Abstract

Human milk is a rich source of microRNAs (miRNAs), which can be transported by extracellular vesicles and particles (EVPs) and are hypothesized to contribute to maternal-offspring communication and child development. Environmental contaminant impacts on EVP miRNAs in human milk are largely unknown. In a pilot study of 54 mother–child pairs from the New Hampshire Birth Cohort Study, we examined relationships between five metals (arsenic, lead, manganese, mercury, and selenium) measured in maternal toenail clippings, reflecting exposures during the periconceptional and prenatal periods, and EVP miRNA levels in human milk. 798 miRNAs were profiled using the NanoString nCounter platform; 200 miRNAs were widely detectable and retained for downstream analyses. Metal-miRNA associations were evaluated using covariate-adjusted robust linear regression models. Arsenic exposure during the periconceptional and prenatal periods was associated with lower total miRNA content in human milk EVPs (PBonferroni < 0.05). When evaluating miRNAs individually, 13 miRNAs were inversely associated with arsenic exposure, two in the periconceptional period and 11 in the prenatal period (PBonferroni < 0.05). Other metal-miRNA associations were not statistically significant after multiple testing correction (PBonferroni ≥ 0.05). Many of the arsenic-associated miRNAs are involved in lactation and have anti-inflammatory properties in the intestine and tumor suppressive functions in breast cells. Our findings raise the possibility that periconceptional and prenatal arsenic exposure may reduce levels of multiple miRNAs in human milk EVPs. However, larger confirmatory studies, which can apply environmental mixture approaches, evaluate potential effect modifiers of these relationships, and examine possible downstream consequences for maternal and child health and breastfeeding outcomes, are needed.

Keywords: Metals, EVP miRNAs, Human milk, Periconceptional, Prenatal

Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are critical regulators of gene expression and are estimated to impact 60% of protein coding genes (Catalanotto et al. 2016). In addition to influencing gene expression in the cells from which they originate, miRNAs can be transported by extracellular vesicles and particles (EVPs) to distal target tissues (Mori et al. 2019). EVP miRNAs can therefore have long-ranging impacts on gene expression. During pregnancy, EVP miRNAs play important roles in maternal–fetal crosstalk. Dysregulation of these miRNAs has been implicated in the development of pregnancy complications and adverse birth outcomes, including preeclampsia and preterm birth (Menon et al. 2019; Howe et al. 2021a; Salomon et al. 2017; Rodosthenous et al. 2017; Thamotharan et al. 2022). EVP miRNAs in human milk are hypothesized to similarly facilitate maternal-offspring communication during the postnatal period, and a growing number of studies have identified potential roles for human milk-derived miRNAs in offspring health and development, including possible protection against necrotizing enterocolitis and excess adiposity early in life (Zamanillo et al. 2019; Shah et al. 2021; Guo et al. 2022).

Recent evidence suggests that insults during the in utero period, including maternal psychosocial stress, adverse maternal health conditions, and toxicant exposures, alter EVP miRNA levels in human milk (Shah et al. 2021, 2022; Kupsco et al. 2022; Bozack et al. 2022, 2020b; Mirza et al. 2019; Xi et al. 2016), but very little is known about potential impacts of metal exposures. A cohort study in the Faroe Islands which examined multiple marine pollutant exposures, including hair mercury (Hg) concentrations, did not observe any statistically significant associations with EVP miRNA levels in human milk (Kupsco et al. 2022). As yet, the possible influence of other toxic metals and metalloids, such as arsenic (As) and lead (Pb), and essential elements, such as manganese (Mn) and selenium (Se), on EVP miRNA levels in human milk are unknown. Given that mammary tissue undergoes extensive remodeling post-conception in preparation for lactation, including profound changes in miRNA expression, exposures during the periconceptional period may also influence EVP miRNAs in human milk (Wang et al. 2022; Holliday et al. 2018; Roth and Moorehead 2021). However, to our knowledge, this has not been studied. The objective of this pilot study was to investigate whether exposure to multiple toxic and essential elements during the periconceptional and prenatal periods influence EVP miRNA levels in human milk. We examined these relationships in a pregnancy cohort in northern New England which relies on private unregulated drinking water and is therefore particularly susceptible to As and other metal and metalloid exposures.

Methods

Study Participants

This pilot study included 54 mother-infant pairs from the New Hampshire Birth Cohort Study (NHBCS), an ongoing pregnancy cohort of > 2000 mother–child dyads who rely on private water systems as their primary residential water source and received prenatal care at clinics in New Hampshire. Details of this cohort have been described previously (Punshon et al. 2016; Doherty et al. 2020). NHBCS participants provided written informed consent upon enrollment, and all protocols were approved by the Dartmouth College Institutional Review Board. NHBCS mother–child pairs were eligible for the pilot study if (1) the infant had been exclusively breastfed for at least 6 months, (2) breast milk samples had been collected from both the left and right breasts, (3) a maternal blood sample was collected during pregnancy, (4) maternal toenail clippings were collected during pregnancy and postpartum (for metals assessment), and (5) relevant covariate information had been collected (maternal age, pre-pregnancy BMI, smoking during pregnancy, maternal educational attainment, infant sex, delivery type, and gestational age at birth). A total of 80 mother–child dyads met these criteria. We received pilot funding to profile EVP miRNA levels in 54 human milk samples and prioritized participants based on medical record accessibility (for the abstraction of infant anthropometry measures) and sample volumes. Given the breastfeeding eligibility criterion, participants in the pilot study had attained more education on average; were less likely to be overweight or obese prior to the pregnancy; and were less likely to have smoked during pregnancy or to have delivered their baby by cesarean section, compared with the larger cohort (Online Resource 1, Table S1). There was also a higher percentage of female infants in our pilot sample compared with the larger cohort (Online Resource 1, Table S1).

Collection of Toenail Clippings and Metals Assessment

Participants self-collected toenail clippings in mid-pregnancy (median: 27 weeks gestation) and postpartum (median: 5 weeks postpartum). Given the slow growth of toenails, metal concentrations in toenail clippings reflect exposures which occurred approximately 6–12 months prior to sample collection. The prenatal toenail metal measurements used in this study therefore represent metal exposures during the pre-pregnancy through early pregnancy period, while the postpartum toenail metal measurements reflect exposures in early to mid-pregnancy. We refer to these exposure windows as the “periconceptional” and “prenatal” periods hereafter. Details of maternal toenail clipping collection and sample processing, as well as metals assessment have been described previously (Punshon et al. 2016; Doherty et al. 2020). Briefly, at approximately 24–28 weeks gestation and two weeks postpartum, participants received detailed instructions for collecting toenail clippings (Punshon et al. 2016). Participants were instructed to collect their toenail clippings in paper envelopes after bathing and removing any visible dirt. Samples underwent additional washing in the laboratory and were subsequently weighed and digested in Optima nitric acid (Fisher Scientific, St. Louis, Missouri). Metal and metalloid concentrations, which we refer to collectively as “metals”, were measured by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) at the Dartmouth College Trace Element Analysis Core Laboratory. The current analysis focused on three toxic non-essential (As, Hg, Pb) and two essential (Mn, Se) elements, which were selected because there is prior evidence that they impact early growth, an outcome of interest for this pilot study, and they can be measured reliably in toenails (Signes-Pastor et al. 2021, 2019a, 2019b; Krogh et al. 2003; Alfthan 1997; Farzan et al. 2018; Sanders et al. 2014; Zhong et al. 2019; Dack et al. 2021; Wang et al. 2020a; Atazadegan et al. 2022).

Breast Milk Collection and Processing

The NHBCS protocol for breast milk collection has been described previously (Lundgren et al. 2019). Briefly, milk samples were collected by NHBCS participants at their homes. Participants were instructed to express 1–2 oz of milk from the left and right breasts into separate sterile study-provided collection bottles as close to their six-week postpartum visit as possible (mean: 6.1 weeks post-delivery) after their baby’s morning feed. Milk samples were stored in the refrigerator at participants’ homes for a maximum of 24 h, then transported on cold packs to the laboratory where they were immediately chilled and processed within 24 h of receipt. Samples from the left and right breasts were combined prior to processing. Using standard procedures, milk samples were fractionated by centrifugation, and the supernatant fraction was aliquoted and stored at − 80 °C. Milk EVPs are stable after long-term storage in these conditions (Leiferman et al. 2019).34

Extraction and Profiling of EVPs and EVP miRNAs

EVP miRNAs were extracted from 500 μl of the milk supernatant fraction using the Norgen Urine Exosome RNA Isolation kit (Norgen Biotek, Thorold, ON, Canada), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For a subset of milk samples (N = 10), intact EVPs were also isolated from 100 μl of the supernatant fraction using the Norgen Urine Exosome Purification Mini Kit (Norgen Biotek, Thorold, ON, Canada). The size and quantity of the particles extracted using this kit were characterized by a NanoSight NS300 (Online Resource 1, Figure S1). To verify the presence of common extracellular vesicle protein markers, proteomics data were also generated for a subset of the EVP samples (N = 4) by MS Bioworks using LC–MS/MS with a Waters NanoAcquity HPLC system interfaced to a ThermoFisher Fusion Lumos. Multiple proteins which satisfy the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles recommendations for demonstrating the presence of extracellular vesicles were detected (Théry et al. 2018), including members of the tetraspanin family (CD9 and CD63); complement binding proteins (CD59, CD14, CD36); and escort, accessory, and heat shock proteins, such as PDCD6IP (ALIX), RHOA, ANXA2, HSPA8, SDCBP HSPA1A, and actin (Online Resource 2, Table S1). We also detected Kappa-casein, indicating the presence of casein micelles.

A synthetic miRNA spike-in (osa-miR-414) was added during the EVP miRNA extraction step to monitor extraction efficiency. Eluted milk EVP miRNAs were then further purified using Amicon Ultra Centrifugal Filters and concentrated using a speed vacuum concentrator. Quality control and quantification of the purified miRNAs were determined using an Agilent Bioanalyzer Small RNA Chip assay. Bioanalyzer results are shown in Online Resources 3–7. A total of 798 EVP miRNAs were profiled by the Dartmouth Genomics Molecular Biology Shared Resource using the NanoString miRNA Expression Assay Human v3 on the nCounter Analysis System (Seattle, WA, USA). This assay covers 100% of the high confidence human miRNAs in miRBase v22 (Tsang et al. 2017).

Covariate Information

Information about the mother’s highest attained education at enrollment and smoking status during the pregnancy were obtained by questionnaires administered during pregnancy and postpartum. Maternal fish and seafood consumption were determined using a validated food frequency questionnaire administered during pregnancy (Lundgren et al. 2018; Willett et al. 1985). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using maternal height and usual weight when not pregnant. If available, these values were abstracted from the medical records. Otherwise, self-reported values collected by questionnaires administered during pregnancy or postpartum were used. Information on infant’s sex was also abstracted from the medical records.

Statistical Analyses

Raw miRNA counts from the NanoString nCounter platform were normalized to sample-specific positive controls and the miRNA spike-in to account for technical variation in the assay and possible differences in extraction efficiency using the “NanoStringNorm” package in R (version 4.1.0) (Waggott et al. 2012). Analyses focused on (1) total EVP miRNA counts, using data from all 798 of the measured miRNAs and (2) individual miRNAs which fell above the background (mean + 1.5 SD of sample-specific negative controls) for ≥ 60% of participants. Given that major determinants of human milk EVP miRNAs are largely unknown, a principal component analysis (PCA) was performed to reduce the dimensionality of the miRNA data using the “stats” package in R (R: The Stats Package 2022). The first two principal components explained more than 80% of the variance in the miRNA data. Covariates associated with these miRNA principal components with a P < 0.10 were included in statistical models. The following covariates were considered: maternal age, pre-pregnancy BMI, highest attained education level, fish and seafood consumption, infant sex, and infant age at milk collection. Although information on gestational age at birth and delivery type were also collected, these covariates were not considered in statistical models, since they may fall in the causal pathway, and we were not powered to investigate possible mediation in the current study. Metal concentrations were log2-transformed, and both total and individual miRNA counts were natural log-transformed to reduce the influence of extreme values.

Metal-miRNA associations were examined using robust linear regression. Separate models were run for each metal, miRNA, and time point. P-values from each model were adjusted for multiple testing to account for the five metals and two exposure windows (for total miRNA analyses) as well as the 200 miRNAs evaluated (for individual miRNA analyses) using a Bonferroni correction. Statistically significant results (PBonferroni < 0.05) were further inspected using generalized additive models with the “mgcv” package and plotted using the “visreg” package in R to evaluate whether relationships were linear and to identify possible influential observations (Breheny and Burchett 2013; Wood 2017). Final models were adjusted for the following covariates: maternal weight status prior to the pregnancy (overweight/obese compared with healthy/underweight), maternal fish and seafood consumption (servings per week), infant sex, and infant age at milk collection. In sensitivity analyses, we further investigated whether results were similar after additionally adjusting for the timing of toenail collection (days gestation or days postpartum), after excluding one participant who reported smoking during pregnancy, and after additionally adjusting for the duration of time that milk samples had been stored at −80 °C prior to EVP miRNA extraction (median 4.3 years). If total miRNA counts or specific miRNAs were commonly associated with multiple metals or with the same metal exposure across the two time points, we ran additional sensitivity analyses in which both metals or time points were included simultaneously in one model.

Gene Overrepresentation Analyses

Predicted target genes of metal-associated miRNAs (PBonferroni < 0.05) were identified using miRDIP (version 5.0.2.3), which creates a confidence score for predicted target genes using information from 30 databases (Tokar et al. 2018). Predicted target genes with miRDIP scores classified as “very high confidence” (i.e., top 1%) were retained for overrepresentation analyses. The overrepresentation of predicted target genes in PANTHER pathways was evaluated using EnrichR (Kuleshov et al. 2016).44 Pathways with a PFDR < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Participant Characteristics and Toenail Metal Concentrations

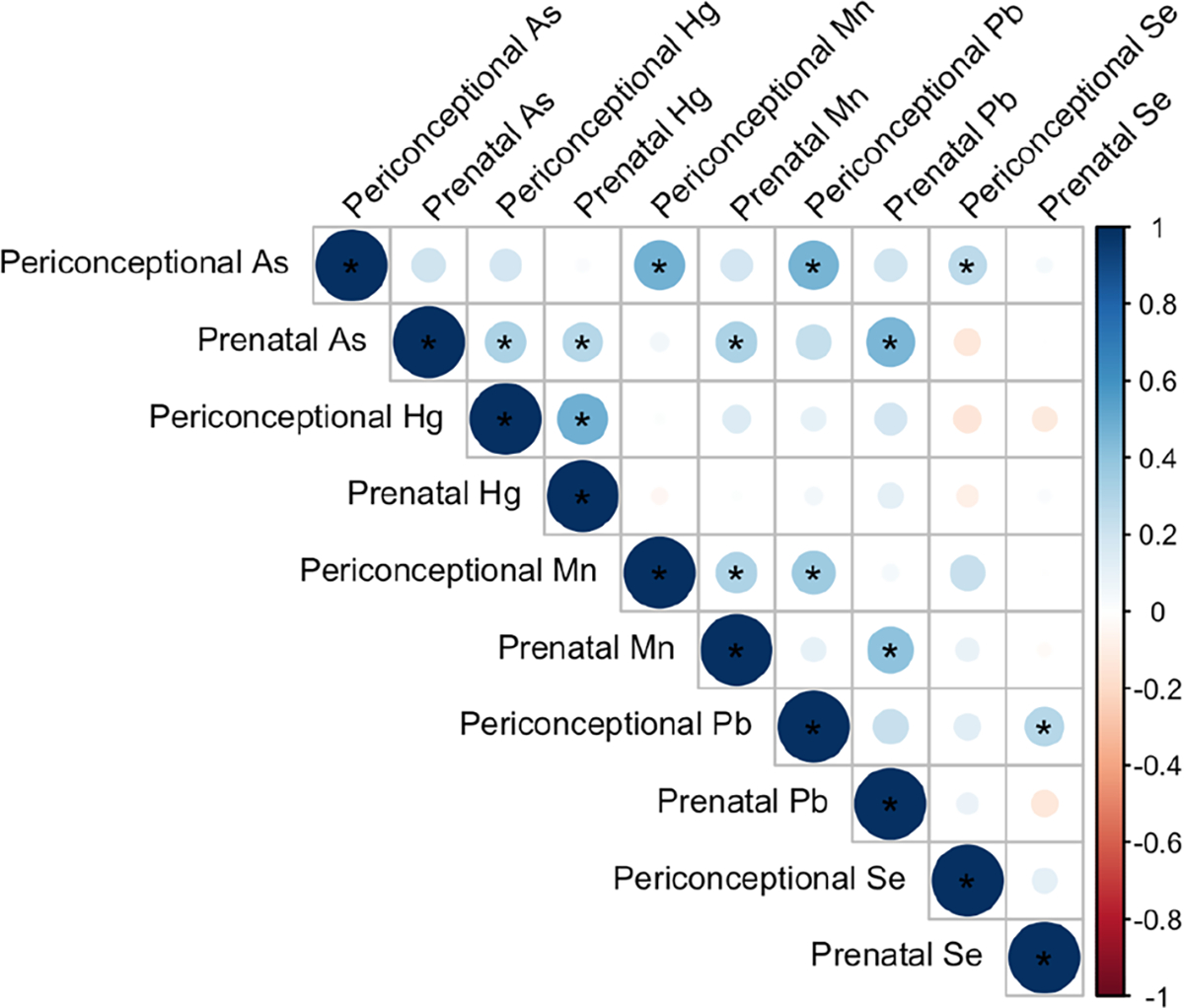

Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1. The mean ± SD age was 32.6 ± 4.0 years. Most participants were a healthy weight prior to the pregnancy (72.2%), and there were more female (55.6%) compared with male (44.4%) infants in the study sample. Toenail metal concentrations did not differ significantly between the periconceptional and prenatal periods (Table 2). Spearman correlations between metal pairs and time points are shown in Fig. 1. Positive correlations were observed between most metals and time points.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Characteristic | Mean ± SD or N (%) | Median (Range) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Maternal characteristics | ||

| Age, Years | 32.6 ± 4.0 | 32.6 (25.4, 43.7) |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI, kg/m2 | 23.9 ± 4.9 | 22.7 (13.2, 46.6) |

| Fish consumption, servings per week | 1.5 ± 1.2 | 1.1 (0.0, 4.7) |

| Pre-pregnancy weight status | ||

| Underweight (< 18.5 kg/m2) | 3 (5.6) | |

| Healthy weight (≥ 18.5 kg/m2 and < 25 kg/m2) | 39 (72.2) | |

| Overweight (≥; 25 kg/m2 and < 30 kg/m2) | 6 (11.1) | |

| Obese (≥ 30 kg/m2) | 6 (11.1) | |

| Educational attainment | ||

| High school graduate or equivalent | 4 (7.4) | |

| Junior college graduate | 3 (5.6) | |

| College graduate | 22 (40.7) | |

| Any post-graduate schooling | 25 (46.3) | |

| Infant characteristics | ||

| Age at milk collection, days | 42 ± 6 | 42 (22, 63) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 30 (55.6) | |

| Male | 24 (44.4) | |

Table 2.

Maternal toenail metal concentrations

| Metal | Periconceptional | Prenatal | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Median (Range) | Median (Range) | P-valuea | |

| As, μg/g | 0.06 (0.02, 0.55) | 0.06 (0.02, 0.27) | 0.38 |

| Hg, μg/g | 0.10 (0.00, 0.41) | 0.09 (0.00, 0.49) | 0.16 |

| Mn, μg/g | 0.48 (0.06, 7.42) | 0.48 (0.04, 6.94) | 0.33 |

| Pb, μg/g | 0.12 (0.05, 1.14) | 0.12 (0.00, 2.61) | 0.79 |

| Se, μg/g | 0.93 (0.63, 1.57) | 0.90 (0.62, 2.77) | 0.18 |

As arsenic, Hg mercury, Mn manganese, Pb lead, Se selenium

P-value is from paired Wilcoxon rank sum test

Fig. 1.

Pairwise correlations (Spearman) between toenail metal concentrations. Positive correlations are shown in blue and negative correlations are shown in red. The sizes and shades of the circles indicate the magnitudes of the correlations, with larger and darker shades representing stronger correlations. *P < 0.05. As arsenic, Hg mercury, Mn manganese, Pb lead, Se selenium

Associations Between Toenail Metal Concentrations and EVP miRNA Levels in Human Milk

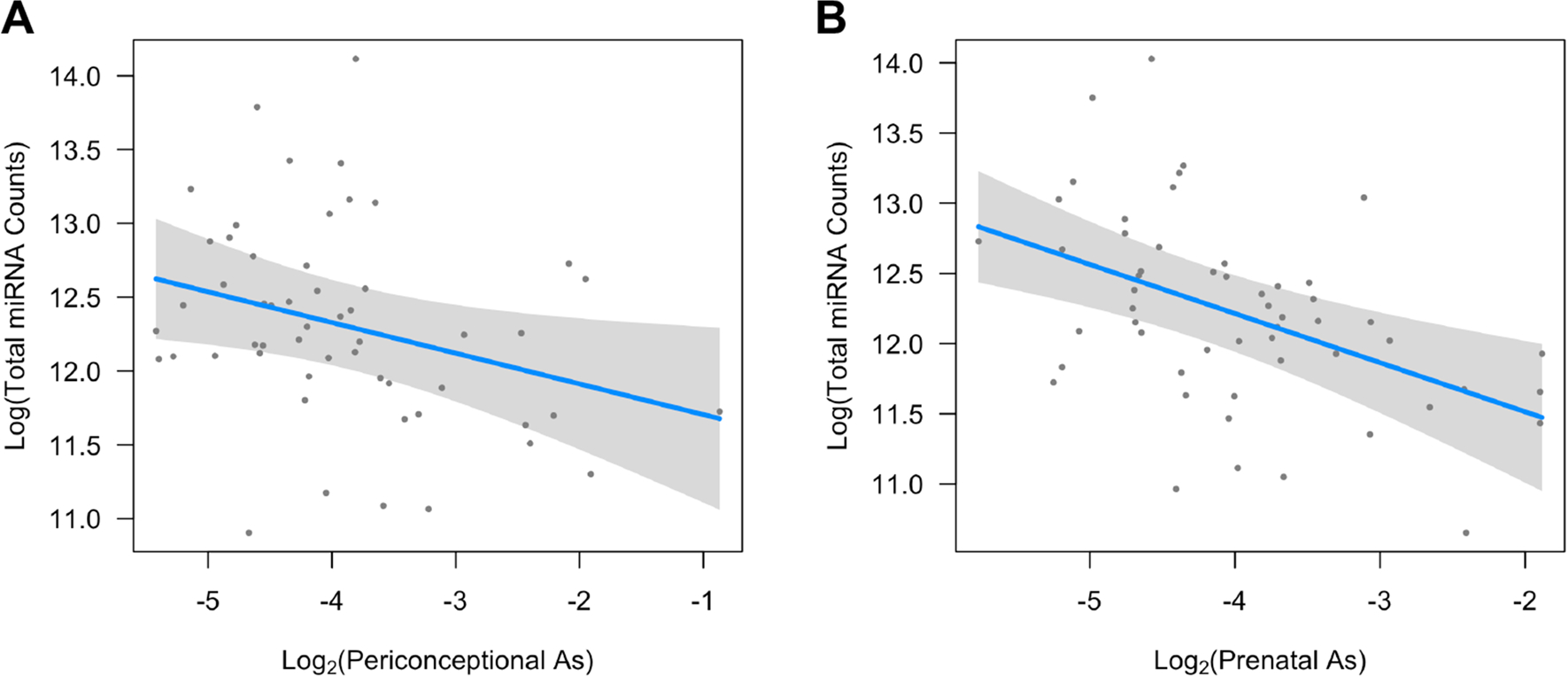

Exposure to As during both the periconceptional and prenatal period was inversely associated with total miRNA levels in milk EVPs after multiple testing correction (Table 3), and these associations appeared linear when using GAMs (Fig. 2). Although similar inverse associations were observed for periconceptional Mn and Pb, they did not remain statistically significant after multiple testing correction (Table 3).

Table 3.

Associationsa between metals and total miRNA levels in human milk EVPs

| Metal | Exposure window | β (95% CI) | P Uncorrected | P FDR | P Bonferroni |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| As | Periconceptional | − 0.21 (− 0.36, − 0.07) | 0.005 | 0.023 | 0.046 |

| As | Prenatal | − 0.33 (− 0.49, − 0.17) | 6.09 × 10−5 | 6.09 × 10−4 | 6.09 × 10−4 |

| Hg | Periconceptional | − 0.07 (− 0.20, 0.06) | 0.280 | 0.467 | 1.00 |

| Hg | Prenatal | − 0.05 (− 0.22, 0.11) | 0.515 | 0.572 | 1.00 |

| Mn | Periconceptional | − 0.13 (− 0.24, − 0.02) | 0.026 | 0.087 | 0.262 |

| Mn | Prenatal | − 0.07 (− 0.18, 0.04) | 0.209 | 0.419 | 1.00 |

| Pb | Periconceptional | − 0.17 (− 0.34, − 0.01) | 0.037 | 0.091 | 0.365 |

| Pb | Prenatal | − 0.02 (− 0.12, 0.07) | 0.638 | 0.638 | 1.00 |

| Se | Periconceptional | − 0.39 (− 1.40, 0.61) | 0.440 | 0.572 | 1.00 |

| Se | Prenatal | − 0.11 (− 0.42, 0.19) | 0.470 | 0.572 | 1.00 |

As arsenic, EVP extracellular vesicles and particles, Hg mercury, miRNA microRNA, Mn manganese, Pb lead, Se selenium

Effect estimates are from robust linear regression models, adjusted for maternal weight status prior to the pregnancy (overweight/obese compared with healthy weight/underweight), maternal fish and seafood consumption (servings per week), infant sex, and infant age at milk collection. Toenail metal concentrations were log2−transformed. Total miRNA counts were log-transformed

Fig. 2.

Generalized additive models showing associations between arsenic (As) exposure during the periconceptional (A) and prenatal (B) periods with total miRNA counts in human milk EVs. Models were adjusted for maternal weight status prior to the pregnancy (overweight/obese compared with normal/underweight), maternal fish and seafood consumption (servings per week), infant sex, and infant age at milk collection. Toenail As concentrations were log2-transformed and total miRNA counts were log-transformed

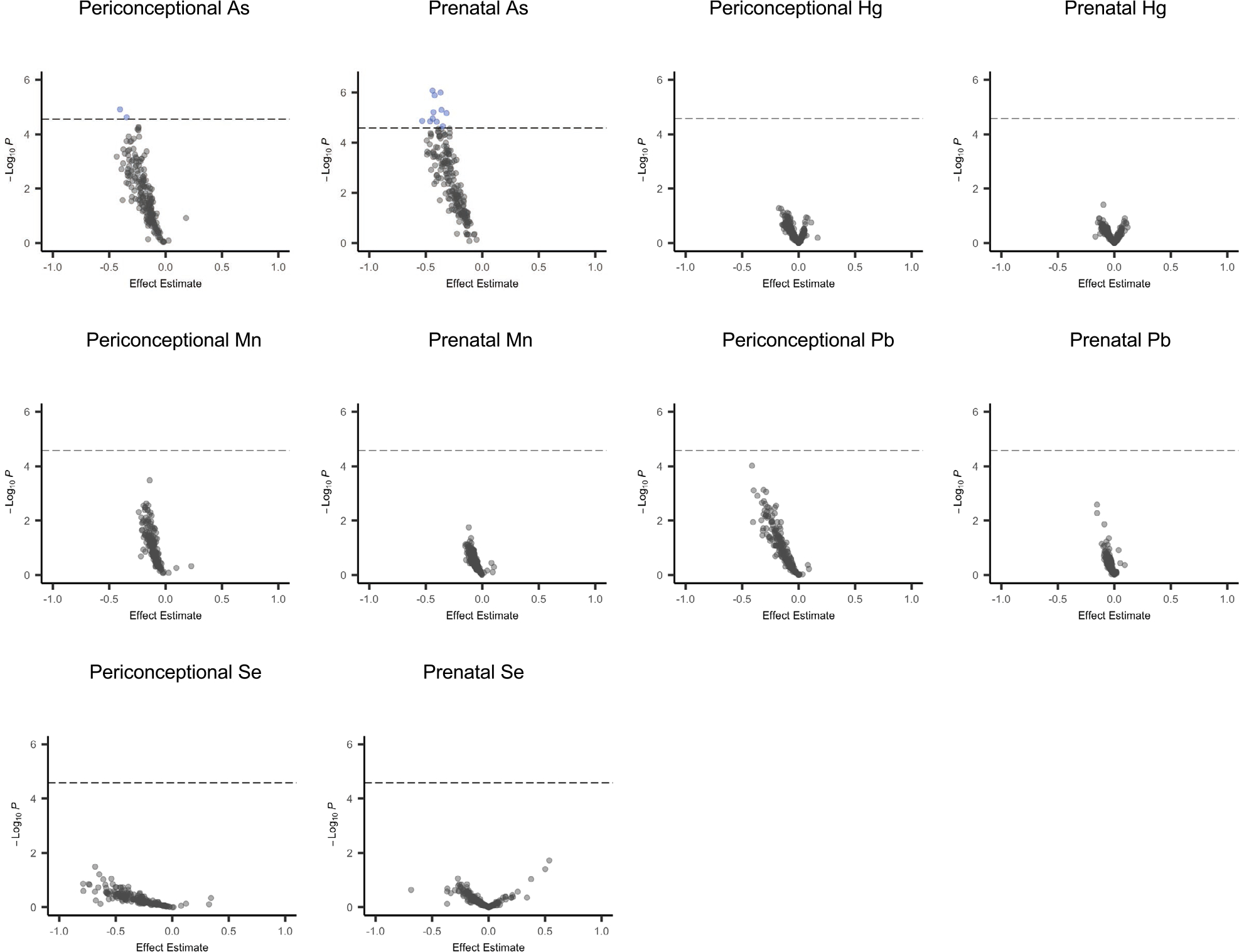

When evaluating miRNAs individually, inverse and statistically significant associations (PBonferroni < 0.05) were identified between periconceptional As and two of the miRNAs examined (miR-182-5p and miR-152-3p), and prenatal As exposure was inversely associated with 11 of the miRNAs examined (miR-200a-3p, miR-34a-5p, let-7b-5p, miR-26b-5p, let-7c-5p, miR-190a-5p, miR-30e-5p, miR-16-5p, miR-146b-5p, miR-497-5p, miR-340-5p) (Fig. 3; Online Resource 2, Table S2). None of the As-associated miRNAs were common across the two exposure windows. Other metal-miRNA associations were not statistically significant after multiple testing correction (PBonferroni ≥ 0.05), although similar inverse trends were observed for many of the miRNAs with both Mn and Pb (Fig. 3; Online Resource 2, Table S2).

Fig. 3.

Volcano plots showing associations between each metal exposure and the 200 miRNAs which met detection thresholds for individual miRNA analyses. Robust linear regression models were adjusted for maternal weight status prior to the pregnancy (overweight/obese versus healthy weight/underweight), maternal fish and seafood consumption (servings per week), infant sex, and infant age at milk collection. Toenail metal concentrations were log2-transformed. MiRNA counts were log-transformed. The dashed line indicates the Bonferroni significance threshold (PBonferroni < 0.05). As arsenic, Hg mercury, Mn manganese, Pb lead, Se selenium

Sensitivity Analyses

Given that As exposure during both the periconceptional and prenatal period was inversely and significantly associated with total EVP miRNA levels (PBonferroni < 0.05), we ran a sensitivity analysis in which the two time points were included simultaneously in one model. Both associations remained statistically significant in this sensitivity analysis (periconceptional As β: − 0.14 (95% CI − 0.26, − 0.01), P = 0.028; prenatal As β − 0.28 (95% CI − 0.44, − 0.13), P = 3.99 × 1 0−4).

For Bonferroni-significant associations, we also investigated the influence of additionally adjusting for the timing of toenail collection and excluding one participant who reported smoking during pregnancy. Effect estimates from these sensitivity analyses were very similar to those from primary analyses (Online Resource 1, Tables S2 and S3). Inverse associations between As exposure and both total and individual EVP miRNA counts also remained statistically significant after additionally adjusting for the duration of time that samples had been stored at −80 °C (Online Resource 1, Table S4 and Table S5).

Given that distinct miRNAs were associated with As exposure during the periconceptional versus prenatal period, we also evaluated whether the change in As exposure across the two time points was associated with any of these miRNAs. However, associations were not statistically significant before or after multiple testing correction (Online Resource 1, Table S6). Additionally, the change in As exposure was not significantly associated with total miRNA levels in human milk EVPs (β: 0.23 (95% CI − 1.64, 2.10), P = 0.809).

Overrepresentation Analyses

A total of 381 predicted target genes were identified for EVP miRNAs that were significantly associated with periconceptional As exposure compared with 1954 predicted target genes for EVP miRNAs that were significantly associated with prenatal As exposure. Of these, 131 genes were commonly identified for the two exposure windows (Online Resource 2, Table S3). Predicted target genes of the two miRNAs associated with periconceptional As exposure were significantly overrepresented (PFDR < 0.05) in six PANTHER pathways (Online Resource 2, Table S4), and predicted target genes of the 11 miRNAs associated with prenatal As exposure were significantly overrepresented (PFDR < 0.05) in 15 PANTHER pathways (Online Resource 2, Table S5). Four pathways were common between the two time points: the TGF-beta signaling pathway, EGF receptor pathway, FGF signaling pathway, and Insulin/IGF pathway-protein kinase B signaling cascade. This overlap was greater than would be expected by chance (P from Fisher’s exact test = 4.7 × 10−4).

Discussion

Recent evidence suggests that environmental and social stressors and maternal health during pregnancy influence EVP miRNA levels in human milk (Shah et al. 2021, 2022; Kupsco et al. 2022; Bozack et al. 2022, 2020b; Mirza et al. 2019; Xi et al. 2016). However, little is known about impacts of metal exposures, which are widespread and influence both maternal and child health (Zhong et al. 2019; Yim et al. 2022; Wang et al. 2020b, 2019; Howe et al. 2020a, b; 2022; Vahter et al. 2020; Bauer et al. 2020). In a pilot study of participants in the NHBCS, we observed that As exposure during the periconceptional and prenatal periods was associated with lower total miRNA levels in human milk EVPs. Although the specific miRNAs that were inversely associated with As exposure at each time point were distinct, their predicted target genes were overrepresented in many of the same pathways.

A growing number of studies have reported that toxic metals, such as As, Hg, and Pb, induce epigenetic dysregulation, including perturbations in miRNA expression (Kupsco et al. 2022; Li et al. 2021; Chen et al. 2017; Harischandra et al. 2018; Howe et al. 2021b; Rager et al. 2014; Sun et al. 2017; Beck et al. 2018; Ruíz-Vera et al. 2019; Pérez-Vázquez et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2015, 2016; Shi et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2016; Lin et al. 2018; Jiang et al. 2014; Deng et al. 2019). In vitro studies have also demonstrated that As and Mn alter EVP miRNA levels (Li et al. 2021; Chen et al. 2017; Harischandra et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2021; Ngalame et al. 2018; Xu et al. 2015). While epidemiologic investigations of metal impacts on EVP miRNAs have been limited, a recent study of mother–child pairs in Los Angeles identified a common set of EVP miRNAs in maternal circulation during pregnancy that were associated with multiple metal exposures (Howe et al. 2021b). To our knowledge, only one study conducted in the Faroe Islands has assessed the relationships between environmental toxicants and EVP miRNAs in human milk (Kupsco et al. 2022). This study evaluated multiple marine pollutants, including Hg measured in maternal hair samples collected at birth (Kupsco et al. 2022). However, other metals and exposure windows were not investigated. Consistent with our findings, Hg exposure was not significantly associated with any of the miRNAs examined after multiple testing correction.

In the current study, our most striking findings were for As exposure, which was inversely and significantly associated with the total quantity of miRNAs in human milk EVPs after a conservative correction for multiple testing. Participants in the NHBCS are particularly vulnerable to As exposure due to their reliance on private wells, which are not regulated and can be naturally contaminated with high concentrations of this toxic metalloid. Arsenic exposure during the prenatal period has been associated with adverse outcomes in the offspring, including reduced fetal growth and cognitive deficits, and prior studies have identified epigenetic dysregulation as a potential mechanism underlying As toxicity (Yim et al. 2022; Bauer et al. 2020; Howe et al. 2020a; Bozack et al. 2020a). Most of these studies focused on As-associated alterations in DNA methylation. However, epidemiologic and in vitro studies have also reported potential impacts of As exposure on miRNA expression in diverse tissues and cell types, including breast cancer cells (Rager et al. 2014; Sun et al. 2017; Beck et al. 2018; Ruíz-Vera et al. 2019; Pérez-Vázquez et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2015, 2016; Shi et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2016; Rahman et al. 2018; Si et al. 2015). It is therefore possible that As influences miRNA expression in the mammary epithelium, which is thought to be the main source of EVP miRNAs in human milk (Alsaweed et al. 2016a). Interestingly, periconceptional and prenatal As exposure remained significantly associated with the total miRNA content of human milk EVPs when included simultaneously in one model, which suggests that milk miRNAs may be sensitive to As exposure during both of these developmental periods. This is plausible, as mammary tissue undergoes substantial changes post-conception in preparation for lactation, including reprogramming of the epigenome, and this continues throughout pregnancy and into the postpartum period (Oakes et al. 2006; Feigman et al. 2020). Although the specific miRNAs associated with As during each exposure window were unique, their predicted target genes were enriched in several of the same biological pathways, including the TGF-beta signaling pathway, EGF receptor pathway, FGF signaling pathway, and the Insulin/IGF pathway-protein kinase B signaling cascade. Importantly, the TGF-beta signaling pathway regulates mammary gland involution (Bierie et al. 2009), and the EGF Receptor pathway is essential for proper development of the intestinal mucosa during the early postnatal period (Dvorak 2010). Arsenic-associated perturbations in these pathways could therefore have important consequences for lactation and maternal and child health.

Many of the miRNAs that were inversely associated with As exposure in our pilot study are found in large quantities in human milk (Herwijnen et al. 2018). For example, miR-182-5p, miR-200a-3p, let-7b-5p, and let-7c-5p rank among the most abundant miRNAs in milk EVPs from humans and other mammalian species (Herwijnen et al. 2018). Our top hit (miR-200a-3p) is also highly expressed in the mammary epithelium starting in late pregnancy, with expression peaking during lactation, and contributes to the regulation of mammary gland development during these periods (Roth and Moorehead 2021; Zhang et al. 2014).19,81 Potential roles in milk fat (miR-200a-3p, miR-30e-5p, miR-497-5p) and lactose (miR-182-5p) biosynthesis in the mammary gland have also been identified for many of the miRNAs that were inversely associated with As exposure in our pilot study (Chen et al. 2016, 2020; Lin et al. 2013; Alsaweed et al. 2016b). In addition to possible roles in lactation, several of the As-associated miRNAs may reduce intestinal inflammation and protect against necrotizing enterocolitis. For example, miR-200a-3p levels were reported to be lower in the bowel tissue and serum of infants with necrotizing enterocolitis compared with healthy controls (Liu et al. 2021). This miRNA also reduced inflammation and intestinal tissue damage in a mouse model of necrotizing enterocolitis (Liu et al. 2021). Additionally, in a mouse model of inflammatory bowel disease, lower liver and cecal levels of miR-200a-3p were observed, concurrent with increased disease severity, when animals were fed extracellular vesicle- and miRNA-depleted milk (Wu et al. 2019). MiR-146b-5p, another miRNA that was inversely associated with As exposure in our pilot, also reduced intestinal inflammation and improved intestinal barrier function in a mouse model of colitis (Nata et al. 2013).88

Studies in mice have demonstrated that extracellular vesicle miRNAs in milk, including those associated with As exposure, are also transported across the intestinal mucosa and may reach and influence peripheral target tissues in the offspring (Las et al. 2022). Thus, EVP miRNAs in human milk may have additional health benefits beyond their anti-inflammatory roles in the gut. Although human studies investigating relationships between human milk EVP miRNAs and children’s health have been limited, two small pilot studies identified a subset of miRNAs in human milk that were associated with measures of infant growth and adiposity (Zamanillo et al. 2019; Shah et al. 2022). Negative correlations were observed between infant BMI and two of the miRNAs (let-7c-5p and miR-146b-5p) that were inversely associated with As exposure in our pilot study (Zamanillo et al. 2019).

A large fraction of the miRNAs that were inversely associated with As exposure in our study have also been identified as possible tumor suppressors and therapeutic targets in the context of breast cancer (e.g., miR-16-5p, miR-200a-3p, miR146b-5p, miR-152-3p, miR-26b-5p, miR-34a-5p, miR-340-5p) (Roth and Moorehead 2021; Ramalho-Carvalho et al. 2018; Ge et al. 2017; Lai et al. 2021; Li et al. 2020; Ma et al. 2021; Haghi et al. 2019; Eades et al. 2011; Aydoğdu et al. 2012; Qu et al. 2017; Mohammadi-Yeganeh et al. 2016). Given that EVP miRNAs in human milk primarily originate in the mammary gland, they may serve as indicators of breast health during lactation and could possibly be used as non-invasive biomarkers of breast cancer. However, while As is an established cause of lung, skin, and bladder cancers, associations with breast cancer have been inconsistent (Pullella and Kotsopoulos 2020). Possible implications for breast cancer risk are therefore currently unclear.

Strengths of our study include the extensive measurement of miRNAs in human milk EVPs and multiple metal exposures across two sensitive exposure windows. An additional strength is our use of metal measurements in toenail clippings. Given that toenail metal concentrations reflect long-term exposures, we were able to prospectively investigate impacts of metals during critical developmental periods on human milk EVP miRNAs. Additionally, since toenails primarily accumulate inorganic As, our findings are less susceptible to possible confounding from fish and seafood consumption, which is a source of non-toxic organic arsenicals (Signes-Pastor et al. 2021). Our study also has important limitations. Because this was a pilot study, the sample size was small. This may have limited statistical power, which could explain some of the null results for metals other than As. This also precluded our ability to simultaneously investigate multiple metal exposures using mixture modeling approaches, which generally require larger sample sizes, and to evaluate possible differences by infant sex and pre-pregnancy BMI, which may modify metal-miRNA relationships. Given that the NHBCS is a predominantly non-Hispanic white population located in rural New England and reflects As concentrations in the low-to-moderate range, our findings also need to be validated in other populations both within and outside of the USA to determine if results are generalizable.

In conclusion, in a pilot study of rural mother–child pairs relying on private unregulated drinking water, As exposure during both the periconceptional and prenatal periods was associated with lower miRNA levels in human milk EVPs. Several of these As-associated miRNAs are highly expressed in the mammary gland during pregnancy and lactation, play important roles in milk production, and protect against intestinal inflammation. Many of the As-associated miRNAs have also been identified as tumor suppressors and potential targets for breast cancer prevention and treatment. Arsenic-associated reductions in human milk EVP miRNA levels may therefore have possible consequences for lactation, in addition to maternal and child health. While these findings provide compelling preliminary evidence that arsenic may reduce EVP miRNA levels in human milk, larger confirmatory studies will be needed to address these limitations and to additionally examine possible downstream effects on maternal and child health and breastfeeding outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the NHBCS families and cohort study staff. Without them, this research would not be possible.

Funding

This research was supported by NIH Grants P20 GM104416, UH3 OD023275, P01 ES022832, P42 ES007373, R01 HL151385, and EPA Grant RD 83544201. Dr. Howe is supported by an NIEHS Pathway to Independence Award (R00 ES030400).

Footnotes

Competing Interests The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical Approval Study protocols were approved by the Dartmouth College Institutional Review Board.

Consent to Participate Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent to Publish The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent for publication of study results which utilized biospecimens and data collected through their participation in the NHBCS.

Supplementary Information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s12403-022-00520-1.

Data Availability

The miRNA data generated for this study will be made available in GEO upon publication of this manuscript.

References

- Alfthan GV (1997) Toenail mercury concentration as a biomarker of methylmercury exposure. Biomarkers 2(4):233–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsaweed M, Lai CT, Hartmann PE, Geddes DT, Kakulas F (2016a) Human milk miRNAs primarily originate from the mammary gland resulting in unique miRNA profiles of fractionated milk. Sci Rep 6:1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsaweed M, Lai CT, Hartmann PE, Geddes DT, Kakulas F (2016b) Human milk cells contain numerous mirnas that may change with milk removal and regulate multiple physiological processes. Int J Mol Sci 17(6):E956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atazadegan MA, Heidari-Beni M, Riahi R, Kelishadi R (2022) Association of selenium, zinc and copper concentrations during pregnancy with birth weight: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Trace Elem Med Biol 69:126903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aydoğdu E, Katchy A, Tsouko E, Lin CY, Haldosén LA, Helguero L, Williams C (2012) MicroRNA-regulated gene networks during mammary cell differentiation are associated with breast cancer. Carcinogenesis 33(8):1502–1511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer JA, Fruh V, Howe CG, White RF, Henn BC (2020) Associations of metals and neurodevelopment: a review of recent evidence on susceptibility factors. Curr Epidemiol Rep 7(4):237–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck R, Bommarito P, Douillet C, Kanke M, Del Razo LM, García-Vargas G, Fry RC, Sethupathy P, Stýblo M (2018) Circulating miRNAs associated with arsenic exposure. Environ Sci Technol 52(24):14487–14495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierie B, Gorska AE, Stover DG, Moses HL (2009) TGF-beta promotes cell death and suppresses lactation during the second stage of mammary involution. J Cell Physiol 219(1):57–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozack AK, Cardenas A, Geldhof J, Quamruzzaman Q, Rahman M, Mostofa G, Christiani DC, Kile ML (2020a) Cord blood DNA methylation of DNMT3A mediates the association between in utero arsenic exposure and birth outcomes: results from a prospective birth cohort in Bangladesh. Environ Res 183:109134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozack AK, Colicino E, Rodosthenous R, Bloomquist TR, Baccarelli AA, Wright RO, Wright RJ, Lee AG (2020b) Associations between maternal lifetime stressors and negative events in pregnancy and breast milk-derived extracellular vesicle microRNAs in the programming of intergenerational stress mechanisms (PRISM) pregnancy cohort. Epigenetics 2020:1–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozack AK, Colicino E, Rodosthenous RS, Bloomquist TR, Baccarelli AA, Wright RO, Wright RJ, Lee AG (2022) Breast milk-derived extracellular vesicle miRNAs are associated with maternal asthma and atopy. Epigenomics 14:727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breheny P, Burchett W (2013) Visualization of regression models using visreg [Google Scholar]

- Catalanotto C, Cogoni C, Zardo G (2016) MicroRNA in control of gene expression: an overview of nuclear functions. Int J Mol Sci 17(10):1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Qiu H, Ma L, Luo J, Sun S, Kang K, Gou D, Loor JJ (2016) miR-30e-5p and miR-15a synergistically regulate fatty acid metabolism in goat mammary epithelial cells via LRP6 and YAP1. Int J Mol Sci 17(11):E1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Luo F, Liu X, Lu L, Xu H, Yang Q, Xue J, Shi L, Li J, Zhang A, Liu Q (2017) NF-kB-regulated exosomal miR-155 promotes the inflammation associated with arsenite carcinogenesis. Cancer Lett 388:21–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Chu S, Liang Y, Xu T, Sun Y, Li M, Zhang H, Wang X, Mao Y, Loor JJ, Wu Y, Yang Z (2020) miR-497 regulates fatty acid synthesis via LATS2 in bovine mammary epithelial cells. Food Funct 11(10):8625–8636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dack K, Fell M, Taylor CM, Havdahl A, Lewis SJ (2021) Mercury and prenatal growth: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(13):7140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Q, Dai X, Feng W, Huang S, Yuan Y, Xiao Y, Zhang Z, Deng N, Deng H, Zhang X, Kuang D, Li X, Zhang W, Zhang X, Guo H, Wu T (2019) Co-exposure to metals and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, microRNA expression, and early health damage in coke oven workers. Environ Int 122:369–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty BT, Romano ME, Gui J, Punshon T, Jackson BP, Karagas MR, Korrick SA (2020) Periconceptional and prenatal exposure to metal mixtures in relation to behavioral development at 3 years of age. Environ Epidemiol 4(4):e0106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak B (2010) Milk epidermal growth factor and gut protection. J Pediatr 156(2 Suppl):S31–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eades G, Yao Y, Yang M, Zhang Y, Chumsri S, Zhou Q (2011) miR-200a regulates SIRT1 expression and epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT)-like transformation in mammary epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 286(29):25992–26002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farzan SF, Howe CG, Chen Y, Gilbert-Diamond D, Cottingham KL, Jackson BP, Weinstein AR, Karagas MR (2018) Prenatal lead exposure and elevated blood pressure in children. Environ Int 121:1289–1296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feigman MJ, Moss MA, Chen C, Cyrill SL, Ciccone MF, Trousdell MC, Yang ST, Frey WD, Wilkinson JE, Dos Santos CO (2020) Pregnancy reprograms the epigenome of mammary epithelial cells and blocks the development of premalignant lesions. Nat Commun 11(1):2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge S, Wang D, Kong Q, Gao W, Sun J (2017) Function of miR-152 as a tumor suppressor in human breast cancer by targeting PIK3CA. Oncol Res 25(8):1363–1371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Guo MM, Zhang K, Zhang JH (2022) Human breast milk-derived exosomal miR-148a-3p protects against necrotizing enterocolitis by regulating p53 and Sirtuin 1. Inflammation 45(3):1254–1268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haghi M, Taha MF, Javeri A (2019) Suppressive effect of exogenous miR-16 and miR-34a on tumorigenesis of breast cancer cells. J Cell Biochem 120(8):13342–13353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harischandra DS, Ghaisas S, Rokad D, Zamanian M, Jin H, Anantharam V, Kimber M, Kanthasamy A, Kanthasamy AG (2018) Environmental neurotoxicant manganese regulates exosome-mediated extracellular miRNAs in cell culture model of Parkinson’s disease: relevance to α-synuclein misfolding in metal neurotoxicity. Neurotoxicology 64:267–277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holliday H, Baker LA, Junankar SR, Clark SJ, Swarbrick A (2018) Epigenomics of mammary gland development. Breast Cancer Res 20(1):100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe CG, Farzan SF, Garcia E, Jursa T, Iyer R, Berhane K, Chavez TA, Hodes TL, Grubbs BH, Funk WE, Smith DR, Bastain TM, Breton CV (2020a) Arsenic and birth outcomes in a predominately lower income Hispanic pregnancy cohort in Los Angeles. Environ Res 184:109294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe CG, Claus-Henn B, Farzan SF, Habre R, Eckel SP, Grubbs BH, Chavez TA, Faham D, Al-Marayati L, Lerner D, Quimby A, Twogood S, Richards MJ, Meeker JD, Bastain TM, Breton CV (2020b) Prenatal metal mixtures and fetal size in mid-pregnancy in the MADRES study. Environ Res 196:110388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe CG, Foley HB, Kennedy EM, Eckel SP, Chavez TA, Faham D, Grubbs BH, Al-Marayati L, Lerner D, Suglia S, Bastain TM, Marsit CJ, Breton CV (2021a) Extracellular vesicle Micro-RNA in early versus late pregnancy with birth outcomes in the MADRES study. Epigenetics 17:269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe CG, Foley HB, Farzan SF, Chavez TA, Johnson M, Meeker JD, Bastain TM, Marsit CJ, Breton CV (2021b) Urinary metals and maternal circulating extracellular vesicle microRNA in the MADRES pregnancy cohort. Epigenetics 17:1–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe CG, Nozadi SS, Garcia E, Oonnor TG, Starling AP, Farzan SF, Jackson BP, Madan JC, Alshawabkeh AN, Cordero JF, Bastain TM, Meeker JD, Breton CV, Karagas MR, Program collaborators for Environmental Influences on Child Health Outcomes (2022) Prenatal metal(loid) mixtures and birth weight for gestational age: a pooled analysis of three cohorts participating in the ECHO program. Environ Int 161:107102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang R, Li Y, Zhang A, Wang B, Xu Y, Xu W, Zhao Y, Luo F, Liu Q (2014) The acquisition of cancer stem cell-like properties and neoplastic transformation of human keratinocytes induced by arsenite involves epigenetic silencing of let-7c via Ras/NF-κB. Toxicol Lett 227(2):91–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh V, Pala V, Vinceti M, Berrino F, Ganzi A, Micheli A, Muti P, Vescovi L, Ferrari A, Fortini K, Sieri S, Vivoli G (2003) Toenail selenium as biomarker: reproducibility over a one-year period and factors influencing reproducibility. J Trace Elem Med Biol 17(Suppl 1):31–36 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuleshov MV, Jones MR, Rouillard AD, Fernandez NF, Duan Q, Wang Z, Koplev S, Jenkins SL, Jagodnik KM, Lachmann A, McDermott MG, Monteiro CD, Gundersen GW, Maayan A (2016) Enrichr: a comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res 44(W1):W90–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupsco A, Lee JJ, Prada D, Valvi D, Hu L, Petersen MS, Coull BA, Weihe P, Grandjean P, Baccarelli AA (2022) Marine pollutant exposures and human milk extracellular vesicle-microRNAs in a mother-infant cohort from the Faroe Islands. Environ Int 158:106986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai SW, Chen MY, Bamodu OA, Hsieh MS, Huang TY, Yeh CT, Lee WH, Cherng YG (2021) Exosomal lncRNA PVT1/VEGFA axis promotes colon cancer metastasis and stemness by downregulation of tumor suppressor miR-152–3p. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2021:9959807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiferman A, Shu J, Upadhyaya B, Cui J, Zempleni J (2019) Storage of extracellular vesicles in human milk, and microrna profiles in human milk exosomes and infant formulas. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 69(2):235–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Zou W, Wang Y, Liao Z, Li L, Zhai Y, Zhang L, Gu S, Zhao X (2020) Plasma-based microRNA signatures in early diagnosis of breast cancer. Mol Genet Genomic Med 8(5):e1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Xue J, Ling M, Sun J, Xiao T, Dai X, Sun Q, Cheng C, Xia H, Wei Y, Chen F, Liu Q (2021) MicroRNA-15b in extracellular vesicles from arsenite-treated macrophages promotes the progression of hepatocellular carcinomas by blocking the LATS1-mediated Hippo pathway. Cancer Lett 497:137–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X, Luo J, Zhang L, Zhu J (2013) MicroRNAs synergistically regulate milk fat synthesis in mammary gland epithelial cells of dairy goats. Gene Exp 16(1):1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin LT, Liu SY, Leu JD, Chang CY, Chiou SH, Lee TC, Lee YJ (2018) Arsenic trioxide-mediated suppression of miR-182-5p is associated with potent anti-oxidant effects through up-regulation of SESN2. Oncotarget 9(22):16028–16042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Wang Z, Huang H, Shou K (2021) miR-200a-3p improves neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis by regulating RIPK1. Am J Transl Res 13(11):12662–12672 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-de-Las-Hazas MC, Del-Pozo-Acebo L, Hansen MS, Gil-Zamorano J, Mantilla-Escalante DC, Gómez-Coronado D, Marín F, Garcia-Ruiz A, Rasmussen JT, Dávalos A (2022) Dietary bovine milk miRNAs transported in extracellular vesicles are partially stable during GI digestion, are bioavailable and reach target tissues but need a minimum dose to impact on gene expression. Eur J Nutr 61(2):1043–1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren SN, Madan JC, Emond JA, Morrison HG, Christensen BC, Karagas MR, Hoen AG (2018) Maternal diet during pregnancy is related with the infant stool microbiome in a delivery mode-dependent manner. Microbiome 6(1):109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren SN, Madan JC, Karagas MR, Morrison HG, Hoen AG, Christensen BC (2019) Microbial communities in human milk relate to measures of maternal weight. Front Microbiol 10:2886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S, Wei H, Wang C, Han J, Chen X, Li Y (2021) MiR-26b-5p inhibits cell proliferation and EMT by targeting MYCBP in triple-negative breast cancer. Cell Mol Biol Lett 26(1):52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon R, Debnath C, Lai A, Guanzon D, Bhatnagar S, Kshetrapal PK, Sheller-Miller S, Salomon C, Garbhini Study Team (2019) Circulating exosomal miRNA profile during term and preterm birth pregnancies: a longitudinal study. Endocrinology 160(2):249–275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirza AH, Kaur S, Nielsen LB, Størling J, Yarani R, Roursgaard M, Mathiesen ER, Damm P, Svare J, Mortensen HB, Pociot F (2019) Breast milk-derived extracellular vesicles enriched in exosomes from mothers with type 1 diabetes contain aberrant levels of microRNAs. Front Immunol 10:2543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi-Yeganeh S, Paryan M, Arefian E, Vasei M, Ghanbarian H, Mahdian R, Karimipoor M, Soleimani M (2016) MicroRNA-340 inhibits the migration, invasion, and metastasis of breast cancer cells by targeting Wnt pathway. Tumour Biol 37(7):8993–9000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori MA, Ludwig RG, Garcia-Martin R, Brandão BB, Kahn CR (2019) Extracellular miRNAs: from biomarkers to mediators of physiology and disease. Cell Metab 30(4):656–673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nata T, Fujiya M, Ueno N, Moriichi K, Konishi H, Tanabe H, Ohtake T, Ikuta K, Kohgo Y (2013) MicroRNA-146b improves intestinal injury in mouse colitis by activating nuclear factor-κB and improving epithelial barrier function. J Gene Med 15(6–7):249–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngalame NNO, Luz AL, Makia N, Tokar EJ (2018) Arsenic alters exosome quantity and cargo to mediate stem cell recruitment into a cancer stem cell-like phenotype. Toxicol Sci 165(1):40–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakes SR, Hilton HN, Ormandy CJ (2006) Key stages in mammary gland development - The alveolar switch: coordinating the proliferative cues and cell fate decisions that drive the formation of lobuloalveoli from ductal epithelium. Breast Cancer Res 8(2):207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Vázquez MS, Ochoa-Martínez ÁC, RuÍz-Vera T, Araiza-Gamboa Y, Pérez-Maldonado IN (2017) Evaluation of epigenetic alterations (mir-126 and mir-155 expression levels) in Mexican children exposed to inorganic arsenic via drinking water. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 24(36):28036–28045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullella K, Kotsopoulos J (2020) Arsenic exposure and breast cancer risk: a re-evaluation of the literature. Nutrients 12(11):E3305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punshon T, Li Z, Marsit CJ, Jackson BP, Baker ER, Karagas MR (2016) Placental metal concentrations in relation to maternal and infant toenails in a U.S. cohort. Environ Sci Technol 50(3):1587–1594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Y, Liu H, Lv X, Liu Y, Wang X, Zhang M, Zhang X, Li Y, Lou Q, Li S, Li H (2017) MicroRNA-16-5p overexpression suppresses proliferation and invasion as well as triggers apoptosis by targeting VEGFA expression in breast carcinoma. Oncotarget 8(42):72400–72410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R: The R Stats Package. [cited 2022 Jun 2]. https://stat.ethz.ch/R-manual/R-devel/library/stats/html/00Index.html

- Rager JE, Bailey KA, Smeester L, Miller SK, Parker JS, Laine JE, Drobná Z, Currier J, Douillet C, Olshan AF, Rubio-Andrade M, Stýblo M, García-Vargas G, Fry RC (2014) Prenatal arsenic exposure and the epigenome: altered microRNAs associated with innate and adaptive immune signaling in newborn cord blood. Environ Mol Mutagen 55(3):196–208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman ML, Liang L, Valeri L, Su L, Zhu Z, Gao S, Mostofa G, Qamruzzaman Q, Hauser R, Baccarelli A, Christiani DC (2018) Regulation of birthweight by placenta-derived miRNAs: evidence from an arsenic-exposed birth cohort in Bangladesh. Epigenetics 13(6):573–590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramalho-Carvalho J, Gonçalves CS, Graça I, Bidarra D, Pereira-Silva E, Salta S, Godinho MI, Gomez A, Esteller M, Costa BM, Henrique R, Jerónimo C (2018) A multiplatform approach identifies miR-152-3p as a common epigenetically regulated onco-suppressor in prostate cancer targeting TMEM97. Clin Epigenet 10:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodosthenous RS, Burris HH, Sanders AP, Just AC, Dereix AE, Svensson K, Solano M, Téllez-Rojo MM, Wright RO, Baccarelli AA (2017) Second trimester extracellular microRNAs in maternal blood and fetal growth: an exploratory study. Epigenetics 12(9):804–810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth MJ, Moorehead RA (2021) The miR-200 family in normal mammary gland development. BMC Dev Biol 21(1):12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruíz-Vera T, Ochoa-Martínez ÁC, Zarazúa S, Carrizales-Yáñez L, Pérez-Maldonado IN (2019) Circulating miRNA-126, -145 and -155 levels in Mexican women exposed to inorganic arsenic via drinking water. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 67:79–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomon C, Guanzon D, Scholz-Romero K, Longo S, Correa P, Illanes SE, Rice GE (2017) Placental exosomes as early biomarker of preeclampsia: potential role of exosomal MicroRNAs across gestation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 102(9):3182–3194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders AP, Miller SK, Nguyen V, Kotch JB, Fry RC (2014) Toxic metal levels in children residing in a smelting craft village in Vietnam: a pilot biomonitoring study. BMC Public Health 14(1):114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah KB, Chernausek SD, Garman LD, Pezant NP, Plows JF, Kharoud HK, Demerath EW, Fields DA (2021) Human milk exosomal MicroRNA: associations with maternal overweight/obesity and infant body composition at 1 month of life. Nutrients 13(4):1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah KB, Fields DA, Pezant NP, Kharoud HK, Gulati S, Jacobs K, Gale CA, Kharbanda EO, Nagel EM, Demerath EW, Tryggestad JB (2022) Gestational diabetes mellitus is associated with altered abundance of exosomal MicroRNAs in human milk. Clin Ther 44(2):172–185.e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Cao T, Huang H, Lian C, Yang Y, Wang Z, Ma J, Xia J (2017) Arsenic trioxide inhibits cell growth and motility via up-regulation of let-7a in breast cancer cells. Cell Cycle 16(24):2396–2403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Si L, Jiang F, Li Y, Ye X, Mu J, Wang X, Ning S, Hu C, Li Z (2015) Induction of the mesenchymal to epithelial transition by demethylation- activated microRNA-200c is involved in the anti-migration/invasion effects of arsenic trioxide on human breast cancer cells. Mol Carcinog 54(9):859–869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Signes-Pastor AJ, Bouchard MF, Baker E, Jackson BP, Karagas MR (2019a) Toenail manganese as biomarker of drinking water exposure: a reliability study from a US pregnancy cohort. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 29(5):648–654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Signes-Pastor AJ, Doherty BT, Romano ME, Gleason KM, Gui J, Baker E, Karagas MR (2019b) Prenatal exposure to metal mixture and sex-specific birth outcomes in the New Hampshire Birth Cohort Study. Environ Epidemiol 3(5):e068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Signes-Pastor AJ, Gutiérrez-González E, García-Villarino M, Rodríguez-Cabrera FD, López-Moreno JJ, Varea-Jiménez E, Pastor-Barriuso R, Pollán M, Navas-Acien A, Pérez-Gómez B, Karagas MR (2021) Toenails as a biomarker of exposure to arsenic: a review. Environ Res 195:110286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun B, Xue J, Li J, Luo F, Chen X, Liu Y, Wang Q, Qi C, Zou Z, Zhang A, Liu Q (2017) Circulating miRNAs and their target genes associated with arsenism caused by coal-burning. Toxicol Res (camb) 6(2):162–172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thamotharan S, Ghosh S, James-Allan L, Lei MYY, Janzen C, Devaskar SU (2022) Circulating extracellular vesicles exhibit a differential miRNA profile in gestational diabetes mellitus pregnancies. PLoS ONE 17(5):e0267564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Théry C, Witwer KW, Aikawa E, Alcaraz MJ, Anderson JD, Andriantsitohaina R, Antoniou A, Arab T, Archer F, Atkin-Smith GK, Ayre DC, Bach JM, Bachurski D, Baharvand H, Balaj L, Baldacchino S, Bauer NN, Baxter AA, Bebawy M, Beckham C, Zavec AB, Benmoussa A, Berardi AC, Bergese P, Bielska E, Blenkiron C, Bobis-Wozowicz S, Boilard E, Boireau W, Bongiovanni A, Borràs FE, Bosch S, Boulanger CM, Breakefield X, Breglio AM, Brennan MÁ, Brigstock DR, Brisson A, Broekman ML, Bromberg JF, Bryl-Górecka P, Buch S, Buck AH, Burger D, Busatto S, Buschmann D, Bussolati B, Buzás EI, Byrd JB, Camussi G, Carter DR, Caruso S, Chamley LW, Chang YT, Chen C, Chen S, Cheng L, Chin AR, Clayton A, Clerici SP, Cocks A, Cocucci E, Coffey RJ, Cordeiro-da-Silva A, Couch Y, Coumans FA, Coyle B, Crescitelli R, Criado MF, DSouza-Schorey C, Das S, Chaudhuri AD, Candia P de, Wever OD, Portillo HA del, Demaret T, Deville S, Devitt A, Dhondt B, Vizio DD, Dieterich LC, Dolo V, Rubio APD, Dominici M, Dourado MR, Driedonks TA, Duarte FV, Duncan HM, Eichenberger RM, Ekström K, Andaloussi SE, Elie-Caille C, Erdbrügger U, Falcón-Pérez JM, Fatima F, Fish JE, Flores-Bellver M, Försönits A, Frelet-Barrand A, Fricke F, Fuhrmann G, Gabrielsson S, Gámez-Valero A, Gardiner C, Gärtner K, Gaudin R, Gho YS, Giebel B, Gilbert C, Gimona M, Giusti I, Goberdhan DC, Görgens A, Gorski SM, Greening DW, Gross JC, Gualerzi A, Gupta GN, Gustafson D, Handberg A, Haraszti RA, Harrison P, Hegyesi H, Hendrix A, Hill AF, Hochberg FH, Hoffmann KF, Holder B, Holthofer H, Hosseinkhani B, Hu G, Huang Y, Huber V, Hunt S, Ibrahim AGE, Ikezu T, Inal JM, Isin M, Ivanova A, Jackson HK, Jacobsen S, Jay SM, Jayachandran M, Jenster G, Jiang L, Johnson SM, Jones JC, Jong A, Jovanovic-Talisman T, Jung S, Kalluri R, Kano S, Kaur S, Kawamura Y, Keller ET, Khamari D, Khomyakova E, Khvorova A, Kierulf P, Kim KP, Kislinger T, Klingeborn M, Kornek M, Kosanović MM, Kovács ÁF, Krämer-Albers EM, Krasemann S, Krause M, Kurochkin IV, Kusuma GD, Kuypers S, Laitinen S, Langevin SM, Languino LR, Lannigan J, Lässer C, Laurent LC, Lavieu G, Lázaro-Ibáñez E, Lay SL, Lee MS, Lee YXF, Lemos DS, Lenassi M, Leszczynska A, Li IT, Liao K, Libregts SF, Ligeti E, Lim R, Lim SK, Linē A, Linnemannstöns K, Llorente A, Lombard CA, Lorenowicz MJ, Lörincz ÁM, Lötvall J, Lovett J, Lowry MC, Loyer X, Lu Q, Lukomska B, Lunavat TR, Maas SL, Malhi H, Marcilla A, Mariani J, Mariscal J, Martens-Uzunova ES, Martin-Jaular L, Martinez MC, Martins VR, Mathieu M, Mathivanan S, Maugeri M, McGinnis LK, McVey MJ, Meehan KL, Mertens I, Minciacchi VR, Möller A, Jørgensen MM, Morales-Kastresana A, Morhayim J, Mullier F, Muraca M, Musante L, Mussack V, Muth DC, Myburgh KH, Najrana T, Nawaz M, Nazarenko I, Nejsum P, Neri C, Neri T, Nieuwland R, Nimrichter L, Nolan JP, Hoen ENN, Hooten NN, Oriscoll L, Orady T, O’Loghlen A, Ochiya T, Olivier M, Ortiz A, Ortiz LA, Osteikoetxea X, Østergaard O, Ostrowski M, Park J, Pegtel DM, Peinado H, Perut F, Pfaffl MW, Phinney DG, Pieters BC, Pink RC, Pisetsky DS, Strandmann EP, Polakovicova I, Poon IK, Powell BH, Prada I, Pulliam L, Quesenberry P, Radeghieri A, Raffai RL, Raimondo S, Rak J, Ramirez MI, Raposo G, Rayyan MS, Regev-Rudzki N, Ricklefs FL, Robbins PD, Roberts DD, Rodrigues SC, Rohde E, Rome S, Rouschop KM, Rughetti A, Russell AE, Saá P, Sahoo S, Salas-Huenuleo E, Sánchez C, Saugstad JA, Saul MJ, Schiffelers RM, Schneider R, Schøyen TH, Scott A, Shahaj E, Sharma S, Shatnyeva O, Shekari F, Shelke GV, Shetty AK, Shiba K, Siljander PRM, Silva AM, Skowronek A, Soares RP, Sódar BW, Soekmadji C, Sotillo J, Stahl PD, Stoorvogel W, Stott SL, Strasser EF, Swift S, Tahara H, Tewari M, Timms K, Tiwari S, Tixeira R, Tkach M, Toh WS, Tomasini R, Torrecilhas AC, Tosar JP, Toxavidis V, Urbanelli L, Vader P, Balkom BW van, Grein SG van der, Deun JV, Herwijnen MJ van, Keuren-Jensen KV, Niel G van, Royen ME van, Wijnen AJ van, Vasconcelos MH, Veit TD, Vella LJ, Velot É, Verweij FJ, Vestad B, Viñas JL, Visnovitz T, Vukman KV, Wahlgren J, Watson DC, Wauben MH, Weaver A, Webber JP, Weber V, Wehman AM, Weiss DJ, Welsh JA, Wendt S, Wheelock AM, Wiener Z, Witte L, Wolfram J, Xagorari A, Xander P, Xu J, Yan X, Yáñez-Mó M, Yin H, Yuana Y, Zappulli V, Zarubova J, Žėkas V, Zhang JY, Zhao Z, Zheng L, Zheutlin AR, Zickler AM, Zimmermann P, Zivkovic AM, Zocco D, Zuba-Surma EK (2018) Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): a position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J Extracell Vesicles 7(1):1535750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokar T, Pastrello C, Rossos AEM, Abovsky M, Hauschild AC, Tsay M, Lu R, Jurisica I (2018) MirDIP 41-integrative database of human microRNA target predictions. Nucleic Acids Res 46(D1):D360–D370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang HF, Xue VW, Koh SP, Chiu YM, Ng LPW, Wong SCC (2017) NanoString, a novel digital color-coded barcode technology: current and future applications in molecular diagnostics. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 17(1):95–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahter M, Skröder H, Rahman SM, Levi M, Derakhshani Hamadani J, Kippler M (2020) Prenatal and childhood arsenic exposure through drinking water and food and cognitive abilities at 10 years of age: a prospective cohort study. Environ Int 139:105723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Herwijnen MJC, Driedonks TAP, Snoek BL, Kroon AMT, Kleinjan M, Jorritsma R, Pieterse CMJ, Hoen ENMN, Wauben MHM (2018) Abundantly present miRNAs in milk-derived extracellular vesicles are conserved between mammals. Front Nutr 5:81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waggott D, Chu K, Yin S, Wouters BG, Liu FF, Boutros PC (2012) NanoStringNorm: an extensible R package for the pre-processing of NanoString mRNA and miRNA data. Bioinformatics 28(11):1546–1548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Wang L, Yin C, An B, Hao Y, Wei T, Li L, Song G (2015) Arsenic trioxide inhibits breast cancer cell growth via micro-RNA-328/hERG pathway in MCF-7 cells. Mol Med Rep 12(1):1233–1238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Ge X, Zheng J, Li D, Liu X, Wang L, Jiang C, Shi Z, Qin L, Liu J, Yang H, Liu LZ, He J, Zhen L, Jiang BH (2016) Role and mechanism of miR-222 in arsenic-transformed cells for inducing tumor growth. Oncotarget 7(14):17805–17814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zhang P, Chen X, Wu W, Feng Y, Yang H, Li M, Xie B, Guo P, Warren JL, Shi X, Wang S, Zhang Y (2019) Multiple metal concentrations and gestational diabetes mellitus in Taiyuan, China. Chemosphere 237:124412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Fu X, Zhang J, Xu C, Hu Q, Lin W (2020a) Association between blood lead level during pregnancy and birth weight: a meta-analysis. Am J Ind Med 63(12):1085–1094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Gao D, Zhang G, Zhang X, Li Q, Gao Q, Chen R, Xu S, Huang L, Zhang Y, Lin L, Zhong C, Chen X, Sun G, Song Y, Yang X, Hao L, Yang H, Yang L, Yang N (2020b) Exposure to multiple metals in early pregnancy and gestational diabetes mellitus: a prospective cohort study. Environ Int 135:105370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Xiao T, Li J, Wang D, Sun J, Cheng C, Ma H, Xue J, Li Y, Zhang A, Liu Q (2021) miR-21 in EVs from pulmonary epithelial cells promotes myofibroblast differentiation via glycolysis in arsenic-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Environ Pollut 286:117259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Zang X, Liu Y, Liang Y, Cai G, Wu Z, Li Z (2022) Dynamic miRNA landscape links mammary gland development to the regulation of milk protein expression in mice. Animals (basel) 12(6):727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willett WC, Sampson L, Stampfer MJ, Rosner B, Bain C, Witschi J, Hennekens CH, Speizer FE (1985) Reproducibility and validity of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. Am J Epidemiol 122(1):51–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood SN (2017) Generalized additive models: an introduction with R, 2nd edn. CRC Press/Taylor & Francis Group, Boca Raton [Google Scholar]

- Wu D, Kittana H, Shu J, Kachman SD, Cui J, Ramer-Tait AE, Zempleni J (2019) Dietary depletion of milk exosomes and their Micro-RNA cargos elicits a depletion of miR-200a-3p and elevated intestinal inflammation and chemokine (C-X-C Motif) ligand 9 expression in Mdr1a−/− Mice. Curr Dev Nutr 3(12):122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi Y, Jiang X, Li R, Chen M, Song W, Li X (2016) The levels of human milk microRNAs and their association with maternal weight characteristics. Eur J Clin Nutr 70(4):445–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Luo F, Liu Y, Shi L, Lu X, Xu W, Liu Q (2015) Exosomal miR-21 derived from arsenite-transformed human bronchial epithelial cells promotes cell proliferation associated with arsenite carcinogenesis. Arch Toxicol 89(7):1071–1082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yim G, Wang Y, Howe CG, Romano ME (2022) Exposure to metal mixtures in association with cardiovascular risk factors and outcomes: a scoping review. Toxics 10(3):116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamanillo R, Sánchez J, Serra F, Palou A (2019) Breast milk supply of MicroRNA associated with leptin and adiponectin is affected by maternal overweight/obesity and influences infancy BMI. Nutrients 11(11):2589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Zhao Y, Wang Y, Wu H, Fang X, Chen H (2014) Deep RNA sequencing reveals that microRNAs play a key role in lactation in rats. J Nutr 144(8):1142–1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Ma C, Pang H, Zeng F, Cheng L, Fang B, Ma J, Shi Y, Hong H, Chen J, Wang Z, Xia J (2016) Arsenic trioxide suppresses cell growth and migration via inhibition of miR-27a in breast cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 469(1):55–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Q, Cui Y, Wu H, Niu Q, Lu X, Wang L, Huang F (2019) Association of maternal arsenic exposure with birth size: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 69:129–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The miRNA data generated for this study will be made available in GEO upon publication of this manuscript.