Abstract

Total synthesis is a field in constant progress. Its practitioners aim to develop ideal synthetic strategies to build complex molecules. As such, they are both a driving force and a showcase of the progress of organic synthesis. In this Perspective, we discuss recent notable total syntheses. The syntheses selected herein are classified according to the key strategic considerations for each approach.

Keywords: Total Synthesis, Natural Products, Biosynthesis, Stereoselectivity, Retrosynthesis

Introduction

Natural product synthesis, the art of building complex molecular architectures using the science of organic chemistry, is often seen as one of the most challenging yet fruitful fields of chemical science. Despite recurrent criticism regarding its supposed decline, it is “as exciting as ever and here to stay”, as stated by Baran.1 Not only is it the testing ground for new methods and strategies in organic synthesis,2 but it also serves the fields of phytochemistry, marine natural products, bacteriology—through structure elucidation3—and medicinal chemistry as the first move in many drug discovery campaigns.4 Moreover, total synthesis could be considered as a showcase of progress made in the field of organic synthesis. For example, in 1994, the group of Shirahama achieved the first enantioselective synthesis of grayanotoxin III in 38 steps and 0.05% overall yield, a real feat at the time (Scheme 1).5 And 28 years later, the group of Luo reported the synthesis of the same molecule in only half the amount of steps and an overall yield 4 times higher (19 steps and 0.2% overall yield).6,7 This spectacular improvement was made possible by multiple advances in organic chemistry, especially regarding asymmetric organocatalysis, cascade reactions, and transition-metal catalysis.

Scheme 1. Evolution of Grayanotoxin III Synthesis.

The past few years have seen many successes in total synthesis, confirming Baran’s statement. The quest for an ideal synthesis has driven organic chemistry practitioners toward designing efficient and elegant strategies.8 The concept of ideality has been defined as the percentage of “productive steps” in the synthetic route, although the same authors clearly indicate that it should not be the sole indicator to judge the quality of a total synthesis.9 Indeed, step count, atom and redox economy, scale, or yield are other key indicators of the efficiency and practicability of a synthesis. Moreover, one could argue that the indicators that should be taken into account to judge the quality of a synthesis might also depend on the synthesis’ purpose. In the synthesis of a potential drug candidate, scalability is more important than it is in a synthesis for structure elucidation purposes. In this Perspective, we will try to highlight recent efficient total syntheses. To focus on modern aspects of the field, we limited ourselves to syntheses published in the last 10 years. This collection is very personal and will by no means be exhaustive. The selected syntheses will be classified in three categories depending on the key considerations: (i) divergent syntheses, in which the most important strategic consideration is to identify the right late intermediate; (ii) semisyntheses, in which the key is to remodel the skeleton of an abundant natural product; and (iii) concise syntheses, in which one or two strategic disconnection allow to greatly simplify the retrosynthesis.

Identifying the Right Common Intermediate: Collective Total Synthesis

The huge diversity of complex natural products that can be considered as interesting targets for total synthesis can look overwhelming. A creative solution to this challenge has been found by using a same strategy to reach various natural products.10 Sometimes termed “divergent synthesis”, “collective synthesis” as defined by MacMillan,11 or “structure-pattern-based synthesis” as phrased by Gaich,12 this approach relies on the identification of a key common intermediate which already bears part of the complexity of a natural product, from which diversity could be accessed in the late stages of the synthesis. These approaches have led to various successes in recent years.

In the context of a total synthesis campaign targeting the Daphniphyllum alkaloids, the group of Li identified a tricyclic structure common to most members of the family as a key intermediate. This could be accessed from known hydroxy enone 1 (easily obtained with high enantiomeric excess in six steps from m-methylanisole).13 The allylic alcohol was substituted by a propargylamide 2 under Mitsunobu conditions followed by formation of an enol ether 3 (Scheme 2). The bridged piperidine ring 4 was formed through a Au- or Ag-catalyzed Conia-ene reaction. Deprotection of the amine, amide coupling, and intramolecular Michael addition allowed the formation of the fused γ-lactam ring 6a or 6b. An important point is the scalability of this synthesis. In all cases, the tricyclic intermediate was obtained on multigram scale, a crucial asset to successfully complete the syntheses. From 6a, a 13 step sequence allowed the formation of daphenylline.14 The key steps were a 6π-electrocyclization/oxidation for the formation of the aromatic ring and Giese addition for the 7-membered ring. On the other hand, a 14 step sequence from 6b led to the formation of daphniyunnine C.15 In this case, the key steps were an intramolecular conjugate addition for the formation of the 7-membered ring, a Lu (3 + 2)-cycloaddition and an intramolecular Horner–Wadsworth–Emmons reaction for the formation of the two fused cyclopentanes. A similar approach was also applied to the synthesis of daphnilongeranin B, daphniyunnine E, dehydrodaphnilongeranin B, and hybridaphniphylline B.16 The strategy was later adapted for the synthesis of daphnipaxianine A and himalenine D.17

Scheme 2. Li’s Divergent Synthesis of Daphniphyllum Alkaloids.

In this work, the identification of an efficient approach for the formation of the tricyclic core common to most Daphniphyllum alkaloids was the key to success and allowed the authors to achieve the synthesis of 8 very complex natural products in an impressively efficient way.

In 2019, the group of Ding reported the synthesis of various cembranoids from the sarcophytin family.18 The synthesis started from known hydroxy enone 7, synthesized in two steps from carvone.19 The hydroxyl moiety was protected prior to a Diels–Alder cycloaddition with Rawal diene 8 (Scheme 3). The resulting cis-decalin 9 reacted with dimethyl carbonate to form the tricyclic core bearing a γ-lactone, which underwent conjugate addition and in situ cyclization under acidic conditions to achieve the fused tetracycle 11. This became the key intermediate for the synthesis of sarcophytin, chatancin, 3-oxochatancin, and pavidolide B. A chemoselective reduction of the enone 11 led to allylic alcohol 12, from which a sequence of exhaustive ketone reduction, Mukaiyama hydration, elimination, transesterification, and oxidation led to the formation of chatancin. On the other hand, from 12, a sequence of Mukaiyama hydration, elimination, and oxidation led to 3-oxochatancin, which could be further epimerized to form sarcophytin. Moreover, this synthesis allowed reassignment of the structure of isosarcophytin as 3-oxochatancin. From 11, performing the Mukaiyama hydration prior to ketone reduction led to the opposite stereoselectivity at C.10 This configuration allowed a semipinacol rearrangement to occur by treatment of 13 with Tf2O in basic conditions, affording the tetracyclic core 14. From there, lactonization and oxidation led to the formation of pavidolide B. Remarkably, the lactonization occurred with inversion of the configuration at the hydroxyl moiety, probably through the formation of a transient cyclopropyl intermediate.

Scheme 3. Ding’s Synthesis of Cembranoids from the Sarcophytin Family.

Overall, Ding’s efficient strategy led to the formation of 4 diverse natural products from the sarcophytin family in 10–11 steps (4–5 steps from key intermediate 11).

In 2021, Zhu and co-workers described a strategy for the synthesis of hasubanan alkaloids with diverse skeletons.20 The strategy relied on a late formation of the fused or bridged pyrrolidine or piperidine ring from a common intermediate. The synthesis started from known aldehyde 15, easily accessible in 3 steps from isovanillin.2115 underwent a one-pot Wacker oxidation/aldol condensation, followed by an O-allylation and Claisen rearrangement, affording naphthalene derivative 16 (Scheme 4). The naphthol moiety could undergo an enantioselective dearomative alkylation using nitro ethene and Takemoto’s catalyst 17. The resulting intermediate could undergo a 5 step sequence involving various reductions and protection of the amine group to form the common intermediate 19. From 19, a Wacker oxidation and aldol condensation afforded cyclopentenone 20, from which oxidation and α-bromination/cyclization led to sinoracutine. On the other hand, a cross metathesis using isopropenylboronic acid pinacol ester followed by Brown oxidation and aldol condensation afforded cyclohexanone 21. The enone could undergo a conjugate addition of the amino group and redox adjustments to complete the synthesis of cepharamine. On the other hand, a series of oxidations, deprotection, and then cyclization afford cepharatine A and C.

Scheme 4. Zhu’s Synthesis of Hasubanan Alkaloids.

In this synthetic sequence, the authors judiciously chose 19 as a common intermediate for both cyclopentenone 20 and cyclohexanone 21, from which the synthesis of various hasubanan alkaloids could be achieved efficiently. It should be noted that the syntheses relied on similar sequences of aldol condensation, oxidations, desaturation, or deprotection after the point of divergence 19, which probably contributed to a quick conclusion of this synthesis.

Following an interest for the mavacuran alkaloid family,22 the group of Vincent recently reported a new approach to access the mavacuran skeleton.23 Unlike previous approaches, this strategy relies on the late formation of the D ring. For that, the tetracyclic structure bearing rings A, B, C, and E was prepared by a Pictet–Spengler reaction between protected tryptamine 22 and aldehyde 23, easily obtained in 3 steps from 4-bromobutene (Scheme 5). After acidic treatment, the dimethyl acetal was deprotected and directly condensed with the indole, affording the tetracyclic intermediate 24. The α,β-unsaturated ester could undergo a 1,4-addition using an organolithium in toluene, an unconventional reactivity that was serendipitously discovered by the authors. The resulting intermediate 26 was the pivotal intermediate of the synthesis. From there, in the case of a PMB-protected amine, the protected primary alcohol could be converted to a primary bromide, which could be substituted by the tertiary amine prior to cleavage of the PMB group, affording 16-epi-pleiocarpamine, which could easily be elaborated into normavacurine, C-mavacurine and C-profluorocurine in a few steps. On the other hand, in the case of a simple methylated amine the primary alcohol could be deprotected, mesylated prior to cyclization and saponification of the ester to lead to taberdivarine H.

Scheme 5. Vincent’s Synthesis of Mavacuran Alkaloids.

Overall, through the identification of pivotal intermediate 26 and the late formation of the D ring, the synthesis of various mavacurane alkaloids could be achieved in a remarkably concise manner.

Later on the same year, the group of Magauer reported a versatile approach for the synthesis of various sesquiterpene alkaloids.24 The flexibility of this synthesis is allowed by the development of a divergent polyene cyclization reaction. The precursor for the polyene cyclization was prepared by assembling farnesyl bromide 27 and indole derivative 28 by lithiation/alkylation, enantioselective dihydroxylation and formation of an epoxide 30 (Scheme 6). Deprotection of the benzenesulfonyl group and bromination at C3 position of the indole allowed to form 31, which upon treatment with BF3·Et2O underwent an uncommon N-terminated polyene cyclization affording a mixture of diastereoisomers 32a an 32b. The former could be oxidized into polysin, while the latter was converted into greenwayodendrin-3-one, greenwayodendrin-3α-ol and polyavolensin. On the other hand, 30 could undergo a more classical C-terminated polyene cyclization by treatment with MsOH in HFIP. The resulting diastereoisomers 33a and 33b could be further elaborated into polyveoline and greenwaylactams A, B and C.

Scheme 6. Magauer’s Divergent Synthesis of Sesquiterpene Alkaloids.

This work is an excellent example showcasing the power of divergent synthesis: a divergent polyene cyclization cascade was developed, allowing access to two different skeletons from common intermediate 30, further leading to the synthesis of 9 natural products.

Beyond the diversity of natural product structures, divergent synthesis can also be applied to reach the chemical space surrounding a specific natural product for medicinal chemistry purposes. In this mindset, Shenvi and co-workers recently reported the synthesis of salvinorin A and various analogs.25 2-Acetoxy-Hagemann’s ester 34, easily accessible in enantioenriched form in 5 steps from methylvinyl ketone and methyl 2-butynoate, underwent a conjugate addition, α-iodinatio,n and Barbier coupling with malondialdehyde dimethylacetal 36 (Scheme 7). After the cleavage of both acetal protecting groups, keto aldehyde 37 was obtained. This intermediate was subjected to chiral phosphoric acid 38 to trigger a one-pot elimination/diastereoselective Robinson annulation to afford tricyclic enone 39. From there, Rh-catalyzed conjugate addition using various boronic acids allowed the synthesis of a diversity of salvinorin analogs 40. Among the synthesized structures, some proved to be more potent than salvinorin A for the inhibition of forskolin-stimulated cAMP accumulation.

Scheme 7. Shenvi’s Synthesis of Salvinorin A Analogs.

The example described above showcases the power of collective synthesis. The key point in this kind of approach is to identify a suitable late intermediate which will bear part of the target’s complexity while allowing access to a diversity of natural products or analogs, as well as an efficient approach to reach this late intermediate.

Identifying the Right Starting Material: Semisynthesis and Skeletal Editing

Semisynthesis is the specific case in which a molecule is synthesized using a natural product as the starting material.26 The flagship example of this approach is docetaxel and paclitaxel semisynthesis from 10-deacetylbaccatin III.27 Beyond classical functionalization of natural products, the emergence of C–C bond activation, rearrangements, and other selective C–C cleavages has led to innovative strategies of skeletal editing. Through those, the synthesis of complex structures from abundant natural products with completely different skeletons has been possible. The advantage of these approaches is the possibility to use a starting material already possessing part of the atoms and the complexity of the target molecule.

In recent years, the Heretsch group engaged in a semisynthesis campaign targeting various rearranged steroid structures starting from ergosterol. The authors use the reversible conversion of ergosterol into its analog with fused cyclopentyl/cyclopropyl rings, usually named i-steroid28 as a way to mask the eastern part of ergosterol while introducing an enone which will serve as chemical handle to further oxidize and edit the western part (Scheme 8).

Scheme 8. Heretsch’s Syntheses of Steroids by Skeletal Rearrangements from Ergosterol.

In 2016, Heretsch described the synthesis of strophasterol A starting from ergosterol.29 After conversion into i-steroid 41, an allylic oxidation led to 42. A series of selective oxidations afforded α-ketol 43 which, upon treatment in basic conditions, underwent a vinylogous α-ketol rearrangement, followed by fragmentation and isomerization. From the resulting intermediate 44, the carboxylic acid moiety was reduced and iodinated, while the eastern part was regenerated by reduction of the ketone and treatment with BF3·Et2O and acetic acid. Iodide 45 underwent a reductive radical cyclization to form cyclopentane ring 46, and further redox ajustments concluded the synthesis of strophasterol A. Later on, the same group applied a similar strategy to the synthesis of aperfloketal A.30 A series of selective oxidations from i-steroid 41 afforded 47, from which a similar vinylogous α-ketol rearrangement/fragmentation/isomerization cascade gave 48. A sequence of esterification, oxidation and deprotection allowed the formation of ketal 49, which further underwent a 3-step sequence involving an anthrasteroid rearrangement as the key step, leading to aperfloketal A.

In 2019, Heretsch and co-workers used i-steroid 41 as an intermediate for the synthesis of matsutakone (pleurocin A).31 A series of redox adjustments led to the formation of vic-diol 50, which could undergo an oxidative cleavage, followed by a formal dioxa-[4 + 2] cycloaddition to afford ketal 51. Further adjustment of the functional groups, including formation of an iodide in place of the ketal and regeneration of the skeleton’s eastern part, led to intermediate 52 bearing a primary iodide and an enone. These would prefigure the key radical cyclization, completing the synthesis of matsutakone.

Finally, in 2020, the same group reported the synthesis of triterpenes with various skeletons.32 From intermediate 42, a one-pot radical 1,2-rearrangement/iodination triggered by PhI(OAc)2 and I2 afforded intermediate 53, which could further be elaborated into dankasterone B and periconiastone A. On the other hand, treating the same intermediate with HgO and I2 allowed a Dowd–Beckwith rearrangement following the 1,2-rearrangement mentioned previously. The resulting structure 54 led to swinhoesterol A after modification of the R chain, selective reductions, and regeneration of the eastern part.

Overall, this total synthesis program allowed the use of a cheap, abundant, although complex starting material, namely, ergosterol, for the synthesis of various rearranged steroids with diverse skeletons. In particular, the strategies rely on the formation of an i-steroid with a key enone moiety which serves as a handle for selective oxidation to further allow skeletal rearrangements.

During the past decade, the group of Maimone reported the synthesis of various sesquiterpenoids from cedrol. These syntheses rely mainly on meticulous studies of the possible C–H oxidations of the cedrol core.33 From cedrol, a Suarez type oxidative cyclization followed by elimination allowed the transfer of the oxygen atom of cedrol onto a remote methyl group (Scheme 9). Oxidative cleavage of the newly formed olefin allowed the formation of 56.34 Oxidation α to the ketone mediated by CuBr2 followed be α-ketol rearrangement and protection of the tertiary alcohol afforded 57. The acid moiety of 57 could direct iron-mediated C–H oxidation to form lactone 58. Finally, a sequence of elimination, deprotection, lactonization, directed dihydroxylation, and inversion of the resulting secondary alcohol afforded pseudoanisatin. On the other hand, from 55, a hydroboration led to secondary alcohol 59 after a sequence of oxidation/reduction necessary to obtain the correct relative configuration.35 Again, a Suarez-type oxidative cyclization allowed the formation of bridged THF structure 60. Treatment with in situ prepared RuO4 allowed remarkable C–C bond cleavage. After a series of redox adjustments and lactonization, the intermediate lactone 62 bearing an α-ketol moiety was obtained. The use of DMDO was crucial for this last oxidation to obtain the desired relative configuration. Intermediate 62 was unstable and could undergo an α-ketol rearrangement. After reduction, the tetracyclic structure 63 was obtained. Acid-mediated elimination of the propellalactone, lactonization, α-hydroxylation, and inversion of configuration of the newly form hydroxyl substituent afforded 64. Finally, directed hydroxylation led to the formation of majucin, which could further undergo a substitution reaction to form the bridged THF structure of jiadifenoxolane A.

Scheme 9. Maimone’s Syntheses of Sesquiterpenoids from Cedrol.

An impressive skeletal remodeling, although starting from a more classical terpene building block, carvone, was described by Sarpong and co-workers and applied to various natural products.36 The isopropylene moiety could undergo an epoxidation, followed by TiIII-mediated reductive cyclization (Scheme 10).37 The resulting synthetic pinene derivative 65 was isolated as a mixture of two separable diastereoisomers. From the minor diastereoisomer 65b, the primary alcohol could be converted into a sulfide, prior to a Rh-catalyzed C–C activation to cleave the C1–C6 bond, leading to a rearranged cyclohexene scaffold 66. This could further be elaborated into various members of the phomactin family.38 On the other hand, the major isomer 65a could undergo an acid-catalyzed semipinacol rearrangement to form camphor-analog 67, which could also be converted into various members of the longiborneol sesquiterpenoid family.39 Starting from (R)-carvone, the same sequence of epoxidation/reductive cyclization led to 65c as the major isomer. From this pinene derivative, a Pd-catalyzed C1–C7 activation followed by cross-coupling with alkenyl iodide 68 led to the formation of polysubstituted cyclohexanone 69.40 This intermediate later led to the synthesis of xishacorene B via a key transannular Giese cyclization to form the bridged structure. Finally, synthetic pinene derivative 65c could also be subjected to a Pd-catalyzed C–C activation/cross-coupling/Mizoroki–Heck cyclization with 1,1-dichloro alkene 70.41 The resulting bicyclo[2.2.2]octane was a key intermediate in the synthesis of 14- and 15-hydroxypatchoulol.

Scheme 10. Sarpong’s Skeletal Editing from Carvone.

Directed evolution offers new exciting perspectives for the formation of complex structures.42 In 2020, the group of Renata reported the selective C3 hydroxylation of sesquiterpene lactone sclareolide using a P450BM3 variant.43 From this cheap and abundant starting material, added value hydroxylated product 72 could be obtained efficiently on gram-scale (Scheme 11). Protection of the secondary alcohol, hydroxylation to the lactone, reduction, and oxidative cleavage allowed the formation of 73 bearing an aldehyde and secondary alcohol as chemical handles for the construction of meroterpenoids phenylpyropene C and arisugacin F. Although very powerful, the use of this P450BM3 variant was limited to few substrates. The same authors had to develop a new variant to perform efficiently the selective oxidation of 74, easily obtained in three steps from sclareolide.44 The resulting intermediate 75 could be coupled with iodide 76 through a zincation/conjugate addition. The resulting advanced intermediate 77 was then converted to gedunin in an 8-step sequence.

Scheme 11. Renata’s Selective Hydroxylation of Sclareolide Derivatives.

These selected examples highlight the importance of finding the right starting material in synthesis. Starting from cheap, abundant, although complex structures such as sclareolide or ergosterol, the synthesis of various complex natural products could be achieved very efficiently.

Identifying the Right Key Step(s) For Concise Syntheses

The design of a synthetic strategy uses retrosynthetic analysis, the rules of which were established decades ago by Corey. The idea is to identify key disconnections to make the synthesis as concise and efficient as possible.45 In recent years, the rise of AI and computer assistance allowed to simplify the reflection necessary to set up a strategy and opened new avenues for organic synthesis, especially using the software Chematica.46 Nevertheless, various recent examples can be cited to show that an old-fashion blackboard design of a retrosynthesis can still lead to success.

In 2016, the group of Maimone reported an efficient synthesis of 6-epi-ophiobolin N.47 The ophiobolins are a family of complex sesterterpenoids displaying a 5–8–5 fused ring system with many stereogenic centers. Maimone’s hypothesis was that the tetracyclic core could be constructed by radical cyclization. This approach would have two main advantages: (i) the substrate for this key cyclization could be easily accessed from common terpenic precursors such as farnesol and linalool and (ii) after the key cyclization all the stereogenic centers would be set and most functional groups would be at hand’s reach.

The synthesis began by an enantioselective Charette cyclopropanation of farnesol followed by iodination to form 79 (Scheme 12). This was assembled with precursor 80 (easily prepared in 3 steps from linalool) by a one-pot lithiation/transmetalation/conjugate addition/trapping with trichloroacetyl chloride. After reduction of the ketone and protection, a precursor for the key radical cyclization 81 was obtained. The key cyclization was achieved using a chiral thiol catalyst 82 developed for this purpose, Et3B and air as the radical initiator and TMS3SiH as the hydrogen radical source. The tricyclic structure 83 was obtained as a mixture of diastereoisomers at C14 and C15, which could be separated in later stages of the synthesis. From 83, a sequence of Corey-Chaykovsky epoxidation, reductive opening of the expoxide, Swern oxidation and elimination of the tertiary alcohol concluded the synthesis of 6-epi-ophiobolin N in 10 steps (longest linear sequence). A few years later, the same authors applied a similar strategy to the synthesis of 6-epi-ophiobolin A.48

Scheme 12. Maimone’s Synthesis of 6-epi-Ophiobolin N.

Overall, this work by Maimone led to a very efficient synthesis of the C6-epimer of natural ophiobolin N in only 10 steps. This was possible thanks to the identification and development of a key radical cyclization to form the tricyclic structure but also to a smart experimental design in which many concession steps are performed in the same pot as constructive steps.

In 2020, the group of Soós reported an expeditious synthesis of minovincine and aspidofractinine.49 The synthesis relied on quick access to a tricyclic core, followed by late formation of the indole moiety. Enone 84 and malonate derivative 85, respectively prepared in 2 and 1 step from commercial precursors, where assembled by an enantioselective Robinson annulation using organocatalyst 86 (Scheme 13). The reaction afforded cyclohexenone 87 in a good yield and excellent enantioselectivity. Cyclohexenone 87 underwent a cascade of nucleophilic substitutions and conjugate addition in the presence of 2-chloroethylamine, affording the tricyclic core 88. Remarkably, this intermediate could be prepared on a 59 g scale. From there, a sequence of decarboxylation, Fischer indolization, methoxycarbonylation, and selective ketone formation led to the formation of minovincine. On the other hand, starting by the methyl ketone formation followed by decarboxylation allowed an interrupted Fischer indolization to build the bridged structure of aspidofractine. The synthesis was concluded by a Wolff–Kishner reduction of the bridged ketone.

Scheme 13. Soós’ Synthesis of Minovincine and Aspidofractinine.

In this work, Soós and co-workers achieved a straightforward synthesis of minovincine and aspidofractinine in 8 steps. This was made possible by the quick formation of a tricyclic core using an organocatalytic Robinson annulation and a nucleophilic cascade. The power of this synthesis was showcased by the synthesis of more than 1 g of minovincine.

In 2021, the group of Gaich tackled the synthesis of pepluanol A using a key intramolecular Diels–Alder cycloaddition (IMDA).50 The synthesis used bicyclic precursor 89, easily prepared in 5 steps from carene using a procedure previously described by Baran,51 and aldehyde 90, prepared in 5 steps from (S)-3-bromo-2-methylpropanol (Scheme 14). These fragments were assembled by a Nozaki–Hiyama–Kishi reaction, affording a mixture of diastereoisomers at C1 and C13. While the minor diastereoisomer at C1 could be separated by column chromatography, separating the C13-epimers proved to be irrelevant. Indeed, after TES protection of the secondary alcohol, the IMDA reaction proceeded in a diastereoconvergent fashion in the presence of DBU. Nevertheless, the product had the undesired configuration at C13 and the authors had to epimerize it in situ by treatment with LDA. The tetracyclic intermediate 92 was then converted into pepluanol A by a sequence of 3 selective oxidations. Thus, the synthesis of pepluanol A was achieved in 10 steps from commercially available precursors.

Scheme 14. Gaich’s Synthesis of Pepluanol A.

In 2022, our group reported the first enantioselective synthesis of lucidumone.52 Our strategy relied on a quick assembly of the pentacyclic scaffold using a retro-[4 + 2]/CO2 extrusion/IMDA cascade. The precursor for this key step was synthesized from indanedione 93 and bridged bicyclic lactone 94, respectively, synthesized in 4 and 5 steps from commercially available material (Scheme 15). In particular, 94 was made enantioselectively using an inverse electron demand Diels–Alder cycloaddition involving a 2-pyrone.53,54 The fragments were assembled under Mitsunobu conditions to form 95, from which the key retro-[4 + 2]/CO2 extrusion/IMDA cascade afforded 96 with the pentacyclic structure of lucidumone. A six-step sequence allowed conversion of the methyl ester into a methyl ketone, reduction of the endocyclic olefin, and cleavage of the protecting groups to conclude this synthesis in 13 steps (longest linear sequence). Remarkably, 1.6 g of the natural product was synthesized in one batch by using this approach.

Scheme 15. de la Torre’s Synthesis of Lucidumone.

In 2022, the team of Carreira reported an elegant synthesis of aberrarone.55 In particular, Carreira’s approach features an impressive Au-catalyzed cyclization cascade based on previous studies by Fensterbank and co-workers.56 Precursors 97 and 98, easily obtained in 7 steps from pantolactone and Roche ester respectively, were assembled by a Sonogashira coupling (Scheme 16). After oxidation of the primary alcohol, precursor 99 was obtained. This could undergo the key Meyer–Schuster/Nazarov cascade, followed by an intramolecular cyclopropanation and aldol reaction to reach the skeleton of aberrarone 100. From there, redox adjustments allowed completion of the synthesis in 15 steps.

Scheme 16. Carreira and Jia’s Syntheses of Aberrarone.

A few months later, the group of Jia reported a different synthesis of the same natural product.57 Jia’s approach involved intermediates 101 and 102, synthesized in 2 steps from commercial compounds. The fragments were assembled by Ni-catalyzed reductive cross coupling to afford 103. Oxidation of the allylic alcohol and α-acylation allowed the formation of 105, the precursor for the key cyclization. After treatment with Mn(OAc)3, 105 underwent a radical cascade leading to the tetracyclic core of aberrarone 106. Final redox adjustments concluded this synthesis in 12 steps.

While both approaches employ an impressive cascade cyclization to form the tetracyclic structure, Jia’s approach proved to be slightly shorter. The main advantage of this second approach lies in the quick formation of fragments 101 and 102.

In an effort to find the shortest possible synthesis, biosynthetic considerations are often very valuable.58 In this context, Trauner and co-workers recently reported an impressive biomimetic synthesis of preuisolactone A produced by the endophytic fungus Preussia isomera.59 Trauner’s hypothesis was that preuisolactone A was formed in the plant from catechol 107 and pyrogallol 108 by oxidation/(5 + 2)-cycloaddition followed by a series of cyclizations, fragmentations, and rearrangements. With this in mind, the authors treated precursors 107 and 108 in oxidative conditions and obtained the bridged tricyclic intermediate 109 in equilibrium with its lactol form 110 (Scheme 17). The equilibrium could be displaced toward 109 by treatment in basic conditions followed by acidic workup. Treatment with Koser’s reagent allowed an oxidative cyclization, followed by a cascade lactol formation/α-ketol rearrangement, affording preuisolactone A in 57%. This very straightforward synthesis (3 steps) could support the author’s biosynthetic proposal.

Scheme 17. Trauner’s Biomimetic Synthesis of Preuisolactone A.

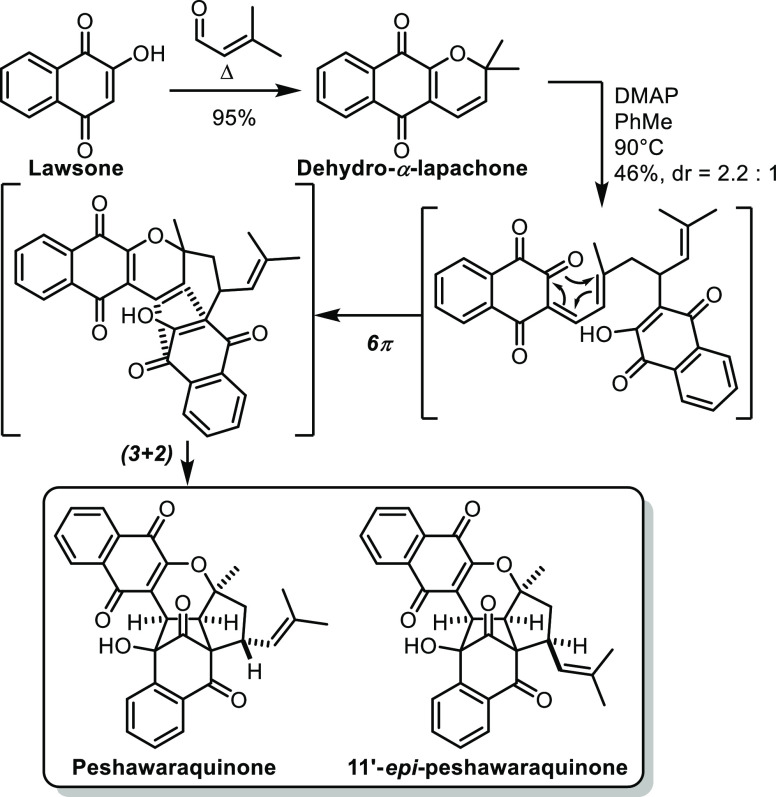

With a similar mindset, the groups of George and Lawrence recently studied the biosynthesis of peshawaraquinone, a complex polycyclic meroterpenoid isolated from the tree Fernandoa adenophylla.60 The hypothesis was that peshawaraquinone was formed by unsymmetrical dimerization starting from dehydro-α-lapachone, a meroterpenoid commonly encountered in these trees. To prove this, the authors first synthesized dehydro-α-lapachone from lawsone by a one-pot Knoevenagel condensation and subsequent oxa-6π-electrocyclization (Scheme 18). Then, dehydro-α-lapachone was treated with DMAP in toluene. After 6π-electrocyclic ring opening and intermolecular Michael addition, followed by 6π electrocyclization and intramolecular (3 + 2)-cycloaddition, peshawaraquinone was obtained along with its C11’ epimer. Interestingly, when DMAP was replaced with DIPEA, the diastereomeric ratio was reversed. This one-step synthesis of peshawaraquinone from dehydro-α-lapachone could back the author’s biosynthetic proposal, while providing a convenient approach in the lab.

Scheme 18. George and Lawrence’s Synthesis of Peshawaraquinone.

Overall, in this final section, we selected various examples of old-fashioned retrosynthetic design leading to particularly efficient syntheses. A key lesson to take from this collection is the importance of cascade reaction and cycloadditions, or more generally reactions involving multiple bond formation. Through the identification of such key steps, the authors are often able to achieve concise syntheses (even allowing the use of various “concession steps”).

Conclusion

The field of total synthesis still has a rosy future. In this Perspective, we have highlighted selected recent achievements in this field. We have tentatively organized them depending on the key strategic question that was tackled in each of these approaches. Some of them dealt with flexibility, through the identification of a key intermediate allowing access to a diversity of targets in the context of collective synthesis. Others blew a wind of change on semisynthesis, offering unexpected and exciting skeletal remodeling to reach complex targets from already complex but abundant starting materials. Finally, some of them were about simplicity: finding the right disconnection in a classical retrosynthetic design to allow concise approaches toward complex structures. While every synthesis work described above has its own strong point, none of them is perfect. This perpetual search for perfection is what brings the field of organic synthesis forward and the reason why it still has good days ahead.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Agence Nationale de la Recherche, Université Paris-Saclay and Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) for funding.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AIBN

azobis(isobutyronitrile)

- cAMP

cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- COD

cyclooctadiene

- DBU

1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene

- DDQ

2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone

- DIAD

diisopropyl azodicarboxylate

- DIPEA

N,N-diisopropylethylamine

- DMAP

4-dimethylaminopyridine

- DMDO

dimethyldioxirane

- DMS

dimethylsulfide

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- EDC

1-ethyl-3-(3-(dimethylamino)propyl)carbodiimide

- HFIP

hexafluoroisopropanol

- HMPA

hexamethylphosphoramide

- IBX

2-iodoxybenzoic acid

- IMDA

intramolecular Diels–Alder

- LDA

lithium diisopropylamide

- mCPBA

meta-chloroperbenzoic acid

- MMPP

magnesium monoperoxyphthalate

- MOM

methoxymethyl

- NIS

N-iodosuccinimide

- PCC

pyridinium chlorochromate

- PDC

pyridinium dichromate

- PMB

para-methoxybenzyl

- PTSA

para-toluenesulfonic acid

- TBDPS

tert-butyldiphenylsilyl

- TBS

tert-butyldimethylsilyl

- TES

triethylsilyl

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- THF

tetrahydrofuran

- TMEDA

tetramethylethylenediamine

- TMS

trimethylsilyl

- TPS

triphenylsilyl

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article.

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

N.F.’s PhD was funded by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR JCJC grant SynCol, ANR-19-CE07-0005).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Special Issue

Published as part of the ACS Organic & Inorganic Au virtual special issue “2023 Rising Stars in Organic and Inorganic Chemistry”.

References

- Baran P. S. Natural Product Total Synthesis: As Exciting as Ever and Here To Stay. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 4751–4755. 10.1021/jacs.8b02266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisman S. E.; Maimone T. J. Total Synthesis of Complex Natural Products: More Than a Race for Molecular Summits. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 1815–1816. 10.1021/acs.accounts.1c00184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Nay B. Total synthesis: an enabling science. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2023, 19, 474–476. 10.3762/bjoc.19.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Nicolaou K. C.; Snyder S. A. Chasing Molecules That Were Never There: Misassigned Natural Products and the Role of Chemical Synthesis in Modern Structure Elucidation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 1012–1044. 10.1002/anie.200460864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Shen S.-M.; Appendino G.; Guo Y.-W. Pitfalls in the structural elucidation of small molecules. A critical analysis of a decade of structural misassignments of marine natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2022, 39, 1803–1832. 10.1039/D2NP00023G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Nicolaou K. C. Joys of Molecules. 2. Endeavors in Chemical Biology and Medicinal Chemistry. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 5613–5638. 10.1021/jm050524f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Nicolaou K. C.; Rigol S. Total Synthesis in Search of Potent Antibody–Drug Conjugate Payloads. From the Fundamentals to the Translational. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 127–139. 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan T.; Hosokawa S.; Nara S.; Oikawa M.; Ito S.; Matsuda F.; Shirahama H. Total Synthesis of (−)-Grayanotoxin III. J. Org. Chem. 1994, 59, 5532–5534. 10.1021/jo00098a009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kong L.; Yu H.; Deng M.; Wu F.; Jiang Z.; Luo T. Enantioselective Total Syntheses of Grayanane Diterpenoids: (−)-Grayanotoxin III, (+)-Principinol, E, and (−)-Rhodomollein XX. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 5268–5273. 10.1021/jacs.2c01692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For a critical review on the evolution grayanane total synthesis, see:; Fay N.; Blieck R.; Kouklovsky C.; de la Torre A. Total synthesis of grayanane natural products. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2022, 18, 1707–1719. 10.3762/bjoc.18.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Kuttruff C. A.; Eastgate M. D.; Baran P. S. Natural product synthesis in the age of scalability. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2014, 31, 419–432. 10.1039/C3NP70090A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Hernandez L. W.; Sarlah D. Empowering Synthesis of Complex Natural Products. Chem.—Eur. J. 2019, 25, 13248–13270. 10.1002/chem.201901808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Gaich T.; Baran P. S. Aiming for the Ideal Synthesis. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 4657–4673. 10.1021/jo1006812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Peters D. S.; Pitts C. R.; McClymont K. S.; Stratton T. P.; Bi C.; Baran P. S. Ideality in Context: Motivations for Total Synthesis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 605–617. 10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostaki E. E.; Zografos A. L. Common synthetic scaffolds” in the synthesis of structurally diverse natural products. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 5613–5625. 10.1039/c2cs35080g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S. B.; Simmons B.; Mastracchio A.; MacMillan D. W. C. Collective synthesis of natural products by means of organocascade catalysis. Nature 2011, 475, 183–188. 10.1038/nature10232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlinger C. K. G.; Gaich T. Structure-Pattern-Based Total Synthesis. Chem.—Eur. J. 2019, 25, 10782–10791. 10.1002/chem.201901308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piers E.; Oballa R. M. Concise Total Syntheses of the Sesquiterpenoids (−)-Homalomenol A and (−)-Homalomenol B. J. Org. Chem. 1996, 61, 8439–8447. 10.1021/jo961605+. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z.; Li Y.; Deng J.; Li A. Total synthesis of the Daphniphyllum alkaloid daphenylline. Nat. Chem. 2013, 5, 679–684. 10.1038/nchem.1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Zhang W.; Zhang F.; Chen Y.; Li A. Total Synthesis of Daphniyunnine C (Longeracinphyllin A). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 14893–14896. 10.1021/jacs.7b09186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W.; Ding M.; Li J.; Guo Z.; Lu M.; Chen Y.; Liu L.; Shen Y.-H.; Li A. Total Synthesis of Hybridaphniphylline B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 4227–4231. 10.1021/jacs.8b01681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.; Zhang W.; Ren L.; Li J.; Li A. Total Syntheses of Daphenylline, Daphnipaxianine A, and Himalenine D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 952–956. 10.1002/anie.201711482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He C.; Xuan J.; Rao P.; Xie P.-P.; Hong X.; Lin X.; Ding H. Total Syntheses of (+)-Sarcophytin, (+)-Chatancin, (−)- 3-Oxochatancin, and (−)-Pavidolide B: A Divergent Approach. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 5100–5104. 10.1002/anie.201900782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P.-P.; Yan Z.-M.; Li Y.-H.; Gong J.-X.; Yang Z. Enantioselective Total Synthesis of (−)-Pavidolide B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 13989–13992. 10.1021/jacs.7b07388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G.; Wang Q.; Zhu J. Unified divergent strategy towards the total synthesis of the three sub-classes of hasubanan alkaloids. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 36. 10.1038/s41467-020-20274-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W.; Liu J.; Zhang H. Total synthesis of pulverolide: revision of its structure. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010, 51, 4874–4876. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2010.07.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Jarret M.; Tap A.; Kouklovsky C.; Poupon E.; Evanno L.; Vincent G. Bioinspired Oxidative Cyclization of the Geissoschizine Skeleton for the Total Synthesis of (−)-17-nor-Excelsinidine. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 12294–12298. 10.1002/anie.201802610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Jarret M.; Turpin V.; Tap A.; Gallard J.-F.; Kouklovsky C.; Poupon E.; Vincent G.; Evanno L. Bioinspired Oxidative Cyclization of the Geissoschizine Skeleton for Enantioselective Total Synthesis of Mavacuran Alkaloids. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 9861–9865. 10.1002/anie.201905227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Jarret M.; Tap A.; Turpin V.; Denizot N.; Kouklovsky C.; Poupon E.; Evanno L.; Vincent G. Bioinspired Divergent Oxidative Cyclizations of Geissoschizine: Total Synthesis of (−)-17-nor-Excelsinidine, (+)-16-epi-Pleiocarpamine, (+)-16-Hydroxymethyl-Pleiocarpamine and (+)-Taberdivarine H. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 2020, 6340–6351. 10.1002/ejoc.202000962. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Jarret M.; Abou-Hamdan H.; Kouklovsky C.; Poupon E.; Evanno L.; Vincent G. Bioinspired Early Divergent Oxidative Cyclizations toward Pleiocarpamine, Talbotine, and Strictamine. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 1355–1360. 10.1021/acs.orglett.1c00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauger A.; Jarret M.; Tap A.; Perrin R.; Guillot R.; Kouklovsky C.; Gandon V.; Vincent G. Collective Total Synthesis of Mavacuran Alkaloids through Intermolecular 1,4-Addition of an Organolithium Reagent. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202302461 10.1002/anie.202302461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plangger I.; Pinkert T.; Wurst K.; Magauer T. A Divergent Polyene Cyclization for the Total Synthesis of Greenwayodendrines, Greenwaylactams, Polysin and Polyveoline. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202307719 10.1002/anie.202307719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill S. J.; Dao N.; Dang V. Q.; Stahl E. L.; Bohn L. M.; Shenvi R. A. A Route to Potent, Selective, and Biased Salvinorin Chemical Space. ACS Cent. Sci. 2023, 9, 1567–1574. 10.1021/acscentsci.3c00616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Nising C. F.; Bräse S. Highlights in Steroid Chemistry: Total Synthesis versus Semisynthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 9389–9391. 10.1002/anie.200803720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Majhi S.; Das D. Chemical derivatization of natural products: Semisynthesis and pharmacological aspects- A decade update. Tetrahedron 2021, 78, 131801. 10.1016/j.tet.2020.131801. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Wang Z.; Hui C. Contemporary advancements in the semi-synthesis of bioactive terpenoids and steroids. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2021, 19, 3791–3812. 10.1039/D1OB00448D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Liao J.-X.; Hu Z.-N.; Liu H.; Sun J.-S. Advances in the Semi-Synthesis of Triterpenoids. Synthesis 2021, 53, 4389–4408. 10.1055/a-1543-9719. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Denis J. N.; Greene A. E.; Guénard D.; Guéritte-Voegelein F.; Mangatal L.; Potier P. A Highly Efficient, Practical Approach to Natural Taxol. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 5917–5919. 10.1021/ja00225a063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Holton R. A.Method for Preparation of Taxol. EP 0400971 A2, 1990.; c Ojima I.; Habus I.; Zhao M.; Zucco M.; Park Y. H.; Sun C. M.; Brigaud T. New and Efficient Approaches to the Semisynthesis of Taxol and Its C-13 Side Chain Analogs by Means of b-Lactam Synthon Method. Tetrahedron 1992, 48, 6985–7012. 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)91210-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Hosoda H.; Yamashita K.; Chino N.; Nambara T. Synthesis of 15α-hydroxylated dehydroepiandrosterone and androstenediol. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1976, 24, 1860–1864. 10.1248/cpb.24.1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b McMorris T. C.; Patil P. A. Improved synthesis of 24-epibrassinolide from ergosterol. J. Org. Chem. 1993, 58, 2338–2339. 10.1021/jo00060a063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heinze R. C.; Lentz D.; Heretsch P. Synthesis of Strophasterol A Guided by a Proposed Biosynthesis and Innate reactivity. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 11656–11659. 10.1002/anie.201605752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alekseychuk M.; Heretsch P. Chemical Emulation of the Biosynthetic Route of Anthrasteroids: Synthesis of Aperfloketal A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 21867–21871. 10.1021/jacs.2c10735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinze R. C.; Heretsch P. Translation of a Polar Biogenesis Proposal into a Radical Synthetic Approach: Synthesis of Pleurocin A/Matsutakone and Pleurocin B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 1222–1226. 10.1021/jacs.8b13356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duecker F. L.; Heinze R. C.; Heretsch P. Synthesis of Swinhoeisterol A, Dankasterone A and B, and Periconiastone A by Radical Framework Reconstruction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 104–108. 10.1021/jacs.9b12899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung K.; Condakes M. L.; Novaes L. F. T.; Harwood S. J.; Morikawa T.; Yang Z.; Maimone T. J. Development of a Terpene Feedstock-Based Oxidative Synthetic Approach to the Illicium Sesquiterpenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 3083–3099. 10.1021/jacs.8b12247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung K.; Condakes M. L.; Morikawa T.; Maimone T. J. Oxidative Entry into the Illicium Sesquiterpenes: Enantiospecific Synthesis of (+)-Pseudoanisatin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 16616–16619. 10.1021/jacs.6b11739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condakes M. L.; Hung K.; Harwood S. J.; Maimone T. J. Total Syntheses of (−)-Majucin and (−)-Jiadifenoxolane A, Complex Majucin-type Illicium Sesquiterpenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 17783–17786. 10.1021/jacs.7b11493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lusi R. F.; Perea M. A.; Sarpong R. C–C Bond Cleavage or α-Pinene Derivatives Prepared from Carvone as a General Strategy for Complex Molecule Synthesis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2022, 55, 746–758. 10.1021/acs.accounts.1c00783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masarwa A.; Weber M.; Sarpong R. Selective C–C and C–H Bond Activation/Cleavage of Pinene Derivatives: Synthesis of Enantiopure Cyclohexenone Scaffolds and Mechanistic Insights. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 6327–6334. 10.1021/jacs.5b02254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Kuroda Y.; Nicacio K. J.; Alves da Silva I.; Leger P. R.; Chang S.; Gubiani J. R.; Deflon V. M.; Nagashima N.; Rode A.; Blackford K.; Ferreira A. G.; Sette L. D.; Williams D. E.; Andersen R. J.; Jancar S.; Berlinck R. G. S.; Sarpong R. Isolation, synthesis and bioactivity studies of phomactin terpenoids. Nat. Chem. 2018, 10, 938–945. 10.1038/s41557-018-0084-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Leger P. R.; Kuroda Y.; Chang S.; Jurczyk J.; Sarpong R. C–C Bond Cleavage Approach to Complex Terpenoids: Development of a Unified Total Synthesis of the Phomactins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 15536–15547. 10.1021/jacs.0c07316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Lusi R. F.; Sennari G.; Sarpong R. Total synthesis of nine longiborneol sesquiterpenoids using a functionalized camphor strategy. Nat. Chem. 2022, 14, 450–456. 10.1038/s41557-021-00870-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Lusi R. F.; Sennari G.; Sarpong R. Strategy Evolution in a Skeletal Remodeling and C–H Functionalization-Based Synthesis of the Longiborneol Sesquiterpenoids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 17277–17294. 10.1021/jacs.2c08136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerschgens I.; Rovira A. R.; Sarpong R. Total Synthesis of (−)-Xishacorene B from (R)-Carvone Using a C–C Activation Strategy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 9810–9813. 10.1021/jacs.8b05832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na C. G.; Kang S. H.; Sarpong R. Development of a C–C Bond Cleavage/Vinylation/Mizoroki–Heck Cascade Reaction: Application to the Total Synthesis of 14- and 15-Hydroxypatchoulol. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 19253–19257. 10.1021/jacs.2c09201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner N. J. Directed evolution drives the next generation of biocatalysts. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009, 5, 567–573. 10.1038/nchembio.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Li F.; King-Smith E.; Renata H. Merging chemoenzymatic and radical-based retrosynthetic logic for rapid and modular synthesis of oxidized meroterpenoids. Nat. Chem. 2020, 12, 173–179. 10.1038/s41557-019-0407-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Chen F.; Renata H. Concise Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of Gedunin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 19238–19242. 10.1021/jacs.2c09048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corey E. J.; Cheng X.-M.. The Logic of Chemical Synthesis, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: New York, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- a Marth C. J.; Gallego G. M.; Lee J. C.; Lebold T. P.; Kulyk S.; Kou K. G. M.; Qin J.; Lilien R.; Sarpong R. Network-analysis-guided synthesis of weisaconitine D and liljestrandinine. Nature 2015, 528, 493–498. 10.1038/nature16440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Klucznik T.; Mikulak-Klucznik B.; McCormack M. P.; Lima H.; Szymkuć S.; Bhowmick M.; Molga K.; Zhou Y.; Rickershauser L.; Gajewska E. P.; Toutchkine A.; Dittwald P.; Startek M. P.; Kirkovits G. J.; Roszak R.; Adamski A.; Sieredzińska B.; Mrksich M.; Trice S. L. J.; Grzybowski B. A. Efficient Syntheses of Diverse, Medicinally Relevant Targets Planned by Computer and Executed in the Laboratory. Chem. 2018, 4, 522–532. 10.1016/j.chempr.2018.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Doering N. A.; Sarpong R.; Hoffmann R. W. A Case for Bond-Network Analysis in the Synthesis of Bridged Polycyclic Complex Molecules: Hetidine and Hetisine Diterpenoid Alkaloids. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 10722–10731. 10.1002/anie.201909656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Shen Y.; Borowski J. E.; Hardy M. A.; Sarpong R.; Doyle A. G.; Cernak T. Automation and computer-assisted planning for chemical synthesis. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2021, 1, 23. 10.1038/s43586-021-00022-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Woo S.; Shenvi R. A. Natural Product Synthesis through the Lens of Informatics. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 1157–1167. 10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brill Z. G.; Grover H. K.; Maimone T. J. Enantioselective synthesis of an ophiobolin sesterterpene via a programmed radical cascade. Science 2016, 352, 1078–1082. 10.1126/science.aaf6742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thach D. Q.; Brill Z. G.; Grover H. K.; Esguerra K. V.; Thompson J. K.; Maimone T. J. Total Synthesis of (+)-6-epi-Ophiobolin A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 1532–1536. 10.1002/anie.201913150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga S.; Angyal P.; Martin G.; Egyed O.; Holczbauer T.; Soós T. Total Syntheses of (−)-Minovincine and (−)-Aspidofractinine through a Sequence of Cascade Reactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 13547–13551. 10.1002/anie.202004769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan P.; Gerlinger C. K. G.; Herberger J.; Gaich T. Ten-Step Asymmetric Total Synthesis of (+)-Pepluanol A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 11934–11938. 10.1021/jacs.1c05257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Jørgensen L.; McKerrall S. J.; Kuttruff C. A.; Ungeheuer F.; Felding J.; Baran P. S. 14-Step Synthesis of (+)-Ingenol from (+)-3-Carene. Science 2013, 341, 878–882. 10.1126/science.1241606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b McKerrall S. J.; Jørgensen L.; Kuttruff C. A.; Ungeheuer F.; Baran P. S. Development of a Concise Synthesis of (+)-Ingenol. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 5799–5810. 10.1021/ja501881p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Huang G.; Kouklovsky C.; de la Torre A. Gram-Scale Enantioselective Synthesis of (+)-Lucidumone. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 17803–17807. 10.1021/jacs.2c08760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Huang G.; Kouklovsky C.; de la Torre A. Retro-[4 + 2]/Intramolecular Diels–Alder Cascade Allows a Concise Total Synthesis of Lucidumone. Synlett 2023, 34, 1195–1199. 10.1055/s-0042-1751412. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang G.; Guillot R.; Kouklovsky C.; Maryasin B.; de la Torre A. Diastereo- and Enantioselective Inverse-Electron-Demand Diels-Alder Cycloaddition between 2-Pyrones and Acyclic Enol Ethers. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202208185 10.1002/anie.202208185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For a review, see:Huang G.; Kouklovsky C.; de la Torre A. Inverse-Electron-Demand Diels-Alder Reactions of 2-Pyrones: Bridged Lactones and Beyond. Chem.—Eur. J. 2021, 27, 4760–4788. 10.1002/chem.202003980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amberg W. M.; Carreira E. M. Enantioselective Total Synthesis of (+)-Aberrarone. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 15475–15479. 10.1021/jacs.2c07150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Lemière G.; Gandon V.; Cariou K.; Fukuyama T.; Dhimane A.-L.; Fensterbank L.; Malacria M. Tandem Gold(I)-Catalyzed Cyclization/Electrophilic Cyclopropanation of Vinyl Allenes. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 2207–2209. 10.1021/ol070788r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Lemière G.; Gandon V.; Cariou K.; Hours A.; Fukuyama T.; Dhimane A.-L.; Fensterbank L.; Malacria M. Generation and Trapping of Cyclopentenylidene Gold Species: Four Pathways to Polycyclic Compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 2993–3006. 10.1021/ja808872u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Su Y.; Jia Y. Total Synthesis of (+)-Aberrarone. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 9459–9463. 10.1021/jacs.3c02511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Gravel E.; Poupon E. Biosynthesis and biomimetic synthesis of alkaloids isolated from plants of the Nitraria and Myrioneuron genera: an unusual lysine-based metabolism. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2010, 27, 32–56. 10.1039/B911866G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Razzak M.; De Brabander J. K. Lessons and revelations from biomimetic syntheses. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011, 7, 865–875. 10.1038/nchembio.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Li X.-W.; Nay B. Transition metal-promoted biomimetic steps in total syntheses. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2014, 31, 533–549. 10.1039/C3NP70077A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Baunach M.; Franke J.; Hertweck C. Terpenoid Biosynthesis Off the Beaten Track: Unconventional Cyclases and Their Impact on Biomimetic Synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 2604–2626. 10.1002/anie.201407883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Bao R.; Zhang H.; Tang Y. Biomimetic Synthesis of Natural Products: A Journey To Learn, To Mimic, and To Be Better. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 3720–3733. 10.1021/acs.accounts.1c00459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak A. J. E.; Grigglestone C. E.; Trauner D. A Biomimetic Synthesis Elucidates the Origin of Preuisolactone A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 15515–15518. 10.1021/jacs.9b08892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira de Castro T.; Huang D. M.; Sumby C. J.; Lawrence A. L.; George J. H. A bioinspired, one-step total synthesis of peshawaraquinone. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 950–954. 10.1039/D2SC05377B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article.