Abstract

Introduction

Sexual minoritized people report worse mental health and are at risk of sexual violence compared to their heterosexual peers.

Method

We conducted a survey to explore sexual stigma, sexual violence, and mental health among 326 bi+ and lesbian women and gender minoritized people age 18–25.

Results

Mental health did not differ by sexual identity; sexual stigma and violence were associated with negative mental health symptoms, as were identifying as BIPOC, as trans or nonbinary, or having less formal education.

Conclusion

Sexual stigma and violence are related to mental health among young bi+ and lesbian women and gender minoritized people.

Keywords: Sexual violence, sexual stigma, bisexual, lesbian, mental health

Introduction

Young sexual and gender minoritized people have been found to consistently report worse mental health outcomes in comparison to their heterosexual and cisgender peers (James et al., 2016; Meyer, 2003; Ross et al., 2018). In particular, greater numbers of bisexual women, as well as trans and nonbinary people of all sexual identities, report negative mental health experiences (Ross et al., 2018; Shearer et al., 2016; Tan et al., 2020). These groups also report greater rates of sexual violence in comparison to their monosexual and cisgender peers (Chen et al., 2020; James et al., 2016). Bisexual stigma has been found to be positively related to both reports of sexual violence and worse mental health outcomes among bisexual women and young bisexual people of diverse gender identities (Flanders, Shuler, et al., 2019; Flanders, Anderson, et al., 2019; Flanders et al., 2020; Salim et al., 2019), and sexual violence is associated with significant mental health distress (Chen et al., 2010). As such, we propose that prevalence of sexual violence may account for mental health disparities experienced by women and gender minoritized people who identify as bisexual, and that sexual stigma is an important factor to consider within that relationship. Using a cross-sectional design, the current study investigated the relationships between sexual violence and mental health among young bi+ (i.e., bisexual, pansexual, queer, etc.) and lesbian women and gender minoritized people, while considering the role of sexual stigma.

Mental Health among Sexual Minoritized Women and Gender Minoritized People

Bisexual and lesbian women, including young women, have been found to report worse mental health outcomes in comparison to their heterosexual peers, such as higher rates of suicidality, anxiety, depression (Koh & Ross, 2006; Ross et al., 2018; Salway et al., 2019; Shearer et al., 2016), substance use (Feinstein & Dyar, 2017; Hughes et al., 2010), and PTSD (Alessi et al., 2013). Bisexual women tend to report worse mental health experiences than their lesbian peers, including higher rates of anxiety, depression, PTSD, and suicidality (Alessi et al., 2013; Kerr et al., 2013; Ross et al., 2018; Salway et al., 2019; Shearer et al., 2016; Steele et al., 2009). Further, trans and nonbinary individuals also report heightened levels of negative mental health outcomes in comparison to cisgender people, including psychological distress, suicidality, and depression (Kuper et al., 2020; Veale et al., 2017). There is very little research that has attended explicitly to the mental health experiences of bisexual people who also identify as trans or nonbinary, though it is reasonable to postulate based on the available literature that individuals at this intersection would be vulnerable for negative mental health outcomes as well (Flanders et al., 2020). Though research has consistently identified mental health disparities between bisexual and lesbian people, relatively less research has explicitly investigated what factors might be contributing to the greater burden of negative mental health symptoms experienced by bisexual people. Below we outline some of the factors that may be important to consider in explaining this disparity.

Facilitators of Mental Health Disparities

Sexual stigma.

One of the major factors to negatively impact the mental health of lesbian and bisexual people is sexual identity-based stigma. Brooks (1981) and Meyer (2003) have theorized that the added stress of discrimination based on one’s sexual identity is a major factor for mental health disparities among sexual minoritized people, which has received broad support in minority stress research (Hatzenbuehler, 2009; Tan et al., 2020; Testa et al., 2015). However, the minority stress framework is less able to explain the differences in mental health outcomes between lesbian and bisexual people, as the focus is on the marginalization of a sexual identity by heterosexual society. Ross and colleagues (2018) propose in their meta-analysis of bisexual mental health research that the minority stress framework may better explain bisexual people’s experiences if we account for the qualitative differences in stigma targeting bisexual people, as well as exposure to double discrimination, meaning the bisexual stigma that is enacted by both heterosexual as well as gay and lesbian people (Lambe et al., 2017; Roberts et al., 2015). Qualitative research with young bisexual women has similarly found that some participants reported bisexual-specific stigma, and the experience of double discrimination, as negatively impacting their mental health (Flanders et al., 2015).

Sexual violence.

Another emerging factor that has been found to be associated with both mental health as well as bisexual stigma is experience of sexual violence. Bisexual women consistently report elevated rates of sexual violence compared to lesbian women (Chen et al., 2020; Walters et al., 2013), and have been found to experience more severe sexual violence than lesbian women as ranked by the Koss et al. (2007) Sexual Experiences Scale (Hequembourg et al., 2013). Young bisexual people who identify as trans or nonbinary have also been found to report high levels of sexual victimization (Flanders et al., 2020), as do trans and nonbinary people of all sexual identities (James et al., 2016). Race and ethnicity are also significant factors related to sexual violence, as young Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) bisexual and lesbian people have been found to report higher rates of violence in comparison to white peers (Flanders et al., 2021), and Multiracial, Black, and Indigenous women overall report higher lifetime rates of sexual violence than white women (Black et al., 2010).

Sexual violence is associated with negative mental health sequelae among the general population in the U.S., including increased likelihood of lifetime diagnosis for anxiety, depression, eating disorders, PTSD, sleep disorders, and suicide attempts (Bonomi et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2010). This holds true for sexual minoritized people too, as past research has found sexual victimization significantly predicts increased rates of depression, psychological distress, suicidality, and substance use with sexual minoritized populations (Balsam et al., 2011; Szalacha et al., 2017). Bisexual women have also been found to report greater difficulty in recovering from sexual victimization than heterosexual women (Sigurvinsdottir & Ullman, 2016; Sigurvinsdottir & Ulman, 2015).

Integrating sexual stigma and sexual violence.

Sexual stigma and sexual violence are associated with worse mental health among sexual minoritized people, and double discrimination and elevated rates of sexual violence may both uniquely account for some of the mental health disparity experienced by bisexual people. However, sexual stigma and violence also appear to work in concert with one another, as sexual stigma has been found to significantly predict higher rates of sexual violence among both bisexual and lesbian people (Flanders, Anderson, et al., 2019; Flanders et al., 2020; Martin-Storey & Fromme, 2021; Salim et al., 2020), with rates of sexual stigma and violence significantly higher among bisexual people (Flanders et al., 2021). As such, one potential reason as to why bisexual people report poorer mental health in comparison to lesbian people is the combined experience of sexual stigma and violence. It may be important to include experiences of sexual stigma when investigating the relationship between sexual violence and mental health among sexual minoritized people.

The Current Study

Using a cross-sectional design, the current study aimed to 1) describe the mental health profiles of women and gender minoritized people who identify as either bi+ or lesbian, 2) assess the association between mental health profiles and experiences of sexual violence, and 3) explore the role of sexual stigma in this association.

Materials and Method

The data for this paper come from a larger, cross-sectional mixed-method study on sexual violence with young sexual minoritized women and gender minoritized people (see Flanders et al., 2021). We focus on the quantitative data related to sexual stigma, sexual violence, and mental health for the purposes of this paper. Ethical approval was provided by the Mount Holyoke College IRB.

Participants and Recruitment

A total of 326 lesbian and bi+ (bisexual, pansexual, queer, or other sexual identities describing attraction to more than one gender) people participated in the study. Eligibility criteria for participation included: 1) being age 18–25, 2) living in the U.S. or Canada, 3) identifying broadly as bi+ (attracted to more than one gender) or lesbian (attracted to women only), and 4) identifying as a woman (cis and trans inclusive), or self-identify that the label of “woman” applied to them or their life experience. We recruited participants through the distribution of an online flyer though social media, including paid advertisement campaigns with Facebook. The flyer stated that we were seeking participants who identified as sexual minority women (broadly defined) for a study on identity experiences, sexual health, and mental health. Interested individuals contacted the lead investigator, who then emailed each person with a link to the survey.

Of the total number of participants, 141 (43%) identified as bisexual, 120 (36.6%) as lesbian, 78 (23.8%) as pansexual, and 132 (40.2%) as queer. A majority of the participants identified as cisgender women, with 92 (29.0%) identifying as trans or nonbinary. Most participants identified as non-Hispanic white (221, 67.4%), with a further 25 (7.6%) identifying as Black, 17 (5.2%) as Latinx, and 28 (8.5%) as Multiracial. See Table 1 for more participant demographic information.

Table 1.

Distribution of participant demographics by latent class

| Overall | Class 1: Mental Health Not Clinically Significant (n=158) | Class 2: Clinically Significant Poor Mental Health (n=168) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | (χ2, n, p) | |

| Sexual Identity | (1.48, 326, 0.22) | ||||||

| Lesbian | 109 | 33.4% | 58 | 36.7% | 51 | 30.4% | |

| Bi+ | 217 | 66.6% | 100 | 63.3% | 117 | 69.6% | |

|

| |||||||

| Gender Identity | (8.38, 317, 0.004) | ||||||

| Cisgender woman | 225 | 71.0% | 121 | 78.6% | 104 | 63.8% | |

| Trans and/or non-binary | 92 | 29.0% | 33 | 21.4% | 59 | 36.2% | |

|

| |||||||

| Race/Ethnicity | (10.26, 325, 0.001) | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 219 | 67.4% | 120 | 76.0% | 99 | 59.3% | |

| POC | 106 | 32.6% | 38 | 24.1% | 68 | 40.7% | |

|

| |||||||

| Relationship Status | (0.79, 311, 0.37) | ||||||

| In a relationship | 234 | 75.2% | 117 | 77.5% | 117 | 73.1% | |

| Single | 77 | 24.8% | 34 | 22.5% | 43 | 26.9% | |

|

| |||||||

| Educational Attainment | (9.21, 314, 0.002) | ||||||

| Has not completed college | 196 | 62.4% | 80 | 53.7% | 116 | 70.3% | |

| Completed college | 118 | 37.6% | 69 | 46.3% | 49 | 29.7% | |

Procedures

Upon accessing the survey link, participants were first directed to a short screening form. This form assessed whether they met the eligibility criteria, and asked participants to categorize themselves as either bi+ or lesbian, with the knowledge they would be able to provide more information about their sexual identity later in the survey. If participants met the criteria, they were then routed to the consent form. If not, they were exited from the survey. If participants then gave consent, they were routed to the study survey. All participants were offered a $15 gift card for their participation. Information regarding LGBTQ+ and sexual violence specific mental health support programs was provided in the survey consent form and at the end of the online survey. The lead researcher contact information was also accessible to participants, so they could follow-up if they needed assistance accessing support services related to distress from participation. We also included text at the start of the survey page that included the sexual violence questions that the participants were able to view these questions, and reminded them they could skip any and all questions they did not want to answer. Previous research has found that while some participants experience negative emotions associated with participating in trauma-focused research, that the levels of distress are generally low, and that many participants report benefits from their participation (Jaffe et al., 2015; Yeater et al., 2012).

Materials

Demographic Form

In addition to the screening survey, participants completed a demographic form. The form assessed sexual, gender, and racial/ethnic identities, age, household income, the population density of where they resided, relationship status, and level of formal education.

Sexual Violence Measure

We used a modified version of the Sexual Experiences Scale, Short Form Victimization (SES-SFV; Koss et al., 2007) to measure adult experience of sexual violence. This measure assesses three types of sexual violence, including unwanted sexual contact, verbal coercion, and rape. We utilized five behavior-specific questions to assess for these different types of sexual violence, and modified the language to be more appropriate for sexual and gender minority participants. For example, instead of asking participants whether “A man put his penis into my vagina, or someone inserted fingers or objects without my consent by…,” we asked, “Someone put their penis into my genitals or butt, or someone inserted fingers or objects without my consent by…” These modifications are consistent with recommendations for inclusive research practices (Hipp & Cook, 2017), and have been utilized in other recent research with young bisexual and gender diverse people (Anderson et al., 2019). Consistent with the ordinal scoring outlined by Koss and colleagues (2007), we created six categories to estimate reporting prevalence of types of sexual violence: non-victim (responded 0 times to all items), sexual contact, attempted coercion, coercion, attempted rape, and rape.

Stigma Measure

We used the Anti-Bisexual Experiences Scale (Brewster & Moradi, 2010) to measure bisexual-specific stigma, modified to be appropriate for all included sexual identities, changing the language of “bisexual” to “sexual identity.” An example item includes: “People have treated me as if I am obsessed with sex because of my sexual identity,” for which people would rate on a Likert scale (0 = never to 5 = all of the time) for how they were treated by others (total score range: 0–85). While this measure was developed to evaluate bisexual-specific stigma, prior qualitative research has found that both bi+ and lesbian people report being the targets of stigma captured by this measure (Flanders et al., 2021). The Cronbach’s alpha score for the modified scale was high for the entire sample (a = .942), as well as for the bisexual (a = .954) and lesbian (a = .903) subsamples.

Mental Health Measures

We used a total of four measures of various mental health outcomes, including the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., 2001) for depressive symptoms, the Overall Anxiety Severity and Intensity Scale (OASIS; Campbell-Sills et al., 2009) for anxiety symptoms, the Civilian Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for PTSD symptoms (PCL; Blanchard et al., 1996), and the Suicidal Behavior Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R; Osman et al., 2001) for suicidality.

The PHQ-9 is a 9-item scale that assesses for recent depressive symptoms, and includes items such as whether people experience, “little interest or pleasure in doing things.” Responses range from 0 (not at all), to 3 (nearly every day). In the current study, the scale had excellent reliability among the full sample (a = .908), as well as the bisexual (a = .917) and lesbian (a = .883) subsamples. We dichotomized depression using a cut-point of 10 and greater to indicate potentially clinically-significant depression and scores of 9 or lower indicated no depression (Kroenke et al., 2001).

The OASIS measures recent anxiety symptoms with five items, including, “In the past week, how often did you avoid situations, places, objects, or activities because of anxiety or fear?” Responses are recorded on a 0–4 scale, where higher scores are equated with greater anxiety severity. With the current study, the scale had strong reliability for the overall sample (a = .904), and the bisexual (a = .905) and lesbian (a = .899) subsamples. We dichotomized anxiety using a cut-point of 8 or greater to indicate potentially clinically-significant anxiety and scores of 7 or lower indicated no anxiety (Campbell-Sills et al., 2009).

The PCL for civilians is a 17-item measure that assess for PTSD symptoms. Items include how much people have been recently bothered by things like, “feeling very upset when something reminded you of a stressful experience from the past.” Items are scored from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). In the current study, the scale had excellent reliability among the full sample (a = .946), as well as the bisexual (a = .950) and lesbian (a = .935) subsamples. We dichotomized PTSD using guidance from the Veterans Administration for DSM diagnosis (Weathers et al., 2003).

The SBQ-R is a 4-item measure for different dimensions of suicidality that assesses for lifetime and past year suicide ideation and attempt, frequency of past year suicide ideation, and likelihood of future suicide attempt. It includes items such as “Have you ever thought about or attempted to kill yourself?” Response options range across the different questions; overall scoring is structured so that a higher total score is associated with a greater risk for suicide. In the current study, the scale had strong reliability among the full sample (a = .871), as well as the bisexual (a = .868) and lesbian (a = .873) subsamples. We dichotomized suicide using the cut-point of 7 or greater to indicate past suicidal behavior and scores of 6 or lower indicated no past suicidal behavior (Osman et al., 2001).

Statistical Analysis

Due to the significant correlation between the four mental health measures (r2 range: 0.51–0.73, p<0.0001) and previous evidence on the comorbidity of these mental health conditions (Al-Asadi et al., 2015), we used unconditional latent class analysis (LCA) to identify homogenous, mutually exclusive groups of participants based on whether they reported clinically significant depression (44.92%), anxiety (41.67%), PTSD (45.31%), and suicide (40.99%). While this dichotomization of the mental health outcomes led to a decrease in variance overall, it enabled a more meaningful analysis to consider not only the statistical significance but the clinical significance of the outcome variables. We used standard criteria (i.e., Akaike Information Criteria [AIC], Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC), entropy, class size, and interpretability) to select the best fitting model, which resulted in retaining a two-class solution (AIC: 23.73, BIC: 57.81, entropy: 0.78) over three-class (AIC: 28.60, BIC: 81.62, entropy: 0.77) and four-class (AIC: 38.00, BIC: 109.95, entropy: 0.68) solutions. Moreover, small class sizes (n<30) were present in three- and four-class solutions. We explored using latent profile analysis of continuous scores from the four mental health measures and found that classes identified from the LCA to provide more clinically-relevant information, thus, we present the two-class LCA results here. Additionally, we explored using traditional regression methods to examine the association between type of sexual violence and each of the mental health outcomes and found similar effects between the models, thus LCA allow us to synthesize the common patterns of mental health comorbidities into a single variable to describe mental health in this population and examine the subsequent association with sexual violence experiences.

Using an inclusive maximum-probability approach, we assigned participants to their most likely class based on posterior probabilities of membership in each class. Chi-square tests and unadjusted linear regression models were used to assess demographic, type of sexual violence, and sexual stigma differences between the two mental health latent classes. Logistic regression models were fit to estimate the relationship between mental health and sexual violence experiences, controlling for sexual stigma and covariates. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., 2003).

Results

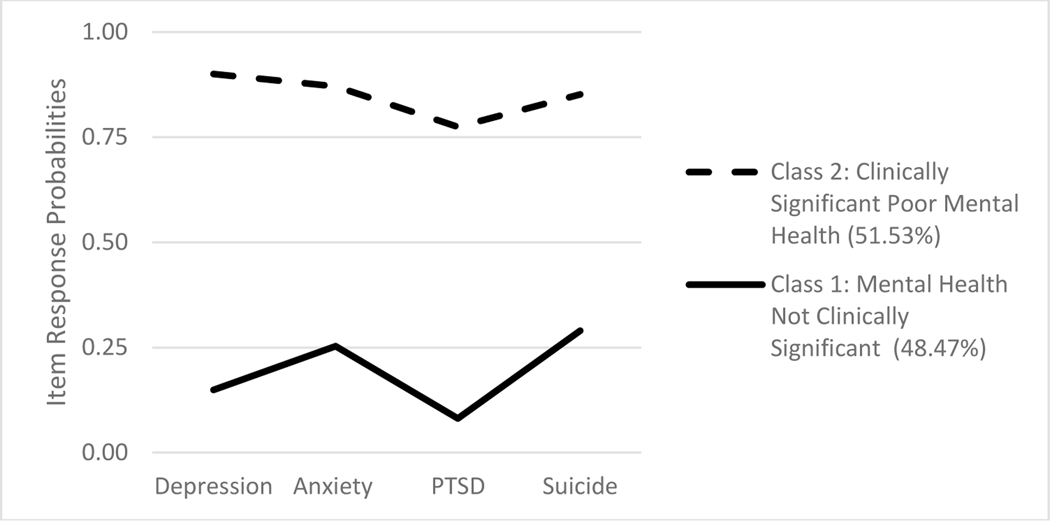

Figure 1 contains the proportion of participants in each latent class and the item response probabilities based on the two-class LCA model. The two classes were roughly equally split. Class 1 (“Mental Health Not Clinically Significant”; 48.47%) was characterized by low probabilities (<0.3) of endorsing all four mental health measures. Class 2 (“Clinically Significant Poor Mental Health”; 51.53%) was characterized by high probabilities (>0.75) of endorsing all four mental health measures.

Figure 1.

Proportion of latent class membership and item response probabilities of retained unconditional two-class solution

Table 1 includes the demographic characteristics of the study sample by the latent classes. There were roughly similar distributions of lesbian and bi+ as well as participants who were single or in a relationship between the two classes. However, cisgender women, non-Hispanic white participants, and participants who completed college were more prevalent in Class 1.

Table 2 provides the distribution of type of sexual violence and sexual stigma by the latent classes. We see statistically significantly higher proportion of participants reporting experiencing the different types of sexual violence in Class 2: Clinically Significant Poor Mental Health. In addition, participants in Class 2 also had higher mean sexual stigma scores than participants in Class 1.

Table 2.

Distribution of Type of Sexual Violence and Sexual Stigma by Latent Class

| Overall | Class 1: Mental Health Not Clinically Significant (n=158) | Class 2: Clinically Significant Poor Mental Health (n=168) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| n | %a | n | %a | n | %a | (χ2, n, p) | |

| Nonvictim | 75 | 23.2% | 50 | 32.1% | 25 | 14.9% | (13.41, 324, <0.001) |

| Sexual Contact | 240 | 74.1% | 99 | 63.5% | 141 | 83.9% | (17.64, 324, <0.001) |

| Attempted Coercion | 143 | 44.3% | 52 | 33.3% | 91 | 54.5% | (14.63, 323, <0.001) |

| Coercion | 147 | 46.1% | 53 | 34.4% | 94 | 57.0% | (16.31, 319, <0.001) |

| Attempted Rape | 116 | 36.5% | 47 | 30.5% | 69 | 42.1% | (4.58, 318, 0.03) |

| Rape | 147 | 45.1% | 57 | 36.1% | 90 | 53.6% | (10.07, 326, 0.002) |

|

| |||||||

| mean | SE | mean | SE | mean | SE | p-valueb | |

| Bi Stigma | 36.9 | 20.2 | 30.8 | 18.5 | 42.6 | 20.3 | <0.001 |

percentages can exceed 100% across the types of sexual violence because respondents could have had more than one type of incident

calculated from unadjusted linear regression models

Regression models examining the association between the mental health latent classes and type of sexual violence experienced are presented in Table 3. Model 1 includes only sexual identity as a covariate, and similar to findings from Table 2, exhibiting Clinically Significant Poor Mental Health was statistically significantly associated with nearly all types of sexual violence (with the exception of attempted rape; OR range: 1.99–3.00). Conversely, Class 2: Clinically Significant Poor Mental Health was associated with a significantly lower odds of being a nonvictim [OR (95% CI): 0.38 (0.22–0.66)] than Class 1: Not Clinically Significant Mental Health. Moreover, bi+ participants were more likely than lesbian participants to experience every type of sexual violence. In Model 2, bisexual stigma was added to the model and this attenuated the association between the mental health latent classes and type of sexual violence; however, the association was still statistically significant for all types of sexual violence, except attempted rape and rape. Bi+ participants were still more likely than lesbian participants to experience almost every type of sexual violence, except for attempted coercion. Bisexual stigma was statistically significantly associated with every type of sexual violence. Finally, in Model 3, we included demographic covariates to the model. Including demographic covariates attenuated the association between the mental health latent classes and type of sexual violence such that this association was no longer statistically significant. The association with sexual violence for bi+ participants was also attenuated and there was no longer a statistically significant difference in attempted rape and rape between bi+ and lesbian participants. Bisexual stigma scores remained statistically significantly associated with type of sexual violence.

Table 3.

Associations between Latent Classes and Type of Sexual Violence from Logistic Regression Models

| Nonvictim | Sexual Contact | Attempted Coercion | Coercion | Attempted Rape | Rape | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

|

|

||||||||||||

| Model 1: adjusted for sexual identity | ||||||||||||

| Latent Classa | ||||||||||||

| Class 1 | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ||||||

| Class 2 | 0.38 | (0.22–0.66)** | 3.00 | (1.74–5.16)*** | 2.35 | (1.49–3.70)*** | 2.49 | (1.56–3.95)*** | 1.58 | (0.99–2.53) | 1.99 | (1.27–3.13)** |

| Sexual Identity | ||||||||||||

| Lesbian | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ||||||

| Bisexual | 0.31 | (0.18–0.54)*** | 3.46 | (2.03–5.91)*** | 1.81 | (1.11–2.95)* | 2.50 | (1.51–4.14)*** | 2.16 | (1.28–3.64)** | 2.06 | (1.27–3.36)** |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Model 2: adjusted for sexual identity and bisexual stigma score | ||||||||||||

| Latent Classa | ||||||||||||

| Class 1 | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ||||||

| Class 2 | 0.50 | (0.28–0.90)* | 2.28 | (1.29–4.04)** | 1.67 | (1.03–2.73)* | 1.78 | (1.08–2.91)* | 1.04 | (0.62–1.74) | 1.48 | (0.92–2.39) |

| Sexual Identity | ||||||||||||

| Lesbian | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ||||||

| Bisexual | 0.34 | (0.19–0.59)*** | 3.21 | (1.85–5.58)*** | 1.45 | (0.87–2.42) | 2.10 | (1.25–3.5)** | 1.76 | (1.02–3.03)* | 1.71 | (1.04–2.83)* |

| Bi Stigma Score | 0.96 | (0.95–0.98)*** | 1.04 | (1.02–1.06)*** | 1.04 | (1.02–1.05)*** | 1.03 | (1.02–1.05)*** | 1.04 | (1.02–1.05)*** | 1.03 | (1.02–1.04)*** |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Model 3: adjusted for sexual identity, bisexual stigma score, and demographic covariates | ||||||||||||

| Latent Classa | ||||||||||||

| Class 1 | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ||||||

| Class 2 | 0.58 | (0.31–1.09) | 1.83 | (0.98–3.39) | 1.61 | (0.94–2.74) | 1.53 | (0.89–2.62) | 0.96 | (0.56–1.66) | 1.30 | (0.99–2.84) |

| Sexual Identity | ||||||||||||

| Lesbian | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ||||||

| Bisexual | 0.37 | (0.20–0.67)** | 2.98 | (1.65–5.38)*** | 1.49 | (0.86–2.59) | 2.22 | (1.26–3.90)** | 1.54 | (0.87–2.72) | 1.68 | (0.99–2.84) |

| Bi Stigma Score | 0.96 | (0.94–0.98)*** | 1.04 | (1.02–1.06)*** | 1.04 | (1.02–1.06)*** | 1.04 | (1.02–1.05)*** | 1.04 | (1.02–1.05)*** | 1.03 | (1.01–1.04)*** |

Class 1: Not Clinically Significant Mental Health; Class 2: Clinically Significant Poor Mental Health

Discussion

Our primary goal was to understand the relationships between sexual violence and mental health among young bisexual and lesbian people, with attention to the role of sexual stigma. We pursued these goals through describing the mental health profiles of our participants, investigating how the experience of sexual violence related to those profiles, and studying the role that sexual stigma played within that relationship.

We first created two latent classes based on participants’ responses to the mental health measures, including Class 1: Non-Clinically Significant Mental Health, and Class 2: Clinically Significant Poor Mental Health, where individuals were classified based on a low (Class 1) or high (Class 2) probability of reporting clinical levels of the four mental health outcomes. In contrast to much of the literature on bisexual mental health (Feinstein & Dyar, 2017; Ross et al., 2018; Salway et al., 2019), we found there was not a significant relationship between sexual identity and latent class, meaning that there were similar proportions of bi+ and lesbian participants in each class. This may in part be due to the strength of the associations between the other demographic variables and mental health outcomes, as well as the explicit focus on younger people, who tend to exhibit more severe mental health symptoms than older adults (Ross et al., 2014). Participants who identified as trans or nonbinary, were BIPOC, or reported lower levels of formal education were more likely to report clinically significant mental health symptoms compared to participants who were cisgender women, non-Hispanic white, and had obtained a Bachelor’s degree or higher. We believe that these findings support the need to conduct intersectional mental health research with young sexual and gender minoritized people to better capture the mental health experiences and needs of these groups (Bowleg, 2012; Ghabrial, 2017; Ghabrial & Ross, 2018).

Next, we found that participants in Class 2: Clinically Significant Poor Mental Health were less likely to report having never experienced sexual violence, and were more likely to report all types of sexual violence compared to Class 1. Further, Class 2 participants reported significantly greater amounts of sexual stigma than Class 1. Though these data are cross-sectional and directionality cannot be determined, these findings align with other research that has found significant negative associations between sexual violence and mental health (Chen et al., 2010; Szalacha et al., 2017), as well as sexual stigma and mental health (Feinstein & Dyar, 2017; Meyer, 2003; Salim et al., 2019). Our findings support that for both bi+ and lesbian young people, sexual violence and sexual stigma are significant factors relative to mental health.

Finally, in the series of regression models we conducted, we found that when adjusting only for sexual identity, participants in Class 2: Clinically Significant Poor Mental Health were significantly more likely to report each type of sexual violence outcome, with the exception of attempted rape. Further, bi+ participants were significantly more likely than lesbian participants to report experiencing each sexual violence outcome, ranging from 1.8 to nearly 3.5 times as likely. These results stayed relatively similar when adjusting for sexual stigma, which was significantly associated with a greater likelihood of reporting each type of sexual violence outcome. However, when the other demographic covariates were added in, there was no longer a significant association between mental health and sexual violence. Bi+ participants were still more likely to report unwanted sexual contact and sexual coercion than lesbian participants, and bisexual stigma was significantly associated with all sexual violence outcomes.

The findings from the regression models provide a nuanced view of the relationships between sexual identity and other important demographic variables, sexual violence, sexual stigma, and mental health. When only accounting for sexual identity, sexual violence was significantly associated with clinically significant poor mental health, aligned with prior research (Alexander et al., 2016; Balsam et al., 2011; Szalacha et al., 2017). When sexual stigma was added, this reduced the strength in the relationship between mental health and sexual violence, which supports past findings wherein sexual stigma was a significant factor in predicting sexual violence and negative mental health outcomes among bisexual and lesbian young people (Flanders, Anderson, et al., 2019; Hatzenbuehler, 2009; Meyer, 2003). Our study expands upon this previous work in combining sexual stigma, sexual violence, and mental health into the same model, which has enabled us to tease apart the different roles these factors play in the mental health of young bi+ and lesbian people. Specifically, sexual stigma appears to be an important factor related to both sexual violence and mental health, but it does not completely diminish the relationship between sexual violence and mental health. Further, the finding that despite greater experience of sexual violence, bi+ participants were not more likely than lesbian participants to report clinically significant mental health symptoms, indicates that sexual violence may differentially impact bi+ people relative to lesbian people. It is possible that bi+ people may have access to different or more effective coping mechanisms, for instance. Finally, our findings indicate that racial identity, level of formal education, and gender identity are critical factors within the relationships between sexual violence and mental health within this sample. This finding aligns with other work that has underlined the importance of intersectional approaches to sexual violence research (McCauley et al., 2019).

Implications for Clinical Practice

Sexual victimization is considered a traumatic event, and for some who experience violence, it is chronic as opposed to one stand-alone event (Thompson et al., 2006). Similarly, sexual stigma is increasingly being understood as a form of trauma, which is also often an ongoing experience for sexual minority people (Arnett III et al., 2019; Keating & Muller, 2020; Balsam, 2002). As such, primary care and mental health providers who work with young bi+ and lesbian people should be informed about how these potentially ongoing forms of trauma may be impacting the health experiences of their sexual minoritized clients, both in order to support recovery as well as to avoid re-traumatization. It is important to focus on both primary care and mental health care, as young bisexual people have described how, particularly related to sexual violence and stigma, they view their sexual health as inseparable from their mental health (Flanders et al., 2017).

We recommend that primary care and mental health providers engage in professional development that supports their training in trauma-informed and anti-oppression perspectives in clinical practice (Cleary & Hungerford, 2015; McIntyre et al., 2012; Reeves, 2015). For example, previous research has found that bisexual people report experiencing biphobia from mental and sexual health providers (Eady et al., 2011; Grant et al., 2020), which may perpetuate negative health symptoms, as well as prevent bisexual people from seeking care in the future (DeLucia & Smith, 2021). Unmet mental health care need is found to be even greater among BIPOC sexual minoritized women, particularly Latinas (Jeong et al., 2016). As such, providing an affirming space for people who have experienced intersectional forms of violence and sexual stigma, and understanding how those two factors may interrelate, could lead to better primary and mental healthcare provision for young bi+ and lesbian people.

Implications for Research

Our primary recommendation for research is that investigations of sexual violence experiences of bi+ and lesbian people should incorporate the ways in which sexual stigma relates to sexual victimization, and that this work should operate from an intersectional perspective. Our findings support prior work that sexual stigma is a critical factor related to the sexual victimization of bi+ and lesbian people (Flanders, Anderson, et al., 2019; Flanders et al., 2020; Salim et al., 2020), and that sexual violence and stigma are associated with mental health outcomes within this population. Further, as participants in the current study who identified as BIPOC, trans or nonbinary, or who had completed less formal education were more likely to report clinical levels of negative mental health symptoms, and as BIPOC and nonbinary people report heightened levels of sexual victimization (Black et al., 2010; James et al., 2016), intersectional approaches to studying the relationships between stigma, sexual violence, and mental health are essential to developing an informed approach to violence prevention and intervention (McCauley et al., 2019). We recommend that future research focuses on longitudinal, intersectional investigations of these experiences in order to develop tailored programs for reducing sexual violence and promoting mental health among young bi+ and lesbian people.

Limitations

A major limitation of the current study is that we only assessed for sexual stigma, and did not ask participants to report on experiences of stigma or discrimination related to other marginalized identities, such as race or gender. Given the significant associations with different demographic categories and mental health, we anticipate that experiences of racism, transphobia, and potentially classism are also significant factors related to participants’ mental health, though we are unable to test those associations with our current data. Another limitation is our modification of a scale designed to measure bisexual-specific stigma with lesbian participants. Though the scale demonstrated good reliability across subgroups of participants, a more thorough assessment of the measure with diverse sexual identity groups is warranted. Third, our data are cross-sectional, and as such we are unable to determine directionality between sexual stigma, sexual violence, and mental health outcomes, however, our findings suggest that future longitudinal research is necessary to determine the temporality between sexual stigma, sexual violence, and mental health outcomes among young bi+ and lesbian people.

Conclusion

Overall, we did not find significant differences in reported mental health among bi+ and lesbian participants, despite the greater likelihood of reporting experience of sexual victimization among bi+ participants. However, BIPOC participants, those who completed less formal education, and trans and nonbinary participants were more likely to report worse mental health outcomes. We did find that reported sexual stigma significantly predicted clinically significant negative mental health, as well as likelihood of reporting sexual violence. When accounting for demographic factors and sexual stigma, sexual violence was no longer significantly associated with mental health outcomes. We believe these findings support the need to focus on sexual stigma in relation to both mental health research as well as sexual violence research among young bi+ and lesbian people.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the American Psychological Foundation Wayne F. Placek grant.

Nicole VanKim was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (Award No. K01 DK123193).

This research was funded by the Wayne F. Placek Grant from the American Psychological Association. Support for this project was also provided by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (Award No. K01 DK123193). The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, CF, upon reasonable request.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no financial interests to disclose.

References

- Al-Asadi AM, Klein B, & Meyer D. (2015). Multiple comorbidities of 21 psychological disorders and relationships with psychosocial variables: A study of the online assessment and diagnostic system within a web-based population. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17(2), e55. 10.2196/jmir.4143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alessi EJ, Meyer IH, & Martin JI (2013). PTSD and Sexual Orientation: An Examination of Criterion A1 and Non-Criterion A1 Events. Psychological Trauma : Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 5(2), 149–157. 10.1037/a0026642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander KA, Volpe EM, Abboud S, & Campbell JC (2016). Reproductive coercion, sexual risk behaviours and mental health symptoms among young low-income behaviourally bisexual women: Implications for nursing practice. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25(23–24), 3533–3544. 10.1111/jocn.13238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RE, Tarasoff LA, VanKim N, & Flanders C. (2019). Differences in Rape Acknowledgment and Mental Health Outcomes Across Transgender, Nonbinary, and Cisgender Bisexual Youth. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 0886260519829763. 10.1177/0886260519829763 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Arnett III JE, Frantell KA, Miles JR, & Fry KM (2019). Anti-bisexual discrimination as insidious trauma and impacts on mental and physical health. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 6(4), 475–485. 10.1037/sgd0000344 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Lehavot K, & Beadnell B. (2011). Sexual revictimization and mental health: A comparison of lesbians, gay men, and heterosexual women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(9), 1798–1814. 10.1177/0886260510372946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Walters ML, Merrick MT, Chen J, & Stevens MR (2010). National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2010 Summary Report (p. 124). National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, & Forneris CA (1996). Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL). Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34(8), 669–673. 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00033-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonomi AE, Anderson ML, Rivara FP, & Thompson RS (2007). Health outcomes in women with physical and sexual intimate partner violence exposure. Journal of Women’s Health (2002), 16(7), 987–997. 10.1089/jwh.2006.0239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L. (2012). The Problem With the Phrase Women and Minorities: Intersectionality—an Important Theoretical Framework for Public Health. American Journal of Public Health, 102(7), 1267–1273. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster ME, & Moradi B. (2010). Perceived experiences of anti-bisexual prejudice: Instrument development and evaluation. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57(4), 451–468. 10.1037/a0021116 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks V. (1981). Minority stress and lesbian women. Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Sills L, Norman SB, Craske MG, Sullivan G, Lang AJ, Chavira DA, Bystritsky A, Sherbourne C, Roy-Byrne P, & Stein MB (2009). Validation of a Brief Measure of Anxiety-Related Severity and Impairment: The Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale (OASIS). Journal of Affective Disorders, 112(1–3), 92–101. 10.1016/j.jad.2008.03.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Walters ML, Gilbert LK, & Patel N. (2020). Sexual violence, stalking, and intimate partner violence by sexual orientation, United States. Psychology of Violence, 10(1), 110–119. 10.1037/vio0000252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LP, Murad MH, Paras ML, Colbenson KM, Sattler AL, Goranson EN, Elamin MB, Seime RJ, Shinozaki G, Prokop LJ, & Zirakzadeh A. (2010). Sexual Abuse and Lifetime Diagnosis of Psychiatric Disorders: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 85(7), 618–629. 10.4065/mcp.2009.0583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary M, & Hungerford C. (2015). Trauma-informed Care and the Research Literature: How Can the Mental Health Nurse Take the Lead to Support Women Who Have Survived Sexual Assault? Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 36(5), 370–378. 10.3109/01612840.2015.1009661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLucia R, & Smith NG (2021). The Impact of Provider Biphobia and Microaffirmations on Bisexual Individuals’ Treatment-Seeking Intentions. Journal of Bisexuality, 0(0), 1–22. 10.1080/15299716.2021.1900020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dianne L. Kerr PhD M, Laura Santurri PhD C, & MA PP (2013). A Comparison of Lesbian, Bisexual, and Heterosexual College Undergraduate Women on Selected Mental Health Issues. Journal of American College Health, 61(4), 185–194. 10.1080/07448481.2013.787619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eady A, Dobinson C, & Ross LE (2011). Bisexual people’s experiences with mental health services: A qualitative investigation. Community Mental Health Journal, 47(4), 378–389. 10.1007/s10597-010-9329-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein BA, & Dyar C. (2017). Bisexuality, minority stress, and health. Current Sexual Health Reports, 9(1), 42–49. 10.1007/s11930-017-0096-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanders CE, Anderson RE, & Tarasoff LA (2020). Young Bisexual People’s Experiences of Sexual Violence: A Mixed-Methods Study. Journal of Bisexuality, 20(2), 202–232. 10.1080/15299716.2020.1791300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanders CE, Anderson RE, Tarasoff LA, & Robinson M. (2019). Bisexual Stigma, Sexual Violence, and Sexual Health Among Bisexual and Other Plurisexual Women: A Cross-Sectional Survey Study. Journal of Sex Research, 56(9), 1115–1127. 10.1080/00224499.2018.1563042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanders CE, Dobinson C, & Logie C. (2015). “I’m Never Really My Full Self”: Young Bisexual Women’s Perceptions of their Mental Health. Journal of Bisexuality, 15(4), 454–480. 10.1080/15299716.2015.1079288 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flanders CE, Dobinson C, & Logie C. (2017). Young bisexual women’s perspectives on the relationship between bisexual stigma, mental health, and sexual health: A qualitative study. Critical Public Health, 27(1), 75–85. 10.1080/09581596.2016.1158786 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flanders CE, Shuler SA, Desnoyers SA, & VanKim NA (2019). Relationships Between Social Support, Identity, Anxiety, and Depression Among Young Bisexual People of Color. Journal of Bisexuality, 19(2), 253–275. 10.1080/15299716.2019.1617543 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flanders CE, VanKim N, Anderson RE, & Tarasoff LA (2021). Exploring potential determinants of sexual victimization disparities among young sexual minoritized people: A mixed-method study. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 10.1037/sgd0000506 [DOI]

- Ghabrial MA (2017). “Trying to Figure Out Where We Belong”: Narratives of Racialized Sexual Minorities on Community, Identity, Discrimination, and Health. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 14(1), 42–55. 10.1007/s13178-016-0229-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghabrial MA, & Ross LE (2018). Representation and erasure of bisexual people of color: A content analysis of quantitative bisexual mental health research. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 5(2), 132–142. 10.1037/sgd0000286 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grant R, Nash M, & Hansen E. (2020). What does inclusive sexual and reproductive healthcare look like for bisexual, pansexual and queer women? Findings from an exploratory study from Tasmania, Australia. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 22(3), 247–260. 10.1080/13691058.2019.1584334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML (2009). How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin, 135(5), 707–730. 10.1037/a0016441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hequembourg AL, Livingston JA, & Parks KA (2013). SEXUAL VICTIMIZATION AND ASSOCIATED RISKS AMONG LESBIAN AND BISEXUAL WOMEN. Violence against Women, 19(5), 634–657. 10.1177/1077801213490557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hipp T, & Cook S. (2017). Rape and Sexual Assault on Campus, in Diverse Populations, and in the Spotlight. 10.4135/9781483399591.n6 [DOI]

- Hughes T, Szalacha LA, & McNair R. (2010). Substance abuse and mental health disparities: Comparisons across sexual identity groups in a national sample of young Australian women. Social Science & Medicine, 71(4), 824–831. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe AE, DiLillo D, Hoffman L, Haikalis M, & Dykstra RE (2015). Does it hurt to ask? A meta-analysis of participant reactions to trauma research. Clinical Psychology Review, 40, 40–56. 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, & Anafi M. (2016). The report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. National Center for Transgender Equality. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong YM, Veldhuis CB, Aranda F, & Hughes TL (2016). Racial/ethnic differences in unmet needs for mental health and substance use treatment in a community-based sample of sexual minority women. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25(23–24), 3557–3569. 10.1111/jocn.13477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating L, & Muller RT (2020). LGBTQ+ based discrimination is associated with ptsd symptoms, dissociation, emotion dysregulation, and attachment insecurity among LGBTQ+ adults who have experienced Trauma. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 21(1), 124–141. 10.1080/15299732.2019.1675222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh AS, & Ross LK (2006). Mental health issues: A comparison of lesbian, bisexual and heterosexual women. Journal of Homosexuality, 51(1), 33–57. 10.1300/J082v51n01_03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Abbey A, Campbell R, Cook S, Norris J, Testa M, Ullman S, West C, & White J. (2007). Revising the SES: A Collaborative Process to Improve Assessment of Sexual Aggression and Victimization. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 31(4), 357–370. 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00385.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, & Williams JB (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuper LE, Bismar D, & Ryan W. (2020, August 7). Transgender Mental Health. The Oxford Handbook of Sexual and Gender Minority Mental Health. 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190067991.013.26 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lambe J, Cerezo A, & O’Shaughnessy T. (2017). Minority stress, community involvement, and mental health among bisexual women. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 4(2), 218–226. 10.1037/sgd0000222 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Storey A, & Fromme K. (2021). Mediating Factors Explaining the Association Between Sexual Minority Status and Dating Violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(1–2), 132–159. 10.1177/0886260517726971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCauley HL, Campbell R, Buchanan NT, & Moylan CA (2019). Advancing Theory, Methods, and Dissemination in Sexual Violence Research to Build a More Equitable Future: An Intersectional, Community-Engaged Approach. Violence Against Women, 25(16), 1906–1931. 10.1177/1077801219875823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre John, Daley Andrea, Rutherford Kimberly, & E R. (2012). Systems-level Barriers in Accessing Supportive Mental Health Services for Sexual and Gender Minorities: Insights from the Provider’s Perspective. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health. 10.7870/cjcmh-2011-0023 [DOI]

- Meyer IH (2003). Prejudice, Social Stress, and Mental Health in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations: Conceptual Issues and Research Evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MS KFB (2002). Traumatic Victimization in the Lives of Lesbian and Bisexual Women. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 7(1), 1–14. 10.1300/J155v07n01_01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman A, Bagge CL, Gutierrez PM, Konick LC, Kopper BA, & Barrios FX (2001). The Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R): Validation with clinical and nonclinical samples. Assessment, 8(4), 443–454. 10.1177/107319110100800409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves E. (2015). A Synthesis of the Literature on Trauma-Informed Care. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 36(9), 698–709. 10.3109/01612840.2015.1025319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts TS, Horne SG, & Hoyt WT (2015). Between a Gay and a Straight Place: Bisexual Individuals’ Experiences with Monosexism. Journal of Bisexuality, 15(4), 554–569. 10.1080/15299716.2015.1111183 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ross LE, Bauer GR, MacLeod MA, Robinson M, MacKay J, & Dobinson C. (2014). Mental Health and Substance Use among Bisexual Youth and Non-Youth in Ontario, Canada. PLoS ONE, 9(8), e101604. 10.1371/journal.pone.0101604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross LE, Salway T, Tarasoff LA, MacKay JM, Hawkins BW, & Fehr CP (2018). Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety Among Bisexual People Compared to Gay, Lesbian, and Heterosexual Individuals:A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. The Journal of Sex Research, 55(4–5), 435–456. 10.1080/00224499.2017.1387755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salim SR, McConnell AA, & Messman-Moore TL (2020). Bisexual Women’s Experiences of Stigma and Verbal Sexual Coercion: The Roles of Internalized Heterosexism and Outness. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 44(3), 362–376. 10.1177/0361684320917391 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salim S, Robinson M, & Flanders CE (2019). Bisexual women’s experiences of microaggressions and microaffirmations and their relation to mental health. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 6(3), 336–346. 10.1037/sgd0000329 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salway T, Ross LE, Fehr CP, Burley J, Asadi S, Hawkins B, & Tarasoff LA (2019). A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Disparities in the Prevalence of Suicide Ideation and Attempt Among Bisexual Populations. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(1), 89–111. 10.1007/s10508-018-1150-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shearer A, Herres J, Kodish T, Squitieri H, James K, Russon J, Atte T, & Diamond GS (2016). Differences in Mental Health Symptoms Across Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Questioning Youth in Primary Care Settings. Journal of Adolescent Health, 59(1), 38–43. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigurvinsdottir R, & Ullman SE (2016). Sexual Assault in Bisexual and Heterosexual Women Survivors. Journal of Bisexuality, 16(2), 163–180. 10.1080/15299716.2015.1136254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigurvinsdottir R, & Ulman SE (2015). The Role of Sexual Orientation in the Victimization and Recovery of Sexual Assault Survivors. Violence and Victims, 30(4), 636–648. 10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-13-00066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele LS, Ross LE, Dobinson C, Veldhuizen S, & Tinmouth JM (2009). Women’s sexual orientation and health: Results from a Canadian population-based survey. Women & Health, 49(5), 353–367. 10.1080/03630240903238685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szalacha LA, Hughes TL, McNair R, & Loxton D. (2017). Mental health, sexual identity, and interpersonal violence: Findings from the Australian longitudinal Women’s health study. BMC Women’s Health, 17. 10.1186/s12905-017-0452-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan KKH, Treharne GJ, Ellis SJ, Schmidt JM, & Veale JF (2020). Gender Minority Stress: A Critical Review. Journal of Homosexuality, 67(10), 1471–1489. 10.1080/00918369.2019.1591789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa RJ, Habarth J, Peta J, Balsam K, & Bockting W. (2015). Development of the Gender Minority Stress and Resilience Measure. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2(1), 65–77. 10.1037/sgd0000081 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RS, Bonomi AE, Anderson M, Reid RJ, Dimer JA, Carrell D, & Rivara FP (2006). Intimate Partner Violence: Prevalence, Types, and Chronicity in Adult Women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 30(6), 447–457. 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veale JF, Watson RJ, Peter T, & Saewyc EM (2017). Mental Health Disparities Among Canadian Transgender Youth. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 60(1), 44–49. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.09.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters ML, Chen J, & Breiding MJ (2013). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2010 Findings on Victimization by Sexual Orientation: (541272013–001) [Data set]. American Psychological Association. 10.1037/e541272013-001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yeater E, Miller G, Rinehart J, & Nason E. (2012). Trauma and Sex Surveys Meet Minimal Risk Standards: Implications for Institutional Review Boards. Psychological Science, 23(7), 780–787. 10.1177/0956797611435131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]