Abstract

Melanoma is a cancer of the neural crest–derived cells that provide pigmentation to skin and other tissues. Over the past 4 decades, the incidence of melanoma has increased more rapidly than that of any other malignancy in the United States. No current treatments substantially enhance patient survival once metastasis has occurred. This review focuses on recent insights into melanoma genetics and new therapeutic approaches being developed based on these advances.

History and clinical features of melanoma

The first accredited report of melanoma is found in the writings of Hippocrates (born c. 460 BC), where he described “fatal black tumors with metastases.” Paleopathologists discovered diffuse bony metastases and round melanotic masses in the skin of Peruvian mummies of the fourth century BC (1). However, it was not until 1806, when René Laennec described “la melanose” to the Faculté de Médecine in Paris, that the disease was characterized in detail and named (2). General practitioner William Norris suggested that melanoma may be hereditary in an 1820 manuscript describing a family with numerous moles and several family members with metastatic lesions (3). Molecular insights over the past 20 years have confirmed Norris’s theory of a significant genetic contribution to the etiology of melanoma.

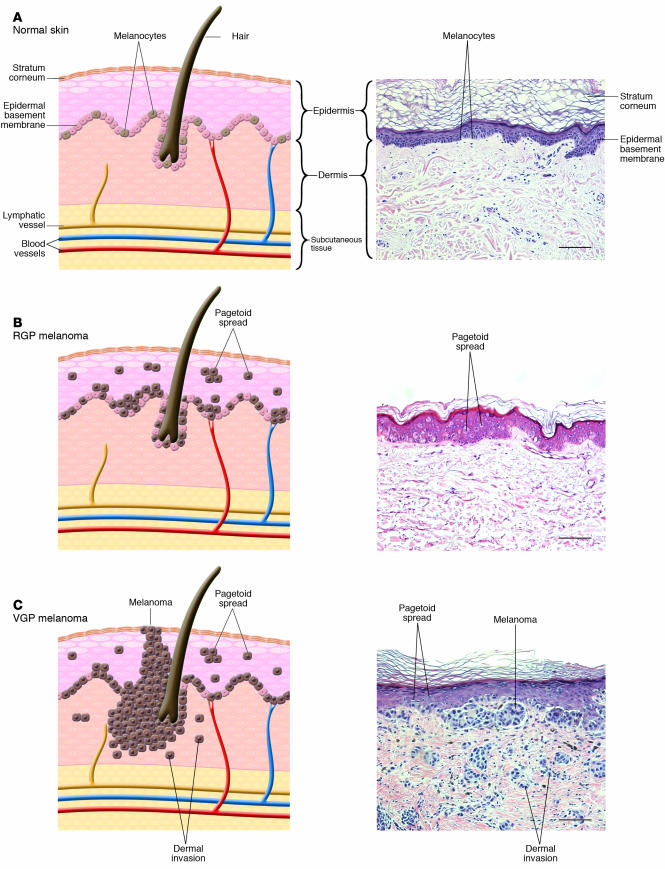

Melanoma develops from the malignant transformation of melanocytes, the pigment-producing cells that reside in the basal epidermal layer in human skin (Figure 1). Recognized as the most common fatal skin cancer, melanoma incidence has increased 15-fold in the past 40 years in the United States, a rate more rapid than that described for any other malignancy (4). Every hour, an American will die from melanoma (5), and it remains one of the most common types of cancer among young adults (6). Furthermore, according to US statistics for 1973–1997, the increase in the mortality rate for melanoma in individuals 65 years of age and older, especially men, was the second highest among all cancers (4).

Figure 1.

Phases of histologic progression of melanocyte transformation. H&E-stained histologic sections and corresponding pictorial representation. (A) Normal skin. There is even distribution of normal dendritic melanocytes in the basal epithelial layer. (B) RGP in situ melanoma. Melanoma cells have migrated into the upper epidermis (pagetoid spread) and are scattered among epithelial cells in a “buckshot” manner. Cells have not penetrated the epidermal basement membrane. Melanoma cells show cytologic atypia, with large abundant cytoplasm and increased overall size compared with normal melanocytes. Nuclei are enlarged and hyperchromatic. Commonly, there is more junctional melanocytic hyperplasia (nests of tumor cells at the basement membrane zone) in RGP melanoma than portrayed in the histologic example. (C) VGP malignant melanoma. Melanoma cells show pagetoid spread and have penetrated the dermal-epidermal junction. Melanoma cells show cytologic atypia. Cells in the dermis cluster or individually invade. Magnification, ×20. Scale bar: 20 μm.

As in many cancers, both genetic predisposition and exposure to environmental agents are risk factors for melanoma development. Case-control studies have identified several risk factors in populations susceptible to developing melanoma (7). Melanoma primarily affects fair-haired and fair-skinned individuals, and those who burn easily or have a history of severe sunburn are at higher risk than their darkly pigmented, age-matched controls. The UV component of sunlight causes skin damage and increases the risk for skin cancers such as melanoma. It appears that melanoma risk is typically associated with intermittent, intense sun exposure rather than cumulative sun exposure (an exception is lentigo maligna melanoma). The exact mechanism and wavelengths of UV light that are the most critical remain controversial, but both UV-A (wavelength 320–400 nm) and UV-B (290–320 nm) have been implicated (4, 8). This is in contrast to the nonmelanoma skin cancers, basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, which arise from epidermal keratinocytes and are more strongly associated with cumulative sun exposure. Melanoma incidence in fair-skinned people is inversely related to latitude of residence, with the highest incidence found in Australia, which supports the role of UV-induced damage in melanoma pathogenesis (9). In the 1920s, women’s fashions became more revealing, and French fashion designer Coco Chanel, who developed a suntan when cruising from Paris to Cannes, is credited with initiating the modern sunbathing trend (10). As our social dress has moved from petticoat and parasol or topcoat and hat to tank top and sunglasses, the incidence of skin cancers, including melanoma, has increased significantly.

Family history of melanoma, increased numbers of both common and dysplastic moles, and a tendency to freckle also increase risk (11). Ten percent of melanoma patients have an affected relative. In a small number of cases, melanomas occur in the setting of the familial atypical multiple mole and melanoma syndrome, also referred to as the dysplastic nevus syndrome (DNS) (12, 13). DNS-affected kindreds develop many atypical moles (dysplastic nevi) at a young age and acquire melanoma with a higher penetrance and earlier onset than are typical of sporadic melanoma. Some evidence suggests that dysplastic nevi may be melanoma precursors in a subset of cases; however, this correlation is controversial and difficult to clearly document (4, 12). More than 50% of melanomas likely arise de novo without a precursor lesion.

Cutaneous melanoma can be subdivided into several subtypes, primarily based on anatomic location and patterns of growth (see Table 1 for key clinical features of subtypes; reviewed in ref. 4). The majority of melanoma subtypes are observed to progress through distinct histologic phases (Figure 1). As melanomas progress from the radial growth phase (RGP) to the vertical growth phase (VGP), treatment options, cure rates, and survival rates decrease dramatically. Most melanoma subtypes demonstrate a slow RGP restricted to the epidermis, followed by a potentially more rapid VGP (14). RGP melanoma cells extend upward into the epidermis (pagetoid spread) but remain in situ and lack the capacity to invade the dermis and metastasize. RGP melanoma is generally cured by excisional surgery. VGP melanoma invades the dermis and deeper structures and is metastatically competent (15, 16).

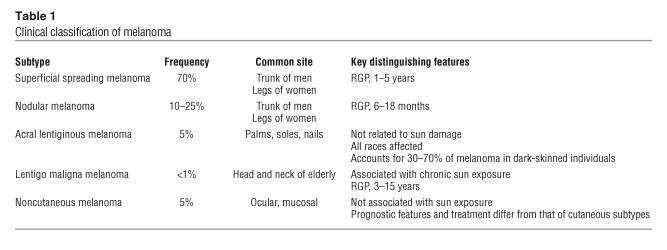

Table 1.

Clinical classification of melanoma

Melanoma can be further classified into clinical stages according to significant prognostic factors, and this staging system was recently revised by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) (see Staging for cutaneous melanoma; a complete staging system is summarized in ref. 17). The AJCC prognostic indicators were confirmed by analysis of outcomes in over 17,000 patients. In the absence of known distant metastasis, the most important prognostic indicator is regional lymph node involvement. However, the majority of melanoma patients present with clinically normal lymph nodes. Thus, in clinically node-negative patients, the microscopic degree of invasion of melanoma is of importance in predicting outcome. There are 2 systems described for microscopic staging of primary cutaneous melanoma, Clark level and Breslow thickness (4). Clark levels classify melanoma according to anatomic landmarks in the epidermis, dermis, and fat (18). While this system correlates with prognosis, an inherent concern with Clark microscopic staging is that the thickness of the skin, and thus the location of these defined landmarks, varies in different parts of the body. Breslow thickness is a measure of the absolute thickness of the tumor from the granular layer (the most superficial nucleated layer of the epidermis) to the deepest contiguous tumor cell at the base of the lesion (19). Breslow thickness has strong prognostic value in those with nonmetastatic melanoma. The presence of regional lymph node metastasis is a concerning sign regardless of the microscopic stage of the primary lesion. However, there is a direct relationship between the thickness of the primary lesion and the likelihood of microscopic nodal involvement in individuals with clinically normal nodes.

Melanoma prognosis also worsens with the histologic findings of ulceration, high tumor cell mitotic rate, sparse lymphocytic host response, vascular invasion, and histologic signs of tumor regression (17, 20). Increasing age, male sex, and tumor location on the trunk, head, or neck also worsen prognosis. The expression of the cellular marker and melanocyte-specific protein, melastatin, in melanoma cells appears to be inversely proportional to metastasis and was correlated with prolonged disease-free survival in a study of 150 patients with localized disease (21). The presence of tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes in the VGP of primary melanomas correlates with decreased recurrence and reduced mortality (20, 22). Tumor immunity (host immune response to a tumor) has potential to be exploited for therapeutic use (23, 24).

Once metastasis to lymph nodes occurs, the 5-year survival ranges from 13% to 69%, depending on the number of lymph nodes affected and tumor burden (17). With visceral metastasis, the 5-year survival drops to approximately 6%, and the median survival from time of diagnosis is 7.5 months (25). The management of patients with clinically normal lymph nodes remains controversial. Elective node dissection has been replaced by sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB). In this method, lymphatic mapping is done to find the primary (or sentinel) draining lymph node or nodes, and histologic analysis is performed to assist with determining prognosis and staging. Currently, SLNB remains a diagnostic procedure, as it is unclear whether SLNB improves survival. SLNB’s impact on survival is the subject of a large, randomized study, the Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial (26). Unfortunately, there are no treatment options currently available that have been shown to increase life expectancy once melanoma spreads to regions beyond which it can be cured by local surgical excision.

Because there is no effective therapy for widely metastatic melanoma, the general public and primary care physicians must be aware of the classic clinical signs of melanoma in order to reduce mortality by detecting the disease in the early stages. These signs include change in color, recent enlargement, nodularity, irregular borders, and bleeding. Cardinal signs of melanoma are sometimes referred to by the mnemonic ABCDEs (asymmetry, border irregularity, color, diameter, elevation).

Histologic diagnosis of melanoma depends on a combination of certain characteristic architectural features and cellular atypia (reviewed in ref. 27). The discovery of histologic markers unique to melanocytes or melanoma, such as differentiation antigen melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1 (MART-1), also known as Melan-A, and human melanoma, black-45 (HMB-45), has aided melanoma diagnosis, but there is no marker that is 100% specific or sensitive (28, 29). Thus, fulfillment of histopathologic criteria (reviewed in ref. 4), combined with multiple positive histologic markers, provides the most reliable method of diagnosis.

Cancers such as melanoma arise due to accumulation of mutations in genes critical for cell proliferation, differentiation, and cell death (30). In addition, cancer cells acquire the ability to initiate and sustain angiogenesis, invade across tissue planes, and metastasize. The clinical and histologic progression observed in the growth phases of melanoma (Figure 1) is hypothesized to correspond to the accumulation of these genetic mutations (14). In order to develop treatments for advanced disease and to increase survival from metastatic melanoma, it is critical to understand the genetic changes leading to each progressive step of the cancer, especially the transition from RGP to VGP. Furthermore, an understanding of the changes that permit invasion through the epidermal basement membrane and thus allow for subsequent metastasis will permit the rational design of treatments for early stages of melanoma and potentially the design of chemopreventive treatments for patients with premalignant lesions or who are at high risk for melanoma development. In addition, an understanding of tumor biology and immunology will aid in the rational design of biochemotherapy and immunotherapy agents for more advanced stages of disease. Mutations observed in human melanoma patients provide starting points for a genetic analysis of melanoma.

Identification of melanoma-associated genes from patient samples

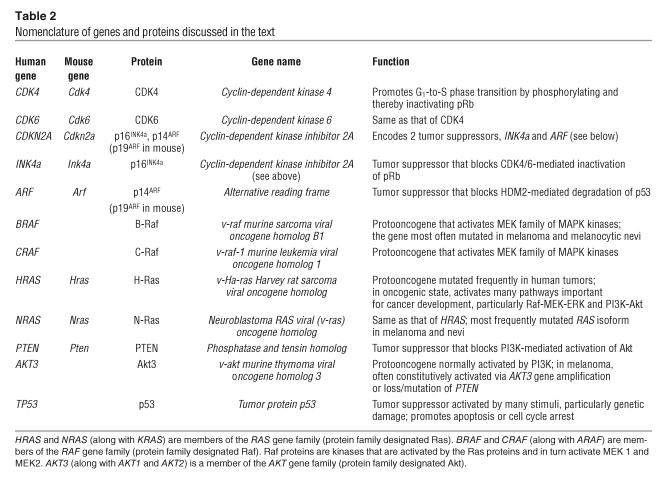

Much of our knowledge of melanoma susceptibility loci derives from genetic studies of melanoma-prone families. Although these families are rare, they have proven invaluable in the identification of genetic pathways that play roles in the development of familial as well as sporadic melanoma (31). See Table 2 for the symbols and definitions of melanoma-associated genes described herein.

Table 2.

Nomenclature of genes and proteins discussed in the text

Tumor suppressor pathways.

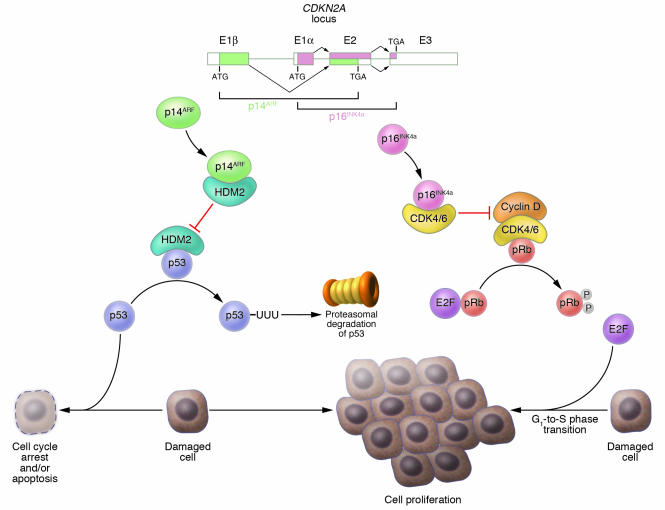

Melanoma development has been shown to be strongly associated with inactivation of the p16INK4a/cyclin dependent kinases 4 and 6/retinoblastoma protein (p16INK4a/CDK4,6/pRb) and p14ARF/human double minute 2/p53 (p14ARF/HMD2/p53) tumor suppressor pathways. These pathways help control the G1 phase of the cell cycle and are most often inhibited via deletions or mutations in the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A) locus on chromosome 9p21 (32, 33). This locus encodes 2 tumor suppressors, p16INK4a and p14ARF, via alternative reading frames (34) (Figure 2). p16INK4a sequesters CDK4 and CDK6 and thereby blocks phosphorylation of pRb by these kinases, keeping pRb in its active state inhibiting cell-cycle progression (35). p14ARF, on the other hand, stabilizes p53 by preventing HMD2-mediated degradation of the otherwise transiently expressed p53 protein (36–39) (Figure 2). Germline CDKN2A mutations were identified in 25–50% of familial melanoma kindreds (40–42). The importance of this locus in melanoma susceptibility was confirmed by studies showing that the penetrance of CDKN2A mutations significantly correlated with residence in a geographical location with a high population incidence rate of melanoma (43) and that CDKN2A mutation carriers have increased total nevus number and total nevus density — known risk factors for melanoma — compared with noncarriers within the same family (44). Inheritance of variants of the melanocortin-1 receptor gene seen in red-haired patients, along with CNKN2A mutations, further increases the risk of melanoma in melanoma-prone families (31, 45). Subsequent studies showed a similar frequency of somatic CDKN2A alterations in sporadic melanomas (e.g., refs. 46–49). Notably, melanoma-associated CDKN2A mutations and deletions may ablate only the INK4a transcript (42, 50), the ARF transcript (51, 52), or both (47–49, 53, 54), which indicates that each of these tumor suppressors plays an important individual role as a guardian against melanoma development. Less frequently, pRb may also be inactivated via CDK4 mutations — R24C or R24H — that occur in both sporadic and familial melanomas (55–58). These mutations prevent binding of p16INK4a to CDK4, rendering the kinase constitutively active. Although TP53 mutations are not universal in melanoma (59–61), several groups have reported a mutation frequency in the range of 10–25% (62–65), with at least 1 recent study (65) suggesting a correlation between TP53 mutation and poor prognosis.

Figure 2.

Genetic encoding and mechanism of action of tumor suppressors p16INK4a and p14ARF. The CDKN2A locus on chromosome 9p21 is composed of 4 exons (E) – 1α, 1β, 2, and 3 – and encodes 2 tumor suppressors, p16INK4a and p14ARF (termed p19ARF in the mouse), via alternative reading frames. p16INK4a is translated from the splice product of E1α, E2, and E3, while p14ARF is translated from the splice product of E1β, E2, and E3. Normally p16INK4a sequesters CDK4 and CDK6 thereby keeping pRb in an active hypophosphorylated state. In the absence of p16INK4a, CDK4 and CDK6 bind cyclin D and phosphorylate Rb. Phosphorylated pRb then releases the E2F transcription factor, which promotes the G1-to-S phase transition of the cell cycle. p14ARF, on the other hand, sequesters the p53-specific ubiquitin ligase HDM2. In the absence of p14ARF, HDM2 targets p53 for ubiquitination (UUU) and subsequent proteosomal degradation, and the loss of p53 impairs mechanisms that normally target genetically damaged cells for cell cycle arrest and/or apoptosis, which leads to proliferation of damaged cells. Loss of CDKN2A therefore contributes to tumorigenesis by disruption of both the pRb and p53 pathways. Figure modified with permission from N. Engl. J. Med. (S30).

Oncogenic Ras and its effectors.

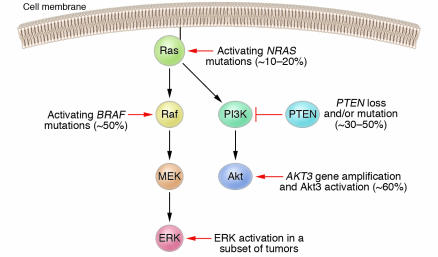

Melanoma-associated oncogene activation most often targets Ras and its canonical effector pathways, Raf-MAPK kinase-ERK (RAF-MEK-ERK) and PI3K-Akt (Figure 3). The mutation frequency of the RAS gene family, particularly NRAS, in human melanoma has been estimated in the majority of recent studies as 10–20% (65–69). A subset of melanomas has also been shown to harbor constitutive Ras activation without underlying mutations (70). Oncogenic Ras activates both the Raf and PI3K cascades. The importance of both of these pathways in melanoma development has been further confirmed by the identification of genetic alterations that activate each one independently.

Figure 3.

Schematic of the canonical Ras effector pathways Raf-MEK-ERK and PI3K-Akt and the mutations that most often activate these pathways in melanoma patients. Oncogenic NRAS mutations, found in approximately 10–20% of melanomas, activate both effector pathways. The Raf-MEK-ERK pathway may also be activated via mutations in the BRAF gene, found in approximately 50% of melanomas. In a subset of melanomas, the ERK kinases have been shown to be constitutively active even in the absence of NRAS or BRAF mutations. The PI3K-Akt pathway may be activated through loss or mutation of the inhibitory tumor suppressor gene PTEN, occurring in 30–50% of melanomas, or through gene amplification of the AKT3 isoform. While the exact frequency of AKT3 gene amplification is unknown, the Akt3 kinase is constitutively activated in approximately 60% of melanomas. Activation of ERK and/or Akt3 promotes the development of melanoma by various mechanisms, including stimulation of cell proliferation and enhanced resistance to apoptosis.

The first indication of involvement of the PI3K-Akt pathway in the progression of melanoma was the discovery of frequent loss of phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) in melanocytic lesions. PTEN is a protein and lipid phosphatase that inhibits Akt activation by PI3K (reviewed in ref. 71) (Figure 3). Loss of heterozygosity on regions of chromosome 10q, which harbors the PTEN locus, was demonstrated in 30–50% of malignant melanomas (72–74), and approximately 10% of melanomas were shown to have PTEN mutations (75–77). Interestingly, patients with disorders such as Cowden disease, which arise from inherited PTEN mutations and are characterized by the presence of benign hamartomatous tumors, are not widely reported to display an increased susceptibility to melanoma. More recently, 2 studies directly demonstrated that Akt is constitutively activated in more than 60% of melanomas, with higher frequencies of activation at later stages of the disease (78, 79). The latter study, by Stahl et al. (79), identified amplification of the AKT3 gene as an additional mechanism, distinct from PTEN loss, that may be responsible for these high frequencies of Akt activation.

The role of the Raf-MEK-ERK cascade in melanoma development has received a great deal of attention in the past 3 years, due to the identification of mutations in the BRAF gene in a high proportion of melanomas. The initial study by Davies et al. estimated that 67% of melanomas harbor BRAF mutations (66). By far the most frequent mutation is V599E; this mutation, found in the activation segment of the B-Raf kinase domain, renders the protein constitutively active and leads to elevated ERK1/2 activation. A great number of follow-up studies (e.g., refs. 67, 69, 80–83) have further examined the frequency of BRAF mutations in benign and malignant melanocytic lesions. The resulting estimates have varied from 30% to 70%, and taken together, the published data suggest that approximately 50% of melanomas carry the BRAFV599E mutation (84). B-Raf activation is thus one of the most frequent melanoma-associated genetic events, on par with activation of the PI3K-Akt pathway.

Several aspects of the association between BRAF mutation and melanoma bear further discussion. BRAF mutations are extremely rare in uveal (ocular) and mucosal melanomas (85, 86), which suggests that sun-related, UV-induced carcinogenesis may play a role in causing these mutations. Importantly, although approximately half of all melanomas carry the BRAFV599E mutation, this alteration is also found in 70–80% of common acquired melanocytic nevi (67, 83, 87). This finding strongly suggests that BRAF mutation is an early event in the development of melanocytic neoplasia and alone may not be sufficient to drive melanoma development. While all studies published to date have found a higher rate of BRAF mutations in nevi than in melanomas, contradictory findings have been reported concerning the frequencies of BRAF mutations at different stages of malignancy. Some groups have found BRAF mutations in a higher proportion of metastatic melanomas than early-stage primary melanomas (65, 81), but others have reported a decreasing mutation frequency in association with more advanced disease (67). Likewise, the presence of BRAF mutations in metastatic melanoma has been reported to correlate with a shorter survival in one study (88) and with a longer survival in another (89). Thus, the genetic evidence regarding the role of BRAF late in melanoma progression is currently inconclusive and merits further investigation. Finally, it is important to note that BRAF mutations may occur concurrently with loss or mutation of PTEN, but neither BRAF nor PTEN alterations are found together with NRAS mutations (65, 90, 91). Thus, melanomas that have arisen in the absence of NRAS mutations nearly always harbor activated BRAF, inactivating alterations of PTEN, or both. Conversely, tumors with oncogenic NRAS mutations typically retain wild-type BRAF and PTEN. These results reiterate the importance of both the PI3K-Akt and Raf-MEK-ERK cascades in melanoma development; they also suggest that each of these pathways plays a significant role in melanoma development and that, in a subset of melanomas, the 2 pathways may cooperate in promoting cancer progression.

Investigation of melanoma-associated mutations in experimental models

The functional importance of genes mutated in a high proportion of human melanomas has begun to be elucidated via studies in vitro and in mice. Initial experiments showed that mice carrying a deletion of the Cdkn2a locus have increased predisposition to tumor development (92). In subsequent studies designed to clarify the roles of the 2 genes encoded by this locus, mice with a selective knockout of the Arf gene (93, 94) or the Ink4a gene (95, 96) were generated and determined to be cancer prone. These findings directly showed that both Ink4a and Arf are important tumor suppressor genes, but in all of these studies, the knockout mice developed predominantly lymphomas and sarcomas, with very few spontaneous melanomas observed (92–96). However, when the Cdkn2a-null mice were engineered to express oncogenic HrasG12V from a melanocyte-specific promoter (Tyr-ras), more than 50% of these mice developed melanomas by the age of 6 months (97). In fact, while almost no Tyr-ras mice on a wild-type background developed melanomas (97), approximately half of the mice expressing Tyr-ras on either a selective Ink4a–/– or a selective Arf–/– background succumbed to the cancer by 1 year of age (33, 98). The formation of Ras-driven melanomas in Arf-null mice was accelerated by UV treatment, and the resulting tumors harbored Cdk6 amplification or loss of p16INK4a, which suggested that UV exposure promoted melanoma development by inactivating the pRb pathway (98). This series of studies suggested that the p16INK4a-pRb and p19ARF-p53 tumor suppressor pathways indeed serve as guardians against melanoma formation, and it also emphasized the importance of oncogenic Ras signaling in promoting the development of this cancer. HrasG12V, in fact, was shown to be essential not only for the initiation but also for the maintenance of the melanocytic tumors in this model (99), which confirmed its role as a driving oncogene of melanoma.

Functional demonstration of the role played by Akt activation, particularly occurring via loss of PTEN, in melanoma development at first proved elusive. Pten-knockout mice died at an early embryonic stage, and Pten+/– mice were highly predisposed to tumor formation and developed prostate, gastrointestinal, thyroid, and various other types of cancer, but melanomas were not observed among the spectrum of tumors in these mice (100, 101). However, when the Pten+/– mice were crossed into the Cdkn2a–/– background, approximately 10% of the resulting mice developed melanoma (102), which indicates that Pten loss, like Ras activation, can cooperate with inactivation of the p16INK4a-pRb and p19ARF-p53 pathways to induce melanocytic neoplasia. A separate line of investigation, in which human melanoma cell lines were used, showed that introduction of an intact chromosome 10 or a wild-type copy of PTEN into melanoma cells lacking PTEN expression inhibited in vitro growth of these cells (103) and in vivo tumor formation in immunodeficient mice (104) and that the introduced PTEN gene was targeted for loss of heterozygosity in these cells, both in vitro (103) and in vivo (104). Finally, specific inhibition of the AKT3 isoform in these cells, much like introduction of wild-type PTEN, stimulated apoptosis and retarded tumor growth (79). These experiments suggest involvement of the PI3K-Akt pathway in the development of melanoma.

To date, there have been no published transgenic murine studies on the role of B-Raf in melanoma development, but a number of experiments have been carried out with mouse and human cell lines. BRAFV599E has been shown to act as a transforming oncogene both in NIH3T3 cells (66) and in an immortalized murine melanocyte cell line (105). Furthermore, knockdown of B-Raf expression by small interfering RNA (siRNA) in human melanoma cell lines harboring the BRAFV599E mutation decreased the levels of MEK and ERK activation, inhibited cell proliferation, increased the rates of apoptosis, and blocked colony formation in soft agar (105–107). There was a specific correlation between the presence of the BRAF mutation and effects of the B-Raf knockdown on cell growth and cell death. For example, depletion of B-Raf expression in human fibrosarcoma cells carrying wild-type BRAF (106) or in melanoma cells containing an oncogenic HRAS mutation rather than an activating BRAF mutation (105) failed to block MEK-ERK signaling, inhibit cell proliferation, or promote apoptosis. Additionally, siRNA-mediated knockdown of C-Raf did not affect ERK activation, cell growth, or apoptosis in the cell lines carrying the BRAFV599E mutation (105–107). Finally, in the first preclinical study targeting the Raf-MEK-ERK pathway for small molecule–mediated inhibition in melanoma cells, the MEK inhibitor CI 1040 was shown to inhibit in vitro growth, soft agar colony formation, and Matrigel invasion of a human melanoma cell line bearing the BRAFV599E mutation; more importantly, it blocked the formation of pulmonary metastases and caused regression of established metastases when administered orally to immunodeficient mice injected intravenously with this cell line (108). These studies established that mutant B-Raf does have oncogenic properties, at least in a subset of melanomas, that it can serve as a potential therapeutic target (reviewed in ref. 109), and that small-molecule inhibition of the MAPK pathway is a viable therapeutic strategy.

Melanoma therapeutics

Surgical treatment of cutaneous melanoma employs specific surgical margins depending on the depth of invasion of the tumor. Specific surgical treatment guidelines of primary, nodal, and metastatic melanoma are beyond the scope of this article and are reviewed elsewhere (refs. 4, 110). Numerous agents have been used in the treatment of late-stage melanoma, but to date no single agent has significantly changed survival rates. Development of adjuvant therapies that increase survival beyond that achieved following surgery alone has been a long-standing goal of melanoma researchers and clinicians.

Chemotherapy.

Among traditional chemotherapeutic agents, only dacarbazine is FDA approved for the treatment of advanced melanoma (111). Combination chemotherapy regimens (such as cisplatin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine) are often employed, though no clinical trials have demonstrated a survival advantage for combination therapy over optimal single-agent therapy (111). Temozolomide is an oral alkylating agent approved for the treatment of malignant gliomas with activity comparable to that of dacarbazine in melanoma. While there is not yet supportive clinical trial data, temozolomide has been substituted in many combination regimens and is under investigation in combination with radiation therapy for patients with melanoma metastatic to the brain (112).

Immunotherapy.

A large, randomized multicenter study in high-risk melanoma patients performed by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) showed significant improvements in relapse-free and overall survival with postoperative adjuvant IFN-α-2b therapy, compared with standard observation (ECOG 1684) (4). The outcome of this study led to FDA approval of IFN-α-2b for treatment of melanoma. This study was performed on patients with deep primary tumors without lymph node involvement and node-positive melanomas. In other studies, little antitumor activity has been demonstrated in IFN-α-2b–treated metastatic stage IV melanoma. Furthermore, while a large follow-up study (Intergroup E1690) (4) confirmed relapse-free survival with high-dose IFN-α-2b, it did not show an increase in overall survival. Toxicities of high-dose IFN include constitutional (flu-like) symptoms and neuropsychiatric (depression, suicidal intention), hematologic, and hepatic effects (4). Other studies of low-dose IFN versus either observation or high-dose IFN have not shown a statistically significant increase in overall survival (summarized in ref. 4). Based on patient immune responses to a vaccine containing GM2, a ganglioside found predominantly in melanoma cells, a subsequent intergroup trial (ECOG 1694) was designed to compare high-dose IFN-α-2b with a GM2-containing vaccine administered with an immune-stimulating adjuvant (113). This trial was closed early, as interim analysis indicated significantly superior disease-free survival with IFN treatment. IL-2 has activity against melanoma, and high-dose therapy is FDA approved (114). Because high-dose IL-2 side-effects are significant and may be life threatening, IL-2 therapy requires inpatient management.

Biochemotherapies, which combine traditional chemotherapy with immunotherapies, such as IL-2 and IFN-α-2b, seemed promising in phase II trials, but phase III studies have not yet confirmed statistically significant survival benefits in patients with stage IV metastasis, and studies in resected, advanced stage III disease (Southwest Oncology Group/Intergroup trial S0008) are ongoing (reviewed in ref. 115). Seven large studies failed to show statistically significant increased overall survival rates for various biochemotherapy regimens (115).

Because most current adjuvant treatments have significant side effects and many have limited benefit with respect to overall survival in late-stage melanoma, there exists a strong need for the rational design of mechanism-based treatments for this devastating metastatic cancer, whose median survival rate with visceral metastases has not surpassed the 1-year barrier. Current approaches include inhibition of tumor-activated signaling cascades, exploiting the host cancer immune response, targeting of melanocyte and tumor-specific antigens and activities (such as blockade of angiogenesis and of proteins that resist apoptosis), and blockade of tumor growth and tumor-stroma interactions. Many treatment regimens are now in varying stages of development (from preclinical studies to phase II trials). This review will focus primarily on recent efforts to target the Ras cascade as an example of a rational approach to therapeutics.

Signal transduction inhibition by Raf inhibitor BAY 43-9006.

Small-molecule kinase inhibitors have potential as novel therapies for cancer and inflammatory conditions, as exemplified by currently marketed compounds imatinib mesylate (Gleevec; Novartis Pharmaceuticals) and gefitinib (Iressa; AstraZeneca) (116). BAY 43-9006 is a bis-aryl urea that was discovered in a screen for C-Raf inhibitors (117). Related urea compounds have been described as inhibitors of several other kinases (118). In addition to blocking C-Raf kinase activity with an IC50 of 3–12 nM (107, 117, 119), this compound inhibits both wild-type and mutant B-Raf, albeit less potently, with an IC50 of 16–28 nM for wild-type B-Raf and an IC50 of 29–47 nM for B-RafV599E (105, 107, 119). It is also able to inhibit several receptor tyrosine kinases involved in cancer progression, although the inhibition of these kinases is even less robust than that of the Raf proteins (119). In vitro studies showed that BAY 43-9006 is able to block ERK activation and cell proliferation in immortalized murine melanocytes transformed with either oncogenic RAS or BRAFV599E (105), as well as in several human melanoma cell lines carrying the BRAFV599E mutation (107). More importantly, oral administration of the drug to mice carrying tumor xenografts of one of these cell lines significantly retarded tumor growth (107). A recent study extended these findings to a panel of human tumor cell lines derived from several different cancer types and determined that orally administered BAY43-9006 had broad antitumor activity against xenografts formed from breast, colon, and lung cancer cell lines, with no adverse toxicity (119). These encouraging findings have led to the use of BAY 43-9006 in a number of clinical trials in patients with various solid tumors.

Initial phase I trials showed that BAY 43-9006 was well tolerated when administered either as a monotherapy (120) or in combination with traditional chemotherapy (121), with only mild adverse side effects observed. Phase II trials are ongoing, and to date BAY 43-9006 monotherapy has shown promise against several types of cancer, particularly renal cell carcinoma (122, 123). Unfortunately, in patients with advanced melanoma, clear evidence of the drug’s efficacy has yet to be demonstrated. After 12 weeks of treatment, fewer than 20% of patients had stable disease, and fewer than 5% had a partial response, with the vast majority of patients succumbing to progressive disease (123, 124). Phase II trials of BAY 43-9006 in combination with chemotherapy agents such as carboplatin and paclitaxel (125) are currently in progress. This combination regimen has shown some preliminary evidence of anticancer activity — of 35 patients in the initial trial, 11 had a partial response and 19 had stable disease (125).

There are several possible explanations for the rather modest therapeutic efficacy of BAY 43-9006 in melanoma patients. As a signal transduction inhibitor, this compound is predicted to act as a cytostatic agent (122), and it may need to be combined with one or more cytotoxic agents in order to exert significant antitumor activity. Alternatively, the inhibition of B-RafV599E activity by this drug may not be sufficiently potent. The progression of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) has been shown to involve CRAF alterations (S1) but not BRAF mutations (S2); a potentially important issue, given that BAY 43-9006 demonstrates 5- to 10-fold stronger inhibition of C-Raf than B-RafV599E. Taken together, these findings suggest that the greater therapeutic benefit enjoyed by RCC patients treated with BAY 43-9006, as compared with melanoma patients, may stem from more efficient inhibition of C-Raf or another target in RCC patients. Thus, when more specific and potent B-Raf inhibitors are developed, these compounds may show greater efficacy against melanoma. It is also possible that the cohort of melanoma patients treated with BAY 43-9006 did not have the proper mutation status to allow therapeutic benefit from the inhibitor. The drug has been shown to inhibit the growth of a human melanoma cell line carrying the BRAFV599E mutation (107) and several cell lines harboring oncogenic RAS (105, 119), although the latter result was demonstrated in transformed murine melanocytes (105) and in human cell lines derived from tumors other than melanoma (119) and has not been directly shown in human melanoma cells. It does not appear that all patients selected for the clinical trial of BAY 43-9006 carried the BRAFV599E mutation (123, 124). It is unclear whether patients whose melanomas harbor oncogenic RAS mutations rather than BRAF mutations would benefit from this drug, and therapeutic benefit is even less likely in patients whose tumors arose through other mechanisms, such as PTEN loss or AKT3 amplification. Efforts to classify the clinical trial participants by BRAF mutation status and correlate the mutation status with treatment outcome are currently underway (124, 125). Finally, B-Raf may not represent the ideal therapeutic target in patients with advanced melanoma. As discussed above, the high frequency of BRAF mutations in premalignant melanocytic lesions (67, 83, 87) suggests that the major effects of this oncogene may be limited to the initiation of melanoma development and that inhibition of B-Raf activity may have therapeutic benefit for patients with early-stage disease but not for those whose cancer has progressed to the metastatic stage. This theory is contradicted by data showing that melanoma cell lines carrying the BRAFV599E mutation depend on B-Raf expression for growth and survival (105–107), but the applicability of results from studies involving cell lines to actual patient tumors may be limited. More relevant experimental models of human melanoma may lead to more accurate preclinical assessments of potential therapeutic targets.

Angiogenesis inhibition and depletion of tumor nutrition.

In addition to signal transduction inhibition, several other rationally designed melanoma treatments are currently in clinical trials. In lieu of direct cytotoxic approaches, these therapies are aimed at starving the tumor by inhibiting angiogenesis or depleting nutrients essential for cancer growth. Of the antiangiogenic compounds, VEGFR inhibitors SU5416 and AG-013736 demonstrated broad-spectrum antitumor activity in mice bearing xenografts of human cancer cell lines originating from various tissues, including melanoma (S3, S4). Both compounds showed acceptable safety profiles in phase I trials (S5, S6) and progressed to phase II. Currently, no phase II data are available on AG-013736, while the efficacy of SU5416 against metastatic melanoma has proven disappointing. Of 26 evaluable patients in the trial, only 1 had a partial response and 1 had stable disease, with all patients eventually succumbing to melanoma after a median survival time of 29 weeks (S7). In preclinical studies, angiogenesis inhibitors that function by antagonizing integrin signaling, such as EMD 121974, have also demonstrated activity against human melanoma xenografts (S8). EMD 121974 had tolerable adverse effects in phase I trials (S9), but there is not yet available published data for phase II trials in melanoma. Angiogenesis inhibition is theoretically an attractive strategy for inhibition of tumor growth, but the efficacy of antiangiogenic agents against melanoma remains to be determined.

Melanoma cells, unlike normal human cells, require arginine for survival (S10). The arginine-degrading enzyme arginine deiminase (ADI), when formulated with polyethylene glycol (PEG) to make ADI-PEG, was shown to inhibit the growth of human melanoma xenografts in mice (S11). Initial phase I and II trials of ADI-PEG in melanoma patients demonstrated that the enzyme was well tolerated and had modest anticancer activity: of 41 patients in the trial, 6 had a partial response and 2 had stable disease (S12). ADI-PEG is currently in phase II trials (see www.clinicaltrials.gov). The results for ADI-PEG and the angiogenesis inhibitors, much like those for BAY 43-9006, highlight the difficulties in translating data from preclinical models into clinical efficacy. However, it is possible that the phase II trials of these agents that are currently in progress will show more evidence of antitumor activity and that future studies combining signal transduction inhibitors, angiogenesis inhibitors, and nutrient depleting enzymes with each other and/or with traditional chemotherapeutic agents will bring out the effectiveness of these novel agents.

Future directions

Melanoma is strongly associated with inactivation of the retinoblastoma (Rb) and p53 tumor suppressor pathways and activation of oncogenes in the Ras cascade. Gene therapy to directly replace lost and/or mutated tumor suppressors at physiologic levels and in the appropriate tissue context remains a technical challenge, but it is a potential long-range scientific goal in the treatment of melanoma. Small-molecule human double minute 2 (HDM2) antagonists have been developed and have potential to treat tumors with wild-type TP53 (S13). B-Raf and other Ras pathway effectors are potential therapeutic targets in melanoma, and more potent B-Raf–specific inhibitors may prove more effective than the general Raf inhibitor BAY 43-9006. There are efforts currently underway to target the PI3K Ras-effector pathway with small-molecule inhibitors (S14). In addition, secondary analyses of trials designed to evaluate the effects of statins on coronary disease suggest that these agents may also have potential chemopreventive effects in melanoma (S15). One proposed mechanism of action of statins in melanoma prevention is blockade of prenylation, which is required for Ras localization to the cell membrane (S16). Case-control studies and metaanalyses are ongoing to evaluate this preliminary observation.

In addition to kinase pathways, other molecules unique to melanoma or melanocytes are viable drug targets. Although results of initial efforts using peptide and whole-cell extracts to stimulate an immune response to cell surface proteins specific to melanoma, including GM2, were promising, large-scale studies have not revealed significant antitumor activity (S17). However, efforts to enhance host response to cellular vaccines by augmenting tumor immunity, with agents such as recombinant GM-CSF, may provide promising therapeutic agents (24). Since melanoma development is associated with telomerase activation (S18, S19), gene therapy approaches using anti-telomerase ribozymes (S20) and telomere homolog oligonucleotides (S21, S22) are currently in development for the treatment of melanoma and have shown antitumor activity in animal models. Targeting of pathways specific to melanocytes and critical to melanoma survival may also prove to be a viable therapeutic strategy, as suggested by recent preclinical data on the unique role of CDK2 in melanoma survival and CDK2 regulation by the microphthalmia-associated transcription factor in melanocytes (S23). Blockade of CDK2 suppressed growth and cell cycle progression in melanoma cell lines but not in other cancer cell lines.

Because early-stage melanoma is often curable by surgery, additional research efforts focus on blocking tumor-stroma and tumor-microvascular interactions that facilitate invasion and metastasis (S24, S25). Tumors such as melanoma often display resistance to apoptosis. Current efforts to inhibit the resistance of tumors to apoptosis target blockade of human B cell leukemia/lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2, an inhibitor of apoptosis) in melanoma (S26–S28). In addition to small-molecule inhibitors, vaccines, and gene therapies, humanized antibodies are a tantalizing therapeutic agent due to their low clinical safety profile. Also, because all melanomas may not have equal response to treatment modalities due to different mechanisms of tumorigenesis, the ability to perform complex genetic mutational analyses will allow for individually tailored patient prognoses and therapeutics (84). Finally, ongoing proteomics screens may identify other novel therapeutic targets in melanoma (S29).

Prevention should always be at the forefront of the fight to reduce melanoma. Protection from UV irradiation is the key preventive measure. In the final analysis, increased patient survival without a significant concurrent increase in morbidity remains a challenging treatment goal for metastatic melanoma. The design of rational therapeutics targeting key players in disease pathways tailored to tumor-specific mutations will certainly be the focus of translational cancer research in the coming years.

Note: References S1–S30 are available online with this article; doi:10.1172/JCI200524808DS1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the US Veteran’s Affairs Office of Research and Development. A.E. Adams is supported by a National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) NIH training grant (Harvard Department of Dermatology). Y. Chudnovsky is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute predoctoral fellow. We thank Susan Swetter for manuscript review and helpful suggestions and Uma Sundram and the Stanford Dermatology Department for melanoma histology slides.

Footnotes

Nonstandard abbreviations used: ADI, arginine deiminase; CDK, cyclin-dependent kinase; CDKN2A, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A; DNS, dysplastic nevus syndrome; MEK, MAPK kinase; PEG, polyethylene glycol; pRb, Rb protein; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog; Rb, retinoblastoma; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; RGP, radial growth phase; siRNA, small interfering RNA; SLNB, sentinel lymph node biopsy; VGP, vertical growth phase.

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Urteaga O, Pack GT. On the antiquity of melanoma. Cancer. 1966;19:607–610. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196605)19:5<607::aid-cncr2820190502>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laennec RTH. Sur les melanoses. Bulletin de Faculte de Medecine Paris. 1806;1:24. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Norris W. A case of fungoid disease. Edinb. Med. Surg. J. 1820;16:562–565. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nestle, M., and Carol, H. 2003. Melanoma. In Dermatology. J. Bolognia, J. Jorizzo, and R. Rapini, editors. Mosby. New York, New York, USA. 1789–1815.

- 5.Greenlee RT, Hill-Harmon MB, Murray T, Thun M. Cancer statistics, 2001. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2001;51:15–36. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.51.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinstock MA. Epidemiology, etiology, and control of melanoma. Med. Health R. I. 2001;84:234–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacKie RM, Freudenberger T, Aitchison TC. Personal risk-factor chart for cutaneous melanoma. Lancet. 1989;2:487–490. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)92097-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jhappan C, Noonan FP, Merlino G. Ultraviolet radiation and cutaneous malignant melanoma. Oncogene. 2003;22:3099–3112. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marks R. Epidemiology of melanoma. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2000;25:459–463. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2000.00693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilchrest B. Anti-sunshine vitamin A. Nat. Med. 1999;5:376–377. doi: 10.1038/7368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tucker MA, et al. Clinically recognized dysplastic nevi. A central risk factor for cutaneous melanoma. JAMA. 1997;277:1439–1444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chin L, Merlino G, DePinho RA. Malignant melanoma: modern black plague and genetic black box. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3467–3481. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.22.3467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haluska FG, Hodi FS. Molecular genetics of familial cutaneous melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 1998;16:670–682. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.2.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark WH, Jr, et al. A study of tumor progression: the precursor lesions of superficial spreading and nodular melanoma. Hum. Pathol. 1984;15:1147–1165. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(84)80310-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meier F, et al. Molecular events in melanoma development and progression. Front. Biosci. 1998;3:D1005–D1010. doi: 10.2741/a341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rusciano D. Differentiation and metastasis in melanoma. Crit. Rev. Oncog. 2000;11:147–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balch CM, et al. Final version of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system for cutaneous melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2001;19:3635–3648. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.16.3635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clark WH, Jr, From L, Bernardino EA, Mihm MC. The histogenesis and biologic behavior of primary human malignant melanomas of the skin. Cancer Res. 1969;29:705–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Breslow A. Prognostic factors in the treatment of cutaneous melanoma. J. Cutan. Pathol. 1979;6:208–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1979.tb01125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clark WH, Jr, et al. Model predicting survival in stage I melanoma based on tumor progression. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1989;81:1893–1904. doi: 10.1093/jnci/81.24.1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duncan LM, et al. Melastatin expression and prognosis in cutaneous malignant melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2001;19:568–576. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.2.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clemente CG, et al. Prognostic value of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in the vertical growth phase of primary cutaneous melanoma. Cancer. 1996;77:1303–1310. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960401)77:7<1303::AID-CNCR12>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramirez-Montagut T, Turk MJ, Wolchok JD, Guevara-Patino JA, Houghton AN. Immunity to melanoma: unraveling the relation of tumor immunity and autoimmunity. Oncogene. 2003;22:3180–3187. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dranoff G. GM-CSF-secreting melanoma vaccines. Oncogene. 2003;22:3188–3192. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barth A, Wanek LA, Morton DL. Prognostic factors in 1,521 melanoma patients with distant metastases. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 1995;181:193–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morton DL, et al. Validation of the accuracy of intraoperative lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy for early-stage melanoma: a multicenter trial. Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial Group. Ann. Surg. 1999;230:453–463; discussion 463–455. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199910000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weedon, D. 2002. Skin Pathology. 2nd edition. Churchill Livingstone. London, United Kingdom. 1100 pp.

- 28.Busam KJ, Jungbluth AA. Melan-A, a new melanocytic differentiation marker. Adv. Anat. Pathol. 1999;6:12–18. doi: 10.1097/00125480-199901000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gown AM, Vogel AM, Hoak D, Gough F, McNutt MA. Monoclonal antibodies specific for melanocytic tumors distinguish subpopulations of melanocytes. Am. J. Pathol. 1986;123:195–203. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayward NK. Genetics of melanoma predisposition. Oncogene. 2003;22:3053–3062. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chin L. The genetics of malignant melanoma: lessons from mouse and man. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2003;3:559–570. doi: 10.1038/nrc1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sharpless NE, Kannan K, Xu J, Bosenberg MW, Chin L. Both products of the mouse Ink4a/Arf locus suppress melanoma formation in vivo. Oncogene. 2003;22:5055–5059. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quelle DE, Zindy F, Ashmun RA, Sherr CJ. Alternative reading frames of the INK4a tumor suppressor gene encode two unrelated proteins capable of inducing cell cycle arrest. Cell. 1995;83:993–1000. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90214-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Serrano M, Hannon GJ, Beach D. A new regulatory motif in cell-cycle control causing specific inhibition of cyclin D/CDK4. Nature. 1993;366:704–707. doi: 10.1038/366704a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kamijo T, et al. Functional and physical interactions of the ARF tumor suppressor with p53 and Mdm2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:8292–8297. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pomerantz J, et al. The Ink4a tumor suppressor gene product, p19Arf, interacts with MDM2 and neutralizes MDM2’s inhibition of p53. Cell. 1998;92:713–723. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81400-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stott FJ, et al. The alternative product from the human CDKN2A locus, p14(ARF), participates in a regulatory feedback loop with p53 and MDM2. EMBO J. 1998;17:5001–5014. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.17.5001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang Y, Xiong Y, Yarbrough WG. ARF promotes MDM2 degradation and stabilizes p53: ARF-INK4a locus deletion impairs both the Rb and p53 tumor suppression pathways. Cell. 1998;92:725–734. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81401-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hussussian CJ, et al. Germline p16 mutations in familial melanoma. Nat. Genet. 1994;8:15–21. doi: 10.1038/ng0994-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kamb A, et al. Analysis of the p16 gene (CDKN2) as a candidate for the chromosome 9p melanoma susceptibility locus. Nat. Genet. 1994;8:23–26. doi: 10.1038/ng0994-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gruis NA, et al. Homozygotes for CDKN2 (p16) germline mutation in Dutch familial melanoma kindreds. Nat. Genet. 1995;10:351–353. doi: 10.1038/ng0795-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bishop DT, et al. Geographical variation in the penetrance of CDKN2A mutations for melanoma. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2002;94:894–903. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.12.894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Florell SR, et al. Longitudinal assessment of the nevus phenotype in a melanoma kindred. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2004;123:576–582. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Box NF, et al. MC1R genotype modifies risk of melanoma in families segregating CDKN2A mutations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001;69:765–773. doi: 10.1086/323412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Flores JF, et al. Loss of the p16INK4a and p15INK4b genes, as well as neighboring 9p21 markers, in sporadic melanoma. Cancer Res. 1996;56:5023–5032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kumar R, Smeds J, Lundh Rozell B, Hemminki K. Loss of heterozygosity at chromosome 9p21 (INK4-p14ARF locus): homozygous deletions and mutations in the p16 and p14ARF genes in sporadic primary melanomas. Melanoma Res. 1999;9:138–147. doi: 10.1097/00008390-199904000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fujimoto A, Morita R, Hatta N, Takehara K, Takata M. p16INK4a inactivation is not frequent in uncultured sporadic primary cutaneous melanoma. Oncogene. 1999;18:2527–2532. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cachia AR, Indsto JO, McLaren KM, Mann GJ, Arends MJ. CDKN2A mutation and deletion status in thin and thick primary melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2000;6:3511–3515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brookes S, et al. INK4a-deficient human diploid fibroblasts are resistant to RAS-induced senescence. EMBO J. 2002;21:2936–2945. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Randerson-Moor JA, et al. A germline deletion of p14(ARF) but not CDKN2A in a melanoma-neural system tumour syndrome family. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:55–62. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rizos H, et al. A melanoma-associated germline mutation in exon 1beta inactivates p14ARF. Oncogene. 2001;20:5543–5547. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bahuau M, et al. Germ-line deletion involving the INK4 locus in familial proneness to melanoma and nervous system tumors. Cancer Res. 1998;58:2298–2303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Petronzelli F, et al. CDKN2A germline splicing mutation affecting both p16(ink4) and p14(arf) RNA processing in a melanoma/neurofibroma kindred. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2001;31:398–401. doi: 10.1002/gcc.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wolfel T, et al. A p16INK4a-insensitive CDK4 mutant targeted by cytolytic T lymphocytes in a human melanoma. Science. 1995;269:1281–1284. doi: 10.1126/science.7652577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zuo L, et al. Germline mutations in the p16INK4a binding domain of CDK4 in familial melanoma. Nat. Genet. 1996;12:97–99. doi: 10.1038/ng0196-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Soufir N, et al. Prevalence of p16 and CDK4 germline mutations in 48 melanoma-prone families in France. The French Familial Melanoma Study Group. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1998;7:209–216. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tsao H, Benoit E, Sober AJ, Thiele C, Haluska FG. Novel mutations in the p16/CDKN2A binding region of the cyclin-dependent kinase-4 gene. Cancer Res. 1998;58:109–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Castresana JS, et al. Lack of allelic deletion and point mutation as mechanisms of p53 activation in human malignant melanoma. Int. J. Cancer. 1993;55:562–565. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910550407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lubbe J, Reichel M, Burg G, Kleihues P. Absence of p53 gene mutations in cutaneous melanoma. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1994;102:819–821. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12381544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Papp T, Jafari M, Schiffmann D. Lack of p53 mutations and loss of heterozygosity in non-cultured human melanocytic lesions. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 1996;122:541–548. doi: 10.1007/BF01213550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Albino AP, et al. Mutation and expression of the p53 gene in human malignant melanoma. Melanoma Res. 1994;4:35–45. doi: 10.1097/00008390-199402000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sparrow LE, Soong R, Dawkins HJ, Iacopetta BJ, Heenan PJ. p53 gene mutation and expression in naevi and melanomas. Melanoma Res. 1995;5:93–100. doi: 10.1097/00008390-199504000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zerp SF, van Elsas A, Peltenburg LT, Schrier PI. p53 mutations in human cutaneous melanoma correlate with sun exposure but are not always involved in melanomagenesis. Br. J. Cancer. 1999;79:921–926. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Daniotti M, et al. BRAF alterations are associated with complex mutational profiles in malignant melanoma. Oncogene. 2004;23:5968–5977. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Davies H, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002;417:949–954. doi: 10.1038/nature00766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pollock PM, et al. High frequency of BRAF mutations in nevi. Nat. Genet. 2003;33:19–20. doi: 10.1038/ng1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Demunter A, Stas M, Degreef H, De Wolf-Peeters C, van den Oord JJ. Analysis of N- and K-ras mutations in the distinctive tumor progression phases of melanoma. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2001;117:1483–1489. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gorden A, et al. Analysis of BRAF and N-RAS mutations in metastatic melanoma tissues. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3955–3957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Satyamoorthy K, et al. Constitutive mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in melanoma is mediated by both BRAF mutations and autocrine growth factor stimulation. Cancer Res. 2003;63:756–759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wu H, Goel V, Haluska FG. PTEN signaling pathways in melanoma. Oncogene. 2003;22:3113–3122. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Isshiki K, Elder DE, Guerry D, Linnenbach AJ. Chromosome 10 allelic loss in malignant melanoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1993;8:178–184. doi: 10.1002/gcc.2870080307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Herbst RA, Weiss J, Ehnis A, Cavenee WK, Arden KC. Loss of heterozygosity for 10q22-10qter in malignant melanoma progression. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3111–3114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Healy E, Rehman I, Angus B, Rees JL. Loss of heterozygosity in sporadic primary cutaneous melanoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1995;12:152–156. doi: 10.1002/gcc.2870120211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Guldberg P, et al. Disruption of the MMAC1/PTEN gene by deletion or mutation is a frequent event in malignant melanoma. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3660–3663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Teng DH, et al. MMAC1/PTEN mutations in primary tumor specimens and tumor cell lines. Cancer Res. 1997;57:5221–5225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tsao H, Zhang X, Benoit E, Haluska FG. Identification of PTEN/MMAC1 alterations in uncultured melanomas and melanoma cell lines. Oncogene. 1998;16:3397–3402. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dhawan P, Singh AB, Ellis DL, Richmond A. Constitutive activation of Akt/protein kinase B in melanoma leads to up-regulation of nuclear factor-kappaB and tumor progression. Cancer Res. 2002;62:7335–7342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Stahl JM, et al. Deregulated Akt3 activity promotes development of malignant melanoma. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7002–7010. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Brose MS, et al. BRAF and RAS mutations in human lung cancer and melanoma. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6997–7000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dong J, et al. BRAF oncogenic mutations correlate with progression rather than initiation of human melanoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3883–3885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Uribe P, Wistuba II, Gonzalez S. BRAF mutation: a frequent event in benign, atypical, and malignant melanocytic lesions of the skin. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2003;25:365–370. doi: 10.1097/00000372-200310000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yazdi AS, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in benign and malignant melanocytic lesions. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2003;121:1160–1162. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rodolfo M, Daniotti M, Vallacchi V. Genetic progression of metastatic melanoma. Cancer Lett. 2004;214:133–147. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cohen Y, et al. Lack of BRAF mutation in primary uveal melanoma. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2003;44:2876–2878. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Edwards RH, et al. Absence of BRAF mutations in UV-protected mucosal melanomas. J. Med. Genet. 2004;41:270–272. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.016667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kumar R, Angelini S, Snellman E, Hemminki K. BRAF mutations are common somatic events in melanocytic nevi. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2004;122:342–348. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202X.2004.22225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Houben R, et al. Constitutive activation of the Ras-Raf signaling pathway in metastatic melanoma is associated with poor prognosis [abstract] J. Carcinog. 2004;3:6. doi: 10.1186/1477-3163-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kumar R, et al. BRAF mutations in metastatic melanoma: a possible association with clinical outcome. Clin. Cancer Res. 2003;9:3362–3368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tsao H, Zhang X, Fowlkes K, Haluska FG. Relative reciprocity of NRAS and PTEN/MMAC1 alterations in cutaneous melanoma cell lines. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1800–1804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tsao H, Goel V, Wu H, Yang G, Haluska FG. Genetic interaction between NRAS and BRAF mutations and PTEN/MMAC1 inactivation in melanoma. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2004;122:337–341. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202X.2004.22243.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Serrano M, et al. Role of the INK4a locus in tumor suppression and cell mortality. Cell. 1996;85:27–37. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kamijo T, et al. Tumor suppression at the mouse INK4a locus mediated by the alternative reading frame product p19ARF. Cell. 1997;91:649–659. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80452-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kamijo T, Bodner S, van de Kamp E, Randle DH, Sherr CJ. Tumor spectrum in ARF-deficient mice. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2217–2222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Krimpenfort P, Quon KC, Mooi WJ, Loonstra A, Berns A. Loss of p16Ink4a confers susceptibility to metastatic melanoma in mice. Nature. 2001;413:83–86. doi: 10.1038/35092584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sharpless NE, et al. Loss of p16Ink4a with retention of p19Arf predisposes mice to tumorigenesis. Nature. 2001;413:86–91. doi: 10.1038/35092592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chin L, et al. Cooperative effects of INK4a and ras in melanoma susceptibility in vivo. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2822–2834. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.21.2822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kannan K, et al. Components of the Rb pathway are critical targets of UV mutagenesis in a murine melanoma model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:1221–1225. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0336397100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chin L, et al. Essential role for oncogenic Ras in tumour maintenance. Nature. 1999;400:468–472. doi: 10.1038/22788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Di Cristofano A, Pesce B, Cordon-Cardo C, Pandolfi PP. Pten is essential for embryonic development and tumour suppression. Nat. Genet. 1998;19:348–355. doi: 10.1038/1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Podsypanina K, et al. Mutation of Pten/Mmac1 in mice causes neoplasia in multiple organ systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:1563–1568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.You MJ, et al. Genetic analysis of Pten and Ink4a/Arf interactions in the suppression of tumorigenesis in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:1455–1460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022632099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Robertson GP, et al. In vitro loss of heterozygosity targets the PTEN/MMAC1 gene in melanoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:9418–9423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Stahl JM, et al. Loss of PTEN promotes tumor development in malignant melanoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2881–2890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wellbrock C, et al. V599EB-RAF is an oncogene in melanocytes. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2338–2342. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hingorani SR, Jacobetz MA, Robertson GP, Herlyn M, Tuveson DA. Suppression of BRAF(V599E) in human melanoma abrogates transformation. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5198–5202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Karasarides M, et al. B-RAF is a therapeutic target in melanoma. Oncogene. 2004;23:6292–6298. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Collisson EA, De A, Suzuki H, Gambhir SS, Kolodney MS. Treatment of metastatic melanoma with an orally available inhibitor of the Ras-Raf-MAPK cascade. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5669–5673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Tuveson DA, Weber BL, Herlyn M. BRAF as a potential therapeutic target in melanoma and other malignancies. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:95–98. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00189-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Balch CM, et al. Long-term results of a multi-institutional randomized trial comparing prognostic factors and surgical results for intermediate thickness melanomas (1.0 to 4.0 mm). Intergroup Melanoma Surgical Trial. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2000;7:87–97. doi: 10.1007/s10434-000-0087-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Eggermont AM, Kirkwood JM. Re-evaluating the role of dacarbazine in metastatic melanoma: what have we learned in 30 years? Eur. J. Cancer. 2004;40:1825–1836. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Douglas JG, Margolin K. The treatment of brain metastases from malignant melanoma. Semin. Oncol. 2002;29:518–524. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2002.35247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kirkwood JM, et al. High-dose interferon alfa-2b significantly prolongs relapse-free and overall survival compared with the GM2-KLH/QS-21 vaccine in patients with resected stage IIB-III melanoma: results of intergroup trial E1694/S9512/C509801. J. Clin. Oncol. 2001;19:2370–2380. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.9.2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Agarwala S. Improving survival in patients with high-risk and metastatic melanoma: immunotherapy leads the way. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2003;4:333–346. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200304050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Margolin KA. Biochemotherapy for melanoma: rational therapeutics in the search for weapons of melanoma destruction. Cancer. 2004;101:435–438. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Dumas J, Smith RA, Lowinger TB. Recent developments in the discovery of protein kinase inhibitors from the urea class. Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Devel. 2004;7:600–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Lyons JF, Wilhelm S, Hibner B, Bollag G. Discovery of a novel Raf kinase inhibitor. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 2001;8:219–225. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0080219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Dumas J. Protein kinase inhibitors from the urea class. Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Devel. 2002;5:718–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Wilhelm SM, et al. BAY 43-9006 exhibits broad spectrum oral antitumor activity and targets the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway and receptor tyrosine kinases involved in tumor progression and angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7099–7109. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Strumberg D, et al. Results of phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies of the Raf kinase inhibitor BAY 43-9006 in patients with solid tumors. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2002;40:580–581. doi: 10.5414/cpp40580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Richly H, et al. A phase I clinical and pharmacokinetic study of the Raf kinase inhibitor (RKI) BAY 43-9006 administered in combination with doxorubicin in patients with solid tumors. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2003;41:620–621. doi: 10.5414/cpp41620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Ahmad T, Eisen T. Kinase inhibition with BAY 43-9006 in renal cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004;10:6388–6392. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-040028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Ratain MJ, et al. Preliminary antitumor activity of BAY 43-9006 in metastatic renal cell carcinoma and other advanced refractory solid tumors in a phase II randomized discontinuation trial (RDT) [abstract]. ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings. June 5–8, 2004. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004;22(Suppl.):4501. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Ahmad T, et al. BAY 43-9006 in patients with advanced melanoma: The Royal Marsden Experience [abstract]. 2004 ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings. June 5–8, 2004. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004;22(Suppl.):7506. [Google Scholar]

- 125.Flaherty KT, et al. Phase I/II trial of BAY 43-9006, carboplatin (C) and paclitaxel (P) demonstrates preliminary antitumor activity in the expansion cohort of patients with metastatic melanoma [abstract]. 2004 ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings. June 5–8, 2004. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004;22(Suppl.):7507. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.