Abstract

The Spiritual Care Guide in Hospice∙Palliative Care is evidence-based and focuses on the universal and integral aspects of human spirituality—such as meaning and purpose, interconnectedness, and transcendence—which go beyond any specific religion. This guide was crafted to improve the spiritual well-being of adult patients aged 19 and older, as well as their families, who are receiving end-of-life care. The provision of spiritual care in hospice and palliative settings aims to assist patients and their families in finding life’s meaning and purpose, restoring love and relationships, and helping them come to terms with death while maintaining hope. It is recommended that spiritual needs and the interventions provided are periodically reassessed and evaluated, with the findings recorded. Additionally, hospice and palliative care teams are encouraged to pursue ongoing education and training in spiritual care. Although challenges exist in universally applying this guide across all hospice and palliative care organizations in Korea—due to varying resources and the specific environments of medical institutions—it is significant that the Korean Society for Hospice and Palliative Care has introduced a spiritual care guide poised to enhance the spiritual well-being and quality of care for hospice and palliative care patients.

Keywords: Spirituality, Hospice care, Palliative care, Education

INTRODUCTION

The purpose of hospice and palliative care is to relieve the physical, psychological, social, and spiritual distress of patients who are approaching the end of their lives, as well as that of their families, ultimately enhancing their quality of life [1]. Specifically, providing spiritual support to patients during end-of-life care has been shown to have markedly positive effects on a range of health outcomes. These include spiritual well-being, overall quality of life, adaptability, physical health, and reductions in depression and anxiety. Additionally, it contributes to increased satisfaction with care, improved social connections, and more informed end-of-life decision-making [2-4]. Therefore, spiritual care is a vital element of hospice and palliative care, significantly influencing the quality of the care provided [5].

However, previous research has found that hospice and palliative care teams (HPCTs) frequently experience a sense of burden when it comes to providing spiritual care, finding it challenging to fulfill the spiritual needs of patients. This challenge is partly due to a common misconception that equates spiritual care with religious care [2,6]. A comparative study examining the expectations of spiritual care among individuals approaching the end of life and their families within Korean culture, as well as the perceptions of HPCTs, found that patients and families placed greater importance on non-religious needs such as empathetic listening, fostering hope, and the pursuit of relationships and meaning. However, HPCTs often mistakenly interpret these needs as requests for religious care [7,8]. These findings suggest that a more fitting approach to spiritual care should focus on the fundamental and universal elements of human spirituality, including meaning and purpose, interconnectedness, and transcendence, while also considering the patient’s religious beliefs.

Spirituality is a dynamic and essential aspect of humanity, encompassing the search for ultimate meaning, purpose in life, transcendence, and relationships with oneself, family, significant others, community, nature, and a divine presence or deity. It manifests in the form of beliefs, values, traditions, and practices [5]. Consequently, spiritual care that addresses the needs of patients and their families [9-11] should be integrated into hospice and palliative care practices.

This spiritual care guide was developed with the aim of creating a spiritual care manual that reflects the fundamental and universal aspects of human spirituality for use in end-of-life care settings. It is organized with the following objectives and methods:

Development Objective 1: Identify the scientific evidence pertaining to spiritual care grounded in spirituality by conducting a literature review of international guidelines and other relevant literature [4,8,12-20]. Additionally, following the completion of the Interprofessional Spiritual Care Education Curriculum (ISPEC) Train-the-Trainer course by some members of the development team, a self-education program for the remaining team members was conducted, covering six modules of the ISPEC curriculum across three sessions.

Development Objective 2: Compose spiritual care content that is culturally appropriate for Korea. Preliminary research [6,7] involved HPCTs working in Korean hospice and palliative care settings, as well as with patients and their families, to gain insights into their perceptions of and needs for spiritual care. Drawing on international guidelines, educational courses, and initial studies on spiritual care for terminally ill patients and their families, a draft guide for spiritual care in hospice and palliative care, customized for Korean culture, was developed.

Development Objective 3: Provide a spiritual care guide for use in end-of-life care. A three-round Delphi survey was conducted with 15 expert panelists from HPCTs, comprising three physicians, three chaplains, six nurses, and three social workers. Based on the survey results, a workshop was organized to engage directors from the Korean Society for Hospice and Palliative Care and three representatives from various religious organizations. The purpose was to achieve consensus on the terminology, recommended interventions, and overall content of the “Spiritual Care Guide in Hospice and Palliative Care.”

The complete content of the “Spiritual Care Guide in Hospice∙Palliative Care” can be downloaded from the website of the National Hospice Center (https://hospice.go.kr) and the Journal of Hospice and Palliative Care at https://www.e-jhpc.org/main.html [21].

SPIRITUAL CARE GUIDE IN HOSPICE∙PALLIATIVE CARE

1. Basic concepts of spiritual care

The foundational concepts of spiritual care presented in the “Spiritual Care Guideline in Hospice and Palliative Care” are delineated by integrating the definitions from the fourth edition of the American National Consensus Project (NCP) for Quality Palliative Care’s spiritual care guidelines [14], supplemented by other international literature [22,23], and adapted to reflect Korean cultural nuances [6,7]. From the NCP’s five domains of spiritual care, a total of eight key concepts were identified. These encompass five concepts: spirituality, religiosity, spiritual needs, spiritual needs assessment (which includes screening, history, and assessment), and the role of spiritual caregivers. The remaining three concepts—spiritual care, religious care, and spiritual well-being—were specifically tailored to align with the Korean cultural context [21].

2. Principles of spiritual care

The principles of spiritual care encompass missions, goals, and standards. The three primary goals align with the attributes of spirituality, which include meaning and purpose, interconnectedness, and transcendence [4,18,22-24]. These standards have been customized for the Korean hospice and palliative care context. Notably, standards 4 and 5 incorporate the growing focus on education and training, alongside community partnerships, as integral elements of spiritual care strategies [25]. Details of these five standards are presented in reference [22] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Spiritual Care Principles.

| Principles | |

|---|---|

| Mission | 1. Spiritual care is an essential area of hospice and palliative care that helps patients and families explore meaning and value. 2. Hospice and palliative care teams aim for a universal and integral human spirituality through an evidence-based approach that transcends any particular religion. |

| Goals | 1. Help patients and families find meaning and purpose in life. 2. Help patients and families restore love and relationships. 3. Help patients and families accept death and have hope. |

| Standards | Standard 1 (related to spiritual care) Standard 2 (related to spiritual needs assessment) Standard 3 (related to spiritual intervention) Standard 4 (related to spiritual care education and professionals) Standard 5 (related to community engagement) |

3. Spiritual care model

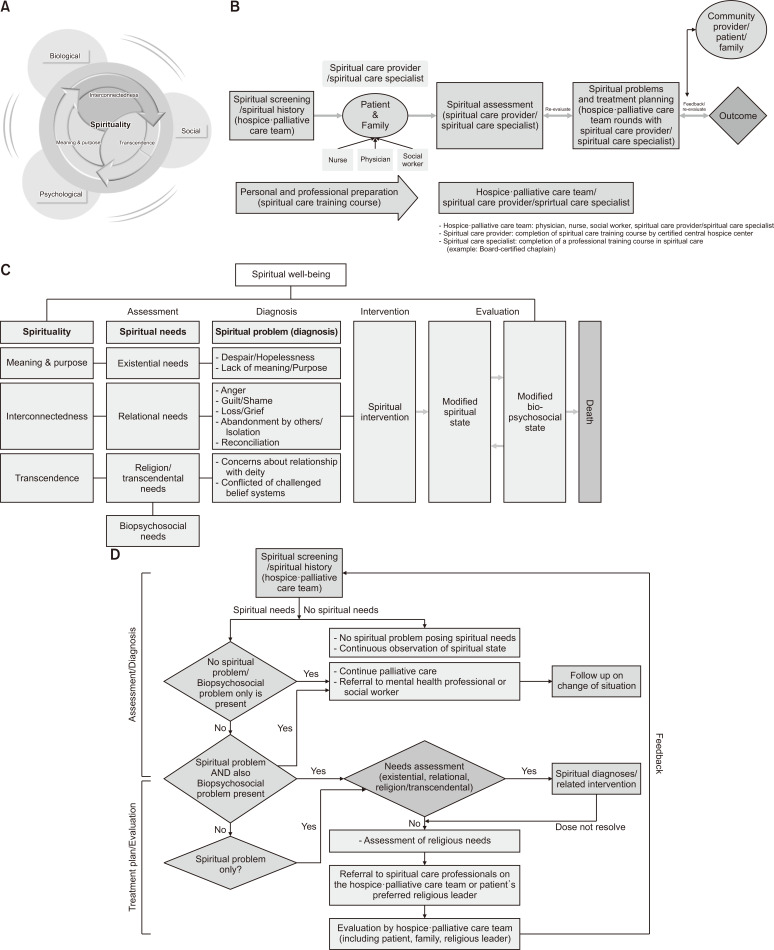

A “totality of human being” model has been introduced to guide spiritual care in hospice and palliative settings, aiming for comprehensive and holistic care. This model is based on the core elements of human spirituality, which include meaning and purpose, interconnectedness, and transcendence [4,18,22-24,26].

The “Spiritual Care Implementation Process 1” delineates the comprehensive sequence from initiation to conclusion. Adapted from the “Inpatient Spiritual Care Implementation Model” developed by Puchalski et al. [27], this model has been customized to align with Korean culture and is advocated for application in community hospices and specialized facilities. The procedure commences with members of the HPCT performing spiritual screenings and historical inquiries with patients and their families, which is succeeded by a thorough spiritual assessment. As a result, spiritual problems are identified, and intervention plans are devised. Subsequently, the results are appraised, and feedback is utilized to facilitate periodic reassessments. Thus, this process ought to incorporate the viewpoints of the patients, their families, and any community religious leaders they opt to include.

The “Spiritual Care Implementation Process 2” categorizes spiritual needs based on the three attributes of spirituality, identifying nine spiritual problems associated with existential, relational, and religious/transcendental needs. It then guides the establishment and implementation of plans for spiritual interventions tailored to these identified problems. Such interventions have the potential to enhance spiritual, physical, psychological, and social well-being. The overarching aim of spiritual care is to foster improved spiritual well-being up to the point of death.

The “Spiritual Care Implementation Process 3” is a revised and supplemented version of the models presented in this guide (Figure 1), drawing upon the spiritual diagnosis decision pathways model by Puchalski et al. [27]. This model is designed to identify spiritual problems by assessing three spiritual attributes. Specifically, it delineates the spectrum of spiritual care that the HPCT can offer, which includes the planning and execution of spiritual interventions to address existential, relational, and religious/transcendental needs. If spiritual problems persist despite the HPCT’s interventions, or if patients and their families express particular religious care needs, the model includes a referral process to spiritual care specialists within the HPCT or to external religious leaders [21]. In such instances, the HPCT will facilitate a referral to a religious leader chosen by the patient for their religious care [21].

Figure 1.

Spiritual care model. (A) The totality of humanity, (B) Spiritual implementation model 1, (C) Spiritual implementation model 2, (D) Spiritual implementation model 3.

Source A: Kang KA, Kim SJ, Kim DB, Park MH, Yoon SJ, Choi SE, et al. A meaning-centered spiritual care training program for hospice palliative care teams in South Korea: development and preliminary evaluation. BMC Palliative Care 2021;20;30.

Source B, D: Puchalski C, Ferrell B, Virani R, Otis-Green S, Baird P, Bull J, et al. Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: the report of the Consensus Conference. J Palliat Med 2009;12:885-904.

4. Spiritual care process

The spiritual care process includes a spiritual needs assessment, a spirituality-based care continuum, a form for spiritual care records, and recommended spiritual interventions. In addition, the appendix presents cases of spiritual needs, spiritual problems (diagnosis), and spiritual strengths, assisting the HPCT in the practical application of spiritual care [21].

Spiritual needs are categorized according to the attributes of human spirituality. The three stages of assessing spiritual needs go beyond merely determining whether a patient is religious. This process entails comprehending the underlying reasons or motivations that imbue a patient’s life with meaning—asking, “What makes your life meaningful?” It also involves discerning what provides the patient with inner strength and comfort, prompting the question, “What gives you strength and comfort?” [1,28] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Three Steps of Assessing Spiritual Needs.

| Division | Purpose | When | Who |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spiritual screening | Check spiritual care needs (yes/no) | First visit | Hospice and palliative care team |

| Spiritual history | Based on the attributes of spirituality, identify spiritual needs or spiritual strengths (yes/no) | First visit and periodic reassessment | Hospice and palliative care team |

| Spiritual assessment | Identify spiritual strengths related to attributes of spirituality (specific questions) | Initial visit and periodic reassessments | Spiritual-care-provider/spiritual care specialist |

The core of spiritual care and needs assessment lies in assisting patients to recognize their spiritual strengths [14]. Thus, the entire continuum, from assessing spiritual needs to implementing interventions and evaluating outcomes, is designed to affirm and bolster the patient’s spiritual strengths, ultimately fostering spiritual well-being. Existential needs related to “meaning and purpose” encompass two spiritual issues: despair and hopelessness, and a lack of meaning and purpose. Relational needs tied to “interconnectedness” cover five spiritual issues: anger, guilt and shame, loss and grief, feelings of abandonment or isolation, and the need for reconciliation. Lastly, religious and transcendental needs linked to “transcendence” involve two spiritual issues: concerns about one’s relationship with a deity and conflicted or challenged belief systems (Table 2, 3).

Table 3.

Spiritual Needs Assessment (Example)

| Spiritual needs based on spiritual attributes | Questions |

|---|---|

| 1. Existential needs: The need to find purpose and meaning in life | [Spiritual Strengths: The Meaning of Life] • Key Questions - What are the most important purposes (goals), values, and things that matter (or are important) in your life? • Additional Questions - What was the most rewarding (or meaningful, or well-done) thing you've ever done in your life? - What have you done so far, and what has it meant in your life? - What are your favorite traits (strengths) about yourself, and how have they helped you in your recent situation? - Do you have any advice or things you'd like to leave behind for your children or the next person in your life? |

| [Spiritual Strengths: Seeking meaning] • Key Questions - What gives you the strength to endure the current situation? • Additional Questions - When you look back on your life, what do you think it was like? - What was the biggest crisis you've faced in your life, and what gave you the strength to get through it? - What has most influenced your life purpose? - If you lose a part of your body or a bodily function, how will it affect the meaning and purpose of (your) life? - How has your illness changed your life goals? | |

| Spiritual needs, spiritual problems (diagnosis), and spiritual strengths (examples) | |

| Example 2 Underline: Spiritual needs manifestation Italics: Spiritual strengths |

Mr. Pyeon (male/83 years old) received radiation therapy for prostate cancer. Two years later, he was diagnosed with neuroendocrine cancer of the pancreas and was treated with chemotherapy. After the disease progressed and chemotherapy was discontinued, he enrolled in a home hospice program. He had previously worked as a local government employee and had been transferred frequently, so he was often away from his family when raising his two children. He expressed that he had met his wife through an arranged marriage and they lived together, but he has never had a deep conversation with her and does not have much affection for her. He doesn't have much time for hobbies or leisure outside of work, so when he thinks back on his life, he doesn't have many pleasant memories. After being diagnosed with a terminal illness, he expressed that he thought it was right to sacrifice and do his best to raise and feed his family when she was younger, but now he is full of regret and resentment because he has difficulty moving around due to lower extremity edema and is confined to his home and cannot live alone without help from others. "It's so unfair, I thought this was the way I was supposed to live, but now I look back and I don't see myself in my life, I'm just a slave, I'm just a person who's locked up and told what to do. I've never been happy, it feels so unfair that I've lived this way." As his illness progressed and his delirium increased, he became unable to recognize his family members and became aggressive, screaming "Don't lock me up! Open the door!" and became aggressive, wielding a bat, running out of the house and injuring himself. "There are soldiers standing guard over me, keeping an eye on me, making me do things. Please help me." |

| Spiritual needs identified in the case | • Existential needs: the need to find purpose and meaning in life. • Relational needs: the need for love, connection, and harmonious relationships with oneself and significant others. |

| Spiritual problems (Diagnosis) (number: priority) | • Lack of meaning and purpose (①) • Anger (②) • Despair and hopelessness (③) |

| The spiritual strengths of the case (underline the relevant part) | • The meaning of life • Trying to find meaning • Love (altruistic) • Gratitude • Compassion and forgiveness • Belief or faith • Tranquility • Acceptance • Hope for the afterlife |

In addition to basic spiritual interventions (listening, prayer/meditation, companionship, etc.), more specialized approaches like logotherapy, dignity therapy, mindfulness-based interventions, and life graphs are recommended (Table 4). The spiritual care record, designed for documenting and evaluating spirituality, is grounded in the three attributes of spirituality: meaning and purpose, interconnectedness, and transcendence. This tool facilitates the assessment and recording of spiritual diagnoses and interventions (Appendix 1). It is advised that hospice and palliative care institutions adopt this format to enhance the management of spiritual care quality.

Table 4.

Spirituality-based Care Continuum (Example).

| Spirituality property | Spiritual strengths | ⇄ | Spiritual needs based on spirituality attributes | Expressing spiritual needs | Spiritual matters | Intervention goals | Spiritual intervention | Spiritual assessment (6-point scale) | End result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key Aspects | Example | |||||||||

| Meaning and purpose | • Meaning of life • Trying to find meaning • Love • Gratitude • Compassion/Forgiveness • Beliefs or beliefs • Tranquility • Acceptance • Hope for the afterlife |

Existential needs (the need to find purpose and meaning in life) | • No hope for future health and life • State of hopelessness |

• “My life is getting shorter and shorter” • “There is no reason for me to live” • “I don’t want to live” • “I don’t know what lies ahead of me” |

Despair and hopelessness | Finding hope and meaning (Hope) | • Help the patient express their feelings of hopelessness and listen and empathize with them. • Try to have conversations that take the weight of reality off the patient’s shoulders. • Help to find ways to make the patient’s time count. • Find something to do together that will motivate the patient’s (e.g., create a bucket list). |

Regain motivation through hope and finding meaning. | Spiritual well-being | |

| • Lack of meaning • Questions about the meaning of one’s existence • Questions about the meaning of pain • Seeking spiritual help • A sense of futility about one’s life • Falling apart. • desperate attitude • Apathy, indifference, depression, helplessness • Expression of futility • One’s own worthlessness |

• “My life (my life) is meaningless” • “I feel useless” • “What’s the point of living like this?” • “It’s all for nothing” • “I don’t know what the future holds” • “Why do I have to be so sick?” |

Lack of meaning and purpose | Finding hope and meaning (Meaning of suffering) | • Listen when the patient expresses skepticism about the value of life. • Help the patient gain awareness of reality through listening and counseling. • Inform the patient that their life has meaning and purpose. • Provide opportunities for visits by family and friends who are meaningful to the patient. • Confirm that the patient is worthy of care through warm physical support. |

Find hope and rewarding meaning. | |||||

5. Spiritual care personnel

The spiritual care guide underscores the importance of spiritual caregivers and professionals. Members of the HPCT who have completed the online spiritual care course, developed in partnership with the Korean Society for Hospice and Palliative Care and the National Hospice Center, are qualified to act as spiritual caregivers. They are trained to carry out fundamental aspects of spiritual assessment, including screening and explorations of patients’ histories. Consequently, there is a need for a consensus regarding the training and education process to cultivate competent spiritual care professionals. These professionals assist individuals in recognizing their spiritual strengths through a comprehensive spiritual assessment [27].

6. Quality management of spiritual care

The guideline recommends assessing the presence of spiritual care guide, documentation, and satisfaction surveys of bereaved families for the quality management of spiritual care [29].

CONCLUSION

Developing a universally applicable and feasible spiritual care guide for all hospice and palliative care institutions in Korea has been challenging due to the diversity in working conditions and personnel support systems. As an initial version, this guide will necessitate ongoing revisions and enhancements to achieve full applicability in hospice and palliative care practices. The development of this guide will continue through future Delphi surveys and input from regional spiritual care experts, aiming to provide spiritual care that is both culturally attuned to Korean sensibilities and practically implementable. As a result, spiritual care will not only be an integral part of hospice and palliative care institutions but also in medical settings that provide end-of-life care, thereby enhancing the spiritual well-being and quality of life for patients and their families and making a significant contribution to the overall quality of care.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary materials can be found via https://doi.org/10.14475/jhpc.2023.26.4.149.

Funding Statement

Funding/Support This study was supported by the Health Promotion Fund, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (2360110-1).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

AUTHOR’S CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception or design of the work: all authors. Data collection: all authors. Data analysis and interpretation: all authors. Drafting the article: KAK, JC. Critical revision of the article: all authors. Final approval of the version to be published: KAK, JC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Balboni TA, Fitchett G, Handzo GF, Johnson KS, Koenig HG, Pargament KI, et al. State of the science of spirituality and palliative care research part II: screening, assessment, and interventions. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;54:441–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cherny NI, Fallon MT, Kaasa S, et al. Oxford textbook of palliative medicine. 5th ed. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Groot M, Ebenau AF, Koning H, Visser A, Leget C, van Laarhoven HWM, et al. Spiritual care by nurses in curative cancer care: protocol for a national, multicentre, mixed method study. J Adv Nurs. 2017;73:2201–7. doi: 10.1111/jan.13332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoosen M, Roman NV, Mthembu TG. The development of guidelines for the inclusion of spirituality and spiritual care in unani tibb practice in South Africa: a study protocol. J Relig Health. 2022;61:1261–81. doi: 10.1007/s10943-020-01105-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jafari N, Farajzadegan Z, Zamani A, Bahrami F, Emami H, Loghmani A. Spiritual well-being and quality of life in Iranian women with breast cancer undergoing radiation therapy. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:1219–25. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1650-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kang KA, Choi YS. Comparison of the spiritual needs of terminal cancer patients and their primary family caregivers. Korean J Hosp Palliat Care. 2020;23:55–70. doi: 10.14475/kjhpc.2020.23.2.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kang KA, Kim SJ. Comparison of perceptions of spiritual care among patients with life-threatening cancer, primary family caregivers and hospice/palliative care nurses in South Korea. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2020;22:532–51. doi: 10.1097/NJH.0000000000000697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moosavi S, Borhani F, Akbari ME, Sanee N, Rohani C. Recommendations for spiritual care in cancer patients: a clinical practice guideline for oncology nurses in Iran. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28:5381–95. doi: 10.1007/s00520-020-05390-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.NHS, author. Standards for spiritual care services in the NHS in Wales [Internet] National Health Service; London: 2009. [cited 2023 Oct 28]. Available from: http://www.wales.nhs.uk . [Google Scholar]

- 10.Puchalski CM, Vitillo R, Hull SK, Reller N. Improving the spiritual dimension of whole person care: reaching national and international consensus. J Palliat Med. 2014;17:642–56. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2014.9427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salsman JM, Pustejovsky JE, Jim HS, Munoz AR, Merluzzi TV, George L, et al. A meta-analytic approach to examining the correlation between religion/spirituality and mental health in cancer. Cancer. 2015;121:3769–78. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spiritual Health Association, author. Guidelines for quality spiritual care in health. Spiritual Health Association; Melbourne: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agora Spiritual Care Guideline Working Group, author. Spiritual Care: National Guideline. version: 1.0. Oncoline. Integraal Kankercentrum Noord-Nederland; Groningen: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care, author. Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care, 4th ed [Internet] National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care; Richmond, VA: 2018. [cited 2023 Oct 28]. Available from: https://www.nationalcoalitionhpc.org/ncp . [Google Scholar]

- 15.American National Red Cross, author. Disaster spiritual care standards and procedures, disaster cycle services standards and procedures, DCS SP Respond. American National Red Cross; [Washington]: c2015. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nolan S, Saltmarsh P, Leget C. Spiritual care in palliative care: working towards and EAPC Task Force. European J Palliat Care. 2011;18:86–9. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spiritual Health Association, author. Guidelines for quality spiritual care in health. Spiritual Health Association; Melbourne: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooper D, Barnes P, Horst G. How spiritual care practitioners provide care In Canadian hospice palliative care settings: Recommended advanced practice guidelines and commentary. Spiritual Advisors Interest Group, Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association; Ottawa: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Providence Health and Services, author. Standards of excellence for spiritual care [Internet] National Association of Catholic Chaplains; Milwaukee, WI: 2007. [cited 2023 Oct 28]. Available from: https://www.nacc.org . [Google Scholar]

- 20.University of Hull, author; Staffordshire and Aberdeen, author. Spiritual care at the end of life: a systematic review of the literature. London, SE; Department of Health: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Korean Society for Hospice and Palliative Care, author. Spiritual care guideline in hospice∙palliative care. Seoul; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braam AW. Towards a multidisciplinary guideline religiousness, spirituality, and psychiatry: what do we need? Mental Health, Religion & Culture. 2017;20:579–88. doi: 10.1080/13674676.2017.1377949. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freire J, Moleiro C. Religiosity, Spirituality, and Mental Health in Portugal: a call for a conceptualization, relationship, and guidelines for integration (a theoretical review) Psicologia. 2015;29:17–32. doi: 10.17575/rpsicol.v29i2.1006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moreira-Almeida A, Koenig HG, Lucchetti G. Clinical implications of spirituality to mental health: review of evidence and practical guidelines. Braz J Psychiatry. 2014;36:176–82. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2013-1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Health Service, author. Spiritual care strategy 2023-2026. NHS Golden Jubilee; Clydebank: 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kang KA, Kim SJ, Kim DB, Park MH, Yoon SJ, Choi SE, et al. A meaning-centered spiritual care training program for hospice palliative care teams in South Korea: development and preliminary evaluation. BMC Palliative Care. 2021;20:30. doi: 10.1186/s12904-021-00718-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puchalski C, Ferrell B, Virani R, Otis-Green S, Baird P, Bull J, et al. Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: the report of the Consensus Conference. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:885–904. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taylor EJ. Chapter 34. Spiritual screening, history, and assessment. In: Ferrell BR, Paice JA, editors. Oxford textbook of palliative nursing. 5th ed. Oxford University Press; New York: 2019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park JK. Reflections and implications of the hospice quality outcomes reporting program (HQRP) in the United States. HIRA Policy Brief. 2017;11:63–74. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.