Abstract

We constructed hybrid Bordetella pertussis-Escherichia coli RNA polymerases and compared productive interactions between transcription activators and cognate RNA polymerase subunits in an in vitro transcription system. Virulence-associated genes of B. pertussis, in the presence of their activator BvgA, are transcribed by all variants of hybrid RNA polymerases, whereas transcription at the E. coli lac promoter regulated by the cyclic AMP-catabolite gene activator protein has an absolute requirement for the E. coli α subunit. This suggests that activator contact sites involve a high degree of selectivity.

In Bordetella pertussis, the causative agent of whooping cough, the expression of virulence-associated genes including fhaB, cyaA, and ptx, encoding filamentous hemagglutinin, adenylate cyclase-hemolysin, and pertussis toxin, respectively, is controlled by the BvgA-BvgS two-component system (1, 8, 13, 15, 16, 21). BvgA is a global transcriptional regulator that is phosphorylated by the BvgS sensor kinase (22, 26–28). Phosphorylation of BvgA increases its affinity for target promoter sequences and confers on it the capacity to function as a transcriptional activator at several virulence-regulated promoters (2, 3, 10, 18, 29).

The degree of BvgA phosphorylation differentially affects its DNA binding and transcriptional activation properties (2, 3, 10, 18, 29). In addition, differences in the DNA binding sites for BvgA at various virulence-associated promoters (2, 4, 10, 11, 29) suggest that the specificity of protein-RNA polymerase (RNAP) interactions may control transcriptional activation at these promoters. It has been demonstrated in vitro, with a set of mutated reconstituted Escherichia coli RNAPs, that the C-terminal domain of the α subunit (α-CTD) of E. coli RNA polymerase is required for BvgA-dependent transcription at the fha promoter (4). However, in a recent study we reported that the RNAP ς subunit of B. pertussis confers enhanced expression of fhaB in E. coli (19), indicating that determinants in ς are important for BvgA-dependent transcription in vivo.

The α and major ς subunits of the B. pertussis RNAP have been cloned and characterized (6, 19). These subunits are the most commonly contacted activator targets on the bacterial RNAP (5). To further characterize the BvgA-RNA polymerase interactions responsible for transcriptional activation of B. pertussis virulence genes, we developed an in vitro transcription system using hybrid B. pertussis-E. coli RNAPs containing the α and/or the ς subunits of B. pertussis. We demonstrate the use of this system for the study of RNAP-activator interactions.

Construction of hybrid reconstituted B. pertussis-E. coli RNAPs.

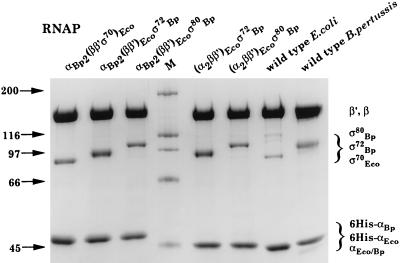

We obtained hybrid reconstituted RNAPs by the method described by Tang et al. for the E. coli RNAP (23, 24). Briefly, each single subunit of the RNAP was overexpressed separately in E. coli BL21. Then, 6 M guanidine hydrochloride extracts containing the different RNAP subunits were prepared, and the core enzyme-containing fractions were mixed. Renaturation of the core enzyme and the sigma-containing fraction was performed by dialysis. The renatured core enzyme and sigma fraction were mixed, and the reconstituted holoenzyme was purified by using Ni2+ affinity chromatography, taking advantage of the fact that the α subunit was His tagged. For overexpression of the E. coli RNAP subunits, we used the vectors described by Tang et al. (24). Overexpression of the B. pertussis RNAP subunits was performed by using the pET/BL21 system (Novagen) with the vectors pES80 and pES70 for the ς subunits and pE6HNαBp for the α subunit. pES80 coding for the major sigma factor, ς80, of B. pertussis and pES70 coding for an N-terminally truncated form of ς80, named ς72, were described earlier (19). pE6HNαBp is a derivative of pET19 (Novagen) containing the sequence of the B. pertussis rpoA gene (6). This construction allowed the obtention of the B. pertussis α subunit with an N-terminal extension including a 6-His tag followed by an enterokinase cleavage site. Reconstitution mixtures containing the α and/or ς80 or ς72 subunit of B. pertussis were performed by using the same protocol as previously described for the E. coli RNAP (23). We constructed and purified the following enzymes: αBp2(ββ′ς70)Eco, αBp2(ββ′)Ecoς72Bp, αBp2(ββ′)Ecoς80Bp, (α2ββ′)Ecoς72Bp, and (α2ββ′)Ecoς80Bp, and typical purities, as measured by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Fig. 1), were about 95%. The transcriptional activities of the hybrid enzymes were very similar to the activity of the wild-type B. pertussis RNAP, with values of approximately 50 U/mg (18), thus demonstrating that heterologous subunits can be successfully assembled to yield functional hybrid RNAPs.

FIG. 1.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis of the purified RNAPs. Samples of the enzymes were separated on a 7.5% gel and stained with Coomassie blue. The compositions of the enzymes are indicated at the top of the figure. Lane M, protein standards (sizes in kilodaltons are shown at left). Subunit assignments for the different RNAPs are at right.

Transcriptional activities of the reconstituted hybrid RNAPs on the trc and lac promoters.

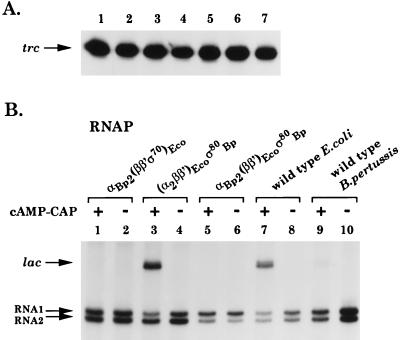

In vitro transcription assays of the strong, artificial trc promoter and of the cyclic AMP-catabolite gene activator protein (cAMP-CAP)-dependent lac promoter, both present on superhelical templates, were performed as described previously (12, 18). As shown in Fig. 2A, the trc promoter is as efficiently transcribed by the hybrid RNAPs as by the wild-type B. pertussis and E. coli enzymes (PhosphorImager measurements indicated that the relative amounts of trc transcripts varied from 70 to 100% compared to the amount yielded by the B. pertussis wild-type RNAP). This result demonstrates the functionality of the hybrid polymerases in an in vitro transcription system. Next we tested their properties on the cAMP-CAP-activatable lac promoter.

FIG. 2.

In vitro transcription of the trc and lac promoters. All reactions were carried out as described earlier (12, 18). Samples were analyzed on denaturing 6% polyacrylamide-6 M urea gels. (A) The trc promoter is activated by all tested RNAPs. The trc transcript is indicated. Lane 1, αBp2(ββ′ς70)Eco; lane 2, αBp2(ββ′)Ecoς72Bp; lane 3, (α2ββ′)Ecoς72Bp; lane 4, αBp2(ββ′)Ecoς80Bp; lane 5, (α2ββ′)Ecoς80Bp; lane 6, wild-type B. pertussis; lane 7, wild-type E. coli. (B) The α subunit of the E. coli RNAP is necessary for activation of the lac promoter. The lac and RNA1 and RNA2 control transcripts are indicated. The RNAP assignments are shown at the top of the panel. The presence (+) or absence (−) of cAMP-CAP is indicated.

The lac promoter was not recognized by the B. pertussis wild-type RNAP in the presence of cAMP-CAP (Fig. 2B, lane 9), whereas the E. coli wild-type RNAP and (α2ββ′)Ecoς80Bp efficiently transcribed the lac promoter in the presence of cAMP-CAP (Fig. 2B, lanes 7 and 3, respectively). The transcription efficiencies were compared to two constitutive transcripts generated by the plasmid vector, RNA1 and RNA2 (12). None of the hybrid RNAPs containing the α subunit of B. pertussis RNAP [αBp2(ββ′ς70)Eco and αBp2(ββ′)Ecoς80Bp] allowed transcription of the lac promoter, whether in the absence or in the presence of cAMP-CAP, whereas RNA1 and RNA2 transcripts were efficiently produced (Fig. 2B, lanes 1 and 5). This result confirms earlier reports (7, 9) that the α subunit of E. coli RNAP is indispensable for transcription of the cAMP-CAP-dependent lac promoter. It also suggests that different specificities regarding activator contact sites exist between the α subunits of B. pertussis and E. coli, despite their striking sequence homologies (see below).

In vitro transcription of bvg-regulated genes.

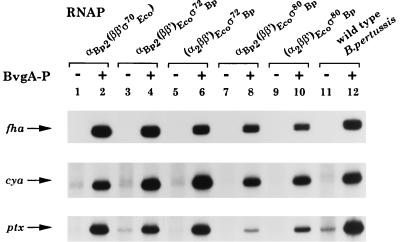

Previously we found that, compared to the B. pertussis RNAP, the E. coli RNAP was much less, if at all, efficient in the transcription of the fha, cya, and ptx promoters in the presence of phosphorylated BvgA (BvgA-P) (18). We therefore performed in vitro transcription assays similar to those performed earlier (18) on the fha, cya, and ptx promoters with the purified hybrid RNAPs. As shown in Fig. 3, all hybrid polymerases allowed transcription at the fha, cya, and ptx promoters in the presence of BvgA-P (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10), and virtually no transcripts were observed in the absence of BvgA-P (lanes 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9). The αBp2(ββ′ς70)Eco enzyme transcribed these promoters almost as efficiently as the wild-type B. pertussis RNAP (Fig. 3, lanes 2 and 12), whereas the ς80-containing hybrid enzymes exhibited lower activities (Fig. 3, lanes 8 and 10). Strikingly, B. pertussis ς80-containing hybrid enzymes were particularly inefficient in transcribing the ptx promoter (lanes 8 and 10). This may be due to specific features in ptx promoter architecture (20) and/or to an inhibiting effect of the N-terminal extension present in the B. pertussis major sigma factor. Indeed, we frequently noted that our wild-type B. pertussis RNAP preparations contained, in part, N-terminally truncated proteolyzed forms of ς80 (18, 19). Nevertheless, when the ς subunit is ς80, stringent ptx promoter interactions might require B. pertussis wild-type RNAP architecture to correctly position the N-terminal extension of ς80. The reduced transcription effect observed with ς80 could be relieved by using hybrid E. coli-B. pertussis RNAPs containing ς72, an N-terminally truncated form of ς80 [(α2ββ′)Ecoς72Bp and αBp2(ββ′)Ecoς72Bp]. Hybrid RNAPs containing ς72 transcribed all three promoters with efficiencies similar to that of the B. pertussis wild-type RNAP (Fig. 3, lanes 4, 6, and 12). Under similar conditions, the transcription efficiencies obtained with wild-type E. coli RNAP for the cya and ptx promoters were about 10 to 15% and for the fha promoter it was about 80% of that obtained with wild-type B. pertussis RNAP (data not shown). Unexpectedly, hybrid RNAPs containing B. pertussis ς factors efficiently transcribed all three virulence-associated promoters in vitro, which was not case when the B. pertussis ς factor replaced a thermosensitive E. coli ς factor in vivo (19).

FIG. 3.

In vitro transcription of bvg-regulated promoters in the presence or absence of BvgA-P. All reactions were carried out as described earlier (18) with slight modifications: the reactions were carried out in 20-μl volumes, BvgA-P was added prior to RNAP, and the reactions were stopped by the addition of 10 μl of formamide loading buffer (17). A total of 10 μl of each reaction mixture was then analyzed on denaturing 6% polyacrylamide-urea gels. RNAP assignments are shown at the top, and the fha, cya, and ptx transcripts are indicated. The presence (+) or absence (−) of BvgA-P is shown. Relative amounts of transcripts were evaluated by PhosphorImager measurements and normalized for the various RNAPs by the respective activities obtained on the trc promoter. Note that levels of transcripts initiated at different promoters are not comparable because of different compositions of messenger RNAs and different film exposure times.

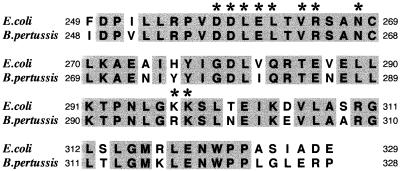

In conclusion, all of the tested hybrid RNAPs, αBp2 (ββ′ς70)Eco, αBp2(ββ′)Ecoς72Bp, αBp2(ββ′)Ecoς80Bp, (α2ββ′)Ecoς72Bp, and (α2ββ′)Ecoς80Bp, were able, in the presence of BvgA-P, to initiate transcription at the fha, cya, and ptx promoters with good efficiencies. This suggests that these polymerases contain all the determinants necessary for in vitro BvgA-dependent transcriptional activation. The high levels of transcription activity obtained with hybrid RNAPs compared to that obtained with wild-type E. coli RNAP could, in part, be accounted for by more than stoichiometric amounts of different ς factors present in the hybrid RNAP preparations (see Fig. 1). Recently, Boucher et al. (4) used the wild type and a set of truncated as well as mutated reconstituted E. coli RNAPs to study BvgA-RNA polymerase interactions at the fha promoter. They reported that under these conditions BvgA-P contacts the α-CTD, especially residues R265 and N268, for transcriptional activation. It has been shown that the same residues are crucial for cAMP-CAP-dependent activation of the lac promoter (14, 25). It is most intriguing that the α subunit of B. pertussis RNAP, in spite of the high overall sequence homology with the corresponding E. coli protein (61% identity), cannot mediate cAMP-CAP-dependent activation of the lac promoter. This result is even more striking because the residues important for E. coli α-CTD and cAMP-CAP interaction at the lac promoter (14, 25) are all conserved, with the exception of one homologous replacement in the B. pertussis α-CTD (Fig. 4). This suggests that the protein-protein contacts between transcriptional-activating regions and the corresponding RNAP targets display a high degree of selectivity. These contacts might be highly optimized and thus specific for one given promoter but completely nonfunctional for other promoters despite the high degree of conservation between the transcriptional machineries. Therefore, the results obtained with the use of heterologous RNAPs to study transcriptional activation of specific promoters should be interpreted with caution.

FIG. 4.

Comparison of amino acid sequences of the α-CTDs of E. coli and B. pertussis. The sequence between residues 249 and 329 of the E. coli α subunit was compared with the corresponding region of the B. pertussis α subunit. The conserved residues are shaded, and the residues important for cAMP-CAP-dependent activation of the lac promoter are marked by asterisks (14, 25).

Acknowledgments

We thank Nick Carbonetti and Roy Gross for kindly providing pNMD120, Hong Tang and Richard Ebright for kindly providing the E. coli RNAP subunits containing plasmids, Annie Kolb for her kind gift of purified CAP and a lac promoter-containing template, Sophie Goyard and Gouzel Karimova for helpful discussions, and Bríd Lefévère-Laoide for critically reading the manuscript.

Financial support came from the Institut Pasteur, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (URA 1129), and the Human Frontier Science Program Organization. P.S. was supported by a fellowship from the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arico B, Miller J F, Roy C, Stibitz S, Monack D, Falkow S, Gross R, Rappuoli R. Sequences required for expression of Bordetella pertussis virulence factors share homology with prokaryotic signal transduction proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:6671–6675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.17.6671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boucher P, Stibitz S. Synergistic binding of RNA polymerase and BvgA phosphate to the pertussis toxin promoter of Bordetella pertussis. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6486–6491. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.22.6486-6491.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boucher P E, Menozzi F D, Locht C. The modular architecture of bacterial response regulators. Insights into the activation mechanism of the BvgA transactivator of Bordetella pertussis. J Mol Biol. 1994;241:363–377. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boucher P E, Murakami K, Ishihama A, Stibitz S. Nature of DNA binding and RNA polymerase interaction of the Bordetella pertussis BvgA transcriptional activator at the fha promoter. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1755–1763. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.5.1755-1763.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Busby S, Ebright R H. Promoter structure, promoter recognition, and transcription activation in prokaryotes. Cell. 1994;79:743–746. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carbonetti N H, Fuchs T M, Patamawenu A A, Irish T J, Deppisch H, Gross R. Effect of mutations causing overexpression of RNA polymerase α subunit on regulation of virulence factors in Bordetella pertussis. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:7267–7273. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.23.7267-7273.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ebright R H. Transcription activation at Class I CAP-dependent promoters. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:797–802. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gross R, Rappuoli R. Positive regulation of pertussis toxin expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:3913–3917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.11.3913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ishihama A. Role of the RNA polymerase α subunit in transcription activation. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:3283–3288. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb02196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karimova G, Bellalou J, Ullmann A. Phosphorylation-dependent binding of BvgA to the upstream region of the cyaA gene of Bordetella pertussis. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:489–496. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.5231057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karimova G, Ullmann A. Characterization of DNA binding sites for the BvgA protein of Bordetella pertussis. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3790–3792. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.11.3790-3792.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kolb A, Kotlarz D, Kusano S, Ishihama A. Selectivity of the Escherichia coli RNA polymerase Eς38 for overlapping promoters and ability to support CRP activation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:819–826. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.5.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laoide B M, Ullmann A. Virulence dependent and independent regulation of the Bordetella pertussis cya operon. EMBO J. 1990;9:999–1005. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08202.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murakami K, Fujita N, Ishihama A. Transcription factor recognition surface on the RNA polymerase α subunit is involved in contact with the DNA enhancer element. EMBO J. 1996;15:4358–4367. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roy C R, Falkow S. Identification of Bordetella pertussis regulatory sequences required for transcriptional activation of the fhaB gene and autoregulation of the bvgAS operon. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2385–2392. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.7.2385-2392.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roy C R, Miller J F, Falkow S. The bvgA gene of Bordetella pertussis encodes a transcriptional activator required for coordinate regulation of several virulence genes. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:6338–6344. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.11.6338-6344.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steffen P, Goyard S, Ullmann A. Phosphorylated BvgA is sufficient for transcriptional activation of virulence-regulated genes in Bordetella pertussis. EMBO J. 1996;15:102–109. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steffen P, Goyard S, Ullmann A. The Bordetella pertussis sigma subunit of RNA polymerase confers enhanced expression of fha in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:945–954. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2741639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stibitz S. Mutations in the bvgA gene of Bordetella pertussis that differentially affect regulation of virulence determinants. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5615–5621. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.18.5615-5621.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stibitz S, Weiss A A, Falkow S. Genetic analysis of a region of the Bordetella pertussis chromosome encoding filamentous hemagglutinin and the pleiotropic regulatory locus vir. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:2904–2913. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.7.2904-2913.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stibitz S, Yang M-S. Subcellular localization and immunological detection of proteins encoded by the vir locus of Bordetella pertussis. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4288–4296. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.14.4288-4296.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tang H, Kim Y, Severinov K, Goldfarb A, Ebright R H. Escherichia coli RNA polymerase holoenzyme: rapid reconstitution from recombinant α, β, β′, and ς subunits. Methods Enzymol. 1996;273:130–134. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)73012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang H, Severinov K, Goldfarb A, Ebright R H. Rapid RNA polymerase genetics: one-day, no-column preparation of reconstituted recombinant Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4902–4906. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.4902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang H, Severinov K, Goldfarb A, Fenyo D, Chait B, Ebright R H. Location, structure, and function of the target of a transcriptional activator protein. Genes Dev. 1994;8:3058–3067. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.24.3058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uhl M A, Miller J F. Autophosphorylation and phosphotransfer in the Bordetella pertussis BvgAS signal transduction cascade. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1163–1167. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.3.1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uhl M A, Miller J F. Central role of the BvgS receiver as a phosphorylated intermediate in a complex two-component phosphorelay. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:33176–33180. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.52.33176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uhl M A, Miller J F. Integration of multiple domains in a two-component sensor protein: the Bordetella pertussis BvgAS phosphorelay. EMBO J. 1996;15:1028–1036. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zu T, Manetti R, Rappuoli R, Scarlato V. Differential binding of BvgA to two classes of virulence genes of Bordetella pertussis directs promoter selectivity by RNA polymerase. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:557–565. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]