Abstract

This article reviews progress in primary care reforms in the four Central Asian countries Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. It draws on the country monitoring work of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, a review of the peer-reviewed literature and an analysis of data available in international databases. The retrieved information was organized according to key health system functions (governance, provision, financing and resource generation), as well as key aims of universal health coverage (access to and quality of primary care and financial protection). The article finds that the four countries have made substantial reforms in all of these areas, but that there is still some way to go towards universal health coverage. Key challenges are the overall lack of public funding for primary care, poor financial protection due to prescribed outpatient medications being generally outside of publicly funded benefits packages, the low status and salary of primary care workers, problems of access to primary care in rural areas, and underdeveloped quality monitoring and improvement systems.

1. Introduction

Since becoming independent from the Soviet Union in 1991, the countries of Central Asia have undergone substantial health system reforms. One of the centre planks of reforms was strengthening primary care. Indeed, it was in Central Asia that the famous Primary Health Care Declaration of Alma Alta (now Almaty) was adopted in 1978 [1]. The declaration defined primary health care as the cornerstone for achieving “health for all” by 2000. While the principles of primary health care as set out in Alma Ata encompassed social determinants and social justice, equity and community participation, as well as universal access and equitable coverage [2], the focus of global health policy has since shifted to the more narrow concept of “universal health coverage”, which has been later included in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [3].

Universal health coverage (UHC) is a global public health priority promoted by the World Health Organization (WHO), the World Bank and the United Nations. It is defined by WHO as “ensuring that all people have access to needed health services (including prevention, promotion, treatment, rehabilitation and palliation) of sufficient quality to be effective while also ensuring that the use of these services does not expose the user the financial hardship” [4]. UHC has therefore three main goals: equity in access, sufficient quality, and financial protection from the costs of using health services [5]. SDG target 3.8 defines this as “Achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health-care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all”, with the two related indicators 3.8.1 “Coverage of essential of health services” and 3.8.2 “Proportion of population with large household expenditures on health as a share of total household expenditure or income” [6]. Access to and quality of health services are intermediate health system objectives that are key to universal health coverage. They contribute to final health system goals, most importantly health improvement, but also financial protection and people-centredness [7].

According to WHO, progress towards universal health coverage requires a considerable strengthening of primary care systems, particularly in lower income settings [8]. This also applies to the Central Asian countries, but they face several challenges to delivering this in practice. One of these challenges is the available fiscal space. While Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan are classified by the World Bank as lower-middle-income countries (and Kazakhstan as upper-middle-income country), Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan have a far lower GDP per capita than their comparatively richer neighbours Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan with their large fossil fuel industries (Table 1).

Table 1.

Key demographic, economic and health system indicators, 2021 or latest available year.

| Kazakhstan | Kyrgyzstan | Tajikistan | Uzbekistan | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population total (in million) | 19.0 | 6.7 | 9.8 | 34.9 |

| Rural population (% of total) | 42.2 | 62.9 | 72.3 | 49.6 |

| GDP per capita (PPP, current international US$) | 28,685 | 5,290 | 4,288 | 8,497 |

| Life expectancy at birth (years)* | 71.4 | 71.8 | 70.0 | 70.3 |

| Health expenditure per capita (current international US$)* | 342 | 64 | 70 | 121 |

| Out-of-pocket expenditure as % of current health expenditure* | 27.5 | 45.9 | 65.2 | 53.1 |

Sources: World Bank (2023) World Development Indicators; WHO (2023) Global Health Expenditure database.

Note: *2020 data.

In addition, ensuring geographical access to primary care is a challenge in all of the Central Asian countries due to topography: large deserts (Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan), sparsely populated areas, and highly mountainous areas (Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan). Furthermore, more than half of the population lives in rural areas in Tajikistan (72.3 %) and Kyrgyzstan (62.9 %) and almost half of the population (49.6 %) does so in Uzbekistan, compared to 30.6 % in the European Union (EU), which exacerbates barriers to health care access.

This article provides an overview of key changes to primary care in the region in the last three decades and examines how far the countries are on the path towards universal health coverage, an aspect that has received insufficient attention in the literature on the region so far. It also adds to the very few comparative analyses of health reforms in Central Asia and the former Soviet countries. The focus is on the four Central Asian countries with publicly available information on health system reforms and achievements: Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. We do not consider Turkmenistan here, as there is a lack of reliable information on the issues examined.

2. Materials and methods

This article draws on the country monitoring work of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. This includes Health Systems in Transition (HiT) health system reviews, health system summaries, and Health Systems in Action Insights. All these products are based on common templates to ensure the comparable description and analysis of health systems and policies [9]. They are prepared by national experts and Observatory staff, with input from Ministries of Health and WHO Country Offices, and peer-reviewed. Authors draw on multiple data sources for the compilation of these documents, ranging from national statistics, national policy documents to published literature. Quality assurance is performed by the series editors and external reviewers, and Ministries of Health are given the chance to correct factual errors.

We complemented the information retrieved with an updated search of titles/abstracts in PubMed/Medline, using the search terms ‘‘Central Asia’’, ‘‘Kazakhstan’’, ‘‘Kyrgyzstan’’, ‘‘Tajikistan’’ and ‘‘Uzbekistan’’, in combination with ‘‘primary care’’ and ‘‘primary health care”. We also searched international databases (the Global Health Expenditure database from WHO, the European Health Information Gateway from the WHO Regional Office for Europe, and the World Development Indicators database from the World Bank) for the latest internationally comparable information on primary care in the four countries. The documents and databases were reviewed by the lead author and the retrieved content checked for accuracy by all co-authors.

Information and data from the Observatory work, the retrieved literature, and international databases were organized using pre-defined themes. These themes included the four key health system functions (governance, health care provision, financing and resource generation) and the three main goals of universal health coverage (access to and quality of care, and financial protection). In terms of health system functions, we follow the World Health Report 2000 [10] and the most recent WHO framework for health system performance assessment [7]. In terms of the three main goals of UHC we follow the United Nations [5].

One of the challenges in undertaking a comparative analysis of primary care reforms in Central Asia is that, despite using the latest available literature and data sources, there are large gaps in up-to-date comparative evidence with regard to almost all of the areas considered here. Another challenge is that the countries themselves do not have a uniform understanding of what constitutes primary care. The definition of primary care used in Kazakhstan is very broad, even including day care at hospitals [11]. A similarly broad definition of primary care also exists in Uzbekistan, where it encompasses district and urban hospitals. These definitional differences undermine the comparability of nationally reported data, such as on primary care financing.

3. Results

3.1. Health system functions

3.1.1. Governance

All four countries initiated major health reforms in the past three decades and primary care was often at the centre of national reform programmes. Reforms were undertaken with the involvement of external agencies such as the World Bank, WHO and bilateral donors. The explicit or implicit goals of primary care reforms in the region were to increase efficiency and effectiveness, improve access to services and financial protection, and improve the quality of services. All four countries have signed up to the SDGs, including the goal of UHC.

Key dimensions of health system governance are transparency, accountability and population participation and involvement [12]. All three dimensions are underdeveloped in the four Central Asian countries considered here, although with some differences across countries. Key challenges to transparency and accountability are widespread informal payments, in particular in Tajikistan [13] (see below), and other forms of corruption, in particular in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan [14]. Some efforts are being made to address these issues, but progress is slow. In all four countries, public participation and involvement in health policy making is still at an early stage of development.

3.1.2. Provision

The primary care system inherited from the Soviet period was extensive and fragmented, and all countries of the region inherited an oversized hospital sector. In the transitional recession that followed independence, it became clear that the healthcare infrastructure would need to undergo changes to become more sustainable [15].

In urban areas, in the Soviet period there were separate polyclinics for adults, children and women’s reproductive health, as well as oblast-level polyclinics, dental polyclinics and family planning polyclinics. All four countries have simplified this structure, merging the previously separate polyclinics for adults, children, and women's reproductive health. In Kyrgyzstan, these were then renamed Family Group Practices, with specialized outpatient care provided by Family Medicine Centres. This means that solo practices of general practitioners (GPs) were never an issue (at least in urban areas), in contrast to many countries in Western Europe [16]. Patients are registered with the polyclinic in whose catchment area they live. They can choose to go to a different provider, but at least in Kyrgyzstan [17], they would then not be entitled to publicly covered services.

There were some reforms to primary care provision in rural areas, although Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan have essentially retained the traditional feldsher-midwifery posts as the basic layer of rural primary care (Table 2), rechristened ‘Health Houses’ in Tajikistan [18]. The functions of these posts remain similar for all three countries. In Kyrgyzstan, for example, the feldsher-midwifery posts serve small villages and remote areas with populations of 500–2000 people and are visited regularly by a family doctor. In contrast, Uzbekistan has changed its feldsher-midwifery posts into rural physician posts and these (as the name indicates) are staffed with physicians, although there are still some feldsher-midwifery posts in some remote areas.

Table 2.

Overview of public primary care provision in the four countries.

| Kazakhstan | Kyrgyzstan | Tajikistan | Uzbekistan | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural areas | ||||

| 1st level |

|

|

|

|

| 2nd level |

|

|

|

|

| Urban areas | ||||

| 1st level |

|

|

|

|

| 2nd level |

|

|||

Source: Authors’ compilation

There were also some changes to higher layers of primary care in rural areas. In Tajikistan, the formerly multi-layered provision of primary care in rural areas has been transformed into a two-tiered system, with Health Houses as the nominal gatekeepers to rural health centres (formerly rural physician clinics or rural hospitals) [19]. In Uzbekistan, primary care in rural areas now consists of rural family medicine physician points, family medicine polyclinics and district multi-specialty polyclinics [20]. Finally, in Kazakhstan primary care in rural areas is provided by rural physician ambulatories, feldsher-midwifery posts and health posts in small communities and district polyclinics in larger rural localities.

Investments were made to strengthen the material and technical base of primary care providers in both rural and urban areas. However, there is still some way to go, especially in rural areas. In Uzbekistan, for example, in a national self-assessment of water and sanitation services in 2020, only 57 % of primary health care facilities reported having basic water services, and only 26 % had basic sanitation services [21].

Another area of reforms concerned the management of facilities. While providers had traditionally very little decision-making autonomy and were tied to line-item budgets, Kazakhstan has started to increase provider autonomy to manage their budgets [11].

Despite attempts to strengthen the structure of primary care, a number of persistent functional challenges remain. In all four countries these include the limited skills and scope of practice of family doctors and nurses, low public confidence in primary care, weak gatekeeping, and a public preference for services offered by hospitals and narrow-profile specialists [17], [19], [21], [22]. These challenges can hinder efforts to improve the performance of primary care in practice. For example, whilst official co-payments for specialist outpatient care or inpatient care are higher without referral, patients in Tajikistan still frequently bypass lower levels of care and go directly to district, provincial or even national-level specialized facilities [18].

3.1.3. Financing

All four countries have adopted changes to their health financing systems that aim to increase the share of resources going to primary care and remove financial barriers to access. In Tajikistan, a basic benefits package introduced in pilot rayons has aimed to redirect resources to primary care and improve access for specific population groups, but implementation has been challenging and the package is currently being redesigned [23]. Kazakhstan aims to increase the share of health spending on primary care, outpatient specialized care and outpatient medicines to 60 % by 2025 [22] and has introduced incentives to shift cases from inpatient to day and ambulatory care [11].

The share of out-of-pocket payments is particularly high in Tajikistan, reaching 65.2 % of health spending in 2020, but also in the wealthier Uzbekistan, reaching 53.1 % in the same year [24]. In contrast, they amounted to 45.9 % in Kyrgyzstan and 27.5 % in Kazakhstan. While this ratio has fluctuated in all four countries over the last decades, in most years it was highest in Tajikistan, followed by Uzbekistan.

Outpatient pharmaceuticals are a major contributor to the burden of out-of-pocket payments. Indeed, the share of public resources devoted to pharmaceuticals is very small in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, amounting to only 1.9 % of current health expenditure in Kyrgyzstan in 2019, compared to 28.2 % of current health expenditure on pharmaceuticals coming from private (mostly out-of-pocket) spending [17]. The lack of public funding for pharmaceuticals is even more extreme in Tajikistan, where the 23.9 % of current health expenditure that was spent on pharmaceuticals in 2019 came entirely from private sources. In Tajikistan, prescribing drugs has been described as an important source of income for primary care providers, resulting in overprescribing and unnecessary medications, such as vitamin injections [25].

In Kazakhstan too public coverage of outpatient pharmaceuticals has been described as very poor [11] and the medicines prescribed by primary care doctors are usually paid for by the patient, with medicines only being provided free of charge to patients with “socially significant diseases” [11], [26]. In Uzbekistan outpatient pharmaceuticals are covered for vulnerable groups, but availability varies based on whether public funding is forthcoming. A list approved by the Ministry of Health of over 100 medications are prioritized for availability, of which over 30 are centrally procured. However, the medications, are, especially for chronic care, not available for continuous use [20]. Kyrgyzstan adopted the Additional Drug Package in 2001, aimed to improve access of the population to essential medicines, but the number of medicines covered by this programme and the basic benefits package is limited and out-of-pocket payments remain high [17]. To address the issue of high out-of-pocket payments for medicines, the Ministry of Health has been piloting a new government decree on the introduction of price controls for a selected list of medicines [17].

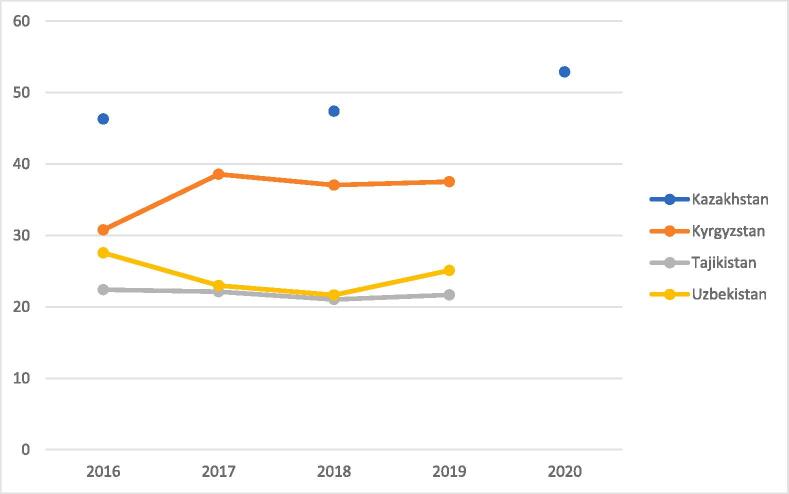

The fact that outpatient pharmaceuticals are generally excluded from benefit packages creates incentives for patients to visit emergency care or use ambulance care services, where medicines are officially provided free of charge. Lacking inclusion of outpatient pharmaceuticals in benefit packages is also reflected in the comparatively small share of public resources going to primary health care as defined by WHO in Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, amounting to only 22 % in Tajikistan and 25 % in Uzbekistan in 2019 (see Fig. 1). This compares to an unweighted average of 53 % for those countries in the WHO European Region for which there are data for 2020, ranging from 15 % in Armenia to 84 % in Denmark.

Fig. 1.

Domestic general government expenditure on primary health care as a share (%) of expenditure on primary health care. Source: [34]. Note: Primary health care expenditure includes general outpatient curative care, dental outpatient curative care, preventive care and health promotion activities, outpatient or home-based long-term health care, 80% of spending on medical goods, and 80% of spending on health system administration and governance. Data are missing for Kazakhstan for 2017 and 2019.

Another major change in the area of health financing has been the introduction of new provider payment mechanisms for primary care providers. Payment to providers in all former Soviet countries was initially based on “historical incrementalism”, which was based on the previous year’s budget and in which spending was tied to line-items, limiting managerial autonomy [15]. Almost all of these countries have now moved to a provider payment mechanism for primary care based on per capita financing [27].

In Central Asia, Kyrgyzstan was a forerunner of health financing reforms, introducing a mandatory health insurance fund in 1996, followed by the introduction of capitation payments for primary health care providers. In recent years, payment for results and quality of care has been piloted, under a system called Funding for Performance (F4P) for primary care [17]. However, the system, introduced in 2018, was abolished in 2021 and instead the basic salary of primary care workers increased by 100 %. In Uzbekistan, capitation-based payment for primary care has also been introduced, first in rural and then in urban areas [28]. Per capita payments are paid for the covered population, with adjustments for age and gender. Per capita rates are set annually at the viloyat (regional) level, depending on the size of the viloyat health budget. In Kazakhstan, a comprehensive reform of the system of service delivery initiated in 2009 has led to the harmonization of tariffs and payment methods across the country. Similar to Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, financing of primary care is now primarily through capitation, although this is complemented by a pay-for-performance system based on meeting pre-defined indicators [11]. In Tajikistan, partial capitation for primary care (covering unsecured line items) was rolled out in 2010, and whilst full capitation was formally introduced in 2019, in practice it has remained limited in per capita terms. Furthermore, in contrast to capitation financing of primary care in the other three Central Asian countries, public funding for primary care in Tajikistan is not centrally pooled and then distributed according to a common formula. This means that the allocation of public resources to primary care providers in Tajikistan continues to be based largely on inputs rather than outputs, which has been described by the World Bank as a major source of inefficiency [13].

Primary care workers in the public sector in the three countries excluding Kazakhstan are salaried government employees and levels of payment are below national salary averages. The low levels of remuneration and the low status afforded to primary care workers affect recruitment and retention (with many health workers, in particular from Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, moving to neighbouring countries in search for higher paid jobs), their performance and quality of work (due to lack of motivation and lacking rewards for good performance), and creates incentives for rent-seeking [11], [17], [25], [29]. In Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan the formal salaries for doctors in primary care are higher than for doctors in hospitals, but the latter can supplement their salaries to a greater degree with informal payments from patients [17]. While the prevalence of informal payments is by necessity difficult to ascertain, surveys point to persistently high levels, in particular in Tajikistan. In 2016, the joint World Bank/European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) Living in Transition Survey (LITS) found that 47 % (down from 55 % in 2010) of Tajik households that had used publicly provided health care over the previous 12 months reported making informal payments or gifts to providers—more than double the rate in neighbouring countries [13].

3.1.4. Resource generation

Overall, the four countries have comparatively few primary care physicians, as the focus remains on specialization. It is also worth noting that many primary care facilities still have paediatricians and obstetricians/gynaecologists among their staff in addition to GPs, and information on actual changes in care practices is limited.

However, the countries have undertaken substantial reforms to medical education, including for primary care physicians and nurses. The Soviet model of medical training, with specialization at undergraduate level and physicians trained in very limited areas (meaning a primary care facility might have a paediatrician, internist and obstetrician, all operating at a very basic level) is gradually being revised. Family medicine programmes have been established and physicians re-trained in family medicine. Again, Kyrgyzstan was at the forefront of reforms, being the first country in Central Asia to introduce the family medicine system in the late 1990 s by transforming polyclinics into Family Group Practices and retraining narrow-profile specialists into family doctors. By 2007, 98 % of doctors working in primary care had retrained in family medicine following a four-month curriculum [30]. Similarly, by 2004, 85 % of the county’s outpatient nurses had been re-trained to become family medicine nurses using a two-month curriculum [29]. However, the state medical education system has not been revised to train family doctors, resulting in a shortage of family doctors [17].

The other three countries have embarked on similar efforts. In Tajikistan, the nursing school curriculum has been revised and departments of family medicine established at the Tajik State Medical University and at several nursing education centres throughout the country [31]. By 2022, 82.3 % of doctors working in primary care in Tajikistan had received training in family medicine and the share of nurses working in primary care who had received training in family medicine stood at 73.4 % [32].

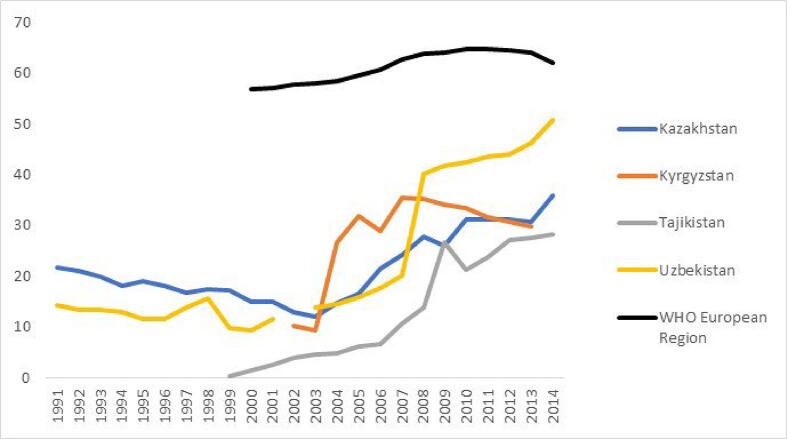

However, as a whole, comparatively few physicians are training in family medicine in the Central Asian countries, although up-to-date comparative data are unavailable. In 2014 (the latest year with comparable data) the number of general practitioners per 100 000 population was still far below the average of the WHO European Region although it has seen substantial increases in all four countries when compared to the early 2000s (Fig. 2). According to nationally available data, there were 33 family doctors per 100 000 population in Kyrgyzstan in 2021 [17], which matched the level achieved in 2010. Overall, family doctors accounted for 12 % of the total number of doctors in Kyrgyzstan in 2021, with the remaining 88 % being narrow-profile specialists [17]. By comparison, the lowest ratio of general medical practitioners per population in the EU in 2021 was in Greece, with 47 per 100 000 population [33].

Fig. 2.

Number of general practitioners (physical persons) per 100 000 population. Source: Global Health Expenditure database. Note: included in this category are general practitioners, district medical doctors, therapists, family medical practitioners (“family doctors”), and medical interns or residents specialising in general practice; excluded are paediatricians or other generalist (non-specialist) medical practitioners.

As mentioned above, low salaries contribute to an exodus of qualified staff, with many health workers from Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan choosing to migrate to countries where salaries are higher, such as the Russian Federation. A study of family medicine residents in Kyrgyzstan highlighted the importance of improving working conditions – providing housing, Internet, basic medical equipment, protected time off, better salaries, and more respect – and improving clinic efficiency, such as switching clinic scheduling from walk-in-based to appointment-based, optimizing the roles of clinical team members and decreasing low-value clinic visits [29]. Kazakhstan now has a dedicated human resources observatory under the Ministry of Health, but in the other three countries health workforce planning is still underdeveloped [17].

3.2. Goals of universal health coverage

3.2.1. Access

Each of the four countries has a substantial network of publicly run primary care facilities. Yet access remains a challenge, for both financial and geographical reasons. Detailed data on how far each of these components contributes to unmet needs are generally unavailable, but in Uzbekistan in 2020 18 % of households reported that at least one household member had not sought medical treatment due to cost [35]. Similarly, in Tajikistan 35 % of women who forewent needed care in 2017 did so for lack of money [13]. Evidence from Tajikistan also illustrates how different groups of the population are impacted differently by financial barriers, with the richest quintile using health services more frequently than the poorest quintile across all areas of care, including primary care. The share of women who forewent needed care was 58 % in the poorest quintile [13]. While the Tajik government has introduced public benefit packages and financial protection mechanisms, these data illustrate that these are not fully effective. Further information on financial barriers is provided in the section below on financial protection.

Geographical access is the other major challenge, particularly in rural, remote and mountainous areas. The governments in the region have undertaken major efforts to ensure equitable geographical access in rural areas, with substantial investments from governments and external development partners, but inequalities in access remain [17], [18], [28], [36]. There is a shortage of health workers (particularly physicians) in rural and remote areas, and poor infrastructure can mean that facilities face additional challenges with electricity, access to Internet, heating or sanitation [21], [29]. Perhaps unsurprisingly therefore, rural primary care facilities remain underused, as was observed in Tajikistan [37], [38], with the result that there are referrals for cases that should be treated or diagnosed in primary care, as well as many unnecessary and unnecessarily prolonged hospitalizations (see more details in quality section below).

In Tajikistan, the government has introduced a range of incentives to try and motivate doctors to spend time in rural areas, but with limited success. For example, the Ministry of Health has adopted a policy that obliges recent graduates, whose education was fully funded by the state, to spend the first 3 years after obtaining their diploma practising in rural areas, but in reality the policy is not fully implemented [18]. Kyrgyzstan has also tried a range of approaches and is now educating family medicine residents at rural sites and improving salaries [29].

3.2.2. Quality

Delivering quality health services has been described as a “global imperative for universal health coverage” [39]. Quality of care has been defined as “the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge” [40]. The essential elements for delivering quality services are a well-trained health workforce; well-equipped health care facilities; the safe and effective use of medicines, devices and technologies; the effective use of health information systems; and mechanisms that support continuous quality improvement [39].

While the four countries considered here have undertaken efforts to improve the quality of primary care, there is still much scope for further progress. Robust and comparable data on quality of primary care are lacking, but what evidence is available points to unnecessary procedures, a general underuse of primary care and an overuse of specialized and hospital care.

In Kyrgyzstan, for example, hospital admissions for conditions that could be treated at primary care level are much higher than in OECD countries. There were 705 hospital admissions for diabetes per 100 000 population in Kyrgyzstan in 2018, compared with 49 in Iceland (the OECD country with the lowest rate) and 298 in Turkey (the OECD country with the highest rate). Hospital admissions for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease stood at 573 per 100 000 population in Kyrgyzstan in 2018, compared to 29 in Mexico (the OECD country with the lowest rate) and 382 in Turkey (the OECD country with the highest rate) [41].

Similarly, in Tajikistan a study using randomly selected medical records from 15 hospitals and covering 440 children and 422 pregnant women found that unnecessary hospitalisations accounted for 40.5 % and 69.2 % of hospitalisations, respectively, ranging from 0 % to 92.7 % across the 15 hospitals. Among necessary hospitalisations, 63.0 % and 39.2 % were unnecessarily prolonged in children and women, respectively [37]. Primary care seems to perform poorly in terms of hypertension detection and management [42] and a cross-sectional survey among 1600 adult patients who had visited a primary care facility found a high prescription rate for intravenous and other injections, including antibiotics and vitamins [43]. An assessment of sexual, reproductive, maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health in Tajikistan found that the scope provided in primary care was limited. Key diagnostic tests (such as urine analysis, blood tests and ultrasound) were currently not consistently available, and patients were routinely referred for essential diagnostic and treatment services (such as insertion of intrauterine devices and testing and treatment of STIs) [38].

In Uzbekistan, the limited available data suggest that there are significant gaps in quality of care [28], [35]. It has been estimated that substandard care was responsible for 58 % of amenable deaths in 2016, while the remainder was due to underuse of services [44]. However, this estimate relates to health services generally and is not specific to primary care.

In Kazakhstan, hospital admissions for ambulatory care sensitive conditions (ACSCs) were found to be high compared to OECD countries. In 2015 around 509 over 15-year-olds per 100 000 population were hospitalized due to asthma or COPD in Kazakhstan, which was much higher than in OECD countries and compared to 58 in Japan, 89 in Portugal and 150 in France. Hospital admissions due to diabetes, at 327 per 100 000 population in 2015, were higher than in most OECD countries [11]. Hospitalization rates in 2015 were also high for other ACSCs, including infectious and parasitic diseases (75 %), pneumonia (85 %), epilepsy (37 %) and angina pectoris (36 %) [45]. Over 75 % of hospitalizations for hypertension could have been avoided [45].

Changing clinical practice is crucial for quality improvement and one important intervention for achieving this are evidence-based care standards [39]. In all four countries considered here, outdated clinical protocols for primary care have been updated. In Uzbekistan, for example, the Ministry of Health has updated the WHO Package of Essential Noncommunicable Disease (NCD) protocols and begun implementing the package as a pilot in the Syrdarya region. In addition, national specialists are involved in implementation research on brief interventions on NCD risk factors at the primary care level and on nutrition policies in schools [21]. However, quality monitoring mechanisms are underdeveloped and, as was observed in Uzbekistan [46], it remains too easy for physicians to provide low-quality or unnecessary services.

Disease management programmes can help to improve quality by ensuring consistent, integrated and effective pathways of care [39]. Kazakhstan is working on rolling out disease management programmes for diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, and chronic heart failure, with currently over 1 million patients enrolled (55.3 % of all registered patients with these diagnoses). It remains to be seen how effective these initiatives will be in reducing the previously high hospitalizations rates for ACSCs (see above).

In Kyrgyzstan, the ongoing Primary Health Care Quality Improvement Program, supported by the World Bank and running from 2019 to 2024, aims to improve the quality of primary care by establishing and strengthening systems for quality reporting and monitoring, the strategic purchasing for quality services and improved coverage for selected priority conditions, and establishing a national-level structure and mechanism for coordinated efforts to improve quality of care in the country. By March 2023, progress in programme implementation was mixed. A unit designated to quality improvement had been established in the Ministry of Health, but the benefit package had not yet been revised to improve coverage for selected priority conditions at primary care level and only one of the anticipated 30 clinical guidelines had been revised [47].

Tajikistan has also recognized the need to improve the quality of health services. Under the National Health Strategy for 2010–2020, strengthening service quality and access were recognized as key objectives, with a particular focus on primary care, and improving the quality of healthcare services is also a strategic direction of the 2021–2030 health strategy. As part of these efforts, between 2010 and 2020, over 700 new standards and 50 guidelines were developed [48]. However, there is little evidence so far on their application in practice and related patient outcomes.

Improving health information systems can facilitate quality improvements. In Kyrgyzstan, for example, a national electronic database for primary care data was already established in 2012. A feasibility study covering four primary care clinics in Bishkek in 2019 found that the database could be used to gain information on quality of care and the disease burden of the patient population [49]. In Kazakhstan, monitoring for hospitalization of patients with conditions that should be addressed at ambulatory level is now a routine practice of the national Social Health Insurance Fund and part of the indicators used for incentive payments to primary care.

3.2.3. Financial protection

Financial protection of the population from the costs of using health services means that services are largely publicly financed and do not result in catastrophic and impoverishing expenditure. Internationally comparable data on the incidence of catastrophic health spending use three different thresholds: the population with household expenditure on health greater than 10 % of household expenditure or income; the population with household expenditure on health greater than 25 % of household expenditure or income; and the population with household expenditure on health greater than 40 % of capacity to pay for health care [50].

The WHO Regional Office for Europe uses the latter approach, but data are only available for two of the four countries discussed in this article, Kyrgyzstan (for 2014) and Uzbekistan (for 2021) [50]. In Uzbekistan nearly one quarter of households (23.9 %) in 2021 reported that they had experienced catastrophic health spending [21]. The share was lower in Kyrgyzstan (12.8 %) in 2014, despite a higher share of out-of-pocket spending as a percentage of current health expenditure in the same year, indicating that better mechanisms for financial protection might have been in place. However, it should be noted that available data on financial protection in Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan relate to overall health spending and do not specifically relate to primary care. Data from WHO are available for all four countries using the 10 % threshold [50], but these data are quite out of date (2.7 % of adults in Kazakhstan in 2015, 3.3 % in Kyrgyzstan in 2016, 7.6 % in Tajikistan in 2007, 10.6 % in Uzbekistan in 2003). Newer data calculated by the World Bank for Tajikistan suggest that 10.3 % of the population faced catastrophic expenditure in 2018 when using the 10 % threshold and 5.3 % did so when using the 40 % threshold of non-food expenditure [13]. However, again, these data relate to overall health expenditure by households and not specifically to spending on primary care.

4. Discussion

This article has explored the progress the four countries have achieved in improving primary care on the path towards achieving universal health coverage, but also the challenges that remain. We have examined how the countries are doing in terms of four key health system functions (governance, provision, financing and resource generation) and in terms of the three main goals of universal health coverage (access, quality and financial protection).

Strengthening primary care is on the agenda in many countries in Europe, but progress has been variable. Challenges in Europe include attracting a sufficient number of health professionals [51], investing in infrastructure and equipment, accelerating uptake of digital solutions, creating stronger financial incentives, developing performance monitoring, and investing in prestige and trust [52].

In Central Asia, many of the same challenges can be identified. Encouraging signs are that an increasing share of spending is devoted to primary care (in particular in Kazakhstan), that the training of primary care workers has been revamped, and that quality of care is increasingly coming into focus.

On the whole, however, primary care does not yet seem to contribute as much to universal health coverage in the Central Asian countries as it could. Primary care is generally underutilized and there is unnecessary use of hospitalizations or more specialized care. Improving the quality of care, and the financial protection of patients for receiving health care, seem two crucial avenues where improvements could be made.

Developing information systems for the continuous collection and reporting of quality-of-care data will be important and first steps are being taken in this direction Another obstacle that will need to be overcome to improve data collection is the definition of what counts as primary care, which is currently very broad in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. Without a better confined understanding, it is difficult to see what financial and human resources are needed in primary care. Similar problems of defining primary care have been noted in other low- and middle-income countries [53].

Introduction of digital health interventions can help to improve the accessibility and quality of care. For instance, already developed local electronic medical record systems in Kazakhstan were instrumental during the COVID-19 outbreaks to contribute to building digital tools for analysis and management at the national level and facilitate telemedicine services for the continued provision of essential health services.

Additional efforts are also needed in human resources planning and to make primary care more attractive to both medical graduates and patients. This will necessitate a greater public investment in health workers and facilities. It may also include looking at ways to incentivize patient usage of primary care, such as offering prescribed outpatient medicines or reducing the cost of prescriptions.

Ultimately, health reforms aimed at achieving universal health coverage by strengthening primary care are a political process that entails the redistribution of power and resources [23], often against the entrenched interests of hospitals and specialists. This means that for political declarations of strengthening primary care to be effective, there needs to be the political will to shift resources from hospital and specialized care, along with accountable mechanisms to deliver this. There are signs that this is happening in Kazakhstan, but the other three countries seem to be lagging behind.

5. Conclusions

Attempts at strengthening primary care have been a central element of health reforms in Central Asia in the last three decades. The structure of provision has changed, provider payment mechanisms reformed, health workers trained, and efforts have started to improve quality of care. Yet, there is still a long way to go towards achieving universal health coverage in terms of access to and quality of care, as well as financial protection. Too much of the financial burden is still on patients, preventing them from accessing essential services, and provision of primary care in rural and remote areas remains a challenge for which there are no easy solutions.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Bernd Rechel: . Aigul Sydykova: . Saltanat Moldoisaeva: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Investigation, Data curation. Dilorom Sodiqova: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Investigation. Yerbol Spatayev: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Investigation. Mohir Ahmedov: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Investigation. Susannah Robinson: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Investigation, Formal analysis. Anna Sagan: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This article is based on work funded by the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. The funding body had no involvement in the findings presented here.

References

- 1.WHO, Declaration of Alma-Ata, International Conference on Primary Health Care, Alma-Ata, USSR, 6–12 September 1978 [(https://www.who.int/publications/almaata_declaration_en.pdf, accessed 20 March 2023]. 1978, World Health Organization: Geneva.

- 2.Rifkin S.B. Alma Ata after 40 years: Primary Health Care and Health for All-from consensus to complexity. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3(Suppl 3) doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanders D., Nandi S., Labonté R., Vance C., Van Damme W. From primary health care to universal health coverage-one step forward and two steps back. Lancet. 2019;394(10199):619–621. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31831-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO, Universal health coverage [https://www.who.int/healthsystems/universal_health_coverage/en/, accessed 19 January 2021]. 2021, World Health Organization: Geneva.

- 5.UN, Policy Brief: COVID-19 and Universal Health Coverage [https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/sg_policy_brief_on_universal_health_coverage.pdf, accessed 19 January 2021]. 2020, United Nations: New York.

- 6.UN, The 17 Goals [https://sdgs.un.org/goals, accessed 24 September 2023]. 2023, United Nations: New York.

- 7.Papanicolas I. et al., eds. Health system performance assessment: a framework for policy analysis. 2022, World Health Organization (acting as the host organization for, and secretariat of, the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies): Copenhagen. [PubMed]

- 8.WHO, Primary health care on the road to universal health coverage: 2019 global monitoring report. 2019, Geneva: World Health Organzation.

- 9.Rechel B, Maresso A, and van Ginneken E. Health Systems in Transition. Template for authors [https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/publications/i/health-systems-in-transition-template-for-authors, accessed 20 March 2023]. 2019, World Health Organization 2019 (acting as the host organization for, and secretariat of, the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies): Copenhagen.

- 10.WHO, The world health report: health systems: improving performance. 2000, Geneva: World Health Organzation.

- 11.OECD, OECD Reviews of Health Systems: Kazakhstan 2018. 2018, OECD Publishing: Paris.

- 12.Greer SL, Wismar M. and Figuera J. eds. Strengthening health system governance: better policies, stronger performance. 2016, World Health Organization (acting as the host organization for, and secretariat of, the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies): Copenhagen.

- 13.World Bank, Tajikistan - Public Expenditure Review: Strategic Issues for the Medium-Term Reform Agenda (English). 2021, World Bank Group: Washington, D.C.

- 14.Transparency International, Corruption Perceptions Index 2022 [https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2022, accessed 20 November 2023]. 2023, Transparency International: Berlin.

- 15.Rechel B., Ahmedov M., Akkazieva B., Katsaga A., Khodjamurodov G., McKee M. Lessons from two decades of health reform in Central Asia. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27(4):281–287. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czr040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rechel B. and McKee M. Lessons from polyclinics in Central and Eastern Europe. BMJ 2008; 337: a952.

- 17.Moldoisaeva S., et al. Kyrgyzstan: Health System Review. Health Syst Transit. 2022;24(3):1–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robinson S. and Rechel B. Health Systems in Action: Tajikistan. 2022, Copenhagen: World Health Organization (acting as the host organization for, and secretariat of, the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies).

- 19.Khodjamurodov G., et al. Tajikistan: Health System Review. Health Syst Transit. 2016;18(1):1–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Bank, Transforming the performance of the health system of Uzbekistan by 2030. 2023, World Bank: Washington.

- 21.Robinson S. Health Systems in Action: Uzbekistan. 2022, Copenhagen: World Health Organization (acting as the host organization for, and secretariat of, the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies).

- 22.Eriksen A, Litvinova Y. and Rechel B. Health Systems in Action: Kazakhstan. 2022, Copenhagen: World Health Organization (acting as the host organization for, and secretariat of, the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies).

- 23.Jacobs E. The politics of the basic benefit package health reforms in Tajikistan. Glob Health Res Policy. 2019;4:14. doi: 10.1186/s41256-019-0104-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.WHO, Global Health Expenditure database [https://apps.who.int/nha/database/Home/Index/en, accessed 17 February 2023]. 2023, World Health Organization: Geneva.

- 25.Donadel M., Karimova G., Nabiev R., Wyss K. Drug prescribing patterns at primary health care level and related out-of-pocket expenditures in Tajikistan. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1) doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1799-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gulis G., Aringazina A., Sangilbayeva Z., Zhan K., de Leeuw E., Allegrante J.P. Population Health Status of the Republic of Kazakhstan: Trends and Implications for Public Health Policy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(22):12235. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182212235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rechel B. Richardson E. and McKee M. eds. Trends in health systems in the former Soviet countries. 2014: Copenhagen (Denmark). [PubMed]

- 28.Ahmedov M. et al., Uzbekistan: health system review. Health Syst Transit, 2014; 16(5): 1-137, xiii. [PubMed]

- 29.Fonken P., et al. Keys to Expanding the Rural Healthcare Workforce in Kyrgyzstan. Front Public Health. 2020;8:447. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hardison C., et al. The emergence of family medicine in Kyrgyzstan. Fam Med. 2007;39(9):627–633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schubiger M., Lechthaler F., Khamidova M., Parfitt B.A., Prytherch H., van Twillert E., et al. Informing the medical education reform in Tajikistan: evidence on the learning environment at two nursing colleges. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1) doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1515-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.WHO, Tajikistan is reforming Primary Health Care to reach Universal Health Coverage [https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/tajikistan-is-reforming-primary-health-care-to-reach-universal-health-coverage, accessed 23 November 2023]. 2023, World Health Organization: Geneva.

- 33.Eurostat, Healthcare personnel statistics - physicians [https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Healthcare_personnel_statistics_-_physicians, accessed 29 September 2023]. 2023, Eurostat: Luxembourg.

- 34.WHO, European Health Information Gateway [https://gateway.euro.who.int/en/indicators/hfa_507-5290-general-practitioners-pp-per-100-000/, accessed 24 April 2023]. 2023, WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen.

- 35.World Bank, Assessing Uzbekistan’s Transition. Country Economic Memorandum, ch. 10: Health. (https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/862261637233938240/pdf/Full-Report.pdf). 2021, World Bank: Washington.

- 36.Shaltynov A., Rocha J., Jamedinova U., Myssayev A. Assessment of primary healthcare accessibility and inequality in north-eastern Kazakhstan. Geospat Health. 2022;17(1) doi: 10.4081/gh.2022.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jullien S., Mirsaidova M., Hotamova S., Huseynova D., Rasulova G., Yusupova S., et al. Unnecessary hospitalisations and polypharmacy practices in Tajikistan: a health system evaluation for strengthening primary healthcare. Arch Dis Child. 2023;108(7):531–537. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2022-324991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.WHO . World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe:; Copenhagen: 2021. Assessment of sexual, reproductive, maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health in the context of universal health coverage in Tajikistan. [Google Scholar]

- 39.WHO, OECD, and International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank, Delivering Quality Health Services: A Global Imperative for Universal Health Coverage. 2018, World Health Organization, OECD, and International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank: Geneva.

- 40.Institute of Medicine, Medicare: a strategy for quality assurance, volume I. 1990, National Academies Press: Washington (DC). [PubMed]

- 41.Ahmedov M. et al., Assessing Quality of Care in the Kyrgyz Republic: Quality Gaps and Way Forward [https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/34376, accessed 26 November 2021], in Health, Nutrition and Population Discussion Paper. 2020, World Bank.: Washington, DC.

- 42.Chukwuma A., Gong E., Latypova M., Fraser-Hurt N. Challenges and opportunities in the continuity of care for hypertension: a mixed-methods study embedded in a primary health care intervention in Tajikistan. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1) doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4779-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fischer F.B., Mengliboeva Z., Karimova G., Abdujabarov N., Prytherch H., Wyss K. Out of pocket expenditures of patients with a chronic condition consulting a primary care provider in Tajikistan: a cross-sectional household survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1) doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05392-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kruk M.E., Gage A.D., Joseph N.T., Danaei G., García-Saisó S., Salomon J.A. Mortality due to low-quality health systems in the universal health coverage era: a systematic analysis of amenable deaths in 137 countries. Lancet. 2018;392(10160):2203–2212. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31668-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.WHO, Ambulatory care sensitive conditions in Kazakhstan. 2015, World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen.

- 46.Cho M.J., Haverkort E. Out-of-pocket health care expenditures in Uzbekistan: progress and reform priorities, in Rural Health - Investment. Research and Implications. 2023:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 47.World Bank, Primary Health Care Quality Improvement Program [https://projects.worldbank.org/en/projects-operations/project-detail/P167598?lang=en, accessed 1 October 2023]. 2023, World Bank: Washington, DC.

- 48.Ministry of Health and Social Protection, Strategy for protecting the health of the population of the Republic of Tajikistan for the period until 2030 (Decree No. 414 of the Government of Tajikistan). . 2021: Dushanbe.

- 49.Laatikainen T., Inglin L., Chonmurunov I., Stambekov B., Altymycheva A., Farrington J.L. National electronic primary health care database in monitoring performance of primary care in Kyrgyzstan. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2022;23:e6. doi: 10.1017/S1463423622000019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.WHO, Global Health Observatory [https://www.who.int/data/gho, accessed 30 September 2023]. 2023, World Health Organization: Geneva.

- 51.Kroezen, M., D. Rajan, and E. Richardson, Strengthening primary care in Europe: How to increase the attractiveness of primary care for medical students and primary care physicians? 2023, World Health Organization: Copenhagen. [PubMed]

- 52.WHO Regional Office for Europe, Primary health care: making our commitments happen. Realizing the potential of primary health care: lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic and implications for future directions in the WHO European Region. 2022, WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen.

- 53.Moosa S. Provider perspectives on financing primary health care for universal health coverage. Lancet Glob Health. 2022;10(5):e609–e610. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(22)00173-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]