Adolescence is a period of psychosocial change that is often perplexing for both teens and their parents. The rapid physical changes that occur at this time lead adolescents to become preoccupied with their body image. Adolescents may become preoccupied with themselves, uncertain about their appearance, compare their bodies with those of other teens, and become increasingly interested in sexual anatomy and physiology.1 Anorexia nervosa is an eating disorder that disproportionately affects adolescents and has its origin, at least partially, in this preoccupation with body image.

DEFINITION

Anorexia nervosa is an eating disorder characterized by a fierce quest for thinness. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition, defines patients with anorexia nervosa as having an intense fear of gaining weight, putting undue influence on body shape or weight for self-image, having a body weight which is less than 85% of the weight that would be predicted, and missing at least three consecutive menstrual periods.2

Summary points

Anorexia nervosa has its peak incidence in adolescence

Effective treatments are available

Serious endocrine and cardiovascular complications are associated with anorexia nervosa, as are gastrointestinal and dermatological complications

There is frequently an overlap between athletics and anorexia nervosa in adolescents, which increases the potential for morbidity and mortality

Many of the dangerous complications of anorexia nervosa develop during the refeeding phase; close medical monitoring is prudent during the early stages of weight restoration

METHODS

Evidence presented in this review was culled from reference sources identified from a MEDLINE current literature search.

INCIDENCE AND PREVALENCE

Anorexia nervosa most commonly occurs in teenage girls, although boys are also affected, especially in the prepubertal age group. The ratio of girls to boys is approximately 10-20:1.3 About 2% to 3% of young women have anorexia nervosa or a clinically important variant of the disorder.4 There has been a consistent increase in the incidence of anorexia nervosa over the past 10 years.5 The variable performance of questionnaires designed to screen for eating disorders, such as the Eating Attitudes Test and the Eating Disorders Inventory, coupled with the difficulty of defining cases and the tendency of patients to hide their illness has made epidemiological studies difficult.6,7,8

Hsu, in a review of 24 epidemiological studies, reported a prevalence of pure anorexia nervosa of 0.5% in young women in Western cultures.6 Reviewing selective studies of case registries, Hsu found that the annual incidence ranged from 14.1 cases/100,000 girls and women aged 10-24 to 43 cases/100,000 girls and women aged 16-24.

Dieting is a major risk factor for eating disorders. The prevalence of eating disorders in a culture parallels the prevalence of dieting behavior.4 In non-Western cultures, a low prevalence of both eating disorders and dieting exists, although adolescents of all races who belong to higher socioeconomic groups are at an increased risk. Studies have confirmed that white women in higher socioeconomic classes diet more and are more concerned about their weight than other subgroups of women.6 Participation in hobbies and occupations, such as modeling and ballet, that promote the ideal of thinness seems to lead to a higher prevalence of eating disorders.3 Fairburn, in a study of putative risk factors for anorexia nervosa, concluded that perfectionism and negative self-evaluation are common antecedents of both anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa.9 This study also suggested that a genetic association with parental eating disorders, dieting by other family members, and negative comments made by other family members about body appearance were risk factors for anorexia nervosa. Other proposed risk factors include substance misuse, affective disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, dissatisfaction with body image, and stressful life events (see box).

PROGNOSTIC FACTORS AND OUTCOMES

Anorexia nervosa is associated with the highest mortality of all the psychiatric diseases. Crude mortality ranges from 5% to 10%10; this increased mortality is most often caused by cardiovascular causes occurring secondary to emaciation. There is also an increased risk of suicide.11 The standardized mortality ratio, or the number of deaths among a similar cohort without anorexia nervosa, ranges from 3.8 to 14.4.11 About 50% of patients recover, 30% improve but continue to struggle with weight issues, and the remaining 20% do poorly. The best predictive factors for recovery are the percentage decrease from ideal body weight and the length of time the patient has been anorexic. For every 10% loss in ideal body weight there is an 18% increase in the risk of poor outcome.12 Extreme amounts of compulsive exercise and a previous history of difficult social interactions have also been predictive of a poor outcome in an adolescent population.13

MEDICAL COMPLICATIONS

Most of the medical complications of anorexia nervosa are the direct result of weight loss and malnutrition. Patients typically complain of intolerance to the cold, dry skin, and brittle hair and nails. Patients also grow fine, downy hair, known as lanugo hair, on the sides of the face, arms, and back. This is not a sign of masculinization but probably represents an attempt by the body to conserve heat. Patients often have impaired thermoregulation and acrocyanosis of their hands and feet. Laboratory tests are generally normal in patients with anorexia nervosa who do not engage in any purging behaviors until the most severe stages of the illness. Clinically insignificant leukopenia and anemia occur occasionally.14 The patient can be reassured and encouraged that all of these changes will be reversed when weight is regained.15 For the primary care physician these changes should not raise much concern.

Clues to the existence of anorexia nervosa

Unexplained weight loss, especially in adolescents

Failure to gain weight in proportion to height

Secondary amenorrhea in adolescents or preadolescents

Participation in hobbies or spots promoting or requiring weight loss (for example, ballet or wrestling)

Preoccupation with losing additional weight or preoccupation with changing body shape despite thinness

Low triiodothyronine concentrations and low luteinizing hormone concentrations (however, be sure to differentiate from low luteinizing hormone during normal menstrual cycles)

Feeling cold compared to peers (often with objective hypothermia)

Hair loss

Development of lanugo hair (fine, downy hair on face and back)

Refusing to eat with others

Eating slowly and cutting food into small portions

Eating at odd times

Gastrointestinal problems

The gastrointestinal tract is a common source of complaints. Most patients with anorexia have a prolongation of gastrointestinal transit time. This causes complaints of abdominal bloating and constipation. Adolescent patients are bothered by these symptoms and often attribute them to food and being fat, which perpetuates their avoidance of food and may precipitate purging behaviors. The constipation is caused by reflex hypofunctioning of the colon due to lack of intake.16 Encouraging patients to eat smaller meals more frequently, educating them about the cause of these symptoms, and reassuring them that they will resolve over 2 to 3 weeks with regular eating, along with prescribing prokinetic agents, such as cisapride, seem to be beneficial in facilitating the refeeding process. Caution must be observed when this drug in used in treating anorexia nervosa because it can prolong the QT interval, a complication which can occur independently of drug treatment in these patients.

Endocrine problems

For adolescents with anorexia nervosa, the endocrine changes that may occur pose the most danger in the long term if they are not appropriately treated. Amenorrhea is a cardinal manifestation of anorexia nervosa, and it can be either primary or secondary. Puberty may be delayed in adolescents because of a reduction in pulsatile gonadotropin-releasing hormone from the hypothalamus resulting in low serum concentrations of estradiol. About 20% of patients with anorexia nervosa experience amenorrhea before the onset of weight loss. Resumption of menses generally occurs when the patients weigh about 90% of their ideal body weight but amenorrhea may persist when there is a low percentage of body fat or there are unresolved emotional issues.17

Amenorrhea is an important risk factor for severe osteoporosis. The prevention of osteoporosis is one of the main challenges for primary care physicians. It is at adolescence that most of a person's peak bone mass is acquired.18 Adolescent patients with anorexia nervosa are therefore less likely to reach their peak bone density and are at risk of premature osteoporosis and fractures, as well as being at risk of irreversibly stunting their growth.1,19 Most studies have noted supplementation with estrogen to be protective against osteoporosis in anorexia nervosa.20 This is presumably due to the inability of estrogen replacement therapy to correct other factors assumed to be involved in premature osteoporosis, such as hypercortisolism. The long-term outcome of osteopenia in anorexia nervosa has only recently been elucidated. Trabecular bone seems to be less affected than cortical bone. Studies show that despite the resumption of menses and weight gain, cortical bone mineral density does not return to normal.21

Primary care physicians might use densitometry periodically to assess the bone mineral density of adolescents with anorexia nervosa. If osteopenia is detected, early and aggressive attention must be directed toward preventing the pernicious development of further bone loss and osteoporosis. Restoring body weight and resuming menses should be the goals. High-dose calcium (1500 mg/day) and vitamin D (800 IU/day) supplements are important, especially given the possible role of excess cortisol in osteoporosis in anorexia nervosa. In addition, although there is little scientific data to support the use of estrogen alone to attenuate bone loss, it should not be completely ruled out. If, despite these interventions, there is evidence of progressive bone loss, bisphosphonate therapy, with alendronate, should be considered, especially since it has proven efficacy in treating osteoporosis induced by steroids.22 The bone loss associated with anorexia nervosa is profound and occurs early in the course of the illness; it causes premature fractures, and once it is established, it is difficult to restore skeletal integrity.

Other minor endocrine changes seen with anorexia nervosa are the euthyroid sick syndrome manifested by low serum triiodothyronine concentrations, increased reverse triiodothyronine concentrations, and normal concentrations of thyroid stimulating hormone. These adaptive changes are made to conserve calories and should not be treated with thyroid hormone. Diabetes insipidus with reduced concentrating capacity and hyponatremia has also been described. Hypoglycemia is common among adolescent patients; it is usually asymptomatic until the disease is severe. Then, hypoglycemia may become more marked and indicative of a poorer overall prognosis.

Cardiovascular problems

Most deaths in adolescent patients with anorexia nervosa are caused by cardiovascular collapse, which occurs secondary to malnutrition and emaciation. With progressive weight loss there is a decrease in left ventricular mass and stroke volume. As a result, maximal work capacity is markedly diminished.23 In addition, there is an increased incidence of sudden death. This is presumably a result of autonomic imbalance, a prolonged QT interval, and arrhythmias related to electrolyte abnormalities (especially if patients are purging themselves). Postmortem studies in cases with anorexia have not identified serious atherosclerosis.24 Primary care physicians must be cautious about prescribing any drugs that can prolong the QT interval.

Although bradycardia and hypotension are consistently found in these patients, they are generally benign and related to a reduction in the basal metabolic rate as the body tries to save energy. Thus, these are physiological changes and should not be treated. However, heart rates of less than 30 to 35 beats/minute need to be evaluated and monitored.

A potentially catastrophic syndrome referred to as the refeeding syndrome is related to these cardiac changes. Classically, this refers to severe hypophosphatemia and the inherent complications that develop when any severely malnourished person is refed. Phosphate depletion produces widespread abnormalities at the cellular level mainly due to depletion of compounds such as adenosine triphosphate. This depresses the cardiac stroke volume, which in the setting of a repleted circulatory volume, can promote congestive heart failure. This syndrome is preventable as long as refeeding is started slowly and caloric increases are modest during the first 2 to 3 weeks of refeeding. Checking serum electrolytes and phosphorus concentrations every 2 to 3 days can reduce the risk of these problems. Monitoring the patient's pulse for unexpected increases and checking for edema are important parts of the refeeding treatment plan (see box).25

ATHLETICS AND ANOREXIA

Anorexia nervosa is not uncommon among competitive athletes. Primary care clinicians who treat adolescent patients must remember that their primary obligation is to the athlete and not to the success of the athletic department. For the adolescent with anorexia who has amenorrhea there are no definite guidelines for safely participating in sports. Any athlete who has anorexia and is found to have a potentially lethal cardiovascular abnormality, including a prolonged QT interval, should be banned from competitive sports regardless of the athlete's willingness to waive liability.26 Certainly, measurements of bone mineral density should be considered since different sports are associated with varying degrees of risk for fractures. Athletic training in combination with the excessive exercising which is often found in these patients can result in additional weight loss and significant medical morbidity and even mortality.

Strategies to avoid refeeding syndrome

Identify patients at risk (for example, any patient who is chronically malnourished or who has not eaten for 7-10 days)

Measure serum electrolyte concentrations and correct abnormalities before refeeding

Obtain serum chemistry values every other day for the first 7-10 days, then weekly during remainder of refeeding

Attempt to slowly increase daily caloric intake by 200 to 300 kcal every 3-4 days until caloric intake is adequate

Monitor patient carefully for development of tachycardia and edema

TREATMENT

Discussion of the many different treatment modalities used in anorexia nervosa is beyond the scope of this paper. Family counseling is valuable especially for patients younger than 18 years. Weight gain must be closely linked to a program of psychotherapy: one without the other is unlikely to be successful regardless of how much patients with anorexia would like to participate in psychotherapy without regaining weight. Psychotherapeutic approaches are often indicated.27 In general, medications are more effective in treating bulimia than anorexia nervosa. Although most adolescent patients with anorexia can be treated as outpatients, inpatient treatment is recommended in certain situations. Hospitalization is recommended for patients whose weight loss has been rapid or who have lost more than 25%-30% of their ideal body weight, as well as for those with cardiovascular arrhythmias.28 Lastly, patients with anorexia nervosa who are more than 20% below their ideal body weight or who have cardiovascular abnormalities should be referred to a specialist who regularly treats patients with anorexia nervosa.

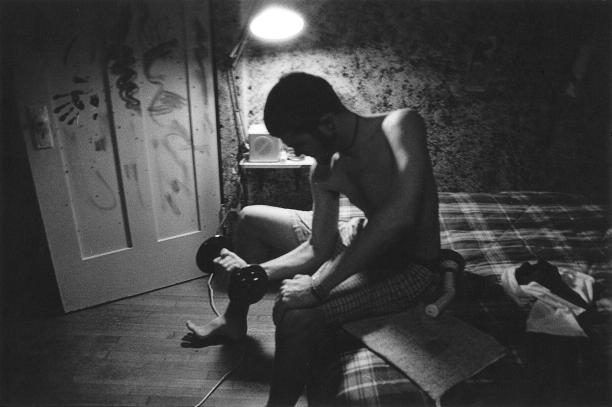

Figure 1.

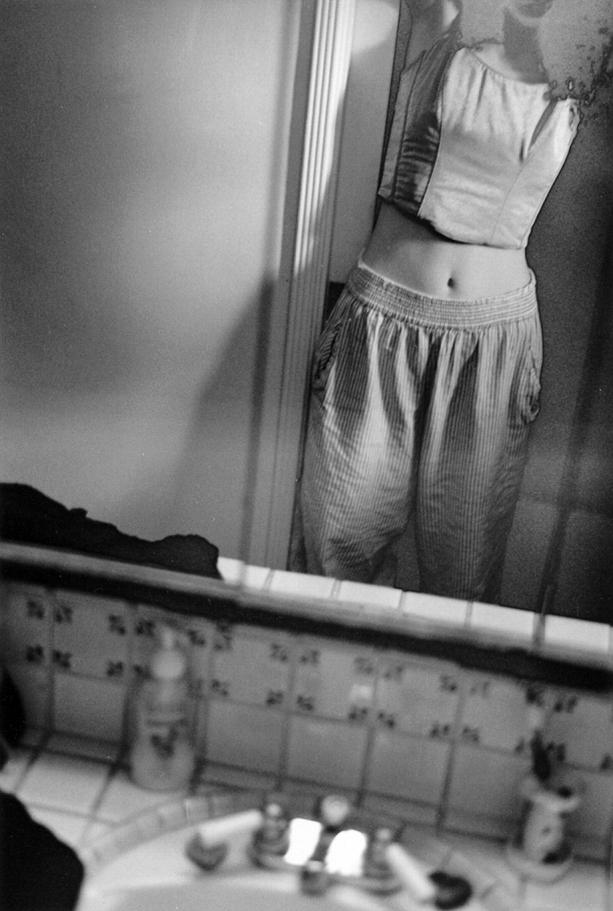

Figure 2.

Funding: None

Competing interests: None declared

References

- 1.Neinstein L, Juliani M, Shapiro J. Psychosocial development in normal adolescents. In: Neinstein L, ed. Adolescent health care: a practical guide. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1996: 42-44.

- 2.Pryor T. Diagnostic criteria for eating disorders: DSM IV revision. Psychiatr Ann 1995;25: 40-49. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pawluck DE, Gorey KM. Secular trends in the incidence of anorexia nervosa: integrative review of population-based studies. Int J Eat Disord 1998;23: 347-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shisslak CM, Crago M, Estes LS. The spectrum of eating disturbances. Int J Eat Disord 1995;18: 209-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engles J, Hohnston M, Hunter D, et al. Increasing incidence of anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry 1995;152: 1266-1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hsu LKG. Epidemiology of the eating disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1996;19: 681-700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wakeling A. Epidemiology of anorexia nervosa. Psychiatry Res 1996;62: 3-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fichter MD, Elton M, Engle K, et al. Structured interviews for anorexia and bulimia. Int J Eating Disord 1991;10: 571-592. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Doll HA, et al. Risk factors for anorexia nervosa. Arch Gen Psych 1999;56: 468-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schoemaker C. Does early intervention improve the prognosis in anorexia nervosa? Int J Eat Disord 1997;21: 1-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deter H, Herzog W. Anorexia nervosa in a long-term perspective: results of the Hedelberg-Mannheim study. Psychosom Med 1994;56: 20-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herzog DB, Sacks NR, Keller MB, et al. Patterns and predictors of recovery in anorexia nervosa. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1993;32: 835-842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strober M, Freeman R, Morrell W. The long-term course of severe anorexia nervosa in adolescents: survival analysis of recovery, relapse and outcome predictors over 10-15 years. Int J Eat Disord 1997;22: 334-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mehler PS, Howe SE. Serous fat atrophy in anorexia nervosa. Am J Hematol 1995;48: 345-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehler PS, Gray M, Schulte M. Medical complications of anorexia nervosa. J Wom Health 1997;6: 5-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chun AB, Sokol MS, Kaye WH, et al. Colonic function in constipated patients with anorexia nervosa. Am J Gastroenterol 1997;92: 1879-1883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Golden NH, Jacobson MS, Solanto M, et al. Resumption of menses in anorexia nervosa. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1997;151: 16-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carmichael K, Carmichael D. Bone metabolism and osteoporosis in eating disorders. Medicine 1995;74: 254-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mehler PS. Medical complications of eating disorders. N Engl J Med 1999;341: 614-615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klibanski A, Biller BMK, Shoenfeld DA, et al. The effects of estrogen administration on trabecular bone loss in young women with anorexia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1995;80: 898-904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ward A, Brown N, Treasure J. Persistent osteopenia after recovery from anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 1997;22: 71-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adachi J, Bensen W, Brown J, et al. Intermittent etidronate therapy to prevent corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 1997;337: 383-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeSimone G. Cardiac abnormalities in young women with anorexia nervosa. Br Heart J 1994;71: 287-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Isner J, Roberts W, Heynsfield M, et al. Anorexia nervosa and sudden death. Ann Intern Med 1985;102: 49-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mehler PS, Weiner K. Anorexia nervosa and total parenteral nutrition. Int J Eat Disord 1994;14: 297-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maron B, Mitten M, Quandt E, et al. Competitive athletes with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med 1998;339: 1632-1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Becker AE, Grinspoon SK, Klibanski A, et al. Eating disorders. N Engl J Med 1993;340: 1092-1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Halmi KA. A 24-year-old woman with anorexia nervosa. JAMA 1998;279: 1992-1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]