Abstract

Background

Delirium occurs frequently in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the intensive care unit. Effective prevention and treatment strategies for delirium remain limited. We aimed to assess delirium and 30-day mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who were statin and non-statin users.

Methods

In this retrospective study, patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease were identified from the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care database (MIMIC-IV). The primary exposure variable was the use of statins 3 days after entering the intensive care unit and the primary outcome measure was the presence of delirium. The secondary outcome measure was 30-day mortality. Since the cohort study was retrospective, we used an inverse probability weighting derived from the propensity score matching to balance different variables.

Results

Among a cohort of 2725 patients, 1484 (54.5%) were statin users. Before propensity score matching, the prevalence of delirium was 16% and the 30-day mortality was 18% in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Statin use was significantly negatively correlated with delirium, with an odds ratio of 0.69 (95% CI 0.56–0.85, p < 0.001) in the inverse probability weighted cohort and 30-day mortality of 0.7 (95% CI 0.57–0.85, p < 0.001).

Conclusions

Statin use is associated with a lower incidence of delirium and 30-day mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the intensive care unit.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40001-023-01551-3.

Keywords: Delirium, Mortality, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Statin, Propensity analysis

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a common, preventable, and treatable disease, which is characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitations due to airway and/or alveolar abnormalities usually caused by significant exposure to dangerous particles or gases. Exacerbations negatively impact health status, hospitalization rates, and disease progression [1]. COPD is currently the third leading cause of deaths worldwide [2]. Many patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) present with comorbid COPD. Delirium is common in patients with COPD and in those with respiratory failure receiving mechanical ventilation [3]. Furthermore, the probability of survival in patients with COPD undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) who developed postoperative delirium is significantly lower [4]. Delirium manifests itself as acute state of attention, cognitive impairment and mental disorder that can be related to potential physiological disorders [5]. Delirium is often accompanied by increased morbidity, prolonged hospitalization, higher medical costs and mortality [6]. However, the treatment of delirium is limited, so prevention is critical.

Recently, contradictory evidence has been provided on the role of statins in preventing delirium. Some studies have found that statins can reduce the occurrence of delirium, including in the ICU and in cases of postoperative delirium [7, 8]. Other studies have contrary findings that the effect of statins on delirium is related to the severity of the disease and not to its occurrence [9, 10]. A meta-analysis that included both cohort studies and randomized clinical trials (RCT) showed that treatment with statins was associated with a significant reduction in all-cause mortality in patients with COPD [11]. Although a meta-analysis that included only RCTs did not show benefits for patients with COPD [12, 13]. The role of statins on mortality in patients with COPD is controversial.

Systemic and respiratory inflammation is believed to be the major cause of lung damage in COPD [14] and studies have shown that statins reduce serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in patients with COPD [11] which were strong predictors of delirium [15]. As statins have a potent anti-inflammatory effect, the hypothesis that pharmacological intervention with statins can decrease the risk of delirium in patients with COPD needs to be confirmed. To date, no studies have examined the effects of statin use on delirium in patients with COPD. We used the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV (MIMIC-IV) database (version 2.2) to investigate the relationship between statins and delirium and 30-day mortality in patients with COPD admitted to the ICU. In this study, we use weighted analysis according to the propensity score. Propensity score matching (PSM) was used to appropriately adjust for confounding factors, reduce the impact of these deviations and confounding variables, to allow a more reasonable comparison between the statin-exposed group and non-statin-exposed group.

Methods

Data sources

This retrospective cohort study was based on the MIMIC-IV database (version 2.2) [16], which contains data from patients admitted to the ICU of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Centre in Boston, Massachusetts, between 2008 and 2019. One author (JLX) obtained access to the database and was responsible for data extraction. The establishment of the MIMIC-IV database was approved by the institutional review boards of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Centre and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Affiliates. The informed consent requirement was waived because the data from all patients in the database were anonymized.

Study population and data extraction

We included all patients who were first admitted to the ICU diagnosed with COPD [17] in the MIMIC-IV database. We excluded (i) patients with dementia; (ii) patients younger than 18 years; (iii) patients without a CAM-ICU estimate; (iiii) patients with a duration of stay in the ICU stay < 2 days; (v) patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Navicat Premium (version 16.0) was used to extract raw data relative to patients diagnosed with COPD from the MIMIC-IV database (version 2.2). The data extracted included demographics, laboratory tests results, vital signs, comorbidities, and administered drugs. The following demographic information was extracted: age, sex, length of hospitalization, and duration of stay in the ICU. Vital signs such as systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), heart rate (HR), respiratory rate (RR), and oxygenated hemoglobin saturation (SpO2) were collected. Comorbidities including diabetes, asthma, coronary artery disease (CAD), peripheral vascular disease (PVD), congestive heart failure (CHF), malignant cancer, cerebrovascular disease (CVD), liver disease, and renal disease were extracted. Laboratory data included white blood cell (WBC) count, hemoglobin (HGB) level, platelets (PLT), blood glucose, anion gap, potassium, sodium, and calcium levels. We also extracted whether the patient received mechanical ventilation. The use of vasoactive drugs (norepinephrine, vasopressin, epinephrine) and antibiotics was also included. Whether the patient received oral or intravenous glucocorticoids was also determined. Whether the patient received ACEI/ARB, β-blockers, and statins 3 days after entering the ICU were extracted. A Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS II), Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), and the Oxford Acute Severity of Illness Score (OASIS), which represents the severity of the disease, were also included.

Statin use

We defined patients with records of 3 days of statin use before or after admission to the ICU as statin-exposed and others as non-statin-exposed. We searched drug ILIKE “statin” and NOT ILIKE “nystatin”, “mycostatin”, “imipenem-cilastatin”, “pentostatin”, and “sandostatin” in Navicat Premium (version 16.0). The medication prescriptions were recorded in the MIMIC-IV table (version 2.2) under “mimic-hospital, prescription”.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the occurrence of delirium during the stay in the ICU. The secondary outcome was the 30-day mortality rate. The Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU) method was used to assess delirium in patients [18].

Statistical analysis

The characteristics of the patients are described in general and by group (statin-exposed and non-statin-exposed). The measured data are expressed as mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile interval) according to whether they were normally distributed. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Kruskal–Wallis H test was performed depending on whether the data were normally distributed. Categorical variables were expressed as percentages and treated with Chi-square tests.

Propensity score matching (PSM) was used to adjust for confounders between the non-statin and statin groups. The following prognostic variables related to the outcome at p < 0.2 in the univariate analysis (Additional file 1: Table S1) were included in the propensity score: age, HGB, WBC, sodium and calcium, CAD, asthma, liver disease, malignant cancer, SBP, DBP, HR, and SpO2 on the first day of admission, ACEI/ARB, antibiotic and glucocorticoids after admission to the ICU, and norepinephrine, vasopressin, epinephrine, SAPII, OASIS score and length of ICU stay for delirium were forced in the PSM. The variables that were included in the 30-day mortality analysis are shown in Additional file 1: Table S2. Using the estimated propensity scores as weights, an inverse probability weighting (IPW) model was used to generate a weighted cohort [19]. The probability of being exposed to statin was estimated using a logistic regression for each patient. We matched the two groups in a 1:1 ratio with a caliper width of 0.2. The standardized mean difference (SMD) was used to examine the degree of PSM. The R software packages (http://www.R-project.org, The R Foundation) and Free Statistics software versions 1.7 were used to perform all statistical analyses. Statistical differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

Sensitivity analysis

Patients were re-grouped according to whether they were on statins or not before ICU admission. There were three groups, no statin users, statin use after ICU admission and statin use both before and after ICU admission. There were no patients who were statin users before ICU and not statin users after ICU admission. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to ascertain the relationship between statin use and the incidence of delirium in patients with COPD adjusting covariates as for PSM. We did a subgroup analysis in logistic regression to investigate the association between statin use and delirium and 30-day mortality, as it differed between various subgroups classified by age, sex, CAD, CHF, antibiotic and glucocorticoids use, CCI, SAPII, OASIS score and length of ICU stay.

Results

Baseline characteristics

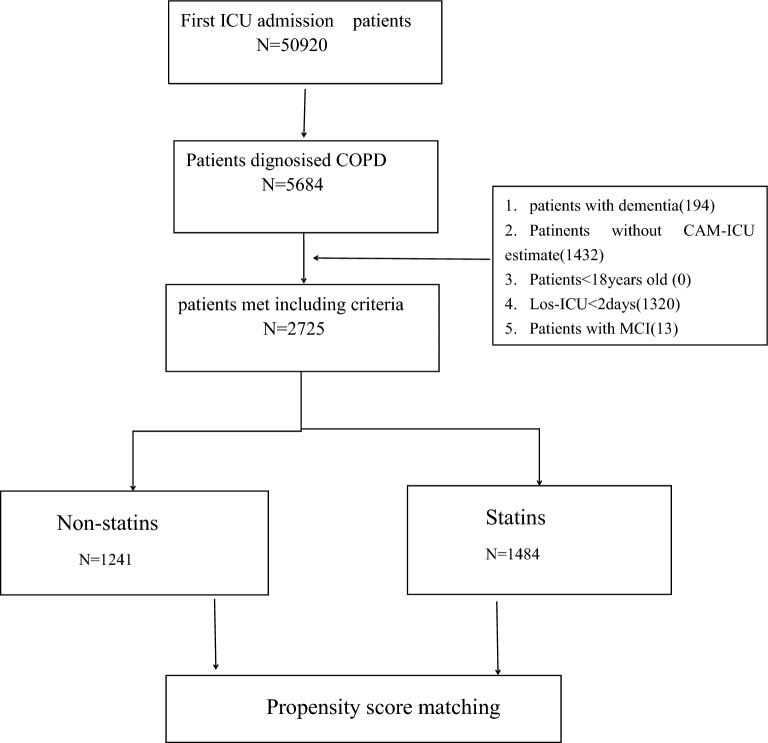

Among the 50,920 patients who were admitted to the ICU and included in the MIMIC-IV database, 2725 patients had COPD and were evaluated using CAM-ICU methods. The patient selection process is shown in Fig. 1. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the statin and non-statin groups. In total, 1484 (54.5%) patients were exposed to statins. The median age of the patients was 72 years (range, 64 to 80), and 53.4% were male. The total incidence of delirium was 16% (436/2725) and that of 30-day mortality was 18% (492/2725). Patients in the statin group had a higher age, a higher rate of diabetes, CAD, CHF, PVD, renal disease, and CVD. Moreover, they also received treatment with more ACEI/ARB and vasoactive drugs than those in the non-statin group (all p < 0.05). However, they had a lower use of antibiotics and glucocorticoids and the incidence of delirium (13.4–19.1%) and 30-day mortality was lower (15–21.7%) (for all p < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of cohort selection

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Variables | Total (n = 2725) | Non-statins | Statins | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 1241) | (n = 1484) | |||

| Number | ||||

| Age(year) | 72 (64, 80) | 69 (61, 78) | 73 (67, 80) | < 0.001 |

| Gender(male) | 1456 (53.4) | 643 (51.8) | 813 (54.8) | 0.121 |

| Los-ICU | 5.5 ± 5.9 | 6.0 ± 6.4 | 5.1 ± 5.4 | < 0.001 |

| Hospital days | 12.4 ± 10.2 | 12.9 ± 10.9 | 12.0 ± 9.7 | 0.013 |

| Vitals | ||||

| SBP (mmHg) | 117.0 ± 16.0 | 116.6 ± 15.6 | 117.4 ± 16.3 | 0.197 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 61.9 ± 10.8 | 63.1 ± 11.0 | 60.9 ± 10.6 | < 0.001 |

| HR (beats/min) | 85.9 ± 15.6 | 87.7 ± 16.4 | 84.4 ± 14.7 | < 0.001 |

| RR (beats/min) | 19.8 ± 3.7 | 19.9 ± 3.9 | 19.8 ± 3.5 | 0.29 |

| SpO2 (%) | 96.2 ± 2.3 | 96.2 ± 2.3 | 96.2 ± 2.2 | 0.826 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Asthma | 114 ( 4.2) | 55 (4.4) | 59 (4) | 0.544 |

| CAD | 456 (16.7) | 117 (9.4) | 339 (22.8) | < 0.001 |

| CHF | 1216 (44.6) | 422 (34) | 794 (53.5) | < 0.001 |

| PVD | 517 (19.0) | 168 (13.5) | 349 (23.5) | < 0.001 |

| CVD | 433 (15.9) | 161 (13) | 272 (18.3) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes | 938 (34.4) | 315 (25.4) | 623 (42) | < 0.001 |

| Liver disease | 314 (11.5) | 219 (17.6) | 95 (6.4) | < 0.001 |

| Renal disease | 692 (25.4) | 215 (17.3) | 477 (32.1) | < 0.001 |

| Malignant cancer | 446 (16.4) | 255 (20.5) | 191 (12.9) | < 0.001 |

| Laboratory events | ||||

| WBC(109/L) | 14.7 ± 11.2 | 15.0 ± 14.1 | 14.5 ± 8.0 | 0.249 |

| HGB (g/L) | 11.3 ± 2.2 | 11.5 ± 2.3 | 11.3 ± 2.1 | 0.014 |

| PLT (109/L) | 147.0 (119.0, 196.0) | 144.0 (118.0, 190.0) | 149.0 (120.0, 199.2) | 0.038 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 209.0 (156.0, 277.0) | 206.0 (148.0, 284.0) | 210.5 (160.8, 272.0) | 0.184 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 8.6 ± 0.7 | 8.6 ± 0.8 | 8.6 ± 0.7 | 0.047 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 139.6 ± 4.9 | 139.5 ± 5.3 | 139.7 ± 4.6 | 0.342 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 4.7 ± 0.9 | 4.7 ± 0.9 | 4.7 ± 0.8 | 0.553 |

| Anion gap (mmol/L) | 16.4 ± 4.5 | 16.5 ± 4.7 | 16.3 ± 4.4 | 0.161 |

| Treatment, n (%) | ||||

| Glucocorticoid | 968 (35.5) | 483 (38.9) | 485 (32.7) | < 0.001 |

| Antibiotic | 2280 (83.7) | 1073 (86.5) | 1207 (81.3) | < 0.001 |

| Vasopressin | 284 (10.4) | 114 (9.2) | 170 (11.5) | 0.054 |

| Norepinephrine | 575 (21.1) | 238 (19.2) | 337 (22.7) | 0.024 |

| Epinephrine | 130 ( 4.8) | 56 (4.5) | 74 (5) | 0.563 |

| ACEI/ARB | 416 (15.3) | 122 (9.8) | 294 (19.8) | < 0.001 |

| β-blocker | 1437 (52.7) | 545 (43.9) | 892 (60.1) | < 0.001 |

| VENT | 873 (32.0) | 387 (31.2) | 486 (32.7) | 0.383 |

| Scores | ||||

| CCI | 7.4 ± 2.6 | 7.0 ± 2.6 | 7.8 ± 2.5 | < 0.001 |

| SAPII | 39.8 ± 12.8 | 40.4 ± 14.0 | 39.3 ± 11.6 | 0.023 |

| OASIS | 34.3 ± 9.0 | 35.5 ± 9.4 | 33.3 ± 8.5 | < 0.001 |

| Outcomes, n (%) | ||||

| Delirium | 436 (16.0) | 237 (19.1) | 199 (13.4) | < 0.001 |

| 30-day mortality | 492 (18.1) | 269 (21.7) | 223 (15) | < 0.001 |

Data are presented as mean (SD), medians [interquartile ranges] or numbers (percentages)

SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, HR heart rate, RR respiratory rate, CAD coronary artery disease, CHF congestive heart failure, PVD peripheral vascular disease, CVD cerebrovascular disease, HGB hemoglobin, WB white blood cell count, PLT platelets, ACEI/ARB angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin II inhibitors, VENT mechanical ventilation, CCI Charlson comorbidity index, SAPS II Simplified Acute Physiology Score, OASIS Oxford Acute Severity of Illness Score, Los length of stay

Propensity score matching analysis

We used PSM to balance the baseline characteristics. After matching, 959 and 888 patients with delirium and 30-day mortality, respectively, were included in each group. The SMD of all covariates after matching was less than 0.1, indicating that the balance was sufficient after matching (Tables 2, 3). We also reported variables in the subject operating characteristic (ROC) curve for delirium (Fig. 2A) and 30-day mortality (Fig. 2B). The area under the curve (AUC) was calculated to assess the relationship between statin use and delirium (70.4%) and 30-day mortality (73%).

Table 2.

Imbalance of patient characteristics before and after propensity score matching in the assessment of delirium

| Item n |

Unmatched | SMD | Matched | SMD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-statins | Statins | SMD | − 0.1 | Non-statins | Statins | SMD | − 0.1 | |

| 1241 | 1484 | 955 | 955 | |||||

| Age (year) | 69.46 (11.77) | 73.12 (9.80) | 0.338 | > 0.1 | 71.56 (11.38) | 71.54 (9.58) | 0.002 | < 0.1 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 116.61 (15.63) | 117.41 (16.35) | 0.05 | < 0.1 | 117.03 (15.40) | 117.40 (16.22) | 0.023 | < 0.1 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 63.14 (10.99) | 60.91 (10.59) | 0.207 | > 0.1 | 62.22 (10.69) | 62.15 (10.78) | 0.006 | < 0.1 |

| HR (beats/min) | 87.74 (16.36) | 84.37 (14.75) | 0.216 | > 0.1 | 86.22 (15.95) | 85.90 (15.38) | 0.021 | < 0.1 |

| SpO2 (%) | 96.16 (2.34) | 96.18 (2.20) | 0.008 | < 0.1 | 96.15 (2.35) | 96.18 (2.15) | 0.009 | < 0.1 |

| Asthma | 55 (4.4) | 59 (4.0) | 0.023 | < 0.1 | 45 ( 4.7) | 47 (4.9) | 0.01 | < 0.1 |

| CAD | 117 (9.4) | 339 (22.8) | 0.371 | > 0.1 | 111 (11.6) | 119 (12.5) | 0.026 | < 0.1 |

| Liver disease | 219 (17.6) | 95 ( 6.4) | 0.351 | > 0.1 | 85 (8.9) | 87 (9.1) | 0.007 | < 0.1 |

| Malignant cancer | 255 (20.5) | 191 (12.9) | 0.207 | > 0.1 | 165 (17.3) | 155 (16.2) | 0.028 | < 0.1 |

| PLT (109/L) | 225.28 (114.45) | 227.34 (99.49) | 0.019 | < 0.1 | 229.06 (108.70) | 230.91 (105.12) | 0.017 | < 0.1 |

| HGB (g/L) | 11.46 (2.26) | 11.26 (2.10) | 0.094 | < 0.1 | 11.38 (2.22) | 11.42 (2.13) | 0.018 | < 0.1 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 8.58 (0.81) | 8.64 (0.69) | 0.076 | < 0.1 | 8.62 (0.80) | 8.61 (0.69) | 0.012 | < 0.1 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 139.55 (5.27) | 139.73 (4.64) | 0.036 | < 0.1 | 139.70 (4.87) | 139.72 (4.60) | 0.005 | < 0.1 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 169.56 (96.72) | 177.37 (104.89) | 0.077 | < 0.1 | 170.52 (100.27) | 172.39 (92.73) | 0.019 | < 0.1 |

| Glucocorticoid | 483 (38.9) | 485 (32.7) | 0.13 | > 0.1 | 355 (37.2) | 355 (37.2) | < 0.001 | < 0.1 |

| Antibiotic | 1073 (86.5) | 1207 (81.3) | 0.14 | > 0.1 | 802 (84.0) | 804 (84.2) | 0.006 | < 0.1 |

| Norepinephrine | 238 (19.2) | 337 (22.7) | 0.087 | < 0.1 | 202 (21.2) | 188 (19.7) | 0.036 | < 0.1 |

| Epinephrine | 56 (4.5) | 74 (5.0) | 0.022 | < 0.1 | 47 (4.9) | 40 (4.2) | 0.035 | < 0.1 |

| Vasopressin | 114 (9.2) | 170 (11.5) | 0.075 | < 0.1 | 102 (10.7) | 88 (9.2) | 0.049 | < 0.1 |

| ACEI/ARB | 122 (9.8) | 294 (19.8) | 0.284 | > 0.1 | 117 (12.3) | 124 (13.0) | 0.022 | < 0.1 |

| SAPII | 40.39 (14.03) | 39.28 (11.58) | 0.087 | < 0.1 | 39.81 (13.40) | 39.74 (12.17) | 0.006 | < 0.1 |

| OASIS | 35.51 (9.39) | 33.29 (8.46) | 0.249 | > 0.1 | 34.47 (9.08) | 34.47 (8.60) | < 0.001 | < 0.1 |

| Los-ICU | 6.01 (6.45) | 5.10 (5.45) | 0.152 | > 0.1 | 5.51 (5.99) | 5.55 (6.16) | 0.006 | < 0.1 |

An absolute MSD < 10% was considered to support the assumption of a balance between the groups. SMD: standardized mean differences. Data are presented as medians [interquartile ranges], mean [SD] or as numbers (percentages)

SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, HR heart rate, CAD coronary artery disease, CVD cerebrovascular disease, RR respiratory rate, HGB hemoglobin, WB white blood cell count, ACEI/ARB angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin II inhibitors, SAPS II Simplified Acute Physiology Score, OASIS Oxford Acute Severity of Illness Score, Los length of stay

Table 3.

Imbalance of patient characteristics before and after propensity score matching in the assessment of 30-day mortality

| Item n |

Unmatched | SMD | Matched | SMD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-statins | Statins | SMD | − 0.1 | Non-statins | Statins | SMD | − 0.1 | |

| 1241 | 1484 | 882 | 882 | |||||

| Age (year) | 69.46 (11.77) | 73.12 (9.80) | 0.338 | > 0.1 | 71.83 (11.33) | 71.76 (9.87) | 0.006 | < 0.1 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 116.61 (15.63) | 117.41 (16.35) | 0.05 | < 0.1 | 117.40 (15.67) | 117.50 (16.32) | 0.006 | < 0.1 |

| DBP(mmHg) | 63.14 (10.99) | 60.91 (10.59) | 0.207 | > 0.1 | 62.43 (10.97) | 62.24 (10.85) | 0.017 | < 0.1 |

| HR (beats/min) | 87.74 (16.36) | 84.37 (14.75) | 0.216 | > 0.1 | 86.25 (16.04) | 85.81 (15.29) | 0.028 | < 0.1 |

| RR (beats/min) | 19.91 (3.87) | 19.76 (3.48) | 0.041 | < 0.1 | 19.75 (3.67) | 19.90 (3.54) | 0.042 | < 0.1 |

| SpO2 (%) | 96.16 (2.34) | 96.18 (2.20) | 0.008 | < 0.1 | 96.18 (2.20) | 96.15 (2.18) | 0.013 | < 0.1 |

| CHF | 422 (34.0) | 794 (53.5) | 0.401 | > 0.1 | 374 (42.4) | 377 (42.7) | 0.007 | < 0.1 |

| Asthma | 55 ( 4.4) | 59 ( 4.0) | 0.023 | < 0.1 | 36 ( 4.1) | 46 (5.2) | 0.054 | < 0.1 |

| Diabetes | 315 (25.4) | 623 (42.0) | 0.357 | > 0.1 | 273 (31.0) | 281 (31.9) | 0.02 | < 0.1 |

| Liver disease | 219 (17.6) | 95 ( 6.4) | 0.351 | > 0.1 | 74 ( 8.4) | 86 (9.8) | 0.047 | < 0.1 |

| Renal disease | 215 (17.3) | 477 (32.1) | 0.349 | > 0.1 | 193 (21.9) | 190 (21.5) | 0.008 | < 0.1 |

| Malignant cancer | 255 (20.5) | 191 (12.9) | 0.207 | > 0.1 | 158 (17.9) | 143 (16.2) | 0.045 | < 0.1 |

| HGB(g/L) | 11.46 (2.26) | 11.26 (2.10) | 0.094 | < 0.1 | 11.37 (2.21) | 11.47 (2.14) | 0.046 | < 0.1 |

| WBC(10^9/L) | 15.01 (14.11) | 14.51 (7.95) | 0.043 | < 0.1 | 14.74 (10.07) | 15.03 (8.22) | 0.032 | < 0.1 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 169.56 (96.72) | 177.37 (104.89) | 0.077 | < 0.1 | 170.17 (100.76) | 172.59 (99.14) | 0.024 | < 0.1 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 139.55 (5.27) | 139.73 (4.64) | 0.036 | < 0.1 | 139.64 (5.04) | 139.64 (4.51) | < 0.001 | < 0.1 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 4.68 (0.90) | 4.70 (0.83) | 0.023 | < 0.1 | 4.67 (0.89) | 4.69 (0.80) | 0.017 | < 0.1 |

| Anion gap (mmol/L) | 16.50 (4.65) | 16.26 (4.35) | 0.054 | < 0.1 | 16.16 (4.29) | 16.22 (4.35) | 0.014 | < 0.1 |

| Glucocorticoid | 483 (38.9) | 485 (32.7) | 0.13 | > 0.1 | 330 (37.4) | 321 (36.4) | 0.021 | < 0.1 |

| Antibiotic | 1073 (86.5) | 1207 (81.3) | 0.14 | > 0.1 | 741 (84.0) | 742 (84.1) | 0.003 | < 0.1 |

| Vasopressin | 114 (9.2) | 170 (11.5) | 0.075 | < 0.1 | 89 (10.1) | 82 (9.3) | 0.027 | < 0.1 |

| Epinephrine | 56 (4.5) | 74 (5.0) | 0.022 | < 0.1 | 44 (5.0) | 43 (4.9) | 0.005 | < 0.1 |

| Norepinephrine | 238 (19.2) | 337 (22.7) | 0.087 | < 0.1 | 181 (20.5) | 171 (19.4) | 0.028 | < 0.1 |

| ACEI.ARB | 122 (9.8) | 294 (19.8) | 0.284 | > 0.1 | 109 (12.4) | 119 (13.5) | 0.034 | < 0.1 |

| β-blocker | 545 (43.9) | 892 (60.1) | 0.328 | > 0.1 | 462 (52.4) | 464 (52.6) | 0.005 | < 0.1 |

| CCI | 6.98 (2.62) | 7.82 (2.47) | 0.33 | > 0.1 | 7.28 (2.65) | 7.28 (2.47) | < 0.001 | < 0.1 |

| SAPII | 40.39 (14.03) | 39.28 (11.58) | 0.087 | < 0.1 | 39.57 (12.52) | 39.78 (12.46) | 0.017 | < 0.1 |

| OASIS | 35.51 (9.39) | 33.29 (8.46) | 0.249 | > 0.1 | 34.46 (8.84) | 34.48 (8.79) | 0.002 | < 0.1 |

| Los-ICU | 6.01 (6.45) | 5.10 (5.45) | 0.152 | > 0.1 | 5.48 (5.85) | 5.42 (5.69) | 0.01 | < 0.1 |

An absolute MSD < 10% was considered to support the assumption of a balance between the groups. SMD: standardized mean differences. Data are presented as medians [interquartile ranges], mean [SD] or as numbers (percentages)

SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, HR heart rate, RR respiratory rate, HGB hemoglobin, WB white blood cell count, ACEI/ARB angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin II inhibitors, CCI Charlson comorbidity index, SAPS II Simplified Acute Physiology Score, OASIS Oxford Acute Severity of Illness Score, Los length of stay

Fig. 2.

A Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for delirium. B Receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) for 30-day mortality

Association between statin exposure and outcomes

Before matching, regression analysis showed that statin exposure was significantly associated with a reduced odds ratio 0.66 (95% CI 0.53–0.81, p < 0.001) (Table 4) for delirium. After IPW, the risk of reduced delirium remained significantly associated with statin exposure with an odds ratio 0.69 (95% CI 0.56–0.85, p < 0.001). Before matching, the reduced risk of 30-day mortality was significantly related to statin exposure at an odds ratio of 0.64 (95% CI 0.53–0.78, p < 0.001). After IPW, the reduced risk of 30-day mortality remained significantly associated with statin exposure with an odds ratio of 0.7 (95% CI 0.57–0.85, p < 0.001). The results were similar to those obtained with the PSM model.

Table 4.

Associations between statin use and the outcome in the crude analysis, multivariable analysis, and propensity-score analyses

| Analysis | Delirium (%) | p | 30-day mortality (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of events/no. of patients at risk (%) | ||||

| No statin use | 237/1241 (19.1) | 269 (21.7) | ||

| Statin use | 199/1484 (13.4) | 223 (15) | ||

| Crude analysis-hazard ratio (95% CI) | 0.66 (0.53–0.81) | < 0.001 | 0.64 (0.53–0.78) | < 0.001 |

| Multivariable analysis-hazard ratio (95% CI) | 0.67 (0.52–0.85) | 0.001 | 0.67 (0.52–0.85) | 0.001 |

| With matching | 0.7 (0.54–0.9) | 0.006 | 0.76 (0.6–0.97) | 0.028 |

| With inverse probability weighting | 0.69 (0.56–0.85) | < 0.001 | 0.7 (0.57–0.85) | < 0.001 |

| Adjusted for propensity score | 0.7 (0.56–0.88) | 0.002 | 0.73 (0.59–0.9) | 0.003 |

CI confidence interval

Of all statin users, some used statins after ICU admission and some used statins both before and after ICU admission. We further subgrouped the patients using statins. Among the 1484 patients using statins, 644 patients started statins after ICU admission and 840 patients used statins both before and after ICU admission (Additional file 1: Table S5). Multifactorial regression showed that statin use after ICU admission can significantly reduced delirium regardless of statin use before ICU admission or not(p < 0.001 or p = 0.047). Statin use after ICU admission reduced 30-day mortality from 21.7% to 16.6% compared to non-statin use group, but it was not statistically significant (p = 0.287), which may require a large sample of studies for validation. Using statin before ICU admission can significantly reduce 30-day mortality (p < 0.001) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Odds ratio for delirium and 30-day mortality according to statin use

| Group | Delirium | 30-day mortality | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of events/No. (%) | Crude.OR_95CI | p | adj.OR_95CI | p | No. of events/No. (%) | crude.OR_95CI | p | adj.OR_95CI | p | |

| No statin use | 237/1241 (19.1) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 269/1241 (21.7) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | ||||

| Statin use after ICU | 68/644 (10.6) | 0.5 (0.37–0.67) | < 0.001 | 0.55 (0.4–0.75) | < 0.001 | 107/644 (16.6) | 0.72 (0.56–0.92) | 0.009 | 0.85 (0.63–1.15) | 0.287 |

| Statin use before and after ICU | 131/840 (15.5) | 0.78 (0.62–0.99) | 0.04 | 0.76 (0.58–1) | 0.047 | 116/840 (13.8) | 0.58 (0.46–0.73) | < 0.001 | 0.55 (0.41–0.73) | < 0.001 |

Adjusted model in delirium was adjusted for age, SBP, DBP, HR, SpO2, CAD, asthma, liver disease, ACEI/ARB, antibiotic, glucocorticoids, HGB, PLT, sodium and calcium, norepinephrine, vasopressin, epinephrine, SAPII, OASIS, Los-ICU. Adjusted model in 30-day mortality was adjusted for age, SBP, DBP, HR, RR, SpO2, CHF, asthma, Diabetes, liver disease, ACEI/ARB, β-blockers, antibiotic, glucocorticoids, WBC, HGB, potassium and sodium, norepinephrine, vasopressin, epinephrine, CCI, SAPII, OASIS, Los-ICU

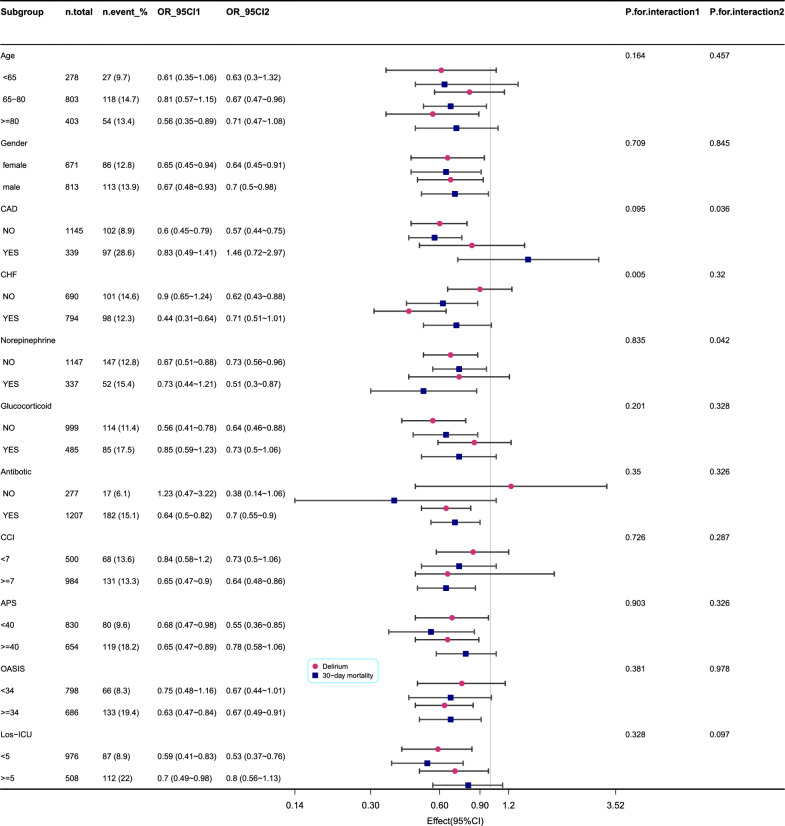

Subgroup analyses

As shown in Fig. 3 (the original form is in Additional file 1: Tables S3 and S4), we found that patients with CHF showed an interaction between statin exposure and delirium (p = 0.005). Patients with CAD and expose to norepinephrine showed an interaction between statin exposure and 30-day mortality (p = 0.036 and p = 0.042). The p-value for the interaction in the other subgroups showed no interaction with delirium or mortality at 30 days.

Fig. 3.

Subgroup analysis evaluating the relationship between statin exposure and delirium and 30-day mortality in patients with COPD

Discussion

In this observational study of patients with COPD, we used PSM and found that statin administration after admission to the ICU was significantly associated with a reduced risk of delirium regardless of whether statin was used or not before ICU admission. Statin used both before and after ICU was significantly associated with a reduced risk of 30-day mortality. To our knowledge, this is the first observational study on the association between statin exposure and delirium and 30-day mortality in patients with COPD. We subgrouped the timing of statin use with respect to whether the statin was used before or after ICU admission. The results demonstrated that the earlier the statin was used the more beneficial it was for 30-day mortality in patients with COPD.

Previous studies have found that statins reduce delirium in critically ill patients in the ICU [7, 20], but there have been no studies on statins in ICU patients with COPD. Although COPD has been found to increase the incidence of postoperative delirium in patients undergoing CABG [4], delirium is more common in patients with COPD combined with respiratory failure undergoing mechanical ventilation [3]. In our study, the use of statins in the ICU significantly reduced the incidence of delirium, and a subgroup analysis found that statins had a more significant effect in patients with CHF which is consistent with the study we done before [21]. Patients with CHF have higher rates of statin using (53.5% to 34%), especially they are used before ICU admission (58.7%). The role of statins in the management of people with cardiovascular disease is well understood.

In our study, 54.5% of patients with COPD received statins, and more than half of the patients were taking statins. Several studies have found that statins reduce hospitalization rates and acute exacerbations in patients with COPD [22–24] but do not influence 30-day or 1-year mortality [22] nor are they associated with the occurrence of COPD in the adult population [24]. However, it is interesting that observational studies have found that statins reduce COPD mortality [11], while a RCT did not find this effect of statins [12]. According to a previous retrospective analysis [25] of 574 individuals from the Copenhagen General Population Study, statin use was associated with a reduced probability of exacerbations only in individuals with COPD of the general population, but not in those with the most severe COPD without cardiovascular comorbidity. However, it is unknown whether the effects of statin on mortality are related to cardiovascular disease. Our subgroup analysis found that statins did not reduce mortality in patients with COPD with CAD.

COPD is considered a chronic systemic inflammatory syndrome that can often be accompanied by impaired blood oxygenation, and both inflammation and impaired blood oxygenation can lead to an increased incidence of delirium in patients with COPD. Decreased lung function is associated with increased oxidative stress and inflammation, and studies have shown that statins reduce the levels of inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) in COPD patients [26] and slow the decline in lung function [27]. Statins have been prescribed for the primary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease because they effectively lower low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels, and a recent study found that the use of atorvastatin relieved cerebral vasospasm and mediated structural and functional remodeling of vascular endothelial cells [28], which may be related to the fact that statins can prevent delirium and mortality.

This study has some limitations. First, baseline data before admission to the MIMIC-IV database may be incomplete, which could have affected specific data relative to delirium regarding preoperative cognitive status, psychiatric history, and educational level. We excluded dementia and MIC, because these patients are prone to delirium [29, 30]. Second, we did not classify the type of statin used, although lipophilic statins are found to be more effective against acute exacerbations of COPD in patients with cardiovascular disease [24]. Third, our study was a retrospective study. Although we used PSM to control for confounding, residual confounders cannot be completely excluded. Finally, we could not assess the actual medicinal dosage or if patients admitted with an acute illness and the rounding physician decides to increase dosage after ICU admission. Large sample studies are warranted.

Conclusions

Statin use is associated with a lower incidence of delirium and 30-day mortality in patients with COPD in the ICU. Continued statin use after hospital admission may be important in reducing mortality.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Univariate regression analysis for delirium. Table S2. Univariate regression analysis for 30-day mortality. Table S3. Subgroup analysis of the relationship between statin exposure and delirium in patients with COPD. Table S4. Subgroup analysis of the relationship between statin exposure and 30-day mortality in patients with COPD. Table S5. Baseline characteristics according statin use before or after ICU.

Acknowledgements

None.

Abbreviations

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- MIMIC-IV

Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care-IV

- PSM

Propensity score matching

- CI

Confidence interval

- IPW

Inverse probability weighting

- MCI

Mild cognitive impairment

Author contributions

JX designed the study and wrote the manuscript, CH analyzed the data. LW reviewed the statistical analyses. YZ conducted data collection and data interpretation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None.

Data availability

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. These data can be found at https://physionet.org/content/mimiciv/2.2.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The MIMIC-IV database has received ethical approval from the institutional review boards (IRBs) at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Because the database does not contain protected health information, a waiver of the requirement for informed consent was included in the IRB approval. The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Patel AR, et al. Global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease: the changes made. Cureus. 2019;11(6):e4985. doi: 10.7759/cureus.4985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Easter M, et al. Targeting aging pathways in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(18):6924. doi: 10.3390/ijms21186924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fu X, et al. Delirium in elderly patients with COPD combined with respiratory failure undergoing mechanical ventilation: a prospective cohort study. BMC Pulm Med. 2022;22(1):266. doi: 10.1186/s12890-022-02052-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Szylińska A, et al. Postoperative delirium in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease after coronary artery bypass grafting. Medicina. 2020;56(7):342. doi: 10.3390/medicina56070342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oh ES, et al. Delirium in older persons: advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2017;318(12):1161–1174. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.12067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Witlox J, et al. Delirium in elderly patients and the risk of postdischarge mortality, institutionalization, and dementia: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;304(4):443–451. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mather JF, et al. Statin and its association with delirium in the medical ICU. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(9):1515–1522. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee DS, et al. Preoperative statins are associated with a reduced risk of postoperative delirium following vascular surgery. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(3):e0192841. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.An JY, et al. The relationship between delirium and statin use according to disease severity in patients in the intensive care unit. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2023;21(1):179–187. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2023.21.1.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang YH, et al. Statin use and delirium risk: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Ther. 2023 doi: 10.1097/MJT.0000000000001593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu Y, et al. Effectiveness of long-term using statins in COPD—a network meta-analysis. Respir Res. 2019;20(1):17. doi: 10.1186/s12931-019-0984-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walsh A, et al. Statins versus placebo for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;7(7):CD011959. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011959.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang W, et al. Effect of statins on COPD: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Chest. 2017;152(6):1159–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agusti A, Hogg JC. Update on the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(13):1248–1256. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1900475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ali MA, et al. Incidence and risk factors of delirium in surgical intensive care unit. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2021;6(1):e000564. doi: 10.1136/tsaco-2020-000564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson A, et al. MIMIC-IV (version 2.2). PhysioNet. Sci Data. 2023;10(1):1. doi: 10.13026/6mm1-ek67. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fan L, et al. Association between serum sodium and long-term mortality in critically ill patients with comorbid chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: analysis from the MIMIC-IV database. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2022;17:1143–1155. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S353741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ely EW, et al. Evaluation of delirium in critically ill patients: validation of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU) Crit Care Med. 2001;29(7):1370–1379. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feng M, et al. Transthoracic echocardiography and mortality in sepsis: analysis of the MIMIC-III database. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44(6):884–892. doi: 10.1007/s00134-018-5208-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morandi A, et al. Statins and delirium during critical illness: a multicenter, prospective cohort study. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(8):1899–1909. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xia J, et al. Association between delirium and statin use in patients with congestive heart failure: a retrospective propensity score-weighted analysis. Front Aging Neurosci. 2023;15:1184298. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2023.1184298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bartziokas K, et al. Statins and outcome after hospitalization for COPD exacerbation: a prospective study. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2011;24(5):625–631. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin CM, et al. Statin use and the risk of subsequent hospitalized exacerbations in COPD patients with frequent exacerbations. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2020;15:289–299. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S229047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim JH, et al. The influence of prior statin use on the prevalence and exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in an adult population. Front Med. 2022;9:842948. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.842948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ingebrigtsen TS, et al. Statin use and exacerbations in individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2015;70(1):33–40. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-205795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dobler CC, Wong KK, Marks GB. Associations between statins and COPD: a systematic review. BMC Pulm Med. 2009;9:32. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-9-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alexeeff SE, et al. Statin use reduces decline in lung function: VA normative aging study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176(8):742–747. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200705-656OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen JH, et al. Protective effects of atorvastatin on cerebral vessel autoregulation in an experimental rabbit model of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Mol Med Rep. 2018;17(1):1651–1659. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.8074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lieberman OJ, Lee S, Zabinski J. Donepezil treatment is associated with improved outcomes in critically ill dementia patients via a reduction in delirium. Alzheimers Dement. 2022 doi: 10.1002/alz.12807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fong TG, Inouye SK. The inter-relationship between delirium and dementia: the importance of delirium prevention. Nat Rev Neurol. 2022;18(10):579–596. doi: 10.1038/s41582-022-00698-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Univariate regression analysis for delirium. Table S2. Univariate regression analysis for 30-day mortality. Table S3. Subgroup analysis of the relationship between statin exposure and delirium in patients with COPD. Table S4. Subgroup analysis of the relationship between statin exposure and 30-day mortality in patients with COPD. Table S5. Baseline characteristics according statin use before or after ICU.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. These data can be found at https://physionet.org/content/mimiciv/2.2.