Graphical abstract

Keywords: Antibiotics, Antimicrobial resistance, Phytochemical-based TPP+ conjugates, Methicillin-resistant S. aureus, Bacterial membrane disruption

Abstract

Introduction

The infections by multidrug-resistant bacteria are a growing threat to human health, and the efficacy of the available antibiotics is gradually decreasing. As such, new antibiotic classes are urgently needed.

Objectives

This study aims to evaluate the antimicrobial activity, safety and mechanism of action of phytochemical-based triphenylphosphonium (TPP+) conjugates.

Methods

A library of phytochemical-based TPP+ conjugates was repositioned and extended, and its antimicrobial activity was evaluated against a panel of Gram-positive (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus – MRSA) and Gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Acinetobacter baumannii) and fungi (Candida albicans, Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii). The compounds’ cytotoxicity and haemolytic profile were also evaluated. To unravel the mechanism of action of the best compounds, the alterations in the surface charge, bacterial membrane integrity, and cytoplasmic leakage were assessed.

Results

Structure-activity-toxicity data revealed the contributions of the different structural components (phenolic ring, carbon-based spacers, carboxamide group, alkyl linker) to the compounds’ bioactivity and safety. Dihydrocinnamic derivatives 5 m and 5n stood out as safe, potent and selective antibacterial agents against S. aureus (MIC < 0.25 µg/mL; CC50 > 32 µg/mL; HC10 > 32 µg/mL). Mechanistic studies suggest that the antibacterial activity of compounds 5 m and 5n may result from interactions with the bacterial cell wall and membrane.

Conclusions

Collectively, these studies demonstrate the potential of phytochemical-based TPP+ conjugates as a new class of antibiotics.

Introduction

The discovery and development of antibiotics represents one of the greatest achievements in drug discovery history, being powerful allies in the combat of human infectious diseases [1], [2]. Unfortunately, the efficacy of many antibiotics is decreasing at a concerning rate. The misuse and overuse over the last century have been promoting selective pressure on bacteria, leading to the development of resistance to the available antibiotics and posing a serious threat to human health [3], [4]. Multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria are continuously emerging (e.g.: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE)), and they are difficult to treat as they usually evade the effect of the antibiotics used against them [5].

Infections with drug-resistant bacteria cause approximately 700 000 deaths per year [6], [7]. If sufficient attention is not given to this issue, it is estimated that by 2050, infections with MDR pathogenic bacteria will become the leading cause of death [6]. This scenario is further aggravated by the sluggish rate of discovery of new antibiotics, which fail to match the speed of the emergence and spread of MDR bacteria [5]. Moreover, antibiotics own a weak economic turnover, as a result of the scenario of antibiotic resistance coupled with the high costs of bringing a new drug to the market [2], [8]. This is one of the main reasons why big pharmaceutical companies have been discontinuing their antimicrobial projects throughout the new millennia [2], [8]. Collectively, these factors justify the urgent need of new classes of antibiotics, preferentially with the ability to operate through different mechanisms of action.

Quaternary heteronium salts, such as quaternary ammonium (QAC) and phosphonium compounds (QPCs), are considered a promising inspiration for the discovery of new antibiotics to tackle antibacterial resistance [9]. Quaternary ammonium salts have been used as antiseptics and disinfectants since the 1930′s [10] although the exact mechanism of action remains elusive. However, it is well recognized that they can disrupt the structure of the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane affecting its permeability [11], [12]. Quaternary phosphonium compounds (QPCs) were discovered in the middle of the 20th century, and their antimicrobial activity and safety in humans has been investigated since then.

The antimicrobial activity of quaternary heteronium salts depends on the density of the cationic charge and the hydrophobicity of the active molecule. Due to the stronger polarization effect of the phosphorus atom compared to the nitrogen atom, QPCs are more readily adsorbed onto the negatively charged bacterial membranes than QACs [13] and usually present higher activity, stability and wider pH applicable range (pH = 2–12) [13].

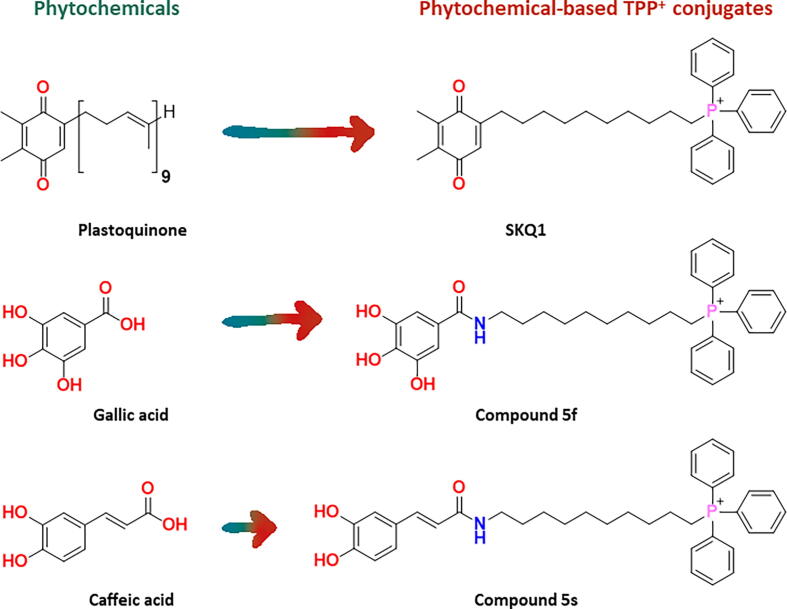

An important class of QPCs that has been lately developed is triphenylphosphonium (TPP+)-based mitochondria-targeted antioxidants (MTAs). They are composed of an antioxidant moiety, usually of natural origin, linked to the mitochondriotropic carrier TPP+ through an alkyl spacer [14]. Although TPP+-based MTAs have been widely investigated for their ability to reduce mitochondrial oxidative stress [15], it has been hypothesized that, due to the similar bioenergetic processes between mitochondria and bacteria, they may suppress bacterial growth by uncoupling oxidative phosphorylation [16]. However, the evaluation of the antimicrobial potential of TPP+-based MTAs remains poorly explored, with only a handful of studies being published over the last decades. For instance, SKQ1 (Fig. 1), a plastoquinone-based MTA, was proposed as an antimicrobial agent against Gram-positive (Bacillus subtilis, Mycobacterium sp. and S. aureus) and Gram-negative (Photobacterium phosphoreum and Rhodobacter sphaeroides) bacteria [16], [17]. Studies performed in B. subtilis indicate that the mechanism of action of SKQ1 may involve a decrease of the bacterial membrane potential [17].

Fig. 1.

Examples of phytochemicals and related phytochemical-based TPP+ conjugates.

The lack of data related with the antimicrobial activity, mechanism of action, and safety of TPP+ conjugates prompted us to conduct this study. Over the last decade, our research group has been developing phytochemical-based TPP+ conjugates using natural antioxidants (e.g.: phenolic acids) as inspiration. In general, these compounds exhibited safe cytotoxicity profiles in eukaryotic cell lines [18], [19], [20], [21].

Taken in account the growing need of new antibiotics, we decide to repurpose our in-house libraries of TPP+-based MTAs (Figs. 1 and 2) and evaluate their antimicrobial activity and safety (cytotoxicity and haemolytic activity) profiles. To establish robust structure–activity-toxicity relationships, we extended our library by synthesizing new TPP+ conjugates (Fig. 2). Finally, we selected the most potent compounds to unravel the mechanism of action behind their antimicrobial activity.

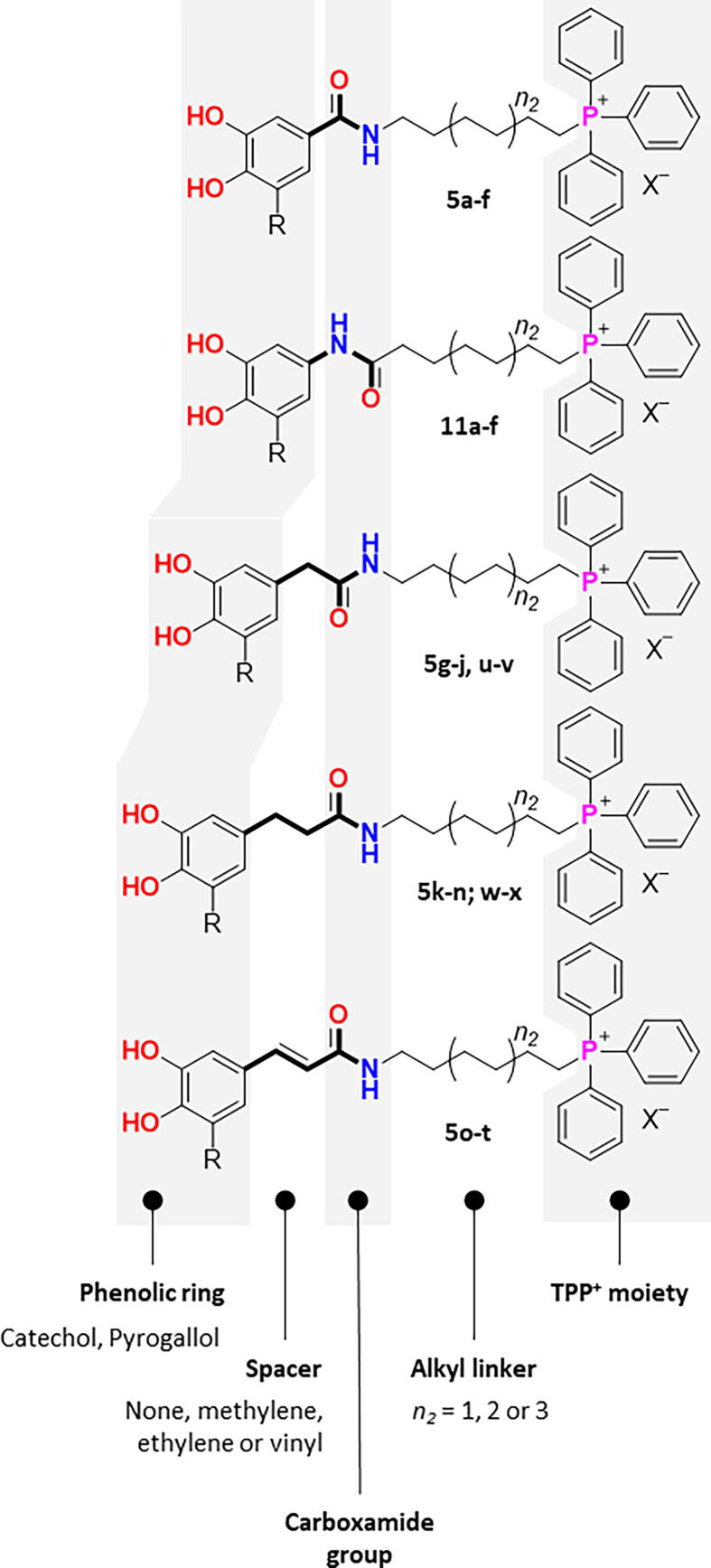

Fig. 2.

Rational design strategy followed for the development of phytochemical-based TPP+ conjugates.

Materials and methods

Chemistry

Reagents and general conditions

All reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and TCI Chemicals. All solvents were pro analysis grade from Merck, Carlo Erba Reagents and Scharlab.

Thin layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on precoated silica gel 60 F254 acquired from Merck with layer thickness of 0.2 mm. Reaction control was monitored using ethyl acetate and/or ethyl acetate:methanol (9:1) and spots were visualized under UV detection at 254 and 366 nm. Following the extraction step, the organic layers were dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate. Flash column chromatography was carried out with silica gel 60 0.040–0.063 mm acquired from Carlo-Erba Reactifs. Cellulose flash column chromatography was carried out with cellulose powder 0.01–0.10 mm acquired from Sigma-Aldrich. The elution systems used for flash column chromatography were specified for each compound. The fractions containing the desired product were collected and concentrated under reduced pressure. Solvents were evaporated using a Büchi Rotavapor.

Apparatus

NMR. NMR data were acquired on a Bruker Avance III 400 NMR spectrometer, at room temperature, operating at 400.15 MHz for 1H and 100.62 MHz for 13C and DEPT135 (Distortionless Enhancement by Polarization Transfer). Tetramethylsilane (TMS) was used as internal reference; chemical shifts (δ) were expressed in ppm and coupling constants (J) were given in Hz. DEPT135 values were included in 13C NMR data (underline values).

HPLC. Chromatograms were acquired on a Shimadzu high-performance liquid chromatograph (HPLC) SPD-M20A system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) with a Luna C18 (2) column (Phenomenex, CA, USA) 150x4.6 mm, 5 µm. The mobile phase was acetonitrile/water (gradient mode, room temperature) at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The chromatographic data was analysed by the LabSolutions software version 5.93 (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The purity of the final products (>98%) was verified by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) equipped with a DAD detector (See SI).

Synthesis

General procedure for the synthesis of amides 2a-t, 4u-x and 10a-f

To obtain amides 2a-t, 4u-x and 10a-f, two different synthetic strategies were used. Compounds 2a-b, 2o-t, 4u-x and 10a-f were synthesized following the procedure A1, while compounds 2c-n were obtained following the procedure A2.

Procedure A1. The appropriate carboxylic acid (compounds 1a-b, 1 g-h or 9a-c, Scheme 1, Scheme 2, Scheme 3, Scheme 1 mmol) was dissolved in dichloromethane (40 mL), and triethylamine (2 mmol) was added. Then, ethyl chloroformate (2 mmol) was added dropwise to the reaction mixture kept in an ice bath. After stirring for 2 h at room temperature, the appropriate amine (1-amino-6-hexanol, 1-amino-8-octanol, 1-amino-8-octanol, compound 8 or compounds 1i-j; 2 mmol) was added. The reaction was stirred for 10 h at room temperature. The reaction conditions and work-up were previously described [18], [19], [21].

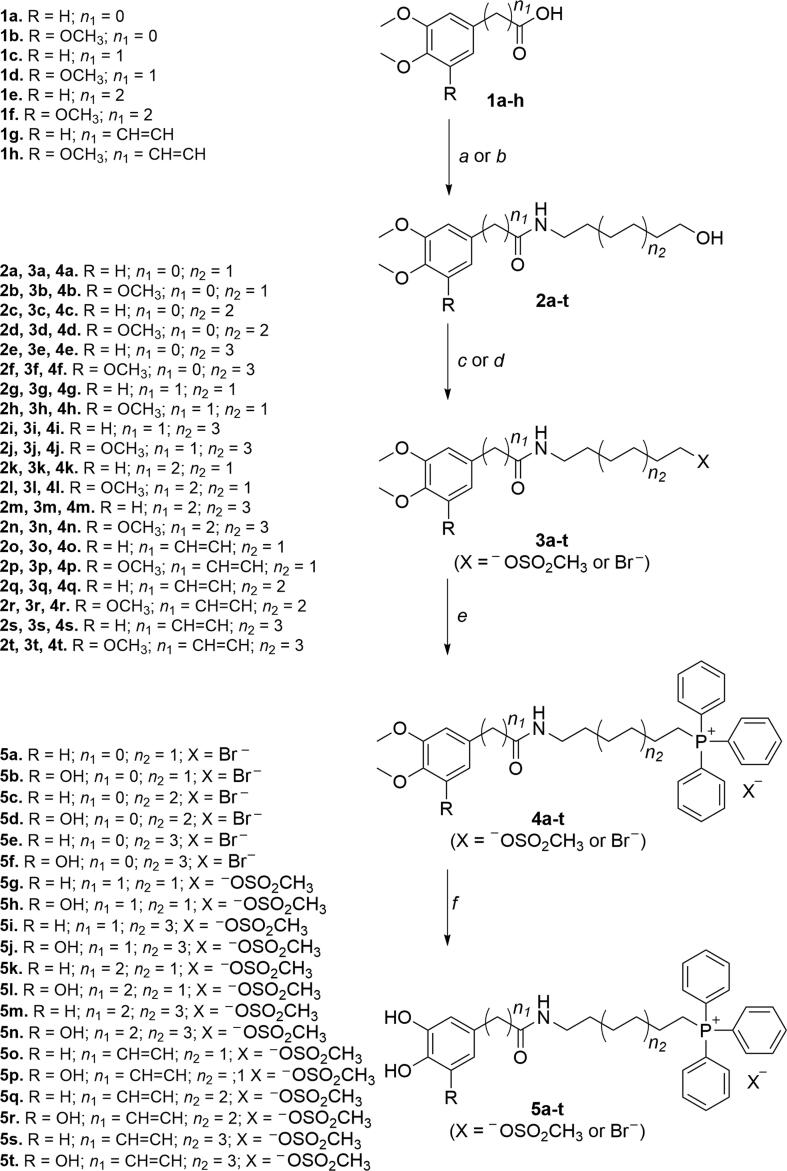

Scheme 1.

Synthetic strategy followed to obtain phytochemical-based TPP+ conjugates 5a-t. Reagents and conditions: (a) appropriate hydroxyalkylamines (1-amino-6-hexanol, 1-amino-8-octanol or 1-amino-10-decanol), (C2H5)3N, ClCOOC2H5, DCM, r.t., 10 h; (b) POCl3, DIPEA, DCM, r.t., 1–2 h; (c) C2Br2Cl4, diphos, THF, r.t., 20 h; (d) (C2H5)3N, CH3SO2Cl, THF, r.t., 12 h; (e) TPP, 100–130 °C, 48 h; (f) BBr3, anhydrous DCM, –70 °C to r.t., 12 h.

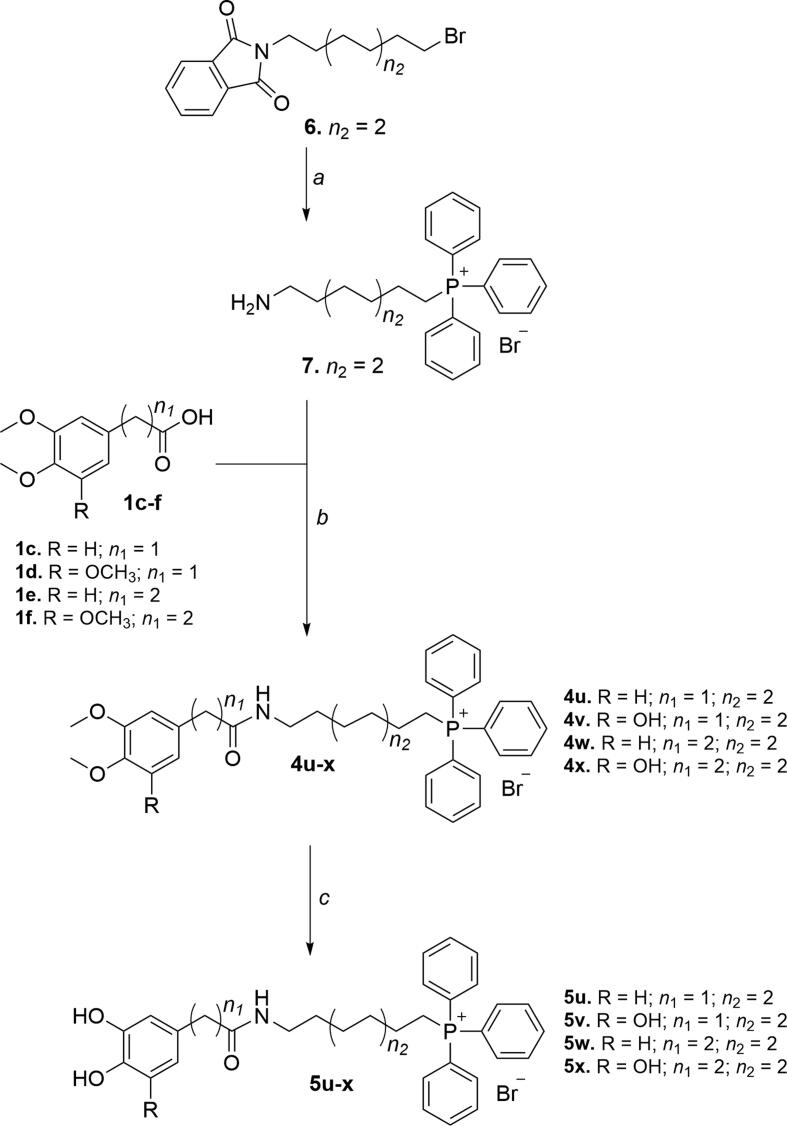

Scheme 2.

Synthetic strategy followed to obtain phytochemical-based TPP+ conjugates 5u-x. Reagents and conditions: (a) 1) TPP, 130 °C, 2 h, 2) CH3(CH2)3NH2, CH3CH2OH, reflux, 2 h; (b) (C2H5)3N, ClCOOC2H5, DCM, r.t., 10 h; (c) BBr3, anhydrous DCM, –70 °C to r.t., 12 h.

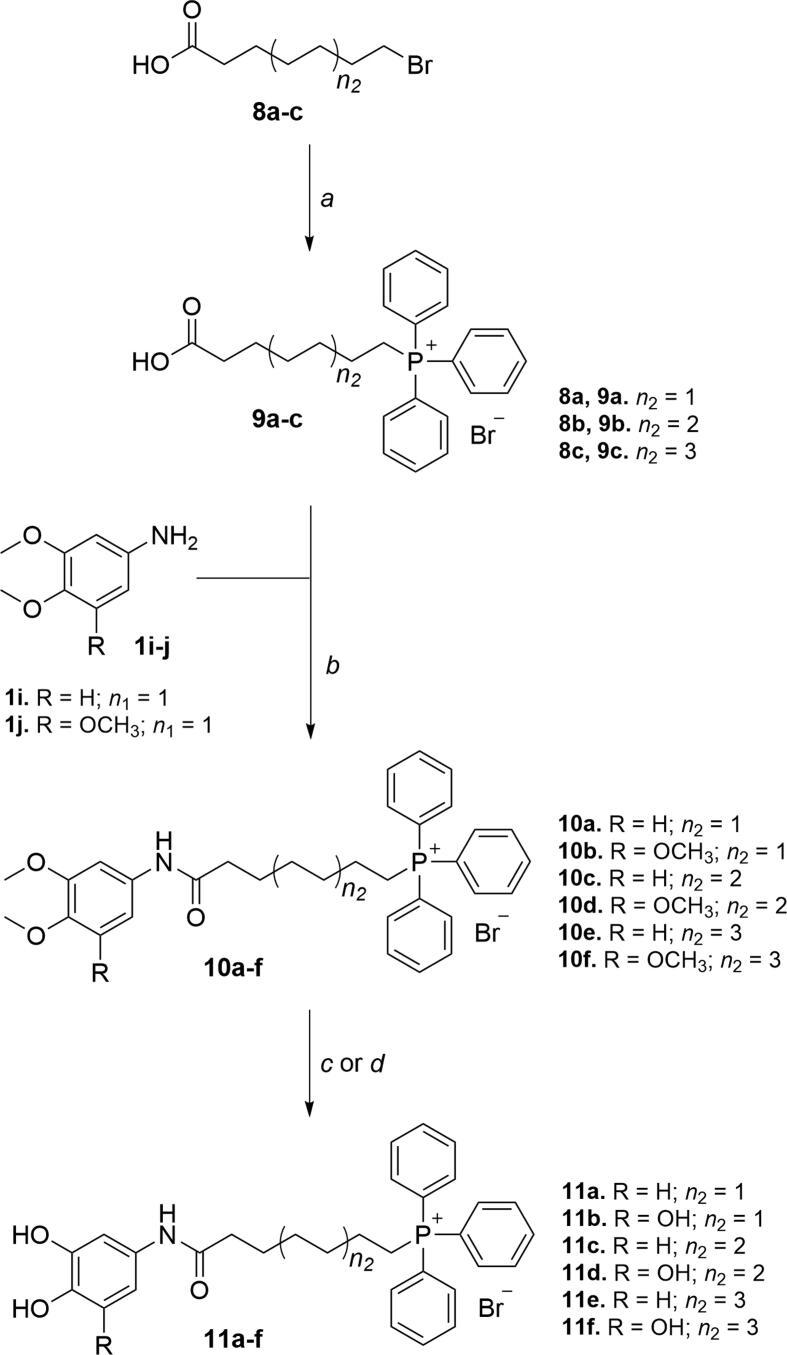

Scheme 3.

Synthetic strategy followed to obtain phytochemical-based TPP+ conjugates 11a-f. Reagents and conditions: (a) TPP, 100 °C, 48 h; (b) (C2H5)3N, ClCOOC2H5, DCM, r.t., 10 h; (c) BBr3, anhydrous DCM, –78 °C to r.t., 12 h.; (d) BBr3∙S(CH3)2, anhydrous DCM, reflux, 2–3 h.

Procedure A2. To a solution of the appropriate carboxylic acid (compounds 1a-f, Scheme 1, Scheme 1 mmol) in dichloromethane (20 mL), phosphorus oxychloride (1 mmol) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 30 min, then cooled on an ice bath, and the appropriate aminoalkylalcohol (1-amino-6-hexanol, 1-amino-8-octanol or 1-amino-8-octanol; 1.2 mmol) and DIPEA (4 mmol) were added. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 h. The mixture was then extracted, and the combined organic layers were dried over Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated. The reaction conditions and work-up were previously described in literature [20], [21].

The spectroscopic data of compounds 2a-t were previously described in literature [18], [19], [20], [21].

(8-(2-(3,4-Dimethoxyphenyl)acetamido)octyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide (4u).Procedure A2. η = 65 %. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ = 1.02 – 1.30 (6H, m, (CH2)3(CH2)3P+), 1.30 – 1.45 (2H, m, CH2(CH2)2P+), 1.44 – 1.61 (4H, m, CH2CH2P+, CH2(CH2)6P+), 3.08 (2H, q, J = 6.9 Hz, CH2(CH2)7P+), 3.49 (2H, s, CH2CONH), 3.51 – 3.61 (2H, m, CH2CH2P+), 3.74 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.76 (3H, s, OCH3), 6.69 (1H, d, J = 8.2 Hz, H(5)), 6.82 (1H, dd, J = 8.2, 2.0 Hz, H(6)), 6.90 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz, H(2)), 7.59 – 7.78 (15H, m, PPh3) 13C NMR (CDCl3): 22.4 (d, JCP = 4.7 Hz, CH2(CH2)2P+), 22.7 (d, JCP = 50.3 Hz, CH2P+), 26.3 (CH2(CH2)5P+), 28.3 (CH2(CH2)4P+, CH2(CH2)3P+), 28.9 (CH2(CH2)6P+), 29.9 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, CH2CH2P+), 39.4 (CH2(CH2)7P+), 43.1 (CH2CONH), 56.0 (OCH3), 56.0 (OCH3), 111.4 (C(2)), 112.9 (C(5)), 118.3 (d, JCP = 85.9 Hz, 3 × C(1′)), 121.7 (C(6)), 128.8 (C(1′)), 130.6 (d, JCP = 12.6 Hz, 3 × C(3′) and 3 × C(5′)), 133.6 (d, JCP = 9.9 Hz, 3 × C(2′) and 3 × C(6′)), 135.2 (d, JCP = 3.0 Hz, 3 × C(4′)), 147.8 (C(4)), 148.9 (C(3)), 171.8 (CO).

(8-(2-(3,4,5-Trimethoxyphenyl)acetamido)octyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide (4v). Procedure A2. η = 69 %. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ = 1.17 – 1.38 (6H, m, (CH2)3(CH2)3P+), 1.45 – 1.55 (2H, m, CH2(CH2)2P+), 1.55 – 1.68 (4H, m, CH2CH2P+, CH2(CH2)6P+), 3.20 (2H, q, J = 6.5 Hz, CH2(CH2)7P+), 3.55 – 3.67 (2H, m, CH2CH2P+), 3.60 (2H, s, CH2CONH), 3.77 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.81 (6H, s, 2 × OCH3), 6.70 (2H, s, C(2), C(6)), 7.66 – 7.86 (15H, m, PPh3). 13C NMR (CDCl3): 22.2 (d, JCP = 4.6 Hz, CH2(CH2)2P+), 22.4 (d, JCP = 50.4 Hz, CH2P+), 26.1 (CH2(CH2)5P+), 28.1 (CH2(CH2)4P+), 28.2 (CH2(CH2)3P+), 28.9 (CH2(CH2)6P+), 29.7 (d, JCP = 15.9 Hz, CH2CH2P+), 39.2 (CH2(CH2)7P+), 43.6 (CH2CONH), 56.1 (2 × OCH3), 60.6 (OCH3), 106.5 (C(2) and C(6)), 118.6 (d, JCP = 86.3 Hz, 3 × C(1′)), 130.5 (d, JCP = 12.4 Hz, 3 × C(3′) and 3 × C(5′)), 132.2 (C(1)), 133.4 (d, JCP = 10.0 Hz, 3 × C(2′) and 3 × C(6′)), 135.1 (d, JCP = 3.0 Hz, 3 × C(4′)), 136.2 (C(4)), 152.8 (C(3) and C(5)), 171.4 (CO).

(8-(3-(3,4-Dimethoxyphenyl)propanamido)octyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide (4w). Procedure A2. η = 62 %. 1H NMR (MeOD): δ = 1.08 – 1.39 (8H, m, (CH2)4(CH2)2P+), 1.44 – 1.58 (2H, m, CH2CH2P+), 1.08 – 1.39 (2H, m, CH2(CH2)6P+), 2.45 (2H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, CH2CH2CONH), 2.84 (2H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, CH2CH2CONH), 3.34 – 3.46 (2H, m, CH2P+), 3.72 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.76 (2H, s, OCH3), 6.73 (1H, dd, J = 8.2, 2.0 Hz, H(6)), 6.80 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz, H(2)), 6.82 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, H(5)), 7.71 – 7.93 (15H, m, PPh3). 13C NMR (MeOD): 21.3 (d, JCP = 51.0 Hz, CH2P+), 22.1 (d, JCP = 4.3 Hz, CH2(CH2)2P+), 26.2 (CH2(CH2)5P+), 28.3 (CH2(CH2)4P+), 28.6 (CH2(CH2)3P+), 28.8 (CH2(CH2)6P+), 30.1 (d, JCP = 16.1 Hz, CH2CH2P+), 31.1 (CH2CH2CONH), 37.6 (CH2CH2CONH), 38.9 (CH2(CH2)7P+), 55.0 (OCH3), 55.1 (OCH3), 111.8 (C(5)), 112.2 (C(2)), 118.6 (d, JCP = 86.2 Hz, 3 × C(1′)), 120.4, 130.1 (d, JCP = 12.6 Hz, 3 × C(3′) and 3 × C(5′)), 133.4 (d, JCP = 10.0 Hz, 3 × C(2′) and 3 × C(6′)), 134.9 (d, JCP = 3.2 Hz, 3 × C(4′)), 147.6 (C(4)), 149.0 (C(3)), 173.8 (CO).

(8-(3-(3,4,5-Trimethoxyphenyl)propanamido)octyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide (4x). Procedure A2. η = 65 %. 1H NMR (MeOD): δ = 1.11 – 1.41 (6H, m, (CH2)3(CH2)3P+), 1.46 – 1.56 (2H, m, CH2(CH2)2P+), 1.59 – 1.73 (4H, m, CH2CH2P+, CH2(CH2)6P+), 2.48 (2H, t, J = 7.3 Hz, CH2CH2CONH), 2.85 (2H, t, J = 7.3 Hz, CH2CH2CONH), 3.09 (2H, t, J = 6.9 Hz, CH2(CH2)7P+), 3.32 – 3.45 (2H, m, CH2P+), 3.64 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.79 (6H, s, 2 × OCH3), 6.51 (2H, s, C(2), C(6)), 7.68 – 7.94 (15H, m, PPh3). 13C NMR (MeOD): 21.3 (d, JCP = 50.9 Hz, CH2P+), 22.1 (d, JCP = 4.5 Hz, CH2(CH2)2P+), 26.2 (CH2(CH2)5P+), 28.3 (CH2(CH2)4P+), 28.6 (CH2(CH2)3P+), 28.9 (CH2(CH2)6P+), 30.1 (d, JCP = 16.1 Hz, CH2CH2P+), 31.8 (CH2CH2CONH), 37.4 (CH2CH2CONH), 38.9 (CH2(CH2)7P+), 55.2 (2 × OCH3), 59.7 (OCH3), 105.4 (C(2) and C(6)), 118.6 (d, JCP = 86.3 Hz, 3 × C(1′)), 130.1 (d, JCP = 12.6 Hz, 3 × C(3′) and 3 × C(5′)), 133.4 (d, JCP = 10.2 Hz, 3 × C(2′) and 3 × C(6′)), 134.9 (d, JCP = 3.0 Hz, 3 × C(4′)), 136.1 (C(1)), 136.8 (C(4)), 153.0 (C(3) and C(5)), 173.7 (CO).

(7-((3,4-Dimethoxyphenyl)amino)-7-oxoheptyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide (10a). Procedure A1. η = 83 %. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ = 1.42 – 1.52 (2H, m, CH2(CH2)2P+), 1.54 – 1.65 (2H, m, CH2CH2P+), 1.67 – 1.76 (2H, m, CH2(CH2)3P+), 1.80 – 1.85 (2H, m, CH2(CH2)4P+), 2.63 (2H, t, J = 6.9 Hz, CH2(CH2)5P+), 3.62 – 3.73 (2H, m, CH2P+), 3.82 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.84 (3H, s, OCH3), 6.71 (1H, d, J = 8.7 Hz, H(5)), 7.51 (1H, dd, J = 2.4, 8.7 Hz, H(6)), 7.58 – 7.78 (15H, m, PPh3), 7.81 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz, H(2)), 10.40 (1H, s, NH). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ = 22.0 (d, JCP = 4.3 Hz, CH2(CH2)2P+), 22.2 (d, JCP = 50.1 Hz, CH2P+), 24.7 (CH2(CH2)4P+), 26.5 (CH2(CH2)3P+), 28.3 (d, JCP = 16.6 Hz, CH2CH2P+), 36.1 (CH2(CH2)5P+), 56.1 (OCH3), 56.3 (OCH3), 104.9 (C(2)), 111.3 (C(6)), 111.8 (C(5)), 118.4 (d, JCP = 85.8 Hz, 3 × C(1′)), 130.6 (d, JCP = 12.5 Hz, 3 × C(3′) and 3 × C(5′)), 133.8 (d, JCP = 9.9 Hz, 3 × C(2′) and 3 × C(6′)), 134.0 (C(1)), 135.1 (d, JCP = 2.9 Hz, 3 × C(4′)), 144.8 (C(4)), 148.7 (C(3)), 172.9 (CO).

(7-((3,4,5-Trimethoxyphenyl)amino)7-oxoheptyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide (10b). Procedure A1. η = 72 %. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ = 1.40 – 1.50 (2H, m, CH2(CH2)2P+), 1.54 – 1.65 (2H, m, CH2CH2P+), 1.67 – 1.76 (2H, m, CH2(CH2)3P+), 1.76 – 1.84 (2H, m, CH2(CH2)4P+), 2.62 (2H, t, J = 6.8 Hz, CH2(CH2)5P+), 3.57 – 3.69 (2H, m, CH2P+), 3.78 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.79 (6H, s, 2 × OCH3), 7.46 (2H, H(2) and H(6)), 7.58 – 7.82 (15H, m, PPh3), 10.55 (1H, s, NH). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ = 22.0 (d, JCP = 4.3 Hz, CH2(CH2)2P+), 22.2 (d, JCP = 50.1 Hz, CH2P+), 24.7 (CH2(CH2)4P+), 26.5 (CH2(CH2)3P+), 28.4 (d, JCP = 16.7 Hz, CH2CH2P+), 36.1 (CH2(CH2)5P+), 56.2 (2 × OCH3), 61.0 (OCH3), 97.6 (C(2) and C(6)), 118.4 (d, JCP = 85.9 Hz, 3 × C(1′)), 130.6 (d, JCP = 12.5 Hz, 3 × C(3′) and 3 × C(5′)), 133.6 (d, JCP = 10.0 Hz, 3 × C(2′) and 3 × C(6′)), 133.6 (C(4)), 135.2 (d, JCP = 3.0 Hz, 3 × C(4′)), 136.4 (C(1)), 152.9 (C(3) and C(5)), 173.2 (CO).

(9-((3,4-Dimethoxyphenyl)amino)-9-oxononyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide (10c). Procedure A1. η = 80 %. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ = 1.23 – 1.41 (6H, m, (CH2)3(CH2)2P+), 1.54 – 1.75 (6H, m, (CH2)2(CH2)3CH2CH2P+), 2.50 (2H, t, J = 7.6 Hz, CH2(CH2)7P+), 3.51 – 3.64 (2H, m, CH2P+), 3.79 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.82 (3H, s, OCH3), 6.68 (1H, d, J = 8.7 Hz, H(5)), 7.40 (1H, dd, J = 2.4, 8.7 Hz, H(6)), 7.61 – 7.85 (16H, m, PPh3 and H(2)), 9.71 (1H, s, NH). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ = 22.3 (d, JCP = 4.5 Hz, CH2(CH2)2P+), 22.6 (d, JCP = 50.1 Hz, CH2P+), 25.3 (CH2(CH2)6P+), 27.7 ((CH2(CH2)5P+), 28.0 ((CH2)2(CH2)3P+), 29.8 (d, JCP = 15.6 Hz, CH2CH2P+), 37.4 (CH2(CH2)7P+), 56.0 (OCH3), 56.2 (OCH3), 105.0 (C(2)), 111.2 (C(6)), 111.8 (C(5)), 118.3 (d, JCP = 85.9 Hz, 3 × C(1′)), 130.6 (d, JCP = 12.5 Hz, 3 × C(3′) and 3 × C(5′)), 133.6 (d, JCP = 9.9 Hz, 3 × C(2′) and 3 × C(6′)), 133.6 (C(1)), 135.1 (d, JCP = 3.0 Hz, 3 × C(4′)), 144.7 (C(4)), 148.6 (C(3)), 172.7 (CO).

(9-((3,4,5-Trimethoxyphenyl)amino)-9-oxononyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide (10d). Procedure A1. η = 69 %. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ = 1.27 – 1.41 (6H, m, (CH2)3(CH2)2P+), 1.56 – 1.76 (6H, m, (CH2)2(CH2)3CH2CH2P+), 2.53 (2H, t, J = 7.6 Hz, CH2(CH2)7P+), 3.50 – 3.62 (2H, m, CH2P+), 3.77 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.79 (6H, s, 2 × OCH3), 7.39 (2H, H(2) and H(6)), 7.65 – 7.83 (15H, m, PPh3), 9.90 (1H, s, NH). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ = 22.3 (d, JCP = 4.3 Hz, CH2(CH2)2P+), 22.6 (d, JCP = 50.0 Hz, CH2P+), 25.2 (CH2(CH2)6P+), 27.6 ((CH2(CH2)5P+), 27.9 ((CH2)2(CH2)3P+), 29.7 (d, JCP = 15.4 Hz, CH2CH2P+), 37.5 (CH2(CH2)7P+), 56.1 (2 × OCH3), 60.9 (OCH3), 97.6 (C(2) and C(6)), 118.3 (d, JCP = 85.9 Hz, 3 × C(1′)), 130.6 (d, JCP = 12.5 Hz, 3 × C(3′) and 3 × C(5′)), 133.6 (d, JCP = 9.9 Hz, 3 × C(2′) and 3 × C(6′)), 135.2 (d, JCP = 3.0 Hz, 3 × C(4′)), 133.6 (C(4)), 136.1 (C(1)), 152.8 (C(3) and C(5)), 173.2 (CO).

(11-((3,4-Dimethoxyphenyl)amino)-11-oxoundecyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide (10e). Procedure A1. η = 85 %. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ = 1.05 – 1.27 (10H, m, (CH2)5(CH2)2P+), 1.41 – 1.63 (6H, m, (CH2)2(CH2)5CH2CH2P+), 2.43 (2H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, CH2(CH2)9P+), 3.36 – 3.47 (2H, m, CH2P+), 3.69 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.71 (3H, s, OCH3), 6.56 (1H, d, J = 8.7 Hz, H(5)), 7.27 (1H, dd, J = 2.6, 8.9 Hz, H(6)), 7.58 – 7.78 (15H, m, PPh3 and H(2)), 10.01 (1H, s, NH). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ = 22.4 (d, JCP = 4.4 Hz, CH2(CH2)2P+), 22.5 (d, JCP = 50.3 Hz, CH2P+), 25.6 (CH2(CH2)8P+), 28.5 (CH2(CH2)7P+), 28.7 (CH2(CH2)6P+), 28.8 (CH2CH2CH2(CH2)3P+), 28.9 (CH2(CH2)4P+), 30.2 (d, JCP = 15.5 Hz, CH2CH2P+), 37.0 (CH2(CH2)9P+), 55.8 (OCH3), 56.1 (OCH3), 105.0 (C(2)), 111.2 (C(6)), 111.9 (C(5)), 118.1 (d, JCP = 85.9 Hz, 3 × C(1′)), 130.6 (d, JCP = 12.5 Hz, 3 × C(3′) and 3 × C(5′)), 133.4 (d, JCP = 9.9 Hz, 3 × C(2′) and 3 × C(6′)), 133.7 (C(1)), 135.2 (d, JCP = 2.9 Hz, 3 × C(4′)), 144.6 (C(4)), 148.5 (C(3)), 172.7 (CO).

(11-((3,4,5-Trimethoxyphenyl)amino)11-oxoundecyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide (10f). Procedure A1. η = 65 %. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ = 1.15 – 1.38 (10H, m, (CH2)5(CH2)2P+), 1.47 – 1.77 (6H, m, (CH2)2(CH2)5CH2CH2P+), 2.53 (2H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, CH2(CH2)9P+), 3.49 – 3.60 (2H, m, CH2P+), 3.75 (9H, s, OCH3), 7.29 (2H, H(2) and H(6)), 7.63 – 7.82 (15H, m, PPh3), 10.00 (1H, s, NH). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ = 22.6 (d, JCP = 4.6 Hz, CH2(CH2)2P+), 22.6 (d, JCP = 50.0 Hz, CH2P+), 25.4 (CH2(CH2)8P+), 28.4 (CH2(CH2)7P+), 28.5 (CH2(CH2)6P+), 28.7 (CH2CH2CH2(CH2)3P+), 28.8 (CH2(CH2)4P+), 30.2 (d, JCP = 15.6 Hz, CH2CH2P+), 37.2 (CH2(CH2)9P+), 56.2 (2 × OCH3), 61.0 (OCH3), 97.8 (C(2) and C(6)), 118.4 (d, JCP = 85.9 Hz, 3 × C(1′)), 130.7 (d, JCP = 12.5 Hz, 3 × C(3′) and 3 × C(5′)), 133.6 (d, JCP = 10.0 Hz, 3 × C(2′) and 3 × C(6′)), 133.6 (C(4)), 135.3 (d, JCP = 3.0 Hz, 3 × C(4′)), 136.2 (C(1)), 152.9 (C(3) and C(5)), 173.2 (CO).

General procedure for the synthesis of bromo (3a-f) and methanesulfonate derivatives (3 g-n)

Bromo (3a-f) and methanesulfonate derivatives (3 g-n) were obtained following the procedures B1 and B2, respectively.

Procedure B1. Compounds 2a-f (1 mmol) and 1,2-dibromotetrachloroethane (1 mmol) were dissolved in tetrahydrofuran (20 mL). Then, 1,2-bis(diphenylphosphine)ethane (diphos, 0.5 mmol) was added, and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 20 h. Upon completion, the reaction mixture was filtered though Celite and concentrated under reduced pressure. The oil residue obtained was purified by flash column chromatography (silica gel). The reaction conditions and work-up were previously described in literature [19], [20].

Procedure B2. Compounds 2 g-n (1 mmol) were dissolved in dichloromethane (10 mL) and triethylamine (1.5 mmol). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 10 min. Then, a solution of methanesulfonyl chloride (1.5 mmol) in tetrahydrofuran (5 mL) was added dropwise over 20 min, and the reaction mixture stirred at room temperature for 12 h. Upon completion, the mixture was extracted, and the combined organic layers were dried over Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated. The reaction conditions and work-up were previously described in literature [21].

The spectroscopic data of compounds 3a-n were previously described in literature [19], [20], [21].

General procedure for the synthesis of triphenylphosphonium salts (4a-t, 7 and 9a-c).

Triphenylphosphonium salts 4a-t, 7 and 9a-c were obtained by two different synthetic strategies: procedure C1 (compounds 4a-t and 9a-c) and procedure C2 (compound 7).

Procedure C1. Bromo or methanesulfonate derivatives (3a-t or 8a-c, 1 mmol) were heated with triphenylphosphine (TPP, 1 mmol) at 100–130 °C for 48 h under argon atmosphere. The resulting products were purified by flash column chromatography. The reaction conditions and work-up were previously described in literature [18], [19], [20], [21].

Procedure C2. A mixture containing the appropriate N-(bromoalkyl)phthalimide (1 mmol) and triphenylphosphine (1.2 mmol) was thoroughly mixed under argon atmosphere and heated at 130 °C for 2 h, protected from the light. Then, ethanol and butylamine (10 mmol) were added, and the mixture was refluxed for 2 h. Upon completion, the solvent was partially concentrated, and water was added. The solid obtained was filtered off under reduced pressure and the filtrate was extracted with dichloromethane. The aqueous phase was concentrated. The crude product was used without further purification in the next step.

The spectroscopic data of compounds 4a-t were previously described [18], [19], [20], [21].

(8-Aminooctyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide (7). Procedure C2. η = 87 %. 1H NMR (MeOD): δ = 1.23 – 1.44 (6H, m, (CH2)3(CH2)2P+), 1.47 – 1.61 (4H, m, (CH2)2CH2P+), 1.62 – 1.73 (2H, m, CH2(CH2)6P+), 2.74 (2H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, CH2(CH2)7P+), 3.37 – 3.46 (2H, m, CH2P+), 7.73 – 7.94 (15H, m, PPh3). 13C NMR (MeOD): δ = 22.7 (d, JCP = 51.0 Hz, CH2P+,), 23.5 (d, JCP = 4.4 Hz, CH2(CH2)2P+), 27.5 (CH2(CH2)5P+), 29.7 (CH2(CH2)3P+), 30.0 (CH2(CH2)4P+), 31.2 (CH2(CH2)6P+), 31.5 (d, JCP = 16.2 Hz, CH2CH2P+), 41.6 (CH2(CH2)7P+), 120.0 (d, JCP = 86.4 Hz, 3 × C(1′)), 131.5 (d, JCP = 12.5 Hz, 3 × C(3′) and 3 × C(5′)), 134.8 (d, JCP = 10.1 Hz, 3 × C(2′) and 3 × C(6′)), 136.3 (d, JCP = 3.1 Hz, 3 × C(4′)).

(6-Carboxyhexyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide (9a). Procedure C1. η = 92 %. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ = 1.23 – 1.32 (2H, m, CH2(CH2)2P+), 1.40 – 1.49 (2H, m, CH2CH2P+), 1.52 – 1.62 (4H, m, (CH2)2(CH2)3P+), 2.27 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2(CH2)5P+), 3.45 – 3.55 (2H, m, CH2P+), 7.62 – 7.79 (15H, m, PPh3). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ = 22.1 (d, JCP = 4.5 Hz, CH2(CH2)2P+), 22.4 (d, JCP = 50.4 Hz, CH2P+), 24.2 (CH2(CH2)4P+), 27.9 (CH2(CH2)3P+), 29.5 (d, JCP = 16.1 Hz, CH2CH2P+), 34.3 (CH2(CH2)5P+), 118.1 (d, JCP = 85.9 Hz, 3 × C(1′)), 130.6 (d, JCP = 12.5 Hz, 3 × C(3′) and 3 × C(5′)), 133.6 (d, JCP = 10.0 Hz, 3 × C(2′) and 3 × C(6′)), 135.2 (d, JCP = 2.9 Hz, 3 × C(4′)), 176.3 (CO).

(8-Carboxyoctyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide (9b). Procedure C1. η = 98 %. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ = 1.18 – 1.34 (6H, m, (CH2)3(CH2)2P+), 1.51 – 1.66 (6H, m, (CH2)2(CH2)3CH2CH2P+), 2.35 (2H, t, J = 7.3 Hz, CH2(CH2)7P+), 3.60 – 3.72 (2H, m, CH2P+), 7.67 – 7.86 (15H, m, PPh3). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ = 22.6 (d, JCP = 4.8 Hz, CH2(CH2)2P+), 22.8 (d, JCP = 49.6 Hz, CH2P+), 24.6 (CH2(CH2)6P+), 28.3 ((CH2(CH2)5P+), 28.4 ((CH2)2(CH2)3P+), 30.1 (d, JCP = 15.8 Hz, CH2CH2P+), 34.6 (CH2(CH2)7P+), 118.5 (d, JCP = 85.8 Hz, 3 × C(1′)), 130.7 (d, JCP = 12.6 Hz, 3 × C(3′) and 3 × C(5′)), 133.8 (d, JCP = 9.9 Hz, 3 × C(2′) and 3 × C(6′)), 135.2 (d, JCP = 3.1 Hz, 3 × C(4′)), 176.8 (CO).

(10-Carboxydecyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide (9c). Procedure C1. η = 98 %. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ = 1.12 – 1.30 (10H, m, (CH2)5(CH2)2P+), 1.50 – 1.65 (6H, m, (CH2)2(CH2)5CH2CH2P+), 2.34 (2H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, CH2(CH2)9P+), 3.58 – 3.68 (2H, m, CH2P+), 7.65 – 7.85 (15H, m, PPh3). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ = 22.7 (d, JCP = 4.6 Hz, CH2(CH2)2P+), 22.8 (d, JCP = 50.1 Hz, CH2P+), 24.8 (CH2(CH2)8P+), 28.8 ((CH2)2(CH2)2CH2(CH2)3P+), 28.9 (CH2(CH2)5P+), 29.0 (CH2(CH2)4P+), 30.4 (d, JCP = 15.6 Hz, CH2CH2P+), 34.4 (CH2(CH2)9P+), 118.4 (d, JCP = 85.8 Hz, 3 × C(1′)), 130.7 (d, JCP = 12.5 Hz, 3 × C(3′) and 3 × C(5′)), 133.7 (d, JCP = 10.0 Hz, 3 × C(2′) and 3 × C(6′)), 135.2 (d, JCP = 2.9 Hz, 3 × C(4′)), 177.3 (CO).

General procedure to obtain lipophilic TPP+ conjugates 5a-x and 11a-f

The TPP+ conjugates 5a-x and 11a-f were synthesized following two different procedures: method D1 for compounds 5a-x, 11b, 11d and 11f and method D2 for compounds 11a, 11c and 11e.

Procedure D1. A solution of compounds 4a-x, 10b, 10d or 10f (1 mmol) in anhydrous dichloromethane (15 mL) was stirred under argon atmosphere and cooled at a temperature below –70 °C. Then, boron tribromide 1 M (5–7 mmol) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred at –70 °C for 10 min and then allowed to reach room temperature for additional 12 h. Upon completion, the reaction mixture was cautiously quenched with water (40 mL). After removing the water, the product was dissolved in methanol, dried over anhydrous sodium sulphate, filtered and concentrated. The residue was purified by flash column chromatography (silica gel, dichloromethane:methanol (9:1) to (8:2)). The reaction conditions and work-up were previously described in literature [18], [19], [20], [21].

Procedure D2. To a solution of compounds 10a, 10c or 10e (1 mmol) in dichloromethane (10 mL), boron tribromide dimethyl sulphide complex (6.0 mmol) was added. The reaction mixture was refluxed for 2–3 h. Upon completion, the reaction mixture was cautiously quenched with water (40 mL). After removing the water, the product was dissolved in methanol, dried over anhydrous sodium sulphate, filtered and concentrated. The residue was purified by flash column chromatography (silica gel, dichloromethane:methanol (9:1) to (8:2)). The reaction was followed by TLC (silica gel, mobile phase with dichloromethane:methanol (9:1)). The reaction conditions and work-up were previously described in literature [18], [19], [20], [21].

The spectroscopic data of compounds 5a-t were previously described in literature [18], [19], [20], [21].

(8-(2-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)acetamido)octyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide (5u). Procedure D1. η = 50 %. 1H NMR (MeOD): δ = 1.17 – 1.33 (6H, m, (CH2)3CH2CH2CH2P+), 1.38 – 1.55 (4H, m, CH2CH2CH2P+), 1.59 – 1.69 (2H, m, CH2(CH2)6P+), 3.12 (2H, t, J = 7.0 Hz, CH2(CH2)7P+), 3.28 – 3.42 (4H, m, (CH2P+ and CH2CONH), 6.58 (1H, dd, J = 8.1, 2.1 Hz, H(6)), 6.68 (1H, d, J = 8.1 Hz, H(5)), 6.72 (1H, d, J = 2.1 Hz,), 7.71 – 7.95 (15H, m, PPh3), 13C NMR (MeOD): δ = 22.6 (d, JCP = 51.3 Hz, CH2P+), 23.4 (d, JCP = 4.4 Hz, CH2(CH2)2P+), 27.5 (CH2(CH2)5P+), 29.6 (CH2(CH2)3P+), 29.8 (CH2(CH2)4P+), 30.2 (CH2(CH2)6P+), 31.3 (d, JCP = 16.1 Hz, CH2CH2P+), 40.3 (CH2(CH2)7P+), 43.5 (CH2CONH), 116.4 (C(2), 117.2 (C(5)), 120.0 (d, JCP = 86.1 Hz, 3 × C(1′)), 121.5 (C(6)), 128.5 (C(1)), 131.5 (d, JCP = 12.5 Hz, 3 × C(3′) and 3 × C(5′)), 134.8 (d, JCP = 9.7 Hz, 3 × C(6′) and 3 × C(2′)), 136.3 (d, JCP = 2.9 Hz, 3 × C(4′)), 145.4 (C(4), 146.4 (C(3)), 174.7 (CO).

(8-(2-(3,4,5-trihydroxyphenyl)acetamido)octyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide (5v). Procedure D1. η = 20 %. 1H NMR (MeOD): δ = 1.2 – 1.3 (6H, m, (CH2)3CH2CH2CH2P+), 1.4 – 1.5 (4H, m, CH2CH2CH2P+), 1.6 – 1.7 (2H, m, CH2(CH2)6P+), 3.1 (2H, t, J = 6.9 Hz, CH2(CH2)7P+), 3.2 (2H, s, CH2CONH), 3.3 – 3.4 (2H, m, CH2P+), 6.3 (2H, s, H(2) and H(6)), 7.7 – 7.9 (15H, m, PPh3). 13C NMR (MeOD): δ = 22.6 (d, JCP = 51.0 Hz, CH2P+), 23.5 (d, JCP = 4.4 Hz, CH2(CH2)2P+), 27.4 (CH2(CH2)5P+), 29.6 (CH2(CH2)3P+), 29.8 (CH2(CH2)4P+), 30.2 (CH2(CH2)6P+), 31.3 (d, JCP = 16.1 Hz, CH2CH2P+), 40.3 (CH2(CH2)7P+), 43.7 (CH2CONH), 109.1 (C(2) and 3 × C(6)), 120.0 (d, JCP = 86.2 Hz, 3 × C(1′)), 127.8 (C(1)), 131.5 (d, JCP = 12.7 Hz, 3 × C(3′) and 3 × C(5′)), 133.2 (C(4)), 134.8 (d, JCD = 9.9 Hz, 3 × C(6′) and 3 × C(2′)), 136.2 (d, JCD = 3.1 Hz, 3 × C(4′)), 147.1 (C(5) and C(3), 174.6 (CO).

(8-(3-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)propanamido)octyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide (5w). Procedure D1. η = 62 %. 1H NMR (MeOD): δ = 1.12 – 1.42 (8H, m, (CH2)4CH2CH2P+), 1.48 – 1.58 (2H, m, CH2CH2P+), 1.61 – 1.74 (2H, m, CH2(CH2)6P+), 2.38 (2H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, CH2CONH), 2.73 (2H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, CH2CH2CONH), 3.08 (2H, t, J = 6.9 Hz, CH2(CH2)7P+), 3.34 – 3.45 (2H, m, CH2P+), 6.49 (1H, dd, J = 8.0, 2.1 Hz, H(6)), 6.61 (1H, d, J = 2.1 Hz, H(2)), 6.63 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, H(5)), 7.70 – 7.93 (15H, m, PPh3). 13C NMR (MeOD): δ = 22.7 (d, JCP = 50.8 Hz, CH2P+), 23.5 (d, JCP = 4.4 Hz, CH2(CH2)2P+), 27.6 (CH2(CH2)5P+), 29.7 (CH2(CH2)3P+), 30.0 (CH2(CH2)4P+), 30.3 (CH2(CH2)6P+), 31.5 (d, JCP = 16.1 Hz, CH2CH2P+), 32.5 (CH2CH2CONH), 39.4 (CH2CH2CONH), 40.2 (CH2(CH2)7P+), 116.3 (C(5)), 116.7 (C(2)), 120.1 (d, JCP = 86.3 Hz, 3 × C(1′)), 120.6 (C6), 131.6 (d, JCP = 12.6 Hz, 3 × C(3′) and 3 × C(5′)), 133.7 (C(1)), 134.9 (d, JCP = 9.9 Hz, 3 × C(6′) and 3 × C(2′)), 136.3 (d, J = 3.1 Hz, 3 × C(4′)), 144.7 (C(3)), 146.2 (C(4)), 175.4 (CO).

(8-(3-(3,4,5-trihydroxyphenyl)propanamido)octyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide (5x). Procedure D1. η = 61 %. 1H NMR (MeOD): δ = 1.10 – 1.43 (8H, m, (CH2)4CH2CH2P+), 1.49 – 1.59 (2H, m, CH2CH2P+), 1.58 – 1.73 (2H, m, CH2(CH2)6P+), 2.37 (2H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, CH2CONH), 2.67 (2H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, CH2CH2CONH), 3.08 (2H, t, J = 6.9 Hz, CH2(CH2)7P+), 3.34 – 3.46 (2H, m, CH2P+), 6.19 (2H, s, C(6) and C(2)), 7.69 – 7.98 (15H, m, PPh3). 13C NMR (MeOD): δ = 22.7 (d, JCP = 51.0 Hz, CH2P+), 23.5 (d, JCP = 4.3 Hz, CH2(CH2)2P+), 27.6 (CH2(CH2)5P+), 29.6 (CH2(CH2)3P+), 29.9 (CH2(CH2)4P+), 30.2 (CH2(CH2)6P+), 31.4 (d, JCP = 16.0 Hz, CH2CH2P+), 32.7 (CH2CH2CONH), 39.3 (CH2CH2CONH), 40.2 (CH2(CH2)7P+), 108.3 (C(6) and C(2)), 120.0 (d, JCP = 86.4 Hz, 3 × C(1′)), 131.5 (d, JCP = 12.5 Hz, 3 × C(3′) and 3 × C(5′)), 132.5 (C(1)), 133.1 (C(4)), 134.8 (d, JCP = 10.0 Hz, 3 × C(6′) and 3 × C(2′)), 136.2 (d, JCP = 3.1 Hz, 3 × C(4′)), 146.9 (C(5) and C(3)), 175.3 (CO).

(7-((3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)amino)-7-oxoheptyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide (11a). Procedure D2. η = 36 %. 1H NMR (DMSO‑d6): δ = 1.24 – 1.34 (2H, m, CH2(CH2)2P+), 1.44 – 1.57 (6H, m, (CH2)2CH2CH2CH2P+), 2.20 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2(CH2)5P+), 3.52 – 3.62 (2H, m, CH2P+), 6.60 (1H, d, J = 8.5 Hz, H(5)), 6.77 (1H, dd, J = 2.4, 8.5 Hz, H(6)), 7.12 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz, H(2)), 7.73 – 7.93 (15H, m, PPh3), 8.71 (2H, s, 2 × OH), 9.50 (1H, s, NH). 13C NMR (DMSO‑d6): δ = 20.2 (d, JCP = 49.7 Hz, CH2P+), 21.6 (d, JCP = 4.0 Hz, CH2(CH2)2P+), 24.8 (CH2(CH2)4P+), 27.8 (CH2(CH2)3P+), 29.6 (d, JCP = 16.8 Hz, CH2CH2P+), 36.1 (CH2(CH2)5P+), 107.9 (C(2)), 110.2 (C(6)), 115.1 (C(5)), 118.6 (d, JCP = 85.7 Hz, 3 × C(1′)), 130.2 (d, JCP = 12.4 Hz, 3 × C(3′) and 3 × C(5′)), 131.5 (C(1)), 133.6 (d, JCP = 10.1 Hz, 3 × C(2′) and 3 × C(6′)), 134.9 (d, JCP = 2.8 Hz, 3 × C(4′)), 141.0 (C(4)), 144.8 (C(3)), 170.2 (CO).

(7-((3,4,5-trihydroxyphenyl)amino)7-oxoheptyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide (11b). Procedure D1. η = 55 %. 1H NMR (DMSO‑d6): δ = 1.21 – 1.34 (2H, m, CH2(CH2)2P+), 1.40 – 1.57 (6H, m, (CH2)2CH2CH2CH2P+), 2.18 (2H, t, J = 7.3 Hz, CH2(CH2)5P+), 3.51 – 3.62 (2H, m, CH2P+), 6.60 (2H, m, H(2) and H(6)), 7.71 – 7.93 (15H, m, PPh3), 9.37 (1H, s, NH). 13C NMR (DMSO‑d6): δ = 20.2 (d, JCP = 49.5 Hz, CH2P+), 21.7 (d, JCP = 4.5 Hz, CH2(CH2)2P+), 24.9 (CH2(CH2)4P+), 27.8 (CH2(CH2)3P+), 29.7 (d, JCP = 16.4 Hz, CH2CH2P+), 36.2 (CH2(CH2)5P+), 98.9 (C(2) and C(6)), 118.6 (d, JCP = 85.6 Hz, 3 × C(1′)), 128.8 (C(4)), 130.2 (d, JCP = 12.4 Hz, 3 × C(3′) and 3 × C(5′)), 130.9 (C(1)), 133.6 (d, JCP = 10.1 Hz, 3 × C(2′) and 3 × C(6′)), 134.9 (d, JCP = 3.2 Hz, 3 × C(4′)), 145.8 (C(3) and C(5)), 170.2 (CO).

(9-((3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)amino)-9-oxononyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide (11c). Procedure D2. η = 62 %. 1H NMR (DMSO‑d6): δ = 1.15 – 1.33 (6H, m, (CH2)3(CH2)2P+), 1.36 – 1.64 (6H, m, (CH2)2(CH2)3CH2CH2P+), 2.20 (2H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, CH2(CH2)7P+), 3.48 – 3.65 (2H, m, CH2P+), 6.60 (1H, d, J = 8.5 Hz, H(5)), 6.77 (1H, dd, J = 2.5, 8.5 Hz, H(6)), 7.13 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz, H(2)), 7.63 – 8.00 (15H, m, PPh3), 9.49 (1H, s, NH). 13C NMR (DMSO‑d6): δ = 20.1 (d, JCP = 49.9 Hz, CH2P+), 21.7 (d, JCP = 4.4 Hz, CH2(CH2)2P+), 25.2 (CH2(CH2)6P+), 28.0 ((CH2(CH2)5P+), 28.5 ((CH2)2(CH2)3P+), 29.8 (d, JCP = 16.7 Hz, CH2CH2P+), 36.3 (CH2(CH2)7P+), 107.9 (C(2)), 110.3 (C(6)), 115.2 (C(5)), 118.6 (d, JCP = 85.6 Hz, 3 × C(1′)), 130.2 (d, JCP = 12.4 Hz, 3 × C(3′) and 3 × C(5′)), 131.5 (d, JCP = 10.1 Hz, 3 × C(2′) and 3 × C(6′)), 134.9 (d, JCP = 2.9 Hz, 3 × C(4′)), 134.9 (C(1)), 141.0 (C(4)), 144.8 (C(3)), 170.4 (CO).

(9-((3,4,5-trihydroxyphenyl)amino)9-oxononyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide (11d). Procedure D1. η = 90 %. 1H NMR (DMSO‑d6): δ = 1.13 – 1.32 (6H, m, (CH2)3(CH2)2P+), 1.38 – 1.59 (6H, m, (CH2)2(CH2)3CH2CH2P+), 2.19 (2H, t, J = 7.3 Hz, CH2(CH2)7P+), 3.51 – 3.64 (2H, m, CH2P+), 6.61 (2H, H(2) and H(6)), 7.70 – 7.95 (15H, m, PPh3), 9.37 (1H, s, NH). 13C NMR (DMSO‑d6): δ = 20.1 (d, JCP = 50.0 Hz, CH2P+), 21.7 (d, JCP = 4.5 Hz, CH2(CH2)2P+), 25.2 (CH2(CH2)6P+), 28.0 ((CH2(CH2)5P+), 28.5 ((CH2)2(CH2)3P+), 29.8 (d, JCP = 16.2 Hz, CH2CH2P+), 36.3 (CH2(CH2)7P+), 99.0 (C(2) and C(6)), 118.6 (d, JCP = 85.6 Hz, 3 × C(1′)), 128.8 (C(4)), 130.2 (d, JCP = 12.4 Hz, 3 × C(3′) and 3 × C(5′)), 130.9 (C(1)), 133.6 (d, JCP = 10.1 Hz, 3 × C(2′) and 3 × C(6′)), 134.9 (d, JCP = 2.9 Hz, 3 × C(4′)), 145.7 (C(3) and C(5)), 170.4 (CO).

(11-((3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)amino)-11-oxoundecyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide (11e). Procedure D2. η = 41 %. 1H NMR (DMSO‑d6): δ = 1.10 – 1.33 (10H, m, (CH2)5(CH2)2P+), 1.36 – 1.63 (6H, m, (CH2)2(CH2)5CH2CH2P+), 2.21 (2H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, CH2(CH2)9P+), 3.48 – 3.62 (2H, m, CH2P+), 6.60 (1H, d, J = 8.5 Hz, H(5)), 6.77 (1H, dd, J = 2.4, 8.5 Hz, H(6)), 7.13 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz, H(2)), 7.67 – 7.98 (15H, m, PPh3), 8.54 (1H, s, OH), 8.85 (1H, s, OH), 9.49 (1H, s, NH). 13C NMR (DMSO‑d6): δ = 20.1 (d, JCP = 49.9 Hz, CH2P+), 21.7 (d, JCP = 4.4 Hz, CH2(CH2)2P+), 25.2 (CH2(CH2)8P+), 28.0 (CH2(CH2)7P+), 28.6 (CH2(CH2)2CH2(CH2)3P+), 28.7 ((CH2)2(CH2)4P+), 29.7 (d, JCP = 16.4 Hz, CH2CH2P+), 36.3 (CH2(CH2)9P+), 107.9 (C(2)), 110.3 (C(6)), 115.1 (C(5)), 118.6 (d, JCP = 85.6 Hz, 3 × C(1′)), 130.2 (d, JCP = 12.4 Hz, 3 × C(3′) and 3 × C(5′)), 131.5 (C(1)), 133.6 (d, JCP = 10.1 Hz, 3 × C(2′) and 3 × C(6′)), 134.9 (d, JCP = 2.9 Hz, 3 × C(4′)), 141.0 (C(4)), 144.8 (C(3)), 170.2 (CO).

(11-((3,4,5-trihydroxyphenyl)amino)11-oxoundecyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide (11f). Procedure D1. η = 93 %. 1H NMR (DMSO‑d6): δ = 1.12 – 1.32 (10H, m, (CH2)5(CH2)2P+), 1.37 – 1.58 (6H, m, (CH2)2(CH2)5CH2CH2P+), 2.19 (2H, t, J = 7.3 Hz, CH2(CH2)9P+), 3.49 – 3.63 (2H, m, CH2P+), 6.61 (2H, H(2) and H(6)), 7.71 – 7.94 (15H, m, PPh3), 9.37 (1H, s, NH). 13C NMR (DMSO‑d6): δ = 20.2 (d, JCP = 49.7 Hz, CH2P+), 21.7 (d, JCP = 4.2 Hz, CH2(CH2)2P+), 25.3 (CH2(CH2)8P+), 28.0 (CH2(CH2)7P+), 28.6 (CH2(CH2)6P+), 28.7 (CH2CH2CH2(CH2)3P+), 28.8 (CH2(CH2)4P+), 29.7 (d, JCP = 16.3 Hz, CH2CH2P+), 36.4 (CH2(CH2)9P+), 99.0 (C(2) and C(6)), 118.6 (d, JCP = 85.6 Hz, 3 × C(1′)), 128.8 (C(4)), 130.2 (d, JCP = 12.4 Hz, 3 × C(3′) and 3 × C(5′)), 130.9 (C(1)), 133.6 (d, JCP = 10.1 Hz, 3 × C(2′) and 3 × C(6′)), 134.9 (d, JCP = 2.8 Hz, 3 × C(4′)), 145.8 (C(3) and C(5)), 170.4 (CO).

Pharmacology

Antimicrobial screenings

All screening was performed as two replicas (n = 2) on different assay plates, but from single plating and performed in a single screening experiment (microbial incubation). In addition, two values were used as quality controls for individual plates: Z'-Factor = [1-(3*(sd(NegCtrl) + sd(PosCtrl))/(average(PosCtrl)-average(NegCtrl)))] [22] and Standard Antibiotic controls at different concentrations (>MIC and < MIC). The plate passes the quality control if Z'-Factor > 0.4 and Standards were active and inactive at highest and lowest concentrations, respectively (data not supplied).

Standards and sample preparation

Colistin and vancomycin were used as positive bacterial inhibitor references for Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, respectively. Fluconazole was used as a positive fungal inhibitor reference for C. albicans and C. neoformans var. grubii. Tamoxifen and melittin were used as positive references for cytotoxicity and heamolysis, respectively.

Stock solutions of compounds were prepared in DMSO. Samples were prepared in DMSO and water to a final testing concentration of 32 μg/mL in 384-well, non-binding surface plate (NBS) for each bacterial/fungal strain, and in duplicate (n = 2), and keeping the final DMSO concentration to a maximum of 1 % DMSO. The sample preparation was done using liquid handling robots.

Antimicrobial screening

In vitro antibacterial and antifungal activities were determined on the basis of MIC values. Stock solutions of the test compounds were prepared in DMSO. Compounds were plated as a 2-fold dose response from 32 to 0.25 μg/mL (or 20 to 0.156 μM), with a maximum concentration of DMSO of 0.5 %. The determination of MIC values was performed following the Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines [23], identifying the lowest concentration at which full inhibition of the bacteria or fungi has been detected. Full inhibition of growth has been defined at ≤ 20% growth (or > 80% inhibition), and concentrations have only been selected if the next highest concentration displayed full inhibition (i.e. 80–100%) as well (eliminating 'singlet' active concentration).

Evaluation of antibacterial activity

All bacteria (S. aureus ATCC 43300; E. coli ATCC 25922, K. pneumoniae ATCC 70060, P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853, A. baumannii ATCC 19606) were cultured in cation-adjusted Mueller Hinton broth (CAMHB) at 37 °C overnight. A sample of each culture was then diluted 40-fold in fresh broth and incubated at 37 °C for 1.5–3 h. The resultant mid-log phase cultures were diluted (CFU/mL measured by OD600 nm), then added to each well of the compound containing plates, giving a cell density of CFU/mL and a total volume of 50 μL. All the plates were covered and incubated at 37 °C for 18 h without shaking.

The growth inhibition of all bacteria was determined measuring absorbance at 600 nm (OD600), using a Tecan M1000 Pro monochromator plate reader. The percentage of growth inhibition was calculated for each well, using the negative control (media only) and positive control (bacteria without inhibitors) on the same plate as references. The significance of the inhibition values was determined by modified Z-scores, calculated using the median and MAD of the samples (no controls) on the same plate [24]. Samples with inhibition value above 80% and Z-Score above 2.5 for either replicate (n = 2 on different plates) were classed as actives.

Evaluation of antifungal activity.

Fungi strains (C. albicans ATCC 90028 and C. neoformans var. grubii H99 ATCC 208821) were cultured for 3 days on Yeast Extract-Peptone Dextrose (YPD) agar at 30 °C. A yeast suspension of to CFU/mL (as determined by OD530 nm) was prepared from five colonies. The suspension was subsequently diluted and added to each well of the compound-containing plates giving a final cell density of fungi suspension of CFU/mL and a total volume of 50 μL. All plates were covered and incubated at 35 °C for 24 h without shaking.

The growth inhibition of C. albicans was determined by measuring the absorbance at 530 nm (OD530 nm). The growth inhibition of C. neoformans var. grubii was determined by measuring the difference in absorbance between 600 and 570 nm (OD600-570), following the addition of resazurin (0.001 % final concentration) and incubation at 35 °C for additional 2 h. The absorbance was measured using a Biotek Synergy HTX plate reader. The percentage of growth inhibition was calculated for each well, using the negative control (media only) and positive control (bacteria without inhibitors) on the same plate as references. The significance of the inhibition values was determined by modified Z-scores, calculated using the median and MAD of the samples (no controls) on the same plate. Samples with inhibition value above 80% and Z-Score above 2.5 for either replicate (n = 2 on different plates) were classed as actives.

Evaluation of cytotoxicity profile

HEK293 cells (ATCC CRL-1573) were counted manually in a Neubauer haemocytometer and then plated in the 384-well plates containing the compounds to give a density of 5000 cells/well in a final volume of 50 μL. DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS was used as growth media and the cells were incubated together with the compounds for 20 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2.

Growth inhibition of HEK293 cells was determined measuring fluorescence at ex:530/10 nm and em:590/10 nm (F560/590), after the addition of resazurin (25 μg/mL final concentration) and incubation at 37 °C and 5% CO2, for additional 3 h. The fluorescence was measured using a Tecan M1000 Pro monochromator plate reader. The percentage of growth inhibition was calculated for each well, using the negative control (media only) and positive control (cell culture without inhibitors) on the same plate as references. CC50 values were obtained from dose-response curves, with variable values for bottom, top and slope. The curve fitting was implemented using Pipeline Pilot's dose–response component.

Evaluation of haemolytic activity

The use of human blood (sourced from LifeBlood) for hemolysis assays was approved by the University of Queensland Institutional Human Research Ethics Committee, Approval Number 2020001239.

Human whole blood was washed three times with 3 volumes of 0.9% NaCl and then resuspended in same to a concentration of cells/mL, as determined by manual cell count in a Neubauer haemocytometer. The washed cells were then added to the 384-well compound-containing plates for a final volume of 50 μL. After a 10 min shake on a plate shaker, the plates were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. After incubation, the plates were centrifuged at 1000 × g for 10 min to pellet cells and debris, 25 μL of the supernatant was transferred to a polystyrene 384-well assay plate. Haemolysis was determined by measuring the supernatant absorbance at 405 nm (OD405). The absorbance was measured using a M1000 Pro monochromator plate reader (Tecan Trading AG, Switzerland) [25].

The determination of HC10 values were performed values were obtained from dose-response curves, with variable values for bottom, top and slope. The curve fitting was implemented using Pipeline Pilot's dose–response component. The curve fitting resulted in HC50 values, which are converted into HC10 using Equation (1).

| (1) |

Evaluation of the antibacterial mechanism of action

The evaluation of the antibacterial mechanism of action of the selected compounds was performed with S. aureus XU212 (Clinical isolate; TetK efflux pump overexpresser; MRSA strain [26]).

Determination of minimum inhibitory concentration and minimum bactericidal concentration

The determination of MIC and MBC values of compounds 5 m and 5n was performed by the broth microdilution method according to Borges et al.[27]. Briefly, an overnight bacterial culture (16–18 h) grown in flasks containing Mueller-Hinton broth (MHB; Oxoid, England) was adjusted to an optical density (OD) of 0.132 ± 0.02 (λ = 600 nm) with fresh MHB. Then, 96-well polystyrene microtiter plates were filled with 20 μL of solutions of the test compounds at different concentrations (final concentrations: 0.0625–32 μg/mL) and 180 μL of bacterial suspension. Positive controls include bacterial suspension without compounds and with DMSO (at 10 %, v/v). After 24 h incubation at 37 °C and 150 rpm, the bacterial growth was analysed by measuring the absorbance at 600 nm in a microtiter plate reader (FLUOstar Omega; BMG LABTECH, Germany). The MIC value was defined as the lowest concentration that prevented the bacterial growth.

After MIC determination, 10 μL of bacterial suspension was directly removed from the wells containing the test compound at concentrations equal to and above the MIC and placed out on MH agar. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h and the growth was visually inspected. The MBC was recorded as the lowest concentration in which total growth inhibition in solid medium was observed.

Evaluation of cytoplasmic membrane integrity

The effects of compounds 5 m and 5n on the cytoplasmic membrane integrity of S. aureus XU212 were evaluated. After exposure with the test compounds at different concentrations (½ MIC, MIC and 2 × MIC) for 1 h, the following measurements were performed: (a) zeta potentials, (b) propidium iodide (PI) uptake and (c) intracellular K+ release. All tests were performed with a minimum of two independent repeats.

-

a.

The zeta potential was determined using a Nano Zetasizer Pro (Malvern Instrument, UK) by applying an electric field across the bacterial suspensions under specific pH and salt concentrations [27].

-

b.

The Live/Dead BacLightTM kit (Invitrogen-Molecular Probes, USA) was applied to assess membrane integrity by selective stain exclusion [27]. The kit includes two nucleic acid-binding stains, SYTO 9 and PI. Green fluorescing SYTO 9™ is able to enter all cells, whereas red fluorescing PI enters only in cells with damaged cytoplasmic membranes. Thus, bacteria with intact cell membranes stain fluorescent green, whereas bacteria with damaged membranes stain fluorescent red.

-

c.

Flame emission and atomic absorption spectroscopy (GBC AAS 932plus device; GBC Avante 1.33 software) were used for K+ titration in bacterial suspensions according to Borges et al. [27].

Statistical analysis

The data obtained are expressed as mean ± standard deviation of at least two independent experiments (n = 2). All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad PRISM version 6 for Windows. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni test was performed for data assuming a normal distribution. Statistical analysis was based on a confidence level of ≥ 95%, where p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results and discussion

Chemistry

The phytochemical-based TPP+ conjugates 5a-x and 11a-f (Fig. 2) were obtained following three- or four-step synthetic strategies presented in Scheme 1, Scheme 2, Scheme 3. Structurally, these tripartite compounds contain a phenolic ring, a carboxamide group and a TPP+ cation and, with all the moieties linked through different inserts (Fig. 1). Structural diversity was attained by modifying the substitution pattern of the aromatic ring, the type of the spacer between the carboxamide function and the aromatic ring, and the length of the alkyl linker between the carboxamide and the TPP+ cation. The aromatic substitution pattern included di- (catechol) or trihydroxyl (pyrogallol) systems that were directly bound to a carboxamide group (Ph-CONH-) or through methylene (n1 = Ph-CH2-), ethylene (n1 = Ph-H2C-CH2-) or vinyl (n1 = Ph-HC = CH–) spacers (Fig. 2). Finally, six- (n2 = 1), eight- (n2 = 2) and ten-carbon (n2 = 3) alkyl linkers were used to connect the carboxamide function to the TPP+ cation. For benzoic acid derivatives, a retro-amide group (Ph-NHCO-) was also considered.

The synthesis of compounds 5a-t followed the strategies previously described by our group[18], [19], [20], [21] and depicted in Scheme 1. Briefly, hydroxyalkylamides 2a-t were obtained by reacting the carboxylic acids 1a-h with the appropriate hydroxyalkylamines using phosphorus oxychloride (Scheme 1, step a) or ethyl chloroformate (Scheme 1, step b) as coupling agents. The hydroxyalkyl groups of the intermediates 2a-t were then activated through generation of the corresponding halides (Scheme 1, step c) or mesylates (Scheme 1, step d). After reaction with triphenylphosphine (TPP), salts 4a-t were obtained (Scheme 1, step e). Subsequent O-demethylation of compounds 4a-t with boron tribromide solution yielded the final phenolic compounds 5a-t.

A different synthetic strategy was developed to obtain compounds 5u-x (Scheme 2), allowing to reduce hands-on time and to streamline the purification steps. First, aminoalkyltriphenylphosphonium salt 7 was synthesized by heating TPP with N-(8-bromooctyl)phthalimide, followed by the cleavage of the phthalimide ring with butylamine (Scheme 2, step a). Then, amidation reaction between carboxylic acids 1c-f and compound 7, using ethyl chloroformate as coupling agent, yielded the intermediates 4u-x (Scheme 2, step b). Finally, an O-demethylation reaction with boron tribromide solution was performed to obtain final phenolic derivatives 5u-x (Scheme 2, step c).

Compounds 11a-f were synthesized by the three-step synthetic strategy depicted in Scheme 3. The first step consisted of the obtention of carboxyalkyltriphenylphosphonium salts 9a-c by heating TPP with the appropriate bromoalkylcarboxylic acid (Scheme 3, step a). Then, ethyl chloroformate-mediated amidations between compounds 9a-c and amines 1i-j yielded compounds 10a-f (Scheme 3, step b). Finally, compounds 11a-f were obtained by O-demethylation of compounds 10a-f. Compounds 10b, 10d and 10f were treated with boron tribromide solution to afford the pyrogallol derivatives 11b, 11d and 11f, respectively (Scheme 3, step c). Compounds 10a, 10c and 10e were refluxed with boron tribromide dimethyl sulfide complex to obtain catechols 11a, 11c and 11e, respectively (Scheme 3, step d).

Antimicrobial screening

Following the synthesis of phytochemical-based TPP+ conjugates 5a-x and 11a-f, a preliminary high throughput screening of their antimicrobial activity was performed. All compounds were screened by the Community for Open Antimicrobial Drug Discovery (CO-ADD) against a key panel of drug-resistant bacterial strains, which include the Gram-positive methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and different Gram-negative bacteria (E. coli, K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, A. baumannii) and fungi (C. albicans and C. neoformans var. grubii) [28]. The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) of compounds against growing planktonic cells were determined using the broth microdilution method. Vancomycin and colistin were used as positive references for Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, respectively. Fluconazole was used as a positive reference for C. albicans and C. neoformans (Table 1). To rationalize the data, compounds were divided into five series (A-E).

Table 1.

MIC values (µg/mL) of the phytochemical-based TPP+ conjugates 5a-x, 11a-f and reference antibiotics against the selected microorganisms.

| Series | Compound | R | n2 | MIC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | E. coli | K. pneumoniae | P. aeruginosa | A. baumannii | C. albicans | C.neoformans | ||||

|

A |

5a | H | 1 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 |

| 5b | OH | 1 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | |

| 5c | H | 2 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | |

| 5d | OH | 2 | 32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | |

| 5e | H | 3 | 8 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | |

| 5f | OH | 3 | 16 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | |

|

B |

5g | H | 1 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 |

| 5h | OH | 1 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | |

| 5u | H | 2 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | |

| 5v | OH | 2 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | |

| 5i | H | 3 | 8 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | 32 | >32 | |

| 5j | OH | 3 | 8 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | 32 | |

|

C |

5k | H | 1 | 32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 |

| 5l | OH | 1 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | |

| 5w | H | 2 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | |

| 5x | OH | 2 | 8 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | |

| 5m | H | 3 | ≤0.25 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | |

| 5n | OH | 3 | ≤0.25 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | |

|

D |

5o | H | 1 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 |

| 5p | OH | 1 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | 16 | |

| 5q | H | 2 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | |

| 5r | OH | 2 | 32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | 16 | |

| 5s | H | 3 | 8 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | 16 | 16 | |

| 5t | OH | 3 | 16 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | 16 | 4 | |

|

E |

11a | H | 1 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | 32 | >32 |

| 11b | OH | 1 | 32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | 32 | |

| 11c | H | 2 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | |

| 11d | OH | 2 | 16 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | 8 | |

| 11e | H | 3 | 16 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | 32 | >32 | |

| 11f | OH | 3 | 2 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | 8 | 4 | |

| Colistin | __ | __ | >32 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | n.d. | n.d. | |

| Vancomycin | __ | __ | 1 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | n.d. | n.d. | |

| Fluconazole | __ | __ | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 0.125 | 8 | |

Standard strains: S. aureus ATCC 43300; E. coli ATCC 25922, K. pneumoniae ATCC 70060, P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853, A. baumannii ATCC 19606, C. albicans ATCC 90028, and C. neoformans var. grubii H99 ATCC 208821.

n.d.: not determined.

Cytotoxicity and haemolytic screening

The cytotoxicity in human embryonic kidney cells (HEK293) and haemolytic activity in human red blood cells (RBC) of the most promising phytochemical-based TPP+ conjugates (compounds 5e, 5f, 5i, 5j, 5 m, 5n, 5p, 5r, 5 s, 5 t, 5x, 11d, 11e and 11f) were evaluated. The results obtained are expressed as concentration at 50 % cytotoxicity (CC50) and concentration at 10 % haemolytic activity (HC10), respectively (Table 2). Tamoxifen and melittin were used as a positive cytotoxicity and haemolytic references, respectively.

Table 2.

Cytotoxicity in HEK293 cells (CC50 in µg/mL) and haemolytic activity in RBC (HC10 in µg/mL) of the most promising phytochemical-based TPP+ conjugates.

| Compound | HEK293 (CC50)a | RBC (HC10) b | Compound | HEK293 (CC50)a | RBC (HC10) b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

9.07 | >32 |  |

>32 | >32 |

|

>32 | >32 |  |

>32 | >32 |

|

31.2 | >32 |  |

10.7 | 11.9 |

|

>32 | >32 |  |

>32 | 6.0 |

|

>32 | >32 |  |

>32 | >32 |

|

>32 | >32 |  |

22.4 | >32 |

|

>32 | >32 |  |

>32 | 11.8 |

| Tamoxifen | 9 | __ | |||

| Mellitin | __ | 2.7 | |||

CC50: concentration at 50 % cytotoxicity in human embryonic kidney (HEK-293) cells. bHC10: concentration at 10% haemolytic activity in human red blood (RBC) cells.

Structure-activity-toxicity relationships.

From the preliminary data obtained (Table 1, Table 2), a structure–activity-toxicity analysis was performed. In general, phytochemical-based TPP+ conjugates acted as moderate or even potent antimicrobial agents. Remarkably, while the benzoyl, phenylacetyl and dihydrocinnamoyl derivatives endowed with antimicrobial activity were selective for S. aureus, cinnamoyl and phenylamide derivatives also presented antifungal activity against C. albicans and C. neoformans var. grubii (Table 1).

A correlation between the length of the alkyl linker and the antibacterial activity against S. aureus was observed. While all compounds containing a ten-carbon alkyl linker acted as antibacterial agents, only two compounds bearing an eight-carbon alkyl linker (compounds 5x and 11d) were active towards S. aureus, presenting higher MIC values than the ten carbon counterparts (compounds 5n and 11f, respectively).

Compared with benzoic acid derivatives (compounds 5d, 5e and 5f), the antibacterial activity against S. aureus was enhanced with the incorporation of methylene (compounds 5v, 5i and 5j) and ethylene spacers (compounds 5x, 5 m and 5n) between the phenolic ring and carboxamide group. Indeed, dihydrocinnamic acid derivatives 5 m and 5n were the most potent antibacterial agents of the series, showing MIC values towards S. aureus below 0.25 µg/mL. Compounds bearing a cinnamoyl moiety (5r, 5 s and 5 t) exhibited higher MIC values towards S. aureus than the related dihydrocinnamic acid derivatives (compounds 5x, 5 m and 5n). Therefore, the low rigidity of the spacer between the carboxamide group and the phenolic ring seems to be critical for effective antibacterial activity against S. aureus. In addition, given the lower or absent antibacterial activity of dihydrocinnamic acid derivatives with six-carbon (compounds 5 k and 5 l) or 8-carbon (compounds 5w and 5x), the synergism between the low rigidity of the ethylene spacer and the longer alkyl linker may be responsible for the high potency of compounds 5 m and 5n. Phenyl amide derivatives 11b, 11d and 11f displayed lower MIC values towards S. aureus than the related benzoic acid derivatives (compounds 5b, 5d and 5f), indicating that the presence of a retro carboxamide group improves the antibacterial activity of TPP+ conjugates containing a pyrogallol moiety.

A direct correlation between longer alkyl linkers and low MIC values was also observed for C. albicans and C. neoformans var. grubii. Only compounds containing a ten-carbon alkyl linker (compounds 5 s, 5 t and 11f) were active towards C. albicans, with the 3,4,5-trihydroxyphenylamide derivative 11f exhibiting the lowest MIC value. Similarly, compounds 5 t and 11f presented lower MIC values towards C. neoformans var. grubii than the related analogues with eight (5r and 11d, respectively) or six-carbon alkyl linkers (5p and 11b, respectively). The substitution pattern of the aromatic ring also influenced the antifungal activity against C. neoformans var. grubii. Except for compound 5 s, which contains a catechol group, only compounds with a pyrogallol moiety (compounds 5p, 5r, 5 t, 11d and 11f) were active against C. neoformans var. grubii.

From the data obtained in the evaluation of the compounds’ cytotoxicity in HEK293 cells (Table 2), it was concluded that most of the bioactive TPP+ conjugates did not exhibit cytotoxic effects; only compounds 5e, 5i, 5 s and 11e displayed CC50 values below 32 µg/mL. All the mentioned compounds contain a catechol ring and a ten-carbon alkyl linker in their structure. Thus, the cytotoxicity observed may result from the combination of injurious effects induced by both structural components. Indeed, catechols can be oxidized into the corresponding ortho-quinones, which in turn can react with cellular nucleophiles or generate reactive species by redox-cycling processes [29]. Additionally, more hydrophobic TPP+ conjugates may negatively affect due to the higher affinity to biological membranes [30]. The CC50 value of benzoyl derivative 5e was similar to cinnamic acid derivative 5 s and lower than phenyl acetyl derivative 5i and retro carboxamide 11e (compound 5e: CC50 = 9.07 µg/mL; compound 5i: CC50 = 31.2 µg/mL; compound 5 s: CC50 = 10.7 µg/mL; compound 11e: CC50 = 22.4 µg/mL). Interestingly, none of the dihydrocinnamic acid derivatives exhibited cytotoxic effects at concentrations below 32 µg/mL. Thus, the presence of an ethylene spacer between the phenolic ring and the amide group was associated with safe cytotoxicity profiles. The presence of a methylene spacer and a retro carboxamide group were also associated with decreased cytotoxicity. Conversely, the introduction of a vinyl spacer did not improve the cytotoxicity profile of catechol TPP+ conjugates.

The most promising TPP+ conjugates were also tested for their haemolytic activity against human RBC (Table 2). The data obtained showed that, except for cinnamoyl and phenylamide derivatives with ten-carbon alkyl linkers (compounds 5 s, 5 t and 11f), most compounds did not show haemolytic effects.

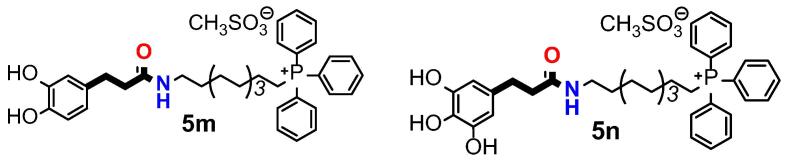

Based on the data obtained so far, we decided to continue our studies with the dihydrocinnamic acid derivatives 5 m and 5n (Fig. 3). The selected compounds exhibited potent and selective antimicrobial activity towards S. aureus ATCC 43300 and were safe at concentrations below 32 µg/mL.

Fig. 3.

Chemical structures of phytochemical-based TPP+ conjugates selected to unravel the antibacterial mechanism of action.

Antibacterial mechanism studies

To investigate the possible antibacterial mechanism of action of dihydrocinnamic acid derivatives 5 m and 5n, several bacterial physiological indices were evaluated. These include MIC, minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC), surface charge, propidium iodide (PI) uptake and intracellular K+ release.

MIC and MBC determination

We first determined the inhibitory and bactericidal properties of each compound against S. aureus (XU212), a clinical isolate with known resistant profile (including TetK efflux pump and resistance to methicillin) and remarkable antibiotic resistance in comparison to other clinical isolates and collection strains of S. aureus [31].

The MIC and MBC values of the selected dihydrocinnamic acid derivatives are summarized in Tables 3. A MIC value of 16 μg/mL was obtained for both compounds (5 m and 5n) against S. aureus (XU212). However, compound 5 m displayed higher bactericidal activity. While compound 5 m presented an MBC of 32 μg/mL, no MBC was obtained with compound 5n at the maximum concentration tested (32 μg/mL).

Table 3.

MIC and MBC values (μg/mL) of compounds 5 m and 5n for S. aureus XU212.

| Compound | MIC (μg/mL) | MBC (μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| 5 m | 16 | 32 |

| 5n | 16 | > 32 |

Alterations in the surface charge

Following the determination of the compounds’ antibacterial activity on S. aureus (XU212), we characterized their effects by evaluating surface charge alterations and cytoplasmic membrane disruption. To induce bacterial growth inhibition or even cell dead, a compound needs first to interact with the cell surface and eventually reach the intracellular content.

The cell envelope of bacteria is a complex, dynamic and multilayered structure, which serves as the first barrier against external stresses, toxic substances and host-immune defenses. In Gram-positive bacteria, the cell envelope is primarily composed of peptidoglycan, teichoic acids (TAs) and a variety of proteins, as well as polysaccharides and phospholipids. The lipid bilayer contains a large amount of cardiolipin and phosphatidylglycerol, being the lysyl type the predominant membrane lipid in S. aureus. The membrane play a key role in cellular integrity and in bacterial viability, being vital to maintain cellular homeostasis [32], [33].

A very relevant factor related with microbial stability/equilibrium and antibacterial resistance is the charge of the cell surface. Under physiological conditions, bacterial cells (Gram-negative or Gram-positive) usually have a negative surface charge due to the presence of anionic groups (e.g. carboxylic acid and phosphate) in their walls/membranes. This property varies within the species and can be influenced by several external conditions that can disturb lipid composition, such as culture age, ionic strength, temperature and pH [27], [34]. In Gram-positive bacteria, the anionic membrane phospholipids and the phosphoryl groups located in the TAs tails of the cell wall (both wall teichoic acids (WTA) and lipoteichoic acids (LTA)) contribute to the negative surface charge [35].

To investigate whether the surface charge of S. aureus (XU212) is affected by compounds 5 m and 5n, the zeta potentials were measured (Table 4).

Table 4.

Zeta potential (mV) values of S. aureus XU212 before (cells and cells + DMSO) and after contact with compounds 5 m and 5n at different concentrations (½ MIC, MIC and 2 × MIC) for 1 h.

| Zeta Potential (mV) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Controls |

5 m |

5n |

|||||

| Cells | Cells + DMSO | ½ MIC a | MIC a | 2 × MIC a | ½ MIC a | MIC a | 2 × MIC a |

| −25.06 ± 6.10 | −21.65 ± 4.58 | −19.22 ± 1.22 | −18.91 ± 0.84 | −19.11 ± 0.95 | −18.14 ± 0.31 | −18.35 ± 0.50 | −18.38 ± 0.25 |

½ MIC = 8 μg/mL; MIC = 16 μg/mL; 2 × MIC = 32 μg/mL.

The results showed that, in the absence of the compounds, S. aureus (XU212) exhibited a negative potential (cells: ∼ −25 mV; cells + DMSO: ∼ −21 mV). When exposed to compounds 5 m and 5n, a small shift to less negative values was observed. Since the compounds tested contain a TPP+ cation, they can interact with the negatively charged TAs from bacterial cell wall through electrostatic interactions. These results suggest that the negatively charged phosphate group of WTA and LTA can attract the positively charged TPP+ group of compounds 5 m and 5n.

The high binding affinity between the compounds and the bacterial cell wall may promote the compounds’ access to the cytoplasmic membrane, being capable of traversing from outside to the internal environment and thus exert its antimicrobial effects [35]. However, although TAs have been associated with cation binding (such as the compounds in study), some entrapment or ladder effect along the route to the plasma membrane may also occur [35]. For instance, the interaction of cationic antimicrobial peptides with peptidoglycans present in the cell wall seems to contribute to reduced antimicrobial activity. Moreover, the interaction with TAs, particularly LTA, may affect the concentration of compounds in the cytoplasmic required to promote positive membrane destabilization and/or killing [35]. In fact, in S. aureus, the positive charges of lysyl-phosphatidylglycerol from the cytoplasmic membrane are important in the repulsion of positively charged antibiotics or antibiotic-metal complexes. Therefore, the modulation of the negative charge density or cation homeostasis of the cell envelope, for instance by lysinylation of phosphatidylglycerol and D-alanylation of TA, can be a relevant aspect in the infection treatment. WTA is one of the main factors related to methicillin resistance in S. aureus, and its absence contribute to a greater susceptibility to this antibiotic [32]. The few available studies with SKQ1 suggest that its antibacterial mechanism of action may involve the neutralization of the bacterial membrane potential [16], [17]. Thus, the antimicrobial activity of compounds 5 m and 5n may also result from surface charge effects.

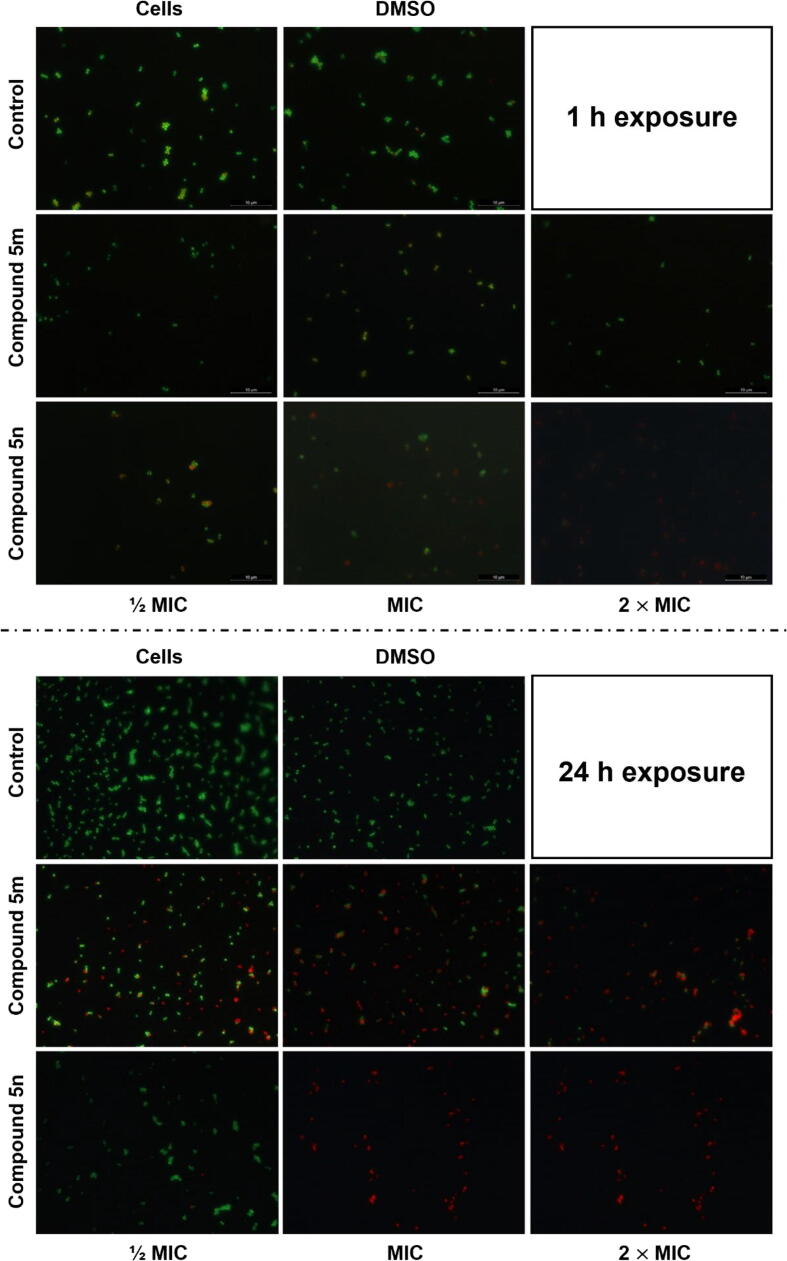

Bacterial membrane integrity

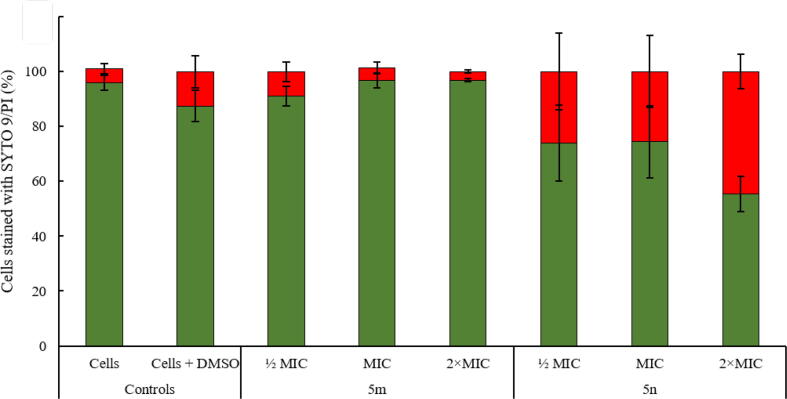

The potential of the selected dihydrocinnamic acid derivatives to interfere with bacterial membrane integrity after 1 h exposure at different concentrations (½ MIC, MIC and 2 × MIC;) was also analyzed. Cytoplasmic membrane permeabilization was studied to a certain extent by evaluating PI uptake through epifluorescence microscopy (Fig. 4, Fig. 5). PI is a nucleic acid stain to which intact cell membranes are usually impermeable.

Fig. 4.

Percentage of S. aureus XU212 cells stained with SYTO 9 (Intact cell membranes;  ) and PI (Damaged cell membranes;

) and PI (Damaged cell membranes;  ) after 1 h exposure to compounds 5 m and 5n at different concentrations (½ MIC, MIC and 2 × MIC). Results are expressed as mean values ± standard deviation of at least two replicates (n = 2). Bars marked with * are statistically different from control (S. aureus (XU212) cells not exposed to tested compounds – Cells + DMSO). One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni test was performed for data assuming a normal distribution. Statistical analysis was based on a confidence level of ≥ 95%, where p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

) after 1 h exposure to compounds 5 m and 5n at different concentrations (½ MIC, MIC and 2 × MIC). Results are expressed as mean values ± standard deviation of at least two replicates (n = 2). Bars marked with * are statistically different from control (S. aureus (XU212) cells not exposed to tested compounds – Cells + DMSO). One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni test was performed for data assuming a normal distribution. Statistical analysis was based on a confidence level of ≥ 95%, where p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Fig. 5.

Representative epifluorescence micrographs of S. aureus XU212 cells visualized using Live/Dead BacLightTM kit (SYTO 9 and PI). The S. aureus XU212 cells were treated with compounds 5 m and 5n at different concentrations (½ MIC, MIC and 2 × MIC) for 1 h and 24 h. Controls: no treatment (cells not exposed to tested compounds – Cells; cells exposed to DMSO solvent (at 10% v/v) – Cells + DMSO). Scale bar: 10 μm.

The results obtained demonstrated that, compared to control experiments (cells not exposed to tested compounds – 5.2% and cells exposed to solvent DMSO – 12.5%), only treatment with compound 5n inflicted damage (increased PI uptake) on the cytoplasmic membrane of S. aureus (XU212) (Fig. 4). The effects observed for compound 5n were dose-dependent, with the percentage of cells with damaged membranes increasing from 26.1% (at ½ MIC) to 44.7% (at 2 × MIC)) (p < 0.05). Interestingly, some morphological “deformation” of the bacterial cells, denoted by surface irregularities and broken form, was observed. In fact, despite the low resolution of epifluorescence microscopy, it was possible to visualize a loss of the perfect spherical shape of the cell surface of native cells (without treatment).

The effects of compound 5n on the structure of bacterial cell membranes [36] may result from alterations in the rigidity and dynamics of phospholipid chains [37]. The induction of large pore formation in lipid membranes may also occur, as previously demonstrated for other phenolic compounds such as (-)-epigallocatechin gallate [38].

Given the low MIC/MBC values obtained for dihydrocinnamic derivatives 5 m and 5n (Table 3), we expect more pronounced effects on membrane permeabilization experiments. However, since S. aureus XU212 cells were exposed to the test compounds for different periods in the determination of MIC/MBC values (24 h) and in the measurement of zeta potentials (1 h), we hypothesize that the inhibitory/killing effect is not immediate. In fact, it is plausible that the membrane disruption is time-dependent, resulting from a gradual compound accumulation within the cells. This is specifically evidenced in the epifluorescence images of 24 h Live/Dead membrane permeabilization assays, where a considerable number of cells with damaged membranes can be observed for both compounds at MIC and 2 × MIC (Fig. 5).

Cytoplasmic leakage

In a work conducted by Pérez-Peinado et al. [39], they concluded that the mechanism of bacterial membrane disruption of cationic peptides involved three main stages: (1) initial peptide recruitment; (2) peptide accumulation; and (3) cell death by membrane disruption. They also showed that the antimicrobial activity only occurs when a threshold concentration on the bacterial surface is attained.

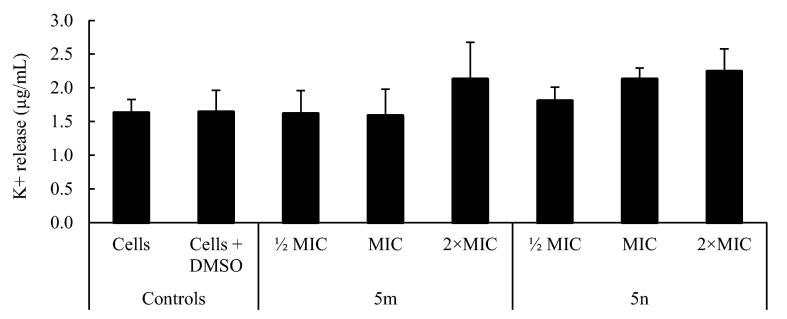

Since the cytoplasmic membrane of bacteria also acts as a barrier between the cytoplasm and the extracellular medium, the leakage of cytoplasmic material like ions provide a good indication on the membrane weakening. Indeed, K+ leakage is considered one of the first indicators of membrane damage in microorganisms [40] In this context, we monitored the bacterial release of K+ after exposure to compounds 5 m and 5n for 1 h. The results presented in Fig. 6 showed the occurrence of primary membranolytic events with compound 5 m at 2 × MIC (2.12 ± 0.55 μg/mL) and with 5n at all concentrations tested (½ MIC = 1.80 ± 0.21; MIC = 2.13 ± 0.17; 2 × MIC = 2.24 ± 0.34) (P < 0.05), corroborating the data obtained in PI uptake experiments (Fig. 4). The release of intracellular content may indicate the formation of a local pore in the phospholipid membranes and not just on its destabilization.

Fig. 6.

K+ release (μg/mL) by S. aureus XU212 before (cells and cells + DMSO) and after exposure to compounds 5 m and 5n at different concentrations (½ MIC, MIC and 2 × MIC) for 1 h. Results are presented as mean values ± standard deviation for at least two replicates (n = 2). One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni test was performed for data assuming a normal distribution. Statistical analysis was based on a confidence level of ≥ 95%, where p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

In summary, the data obtained so far indicate that dihydrocinnamic acid derivatives 5m and 5n exert their antibacterial activity by targeting mainly the bacterial surface. We hypothesize that the antimicrobial activity of compounds 5m and 5n may result from their interaction with cell surface components required for microbial growth and survival (e.g. peptidoglycan, TA, proteins and other critical biological macromolecules), accumulating on the cell membrane or forming a monolayer around the cell that changes the membrane potential and induce local rupture and/or pore formation. The results further propose that the antimicrobial action happens in a sequence of events, starting with a change of the membrane surface charge, followed by the disruption of the membrane integrity. A comparable mode of action was observed previously when S. aureus was exposed to a hydroxycinnamic acid and a hydroxybenzoic acid [27].

Since some of the phytochemical-based TPP+ conjugates can remodel mitochondrial bioenergetics by modulating mitochondrial respiration [41], [42], additional studies are envisioned to better understand their antibacterial mechanism of action. Like mitochondria, bacteria depend on an electrochemical gradient of protons across the cytoplasmic membrane, known as proton motive force, which drives crucial processes in bacteria [43]. Phytochemical-based TPP+ conjugates may also have protonophoric/ionophoric activity. The ionization of the phenol group (pKa > 8) can occur in certain compartments [44], [45] and may diffuse across the membranes, transport protons or other cations, and equilibrate/dissipate ionic gradients [46].

Conclusions

In this work, phytochemical-based TPP+ conjugates were successfully synthesized and screened towards different bacterial and fungal strains. From structure-activity-toxicity studies, it was concluded that the presence of a ten-carbon alkyl linker between the carboxamide group and the TPP+ cation enhances the antimicrobial activity of compounds. The incorporation of methylene and ethylene spacers improved the bioactivity and the safety of compounds while preserving their selectivity towards S. aureus. In contrast, the introduction of a vinyl spacer and the retro-amide group endowed lipophilic TPP+ cations with antifungal activity, although it was also accompanied with cytotoxic and/or haemolytic effects. While no correlation was found between the substitution pattern of the phenolic ring and the bioactivity towards S. aureus and C. albicans, pyrogallol derivatives were more active towards C. neoformans var. grubii than catechols. The presence of a catechol group was associated with increased cytotoxicity, especially when combined with a ten-carbon alkyl linker. Based on the studies performed to unravel the antibacterial mechanism of action of TPP+ conjugates 5m and 5n, it was concluded that the lipophilic and cationic nature of these compounds are important features for cell wall interaction and penetration in S. aureus. Phytochemical-based TPP+ conjugates may access the bacterial cell membrane, promoting its destabilization thought the disruption of the transmembrane potential and local rupture with leakage of important cytoplasmic constituents.

Overall, the data obtained provides valuable insights in the development of phytochemical-based TPP+ conjugates with antimicrobial activity and possibly to the discovery of a new class of antibiotics. Novel lead compounds can be optimized in a foreseeable future and translated into a drug candidate able to tackle MDR bacteria.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Daniel Chavarria: Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. Anabela Borges: Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. Sofia Benfeito: Investigation. Lisa Sequeira: Investigation. Marta Ribeiro: Investigation. Catarina Oliveira: Investigation. Fernanda Borges: Conceptualization, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision. Manuel Simões: Conceptualization, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Fernando Cagide: Conceptualization, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements