Abstract

Task shifting (TS) is the redistribution of healthcare services from specialised to less-qualified providers. Need for TS was intensified during COVID-19. We explore what impact TS had on service delivery during the pandemic and examine how the pandemic affected TS strategies globally. We searched five databases in October 2022, namely Medline, CINAHL Plus, Elsevier, Global Health and Google Scholar. 35 citations were selected following the PRISMA-ScR guidelines. We analysed data thematically and utilised the WHO health systems framework and emergent themes to frame findings. We uncovered instances of TS in countries across all income levels. 63% (n = 22) of the articles discussed the impact of TS on healthcare services. These encompassed services related to mental healthcare, HIV, sexual and reproductive health, nutrition and rheumatoid diseases. The remaining 37% (n = 13) focused on how the pandemic altered strategies for TS, particularly in services related to mental healthcare, HIV, hypertension, diabetes and emergency care. We also found that studies differed in how they reported TS, with majority using terms “task shifting”, followed by “task sharing”, “task shifting and sharing” and “task delegation”. Our analysis demonstrates that TS had a substantial impact across healthcare systems. Modifying roles through training and collaboration strengthened workforce and enhanced diagnostic services. Strategic leadership played a crucial role in the process. More research on the financial aspects of TS during pandemics is required. Stakeholders generally accepted TS, but transferring staff between healthcare programs caused unintended disruptions. The pandemic reshaped TS, moving training, patient care and consultations to digital platforms. Virtual interventions showed promise, but digital access remained a challenge. Healthcare organisations adapted by modifying procedures, pathways and staff precautions. We recommend refining strategies for TS, and expanding on it to address workforce shortages, improve access, and enhance services, not only during crises but also beyond.

Background

Shortage of skilled human resources for healthcare (HRH) makes healthcare systems and services vulnerable to fragmentation. Projections of global HRH deficits by the year 2035 range between 12.9–18 million [1,2]. Changing demographics and disease patterns, burdens of non-communicable diseases and emerging infections demand a larger qualified workforce. Given the correlation of provider numbers to service access, countries must instate appropriate ratios of skilled providers to population through workforce development [3]. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) impacted services worldwide and has slowed progress towards sustainable development goal–3 of achieving ‘healthy lives and well-being for all’ [4,5]. Countries diverted finances, infrastructure and HRH towards caring for SARS-CoV-2 cases. Although resource-constrained settings were disproportionately impacted, the pandemic also affected nations with richer densities of facilities and HRH [6]. A survey across 105 World Health Organization (WHO) member nations reported that nine among 10 countries experienced major disruptions in essential healthcare services, further aggravating disease burdens of pre-COVID eras [7]. For instance, prevalence of anxiety and depression increased by 25%, with young people and women hit the worst [8]. Increase in depressive disorders costed over 49 million disability-adjusted life years [9]. Mortality due to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections, tuberculosis and malaria are modelled to shoot by 10%, 20% and 36% respectively over the next five years [10].

Healthcare services can be improved by promoting innovation in diagnosis and treatment, especially by expanding on task shifting and task sharing (TS/S) [11]. TS/S are two approaches that move certain tasks which are typically performed by highly trained professionals, such as doctors, onto other providers and caregivers who have lesser training, such as nurses or community healthcare workers (CHWs) [12]. Often used synonymously, TS/S have differences. While task shifting (TS) focuses on providers assuming new roles through delegation from one hierarchy to other, task sharing is not as territorial and allows providers to expand duties by collaborating [13–15]. Both approaches remove bottlenecks in service provision in resource-limited settings by engaging existing HRH efficiently or by creating new cadres suitable to perform tasks [13,16]. TS/S should ideally be achieved by characterising tasks to be shifted or shared, subjecting new cadres to competency-based trainings and through continuous supervision and evaluation. This ensures that delegation is safe and effective, and the care delivered is of high quality [16]. TS/S has been used as pragmatic responses to low provider availability and acute demands. Chinese barefoot doctors [17], Russian Feldshers [18] and French Officiers de Santé [19] are historical examples whereby preventive care, diagnostics, treatment and emergency care have been delivered by less-specialised but trained caregivers in lieu of specialised providers. TS/S has been used in surgery, obstetrics, anaesthesia and ophthalmic procedures [20,21]. Experiences with HIV in Africa, led to classification of TS into five types, each involving distinct providers and functions [22]. Extensive work in this context subsequently led to the development of WHO global guidelines and recommendations on investing in TS/S, enabling policies and facilitating implementation of TS through service reorganisation [16].

The pandemic has exacerbated challenges posed by workforce shortages. Assessing impacts of TS/S during this crisis can offer insights into workforce strengthening strategies. This is particularly relevant as public health, humanitarian and climate-related emergencies are anticipated to occur more frequently, raising the question whether TS/S can be used as a tool in addressing such situations in the future. Few reviews have analysed how TS/S can benefit health systems beyond the pandemic. For instance, shifting psychotherapy to trained non-specialists can increase timely access to mental healthcare [23–25]. Integrating TS into hypertension, diabetes and obstructive lung diseases management models could preserve care continuum during future pandemics [26]. Task sharing family planning services with CHWs can lessen pregnancy-related mortality and child morbidity [27]. Human papillomavirus screening and vaccine education through CHWs could help fight cervical cancer [28]. While there exists literature on TS/S with respect to individual diseases or health issues based out of one or few comparable contexts, to our best knowledge our review is the first to study TS as a tool in its own right, specifically in light of a global pandemic.

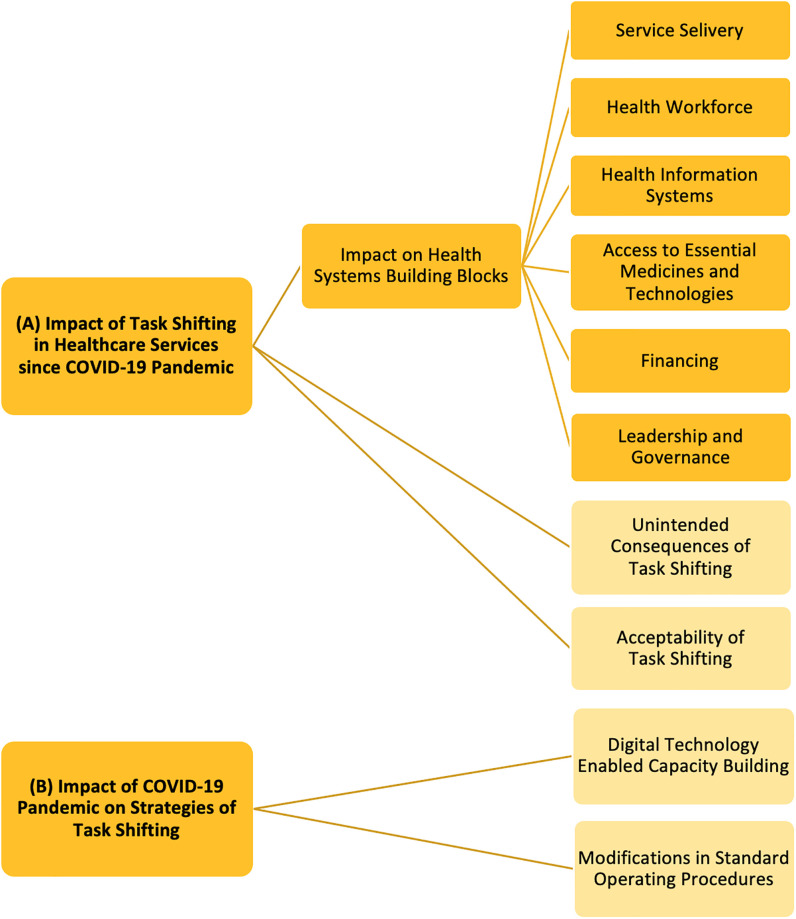

We visualise (A) the impact of TS in healthcare services delivery since the onset of COVID-19 and (B) the impact the pandemic has had on strategies used to implementing TS; both at the global setting. We assess the former using the WHO health systems framework [29]. We chose the WHO health systems framework as it provides an internationally recognised comprehensive structure for assessing health system performance. This approach enabled us to understand how TS benefited service delivery, the workforce, information systems, access to medicines and technology, financing mechanisms and governance; all vital aspects to fathom the overall effectiveness of different countries’ responses to the pandemic and to identify areas which need reinforcement. Indeed, studies have applied the framework to evaluate impacts of public health emergencies on health systems previously. For example, during the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, researchers used this framework to conclude that efficient workforces are crucial for swift outbreak responses and that good-quality services relies heavily on the success of other blocks, such as proper financing and effective leadership and governance [30]. Similarly, we have applied the framework in context of COVID-19 to investigate how the sudden surge in cases strained systems and HRH worldwide. And then we continue on to shed light on how implementation strategies of TS evolved because of the pandemic.

Methodology

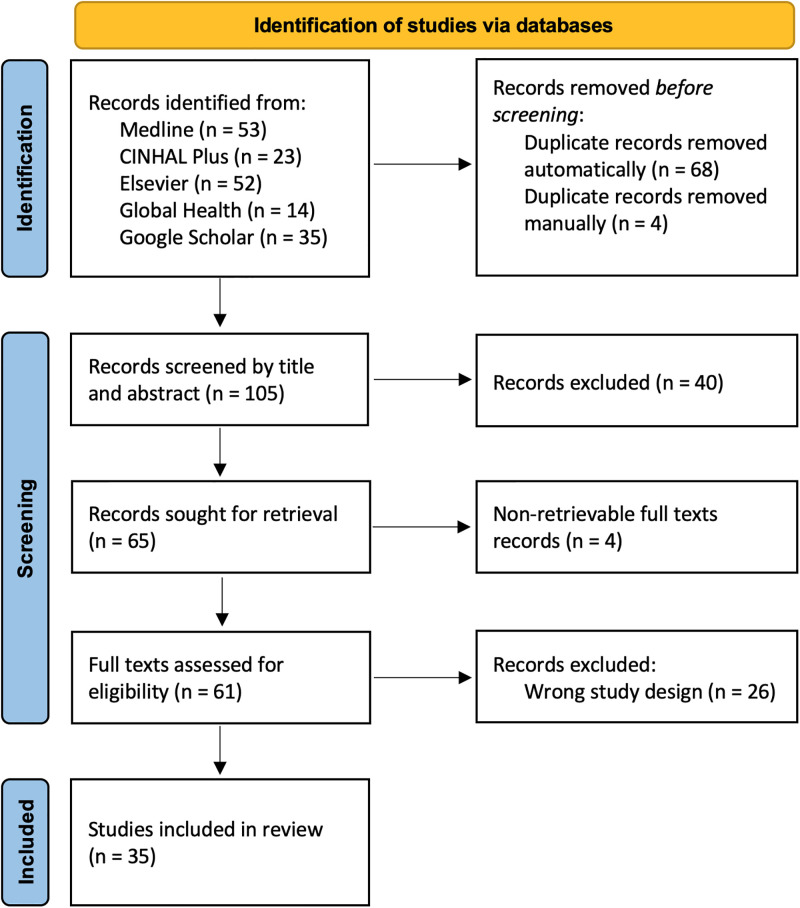

Our scoping review aimed to explore two questions: (A) What impact has TS had in healthcare services globally since the onset of COVID-19 pandemic? (B) How has the pandemic impacted strategies of implementing TS worldwide? We used the following words and variations thereof to develop a search query: (“task shifting” OR “task sharing” OR “task shifting and task sharing” OR "task transfer" OR "task delegation” OR “TS/S”) AND (“healthcare” OR “health” OR “healthcare services”) AND (“COVID-19” OR "coronavirus” OR "covid-19 pandemic"). Search query was run across five databases in October 2022, namely Medline, CINAHL Plus, Elsevier, Global Health and Google Scholar. 177 citations were found and imported onto Covidence software [31] for screening. Duplications were removed. Records were first screened by titles and abstracts. Irrelevant articles were excluded. Full texts of relevant articles were sought and assessed. To examine eligibility, we applied a structured ‘Population, Concept and Context’ framework [32]. We included articles concerning any type of healthcare providers and caregivers (population). We included articles if they discussed TS from more to less specialised HRH (content). We included articles from all countries, spanning from onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in November 2019 (context). Only citations in English were included. Reviews, commentaries and theses were excluded. PRSIMA-ScR guidelines [33] were followed to screen and report citations (Fig 1). SD performed the initial screening. LG supervised the screening to ensure accuracy and consistency. Any discrepancies that arose during screening were addressed through discussions. 35 citations were selected in our final review. We also conducted a citation search to identify supplementary articles. However, no additional articles were found. From the final list of citations, we extracted key information, such as aim of study, terminology used to describe TS, country or context of study, study design, health conditions addressed, services shifted or shared, reasons for TS, cadres of HRH tasks moved from and moved onto, training provided to enable TS, results and conclusions of the study, and author recommendations. We analysed data thematically [34] using a deductive and inductive hybrid approach [35]. To investigate question (A), we began with a deductive phase. We used six predefined categories based on the building blocks of the WHO health systems framework [29]. We complemented this with an inductive phase, allowing us to explore additional emergent perspectives, further adding two more themes. In investigating question (B), two themes emerged inductively. Fig 2 depicts the coding tree used for analysis. The iterative process of combining deductive and inductive approaches proved to be effective in uncovering both structured and unforeseen insights. Detailed search strategy and protocol is included as S1 File.

Fig 1. PRSIMA-ScR flow diagram of search and selection process of citations.

Fig 2. Coding frames used to undertake thematic analysis.

Deductive themes represented in deep yellow colour. Inductive themes represented in light yellow colour.

Results

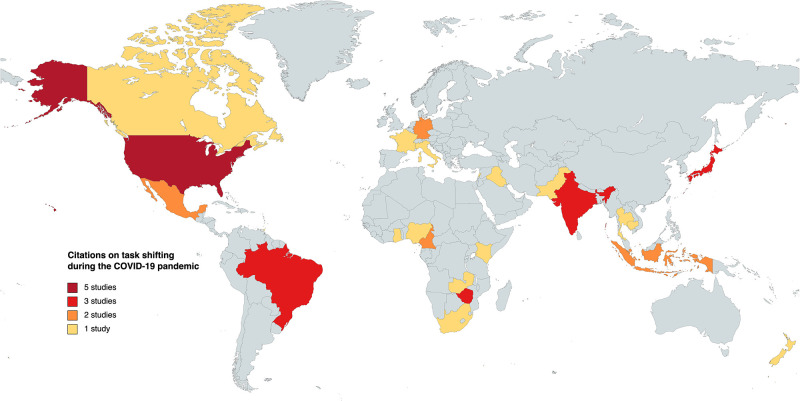

Our search covered articles discussing the impact of TS in health services since the pandemic across various domains. We found that 63% of the citations explored how TS affected health services, encompassing areas such as COVID-19 care (n = 14), mental healthcare (n = 2), HIV (n = 3), sexual and reproductive health (n = 1), nutrition (n = 1) and rheumatoid diseases (n = 1). The remaining 37% examined how the pandemic influenced strategies for TS, focusing on services related to mental healthcare (n = 7), HIV (n = 3), chronic illnesses including hypertension and diabetes (n = 2), alternative care modalities (n = 1) and emergency care (n = 1). These studies were drawn from a set of 25 countries, categorised based on their income levels: high-income countries (n = 9), upper middle-income countries (n = 5), low- and middle-income countries (n = 9) and low-income countries (n = 2). We visualised this distribution on a global map (Fig 3). An interesting finding was the variation in terminology used to describe the phenomenon of TS from specialised to less-qualified providers. We identified that 71.43% of the articles employed the term "task shifting" (n = 25), while 20.0% used "task sharing" (n = 6), 5.71% combined "task shifting and sharing" (n = 3) and 2.86% mentioned "task delegation" (n = 1). Table 1 presents our findings organised as evidence of the impact of TS on healthcare services worldwide since the onset of the pandemic. Table 2 outlines the impact of the pandemic on the strategies employed for implementing TS.

Fig 3. Global distribution of task shifting in healthcare services delivery since the onset of COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 1. Examples of task shifting in healthcare services delivery since COVID-19 pandemic.

| Study | Country of study | Tasks shifted | HRH delivering services | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 testing, surveillance, communication and care management | ||||

| Zafar, S et al [36] | Pakistan | Testing, contact tracing and risk communication | Lady Health Workers and Dengue Outreach Workers (CHWs) |

|

| Gudza-Mugabe, M et al [37] | Zimbabwe | Testing, contact tracing and reporting | Laboratory technologists |

|

| Honda, C et al [38] | Japan | Contact tracing, reporting and hospital coordination | Part time public health nurses (PHN) |

|

| Chidavaenzi, NZ et al [39] | USA | Testing, contact tracing, reporting and isolating | Public health staff at health department, Staff at detention centre and casino (non-healthcare staff) |

|

| Raskin, SE et al [40] | USA | Testing, contact tracing, reporting and telephone-based risk communication | Dental assistants and dental hygienists |

|

| Mohammed, A et al [41] | Nigeria | In-patient COVID care and other essential services | Medical students |

|

| Taylor, MK et al [42] | Multi-country (Singapore, Trinidad and Tobago, Iraq, India USA, Brazil and more) |

Testing, contact tracing, triaging, risk communication and in-patient COVID care | Primary care physicians, medical students |

|

| Eggleton, K et al [43] | New Zealand | Telephone triaging and nursing care | Nurses and practice receptionists |

|

| Yoshioka-Maeda, K et al[44] | Japan | Telephone consultations | Office support staff (non-healthcare staff) |

|

| Yoshioka-Maeda, K [45] | Japan | Telephone consultations, information management, resource management | Office support staff and external company (non-healthcare staff) |

|

| Helmi, M et al[46] | Indonesia | Intensive care services | General practitioners and medical students |

|

| Sono-Setati, ME et al [47] | South Africa | Clinical auditing and resource management | Hospital staff (not specific) |

|

| Köppen, J et al[48] | Germany | Emergency procedures for infection control | Emergency paramedics |

|

| Faria de Moura Villela, E et al [49] | Brazil | In-patient COVID care and emergency medical services | Physicians, nurses and hospital staff |

|

| Mental health screening and therapeutic interventions | ||||

| Ortega, AC et al [50] | Mexico | Psychosocial support, psychological first aid, grief management and palliative mental health services | Primary care physicians, community healthcare workers and non-clinical office staff |

|

| Mukhsam, MH et al [51] | Malaysia | Psychosocial support | Medical students |

|

| HIV consultation, testing, counselling and treatment services | ||||

| Omam, LA et al [52] | Cameroon | Counselling, testing, patient follow ups, Antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation and refilling | Primary care physicians, nurses and non-clinical staff |

|

| Pry, J.M. et al [53] | Zambia | ART initiation and refilling, community mobilisation | CHWs |

|

| Abraham, SA et al [54] | Ghana | Prescribing and dispensing ART | Nurses |

|

| Others: Sexual and reproductive health; Nutrition; Rheumatoid diseases | ||||

| Jacobi, L et al [55] | USA | Provision of contraceptives and dispensing medicines | CHWs |

|

| Davis, C. et al [56] | Singapore | Behaviour contracts for nutrition | General physicians and nurses |

|

| Kuhlmann, E et al [57] | Germany | Care for rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory musculoskeletal disorders | General practitioners, rheumatology specialist assistants and other medical assistants |

|

Table 2. Examples of the impact of the pandemic on strategies for task shifting.

| Study | Country of study | Task shifted | HRH delivering services | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental health screening and therapeutic interventions | ||||

| Singla, DR et al [58] | Multi-country (USA and Canada) | Screening and therapy for perinatal anxiety and depression | Nurses and midwives |

|

| Scazufca, M et al [59] | Brazil | Screening, referring and therapy for depression | CHWs |

|

| Jordans, MJD et al [60] | Lebanon | Psychological intervention for children with severe emotional distress | CHWs |

|

| Dambi, J et al [61] | Zimbabwe | Screening and therapy for depression | Grandmothers |

|

| Nirisha, PL et al [62] | India | Screening and referring patients with alcohol use disorders and mental health for depression | Accredited social health activists (ASHA, who are CHWs) |

|

| Philip, S et al [63] | India | Screening and referring patients with substance abuse and mental health for depression | Primary care physicians |

|

| Rodriguez-Cuevas, F et al [64] | Mexico | Psychosocial support, psychological first aid and grief management | Primary care physicians, community healthcare workers, community mental healthcare workers and non-clinical office staff |

|

| HIV consultation, testing, counselling and treatment services | ||||

| Coulaud, P et al [65] | Cameroon | Consultation, counselling and ART | Nurses |

|

| Lujintanon, S et al [66] | Thailand | ART initiation | Community healthcare workers |

|

| Roche, SD et al [67] | Kenya | Consultation, counselling and ART delivery | Hospital staff (not specific) |

|

| Others: Chronic illnesses including Hypertension, Diabetes; Emergency medical services | ||||

| Kamvura, TT et al [68] | Zimbabwe | Screening of Hypertension and diabetes | Nurses and community health workers (grandmothers) |

|

| Oikonomidi, T et al [69] | France | Consultations and prescribing drugs for chronic illnesses | Digital technology-supported provision of care |

|

| Iwamoto, A et al [70] | Cambodia | Emergency bag-and-mask ventilation, incubator-side tube feeding and temperature measurement | Family caregivers (Fathers and grandmothers) |

|

We now present our findings grouped under the specific 10 analytical themes discussed previously in the methodology section.

Service delivery

To combat the surge in SARS-CoV-2 cases, governments focused on epidemiological surveys. In Arizona, USA, a large-scale rapid antigen-based serial screening initiative involved non-clinical staff from local health departments and detention centres. They were trained in sample collection, reporting, confidentiality and administration. Over 28 days, they conducted 3,834 tests on 716 individuals, resulting in only one positive case. Despite factors like community immunity, vaccinations and social distancing, this TS significantly reduced transmission [39]. The pandemic also heightened the need for mental healthcare. Mexican organisation Compañeros En Salud and the Chiapas health ministry trained primary care physicians, CHWs and non-clinical staff in psychological first aid and referrals. These HRH received pocket guides to offer psychosocial support to the community. CHWs included anxiety and suicidal thought assessments in home-visit questionnaires. They cared for grieving patients and referred severe cases to higher-level care. This approach expanded care coverage, addressing stressors stemming from the pandemic and offering solutions to fill service gaps in resource-limited settings [50].

Health workforce

During the pandemic, roles were reassigned to meet increased demands. For instance, in the USA, primary care physicians shifted to intensive care, while in Brazil, final year medical students assisted with SARS-CoV-2 cases. In Singapore, tasks traditionally performed by psychologists, such as drafting nutrition behaviour contracts for patients and caregivers, were taken on by physicians and nurses [42]. Increased workloads among public health nurses (PHN) in Tokyo caused anxiety, frustration and fatigue, leading to task shifts to part-time PHN, other nursing staff and support personnel [38]. Teleconsultations by PHN during the first wave focused on prevention measures and referral pathways, prompting managers to shift these tasks to lower-level staff and office workers using scripted manuals. This allowed PHN to concentrate on infection control and management [44]. In Ghana, the central teaching hospital adapted staff roles and schedules to transfer medication prescribing and ART dispensing from pharmacists to nurses, ensuring ART continuity and reducing patient waiting times at HIV clinics [54]. While TS typically refers to transfer of responsibilities from more to less specialised providers, the pandemic saw instances where highly-qualified providers assumed roles traditionally performed by less-qualified counterparts. Primary care physicians conducted fieldwork to screen, test and triage patients in Singapore, Trinidad and Tobago, and raised awareness about social distancing, symptoms and quarantine in Iraq and India. In Italy, a shortage of nursing staff led primary care physicians to perform nursing procedures and therapies [42]. Dental hygienists from dental clinics were redirected towards community screening and telehealth services to educate community members [40].

Health information systems

Sub-standard medical record management during the pandemic resulted in clinical auditing system failures. A multi-hospital study in South Africa recommended TS data collection and audit reporting from clinical staff, particularly emergency healthcare providers, to other HRH to enhance care and coordination. This shift helped reduce mortality, morbidity, stress and burnouts [47]. Japanese PHN moved teleconsultations to office staff and developed web-based data systems for exchanging COVID-19 patient information. They also shifted hospital coordination, clerical tasks and inventory management to external companies, which saved nursing time, reduced workloads and improved supply allocation efficiency [45].

Access to essential medicines and technologies

Centralised testing, limited HRH and logistical challenges created difficulties in meeting testing demands. To enhance access, expand testing capacity and accelerate reporting, Zimbabwe shifted antigen-based diagnostics testing to laboratory technicians. These technicians received training in testing techniques, simultaneous to upgrading testing equipment with COVID-specific software. By TS testing onto laboratory technicians, Zimbabwe decentralised testing from a single facility to over a thousand centres, increasing testing availability and uptake and reduced report turnaround time to less than a day and mitigated staff burnout [37].

Financing

Our search did not yield economic evaluations of TS since the pandemic. Nevertheless, one article, which discusses the successful decentralisation of ART in Cameroon, highlights the value of economic evaluations for TS-based models. The intervention involved establishing mobile units and transferring testing, counselling, ART initiation, refilling and follow-up to non-clinical staff within primary care and community-based facilities. While the intervention enhanced service access, particularly in conflict-affected regions, the authors underscores the importance of conducting economic evaluations for TS-based models before considering their expansion into other hard-to-reach settings [52].

Leadership and governance

Timely preparedness plans and implementation aided pandemic management. For instance, a case study examined the German Federal and State policies regarding TS [48]. While Federal policies recommended TS, states did not fully incorporate these recommendations. The Federal infection control law authorised TS from doctors to paramedics, emphasising their competencies, non-involvement with severe patients and documentation. However, the law lacked specifics. Only Saxony-Anhalt’s state policies elaborated on these competencies, aligning them with treatment protocols and documentation tools. The lack of comprehensive guidance hindered nationwide TS adoption. Foresighted direction at all organisational levels was key. Hospitals acknowledged the necessity for TS in intensive care units (ICUs), recognising resource constraints. An evaluation in Indonesia identified inadequacies in space, equipment and specialist distribution. To address these, leaderships initiated TS within ICUs through training on rights, responsibilities, communication, coordination and incentives for providers [46]. At the University Malaysia Sabah in Borneo, strategies were implemented to mitigate COVID-19’s impact, with a focus on mental health through TS. Stringent policies on screening, personal protective equipment (PPE) and attendance were enforced, supported by dedicated teams for surveillance, health promotion, quarantining and sanitation. In a unique approach, local medical students proficient in Mandarin supervised quarantined international Chinese students, providing psychosocial support and health education. These actions prevented COVID-19 importation into the campus [51]. Another case study on Zambia’s COVID-19 mitigation guidelines for HIV demonstrated that swift policy implementation reduced interruptions in ART delivery. The government’s recommendations included dispensing six multi-month ART supplies to patients and TS for patient communication and mobilisation through trained lay providers. This increased early ART collections, with a more than fourfold rise in weekly multi-month dispensations and a reduction in late visits [53].

Unintended consequences of task shifting

TS also resulted in unintended consequences. Government-employed CHWs in Islamabad were trained for surveillance and deployed to identify SARS-CoV-2 cases and bring patients for testing. However, this led to them abandoning their other engagements within maternal health and immunisation programs; creating service gaps [36]. In Brazil, about three-quarters of doctors, nurses and hospital staff experienced structural changes and role shifts. Most TS occurred in COVID-19 wards, ICUs and emergency departments. These role changes often coincided with salary cuts and increased levels of anxiety and depression among staff [49]. The pandemic also transformed doctor-patient relationships and the nature of practice teams. In New Zealand, receptionists at General Practitioners (GPs) were upskilled in telephone triaging and routing patients to consultations, nursing care or other facilities. Nurses and receptionist teams ran separate respiratory units for triaging patients with symptoms to prevent transmission, and these patients were seen by GPs separately. While TS improved outputs and freed GPs to attend patients, managing different patient streams added to workloads of nurses and receptions, necessitating support staff hires [43].

Acceptability of task shifting

TS, which is generally met by resistance from healthcare providers, was accepted during the pandemic. For example, the success of CHWs in contraceptives and medicine dispensing that improved family planning services access, made stakeholders view TS as necessary during workforce shortages [55]. In Germany, a shortage of rheumatologists led to care for rheumatoid arthritis and musculoskeletal disorders being delegated to GPs and rheumatology specialist assistants. In fact, rheumatologists found TS to specialist assistants more useful than delegating to GPs. Workforce shortages primed stakeholders toward TS, showcasing its feasibility and acceptability [57]. Surveys in Nigerian teaching hospitals assessed student knowledge and provider willingness for COVID care. About 90% of students expressed willingness to assist, although they had concerns about infections and parental disapproval [41]. TS onto medical students with suitable training effectively boosted service capacity.

Digital technology enabled capacity building

COVID-based containments caused interventions cease routine activities and rapidly adopt new delivery models. SUMMIT trial is TS behavioural activation for perinatal depression and anxiety from psychologists, psychiatrists and social workers onto nurses and midwives [58]. Lockdowns in USA and Canada caused training and supervision of providers, follow-ups and data collection to migrate onto patient-centred virtual systems. Likewise, the PROACTIVE study, which assessed effectiveness of psychoeducation-based support for older adults delivered by trained CHWs with no higher education or formal training, had to resort to telephone-based care due to lockdowns in Brazil. This transition led to a higher recovery rate of 62.5% among participants receiving virtual care, compared to 44% among those receiving care as usual [59]. Another study from Lebanon demonstrated that online-delivered competency-driven training significantly improved facilitator abilities in providing psychological treatment to distressed adolescents by 18%, highlighting the potential of telemedicine-supported community-based mental health interventions [60]. Similarly, Friendship Bench, which shifts screening and psychological support for common mental disorders to trained grandmothers, adapted to digital platforms during lockdowns. A pilot study of their chat-based application in Zimbabwe found the implementation feasible and effective. Users experienced reduced depression and anxiety and improved quality of life [61]. The Friendship Bench model was also extended to include screening for comorbid conditions like diabetes and hypertension, maximising the benefits of TS [68].

Two Indian studies on substance use and addiction demonstrate how digital training improved mental health screening and provider competence. In one study, virtually trained CHWs identified significantly more alcoholism cases (83%) and showed improved knowledge, attitude and practice scores compared to in-classroom trained providers [62]. In another study, primary care physicians, virtually trained and monitored by specialists, saw a 37% increase in knowledge scores [63]. These results suggest the potential for online capacity building at the primary care level. Monitoring and physician consultations in the decentralisation of ART initiation onto trained lay providers in Bangkok also transitioned to virtual platforms. Insights from this TS-based trial can aid in addressing geographical and HRH challenges [66].

COVID-19 reshaped healthcare practices, emphasising on online health-seeking behaviour and delivery. A French survey assessed post-pandemic preferences, with a shift towards teleconsultations and symptom-checking applications over traditional physician-led methods. Notably, 22% of patients with chronic illnesses preferred online symptom-checkers for new symptoms. While many found digital TS suitable as pre-consultation tools, it was not found universally appropriate, especially for patients with anxiety or complex symptoms. Patients emphasised that TS to digital applications should involve accreditation by quality control authorities and physician supervision [69].

Modifications in standard operating procedures

Organisations modified their standard operating procedures to protect staff during the pandemic. Organisations that deploy trained non-specialists to deliver mental health services, extended their scope to address pandemic-related stress and anxiety. Providers undertook patient-home visits outdoors while using extensive PPE [64]. Neonatal ICUs in Cambodia shift incubator-side tube feeding and bag-and-mask resuscitation onto fathers and grandmothers. Due to concerns about family transmission of SARS-CoV-2, thermal scanning, sanitation, symptom-based questionnaires and contact tracing were implemented as an additional measure. Facilities also hired and trained additional nurses to reduce reliance on TS with family caregivers, reversing some progress made with TS [70]. In Kenya, the one-stop shop model improved PrEP delivery, uptake and continuation. By relocating client files, equipment and drugs to one-stop shops and delegating PrEP dispensing to lower cadres, staff movement and waiting times were reduced. However, increasing caseloads and social distancing measures led to transforming of one-stop shops into isolation centres and the relocation of one-stop shop operations to distant community clinics, resulting in time and productivity losses [67]. Likewise, in Cameroon, district-level centres employed TS of ART prescription and administration onto nurses to maintain ART continuation [65].

Discussion

(A) Impact of task shifting on healthcare services globally since the onset of COVID-19 pandemic

The WHO’s early recommendation of TS/S as a response to COVID-19 set the stage for this crucial healthcare strategy. As our study reveals, TS was pivotal in addressing challenges posed by the pandemic. Delegation of COVID-19 screening and contact tracing to non-clinical staff helped reduce transmission rates [39], underlining the effectiveness of TS in dealing with such crises Furthermore, training of primary care physicians and CHWs to provide psychosocial and palliative support expanded the reach of mental health services during the pandemic, particularly in resource-constrained settings [50]. These innovative solutions not only tackled the immediate issues brought on by the pandemic but also exemplified the adaptability and resilience of TS in service delivery, providing valuable lessons for future crises. Interestingly, some scenarios saw more-qualified providers stepping into roles traditionally performed by less-qualified counterparts. For example, primary care physicians took on responsibilities such as screening, triaging and community education. They even performed nursing procedures [42]. The specific strategies employed to utilise the healthcare workforce varied among countries, but the common thread was the implementation of TS through rational reorganisation, cross-training and collaboration. This flexibility proved instrumental in managing the multifaceted challenges posed by COVID-19. This evidence demonstrates that TS is not only a practical approach to the current pandemic but also a vital component in building systems that can withstand the demands of future crises, ensuring continued access to essential services and adapting to shifting circumstances. It showcases how healthcare systems can optimise their available resources and enhance capacity to respond swiftly and effectively when faced with unforeseen challenges.

The pandemic revealed limitations in health information systems, particularly in managing medical records and conducting clinical audits [47]. This inadequacy prompted the adoption of TS as a strategic response to enhance the reliability and efficiency of these systems. The inclusion of non-clinical staff in data management, as demonstrated in Japan where PHN shifted teleconsultations to office staff, has proven to be a versatile solution that mitigates burnouts among emergency care providers, thus improving care coordination and reducing adverse outcomes [45]. This experience underscores the potential of leveraging technology to facilitate TS to optimise provider time and reduce workloads. The importance of rapid access to essential medicines and diagnostic tools became evident during the pandemic. Zimbabwe’s approach to addressing increased testing demands by upskilling laboratory technicians, thus expanding testing availability and reducing reporting times, exemplifies the power of TS [37]. The decentralisation of diagnostic care through TS, entrusting certain responsibilities to less-qualified but systematically trained providers, can improve access, expedite diagnosis and enhance the overall resilience of the system. However, it is crucial to emphasise that such an approach must be carefully planned, well-supervised and consider rigorous regulatory checks to ensure patient safety and maintain quality of care.

One gap in the literature is the absence of economic evaluations related to TS during the pandemic. Economic assessments are essential for comprehending the cost-effectiveness of TS-based models. These not only provide stakeholders with valuable insights into the financial implications of implementing TS, but also offer a foundation for evaluating sustainability and long-term benefits of such approaches. This highlights the need for future research to focus on economic evaluations, as these are crucial for decision-making and resource allocation.

Effective stewardship and regulatory policies were pivotal in guiding healthcare practices during the pandemic. The case of German Federal and State policies on TS highlights that lack of clarity and specificity in guidelines can result in inconsistent outcomes even across the same nation [48]. In contrast, quick policy interventions and effective delegation on part of a Bornean university showcased how key TS was in preventing SARS-CoV-2 case importations and achieving zero-COVID status on campus [51]. Similarly, hospital leaderships in Indonesia recognised deficiencies in ICUs in and shifted services through quick training programs and incentivisation [46]. Policy rooted in TS through lay providers substantially improved ART uptake during the pandemic [53]. Clear unambiguous policies and proactive decision-making across all organisational levels are necessary to lead to more consistent and successful implementation of TS, ultimately improving health outcomes during pandemics.

The unintended effects of TS during the pandemic bring to light the need for comprehensive planning and strategies. While TS effectively addressed acute healthcare needs, its implementation had repercussions on other essential services. For example, the deployment of CHWs for COVID-19 surveillance in Islamabad disrupted maternal health and immunisation programs [36], highlighting the necessity of considering the broader implications of TS on systems. This underscores the importance of a nuanced approach that optimises TS’s benefits while minimising unintended consequences. Structural changes brought about by TS led to increased anxiety and depression among providers [49]. This finding emphasises the need for support systems to address the mental health and well-being of HRH during times of crisis. A balanced strategy that takes into account both the positive impacts and potential drawbacks of TS is essential for sustainable healthcare delivery.

Experiences of TS in humanitarian settings [55] and with rheumatology specialist assistants in Germany [57] illustrate how the success of TS can alter perceptions among stakeholders, particularly when confronted with workforce shortages. The shift towards more open attitudes regarding TS as a means to ensure continued access to services during times of crisis highlights its feasibility and potential acceptability. Stakeholder engagement and transparent communication about the rationale behind TS can mitigate resistance and foster acceptance. Institutionalisation of TS can prove to be a valuable long-term strategy, not limited to pandemics but also for improving care access beyond crises. This approach aligns with the need for adaptable healthcare systems capable of responding effectively to various challenges while maintaining the quality of care.

(B) The impact of pandemic on strategies used to implementing task shifting

The pandemic’s impact led to rapid adaptations in TS and digital technology emerged as a cornerstone of capacity building. Disruptions in routine activities prompted innovative delivery models. The SUMMIT [58] and PROACTIVE [59] trials exemplified the effectiveness of moving training, supervision and therapy provision to patient-centred virtual systems or telephones, leading to reduced depression and anxiety rates in patients. These findings underscore the potential of telemedicine-supported community mental health interventions in enhancing service quality and access.

The pandemic also ushered innovation in substance use and addiction treatment, demonstrating the potential of online-based capacity building to augment mental health screening and provider knowledge [62,63]. These results suggest the potential for online capacity building at the primary care level, offering efficiency and reducing infection risks, travel costs, and carbon emissions. However, challenges related to the accessibility and affordability of digital technology persist. Digital applications played a pivotal role in initiatives like the Friendship Bench [61], allowing them to reach users during lockdowns and effectively reduce depression and anxiety. However, challenges such as connectivity, expensive mobile data, and power outages need to be addressed to scale up these solutions. connectivity issues, application instability, expensive mobile data, and power outages [61].

The decentralisation of ART initiation to trained lay providers, with virtual monitoring and physician consultations, improved accessibility, particularly addressing geographical and human resource barriers [66]. The surge in telehealth utilisation and investments during the pandemic emphasises the importance of striking a balance between traditional and digital healthcare. Ensuring accreditation and quality control for digital pre-consultation tools is critical to maintain patient safety and appropriateness, especially for addressing anxiety and diverse symptoms. This highlights the need for a careful transition towards more digital healthcare solutions, maintaining a focus on quality and patient well-being. COVID-19 changed how healthcare was sought, delivered and regulated online. Telehealth utilisation increased 38 times and investments, tripled; fuelling innovation to improve access and affordability [71].

Healthcare organisations exhibited remarkable adaptability during the pandemic by modifying their standard operating procedures to implement TS effectively. These operational adjustments were vital not only for ensuring continued patient care but also for protecting their staff from potential COVID-19 transmission. The ability to flexibly embrace TS practices underscores healthcare organisations’ adaptability, particularly in the context of Human Resources for Health (HRH) shortages and financial constraints. The implementation of TS in Cameroon played a crucial role in enhancing the accessibility of Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) and helped address the HRH limitations associated with routine prescription and administration [65]. In Kenya, the introduction of One-Stop-Shop (OSS) models streamlined the delivery of PrEP but faced challenges due to pandemic-induced social distancing measures, leading to the need for increased travel between centres [67].

Moreover, healthcare organisations adapted to safeguard their HRH by expanding training in mental health support [50]. In this context, providers implemented stringent safety measures during home visits, including the use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) [64]. The Neonatal Intensive Care Units (ICUs) in Cambodia shifted responsibilities to reduce infection risks, emphasising the necessity of additional staff and training [70]. These examples not only showcase healthcare organisations’ resilience in the face of HRH constraints but also highlight the critical role of adaptability in ensuring continued healthcare services, particularly during crisis situations. While TS and procedural adaptations improved healthcare accessibility, it’s important to acknowledge that challenges emerged as the pandemic’s conditions continued to evolve. This underscores the need for continuous assessments and room for flexibility in organisational responses to address HRH limitations and maintain service quality during uncertain circumstances.

Lastly, it is extremely vital to discuss the observed variability in the terminology used to describe the phenomenon of TS from specialised to less-qualified providers. This variation hints at the potential for confusion and ambiguity, especially when researchers are attempting to synthesise new findings or when policies related to TS are under development and implementation. To address this, researchers, healthcare professionals, policy makers and other stakeholders should reach a consensus on the meanings and accepted terminology when studying and reporting on TS and task sharing, and the differences in each approach. Standardising the language used in this context can lead to clearer communication, stronger research and the development of well-informed policies in healthcare services delivery.

Limitations and implications of future research

It is important to note that the evidence on TS we have synthesised is based on published literature that originates from a limited set of nations and does not include many low-income countries. This lack of representation can result in a geographical bias. Additionally, few citations we examined lacked specific information concerning which tasks were transferred and the particular HRH involved. Future studies should strive to provide a more detailed account of these. Furthermore, future research can delve into how TS guidelines are framed, and implemented, especially in emergency contexts. This examination can help refine policies and practices, making them more effective and adaptable in crises situation. Economic evaluations of TS during pandemics are another area of significant importance. Assessing cost-effectiveness and financial implications of TS could offer valuable insights for decision-makers. Therefore, future research should also place a specific focus on this aspect.

Conclusions

In light of the ongoing global health challenges, the COVID-19 pandemic has shed light on the critical role of TS in maintaining the integrity of health services. Our review underscored the effectiveness and adaptability of TS in addressing needs during this unprecedented crisis. As the WHO acknowledged early on, the swift adoption of TS/S was imperative to respond to the mounting stresses. Our findings showcase that during the pandemic, TS was instrumental in bridging gaps in healthcare delivery across a spectrum of services, from mental health and substance use interventions to critical care in ICUs. The success stories spanning multiple countries demonstrate the versatility of TS, which ranged from reorganising roles among HRH to upskilling new providers. Such adaptability has been critical not only for addressing the immediate challenges presented by the pandemic but also for building resilience against future crises. However, it is essential to recognise that benefits of TS are often accompanied by unintended consequences, such as disruptions in non-COVID essential services and an increase in anxiety and depression among HRH. These findings emphasise the importance of comprehensive planning and mitigation of potential drawbacks when implementing TS. To harness the full potential of TS, healthcare systems must adopt a nuanced and balanced approach that maximises its benefits while minimising these side effects. In conclusion, our study reinforces the significance of TS in enhancing healthcare delivery during pandemics. It is imperative that organisations, policymakers and researchers globally acknowledge the potential of TS as a flexible dynamic approach for service delivery during emergencies. By doing so, we can not only respond more effectively to ongoing health crises but also build healthier futures.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability

All relevant data supporting the findings are within the paper and its Supporting information files.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Campbell J, Dussault G, Buchan J, Pozo-Martin F, Guerra Arias M, Leone C, et al. A universal truth: No health without a workforce. World Health Organization. 2013. [cited 14 November 2022]. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/hrh_universal_truth.

- 2.Limb M. World will lack 18 million health workers by 2030 without adequate investment, warns UN. BMJ. 2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i5169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Working together for Health: World Health Report 2006. World Health Organization. Geneva; 2006. [cited 29 November 2022]. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43432.

- 4.United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. 2022 [cited 25 Dec 2022]. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/health.

- 5.Khetrapal S, Bhatia R. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on health system & Sustainable Development Goal 3. Indian Journal of Medical Research. 2020;151(5): 395–399. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1920_20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Núñez A, Sreeganga SD, Ramaprasad A. Access to healthcare during COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(6): 2980. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18062980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Pulse survey on continuity of essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Interim report COVID-19 Essential Health Services. 2020 August 27. [cited 23 November 2022] https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/334048/WHO-2019-nCoV-EHS_continuity-survey-2020.1-eng.pdf.

- 8.World Health Organization. COVID-19 pandemic triggers 25% increase in prevalence of anxiety and depression worldwide. 2 Mar 2022. [cited 22 Decemver 2022] https://www.who.int/news/item/02-03-2022-covid-19-pandemic-triggers-25-increase-in-prevalence-of-anxiety-and-depression-worldwide.

- 9.Santomauro DF, Mantilla Herrera AM, Shadid J, Zheng P, Ashbaugh C, Pigott DM, et al. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet. 2021;398(10312): 1700–1712. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02143-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hogan AB, Jewell BL, Sherrard-Smith E, Vesga JF, Watson OJ, Whittaker C, et al. Potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria in low-income and middle-income countries: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(9): 1132–1141. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30288-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lickness J, Bachanas P, Tohme R, Russell A, Craig A, Hakim A. COVID-19 mitigation measures to maintain access to essential health services: new opportunities with long-term benefits. Pan African Medical Journal. 2021;40: 254. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2021.40.254.31264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orkin AM, Rao S, Venugopal J, Kithulegoda N, Wegier P, Ritchie SD, et al. Conceptual framework for task shifting and task sharing: an international Delphi study. Hum Resour Health. 2021;19(1): 61. doi: 10.1186/s12960-021-00605-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. Sharing and Shifting Tasks to Maintain Essential Healthcare During COVID-19 in Low Resource, non-US settings. 2022 June 17. [cited 27 November 2022]. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/non-us-settings/overview/index.html.

- 14.Lunsford S, Broughton E, Fatta K. Task shifting/sharing for HIV services in 26 PEPFAR-supported countries-a qualitative assessment. Research and Evaluation Report. USAID ASSIST Project. Chevy Chase, MD: University Research Co., LLC (URC). 2019. [cited 2 December 2022]. https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00WGCS.pdf.

- 15.Tsui S, Denison JA, Kennedy CE, Chang LW, Koole O, Torpey K, et al. Identifying models of HIV care and treatment service delivery in Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia using cluster analysis and Delphi survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1): 811. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2772-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization, PEPFAR, UNAIDS. Task Shifting: Global Recommendations and Guidelines. World Health Organization. 2008. [cited 27 October 2022]. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/ttr_taskshifting_en_0.pdf.

- 17.Gross M. Between Party, People, and Profession: The Many Faces of the “Doctor” during the Cultural Revolution. Med Hist. 2018;62(3): 333–359. doi: 10.1017/mdh.2018.23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sidel VW. Feldshers and Feldsherism. New England Journal of Medicine. 1968;278(18): 987–92. doi: 10.1056/nejm196804252781705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heller R. Ofaficiers de santé: The second-class doctors of nineteenth-century france. Med Hist. 1978;22(1): 25–43. doi: 10.1017/S0025727300031732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vaz F, Bergström S, Vaz MDL, Langa J, Bugalho A. Training medical assistants for surgery. Bull World Health Organ. 1999;77(8): 688–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mullan F, Frehywot S. Non-physician clinicians in 47 sub-Saharan African countries. Lancet. 2007;370(9605): 2158–63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60785-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zachariah R, Ford N, Philips M, Lynch S., Massaquoi M, Janssens V, et al. Task shifting in HIV/AIDS: opportunities, challenges and proposed actions for sub-Saharan Africa. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103(6): 549–58. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kola L, Kohrt BA, Hanlon C, Naslund JA, Sikander S, Balaji M, et al. COVID-19 mental health impact and responses in low-income and middle-income countries: reimagining global mental health. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(6): 535–550. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00025-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Javed A, Lee C, Zakaria H, Buenaventura RD, Cetkovich-Bakmas M, Duailibi K, et al. Reducing the stigma of mental health disorders with a focus on low- and middle-income countries. Asian J Psychiatr. 2021;58: 102601. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Y, Lange K. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and global mental health. Global Health Journal. 2021;5(1): 31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.glohj.2021.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mobula LM, Heller DJ, Commodore-Mensah Y, Walker Harris V, Cooper LA. Protecting the vulnerable during COVID-19: Treating and preventing chronic disease disparities. Gates Open Res. 2020;4: 125. doi: 10.12688/gatesopenres.13181.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson SA, Kaggwa MN, Lathrop EVA. How It Started, and How It’s Going: Global Family Planning Programs. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2021;64(3): 422–434. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steben M, Norris T, Rosberger Z, HPV Global Action. COVID-19 Won’t Be the Last (Or Worst) Pandemic: It’s Time to Build Resilience Into Our Cervical Cancer Elimination Goals. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 2020;42(10): 1195–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2020.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Health Organization. Everybody’s business: strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes: WHO’s framework for action. Production. 2007. [cited 2 December 2022]. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/43918/9789241596077_eng.pdf.

- 30.Shoman H, Karafillakis E, Rawaf S. The link between the West African Ebola outbreak and health systems in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone: a systematic review. Global Health. 2017;13(1): 1. doi: 10.1186/s12992-016-0224-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence systematic review software. Melbourne Australia. Melbourne, Australia; www.covidence.org.

- 32.Khalil H, Tricco AC. Differentiating between mapping reviews and scoping reviews in the evidence synthesis ecosystem. J Clin Epidemiol. 2022;149: 175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2022.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7): 467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3: 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu W, Zammit K. Applying Thematic Analysis to Education: A Hybrid Approach to Interpreting Data in Practitioner Research. Int J Qual Methods. 2020;19: 1–9. doi: 10.1177/1609406920918810 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zafar S, Fruchtman CS, Bilal Khalid M, Zia Z, Khalid Khan F, Iqbal S, et al. Lessons learnt of the COVID-19 contact tracing strategy in Islamabad Capital Territory, Pakistan using systems thinking processes. Front Public Health. 2022;13(10). doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.909931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gudza-Mugabe M, Sithole K, Sisya L, Zimuto S, Charimari LS, Chimusoro A, et al. Zimbabwe’s emergency response to COVID-19: Enhancing access and accelerating COVID-19 testing as the first line of defence against the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health. 2022;10. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.871567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Honda C, Sumikawa Y, Yoshioka-Maeda K, Iwasaki-Motegi R, Yamamoto- Mitani N. Confusions and responses of managerial public health nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. Public Health Nurs. 2022;39(1): 161–169. doi: 10.1111/phn.13011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chidavaenzi NZ, Agathis N, Lees Y, Stevens H, Clark J, Reede D, et al. Implementation of a COVID-19 Screening Testing Program in a Rural, Tribal Nation: Experience of the San Carlos Apache Tribe, January–February 2021. Public Health Reports. 2022;137(2): 220–225. doi: 10.1177/00333549211061770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raskin SE, Diep VK, Chung-Bridges K, Heaton LJ, Frantsve-Hawley J. Dental safety net providers’ experiences with service delivery during the first year of COVID-19 should inform dental pandemic preparedness. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2022;153(6): 521–531. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2021.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mohammed A, Mohammed A, Mohammed IU, Danimoh MA, Laima CH. Risk Perception and Willingness of Medical Students in North East Nigeria to Participate in Mitigating COVID 19 Pandemic. J Adv Med Med Res. 2020;32: 107–114. doi: 10.9734/jammr/2020/v32i730456 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taylor MK, Kinder K, George J, Bazemore A, Mannie C, Phillips R, et al. Multinational primary health care experiences from the initial wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative analysis. SSM Qual Res Health. 2022;2. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmqr.2022.100041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eggleton K, Bui N, Goodyear-Smith F. Disruption to the doctor–patient relationship in primary care: a qualitative study. BJGP Open. 2022;6(4). doi: 10.3399/BJGPO.2022.0039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yoshioka-Maeda K, Sumikawa Y, Tanaka N, Honda C, Iwasaki-Motegi R, Yamamoto-Mitani N. Content analysis of the free covid-19 telephone consultations available during the first wave of the pandemic in japan. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9(11): 1593. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9111593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoshioka-Maeda K. Developing sustainable public health care systems for responding to COVID-19 in Japan. Public Health Nurs. 2021;38: 470–472. doi: 10.1111/phn.12861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Helmi M, Sari D, Meliala A, Trisnantoro L. What is preparedness and capacity of intensive care service in Indonesia to response to covid-19? A mixed-method study. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2021;9: 1686–1694. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2021.7626 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sono-Setati ME, Mphekgwana PM, Mabila LN, Mbombi MO, Muthelo L, Matlala SF, et al. Health System- and Patient-Related Factors Associated with COVID-19 Mortality among Hospitalized Patients in Limpopo Province of South Africa’s Public Hospitals. Healthcare (Basel). 2022;10(7): 1338. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10071338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Köppen J, Hartl K, Maier CB. Health workforce response to Covid-19: What pandemic preparedness planning and action at the federal and state levels in Germany?: Germany’s health workforce responses to Covid-19. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2021;36(S1): 71–91. doi: 10.1002/hpm.3146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Faria de Moura Villela E, Rodrigues da Cunha I, Nelson Siewe Fodjo J, Obimpeh M, Colebunders R, Van Hees S. Impact of covid-19 on healthcare workers in brazil between august and november 2020: A cross-sectional survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(12). doi: 10.3390/ijerph18126511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ortega AC, Valtierra E, Rodríguez-Cuevas FG, Aranda Z, Preciado G, Mohar S. Protecting vulnerable communities and health professionals from COVID-19 associated mental health distress: a comprehensive approach led by a public-civil partnership in rural Chiapas, Mexico. Glob Health Action. 2021;14(1). doi: 10.1080/16549716.2021.1997410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mukhsam MH, Jeffree MS, Tze Ping Pang N, Syed Abdul Rahim SS, Omar A, Abdullah MS, et al. A university-wide preparedness effort in the alert phase of COVID-19 incorporating community mental health and task-shifting strategies: Experience from a bornean institute of higher learning. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103(3): 1201–1203. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Omam LA, Jarman E, Ekokobe W, Evon A, Omam EN. Mobile clinics in conflict-affected communities of North West and South West regions of Cameroon: an alternative option for differentiated delivery service for internally displaced persons during COVID-19. Confl Health. 2021;15(1): 90. doi: 10.1186/s13031-021-00427-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pry JM, Sikombe K, Mody A, Iyer S, Mutale J, Vlahakis N, et al. Mitigating the effects of COVID-19 on HIV treatment and care in Lusaka, Zambia: A before-after cohort study using mixed effects regression. BMJ Glob Health. 2022;7(1). doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-007312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Abraham SA, Berchie GO, Doe PF, Agyare E, Addo SA, Obiri-Yeboah D. Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on ART Service delivery: perspectives of healthcare workers in a Teaching Hospital in Ghana. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1): 1295. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-07330-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jacobi L, Rich S. Covid-19’s Effects on Contraceptive Services Across the Humanitarian–Development Nexus. Institute of Development Studies Bulletin. 2022;53(2). doi: 10.19088/1968-2022.120 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Davis C, Ng KC, Oh JY, Baeg A, Rajasegaran K, Chew CSE. Caring for Children and Adolescents With Eating Disorders in the Current Coronavirus 19 Pandemic: A Singapore Perspective. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2020;67(1): 131–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.03.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kuhlmann E, Bruns L, Hoeper K, Richter M, Witte T, Ernst D, et al. Work situation of rheumatologists and residents in times of COVID-19: Findings from a survey in Germany. Z Rheumatol. 2021;82(4): 331–341. doi: 10.1007/s00393-021-01081-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Singla DR, Meltzer-Brody SE, Silver RK, Vigod SN, Kim JJ, La Porte LM, et al. Scaling Up Maternal Mental healthcare by Increasing access to Treatment (SUMMIT) through non-specialist providers and telemedicine: a study protocol for a non-inferiority randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2021;22(1): 186. doi: 10.1186/s13063-021-05075-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Scazufca M, Nakamura CA, Seward N, Moreno-Agostino D, van de Ven P, Hollingworth W, et al. A task-shared, collaborative care psychosocial intervention for improving depressive symptomatology among older adults in a socioeconomically deprived area of Brazil (PROACTIVE): a pragmatic, two-arm, parallel-group, cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2022;3(10): 690–702. doi: 10.1016/S2666-7568(22)00194-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jordans MJD, Steen F, Koppenol-Gonzalez G V., El Masri R, Coetzee AR, Chamate S, et al. Evaluation of competency-driven training for facilitators delivering a psychological intervention for children in Lebanon: a proof-of-concept study. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2022;31: 48. doi: 10.1017/S2045796022000348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dambi J, Norman C, Doukani A, Potgieter S, Turner J, Musesengwa R, et al. A Digital Mental Health Intervention (Inuka) for Common Mental Health Disorders in Zimbabwean Adults in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic: Feasibility and Acceptability Pilot Study. JMIR Ment Health. 2022;9(10). doi: 10.2196/37968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nirisha PL, Malathesh BC, Kulal N, Harshithaa NR, Ibrahim FA, Suhas S, et al. Impact of Technology Driven Mental Health Task-shifting for Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs): Results from a Randomised Controlled Trial of Two Methods of Training. Community Ment Health J. 2022;59(1): 175–184. doi: 10.1007/s10597-022-00996-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Philip S, Patley R, Chander R, Varshney P, Dosajh AC, Vinay B, et al. A report on successful introduction of tele mental health training for primary care doctors during the COVID 19 pandemic. Asian J Psychiatr. 2022;68. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rodriguez-Cuevas F, Valtierra-Gutiérrez E, Roblero-Castro J, Guzmán-Roblero C. Living Six Hours Away from Mental Health Specialists: Enabling Access to Psychosocial Mental Health Services through the Implementation of Problem Management plus Delivered by Community Health Workers in Rural Chiapas, Mexico. Intervention. 2021;19(1): 75–83. doi: 10.4103/intv.intv_28_20 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Coulaud P, Sow A, Sagaon-Teyssier L, Ndiaye K, Maradan G, Laurent C, et al. Individual and healthcare supply-related HIV transmission factors in HIV-positive patients enrolled in the antiretroviral treatment access program in the Centre and Littoral regions in Cameroon (ANRS-12288 EVOLCam survey). PLoS One. 2022;17(4). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0266451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lujintanon S, Amatavete S, Thitipatarakorn S, Puthanakit T, Songtaweesin WN, Chaisalee T, et al. Key population-led community-based same-day antiretroviral therapy (CB-SDART) initiation hub in Bangkok, Thailand: a protocol for a hybrid type 3 implementation trial. Implement Sci Commun. 2022;3(1): 101. doi: 10.1186/s43058-022-00352-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Roche SD, Odoyo J, Irungu E, Kwach B, Dollah A, Nyerere B, et al. A one-stop shop model for improved efficiency of pre-exposure prophylaxis delivery in public clinics in western Kenya: a mixed methods implementation science study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2021;24(12). doi: 10.1002/jia2.25845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kamvura TT, Turner J, Chiriseri E, Dambi J, Verhey R, Chibanda D. Using a theory of change to develop an integrated intervention for depression, diabetes and hypertension in Zimbabwe: lessons from the Friendship Bench project. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06957-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Oikonomidi T, Ravaud P, Barger D, Tran VT. Preferences for Alternative Care Modalities among French Adults with Chronic Illness. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(12). doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.41233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Iwamoto A, Tung R, Ota T, Hosokawa S, Matsui M. Challenges to neonatal care in Cambodia amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Glob Health Med. 2020;2. doi: 10.35772/ghm.2020.01030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bestsennyy O, Gilbert G, Harris A, Rost J. Telehealth: A quarter-trillion-dollar post-COVID-19 reality? Healthcare Systems & Services. 2021 July 9. [cited 30 Dec 2022]. https://connectwithcare.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/telehealth-a-quarter-trillion-dollar-post-covid-19-reality.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data supporting the findings are within the paper and its Supporting information files.