Abstract

Gastric glomus tumors (GGTs) are mesenchymal neoplasms with indolent behavior that originate from the subepithelial layers of the stomach and represent up to 1% of all gastric tumors. GGT is detected incidentally during esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) in a proportion of patients. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) evaluation of GGT is essential to establish the diagnosis and to differentiate it from gastrointestinal stromal tumors or gastric neuroendocrine tumors. An 80-year-old man who presented for abdominal discomfort was incidentally found to have a gastric antral nodule on EGD. Endoscopic biopsy demonstrated moderately erythematous gastric antral mucosa and a 1.5 cm subepithelial lesion along the greater curvature. An EUS revealed a subepithelial 1.6 cm × 1.3 cm isoechoic, homogenous lesion with small calcifications. Immunohistochemical staining of the fine needle biopsy specimen of the nodule was positive for neoplastic cells, smooth muscle actin, vimentin, patchy muscle-specific actin, and synaptophysin. There were no atypical cytologic features. These findings were consistent with GGT. The patient was not deemed to be a candidate for surgical resection due to advanced age and resolution of his symptoms. A shared decision was made to pursue regular surveillance. EUS is essential for evaluation of GGT. Currently, there are no guideline recommendations for surveillance of GGT detected on routine EGD in asymptomatic individuals. A definitive surgical treatment with partial gastrectomy was favored in previously published literature. For asymptomatic patients with GGT or those with resolution of symptoms, careful surveillance with serial abdominal imaging and EUS may be a reasonable option, especially in older patients with poor surgical candidacy.

Keywords: Endoscopic ultrasound, Gastrointestinal tract, Subepithelial tumor, Stomach, Glomus tumor

Introduction

Gastric glomus tumors (GGTs) are rare mesenchymal neoplasms that originate from the subepithelial layers of the stomach, predominantly the antrum, and represent up to one percent of all gastric tumors [1–3]. Most patients present with vague abdominal pain, gastrointestinal bleeding, or perforation [4]. However, GGT is detected incidentally during esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) in a portion of asymptomatic patients [5]. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) evaluation of GGT is essential to establish the diagnosis and guide definitive management. The following case demonstrates the utility of EUS in the evaluation of an incidentally detected GGT and is presented in accordance with the CARE Case Report Guidelines (the completed CARE Checklist is attached as online suppl. material; for all online suppl. material, see https://doi.org/10.1159/000534643).

Case Report

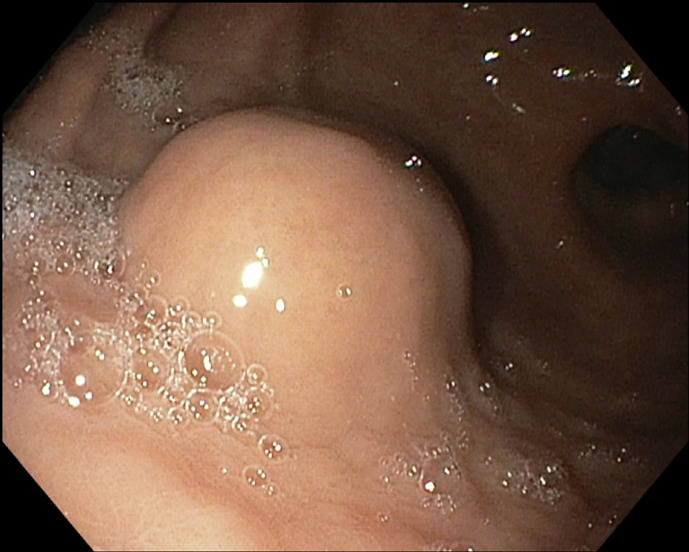

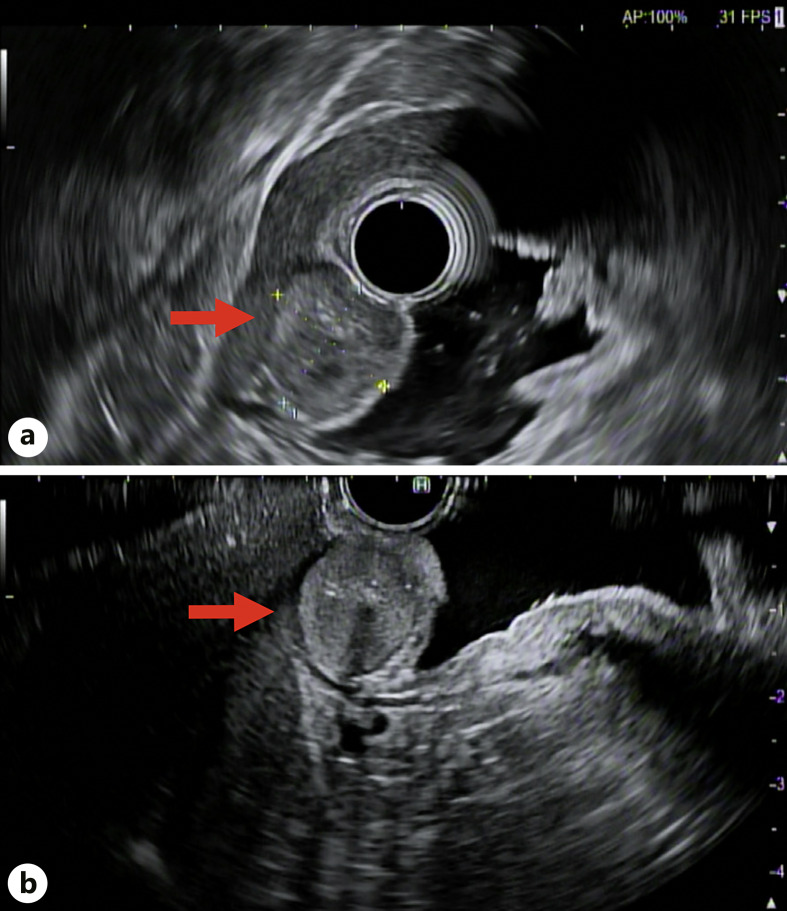

An 80-year-old man with a history of hypertension and benign prostatic hypertrophy presented with abdominal discomfort without weight loss, changes in appetite, melena, or hematochezia. He reported no prior personal history of malignancy or family history of malignancy. His physical examination was negative for reproducible abdominal tenderness or abdominal masses. He was incidentally found to have a gastric antral nodule on EGD. He was started on oral proton pump inhibitor therapy twice daily and referred to an advanced endoscopy center for EUS evaluation of the gastric nodule. Repeat EGD prior to EUS demonstrated benign patchy, moderately erythematous gastric antral mucosa and a 1.5 cm lesion 10 cm from the gastric antrum along the greater curvature (shown in Fig. 1). EUS revealed a subepithelial 1.6 cm × 1.3 cm isoechoic, homogenous lesion with small calcifications on the gastric greater curvature abutting the left hepatic lobe (shown in Fig. 2a, b). EUS-guided fine needle biopsy (FNB) with a 25-gauge needle was performed. Immunohistochemical staining of the biopsy specimen was diffusely positive for neoplastic cells, smooth muscle actin, vimentin, patchy muscle-specific actin, and focal synaptophysin. Cell staining was negative for pancytokeratin, desmin, CD117, DOG1, S100, CK7, CDX-2, Pax-8, HepPar1, and CD34. There were no atypical cytologic features or mitoses. These findings were consistent with GGT. At two-month follow-up, the patient reported his symptoms of abdominal pain had resolved. He was referred to general surgery to discuss surgical resection. A computed topography scan of the abdomen with contrast was obtained to evaluate for additional lesions. Computed topography demonstrated a 2.1 cm × 1.7 cm intraluminal mural mass projecting into the distal stomach lumen without obstruction. A shared decision was made with the patient to proceed with regular surveillance of the GGT rather than surgical resection due to resolution of abdominal pain, lack of features suggesting malignancy, and his advanced age. He agreed to repeat EUS for surveillance in one year.

Fig. 1.

Upper endoscopy of a 15 mm subepithelial lesion along the gastric greater curvature.

Fig. 2.

a, b EUS demonstrating a subepithelial 1.56 cm × 1.28 cm isoechoic, homogenous lesion (red arrow) with small calcifications on the gastric greater curvature abutting the left hepatic lobe.

Discussion

This case illustrates the importance of EUS evaluation of GGT as it allows for characterization of the lesion and the opportunity to obtain biopsy specimens to establish the tissue diagnosis and guide further management [2, 6]. Not only can EUS assist with differentiating GGT from other gastric tumor types, but it also allows for accurate size and depth measurements and evaluation of regional lymphadenopathy for purposes of staging [2]. The differential diagnosis for subepithelial lesions (SELs) of the GI tract includes but is not limited to GGT, gastrointestinal stromal tumors, leiomyoma, neuroendocrine tumor, lymphoma, granular cell tumor, inflammatory fibroid polyp, lipoma, Brunner gland hyperplasia, duplication cyst, pancreatic rests, lymphangioma, and metastasis [3, 7]. Since clinical, radiologic, and endoscopic findings of GGTs are nonspecific, biopsy with subsequent immunohistochemistry is required for definitive diagnosis [5]. Importantly, tissue samples of SELs and lesions involving the muscularis mucosa often cannot be obtained via standard biopsy forceps and require techniques such as unroofing, FNB, submucosal tunneling, or surgery [2]. In this case, FNB allowed for immunohistochemistry testing to be performed, which assisted in the effort to rule out other relatively more common SELs, such as gastrointestinal stromal tumors (negative CD117 and DOG1 consistent with GGT) and neuroendocrine tumors (less extensive synaptophysin positivity with negative CK7, CDX-2, Pax-8 staining consistent with GGT) [3, 8]. Universal features to characterize malignant GGTs have not been established, which complicates decision-making regarding definitive management [9]. However, EUS findings which have been previously identified as being associated with malignancy in gastrointestinal SELs (none of which were present in the patient) include heterogeneous echotexture, large size (greater than 3.0–5.0 cm), and irregular margins [7]. Additional features suggestive of malignancy include deep-seated lesions of size greater than 2.0 cm, atypical mitotic figures, and moderate-to-high nuclear grade [2, 10]. The lack of standardized characteristics of malignancy can create challenges regarding treatment recommendations, requiring a careful analysis of each patient on a case-by-case basis.

Definitive treatment of GGTs with complete resection via endoscopic techniques or laparoscopic partial gastrectomy was favored in previous literature due to the potential risks of malignant transformation [11]. Despite being considered the gold standard for the management of gastric SELs with malignancy potential, laparoscopic surgical resection caries the risk of complications, including intraoperative bleeding, anastomotic stenosis, and dumping syndrome [12]. Owing to the rare nature of GGTs, previous reports documenting the management of GGTs in elderly patients are not widely available. While age alone is not considered a contraindication to laparoscopic procedures, patients of age above 70 years with hypertension were found to have higher rates of postoperative complications in a retrospective analysis of 632 patients who underwent laparoscopic assisted gastrectomy [13]. Although there are many potential endoscopic techniques for resection of gastric SELs, including endoscopic full-thickness resection, endoscopic submucosal dissection, endoscopic submucosal resection, and submucosal tunneling with endoscopic resection, their widespread use has been limited by technical difficulty, availability primarily at specialized centers, and lack of prospective data evaluating efficacy and safety [2, 7, 11]. Additionally, there are several potential complications of these endoscopic techniques when utilized for the management of gastric SELs, including but not limited to bleeding, perforation, and incomplete resection [2, 12]. Recent advances in robotics have paved the way for robot-assisted surgical resection of GGTs. The extent of surgical resection (partial vs. total gastrectomy) depends upon the size, location, and extent of lesions. In complex cases where the tumor is large or if laparoscopic/robotic resection is not feasible, open surgery might be necessary. The choice of surgical management depends upon surgeons’ preferences, feasibility, and availability of local expertise.

Taken together, the lack of definitive criteria to predict malignant transformation of GGTs and the risk of complications associated with laparoscopic or endoscopic resection highlights the necessity of shared decision-making when managing asymptomatic GGTs. For patients of older age who remain asymptomatic, lack suggestive features of malignancy on FNB, and prefer to avoid surgical procedures, EUS surveillance may be an alternative. Suggested intervals for EUS surveillance may be extrapolated from the clinical management algorithm for SELs of the gastrointestinal tract provided by the Standards of Practice Committee of the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, with a surveillance interval of every 3–12 months if asymptomatic [2]. Likewise, patients with lesions involving the muscularis mucosa may benefit from surveillance intervals of closer to three months. This case also draws attention to the need for further efforts to define discrete criteria of GGTs that predict malignant transformation to assist with guiding management of asymptomatic GGTs. Finally, given the paucity of data on the outcomes of elderly patients diagnosed and treated for GGT, every effort to document the clinical courses of patients in this cohort should be made.

GGTs are rare lesions with indolent behavior that typically originate from the subepithelial layers and rarely demonstrate qualities that suggest malignant potential. Currently, there are no guideline recommendations for surveillance of GGTs detected on routine EGD in asymptomatic individuals and/or nonsurgical candidates. For asymptomatic patients with GGT or those with resolution of symptoms, careful EUS surveillance may be a reasonable option. Shared decision-making is essential, especially in older patients with poor surgical candidacy.

Statement of Ethics

Ethical approval is not required for publication of this single case report, in accordance with institutional and national guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for purposes of publication of this case and accompanying images.

Conflict of Interest Statement

There are no conflicts of interest.

Funding Sources

No funding was used in this study.

Author Contributions

Alexander Malik, M.D.: corresponding author, conceptualization, writing – original draft, and writing – review and editing. Muhammad Nadeem Yousaf, M.D., and Sami Samiullah, M.D.: conceptualization and writing – review and editing. Veysel Tahan, M.D.: writing – review and editing.

Funding Statement

No funding was used in this study.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Brotherton T, Khneizer G, Nwankwo E, Yasin I, Giacaman M. Gastric glomus tumor diagnosed by upper endoscopy. Cureus. 2021;13(12):e20703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Standards of Practice Committee; Faulx AL, Kothari S, Acosta RD, Agrawal D, Bruining DH, et al. The role of endoscopy in subepithelial lesions of the GI tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85(6):1117–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sharzehi K, Sethi A, Savides T. AGA clinical Practice update on management of subepithelial lesions encountered during routine endoscopy: expert review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(11):2435–43.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fang H-Q. Clinicopathological features of gastric glomus tumor. WJG. 2010;16(36):4616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Miettinen M, Paal E, Lasota J, Sobin LH. Gastrointestinal glomus tumors: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 32 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26(3):301–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kato S, Kikuchi K, Chinen K, Murakami T, Kunishima F. Diagnostic utility of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy for glomus tumor of the stomach. WJG. 2015;21(22):7052–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jacobson BC, Bhatt A, Greer KB, Lee LS, Park WG, Sauer BG, et al. ACG clinical guideline: diagnosis and management of gastrointestinal subepithelial lesions. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023;118(1):46–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bellizzi AM. Immunohistochemistry in the diagnosis and classification of neuroendocrine neoplasms: what can brown do for you? Hum Pathol. 2020;96:8–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mago S, Pasumarthi A, Miller DR, Saade R, Tadros M. The two challenges in management of gastric glomus tumors, 12. 7th ed. Cureus; 2020. p. e9251. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32821597/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Folpe AL, Fanburg–Smith JC, Miettinen M, Weiss SW. Atypical and malignant glomus tumors: analysis of 52 cases, with a proposal for the reclassification of glomus tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25(1):1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang Y, Zhou P, Xu M, Chen W, Li Q, Ji Y, et al. Endoscopic diagnosis and treatment of gastric glomus tumors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73(2):371–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kang W-M. Laparoscopic-endoscopic cooperative surgery for gastric submucosal tumors. WJG. 2013;19(34):5720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hwang S-H, Joong Park D, Seob Jee Y, Kim HH, Lee HJ, Yang HK, et al. Risk factors for operative complications in elderly patients during laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy. J Am Coll Surgeons. 2009;208(2):186–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.