Abstract

FNR is a global transcriptional regulator that controls anaerobic gene expression in Escherichia coli. Through the use of a number of approaches it was shown that fnr gene expression is reduced approximately three- to fourfold in E. coli strain MC4100 compared with the results seen with strain MG1655. This reduction in fnr expression is due to the insertion of IS5 (is5F) in the regulatory region of the gene at position −41 relative to the transcription initiation site. Transcription of the fnr gene nevertheless occurs from its own promoter in strain MC4100, but transcript levels are reduced approximately fourfold compared with those seen with strain MG1655. Remarkably, in strains bearing is5F the presence of Hfq prevents IS5-dependent transcriptional silencing of fnr expression. Thus, an hfq mutant of MC4100 is devoid of FNR protein and has the phenotype of an fnr mutant. In strain MG1655, or a derivative of MC4100 lacking is5F, mutation of hfq had no effect on fnr transcript levels. This finding indicates that IS5 mediates the effect of Hfq on fnr expression in MC4100. Western blot analysis revealed that cellular levels of FNR were reduced threefold in strain MC4100 compared with strain MG1655 results. A selection of FNR-dependent genes fused to lacZ were analyzed for the effects of reduced FNR levels on anaerobic gene expression. Expression of some operons, e.g., focA-pfl and fdnGHJI, was unaffected by reduction in the level of FNR, while the expression of other genes such as ndh and nikA was clearly affected.

The genomes of Escherichia coli K-12 strains contain variable numbers of insertion sequences (IS). These are mobile bacterial DNA elements that can transpose to many sites on the chromosome, and their activity can result in various genetic rearrangements. One of the most common IS elements is the 1,195-bp IS5 (9), which can be localized to a number of conserved positions in the genome. IS5 elements range in copy number from 11 in the sequenced E. coli strain MG1655 (1) to 23 in strain W3110 (45). Indeed, the locations of the IS5 elements in the chromosome of W3110 have been named is5A through is5W.

This study demonstrates that an IS5 element (termed is5F) is present in the regulatory region of the fnr gene of some E. coli strains, including MC4100, which, remarkably, causes an approximately threefold reduction in FNR concentration. FNR is a global transcriptional regulator that controls gene expression in response to the transition between aerobic and anaerobic growth and is a member of the CRP-FNR superfamily (11, 18). Current evidence indicates that FNR senses dioxygen directly through a redox-sensitive [4Fe-4S] cluster (14, 17). Global gene expression profiling analysis of MC4100 suggests that as many as 700 genes in E. coli are regulated directly or indirectly by FNR (26).

Expression of fnr is more or less constitutive and is achieved through negative autogenous control (25, 30). The consequence of this is that cellular FNR levels remain relatively constant. Differential responses to anoxia of particular gene sets are therefore determined by the binding affinities and locations of FNR recognition sequences in the promoters of the respective genes. Furthermore, many FNR-regulated genes are also subject to dual regulation by a further regulator. For example, expression of the structural gene operon narGHJI, encoding respiratory nitrate reductase, is activated by FNR anaerobically and expression is further increased in response to nitrate (41). Altering the concentration of FNR in the cell by increasing or decreasing expression of the fnr gene might therefore have significant impacts on global gene expression and ultimately on general cell physiology.

The synthesis of one of the key anaerobic enzymes, pyruvate formate-lyase (PFL), is controlled by FNR (reviewed in reference 32). The pfl gene is transcribed in an operon with the focA gene. Multiple, coordinately regulated promoters control transcription of the operon, and expression is subject to regulation by a number of transcription factors, including FNR (6, 7, 15, 16, 28, 31, 37). In an fnr mutant, induction of anaerobic focA-pfl gene expression is significantly reduced.

In the present study, while screening mutations for their effects on focA-pfl expression it was shown that an E. coli MC4100 hfq mutant also exhibited reduced levels of anaerobic focA-pfl induction. Hfq has RNA chaperone activity, and it has recently been implicated in the regulation of gene expression through mediating the action of small RNAs (44, 49, 50). Surprisingly, however, detailed analysis of the MC4100 hfq mutant revealed that the effect of the hfq mutation on focA-pfl expression was indirect and that in fact the mutation prevented fnr expression. Consequently, the lack of FNR in the MC4100 hfq mutant was the actual cause of impaired anaerobic induction of focA-pfl expression. Moreover, Hfq-dependent expression of fnr in strain MC4100 was due to the IS5 insertion in the fnr regulatory region. Levels of FNR in E. coli strains lacking IS5 upstream of the fnr gene were unaffected by the hfq mutation. Taken together, these findings indicate that there is strain-dependent variability in FNR levels in E. coli K-12 caused by is5F insertion and that only in those strains containing this insertion sequence is fnr transcription dependent on Hfq.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and phage and culture conditions.

Bacterial strains, plasmids and phages used in this study are listed in Table 1. Bacteria were grown routinely in Luria broth (LB) (27). When required, glucose was added to achieve a final concentration of 20 mM. Growth in minimal medium was performed in M9 (23) supplemented with 0.001% (wt/vol) thiamine and 5 mM MgSO4. The carbon source was either glycerol added to achieve a final concentration of 0.8% (wt/vol) or l-arabinose added to achieve a final concentration of 0.5% (wt/vol). When required, nitrate was added to achieve a final concentration of 10 mM. Aerobic cultures were grown in flasks filled maximally to 1/10 of their volume, while anaerobic cultures were grown in stoppered bottles filled to the top with medium. Media and buffers for work with lambda and P1 were prepared as described previously (29). Cells for enzyme assays and RNA preparation were harvested in the mid-exponential phase of growth.

TABLE 1.

Strains, plasmids, and phages used in this study

| Strain, phage, or plasmid | Genotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strain | ||

| MC4100 | F−araD139 Δ(argF-lac)U169 ptsF25 deoC1 relA1 flbB530 rpsL150 λ− | 3 |

| MG1655 | Also known as NCM3629 prototroph | 38 |

| MG1655 | Also known as NCM3105 ilvG rfb-50 rph-1 fnr-267 eut | 38 |

| GS081 | Like MC4100, but hfq-1::Ω(Cmr) | 49 |

| RM4100 | Like MC4100, but with wild-type fnr gene regulatory region | This work |

| RM101 | Like MC4100, but Δ fnr | 31 |

| RM123 | Like MC4100, but recA56 λRM123 | 29 |

| RM135 | RM102 λRM123 | 29 |

| RM1010 | Like MC4100, but hfq-1::Ω (Cmr) | This work |

| RM1011 | Like MG1655 (NCM3629), but hfq-1::Ω (Cmr) | This work |

| HYD72K1 | MC4100 nikA::MudI (KanrlacZ) | M. Mandrand-Berthelot |

| JRG1941 | RK4353 λRS5 aspA′-′lacZ | 47 |

| JRG1988 | MC1000 λG211 (λRS5 ndh-lacZ) | 39 |

| Plasmid or phage | ||

| pCH21 | Aprfnr+ | 13 |

| pCrp | Aprcrp+ | S. Busby |

| p29 | CmrfocA+pfl+act+ | 4 |

| pRS551 | Apr KanrlacZ′ lacY+lacA+ | 36 |

| pRM900 | pRS551 Φfnr′-lacZ 246-bp insert including fnr upstream regulatory region | This work |

| pRM901 | pRS551 Φfnr′-lacZ 94-bp insert from the fnr regulatory region | This work |

| pNK120 | pRS551 ΦfdnG′-lacZ | T. Palmer |

| λRS45 | lacZ′ lacY+lacA+imm21ind+ | 36 |

| λRM123 | λRS45 Φ(pfl′-′lacZ)1397(Hyb) | 29 |

| λRM900 | λRS45 Φfnr246′-′lacZ | This work |

| λRM901 | λRS45 Φfnr94′-lacZ | This work |

| λNK120 | λRS45 ΦfdnG′-lacZ | This work |

Antibiotics were added to achieve the following final concentrations: ampicillin, 75 μg ml−1; chloramphenicol, 15 μg ml−1; kanamycin, 50 μg ml−1; and tetracycline, 15 μg ml−1. Media were solidified by the inclusion of 1.5% (wt/vol) agar.

Plasmid and strain construction.

PCR amplification of the complete fnr regulatory region from within the 3′ end of the ogt gene to the 5′ end of the fnr gene was performed with oligonucleotides Fnr-Tr1 (5′-GGGGATCCATGAAGGTTATCTTTTGCTG-3′) and Fnr-Tr2 (5′-GGGGATCCGTATAATTCGCTTTTCCGGG-3′). This amplification delivered a 246-bp DNA fragment that was cloned into the BamHI site of pRS551 (36), delivering plasmid pRM900. To construct a derivative with a truncated fnr regulatory region extending from position −41 bp relative to the transcription initiation site to the 5′ end of the fnr gene, a 94-bp DNA fragment was amplified with oligonucleotides Fnr-Tr2 and Fnr-Tr3 (5′-GGGGATCCTTAGACTTACTTGCTCCC-3′) and cloned into the BamHI site of pRS551. This delivered plasmid pRM901 and lacked any IS5 DNA sequences. To transfer the transcriptional lacZ fusions in strains HYD72K1, JRG1941, and JRG1988 into other E. coli genetic backgrounds, phage P1 was grown on the donor strains, lysates were prepared, and the fusions were introduced into recipient strains by P1-mediated transduction according to the method described in reference 23. Successful introduction of the fusion was selected for by acquisition of kanamycin resistance in the case of nikA::MudI and screening for a Lac+ phenotype with λRS5 aspA′-′lacZ and ndh-lacZ. RM4100 was constructed by transducing RM101 (Δfnr) to an fnr+ genotype by the use of a P1 lysate grown on MG1655 and selecting for growth anaerobically on M9 minimal medium with glycerol and nitrate (20). The resulting strain was unable to grow on l-arabinose as the sole carbon source.

Transfer of lacZ fusions to λRS45 and thence to the λatt site on the chromosome was performed exactly as described previously (29, 36). All lacZ fusions were introduced in single copy into the λatt site, with the exception of the nikA-lacZ derivative, which was a single-copy fusion in the nikA structural gene.

Analysis of RNA transcripts.

Total RNA was isolated from aerobic and anaerobic cultures grown to mid-exponential phase by the use of a QIAGEN RNeasy kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (QIAGEN manual; QIAGEN Ltd., Crawley, United Kingdom). Primer extension analysis was performed exactly as described previously (30) with 25 μg of total RNA and 0.2 pmol of 32P-labeled oligonucleotide Fnr-F2 (5′-GGCTGATGCTGCAATCCTGGCAATGG-3′).

S1 nuclease mapping of pfl transcripts was performed according to the method described in reference 12 by the use of 50 μg of total RNA. The DNA fragment used for hybridization was derived from plasmid p29 (4). Labeling of this fragment with [γ-32P]ATP, as well as treatment of the fragment prior to S1 analysis, was carried out exactly as described previously (30).

RT-PCR was performed with 2.5 μg of total RNA by the use of an Access RT-PCR system (Promega, Southampton, United Kingdom). RNA samples were treated with RNase-free DNase and repurified prior to use in RT-PCR experiments. The conditions used for the RT-PCR were exactly as described by the manufacturer. The oligonucleotides used for RT-PCR were as follows: Fnr-1 (5′-GGAAAAGCGAATTATACGGCG-3′) and Fnr-2 (5′-GGGCCAGCGCATCGTTATTTTCG-3′); Fnr-F1 (5′-CACAACCGCCAGACTGAATGCGCC-3′) and Fnr-F3 (5′-GGGTTTTCAAATAGATAGAC-3′); and Crp-1 (5′-GGACGTCACATTACCGTGCAGTACAGTTG-3′) and Crp-2 (5′-GGTTGTTTTGCCAGATTCAGCAGAGTCTG-3′).

Other methods.

Chromosomal DNA was isolated according to the method of Sambrook et al. (27). Beta-galactosidase enzyme activity was assayed in cultures of exponentially growing cells, and the specific activity was calculated as described previously (23). Values reported are the averages of at least three independent experiments performed in triplicate, and the standard error of the values reported was not more than 15%.

Formate dehydrogenase (FDH-N) and nitrate reductase (NR) enzyme activities were performed as described previously (10).

FNR was purified according to the method of Kaiser and Sawers (15). Protein concentrations were determined using bovine serum albumin as the standard by the method of Lowry et al. (21). Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of proteins was performed as described previously (19), and Western blotting was carried out according to Towbin et al. (43). Anti-FNR antiserum (a kind gift from G. Unden, Mainz, Germany) was diluted 1,500-fold before use, and the antibody-antigen reaction was visualized using the ECL chemiluminescent method (Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden) exactly as recommended by the manufacturer. Densitometric analyses were performed using SynGene GeneTools analysis software.

RESULTS

Strain-dependent differences in anaerobic regulation of focA-pfl operon expression by Hfq.

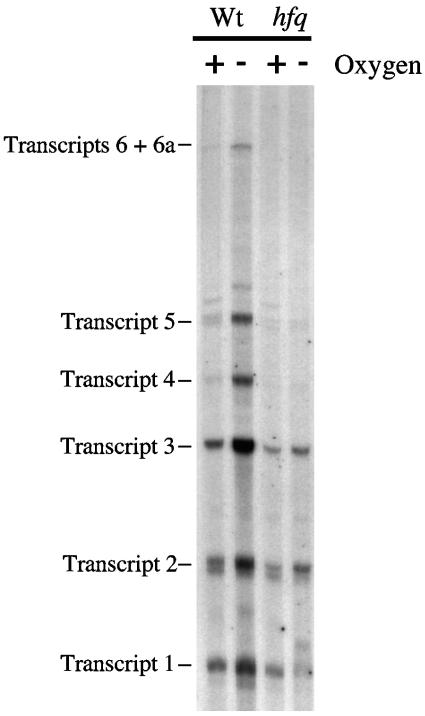

Multiple promoters control transcription of the focA-pfl operon in E. coli. Anaerobic induction of operon expression is regulated by the FNR and ArcA transcription factors (7, 15, 28, 30). During a survey of mutant alleles of E. coli MC4100 it was noted that an hfq mutation reduced anaerobic induction of pfl expression (Fig. 1). The coordinate induction of the multiple pfl transcripts normally observed under anaerobic conditions in the wild type was significantly reduced in the MC4100 hfq mutant, GS081. In particular, transcripts 4, 5, and 6 were no longer detectable in the hfq mutant and the anaerobic levels of transcripts 2 and 3, although reduced compared to the wild-type levels, still afforded some anaerobic induction of pfl transcription (Fig. 1). This phenotype is also observed in an fnr mutant (28, 30). Transduction of the hfq::Ω (Cmr) allele into a “clean” strain MC4100 genetic background, delivering strain RM1010, yielded results indistinguishable from those found with the GS081 mutant (data not shown). Analysis of pfl-lacZ expression confirmed that anaerobic induction of gene expression was reduced approximately eightfold in the hfq mutant RM1010 compared to the results seen with its isogenic wild-type parent strain MC4100 (Table 2).

FIG. 1.

Impaired anaerobic induction of the multiple focA-pfl operon transcripts in strain MC4100 hfq. Total RNA was isolated from strains MC4100 (Wt) and GS081 (hfq) after aerobic and anaerobic growth in LB plus glucose. After S1 nuclease treatment (see Materials and Methods) the transcripts were separated in a denaturing 4% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gel. The locations of the transcripts are indicated.

TABLE 2.

Expression of a pfl-lacZ fusion is Hfq dependent in strain MC4100 but not in strain MG1655

| Straina | Beta-galactosidase enzyme activity (Miller units ± SD)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Aerobic | Anaerobic | |

| MC4100 | 200 ± 28 | 7,775 ± 310 |

| RM1010 (hfq) | 150 ± 12 | 1,020 ± 60 |

| RM135 (fnr) | 145 ± 13 | 980 ± 115 |

| MG1655 | 160 ± 6 | 7,646 ± 610 |

| RM1011 (hfq) | 240 ± 35 | 5,800 ± 690 |

| MG1655 (fnr) | 230 ± 10 | 1,265 ± 112 |

All strains contain a chromosomal copy of λRM123.

The effects of the hfq mutation on both pfl operon transcription and expression of the pfl-lacZ fusion were reminiscent of the phenotypes observed in a fnr mutant (see Table 2) (28, 29, 30). Moreover, the activities of the anaerobically induced, nitrate- and FNR-regulated enzymes formate dehydrogenase N (FDH-N) and nitrate reductase (NR) were undetectable in crude extracts of a MC4100 hfq mutant compared to activities in extracts of MC4100 of 0.1 μmol of formate oxidized min−1 mg−1 of protein for FDH-N and 0.99 μmol of nitrate reduced min−1 mg−1 of protein for NR. These results confirm that the effect of the hfq mutation on pfl transcription was indirect and a result of reduced FNR synthesis.

To determine whether the effect of the hfq mutation on pfl expression was also observed for other E. coli strains, the pfl-lacZ fusion was introduced into the fnr+ derivative of strain MG1655 (prototroph) and the fnr derivative of MG1655 (NCM3105) (38). Levels of pfl expression after aerobic and anaerobic growth in MG1655 were very similar to those observed for strain MC4100 (Table 2). Similarly, the fnr mutation resulted in an approximately sixfold reduction in levels of pfl-lacZ expression after growth of cultures anaerobically. Introduction of the hfq::Ω mutation into wild-type MG1655 λRM123 (pfl-lacZ) resulted in an approximately 20% decrease in expression after anaerobic growth (Table 2). These results indicate that pfl expression is not dependent on the presence of Hfq in strain MG1655.

Hfq is required for fnr expression in strain MC4100.

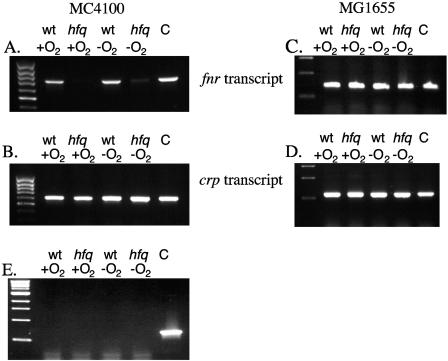

To determine whether expression of fnr was affected by the hfq mutation in strain MC4100, total RNA was isolated from MC4100 and its hfq derivative strain RM1010 after aerobic and anaerobic growth and the presence of the fnr transcript was detected by reverse transcription followed by PCR (RT-PCR). RT-PCR of total RNA samples isolated from wild-type MC4100 grown either aerobically or anaerobically delivered a cDNA product of the expected size (712 bp) and demonstrated that the levels of the fnr transcript were similar under these conditions (Fig. 2A). This result is in agreement with previous findings (25, 40). However, when the same amount of total RNA isolated from RM1010 (hfq) was used, essentially no PCR product was detected (Fig. 2A). This indicates that the level of the fnr transcript in the hfq derivative of strain MC4100 is dramatically reduced.

FIG. 2.

RT-PCR analysis of fnr and crp transcripts in strain MC4100 and MG1655 hfq mutants. Total RNA was isolated from E. coli strains grown aerobically and anaerobically in LB plus glucose, and RT-PCR analysis was performed (see Materials and Methods). Oligonucleotides Fnr-1 and Fnr-2 were used to detect the 712-base fnr transcript (panels A, C, and E); oligonucleotides Crp-1 and Crp-2 were used to detect the 590-base crp transcript (panels B and D). Panel E represents a control experiment in which the RNA samples were from strain MC4100; the oligonucleotides were Fnr-1 and Fnr-2, but reverse transcriptase was omitted from the reactions. Lanes labeled C were controls in which chromosomal DNA, rather than RNA, was used as a template. wt designates the wild type.

Control experiments using oligonucleotides specific for the crp gene delivered the anticipated 590 bp (Fig. 2B), and the levels of transcript were similar, both aerobically and anaerobically and between strains MC4100 and RM1010 (hfq). RT-PCR experiments lacking reverse transcriptase showed no specific product for the fnr gene (Fig. 2E).

Analysis of fnr transcripts by RT-PCR in strain MG1655 revealed that in this strain the hfq mutation had no effect on transcript levels (Fig. 2C). This result indicates that Hfq regulates fnr transcript levels in strain MC4100 but not in strain MG1655. A control experiment examining crp expression revealed that as in strain MC4100, crp expression was unaffected by the hfq mutation (Fig. 2D).

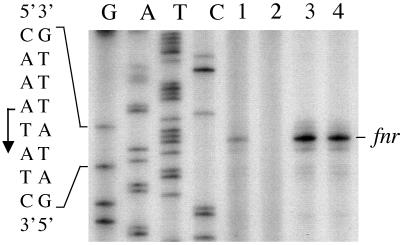

Determination of the initiation site of fnr transcription in strains MC4100 and MG1655 by primer extension demonstrated that the same transcription initiation site was used in both strains (Fig. 3) and that this site is the same as that determined previously (8, 35). However, compared with transcript levels in strain MG1655, the levels were reduced between three- to fourfold in strain MC4100 (Fig. 3), as determined by densitometric quantification. Whereas in strain MG1655 the hfq mutation had no effect on fnr transcript levels, in agreement with the RT-PCR results, no detectable transcription initiation could be detected in strain RM1010 (MC4100 hfq).

FIG. 3.

Transcription initiation of the fnr gene is silenced in an MC4100 hfq mutant. Total RNA was isolated from anaerobically grown strains. Primer extension reactions with oligonucleotide Fnr-F2 were performed as described in Materials and Methods. Identical amounts of each reaction mixture were separated on a denaturing 6% polyacrylamide gel. Lane 1, strain MC4100 (wild type); lane 2, strain RM1010 (MC4100 hfq); lane 3, strain MG1655 (wild type); lane 4, strain RM1011 (MG1655 hfq). The precise location of the transcription initiation site is shown on the left side of the panel.

Taken together, these findings indicate that the level of fnr transcripts is dependent on the presence of Hfq in strain MC4100 but not in strain MG1655. Furthermore, fnr transcripts are less abundant in strain MC4100 than in strain MG1655.

IS5 is inserted within the fnr regulatory region in MC4100.

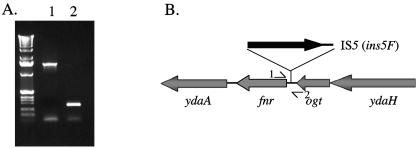

To determine how Hfq influences fnr expression in MC4100, the promoter-regulatory region of the fnr gene was amplified from chromosomal DNA by PCR to determine the DNA sequence in both MC4100 strain and strain MG1655. Oligonucleotide Fnr-Tr1 hybridized in the extreme 3′ end of the ogt gene, which is located immediately upstream of fnr (35), and Fnr-Tr2 hybridized within the 5′ portion of the fnr gene. The amplified DNA product was 246 bp when strain MG1655 chromosomal DNA was used as the template (Fig. 4A, lane 2). DNA sequence analysis of the fragment amplified from strain MG1655 yielded a sequence identical to that published by Blattner et al. (1). Surprisingly, however, strain MC4100 chromosomal DNA delivered a product of ∼1.4 kb (Fig. 4A, lane 1). Sequence analysis of this DNA fragment revealed that the first 67 bp of sequence upstream of the fnr gene AUG codon were identical to those of strain MG1655. The next 1,195 bp were identical to the insertion element IS5 (9), with the gene ins5A having the opposite orientation to the fnr gene (Fig. 4B). E. coli strains bear various numbers of copies of IS5, with a maximum of 23 copies identified in strain W3110 (45). The locations of the IS5 elements have been determined in the chromosome of W3110, and they have been named is5A through is5W. The IS5 element located upstream of fnr is is5F. PCR analysis of the fnr regulatory region of strain W3110 determined that like that of strain MC4100, it also has an IS5 element insertion (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Analysis of the IS5 insertion element in the fnr regulatory region of MC4100. (A) PCR amplification of the fnr regulatory region from strains MC4100 (lane 1) and MG1655 (lane 2) was performed using chromosomal DNA as the template. The oligonucleotides used were Fnr-Tr1 and Fnr-Tr2. (B) Schematic representation of the fnr locus on the chromosome of strain MC4100. The numerals represent the locations of oligonucleotides used in the PCR experiment shown in panel A. 1, Fnr-Tr1; 2, Fnr-Tr-2. The location of the ins5A gene, encoding the transposase of IS5, is represented by the thick black arrow.

IS5 inserts into the chromosome nonrandomly and recognizes the target sequence C/T T A/T G (9). The sequence TTAG in the fnr regulatory sequence (Fig. 5) is the recognition sequence of is5F and is duplicated by the insertion. The fnr sequence upstream of the insertion element in the chromosome of strain MC4100 is identical to that of the published sequence for strain MG1655 (1).

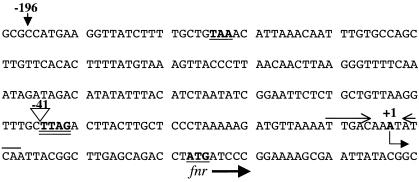

FIG. 5.

Nucleotide sequence of the fnr regulatory region. The stop codon of the upstream ogt gene and translation initiation codon of the fnr gene are shown in bold with a single underline. The insertion site of IS5 is shown by the inverted triangle, and the TTAG target site sequence is shown in bold and is double underlined. Transcription of the fnr gene initiates at an A residue, which is shown in bold and is identified with an angled arrow. The locations of the 5′ end of the DNA fragments used to construct the fnr-lacZ fusions λRM900 and λRM901 are designated −196 and −41, respectively. The two converging arrows above the DNA sequence and bordering the transcription initiation site signify a FNR-binding site.

Expression of fnr-lacZ fusions.

To determine the level of fnr expression that occurs with only the 41 bp of regulatory DNA sequence upstream of the transcription initiation site, a 94-bp DNA fragment generated from the point of IS5 insertion (including the IS5 recognition sequence but lacking any IS5 DNA sequence) (Fig. 5) to the start of the fnr gene was fused to lacZ and expression levels were determined for single-copy fusions in different E. coli strains (Table 3). Expression was approximately 20% higher anaerobically than the level seen with aerobically grown cultures. It was noted that after anaerobic growth, expression in an fnr mutant was increased twofold compared with the level in aerobic cultures, indicating that this short construct still exhibits negative autoregulation (25, 40). Expression levels were similar in strains MC4100 and MG1655. Notably, an hfq mutation had essentially no effect on expression of the truncated fnr-lacZ derivative for either strain (Table 3 and data not shown). This indicates that in accord with the transcript analyses, the fnr gene is expressed in the truncated promoter-regulatory region derivative and suggests that the consequence of the hfq mutation on fnr transcription is due to the insertion of IS5. Attempts to construct a lacZ fusion derivative including the IS5 element proved unsuccessful due to the high instability of the derivative.

TABLE 3.

Expression of fnr-lacZ fusions in different genetic backgrounds

| Strain | Beta-galactosidase enzyme activity (Miller units ± SD)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| λRM900 (Φfnr246′-′lacZ)

|

λRM901 (Φfnr94′-′lacZ)

|

|||

| Aerobic | Anaerobic | Aerobic | Anaerobic | |

| MC4100 | 1,170 ± 87 | 2,870 ± 344 | 430 ± 60 | 620 ± 65 |

| RM101 (MC4100 fnr) | 1,090 ± 62 | 4,220 ± 180 | 470 ± 50 | 900 ± 54 |

| MG1655 | 1,960 ± 254 | 2,440 ± 219 | 550 ± 80 | 460 ± 39 |

| MG1655 (fnr) | 2,410 ± 156 | 5,500 ± 577 | 560 ± 67 | 1,050 ± 84 |

| RM1011 (MG1655 hfq) | 1,180 ± 88 | 1,560 ± 132 | 750 ± 82 | 560 ± 61 |

Construction and analysis of an fnr-lacZ fusion including the complete ogt-fnr intergenic region revealed an expression pattern similar to that seen with the truncated fnr-lacZ derivative (Table 3). The main difference was that expression levels were between three- to fourfold higher in the full-length derivative. This observation correlates well with the three- to fourfold difference in fnr transcription levels between strains MC4100 and MG1655. Expression levels were generally higher in strain MG1655 than in strain MC4100, and the hfq mutation did not affect fnr expression. These data indicate that fnr expression is not dependent upon the presence of Hfq in strain MG1655. Moreover, they suggest that DNA sequences upstream of position −41 bp in the fnr regulatory region are important for maximal fnr expression. This latter observation is in accord with previous findings (25, 40, 42).

Taken together, the transcriptional fusion data corroborate the transcript analyses and demonstrate that the fnr promoter is active in strain MC4100. The data also indicate that the reduced level of expression of the fnr gene in MC4100 is due to insertion of the IS5 element in the regulatory region. Furthermore, the findings suggest that the hfq mutation causes “silencing” of fnr transcription and that this is a consequence of the IS5 insertion. Hfq has also recently been shown to function as an antisilencer in bgl operon expression (5).

Strain MC4100 has reduced levels of FNR protein compared with strain MG1655.

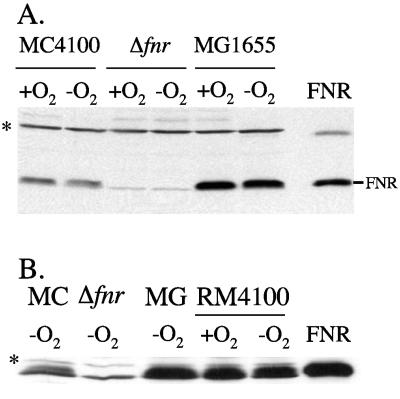

Immunological analysis of FNR in extracts of strain MC4100 revealed that essentially equivalent amounts of protein were present in cells grown aerobically and anaerobically (Fig. 6A). This finding is consistent with previous observations (46). Extracts of strain MG1655 had threefold higher levels of FNR than strain MC4100 extracts. This finding is consistent with the transcript analyses (Fig. 3).

FIG. 6.

Reduced levels of FNR protein in strains containing the IS5 element is5F. (A) Polypeptides in crude cell extracts of strains MC4100 (wild type), RM101 (Δfnr), and MG1655 (wild type), prepared after aerobic and anaerobic growth of cells in LB plus glucose, were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (12.5% polyacrylamide gels) and probed with anti-FNR antiserum. Aliquots of crude extracts (100 μg of protein) were loaded on the gel, and 50 ng of purified FNR was applied. The location of the FNR polypeptide is indicated. (B) Western blot with anti-FNR antiserum. For each experiment, 100 μg of protein in the case of crude extracts and 100 ng of purified FNR were applied (see panel A above). MC indicates a crude extract derived from strain MC4100 (wild type); Δfnr indicates a crude extract derived from strain RM101 (Δfnr); MG indicates a crude extract derived from strain MG1655 (wild type). The cross-reacting polypeptides (*) have not been identified but served as loading controls.

A derivative of strain MC4100 was constructed that lacked is5F and which had an fnr regulatory region identical to that in strain MG1655 (see Materials and Methods). PCR analysis of chromosomal DNA from the resulting strain, RM4100, confirmed that the IS5 element had been removed (data not shown). Western blot analysis of extracts derived from aerobically and anaerobically grown RM4100 revealed that levels of FNR were restored to those observed in MG1655 (Fig. 6B). This result confirms that in strain MC4100, the insertion of IS5 in the fnr regulatory region is solely responsible for the reduced levels of FNR protein observed.

Effects of reduced FNR levels on anaerobic gene expression.

The reduced level of FNR protein could have significant effects on anaerobic gene expression in strain MC4100. To test this, chromosomal lacZ fusion constructs of five FNR-regulated genes were chosen for analysis of their expression in strains RM4100 and MC4100 (Table 4). The FNR-regulated genes, including positively as well as negatively regulated genes, were chosen to include a range of expression levels together with one, fdn, that exhibits dual regulation in response to anaerobiosis and nitrate.

TABLE 4.

Effect of cellular FNR levels on expression of FNR-dependent genes

| Strain | Beta-galactosidase enzyme activity (Miller units ± SD)

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Φ(pfl-lacZ)

|

Φ(fdn-lacZ)

|

Φ(aspA-lacZ)

|

Φ(ndh-lacZ)

|

Φ(nikA-lacZ)

|

|||||||

| Aerobic | Anaerobic | Aerobic | Anaerobic | Anaerobic + nitrate | Aerobic | Anaerobic | Aerobic | Anaerobic | Aerobic | Anaerobic | |

| MC4100 (is5F) | 180 ± 20 | 7,870 ± 630 | 15 | 470 ± 61 | 2,980 ± 295 | 210 ± 28 | 1,075 ± 134 | 990 ± 89 | 655 ± 78 | 4 | 380 ± 45 |

| RM4100 | 210 ± 10 | 7,525 ± 715 | 35 | 570 ± 48 | 3,560 ± 425 | 150 ± 12 | 850 ± 125 | 320 ± 44 | 145 ± 7 | 4 | 810 ± 120 |

Essentially no significant differences in pfl-lacZ or aspA-lacZ expression levels between strains MC4100 and RM4100 were observed (Table 4). A minor but reproducible increase of 15% in fdn-lacZ expression in strain RM4100 was seen when cells were grown anaerobically with nitrate. The largest effect of low FNR levels on gene expression was observed with ndh-lacZ, where expression levels were reduced ∼5-fold in strain MC4100 compared with strain RM4100 results. Finally, anaerobic expression levels of a nikA-lacZ fusion were increased twofold in strain RM4100 relative to strain MC4100.

DISCUSSION

The major findings of this study are as follows: first, that in certain E. coli strains fnr expression is significantly reduced due to insertion of IS5 (is5F) in the regulatory region of the gene; second, that in such strains Hfq determines fnr expression, probably by preventing IS5-dependent silencing of the fnr promoter; and third, that a threefold reduction in the level of FNR has measurable effects on anaerobic expression of certain operons in strain MC4100.

In contrast to Salmonella species, which generally do not contain insertion elements, E. coli strains have variable numbers of copies of IS5 (45) and in an analysis of several strains in my laboratory I have determined that is5F is present in MC4100, W3110, and RK4353 derivatives whereas it is absent from MG1655 and MC1000 derivatives. This does not mean, however, that over the years of storage of strains that IS5 might not insert in this hotspot (see reference 24). Indeed, the is5F insertion sequence probably has been previously identified (2). A selection for mutants exhibiting aerobic up-regulation of the otherwise anaerobically regulated and nitrate-responsive narGHJI operon resulted in identification of a mutant with IS5 inserted in a location and orientation identical to that reported here; however, the authors did not report whether the original strain also possessed this insertion sequence. In contrast to what was observed here, Bonnefoy et al. (2) observed a 10-fold increase in fnr transcription in the mutant. It is conceivable that this phenotype resulted from an IS5 promoter “up” mutation which caused increased transcriptional polarity with fnr.

It has been reported (34) that IS5 normally exhibits only weak transcriptional polarity in the particular orientation observed upstream of fnr. This is consistent with the finding that in strain MC4100 the fnr promoter is still active, albeit with reduced activity compared with that of strain MG1655. This result was corroborated by transcript analysis. Remarkably, in the hfq mutant this fnr transcript was no longer detectable, suggesting that fnr was transcriptionally silent in the absence of Hfq.

The best-characterized example of transcriptional silencing in prokaryotes is provided by the bgl operon of E. coli (34). The mechanism is complex, but the consequence is that the operon is almost completely switched off in wild-type cells (33). Recent evidence indicates that Hfq has an antisilencing function that operates by reducing H-NS-dependent silencing of the cryptic bgl operon (5). In the case of fnr expression in strain MC4100 it is also only in the absence of Hfq that transcriptional silencing occurs. Nevertheless, this adds a further example of transcriptional silencing to the small list of those discovered so far in prokaryotes (48).

The precise mechanism by which Hfq prevents silencing of fnr transcription in strain MC4100 requires further investigation. One possible mechanism could involve the transposase encoded by the ins5A gene of IS5 binding to the terminal inverted repeat of the element (see reference 34) and thus occluding the fnr promoter. Hfq could prevent or reduce this occurring by stabilizing a transcript that traverses the end of the IS5 element. This can be tested by analyzing transcription across the boundary between the fnr regulatory region and IS5, as well as by determining whether the ins5A gene product can occlude fnr transcription in vitro.

Notwithstanding the effects of the hfq mutation on fnr expression in MC4100, truncation of the fnr regulatory region due to the insertion element has also revealed that DNA sequences important in controlling fnr gene expression extend beyond −64 bp. Although in the present study the IS5 insertion element foreshortened the fnr regulatory region to −41 bp, in an earlier study Spiro and Guest (40) fused the fnr regulatory region from the EcoRI site at position −64 bp to the lacZ gene and obtained β-galactosidase enzyme activities in the range found here for the truncated fusion derivative. Thus, in the ∼100 bp between the EcoRI site and the next gene ogt there are sequences important for the approximately threefold difference in expression observed with the full-length fnr-lacZ fusion and with fnr transcript levels (see also reference 42). It is presently unclear whether both cis and trans regulation is involved.

Reduced fnr expression is also reflected in the lower cellular level of FNR in strain MC4100, and this has measurable effects on gene expression. Despite examination of the expression of only five genes, it is evident that there was a range of responses to the lower level of the regulator. Some genes were unaffected in their expression, while for ndh the effect was more pronounced. Repression of ndh expression by FNR requires occupation of two sites, one a high-affinity and one a low-affinity site (22). The low-affinity site might be particularly sensitive to changes in FNR concentration. These differential effects perhaps reflect differences in binding site location and/or affinity of FNR for the respective binding site. It will be of interest to determine the overall consequences of reduced FNR levels on global anaerobic gene expression in strain MC4100 (26) compared with strain RM4100 and with strain MG1655.

Acknowledgments

My gratitude goes to Ray Dixon and Gigi Storz for useful discussions, to Fritz Unden for providing me with antiserum against FNR, and to Ray Dixon for his thoughtful comments on the manuscript. I am indebted to Steve Busby, Jeff Green, Chris Higgins, Marie-Andre Mandrand-Berthelot, Tracy Palmer, and Gigi Storz for providing strains and plasmids. This work was supported by the BBSRC via a competitive strategic grant to the John Innes Centre.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blattner, F. R., G. Plunkett III, et al. 1997. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science 277:1453-1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonnefoy, V., M. Fons, J. Ratouchniak, M.-C. Pascal, and M. Chippaux. 1988. Aerobic expression of the nar operon of Escherichia coli in a fnr mutant. Mol. Microbiol. 2:419-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casadaban, M. J., and S. N. Cohen. 1979. Lactose genes fused to exogenous promoters in one step using Mu-lac bacteriophage: in vivo probe for transcriptional control sequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:4530-4533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christiansen, L., and S. Pedersen. 1981. Cloning, restriction endonuclease mapping and post-transcriptional regulation of rpsA, the structural gene for ribosomal protein S1. Mol. Gen. Genet. 181:548-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dole, S., Y. Klingen, V. Nagarajavel, and K. Schnetz. 2004. The protease Lon and the RNA-binding protein Hfq reduce silencing of the Escherichia coli bgl operon by H-NS. J. Bacteriol. 186:2708-2716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drapal, N., and G. Sawers. 1995. Promoter 7 of the Escherichia coli pfl operon is a major determinant in the anaerobic regulation of expression by ArcA. J. Bacteriol. 177:5338-5341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drapal, N., and G. Sawers. 1995. Purification of ArcA and analysis of its specific interaction with the pfl promoter-regulatory region. Mol. Microbiol. 16:597-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eiglmeier, K., H. Honore, S. Iuchi, E. C. C. Lin, and S. T. Cole. 1989. Molecular genetic analysis of FNR-dependent promoters. Mol. Microbiol. 3:869-878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engler, J. A., and M. P. van Bree. 1981. The nucleotide sequence and protein-coding capability of the transposable element IS5. Gene 14:155-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Enoch, H. G., and R. L. Lester. 1975. The purification and properties of formate dehydrogenase and nitrate reductase from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 250:6693-6705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green, J., C. Scott, and J. R. Guest. 2001. Functional versatility in the CRP-FNR superfamily of transcription factors: FNR and FLP. Adv. Microbial. Physiol. 44:1-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hong, H.-J., M. S. B. Paget, and M. J. Buttner. 2002. A signal transduction system in Streptomyces coelicolor that activates the expression of a putative cell wall glycan operon in response to vancomycin and other cell wall-specific antibiotics. Mol. Microbiol. 44:1199-1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jamieson, D. J., and C. F. Higgins. 1984. Anaerobic and leucine-dependent expression of a peptide transport gene in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 160:131-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jordan, P. A., A. J. Thomson, E. T. Ralph, J. R. Guest, and J. Green. 1997. FNR is a direct oxygen sensor having a biphasic response curve. FEBS Lett. 416:349-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaiser, M., and G. Sawers. 1995. Fnr activates transcription from the P6 promoter of the pfl operon in vitro. Mol. Microbiol. 18:331-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaiser, M., and G. Sawers. 1995. Nitrate repression of the Escherichia coli pfl operon is mediated by the dual sensors NarQ and NarX and dual regulators NarL and NarP. J. Bacteriol. 177:3647-3655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khoroshilova, N., C. Popescu, E. Münck, H. Beinert, and P. J. Kiley. 1997. Iron-sulphur cluster disassembly in the FNR protein of Escherichia coli by O2: [4Fe-4S] to [2Fe-2S] conversion with loss of biological activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:6087-6092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Körner, H., H. J. Sofia, and W. G. Zumft. 2003. Phylogeny of the bacterial superfamily of Crp-Fnr transcription regulators: exploiting the metabolic spectrum by controlling alternative gene programs. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 27:559-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lambden, P. R., and J. R. Guest. 1976. Mutants of Escherichia coli K12 unable to use fumarate as an anaerobic electron acceptor. J. Gen. Microbiol. 97:145-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lowry, O. H., N. J. Rosebrough, A. L. Farr, and R. J. Randall. 1951. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 193:265-275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meng, W., J. Green, and J. R. Guest. 1997. FNR-dependent repression of ndh gene expression requires two upstream FNR-binding sites. Microbiology 143:1521-1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics, p. 352-355. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 24.Naas, T., M. Blot, W. M. Fitch, and W. Arber. 1995. Dynamics of IS-related genetic rearrangements in resting Escherichia coli K-12. Mol. Biol. Evol. 12:198-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pascal, M.-C., V. Bonnefoy, M. Fons, and M. Chippaux. 1986. Use of gene fusions to study the expression of fnr, the regulatory gene of anaerobic electron transfer in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 36:35-39. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salmon, K., S.-P. Hung, K. Mekjian, P. Baldi, G. W. Hatfield, and P. R. P. Gunsalus. 2003. Global gene expression profiling in Escherichia coli K12: the effects of oxygen availability and FNR. J. Biol. Chem. 278:29837-29855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, New York, N.Y.

- 28.Sawers, G. 1993. Specific transcriptional requirements for positive regulation of the anaerobically inducible pfl operon by ArcA and FNR. Mol. Microbiol. 10:737-747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sawers, G., and A. Böck. 1988. Anaerobic regulation of pyruvate formate-lyase from Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 170:5330-5336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sawers, G., and A. Böck. 1989. Novel transcriptional control of the pyruvate formate-lyase gene: upstream regulatory sequences and multiple promoters regulate anaerobic expression. J. Bacteriol. 171:2485-2498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sawers, G., and B. Suppmann. 1992. Anaerobic induction of pyruvate formate-lyase gene expression is mediated by the ArcA and FNR proteins. J. Bacteriol. 174:3474-3478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sawers, R. G., and D. P. Clark. July 2004, posting date. Fermentative pyruvate and acetyl CoA metabolism, chapter 3.5.3. In R. Curtiss III (Editor in Chief), EcoSal-Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology. [Online.] http://www.ecosal.org. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 33.Schnetz, K. 1995. Silencing of Escherichia coli bgl promoter by flanking sequence elements. EMBO J. 14:2545-2550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schnetz, K., and B. Rak. 1992. IS5: a mobile enhancer of transcription in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:1244-1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shaw, D. J., and J. R. Guest. 1982. Nucleotide sequence of the fnr gene and primary structure of the FNR protein of Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 10:6119-6130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simons, R. W., F. Houman, and N. Kleckner. 1987. Improved single and multicopy lac-based cloning vectors for protein and operon fusions. Gene 53:85-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sirko, A., E. Zehelein, M. Freundlich, and G. Sawers. 1993. Integration host factor is required for anaerobic pyruvate induction of pfl operon expression in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 175:5769-5777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Soupene, E., W. C. van Heeswijk, J. Plumbridge, V. Stewart, D. Bertenthal, H. Lee, G. Prasad, O. Paliy, P. Charernnoppakul, and S. Kustu. 2003. Physiological studies of Escherichia coli strain MG1655: growth defects and apparent cross-regulation of gene expression. J. Bacteriol. 185:5611-5626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spiro, S., R. E. Roberts, and J. R. Guest. 1989. FNR-dependent repression of the ndh gene of Escherichia coli and metal ion requirements for FNR-regulated gene expression. Mol. Microbiol. 3:601-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spiro, S., and J. R. Guest. 1987. Regulation and over-expression of the fnr gene of Escherichia coli. J. Gen. Microbiol. 133:3279-3288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stewart, V. 2003. Nitrate- and nitrite-responsive sensors NarX and NarQ of proteobacteria. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 31:1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takehashi, K., T. Hattori, T. Nakanishi, T. Nohno, N. Fujita, A. Ishihama, and S. Taniguchi. 1994. Repression of in vitro transcription of the Escherichia coli fnr and narX genes by FNR protein. FEBS Lett. 340:59-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Towbin, H., T. Staehelin, and J. Gordon, J. 1979. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:4350-4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsui, H.-C. T., H.-C. E. Leung, and M. E. Winkler. 1994. Characterization of broadly pleiotropic phenotypes caused by an hfq insertion mutation in Escherichia coli K-12. Mol. Microbiol. 13:35-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Umeda, M., and E. Ohtsubo. 1990. Mapping of insertion element IS5 in the Escherichia coli K-12 chromosome: chromosomal rearrangements mediated by IS5. J. Mol. Biol. 213:229-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Unden, G., and A. Duchene. 1987. On the role of cyclic AMP and the Fnr protein in Escherichia coli growing anaerobically. Arch. Microbiol. 147:195-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Woods, S. A., and J. R. Guest. 1987. Differential roles of the Escherichia coli fumarases and fnr-dependent expression of fumarase B and aspartase. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 48:219-224. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yarmolinsky, M. 2000. Transcriptional silencing in bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 3:138-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang, A., K. M. Wasserman, J. Ortega, A. C. Steven, and G. Storz. 2002. The Sm-like Hfq protein increases OxyS RNA interaction with target mRNAs. Mol. Cell 9:11-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang, A., K. M. Wasserman, C. Rosenow, B. C. Tjaden, G. Storz, and S. Gottesman. 2003. Global analysis of small RNA and mRNA targets of Hfq. Mol. Microbiol. 50:1111-1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]