Abstract

Background

A high incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in COVID-19 has led to international recommendations for thromboprophylaxis. With limited data on Asian patients with COVID-19, the role of thromboprophylaxis remains unclear.

Objectives

To investigate the in-hospital incidence of VTE in an Asian COVID-19 cohort, describe the VTE trend through successive COVID-19 waves (wild-type, delta, and omicron), and characterize the risk factors for VTE.

Methods

We performed a retrospective observational cohort study of hospitalized COVID-19 adults from January 2020 to February 2022. Objectively confirmed VTE were reviewed to obtain VTE incidence and trend. Subset analysis of critical (intensive care), moderate (oxygen supplementation), and mild cases hospitalized ≥5 days was performed to investigate risk factors and in-hospital hazards of VTE.

Results

Sixteen VTE events occurred among 3574 patients. Overall, VTE incidence was 0.45%, or 0.21% in mild, 3.60% in moderate, and 5.38% in critical infection. The maximum cumulative risk of VTE was 1.14% at 14 days for mild, 8.13% at 21 days for moderate, and 11.55% at 35 days for critical infection. Thromboprophylaxis use in mild, moderate, and critical cases was 5.7%, 28.8%, and 81.7%, respectively. In multivariable analysis, the severity of infection remained the strongest independent predictor of VTE. Compared with mild infection, the relative risk was 8.26 (95% CI, 2.26-30.16) for critical infection and 6.29 (95% CI, 1.54-25.67) for moderate infection.

Conclusion

Overall, VTE incidence in Asian patients with COVID-19 is <1% across successive waves. Patients with moderate and critical infections are at greater risk for VTE and should be considered for routine thromboprophylaxis.

Keywords: Asian, COVID-19, incidence, venous thromboembolism, VTE

Essentials

-

•

Data on the frequency of venous thrombosis in Asian patients with COVID-19 are sparse.

-

•

This Singapore study investigated venous thrombosis during hospitalization for COVID-19.

-

•

Venous thrombosis was infrequent but occurred more often if oxygen or intensive care was needed.

-

•

Measures should be considered to prevent venous thrombosis in Asian patients with more severe COVID-19.

1. Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by SARS-CoV-2, started in Singapore in January 2020 and, by January 2022, had caused more than 2 million infections [1]. Three large waves of infection occurred in this densely populated city-state. The first wave of the wild-type virus peaked in April 2020 and was concentrated among younger male migrant workers living in dormitories [2]. National lockdowns and strict quarantines prevented widespread community transmission until the emergence of the highly transmissible delta variant in April 2021, which was followed by the omicron variant wave in December 2021 [3]. By the first week of January 2022, the omicron variant had rapidly replaced the delta variant as the dominant strain [3,4].

The COVID-19 response in Singapore was centrally coordinated. Initially, anyone who tested COVID-19 positive was either admitted to a hospital or a community care facility. By October 2021, after more than 80% of the population had been vaccinated, a “recover-at-home” policy for low-risk patients was introduced [5]. Hospitalizations were prioritized for severe infections and high-risk individuals such as those with cardiovascular and respiratory disease, diabetes, and immunocompromised states. This resulted in a low overall COVID-19 case fatality rate of <0.1% [1].

COVID-19 leads to systemic coagulation activation and thrombosis [6]. Venous thromboembolism (VTE) rates of 20% to 46% were reported during the pandemic’s early phase and associated with worse outcomes [[7], [8], [9], [10]]. Later and larger population studies supported COVID-19 as a significant risk factor for VTE, but the high initial VTE rates showed a declining trend over time [[11], [12], [13], [14]].

There are limited data on COVID-19 VTE incidence in Asians, especially in East and Southeast Asia. A multicenter Japanese registry study found thrombosis in only 1.87% of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 despite thromboprophylaxis administration in only 43% [15]. Similarly, a 2021 study from Singapore reported a low VTE incidence of 1.8% in intensive care unit (ICU) patients, which contrasted with the high rate of major bleeding of 14.8% [16]. Pre-COVID-19, 2 studies reported lower VTE predisposition among Asian patients [17,18]. Population studies in Korea, Taiwan, and Hong Kong reported VTE rates that are up to 10-fold lower than those in Western countries [[19], [20], [21]]. As most international COVID-19 thromboprophylaxis guidelines recommending universal pharmacological thromboprophylaxis for patients hospitalized with COVID-19 are based on Western data, larger Asian studies of VTE incidence would be relevant to inform thromboprophylaxis practice in this population.

Therefore, our study aimed to determine the incidence of VTE during COVID-19 infection in an Asian cohort and explore the VTE trend and risk factors during time periods of infection caused by the wild-type, delta, and omicron variants.

2. Methods

This retrospective observational cohort study involved patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection in 2 tertiary hospitals in Singapore, the National University Hospital and Alexandra Hospital. The study was granted ethics approval by the Domain Specific Review Board of the National Healthcare Group, Singapore (DSRB No. 2020/00310) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.1. Patients

Patients aged 18 years and above with COVID-19 infection confirmed by positive SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction were included in the study. The protocol during the pandemic was to perform routine COVID-19 testing for all patients at the time of admission and during hospitalization if they developed symptoms of infection. Patients with dates of admission falling within these specific periods were included in the study: (1) 27 January 2020 to 29 May 2020, corresponding to the time of the wild-type virus infection wave; (2) 1 October 2021 to 1 December 2021, corresponding to the delta variant wave; and (3) 1 January 2022 to 15 February 2022, corresponding to the omicron variant wave. All patients with a date of admission falling within the specified periods were evaluated using the data extraction method detailed in section 2.2. Length of hospital stay (LOS) was the number of days between the admission date and the date of discharge or death. Imaging for VTE was performed at the discretion of the treating physician and was generally initiated only in the presence of symptoms suggestive of VTE.

2.2. Data extraction for venous thromboembolism

Data were extracted from the hospital’s electronic medical records database. During the study period, electronic medical records and medication orders were the main modes of clinical documentation and medication ordering. After the total cohort of patients admitted with COVID-19 infection within the specified periods was obtained, the database was searched using 3 approaches to ensure comprehensive identification of all VTE cases in the cohort. These criteria were selected because they were documented to a high degree of fidelity. First, Systemized Nomenclature of Medicine, International Classification of Diseases (ICD), Ninth Revision, and ICD Tenth Revision diagnosis codes were searched for VTE at any anatomical site. Second, service codes for computed tomography pulmonary angiogram, computed tomography scans of any part of the body, and venous Doppler ultrasonography of upper and lower limbs were used to search if these investigations were performed. Third, medication keywords were used to search for any anticoagulant usage. All available anticoagulants in the hospital were screened, ie, unfractionated heparin, low-molecular-weight heparins, rivaroxaban, apixaban, dabigatran, and warfarin. Once the data were available, medical records were manually reviewed to confirm the presence of VTE. Only VTE that occurred on the same day or after the first positive COVID-19 polymerase chain reaction was objectively confirmed by imaging was counted as COVID-19-related VTE. The time to VTE event was the number of days between admission and imaging study, which confirmed VTE. Readmissions within 60 days were screened for any VTE occurrence, but only a VTE event occurring during the primary hospitalization was counted. Service codes for oxygen use and ICU admission were searched to determine infection severity. A manual chart review was performed to ascertain that ICU and oxygen use were related to COVID-19 infection or pneumonia (radiologic findings of pulmonary infiltrates).

2.3. Subset analysis for venous thromboembolism risk factors

Detailed clinical data were extracted for a subset of patients to investigate risk factors for VTE and in-hospital hazards of VTE. All cases of VTE, all moderate and critical infections, and all mild infections with LOS ≥ 5 days (a group for consideration for thromboprophylaxis because of prolonged hospitalization) formed the subset. For this study, cases were categorized into 3 severity levels according to the need for ICU admission or oxygen supplementation: (1) Critical cases that required ICU admission for pneumonia or organ failure as a consequence of or related to COVID-19, (2) Moderate cases that required oxygen supplementation in the presence of COVID-19 pneumonia but did not require ICU admission, and (3) Mild cases that did not require oxygen supplementation nor ICU admission. Clinical data extracted included demographics (age, gender, and ethnicity), comorbid medical conditions (diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, renal disease, lung disease, and vascular diseases such as ischemic heart disease, stroke, and peripheral vascular disease), use of pharmacological VTE prevention, and readmission within 60 days of discharge. Race or ethnic group included those stated on the national registration system as Chinese, Malay, Indian, White, and Others; the latter group was predominantly from Southeast Asia (eg, Thai, Filipino, Myanmese, and Indonesian), South Asia (eg, Bangladeshi and Sri Lankan), and East Asia (eg, Japanese and Korean).

2.4. Pharmacological venous thromboembolism prevention

For this study, patients were considered to have received pharmacological VTE prevention if they received any anticoagulant before the onset of VTE. In order to capture the total anticoagulant status in the cohort, we did not restrict VTE prevention use to the specific purpose of VTE prophylaxis but included any anticoagulant use for other purposes, such as atrial fibrillation or prior arterial or venous thrombosis. Mechanical VTE prophylaxis was not included. VTE prophylaxis was not influenced by this retrospective study, but hospital guidelines for thromboprophylaxis were available to clinicians (Supplementary Data).

2.5. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Version 28.0.1.1. Categorical variables are presented as numbers with percentages, parametric continuous variables are presented as means with SD, and nonparametric continuous variables are presented as medians, IQR, and range. Test for normality was performed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Chi-squared or Fisher exact test was used to compare proportions (categorical data between groups). The Mann–Whitney U-test and Kruskal–Wallis test were used to compare nonparametric continuous data between 2 groups or more than 2 groups, respectively. Univariable analysis of risk factors was performed using 2 × 2 contingency tables for categorical variables or logistic regression for continuous variables and categorical factors with more than 2 categories. Multivariable logistic regression was used to control for covariates and investigate independent risk factors. Time-to-event analysis was performed by competing risk regression according to the method of Fine and Gray using STATA Version 17.0.

3. Results

3.1. Incidence of venous thromboembolism

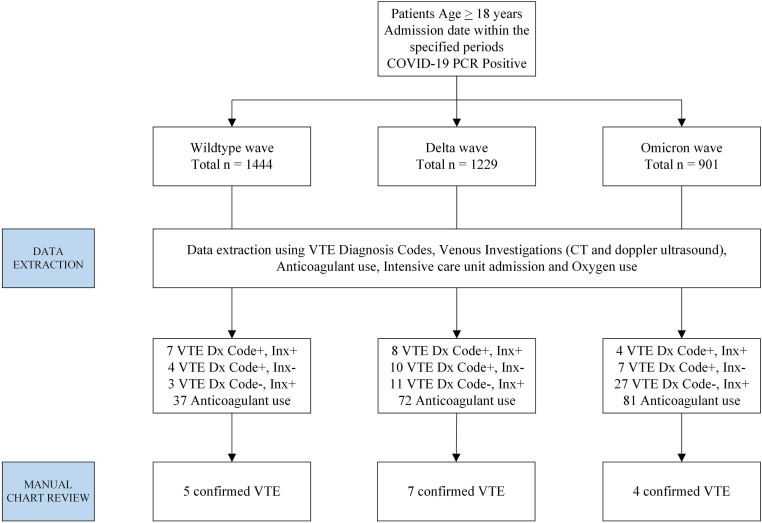

The results of the data extraction process for VTE are shown in Figure 1. During the study period, a total of 3574 patients were admitted: 1444 during the wild-type, 1229 during the delta, and 901 during the omicron variant waves. Sixteen confirmed VTE events were identified among these 3574 patients, with an overall incidence of 0.45%. The number of VTE cases in the corresponding time periods was 5, 7, and 4, with an incidence of 0.35% (3.46 per 1000), 0.57% (5.68 per 1000), and 0.44% (4.44 per 1000), respectively. There was no statistically significant difference in the incidence between the 3 waves (chi-squared, 0.7432; P = .690). The time to a VTE event occurred at a median of 23 days for wild-type (range, 4-35), 13 days for delta (range, 3-21), and 2 days for omicron waves (range, 1-9). Comparing time to VTE between the wild-type and omicron waves was significantly different (P = .015), but the other pairwise comparisons were nonsignificant. The overall incidence of VTE within each severity level was 0.21% in mild, 3.60% in moderate, and 5.38% in critical infection. The proportion of moderate and critical infections was higher during the delta and omicron waves than the wild-type infection wave. The data of these results are summarized in Table 1. The types of VTE encountered were pulmonary embolism in 8 (50.0%) patients, proximal deep vein thrombosis with or without inferior vena cava thrombosis in 5 (31.3%), splanchnic vein thrombosis in 2 (12.5%), and cerebral venous sinus thrombosis in 1 (6.3%). Details of the VTE cases are presented in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Data extraction process, COVID-19 admissions, and confirmed venous thromboembolism during the study period. Period of admission: for the wild-type wave: 27 January 2020 to 29 May 2020; for the delta wave: 1 October 2021 to 1 December 2021; and for the omicron wave: 1 January 2022 to 15 February 2022. Code+, positive for any VTE diagnosis code; CT, computed tomography; Inx+, positive for any venous investigation; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Table 1.

Overall incidence of venous thromboembolism and incidence by severity of infection across the 3 COVID-19 variant waves.

| Variable | Wild-type, n (%)a | Delta, n (%)a | Omicron, n (%)a | Total, n (%)a | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total admissions, N | 1444 | 1229 | 901 | 3574 | ||

| VTE occurrence | 5 (0.35) | 7 (0.57) | 4 (0.44) | 16 (0.45) | .690b | |

| Time to VTE, d median (range) | 23 (4-35) | 13 (3-21) | 2 (1-9) | 9 (1-35) | c | |

| Severity | Mild | 1410 (97.7) | 1146 (93.3) | 814 (90.3) | 3370 (94.3) | <.001b |

| Moderate | 7 (0.5) | 42 (3.4) | 62 (6.9) | 111 (3.1) | ||

| Critical | 27 (1.9) | 41 (3.3) | 25 (2.8) | 93 (2.6) | ||

| VTE occurrence | Mild | 2 (0.14) | 2 (0.17) | 3 (0.37) | 7 (0.21) | <.001d |

| Moderate | 0 (0) | 4 (9.52) | 0 (0) | 4 (3.60) | ||

| Critical | 3 (11.11) | 1 (2.44) | 1 (4.0) | 5 (5.38) | ||

VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Unless otherwise specified.

Chi-squared test comparing proportions of categorical data.

Kruskal–Wallis test comparing time to VTE distribution between the 3 COVID-19 waves: wild-type-omicron P = .015, wild-type-delta P = .336, omicron-delta P = .089 (unadjusted P values).

Chi-squared test comparing the overall incidence by severity level.

Table 2.

Clinical details of patients with venous thromboembolism.

| No. | Age (y)/gender | COVID-19 wave/severity/vaccination status | Comorbid conditions | VTE type/ time to event (d) | Any VTE prophylaxis | Comments | Outcome at discharge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 44/Male | Wild-type/mild/ unvaccinated | Nil | Pulmonary emboli/4 | No | Pulmonary infarct | Alive |

| 2 | 68/Male | Wild-type/critical/unvaccinated | Hypertension | Pulmonary emboli/34 | Yes | COVID pneumonia, multiorgan failure | Died |

| 3 | 58/Female | Wild-type/critical/unvaccinated | Nil | Inferior vena cava thrombus/35 | Yes | COVID myocarditis, ECMO | Alive |

| 4 | 54/Male | Wild-type/critical/unvaccinated | Nil | Pulmonary emboli/23 | Yes | COVID pneumonia, multiorgan failure, ECMO | Alive |

| 5 | 35/Male | Wild-type/mild/ unvaccinated | Asthma | Pulmonary emboli/5 | No | - | Alive |

| 6 | 80/Male | Delta/mild/fully vaccinated | Ischemic heart disease, hypertension, end-stage renal failure | Proximal deep vein thrombosis/13 | No | Remote history of DVT. No VTE prophylaxis due to intestinal bleed | Alive |

| 7 | 37/Female | Delta/moderate/partially vaccinated | Hypertension, cutaneous vasculitis, previous VTE on warfarin | Proximal deep vein thrombosis/2 | No | COVID admission complicated by retroperitoneal hematoma, warfarin withheld | Alive |

| 8 | 51/Male | Delta/moderate/fully vaccinated | Diabetes, hypertension, remote history of provoked distal DVT | Hepatic vein thrombosis/15 | No | Hepatic vein thrombosis related to bacterial liver abscess | Alive |

| 9 | 65/Male | Delta/critical/fully vaccinated | Heart disease, metastatic renal cell carcinoma | Pulmonary emboli/19 | No | Liver failure with thrombocytopenia and prolonged PT | Died |

| 10 | 71/Female | Delta/mild/fully vaccinated | Lymphoma | Proximal deep vein thrombosis, 9 | No | No VTE prophylaxis given thrombocytopenia | Alive |

| 11 | 45/Male | Delta/moderate/unvaccinated | Nil | Pulmonary emboli/2 | No | Moderate COVID infection | Alive |

| 12 | 49/Female | Delta/moderate/ unvaccinated | Diabetes, metastatic endometrial carcinoma | Pulmonary emboli/21 | Yes | History of DVT: received prophylactic dose enoxaparin | Died |

| 13 | 45/Female | Omicron/mild/fully vaccinated | History of CVT, completed warfarin 2 y ago | Cerebral venous thrombosis/1 | No | Seizure due to recurrent CVT, likely precipitated by COVID infection | Alive |

| 14 | 22/Male | Omicron/critical/ fully vaccinated | Newly diagnosed germ cell tumor | Pulmonary emboli/2 | No | PE on the second day postmediastinal surgery | Alive |

| 15 | 63/Female | Omicron/mild/ fully vaccinated | Diabetes, ischemic heart disease, hypertension | Portal vein thrombosis/9 | No | Concurrent liver abscess in addition to COVID infection | Alive |

| 16 | 32/Female | Omicron/mild/partially vaccinated | Inborn error of metabolism | Proximal deep vein thrombosis to inferior vena cava thrombus/1 | No | Leg swelling 3 wk after femoral venous line for non-COVID illness | Alive |

CVT, cerebral venous thrombosis; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; ECMO, extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation; PE, pulmonary embolism; PT, prothrombin time; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

3.2. Clinical data of the predefined subset

The detailed clinical data of the subset of patients for VTE risk factor and in-hospital hazard analysis are shown in Table 3. A total of 1314 patients were identified: 618 during the wild-type, 231 during the delta, and 465 during the omicron variant waves. Patients admitted during the wild-type wave were significantly younger, more often male, and more often belonging to other ethnic groups than patients during the delta and omicron waves. The prevalence of at least one comorbidity and diabetes, heart disease, vascular disease, and kidney disease was significantly greater in patients during delta and omicron waves than the wild-type wave. The proportion of moderate and critical infections was highest during the delta wave. Readmission within 60 days was highest during the omicron variant wave, but there were no VTE readmissions across all 3 time periods.

Table 3.

Demographic, clinical, and comparative data of a predefined subset of patients across the 3 COVID-19 variant waves.

| Variable | Wild-type, n (%)a | Delta, n (%)a | Omicron, n (%)a | Total, n (%)a | P value (3 group comparison) | P value (delta vs omicron) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 618 | 231 | 465 | 1314 | |||

| Age, y median (IQR, range) | 45 (35-51, 19-89) | 70 (57-81, 20-98) | 66 (52-81, 20-99) | 52 (39-69, 19-99) | b | .039 | |

| Gender | Male | 560 (90.6) | 127 (55.0) | 230 (49.5) | 917 (69.8) | <.001 | .170 |

| Female | 58 (9.4) | 104 (45.0) | 235 (50.5) | 397 (30.2) | |||

| Race/ethnicity | Chinese | 123 (19.9) | 163 (70.6) | 296 (63.7) | 582 (44.3) | <.001 | .084 |

| Malay | 14 (2.3) | 24 (10.4) | 87 (18.7) | 125 (9.5) | |||

| Indian | 192 (31.1) | 25 (10.8) | 43 (9.2) | 260 (19.8) | |||

| White | 13 (2.1) | 2 (0.9) | 4 (0.9) | 19 (1.4) | |||

| Other | 276 (44.7) | 17 (7.4) | 35 (7.5) | 328 (25.0) | |||

| LOS, d median (IQR, range) | 8 (6-12, 5-99) | 13 (9-20, 4-91) | 9 (6-14, 1-137) | 9 (6-14, 1-137) | c | <.001 | |

| At least one comorbidity | 155 (25.1) | 99 (42.9) | 194 (41.7) | 448 (34.1) | <.001 | .775 | |

| Diabetes | 62 (10.0) | 36 (15.6) | 71 (15.3) | 169 (12.9) | .015 | .913 | |

| Heart disease (excluding IHD) | 8 (1.3) | 5 (2.2) | 17 (3.7) | 30 (2.3) | .036 | .290 | |

| Vascular disease on antiplatelets (including IHD, stroke, PVD) | 25 (4.0) | 55 (23.8) | 125 (26.9) | 205 (15.6) | <.001 | .383 | |

| Hypertension | 83 (13.4) | 36 (15.6) | 82 (17.6) | 201 (15.3) | .162 | .497 | |

| Kidney disease | 27 (4.4) | 31 (13.4) | 66 (14.2) | 124 (9.4) | <.001 | .781 | |

| Lung disease | 19 (3.1) | 6 (2.6) | 8 (1.7) | 33 (2.5) | .369 | .438 | |

| Readmission within 60 d | 10 (1.6) | 31 (13.4) | 100 (21.5) | 141 (10.7) | <.001 | .010 | |

| Severity of infection | Mild | 584 (94.5) | 148 (64.1) | 378 (81.3) | 1110 (84.5) | <.001 | <.001 |

| Moderate | 7 (1.1) | 42 (18.2) | 62 (13.3) | 111 (8.4) | <.001 | .091 | |

| Critical | 27 (4.4) | 41 (17.7) | 25 (5.4) | 93 (7.1) | <.001 | <.001 | |

| VTE prevention use | Total | 34 (5.5) | 71 (30.7) | 66 (14.2) | 171 (13.0) | <.001 | <.001 |

| Mild | 9 (1.5) | 19 (12.8) | 35 (9.3) | 63 (5.7) | <.001 | .224 | |

| Moderate | 0 (0) | 17 (40.5) | 15 (24.2) | 32 (28.8) | .044 | .078 | |

| Critical | 25 (92.6) | 35 (85.4) | 16 (64.0) | 76 (81.7) | .021 | .045 | |

P values were derived from the Pearson chi-squared test comparing proportions of categorical data and the Mann–Whitney U-test comparing distributions of age and LOS.

IHD, ischemic heart disease; LOS, length of stay; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Unless otherwise specified.

Kruskal–Wallis test comparing age distribution: wild-type-omicron P < .001, wild-type-delta P < .001, delta-omicron P = .041 (adjusted P value).

Kruskal–Wallis test comparing the LOS distribution: wild-type-omicron P = .149, wild-type-delta P < .001, delta-omicron P < .001 (adjusted P value).

Patients who had received VTE prevention were more likely to be female (19.9% vs 10.0%, p < .001), older (odds ratio 1.03; 95% CI, 1.02-1.04), and have comorbid conditions of diabetes (18.3% vs 12.2, P = .027), heart disease (33.0% vs 12.5%, P < .001), and vascular disease (22.4% vs 11.2%, P < .001). Within each stratum of severity, there was a decline in VTE prevention administered during the omicron wave compared with the delta variant wave. Overall, 81.7% of critical, 28.8% of moderate, and 5.7% of mild patients received VTE prevention.

3.3. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism

The results of univariable analysis of risk factors for VTE are shown in Table 4. The risk of VTE was significantly higher with increasing LOS, infection during the delta variant wave, and increasing severity of infection. Compared with mild infection, moderate and critical infections presented a higher relative risk (RR) of VTE (RR, 5.89; 95% CI, 1.70-20.45 for moderate; RR, 8.95; 95% CI, 2.78-28.79 for critical). Gender, age, ethnicity, and comorbidities were nonsignificant risk factors for VTE.

Table 4.

Risk factors for venous thromboembolism by univariable analysis.

| Variable | VTE: No | VTE: Yes | RR | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 908 | 9 | 1.811 | 0.670 | 4.897 | .274a |

| Female | 390 | 7 | |||||

| Any comorbidity | Yes | 439 | 9 | 2.516 | 0.931 | 6.8 | .068a |

| No | 859 | 7 | |||||

| Age, y median (IQR, range) | 52 (39-70, 19-99) | 52 (44-67, 22-80) | 0.996 | 0.970 | 1.023 | .774b | |

| Length of stay, d median (IQR, range) | 9 (6-14, 1-137) | 30 (15-36, 4-99) | 1.047 | 1.028 | 1.066 | <.001b | |

| Race/ethnicityc | Chinese | 571 | 11 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Malay | 123 | 2 | 0.844 | 0.185 | 3.856 | .827b | |

| Indian | 260 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | .994b | |

| White | 18 | 1 | 2.884 | 0.353 | 23.555 | .323b | |

| Other | 326 | 2 | 0.318 | 0.07 | 1.446 | .138b | |

| COVID-19 waved | Wild-type | 613 | 5 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Delta | 224 | 7 | 3.831 | 1.204 | 12.194 | .023b | |

| Omicron | 461 | 4 | 1.064 | 0.284 | 3.983 | .927b | |

| COVID-19 wavee | Omicron | 461 | 4 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Wild-type | 613 | 5 | 0.94 | 0.251 | 3.52 | .927b | |

| Delta | 224 | 7 | 3.602 | 1.043 | 12.431 | .043b | |

| Severityf | Mild | 1103 | 7 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Moderate | 107 | 4 | 5.891 | 1.697 | 20.445 | .005b | |

| Critical | 88 | 5 | 8.953 | 2.784 | 28.788 | <.001b | |

| Severityg | Critical | 88 | 5 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Mild | 1103 | 7 | 0.112 | 0.035 | 0.359 | <0.001b | |

| Moderate | 107 | 4 | 0.658 | 0.171 | 2.525 | 0.542b | |

Bold font signifies a row with a significant P value <.05.

RR, relative risk; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Fisher’s exact test.

Relative risk, 95% CI, and P value from logistic regression.

RR referenced to the Chinese group.

RR referenced to the wild-type strain.

RR referenced to the omicron variant.

RR referenced to mild infection.

RR referenced to critical infection.

Multivariable logistic regression was performed to identify independent risk factors for VTE, and the results are shown in Table 5. Covariates included in the model were age, gender, and the significant factors of univariable analysis (severity of infection and variant wave). The full model containing all predictors was statistically significant with a chi-squared value of 19.875 (dF 6, N = 1314), P = .003. Only the severity of infection remained statistically significant after controlling for all other covariates. The strongest predictor for VTE was critical infection (RR, 8.26; 95% CI, 2.26-30.16), followed by moderate infection (RR, 6.29; 95% CI, 1.54-25.67). There was a trend for age (P = .08), which was nonstatistically significant. COVID-19 variant wave and gender were not independently associated with VTE. Compared with critical infection, moderate infection was not associated with a difference in VTE risk (RR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.19-3.04).

Table 5.

Multivariable logistic regression for independent risk factors for venous thromboembolism.

| Variable | SE | P value | RR | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gendera | 0.563 | 0.614 | 1.328 | 0.441 | 4.000 |

| Age | 0.016 | 0.088 | 0.974 | 0.944 | 1.004 |

| COVID-19 deltab | 0.741 | 0.213 | 2.514 | 0.589 | 10.736 |

| COVID-19 omicronb | 0.776 | 0.979 | 0.980 | 0.214 | 4.487 |

| Severity (moderate)c | 0.717 | 0.010 | 6.294 | 1.543 | 25.671 |

| Severity (critical)c | 0.661 | 0.001 | 8.262 | 2.263 | 30.162 |

| Severity (moderate)d | 0.706 | 0.700 | 0.762 | 0.191 | 3.038 |

Bold font signifies a row with a significant P value <.05.

RR, relative risk.

RR referenced to male gender.

RR referenced to the wild-type strain.

RR referenced to mild infection.

RR referenced to critical infection.

Within each stratum of severity, multivariable logistic regression found that vascular and lung disease appeared to independently predict VTE in mild infection, but confidence intervals were wide (RR, 12.82; 95% CI, 1.43-115.13 and RR, 18.23; 95% CI, 1.42-223.04, respectively). In mild infection, LOS increased the risk of VTE with an RR of 1.08 with each additional day of stay (95% CI, 1.02-1.13; P = .008). Among moderate and critical infections, no independent predictors could be identified.

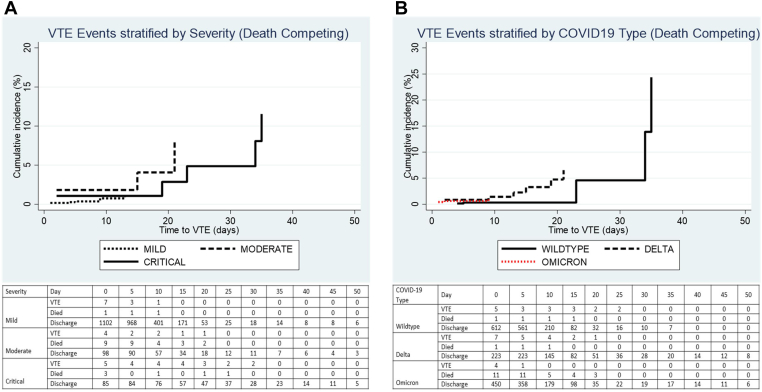

Competing risk regression was performed to determine the cumulative incidence of VTE over time, taking into account death as a competing risk. Figure 2A, B shows the cumulative incidence stratified by severity and COVID-19 type. The maximum cumulative incidence for mild infection was 1.14% at 14 days, 8.13% for moderate infection at 21 days, and 11.55% for critical infection at 35 days (P = .090), as shown in Table 6. For the COVID-19 type, the maximum cumulative incidence for wild-type infection was 24.37% at 35 days, 6.54% for delta infection at 21 days, and 1.06% for omicron at 14 days (P = .366).

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence of in-hospital venous thromboembolism over time stratified by (A) severity of infection and (B) COVID-19 variant wave. (A) Mild vs moderate: sHR 3.44 (95% CI, 0.96-12.29), P = .058; and mild vs critical: sHR 2.85 (95% CI, 0.92-8.77), P = .068. (B) Omicron vs delta: sHR 2.31 (95% CI, 0.68-7.81), P = .177; and omicron vs wild-type: sHR 1.23 (95% CI, 0. 30-5.04), P = .773. sHR, subdistribution hazard ratio; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Table 6.

Cumulative incidence of in-hospital venous thromboembolism in mild, moderate, and critical COVID-19 infection.

| Days after admission | Mild (%) | Moderate (%) | Critical (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7 d | 0.37 | 1.82 | 1.08 |

| 14 d | 1.14 | 1.82 | 1.08 |

| 21 d | 1.14 | 8.13 | 2.85 |

| 28 d | 1.14 | 8.13 | 4.86 |

| 35 d | 1.14 | 8.13 | 11.55 |

4. Discussion

In a predominantly Asian cohort, the overall VTE incidence in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 was <1% during the infection waves caused by the wild-type, delta, and omicron variants but was not insignificant in moderate and critical infection. The incidence of VTE appeared higher during the delta wave but was likely driven by a higher proportion of moderate and critical infections. In the multivariable analysis, the severity of infection independently increased the risk of VTE.

The several differences in the cohort characteristics over time could be explained by the COVID-19 situation in the country. The greater proportions of moderate and severe infections in the delta and omicron waves were likely the consequence of the national COVID-19 admission policy, which enforced mandatory hospital admission for all patients early in the pandemic, followed by a more selective policy during the delta and omicron waves. The shorter time to VTE could be due to the recover-at-home policy in later waves, leading to hospital presentation later into the illness when worsening symptoms developed. The greater proportion of males, younger age, and lower proportion of comorbidities in patients during the wild-type infection wave could be explained by the first pandemic outbreak affecting mostly younger, healthier male migrant workers.

The differences in the incidence in our study compared to others may be due to differences in methodology (eg, prospective vs retrospective, surveillance ultrasound Doppler scans vs symptom-driven investigations), differences in thromboprophylaxis protocols, access to COVID-19 therapeutics, and type of variant. Ethnic differences may also have contributed, as Asian patients are considered to have a lower predisposition to thrombosis, although it is unclear whether it is due to genetic traits or environmental factors [22,23].

The thromboprophylaxis protocol used in our institution was adapted from a consensus protocol provided by the National Steering Group. Standard dose pharmacological VTE prophylaxis was recommended for all patients with critical and severe COVID-19, whereas patients with mild or moderate COVID-19 only received standard dose pharmacologic prophylaxis if they were considered high VTE risk (eg, PADUA score ≥4). Several randomized studies found that higher prophylactic or therapeutic dose anticoagulation reduced death or the need for organ support in moderately ill COVID-19, with the HEP-COVID trial further showing a reduction in VTE incidence (29.0% vs 10.9%, P < .001) [[24], [25], [26]]. Three trials found no beneficial effects on mortality and thrombotic events of intensified dosing in the critically ill, though 1 study, the ANTICOVID trial, showed fewer VTE events (5% vs 18%, P = .002 for high prophylactic; 4% vs 18%, P = .001 for therapeutic) [25,[27], [28], [29]]. As a result, guidelines have varied slightly on the recommendation for intensity of prophylaxis. The International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis recommends therapeutic anticoagulation in select patients, while other guidelines give conditional recommendations with a very low level of certainty for therapeutic over prophylactic-intensity anticoagulation [30,31]. The World Health Organization suggests standard dosing for all hospitalized patients as a conditional recommendation. Based on this, our existing protocol chose to recommend standard-intensity thromboprophylaxis.

Our study observed a low incidence (0.21%) and cumulative risk (1.14%) in mild infection admitted for at least 5 days despite low use of thromboprophylaxis. It could be argued that mild patients would normally not have been admitted in other jurisdictions and would be the population managed without thromboprophylaxis. Moreover, the lack of readmission for VTE within 60 days argues against routine postdischarge thromboprophylaxis, in line with the American Society of Hematology and American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) recommendations [30].

The in-hospital incidence (5.38%) and cumulative risk of VTE (11.55%) were greatest in critical infection despite thromboprophylaxis use in more than 80%. The VTE incidence in our cohort of critically ill patients was 11.1% during infection waves caused by the wild-type strain, which declined to 2.4% with delta and 4.0% with omicron infection waves. In comparison, a meta-analysis conducted early in the pandemic reported a 31% VTE rate in the ICU despite thromboprophylaxis [32,33]. However, our results are comparable to the 13.5% VTE rate from the 2020 Japanese multicenter study [34].

In patients with moderate infection in our study, VTE occurred at a significant rate (3.6%) with up to an 8.13% cumulative risk in relation to thromboprophylaxis use of only 28.8%. This approaches the 4.5% incidence in the 2022 European network study [11]. Moreover, the RR of 6.29 in moderate infection was almost on par with the RR of 8.26 in critical infection. This notable finding could be explained by several factors. First, thromboprophylaxis use in moderate infection was modest. Second, a review of affected patients noted some with a history of cancer, surgery, or prior VTE. This suggests that patients with moderate infection, especially if additional VTE risk factors are present, should be considered for routine VTE thromboprophylaxis.

We did not find gender, age, and time period of infection to be independent predictors for VTE in our cohort as a whole. Within the strata of mild infection, vascular and lung disease and longer LOS may be predictors of VTE. Our results should be taken in the context of published studies evaluating risk factors for VTE. These have reported severity of infection, elevated D-dimer, higher platelet count, older age, liver disease, prior VTE, obesity, male gender, sepsis, and factor V Leiden as predictors of VTE in COVID-19 [6,13,[35], [36], [37]]. One study and 2 meta-analyses were unable to demonstrate cancer as a VTE risk factor in COVID-19; a possible reason could be that the high baseline risk of VTE obscures the risk conferred by cancer [6,35,36]. In 2 studies, vaccination was associated with a lower risk of VTE, and a third reported that vaccinated patients had lower levels of inflammatory markers and D-dimer [35,38,39].

The limitations of our study are as follows: First, this was an observational study, which can be subject to residual confounding inherent to the observational study design. Therapeutic decision-making on thromboprophylaxis was left to the discretion of the attending physicians. The reason for declining rates of VTE prevention over time is unclear but could be related to physician or patient factors. The declining rates of VTE prevention could have obscured any difference in VTE incidence across time. VTE cases in our cohort could have had additional VTE risk factors that could have led to an overestimation of the risk related to COVID-19. Second, the lack of variant genotype data meant that there could be some overlap between the variants in each time period, and our results should be interpreted in terms of infection waves rather than precise variant type. However, national genomic surveillance and published data from the health ministry inform that wild-type, delta, and omicron were the dominant strains in each time period, and accordingly, we extrapolate that patients were highly likely to be infected with the respective strains [4,40]. The effect of the infection time period on the VTE rate is inconclusive from our study due to potential confounding and the low event rate, and the ongoing CORONA-VTE study, which aims to provide a contemporary estimate of event rates, may shed light on this important topic [14]. Third, our study is not designed to provide risk relative to non-COVID-19 illness nor provide information on whether COVID-19 itself is a VTE risk factor in Asian patients. Fourth, our study did not differentiate anticoagulation type and intensity. This could have biased the results toward a lower VTE incidence. Notwithstanding, this would not have materially affected our conclusion that VTE is not negligible in moderate and critical infection. Fifth, there is an inherent chance that deaths due to VTE, which occurred before investigations could be performed, may have been missed. However, we believe that investigations were performed to the fullest extent possible throughout the pandemic, as the national response of pandemic preparedness meant that health care resources were adequately preserved to cope with the cases [41]. Lastly, we could not detect differences between racial/ethnic groups, possibly because the low overall incidence reduced the power to detect minor differences. Our study evaluated a predominantly Chinese and Malay population and should be carefully extrapolated to patients from other countries.

5. Conclusions

In summary, the overall VTE incidence in an Asian cohort with COVID-19 is low across successive waves of infection caused by the 3 major variants but is not insignificant in moderate and critical infection. Our findings suggest that patients with moderate and critical infection should be considered for routine thromboprophylaxis, while with critical infection, breakthrough VTE should be recognized. In mild infection, our data suggest that routine thromboprophylaxis may not be required in the absence of other VTE risk factors. These findings will be useful when formulating thromboprophylaxis guidelines in Asian patients with COVID-19.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Erna Santoso and Shikha Kumari of the National University Health System VDO Office for their assistance in the data extraction process, and Dr Chan Yiong Huak from the Biostatistics Unit, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore for assistance in the competing risk analysis.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

Ethics statement

The study was granted ethics approval by the ethics committee of the Domain Specific Review Board of the National Healthcare Group, Singapore (DSRB No. 2020/00310). The ethics committee granted the study waiver of written consent. Deidentification of data was performed to preserve confidentiality.

Author contributions

S.Y.L., C.Y.L., W.Y.J., and E.S.Y. conceived and designed the study. S.Y.L., W.Y.J., W.Z.Y.T., C.T.L., C.X.Q.L., and S.D.M. collected the data. S.Y.L and C.Y.L. performed the data analysis. S.Y.L. wrote the manuscript. S.Y.L., C.Y.L., and S.D.M. critically revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the editing of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Relationship Disclosure

The authors declare no competing interests.

Data availability

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Footnotes

Handling Editor: Prof. Michael Makris.

The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpth.2023.102218

Supplementary material

References

- 1.WHO Health Emergency Dashboard. WHO (COVID-19). https://covid19.who.int/region/wpro/country/sg; 2023. [accessed January 30, 2023].

- 2.Ngiam J.N., Chhabra S., Goh W., Sim M.Y., Chew N.W.S., Sia C.-H., et al. Continued demographic shifts in hospitalised patients with COVID-19 from migrant workers to a vulnerable and more elderly local population at risk of severe disease. Int J Infect Dis. 2023;127:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2022.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singapore Ministry of Health. COVID-19 Situation Report. https://www.moh.gov.sg/covid-19/testing/situation-report-pdf; 2023 [accessed January 30, 2023].

- 4.Chua F.J.D., Kim S.Y., Hill E., Cai J.W., Lee W.L., Gu X., et al. Co-incidence of BA.1 and BA.2 at the start of Singapore's Omicron wave revealed by Community and University Campus wastewater surveillance. Sci Total Environ. 2023;875 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.162611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Government of Singapore White Paper on Singepore’s response to COVID-19. 2023. https://www.gov.sg/article/covid-19-white-paper WPoSsRtC-PoM [accessed January 30, 2023].

- 6.Nopp S., Moik F., Jilma B., Pabinger I., Ay C. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2020;4:1178–1191. doi: 10.1002/rth2.12439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klok F.A., Kruip M., van der Meer N.J.M., Arbous M.S., Gommers D., Kant K.M., et al. Confirmation of the high cumulative incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19: an updated analysis. Thromb Res. 2020;191:148–150. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Middeldorp S., Coppens M., van Haaps T.F., Foppen M., Vlaar A.P., Müller M.C.A., et al. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1995–2002. doi: 10.1111/jth.14888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang L., Feng X., Zhang D., Jiang C., Mei H., Wang J., et al. Deep vein thrombosis in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: prevalence, risk factors, and outcome. Circulation. 2020;142:114–128. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.046702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helms J., Tacquard C., Severac F., Leonard-Lorant I., Ohana M., Delabranche X., et al. High risk of thrombosis in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:1089–1098. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06062-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burn E., Duarte-Salles T., Fernandez-Bertolin S., Reyes C., Kostka K., Delmestri A., et al. Venous or arterial thrombosis and deaths among COVID-19 cases: a European network cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:1142–1152. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00223-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katsoularis I., Fonseca-Rodríguez O., Farrington P., Jerndal H., Lundevaller E.H., Sund M., et al. Risks of deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and bleeding after covid-19: nationwide self-controlled cases series and matched cohort study. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2022;377 doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-069590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Go A.S., Reynolds K., Tabada G.H., Prasad P.A., Sung S.H., Garcia E., et al. COVID-19 and risk of VTE in ethnically diverse populations. CHEST. 2021;160:1459–1470. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bikdeli B., Khairani C.D., Krishnathasan D., Bejjani A., Armero A., Tristani A., et al. Major cardiovascular events after COVID-19, event rates post-vaccination, antiviral or anti-inflammatory therapy, and temporal trends: rationale and methodology of the CORONA-VTE-Network study. Thromb Res. 2023;228:94–104. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2023.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayashi H., Izumiya Y., Fukuda D., Wakita F., Mizobata Y., Fujii H., et al. Real-world management of pharmacological thromboprophylactic strategies for COVID-19 patients in Japan. JACC: Asia. 2022;2:897–907. doi: 10.1016/j.jacasi.2022.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan C.W., Fan B.E., Teo W.Z.Y., Tung M.L., Shafi H., Christopher D., et al. Low incidence of venous thrombosis but high incidence of arterial thrombotic complications among critically ill COVID-19 patients in Singapore. Thromb J. 2021;19:14. doi: 10.1186/s12959-021-00268-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liao S., Woulfe T., Hyder S., Merriman E., Simpson D., Chunilal S. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in different ethnic groups: a regional direct comparison study. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12:214–219. doi: 10.1111/jth.12464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stein P.D., Kayali F., Olson R.E., Milford C.E. Pulmonary thromboembolism in Asians/Pacific Islanders in the United States: analysis of data from the National Hospital Discharge Survey and the United States Bureau of the Census. Am J Med. 2004;116:435–442. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jang M.J., Bang S.M., Oh D. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in Korea: from the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service database. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:85–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee C.H., Lin L.J., Cheng C.L., Kao Yang Y.H., Chen J.Y., Tsai L.M. Incidence and cumulative recurrence rates of venous thromboembolism in the Taiwanese population. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:1515–1523. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheuk B.L., Cheung G.C., Cheng S.W. Epidemiology of venous thromboembolism in a Chinese population. Br J Surg. 2004;91:424–428. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raskob G.E., Angchaisuksiri P., Blanco A.N., Buller H., Gallus A., Hunt B.J., et al. Thrombosis: a major contributor to global disease burden. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:2363–2371. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee L.H., Gallus A., Jindal R., Wang C., Wu C.C. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in Asian populations: a systematic review. Thromb Haemost. 2017;117:2243–2260. doi: 10.1160/TH17-02-0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lawler P.R., Goligher E.C., Berger J.S., Neal M.D., McVerry B.J., Nicolau J.C., et al. Therapeutic anticoagulation with heparin in noncritically ill patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:790–802. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2105911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spyropoulos A.C., Goldin M., Giannis D., Diab W., Wang J., Khanijo S., et al. Efficacy and safety of therapeutic-dose heparin vs standard prophylactic or intermediate-dose heparins for thromboprophylaxis in high-risk hospitalized patients with COVID-19: the HEP-COVID randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:1612–1620. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.6203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sholzberg M., Tang G.H., Rahhal H., AlHamzah M., Kreuziger L.B., Áinle F.N., et al. Effectiveness of therapeutic heparin versus prophylactic heparin on death, mechanical ventilation, or intensive care unit admission in moderately ill patients with Covid-19 admitted to hospital: RAPID randomised clinical trial. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2021;375:n2400. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n2400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goligher E.C., Bradbury C.A., McVerry B.J., Lawler P.R., Berger J.S., Gong M.N., et al. Therapeutic anticoagulation with heparin in critically ill patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:777–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2103417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sadeghipour P., Talasaz A.H., Rashidi F., Sharif-Kashani B., Beigmohammadi M.T., Farrokhpour M., et al. Effect of intermediate-dose vs standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation on thrombotic events, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation treatment, or mortality among patients with COVID-19 admitted to the intensive care unit: the INSPIRATION randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;325:1620–1630. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.4152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Labbé V., Contou D., Heming N., Megarbane B., Razazi K., Boissier F., et al. Effects of standard-dose prophylactic, high-dose prophylactic, and therapeutic anticoagulation in patients with hypoxemic COVID-19 pneumonia: the ANTICOVID randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2023;183:520–531. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.0456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baumann Kreuziger L., Sholzberg M., Cushman M. Anticoagulation in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Blood. 2022;140:809–814. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021014527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schulman S., Sholzberg M., Spyropoulos A.C., Zarychanski R., Resnick H.E., Bradbury C.A., et al. ISTH guidelines for antithrombotic treatment in COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2022;20:2214–2225. doi: 10.1111/jth.15808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Longchamp G., Manzocchi-Besson S., Longchamp A., Righini M., Robert-Ebadi H., Blondon M. Proximal deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb J. 2021;19:15. doi: 10.1186/s12959-021-00266-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malas M.B., Naazie I.N., Elsayed N., Mathlouthi A., Marmor R., Clary B. Thromboembolism risk of COVID-19 is high and associated with a higher risk of mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;29 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Horiuchi H., Morishita E., Urano T., Yokoyama K. Questionnaire-survey Joint Team on The COVID-19-related thrombosis. COVID-19-related thrombosis in Japan: final report of a questionnaire-based survey in 2020. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2021;28:406–416. doi: 10.5551/jat.RPT001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xie J., Prats-Uribe A., Feng Q., Wang Y., Gill D., Paredes R., et al. Clinical and genetic risk factors for acute incident venous thromboembolism in ambulatory patients with COVID-19. JAMA. 2022;182:1063–1070. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.3858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lobbes H., Mainbourg S., Mai V., Douplat M., Provencher S., Lega J.C. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism in severe COVID-19: a study-level meta-analysis of 21 studies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18 doi: 10.3390/ijerph182412944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Douillet D., Riou J., Penaloza A., Moumneh T., Soulie C., Savary D., et al. Risk of symptomatic venous thromboembolism in mild and moderate COVID-19: a comparison of two prospective European cohorts. Thromb Res. 2021;208:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2021.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang J., Choy K.W., Lim H.Y., Ho P. Laboratory markers of severity across three COVID-19 outbreaks in Australia: has Omicron and vaccinations changed disease presentation? Intern Emerg Med. 2023;18:43–52. doi: 10.1007/s11739-022-03081-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roubinian N.H., Vinson D.R., Knudson-Fitzpatrick T., Mark D.G., Skarbinski J., Lee C., et al. Risk of posthospital venous thromboembolism in patients with COVID-19 varies by SARS-CoV-2 period and vaccination status. Blood Adv. 2023;7:141–144. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2022008984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yau J.W.K., Lee M.Y.K., Lim E.Q.Y., Tan J.Y.J., Tan K., Chua R.S.B. Genesis, evolution and effectiveness of Singapore's national sorting logic and home recovery policies in handling the COVID-19 Delta and Omicron waves. Lancet. 2023;35 doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2023.100719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chua A.Q., Tan M.M.J., Verma M., Han E.K.L., Hsu L.Y., Cook A.R., et al. Health system resilience in managing the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons from Singapore. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.