Abstract

Even though there is a large body of information concerning the harmful effects of alcohol on different organisms, the mechanism(s) that affects developmental programs, at a single-cell level, has not been clearly identified. In this respect, the spore-forming bacterium Bacillus subtilis constitutes an excellent model to study universal questions of cell fate, cell differentiation, and morphogenesis. Here, we demonstrate that treatment with subinhibitory concentrations of alcohol that did not affect vegetative growth inhibited the initiation of spore development through a selective blockage of key developmental genes under the control of the master transcription factor Spo0A∼P. Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside-directed expression of a phosphorylation-independent form of Spo0A (Sad67) and the use of an in vivo mini-Tn10 insertional library permitted the identification of the developmental SinR repressor and RapA phosphatase as the effectors that mediated the inhibitory effect of alcohol on spore morphogenesis. A double rapA sinR mutant strain was completely resistant to the inhibitory effects of different-C-length alcohols on sporulation, indicating that the two cell fate determinants were the main or unique regulators responsible for the spo0 phenotype of wild-type cells in the presence of alcohol. Furthermore, treatment with alcohol produced a significant induction of rapA and sinR, while the stationary-phase induction of sinI, which codes for a SinR inhibitor, was completely turned off by alcohol. As a result, a dramatic repression of spo0A and the genes under its control occurred soon after alcohol addition, inhibiting the onset of sporulation and permitting the evaluation of alternative pathways required for cellular survival.

Spore morphogenesis in the soil bacterium Bacillus subtilis constitutes an excellent model to study the signals and the triggered events that govern the metamorphosis of a growing cell into a dormant cell (35, 41). Effectively, to survive under extreme environmental conditions and to cope with indefinite periods of starvation, B. subtilis possesses the ability to differentiate into highly resistant spores (9, 34). At the onset of sporulation, cells divide asymmetrically into a large compartment (the mother cell) and a small compartment (the forespore) which are joined at the division septum. The polar division triggers cell-type-specific gene expression, first in the forespore and then in the mother cell (1, 35, 41).

The temporal and spatial cell-type-specific gene expression in the developing sporangium (mother cell plus forespore) is achieved by regulation of a cascade of four RNA polymerase sigma factors: σF, σE, σG, and σK. At each stage of sporulation, the induction of a specific σ factor depends on a signal transduced through the double membrane of the prespore that passes back and forth by a process of dubbed crisscross regulation. Evidently, the decision to abandon vegetative growth to form a dormant spore must be finely balanced. If cells fail to sporulate before conditions become too severe, they may perish. On the other hand, if cells sporulate while adaptation and resumption of growth are still possible, they lose the opportunity to propagate and may be overrun by other organisms in the environment.

Then, how is the onset of sporulation regulated? The cellular level of the phosphorylated Spo0A transcription factor generated by the phosphorelay signal transduction system regulates initiation of sporulation (6, 11). The phosphorelay is a more sophisticated version of the classical two-component signal transduction system originally described for bacteria but later also found in fungi and plants (7). Five histidine kinases, KinA to KinE, in response to different stimuli, activate the system through autophosphorylation and transference of the phosphoryl group to the intermediate response regulator Spo0F. By means of the Spo0B phosphotransferase, the phosphoryl group is then transferred from Spo0F∼P to the Spo0A response regulator. Regulation of the Spo0A phosphorylation level occurs by a combination of the transcription control (mediated by the repressors AbrB, SinR, and Hpr) of key components of the phosphorelay and the regulation of the flow of phosphate through a regulatory cascade that involves the five KinA to KinE kinases and their regulators and the Rap/Spo0E families of developmental phosphatases (7, 8, 29, 30, 43).

This myriad of negative transcriptional and posttranslational mechanisms that control the onset of sporulation indicates that the phosphorelay also integrates inhibitory signals that ensure that cells do not initiate sporulation unless it is likely that they will be able to complete the process successfully (developmental checkpoints) (8, 13, 28). In this respect, the seminal work of Bohin et al. showed long ago that addition of subinhibitory concentrations of short-chain aliphatic alcohols ranging from C1 to C4 (methanol, ethanol, propanol, or butanol) to exponentially growing B. subtilis cells reduced the growth rate without affecting the final yield (4). Intriguingly, a more dramatic deleterious effect than the one observed on vegetative growth was perceived when the differentiation of vegetative cells into dormant spores was analyzed (4, 15). The efficiency of spore formation in cultures grown in the presence of alcohol concentrations that did not affect vegetative growth was reduced more than 100-fold. The period of sensitivity for the capacity to make spores was found to begin at around 45 min and to end 90 min after the commencement of stationary phase (T0). However, the toxic effect of alcohol was detected by electron microscopy only at T2 to T3, when septation fails to occur in the majority of cells, while a remaining minority of cells showed multiple and abnormal septation (4). Ng et al. and Bohin and Lubochinsky showed that specific suppressors of Spo0 mutations in either rpoD, encoding σA (crsA47), or the spo0A gene itself (rvtA11 and ssa) also blocked the ethanol sensitivity of sporulation (3, 27). However, a functional link between the identified suppressors and the detrimental effect of alcohol on sporulation was not found and the specific target of alcohol that interrupted the development of the spore remained unknown (3, 4, 15, 27).

In the present work we reexamined this old enigma of the molecular basis of the detrimental effects of subinhibitory concentrations of ethanol (alcohol stress) on the development of the morphogenetic program of B. subtilis differentiation. Our findings indicate that the deleterious effects of alcohol on sporulation are due to an alcohol-triggered pathway involving the SinR and RapA developmental regulators, which directly control (i) the activity of the phosphorelay and hence the phosphorylation level of Spo0A (RapA effect) and (ii) the transcription of early key components of the sporulation program (SinR effect).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and growth conditions.

The B. subtilis strains used in this study are derived from JH642 and are described in Table 1. For the described experiments, B. subtilis was propagated in Luria-Bertani broth (LB medium) or in Schaeffer's sporulation medium (SSM) (1) as indicated. Antibiotics were added to the media at the following concentrations for B. subtilis: 5 μg/ml, chloramphenicol; 2 μg/ml, kanamycin; 50 μg/ml, spectinomycin; 20 μg/ml, tetracycline; 0.5 μg/ml, erythromycin; and 7 μg/ml, neomycin. For determination of sporulation efficiency, ethanol-treated and nontreated cultures of B. subtilis were grown in SSM for 20 h and then serial dilutions were plated on solid SSM or LB before and after treatment with CHCl3 (10% for 15 min) (1). β-Galactosidase activity in B. subtilis strains harboring lacZ fusions were assayed as described previously, and the specific activity is expressed in Miller units (1). The spore counting and β-galactosidase experiments for which results are shown in the figures were independently repeated five times, and a representative or average set of results is showed in each case. For alcohol treatment, prewarmed ethanol was added at the time indicated for each experiment at a final concentration ranging from 0.7 to 0.8 M, as indicated.

TABLE 1.

B. subtilis strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Source and/or reference |

|---|---|---|

| JH642 | trpC2 pheAI | Laboratory stock |

| JH12834 | ΔrapA::Tn917 ery | M. Perego |

| JH12981 | amyE::rapA-lacZ kan | M. Perego |

| JH16102 | amyE::kinB-lacZ cat | V. Dartois |

| JH16480 | amyE::spollE-lacZ cat | Laboratory stock (1) |

| JH16124 | amyE::spoIIA-lacZ cat | Laboratory stock (1) |

| JH16182 | amyE::spoIIG-lacZ cat | Laboratory stock (1) |

| JH16304 | amyE::spoIIG-lacZ kan | Laboratory stock (1) |

| JH19000 | amyE::kinA-lacZ cat | Laboratory stock (41) |

| JH19004 | amyE::spo0F-lacZ cat | Laboratory stock (41) |

| JH19003 | amyE::spo0B-lacZ cat | Laboratory stock (41) |

| JH19005 | amyE::spo0A-lacZ cat | Laboratory stock (41) |

| JH19087 | ΔkinA::spc | Laboratory stock (41) |

| JH19980 | ΔkinB::tet | Laboratory stock (41) |

| Sik83 | amyE::P-spac-sad67 cat spollA-lacZΩIIA ery | Laboratory stock (A. Grossman) |

| RG2051 | amyE::spoIIQ-lacZ cat | MO2051 (P. Stragier) → JH642 |

| RG1679 | amyE::spoIID-lacZ cat | MO1679 (P. Stragier) → JH642 |

| RG19990 | ΔkinA::spc ΔkinB::tet | JH19087 → JH19980 |

| RG286 | amyE::sigB-lacZ cat | PB286 (C. Price) → JH642 |

| RG198 | amyE::ctc-lacZ cat | PB198 (C. Price) → JH642 |

| RG1114 | spoIIEΩIIE neo | KI1114 (A. Grossman) → JH642 |

| RG163 | amyE::spoIIG-lacZ kan sigB::cat | PB153 (C. Price) → JH16304 |

| RG1261 | amyE::spoIIQ-lacZ cat thr::P-spac-spoIIAC kan | MO1261 (P. Stragier) → RG2051 |

| RG19 | sinR::mini-Tn10 spc | This study |

| RG23 | rapA::mini-Tn10 spc | This study |

| RG432 | ΔsinR::cat | IS432 (I. Smith) → JH642 |

| RG433 | ΔsinR::cat ΔrapA::Tn917 ery | JH12834 → RG432 |

| RG1400 | amyE::spoIIG-lacZ kan ΔrapA::Tn917 ery | JH12834 → JH16304 |

| RG1401 | amyE::spoIIG-lacZ kan ΔsinR::cat | IS432 (I. Smith) → JH16304 |

| RG1402 | amyE::spoIIG-lacZ kan ΔsinR::cat ΔrapA::Tn917 ery | JH16304 → RG433 |

| RG12982 | amyE::rapA-lacZ kan Δspo0A::ery | Sik31 (I. Smith) → JH12961 |

| RG12983 | amyE::rapA-lacZ kan ΔcomA::ery | MB221 (A. Sonenshein) → JH12961 |

| RG437 | amyE::sinI-lacZ cat | IS437 (I. Smith) → JH642 |

| RG438 | amyE::sinR-lacZ cat | IS438 (I. Smith) → JH642 |

| RG439 | amyE::sinI-lacZ cat hprΩpMTL20EC ery | SS62 (T. Leighton) → RG437 |

Immunoblot analysis.

B. subtilis cultures were grown as indicated. Aliquots of 10 ml of each culture were collected by centrifugation and washed three times in disruption buffer (TES [50 mM], NaCl [50 mM], dithiothreitol [5 mM], 10% glycerol, EDTA [1 mM] [pH 7.5], protease inhibitor cocktail [Complete buffer; Boehringer]). Cells were finally resuspended in 0.5 ml of disruption buffer and disrupted by sonication (3 times for 0.5 min) using a model 200 Sonifier (Branson). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation (20 min, 13,000 rpm [Marathon 16 Km; Fisher Scientific] at 4°C). The protein concentration in crude extract was determined by using the Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad). The samples were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in a 12% acrylamide gel, transferred to an Immobilon membrane (Millipore, Billerica, Mass.), and revealed with anti-Spo0A rabbit antibody and an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Bio-Rad). For signal quantification, films were scanned and analyzed densitometrically.

Generation of the mini-Tn10 insertional library enriched in alcohol-resistant transposants.

The mini-Tn10 delivery plasmid pIC333 (40) was generously obtained from Tarek Msadek (Institut Pasteur, Paris, France). This delivery vector (7 kb) has several features that make it the ideal tool to create an in vivo insertional library in B. subtilis (40). Transformation of the reference strain JH642 was done as previously described (1), selecting for Eryr (LB plates plus 0.5 μg of erythromycin/ml) at 28°C.

Fatty acid analysis.

Measurements of fatty acid synthesis by B. subtilis cells were performed as previously described (15, 37). Briefly, strain JH642 was grown in liquid SSM until the late exponential phase (T−1 or T0). Aliquots of these cells (1 ml each) were taken and treated with ethanol (0.7 M) or cerulenin (5 μg/ml) or were nontreated. All the aliquots were immediately exposed to 10 μCi of [14C]acetate or 10μCi of [14C]isoleucine as precursors of de novo radioactive membrane lipids. Incubation was continued until 2 or 3 h after entrance into stationary phase. After this incubation period, lipids were extracted from whole cells as previously described (15, 37). Diacylglycerol (DG) and phospholipid (PL) fractions were separated by thin-layer chromatography on silica gel plates developed in petroleum ether-ether-acetic acid (70:30:2). In this system DGs migrate with the solvent while PLs remain in the origin of the thin-layer plate (15). The radioactive compounds were located by autoradiography and quantified by scintillation counting.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Ethanol inhibits the transcription of Spo0A∼P-dependent developmental genes.

The precise developmental step inhibited by alcohol treatment during the morphogenesis of the spore was not previously identified (3, 27). To answer this unsolved question, we analyzed the effect of ethanol on the expression of temporally and spatially regulated developmental genes of isogenic B. subtilis strains containing sporulation-reporter lacZ fusions. Levels of β-galactosidase activity were measured from cultures grown in the absence or presence of ethanol and used as indications of gene expression from the reporter fusions to developmental promoters under the control of Spo0A∼P, σF, and σE (Fig. 1). In cultures treated with a subinhibitory concentration of ethanol (0.7 M) (4, 15), the expressions of the mother cell and forespore genes spoIID (σE dependent) and spoIIQ (σF dependent) were completely inhibited, confirming for the first time that cell-specific gene expression was blocked by ethanol treatment (Fig. 1A and B). Interestingly, expression of the Spo0A∼P-dependent spoII genes, coding for σF (SpoIIAC), σE (SpoIIGB), and their regulatory proteins (SpoIIAA, SpoIIAB, SpoIIE, and SpoIIGA) was also completely arrested under ethanol stress (Fig. 1C to E). However, expression of the phosphorelay genes that do not require active Spo0A (Spo0A∼P) for their induction (kinA, kinB, and spo0B) showed essentially the same levels of developmental β-galactosidase activity in ethanol-treated or untreated cultures (Fig. 1F to H). On the other hand, the induction of phosphorelay genes that required Spo0A∼P (spo0F and spo0A) was completely turned off in ethanol-treated cells (Fig. 1I to J). These results shed new light on the pioneering work of Bohin et al. almost 30 years ago that showed for the first time the detrimental effect of alcohol on sporulation (4). The new results presented here clearly indicate and demonstrate for the first time that treatment with subinhibitory levels of ethanol blocked the activation and/or the activity of the key regulator Spo0A∼P (Spo0 phenotype, Fig. 1K).

FIG. 1.

Ethanol blocks expression of early Spo0A∼P-dependent developmental genes. (A to J). Cells were grown in liquid SSM, and at the time indicated by the arrow ethanol (0.7 M; 4%) was added to one-half of each culture. Samples of untreated (filled symbols) and ethanol-treated (open symbols) cultures were collected at the indicated times and assayed for β-galactosidase activity, expressed in Miller units (M.U.) (1). Time zero represents the transition from vegetative to stationary phase. The wild-type B. subtilis strains utilized for the experiments, RG1679 (A), RG2051 (B), JH16480 (C), JH16182 (D), JH16124 (E), JH19000 (F), JH16102 (G), JH19003 (H), JH19004 (I), and JH19005 (J), harbored transcriptional β-galactosidase fusions to the sporulation promoters indicated in each panel. Each panel shows the data from a representative experiment done in triplicate. (K) Cartoon interpreting the results shown in panels A to J, indicating that ethanol treatment blocks the onset of spore morphogenesis (stage zero).

Alcohol inhibition of spore development is not due to a specific blockage of the activating pathways of the sensor sporulation kinases.

It was previously suggested that ethanol might block sporulation in B. subtilis through a specific inhibition of the activation pathway of KinA (42). In order to test this proposal, we analyzed the effect of ethanol treatment on the proficiency of making mature spores of different B. subtilis strains harboring mutations in the genes coding for KinA and KinB, the main sensor sporulation kinases present in this bacterium (18). If ethanol inhibition of spore morphogenesis was due to a specific inhibition of KinA (42), a kinA mutant strain should show the same sporulation phenotype in the absence or presence of ethanol. Surprisingly, the effects of ethanol on spore formation of the wild type and kinA and kinB mutant strains were completely different from the ones that should be expected for a specific inhibitor of the activating pathway of KinA. Indeed, ethanol treatment produced a profound decline in the efficiency of spore formation not only of the wild-type strain (kinA+ kinB+), but also of the kinA kinB+ and kinA+ kinB strains. In all cases, the three ethanol-treated strains showed, on sporulation plates, the same Spo0 phenotype (data not shown) and a dramatic reduction in the capacity to form spores in liquid culture (Table 2). Furthermore, ethanol treatment also reduced the number of produced spores of a kinA kinB strain to levels of a spo0A mutant strain (less than 10 spores ml−1; strain RG 19990 [Table 2]). Since the low number of spores formed by a kinA kinB strain (average, 1 × 102 to 1 × 103 spores ml−1) derives from the activation of the minor sensor sporulation kinases of the phosphorelay (KinC, KinD, and KinE) (18), it can be concluded that ethanol treatment inhibited spore formation even when KinA and KinB were absent (Table 2, bottom row, kinA kinB strain). Moreover, since it is accepted that the activating pathways of the three membrane-bound (KinB, KinC and KinD) and the two soluble (KinA and KinE) sensor sporulation kinases must respond to different sorts of environmental and metabolic signals (18), we considered it unlikely that ethanol could block simultaneously the five independent sporulation-activating pathways. Thus, apart from discarded KinA as the alcohol target (42), we concluded that the not-yet-identified key sporulation event inhibited by ethanol should take place during a time window downstream from that of the activation of the sensor-sporulation kinases but before the induction of Spo0A∼P-dependent genes.

TABLE 2.

Ethanol does not affect the activating pathways of the sensor sporulation kinasesa

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Ethanol added | Viable cells/ml | Spores/ml | Spores (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JH642 | kinA+kinB+ | No | 4.1 × 108 | 2.9 × 108 | 70.70 |

| Yes | 3.3 × 108 | 1.3 × 104 | 0.004 | ||

| JH19087 | kinA kinB+ | No | 5.7 × 108 | 3.6 × 107 | 6.32 |

| Yes | 1.8 × 108 | 1.0 × 103 | 0.001 | ||

| JH19980 | kinA+kinB | No | 3.7 × 108 | 1.0 × 108 | 48.20 |

| Yes | 2.9 × 108 | 8.6 × 104 | 0.003 | ||

| RG19990 | kinA kinB | No | 5.0 × 108 | 1.0 × 103 | 0.0002 |

| Yes | 3.0 × 108 | <10 | <0.000003 |

Effect of ethanol on spore formation in liquid culture of B. subtilis strains harboring mutations in the coding genes for the main sporulation kinases. Cultures were grown with or without ethanol (0.7 M) in liquid SSM at 37°C.

Samples were tested for spore formation after 20 h of growth. Data are the averages of five independent experiments.

Alcohol stress blocks the phosphorelay signaling pathway and interferes with the activation of Spo0A∼P-dependent genes.

Since regulated proteolysis has been determined to be an important regulatory mechanism during development (25), we wondered whether alcohol affected the stability of Spo0A itself. To this end, we used B. subtilis strain Sik31, which was engineered to produce, under the control of the isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible Pspac promoter, a constitutive active form of Spo0A named Spo0A-Sad67 (1, 16). Spo0A-Sad67 represents a shortened form of Spo0A resulting from an internal deletion of the wild-type spo0A gene (16). Even though Spo0A-Sad67 is not exactly the same as the native form of Spo0A, it has been previously shown by different groups that it fully mimics the behavior of active Spo0A (Spo0A∼P) under different conditions (1, 16). Thus, we considered the use of strain Sik31 a valuable tool to turn on and off the expression of spo0A-sad67 (±IPTG, respectively) for the study of the stability of Spo0A-Sad67 synthesized before the addition of the alcohol. Hence, we produced (in the presence of IPTG) active Spo0A-Sad67 to monitor its stability in the absence (after IPTG removal) of de novo synthesis of Spo0A-Sad67. Under these experimental conditions, levels of Spo0A-Sad67 in protease-proficient wild-type cells were essentially the same, as judged by Western analysis and densitometry, in the presence or absence of alcohol, which made it reasonable to consider that ethanol did not affect the stability of active Spo0A (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Ethanol does not affect the stability of Spo0A-Sad67. Western blot experiment showing the in vivo stability of the Spo0A∼P equivalent form Spo0A-Sad67 in ethanol-treated and untreated cultures. A 100-ml culture of B. subtilis strain Sik31 (Δspo0A::Ermr Pspac-sad67) was grown in SSM at 37°C until mid-exponential phase. At this point IPTG (1 mM) was added, and growth was continued for another 2 h. After this induction period (production of Spo0A-Sad67), the 100-ml culture was washed three times and growth was resumed in fresh prewarmed SSM without IPTG. Five minutes later, ethanol (0.7 M) was added to one-half of the washed culture, and both halves (with and without ethanol) were further incubated at 37°C. At the indicated times, samples were removed to prepare the cell extracts. Lanes 1 and 2, levels of Spo0A-Sad67 after the 2-h incubation period with IPTG before and immediately after its removal (IPTG washing), respectively. Lanes 3 to 10, levels of Spo0A-Sad67 at the indicated times after resumption of growth in fresh IPTG-free SSM with or without ethanol supplementation. Protein extracts, electrophoresis conditions, and reaction with anti-Spo0A antibodies were as indicated in Materials and Methods.

Discarding the activating pathways of the sensor sporulation kinases (Table 2) and regulated proteolysis of active Spo0A (Fig. 2) to explain the Spo0 phenotype of alcohol-treated cells, we analyzed whether alcohol treatment inhibited the phosphorylation of Spo0A by the phosphorelay signaling system and/or the activity of Spo0A∼P as a transcription regulator. Thus, we monitored the effect of ethanol treatment on the efficiency of spore formation in cultures of strain Sik31 induced by IPTG before the addition of alcohol. In this way, we were able to separate the activity of the Spo0A-Sad67 transcription factor from the integrity of its activating pathway (the phosphorelay) since Spo0A-Sad67 does not require phosphorylation for its activity (16). Surprisingly, the addition of IPTG to Sik31 cultures only partially suppressed the inability to produce spores in the presence of alcohol. In fact, the IPTG-directed synthesis of this phosphorylation-independent form of Spo0A restored the capacity of ethanol-treated cells to make spores at intermediate levels (average of 5 × 106 spores/ml), compared to nontreated and treated cultures of the wild-type strain (averages of 1 × 108 and 5 × 104 spores/ml respectively). These results opened the possibility of the existence of multiple targets of alcohol in its effect on sporulation (see below).

A transposon-generated insertional library to isolate developmental suppressors of ethanol.

The results presented above permitted us to hypothesize that the inhibition of spore morphogenesis by alcohol arose from the induction of more than one negative regulator of sporulation acting at least at two levels: decreasing the generation of Spo0A∼P by the phosphorelay signaling pathway (possibility 1 in Fig. 3A) and interfering with the activity of Spo0A∼P as a transcription factor before asymmetric division (possibility 2 in Fig. 3A). Thus, we formulated a hypothetical scenario where B. subtilis should be able to sporulate in the presence of alcohol when carrying mutations in the genes coding for the proposed ethanol-induced negative regulators. In order to identify these presumed existent regulatory genes, we generated, with the minitransposon mini-Tn10 (40), an in vivo spectinomycin resistant (Spcr) JH642-derived insertional library. This Spcr insertional library was enriched in the presence of ethanol and screened on sporulation plates to isolate Spcr transposants able to sporulate in the presence of alcohol (data not shown). After the analysis of almost 11,000 alcohol-enriched transposants, several putative alcohol-resistant clones were isolated. Transformation to Spcr of competent cells of the wild-type ethanol-sensitive parental strain JH642 with chromosomal DNA prepared from each of the putative alcohol-resistant candidates showed that only two of them transferred with 100% efficiency the nonselected resistance of sporulation to the presence of alcohol. The DNA sequence of the chromosome regions that flanked the ends of the mini-Tn10 transposon inserted in both alcohol-resistant suppressors, after their rescue in E. coli, in comparison with the annotations for the genome sequence of B. subtilis (21) revealed that both insertions were independent. In one case, the mini-Tn10 transposed on the promoter region of the Spo0F∼P phosphatase-coding gene rapA. In the second case, the mini-Tn10 transposed on the N-terminal coding region of the developmental regulatory gene sinR (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Identification of cell fate determinants involved in alcohol-produced inhibition of cellular morphogenesis in B. subtilis. (A) Cartoon summarizing a hypothetical scenario in which alcohol treatment triggers the expression of more than one negative regulator of spore development that would interfere with the activation of Spo0A by the phosphorelay (possibility 1) and its activity as a transcription factor (possibility 2). These induced antisporulation regulatory factors should be responsible for the inhibition of the activity of the phosphorelay signaling system (phosphorylation of Spo0A) and the inhibition of the activity of Spo0A∼P itself. (B) Identification of alcohol-resistant transposants after the generation of the insertional mini-Tn10 library, enrichment, isolation, and DNA sequencing (40). The DNA sequence information permitted the determination of the precise location of the original transpositions of mini-Tn10 in clones 1 and 2 of B. subtilis that generated the alcohol-resistant phenotype observed on the sporulation plates.

rapA and sinR mutations fully suppress the inhibitory effect of alcohol on spore morphogenesis.

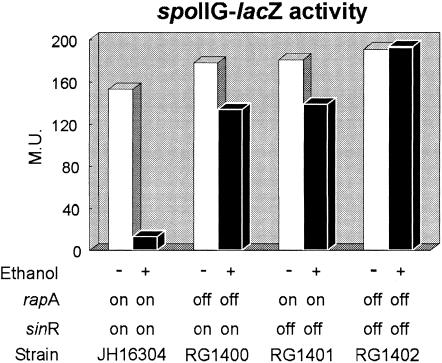

In order to determine the significance of the two isolated alcohol-resistant suppressors, we analyzed the expression of a Spo0A∼P-dependent β-galactosidase fusion and the efficiency of spore formation in different rapA and sinR genetic backgrounds. As shown in Fig. 4, while single rapA and sinR mutant strains showed significant, although partial, levels of Spo0A∼P activity in the presence of ethanol, only a double rapA sinR mutant strain had the full activity of the transcription factor restored in alcohol-treated cells. According to this result, both single mutant strains were able to form a significant number of spores in the presence of alcohol, while the double rapA sinR mutant strain was completely insensitive to ethanol inhibition of spore formation (Table 3). In addition, the double rapA sinR mutant strain retained the capacity to make spores at wild-type levels (complete Spo+ phenotype) in the presence of subinhibitory concentrations of alcohol of different C lengths (methanol, 1-propanol, and 2-propanol) that were previously reported (3, 4) to severely block sporulation of wild-type cells (data not shown). The overall results, the unaffected Spo0A∼P activity and the full capacity of the double rapA sinR mutant strain to make spores in the presence of different alcohols, strongly indicated that SinR and RapA were the main or unique regulators involved in the inhibition of spore formation under alcohol stress.

FIG. 4.

The cell fate determinants SinR and RapA are responsible for the inhibition of spore morphogenesis under alcohol stress. Levels of Spo0A∼P-dependent β-galactosidase activity from different JH16304-derived isogenic strains harboring rapA and/or sinR mutations in the presence or absence of ethanol (black and white bars, respectively). Cultures of JH16304 (wild type) and the isogenic derivatives RG1400 (ΔrapA::ery), RG1401 (ΔsinR::cat), and RG1402 (ΔrapA::ery ΔsinR::cat) were grown in SSM until the late exponential phase (T−1.5), when ethanol (0.7 M) was added to one-half of each culture. Growth of the eight cultures was continued for several hours, and samples were collected and assayed for β-galactosidase activity. The reported Miller units (M.U.) represent the sum of β-galactosidase activities determined every 30 min from T0 to T2.5 for each culture. Data are the averages from three independent experiments done in triplicate. The activity of the Spo0A reporter lacZ fusion and the efficiency of spore formation (+/− ethanol) were essentially the same for strains RG19 (rapA::mini-Tn10-Spcr)/RG1401 (ΔrapA::Eryr) and RG23 (ΔsinR::mini-Tn10-Spcr)/RG1400 (ΔsinR::Catr), respectively (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Efficiency of sporulation in ethanol-treated and untreated wild-type, sinR, and rapA strainsa

| Strain | SSM

|

SSM + ethanol (0.7 M)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viable cells/ml | Spores/ml | Spores (%)b | Viable cells/ml | Spores/ml | Spores (%)b | |

| JH642 (wild type) | 4.0 × 108 | 3.6 × 108 | 90.00 | 3.0 × 107 | 1.7 × 104 | 0.057 |

| RG23 (rapA) | 1.9 × 108 | 1.8 × 108 | 94.74 | 2.7 × 107 | 3.4 × 106 | 12.59 |

| RG19 (sinR) | 8.0 × 108 | 7.5 × 108 | 93.75 | 2.8 × 107 | 5.2 × 106 | 18.57 |

| RG433 (sinR rapA) | 8.3 × 108 | 8.1 × 108 | 97.59 | 1.3 × 107 | 1.2 × 107 | 92.31 |

Cultures were grown in SSM at 37°C for 20 h. For the treated cultures the alcohol (0.7 M) was added 2 h before the onset of stationary phase. The results of a representative experiment are shown.

Note that the ethanol-treated culture of strain RG433 (sinR rapA mutant) reached the same sporulation efficiency as those of the untreated cultures (bold numbers).

rapA expression is induced by ethanol treatment.

The response regulator Spo0F∼P of the phosphorelay signal transduction system is the specific target of RapA, which is the first and best-characterized member of the Rap family of aspartyl phosphate phosphatases (17, 22, 29). Expression of rapA is known to be differentially activated by physiological processes other than sporulation, as is the case for genetic competence, which is under the control of the ComP-ComA two-component signal transduction system (26). This regulatory circuit allows the recognition of signals antithetical to sporulation and provides a means to impact on phosphorelay and the level of generated Spo0A∼P, which is, in addition, a repressor of rapA transcription (26).

A further level of complexity is brought into the system by the mechanism modulating RapA phosphatase activity (29, 31, 32). The rapA gene is transcriptionally coupled to a second gene, phrA, which encodes an inactive 44-amino-acid phosphatase regulator protein, pro-PhrA (32). pro-PhrA is subject to a series of proteolytic events throughout an export-import control circuit, which finally result in the appearance of an intracellular active PhrA pentapeptide (29). This PhrA pentapeptide inhibits specifically the phosphatase activity of RapA on Spo0F∼P (17, 29). Thus, we analyzed the effect of ethanol on rapA expression in order to obtain more insights on how cell fate was affected by alcohol and to distinguish between a causative and a noncausative link between ethanol treatment and rapA regulation. As is shown in Fig. 5A, ethanol treatment stimulated significantly the expression of the reporter fusion to the rapA promoter. This result reinforced the view of a functional (causative) link between alcohol stress and rapA response that contributes to the generation of the Spo0 phenotype observed in the presence of alcohol. Furthermore, ethanol-enhanced rapA expression was independent of its specific repressor, Spo0A∼P, but it still required the presence of its positive regulator, the competence response regulator ComA∼P (Fig. 5B). The last result suggested that the RapA-dependent branch of the alcohol inhibitory pathway of sporulation depended on a functional competence pathway. Since pro-PhrA is encoded by the same transcript as RapA (29, 32), it could be reasonable to imagine that the expression of the pro-inhibitor could also be induced by ethanol treatment. If this was the case, the ethanol-induced pro-PhrA would inhibit (after its processing and reinternalization) the activity of overexpressed RapA. Hence, in opposition to the obtained experimental results (Fig. 4 and 5 and Table 3), the developmental RapA phosphatase would not have an important role in the inhibition of spore formation under alcohol stress. However, and in accordance with the present results, it was recently reported that overproduction, from a multicopy plasmid, of the PepF oligopeptidase inhibited sporulation initiation in B. subtilis due to hydrolysis of the PhrA pentapeptide at some stage of its maturation/activation pathway (19). It was previously shown (33) that the single PepF-coding gene (formally called yjbG) belongs to a class of stress genes strongly induced by ethanol treatment in a σB-independent manner. Taking into consideration these reports (19, 33) and the present results, we propose that the induction of the rapA-phrA operon after ethanol addition (Fig. 5A and B) was accompanied by the overexpression of the PepF-coding gene, yjbG (33). Both ethanol-directed transcriptional inductions (rapA-phrA and pepF) would produce a PepF-mediated proteolysis of pro-PhrA/PhrA (19). Hence, the overproduction of free and active RapA phosphatase (19, 33) plus the two levels of rapA induction observed after alcohol addition (Fig. 5A and B) would constitute a functional link between the regulatory network of the phosphatase and the significant inhibition of sporulation after alcohol addition (Fig. 5C).

FIG. 5.

Ethanol treatment enhances RapA production. (A) β-Galactosidase activity of strain JH12981 (rapA-lacZ) grown in SSM in the absence or presence of ethanol (0.7 M). For the treated culture (open symbols) alcohol was added at early exponential phase (optical density at 525 nm [OD525] of 0.25). Samples were removed at the indicated times and assayed for β-galactosidase activity. Data from a representative experiment are shown. (B) Levels of rapA expression in wild-type (JH12981) and two isogenic spo0A and comA mutants strains. Cultures were grown in SSM at 37°C until mid-early exponential phase (OD525, 0.35), at which time ethanol (0.7 M) was added to one-half of each culture. Growth was resumed, and samples were taken every 30 min for measurement of β-galactosidase activity. The reported Miller units (M.U.) represent the sum of β-galactosidase activities accumulated from the moment of ethanol addition until 1 h after the end of the exponential phase. Data are the averages of three independent experiments done in triplicate. (C) Model for the RapA-dependent branch of inhibition of sporulation by alcohol treatment. In untreated exponentially growing cells (minus ethanol in the cartoon), expression of the rapA-phrA operon is driven from the σA-containing form of RNA polymerase under the temporal negative and positive control of Spo0A∼P and ComA∼P, respectively. Even though the presumed levels of both regulatory cell fate determinants (RapA and pro-PhrA) should be similar, the RapA phosphatase is constitutively active. This is because pro-PhrA is exported, in a SecA-dependent process, and accumulated in the extracellular medium as an inactive precursor. At the onset of stationary phase, pro-phrA is processed to an active pentapeptide and imported to the cellular cytosol (through the Opp oligopeptide permease) to inhibit RapA activity. As a result, more phosphate is transferred through the phosphorelay to Spo0A to reach the threshold of Spo0A∼P needed for the initiation of spore formation. In exponentially growing ethanol-treated cells (plus ethanol in the cartoon), the ComA-dependent enhanced rapA-phrA expression would result in higher levels of both regulatory proteins. However, since ethanol also induces the expression of the stress gene yjbG (coding for the pro-PhrA/PhrA oligopeptidase PepF), it is hypothesized that pro-PhrA/PhrA is proteolytically degraded under ethanol treatment (19). Hence, both during exponential and stationary phases of ethanol-treated cultures, only free and active RapA phosphatase would be present, producing a profound blockage of the ability of B. subtilis cells to initiate sporulation in the presence of alcohol.

Ethanol activates sinR transcription and represses the stationary-phase induction of sinI.

One of the best-characterized B. subtilis transition state regulators is the DNA-binding protein SinR and its posttranslational antagonizing regulator, SinI (2). SinR is a key developmental repressor of the early sporulation genes spo0A, spoIIA, spoIIG, and spoIIE (23, 24). Hence, SinR antagonizes and/or interferes with the inducing activity of Spo0A∼P on those sporulation genes (23, 24). SinR activity is decreased as SinI levels increase at the beginning of stationary phase as a consequence of the formation of an inactive complex between SinI and SinR that inhibits its ability to bind to DNA (2). Both developmental regulatory proteins are encoded in the same sin operon in the order sinI-sinR and expressed from three differentially regulated promoters (14). The promoters P1 (σA dependent) and P2 (σE dependent) precede sinI and produce RNAs that span the complete operon, while the σA-dependent P3 promoter precedes the sinR gene (14; Fig. 3B). Among these promoters, P1 is the most important in regulating sinIR expression at the onset of the sporulation and in determining the ratio of SinI and SinR proteins (2). In fact, sinIR expression from P1 is downregulated during the vegetative phase by the transcription factor Hpr and dramatically induced by Spo0A∼P at the onset of stationary phase (14, 38; Fig. 3B). On the contrary, the P3-directed transcription of sinR is almost constant and relatively low throughout growth and remains largely unaffected in a spo0A mutant background (14, 38).

We then considered it of interest to determine whether the analyzed sinR mutations (Fig. 4 and Table 3) compensated for the deleterious effect of ethanol on spore morphogenesis due to a specific effect of ethanol on the production of the Sin proteins not previously observed. To do this, we analyzed the expression of each component of the sin operon, using B. subtilis strains carrying sinI-lacZ and sinR-lacZ fusions that contained the P1 and the P3 promoters, respectively (14). As is shown in Fig. 6A, ethanol treatment produced a significant induction throughout of sinR expression from the σA-dependent P3 promoter. Due to the novelty of the positive effect of alcohol on sinR expression from the P3 promoter, we are conducting experiments to uncover the nature of the alcohol-targeted regulator that, positively or negatively, would control sinR expression.

FIG. 6.

Ethanol affects the SinR-SinI-dependent regulatory circuit controlling spore development in B. subtilis. (A to C) β-Galactosidase activities of the reporter fusions sinR-lacZ (RG438) (A) and sinI-lacZ (RG437) (B and C) in wild type (A and B) and hpr mutant (RG439) (C) strains. Cells were grown in SSM at 37°C until mid-exponential phase, at which time ethanol (0.7 M) was added to one-half of each culture (arrow). Growth was continued for several hours, and β-galactosidase activity was measured at the indicated times (closed symbols, without ethanol; open symbols, with ethanol). The results of a representative experiment are shown. M.U., Miller units. (D) Model for the SinR-dependent branch of inhibition of sporulation by alcohol treatment. In untreated ethanol cultures (minus ethanol in the cartoon), SinR synthesis blocks spo0A and early spoII gene expression during exponential phase (23, 24). Hence, the start of sporulation is prevented during vegetative growth. At the onset of stationary phase down-regulation of the Hpr repressor and the higher levels of Spo0A∼P activate transcription of sin. The increased levels of SinI overcome SinR levels, sequestering all the repressor protein in an inactive complex (SinI::SinR); hence sporulation begins. With alcohol treatment (plus ethanol in the figure), sinR expression is enhanced during both exponential and stationary phases. Simultaneously, down-regulation of spo0A (due to enhanced production SinR and RapA, see above) up-regulates abrB and hpr expression (data not shown). The decreased generation of Spo0A∼P and the increased levels of Hpr, activator and repressor of sinI expression, respectively, result in the production of low levels of SinI that cannot overcome the ethanol-dependent SinR overproduction; hence the beginning of sporulation is constitutively blocked. Also shown is the repressing effect of Hpr on opp, which contributes to the RapA-mediated inhibitory effect of alcohol on sporulation (see the text for details).

On the other hand, ethanol treatment completely blocked the Spo0A∼P-dependent P1-induction of sinI expression at the onset of stationary phase (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, this inhibitory effect on sinI stationary-phase expression was completely released in the absence of its specific repressor, Hpr (hpr mutant background, Fig. 6C). This last result suggested that the negative effect of ethanol on sinI expression is indirect, probably due to the upregulation of abrB and hpr (38, 39). Effectively, since Spo0A∼P is a repressor of abrB, which in turn is an activator of hpr, our interpretation was that the low levels of Spo0A∼P formed after the addition of alcohol (primary effects of RapA and SinR) should result in derepression of abrB and hence upregulation of hpr. Overproduced Hpr will ultimately impair sinI (38) induction when the ethanol-treated culture reaches the stationary phase of growth. Taking into account these results, we concluded that in the presence of subinhibitory concentrations of ethanol the levels of the SinR developmental regulatory protein would far exceed the levels of its inhibitory partner, SinI, contributing to the inhibition of spore formation before asymmetric division (Fig. 6C). Moreover, the upregulation of hpr should also contribute to the RapA-mediated inhibitory effect of alcohol on sporulation since Hpr is a strong repressor of opp, whose product (the oligopermease Spo0K) is essential for the internalization of Phr peptides (20).

An integrated portrait of the responsive network of B. subtilis to alcohol stress.

B. subtilis cells respond almost immediately to different growth-limiting stresses (including alcohol treatment) by producing a large set of general stress proteins that permit the adaptation of nongrowing and nonsporulating cells for long-term survival (36). The genes encoding the majority of these general stress proteins belong to the σB-dependent general stress regulon, which currently comprises more than 100 genes (36). Even though, σB was induced and active under our experimental conditions (data not shown) and would be involved in the adaptation of B. subtilis cells to the growth-limiting conditions imposed by ethanol treatment (36), the transcription factor σB, and hence the genes under its control, were not involved in the detrimental effect of alcohol on sporulation (data not shown). In fact, the results of the present work showed that alcohol treatment blocked spore formation by two complementary and simultaneous mechanisms that yield B. subtilis cells arrested at the onset of the differentiating pathway (Spo0 phenotype, Fig. 1K).

The evidence presented here shows that ethanol treatment produced inhibition of sporulation during a time window downstream of that of the activating pathway of the sensor sporulation kinases (Table 2) but before asymmetric division (Fig. 1 and 2). The addition of alcohol before the commencement of stationary phase interfered with the phosphorylation of the master developmental protein Spo0A (RapA effect) and with the activity of Spo0A∼P as a transcription factor (SinR effect) (Fig. 3 and 4). The fact that a double sinR rapA mutant strain was completely refractive to the inhibitory effects of different alcohols (ranging from C1 to C4) on sporulation (Table 3 and data not shown) strongly suggested that SinR and RapA were the main or unique cell fate determinants responsible for the inhibitory effect of alcohol on sporulation. Furthermore, the expression of both developmental genes sinR and rapA was novel and was significantly stimulated by ethanol treatment while sinI was simultaneously repressed (Fig. 5A and B and Fig. 6A to C). These alcohol-directed effects on rapA, sinR, and sinI expression strongly suggest (in connection with the complete Spo+ phenotype of the rapA sinR mutant strain in the presence of different alcohols) a genuine and physiological connection between alcohol treatment, gene expression, and the inhibition of spore formation mediated by RapA and SinR (Fig. 5C and Fig. 6D). Moreover, it is worthy to mention that the present results bring about a plausible explanation for the mysterious alcohol-resistant phenotype of B. subtilis strains carrying the crsA47 mutation (27). In fact, the crsA47 mutation is located within the gene for the σA subunit of RNA polymerase (sigA or rpoD), and it was shown that the introduction of the crsA47 mutation in wild-type strains of B. subtilis almost abolished sinR expression in sporulation medium (12). Taking into consideration this observation (12) and the present work (Fig. 6A) it can be assumed that the observed and unexplained sporulation resistance of crsA47 strains to alcohol is a consequence of the absence of sinR induction in this genetic background. Other genes, hpr and pepF, would play in addition an important indirect role that assures the overproduction under ethanol stress of active SinR and RapA (Fig. 5C and Fig. 6D)

Finally, why should subinhibitory doses of alcohol block sporulation at stage zero? Experiments recently done in our laboratory indicate that subinhibitory doses of ethanol, added before the onset of sporulation, produce a strong inhibitory effect on de novo fatty acid synthesis (Fig. 7A and unpublished data). Since de novo fatty acid synthesis not only is essential for cellular morphogenesis in other bacteria and mammals (5, 10) but is also indispensable for spore formation in B. subtilis (37), we propose that the regulatory network integrated by alcohol and its primary effectors (σB, RapA, and SinR) constitutes a novel developmental checkpoint (8, 13, 28) that impairs the onset of sporulation in the absence of an active de novo fatty acid synthesis that is required at later stages of development beyond Spo0A activation (Fig. 7B).

FIG. 7.

The inhibitory effect of alcohol on sporulation constitutes a developmental checkpoint assuring cellular survival in the absence of lipid synthesis. (A) Autoradiographic pattern of lipids synthesized by the reference strain JH642 in the presence of the specific inhibitor of fatty acid synthesis cerulenin or ethanol in sporulation medium. A culture of strain JH642 was grown until T0 in SSM at 37°C. At this time several 1-ml samples were taken and treated with ethanol (0.7 M) or cerulenin (5 μg ml−1) and exposed to 10 μCi of [14C]isoleucine for 3 h at 37°C. A duplicate 1-ml sample was incubated for the same period with the radioactivity but without cerulenin or ethanol supplementation (positive control). After these incubation periods lipids were extracted and chromatographed as described in Material and Methods. The radioactive compounds were located by autoradiography, eluted from the silica gel, and then quantified by scintillation counting. The sample in lane 1 (positive control) contained 10,000 and 13,000 cpm of radioactivity in the phospholipid (PL) and diacylglycerol (DG) fractions, respectively. Lanes 2 (cerulenin treated) and 3 (ethanol treated) contained 390 and 430 cpm in the PL fractions, and 400 and 350 cpm in DG fractions, respectively. Essentially, the same results were observed in several independent experiments done with [14C]acetate or [14C]isoleucine as precursors of radioactive lipids. (B) Schematic cartoon representing the effects of and the key regulators triggered by alcohol treatment and their roles in spore formation and cellular survival.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Grossman, T. Leighton, T. Msadek, F. Kawamura, I. Kurtser, P. Piggot, C. Price, W. Schumann, I. Smith, and A. Sonenshein for their suggestions during the course of this work and for the provided strains. We especially thank Tarek Msadek for providing the pIC333 delivery vector and unpublished comments, Masaya Fujita and F. Kawamura for the anti-Spo0A antibodies, and Alan Grossman and Iren Kurtser for their valuable advice on the using the spo0A-sad67 construction under the control of the IPTG promoter.

This research was supported by local grants to R.G. from the following Argentine agencies: FONCyT (PICT-0111651), CONICET (PIP-03052), and Fundación Antorchas (1402257).

Footnotes

Dedicated to the memory of Pierre Schaeffer, who was a clever mind and a visionary at the beginning of the era of sporulation study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arabolaza, A. L., A. Nakamura, M. E. Pedrido, L. Martelotto, L. Orsaria, and R. Grau. 2003. Characterization of a novel inhibitory feedback of the anti-anti-sigma SpoIIAA on Spo0A activation during development in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 47:1251-1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bai, U., I. Mandic-Mulet, and I. Smith. 1993. SinI modulates the activity of SinR, a developmental switch protein of Bacillus subtilis, by protein-protein interaction. Genes Dev. 7:139-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bohin, J. P., and B. Lubochinsky. 1982. Alcohol-resistant sporulation mutants of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 150:944-955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bohin, J. P., D. Rigomier, and P. Schaeffer. 1976. Ethanol sensitivity of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis: a new tool for the analysis of the sporulation process. J. Bacteriol. 127:934-940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brassinga, A. K. C., B. Gorbatyuk, M. C. Ouimet, and G. T. Marczynski. 2000. Selective cell cycle transcription requires membrane synthesis in Caulobacter. EMBO J. 19:702-709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burbulys, D., K. Trach, and J. A. Hoch. 1991. The initiation of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis is controlled by a multicomponent phosphorelay. Cell 64:545-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burkholder, W. F., and A. D. Grossman. 2000. Regulation of the initiation of endospore formation in Bacillus subtilis, p. 151-166. In Y. V. Brun and L. J. Shimkets (ed.), Prokaryotic development. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 8.Burkholder, W. F., I. Kurtser, and A. D. Grossman. 2001. Replication initiation proteins regulate a developmental checkpoint in Bacillus subtilis. Cell 104:269-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cano, R. J., and M. K. Borucki. 1995. Revival and identification of bacterial spores in 25 to 40 million year-old Dominican amber. Science 268:1060-1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chirala, S. S., H. Chang, M. Matzuk, L. Abu-Elheiga, J. Mao, K. Mahon, M. Finegold, and S. J. Wakil. 2003. Fatty acid synthesis is essential in embryonic development: fatty acid synthase null mutants and most of the heterozygotes die in utero. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:6358-6363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung, J. D., G. Stephanopolus, K. Ireton, and A. D. Grossman. 1994. Gene expression in single cells of Bacillus subtilis: evidence that a threshold mechanism controls the initiation of sporulation. J. Bacteriol. 176:1977-1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dixon, L. G., S. Seredick, M. Richer, and G. Spiegelman. 2001. Developmental gene expression in Bacillus subtilis crsA47 mutants reveals glucose-activated control of the gene for the minor sigma factor σH. J. Bacteriol. 183:4814-4822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feucht, A., R. A. Daniel, and J. Errington. 1999. Characterization of a morphological checkpoint coupling cell-specific transcription to septation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 33:1015-1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaur, N. K., K. Cabane, and I. Smith. 1988. Structure and expression of the Bacillus subtilis sin operon. J. Bacteriol. 170:1046-1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grau, R. 1994. Regulation of fatty acid synthesis at low growth temperature and during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Ph.D. thesis. Universidad Nacional de Rosario, Rosario, Argentina.

- 16.Ireton, K., D. Z. Rudner, K. J. Siranosian, and A. D. Grossman. 1993. Integration of multiple developmental signals in Bacillus subtilis through the Spo0A transcription factor. Genes Dev. 7:283-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang, M., R. Grau, and M. Perego. 2000. Differential processing of propeptide inhibitors of Rap phosphatases in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 182:303-310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang, M., W. Shao, M. Perego, and J. A. Hoch. 2000. Multiple histidine kinases regulate entry into stationary phase and sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 38:535-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanamaru, K., S. Stephenson, and M. Perego. 2002. Overexpression of the PepF oligopeptidase inhibits sporulation initiation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 184:43-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koide, A., M. Perego, and J. A. Hoch. 1999. ScoC regulates peptide transport and sporulation initiation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 181:4114-4117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kunts, F., N. Ogasawara, I. Moszer, A. Albertini, G. Alloni, V. Azevedo, et al. 1997. The complete genome sequence of the Gram positive model organism Bacillus subtilis (strain 168). Nature 390:249-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lazazzera, B. A. 2000. Quorum sensing and starvation: signals for entry into stationary phase. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 3:177-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mandic-Mulet, I., N. Gaur, U. Bai, and I. Smith. 1992. Sin, a stage-specific repressor of cellular differentiation. J. Bacteriol. 174:3561-3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mandic-Mulet, I., L. Doukhan, and I. Smith. 1995. The Bacillus subtilis SinR protein is a repressor of the key sporulation gene spo0A. J. Bacteriol. 177:4619-4627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Msadek, T., V. Dartois, F. Kunst, M. L. Herbaud, F. Denizot, and G. Rapoport. 1998. ClpP of Bacillus subtilis is required for competence development, motility, degradative enzyme synthesis, growth at high temperature and sporulation. Mol. Microbiol. 27:899-914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mueller, J. P., G. Bukusoglu, and A. L. Sonenshein. 1992. Transcriptional regulation of Bacillus subtilis glucose starvation-inducible genes: control of gsiA by the ComP-ComA signal transduction system. J. Bacteriol. 174:4361-4373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ng, C., C. Buchanan, A. Leung, C. Ginther, and T. Leighton. 1991. Suppression of defective-sporulation phenotypes by mutations in transcription factor genes of Bacillus subtilis. Biochimie 73:1163-1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Partridge, S. R., and J. Errington. 1993. The importance of morphological events and intercellular interactions in the regulation of prespore-specific gene expression during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 8:945-955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perego, M. 1997. A peptide export-import control circuit modulating bacterial development regulates protein phosphatases of the phosphorelay. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:8612-8617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perego, M. 2001. A new family of aspartyl phosphate phosphatases targeting the sporulation transcription factor Spo0A of Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 42:133-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perego, M., C. Hanstein, K. M. Welsh, T. Djavakhishvili, P. Glaser, and J. A. Hoch. 1994. Multiple protein-aspartate phosphatases provide a mechanism for the integration of diverse signals in the control of development in B. subtilis. Cell 79:1047-1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perego, M., and J. A. Hoch. 1996. Cell-cell communication regulates the effects of protein aspartate phosphatases on the phosphorelay controlling development in Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:1549-1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petersohn, A., M. Brigulla, S. Haas, D. Hoheisel, U. Völker, and M. Hecker. 2001. Global analysis of the general stress response of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 183:5617-5631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Piggot, P. J., and J. G. Coote. 1976. Genetic aspects of bacterial endospore formation. Bacteriol. Rev. 40:908-962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Piggot, P. J., and R. Losick. 2002. Sporulation genes and intercompartmental regulation, p. 483-518. In A. L. Sonenshein, J. A. Hoch, and R. Losick (ed.), Bacillus subtilis and its closest relatives. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 36.Price, C. W. 2002. General stress response, p. 369-384. In A. L. Sonenshein, J. A. Hoch, and R. Losick (ed.), Bacillus subtilis and its closest relatives. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 37.Schujman, G. E., R. Grau, H. C. Gramajo, L. Ornella, and D. de Mendoza. 1998. De novo fatty acid synthesis is required for establishment of cell type-specific gene transcription during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 29:1215-1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shafikhani, S. H., I. Mandic-Mulet, M. Strauch, I. Smith, and T. Leighton 2002. Postexponential regulation of sin operon expression in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 184:564-571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith, I. 1993. Regulatory proteins that control late-growth development, 785-800. In A. L. Sonenshein, J. A. Hoch, and R. Losick (ed.), Bacillus subtilis and other gram-positive bacteria. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 40.Steinmetz, M., and R. Richter. 1994. Easy cloning of mini-Tn10 insertions from the Bacillus subtilis chromosome. J. Bacteriol. 176:1761-1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stragier, P., and R. Losick. 1996. Molecular aspects of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Annu. Rev. Genet. 30:297-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strauch, M. A., D. De Mendoza, and J. A. Hoch. 1992. cis-unsaturated fatty acids specifically inhibit a signal-transducing protein kinase required for initiation of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 6:2909-2917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang, L., R. Grau, M. Perego, and J. A. Hoch. 1997. A novel histidine kinase inhibitor regulating development in Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev. 11:2569-2579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]