Abstract

Genomic surveillance of pathogen evolution is essential for public health response, treatment strategies, and vaccine development. In the context of SARS-COV-2, multiple models have been developed including Multinomial Logistic Regression (MLR) describing variant frequency growth as well as Fixed Growth Advantage (FGA), Growth Advantage Random Walk (GARW) and Piantham parameterizations describing variant . These models provide estimates of variant fitness and can be used to forecast changes in variant frequency. We introduce a framework for evaluating real-time forecasts of variant frequencies, and apply this framework to the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 during 2022 in which multiple new viral variants emerged and rapidly spread through the population. We compare models across representative countries with different intensities of genomic surveillance. Retrospective assessment of model accuracy highlights that most models of variant frequency perform well and are able to produce reasonable forecasts. We find that the simple MLR model provides ~0.6% median absolute error and ~6% mean absolute error when forecasting 30 days out for countries with robust genomic surveillance. We investigate impacts of sequence quantity and quality across countries on forecast accuracy and conduct systematic downsampling to identify that 1000 sequences per week is fully sufficient for accurate short-term forecasts. We conclude that fitness models represent a useful prognostic tool for short-term evolutionary forecasting.

Introduction

The emergence of acute respiratory virus SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) and its subsequent circulating variants has had far-reaching implications on global health and worldwide economies [1]. Due to its rapid evolution, original SARS-CoV-2 strains have been replaced by derived, more selectively advantageous variant lineages [2]. This dynamic landscape led to the emergence of Omicron, a highly transmissible and immune evasive variant that rapidly became the dominant strain [3]. It has become increasingly evident that monitoring the evolution and dissemination of these variants remains crucial with SARS-CoV-2 continuing to evolve beyond Omicron [4]. Forecasting variant dynamics allows us to make informed decisions about vaccines and to predict variant-driven epidemics.

Fitness models are a key resource for forecasting changes in variant frequency through time. These models were first introduced for the study of seasonal influenza virus [5–7] and there have relied on correlates of viral fitness such as mutations to epitope sites on influenza’s surface proteins. In modeling emergence and spread of SARS-CoV-2 variant viruses, the use of Multinomial Logistic Regression (MLR) has become commonplace [8–11]. Here, MLR is analogous to a population genetics model of a haploid population in which different variants have a fixed growth advantage and are undergoing Malthusian growth. As such, it presents a natural model for describing evolution and spread of SARS-CoV-2 variants. Additionally, models introduced by Figgins and Bedford [12] and by Piantham et al [13] incorporate case counts and variant-specific , but still can be used to project variant frequencies.

Here, we systematically assess the predictive accuracy of fitness models for nowcasts and short-term forecasts of SARS-CoV-2 variant frequencies. We focus on variant dynamics during 2022 in which multiple sub-lineages of Omicron including BA.2, BA.5 and BQ.1 spread rapidly throughout the world. We compare across several countries including Australia, Brazil, Japan, South Africa, the United Kingdom and the United States to assess genomic surveillance systems with different levels of throughput and timeliness. To assess the performance of these models, we used mean and median absolute error (AE) as a metric to compare the predicted frequencies to retrospective truth. This metric allowed us to evaluate the accuracy and reliability of the models and to identify those that were most effective in predicting SARS-CoV-2 variant frequency. We also examined aspects of country-level genomic surveillance that contribute to errors in these models and explored the role of sequence availability on nowcast and forecast errors through downsampling sequencing efforts for a sample location.

Results

Reconstructing real-time forecasts

We focus on SARS-CoV-2 sequence data shared to the GISAID EpiCoV database [14]. Each sequence is annotated with both a collection date, as well as a submission date. We seek to reconstruct data sets that were actually available on particular ‘analysis dates’, and so we use use submission date to filter to sequences that were available at a specific analysis date. We additionally filter to sequences with collection dates up to 90 days before the analysis date. We categorize each sequence by Nextstrain clade (21K, 21L, etc...) as such clades are generally at a reasonable level of granularity for understanding adaptive dynamics [15]; there are 7 clades circulating during 2022 vs hundreds of Pango lineages. Resulting data sets for representative countries Japan and the USA for analysis dates of Apr 1 2022, Jun 1 2022, Sep 1 2022 and Dec 1 2022 are shown in Figure 1A. We see consequential backfill in which genome sequences are not immediately available and instead available after a delay due to the necessary bottlenecks of sample acquisition, testing, sequencing, assembly and data deposition. Thus, even estimating variant frequencies on the analysis date as a nowcast requires extrapolating from past week’s data. Different countries with different genomic surveillance systems have different levels of throughput as well as different amounts of delay between sample collection and sequence submission [16].

Figure 1. Reconstructing available data sets and corresponding predictions for Japan and USA.

(A) Variant sequence counts categorized by Nextstrain clade from Japan and United States at 4 different analysis dates. (B) +30 day frequency forecasts for variants in bimonthly intervals using the MLR model. Each forecast trajectory is shown as a different colored line. Retrospective smoothed frequency is shown as a thick black line.

We employ a sliding window approach in which we conduct an analysis twice each month (on the 1st and the 15th) and estimate variant frequencies from −90 days to +30 days relative to each analysis date. We illustrate our frequency predictions using the MLR model with Figure 1B showing resulting trajectories for Japan and the US and Figure S1B showing trajectories for Australia, Brazil, South Africa and the UK. Sometimes we see initial over-shoot or under-shoot of variant growth and decline, but there is general consistency across trajectories. Additionally, we retrospectively reconstructed the simple 7-day smoothed frequency across variants and present these trajectories as solid black lines. We treat this retrospective trajectory as ‘truth’ and thus deviations from model projections and retrospective truth can be assessed to determine nowcast and short-term forecast accuracy. Consistent with less available data, we observe that the model predictions for Japan were more frequently misestimated compared to the United States with particularly large differences for clades 22B (lineage BA.5) and 22E (lineage BQ.1) (Fig. 1B).

Model error comparison

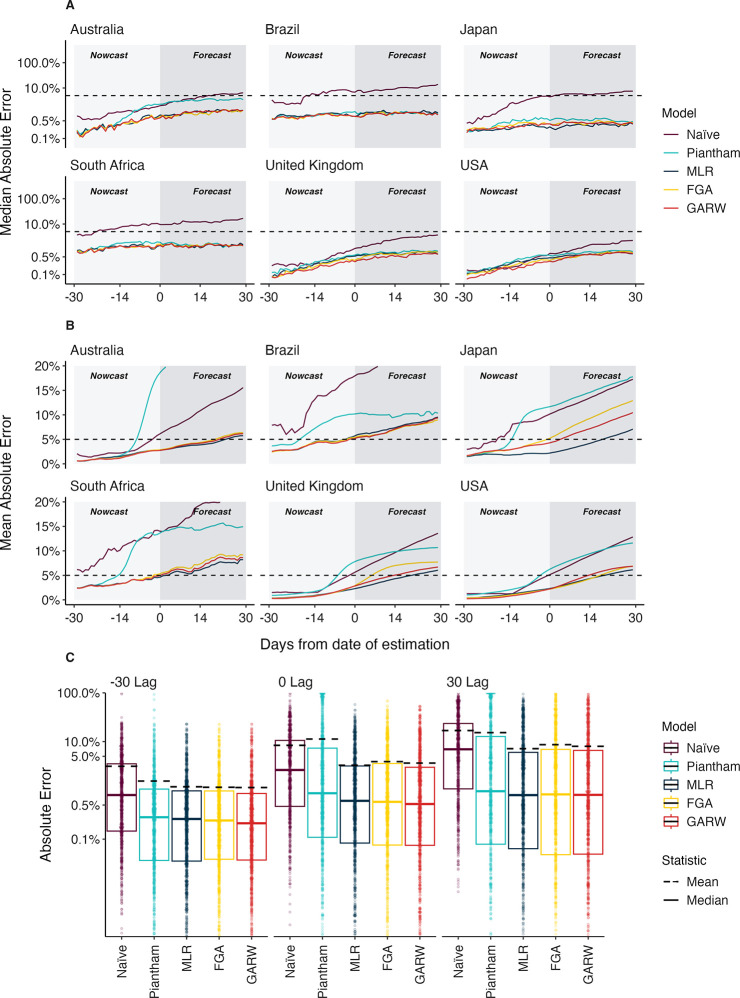

We utilize five models for predicting the frequencies of SARS-CoV-2 variants in six countries (Australia, Brazil, Japan, South Africa, UK and USA). The simplest of these models is Multinomial Logistic Regression (MLR) commonly used in SARS-CoV-2 analyses [8–11], which uses only clade-specific sequence counts and has a fixed growth advantage for each variant. More complex models include the Fixed Growth Advantage (FGA) and Growth Advantage Random Walk (GARW) parameterizations of the variant model introduced by Figgins and Bedford [12], which uses case counts in addition to clade-specific sequence counts. The Piantham et al model [13] operates on a similar principle in estimating variant-specific , but differs in model details. We compare these four models to a naive model to serve as a reference for comparison. The naive model is implemented as a 7-day moving average on the retrospective raw frequencies using the most recent seven days for which sequencing data is available. We compare forecasting accuracy across different time lags from −30 days back from date of analysis to target hindcast date, to +0 days from date of analysis to target nowcast date, to +30 days forward from date of analysis to target forecast date.

We refer to the absolute error for a given model , data set and time as the difference between the retrospective 7-day smoothed frequency and the model predicted frequency (see Methods). We calculate median absolute error and mean absolute error across datasets and across time lags to assess the relative performance of the models for the six countries (Fig. 2, Table 1). As expected, we observe decreasing performance across models as lags increase from −30 days to +30 days. For example, median absolute error increases for the MLR model from 0.1–1% at −30 days, to 0.3–1.4% at 0 days and to 0.4–1.4% at +30 days. Similarly, mean absolute error increases for the MLR model from 0.4–2.3% at −30 days, to 2.2–5.7% at 0 days and to 5.8–9.6% at +30 days. All four forecasting models perform better than the naive model in terms of median absolute error, with MLR and the variant models FGA and GARW performing slightly better than the Piantham variant model, except for in Australia where MLR, FGA and GARW performed decreased error by 2.4% median absolute error compared to Piantham. However, we observe larger differences when comparing mean absolute error across models wherein MLR generally has lowest mean absolute error at +30 days, improving on FGA and GARW by ~1% in most countries. Piantham often shows large errors and mean absolute error is comparable to the naive model at +30 days. Absolute error varies substantially across predictions for individual analysis dates and variants with most predictions having very little error, while a subset of predictions have larger error (Fig. 2C). This skewed distribution results in the large observed differences between median and mean summary statistics.

Figure 2. Absolute error across models, countries and forecast lags.

(A) Median absolute error and (B) mean absolute error across countries, models and forecast lags moving from −30 day hindcasts to +30 day forecasts. For each county / model / lag combination, the median and the mean are summarized across analysis data sets. Panel A uses a log y axis for legibility while panel B uses a natural y axis. (C) Distribution of absolute error on a log scale across models and across forecast lags. Each point represents the absolute error for a data set / country combination. Solid lines show the median of these distributions and dashed lines show the means of these distributions.

Table 1. Median and mean absolute error across models, countries and forecast lags.

Models with the lowest error for each country / lag combination are bolded for clarity.

| Location | Models | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median Absolute Error | Mean Absolute Error | |||||||||

| Naïve | Piantham | MLR | FGA | GARW | Naïve | Piantham | MLR | FGA | GARW | |

| −30 Lead from date of estimation | ||||||||||

| Australia | 0.9% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 2.1% | 0.6% | 0.6% | 0.6% | 0.6% |

| Brazil | 3.4% | 0.5% | 0.5% | 0.7% | 0.7% | 7.5% | 3.5% | 2.3% | 2.2% | 2.3% |

| Japan | 0.4% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 2.9% | 1.3% | 1.4% | 1.5% | 1.5% |

| South Africa | 3.7% | 0.9% | 1.0% | 0.8% | 0.8% | 5.6% | 2.3% | 2.3% | 2.2% | 2.2% |

| USA | 0.2% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 1.3% | 0.9% | 0.4% | 0.3% | 0.2% |

| United Kingdom | 0.2% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 1.5% | 1.0% | 0.4% | 0.4% | 0.4% |

| 0 Lead from date of estimation | ||||||||||

| Australia | 2.0% | 2.3% | 0.9% | 0.7% | 0.7% | 6.1% | 18.6% | 2.8% | 2.9% | 2.7% |

| Brazil | 6.8% | 1.2% | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.8% | 18.0% | 10.2% | 5.7% | 5.4% | 5.2% |

| Japan | 4.5% | 0.5% | 0.3% | 0.4% | 0.4% | 10.2% | 11.7% | 2.2% | 5.2% | 4.3% |

| South Africa | 9.5% | 1.9% | 1.4% | 1.6% | 1.4% | 14.0% | 13.6% | 4.6% | 5.3% | 5.0% |

| USA | 0.7% | 0.6% | 0.5% | 0.4% | 0.3% | 5.1% | 6.2% | 2.3% | 2.2% | 2.2% |

| United Kingdom | 1.1% | 0.6% | 0.5% | 0.4% | 0.3% | 5.6% | 7.8% | 2.3% | 2.9% | 2.8% |

| 30 Lead from date of estimation | ||||||||||

| Australia | 6.5% | 3.8% | 1.4% | 1.4% | 1.3% | 15.9% | 22.8% | 5.8% | 6.4% | 6.2% |

| Brazil | 13.2% | 1.3% | 1.2% | 0.9% | 0.9% | 26.7% | 12.2% | 9.6% | 9.1% | 9.5% |

| Japan | 7.7% | 0.6% | 0.4% | 0.4% | 0.4% | 17.5% | 17.9% | 7.3% | 13.1% | 10.7% |

| South Africa | 15.8% | 1.4% | 1.4% | 1.4% | 1.4% | 23.2% | 15.1% | 8.3% | 9.5% | 8.8% |

| USA | 2.2% | 0.8% | 0.7% | 0.7% | 0.7% | 13.1% | 11.7% | 6.2% | 7.0% | 6.9% |

| United Kingdom | 3.7% | 0.9% | 0.6% | 0.8% | 0.6% | 13.8% | 10.7% | 6.2% | 7.7% | 6.8% |

In observing heterogeneity in prediction accuracy, we hypothesized that error is largest for emerging variants that present a small window of time to observe dynamics and where sequence count data is often rare. We investigate this hypothesis by charting how variant-specific growth advantage estimated in the MLR model varied across analysis dates (Fig. 3). Generally, we see sharp changes in estimated growth advantage in the first 1–3 weeks when a variant is emerging, but then see less pronounced changes. Thus it often takes a couple weeks for the MLR model to ‘dial in’ estimated growth advantage and accuracy will tend to be poorer in early weeks when variant-specific growth advantage is uncertain.

Figure 3. Growth advantage of variants across analysis dates.

Growth advantage is estimated via the MLR model and is computed relative to clade 21K (lineage BA.1).

Genomic surveillance systems and forecast error

Again, using the MLR model, we find that different countries have consistently different levels of forecasting error with forecasts in Brazil and South Africa showing more error than forecasts in the UK and the USA (Fig. 4A). We find that broad statistics describing both quantity and quality of sequence data available in at different analysis timepoints and in different genomic surveillance systems correlates with forecasting error (Fig. 4B–E). Using Pearson correlations we find that poor sequence quality as measured by proportion of available sequences labeled as ‘bad’ by Nextclade quality control [17] correlates slightly with mean AE (Fig. 4B). We find that good sequence quantity as measured by total sequences available at analysis has a moderate negative correlation with mean absolute error (Fig. 4E).

Figure 4. Sequence quantity and quality influence nowcasts error.

(A) Absolute error at nowcast for the MLR model across countries. Points represent separate data sets at different analysis dates. Median and interquartile range of absolute errors are shown as box-and-whisker plots. (B-E) Correlation of sequence quality and sequence quantity metrics with absolute error. Points represent separate data sets at different analysis dates. Correlation strength and significance are calculated via Pearson correlation and are inset in each panel.

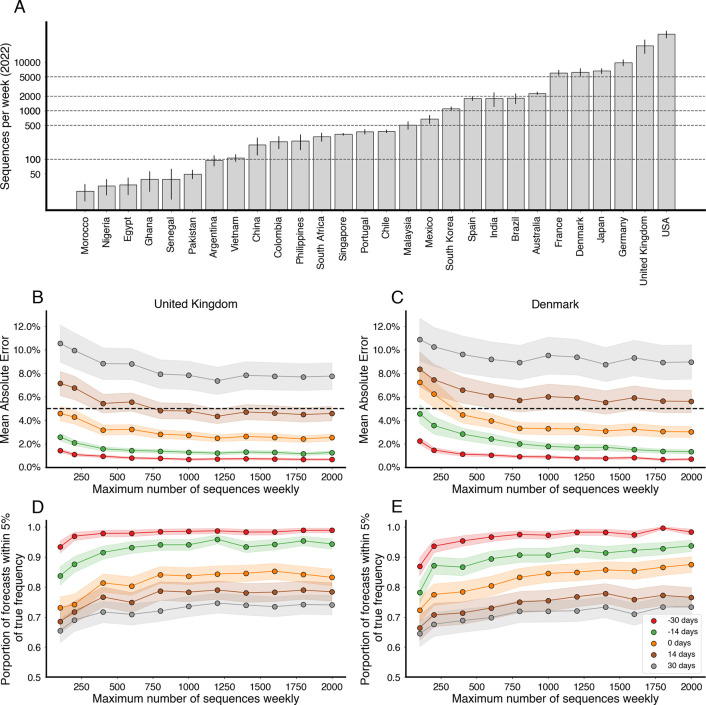

As suggested by these correlations across countries and time points, we expect that as sequencing intensity decreases, our accuracy in forecasting may vary as we have decreasing levels of resolution in current variant frequencies and estimated growth advantages. In order to investigate what number of sequences need to collected weekly to keep forecast error within acceptable bounds, we subsampled existing sequences from the United Kingdom and Denmark. For context, we also computed the mean weekly sequences collected for selected countries globally in 2022 (Fig. 5A). We select the United Kingdom due to its large counts of available sequences, relatively short submission delay, and low forecast error. Additionally, we include Denmark due to its large counts of available sequences and to explore the possibility of stochastic effects due to relative population sizes (Denmark has ~9% the population of the UK). We simulate several downscaled data sets by subsampling the collected sequences at multiple thresholds for number of sequences per week and then fit the MLR model to each of the resulting data sets to see how forecast accuracy varies with sampling intensity. In order to properly account for variability in the subsampled data sets, we generate 5 subsamples per threshold, location and analysis date.

Figure 5. Increasing sequencing intensity reduces forecast error.

(A) Mean sequences collected per week for selected countries in 2022. Intervals are 95% confidence intervals of the mean. Dashed lines correspond to sampling rates used in (B-E). (B, C) Mean absolute error as a function of sequences collected per week colored by forecast horizon (−30 days, −15 days, 0 days, +15 days, +30 days) for the United Kingdom and Denmark. The dash line corresponds to 5% frequency error. (D, E) Proportion of forecasts within 5% of retrospective frequency as a function of sequences collected for week for the United Kingdom and Denmark.

From this analysis, we find that increasing the number of sequences per week generally decreases the average error, but there are diminishing returns (Fig. 5B,D). Additionally, the effect appears to saturate at different values depending on the forecast length. We find that for +14 and +30 day forecasts sampling at least 1000 sequences per week is sufficient to minimize forecast error. We arrive at a similar threshold of 1000 sequences per week for both the UK and Denmark (Fig. 5B–E).

Discussion

In this manuscript we sought to perform a comprehensive analysis of the accuracy of nowcasts and short-term forecasts from fitness models of SARS-CoV-2 variant frequency. We observe substantial differences between median and mean absolute error (Fig. 2, Table 1) with median errors generally quite well contained at 0.4–1.4% in the +30 day forecast, while mean errors are larger at 5.8–9.6%. This difference is due to the highly skewed distribution of model errors (Fig. 2C) where most predictions are highly accurate, but a smaller fraction are off-target. We find that better performing models more often avoid this failure mode of large errors. The Piantham [13] model is the strongest example here, where it shows a similar profile in terms of median absolute error, but performs substantially worse in terms of mean absolute error (Fig. 2, Table 1). Similarly, we observe MLR slightly outperforming FGA and GARW [12] in terms of mean absolute error, but not median absolute error. As expected, errors increase as target shifts from −30 day hindcast to +30 day forecast, but error increases more rapidly for mean absolute error than median absolute error.

We find that the MLR, FGA and GARW models provide systematic and substantial improvements in forecasting accuracy relative to a ‘naive’ model that uses 7-day smoothed frequency at the last timepoint with sequence data (Fig. 2, Table 1). For the MLR model, at +30 days the improvement in median absolute error over naive is 1.5–14.4% and the improvement in mean absolute error is 6.9–17.1%. This result supports the use of MLR models in live dashboards like the CDC Variant Proportions nowcast (covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#variant-proportions) and the Nextstrain SARS-CoV-2 Forecasts (nextstrain.org/sars-cov-2/forecasts/).

We also observe improvements in accuracy for the −30 day hindcast of modeled frequency relative to naive frequency with the MLR model showing improvement in median absolute error of 0.1–2.9% and improvement in mean absolute eror of 0.9–5.2%. These improvements were greatest in countries with lower cadence and throughput of genomic surveillance (Brazil and South Africa). Importantly, this suggests that fitness models are useful for hindcasts in addition to short-term forecasts and that −30 day retrospective frequency should not be taken as truth; it takes more time than 30 days for backfill to resolve retrospective frequency.

We find that variability in forecast errors is partially driven by data limitations. When new variants are emerging, we lack sequence counts and lack time to observe growth dynamics resulting in initial uncertainty of variant growth rates (Fig. 3). Relatedly, analyzing the variation in nowcast error, we find that overall sequence quality and quantity at time of analysis are associated with model accuracy (Fig. 4). Thus, as expected, sequence quality, volume and turnaround time are all important for providing accurate, real-time estimates of variant fitness and frequency. Subsampling existing data in high sequencing intensity countries, we find that there are diminishing returns to increasing sequencing efforts and that maximum accuracy is achieved at around 1,000 sequences per week (Fig. 5). This level of sequencing enables robust short-term forecasts of pathogen frequency dynamics at the level of a country and highlights the feasibility of pathogen surveillance for evolutionary forecasting.

We find that simple fitness models like MLR provide accurate and robust short-term forecasts of SARS-CoV-2 variant frequency. However, these models do not account for future mutations and can only project forwards from circulating viral diversity. This intrinsically limits the effective forecasting horizon achievable by these models. Future modeling work should seek to incorporate the emergence and spread of ‘adjacent possible’ mutations [18]. Without empirical frequency dynamics to draw upon, the fitness effects of these adjacent possible mutations may be estimated from empirical data such as deep mutational scanning [19–21]. Continued timely genomic surveillance and biological characterization along with further model development will be necessary for successful real-time evolutionary forecasting of SARS-CoV-2.

Methods

Preparing sequence counts and case counts

We prepared sequence count data sets to replicate a live forecasting environment using the Nextstrain-curated SARS-CoV-2 sequence metadata [22] which is created using the GISAID EpiCoV database [23]. To reconstruct available sequence data for a given analysis date, we filtered to all sequences with collection dates up to 90 days before the analysis date, and additionally filtered to those sequences which were submitted before the analysis date. These sequences were tallied according to their annotated Nextstrain clade to produce sequence count for each country, for each clade and for each day over the period of interest. Sequence counts were produced independently for the 6 focal countries Australia, Brazil, Japan, South Africa, the United Kingdom and the United States. We repeated this process for a series of analysis dates on the 1st and 15th of each month starting with January 1, 2022 and ending with December 15, 2022 giving a total of 24 analysis data sets for each country. Since three models (FGA, GARW and Piantham) also use case counts for their estimates, we additionally prepare data sets using case counts over the time periods of interest as available from Our World in Data (ourworldindata.org/covid-cases).

Frequency dynamics and transmission advantages

We implemented and evaluated multiple models that forecast variant frequency. These models estimate the frequency variant at time , and simultaneously estimate the variant transmission advantage where is the effective reproduction number for variant and is an arbitrarily assigned reference variant with fixed fitness. We can interpret these transmission advantages as the effective reproduction number of a variant relative to some reference variant.

The four models of interest are: Multinomial Logistic Regression (MLR) of frequency growth and three models of variant-specific : a fixed growth advantage model (FGA) parameterization and a growth advantage random walk (GARW) parameterization of the renewal equation framework of Figgins and Bedford [12], as well as an alternative approach to estimating variant by Piantham et al [13]. We provide a brief mathematical overview of these methods below.

The multinomial logistic regression model estimates a fixed growth advantage using logistic regression with a variant-specific intercept and time coefficient, so that the frequency of variant at time can be modeled as

| (1) |

where is the initial frequency and is the growth rate of variant , and the summation in the denominator is over variants 1 to . Inferred frequency growth can be converted to a growth advantage (or selective coefficient) as assuming an exponentially distributed generation time of .

The model by Piantham et al [13] relies on an approximation to the renewal equation wherein new infections do not vary greatly over the generation time of the virus. This model generalizes the MLR model in that it accounts for non-fixed generation time though it assumes little overall case growth.

The fixed growth advantage (FGA) model uses a renewal equation model based on both case counts and sequence counts to estimate variant-specific assuming that the growth advantage of variant is fixed relative to reference variant [12]. The growth advantage random walk (GARW) model uses the same renewal equation framework and data, but allows variant growth advantages to vary smoothly in time [12].

The models used all differ in the complexity of their assumptions in computing the variant growth advantage. Growth advantages presented in this manuscript are estimated relative to the baseline Omicron 21L (BA.1) strain, providing a point of reference for competing growth advantages and how median values change over time. Further details on the model formats can be found in their respective citations. All models were implemented using the evofr software package for evolutionary forecasting (https://github.com/blab/evofr) using Numpyro for inference.

We compared the four models to a naive model which is implemented as a 7-day moving average on the retrospective raw frequencies at the last timepoint with sequence data.

Evaluation criteria

We calculated the ‘absolute error’ (AE) for a given model and data set as the difference between the retrospective raw frequencies and the predicted frequencies as

| (2) |

where and are the retrospective frequencies and the predicted frequencies for model , data , variant and time . The AE is the mean across individual variants for a specific model, data set and timepoint. Additionally, we often work with the lead time which is defined as the difference between date of analysis for the data set and the forecast date . We summarized median absolute error and mean absolute error across multiple analysis datasets in Figure 2 and Table 1.

Generating predictors of error

We explored four key variables to describe the effect of sequencing efforts on nowcast errors and estimated Pearson correlations with the mean absolute nowcast errors. These variables are defined as proportion of bad quality control (QC) sequences according to Nextclade [17], fraction of sequences available within 14 days of the prediction time, total sequences availability within 14 days of the prediction time and median delay of sequence submission. To calculate these variables, we selected a 14-day window of data before each and every analysis date and used the collection and submission dates to determine their availability. Total sequence availability was calculated by dividing the sequences where submission date was before the date of analysis by the total collected sequences and similarly fraction of sequences at observation was estimated. Sequence submission delay was calculated by taking the difference between the submission date and the date of collection. Bad QC sequence proportion was estimated by dividing the sequences with bad Nextclade classification by the total collected sequences. All estimates were run for all defined dates of analysis across all countries.

Downscaling historical sequencing effort

We explored the effects of scaling back sequencing efforts to assess the effect of sequencing volume on nowcast and forecast errors. Using the sequencing data from the United Kingdom and Denmark, we subsampled existing available sequences at the time of analysis at a rate of 100, 200, 400, 600, 800, 1000, 1200, 1400, 1600, 1800, and 2000 sequences per week for the same analysis dates and study period used in the previous analyses, generating 5 subsampled data sets for each sequencing rate, location, and analysis date. We then fit the MLR forecast model to each resulting data set and forecast up to 30 days after analysis date and compared these forecasts to the truth set in previous sections to compute the forecast error for each model. To better understand how the forecast error varies with sequencing intensity and forecast length, we computed the fraction of forecasts within an error tolerance (5% AE) as well as the average error at different sequence threshold and lag times.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Reconstructing available data sets and corresponding predictions for Australia, Brazil, South Africa and the United Kingdom. (A) Variant sequence counts categorized by Nextstrain clade at 4 different analysis dates. (B) +30 day frequency forecasts for variants in bimonthly intervals using the MLR model. Each forecast trajectory is shown as a different colored line. Retrospective smoothed frequency is shown as a thick black line.

Acknowledgements

We thank John Huddleston for many helpful comments on the approach and on the manuscript. We gratefully acknowledge all data contributors, ie the Authors and their Originating laboratories responsible for obtaining the specimens, and their Submitting laboratories for generating the genetic sequence and metadata and sharing via the GISAID Initiative, on which this research is based. We have included an acknowledgements table in the associated GitHub repository under data/final_acknowledgements_gisaid.tsv.gz. MF is an ARCS Foundation scholar and was supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program under Grant No. DGE1762114. TB is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator. This work is supported by NIH NIGMS R35 GM119774 awarded to TB and by a Howard Hughes Medical Institute COVID Supplement award to TB.

Data and code accessibility

Sequence data including date and location of collection as well as clade annotation was obtained via the Nextstrain-curated data set that pulls data from GISAID database. A full list of sequences analyzed with accession numbers, derived data of sequence counts and case counts, along with all source code used to analyze this data and produce figures is available via the GitHub repository github.com/blab/ncov-forecasting-fit.

References

- 1.Onyeaka H, Anumudu CK, Al-Sharify ZT, Egele-Godswill E, Mbaegbu P (2021) Covid-19 pandemic: A review of the global lockdown and its far-reaching effects. Review Sci Prog 104: 368504211019854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell F, Archer B, Laurenson-Schafer H, Jinnai Y, Konings F, et al. (2021) Increased transmissibility and global spread of sars-cov-2 variants of concern as at june 2021. Euro Surveill 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Viana R, Moyo S, Amoako DG, Tegally H, Scheepers C, et al. (2022) Rapid epidemic expansion of the sars-cov-2 omicron variant in southern africa. Nature 603: 679–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carabelli AM, Peacock TP, Thorne LG, Harvey WT, Hughes J, et al. (2023) Sars-cov-2 variant biology: immune escape, transmission, and fitness. Nat Rev Microbiol 21: 162–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Łuksza M, Lässig M (2014) A predictive fitness model for influenza. Nature 507: 57–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morris DH, Gostic KM, Pompei S, Bedford T, L uksza M, et al. (2018) Predictive modeling of influenza shows the promise of applied evolutionary biology. Trends in microbiology 26: 102–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huddleston J, Barnes JR, Rowe T, Xu X, Kondor R, et al. (2020) Integrating genotypes and phenotypes improves long-term forecasts of seasonal influenza a/h3n2 evolution. Elife 9: e60067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Annavajhala MK, Mohri H, Wang P, Nair M, Zucker JE, et al. (2021) Emergence and expansion of sars-cov-2 b. 1.526 after identification in new york. Nature 597: 703–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faria NR, Mellan TA, Whittaker C, Claro IM, Candido DdS, et al. (2021) Genomics and epidemiology of the p. 1 sars-cov-2 lineage in manaus, brazil. Science 372: 815–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Obermeyer F, Jankowiak M, Barkas N, Schaffner SF, Pyle JD, et al. (2022) Analysis of 6.4 million sars-cov-2 genomes identifies mutations associated with fitness. Science 376: 1327–1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Susswein Z, Johnson KE, Kassa R, Parastaran M, Peng V, et al. (2023) Early risk-assessment of pathogen genomic variants emergence. medRxiv : 2023–01. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Figgins MD, Bedford T (2022) SARS-CoV-2 variant dynamics across us states show consistent differences in effective reproduction numbers. medRxiv : 2021.12.09.21267544. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piantham C, Linton NM, Nishiura H, Ito K (2021) Estimating the elevated transmissibility of the b.1.1.7 strain over previously circulating strains in england using gisaid sequence frequencies. medRxiv. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shu Y, McCauley J (2017) Gisaid: Global initiative on sharing all influenza data - from vision to reality. Euro Surveill 22: 30494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bloom JD, Neher RA (2023) Fitness effects of mutations to SARS-CoV-2 proteins. bioRxiv : 2023.01.30.526314. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brito AF, Semenova E, Dudas G, Hassler GW, Kalinich CC, et al. (2022) Global disparities in sars-cov-2 genomic surveillance. Nature communications 13: 7003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aksamentov I, Roemer C, Hodcroft EB, Neher RA (2021) Nextclade: clade assignment, mutation calling and quality control for viral genomes. Journal of open source software 6: 3773. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kauffman SA (1993) The origins of order: Self-organization and selection in evolution. Oxford University Press, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cao Y, Yisimayi A, Jian F, Song W, Xiao T, et al. (2022) Ba. 2.12. 1, ba. 4 and ba. 5 escape antibodies elicited by omicron infection. Nature 608: 593–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greaney AJ, Starr TN, Bloom JD (2022) An antibody-escape estimator for mutations to the sars-cov-2 receptor-binding domain. Virus evolution 8: veac021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dadonaite B, Brown J, McMahon TE, Farrell AG, Asarnow D, et al. (2023) Full-spike deep mutational scanning helps predict the evolutionary success of sars-cov-2 clades. bioRxiv : 2023–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hadfield J, Megill C, Bell SM, Huddleston J, Potter B, et al. (2018) Nextstrain: real-time tracking of pathogen evolution. Bioinformatics 34: 4121–4123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khare S, Gurry C, Freitas L, Schultz MB, Bach G, et al. (2021) Gisaid’s role in pandemic response. China CDC weekly 3: 1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Reconstructing available data sets and corresponding predictions for Australia, Brazil, South Africa and the United Kingdom. (A) Variant sequence counts categorized by Nextstrain clade at 4 different analysis dates. (B) +30 day frequency forecasts for variants in bimonthly intervals using the MLR model. Each forecast trajectory is shown as a different colored line. Retrospective smoothed frequency is shown as a thick black line.

Data Availability Statement

Sequence data including date and location of collection as well as clade annotation was obtained via the Nextstrain-curated data set that pulls data from GISAID database. A full list of sequences analyzed with accession numbers, derived data of sequence counts and case counts, along with all source code used to analyze this data and produce figures is available via the GitHub repository github.com/blab/ncov-forecasting-fit.