Abstract

ςE is a mother cell-specific transcription factor of sporulating Bacillus subtilis that is derived from an inactive precursor protein (pro-ςE). To examine the process that prevents ςE activity from developing in the forespore, we fused the ςE structural gene (sigE) to forespore-specific promoters (PdacF and PspoIIIG), placed these fusions at sites on the B. subtilis chromosome which translocate into the forespore either early or late, and used Western blot analysis to monitor SigE accumulation and pro-ςE processing. sigE alleles, placed at sites which entered the forespore early, were found to generate more protein product than the same fusion placed at a late entering site. SigE accumulation and processing in the forespore were enhanced by null mutations in spoIIIE, a gene whose product is essential for translocation of the distal portion of the B. subtilis chromosome into the forespore. In other experiments, a chimera of pro-ςE and green fluorescence protein, previously shown to be unprocessed if it is synthesized within the forespore, was found to be processed in this compartment if coexpressed with the gene for the pro-ςE-processing enzyme, SpoIIGA. The need for spoIIGA coexpression is obviated in the absence of SpoIIIE. We interpret these results as evidence that selective degradation of both SigE and SpoIIGA prevent mature ςE from accumulating in the forespore compartment of wild-type B. subtilis. Presumably, a gene(s) located at a site that is distal to the origin of chromosome transfer is responsible for this phenomenon when it is translocated and expressed in the forespore.

Early in the process of endospore formation, Bacillus subtilis partitions itself into two unequal compartments with dissimilar developmental fates. The smaller compartment ultimately becomes the spore, while the larger compartment assumes the role of mother cell, engulfing and nurturing the developing forespore and then lysing when the spore matures. Developmental gene expression is unique to each of the two compartments and is dictated by novel sigma (ς) factors which become active only in one or the other compartment (reviewed in reference 39). ςE is the first of the alternative sigma factors to appear in the mother cell, with ςF as its counterpart in the forespore (9, 13, 16, 27, 28, 40). Both ςE and ςF are synthesized at the onset of sporulation, but neither is active until 1.5 to 2 h later, when the forespore septum establishes the separate mother cell and forespore (9, 13, 21, 22, 27, 28, 41, 44, 45). Each of these sigma factors is kept silent by unique means. ςF is bound to an anti-ςF protein (SpoIIAB) which blocks its activity, while ςE is formed as a pro-protein (pro-ςE) which becomes active only after 27 amino acids are cleaved from its amino terminus (1, 7, 8, 11, 12, 19, 22, 25, 30, 31, 36–38).

ςF is freed from SpoIIAB by the action of a second protein (SpoIIAA), which triggers ςF release by binding to SpoIIAB (1, 8, 11). SpoIIAB is a SpoIIAA-specific kinase, as well as a binding protein (1, 30). Phosphorylated SpoIIAA is ineffective in driving the release of ςF (10, 11). Before compartmentalization, most of the SpoIIAA is phosphorylated and inactive. SpoIIAA-P is reactivated by a phosphatase (SpoIIE) that becomes bound to the sporulation septum (2–4, 10). It has been speculated that the septal location of the phosphatase might establish a higher phosphatase-to-kinase ratio in the small forespore compartment than in the large mother cell and that this could drive selective ςF activation in the forespore (10).

Activation of pro-ςE requires a sporulation-specific protease (SpoIIGA) that is coexpressed with pro-ςE at the onset of sporulation (18, 33, 38). Although both the protease and substrate are present in the predivisional cell, the processing reaction does not occur until a specific signal protein (SpoIIR) triggers the reaction (20, 26). SpoIIR is produced in the forespore under the control of ςF (20, 26). It is believed that SpoIIGA is an integral membrane protein that accumulates at the forespore septum membrane. At this site, SpoIIGA is positioned to interact with SpoIIR, which is being secreted by the forespore (15, 19). Thus, the activation of ςE, as well as ςF, is tied to the formation of the forespore septum. This dependence on septation explains the timing of ςF and ςE activation but leaves the question of compartment-specific ςE activation unresolved. Both pro-ςE and SpoIIGA, having been synthesized before the sporulation cell division, should be present in both compartments. An intriguing hypothesis is that there is a directionality to SpoIIGA activation by SpoIIR and that only the mother cell’s SpoIIGA is positioned in the septal membrane in an orientation appropriate to receive the SpoIIR signal (15). Although this mechanism is possible, other factors are likely to also be involved. Vegetative B. subtilis, expressing spoIIR from a gratuitous promoter, can process pro-ςE if SpoIIGA is present (26). Thus, although transseptal signaling likely occurs, it does not appear to be essential for processing. In addition, a strain of B. subtilis in which spoIIR was expressed prior to septation still acquired mother cell-specific ςE activity (48). Apparently, a device other than the forespore-specific expression of spoIIR plays a role in establishing the mother cell-specific activity of ςE. Using a chimera of a portion of pro-ςE fused to green fluorescent protein (GFP) as a probe of the processing reaction, we had found that pro-ςE::GFP could be processed following septation if it was synthesized in the predivisional cell but not if it was expressed from a forespore-specific promoter (e.g., PdacF) (19). This suggested that the pro-ςE processing reaction is limited to the mother cell, although the reason for this restriction remained obscure. Recently, Pogliano et al. used fluorescence microscopy to show that pro-ςE and ςE are absent from the forespore and that their disappearance requires functional SpoIIIE (35). SpoIIIE is known to be essential for the translocation of the distal 70% of the bacterial chromosome into the forespore (46). In the present study, we examined this phenomenon in greater detail and revisited the question of the mother cell-specific processing of pro-ςE. We found that the ability of SigE to accumulate, when expressed from a forespore-specific promoter, is dependent on the site of sigE expression on the B. subtilis chromosome and the state of SpoIIIE. PdacF-sigE is more likely to generate a product which can accumulate and be processed into ςE if it is expressed from a locus on the chromosome that is translocated to the forespore early (e.g., amyE or ctc) than if it lies at a late entering site (e.g., dacF). The absence of SpoIIIE further enhances this accumulation and processing. We also determined that a pro-ςE::GFP hybrid protein, which had been previously shown to be unprocessed if expressed in the forespore, is processed in that compartment if it is either coexpressed with its processing enzyme (SpoIIGA) or synthesized in a strain which lacks SpoIIIE. Our data are consistent with the notion that a forespore-specific factor, likely a proteolytic activity encoded by a segment of the Bacillus chromosome which enters the forespore late, blocks the formation of active ςE in the forespore by removing both pro-ςE/ςE and SpoIIGA from that compartment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The B. subtilis strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. The transcriptional fusions of the spoIIIG and dacF promoters to sigE or sigE335 were constructed in two stages. A 0.43-kbp HindIII/PstI fragment from pGSIIG11 (41), containing the spoIIIG promoter, or a 0.42-bp HindIII fragment from pPP212 (37), containing the dacF promoter, were cloned into pUS19 (5) that had been cut with either HindIII or HindIII/PstI, as appropriate. The promoters were oriented toward the unique PstI site in the vector. A PstI fragment of approximately 1.1 kbp, containing sigE or sigE335 (32), was cloned into this PstI site, downstream of each of the two promoters. The resulting clones were analyzed by restriction endonuclease digestions to verify proper orientation of sigE relative to the promoters. This procedure yields plasmids pFE335, pGE335, pFE-1, and pGE1 (Table 1). A DNA fragment containing spoIIGA, with SalI and EcoRI sites bracketing it, was generated by PCR techniques and cloned in the SalI/EcoRI site downstream site of the dacF promoter. This yielded plasmid pFIIGA.

TABLE 1.

B. subtilis strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype or features | Source, construction, or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| SMY | trpC | Laboratory strain |

| RL1059 | spoIIIE::spc | 35 |

| SL4834 | trpC2 metC erm amyE::dacF-lacZ | 37 |

| SEK84 | kan/sigEΔ84 | Laboratory strain |

| SEK8401 | sigEΔ84 spoIIIE::spc | RL1059→SEK84 |

| SL4342 | spoIIIGΔ1 trpC phe-1 erm Pspac-spoIIAC | 37 |

| SFE1 | sigE PdacF-sigE335 | pFE335→SMY |

| SFE2 | sigE PdacF-sigE335 Pspac-spoIIAC | SL4342→SFE1 |

| SFE3 | sigE PdacF-sigE55-lacZ | pFEL-1→SMY |

| SFE4 | sigE PdacF-sigE55-lacZ Pspac-spoIIAC | SL4342→SFE3 |

| SFE5 | amyE::PdacF-sigE335 | pFE335→SL4834 |

| SFE6 | amyE::PdacF-sigE335 cat | pJM102→SFE5 |

| SFE7 | sigE PdacF-sigE | pFE1→SMY |

| SFE8 | amyE-PdacF-sigE | pSFE1→SL4834 |

| SFE9 | PdacF-sigE cat | pJM102→SFE7 |

| SFE10 | sigEΔ84 amyE::PdacF-sigE335 | SEK84→SFE5 |

| SFE11 | sigEΔ84 amyE::PdacF-sigE335 spoIIIE::spc | SFE5→SEK8401 |

| SFE12 | sigEΔ84 PdacF-sigE335 | SEK84→SFE1 |

| SFE13 | sigEΔ84 amyE::PdacF-sigE335 spoIIIE::spc | SFE6→SEK8401 |

| SFE14 | sigEΔ84 amyE::PdacF-sigE | SEK84→SFE8 |

| SFE15 | sigEΔ84 amyE::PdacF-sigE spoIIIE::spc | SFE8→SEK8401 |

| SFE16 | sigEΔ84 PdacF-sigE | SEK84→SFE7 |

| SFE17 | sigEΔ84 PdacF-sigE spoIIIE::spc | SFE9→SEK8401 |

| SFG1 | PdacF-sigE55-gfp | pF1→SMY |

| SFG2 | PdacF-sigE55-gfp PdacF-spoIIGA | pFIIGA→SFG1 |

| SFG3 | sigEΔ84 PdacF-sigE55-gfp spoIIIE::spc | SFG1→SEK8401 |

| SFG4 | ctc::PdacF-sigE55-gfp | pF1→SC191 |

| SFG5 | ctc::PdacF-sigE55-gfp::PdacF-spoIIGA | pFIIGA→SFG4 |

| SFG6 | sigEΔ84 ctc::PdacF-sigE55-gfp spoIIIE::spc | SFG4→SEK8401 |

| SC191 | ctc::pUK191 | pUK191→SMY |

| SGE1 | sigE PspoIIIG-sigE355 | pGE335→SMY |

| SGE2 | sigE PspoIIIG-sigE355 Pspac-spoIIAC | SL4342→SGE1 |

| SGE3 | sigE PspoIIIG-sigE-lacZ | pGEL-1→SMY |

| SGE4 | sigE PspoIIIG-sigE-lacZ Pspac-spoIIAC | SL4342→SGE3 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUS19 | bla spc | 5 |

| pUK19 | bla kan | This study |

| pPP212 | bla dacF | 45 |

| pFE335 | bla spc PdacF-sigE335 | This study |

| pGE335 | bla spc PIIIG-sigE335 | This study |

| pFE-1 | bla spc PdacF-sigE | This study |

| pGE-1 | bla spc PIIIG-sigE | This study |

| pF1 | bla cat PdacF-sigE55-gfp | 19 |

| pCT050 | cat ctc | 42 |

| pUK191 | bla kan ctc | This study |

| pFEL-1 | bla spc PdacF-sigE-lacZ | This study |

| pGEL-1 | bla spc PIIIG-sigE-lacZ | This study |

| pGSIIG11 | bla cat spoIIGB spoIIIG | 41 |

| pEL-1 | bla cat sigE-lacZ | 17 |

| pFIIGA | bla spc PdacF-spoIIGA | This study |

pEL-1 encodes a composite protein with the first 55 amino acids of pro-ςE fused to LacZ (17). Transcriptional fusions of the spoIIIG and dacF promoters to sigE-lacZ were constructed by joining the HindIII or HindIII-PstI promoter pieces that were used in constructing the fusions of these promoters to sigE to HindIII or HindIII-PstI-cut pEL-1. This procedure yields plasmid pGEL-1 (PspoIIIG) and pFEL-1 (PdacF).

PUK19 was constructed by cloning a 1.5-kbp ClaI fragment carrying a gene encoding kanamycin resistance (aph3′5") from pJH1 (23) into ClaI-cut pUC19. pUK191 is a 0.9-kbp EcoRI fragment from pCT050 (42) containing the ctc gene cloned into the EcoRI site of pUK19. pF1 contains a sigE55-gfp in-frame fusion under the control of the dacF promoter. An inducible source of ςF (Pspac-spoIIAC) was introduced into strains by transformation with chromosomal DNA from SL4342 (37) and selection for the linked Erm marker. Strains containing dacF promoter fusions at amyE or ctc were constructed by transforming the fusion plasmids into strains (SC191 and SL4834) with related plasmids already integrated at these sites. Clones in which the dacF fusions had integrated at the amyE or ctc locus were identified by cotransformation of the antibiotic resistances of the dacF and resident plasmids.

Visualization of fluorescence.

Fluorescence was visualized as described previously (4, 19, 24, 43). Culture samples of 200 μl were transferred to 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes on ice, 50 μl of preservation buffer (40 mM NaN3, 50% sucrose, 0.5 M Tris [pH 7.45], 0.77 M NaCl) was added, and the suspension was incubated at 4°C for at least 2 h. A 3-μl aliquot of the cell suspension was mixed with 1 μl of 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, 1 μg/ml; Sigma) on a slide precoated with 0.01% polylysine (Sigma) and covered with a polylysine-coated coverslip. Cells were viewed with a Zeiss Axiophot epifluorescence microscope with a 100-W mercury lamp source and a 100× Plan-Neofluar oil immersion objective lens. Images were recorded on Kodak TMZ p3200 professional film. The images were scanned and prepared with Adobe Photoshop version 4.0.

Images of the same field were obtained under conditions for recording fluorescence of GFP, phase-contrast micrographs, and DAPI staining. The camera was set at the automatic mode for all pictures. GFP fluorescence was viewed with a fluorescein isothiocyanate filter set (Chroma Technology; 450-490 exciter filter, FT510 chromatic beam splitter, and LP520 barrier filter). DAPI-stained images were obtained with a fluorescein isothiocyanate filter set (Chroma Technology; BP 365/12 exciter filter, FT395 chromatic beam splitter, and LP397 barrier filter).

Western blot analysis.

Crude cell extracts were prepared from B. subtilis by disrupting bacteria with a French pressure cell. The protein concentration was determined by a Bio-Rad protein assay in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Extracts were fractionated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis with 12% acrylamide. Subsequent steps were as described previously (41), using either locally prepared anti-ςE monoclonal antibody or commercial anti-GFP monoclonal antibody (Clontech Laboratories, Inc., Palo Alto, Calif.) as the probe. The commercial antibody cross-reacted with several proteins in the crude extracts. These were variable with each antibody lot and were identified by comparing the experimental extracts with similar extracts from cells without the fusion. Bound antibody was visualized with an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat immunoglobulin against mouse immunoglobulin (American Qualex) by using either an alkaline phosphate substrate kit (Bio-Rad) or CDP-Star (Boehringer Mannheim) as the substrate reagent.

β-Galactosidase assays.

Cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in Z buffer (29), and disrupted by passage through a French pressure cell. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation (10,000 × g) for 10 min, and the supernatant was analyzed for β-galactosidase by using the reagents described by Miller (29). Protein concentrations were determined by a Bio-Rad assay using the procedures recommended by the manufacturer. β-Galactosidase activity was expressed as ΔA420 × 1,000 × min−1 × mg of protein−1.

General methods.

DNA manipulation and the transformation of Escherichia coli were done in accordance with standard protocols. Transformation of competent B. subtilis cells was carried out by the method of Yasbin et al. (47).

RESULTS

Expression of sigE335 from forespore-specific promoters.

The product of the sigE335 allele lacks 15 amino acids in the pro-ςE amino terminus (32). It is not recognized for processing into mature ςE, but it is at least partially active without processing (32). The smaller size of ςE335 and its failure to be converted into ςE allow it to be distinguished from the wild-type sigE products in Western blot analyses. To investigate whether there are factors in the forespore that influence ςE accumulation or activity in this compartment, we joined sigE335 to promoters (PdacF and PspoIIIG) whose transcription depends on the forespore-specific ς factor ςF (37, 40). When PdacF-sigE335 or PspoIIIG-sigE335 is transferred on integrative plasmids into Bacillus, it can recombine into the chromosomal sites of the promoter sequences (i.e., dacF and spoIIIG). This results in a duplication of the promoters, with one promoter driving sigE335 and the second driving its normal operon. Integration is also possible at the sigE sequences. At this site, most integration events would exchange sigE335 for sigE as the allele that is expressed from the normal sigE promoter (PspoIIG) (41). Cells which carry ςE335 as their principal source of ςE are Spo− (32). Approximately 20% of the transformants that received either of the sigE335 plasmids were Spo−. Western blot analysis of the sigE proteins in extracts from representative Spo− clones revealed only ςE335, with its synthesis beginning when PspoIIG becomes active at the onset of sporulation (data not shown). These Spo− clones likely represent transformants in which the plasmid integrated within sigE to place sigE335 downstream of PspoIIG. When the Spo+ transformants were analyzed for their sigE products, pro-ςE and ςE were readily observed, but no ςE335 could be detected in the strains transformed with either PdacF-sigE335 (Fig. 1A) or PspoIIIG-sigE335 (Fig. 1C). To verify that the putative PdacF-sigE335- and PspoIIIG-sigE335-containing strains were properly configured to express sigE335 in response to ςF activation, we transformed an inducible source of ςF (i.e., Pspac-spoIIAC) into these strains and examined the effects of ςF synthesis on ςE335 accumulation during vegetative growth. As shown in Fig. 1B and D, both the PdacF-sigE335- and PspoIIIG-sigE335-containing strains accumulated ςE335 in response to ςF induction.

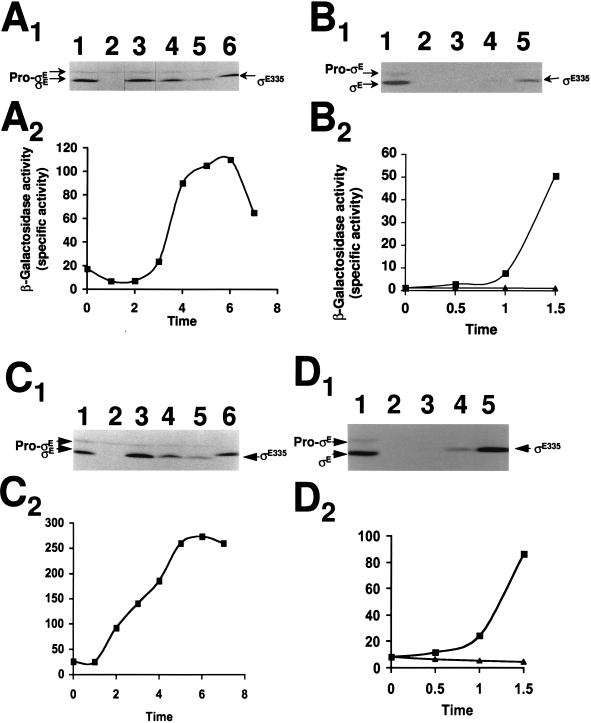

FIG. 1.

Accumulation of ςE335 and SigE55-LacZ in B. subtilis strains. (A1 and C1) Western blot analysis of B. subtilis SFE1 (PdacF-sigE335) and SGE1 (PspoIIIG-sigE335), respectively. Cells were grown in DS medium with samples taken at 1 (lanes 2), 3 (lanes 3), 5 (lanes 4), and 7 (lanes 5) h after the onset of sporulation. Lanes 1 and 6 contain control extracts from wild-type B. subtilis (SMY) and strain SE335 at t3 of sporulation, respectively. Each lane contained 100 μg of extract which was analyzed for SigE-like proteins by Western blotting as described in Materials and Methods. The positions at pro-ςE, ςE335, and ςE are indicated. (A2 and C2) β-Galactosidase levels in B. subtilis SFE3 (PdacF-sigE55-lacZ) and SGE3 (PspoIIIG-sigE55-lacZ). Cells were grown in DS medium, and samples were taken at the indicated times after the onset of sporulation and analyzed for β-galactosidase activity as described in Materials and Methods. β-Galactosidase units are expressed as ΔA420 × 1,000 × min−1 × mg of protein−1. (B1 and D1) Western blot analysis of strain SFE2 (PdacF-sigE335 PSPAC-spoIIAC) and SGE2 (PspoIIIG-sigE335 PSPAC-spoIIAC), respectively. Cells were grown in LB medium and exposed to isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG; 1 mM) to induce ςF synthesis. Samples were taken at the time of IPTG addition (lanes 2) and 0.5 (lanes 3), 1 (lanes 4), and 1.5 (lanes 5) h thereafter and analyzed by Western blotting. Lanes 1 contain strain SMY at t3. The positions of pro-ςE, ςE335, and ςE are indicated. (B2 and D2) β-Galactosidase levels in strain SFE4 (PdacF-sigE55-lacZ PSPAC-spoIIAC) and SGE4 (PspoIIIG-sigE55-lacZ PSPAC-spoIIAC), respectively. Cells, grown in LB medium, were exposed to 1 mM IPTG (▪) or were allowed to continue to grow in its absence (▴). Samples were taken at the time of IPTG addition and at 0.5-h intervals thereafter and were analyzed for β-galactosidase activity as described above.

Our ability to detect ςE335 from PdacF-sigE335 and PspoIIIG-sig335 following ςF synthesis in vegetatively growing B. subtilis, but not during sporulation, suggests either that we are inducing ςF-dependent transcription more effectively in our artificial system or that there are additional factors in the sporulating cells that inhibit ςE335 accumulation. To test the relative activities of the dacF and spoIIIG promoters under our two conditions, we replaced the sigE335 alleles in our constructions with a chimeric sigE55-lacZ gene. The resulting PdacF-sigE55-lacZ and PspoIIIG-sigE55-lacZ genes have the ςF-dependent promoters of the previous constructions along with the sigE translational regulatory elements and approximately 50 codons from the amino terminus of sigE but express a β-galactosidase-like protein as their product. When these constructions were transformed into B. subtilis, the resulting clones displayed appreciable sporulation-specific β-galactosidase synthesis (Fig. 1A2 and C2). We then transformed PSPAC-spoIIAC into these strains and examined the levels of β-galactosidase following ςF synthesis during vegetative growth. A comparison of the β-galactosidase levels formed under this circumstance with that observed in sporulating cultures should reflect the relative activities of the dacF and spoIIIG promoters under these two conditions. We found that the β-galactosidase levels of the vegetatively induced cultures were less than half of those seen when the parent strains were allowed to sporulate (compare Fig. 1B2 and D2 with Fig. 1A2 and C2). Thus, based on the relative levels of β-galactosidase that are seen under the artificial and natural inducing conditions, we would have expected to see twice as much ςE335 in the PdacF-sigE335 and PspoIIIG-sigE335 strains during sporulation as was present following the vegetative inductions. The absence of ςE335 in the sporulating cultures argues that there are additional factors that restrict ςE335 accumulation within the forespore compartment at the time when the dacF promoter becomes active. Given that sigE-lacZ and sigE335 have common transcriptional and translational regulatory elements, selective turnover of ςE335 in the forespore becomes a plausible possibility for its failure to accumulate.

Expression of sigE alleles from the amyE locus in wild-type and spoIIIE mutant strains.

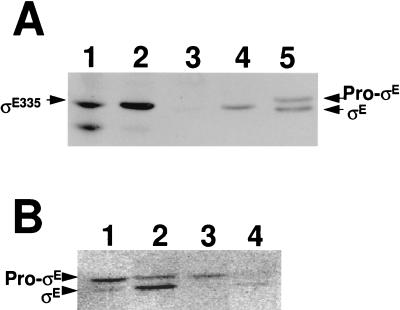

It has been reported that pro-ςE/ςE can persist in the forespore compartment of cells with mutations at spoIIIE (35). SpoIIIE is an essential sporulation protein that is needed for the translocation of the forespore’s chromosome into that compartment (46). In the absence of SpoIIIE, only the first 20 to 30% of the chromosome enters the forespore (46). For a ςF-dependent gene to be effectively expressed in a spoIIIE mutant, it must be at a site on the chromosome that enters the forespore. We wished to investigate the effects of the loss of SpoIIIE on our ability to synthesize ςE335 in the forespore; however, neither the dacF nor spoIIIG locus enters the forespore in a spoIIIE mutant strain. We therefore transferred the PdacF-sigE335 fusion to a site (amyE) that does enter the forespore in a spoIIIE mutant background. The strain we used in our analysis had an additional mutation (sigEΔ84) which eliminates the synthesis of pro-ςE/ςE from its normal locus (spoIIG) (17, 32). In this strain, the product of the amyE::PdacF-sigE fusion is the cell’s sole source of SigE and the only protein that will react with our anti-ςE antibody in Western blots. Prior to investigating the effect of a loss of spoIIIE on ςE335 accumulation, we examined the expression of sigE335 at amyE in a strain with a wild-type spoIIIE allele. Surprisingly, sigE335 expressed from PdacF at the amyE locus, unlike sigE335 expressed from this same promoter at dacF, could be detected in Western blots (Fig. 2A, lane 1). Although ςE335 was evident, an abundant higher-mobility band was also detected by the anti-ςE antibody. We interpret this secondary material to be a ςE335 breakdown product. Our ability to now detect ςE335 from a forespore-expressed promoter is not due to the absence of wild-type sigE in this strain but rather to the expression of sigE335 from the amyE locus. A strain with PdacF-sigE335 at dacF and the sigEΔ84 allele at spoIIG still fails to accumulate ςE335 (Fig. 2A, lane 3). Apparently, ςE335 can accumulate to detectable levels in the forespore if it is expressed from a site on the B. subtilis chromosome that translocates to the forespore early (i.e., amyE) but not if it is expressed from a late entering site (i.e., dacF or spoIIIG). We next examined the accumulation of ςE335 in strains with null mutations in spoIIIE. sigE335 expressed from PdacF at amyE in a spoIIIE mutant strain generated ςE335; however, unlike the SpoIIIE+ strain, the putative breakdown product was minimal (Fig. 2A, lane 2). The presence of likely ςE335 breakdown products in the wild-type but not the spoIIIE mutant strain suggests that ςE335 is more stable in the absence of SpoIIIE. This would be consistent with the finding of Pogliano et al. that SpoIIIE facilitates the disappearance of pro-ςE/ςE from the forespore (35). Although the dacF locus does not translocate to the forespore in the absence of SpoIIIE, the PdacF-sigE335 fusion, positioned at dacF in the sigEΔ84 spoIIIE mutant strain, expressed a small amount of ςE335 (Fig. 2A, lane 4). Presumably, the small amount of ςE335 found in this strain is a consequence of ςF activation in the mother cell compartment. ςF has been reported to become partially active in the mother cell compartment in a SpoIIIE mutant background (35, 44) and possibly more active if ςE is also absent (35).

FIG. 2.

Western blot analysis of PdacF-sigE335 (A) and PdacF-sigE (B) in sporulating B. subtilis. Cells were grown in DS medium and harvested at 4 h after the onset of sporulation. Development of the blots was normalized to a control sample included in the analysis. One hundred micrograms of extract was analyzed for each lane except for lane 5 in panel A, which contains 15 μg of protein from strain SMY at t3. The positions of pro-ςE, ςE335, and ςE are indicated. (A) Lanes: 1, SFE10 (sigEΔ84 amyE::PdacF-sigE335); 2, SFE11 (sigEΔ84 spoIIIE::spc amyE::PdacF-sigE335); 3, SFE12 (sigEΔ84 PdacF-sigE335); 4, SFE13 (sigEΔ84 spoIIIE::spc PdacF-sigE335); 5, SMY (wild type). (B) Lanes: 1, SFE14 (sigEΔ84 amyE::PdacF-sigE); 2, SFE15 (sigEΔ84 spoIIIE::spc amy::PdacF-sigE); 3, SFE16 (sigEΔ84 PdacF-sigE); 4, SFE17 (sigEΔ84 spoIIIE::spc PdacF-sigE).

pro-ςE is more stable than the products of sigE alleles with deletions in their pro sequences (6, 22, 32). Assuming that pro-ςE might be more readily detectable than ςE335 in the forespore environment, where heightened proteolysis is suspected, we constructed a PdacF-sigE fusion, placed it at dacF or amyE, and examined the resulting strains for evidence of pro-ςE accumulation and processing. PdacF-sigE expressed in a sigEΔ84 background from either the amyE or dacF locus yielded detectable products in Western blot analyses (Fig. 2B). This accumulation was, however, approximately 10% of that which we would have anticipated, based on the strength of the dacF promoter (data not shown). The pro-ςE expressed at amyE (Fig. 2B, lane 1) was more abundant than the pro-ςE expressed at dacF (Fig. 2B, lane 3), and a portion of it was processed into mature ςE. Although there was no apparent processing of the pro-ςE that was expressed at the dacF locus (Fig. 2B, lane 3), the degree of processing observed in the strain that expressed pro-ςE from amyE was minimal (Fig. 2B, lane 1) and the synthesis of pro-ςE from the dacF locus was relatively low (Fig. 2B, lane 3). Thus, it is not clear if the absence of processing in the latter case is due merely to low pro-ςE abundance and our failure to detect the processed product or to the lack of a processing potential. The difference in the relative abundance of the wild-type sigE products synthesized at amyE versus those synthesized at dacF was less than that which we observed for sigE335 products. This may be due to the stabilizing effect of the pro sequence on the fusion that was expressed at dacF. Disruption of spoIIIE resulted in an increase in the ratio of mature ςE to pro-ςE in the strain where pro-ςE was expressed at amyE (Fig. 2B, lane 2) and a detectable level of ςE in the strain where sigE was expressed at dacF (Fig. 2B, lane 4). As in the experiment described above, we interpret the sigE products found in the spoIIIE sigEΔ84 dacF-PdacF-sigE strain as likely to be expressed by the mother cell due to a partial activation of ςF in that compartment.

Taken together, the data suggest that forespore-expressed sigE products are more likely to accumulate and produce detectable ςE if they are either encoded at a site that enters the forespore early or synthesized in a strain that lacks a functional spoIIIE.

Effect of spoIIGA and sigE coexpression and spoIIIE on pro-ςE::GFP processing in the forespore.

We had recently noted that a pro-ςE::GFP chimera can be processed into ςE::GFP if it is expressed in the predivisional cell but not if it is synthesized from PdacF in the forespore (19). Pro-ςE processing in vegetative B. subtilis requires only SpoIIGA and SpoIIR (26). It was therefore surprising that processing did not occur in the forespore, where both of these proteins should also be present. Given that SigE processing in the forespore, like its accumulation, is more likely to occur if the pro-ςE is synthesized early, it seemed possible that SpoIIGA, like SigE, was disappearing from the forespore. We therefore constructed a B. subtilis strain in which both SpoIIGA and pro-ςE::GFP would be expressed from PdacF. A B. subtilis strain containing PdacF-sigE55-gfp alone and one that also included PdacF-spoIIGA were allowed to sporulate. Samples were taken for Western blot analysis to monitor potential pro-ςE::GFP processing by using an anti-GFP antibody (Clontech) as a probe. The commercial anti-GFP antibody cross-reacted with several Bacillus proteins; however, we were able to identify proteins corresponding to unprocessed and processed pro-ςE::GFP as bands of the predicted mobilities, whose appearance depended on the presence of the sigE-gfp fusion, progression of the culture to the appropriate time in sporulation, and the activity of the gene products needed for pro-ςE processing (e.g., spoIIGA). These bands are indicated in Fig. 3. As we had previously observed, the strain carrying PdacF-sigE55-gfp accumulated pro-ςE::GFP at the time in sporulation when ςF would be expected to become active in the forespore (t2) but failed to process it (Fig. 3A, lanes 1 to 4). The strain which expressed both spoIIGA and sigE55-gfp from PdacF not only formed pro-ςE::GFP but displayed fusion protein processing (Fig. 3A, lanes 5 to 8). Cells expressing the fusion proteins were viewed by phase-contrast microscopy to visualize their outlines (Fig. 4A1 to F1) and by fluorescence microscopy to localize both the GFP fusion proteins (Fig. 4A3 to F3) and DAPI-stained chromosomes (Fig. 4A2 to F2). As we had observed in the past (19), the DAPI stain preferentially highlighted the mother cell chromosome, presumably due to the difficulty of DAPI entry into the forespore compartments (Fig. 4A2 and B2). The chimeric GFP molecules of both PdacF-sigE55-gfp strains were restricted to the forespore compartments (Fig. 4A3 and B3; Table 2). Thus, the pro-ςE::GFP processing that we observed in the presence of coexpressed SpoIIGA is occurring in the forespore.

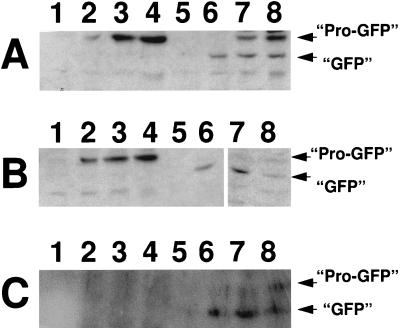

FIG. 3.

Western blot analysis of pro-ςE55::GFP accumulation in sporulating B. subtilis. Total protein (100 μg) from sporulating cells was fractionated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (12% acrylamide), transferred to nitrocellulose, and probed with an anti-GFP monoclonal antibody (Clontech). Cross-reacting proteins in the extracts were identified by using B. subtilis extracts without the fusion protein constructs as controls. Bound antibody was detected, by using a secondary antibody conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (American Qualex) and a chemoluminescent substrate (CDP-Star; Boehringer Mannheim). The position of the unprocessed (Pro-GFP) and processed (GFP) fusion proteins are indicated. (A) Lanes: 1 to 4, SFG1 (PdacF-sigE55-gfp); 5 to 8, SFG2 (PdacF-sigE55-gfp PdacF-spoIIGA). (B) Lanes: 1 to 4, SFG4 (ctc::PdacF-sigE5-gfp); 5 to 8, SFG5 (ctc::PdacF-sigE55-gfp PdacF-spoIIGA). (C) Lanes: 1 to 4, SFG3 (PdacF-sigE55-gfp sigEΔ84 spoIIIE::spc); 5 to 8, SFG6 (ctc::PdacF-sigE55-gfp sigEΔ84 spoIIIE::spc). Cells were harvested at t1 (lanes 1 and 5), t2 (lanes 2 and 6), t3 (lanes 3 and 7), and t4 (lanes 4 and 8).

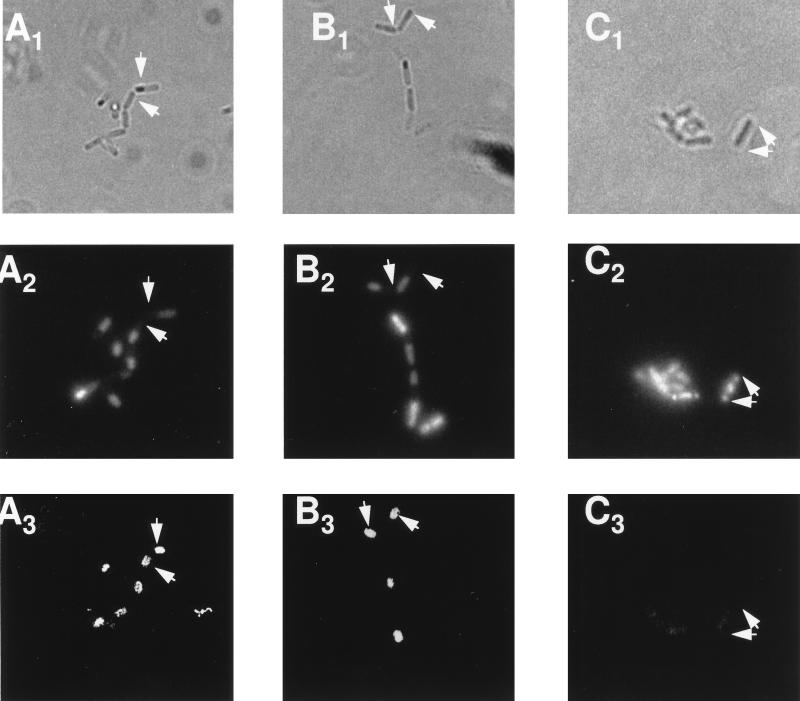

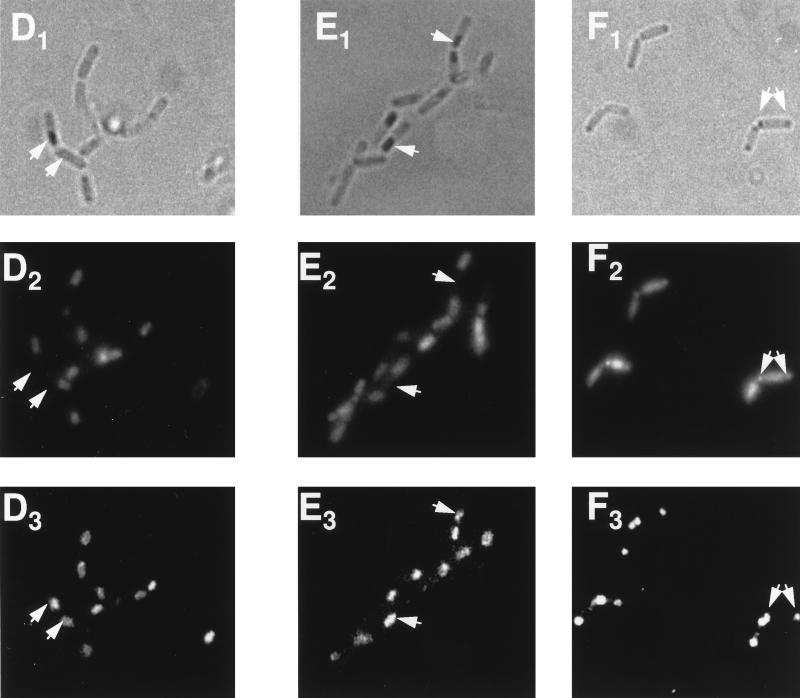

FIG. 4.

Localization of pro-ςE55::GFP in sporulating B. subtilis. Stationary-phase B. subtilis cells were diluted 1/200 in DS medium and incubated for 12 h at 30°C. Sporulation-proficient cells had reached stage III to IV by this time and the stage II mutants (SFG3 and SFG6) displayed a disporic morphology. Samples were treated as described in Materials and Methods to maximize GFP fluorescence and were then stained with DAPI. Phase-contrast microscopy was used to visualize the cells (A1 to F1). Fluorescent microscopy was used to detect DAPI-stained chromosomal DNA (A2 to F2) and GFP (A3 to F3). The arrows indicate the positions of the same forespore compartments in each micrograph of the series. (A) SFG1 (PdacF-sigE55-gfp); (B) SFG2 (PdacF-sigE55-gfp, PdacF-spoIIGA); (C) SFG3 (PdacF-sigE55-gfp sigE84 spoIIIE::spc); (D) SFG4 (ctc::PdacF-sigE55-gfp); (E) SFG5 (ctc::PdacF-sigE55-gfp PdacF-spoIIGA); (F) SFG6 (ctc::PdacF-sigE55-gfp sigΔ84 spoIIIE::spc).

TABLE 2.

GFP fluorescence patterns

| Strain (genotype) | No. of cells with a particular patterna

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| F | W | N | |

| SFG1 (PdacF-sigE55-gfp) | 78 | 0 | 5 |

| SFG2 (PdacF-sigE55-gfp PdacF-spoIIGA) | 62 | 1 | 4 |

| SFG3 (PdacF-sigE55 sigEΔ84 spoIIIE::spc) | 0 | 1 | 43 |

| SFG4 (ctc::PdacF-sigE55-gfp) | 59 | 0 | 2 |

| SFG5 (ctc::PdacF-sigE55-gfp PdacF-spoIIGA) | 77 | 4 | 8 |

| SFG6 (ctc::PdacF-sigE55-gfp sigEΔ84 spoIIIE::spc) | 64 | 1 | 17 |

F, fluorescence in forespore compartments; W, whole-cell fluorescence; N, no or weak fluorescence. Cells were grown in DS medium at 30°C and were at approximately stage III to IV of growth when counted.

We next examined whether the enhanced conversion of pro-ςE to ςE that occurs in the spoIIIE mutant could be replicated in the pro-ςE::GFP system. If it could, the location of the GFP fusion protein, and hence the site of processing, could be verified by fluorescence microscopy. As in the previous experiments, in which we tested the effects of the loss of SpoIIIE on SigE accumulation, we first positioned the fusions at a site on the chromosome (in this case, ctc) which would be transferred to the forespore in the absence of SpoIIIE and verified their synthesis in a SpoIIIE+ strain. Pro-ςE::GFP accumulated normally when expressed at this site (Fig. 3B) and was localized to the forespore compartment (Fig. 4D; Table 2). The pro-ςE::GFP did not show evidence of obvious processing in the absence of an additional source of SpoIIGA (Fig. 3B, lanes 1 to 4) but was processed if a PdacF-spoIIGA fusion was included at ctc (Fig. 3B, lanes 5 to 8). Expression of PdacF-sigE55-gfp from sites at either dacF or ctc was then tested in a SpoIIIE− background. The SpoIIIE− strain used in this experiment is congenic with the strain used in the sigE fusion experiment, i.e., it carries the sigEΔ84 mutation at spoIIG. As a consequence of this, it has a stage II, as well as a SpoIIIE−, terminal phenotype. The stage II phenotype associated with the sigEΔ84 mutation results in the placement of a second septum at the pole of the cell opposite to that at which the first septum is laid down. This is visible in the DAPI-stained micrographs of this strain (Fig. 4C2 and F2), where portions of each of the two chromosomes of the sporulating cell are partitioned into each of these two polar compartments. If PdacF-sigE-gfp is positioned at ctc in the spoIIIE::spc sigEΔ84 strain, the GFP is localized to the two polar compartments (Fig. 4F3; Table 2). Western blot analysis of these cells reveals that virtually all of the pro-ςE55::GFP has been converted to the processed form (Fig. 3C, lanes 5 to 8). We interpret these GFP results as evidence that pro-ςE processing can occur in the forespore if either additional SpoIIGA is provided or the cell is SpoIIIE−. Very little pro-ςE::GFP was synthesized in the SpoIIIE− strain from the PdacF fusion at dacF, where expression likely depends on ςF activation in the mother cell. The Western blot analysis of this strain failed to convincingly detect a pro-ςE::GFP band (Fig. 3C, lanes 1 to 4), and fluorescence microscopy revealed weak whole-cell GFP fluorescence (Fig. 4C3; Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Both pro-ςE and its processing enzyme (SpoIIGA) are synthesized in the predivisional cell; however, activation of ςE in wild-type B. subtilis is ultimately restricted to the mother cell compartment (27, 39). An immunofluorescence study by Pogliano et al. (35) gave compelling evidence for the absence of pro-ςE/ςE from the forespore shortly after septation (35). They also showed that in the absence of SpoIIIE, a protein required for chromosome translocation to the forespore, pro-ςE/ςE persisted and ςE activity could be detected in the forespore.

While attempting to express sigE gene products from forespore-specific promoters, we obtained data that support their findings. A variant sigE allele (sigE335), whose product can be distinguished electrophoretically from pro-ςE/ςE, failed to accumulate in wild-type B. subtilis (Fig. 1A and C) when it was expressed from the forespore-specific dacF promoter. A similar fusion that expressed the wild-type sigE allele did generate a product; however, its abundance was approximately 10% of the level anticipated from the activity of the promoter that drove its expression. Little wild-type SigE and no ςE335 were found to accumulate when expressed from the dacF locus, even if the strain is unable to express mother cell-specific genes (i.e., it carries sigEΔ84 at spoIIG). Thus, the factors restricting SigE’s ability to persist in the forespore do not require ongoing development in the mother cell and instead appear to be independently developed by the forespore itself.

It is believed that the B. subtilis chromosome is sequentially translocated into the forespore from a particular origin (14, 46). The position of a gene on the chromosome determines not only its time of transfer but also, as a consequence of transfer time, the likely time at which the gene is expressed in the forespore. Experimental evidence for this notion has recently been obtained in the Piggot laboratory (34). These investigators placed the ςF-dependent spoIIR gene at different sites on the B. subtilis chromosome and demonstrated a correlation between its relative time of entry into the forespore and the time at which its activity could be detected. In our experiments, ςE335 became visible in Western blots when the PdacF::sigE335 fusion was moved from late-entry sites (dacF and spoIIIG) to an early-entry locus (amyE) (Fig. 2A, lane 1). We speculate that this heightened SigE accumulation is due to its earlier synthesis. This implies that the factor responsible for SigE’s disappearance is itself not present initially but accumulates in the forespore at this time. Presumably, this factor is a forespore-specific protease which needs to be expressed from the translocated chromosome.

The result that pro-ςE, synthesized in the forespore, was more likely to be processed if it was expressed from a site that translocates to the forespore early or if the strain lacked SpoIIIE suggests that the capacity to process pro-ςE, like the ability to accumulate sigE products, is being lost in the forespore due to expression of a gene on a distal part of the translocated chromosome. A similar activity could be responsible for both events, with the SigE-processing enzyme (SpoIIGA), like SigE, becoming unstable in the forespore. In support of this idea, we found that supplemental SpoIIGA allows processing to occur in the forespore (Fig. 3A, lanes 5 to 8). Processing also occurred in the absence of additional SpoIIGA if the cell lacked SpoIIIE (Fig. 3C, lanes 5 to 8). These results are consistent with SpoIIGA, as well as SigE, being degraded by an activity that depends on SpoIIIE, presumably a factor encoded on a distal region of the chromosome.

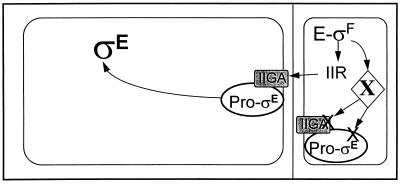

Our current view of pro-ςE processing is illustrated in Fig. 5. We had previously shown that the SigE pro sequence tethers proteins which carry it to the forespore septum (19). SpoIIGA, the pro-ςE-processing enzyme, has the structure of an integral membrane protein (38), and, as proposed by Hofmeister et al. (15), may also reside in the forespore membrane. Hence, pro-ςE and SpoIIGA could both lie at the forespore septum awaiting the signal to initiate the processing and release of active ςE into the cell interior. We suspect that ςF-dependent genes are key for both the timing and the compartmentalization of ςE activity. Following septation and ςF activation, spoIIR, a gene that is on a region of the chromosome that is translocated to the forespore early, is transcribed and triggers pro-ςE processing on both sides of the forespore septum. As additional regions of the B. subtilis chromosome enter the forespore, a gene(s) encoding a putative protease(s) (X), which is hypothesized to degrade both SigE and SpoIIGA, enters the forespore and is expressed. This results in the elimination of these proteins from the forespore and a block of their further accumulation when their coding sequence (spoIIG), on a late-entering segment of the chromosome, is finally transferred to the forespore. This model is highly speculative; however, if our notion of selective proteolysis is true, genetic screens should be able to detect the genes for these hypothetical proteases as the sites of mutations which allow SigE to persist and be active in the forespore.

FIG. 5.

Model for pro-ςE activation. SpoIIGA and pro-ςE are synthesized prior to septation and are likely to be present initially in both mother cell and forespore compartments. As proposed by several investigators (15, 20, 26), ςF becomes active in the forespore, where it directs the synthesis of the SpoIIGA activator, SpoIIR. SpoIIR then signals SpoIIGA to cleave the pro sequence from pro-ςE, which along with SpoIIGA appears to be tethered to the septal membrane (15, 19, 20, 26). Very early after septation, this reaction probably occurs in both the mother cell and forespore compartments; however, later, a hypothetical ςF-dependent gene product (X) initiates the destruction of both SigE and SpoIIGA in the forespore. ςF-transcribed genes are proposed in this model to be responsible for both the timing of ςE activation, by directing the synthesis of SpoIIR, and the restriction of ςE activity to the mother cell, by directing the synthesis of the putative protease that degrades SpoIIGA and SigE.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by NSF grant MCB-9417735.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alper S, Duncan L, Losick R. An adenosine nucleotide switch controlling the activity of a cell type-specific transcription factor in B. subtilis. Cell. 1994;77:195–205. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90312-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arigoni F, Duncan L, Alper S, Losick R, Stragier P. SpoIIE governs the phosphorylation state of a protein regulating transcription factor ςF during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3238–3242. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arigoni F, Pogliano K, Webb C, Stragier P, Losick R. Localization of protein implicated in establishment of cell type to sites of asymmetric cell division. Science. 1995;270:637–640. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5236.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barák I, Behari J, Olmedo G, Guzman P, Brown D P, Castro E, Walker D, Westpheling J, Youngman P. Structure and function of the Bacillus SpoIIE protein and its localization to sites of sporulation septum assembly. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:1047–1060. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.433963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benson A K, Haldenwang W G. Regulation of ςB levels and activity in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2347–2356. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.8.2347-2356.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carlson H C. Ph.D. thesis. San Antonio: University of Texas Health Science Center; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlson H C, Lu S, Kroos L, Haldenwang W G. Exchange of precursor-specific elements between pro-ςE and pro-ςK of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:546–549. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.2.546-549.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diederich B, Wilkinson J F, Magnin T, Najafi S M A, Errington J, Yudkin M D. Role of interactions between SpoIIAA and SpoIIAB in regulating cell-specific transcription factor ςF of Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2653–2663. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.21.2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Driks A, Losick R. Compartmentalized expression of a gene under the control of sporulation transcription factor ςE in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:9934–9938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.22.9934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duncan L, Alper S, Arigoni F, Losick R, Stragier P. Activation by cell-specific transcription by a serine phosphatase at the site of asymmetric division. Science. 1995;270:641–644. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5236.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duncan L, Alper S, Losick R. SpoIIAA governs the release of the cell-type specific transcription factor ςF from its anti-sigma factor SpoIIAB. J Mol Biol. 1996;260:147–164. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duncan L, Losick R. SpoIIAB is an anti-ς factor that binds to and inhibits transcription by regulatory protein ςF from Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:2325–2329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Errington J, Illing N. Establishment of cell specific transcription during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:689–695. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feucht A, Magnin T, Yudkin M D, Errington J. Bifunctional protein required for asymmetric cell division and cell-specific transcription in B. subtilis. Genes Dev. 1996;10:794–803. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.7.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hofmeister A E M, Londoño-Vallejo A, Harry E, Stragier P, Losick R. Extracellular signal protein triggering the proteolytic activation by a developmental transcription factor in B. subtilis. Cell. 1995;83:219–226. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90163-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Illing N, Errington J. Genetic regulation of morphogenesis in Bacillus subtilis: roles of ςE and ςF in prespore engulfment. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:3159–3169. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.10.3159-3169.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jonas R M, Peters III H K, Haldenwang W G. Phenotypes of Bacillus subtilis mutants altered in the precursor-specific region of ςE. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:4178–4186. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.8.4178-4186.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jonas R M, Weaver E A, Kenney T J, Moran C P, Jr, Haldenwang W G. The Bacillus subtilis spoIIG operon encodes both ςE and a gene necessary for ςE activation. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:507–511. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.2.507-511.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ju J, Luo T, Haldenwang W. Bacillus subtilis pro-ςE fusion protein localizes to the forespore septum and fails to be processed when synthesized in the forespore. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4888–4893. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.15.4888-4893.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karow L M, Glaser P, Piggot P J. Identification of a gene, spoIIR, which links the activation of ςE to the transcriptional activity of ςF during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2012–2016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.6.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kenney T J, Moran C., Jr Organization and regulation of an operon that encodes a sporulation-essential sigma factor in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:3329–3339. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.7.3329-3339.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.LaBell T, Trempy J E, Haldenwang W G. Sporulation specific ς factor, ς29 of Bacillus subtilis, is synthesized from a precursor protein, p31. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:1784–1788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.7.1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le Blanc D J, Inamine J M, Lee L N. Broad geographical distribution of homologous erythromycin, kanamycin and streptomycin resistance determinants among group D streptococci of human and animal origin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986;29:549–555. doi: 10.1128/aac.29.4.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewis P J, Errington J. Use of green fluorescent protein for detection of cell-specific gene expression and subcellular protein localization during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology. 1996;142:733–740. doi: 10.1099/00221287-142-4-733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewis P J, Magnin T, Errington J. Compartmentalized distribution of the proteins controlling the prespore-specific transcription factor ςF of Bacillus subtilis. Genes Cells. 1996;1:881–894. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1996.750275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Londoño-Vallejo J-A, Stragier P. Cell-cell signaling pathway activating a developmental transcription factor in Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev. 1995;9:503–508. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.4.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Losick R, Stragier P. Crisscross regulation of cell-type specific gene expression during development in B. subtilis. Nature (London) 1992;355:601–604. doi: 10.1038/355601a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Margolis P, Driks A, Losick R. Establishment of cell type by compartmentalized activation of a transcription factor. Science. 1991;254:562–565. doi: 10.1126/science.1948031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Min K-T, Hilditch C M, Diederich B, Errington J, Yudkin M D. ςF, the first compartmental-specific ς factor of B. subtilis, is regulated by an anti-ς factor that is also a protein kinase. Cell. 1993;74:735–742. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90520-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miyao A, Theragool G, Takeuchi M, Kobayashi Y. Bacillus subtilis spoVE gene is transcribed by ςE-associated RNA polymerase. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4081–4086. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.13.4081-4086.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peters H K, III, Carlson H C, Haldenwang W G. Mutational analysis of the precursor-specific region of Bacillus subtilis ςE. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4629–4637. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.14.4629-4637.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peters H K, III, Haldenwang W G. Isolation of a Bacillus subtilis spoIIGA allele that suppresses processing-negative mutations in the pro-ςE gene (sigE) J Bacteriol. 1994;176:7763–7766. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.24.7763-7766.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Piggot, P. Personal communication.

- 35.Pogliano K, Hofmeister A E M, Losick R. Disappearance of the ςE transcription factor from the forespore and the SpoIIE phosphatase from the mother cell contributes to establishing cell-specific gene expression during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3331–3341. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.10.3331-3341.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmidt R, Margolis P, Duncan L, Coppolecchia R, Moran C P., Jr Control of transcription factor ςF by sporulation regulatory proteins SpoIIAB in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9221–9225. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.23.9221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schuch R, Piggot P. The dacF-spoIIA operon of Bacillus subtilis, encoding ςF, is autoregulated. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4104–4110. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.13.4104-4110.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stragier P, Bonamy C, Karmazyn-Campelli C. Processing of a sporulation sigma factor in Bacillus subtilis: how morphological structure could control gene expression. Cell. 1988;52:697–704. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90407-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stragier P, Losick R. Molecular genetics of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Annu Rev Genet. 1996;30:297–341. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.30.1.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun D, Stragier P, Setlow P. Identification of a new sigma factor involved in compartmentalized gene expression during sporulation of Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev. 1989;3:141–149. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.2.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trempy J E, Bonamy C, Szulmajster J, Haldenwang W G. Bacillus subtilis sigma factor sigma 29 is the product of the sporulation essential gene spoIIG. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:4189–4192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.12.4189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Truitt C L, Ray G L, Trempy J E, Da-Jian Z, Haldenwang W G. Isolation of Bacillus subtilis mutants altered in expression of a gene transcribed in vitro by a minor form of RNA polymerase (E-ς37) J Bacteriol. 1985;161:515–522. doi: 10.1128/jb.161.2.515-522.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Webb C D, Decatur A, Teleman A, Losick R. Use of green fluorescent protein for visualization of cell-specific gene expression during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5906–5911. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.20.5906-5911.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu J J, Howard M G, Piggot P J. Regulation of transcription of the Bacillus subtilis spoIIA locus. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:692–698. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.2.692-698.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu J-J, Schuch R, Piggot P J. Characterization of a Bacillus subtilis sporulation operon that includes genes for an RNA polymerase ς factor and for a putative dd-carboxypeptidase. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4885–4892. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.15.4885-4892.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu L J, Errington J. Bacillus subtilis SpoIIIE protein required for DNA segregation during asymmetric cell division. Science. 1994;264:572–575. doi: 10.1126/science.8160014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yasbin R E, Wilson G A, Young F E. Transformation and transfection in lysogenic strains of Bacillus subtilis 168. J Bacteriol. 1973;113:540–548. doi: 10.1128/jb.113.2.540-548.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang L, Higgins M L, Piggot P J, Karow M L. Analysis of the role of prespore gene expression in the compartmentalization of mother cell-specific gene expression during sporulation of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2813–2817. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.10.2813-2817.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]