Abstract

Objectives To describe physicians' prognostic accuracy in terminally ill patients and to evaluate the determinants of that accuracy. Design Prospective cohort study. Setting Five outpatient hospice programs in Chicago. Participants A total of 343 physicians provided survival estimates for 468 terminally ill patients at the time of hospice referral. Main outcome measures Patients' estimated and actual survival. Results Median survival was 24 days. Of 468 predictions, only 92 (20%) were accurate (within 33% of actual survival); 295 (63%) were overoptimistic, and 81 (17%) were overpessimistic. Overall, physicians overestimated survival by a factor of 5.3. Few patient or physician characteristics were associated with prognostic accuracy. Male patients were 58% less likely to have overpessimistic predictions. Medical specialists excluding oncologists were 326% more likely than general internists to make overpessimistic predictions. Physicians in the upper quartile of practice experience were the most accurate. As the duration of the doctor-patient relationship increased and time since last contact decreased, prognostic accuracy decreased. Conclusions Physicians are inaccurate in their prognoses for terminally ill patients, and the error is systematically optimistic. The inaccuracy is, in general, not restricted to certain kinds of physicians or patients. These phenomena may be adversely affecting the quality of care given to patients near the end of life.

INTRODUCTION

Although physicians commonly have to prognosticate, most feel uncomfortable doing so.1 Neither medical training1,2 nor published literature3,4 treat prognostication as important, and prognostic error is widespread.2 Unfortunately, prognostic error may have untoward effects on both patient care and social policy.

Parkes showed that physicians' predictions of survival in 168 cancer patients were often erroneous and optimistic,5 and these findings were confirmed by subsequent studies.6,7,8,9,10 However, previous work has been limited by the use of small samples of patients and of prognosticators (typically <4), failure to examine whether certain types of physicians are more likely to err in certain types of patients, and neglect of the possibility of different determinants of optimistic and pessimistic error. We conducted a large, prospective cohort study of terminally ill patients to evaluate the extent and determinants of prognostic error.

PARTICIPANTS AND METHODS

Our cohort consisted of all patients admitted to 5 outpatient hospice programs in Chicago during 130 consecutive days in 1996. Participating hospices notified us about patients on admission, and we immediately contacted the referring physicians to administer a 4-minute telephone survey. Of the 767 patients (referred by 502 physicians), 65 did not meet the entry criteria (they were children, were denied hospice admission, or refused to give consent), and 51 died before we were notified (survival predictions would be meaningless). Of the remaining 651 patients, for 66 (10.1%) we contacted the physician only after the patient's death (and so could not get meaningful prognoses), for 14 (2.2%) the physician refused to participate, and for 67 (10.3%) the physician could not be contacted. We, thus, completed surveys with 365 physicians caring for 504 patients (77.4%). Comparison of these 504 patients with the 147 excluded patients showed no important differences in patient or physician characteristics. On June 30, 1999, we had dates of death for 486 (96.4%) of the 504 patients. Because data were occasionally missing, not all totals in the analyses are equivalent.

We obtained the patients' age, sex, race, religion, marital status, diagnosis, and comorbidities from the hospice. From the survey, we obtained an estimate of how long the patient had to live; information about the patient, including Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status11 and duration of illness; information about the physician, including experience with similar patients and self-rated dispositional optimism; and information about the doctor-patient relationship, including the duration, recentness, and frequency of contact. From public records, we obtained other data on the physicians, such as specialty, years in practice, and board certification. Dates of patients' deaths were obtained from public death registries or the hospices.

We divided the observed by the predicted survival and deemed prognoses accurate if this quotient was between 0.67 and 1.33. Values less than 0.67 were optimistic prognostic errors, and those greater than 1.33 were pessimistic. We conducted analyses using different cutoff points or more categories, as well as analyses that treated this quotient as a continuous measure, but these analyses did not contravene the results presented. To evaluate associations between categoric and continuous variables and the trichotomous prognostic accuracy variable, we used χ2 tests and analysis of variance, respectively. We used multinomial logistic regression to assess the multivariate effect of patient and physician variables on prognostic accuracy.

RESULTS

The patients had a mean (SD) age of 68.6 (17.4) years, and 225 (44.6%) were men. The diagnosis in 326 patients (64.7%) was cancer, in 62 patients (12.3%) it was acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), and 116 patients (23.0%) had other conditions. The mean duration of disease was 83.5 (135.8) weeks, and the median performance status was 3 (corresponding to >50% of the day spent bedridden). The physicians had a median duration of medical practice of 16 years; of 363 physicians, 291 (80.2%) were men; of 365 physicians, 293 (80.3%) were board certified; and of 345 physicians, 255 (73.9%) rated themselves optimistic. Of 358 physicians who listed their specialty, 114 (31.8%) specialized in general internal medicine, 71 (19.8%) in internal medicine subspecialties excluding oncology, 61 (17.0%) in oncology, 55 (15.4%) in family or general practice, 27 (7.5%) in geriatrics, and 30 (8.4%) were surgeons or practiced other specialties. In the past year, the physicians had cared for a median of 5 patients with the same diagnosis and had referred a median of 8 patients to a hospice. They had known the patient a mean of 159.2 (307.7) weeks, had 11.1 (13.9) contacts in the previous 3 months, and had examined the patient 14 (29) days before.

Physicians' prognostic estimates

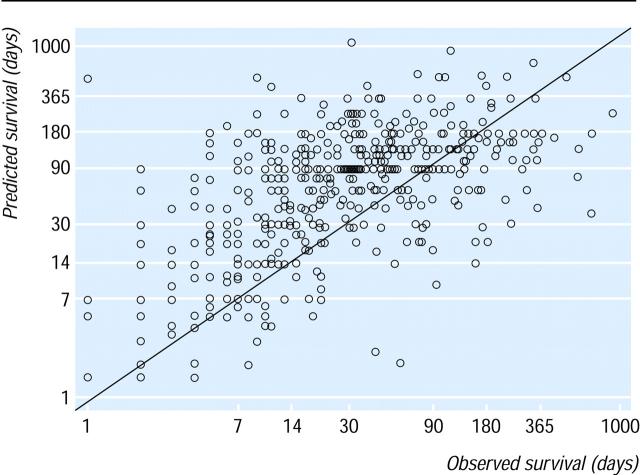

In only 18 of 504 patients did the physician refuse to predict survival to us. Of the remaining 486 patients, 18 had missing dates of death, leaving 468 patients referred by 343 physicians for analysis of prognostic accuracy. The figure illustrates the extent of the error. The median observed patient survival was 24 days. The mean ratio of predicted to observed survival was 5.3. The correlation between predicted and observed survival was 0.28 (P < 0.01). When an accurate prediction was defined as between 0.67 and 1.33 times the actual survival, 92 (19.7%) of 468 predictions were accurate, 295 (63.0%) were optimistic, and 81 (17.3%) were pessimistic. When an accurate prediction was defined as between 0.50 and 2.0 times the actual survival, 159 (34.0%) of 468 predictions were accurate, 256 (54.7%) were optimistic, and 53 (11.3%) were pessimistic. Death occurred within 1 month of the predicted date for 195 patients (41.7%), at least 1 month before the predicted date in 214 patients (45.7%), and at least 1 month after the predicted date in 59 patients (12.6%).

Figure 1.

Predicted vs observed survival in 468 terminally ill hospice patients. Diagonal line represents perfect prediction. Circles above diagonal line represent patients in whom survival was overestimated; those below line are patients in whom survival was underestimated.

The extent of prognostic error varied depending on both observed and predicted survival (table). The longer the observed survival (that is, the less ill the patient), the lower the error; conversely, the longer the predicted survival, the greater the error.

Table 1.

Doctors' overestimates of patient survival by observed and predicted survival

| % Overestimate in survival (mean) | No. of patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Observed survival (days) | ||

| 1-30 | 795 | 251 |

| 31-90 | 288 | 130 |

| 91-180 | 136 | 49 |

| >180 | 71 | 38 |

| Overall | 526 | 468 |

| Predicted survival (days) | ||

| 1-30 | 192 | 150 |

| 31-90 | 382 | 144 |

| 91-180 | 501 | 119 |

| >180 | 1,872 | 55 |

| Overall | 526 | 468 |

Factors associated with prognostic accuracy

Bivariate analyses of the trichotomous accuracy variable and patient attributes showed no important differences in patients' age, sex, race, religion, or marital status. However, patients with cancer were the most likely to have overoptimistic predictions (202 [67.1%] of 301 patients with cancer vs 37 [63.8%] of 58 patients with AIDS and 56 [51.4%] of 109 other patients) and the least likely to have overpessimistic predictions (39 [13.0%] of 301 patients with cancer vs 13 [22.4%] of 58 AIDS patients and 29 [26.6%] of 109 other patients); AIDS patients were the least likely to have correct predictions (8 [13.8%] of 58 patients vs 60 [19.9%] of 301 patients with cancer and 24 [22.0%] of 109 patients with other conditions). All comparisons were significant (P < 0.01).

Bivariate analyses of the physician attributes showed no important differences in sex, years in medical practice, board certification, self-rated optimism, number of hospice referrals in the past year, or number of medically similar patients in the past year. However, physicians in medical subspecialties excluding oncology were the least likely to give correct estimates (8 [10.1%] of 79 physicians vs 11 [36.7%] of 30 physicians in surgery or other, 18 [26.9%] of 67 physicians in family or general practice, 24 [22.9%] of 105 physicians in oncology, and 30 [16.7%] of 180 physicians in geriatric or general internal medicine), and oncologists were the least likely to be overpessimistic in their estimates (10 [9.5%] of 105 oncologists vs 21 [26.6%] of 79 physicians in other internal medicine subspecialties, 13 [19.4%] of 67 physicians in family or general practice, 31 [17.2%] of 180 physicians in geriatric or general internal medicine, and 4 [13.3%] of 30 physicians in surgery or other). All comparisons were significant (P < 0.01).

Among the doctor-patient relationship variables (such as length of professional relationship, number of recent contacts, and time since last examination), the interval since last examination was important: overpessimistic predictions were associated with the most recent examinations (7.5 days), overoptimistic predictions with the next most recent examinations (13.8 days), and the correct predictions with the longest interval since physical examination (19.5 days; P < 0.05 for these comparisons).

The trichotomous prognosis variable was regressed on patients' age, sex, race, diagnosis, duration of disease, and performance status and on physicians' experience, sex, optimism, board certification, specialty, related practical experience, duration of relationship, number of contacts, and interval since last examination (full results are available on the BMJ website). The model showed that physicians' prognostic accuracy was independent of most patient and physician attributes. After other attributes were adjusted for, however, male patients were 58% less likely to have overpessimistic than correct predictions (odds ratio [OR], 0.42; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.18-0.99). Physicians in the upper quartile of practice experience were 63% less likely to make optimistic rather than correct predictions (OR, 0.37; CI, 0.19-0.74) and 78% less likely to make pessimistic rather than correct predictions (OR, 0.22; CI, 0.08-0.61). Physicians with medical subspecialty training (excluding oncologists) were less than 6 times more likely than geriatricians and general internists to make pessimistic rather than correct predictions (OR, 3.26; CI, 1.01-10.67). As the duration of the doctorpatient relationship increased, so, too, did the physician's odds of making an erroneous prediction. For example, each 1 year longer that the physician had known the patient resulted in a 12% increase in the odds of an overpessimistic prediction (OR, 1.12; CI, 1.02-1.22). Also, as the interval since the last physical examination increased, the odds of a physician making a pessimistic rather than a correct prediction decreased; each day longer resulted in a 3% decrease in the odds (OR, 0.97; CI, 0.94-0.99).

DISCUSSION

Our study of 365 physicians and 504 hospice outpatients found that only 19.7% of prognoses were accurate. Most predictions (63.0%) were overestimates, and physicians overall overestimated survival by a factor of about 5. These prognoses were physicians' best guesses about their patients' survival prospects, objectively communicated to the investigators and not to patients themselves. Close multivariate examination showed that most physician and patient attributes were not associated with prognostic error. The tendency of physicians to make prognostic errors, however, was lower among experienced physicians. Moreover, the better the physician knew the patient—as measured, for example, by the length and recentness of their contact—the more likely the physician was to err.

These findings have several implications. First, undue optimism about survival prospects may contribute to late referral for hospice care, with adverse implications for patients.12,13 Indeed, although physicians state that patients should ideally receive hospice care for 3 months before death,14 patients typically receive only 1 month of such care.15 The fact that physicians have unduly optimistic ideas about how long patients have to live may partly explain this discrepancy. Physicians who do not realize how little time is left may miss the chance to devote more of it to improving the quality of patients' remaining life. Second, to the extent that physicians' implicit or explicit communication of prognostic information affects patients' own conceptions of their future, physicians may contribute to patients making choices that are counterproductive. Indeed, in 1 study, it was found that terminally ill cancer patients who hold unduly optimistic assessments of their survival prospects often request futile, aggressive care rather than perhaps more beneficial palliative care.16 Third, our work hints at corrective techniques that might be used to counteract prognostic error. Disinterested physicians, with less contact with the patient, may give more accurate prognoses, perhaps because they have less personal investment in the outcome.17 Clinicians, therefore, may wish to seek second opinions regarding prognoses, and our work suggests that experienced physicians may be a particularly good source of opinion. Finally, our work suggests that prognostic error in terminally ill patients is uniformly distributed. This has implications for physicians' training and self-assessment because it suggests that there is not one type of physician who is prone to error, nor is there one type of patient in whom physicians are likely to err.

Obtaining prognostic information is often the highest priority for seriously ill patients, eclipsing their interest in treatment options or diagnostic details.18,19 Reliable prognostic information is a key determinant of both physicians' and patients' decision making.16,20,21 Although some error is unavoidable in prognostication, the type of systematic bias toward optimism that we have found in physicians' objective prognostic assessments may be adversely affecting patient care.

Funding: Soros Foundation Project on Death in America Faculty Scholars Program (N A C), the American Medical Association Education and Research Foundation (N A C), and the Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program (E B L)

Competing interests: Both authors have occasionally received honorariums for speaking at events sponsored by hospices.

This article was originally published in BMJ 2000;320:469-473

Elena Linden and Tammy Polonsky helped administer the survey.

Contributors: N A C initiated the study, conceptualized the key questions, oversaw data collection, assisted in data analysis, and cowrote the article. E B L conceptualized the key questions, performed most of the data analysis, and cowrote the article. Both authors will act as guarantors.

References

- 1.Christakis NA, Iwashyna TJ. Attitude and self-reported practice regarding prognostication in a national sample of internists. Arch Intern Med 1998;158: 2389-2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christakis NA. Death Foretold: Prophecy and Prognosis in Medical Care. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1999.

- 3.Christakis NA. The ellipsis of prognosis in modern medical thought. Soc Sci Med 1997;44: 301-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fletcher SW, Fletcher RH, Greganti MA. Clinical research trends in general medical journals, 1946-1976. In: Roberts EB, Levy RI, Finkelstein SN, Moskowitz J, Sondik EJ, eds. Biomedical Innovation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1981.

- 5.Parkes CM. Accuracy of predictions of survival in later stages of cancer. BMJ 1972;2(5804): 29-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heyse-Moore LH, Johnson-Bell VE. Can doctors accurately predict the life expectancy of patients with terminal cancer? Palliat Med 1987;1: 165-166. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Addington-Hall JM, MacDonald LD, Anderson HR. Can the Spitzer Quality of Life Index help to reduce prognostic uncertainty in terminal care? Br J Cancer 1990;62: 695-699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mackillop WJ, Quirt CF. Measuring the accuracy of prognostic judgments in oncology. J Clin Epidemiol 1997;50: 21-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forster LE, Lynn J. Predicting life span for applicants to inpatient hospice. Arch Intern Med 1988;148: 2540-2543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans C, McCarthy M. Prognostic uncertainty in terminal care: can the Karnofsky index help? Lancet 1985;1(8439): 1204-1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zubrod GC, Schneiderman M, Frei E, et al. Appraisal of methods for the study of chemotherapy of cancer in man: comparative therapeutic trial of nitrogen mustard and triethylene thiophosphoramide. J Chron Dis 1960;11: 7-33. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pearlman RA. Inaccurate predictions of life expectancy: dilemmas and opportunities. Arch Intern Med 1988;148: 2537-2538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lynn J, Teno JM, Harrell FM. Accurate prognostication of death: opportunities and challenges for clinicians. West J Med 1995;163: 250-257. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iwashyna TJ, Christakis NA. Attitude and self-reported practice regarding hospice referral in a national sample of internists. J Palliat Med 1998;1: 241-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Christakis NA, Escarce JJ. Survival of Medicare patients after enrollment in hospice programs. N Engl J Med 1996;335: 172-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weeks JC, Cook EF, O'Day SJ, et al. Relationship between cancer patients' predictions of prognosis and their treatment preferences. JAMA 1998;279: 1709-1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poses RM, McClish DK, Bekes C, et al. Ego bias, reverse ego bias, and physicians' prognostic judgments for critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 1991;19: 1533-1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Degner LF, Kristjanson LJ, Bowman D, et al. Information needs and decisional preferences in women with breast cancer. JAMA 1997;277: 1485-1492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blanchard CG, Labrecque MS, Ruckdeschel JC, et al. Information and decision-making preferences of hospitalized adult cancer patients. Soc Sci Med 1988;27: 1139-1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murphy DJ, Burrows D, Santilli S, et al. The influence of the probability of survival on patients' preferences regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation. N Engl J Med 1994;330: 545-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frankl D, Oye RK, Bellamy PE. Attitudes of hospitalized patients toward life support: a survey of 200 medical inpatients. Am J Med 1989;86: 645-648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]