Abstract

The Tat system, found in the cytoplasmic membrane of many bacteria, is a general export pathway for folded proteins. Here we describe the development of a method, based on the transport of chloramphenicol acetyltransferase, that allows positive selection of mutants defective in Tat function. We have demonstrated the utility of this method by selecting novel loss-of-function alleles of tatA from a pool of random tatA mutations. Most of the mutations that were isolated fall in the amphipathic region of TatA, emphasizing the pivotal role that this part of the protein plays in TatA function.

The Tat (twin arginine translocation) pathway is a protein export system found in the cytoplasmic membranes of most bacteria and in the thylakoid membranes of plant chloroplasts. The key feature of the Tat machinery that distinguishes it from all other protein transport systems is that it translocates prefolded proteins across energy-transducing membranes (reviewed in references 2 and 6). Proteins are targeted to the Tat machinery by N-terminal cleavable signal peptides that harbor a consensus S-R-R-X-F-L-K twin arginine motif, where the consecutive arginine residues are almost invariant and are essential for export (5, 30). Work with Escherichia coli has identified four genes, tatA, tatB, tatC, and tatE, that encode membrane-bound components of the Tat machinery (7, 26, 27, 34). TatA forms a high-molecular-weight homo-oligomeric membrane-bound complex that is thought to act as the protein-conducting channel of the Tat system (19, 22, 23, 28). TatE is a cryptic homolog of TatA that probably arose via gene duplication (19). TatB is distantly related to TatA/TatE but has a distinct role in protein transport (27). TatB forms a tight stoichiometric complex with TatC (8), which is the largest and most highly conserved of the Tat components. The TatBC unit forms a membrane-bound receptor that recognizes twin arginine signal peptides prior to translocation (1, 11).

The E. coli Tat machinery is capable of exporting a variety of heterologous substrates if they are equipped with typical E. coli Tat signal peptides (25, 26, 31, 32). However, attempts to use reporter proteins to provide a positive selection for Tat pathway inactivation have met with limited success. It has been reported that colicin V, when targeted to the Tat pathway by fusion to a twin arginine signal peptide, can be used to probe Tat functionality because colicin V is only bactericidal from the periplasmic side of the inner membrane (16). However, this methodology is of uncertain physiological relevance, because expression of the Tat signal peptide-colicin V fusion under conditions that normally prevent transport by the Tat pathway still resulted in cell killing (16, 17).

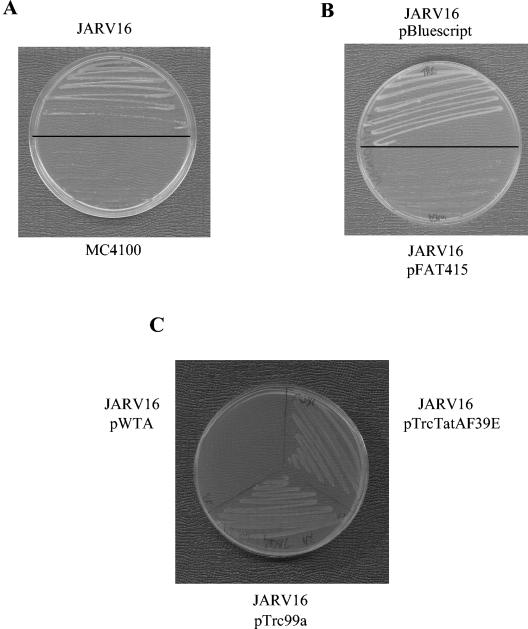

In this report, we describe the development of a facile positive selection for loss of Tat function. The screen is based on previous observations that chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT), when fused to the twin-arginine signal peptide of the FdnG protein, is exported to the periplasm by the Tat system (31). CAT inactivates the antibiotic chloramphenicol by acetylation using acetyl-coenzyme A (CoA), which is only present in the cytoplasm, as a cosubstrate. Thus, cells that export the FdnGsig-CAT fusion protein should be chloramphenicol sensitive while cells that fail to export the fusion will be chloramphenicol resistant. Previous attempts to use this strategy to select for Tat mutants failed, because the Tat system became saturated with the fusion protein, resulting in a buildup of CAT activity in the cytoplasm (31). To circumvent this problem we have constructed vector pSSCAT, based on the medium copy number plasmid pSU40 (4), which expresses the FdnGsig-CAT fusion protein under the control of the constitutive tatA promoter. The tat wild-type strain MC4100 transformed with this construct is sensitive to chloramphenicol at a concentration of 10 μg/ml on solid media. However, the cognate Tat− ΔtatA/ΔtatE strain, JARV16, harboring pSSCAT, grows quite readily in the presence of the same concentration of antibiotic (Fig. 1A). Complementation of the Tat defect of JARV16/pSSCAT with plasmid-borne tatA (pFAT415) rendered the strain sensitive to chloramphenicol, whereas transformation with an equivalent empty plasmid vector (pBluescript) does not perturb the ability of the tat mutant to grow in the presence of chloramphenicol (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Utility of the FdnGsig-CAT reporter, expressed from pSSCAT, as a positive selection for tat mutants. Plasmid pSSCAT was constructed from pUNIPROM (20) that carries the tatA promoter and ribosome binding site. The FdnG signal sequence coding region was cloned into this as a BamHI-XbaI fragment and the cat gene as an XbaI-HindIII fragment (amplified from pSU18 [4]). The entire fusion construct, including the tatA promoter region, was then cloned into pSU40 (4) using EcoRI and HindIII to generate pSSCAT. Images show growth on Luria-Bertani medium supplemented with 50 μg of kanamycin/ml and 10 μg of chloramphenicol/ml of (A) strains MC4100 (tat wild type [10]) and JARV16 (as MC4100, ΔtatA, ΔtatE [27]), each carrying pSSCAT, and (B) strain JARV16 carrying pSSCAT transformed with either pBluescript or pFAT415 (tatA insert in pBluescript) (27). Plates also contained 125 μg of ampicillin/ml to select for the presence of the pBluescript-derived plasmids. (C) Strain JARV16 carrying pSSCAT transformed with either the pTrc99A cloning vector (Amersham), pWTA (containing a wild-type copy of the tatA gene cloned into pTrc99A as an NcoI-KpnI fragment and under control of the IPTG-inducible tac promoter), or pTrcTatAF39E (based on pWTA but carrying a codon substitution of the F39 codon of tatA to glutamate). Plates also contained 125 μg of ampicillin/ml to select for the pTrc-derived plasmids, 0.1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside to induce expression of plasmid-encoded tatA, and chloramphenicol at a concentration of 15 μg/ml (the optimum concentration of chloramphenicol required to select for tat defects when tatA is expressed from pTrc99A).

To verify the functionality of our screen, we first constructed a library of tatA mutants that was randomized at the codon for Phe39. We have previously reported that substitution of Phe39 for Ala results in a TatA protein that is completely inactive for Tat transport and that, in addition, displays genetic dominance (15). The F39X library was constructed using an overlap extension protocol (14). Briefly, two DNA fragments were amplified in separate PCRs using the oligonucleotide pairs Unirep1 (5′-GCGCGAATTCCTGTCGGTTGGCGCAAAACACGCTG-3′) and F39Xup (5′-GCTCATTCGTTTTTTNNNGCCTTTGATCGACGC-3′) or F39Xdown (5′-GCGTCGATCAAAGGCNNNAAAAAAGCAATGAGC-3′) and TatArev (5′-GCGCGGTACCCTTCTACAGACATGTTTTACGGG-3′), where N indicates an equal mixture of A, G, C, or T at that position. The two PCR products were then mixed, denatured, reannealed, and used as templates for a further round of PCR using Unirep1 and TatArev as primers. The products were digested with EcoRI and BamHI and cloned into pBluescript. The tatAF39X library was transformed into the ΔtatA/ΔtatE strain, JARV16 harboring pSSCAT, and plated onto medium containing 10 μg of chloramphenicol/ml to identify substitutions that inactivated the function of TatA. Colonies were streaked onto fresh chloramphenicol-containing plates to confirm resistance and the entire tatA coding region analyzed by DNA sequencing. Forty-two percent of the clones in the library allowed growth of the tatAE mutant in the presence of chloramphenicol, indicating that they specified an inactive TatA protein. Analysis of 48 mutant alleles isolated in this screen is shown in Table 1. Eleven different amino acid substitutions, many with several alternative codons, were isolated. Assessment of the effect of these mutations on the export of native Tat substrates indicated that substitutions to His, Lys, Arg, or Ser yielded a Tat system that was completely inactive, as judged by the inability to grow in the presence of 2% SDS (which screens for export of Tat substrates AmiA and AmiC [18]) (Table 1). The remaining substitutions (Asp, Glu, Gly, Ile, Leu, Thr, or Val) had minimal activity, since they allowed some growth in the presence of SDS but possessed extremely low levels of the Tat-dependent periplasmic enzyme trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO reductase). Using standard site-directed mutagenesis methods (24), we constructed the eight remaining amino acid substitutions that we did not isolate from the chloramphenicol screen. Of these, only Trp or Tyr residues gave a significant level of Tat transport activity. Interestingly, every one of the 17 amino acid substitutions that severely affected Tat function displayed genetic dominance in that they grossly affected the level of TMAO reductase activity when coexpressed in a Tat wild-type background (data not shown). We conclude from these observations that the aromatic character of the amino acid residue at E. coli tatA codon 39 is critical for the normal function of TatA.

TABLE 1.

Analysis of substitutions isolated from the tatAF39X library by selection for chloramphenicol resistance in the presence of pSSCATa

| Codon | Substitution encoded | No. of times isolated | Growth in presence of SDS | Periplasmic TMAO reductase activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | ||||

| TTT | Wild type | + | 1.67 | |

| ΔtatA ΔtatE | − | 0.02 | ||

| Substitutions isolated by screening for chloramphenicol resistance | ||||

| GAT | D | 2 | + | 0.05 |

| GAA | E | 2 | +/− | 0.03 |

| GGA | G | 2 | + | 0.03 |

| CAT | H | 1 | − | 0.07 |

| ATC | I | 1 | + | 0.05 |

| ATA | I | 2 | NDb | ND |

| AAA | K | 2 | − | 0.04 |

| AAG | K | 2 | ND | ND |

| CTG | L | 2 | + | 0.04 |

| CTC | L | 2 | ND | ND |

| TTG | L | 5 | ND | ND |

| CGT | R | 2 | − | 0.12 |

| AGA | R | 2 | ND | ND |

| CGA | R | 1 | ND | ND |

| CGC | R | 1 | ND | ND |

| TCT | S | 3 | − | 0.07 |

| TCG | S | 1 | ND | ND |

| ACG | T | 1 | + | 0.09 |

| ACA | T | 2 | ND | ND |

| ACC | T | 1 | ND | ND |

| ATT | T | 3 | ND | ND |

| GTG | V | 1 | + | 0.04 |

| GTA | V | 3 | ND | ND |

| GTC | V | 1 | ND | ND |

| TAA | Stop | 1 | ND | ND |

| TGA | Stop | 2 | ND | ND |

| Remaining substitutions at the F39 codon | ||||

| GCT | A | − | 0.05 | |

| TCG | C | + | 0.08 | |

| ATG | M | + | 0.07 | |

| AAC | N | + | 0.06 | |

| CCG | P | + | 0.04 | |

| CAG | Q | − | 0.08 | |

| TGG | W | + | 0.88 | |

| TAT | Y | + | 1.05 |

Analysis of substitutions isolated from the tatAF39X library by selection for chloramphenicol resistance in the presence of pSSCAT. Chloramphenicol-resistant colonies were streaked onto fresh chloramphenicol-containing plates to confirm resistance and the entire tatA coding region analyzed by DNA sequencing. The activity of the Tat system supported by the mutated tatA genes was assessed by growth in the presence of 2% SDS (9) and by measuring TMAO reductase activity (expressed as micromoles of TMAO reduced per minute per milligram of protein) in the periplasmic fraction (29). The activities observed with wild-type tatA (strain JARV16 [ΔtatA/ΔtatE] harboring pFAT415) and the ΔtatA/ΔtatE mutant (JARV16 harboring pBluescript) are shown as controls. Chloramphenicol resistance of the ΔtatA/ΔtatE strain harboring pSSCAT producing the remaining TatA variants constructed by site-directed mutagenesis was not assessed.

ND, not determined.

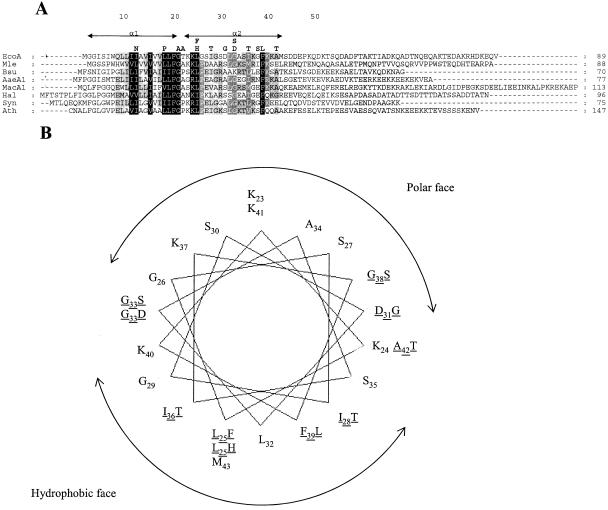

We next went on to exploit our selection strategy to probe a library of random mutations in tatA to isolate variants that are nonfunctional. The library was constructed using error-prone PCR (12) and contained over one million members, with an average error of 1 to 2 substitutions per gene. Approximately 1% of the clones in the library allowed growth of the tatA/tatE mutant in the presence of chloramphenicol. Sequence analysis of 69 clones, chosen at random, showed that 28 had substitutions that resulted in a single amino acid change in TatA, while 41 had multiple substitutions. Identification and analysis of the single amino acid substitutions in TatA is shown in Table 2, and the positions of the mutations within the TatA sequence is given in Fig. 2A. Again, some of the mutations (I28T, D31G, G33S) yielded a completely inactive Tat system, as evidenced by the inability to support growth in the presence of SDS, which is the most sensitive test for Tat activity (18, 21). The remainder gave very low, but measurable, Tat activity. All of the mutations fell within the first 42 residues of TatA, which is within the region defined as critical for activity by previous truncation analysis (21). Most of the single substitutions lie within the predicted helical amphipathic region of TatA rather than the predicted transmembrane helix. A plot of the positions of these mutations on a helical wheel, shown in Fig. 2B, shows that all except two mutations are on the hydrophobic face of the helix and that about two-thirds of the polar face does not have any mutation.

TABLE 2.

Analysis of substitutions isolated from the tatA random mutant library by selection for chloramphenicol resistance in the presence of pSSCATa

| Amino acid mutation | Sequence change(s) | No. of times isolated | Growth in presence of SDS | Periplasmic TMAO reductase activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | ||||

| Wild type | + | 0.99 | ||

| ΔtatA ΔtatE | − | 0.14 | ||

| Single amino acid substitutions | ||||

| I12N | ATT→AAT | 1 | +/− | 0.07 |

| L18P | CTG→CCG | 1 | +/− | 0.06 |

| L18P | CTG→CCG | 1 | NDb | ND |

| (G21G) | GGC→GGT | |||

| (G38G) | GGC→GGT | |||

| L18P | CTG→CCG | 1 | ND | ND |

| (S35S) | TCG→TCA | |||

| G21A | GGC→GCC | 1 | ND | 0.14 |

| T22A | ACC→GCC | 1 | + | 0.08 |

| (I15I) | ATC→ATT | 3 | + | 0.06 |

| L25F | TTC→CTC | |||

| L25H | CTC→CAC | 2 | + | 0.08 |

| (L18L) | CTG→CTA | 1 | − | 0.07 |

| I28T | ATC→ACC | |||

| (G69G) | GCG→GCA | |||

| D31G | GAT→GGT | 1 | − | 0.06 |

| (D56D) | GAT→GAC | |||

| G33D | GGT→GAT | 1 | +/− | 0.08 |

| G33S | GGT→AGT | 2 | − | 0.07 |

| I36T | ATC→ACC | 1 | + | 0.09 |

| G38S | GGC→AGC | 5 | + | 0.08 |

| (L19L) | CTC→CTT | 1 | ND | ND |

| F39L | TTT→CTT | |||

| F39L | TTT→CTT | 4 | + | 0.05 |

| A42T | GCA→ACA | 1 | + | 0.08 |

Chloramphenicol-resistant colonies were streaked onto fresh chloramphenicol-containing plates to confirm resistance, and the entire tatA coding region was analyzed by DNA sequencing. The activity of the Tat system supported by the mutated tatA genes was assessed by growth in the presence of 2% SDS (9) and by measuring TMAO reductase activity (expressed as micromoles TMAO reduced per minute per milligram of protein) in the periplasmic fraction (29). The activities observed with wild-type tatA (strain JARV16 [ΔtatA/ΔtatE] harbouring pTrc99tatA) and the ΔtatA/ΔtatE mutant (JARV16 harbouring pTrc99) are shown as controls. Additional silent mutations are in parentheses.

ND, not determined.

FIG. 2.

Position of substitutions in the E. coli TatA protein leading to loss of or reduction in Tat transport activity. (A) The positions of TatA point mutations isolated from the chloramphenicol screen are shown in boldface above an alignment of TatA protein sequences. Sequences of TatA proteins were obtained from the Swiss-Prot database and aligned against the sequence of the E. coli TatA protein using CLUSTAL W (33). The positions of the two predicted α helices are marked with double-headed arrows above the alignment. Numbering refers to amino acid positions in the E. coli protein. The abbreviations are EcoA, E. coli TatA; Mle, Mycobacterium leprae TatA; BsuAd, Bacillus subtilis TatAd; AaeA1, Aquifex aeolicus TatA1; MacA1, Methanosarcina acetivorans TatA1; Hal, Halobacterium sp. strain NRC-10 TatA; Syn, Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803 TatA; Ath, Arabidopsis thaliana Tha4 (shown with the predicted chloroplast transit peptide removed). (B) The positions of the point mutations (underlined) in the amphipathic domain of the protein are shown on a helical wheel projection of this part of the protein.

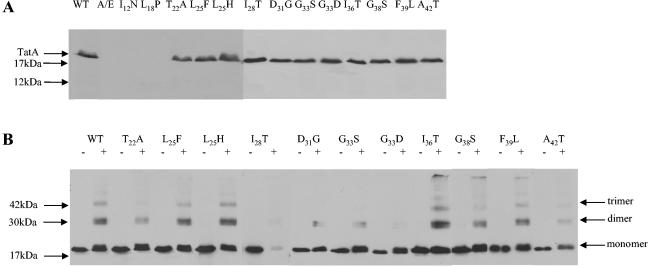

Analysis of membrane fractions of the ΔtatA/ΔtatE strain expressing the TatA variants showed that variants possessing substitutions within the amphipathic region were stably inserted in the membrane (Fig. 3A). By contrast, those variants in which the substitutions were located in the transmembrane helix could not be detected in the membrane fraction (Fig. 3A) or, indeed, elsewhere in the cell. It is, therefore, likely that these substitutions affect the membrane insertion, and hence the stability, of the protein. It should be noted, however, that these substitutions support a very low but measurable level of Tat activity (Table 2), and therefore we conclude that a very low level of these variants must be present.

FIG. 3.

Immunoblot analysis of membranes of the ΔtatA/ΔtatE strain, JARV16, expressing tatA point mutants. (A) Membrane fractions (2 μg of protein) were prepared as described previously (26) and separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) using 15% acrylamide, electroblotted, and challenged with anti-TatA antiserum (28). WT and A/E correspond to the ΔtatA/ΔtatE mutant JARV16 carrying either pWTA (wild-type tatA; WT) or pTrc99a (negative control; A/E). TatA amino acid substitutions are given above each lane. (B) Cross-linking analysis of membranes of the ΔtatA/ΔtatE strain, JARV16, expressing wild-type (annotated WT) or point-substituted tatA, as indicated above the lanes. A plus indicates that samples were incubated with the primary amine-specific cross-linker, disuccinimidyl suberate as described previously (13), whereas a minus indicates the samples were left untreated. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting as described for panel A. The positions of TatA multimers are indicated at the side.

The amphipathic region variants were subjected to treatment with the primary amine-specific, membrane-permeable, cross-linking reagent disuccinimidyl suberate (DSS) as a test of their ability to oligomerize. We have shown previously that this reagent generates cross-links between up to three adjacent TatA protomers (13). While most of the substitutions did not affect TatA protomer association, a few of the mutants gave cross-linking patterns that were significantly different from that of native TatA. Incubation of the I28T variant with DSS resulted, for unknown reasons, in loss of the protein. Variants T22A, D31G, and A42T showed a reduction in the level of cross-linking, and both substitutions at glycine 33, G33S and G33D, had a severe effect on the ability of TatA to self interact, with the G33D variant showing a complete loss of cross-linking. These observations are consistent with the substitutions giving a significant perturbation of the local protein-protein interactions. In particular, it is likely that Gly33 represents a helix-packing interaction, which is perturbed by the bulkier Ser, and that substitution of Asp results in active electrostatic repulsion of the helices. Alternatively, G33D may be undergoing electrostatic repulsion by the phospholipid head groups.

In conclusion, we have reported a generally applicable positive selection screen for the isolation of E. coli tat mutants and demonstrated its utility by screening libraries of tatA for loss-of-function alleles. Our results complement previous site-directed mutagenesis and truncation studies of TatA (3, 15, 21) and, in addition, highlight novel mutations that inactivate Tat function.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the BBSRC via grant 43/P16795 and a grant-in-aid to the John Innes Centre. M.H. and P.L. were the recipients of BBSRC studentships. Work in the Georgiou laboratory was supported by NIH grant GM069872 and by the Foundation for Research. T.P. is supported by the MRC via award of a Senior Non Clinical Fellowship.

We thank Frank Sargent for helpful discussion.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alami, M., I. Luke, S. Deitermann, G. Eisner, H. G. Koch, J. Brunner, J., and M. Muller. 2003. Differential interactions between a twin-arginine signal peptide and its translocase in Escherichia coli. Mol. Cell 12:937-946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alder, N. N., and S. M. Theg. 2003. Energy use by biological protein transport pathways. Trends Biochem. Sci. 28:442-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrett, C. M. L., J. E. Mathers, and C. Robinson. 2003. Identification of key regions within the Escherichia coli TatAB subunits. FEBS Lett. 537:42-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartolomé, B., Y. Jubete, E. Martínez, and F. de la Cruz. 1991. Construction and properties of a family of pACYC184-derived cloning vectors compatible with pBR322 and its derivatives. Gene 102:75-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berks, B. C. 1996. A common export pathway for proteins binding complex redox cofactors? Mol. Microbiol. 22:393-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berks, B. C., T. Palmer, and F. Sargent. 2003. The Tat protein translocation pathway and its role in microbial physiology. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 47:187-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bogsch, E., F. Sargent, N. R. Stanley, B. C. Berks, C. Robinson, and T. Palmer. 1998. An essential component of a novel bacterial protein export system with homologues in plastids and mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 273:18003-18006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bolhuis, A., J. E. Mathers, J. D. Thomas, C. M. Barrett, and C. Robinson. 2001. TatB and TatC form a functional and structural unit of the twin-arginine translocase from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 276:20213-20219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buchanan, G., E. de Leeuw, N. R. Stanley, M. Wexler, B. C. Berks, F. Sargent, and T. Palmer. 2002. Functional complexity of the twin-arginine translocase TatC component revealed by site-directed mutagenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 43:1457-1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casadaban, M. J., and S. N. Cohen. 1979. Lactose genes fused to exogenous promoters in one step using a Mu-lac bacteriophage: in vivo probe for transcriptional control sequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:4530-4533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cline, K., and H. Mori. 2001. Thylakoid ΔpH-dependent precursor proteins bind to a cpTatC-Hcf106 complex before Tha4-dependent transport. J. Cell Biol. 154:719-729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daugherty, P. S., G. Chen, B. L. Iverson, and G. Georgiou. 2000. Quantitative analysis of the effect of the mutation frequency on the affinity maturation of single chain Fv antibodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:2029-2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Leeuw, E., I. Porcelli, F. Sargent, T. Palmer, and B. C. Berks. 2001. Membrane interactions and self-association of the TatA and TatB components of the twin-arginine translocation pathway. FEBS Lett. 506:143-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Lisa, M. P., P. Samuelson, T. Palmer, and G. Georgiou. 2002. Genetic analysis of the twin arginine translocator secretion pathway in bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 277:29825-29831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hicks, M. G., E. de Leeuw, I. Porcelli, G. Buchanan, B. C. Berks, and T. Palmer. 2003. The Escherichia coli twin-arginine translocase: conserved residues of TatA and TatB family components involved in protein transport. FEBS Lett. 539:61-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ize, B., F. Gérard, M. Zhang, A. Chanal, R. Volhoux, T. Palmer, A. Filloux, and L.-F. Wu. 2002. In vivo dissection of the Tat translocation pathway in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 317:327-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ize, B., F. Gérard, and L.-F. Wu. 2002. In vivo assessment of the Tat signal peptide specificity in Escherichia coli. Arch. Microbiol. 178:548-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ize, B., N. R. Stanley, G. Buchanan, and T. Palmer. 2003. Role of the Escherichia coli Tat pathway in outer membrane integrity. Mol. Microbiol. 48:1183-1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jack, R. L., F. Sargent, B. C. Berks, G. Sawers, and T. Palmer. 2001. Constitutive expression of Escherichia coli tat genes indicates an important role for the twin-arginine translocase during aerobic and anaerobic growth. J. Bacteriol. 183:1801-1804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jack, R. L., G. Buchanan, A. Dubini, K. Hatzixanthis, T. Palmer, and F. Sargent. 2004. Coordinating assembly and export of complex bacterial proteins. EMBO J. 23:3962-3972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee, P. A., G. Buchanan, N. R. Stanley, B. C. Berks, and T. Palmer. 2002. Truncation analysis of TatA and TatB defines the minimal functional units required for protein translocation. J. Bacteriol. 184:5871-5879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mori, J., and K. Cline. 2002. A twin arginine signal peptide and the pH gradient trigger reversible assembly of the thylakoid ΔpH/Tat translocase. J. Cell Biol. 157:205-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Porcelli, I., E. de Leeuw, R. Wallis, E. van den Brink-van der Laan, B. de Kruijff, B. A. Wallace, T. Palmer, and B. C. Berks. 2002. Characterisation and membrane assembly of the TatA component of the Escherichia coli twin-arginine protein transport system. Biochemistry 41:13690-13697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Russell, D. W., and J. Sambrook (ed.). 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 25.Santini, C.-L., A. Bernadac, M. Zhang, A. Chanal, B. Ize, C. Blanco, and L.-F. Wu. 2001. Translocation of jellyfish green fluorescent protein via the TAT system of Escherichia coli and change of its periplasmic localization in response to osmotic up-shock. J. Biol. Chem. 276:8159-8164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sargent, F., E. Bogsch, N. R. Stanley, M. Wexler, C. Robinson, B. C. Berks, and T. Palmer. 1998. Overlapping functions of components of a bacterial Sec-independent protein export pathway. EMBO J. 17:3640-3650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sargent, F., N. R. Stanley, B. C. Berks, and T. Palmer. 1999. Sec-independent protein translocation in Escherichia coli: a distinct and pivotal role for the TatB protein. J. Biol. Chem. 274:36073-36083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sargent, F., U. Gohlke, E. de Leeuw, N. R. Stanley, T. Palmer, H. R. Saibil, and B. C. Berks. 2001. Purified components of the Escherichia coli Tat protein transport system form a double-layered ring structure. Eur. J. Biochem. 268:3361-3367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silvestro, A., J. Pommier, and G. Giordano. 1988. The inducible trimethylamine-N-oxide reductase of Escherichia coli K12: biochemical and immunological studies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 954:1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stanley, N. R., T. Palmer, and B. C. Berks. 2000. The twin arginine consensus motif of Tat signal peptides is involved in Sec-independent protein targeting in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 257:11591-11596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stanley, N. R., F. Sargent, G. Buchanan, J. Shi, V. Stewart, T. Palmer, and B. C. Berks. 2002. Behaviour of topological marker proteins targeted to the Tat protein transport pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 43:1005-1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas, J. D., R. A. Daniel, J. Errington, and C. Robinson. 2001. Export of active green fluorescent protein to the periplasm by the twin-arginine translocase (Tat) pathway in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 39:47-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, positions-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weiner, J. H., P. T. Bilous, G. M. Shaw, S. P. Lubitz, L. Frost, G. H. Thomas, J. A. Cole, and R. J. Turner. 1998. A novel and ubiquitous system for membrane targeting and secretion of cofactor-containing proteins. Cell 93:93-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]