 44°C. We present a mechanism that may explain these results.

The divE mutant of Escherichia coli K-12 exhibits differential loss of the synthesis of certain proteins at nonpermissive temperatures (24). When a culture of the divE mutant grown at 30°C was shifted to 42°C, cell growth first continued and then gradually stopped after an about twofold increase in the amount of bulk proteins. The rates of synthesis of most cellular protein were not affected by the temperature shift up, but the synthesis of particular proteins, such as β-galactosidase and succinate dehydrogenase, stopped immediately (26, 32, 38). It has also been reported that when cells exposed to 42°C were returned to a permissive temperature, they started to grow and divided synchronously (25).

The divE gene is located at 22 min on the genetic map (32), and nucleotide sequence determination of the cloned gene revealed that the divE gene product is tRNA1Ser and that the divE42 mutation is a base substitution of A10 for G10 in the D stem of tRNA1Ser (35). Among six serine codons, the UCA codon is recognized only by tRNA1Ser in E. coli (14, 34). In the divE mutant, some genes containing UCA codons, such as recA and trpED, are expressed normally after the temperature shift to 42°C. Therefore, it is unlikely that a defect in the synthesis of certain proteins at 42°C is simply caused by a deficiency of the mutant tRNA1Ser decoding function. Furthermore, Yamada and Ishikura reported that the serine acceptor activity of mutant tRNA1Ser (ts-tRNA1Ser) measured experimentally in vitro is not temperature sensitive (37).

It has been shown that in the divE mutant, the defect in β-galactosidase synthesis at 42°C is accompanied by a decrease in the amount of lacZ mRNA (26). We also found, by S1 mapping, that the initiation of lacZ gene transcription was almost normal at 42°C (unpublished data). Therefore, the lower level of lacZ mRNA may be caused by either premature transcriptional termination or increased degradation of the transcript by RNases.

When a multicopy plasmid containing the mutant divE gene was transformed into the divE mutant, the defect in lacZ gene expression was completely reversed (37), but a single-copy plasmid containing the mutant divE gene cannot complement the defect. These results indicate that lacZ gene expression at 42°C is dependent on the cellular concentration of tRNA1Ser.

To elucidate the molecular mechanism of the defect in lacZ gene expression in the divE mutant, we investigated whether inactivation of the mRNA degradation pathways could restore the defect in lacZ gene expression. Arraiano et al. have shown that two exoribonucleases, polynucleotide phosphorylase (PNPase) and RNase II, and an endoribonuclease, RNase E, are directly involved in mRNA degradation in E. coli (3). Therefore, we constructed isogenic divE mutants containing rne-1, rnb-500, and pnp-7 mutations in various combinations and examined whether the defect in lacZ gene expression was suppressed by these mutations. Our results indicate that β-galactosidase expression in the divE mutant was almost completely reversed by introducing rne-1 pnp-7 double mutations. We also present results showing how individual RNases are involved in this process.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

All of the strains used in this study are described in Table 1. To introduce the divE42 mutation into various strains, we inserted a transposable drug resistance element, Tn5, adjacent to the divE gene. λ467 (λ b221 rex::Tn5 cI857 Oam29 Pam80) was used for random insertion of Tn5 into the chromosome of strain KY2329#6 (pyrD+ divE42) (5, 7). P1vir phage grown on this library was used to transduce strain KY2504 (pyrD34 divE42), and the pyrD+ Kmr transductant was selected. We refer to it as KYR25. In KYR25, a Kmr marker was inserted adjacent to divE42 because pyrD is located at 21 min, adjacent to the divE gene (22 min) on the genetic map (32). A P1vir lysate grown on KYR25 was used to transduce the divE42 allele into various RNase-deficient strains. The divE gene is 52% cotransducible with Tn5. Transductants were screened by Southern hybridization analysis to detect the replacement of base G10 with A10 in tRNA1Ser.

TABLE 1.

E. coli strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Source (reference) |

|---|---|---|

| KY2329#6 | thyA thr metE endA1100 tsx rpoB serC13 divE42 | T. Sato (32) |

| KY2504 | thyA thr metE endA1100 tsx rpoB pyrD34 divE42 | T. Sato (32) |

| KYR25 | thyA thr metE endA1100 tsx rpoB divE42 zcb::Tn5 | This study |

| MG1693 | thyA715 | S. R. Kushner (3) |

| SK5704 | thyA715 rne-1 pnp-7 rnb-500 | S. R. Kushner (3) |

| SK5665 | thyA715 rne-1 | S. R. Kushner (3) |

| SK5671 | thyA715 rne-1 pnp-7 | S. R. Kushner (3) |

| SK5691 | thyA715 pnp-7 | S. R. Kushner (3) |

| SK5715 | thyA715 rne-1 rnb-500 | S. R. Kushner (3) |

| SK5689 | thyA715 rnb-500 | S. R. Kushner (3) |

| SKR207 | thyA715 zcb::Tn5 | This study |

| SKR319 | thyA715 divE42 zcb::Tn5 | This study |

| SKR101 | thyA715 rne-1 pnp-7 rnb-500 zcb::Tn5 | This study |

| SKR104 | thyA715 rne-1 pnp-7 rnb-500 divE42 zcb::Tn5 | This study |

| SKR505 | thyA715 rne-1 zcb::Tn5 | This study |

| SKR615 | thyA715 rne-1 divE42 zcb::Tn5 | This study |

| SKR913 | thyA715 pnp-7 zcb::Tn5 | This study |

| SKR911 | thyA715 pnp-7 divE42 zcb::Tn5 | This study |

| SKR893 | thyA715 rnb-500 zcb::Tn5 | This study |

| SKR894 | thyA715 rnb-500 divE42 zcb::Tn5 | This study |

| SKR712 | thyA715 rne-1 pnp-7 zcb::Tn5 | This study |

| SKR711 | thyA715 rne-1 pnp-7 divE42 zcb::Tn5 | This study |

| SKR153 | thyA715 rne-1 rnb-500 zcb::Tn5 | This study |

| SKR151 | thyA715 rne-1 rnb-500 divE42 zcb::Tn5 | This study |

Assay of β-galactosidase.

M9 minimal medium supplemented with thymine at 25 μg/ml, Casamino Acids at 1% (wt/vol), and glycerol at 0.2% (wt/wt) was used (17). Kanamycin was added to the medium at 20 μg/ml to maintain the Kmr marker. Cells were grown to mid-log phase at 30°C. Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was then added to the culture at 2 mM, and an aliquot of the culture was immediately shifted to 44°C while another was kept at 30°C for further growth. Samples were removed every 6 min until 30 min after the temperature shift, and enzymatic activity was assayed as previously described (29). One unit of enzyme activity was defined as that which hydrolyzes 1 μmol of o-nitrophenyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (ONPG) per h.

Northern hybridization.

Cells were grown as described above and harvested 30 min after the induction and the temperature shift, and then total RNAs were extracted with hot phenol as described by Aiba et al. (2).

For analysis of lacZ mRNA, a 1.5% agarose gel containing 6% formaldehyde was used. Samples (5 μg) of total RNAs were fractionated by electrophoresis at 20 V overnight. RNAs were then blotted onto a nylon membrane (Hybond N; Amersham) and fixed by UV irradiation. The 300-bp DNA fragment containing a lac promoter sequence and the coding sequence for the N-terminal 53 amino acids of β-galactosidase was used as a probe. The labelling reactions were performed with [α-32P]dCTP and the Multiprime DNA labelling system (Amersham). The radioactivity of each band in the Northern hybridization was quantified by using a BAS2000 Imaging Analyzer (Fuji). The amount of 3.1-kb lacZ mRNA was precisely quantified from the same duplicate Northern blots.

For analysis of tRNA, 2-μg samples of total RNAs were electrophoresed on an 8% polyacrylamide gel containing 8 M urea and transferred by electroblotting to a nylon membrane (Clear Blot Membrane-N; Atto) in 1× TAE (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.8], 5 mM sodium acetate, 0.5 mM EDTA). A 32P-labelled 359-bp fragment containing the coding sequence for tRNA1Ser and a putative ρ-independent transcriptional termination signal was used as a probe.

For determination of the half-life of tRNA1Ser, cells were grown at 30°C to mid-log phase, and then rifampin was added at 500 μg/ml, and at the same time, an aliquot of the culture was shifted to 44°C. The radioactivity that remained on bands of 88-nucleotide (nt) mature tRNA1Ser was quantified.

RESULTS

Triple mutation of the RNase genes restores repression of lacZ gene expression in the divE mutant.

We constructed the isogenic divE mutant containing the rne-1, pnp-7, and rnb-500 alleles to examine whether the RNA degradation pathway participates in the decrease in lacZ mRNA at nonpermissive temperatures. In wild-type strain SKR207, inducible synthesis of β-galactosidase at 42°C was about the same as at 30°C (data not shown), while in divE mutant strain SKR319, synthesis of β-galactosidase was barely detected at a nonpermissive temperature (42°C), as reported previously (26). Not only divE42 mutations, but also rne-1 and rnb-500 mutations, are temperature sensitive, and the nonpermissive temperature for rne-1 and rnb-500 mutations is 44°C (3, 8, 28). We then used a temperature shift from 30 to 44°C to examine the effect of a triple mutation on expression of the lacZ gene in a divE mutant. Growth rates of the rne-1 pnp-7 rnb-500 triple mutant, either with or without a divE42 mutation, decreased gradually about 30 min after the shift to 44°C in M9 medium. To minimize the effects of the triple mutation on various cellular functions, all samples were removed within 30 min after the temperature shift to 44°C.

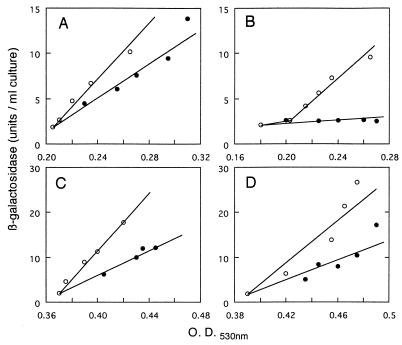

As shown in Fig. 1A, inducible synthesis of β-galactosidase at 44°C was somewhat (about 60%) lower than that at 30°C in strain SKR207. β-Galactosidase was hardly synthesized at 44°C in the divE mutant containing the wild-type RNase genes (SKR319) (Fig. 1B). Introduction of the triple mutation into strain SKR207 had no significant effect on β-galactosidase synthesis (Fig. 1C), while in SKR104 (divE42 rne-1 rnb-500 pnp-7), synthesis of β-galactosidase was obviously restored (Fig. 1D) and the level of β-galactosidase at 44°C in SKR104 was comparable to that in SKR101 (divE+ rne-1 rnb-500 pnp-7).

FIG. 1.

Induction of β-galactosidase in various divE mutants at 30 and 44°C. Cells were grown in M9 medium to mid-log phase at 30°C, and IPTG was then added to the culture at 2 mM. An aliquot of the culture was immediately shifted to 44°C, and another was grown at 30°C. One unit of enzyme activity was defined as that which hydrolyzed 1 μmol of ONPG per h. A, SKR207 (wild type); B, SKR319 (divE42); C, SKR101 (rne-1 pnp-7 rnb-500); D, SKR104 (rne-1 pnp-7 rnb-500 divE42). Symbols: ○, 30°C; •, 44°C. O.D.530nm; optical density at 530 nm.

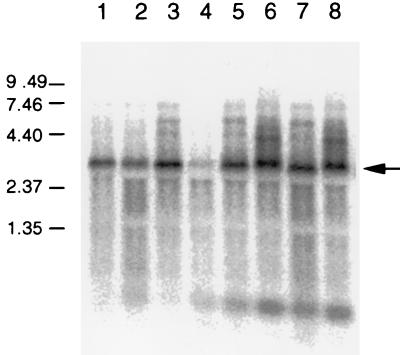

It was shown previously that a defect in lacZ gene expression in the divE mutant was accompanied by a lower amount of lacZ mRNA (26). We then examined the steady-state level of lacZ mRNA by Northern hybridization (Fig. 2). The probe used detected three discrete bands, 5.2, 4.5, and 3.1 kb in length, which corresponded to the full-length transcript (ZYA) and to the species processed between lacY and lacA (ZY) and lacZ and lacY (Z), respectively. This overall pattern of bands detected by Northern hybridization was the same in all of the strains used in the experiment, as shown in Fig. 2. One of the few minor differences was that an about 400-bp band increased in the strain containing the triple mutation. The relative amount of lacZ mRNA in various strains was determined by densitometric scanning of the most prominent band at 3.1 kb (Table 2). In divE mutant strain SKR319, the steady-state level of lacZ mRNA at 44°C was about 19% of that at 30°C. It was observed that lacZ mRNA at 44°C in the divE mutant recov ered to the same level at 30°C upon the introduction of the rne-1 pnp-7 rnb-500 triple mutation into strain SKR319 (Table 2). These results suggested that one of the major causes of the defect in lacZ gene expression at 44°C in the divE mutant is due to the increased instability of lacZ mRNA.

FIG. 2.

Northern hybridization analysis of lacZ mRNA. Cells were grown to mid-log phase at 30°C. IPTG was then added to the culture, and an aliquot was shifted to 44°C (lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8) while another aliquot was kept at 30°C (lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7). Samples were removed 30 min after the addition of IPTG. Total RNA (5 μg) was electrophoresed on a 1.5% formaldehyde-agarose gel and then blotted onto a nylon membrane. Hybridization was performed at 42°C by using the 300-bp fragment containing the lacZ gene as a probe. Lanes: 1 and 2, SKR207 (wild type); 3 and 4, SKR319 (divE42); 5 and 6, SKR101 (rne-1 pnp-7 rnb-500); 7 and 8, SKR104 (rne-1 pnp-7 rnb-500 divE42). Arrow, position of 3.1-kb lacZ mRNA. A 0.24- to 9.49-kb RNA ladder (GIBCO BRL) was used as a size marker. The values on the left are molecular sizes in kilobases.

TABLE 2.

Inducible synthesis of β-galactosidase and steady-state levels of lacZ mRNA in various divE mutants

| Strain | Genotype

|

Synthesis of β-galactosidaseb

|

mRNA of lacZc

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNase gene(s) | divE | 30°C | 44°C | 44/30°C ratio | 30°C | 44°C | 44/30°C ratio | |

| SKR207 | WTa | WT | 157 | 96 | 0.61 | 100 | 89 | 0.89 |

| SKR319 | WT | divE42 | 129 | 6 | 0.05 | 140 | 26 | 0.19 |

| SKR101 | rne-1 pnp-7 rnb-500 | WT | 319 | 134 | 0.42 | 100 | 136 | 1.36 |

| SKR104 | rne-1 pnp-7 rnb-500 | divE42 | 235 | 114 | 0.49 | 115 | 113 | 0.98 |

| SKR505 | rne-1 | WT | 303 | 63 | 0.21 | 100 | 105 | 1.05 |

| SKR615 | rne-1 | divE42 | 255 | 12 | 0.05 | 90 | 41 | 0.46 |

| SKR913 | pnp-7 | WT | 122 | 185 | 1.52 | 100 | 36 | 0.36 |

| SKR911 | pnp-7 | divE42 | 121 | 91 | 0.75 | 92 | 13 | 0.14 |

| SKR893 | rnb-500 | WT | 365 | 139 | 0.38 | NDd | ||

| SKR894 | rnb-500 | divE42 | 282 | 5 | 0.02 | ND | ||

| SKR712 | rne-1 pnp-7 | WT | 181 | 73 | 0.40 | 100 | 105 | 1.05 |

| SKR711 | rne-1 pnp-7 | divE42 | 232 | 87 | 0.38 | 158 | 275 | 1.74 |

| SKR153 | rne-1 rnb-500 | WT | 159 | 84 | 0.53 | ND | ||

| SKR151 | rne-1 rnb-500 | divE42 | 286 | 14 | 0.05 | ND | ||

WT, wild type for the specified genes.

The value was obtained by dividing the increase in activity by the increase in optical density at 530 nm.

From quantification of Northern blots. divE+ strains cultured at 30°C were given a value of 100.

ND, not determined.

rne-1 mutation stabilized lacZ mRNA in the divE mutant.

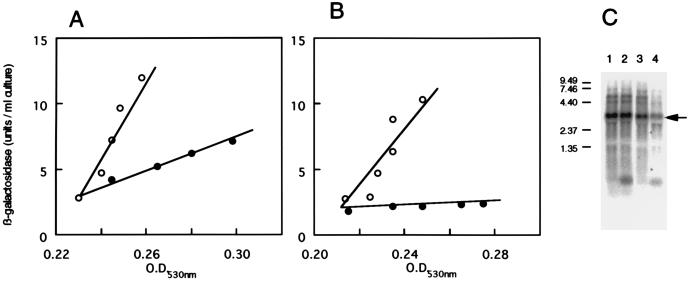

RNase E is known as one of the major processing endoribonucleases (9, 11, 19, 22, 23, 36). It also has a general role in mRNA turnover (4, 21) and affects the stability of specific transcripts in E. coli (3, 6). Yarchuk et al. reported that RNase E participated in the degradation of lacZ mRNA under conditions that interfered with synchronization of transcription and translation in E. coli (39). Thus, we subsequently constructed an isogenic divE mutant containing rne-1. Inducible synthesis of β-galactosidase is shown in Fig. 3, together with the results obtained by Northern hybridization. It appeared that synthesis of β-galactosidase at 44°C was not restored at all by introduction of the rne-1 mutation, whereas the lacZ mRNA level at 44°C in SKR615 (rne-1 divE42) was restored up to about 46% compared to that at 30°C (Fig. 3C and Table 2). These results indicate that for the restoration of lacZ gene expression, it was not enough to stabilize lacZ mRNA by introduction of the rne-1 mutation and that mutation of exoribonuclease genes pnp and/or rnb might have functions other than the stabilization of the lacZ mRNA in the rne-1 pnp-7 rnb-500 triple mutant.

FIG. 3.

lacZ gene expression in the divE mutant containing an rne-1 mutation. Synthesis of β-galactosidase was measured as described in the legend to Fig. 1. A, SKR505 (rne-1); B, SKR615 (rne-1 divE42). Symbols: ○, 30°C; •, 44°C. C, Northern hybridization analysis of lacZ mRNA. For details, see the legend to Fig. 2. Lanes: 1, SKR505, 30°C; 2, SKR505, 44°C; 3, SKR615, 30°C; 4, SKR615, 44°C.

Contribution of other mutant alleles of RNase to the restoration of lacZ gene expression.

To define the minimum set of alleles necessary to restore lacZ gene expression in the divE mutant, we constructed a series of divE mutant strains which carried one or two mutant alleles of the three RNase genes and analyzed the resulting lacZ gene expression (Table 2). There was no mutant allele which completely restored lacZ gene expression by itself. In strain SKR911 (pnp-7 divE42), synthesis of β-galactosidase at 44°C was half of that in the divE+ strain containing the pnp-7 allele (SKR913), while no significant restoration of the level of lacZ mRNA at 44°C was observed in this strain. In SKR711 (rne-1 pnp-7 divE42), β-galactosidase synthesis and the level of lacZ mRNA at 44°C were completely restored, in comparison with SKR712 (rne-1 pnp-7 divE+). Introduction of the rnb-500 mutation or the rnb-500 pnp-7 double mutation into the divE mutant did not contribute to the restoration of β-galactosidase synthesis at 44°C. These results demonstrate that the minimum set of mutant alleles necessary to restore lacZ gene expression was the combination of rne-1 and pnp-7.

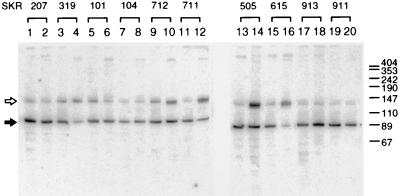

Steady-state levels of tRNA1Ser in various divE mutants.

PNPase and RNase E are RNases which participate in the maturation of tRNA molecules (19, 23, 30). It is reasonable to assume that the mutations of RNases affect not only the stability of the lacZ mRNA but also the stability of the divE gene product, tRNA1Ser, especially in case of ts-tRNA1Ser. We next examined the steady-state level of tRNA1Ser by Northern hybridization. The relative amount of tRNA1Ser was calculated from the density of a band positioned at 88 nt (indicated by a solid arrow in Fig. 4). The amount of wild-type tRNA1Ser was not significantly changed by the temperature shift from 30 to 44°C in all strains (Fig. 4, lanes 1, 2, 5, 6, 9, 10, 13, 14, 17, and 18). In strain SKR319 carrying wild-type RNases, the amount of ts-tRNA1Ser at 44°C was about 25% of that at 30°C (Fig. 4, lanes 3 and 4) and it corresponds to approximately 14% of the amount of wild-type tRNA1Ser in strain SKR207 at 44°C (lanes 2 and 4). Steady-state levels of tRNA were raised by introduction of a pnp-7 mutation into the divE mutant strain (lanes 19 and 20). The amount of ts-tRNA1Ser at 44°C became almost half of the level at 30°C when the pnp-7 (in strain SKR911) and pnp-7 and rne-1 (in strain SKR711) alleles were introduced into the divE mutant (lanes 19 and 20 and lanes 11 and 12, respectively). In strain SKR104 (rne-1 pnp-7 rnb-500 divE42) (lanes 7 and 8), the amount of ts-tRNA1Ser at 44°C was completely recovered, while in SKR615 (rne-1 divE42), the amount of ts-tRNA1Ser at 44°C was not restored at all (lane 16). In strains carrying the rne-1 allele, a band migrating slower than mature tRNA1Ser (indicated by the open arrow) was observed. This ∼130-nt band was detected in all strains but was most abundant in RNase E-deficient strains. This molecule seems to be a precursor species of tRNA1Ser. Ray and Apirion have reported that RNase E participates in the processing events at the 3′ end of the immature tRNA1Ser (30). Our results agree with their observations and indicate that, instead of mature tRNA1Ser, the precursor was produced after the shift to 44°C in rne-1 mutant strains. This precursor molecule seemed to be stable at 44°C, even if it had a base substitution of ts-tRNA1Ser.

FIG. 4.

Northern hybridization analysis of tRNA1Ser. Samples were removed as described for Fig. 2. Total RNA (2 μg) was electrophoresed on an 8% polyacrylamide gel containing 8 M urea and transferred onto a nylon membrane by electroblotting. A 32P-labelled 359-bp fragment carrying the divE gene was used as a probe. Filled arrow, mature tRNA1Ser; open arrow, predicted nonprocessed tRNA1Ser. DNA fragments of pUC18 digested with HapII were used as molecular size standards. Lanes: 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 17, and 19, 30°C; 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, and 20, 44°C. Strains used are shown at the top of the figure. The values on the right are molecular sizes in nucleotides.

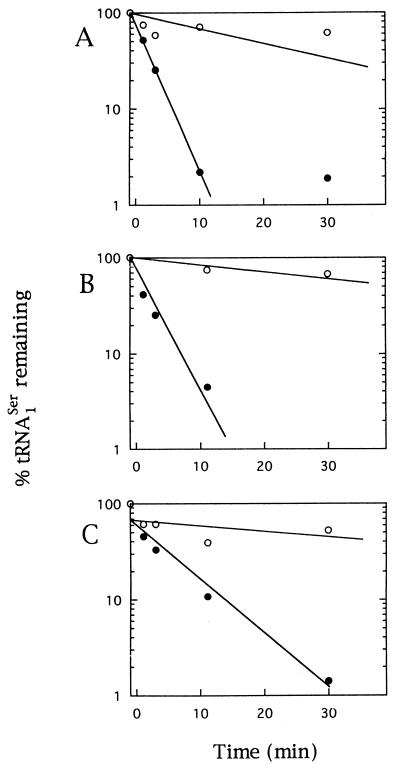

We also examined the stability of tRNA1Ser by Northern hybridization (Fig. 5). The amount of tRNA1Ser was estimated by densitometric scanning of the 88-nt band (data not shown) and plotted against time after addition of rifampin. Wild-type tRNA1Ser was stable at 44°C, as well as at 30°C, and no significant degradation was seen at 30 min after the addition of rifampin (data not shown). The half-life of ts-tRNA1Ser at 30°C was about 20 to 30 min and was not changed by the introduction of either the pnp-7 or rne-1 mutation, whereas ts-tRNA1Ser was degraded immediately after the shift to 44°C in the divE mutant carrying wild-type RNases (half-life, ∼1 min) (Fig. 5A). In the RNase E-deficient divE mutant strain, the degradation of ts-tRNA1Ser progressed similarly at 44°C. On the other hand, in the PNPase-deficient divE mutant strain, ts-tRNA1Ser was stable at 44°C and the half-life at 44°C increased to 4 min. These results indicate that ts-tRNA1Ser is extremely unstable at 44°C and that at least one of the RNases which participate in the degradation of ts-tRNA1Ser at 44°C is PNPase.

FIG. 5.

Degradation of ts-tRNA1Ser in divE mutants carrying various RNase mutations. Cells were grown to mid-log phase at 30°C. Rifampin was then added at 500 μg/ml, and an aliquot was shifted immediately to 44°C. Samples were removed at different time points from the culture at 30°C (○) or the culture at 44°C (•), and RNAs were extracted as described in Materials and Methods. Total RNA (2 μg) was electrophoresed on an 8% polyacrylamide–8 M urea gel and transferred onto a nylon membrane by electroblotting. A 32P-labelled 359-bp fragment carrying the divE gene was used as a probe. The relative amount of mature tRNA1Ser was quantified with a BAS2000 Imaging Analyzer, expressed as a percentage of the value at the time of rifampin addition (time zero), and plotted as a function of time. A, SKR319; B, SKR615; C, SKR911.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we propose that the defect in lacZ gene expression at nonpermissive temperatures was almost completely restored by introducing an rne-1 pnp-7 double mutation into the divE mutant. The rne-1 single mutation restored the steady-state levels of lacZ mRNA at 44°C to up to 46% of that at 30°C, but β-galactosidase synthesis was not restored at all. Introduction of a pnp-7 single mutation resulted in 50% recovery of β-galactosidase synthesis at 44°C compared to that of the isogenic divE+ strain, but the amount of lacZ mRNA was not restored significantly. Northern hybridization analysis of tRNA1Ser demonstrated that ts-tRNA1Ser becomes extremely unstable (half-life, ∼1 min) at 44°C and the pnp-7 mutation, but not the rne-1 and rnb-500 mutations, stabilizes ts-tRNA1Ser. These results indicate that efficient expression of the lacZ gene in the divE mutant can be achieved only when lacZ mRNA, as well as ts-tRNA1Ser, is stabilized by RNase mutations.

From these results, we assume that ts-tRNA1Ser can decode UCA codons but its decoding efficiency is somewhat lower than that of wild-type tRNA1Ser at 44°C. The lacZ gene has eight UCA codons. In the divE mutant, translating ribosomes might stall at one or several UCA codons at 44°C, resulting in desynchronization of transcription and translation. The transcribing RNA polymerase might create naked mRNA behind itself, and if this region has a latent RNase E recognition site, lacZ mRNA might be cleaved, leading to reduced β-galactosidase synthesis.

There have been several reports indicating that synchronization of transcription and translation is an important factor for efficient gene expression in E. coli (1, 4, 10, 16, 18, 20, 33, 39). Yarchuk et al. reported that when the ribosome binding site (RBS) of the lacZ gene was replaced with RBSs from various genes or artificial RBSs, strain-to-strain variation in β-galactosidase synthesis was paralleled by nearly equivalent variations in steady-state levels of lacZ mRNA (39). Moreover, it was demonstrated that inefficient initiation of translation decreased the stability of lacZ mRNA and that RNase E was involved in the rate-limiting step of the degradation of lacZ mRNA. Iost and Dreyfus have shown that the lacZ mRNA transcribed by T7 RNA polymerase yields less β-galactosidase than does that transcribed by E. coli RNA polymerase and that the lower yield reflects its lower stability (13). They proposed that T7 RNA polymerase transcribes the lacZ gene faster than does the E. coli enzyme and that this higher speed unmasks an RNase E cleavage site which is normally shielded by ribosomes (12).

When the ts-tRNA1Ser gene is cloned into a multicopy plasmid and introduced into a divE mutant, expression of the lacZ gene normally occurs at a nonpermissive temperature and it is unnecessary to stabilize lacZ mRNA by use of an rne-1 mutation. The translating ribosomes probably do not stall at UCA codons under these conditions. As reported previously, there are several genes which have UCA codons and whose expression is not affected by a divE mutation (26). According to our model, it is unlikely that there are latent RNase E cleavage sites downstream of the UCA codons in these genes. The translating ribosomes might stall at UCA codons temporarily but could eventually complete translation. Low levels of ts-tRNA1Ser at nonpermissive temperatures seem to be enough to sustain normal levels of translation. Further work is needed to prove this assumption.

As shown in Table 2, the amount of lacZ mRNA was restored by an rne-1 mutation but restoration was not complete. There is a possibility that transcriptional polarity is also one of the causes of lower levels of lacZ gene expression in the divE mutant. Ruteshouser and Richardson reported that the lacZ gene contained several latent transcriptional terminators in its coding region and that transcription terminated at these sites in vivo when the transcript was not properly translated, either by the polar mutation or by amino acid starvation (31).

In this study, we also demonstrated that mutant tRNA1Ser is strikingly unstable at nonpermissive temperatures. The divE42 mutation is a base substitution of A10 for G10 which disrupts one base pairing in the D stem of tRNA1Ser (35). This base pairing seems to be important for the stability of tRNA1Ser. A base substitution of T25 for C25 in the D stem, which restores the A-T base pairing instead of the G-C pair of wild-type tRNA1Ser, is one of the efficient intragenic suppressors of the divE42 mutation (27).

As shown in Fig. 5, introduction of the pnp-7 mutation to the divE mutant increased the stability of ts-tRNA1Ser at 44°C about fourfold. We did not determine the half-life of ts-tRNA1Ser in rne-1 pnp-7 double and rne-1 pnp-7 rnb-500 triple mutants. If mature ts-tRNA1Ser was not synthesized at 44°C in these strains due to the presence of the rne-1 allele, and the half-life was about the same as that in the pnp-7 mutant, the amount of ts-tRNA1Ser remaining 30 min after the temperature shift to 44°C became less than 5% of that at 30°C. However, Northern hybridization analysis showed that the amounts of ts-tRNA1Ser at 44°C in the double and triple mutants were 50 and 100% of that at 30°C, respectively. These results might be explained by the following two possibilities; one is that ts-tRNA1Ser is more stable in these mutants than in the pnp-7 mutant, and the other is that mature ts-tRNA1Ser is synthesized in spite of the presence of the rne-1 mutation.

Northern hybridization analysis showed that in the rne-1 mutant, a band which migrated slower than mature tRNA1Ser accumulated at 44°C. This band, about 130 nt in length, was also detected in the wild-type strain, although the amount was less than that in the rne-1 strain. This species seems to be an unprocessed precursor of mature tRNA1Ser. In contrast to mature ts-tRNA1Ser, it is as stable as the wild-type one at 44°C. From nucleotide sequence data on the divE gene, it is reasonable to assume that the transcription starts 5 bases upstream of the 5′ end of the mature tRNA1Ser and terminates at ρ-independent transcription terminators located downstream of the 3′ end (35). It produces an about 130-nt transcript, which corresponds well to the size of our predicted precursor of tRNA1Ser. Ray and Apirion reported that in a temperature-sensitive rne-3071 mutant, a precursor molecule of tRNA1Ser accumulated which had eight and five extra nucleotides at the 5′ and 3′ ends of mature tRNA1Ser, respectively (30). We have no explanation for the disparity between these observations and our results, but it may be due to the difference in genetic background between the strains used. In connection with this, it is worth mentioning that the strains used in this study have a one-base deletion in the rph gene encoding RNase PH, which is also known as one of the RNases involved in the maturation of tRNA (15).

It has been reported that divE mutant cells exposed to 42°C, when returned to permissive temperatures, started to grow and divide synchronously (25). This indicates that divE mutant cells arrested at a specific stage of the cell cycle at nonpermissive temperatures. Work is in progress to determine which gene is primarily involved in this step and whether the same regulatory mechanism is involved in this case as in that of the lacZ gene.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Sidney R. Kushner for helpful information, as well as for the donation of a series of RNase-deficient strains. We also thank Takashi Sato for the divE mutant strains and C. Wada for λ467.

This work was supported in part by a grant-in-aid from the Science Research Promotion Fund, Japan Private School Promotion Foundation, and by a project research grant from Kyorin University.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adhya S, Gottesman M. Control of transcription termination. Annu Rev Biochem. 1979;47:967–996. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.47.070178.004535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aiba H, Adhya S, de Crombrugghe B. Evidence for two functional gal promoters in intact Escherichia coli cells. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:11905–11910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arraiano C M, Yancey S D, Kushner S R. Stabilization of discrete mRNA breakdown products in ams pnp rnb multiple mutants of Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4625–4633. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.10.4625-4633.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belasco J G. mRNA degradation in prokaryotic cells: an overview. In: Belasco J, Brawerman G, editors. Control of messenger RNA stability. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1993. pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berg D E. Insertion and excision of the transposable kanamycin resistance determinant Tn5. In: Bukhai A I, Shapiro J A, Adhya S L, editors. DNA insertion elements, plasmids and episomes. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1977. pp. 205–212. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cannistraro V J, Subbarao M N, Kennell D. Specific endonucleolytic cleavage sites for decay of Escherichia coli mRNA. J Mol Biol. 1986;192:257–271. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90363-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Bruijin F J, Ausubel F M. The cloning and transposon Tn5 mutagenesis of the glnA region of Klebsiella pneumoniae: identification of glnR, a gene involved in the regulation of the nif and hut operons. Mol Gen Genet. 1981;183:289–297. doi: 10.1007/BF00270631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donovan W P, Kushner S R. Polynucleotide phosphorylase and ribonuclease II are required for cell viability and mRNA turnover in Escherichia coli K-12. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:120–124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.1.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faubladier M, Cam K, Bouche J-P. Escherichia coli cell division inhibitor DicF-RNA of the dicB operon. J Mol Biol. 1990;212:461–471. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90325-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Folley L S, Yarus M. Codon contexts from weakly expressed genes reduce expression in vivo. J Mol Biol. 1989;209:359–378. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghora B K, Apirion D. Structural analysis and in vitro processing to p5 rRNA of a 9S RNA molecule isolated from an rne mutant of E. coli. Cell. 1978;15:1055–1066. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90289-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iost I, Guillerez J, Dreyfus M. Bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase travels far ahead of ribosomes in vivo. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:619–622. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.2.619-622.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iost I, Dreyfus M. The stability of Escherichia coli lacZ mRNA depends upon the simultaneity of its synthesis and translation. EMBO J. 1995;14:3252–3261. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07328.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishikura H, Yamada Y, Nishimura S. Structure of serine tRNAs with different codon responses. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1971;228:471–481. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(71)90052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jensen K F. The Escherichia coli K-12 “wild types” W3110 and MG1655 have an rph frameshift mutation that leads to pyrimidine starvation due to low pyrE expression levels. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3401–3407. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.11.3401-3407.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kennel D E. The instability of messenger RNA in bacteria. In: Reznikoff W S, Gold L, editors. Maximizing gene expression. Stoneham, Mass: Butterworths; 1986. pp. 101–142. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. p. 440. [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCormick J R, Zengel J M, Lindahl L. Correlation of translation efficiency with the decay of lacZ mRNA in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1994;239:608–622. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Misra T K, Apirion D. RNase E, an RNA processing enzyme from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:11154–11159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morse D E, Yanofsky C. Polarity and the degradation of mRNA. Nature. 1969;224:329–331. doi: 10.1038/224329a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mudd E A, Krisch H M, Higgins C F. RNase E, an endoribonuclease, has a general role in the chemical decay of Escherichia coli mRNA: evidence that rne and ams are the same genetic locus. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:2127–2135. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mudd E A, Prentki P, Belin D, Krisch H M. Processing of unstable bacteriophage T4 gene 32 mRNAs into a stable species requires Escherichia coli ribonuclease E. EMBO J. 1988;7:3601–3607. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03238.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nicholson A W. Escherichia coli ribonucleases: paradigms for understanding cellular RNA metabolism and regulation. In: D’Alessio G, Riordan J F, editors. Ribonucleases: structures and functions. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1997. pp. 2–38. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohki M, Mitsui H. Defective membrane synthesis in an E. coli mutant. Nature. 1974;252:64–66. doi: 10.1038/252064a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohki M. The cell cycle-dependent synthesis of envelope proteins in Escherichia coli. In: Inouye M, editor. Bacterial outer membranes: biogenesis and functions. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1979. pp. 293–315. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohki M, Sato S. Regulation of expression of lac operon by a novel function essential for cell growth. Nature. 1975;253:654–656. doi: 10.1038/253654a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohki, M., and F. Hosoda. Personal communication.

- 28.Ono M, Kuwano M. A conditional lethal mutation in an Escherichia coli strain with a longer chemical lifetime of messenger RNA. J Mol Biol. 1979;129:343–357. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(79)90500-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pardee A B, Jacob F, Monod J. The genetic control and cytoplasmic expression of “inducibility” in the synthesis of β-galactosidase by E. coli. J Mol Biol. 1959;1:165. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ray B K, Apirion D. RNAase P dependent on RNAase E action in processing monomeric RNA precursors that accumulate in an RNAase E− mutant of Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1981;149:599–617. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90349-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ruteshouser E C, Richardson J P. Identification and characterization of transcription termination sites in the Escherichia coli lacZ gene. J Mol Biol. 1989;208:23–43. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90085-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sato T, Ohki M, Yura T, Ito K. Genetic studies of an Escherichia coli K-12 temperature-sensitive mutant defective in membrane protein synthesis. J Bacteriol. 1979;138:305–313. doi: 10.1128/jb.138.2.305-313.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stanssens P, Remaut E, Fiers W. Inefficient translation initiation causes premature transcription termination in the lacZ gene. Cell. 1986;44:711–718. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90837-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steege D A, Horabin J I. Temperature-inducible amber suppressor: construction of plasmids containing the Escherichia coli serU− (supD−) gene under control of the bacteriophage lambda pL promoter. J Bacteriol. 1983;155:1417–1425. doi: 10.1128/jb.155.3.1417-1425.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tamura F, Nishimura S, Ohki M. The E. coli divE mutation, which differentially inhibits synthesis of certain proteins, is in tRNA1Ser. EMBO J. 1984;3:1103–1107. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb01936.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tomcsányi T, Apirion D. Processing enzyme ribonuclease E specifically cleaves RNA I: an inhibitor of primer formation in plasmid DNA synthesis. J Mol Biol. 1985;185:713–720. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamada Y, Ishikura H. Suppression of the serT42 mutation with modified tRNA1Ser and tRNA5Ser genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:3124–3130. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.15.3124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamato I, Anraku Y, Ohki M. A pleiotropic defect of membrane synthesis in a thermosensitive mutant ts C42 of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:8584–8589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yarchuk O, Jacques N, Guillerez J, Dreyfus M. Interdependence of translation, transcription and mRNA degradation in the lacZ gene. J Mol Biol. 1992;226:581–596. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90617-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]