Abstract

Purpose of review

To summarize the current literature on allyship, providing a historical perspective, concept analysis, and practical steps to advance equity, diversity, and inclusion. This review also provides evidence-based tools to foster allyship and identifies potential pitfalls.

Recent findings

Allies in healthcare advocate for inclusive and equitable practices that benefit patients, coworkers, and learners. Allyship requires working in solidarity with individuals from underrepresented or historically marginalized groups to promote a sense of belonging and opportunity. New technologies present possibilities and perils in paving the pathway to diversity.

Summary

Unlocking the power of allyship requires that allies confront unconscious biases, engage in self-reflection, and act as effective partners. Using an allyship toolbox, allies can foster psychological safety in personal and professional spaces while avoiding missteps. Allyship incorporates goals, metrics, and transparent data reporting to promote accountability and to sustain improvements. Implementing these allyship strategies in solidarity holds promise for increasing diversity and inclusion in the specialty.

Keywords: Allyship; Diversity equity, and inclusion; Healthcare disparities; Artificial intelligence; Psychological safety; Mentorship, coaching, and sponsorship

Introduction

Allyship involves fighting injustice and promoting equity through acts of advocacy [1]. The National Institutes of Health describes allyship as, “When a person of privilege works in solidarity and partnership with a marginalized group of people to help take down the systems that challenge that group’s basic rights, equal access, and ability to thrive in our society” [2]. Medical professionals of majority groups can serve as allies for patients, colleagues, and communities at the margins. As the profession begins to widen its lane to understand social factors that influence patient care, it also needs to look inward and identify opportunities for allyship. Allyship can give a voice those who might not have one and can lift those whose contributions might otherwise go unnoticed. It involves accountability and measuring outcomes of efforts towards diversity. This article explores the current state in otolaryngology, the history and rationale for allyship, and offers practical, evidence-based tools to develop allyship skills. Allyship most often emphasizes underrepresented racial and ethnic minorities, but it applies to any disadvantaged group involving gender identity, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, and others.

Limited Diversity in Otolaryngology: A Need for Allyship

A diverse health care workforce is necessary to promote equitable health care delivery amid the myriad challenges of limited access to care, rising health inequities, and escalating costs. Specialties with more minority physicians, such as primary care, study and publish on heath disparities at greater rates, thereby advancing the science. Individuals who identify as Black or African American, American Indian and Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander, Hispanic, or two or more races.make up 40.9% of the US population and are expected to comprise 59.5% of the population by 2060 [3]. Racially or ethnically concordant patient-physician relationships are associated with more effective communication, increased patient satisfaction, better adherence to treatment, and improved health care outcomes, all of which can lessen disparities [4•, 5•, 6–10]. The lack of diversity in otolaryngology can be traced to underrepresentation in medical school and pervasive inequities present at earlier stages of education [11–16]. These challenges are accentuated in otolaryngology, both in match rates and at successive career stages [17•, 18]. In 2019, only 12.1% of practicing physicians identified as members of groups underrepresented in medicine (URiM), and otolaryngology has one of the lowest rates of URiM residents and faculty among specialties [12, 17•, 18, 19].

Despite ongoing efforts to improve diversity in the medical profession, there has been little progress in improving diversity in the past half century. The American Association of Medical Colleges recently reported that only 153 women identified as URiM versus 1063 White and only 436 men identified as URiM compared to 5323 White [19]. Applicants to otolaryngology residency programs were 6.1% Black and 9.4% Latinx, with successful match rates of only 2.3% and 6.2%, respectively [17•]. Representation further diminishes as one moves up the career ladder [20]; very few URiM individuals serve as academic leaders [8], and these data are a clarion call to develop robust pathways to promote success of URiM individuals in matriculation and across the career continuum. We must also accurately represent and publish progress in growth of URiM in otolaryngology; a recent correspondence revealed the challenges in recording, tracking, and transparently reporting progress on these fronts [21].

The chasm between intent and action can be partially explained by the distance between decision makers—whether in hospitals, academic medical center, or other spheres of influence—and those with perspective of lived experience and practical insight into what is needed to achieve sustainable change in diversity efforts. Across healthcare settings, much of the work to promote diversity is shouldered by URiM faculty, who are left with less time and energy to focus on their research other aspects of career advancement. This concept is known as the “minority tax.” URiM faculty are often recruited to serve in many roles, including those related to DEI initiatives; however, these roles often are uncompensated and not tied to metrics of academic promotion or professional development. Growing recognition of this problem has led to calls for innovative strategies to redistribute engagement in diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives [22••], and allyship is necessary for such approaches to be successful. The “minority tax” may exacerbate the very problems DEI efforts purport to address, since it compels URiM faculty to direct their time and energy away from other professional pursuits.

A similar “tax” applies to women, LGBTQ+ individuals, and individuals with disabilities, all of whom may be over-extended but reluctant to decline due to a sense of obligation to speak up; colleagues in majority groups seldom feel these burdens. The “tax” is compounded for individuals with intersectional identities, which can drive disparities in career development and satisfaction at work [21, 22••, 23–30]. Accordingly, the responsibility for increasing diversity in otolaryngology falls to all within the field, and especially those in positions of influence who can advocate for others [31, 32, 33•, 34]. Most URiM otolaryngology leaders attribute success to grit and perseverance, and positive differentiators in the pathway are mentorship, coaching, sponsorship, and allyship [1]. The same applies to members of any group with less influence than its majority counterparts. Definitions and principles of allyship are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Allyship: definitions and principles

| Term/concept | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Ally | Individual outside a specific identify group who works in solidarity with that group to understand and counter systemic or local biases against them. This term is not self-imposed but earned from the individual or group being supported | Non-URiM chairperson who actively seeks to recruit URiM faculty, foster their career development, and change institutional policies that hinder these goals |

| Allyship | Behaviors and actions by an ally in support of the individual or group of interest | Non-URiM chairperson proactively offers additional 10% compensated FTE for URiM faculty member’s EDI work at departmental level |

| Systemic (or structural) bias | Inherent tendency of policies, practice, protocols, or other systemic factors to create and maintain disparities or injustice | University tenure and clinician-educator lines differ in rates of women faculty, which then creates the false belief that women are less qualified for tenure line, which perpetuates hiring differences in the two lines |

| Performative allyship | Allyship based on words without action, often self-serving to create a positive image of the self-ascribed “ally” | Non-URiM chairperson publishing statement about LGBTQ+ Pride while failing to support LGBTQ+ faculty recruitment or career development |

| Mentor | Individual who provides advice and guidance to those earlier in their career path, based on their own experiences | LGBTQ+ senior faculty member has regular meetings with LGBTQ+ junior faculty to discuss career plans |

| Coach | Individual who supports others by asking questions and eliciting their goals, insights, and concerns such that those individuals can determine their own answers are develop skills | Physician leader of a medical group meets regularly with junior colleague to help them explore their career development plans and work-life balance |

| Sponsor | Individual who provides opportunities and connections to others; leverages their own power or influence and social capital through these actions | Male AAO-HNS/F committee chair advocates for female committee member as his successor |

FTE Full-time equivalent, URiM, Underrepresented in medicine, LGBTQ+ Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and others, EDI Equity, diversity, and inclusion, AAO-HNS/F American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery/Foundation

History of Allyship in the USA

Allyship has a longer history than many realize. Allies have championed social justice and worked alongside leaders of marginalized groups to mitigate inequalities in the USA for the past two centuries [35]. However, the role of allyship in healthcare is just beginning to be appreciated [36, 37, 38•, 39, 40••]. In America, allies were prominent figures in the Abolitionist Movement of the 1830’s, calling out slavery as an abomination and launching organized efforts to eradicate slave ownership. Efforts of White abolitionists were in solidarity with Black men and women, some of whom had escaped from bondage. William Lloyd Garrison, who founded the Abolitionist Newspaper, The liberator, led the American Anti-Slavery Society and partnered with Frederick Douglass, who escaped slavery himself. John Brown staged armed rebellions; the most notorious being the raid on Harper’s Ferry, Virginia [35].

In this era, clandestine efforts to counteract slavery required solidarity between allies and oppressed individuals. The Underground Railroad—a network of Black and White individuals who worked together to allow enslaved persons to escape the South—illustrates the collaborations still needed today. Quaker abolitionists like Isaac T. Hopper built networks of routes and shelters for escapees. Many formerly enslaved persons shared in these courageous acts. For example, Harriet Tubman, a famed conductor for the underground railroad, led groups of escapees all the way to Canada. Other female abolitionists such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott later became leaders in the women’s rights movement, reflecting that allies can also engage in struggles for justice among their own identity group [35].

After the civil war era, the Jim Crow laws were introduced in the southern USA. These laws mandated racial segregation in public facilities and were later reinforced by the Plessy vs. Ferguson case, in which the Supreme Court introduced the legal doctrine of “separate but equal.” A prominent ally during this era was Julietta Hampton Morgan, who spoke out against discrimination against Black people and wrote letters in her local newspaper. Morgan was fired from her job, received letters and phone calls with threats, and had a cross burned in front of her yard before she eventually took her own life. Although modern day allies seldom face such societal pressure and disapproval, contemporary allyship can also be arduous; Morgan’s story captures the resistance that allies not uncommonly encounter [35].

Even when rulings of the courts support equity, justice is not always served. In Worchester vs. Georgia a White ally of the Cherokee bought their case to the Supreme Court to establish sovereignty and to fight their forced removal from Georgia. The court ruling was in favor of Worchester and the Cherokee, creating the foundational doctrine of tribal sovereignty in the USA; but the decision was not enforced. The USA forcibly removed more than 15,000 Cherokees from 1838 to 1839. During this time an estimated 4000 individuals succumbed to starvation or disease during detention or forced migration across nine states, constituting the “Trail of Tears” [41]. Imperialism and unjust policies have thus left a legacy of structural inequities persisting to the present day, many of which carry over to healthcare. Allyship can help to overcome inequities rooted in the past and meet needs of present day.

Bringing Groups Together to be Stronger Allies for Each Other

Other marginalized groups, many of whom have been allies for Black Americans, similarly face an array of challenges and have a pressing need for allyship. Among these groups are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or sometimes questioning, and others (LGBTQIA+) individuals who confront stigma and complex social and legal barriers; Asian American and Pacific Islander individuals who contend with xenophobia and racism; South and Southeast Asian individuals who are subject to caste-based discrimination; immigrants must face anti-immigrant bias, racism, or mistreatment; and individuals with disability who must struggle with lack of accommodations and equitable access amid a culture of ableism. There is an opportunity to bring all marginalized groups together to be stronger allies for each other.

LGBTQIA+ individuals face a multitude of challenges in their personal and professional lives because of social stigma and discrimination. Members of this group repeatedly encounter prejudice, exclusion, and violence based on their sexual orientation or gender identity. Formidable legal hurdles also exist in the USA and abroad, with many states lacking comprehensive laws that protect LGBTQIA+ rights or that criminalize discriminatory acts. These structural inequalities can impede access to basic healthcare, education, employment, and housing. The challenges faced with coverage for gender-affirming surgery are an example of barriers to these needs. These challenges reduce opportunities for personal and professional growth. This population has elevated rates of anxiety, depression and suicide due to the stress and isolation arising from stress and societal rejection. The journey of self-acceptance and coming out is also fraught with emotional difficulty, as individuals may fear rejection from family, friends, or their communities. The fight for equality and acceptance remains an ongoing battle, and allyship around advocacy efforts are crucial in addressing these barriers to creating a more inclusive society.

Asian American Pacific Islanders (AAPI) face a distinct range of challenges arising from xenophobia that have escalated in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Stereotyping and racial profiling are pervasive issues, where AAPI individuals are often subjected to assumptions and biases based on their appearance or cultural background. This can manifest in various forms, including microaggressions, hate crimes, and exclusionary practices. The model minority myth, which portrays AAPI communities as universally successful and overachieving, further marginalizes those who do not conform to these expectations. Additionally, language barriers and cultural differences can create obstacles in accessing healthcare, education, employment, and other essential services. In recent times, the AAPI community has seen a surge in hate crimes and violence, fueled by xenophobia and scapegoating during public health crises. It is crucial to address these challenges by promoting cultural understanding, combating stereotypes, and advocating for inclusive policies that protect the rights and well-being of AAPI individuals.

Immigrants and their descendants from South and Southeast Asia have at times been described as “model minorities”: often highly educated, often working well-paying jobs, often English-speaking. Some of these populations are disproportionately represented in the medical profession. However, both immigrants and subsequent generations in these groups frequently experience racism from colleagues and patients, similar to other groups of color. Furthermore, in-group biases based on historic caste, linguistic or geographic background, or socioeconomic background are pervasive in South Asian communities. Allyship is essential in countering the effects of these experiences, particularly when these groups might otherwise pass by without attention as a result of their “model minority” status. For the same reason, those with lower English proficiency or lower socioeconomic status may be particularly vulnerable and may benefit all the more from effective allyship.

All immigrants face a risk of anti-immigrant discrimination and racism. Similar to previously noted groups, immigrants are susceptible to employment discrimination, denial of essential services, or verbal or physical abuse. Hostility directed against immigrants is often rooted in resentment related to their perceived status as outsiders, and despite important contributions are often regarded as a threat to the economy or cultural mores. These views can impede integration, limit social mobility, and increasing social isolation. There risks are often magnified for individuals with intersectional identities relating to racial and ethnic groups, which can compound discrimination and bias faces by immigrants. Addressing these challenges requires a multipronged approach that incorporates legal protections, allyship, and political efforts to advocate for shared opportunity.

Last Individuals with disabilities encounter challenges related to access and opportunity to engage fully in experience. For example, for individuals with physical limitations, many public spaces, buildings, transportation systems, and even digital platforms lack the necessary accommodations to ensure equal access for individuals with disabilities. In otolaryngology, the challenges related to hearing, speech, and communication are prominent concerns. Limited employment prospects and create economic hardship for individuals with disabilities due to barriers to securing and maintaining jobs. Recurring themes also involve access to healthcare, assistive technologies, and other basic needs.

Allyship in Otolaryngology

Within Otolaryngology and healthcare, the history of allyship is less well documented, and perhaps most of it is yet to be written. But evidence of allyship dates to the early days of the field, including individuals like Dr. John Kearny Rogers, who took Dr. David Kearny McDonogh, America’s first African American Ophthalmology and Otolaryngology specialist, as his protégé. Many subsequent allies have followed, with their contributions evident in residency training programs and national organizations. These allies include residency program directors, department chairs, and leaders within our national societies, who have advocated for diversity or been quiet movers behind the scenes who lobbied for progressive policies in departments, academic institutions, or national organizations. Within otolaryngology, The Harry Barnes Medical provides pathways and opens doors for historically minoritized physicians and learners. Allies should note that it is open to individuals of all backgrounds who embrace its mission.

The American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery/Foundation (AAO-HNS/F) has provided allyship for women, URiM, and the LGBTQ+ communities. Women in Otolaryngology (WIO) began as a small committee, and with support from predominantly male leadership, became a robust section. Today, WIO has a well-funded endowment and ensures women have a strong voice in the organization and can influence direction of the specialty. WIO’s “He for She Award,” recognizes men who are allies for women in otolaryngology. The Diversity Committee of the AAO-HNS, established as an ad hoc forum to address diversity, became a committee of diverse members and allies with a strong endowment. The committee promotes diverse engagement in panels and presentations, champions LGBTQ+ education at the Annual meeting, offers scholarships and programming to attract URiM student to otolaryngology, and creates opportunities for diverse individuals to meet informally. Both entities have non-voting seats on the organization’s Board and are highlighted in AAO-HNS/F communications. Other societies within otolaryngology have followed suit, affording opportunities for allyship through the Society for University Otolaryngologists, the Triological Society, and all subspecialty societies.

Authentic versus Performative Allyship

Authentic allyship is an active, consistent, and arduous practice in which a person from a privileged or empowered group seeks to understand, to support, and to advocate for marginalized groups [42]. For example, the allyship of a White male department chair who coaches, mentors, or sponsors a Black female aspiring department chair is instrumental in advancing the specialty. The descriptor of ally is not self-ascribed but rather attributed to those who work to remove barriers and dismantle systems that impede equal access or ability to succeed. Allyship often requires going against the grain [42], and being an ally implies a willingness to put one’s own circumstances of privilege at risk. Furthermore, it is not fleeting; allyship involves a commitment to stand up for fairness for the long haul. Allyship involves taking deliberate steps to address the challenges faced by any underrepresented or marginalized group. Allyship is developed over time and requires solidarity around the struggle for equitable treatment.

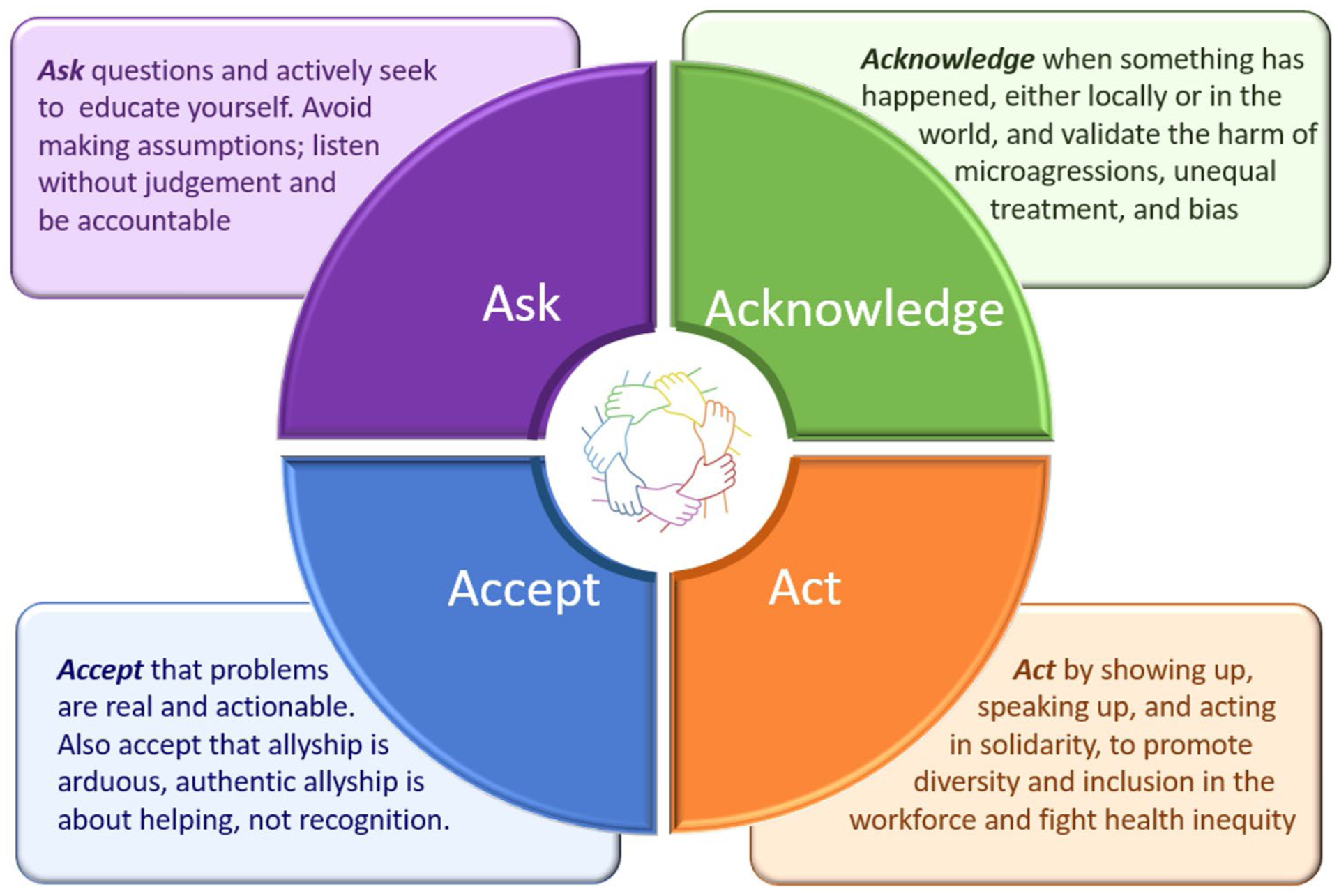

There are many ways that someone can act as an ally, and though allyship often begins with passive activities focused on learning, it must also include active approaches to effecting change (Fig. 1). An ally might begin by learning about historical factors that created barriers to advancement for individuals from historically marginalized groups or by familiarizing oneself with the terminology used in efforts to improve diversity and inclusion. Attending forums and educational symposia related to diversity are useful entry points, but a commitment to allyship is a lifelong journey, wherein one works to understand unconscious biases, to learn from the lived experiences of others, and to advocate for progress despite challenging or uncomfortable situations. One of the authors shared how resident physicians at his institution were arranging a demonstration against police brutality, but the hospital administration shut the initiative down. A majority faculty member approached institutional leadership to share the vision and impact of this work, which helped to create a pathway where none had existed.

Fig. 1.

Authentic Allyship. Many interrelated concepts are embedded in the principles of allyship. Some of the core concepts relating to acting, asking, acknowledging, and accepting are depicted

Allyship can thus involve affording a voice to someone who might have difficulty speaking up, supporting DEI initiatives, or acknowledging daily lived experiences. Allies take purposeful, visible, and consistent steps, and these efforts can take any number of forms. Acts of allyship can occur in the moment, such as a bystander intervention in response to a micro-aggression, or they can involve longitudinal efforts, like working to change entrenched policies and practices. Advocacy for holistic assessment of residency applicants is an example of an intervention requiring sustained effort over time. Allies must also be attuned to their own contribution to inequities and work toward fostering a safe and inclusive work environment. Active allyship includes participating in diversity initiatives, inviting voices and opinions of all individuals, and actively seeking out opportunities to mentor, coach, or sponsor individuals from historically marginalized groups who may have less developed networks or less access to mentors.

Performative allyship, or optical allyship, is a pitfall wherein there is no, or minimal, action taken that exemplifies spoken words. Performative allyship draws more attention to the self-ascribed ally than to the cause. Furthermore, although performative allyship is counterproductive and often self-serving, individuals demonstrating performative allyship may lack self-awareness. Although performative allyship is most often attributed to individuals, it can also describe behavior of a majority group or its leadership when public statements of support or allyship are not backed by actions. Performative allyship is often disingenuous and undermines the many challenges faced by individuals from underrepresented groups.

A closely related concept is the White Savior Complex, which refers to individuals motivated by the misconception that they need to save others because the individuals are unable to save themselves [35]. The White Savior Complex is injurious and reduces trust because it implies a lack of self-agency. The flawed thought process of White Saviors fails to see untapped potential in disempowered individuals or groups. It also fails to recognize how structural inequalities promote marginalization and disparities. The White Saviors Complex is evident in contemporary film and culture such as “The Blind Side” or “The Help.” Performative allyship is a near enemy of true allyship in that observers may miss or confuse such behavior as useful or helpful, even though performative allyship hinders progress and stifles potential.

Allyship thus involves self-awareness, a willingness to act, and a tacit acceptance that doing so will not always be well-received. For example, when someone uses pejorative or overtly racist language, a bystander intervention is warranted—that person should be called out. But the intervention might be met with resentment. If a coworker or colleague is receiving unfair treatment, whether disrespect, lack of recognition, or unequitable reimbursement, an ally can speak up for them. Being an ally means showing up and walking the walk both in the moment and in long-term. Some of the practical steps that allies can take to promote change include voting for political and institutional leaders who support just policies; using dashboards to track metrics of equity and impact of efforts; and inviting diverse perspectives or sponsoring a new voice to a leadership role. The next section describes a toolbox, adapted from prior work [40••], which affords practical resources to support acquisition of allyship skills.

Allyship Toolbox: Promoting a Diverse Workforce

The allyship toolbox (Table 2) offers strategies to increase individual accountability, including how to speak up and take action to support an antiracist environment for coworkers and patients. It addresses problematic workplace behaviors from covert microaggressions to conspicuous instances of discrimination or racism. Everyone from front desk staff and nurses to physicians and executive leadership must identify drivers of inequity and examine how their own daily activities may perpetuate them; physicians have influence to promote psychological safety, to support training on unconscious bias, and to foster an environment that is inclusive of individuals and ideas. Critical review of institutional policies should be accompanied by sponsorship at the highest levels of leadership. Underrepresentation is often most accentuated in senior leadership, where influence is greatest.

Table 2.

The allyship toolbox: strategies to promote allyship in otolaryngology

| Allyship toolbox | |

|---|---|

| Strategy | Implementation in otolaryngology |

| Always self-reflect | Make a point to be self-aware, recognizing ways that you can do more and address barriers created by power differentials, societal norms or institutional designations. Consider how policies and the structure of healthcare can systematically advantage some at the expense of others |

| Speak up for others | Do not cast a blind eye. If a coworker, colleague, learner, or patient in otolaryngology is being treated unfairly, take notice, and do something |

| Examples: Perform a bystander intervention if you witness a microaggressions; get a patient timely care | |

| Uplift others | Be a talent scout and find ways to mentor and sponsor across differences. Be intentional and ensure that slates of candidates for leadership roles/opportunities include candidates who are underrepresented in medicine. Invite diversity in all papers, panels, and other positions |

| Read, learn, and educate yourself | Otolaryngology has a growing volume of presentations at national meetings, literature, and other resources to understand challenges in diversity and ways to address them. Also learn from classic books, movies, and other media |

| Have open dialogs | Widen your sphere to include friendships and professional relationships with fellow otolaryngologists with backgrounds different from your own. Listen without judgment, acknowledge problems. Create braves spaces with psychological safety |

| Respond with empathy | Recognize that empathy is complex. Though you may not share another’s lived experience, you can empathize with frustration or unjust treatment. This can be giving voice to a problem in a session at a national conference or a conversation over coffee |

| Confront your own biases | Recognize that we all harbor biases, many of which reside below the threshold of our consciousness. Engage in implicit bias training to learn more about these biases and apply evidence-based strategies to counteract them |

| Create space for others | Turn the spotlight away from ourselves and towards others whose voices are less often heard or ignored; consider how much space is being taken by oneself versus others and ensure that we give credit where credit is due |

| Hold others and ourselves accountable | Take stock of your own actions and apologize—rather than justify—when you make a mistake. When you witness a misstep, intentional or inadvertent, capture that teachable moment to make the otolaryngology workplace and patient care better. As leaders we can shape the culture |

| Identify action items, promote data transparency and measure allyship | Identify the gaps and opportunities related to creating a culture of advocacy for diversity and psychological safety. Accountable allyship involves developing policies and goals with identifiable metrics for health equity workforce diversity, linking to health care outcomes |

| Support economic growth within underserved communities | Champion local sourcing of hires and supply chains when serving in hospital leadership roles; this can include identifying opportunities to help underserved communities thrive through supporting small businesses and creating jobs |

| Assure leadership responsibility and accountability | Leaders create a culture of psychological safety. Leaders may require coaching to develop skills to confront bias. Leaders encourage institutions to learn from bias and inequities and disseminate best practices as expected code of conduct and professionalism |

Allyship also involves adopting a multiplier mindset so that individuals who might be hesitant to speak their mind will put forth their ideas and potential. This increases collective intelligence. Allies embrace diversity in teams, accelerate individual growth, and motivate people to build talent. Allyship is most effective when it is longitudinal, often providing a road map for professional support and advancement. Allies use their power to create a professional environment where individuals can experiment and add their own mark to shared endeavors. The toolbox also addresses what not to do—allies understand that they need to avoid taking up too much space with their own ideas, or “adding too much value.” It is better to hold back, listening and valuing other ideas. An effective ally walks alongside others and is ready to hand over the reins to promote ownership of an initiative. Allies also should think creatively, such as leveraging leadership roles in the hospital to champion local sourcing of hires and supply chains. For example, the Healthcare Anchor Network promotes inclusive, local sourcing, creating intentionality so that individuals and communities that are underserved have more opportunity to thrive [43].

Allyship in Patient Care: Working to Overcome Health Inequity

Whereas workforce allyship involves efforts toward recruitment and retention of URiM individuals and promoting a workforce reflective of society, allyship in frontline healthcare emphasizes equitable healthcare [44, 45, 46•, 47]. Inequities in health care access and utilization, disease prevalence and severity, and health outcomes occur in racial and ethnic minorities, LGBTQ+ individuals, women, and other groups. These disparities have been documented in head and neck cancer, hearing, pediatric disorders, rhinology, sleep medicine, and comprehensive otolaryngology [45, 46•, 48–59]. The pathogenesis of inequities is multifactorial. For example, Black patients more often present with advancedstage disease and are more likely to receive care in lower quality hospitals. [49, 50, 55] Mistrust of healthcare, linked to history of unethical treatment and perception of disrespect [32], exacerbates disparities. Differences in insurance coverage [49, 54], out-of-pocket expenditures [56, 60–63], and difficulty with transportation [62, 64–66] also contribute to presentation with later stage disease and poorer survival outcomes. Allyship involves understanding drivers of disparities and co-developing strategies to mitigate them.

One evidence-based measure that can address social determinants of health is to extend our typical inquiry of social history by utilizing a structural vulnerability questionnaire and assessment tool [67]. The structural vulnerability assessment tool aids in identifying limitations across domains of financial security, food security, social network, and legal status. The tool may prompt clinicians to access resources that improve patients’ ability to adhere to treatment recommendations and follow-up for subsequent care [67]. In addition, the work environment must promote professionalism and accountability around providing high quality, equitable care [68, 69•, 70, 71•]. Patients from historically marginalized communities often have higher risk of undertreatment, as documented in pain management and many otolaryngologic disorders [72–76]. Allyship to ensure equitable care promotes safe, high quality of care. [77] Furthermore, because otolaryngology encompasses speaking and communication, concerns regarding lack of voice are more than symbolic; efforts are needed to ensure a voice for minoritized patients promote delivery of equitable, patient-centered care [78–82].

Otolaryngologists can also promote allyship through equitable, culturally competent, universal health communication with patients. For example, one may recognize patient emotional cues and understand how and when to respond with empathic sentiments (e.g., patient: “I would be up all night shaking her.” Doctor: “That’s a scary thing to go through”) [83]. Another strategy to improve patient-centeredness and allyship is using shared decision-making, including inquiry and incorporation of patient/family concerns and priorities (e.g., effect of disease, fear of surgery, fear of anesthesia, recovery from surgery) into counseling and treatment decisions [84]. Cultural humility is a foremost consideration in understanding the experiences of patients, their families, and the socioecological context in which they live.

Inspiring Allyship: What More Can Formal and Informal Leaders Do?

Organizational allyship plays a pivotal role in our collective efforts to advance equity, diversity, and inclusion in otolaryngology. Fewer than a third of otolaryngologists are women and under 20% of these are URIM individuals [17•]. Therefore, organizations should promote allyship and adopt policies such as grant mechanisms, mentorship programs, second look opportunities, leadership positions, and meeting content that reinforces equity, diversity, and inclusion in our workforce and patient care [85]. Our academic journals have also historically lacked diversity in authorship and editorial composition. Majority leaders should model allyship, both in recognizing their own knowledge gaps or biases and in inspiring actions. Leaders can use their power and influence to drive change, to increase transparency in institutional processes, and to address disparities in hiring, promotion, and compensation. Clearly defined metrics of accountability and transparency of data are essential for cultural change.

To move beyond performative allyship often requires structural change [86, 87•]. Participating in implicit bias training and identifying disparities are necessary preliminary steps, and leaders need to challenge the status quo. Often doing so requires individualized mentoring and coaching in confronting bias, including helping our leaders to understand the experiences of URiM health care providers in the workplace and to recognize challenges, such as the “minority tax” and code switching [22••, 88–91]. Leaders also need to understand imposter syndrome, the persistent inability to believe that one’s success is deserved or has been legitimately achieved because of one’s own efforts or skills, and how to help others overcome it [92–94]. Last, leaders should apply principles of high reliability organizations and root cause analysis with a 360-degree assessment of acts of bias [44]. Dissemination of lessons learned from these assessments and best practices will bring traction and sustainability.

The Science of Allyship: Evidence, Artificial Intelligence, and Immersive Technology

The rapid proliferation of technology presents challenges and opportunities in promoting equity, diversity, and inclusion. The recent expansion of the virtual landscape to include zoom, social media, and other web-based interactions has opened doors for networking [95•]. Allyship has been proposed as a tool for addressing microaggressions in medicine [36], and modules teaching medical allyship have been developed as curricula for resident physician [37, 39] and for faculty [38•]. The evidence-base around allyship will grow as understanding of allyship expands. Among the pitfalls are the need to avoid the “minority tax” amid the expansion of the virtual landscape [22••, 23, 96–98]. The increased facility of communication, the interaction of new fields that might not otherwise interact, and increased access to information open windows of opportunity but also can further overextend already strained individuals.

The promise of artificial intelligence is improved diagnostic precision and enhanced efficiency, but as this technology transforms healthcare, there are potential caveats for underrepresented groups that allies should consider. Increased access to information raises potential concerns for privacy, inequitable representation of various identity groups, and propagation of biased or exclusionary information. In the context of AI “machine bias” can arise from biased data sets or analytic algorithms, with potential detrimental implications for everything from analysis of candidate applicants to the field to diagnostic or therapeutic aspects of patient care. These concerns lead to the need for an “ecosystem” approach to AI development, with a focus on inclusivity, access, thoughtful regulation, and development of algorithms and applications that focus on benefiting marginalized communities [99]. Examples of these beneficial applications including identifying gender bias and other biases in workplace communications and use of employee data to generate workplace-specific DEI strategies [90].

Immersive technologies are another frontier that could influence allyship. The idea of virtually “walking in another’s shoes” has some face validity as an approach to build empathy and foster allyship; however, the published evidence is mixed. A recent meta-analysis suggests that immersive technology may not be more effective than other methods in increasing cross-cultural empathy, and it may stimulate some types of empathy more than others [100]. Otolaryngologists and other health care professionals must critically evaluate the role of both AI tools and immersive technologies in promoting allyship, supporting inclusion in the workplace, and providing equitable care before such approaches are integrated into clinical practices. Advances in technology must align with best practices for promoting equitable sponsorship [101•]. Once algorithms are embedded in our workflows, rooting out machine bias, changing AI systems, and addressing other faults in these technologies will be much more difficult; it therefore behooves us to approach them thoughtfully now with a lens of inclusion, allyship, and inquiry.

Conclusion

Allyship promotes individual and groups’ accountability in creating a culture of inclusion through purposeful actions. Everyone in otolaryngology, not just those from underrepresented or marginalized groups, must work toward the goals of equity, diversity, and inclusion in healthcare. Allyship involves actions that promote a sense of belonging and speaking up for patients, learners, or colleagues. These efforts are made in solidarity with underrepresented or marginalized individuals or communities. Allyship in otolaryngology entails confronting unconscious biases, engaging in self-reflection, and critically assessing policies or practices that perpetuate underrepresentation or health inequity. An allyship toolbox serves as a resource for in-the-moment interventions and for longer horizon diversity efforts. Authentic allyship differs sharply from performative or optical allyship, which emphasize image over actions. Unlocking the power of allyship can promote recruitment, retention, and advancement of diverse leaders, while fostering greater inclusion and working towards elimination of health inequity.

Funding

Emily Boss: National Institutes of Health (NIH), Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development, Understanding Clinician-Parent Interaction to Reduce Disparities and Improve Quality of Pediatric Surgical Care, (Project Number: 1R21HD108565-01A1); and National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Project CONNECTS (Communication and Outcomes that eNhaNce Equity in Childhood Tonsil-lectomy and Sleep) (1 R01 HL166504-01). Evan Graboyes: National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Cancer Institute, Improving the Timeliness and Equity of Adjuvant Therapy Following Surgery for Head and Neck Cancer (Project Number: 5K08CA237858-04); and National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Cancer Institute, A Randomized Controlled Trial to Evaluate a Novel Treatment Strategy for Body Image Related Distress Among Head and Neck Cancer Survivors (1R37CA269385-01). Jennifer Villwock: National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute on Aging, Olfactory Phenotypes as Non-Invasive Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease: a machine learning approach (Project Number: 1R01AG072624-01A1).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Michael J. Brenner reports being President and Board Member for Global Tracheostomy Collaborative (volunteer service; no financial relationship). The other authors declare no competing interests.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.Ellis D Bound together: allyship in the art of medicine. Ann Surg. 2021;274(2):e187–8. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dickenson SR. What is Allyship? https://www.edi.nih.gov/blog/communities/what-allyship (2021). Accessed March 11, 2023.

- 3.Vespa Jm L, David M, et al. Demographic turning points for the United States: population projections for 2020 to 2060. United States Census Bureau; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.•.Francis CL, Cabrera-Muffly C, Shuman AG, Brown DJ. The value of diversity, equity, and inclusion in otolaryngology. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2022;55(1):193–203. 10.1016/j.otc.2021.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Summary of core consideration around diversity, equity, and inclusion in otolaryngology.

- 5.•.Jetty A, Jabbarpour Y, Pollack J, Huerto R, Woo S, Petterson S. Patient-physician racial concordance associated with improved healthcare use and lower healthcare expenditures in minority populations. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021. 10.1007/s40615-020-00930-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Evidence of how patient-physician concordance reduces costs and improves adherence.

- 6.Saha S, Komaromy M, Koepsell TD, Bindman AB. Patient-physician racial concordance and the perceived quality and use of health care. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(9):997–1004. 10.1001/archinte.159.9.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schoenthaler A, Montague E, Baier Manwell L, Brown R, Schwartz MD, Linzer M. Patient-physician racial/ethnic concordance and blood pressure control: the role of trust and medication adherence. Ethn Health. 2014;19(5):565–78. 10.1080/13557858.2013.857764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schoenthaler A, Ravenell J. Understanding the patient experience through the lenses of racial/ethnic and gender patient-physician concordance. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11):e2025349. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.25349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shen MJ, Peterson EB, Costas-Muniz R, Hernandez MH, Jewell ST, Matsoukas K, et al. The effects of race and racial concordance on patient-physician communication: a systematic review of the literature. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2018;5(1):117–40. 10.1007/s40615-017-0350-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stepanikova I Patient-physician racial and ethnic concordance and perceived medical errors. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(12):3060–6. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guevara JP, Wade R, Aysola J. Racial and ethnic diversity at medical schools - why aren’t we there yet? N Engl J Med. 2021;385(19):1732–4. 10.1056/NEJMp2105578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morris DB, Gruppuso PA, McGee HA, Murillo AL, Grover A, Adashi EY. Diversity of the national medical student body-four decades of inequities. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(17):1661–8. 10.1056/NEJMsr2028487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts LM, Mayo AJ, Thomas DA. Race, work, and leadership: new perspectives on the black experience. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robles J, Anim T, Wusu MH, Foster KE, Parra Y, Amaechi O, et al. An approach to faculty development for underrepresented minorities in medicine. South Med J. 2021;114(9):579–82. 10.14423/SMJ.0000000000001290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yancy CW, Bauchner H. Diversity in medical schools-need for a new bold approach. JAMA. 2021;325(1):31–2. 10.1001/jama.2020.23601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Youmans QR, Essien UR, Capers Qt. A test of diversity - what USMLE pass/fail scoring means for medicine. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(25):2393–5. 10.1056/NEJMp2004356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.•.Truesdale CM, Baugh RF, Brenner MJ, Loyo M, Megwalu UC, Moore CE, et al. Prioritizing diversity in otolaryngology-head and neck surgery: starting a conversation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;164(2):229–33. 10.1177/0194599820960722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Summarizes data on lack of diversity in otolaryngology and frames the problem of healthequity.

- 18.Ukatu CC, Welby Berra L, Wu Q, Franzese C. The state of diversity based on race, ethnicity, and sex in otolaryngology in 2016. Laryngoscope. 2020;130(12):E795–800. 10.1002/lary.28447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Association AM: AMA Physician Masterfile. https://www.ama-assn.org/about/masterfile/ama-physician-masterfile (2021). Accessed last accessed 13 Dec 2021.

- 20.Faucett EA, Newsome H, Chelius T, Francis CL, Thompson DM, Flanary VA. African American otolaryngologists: current trends and factors influencing career choice. Laryngoscope. 2020;130(10):2336–42. 10.1002/lary.28420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flanary V, Jefferson GD, Brown DJ, Arosarena OA, Brenner MJ, Cabrera-Muffly C, et al. Leadership of Black women faculty in otolaryngology-more than a rounding error. Laryngoscope. 2023. 10.1002/lary.30552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.••.Faucett EA, Brenner MJ, Thompson DM, Flanary VA. Tackling the minority tax: a roadmap to redistributing engagement in diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;166(6):1174–81. 10.1177/01945998221091696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Explores the problem of the minority tax in otolaryngology with practical solutions forredistributing the workload across the specialty.

- 23.Amuzie AU, Jia JL. Supporting students of color: balancing the challenges of activism and the minority tax. Acad Med. 2021;96(6):773. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000004052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balzora S When the minority tax is doubled: being Black and female in academic medicine. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18(1):1. 10.1038/s41575-020-00369-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown IM. Diversity matters: tipping the scales on the minority tax. Emerg Med News. 2021;43(7):7–9. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campbell KM, Rodriguez JE. Addressing the minority tax: perspectives from two diversity leaders on building minority faculty success in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2019;94(12):1854–7. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodriguez JE, Campbell KM, Pololi LH. Addressing disparities in academic medicine: what of the minority tax? BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:6. 10.1186/s12909-015-0290-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodriguez JE, Wusu MH, Anim T, Allen KC, Washington JC. Abolish the minority woman tax! J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2021;30(7):914–5. 10.1089/jwh.2020.8884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williamson T, Goodwin CR, Ubel PA. Minority tax reform - avoiding overtaxing minorities when we need them most. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(20):1877–9. 10.1056/NEJMp2100179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Campbell KM. The diversity efforts disparity in academic medicine. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(9). 10.3390/ijerph18094529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farlow JL, Mott NM, Standiford TC, Dermody SM, Ishman SL, Thompson DM, Malloy KM, Bradford CR, Malekzadeh S. Sponsorship and negotiation for women otolaryngologists at midcareer: a content analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022; Online Ahead of Print. 10.1177/01945998221102305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prince ADP, Green AR, Brown DJ, Thompson DM, Neblett EW Jr, Nathan CA, et al. The clarion call of the COVID-19 pandemic: how medical education can mitigate racial and ethnic disparities. Acad Med. 2021;96(11):1518–23. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000004139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.•.Ahmadmehrabi S, Farlow JL, Wamkpah NS, Esianor BI, Brenner MJ, Valdez TA, et al. New age mentoring and disruptive innovation-navigating the uncharted with vision, purpose, and equity. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;147(4):389–94. 10.1001/jamaoto2020.5448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Highlights the need for bold new strategies to promote diversity through effectivementorship.

- 34.Munjal T, Nathan CA, Brenner MJ, Stankovic KM, Francis HW, Valdez TA. Re-engineering the surgeon-scientist pipeline: advancing diversity and equity to fuel scientific innovation. Laryngoscope. 2021;131(10):2161–3. 10.1002/lary.29800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Acho E Uncomfortable conversations with a Black man. New York: Flatiron Books; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Babla K, Lau S, Akindolie O, Radia T, Kingdon C, Bush A, Gupta A. Allyship: an incremental approach to addressing microaggressions in medicine. Paed Child Health. 2022;32(7):273–5. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grova MM, Donohue SJ, Bahnson M, Meyers MO, Bahnson EM. Allyship in surgical residents: evidence for LGBTQ competency training in surgical education. J Surg Res. 2021;260:169–76. 10.1016/j.jss.2020.11.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.•.Konopasky AW, Bunin JL. Signaling allyship: preliminary outcomes of a faculty curriculum to support minoritized learners. Acad Med. 2022;87(S132). [Google Scholar]; Describes development of a faculty curriculum to support allyship in medical education.

- 39.Martinez S, Araj J, Reid S, Rodriguez J, Nguyen M, Pinto DB, et al. Allyship in residency: an introductory module on medical allyship for graduate medical trainees. MedEdPORTAL. 2021;17:11200. 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.••.Noone D, Robinson LA, Niles C, Narang I. Unlocking the power of allyship: giving health care workers the tools to take action against inequities and racism. N Engl J Med Catalyst. 2022. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.21.0358. [Google Scholar]; Presents practical tools to leverage allyship to improve healthcare.

- 41.Worcester v. Georgia, 31 U.S. 515 (1832) https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/31/515/ Accessed 11 Mar 2023.

- 42.Network TA-O: Allyship. https://theantioppressionnetwork.com/allyship/ .Accessed 11 Mar 2023.

- 43.Healthcare Anchor Network. https://healthcareanchor.network/2021/06/health-systems-announce-commitment-to-increase-mwbe-spending-by-1b-to-improve-supplier-diversity-build-community-wealth/.Accessed 11 Mar 2023.

- 44.Balakrishnan K, Brenner MJ, Gosbee JW, Schmalbach CE. Patient safety/quality improvement primer, Part II: prevention of harm through root cause analysis and action (RCA(2)). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;161(6):911–21. 10.1177/0194599819878683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Megwalu U, Raol NP, Ikeda AK, Lee VS, Man LX, Shin JJ, Brenner MJ. Growing the evidence base for healthcare disparities and social determinants of health research in otolaryngology–head and neck surgery. Bull Am Acad Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 46.•.Megwalu UC, Raol NP, Bergmark R, Osazuwa-Peters N, Brenner MJ. Evidence-based medicine in otolaryngology, Part XIII: health disparities research and advancing health equity. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;166(6):1249–61. 10.1177/01945998221087138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Provides best practices for advancing the science of health disparities and mitigating healthinequity in otolaryngology.

- 47.Graboyes E, Cramer J, Balakrishnan K, Cognetti DM, Lopez-Cevallos D, de Almeida JR, et al. COVID-19 pandemic and health care disparities in head and neck cancer: scanning the horizon. Head Neck. 2020;42(7):1555–9. 10.1002/hed.26345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kilbourne AM, Switzer G, Hyman K, Crowley-Matoka M, Fine MJ. Advancing health disparities research within the health care system: a conceptual framework. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(12):2113–21. 10.2105/AJPH.2005.077628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kwok J, Langevin SM, Argiris A, Grandis JR, Gooding WE, Taioli E. The impact of health insurance status on the survival of patients with head and neck cancer. Cancer. 2010;116(2):476–85. 10.1002/cncr.24774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu JH, Zingmond DS, McGory ML, SooHoo NF, Ettner SL, Brook RH, et al. Disparities in the utilization of high-volume hospitals for complex surgery. JAMA. 2006;296(16):1973–80. 10.1001/jama.296.16.1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lolic M, Araojo R, Okeke M, Woodcock J. Racial and ethnic representation in US clinical trials of new drugs and biologics, 2015–2019. JAMA. 2021;326(21):2201–3. 10.1001/jama.2021.16680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lopez L 3rd, Hart LH 3rd, Katz MH. Racial and ethnic health disparities related to COVID-19. JAMA. 2021;325(8):719–20. 10.1001/jama.2020.26443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mahal BA, Inverso G, Aizer AA, Bruce Donoff R, Chuang SK. Impact of African-American race on presentation, treatment, and survival of head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2014;50(12):1177–81. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Megwalu UC. Impact of county-level socioeconomic status on oropharyngeal cancer survival in the United States. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;156(4):665–70. 10.1177/0194599817691462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Megwalu UC, Ma Y. Racial disparities in oropharyngeal cancer stage at diagnosis. Anticancer Res. 2017;37(2):835–9. 10.21873/anticanres.11386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mukherjee A, Idigo AJ, Ye Y, Wiener HW, Paluri R, Nabell LM, et al. Geographical and racial disparities in head and neck cancer diagnosis in South-Eastern United States: using real-world electronic medical records data. Health Equity. 2020;4(1):43–51. 10.1089/heq.2019.0092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Carson TL, Aguilera A, Brown SD, Pena J, Butler A, Dulin A, et al. A seat at the table: strategic engagement in service activities for early-career faculty from underrepresented groups in the academy. Acad Med. 2019;94(8):1089–93. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hardeman RR, Medina EM, Kozhimannil KB. Race vs burden in understanding health equity. JAMA. 2017;317(20):2133. 10.1001/jama.2017.4616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jabbour J, Robey T, Cunningham MJ. Healthcare disparities in pediatric otolaryngology: a systematic review. Laryngoscope. 2018;128(7):1699–713. 10.1002/lary.26995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barnes JM, Graboyes EM, Adjei Boakye E, Schootman M, Chino JP, Moss HA, et al. Insurance coverage and forgoing medical appointments because of cost among cancer survivors after 2016. JCO Oncol Pract. 2023:OP2200587. 10.1200/OP.22.00587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Barnes JM, Johnson KJ, Adjei Boakye E, Schapira L, Akinyemiju T, Park EM, et al. Early medicaid expansion and cancer mortality. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113(12):1714–22. 10.1093/jnci/djab135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Graboyes EM, Halbert CH, Li H, Warren GW, Alberg AJ, Calhoun EA, et al. Barriers to the delivery of timely, guideline-adherent adjuvant therapy among patients with head and neck cancer. JCO Oncol Pract. 2020;16(12):e1417–32. 10.1200/OP.20.00271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Massa ST, Chidambaram S, Luong P, Graboyes EM, Mazul AL. Quantifying total and out-of-pocket costs associated with head and neck cancer survivorship. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;148(12):1111–9. 10.1001/jamaoto.2022.3269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chaiyachati KH, Krause D, Sugalski J, Graboyes EM, Shulman LN. A Survey of the national comprehensive cancer network on approaches toward addressing patients’ transportation insecurity. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2023;21(1):21–6. 10.6004/jnccn.2022.7073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Graboyes EM, Chaiyachati KH, Sisto Gall J, Johnson W, Krishnan JA, McManus SS, et al. Addressing transportation insecurity among patients with cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022;114(12):1593–600. 10.1093/jnci/djac134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Graboyes EM, Ellis MA, Li H, Kaczmar JM, Sharma AK, Lentsch EJ, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in travel for head and neck cancer treatment and the impact of travel distance on survival. Cancer. 2018;124(15):3181–91. 10.1002/cncr.31571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bourgois P, Holmes SM, Sue K, Quesada J. Structural vulnerability: operationalizing the concept to address health disparities in clinical care. Acad Med. 2017;92(3):299–307. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brenner MJ, Boothman RC, Rushton CH, Bradford CR, Hickson GB. Honesty and transparency, indispensable to the clinical mission-Part I: how tiered professionalism interventions support teamwork and prevent adverse events. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2022;55(1):43–61. 10.1016/j.otc.2021.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.•.Brenner MJ, Hickson GB, Boothman RC, Rushton CH, Bradford CR. Honesty and transparency, indispensable to the clinical mission-Part III: how leaders can prevent burnout, foster wellness and recovery, and instill resilience. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2022;55(1):83–103. 10.1016/j.otc.2021.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Three-part series that explores the need to hold leaders accountable for creating anenvironment that is supportive and ensures pyschological safety.

- 70.Brenner MJ, Hickson GB, Rushton CH, Prince MEP, Bradford CR, Boothman RC. Honesty and transparency, indispensable to the clinical mission-Part II: how communication and resolution programs promote patient safety and trust. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2022;55(1):63–82. 10.1016/j.otc.2021.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.•.Jamal N, Young VN, Shapiro J, Brenner MJ, Schmalbach CE. Patient safety/quality improvement primer, Part IV: psychological safety-drivers to outcomes and well-being. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022:1945998221126966. 10.1177/01945998221126966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Key concepts around psychological safety, which are foundational in cultivating allyship.

- 72.Anne S, Mims JW, Tunkel DE, Rosenfeld RM, Boisoneau DS, Brenner MJ, et al. Clinical practice guideline: opioid prescribing for analgesia after common otolaryngology operations. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;164(2_suppl):S1–S42. 10.1177/0194599821996297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chua KP, Harbaugh CM, Brummett CM, Bohm LA, Cooper KA, Thatcher AL, et al. Association of perioperative opioid prescriptions with risk of complications after tonsillectomy in children. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;145(10):911–8. 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cramer JD, Barnett ML, Anne S, Bateman BT, Rosenfeld RM, Tunkel DE, et al. Nonopioid, multimodal analgesia as first-line therapy after otolaryngology operations: primer on nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;164(4):712–9. 10.1177/0194599820947013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cramer JD, Gunaseelan V, Hu HM, Bicket MC, Waljee JF, Brenner MJ. Association of state opioid prescription duration limits with changes in opioid prescribing for medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(12):1656–7. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.4281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cramer JD, Anne S, Brenner MJ. Updated centers for disease control and prevention guidelines on opioid prescribing: what should surgeons know? Otolaryngol – Head Neck Surg. In press. 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Brenner MJ, Chang CWD, Boss EF, Goldman JL, Rosenfeld RM, Schmalbach CE. Patient safety/quality improvement primer, Part I: what PS/QI means to your otolaryngology practice. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;159(1):3–10. 10.1177/0194599818779547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brenner MJ, Pandian V, Milliren CE, Graham DA, Zaga C, Morris LL, et al. Global tracheostomy collaborative: data-driven improvements in patient safety through multidisciplinary teamwork, standardisation, education, and patient partnership. Br J Anaesth. 2020;125(1):e104–18. 10.1016/j.bja.2020.04.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Haring CT, Farlow JL, Leginza M, Vance K, Blakely A, Lyden T, et al. Effect of augmentative technology on communication and quality of life after tracheostomy or total laryngectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;167(6):985–90. 10.1177/01945998211013778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Moser CH, Freeman-Sanderson A, Keeven E, Higley KA, Ward E, Brenner MJ, et al. Tracheostomy care and communication during COVID-19: global interprofessional perspectives. Am J Otolaryngol. 2022;43(2):103354. 10.1016/j.amjoto.2021.103354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pandian V, Hopkins BS, Yang CJ, Ward E, Sperry ED, Khalil O, et al. Amplifying patient voices amid pandemic: perspectives on tracheostomy care, communication, and connection. Am J Otolaryngol. 2022;43(5):103525. 10.1016/j.amjoto.2022.103525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zaga CJ, Pandian V, Brodsky MB, Wallace S, Cameron TS, Chao C, et al. Speech-language pathology guidance for tracheostomy during the COVID-19 pandemic: an international multidisciplinary perspective. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2020;29(3):1320–34. 10.1044/2020_AJSLP-20-00089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Leu GR, Links AR, Park J, Beach MC, Boss EF. Parental expression of emotions and surgeon responses during consultations for obstructive sleep-disordered breathing in children. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;148(2):145–54. 10.1001/jamaoto.2021.3530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Callon W, Beach MC, Links AR, Wasserman C, Boss EF. An expanded framework to define and measure shared decision-making in dialogue: a ‘top-down’ and ‘bottom-up’ approach. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101(8):1368–77. 10.1016/j.pec.2018.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Brenner MJ, Nelson RF, Valdez TA, Moody-Antonio SA, Nathan CO, St John MA, et al. Centralized otolaryngology research efforts: stepping-stones to innovation and equity in otolaryngology-head and neck surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;166(6):1192–5. 10.1177/01945998211065465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Smith JB, Chiu AG, Sykes KJ, Eck LP, Hierl AN, Villwock JA. Diversity in academic otolaryngology: an update and recommendations for moving from words to action. Ear Nose Throat J. 2021;100(10):702–9. 10.1177/0145561320922633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.•.Villwock JA. Meaningfully moving forward through intentional training, mentorship, and sponsorship. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2021;54(2):xxi–xxii. 10.1016/j.otc.2021.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Synopsis of best practices in mentorships and sponsorship in otoloaryngology.

- 88.Amutah C, Greenidge K, Mante A, Munyikwa M, Surya SL, Higginbotham E, et al. Misrepresenting race - the role of medical schools in propagating physician bias. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(9):872–8. 10.1056/NEJMms2025768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, Merino YM, Thomas TW, Payne BK, et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(12):e60–76. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.R P: Artificial intelligence: the new frontier for confronting gender bias. https://www.catalyst.org/2019/03/13/artificial-intelligence-gender-bias/ .Accessed 11 Mar 2023.

- 91.Does race interfere with the doctor-patient relationship? JAMA. 2021;326(7):679–80. 10.1001/jama.2021.10464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Levant B, Villwock JA, Manzardo AM. Impostorism in American medical students during early clinical training: gender differences and intercorrelating factors. Int J Med Educ. 2020;11:90–6. 10.5116/ijme.5e99.7aa2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Levant B, Villwock JA, Manzardo AM. Impostorism in third-year medical students: an item analysis using the Clance impostor phenomenon scale. Perspect Med Educ. 2020;9(2):83–91. 10.1007/s40037-020-00562-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Villwock JA, Sobin LB, Koester LA, Harris TM. Impostor syndrome and burnout among American medical students: a pilot study. Int J Med Educ. 2016;7:364–9. 10.5116/ijme.5801.eac4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.•.Ortega CA, Keah NM, Dorismond C, Peterson AA, Flanary VA, Brenner MJ, et al. Leveraging the virtual landscape to promote diversity, equity, and inclusion in Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery. Am J Otolaryngol. 2023;44(1):103673. 10.1016/j.amjoto.2022.103673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; An in-depth examination of how expansion of the virtual landscape has createdopportunities for advancing diversity, equity and inclusion.

- 96.Cyrus KD. A piece of my mind: medical education and the minority tax. JAMA. 2017;317(18):1833–4. 10.1001/jama.2017.0196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gewin V The time tax pu0074 on scientists of colour. Nature. 2020;583(7816):479–81. 10.1038/d41586-020-01920-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Joseph TD, Hirshfield LE. Why don’t you get somebody new to do it?’ Race and cultural taxation in the academy. Ethn Racial Stud. 2010;34(1):121–41. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Forum WE: a blueprint for equity and inclusion in artificial intelligence. White paper. https://www.weforum.org/whitepapers/a-blueprint-for-equity-and-inclusion-in-artificial-intelligence/ .(June 29, 2022). Accessed 11 Mar 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Martingano AJ, Hererra F, Konrath S. Virtual reality improves emotional but not cognitive empathy: a meta-analysis. Technol Mind Behav. 2021;2. [Google Scholar]

- 101.•.Farlow JL, Wamkpah NS, Bradford CR, Francis HW, Brenner MJ. Sponsorship in otolaryngology – head & neck surgery: a pathway to equity, diversity, and inclusion. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]