Abstract

Type III secretion systems (TTSS) are sophisticated macromolecular structures that play an imperative role in bacterial infections and human disease. The TTSS needle complex is conserved among bacterial pathogens and shows broad similarity to the flagellar basal body. However, the TTSS of enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli, two important human enteric pathogens, is unique in that it has a ∼12-nm-diameter filamentous extension to the needle that is composed of the secreted translocator protein EspA. EspA filaments and flagellar structures have very similar helical symmetry parameters. In this study we investigated EspA filament assembly and the delivery of effector proteins across the bacterial cell wall. We show that EspA filaments are elongated by addition of EspA subunits to the tip of the growing filament. Moreover, EspA filament length is modulated by the availability of intracellular EspA subunits. Finally, we provide direct evidence that EspA filaments are hollow conduits through which effector proteins are delivered to the extremity of the bacterial cell (and subsequently into the host cell).

Type III secretion systems (TTSS) are used by large numbers of gram-negative pathogens to inject effector proteins into the host cell, effectors that interfere with normal cellular function and programs (6, 23). Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) and enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC), which are important causes of intestinal diarrhea in developing and developed countries, respectively (49), use TTSS to colonize mucosal surfaces via formation of distinct attaching-and-effacing (A/E) lesions, which are characterized by localized destruction of brush border microvilli and intimate attachment of the extracellular bacteria to the host cell plasma membrane (20, 34). EPEC and EHEC also induce profound reorganization of the actin and intermediate filaments (3, 33), which leads to formation of pedestal-like structures underneath the attached bacteria (reviewed in reference 20). The capacity to form A/E lesions is encoded mainly on the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) (16, 45), which encodes the bacterial outer membrane adhesion molecule intimin (19, 27) as well as structural, translocator (EspA, EspB, EspD) (26, 35, 36), and effector (15, 30, 31, 46, 52) proteins. Several type III effectors are encoded on loci other than the LEE (4, 13, 22, 43, 44, 48).

The TTSS is a multiprotein organelle (reviewed in reference 1). Many of its components are broadly conserved with the flagella (1, 6). Both structures consist of protein rings spanning the inner and outer membranes with a needle-like extension or a flagellar hook. The secretion organelle that can be visualized by electron microscopy (EM) is referred to as the needle complex (NC), or the basal body. The TTSS of EPEC and EHEC are unique in that they have a filamentous extension to the NC (11, 35, 53). The translocator protein EspA is the main or only constituent of these hollow filamentous conduits (10). Indeed, we have shown that EspA binds directly to the needle protein EscF (53). We have also shown that, in a manner similar to the assembly of flagella by polymerization of monomeric flagellin (47, 55), polymerization of EspA filaments is dependent on coiled-coil interactions between EspA subunits (12). It is hypothesized that the tips of EspA filaments are composed of EspD, a translocator protein that is required for filament biogenesis (35) and is the main component of the translocation pore in the host cell membrane (9). Mature EspA filaments mediate both cell attachment (5, 14, 35) and translocation of effector proteins (35) from the bacterial cytoplasm directly to the host cell cytoplasm, crossing three membranes in a single step.

One of the most important EPEC and EHEC effector proteins is Tir (30), a bacterial protein that, following translocation, is integrated into the membrane of the host cell, where it serves as a receptor for intimin. Intimin-Tir interaction leads to reorganization of the host cell cytoskeleton and intimate attachment (30); the distance between the bacterial outer membrane and the plasma membrane of the host cell is reduced to ca. 10 nm (reviewed in reference 21). A prerequisite for intimate attachment is elimination of EspA filaments and the NC. Indeed, we have shown that expression of the espA gene (8) and the presence of EspA filaments (35) are gradually down-regulated during a 6-h infection of cells in vitro.

Despite its pivotal role in EPEC and EHEC infections, the mechanism and polarity of EspA filament assembly are unknown. Moreover, although it is widely believed that, as with flagella (17) or the poly-needle (Hrp pilus) of the plant pathogen Pseudomonas syringae (40), EspA filament assembly occurs by addition of EspA subunits at the tip of the growing filament, and that effector secretion occurs through the central channel of the EspA filament, there is no direct evidence in support of this hypothesis. The aims of this project were to determine if EspA subunits are added to the base or the tip of the growing filament and to provide experimental support for the belief that EspA is a hollow conduit through which effector proteins are delivered to the extremities of the bacterial cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Bacteria were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium or in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and kanamycin (50 μg/ml) as required.

TABLE 1.

Strains, plasmids, and primers used in this study

| Strain, plasmid, or primer | Description or nucleotide sequencea | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E2348/69 | Wild-type EPEC O127:H6 | 39 |

| EDL933 | Wild-type EHEC O157:H7 Stx− | American Type Culture Collection |

| UMD872 | ΔespA::aphA-3 in E2348/69 | 32 |

| UMD870 | ΔespD::aphA-3 in E2348/69 | 38 |

| EPEC Δtir | EPEC Δtir | 30 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBAD/Myc-His C | Cloning vector | Invitrogen |

| pMSD2 | pACYC184 expressing EspAEPEC | 35 |

| pSA10 | pKK177-3 containing lacI gene | 51 |

| pICC284 | Derivative of pBAD/Myc-His C, expressing EspAEHEC | This study |

| pICC285 | Derivative of pSA10, expressing EspAEPEC | This study |

| pICC286 | Derivative of pSA10, expressing EspDEPEC | This study |

| Primers | ||

| Ncol-espAEHEC-Forw | 5′-CAT GCC ATG GAT ACA TCA AAT GCA ACA TC-3′ | |

| BglII-espAEHEC-Rev | 5′-GAA GAT CTT TAT TTA CCA AGG GAT ATT GCT G-3′ | |

| EcoRI-espAEPEC-Forw | 5′-CGG AAT TCA TGG ATA CAT CAA CTA CAG C-3′ | |

| PstI-espAEPEC-Rev | 5′-AAA CTG CAG TTA TTT ACC AAG GGA TAT TCC-3′ | |

| EcoRI-espDEPEC-Forw | 5′-CGG AAT TCA TGC TTA ATG TAA ATA ACG ATA TC-3′ | |

| SmaI-espDEPEC-Rev | 5′-TCC CCC GGG TTA AAC TCG ACC GCT GAC AAT AC-3′ |

Restriction sites are boldfaced.

Plasmids.

The espAEPEC, espAEHEC, and espDEPEC genes were PCR amplified from EDL933 or E2348/69 genomic DNA by using primers NcoI-espAEHEC-Forw and BglII-espAEHEC-Rev, EcoRI-espAEPEC-Forw and PstI-espAEPEC-Rev, and EcoRI-espDEPEC-Forw and SmaI-espDEPEC-Rev, respectively (Table 1). The PCR products were digested with the appropriate enzymes before ligation into pBAD/Myc-His C or pSA10, generating the pICC plasmids described in Table 1.

Preparation of protein samples.

Bacterial cells were grown in DMEM at 37°C for 7 h with or without 1 mM arabinose. Culture supernatants were concentrated 70-fold, and samples were analyzed by Western blotting using a polyclonal rabbit antibody against EspAEHEC as described elsewhere (35).

Bacterial infection of HEp-2 cells and immunofluorescence analysis.

Subconfluent monolayers of HEp-2 cells on glass coverslips were incubated in DMEM for 3 h at 37°C with a 1:100 dilution of an overnight LB culture. HEp-2 cells were infected as follows: bacterial strains were incubated for 2 h, after which the culture supernatants were replaced with fresh DMEM containing 0.02% arabinose, and incubation continued for a further 2 h. Nonadherent bacteria were removed, and the cells were fixed in 4% formalin for 20 min and were stained for actin and EspA filaments as described elsewhere (35, 50).

Chimeric EspA filaments were dually stained with a polyclonal mouse antibody against EspAEPEC O127:H6 and a polyclonal rabbit antibody against EspAEHEC O157:H7 diluted 1:100 for 45 min. Following three washes, coverslips were colabeled for 45 min with 1:100 goat anti-rabbit (GAR) Alexa 488 and goat anti-mouse (GAM) Alexa 594 fluorescent conjugates, and with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), to visualize bacterial bodies. Coverslips were mounted and examined on a Leica DMRE microscope equipped with a digital camera system. Single and merged images were acquired by using Leica IM image overlaying software.

Gold labeling and negative staining of EspA filaments.

LB cultures of E2348/69(pICC284) were diluted 1:100 in DMEM and grown in situ on Formvar-carbon-coated EM grids for 2 h at 37°C by using a method adapted from reference 29. Culture supernatants were replaced with fresh DMEM containing 0.02% arabinose, incubated for a further 2 h, and fixed face down on drops of 0.1% glutaraldehyde in phosphate buffer (pH 7.3). Grids were washed by transfer across 6 drops of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) blocking buffer (PBS containing 0.2% bovine serum albumin [BSA]) and dually stained on drops of 1:100 polyclonal mouse EspAEPEC O127:H6 and polyclonal rabbit EspAEHEC O157:H7 antibodies for 45 min. Grids were washed and incubated for 45 min with 1:100 GAM (gold particle diameter, 5 nm)and GAR (particle diameter, 10 nm) colloidal gold conjugates (British BioCell International). After further washing, grids were negatively stained with 2% uranyl acetate for 2 min and were dried with filter paper.

EspA filament length control.

We acquired images of EPEC bound to HeLa cells, which were infected with E2348/69, UMD872(pICC285), UMD870(pICC286), or E2348/69(pICC286/pMSD2) in the presence or absence of IPTG for 3 h. One hundred EspA filaments at ×160 magnification, stained with anti-EspAEPEC and GAR Alexa 488 conjugate, were counted. EspA filaments were projected onto a screen at 125% in IM1000 archiving software and were measured in millimeters. Statistical analyses were performed in Graph Pad Prism for 100 EspA filament measurements of the tested strain, UMD872(pICC285) or E2348/69(pICC286/pMSD2), against 100 measurements of wild-type EPEC filaments. Column statistics (i.e., mean, median, and standard deviation) and nonparametric Mann-Whitney U tests were used for significant differences.

Labeling of Tir secreted from the EspA filament.

For immunogold labeling of bacteria secreting Tir, bacteria grown overnight in LB at 37°C were diluted 1:100 in fresh DMEM-F12. Bacterial suspensions (10 μl) were applied to Formvar-carbon-coated nickel grids and incubated for 3 h at 37°C under a CO2 atmosphere. The grids were then fixed, washed, blocked with phosphate buffer containing 1% BSA (PBS-BSA), and placed on drops of mouse anti-EspA and rabbit anti-Tir antisera for 1 h at room temperature. After a wash with PBS-BSA, grids were placed on drops of 5-nm-gold-labeled GAM and 10-nm-gold-labeled GAR sera for another hour at room temperature. Grids were then washed with PBS-BSA and water, negatively stained with 2% uranyl acetate, and examined in a JEOL 1200EX transmission electron microscope operated at 80 kV.

RESULTS

Experimental design.

EspA antisera, raised against a recombinant EspA polypeptide from EHEC (EspAEHEC) or EPEC (EspAEPEC), react specifically with their respective EspA filaments, with no evidence of immunological cross-reactivity (50). In designing the experiment, we hypothesized that EspAEHEC and EspAEPEC can copolymerize into a mature filament when expressed in a single bacterium and that visualization of individual EspA subunits within a chimeric filament would allow us to determine the polymerization polarity.

EspAEHEC is biologically active in EPEC.

In order to determine if EspAEHEC is secreted and is biologically active when expressed in an EPEC background, we transformed pICC284 (pBAD-espAEHEC) into a ΔespA EPEC mutant, strain UMD872 (32), and subjected that strain to a number of functional bioassays.

We investigated whether espAEHEC is inducible and secreted when expressed in UMD872. UMD872(pICC284) was grown in DMEM in the presence or absence of arabinose. Western blotting using EspAEHEC antiserum revealed that the expression of EspAEHEC was tightly regulated by arabinose (Fig. 1A); only in the presence of arabinose was the protein detected in a concentrated culture supernatant of UMD872(pICC284) (Fig. 1A), suggesting that EspAEHEC is recognized by the EspA chaperone (CesAB) of EPEC (7) and by the EPEC secretion apparatus.

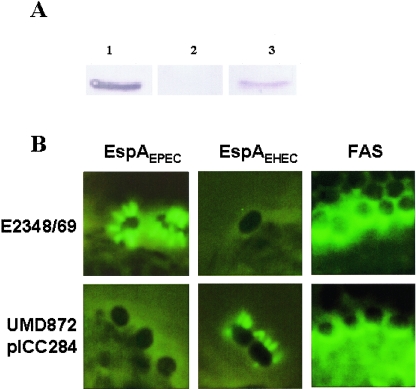

FIG. 1.

(A) Detection of EspAEPEC and EspAEHEC in concentrated culture supernatants by Western blotting. Lane 1 contains a wild-type EPEC supernatant probed with EspAEPEC antiserum as a positive control. Lanes 2 and 3 contain noninduced (without arabinose) and induced (with arabinose) UMD872(pICC284) culture supernatants, respectively, probed with EspAEHEC antiserum. (B) EspA and FAS staining. HEp-2 cells were infected with either E2348/69 EPEC or UMD872(pICC284). Filaments were detected on the surfaces of UMD872(pICC284) cells only by using EspAEHEC antiserum, whereas EspAEPEC filaments could be labeled only by using the corresponding EspAEPEC antiserum. Both strains produce a positive FAS assay.

In order to determine whether EspAEHEC filaments are formed and are biologically active in EPEC, Hep-2 cells were infected with either UMD872(pICC284) or E2348/69 EPEC (wild-type EPEC expressing EspAEPEC), stained for EspA filaments by using EspAEHEC and EspAEPEC antisera, and subjected to the fluorescent actin staining (FAS) test, a marker for effector protein translocation and actin polymerization (33). EspAEHEC filaments were visualized by immunofluorescence using the EspAEHEC antiserum, whereas, as previously reported (50), the EspAEPEC antiserum could not stain the filament (Fig. 1B). Moreover, expression of EspAEHEC in UMD872 restored the ability of the strain to induce actin polymerization in the infected epithelial cells (Fig. 1B). These results show that EspAEHEC can form the filamentous TTSS by using the EPEC NC platform and can mediate protein translocation.

EspA filaments elongate from the tips.

Once we confirmed that pICC284 encodes an inducible EspAEHEC, which is biologically active in EPEC, we investigated whether EspAEHEC and EspAEPEC can coassemble in a single bacterium and whether newly made EspA subunits are added to the distal or the proximal end of the growing filament. To this end, wild-type EPEC (strain E2348/69) was transformed with pICC284, and the strain was grown in DMEM for 2 h at 37°C, conditions that are known to induce LEE gene expression. In the absence of arabinose, EspAEHEC was not produced and EspAEPEC was the sole subunit available for polymerization of EspA filaments. Indeed, after 2 h, EspA filaments made purely from EspAEPEC were seen elaborated from the bacterial cell surface (data not shown). After the initial incubation, 1 mM arabinose was added to the culture medium in order to induce expression of EspAEHEC. The formed EspA filaments were visualized by using both EspAEPEC (red fluorescence) and EspAEHEC (green fluorescence) antisera. Examination by fluorescent microscopy revealed two types of EspA filaments (Fig. 2). The majority of the filaments were made purely of EspAEPEC (red) molecules (Fig. 2A). However a number of filaments consisted of both EspAEHEC and EspAEPEC, and in all such chimeric filaments, a portion of pure EspAEPEC filament was seen at the proximal end, closer to the bacterial cell wall, while the EspAEHEC (green) antiserum stained the distal parts of the filaments. In addition, distal parts of the filaments were themselves of two types: either composed solely of EspAEHEC subunits (stained green in Fig. 2B) or made of a combination of EspAEHEC and EspAEPEC molecules, observable in the merged image as a yellow stain (Fig. 2A). These results show that EspAEPEC and EspAEHEC can copolymerize and form biologically active filaments, but more importantly, they indicate that new EspA subunits are added to the tip of the growing filament.

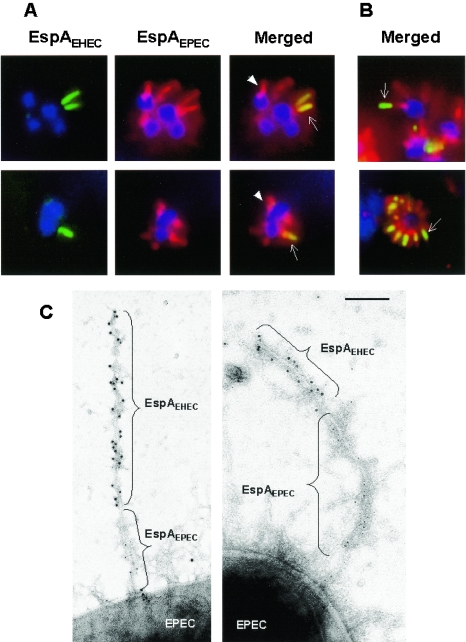

FIG.2.

Immunofluorescence staining of EspA filaments. HEp-2 cells were infected with E2348/69(pICC284) for 2 h prior to induction of espAEHEC by addition of arabinose. EspA filaments were stained for EspAEHEC and EspAEPEC subunits by using EspAEHEC (green) and EspAEPEC (red) antisera, respectively. EspAEHEC and EspAEPEC subunits were covisualized in the merged images. (A) Pure EspAEPEC filaments (arrowhead) and chimeric EspAEPEC/EspAEHEC filaments where EspAEPEC and EspAEHEC subunits were uniformly distributed along the distal part of the filament (arrows) were seen on some bacteria. (B) On other bacteria, chimeric EspAEPEC/EspAEHEC filaments consisted of proximal EspAEPEC subunits with EspAEHEC subunits only at the distal end of the filament (arrows), indicating filament growth from the tip. (C) Immunogold labeling of chimeric EspAEHEC (10-nm-diameter gold particles)/EspAEPEC (5-nm-diameter gold particles) filaments. E2348/69(pICC284) was grown on EM grids in DMEM for 2 h at 37°C to induce EspAEPEC expression, followed by 2 h with 1 mM arabinose to induce expression of EspAEHEC. Immunogold labeling with polyclonal EspAEPEC and EspAEHEC antibodies revealed EspAEPEC (5-nm-diameter gold particles) emerging from the bacterial cell membrane while EspAEHEC (10-nm-diameter gold particles) was seen at the distal end of the filament, extending the previously formed EspAEPEC filament. Bar, 0.1 μm.

In order to confirm this conclusion using an alternative method, E2348/69(pICC284) was grown on EM grids in DMEM for 2 h at 37°C before 1 mM arabinose was added to induce expression of EspAEHEC. Immunogold labeling with polyclonal EspAEPEC and EspAEHEC antibodies revealed that in all cases, EspAEPEC (5-nm gold) was detected on the portion of the EspA filaments emerging from the bacterial cell membrane while EspAEHEC (10-nm gold) was seen elongating from the preformed EspAEPEC filaments (Fig. 2C). Taken together, these results demonstrated that the newly synthesized EspA subunits are added to the distal part of the growing filament.

Overexpression of EspA leads to formation of elongated filaments.

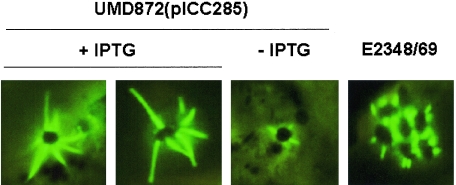

A key question concerning the biogenesis of the filament is what mechanisms control its length. It was postulated before that EspD might be involved, because an espD mutant presented atrophied filaments (35). Here we overexpressed EspD and EspAEPEC from a pSA10-based expression vector in UMD870 (ΔespD) (data not shown) and UMD872 (ΔespA), respectively, and visualized EspA filaments by immunofluorescence (Fig. 3). The tac promoter of the pSA10-based vector is not tightly regulated and allows small amounts of proteins to be expressed in the absence of IPTG. As a consequence, both strains produced EspA filaments comparable to those of the wild-type strain in the absence of IPTG (Fig. 3). Addition of IPTG led to increased protein expression and to the formation by UMD872(pICC285) of EspA filaments which are typically two- to threefold longer than those formed by the wild-type strain E2348/69 (Fig. 3; Table 2). Similarly, overexpression of both EspA and EspD in wild-type EPEC and in the presence of IPTG produced long filaments (data not shown). In contrast, overexpression of EspD in UMD870(pICC286) did not affect EspA filament length (data not shown). These results suggest that it is the availability of EspA subunits that limits the length of the filaments.

FIG. 3.

Overexpression of EspA. HEp-2 cells were infected with E2348/69 or UMD872(pICC285) in the presence or absence of IPTG, and EspA filaments were visualized by immunofluorescence staining. In the absence of IPTG, EspA filaments comparable to those of the wild-type strain were produced, whereas addition of IPTG led to formation of much longer EspA filaments (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Statistical measurements of the length of EspA filaments

| Measurementa | Value for strain:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| E2348/69 | UMD872(pICC285) | |

| No. of measurements | 100 | 100 |

| Filament length (mm) | ||

| Minimum | 3.000 | 10.00 |

| Median | 6.000 | 17.00 |

| Maximum | 12.00 | 22.00 |

| Mean | 6.340 | 17.09 |

| SD | 1.719 | 2.836 |

| Lower 95% CI | 5.999 | 16.53 |

| Upper 95% CI | 6.681 | 17.65 |

CI, confidence interval. The P value for differences between the strains was <0.0001 by the Mann-Whitney U test.

Tir is secreted from the tips of EspA filaments.

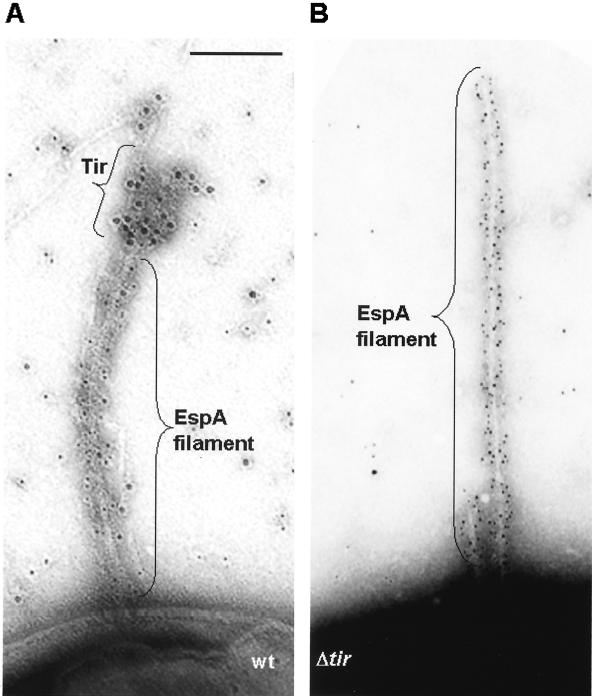

It is hypothesized that effector proteins are delivered to the host cell via hollow EspA filaments (10, 20), although there is no experimental evidence supporting this assumption. Nevertheless, the evidence described above showing that EspA subunits are delivered to the tip of the filament, where they polymerize, supports this hypothesis. In order to obtain further support for protein translocation through the filament, we examined the secretion of the EPEC effector protein, Tir. Wild-type EPEC and Δtir strains were grown on EM grids in DMEM for 3 h and immunogold labeled with polyclonal EspAEPEC and Tir antibodies. Tir staining (10-nm gold) was concentrated solely around the tips of EspA filaments (5-nm gold) of wild-type bacteria, resembling smoke discharge through a chimney; only very low background levels of staining were observed in association with EspA filaments of the Δtir strain (Fig. 4). These results strongly suggest that effector proteins are delivered along the central channel of EspA filaments and are released at the tip, as has been previously demonstrated for protein delivery through the Hrp pilus (28).

FIG. 4.

Effector protein secretion through EspA filaments. Wild-type EPEC and Δtir strains were grown on EM grids in DMEM for 3 h and stained for EspA (5-nm-diameter gold particles) and Tir (10-nm-diameter gold particles). (A) Tir staining was observed with the wild-type (wt) strain, and in each case the 10-nm gold labeling was concentrated around the tip of an EspA filament. (B) EspA filaments were produced by the Δtir mutant, but only very low levels of nonspecific background 10-nm gold were observed with this strain. Bar, 0.1 μm.

DISCUSSION

Numerous filamentous structures are present on the surfaces of gram-negative bacteria. Some are responsible for bacterial motility, whereas others are involved into host tissue adhesion, injection of virulence factors into the host cell, or transfer of genetic information by conjugation (18). Among the motility structures, the bacterial flagellum has received the most attention and its assembly has been thoroughly studied (47). It appears to be one of the most complex proteinaceous structures known in bacteria. The assembly of the flagellar structure is sequential and involves a flagellum-specific type III pathway. Type III export pathways have been described by Macnab (41) as presenting three main characteristics: (i) they use a defined platform, the hook-basal body complex or the NC; (ii) the newly synthesized structure possesses a continuous central channel; (iii) subunits are added at the distal end of the growing structure, unlike the basal growth of type I and type IV pili (24).

The EspA filament is a unique variant of a TTSS. It consists of a filamentous extension to the NC, which has both cell adhesion (5, 14, 35) and protein translocation (35) activities. We have recently determined the three-dimensional structure of the filament, which consists of a helical tube with an outer diameter of ca. 120 Å and a continuous hollow, central channel with a diameter of ca. 2.5 nm (10). Comparisons have been drawn between EspA and the flagellar filament. Although they differ in size, the helical symmetry as well as the structure and packing of the EspA subunits into the filament are similar to those of the flagellum (10).

Recent atomic-level-resolution structural studies of the flagellum revealed that the two flagellin coiled-coil domains are engaged in an intrasubunit interaction (54). Complex interactions on the flagellin surface mediate subunit polymerization to form the flagellum (25, 37). We have shown previously that, despite the fact that there is only one coiled-coil domain at the carboxy terminus of the polypeptide, this domain is essential for EspA polymerization and EspA filament formation (12). Polymerization of flagellin is dependent on a nucleating cap protein, FliD (HAP2) (42); EspA filaments require EspD (a major translocator protein) for polymerization and filament formation (35). EspD also seems to have a capping activity (12). Significantly, it has been shown that flagella can also be used to translocate virulence determinants into the host cell (56). Although the flagellar growth rate has been shown to be coordinated with cellular growth (2), there are no reports regarding the control of the length of the flagellar filament, whereas the length of the flagellar hook is regulated by FliK (1). In this work, we have shown that by providing more intracellular EspA subunits, we can increase the length of the filaments, suggesting that the amount of monomeric EspA produced in bacteria is the limiting factor, which is set for a defined filament length.

The identification of a central channel in the EspA filament strongly suggests that proteins are delivered from the bacteria to the host cell through this channel. As with the type III protein export involved in the assembly of the bacterial flagellum, it has been shown that assembly of the EspA filament is dependent on type III secretion, since mutants with mutations in NC components fail to secrete and assemble EspA filaments (53). In this report, we have shown that EspAEPEC and EspAEHEC can copolymerize in a biologically active filament and that newly synthesized EspA subunits are incorporated at the tip of the filament. Similarly, in 1970 Emerson et al. showed that flagellar elongation occurs by polymerization of flagellin subunits onto the distal tip of the filament (17). It is also noteworthy in this context that the type III Hrp pilus of the plant pathogen P. syringae, which is in fact a poly-needle, also shows distal extension (40).

In this study we provided the first experimental evidence that proteins travel along the hollow EspA filament before being released from the bacterium into the medium. In addition, we have shown that, like flagella, EspA filaments polymerize from their tips. Taken together with the fact that flagella can also translocate virulence determinants into the host cell (56), the results presented in this report clearly support the idea that the EspA filament and the virulence TTSS have common roots and probably evolved from the flagellum and the flagellar TTSS. We hope that by gaining a better understanding of how EspA filaments are polymerized, we will be able to generate a testable hypothesis as to how EspA filaments are eliminated following protein translocation and prior to intimate attachment.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by grants from the Wellcome Trust and the BBSRC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aizawa, S. I. 2001. Bacterial flagella and type III secretion systems. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 202:157-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aizawa, S. I., and T. Kubori. 1998. Bacterial flagellation and cell division. Genes Cells 3:625-634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Batchelor, M., J. Guignot, A. Patel, N. Cummings, J. Cleary, S. Knutton, D. W. Holden, I. Connerton, and G. Frankel. 2004. Involvement of the intermediate filament protein cytokeratin-18 in actin pedestal formation during EPEC infection. EMBO Rep. 5:104-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campellone, K., D. Robbins, and J. Leong. 2004. EspF(U) is a translocated EHEC effector that interacts with Tir and N-WASP and promotes Nck-independent actin assembly. Dev. Cell 7:217-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cleary, J., L. C. Lai, R. K. Shaw, A. Straatman-Iwanowska, M. S. Donnenberg, G. Frankel, and S. Knutton. 2004. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) adhesion to intestinal epithelial cells: role of bundle-forming pili (BFP), EspA filaments and intimin. Microbiology 150:527-538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cornelis, G., and F. Van Gijsegem. 2000. Assembly and function of type III secretory systems. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:735-774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Creasey, E. A., D. Friedberg, R. K. Shaw, T. Umanski, S. Knutton, I. Rosenshine, and G. Frankel. 2003. CesAB is an enteropathogenic Escherichia coli chaperone for the type-III translocator proteins EspA and EspB. Microbiology 149:3639-3647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dahan, S., S. Knutton, R. K. Shaw, V. F. Crepin, G. Dougan, and G. Frankel. 2004. The transcriptome of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157 adhering to eukaryotic plasma membranes. Infect. Immun. 72:5452-5459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daniell, S. J., R. M. Delahay, R. K. Shaw, E. L. Hartland, M. J. Pallen, F. Booy, F. Ebel, S. Knutton, and G. Frankel. 2001. The coiled-coil domain of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli type III secreted protein EspD is involved in EspA filament-mediated cell attachment and hemolysis. Infect. Immun. 69:4055-4064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daniell, S. J., E. Kocsis, E. Morris, S. Knutton, F. P. Booy, and G. Frankel. 2003. 3D structure of EspA filaments from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 49:301-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daniell, S. J., N. Takahashi, R. Wilson, D. Friedberg, I. Rosenshine, F. P. Booy, R. K. Shaw, S. Knutton, G. Frankel, and S. Aizawa. 2001. The filamentous type III secretion translocon of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Cell. Microbiol. 3:865-871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delahay, R. M., S. Knutton, R. K. Shaw, E. L. Hartland, M. J. Pallen, and G. Frankel. 1999. The coiled-coil domain of EspA is essential for the assembly of the type III secretion translocon on the surface of enteropathogenic E. coli. J. Biol. Chem. 274:35969-35974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deng, W., J. L. Puente, S. Gruenheid, Y. Li, B. A. Vallance, A. Vazquez, J. Barba, J. A. Ibarra, P. O'Donnell, P. Metalnikov, K. Ashman, S. Lee, D. Goode, T. Pawson, and B. B. Finlay. 2004. Dissecting virulence: systematic and functional analyses of a pathogenicity island. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:3597-3602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ebel, F., T. Podzadel, M. Rohde, A. U. Kresse, S. Kramer, C. Deibel, C. A. Guzman, and T. Chakraborty. 1998. Initial binding of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli to host cells and subsequent induction of actin rearrangements depend on filamentous EspA-containing surface appendages. Mol. Microbiol. 30:147-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elliott, S. J., E. O. Krejany, J. L. Mellies, R. M. Robins-Browne, C. Sasakawa, and J. B. Kaper. 2001. EspG, a novel type III system-secreted protein from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli with similarities to VirA of Shigella flexneri. Infect. Immun. 69:4027-4033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elliott, S. J., L. A. Wainwright, T. K. McDaniel, K. G. Jarvis, Y. K. Deng, L. C. Lai, B. P. McNamara, M. S. Donnenberg, and J. B. Kaper. 1998. The complete sequence of the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli E2348/69. Mol. Microbiol. 28:1-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emerson, S. U., K. Tokuyasu, and M. I. Simon. 1970. Bacterial flagella: polarity of elongation. Science 169:190-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fernandez, L. A., and J. Berenguer. 2000. Secretion and assembly of regular surface structures in Gram-negative bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 24:21-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frankel, G., A. D. Phillips, J. Adu-Bobie, D. C. A. Candy, G. Douce, and G. Dougan. 1996. Intimin-mediated adherence to epithelial cells. Rev. Microbiol. Sao Paulo 27:99-103. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frankel, G., A. D. Phillips, I. Rosenshine, G. Dougan, J. B. Kaper, and S. Knutton. 1998. Enteropathogenic and enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli: more subversive elements. Mol. Microbiol. 30:911-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frankel, G., A. D. Phillips, L. R. Trabulsi, S. Knutton, G. Dougan, and S. Matthews. 2001. Intimin and the host cell—is it bound to end in Tir(s)? Trends Microbiol. 9:214-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garmendia, J., A. D. Phillips, M. F. Carlier, Y. Chong, S. Schuller, O. Marches, S. Dahan, E. Oswald, R. K. Shaw, S. Knutton, and G. Frankel. 2004. TccP is an enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 type III effector protein that couples Tir to the actin-cytoskeleton. Cell. Microbiol. 6:1167-1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hueck, C. J. 1998. Type III protein secretion systems in bacterial pathogens of animals and plants. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:379-433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hultgren, S. J., and S. Normark. 1991. Biogenesis of the bacterial pilus. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1:313-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hyman, H. C., and S. Trachtenberg. 1991. Point mutations that lock Salmonella typhimurium flagellar filaments in the straight right-handed and left-handed forms and their relation to filament superhelicity. J. Mol. Biol. 220:79-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ide, T., S. Laarmann, L. Greune, H. Schillers, H. Oberleithner, and M. A. Schmidt. 2001. Characterization of translocation pores inserted into plasma membranes by type III-secreted Esp proteins of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Cell. Microbiol. 3:669-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jerse, A. E., and J. B. Kaper. 1991. The eae gene of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli encodes a 94-kilodalton membrane protein, the expression of which is influenced by the EAF plasmid. Infect. Immun. 59:4302-4309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jin, Q., and S. Y. He. 2001. Role of the Hrp pilus in type III protein secretion in Pseudomonas syringae. Science 294:2556-2558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jin, Q., W. Hu, I. Brown, G. McGhee, P. Hart, A. L. Jones, and S. Y. He. 2001. Visualization of secreted Hrp and Avr proteins along the Hrp pilus during type III secretion in Erwinia amylovora and Pseudomonas syringae. Mol. Microbiol. 40:1129-1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kenny, B., R. DeVinney, M. Stein, D. J. Reinscheid, E. A. Frey, and B. B. Finlay. 1997. Enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) transfers its receptor for intimate adherence into mammalian cells. Cell 91:511-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kenny, B., and M. Jepson. 2000. Targeting of an enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) effector protein to host mitochondria. Cell. Microbiol. 2:579-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kenny, B., L. C. Lai, B. B. Finlay, and M. S. Donnenberg. 1996. EspA, a protein secreted by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli, is required to induce signals in epithelial cells. Mol. Microbiol. 20:313-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knutton, S., T. Baldwin, P. H. Williams, and A. S. McNeish. 1989. Actin accumulation at sites of bacterial adhesion to tissue culture cells: basis of a new diagnostic test for enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 57:1290-1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knutton, S., D. R. Lloyd, and A. S. McNeish. 1987. Adhesion of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli to human intestinal enterocytes and cultured human intestinal mucosa. Infect. Immun. 55:69-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knutton, S., I. Rosenshine, M. J. Pallen, I. Nisan, B. C. Neves, C. Bain, C. Wolff, G. Dougan, and G. Frankel. 1998. A novel EspA-associated surface organelle of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli involved in protein translocation into epithelial cells. EMBO J. 17:2166-2176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kresse, A. U., M. Rohde, and C. A. Guzman. 1999. The EspD protein of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli is required for the formation of bacterial surface appendages and is incorporated in the cytoplasmic membranes of target cells. Infect. Immun. 67:4834-4842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuwajima, G. 1988. Construction of a minimum-size functional flagellin of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 170:3305-3309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lai, L. C., L. A. Wainwright, K. D. Stone, and M. S. Donnenberg. 1997. A third secreted protein that is encoded by the enteropathogenic Escherichia coli pathogenicity island is required for transduction of signals and for attaching and effacing activities in host cells. Infect. Immun. 65:2211-2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levine, M. M., E. J. Berquist, D. R. Nalin, D. H. Waterman, R. B. Hornick, C. R. Young, S. Stoman, and B. Rowe. 1978. Escherichia coli that cause diarrhoea but do not produce heat-labile or heat-stable enterotoxins and are non-invasive. Lancet i:119-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li, C. M., I. Brown, J. Mansfield, C. Stevens, T. Boureau, M. Romantschuk, and S. Taira. 2002. The Hrp pilus of Pseudomonas syringae elongates from its tip and acts as a conduit for translocation of the effector protein HrpZ. EMBO J. 21:1909-1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Macnab, R. M. 2003. How bacteria assemble flagella. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57:77-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maki-Yonekura, S., K. Yonekura, and K. Namba. 2003. Domain movements of HAP2 in the cap—filament complex formation and growth process of the bacterial flagellum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:15528-15533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marches, O., T. N. Ledger, M. Boury, M. Ohara, X. Tu, F. Goffaux, J. Mainil, I. Rosenshine, M. Sugai, J. De Rycke, and E. Oswald. 2003. Enteropathogenic and enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli deliver a novel effector called Cif, which blocks cell cycle G2/M transition. Mol. Microbiol. 50:1553-1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matsuzawa, T., A. Kuwae, S. Yoshida, C. Sasakawa, and A. Abe. 2004. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli activates the RhoA signaling pathway via the stimulation of GEF-H1. EMBO J. 23:3570-3582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McDaniel, T. K., K. G. Jarvis, M. S. Donnenberg, and J. B. Kaper. 1995. A genetic locus of enterocyte effacement conserved among diverse enterobacterial pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:1664-1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McNamara, B. P., and M. S. Donnenberg. 1998. A novel proline-rich protein, EspF, is secreted from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli via the type III export pathway. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 166:71-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Minamino, T., and K. Namba. 2004. Self-assembly and type III protein export of the bacterial flagellum. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 7:5-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mundy, M., L. Petrovska, K. Smollett, N. Simpson, R. K. Wilson, J. Yu, X. Tu, I. Rosenshine, S. Clare, G. Dougan, and G. Frankel. 2004. Identification of a novel Citrobacter rodentium type III secreted protein, EspI, and the roles of this and other secreted proteins in infection. Infect. Immun. 72:2288-2302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nataro, J. P., and J. B. Kaper. 1998. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:142-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Neves, B. C., R. K. Shaw, G. Frankel, and S. Knutton. 2003. Polymorphisms within EspA filaments of enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 71:2262-2265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schlosser-Silverman, E., M. Elgrably-Weiss, I. Rosenshine, R. Kohen, and S. Altuvia. 2000. Characterization of Escherichia coli DNA lesions generated within J774 macrophages. J. Bacteriol. 182:5225-5230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tu, X., I. Nisan, C. Yona, E. Hanski, and I. Rosenshine. 2003. EspH, a new cytoskeleton-modulating effector of enterohaemorrhagic and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 47:595-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wilson, R. K., R. K. Shaw, S. Daniell, S. Knutton, and G. Frankel. 2001. Role of EscF, a putative needle complex protein, in the type III protein translocation system of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Cell. Microbiol. 3:753-762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yonekura, K., S. Maki-Yonekura, and K. Namba. 2003. Complete atomic model of the bacterial flagellar filament by electron cryomicroscopy. Nature 424:643-650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yonekura, K., S. Maki-Yonekura, and K. Namba. 2002. Growth mechanism of the bacterial flagellar filament. Res. Microbiol. 153:191-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Young, G. M., D. H. Schmiel, and V. L. Miller. 1999. A new pathway for the secretion of virulence factors by bacteria: the flagellar export apparatus functions as a protein-secretion system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:6456-6461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]