Graphical abstract

Keywords: Ultrasound, SonoVue microbubbles, Cancer therapy, 3D vascularized cancer model, Microbubble dynamics

Highlights

-

•

A 3D vascularized cancer model was established for ultrasound and microbubble studies.

-

•

Microbubble traveling dynamics in the 3D cancer model was revealed.

-

•

Microbubble cavitation dynamics in 2 %(w/v) agarose gels were captured at 0.675 M fps.

-

•

Microbubbles were distributed everywhere inside the cancer cell spheroids.

-

•

Cancer cell spheroid penetration enhancement with sparse permanent cell damage.

Abstract

Accumulating evidence has shown that ultrasound exposure combined with microbubbles can enhance cancer therapy. However, the underlying mechanisms at the tissue level have not been fully understood yet. The conventional cell culture in vitro lacks complex structure and interaction, while animal studies cannot provide micron-scale dynamic information. To bridge the gap, we designed and assembled a 3D vascularized microfluidic cancer model, particularly suitable for ultrasound and microbubble involved mechanistic studies. Using this model, we first studied SonoVue microbubble traveling dynamics in 3D tissue structure, then resolved SonoVue microbubble cavitation dynamics in tissue mimicking agarose gels at a frame rate of 0.675 M fps, and finally explored the impacts of ultrasound and microbubbles on cancer cell spheroids. Our results demonstrate that microbubble penetration in agarose gel was enhanced by increasing microbubble concentration, flow rate and decreasing viscosity of the gel, and little affected by mild acoustic radiation force. SonoVue microbubble exhibited larger expansion amplitudes in 2 %(w/v) agarose gels than in water, which can be explained theoretically by the relaxation of the cavitation medium. The immediate impacts of ultrasound and SonoVue microbubbles to cancer cell spheroids in the 3D tissue model included improved cancer cell spheroid penetration in micron-scale and sparse direct permanent cancer cell damage. Our study provides new insights of the mechanisms for ultrasound and microbubble enhanced cancer therapy at the tissue level.

1. Introduction

Suppressed penetration and incomplete distribution throughout tumors are great challenges that intravenously administrated chemotherapeutic drugs are facing. Solid tumors are surrounded by large amount of stroma. The solid stress accumulating in tumors due to the proliferation of cancer and stromal cells collapses tumor blood vessels, reducing vascular perfusion and thus the delivery efficiency of chemotherapeutic drugs [1]. The tumor stroma also forms a physical barrier for penetrating performance of chemotherapeutic drugs, diminishing their antitumor efficacy [2]. Moreover, the high tumor interstitial pressure further inhibits the convection of drugs from blood vessels to the rest of the tumor [3]. Together, the intra-tumoral deposition of chemotherapeutic drugs is far from sufficient for effective treatment. Therefore, the combination with targeted drug delivery techniques enhancing extravasation and intra-tumoral distribution of chemotherapeutic drugs could significantly improve the antitumor treatment at tumor sites while minimize the side effects in healthy cells elsewhere.

Ultrasound exposure facilitated with ultrasound contrast agent microbubbles is a noninvasive, safe and effective drug delivery method with great targeting ability. The ultrasound beams can be applied extracorporeally and focused to the tumor sites. The gas-core microbubbles are widely used to generate predictable and controllable cavitation at the ultrasound focus with much lower ultrasound intensities. Human clinical trials using ultrasound and microbubbles to enhance chemotherapy for pancreatic cancer [4], [5] and hepatic metastases from the digestive system [6] have been conducted. The tolerability and therapeutic potentials have been demonstrated. In addition, several clinical trials combining ultrasound, microbubbles and chemotherapeutic drugs for cancer treatment is ongoing or upcoming [7].

At the cellular level, it is the interactions of cavitating microbubbles and cells that induce various beneficial cellular responses, leading to enhanced intracellular drug uptake. Both stable and inertial bubble oscillations can generate direct impingement on nearby cell surface [8], high-velocity microjets penetrating cell membranes [9], emit shock waves imposing significant stresses [10], and/or form microstreaming in the local fluid [11]. As a result, transient and reversible pores can be created on cell membranes providing a physical route for drug molecules intracellular uptake [12], [13], [14], [15]. In addition, enhanced endocytosis can facilitate macromolecule transmembrane transport [16]. When applied in vivo, microbubbles are introduced into the bloodstream. Animal studies demonstrated that ultrasound and microbubbles can enhance vascular permeability, promote drug extravasation, alter tumor tissue structure, thereby increase the intra-tumoral penetration and retention of drugs [17], [18], [19], [20]. By analyzing tissue sections, animal studies provided valuable knowledge about the mechanisms in vivo. However, tissue sections can only provide end-point static images. It is challenging to monitor dynamic details of microbubbles in animals.

Even with accumulating understanding of the underlying mechanisms, however, the detailed processes of ultrasound and microbubbles enhanced cancer therapy at the tissue level remain elusive. In particular, several fundamental questions need to be addressed at the tissue level. For instance, how can microbubbles travel across the tumor leaky blood vessel wall and penetrate through the dense stroma, by passive diffusion, pushed by acoustic radiation force, or facilitated by violent inertial cavitation? What are the acoustic behaviors of microbubbles in dense and viscous tumor tissue? What are the mechanisms for microbubble enhanced cancer therapy, direct killing of cancer cells, enhanced intracellular drug delivery or increasing tumor tissue permeation of drug molecules? Neither conventional cell culture nor animal experiments can study these questions. Microfluidic cancer models can recapitulate the organ-level structure, cancer microenvironment and blood flows [21], [22], [23], therefore providing a powerful tool for mechanistic investigation at the tissue level. All the cellular, molecular, chemical and physical parameters can be precisely controlled and varied easily in the model. Moreover, the small-size and transparency of the whole device allow real-time microscopic observation.

In this study, we developed a 3D vascularized microfluidic cancer model. SonoVue microbubble solution was injected at a physiological blood flow rate in the bottom channel, while the penetration of microbubbles through a porous membrane into the top tissue layer was monitored continuously. The tissue layer was filled with viscous agarose gels embedded with cancer cell spheroids. The effects of microbubble concentration, flow rate, and acoustic radiation force on the penetration dynamics were studied. The acoustic behaviors of microbubbles in agarose gels under ultrasound exposure were imaged using high-speed video-microscopy and correlated with the 3D fluorescent confocal microscopic images of the cancer spheroids, which were used to assess structure changes of the spheroid, cell viability and intracellular uptake of the model drug. This study was designed to unveil the dynamic processes and the underlying mechanisms of ultrasound and microbubble enhanced cancer therapy at the tissue level, highlighting the role microbubbles played.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Microfluidic cancer model fabrication

The microfluidic model chip consisted of upper and lower microchannels separated by a porous membrane. The upper channel recreated the tumor tissue, having no flow with an open top. The size of the upper channel was 1 mm (width) × 32 mm (length) × 1 mm (height). The lower channel recapitulated the blood vessel, enabling continuous flow of microbubble solution. The size of the lower channel was 1 mm (width) × 32 mm (length) × 0.1 mm (height). To represent the leaky cancer vascular basement membrane, a nucleopore polycarbonate (PC) hydrophilic membrane (Whatman, USA) with the pore diameter of 10 µm, porosity of 4–20 %, and thickness of 7–20 µm was employed.

The upper and lower channels were fabricated using soft lithography. In brief, the PDMS prepolymer and curing agent (Sylgard 184, Dow-Corning) were mixed at a precise 10:1 ratio. After thorough mixing and degassing, the mixture was poured into the polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) mold for the upper channel and the silicone mold for the lower channel. The molds were cured at 65 °C for 90 min. The PDMS channel was subsequently separated from the silicon master and subjected to a 1 min air plasma oxidation process. The upper and lower channels were distinctly marked with cross symbols at designated locations. Upon plasma treatment, precise alignment and bonding of the channels with a PC membrane were achieved. The assembled mold was then subjected to a compression process under weights for a minimum duration of 2 h. After thorough disinfection with alcohol and UV irradiation, the chip was ready for subsequent experimental procedures. To provide precisely controlled perfusion rate, the inlet and outlet of the bottom channel was connected to a bidirectional digital micro-infusion pump (RSP04-C, Beta Instrument, China) via syringes and polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) tubes. Three-way valves and check valves were applied to convert the bidirectional pumping into a unidirectional flow in the bottom channel.

Before the ultrasound and microbubbles experiment, the culture medium containing Hela cell spheroids (90 % DMEM + 10 % FBS) was gently transported into the upper channel through the open top. The cell spheroids were then allowed to incubate for a period of 10 h, facilitating their settling in the channel. Then, the culture medium from the upper channel was carefully aspirated, and agarose gels were added. Different concentrations of agarose gels were prepared by blending agarose gels and cell culture medium. Finally, a glass coverslip was used to cover the open top.

2.2. Cancer cell spheroid formation

Hela cells were cultured at 37 °C and with 5 % CO2 in DMEM supplemented with 10 % bovine serum. When cells reached 80 % confluence, cells were harvested in suspension after 3 min-incubation with 0.25 % trypsin-EDTA buffer solution. Cell suspension was centrifuged and then cell suspension with the concentration of 1.2 × 105 cells/ml was made. Droplets of 25 µl cell suspension were carefully positioned on the dried surfaces of petri dish lids. Then the lids were gently flipped and placed on the culture dishes, which was filled a small amount of culture medium without touching the facing-down cell-containing droplets. Maintaining appropriate humidity was crucial for the normal growth of cells and the formation of cell spheroids. The relatively close and humidified environment prevented evaporation or drying of the small droplets and thus maintained their shapes for days. After 3 to 4 days of incubation at 37 °C with 5 % CO2, cell spheroids were formed. The diameter of the spheroids was around 300 µm. We used pipette to harvest, collect and transport droplets.

2.3. Ultrasound apparatus and microbubbles

A single element planar ultrasound transducer (1.5 MHz, Jiangyin AD Ultrasonic Technology Inc.), driven by a waveform function generator (33250A, Agilent Technologies) and a 100 W power amplifier (75A250, Amplifier Research) was used to generate ultrasound pulses. The ultrasound transducer was positioned in a 3D-printed transparent polyurethane resin holder, filled with ultrasound coupling gels, 17.4 mm (Rayleigh distance) away from the top of the microfluidic chip at a 45° angle to activate microbubbles. To promote microbubble translation cross the porous membrane and through the stroma, the ultrasound transducer was positioned 17.4 mm away right underneath the microfluidic chip, facing up and coupled with ultrasound coupling gels. A needle hydrophone (HGL-0400, ONDA) was applied to calibrate the acoustic pressure in the free field. SonoVue (Bracco Sisses SA, Switzerland) microbubbles were used in this study.

2.4. High-speed video-microscopy and confocal fluorescence microscopy

A high-speed camera (FASTCAM SA-X2, Photron) integrated on an inverted laser confocal fluorescence microscope (FV3000, Olympus) with a PLAPON 60X (NA 1.42, WD 0.15) oil objective was employed for recording microbubble cavitation dynamics. The frame rate of 0.675 M frames per second (fps) with an exposure time of 0.46 μs and a field of view (FOV) of 128 × 16 pixels was adopted to capture bubble dynamics excited by ultrasound. The confocal fluorescence microscope with an extralong working distance objective, LUCPLFLN 40X (NA 0.95, WD 0.18) air objective, was utilized to capture bright field and fluorescent images. The sample was excited at 488 nm and 561 nm to image Calcein and PI respectively and alternatively. To stain live cells in cell spheroids right before ultrasound and microbubble experiments, Calcein AM was dissolved into the cell culture medium in the upper channel of the microfluidic chip for 3 min before removing by careful aspiration of the medium. Propidium iodide (PI) was dissolved in the agarose gel at the final concentration of 100 µM.

2.5. Statistics

All experiments were repeated at least three times independently. The quantitative results were presented by mean values and standard error (SD).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Design of the 3D vascularized microfluidic cancer model

We adopted the typical sandwiched structure for the cancer model, i.e., top tissue layer, bottom microfluidic channel and a porous membrane in the middle. However, three key features in our design made our cancer model particularly suitable for ultrasound and microbubble involved mechanistic study (Fig. 1). First, PC membranes with randomly distributed 10 µm-diameter pores, with 4–20 % porosity and 7–20 µm thickness were chosen to mimic the leaky tumor blood vessel wall separating the top tissue layer and bottom microfluidic channel. Compared with the porous membranes or semipermeable membranes, which were used to resemble normal tissues [24], [25], larger pore size and higher porosity (1 ∼ 6 × 104/mm2) of the PC membrane we used better recapitulated the features of premature and leaky tumor blood vessels. The large pore size permitted microbubbles (1–7 µm diameter) to travel through. Second, we used droplets to form cancer cell spheroids (∼300 µm in diameter) in a petri dish over 72 h and then transferred them into agarose gels in the top channel before the ultrasound and microbubble experiments. The cancer model we designed here was to study the instantaneous microbubble dynamics and the responses of cancer cell spheroids immediately after ultrasound and microbubble treatment, which occurred in minutes. Therefore, unlike the tissue modeling in many other studies [26], [27], where continuous and prolonged (over days) culture of cells was needed, the strategy of transferring cancer cell spheroids into the microfluidic chip in the agarose gel right before the experiment simplified cell culture produce and thus significantly increased the success rate of cancer model formation. Finally, we designed an open top channel without microfluidic inlet and outlet. On one hand, the top opening was very friendly for transferring cancer cell spheroids because it prevented cell spheroids from disassociation when flowing through tubes under shear stress. On the other hand, the 0.15 mm-thick glass coverslip performed well for optical transmission, acoustic transmission and gel coupling on both sides. A transparent polyurethane resin holder was designed and 3D printed to connect the ultrasound transducer and the microfluidic chip.

Fig. 1.

Experimental setup and the 3D vascularized microfluidic cancer model. (A) Schematic showing that a 1.5 MHz single element planar transducer was positioned at a 45° angle, 17.4 mm (Rayleigh distance) from the top of the microfluidic chip in a resin holder filled with ultrasonic coupling gels. The confocal fluorescence microscope was equipped with a high-speed camera. (B) Design of the 3D vascularized microfluidic cancer model. SonoVue microbubbles were injected into the bottom layer and traveled through the porous membrane into the top tissue layer filled with Hela cell spheroids and agarose gels. (C) Photograph of the microfluidic chip and microscopic images of a Hela cell spheroid, the porous membrane and SonoVue microbubbles in agarose gels.

3.2. Microbubble traveling through 3D tissue structure

We first studied the microbubble traveling and penetration dynamics in the 3D vascularized cancer model. According to the microbubble dose used in the clinical trial [6], a bottle of SonoVue powder was dissolved into 5 ml of saline, and then diluted 2000 times (v/v) in saline (1∼2.5 × 105MBs/ml). The top channel was filled with 0.2 %(w/v) or 2 %(w/v) tissue mimicking agarose gels. The microbubble solution was gently injected into and filled the bottom microfluidic channel and then zero or 6 µl/min flow rate (resembling that in capillary vessels) was applied. Bright field microscopic images were taken at the upper surface of the porous membrane (z = 0 µm), 100 µm and 300 µm above the porous membrane in the agarose gel every 30 s alternatively, up to 7 min starting from the time point when microbubbles emerged at the porous membrane. The number of microbubbles in each image were counted manually. We found that at 1∼2.5 × 105 MBs/ml (1c) only a few microbubbles can travel into the tissue layer from the blood vessel (Fig. 2A). Since the microbubble suspension was injected in bolus clinically, which could lead much higher local microbubble concentration than the averaged concentration, we then increased the microbubble concentration to 5∼12.5 × 105 MBs/ml (5c) (Fig. 2B) and 1∼2.5 × 106 MBs/ml (10c) (Fig. 2C). Microbubbles quickly travelled through the porous membrane and showed up at its upper surface. Microbubbles appeared at 100 µm and 300 µm in agarose gels later and in less amount, since the viscosity of the matrix hindered their movement. As the microbubble concentration increased, more microbubbles appeared at all three levels in the tissue phantom. However, the number was not proportional to the microbubble concentration in the vessel. Compared with 0.2 %(w/v) agarose gels (Young’s modulus 1 ∼ 5 kPa [28], [29]), the higher viscosity of 2 %(w/v) agarose gels (Young’s modulus 8–20 kPa [28], [29]) significantly inhibited microbubble penetration through the tissue phantom (Fig. 2D). The flow rate in the bottom microfluidic channel enhanced the microbubble penetration through the tissue phantom. The flow rate endued microbubbles with kinetic energy to pass the porous membrane, thus prominent increase of bubble number at the upper surface of the porous membrane was observed (Fig. 2E). In addition, continuous perfusion rendered a persistent increase of the bubble number over 5 min, in contrast to the stabilization without flow rate. The microbubble penetration in agarose gels 100 µm and 300 µm above the porous membrane was less affected by the flow rate, as the viscosity played an important role deeper in the tissue.

Fig. 2.

The number of microbubbles observed in a 318 µm × 318 µm area right above the porous membrane (z = 0 µm), 100 µm and 300 µm above the porous membrane in agarose gels under different conditions. (A-C) The microbubble concentration in saline filled in the bottom microfluidic channel was 1∼2.5 × 105 MBs/ml (1c), 5∼12.5 × 105 MBs/ml (5c), and 1∼2.5 × 106 MBs/ml (10c). The agarose gel in the top layer was 0.2 %(w/v). (D-F) The microbubble concentration of 1∼2.5 × 106 MBs/ml (10c) was filled in the bottom layer, and the agarose gel in the top layer was 2 %(w/v). In E and F, a 6 µl/min perfusion rate was applied. In F, a 1 min ultrasound pulse series was employed from the bottom up. N = 3 or 4 for each condition. Data represented as mean ± standard error.

The driven force for microbubble traveling into tissue layer so far was only buoyance, which was 0.14pN for a 1.5 µm-radius microbubble. We then tested the idea that whether acoustic radiation force could promote microbubble penetration into tissue phantom. We applied a 1 min ultrasound pulse series at a pressure of 0.25 MPa (PRF of 1 Hz, Duty cycle of 2.5 %) from the bottom up. The corresponding acoustic radiation force on a 1.5 µm-radius microbubble was calculated to be 13.79pN [30]. However, little difference was shown (Fig. 2F) compared with the absence of acoustic radiation force (Fig. 2E). The dense structure of tissues resisted microbubble movement. Hence, it may not be very easy to promote microbubble extravasation from the blood vessel and penetration into tissues by acoustic radiation force. Or our current ultrasound condition was suboptimal. Caskey et al reported tunneling phenomena in 0.75 %(w/v) agarose phantom [31]. The mechanical index of 1.5 indicated that with a 1 MHz central frequency the peak negative pressure was 1.5 MPa, which most likely induced inertial cavitation of microbubbles. Meanwhile, 0.75 %(w/v) agarose gels imposed lower resistance for microbubble penetration than 2 %(w/v) agarose gels, which has a Young’s modulus of 8–20 kPa, similar to human tissues [32]. To avoid undesired healthy cell damage along microbubble traveling paths, a low acoustic pressure was used here. In the future, we will optimize the ultrasound condition for microbubbles extravasation from blood vessels and elucidate whether enhanced extravasation has to be at the expense of healthy cells along the way.

3.3. Time-resolved acoustic dynamics of microbubbles in agarose gels

High-speed video microscopic recording at a frame rate of 0.675 M fps with 0.46 µs exposure time was employed, coupled with a 60x oil objective to capture the cavitation dynamics of microbubbles in agarose gels (Fig. 3). We applied a single 10cycle ultrasound pulse (each cycle of 0.667 µs and total duration of 6.67 µs) with different pressures. The ultrasound signal was synchronized with the high-speed microscopic image recording. The exposure time was slightly shorter than one ultrasound cycle and the image was taken every 1.48 µs. Bubble radius change upon ultrasound excitation was observed starting at 0.85 MPa and became more and more dramatic as the acoustic pressure increased. At 1.36 MPa, a 1.55 µm-radius microbubble expanded up to 3.11 µm-radius with almost 8 times volumetric inflation.

Fig. 3.

Selected images of SonoVue microbubbles in 2 %(w/v) agarose gels (A) and in saline (B) taken at a 0.675 M fps frame rate showing microbubble expansion during a 10cycle ultrasound pulse (central frequency of 1.5 MHz, total duration of 6.67 µs) from t = 0 with different acoustic pressures.

To better understand the impact of the viscoelasticity of agarose gels, mimicking soft tissue, on microbubble cavitation, we also recorded microbubble dynamics in water driven by a 10cycle ultrasound pulse of 1.36 MPa (Fig. 3B). A 1.55 µm-radius microbubble expanded up to 2.18 µm-radius, which was less violent than in agarose gels. Our experimental observations were qualitatively predicted by mathematical models, which were valid for large nonlinear deformation of the media and considered the relaxation of the cavitation media [33]. It was reported that the shear modulus G and shear viscosity µ of 2 %(w/v) agarose gels were 0.256 MPa and 0.280 Pa·s respectively [34]. Consequently, the relaxation time λ of 2 %(w/v) agarose gels, given λ=µ/G, was 0.91 µs. The simulation results with λ of 1.00 µs demonstrated that compared with a Newtonian flow, the nonlinear viscoelastic media led to aperiodic and much larger amplitude of microbubble oscillations [33]. This is because that the relaxation time of the material, λ, is longer than the driven harmonic force period, τ∼ω-1, accumulating stress cycle after cycle of oscillation [35].

Compared with water, agarose gels slightly reduced the contrast between background and microbubbles when imaging at 0.675 M fps frame rate. The presence of agarose gels increased the resonance frequency of microbubbles owing to the elasticity of the surrounding medium [36]. Most of SonoVue microbubbles have radius less than 1.5 µm. A 2.25 µm-radius encapsulated microbubble exhibited about 10 time radius expansion in water driven by a 20 µs burst of 1 MHz ultrasound at a peak pressure of 1.36 MPa, imaged at a frame rate of 0.5 M fps [9]. All the experiment conditions in this previous study are similar to our study. The main reason that could explain much smaller amplitude oscillation captured here is the smaller size of SonoVue, as the resonance frequency of microbubbles increases sharply as bubble radius decreases [36]. There are studies exploiting bubble dynamics in tissue mimicking gel phantom, that unveiled the impact of wall on microbubble collapse [37], cavitation cloud formation [38], tunnel formation [31], asymmetric oscillation [39] and elastic tissue deformation [40]. The time-resolved (0.675 M fps) SonoVue microbubble cavitation dynamics in 2 %(w/v) agarose gels presented here are uniquely relevant to the clinical trials using ultrasound and SonoVue microbubbles for enhanced cancer therapy.

In addition to cavitation dynamics, we also recorded the dissolution process of microbubbles after cavitation. Up to 600 ms after ultrasound exposure, some microbubbles gradually disappeared, while others maintained their sizes. Fig. 4 shows typical examples of two cases. The microbubble radius-time curves were nicely fitted by a dissolution model with 89 % perfluorocarbon and 11 % air in the gas core without shell (Fig. 4 A) and a dissolution model with air gas core with shell (Fig. 4 B) [41], respectively. The simulation results suggested that the first microbubble lost its shell during cavitation. For the second microbubble, its shell persisted during cavitation. However, the gas escape at about 120 ms may be due to the slight damage of the shell during cavitation.

Fig. 4.

SonoVue microbubble dissolution processes after cavitation and the fitting curves. (A) A microbubble gradually disappeared. (B) A microbubble maintained its size.

3.4. Immediate impacts of ultrasound excited microbubbles on cancer cell spheroids

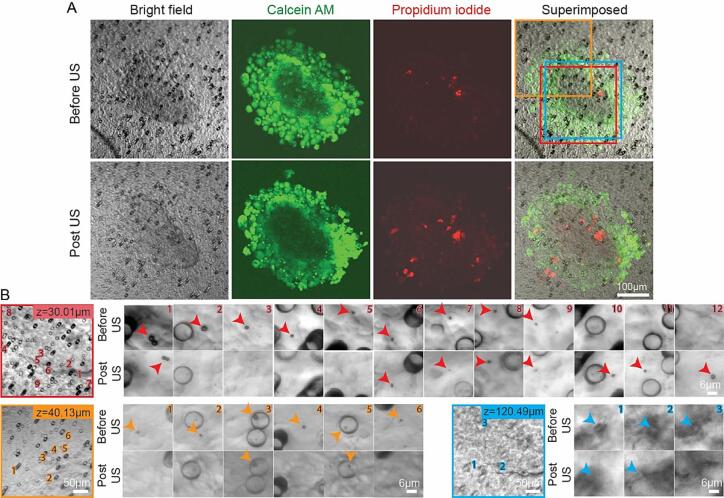

We assembled 3D vascularized microfluidic cancer models as described in section 3.1 and conducted investigations of the immediate impacts of ultrasound excited microbubbles on cancer cell spheroids, focusing on the role microbubbles played. The cancer cell spheroids were stained by Calcein AM right before the experiment so that live cells showed green fluorescence. PI was added into 2 %(w/v) agarose gels for cell membrane integrity detection. In the bottom microfluidic channel, 1∼2.5 × 106 MBs/ml (10c) microbubble solution was injected at the flow rate of 6 µl/min. Due the transparency of cells and the large size in 3D (diameter between 100 and 500 µm), cancer cell spheroids can’t be seen clearly in bright field images. We therefore used bright field images to study microbubbles and the green fluorescent images to identify cells (Fig. 5A). Unexpectedly, the unique local patterns of the randomly oriented and distributed 10 µm-diameter pores in the PC porous membrane became faithful spatial references to observe microbubble changes before and after ultrasound exposure.

Fig. 5.

A typical cancer cell spheroid in a 3D vascularized microfluidic model before and after microbubble and ultrasound treatment. (A) The bright field images, green fluorescent images of Calcein, red fluorescent images of PI and superimposed images before and after ultrasound exposure. Three areas at different z positions were selected and imaged under higher magnification, labeled in red, orange and blue frames. (B) Images of these three areas, in which SonoVue microbubbles were identified individually and their positions were labeled by number. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

At the shallow layers in the cancer cell spheroid, microbubbles appeared everywhere inside the spheroid, even in the center (Fig. 5B). At upper layers inside the spheroid, we observed much less microbubble. In the example shown in Fig. 5, at 30.01 µm above the PC porous membrane, 12 microbubbles were observed totally in the FOV. And the bubble number identified in the FOV 40.13 µm and 120.49 µm above the PC membrane were 9 (only 6 were shown in Fig. 5B) and 3 totally. There might be more than a hundred microbubbles inside this 215 µm-diameter-wide and 202 µm-high cancer cell spheroid. A 5 s pulse series at a pressure of 0.68 MPa, 10 % DC and 1 Hz PRF was applied. We observed that some microbubbles disappeared, some microbubbles shrank, some microbubbles have no change, and some microbubbles exhibited translational displacements (Fig. 5B). Moreover, some microbubbles emerged after ultrasound (bubble number 10–12 in Fig. 5B first row), which could be owing to the continuous microbubble perfusion from the bottom microfluidic channel or the motion of microbubbles from other layers. All these changes reflected the dynamic acoustic activities of microbubbles inside cancer cell spheroids under ultrasound exposure. However, no PI uptake nor Calcein release correlated with microbubbles was observed, indicating that no changes of cell membrane integrity was induced. The overall shape and structure of the cancer cell spheroid was maintained after ultrasound exposure.

It is noteworthy that after ultrasound exposure some microbubbles exhibited translational movement (e.g., microbubble 1 in Fig. 5B first row), implying that the penetration of cancer cell spheroids in micron-scale might be improved. Fig. 6 shows all the ten microbubbles we detected that changed their positions inside the spheroids after ultrasound exposure. None of them led to cell membrane perforation, assayed by PI and Calcein fluorescent signals. Then these microbubbles must travel along the paths between cells, the fluidic gaps inside cancer cell spheroids. The initial radius of these microbubbles ranged from 0.93 µm to 3.58 µm, reflecting the width of these gaps. The displacement was up to 30.69 µm, reflecting the length of these gaps. Moreover, these gaps were oriented in all possible directions. The microbubble displacement was not correlated with the bubble size shrinkage due to cavitation. The enhanced penetration will definitely benefit therapeutic agent delivery into the core of the cancer cell spheroids and assist in the release of cancer biomolecular markers outside the spheroids into the blood stream, which can be used for diagnosis.

Fig. 6.

Microbubbles that exhibited translational movement after ultrasound exposure. (A) Bright field images before and after ultrasound exposure. (B) Scatter plots of microbubble displacement and initial bubble radius, z position, and bubble radius decrease.

Fig. 7 shows a typical example where the microbubbles were correlated with intracellular PI uptake and concomitant extracellular Calcein release. The intense red fluorescence of PI-nucleic acid complex and the complete loss of Calcein indicated that sonoporation occurred in this cell may result into cell death. After scrutinizing more than 100 microbubbles recorded in 10 cancer cell spheroids, we found that only a few microbubbles induced sonoporation in nearby cells. All of these sonoporated cells exhibited strong PI uptake and significant Calcein decrease. In the in vitro cell culture monolayer, the cell membrane perforation was often associated with cell–cell junction opening [42], [43]. However, inside cell spheroids, no cell–cell connection opening was observed accompanied with cell membrane perforation, which might be due to the compact 3D structure of cell spheroids.

Fig. 7.

A typical example showing the correlation between SonoVue microbubbles, complete extracellular Calcein release and intense intracellular PI uptake due to ultrasound exposure. A superimposed image of the cancer cell spheroid before ultrasound, followed by zoom-in images around the sonoporated cell before and after ultrasound exposure.

We also studied another ultrasound condition, a 1000cycle burst at a pressure of 1.19 MPa. Similar outcomes were observed that most microbubbles did not make any change of cell membrane integrity and a few generated severe cell damage. The unambiguous spatial correlation between microbubbles, PI and Calcein signals implied that the chance for sonoporation-mediated intracellular drug delivery might be very small in cancer cell spheroids. The compact 3D configuration of cancer cell spheroids embedded in a viscoelastic microenvironment leads to much more complicated interactions between cells than conventional 2D cell culture. Moreover, the position relation between cells and microbubbles inside a 3D cell spheroid, where microbubbles diffuse into the fluidic gaps, are dramatically different from that in 2D cell culture, where microbubbles are in contact with cell monolayer statically. Transient and reversible membrane pore formation, assisting intracellular drug delivery, has long been achieved in in vitro cell culture studies, however such exquisite situation (a microbubble in close contact with a cell, a very short ultrasound pulse cavitating the microbubble as well as pushing it towards the cell) may not easily realized in 3D tissue structure. Taken altogether, our results suggest that the immediate impacts of ultrasound and microbubble on cancer spheroids in a 3D tissue environment include improved penetration in micron-scale and sparse direct permanent cancer cell damage. In the future, we will upgrade our 3D cancer tissue model, integrate anticancer therapeutic agents, optimize ultrasound parameters, explore the impacts of ultrasound frequency and power, conduct experiments using longer ultrasound exposure and observe cell responses in long time to detect the secondary responses in cell spheroids as well as immune responses, which have been suggested as a mechanism for the antitumor effect of ultrasound and microbubble treatment in recent studies [44], [45].

4. Conclusion

In this study, we conducted mechanistic investigations of ultrasound and microbubble enhanced cancer therapy at the tissue level with the highlight of microbubble dynamics. The 3D vascularized microfluidic cancer model we designed and assembled enabled SonoVue microbubbles to continuously perfuse in the bottom microfluidic channel (blood vessel), penetrate through the PC porous membrane (leaky tumor vessel wall) and interact with Hela cancer spheroids embedded in agarose gels in the top layer (cancer tissue). The SonoVue microbubble traveling behaviors through the 3D tissue structure were revealed. The SonoVue microbubble cavitation dynamics in 2 %(w/v) agarose gels were resolved at 0.675 M fps frame rate and compared with that in water. The larger microbubble expansion amplitude in agarose gels may be due to the relaxation of the nonlinear viscoelastic cavitation medium. The unambiguous correlation between SonoVue microbubbles, Calcein extracellular release and PI intracellular uptake inside cancer cell spheroids indicated that ultrasound and microbubble treatment can improve cell spheroid penetration in micron-scale and induce sparse direct permanent cell damage. With greater physiological relevance, our mechanistic findings in the 3D vascularized microfluidic cancer model may benefit the clinical translation of ultrasound and microbubble technique.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Pu Zhao: Data curation, Investigation, Visualization. Yingxiao Peng: Investigation, Methodology. Yanjie Wang: Investigation, Methodology. Yi Hu: Data curation, Visualization. Jixing Qin: Resources. Dachao Li: Resources. Kun Yan: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Zhenzhen Fan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This study is supported by the funding from National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFC0107300), National Natural Science Foundation of China (11874280) and the Youth Innovation Promotion Association, Chinese Academy of Sciences (No. 2021023).

Contributor Information

Kun Yan, Email: ydbz@vip.sina.com.

Zhenzhen Fan, Email: zhenzhen.fan@tju.edu.cn.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Chauhan V.P., Martin J.D., Liu H., Lacorre D.A., Jain S.R., Kozin S.V., Stylianopoulos T., Mousa A.S., Han X., Adstamongkonkul P., Popovic Z., Huang P., Bawendi M.G., Boucher Y., Jain R.K. Angiotensin inhibition enhances drug delivery and potentiates chemotherapy by decompressing tumour blood vessels. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:2516. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ji T., Lang J., Wang J., Cai R., Zhang Y., Qi F., Zhang L., Zhao X., Wu W., Hao J., Qin Z., Zhao Y., Nie G. Designing Liposomes To Suppress Extracellular Matrix Expression To Enhance Drug Penetration and Pancreatic Tumor Therapy. ACS Nano. 2017;11:8668–8678. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b01026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baxter L.T., Jain R.K. Transport of fluid and macromolecules in tumors. I. Role of interstitial pressure and convection. Microvasc. Res. 1989;37:77–104. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(89)90074-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dimcevski G., Kotopoulis S., Bjanes T., Hoem D., Schjott J., Gjertsen B.T., Biermann M., Molven A., Sorbye H., McCormack E., Postema M., Gilja O.H. A human clinical trial using ultrasound and microbubbles to enhance gemcitabine treatment of inoperable pancreatic cancer. J. Control. Release. 2016;243:172–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kotopoulis S., Dimcevski G., Gilja O.H., Hoem D., Postema M. Treatment of human pancreatic cancer using combined ultrasound, microbubbles, and gemcitabine: a clinical case study. Med. Phys. 2013;40 doi: 10.1118/1.4808149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Y., Li Y., Yan K., Shen L., Yang W., Gong J., Ding K. Clinical study of ultrasound and microbubbles for enhancing chemotherapeutic sensitivity of malignant tumors in digestive system, Chin. J Cancer Res. 2018;30:553–563. doi: 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2018.05.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kooiman K., Roovers S., Langeveld S.A.G., Kleven R.T., Dewitte H., O'Reilly M.A., Escoffre J.M., Bouakaz A., Verweij M.D., Hynynen K., Lentacker I., Stride E., Holland C.K. Ultrasound-Responsive Cavitation Nuclei for Therapy and Drug Delivery. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2020;46:1296–1325. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2020.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Wamel A., Kooiman K., Harteveld M., Emmer M., ten Cate F.J., Versluis M., de Jong N. Vibrating microbubbles poking individual cells: drug transfer into cells via sonoporation. J. Control. Release. 2006;112:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.P. Prentice, A. Cuschieri, K. Dholakia, M. Prausnitz, P.J.N.p. Campbell, Membrane disruption by optically controlled microbubble cavitation, 1 (2005) 107-110.

- 10.T. Kodama, Y.J.A.p.B. Tomita, Cavitation bubble behavior and bubble–shock wave interaction near a gelatin surface as a study of in vivo bubble dynamics, 70 (2000) 139-149.

- 11.Marmottant P., Hilgenfeldt S. Controlled vesicle deformation and lysis by single oscillating bubbles. Nature. 2003;423:153–156. doi: 10.1038/nature01613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fan Z., Liu H., Mayer M., Deng C.X. Spatiotemporally controlled single cell sonoporation. PNAS. 2012;109:16486–16491. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208198109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Y. Hu, J.M. Wan, C.J.U.i.m. Alfred, biology, Membrane perforation and recovery dynamics in microbubble-mediated sonoporation, 39 (2013) 2393-2405. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Wang M., Zhang Y., Cai C., Tu J., Guo X., Zhang D. Sonoporation-induced cell membrane permeabilization and cytoskeleton disassembly at varied acoustic and microbubble-cell parameters. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:3885. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22056-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu Y., Wei J., Shen Y., Chen S., Chen X. Barrier-breaking effects of ultrasonic cavitation for drug delivery and biomarker release. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023;94 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2023.106346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Cock I., Zagato E., Braeckmans K., Luan Y., de Jong N., De Smedt S.C., Lentacker I. Ultrasound and microbubble mediated drug delivery: acoustic pressure as determinant for uptake via membrane pores or endocytosis. J. Control. Release. 2015;197:20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang T.Y., Choe J.W., Pu K., Devulapally R., Bachawal S., Machtaler S., Chowdhury S.M., Luong R., Tian L., Khuri-Yakub B., Rao J., Paulmurugan R., Willmann J.K. Ultrasound-guided delivery of microRNA loaded nanoparticles into cancer. J. Control. Release. 2015;203:99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Snipstad S., Berg S., Morch Y., Bjorkoy A., Sulheim E., Hansen R., Grimstad I., van Wamel A., Maaland A.F., Torp S.H., Davies C.L. Ultrasound Improves the Delivery and Therapeutic Effect of Nanoparticle-Stabilized Microbubbles in Breast Cancer Xenografts. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2017;43:2651–2669. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2017.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wei Y., Shang N., Jin H., He Y., Pan Y., Xiao N., Wei J., Xiao S., Chen L., Liu J. Penetration of different molecule sizes upon ultrasound combined with microbubbles in a superficial tumour model. J. Drug Target. 2019;27:1068–1075. doi: 10.1080/1061186X.2019.1588279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ho Y.J., Wang T.C., Fan C.H., Yeh C.K. Spatially Uniform Tumor Treatment and Drug Penetration by Regulating Ultrasound with Microbubbles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2018;10:17784–17791. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b05508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sontheimer-Phelps A., Hassell B.A., Ingber D.E. Modelling cancer in microfluidic human organs-on-chips. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2019;19:65–81. doi: 10.1038/s41568-018-0104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dellaquila A., Le Bao C., Letourneur D., Simon-Yarza T. In Vitro Strategies to Vascularize 3D Physiologically Relevant Models. Adv Sci (weinh) 2021;8:e2100798. doi: 10.1002/advs.202100798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.N. Azizipour, R. Avazpour, D.H. Rosenzweig, M. Sawan, A.J.M. Ajji, Evolution of biochip technology: A review from lab-on-a-chip to organ-on-a-chip, 11 (2020) 599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Herland A., Maoz B.M., Das D., Somayaji M.R., Prantil-Baun R., Novak R., Cronce M., Huffstater T., Jeanty S.S.F., Ingram M., Chalkiadaki A., Benson Chou D., Marquez S., Delahanty A., Jalili-Firoozinezhad S., Milton Y., Sontheimer-Phelps A., Swenor B., Levy O., Parker K.K., Przekwas A., Ingber D.E. Quantitative prediction of human pharmacokinetic responses to drugs via fluidically coupled vascularized organ chips. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2020;4:421–436. doi: 10.1038/s41551-019-0498-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.S. Musah, A. Mammoto, T.C. Ferrante, S.S. Jeanty, M. Hirano-Kobayashi, T. Mammoto, K. Roberts, S. Chung, R. Novak, M.J.N.b.e. Ingram, Mature induced-pluripotent-stem-cell-derived human podocytes reconstitute kidney glomerular-capillary-wall function on a chip, 1 (2017) 0069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Y. Zheng, X. Xue, Y. Shao, S. Wang, S.N. Esfahani, Z. Li, J.M. Muncie, J.N. Lakins, V.M. Weaver, D.L.J.N. Gumucio, Controlled modelling of human epiblast and amnion development using stem cells, 573 (2019) 421-425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.K.-J. Jang, M.A. Otieno, J. Ronxhi, H.-K. Lim, L. Ewart, K.R. Kodella, D.B. Petropolis, G. Kulkarni, J.E. Rubins, D.J.S.t.m. Conegliano, Reproducing human and cross-species drug toxicities using a Liver-Chip, 11 (2019) eaax5516. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.H.N.P. Vo, C. Chaiwong, L. Zheng, T.M.H. Nguyen, T. Koottatep, T.T. Nguyen, Algae-based biomaterials in 3D printing for applications in medical, environmental remediation, and commercial products, in: Algae-Based Biomaterials for Sustainable Development, Elsevier, 2022, pp. 185-202.

- 29.H. Heidari, H.J.B. Taylor, Multilayered microcasting of agarose–collagen composites for neurovascular modeling, 17 (2020) e00069.

- 30.P.A. Dayton, K.E. Morgan, A.L. Klibanov, G. Brandenburger, K.R. Nightingale, K.W.J.I.t.o.u. Ferrara, ferroelectrics,, f. control, A preliminary evaluation of the effects of primary and secondary radiation forces on acoustic contrast agents, 44 (1997) 1264-1277.

- 31.C.F. Caskey, S. Qin, P.A. Dayton, K.W.J.T.J.o.t.A.S.o.A. Ferrara, Microbubble tunneling in gel phantoms, 125 (2009) EL183-EL189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.A. Cafarelli, A. Verbeni, A. Poliziani, P. Dario, A. Menciassi, L.J.A.b. Ricotti, Tuning acoustic and mechanical properties of materials for ultrasound phantoms and smart substrates for cell cultures, 49 (2017) 368-378. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Warnez M.T., Johnsen E. Numerical modeling of bubble dynamics in viscoelastic media with relaxation. Phys. Fluids. 1994;27(2015) doi: 10.1063/1.4922598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.A. Jamburidze, Ultrasound-driven dynamics of microbubbles confined in tissue-mimicking phantoms, (2019).

- 35.B. Dollet, P. Marmottant, V.J.A.R.o.F.M. Garbin, Bubble dynamics in soft and biological matter, 51 (2019) 331-355.

- 36.X. Yang, C.C.J.T.J.o.t.A.S.o.A. Church, A model for the dynamics of gas bubbles in soft tissue, 118 (2005) 3595-3606. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.E.-A. Brujan, K. Nahen, P. Schmidt, A.J.J.o.F.M. Vogel, Dynamics of laser-induced cavitation bubbles near an elastic boundary, 433 (2001) 251-281.

- 38.E. Vlaisavljevich, A. Maxwell, M. Warnez, E. Johnsen, C.A. Cain, Z.J.I.t.o.u. Xu, ferroelectrics,, f. control, Histotripsy-induced cavitation cloud initiation thresholds in tissues of different mechanical properties, 61 (2014) 341-352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.D. Baresch, V.J.P.o.t.N.A.o.S. Garbin, Acoustic trapping of microbubbles in complex environments and controlled payload release, 117 (2020) 15490-15496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.J.H. Bezer, H. Koruk, C.J. Rowlands, J.J.J.U.i.M. Choi, Biology, Elastic deformation of soft tissue-mimicking materials using a single microbubble and acoustic radiation force, 46 (2020) 3327-3338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.K. Ferrara, R. Pollard, M.J.A.R.B.E. Borden, Ultrasound microbubble contrast agents: fundamentals and application to gene and drug delivery, 9 (2007) 415-447. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Helfield B., Chen X., Watkins S.C., Villanueva F.S. Biophysical insight into mechanisms of sonoporation. PNAS. 2016;113:9983–9988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606915113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beekers I., Vegter M., Lattwein K.R., Mastik F., Beurskens R., van der Steen A.F.W., de Jong N., Verweij M.D., Kooiman K. Opening of endothelial cell-cell contacts due to sonoporation. J. Control. Release. 2020;322:426–438. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Y. Hu, Y. Mo, J. Wei, M. Yang, X. Zhang, X.J.I.J.o.P. Chen, Programmable and monitorable intradermal vaccine delivery using ultrasound perforation array, 617 (2022) 121595. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.S. Liu, Y. Zhang, Y. Liu, W. Wang, S. Gao, W. Yuan, Z. Sun, L. Liu, C.J.B.J.o.C. Wang, Ultrasound-targeted microbubble destruction remodels tumour microenvironment to improve immunotherapeutic effect, 128 (2023) 715-725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.