In the past decade, there has been an increasing awareness of career disparities based on gender, ethnic, socioeconomic, and other diversities. While the proportion of female medical students in Germany has steadily increased to 67% (https://de.statista.com), less than 50% of practicing physicians and only 19–35% of full professors in the medical profession are women.1 A recent study on gender disparity in the neurosurgical specialty reported that women represent 35% of neurosurgery residents and 34% of board-certified neurosurgeons at academic medical centers in Germany but hold only 9% of neurosurgery leadership positions.2 The term “leaky pipeline effect” has been coined for the observation that there is a disproportionally higher drop-out rate of females as opposed to males over the course of an academic medical career. This phenomenon has been described in various medical disciplines, including neuro-oncology.3

In a 2018 survey by the European Association of Neuro-Oncology and the European Organization for Research and Cancer, women were underrepresented in leadership roles as well as in reaching professorship, obtaining third-party funding, establishing research collaborations with pharmaceutical companies, and in serving as principal investigators on clinical trials.4 Similar data emerged in a survey conducted by the “Young Neuro-Onkologische Arbeitsgruppe” (Young NOA) of the German Cancer Society (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, DKG) in 2021.5

In another survey distributed among members of the Society for Neuro-Oncology in 2019, women reported to feel passed over for professional opportunity, to be discriminated in their workplace, and to lack effective mentorship,6 issues that are also reported in racial and ethnic groups in medical professionals.7

With the objective to evaluate the gender distribution in leadership positions among neuro-oncology centers in German-speaking countries (Germany, Austria, and Switzerland; acronym: D-A-CH), we conducted a web-based study. We included DKG-certified neuro-oncology centers (www.oncomap.de) and non-DKG-certified centers with a regular interdisciplinary tumor board. One neuro-oncology leader per center was identified. Leadership positions were defined as “departmental chair,” “leader of neuro-oncology subdivision,” and “other neuro-oncology leader.”

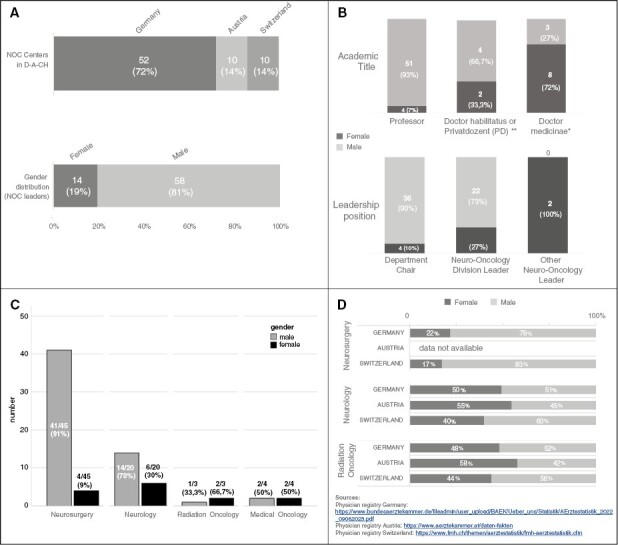

Out of 72 D-A-CH neuro-oncology centers, 52 (72%) were located in Germany, 10 (14%) in Austria, and 10 (14%) in Switzerland. There were 55 DKG-certified and 17 noncertified centers.

Overall, 14 (19%) centers were led by women and 58 (81%) centers were led by men (Figure 1A). Male neuro-oncology leaders were significantly more likely to be professors and to hold a department chair position (4 females [7%] vs. 51 males [93%], P < .001). Women were more likely to lead a subdivision or to not hold a formalized leadership position (Figure 1B). Gender disparity was particularly pronounced among neurosurgeons (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Female versus male neuro-oncology leadership in D-A-CH. (A) Seventy-two neuro-oncology (NOC) centers were identified in D-A-CH and examined in regards to male versus female leadership. (B) Academic rank and leadership roles in male versus female leaders. (C) Gender distribution based on primary specialty. (D) Gender distribution in the most common medical specialties from which neuro-oncologists are recruited. *Doctor medicinae (Dr. med.) and **Doctor habilitatus (Dr. habil.) or Privatdozent (PD) refer to postgraduate degrees at European universities and are necessary to obtain professorship. They represent important steps of the academic ladder in medicine, similar to the academic ranks of assistant professor, associate professor, and full professor at universities in the United States.

While, in general, these results reflect data from previous surveys,4–7 the extent of gender disparity in neuro-oncology leadership within D-A-CH, especially in the top echelon, was remarkable. Not only are the vast majority (81%) of leadership positions held by men, but men are also more likely to be of higher academic rank and to have top leadership roles.

We acknowledge that this observational study is limited in that the data were collected from publicly available web pages that could be outdated or inaccurate. Another source of error may arise from possibly interdependent variables, for example, higher academic rank may correlate with a more advanced leadership role. However, small sample sizes in the subgroups precluded a more detailed statistical analysis. Nevertheless, even with these potential flaws in mind, this study can be perceived as a representative snapshot of the current neuro-oncology leadership landscape in D-A-CH.

The causes of gender disparity in neuro-oncology are certainly complex and insufficiently understood. As the majority of neuro-oncology leaders within D-A-CH are neurosurgeons, one might argue that the pronounced gender gap seen in our study is caused by the persistent female underrepresentation in neurosurgery in German-speaking countries. Indeed, based on the 2022 physician registries in the D-A-CH countries, women represent only 22% and 17% of practicing neurosurgeons in Germany and Switzerland. In contrast, gender distribution appears more balanced in neurology (40–55% females) and radiation oncology (44–58% females, Figure 1 D).8–10 However, there are about three times more neurologists than neurosurgeons in Germany and Switzerland so that neurologists represent the majority in the pool of physicians from which neuro-oncology leaders are recruited. Even if we assume that neurosurgeons may be more likely to specialize in neuro-oncology, the predominance of male neurosurgeons in neuro-oncology leadership roles is still remarkable. While further studies will have to provide additional insights into the intricacies underlying this observation, our results are in line with previous research, and they point to the apparent fact that women experience implicit and explicit biases in the workplace and lack effective mentorship and sponsorship from the outset of their careers.5–7

To address these disparate career opportunities and professional inequities for women in neuro-oncology within D-A-CH, the “Diversity in Neuro-oncology” (DivINe) initiative was implemented as a regular NOA commission in 2021. Through tailored programs, we offer mentorship, peer support, and professional collaborations to female members of the neuro-oncology community. Most recently, we launched DIAMOND, a structured mentorship program with the goal to effectively counterbalance the disparities that women face in their early careers. We envision to establish an effective professional network that supports DivINe and empowers women to reach their full professional potential. The current data will serve as a baseline to assess progress in these ongoing endeavors in D-A-CH in the future.

Contributor Information

Sylvia C Kurz, Department of Neurology & Interdisciplinary Neuro-Oncology, Hertie Institute for Clinical Brain Research, Eberhard-Karls-University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany; Center for Neuro-Oncology, Comprehensive Cancer Center Tübingen-Stuttgart, University Hospital Tübingen, Germany.

Anja Stammberger, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH & Co. KG, Ingelheim, Germany.

Steffen K Rosahl, Health and Medical University, Campus Helios Erfurt, Erfurt, Germany; Department of Neurosurgery, Friedrich-Schiller-University Jena, Jena, Germany.

Lauren E Abrey, InCephalo Therapeutics, Allschwil, Switzerland.

Nathalie L Albert, Department of Nuclear Medicine, LMU University Hospital, Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich, Germany.

Louisa von Baumgarten, Department of Neurology, LMU University Hospital, Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich, Germany.

Jens Gempt, Department of Neurosurgery, University Hospital Hamburg Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany.

Anca-L Grosu, Department of Radiation Oncology, Medical Center, Medical Faculty, Albert-Ludwigs-University Freiburg, Germany.

Verena Leidgens, Novocure GmbH, Munich, Germany.

Anna McLean, Department of Neurosurgery, Jena University Hospital, Jena, Germany.

Mirjam Renovanz, Department of Neurology & Interdisciplinary Neuro-Oncology, Hertie Institute for Clinical Brain Research, Eberhard-Karls-University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany; Center for Neuro-Oncology, Comprehensive Cancer Center Tübingen-Stuttgart, University Hospital Tübingen, Germany; Department of Neurosurgery, Eberhard Karls University Tübingen, Germany.

Julia Schwarzenberger, Novocure GmbH, Munich, Germany.

Lisa Sevenich, Institute for Tumor Biology and Experimental Therapy, Georg-Speyer-Haus, Frankfurt, Germany.

Tadeja Urbanic Purkart, Department of Neurology and Department of Radiology—Division of Neuroradiology, Vascular and Interventional Neuroradiology, Medical University of Graz, Graz, Austria.

Stephanie E Combs, Department of Radiation Oncology, Klinikum rechts der Isar, Technical University of Munich (TUM), Munich, Germany; Helmholtz Zentrum München (HMGU), Oberschleißheim, Germany.

Ghazaleh Tabatabai, Department of Neurology & Interdisciplinary Neuro-Oncology, Hertie Institute for Clinical Brain Research, Eberhard-Karls-University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany; Center for Neuro-Oncology, Comprehensive Cancer Center Tübingen-Stuttgart, University Hospital Tübingen, Germany.

Monika Hegi, Laboratory of Brain Tumour Biology and Genetics, Lausanne University Hospital and University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland.

Martha Nowosielski, Department of Neurology, Medical University Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria.

Conflict of interest statement None declared.

References

- 1. Hofstadter-Thalmann E, Dafni U, Allen T, et al. Report on the status of women occupying leadership roles in oncology. ESMO Open. 2018;3(6):e000423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Forster MT, Behrens M, Lawson McLean AC, et al. Gender disparity in German neurosurgery. J Neurosurg. 2022;136(4):1141–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. James-McCarthy K, Brooks-McCarthy A, Walker DM.. Stemming the “Leaky Pipeline”: an investigation of the relationship between work-family conflict and women’s career progression in academic medicine. BMJ Lead. 2022;6(2):110–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Le Rhun E, Weller M, Niclou SP, et al. Gender issues from the perspective of health-care professionals in neuro-oncology: an EANO and EORTC Brain Tumor Group survey. Neurooncol Pract. 2020;7(2):249–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kebir S, Lazaridis L, Wick W, et al. Gender disparity regarding work-life balance satisfaction among German neuro-oncologists: a YoungNOA survey. Neuro-Oncology. 2022;24(9):1609–1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kumthekar P, Dunbar EM, Peters KB, Brastianos PK, Porter AB.. A broad perspective on evaluating bias in the neuro-oncology workplace. Neuro-Oncology. 2021;23(3):498–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chukwueke UN, Vera E, Acquaye A, et al. SNO 2020 diversity survey: defining demographics, racial biases, career success metrics and a path forward for the field of neuro-oncology. Neuro-Oncology. 2021;23(11):1845–1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. 2022 Physician Registry Germany. https://www.bundesaerztekammer.de/fileadmin/user_upload/BAEK/Ueber_uns/Statistik/AErztestatistik_2022_09062023.pdf. Date accessed August 4, 2023.

- 9. 2022 Physician Registry Austria. https://www.aerztekammer.at/daten-fakten. Date accessed August 4, 2023.

- 10. 2022 Physician Registry Switzerland. https://www.fmh.ch/themen/aerztestatistik/fmh-aerztestatistik.cfm. Date accessed August 4, 2023.