Abstract

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) is a condition characterized by changes in joint formation within the last months of intrauterine life or the first months after birth. Developmental dysplasia of the hip presentation ranges from femoroacetabular instability to several stages of dysplasia up to complete dislocation. Early diagnosis is essential for successful treatment. Clinical screening, including appropriate maneuvers, is critical in newborns and subsequent examinations during the growth of the child.

Infants with suspected DDH must undergo an ultrasound screening, especially those with a breech presentation at delivery or a family history of the condition. A hip ultrasound within the first months, followed by pelvic radiograph at 4 or 6 months, determines the diagnosis and helps follow-up.

Treatment consists of concentric reduction and hip maintenance and stabilization with joint remodeling. The initial choices are flexion/abduction orthoses; older children may require a spica cast after closed reduction, with or without tenotomy. An open reduction also can be indicated. After 18 months, the choices include pelvic osteotomies with capsuloplasty and, eventually, acetabular and femoral osteotomies.

The follow-up of treated children must continue throughout their growth due to the potential risk of late dysplasia.

Keywords: developmental dsysplasia of the hip; hip dislocation, congenital; diagnosis; treatment

Introduction

In developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), 1 different factors alter the development of a joint previously healthy during embryogenesis. These changes probably occur within the last months of intrauterine life or the first months after birth. The disease has a wide spectrum of presentation, ranging from instability with mild acetabular deficiency to complete joint dislocation.

Its dynamic feature causes pre- and postnatal clinical factors that influence its evolution, improving or worsening the condition. The success of the treatment fundamentally depends on early diagnosis, preferably performed up to the 4 th month of life, and achieving concentric reduction and maintenance of the femoral head in the acetabulum.

Teratological congenital dislocations considered atypical are usually associated with syndromes, and their prognosis and treatment deserve an analysis from a different perspective.

Incidence

The incidence of DDH can range from 0.06 to 76.1 per 1,000 live births 2 depending on ethnicity and the assessment method. Ultrasonographic studies describe a higher incidence compared with those based on clinical maneuvers alone. Another critical factor is the age of the child at evaluation. Although some neonatal instabilities resolve spontaneously, 3 hips can become dysplastic over time. Therefore, we understand that a more precise distinction lowers the chance of overtreatment and increases the opportunity to start therapy at the appropriate time.

Unfortunately, Brazil lacks specific data on DDH incidence. Guarniero et al. 4 reported an incidence of 5.01/1,000 using the clinical evaluation of the neonatal Ortolani sign in 9,171 children. Motta et al. 5 described an incidence of 5.45% in neonatal ultrasound evaluation of 1,356 hips. These two studies were performed in maternity hospitals in the city of São Paulo.

Risk Factors

Developmental dysplasia of the hip is probably a disease of multifactorial origin, and we must consider some risk factors for investigation. However, remember that many children, even without defined or known risk factors, can present DDH. Therefore, a careful and accurate assessment, or at least a routine physical examination, is mandatory.

Risk factors include a breech fetal presentation, female gender, primiparous mothers, oligohydramnios, family history of DDH, congenital feet deformities (such as metatarsal adductus, calcaneovalgus feet, and congenital clubfoot), and congenital muscular torticollis. 2 6

The presence of more than one fetus may result in a phenomenon of uterine “agglomeration.” However, most of these children are born with a lower weight, which could reduce the impact of agglomeration. Even so, it is worth remembering that the risk is higher when one of the fetuses is in breech presentation. 7 It appears that prematurity is neither a risk nor a protective factor. 8

Postnatal Factors

Hip positioning within the first few months of life can influence adequate joint development. Certain cultures position the lower limbs of infants in extension and adduction, limiting mobility and increasing the incidence of DDH. 9

Ulzibaati et al. 10 studied the influence of traditional swaddling of newborns in Mongolia with lower limbs restriction in extension and adduction for 20 hours per day during a month. This practice resulted in delayed hip maturation and increased DDH risk. In contrast, cultures in which caregivers carry the infant closer to their bodies and with abducted hips seem to have a decreased incidence of DDH. 9

The “M” positioning of the lower limbs within the first months of life in sling-type carriers with the infant facing the caregiver seems ideal for the healthy development of the hips. In addition, it allows an adequate positioning of the child's pelvis and spine. 9 Siddicky et al. 11 analyzed hip positioning and surface electromyography findings. They reported that a child in a flexible carrier, facing the caregiver, presents hips position and muscle activity similar to that observed with a Pavlik orthosis.

The correct use of slings, mainly in the first 100 days of life, the period of exterogestation, also results in other psychological and sensorial benefits. In these cases, asphyxia is a constant concern, especially in children with no cervical control, implying preventive measures such as correct cervical positioning, keeping the head above the tissue, and protecting the nose and mouth of any obstruction. 12 Other complications can occur, including the possibility of caregiver fall and low back pain.

Ultrasound Screening

The universal ultrasound screening of newborns is controversial because of its high cost. In addition, it requires professional training and predisposes to overtreatment and its complications. On the other hand, the physical examination may not identify some instabilities, resulting in failures in detecting isolated acetabular dysplasia. These failures often occur in children with no identifiable risk factors. 13 However, remember that the complications of a potential overtreatment are relatively small in a properly applied orthosis that respects the safety zones. 14

In children with risk factors but no relevant findings at the physical examination, delaying the ultrasound screening up to 4 or 6 weeks can help distinguish cases of immaturity from those requiring treatment. Preterm infants require a timeframe adjustment to 44 weeks of gestational age. 15

We believe that children with abnormalities at the physical examination and those born in breech presentation with no clinical signs but with affected first-degree relatives must undergo an ultrasound scan. In cases of breech presentation and normal ultrasound findings, we recommend a pelvic radiograph between the 4 th and 6 th months of life due to the risk of missing the diagnosis and the presence of late dysplasia. 16 17 18

Physical Examination

A thorough orthopedic physical examination in search of associated changes is paramount, with special attention to foot deformities and congenital torticollis. 19

All children from the nursery must undergo a physical examination for hip instability. The evaluation should continue in the pediatric follow-up for observation of other signs and symptoms, as the diagnosis of some cases may be a challenge even in experienced hands. 20

For the Ortolani maneuver, 21 the child is in the supine position, with hips flexed at 90 degrees, flexed knees, and adducted thighs. The examiner holds the thighs with the palms of the hands to “embrace” the knees, with the thumb on the medial surface and the second and third fingers over the greater trochanter. The hips are assessed separately by performing maximum abduction. The sign is positive when there is a sensation of impingement of the femoral head and compression on the greater trochanter, producing a noticeable “clunk” or a bump (“scatto”). Thigh adduction results in hip displacement. Gentle traction on the axial axis of the limb can help reduce some hips, especially in older children.

The Barlow maneuver 3 also examines the hips separately. The newborn remains in a supine position with the hips flexed at 90° and fully flexed knees. The thumb of the examiner is on the inner thigh and the third finger is on the greater trochanter of the patient. At first, with a medium abduction, the examiner pressures the greater trochanter. The reallocation of the hip indicates a dislocation. This is the first phase of the maneuver. The second phase applies pressure in the posterior direction with the hip in neutral abduction or slight adduction. A femoral head dislocation followed by spontaneous reduction when relieving the pressure characterizes an unstable hip (positive Barlow maneuver).

The “click” can result from extra-articular causes, including snapping the greater trochanter, the iliopsoas, the knee patella, or the peroneal ankle tendons. However, it warrants a continuous investigation and referral to an orthopedist because its reason is unclear. 22

The limited abduction with flexed hips, that is, a Hart sign, 23 results from the retraction of the adductors. It may occur when the hip is subluxated or dislocated and it usually appears later. The Hart sign is the main clinical sign in children > 3 months or those no longer with instability. Children with abductions < 60 degrees 24 or asymmetrical abductions must undergo imaging tests.

Upon inspection, the presence of asymmetry of the gluteal folds and thigh, despite being observed in some healthy children, is a clinical sign that may indicate inequality or retractions of the muscles of the lower limbs and warrants continuing the investigation. 25

The Galeazzi sign is often late and observed in unilateral cases. The children present claudication when they start to walk. The Trendelenburg sign results from gluteus medius insufficiency in monopodal support and lumbar hyperlordosis, especially in bilateral cases.

Ultrasound

Ultrasonography is an optimal test for DDH diagnosis and follow-up in children up to 4 or 6 months old. The most frequently used method was proposed by Graf. 26 27 It analyzes the hip in the coronal plane, evaluating the bony and cartilaginous roofs, the acetabular appearance, and, in some cases, its stability.

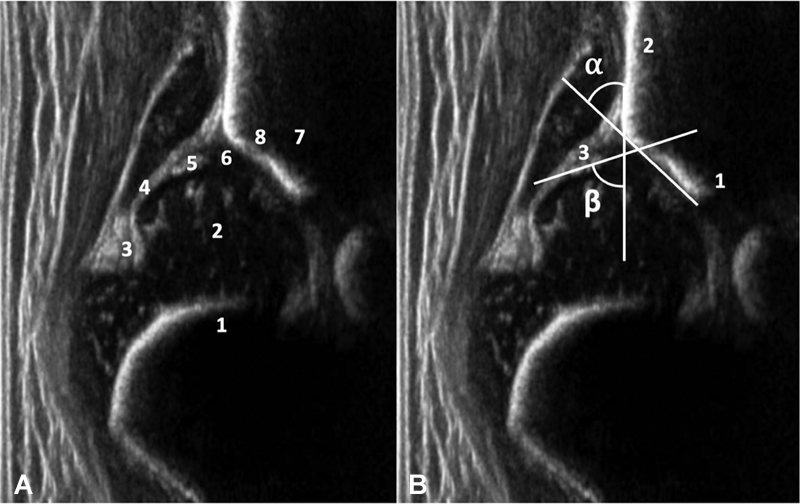

Its accuracy relies on visualizing the following anatomical structures: osteochondral edge, femoral head, synovial fold, joint capsule, acetabular labrum, cartilage, and bony roof and edge, that is, the bone roof turning point (anatomical identification). In addition, the acetabulum must be at the center of a sectional plane, revealing the lower edge of the ilium, its linear echo, and the acetabular labrum (usability check) ( Fig. 1A )

Fig. 1A.

Anatomical identification: 1 osteochondral rim, 2 femoral head, 3 synovial crease, 4 capsule, 5 acetabular labrum, 6 cartilage, 7 bony roof, 8 bony roof tipping point. Fig. 1B Usability check: 1 lower edge of the ilium, 2 straight echo of the ilium bone, and 3 acetabular labrum. Alpha and beta angles measurement.

The bony roof angle, alpha, is between the baseline (ilium) and a line tangent to the bony roof starting at the lower edge of the ilium. The cartilaginous roof angle, beta, is between the baseline and the line from the bony roof tipping point to the center of the acetabular labrum. The three lines rarely intersect at a point ( Fig. 1B ). Ultrasound evaluation must start with an image quality assessment and proceed to the report. Accurate measurement of alpha and beta angles is critical for correct classification and diagnosis 28 ( Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Hips are centralized in Graf types I and II hips; type D (nots hown) is the first stage of decentering, and types III and IV hips are off center.

The percentage of head coverage can be a piece of additional information, but remember that the potential ovoid shape in newborns may hinder interpretation. For Terjesen, 29 a coverage starting at 50% in children > 1 month is normal. Morin, 30 on the other hand, considers a coverage ≥ 58% as consistent with normality.

The medial part of the acetabulum is within an acoustic shadow after the ossification of the secondary nucleus of the femoral head, preventing any accurate measurement. From that moment on, pelvic radiography should base the diagnosis.

An anterior approached ultrasound 31 may also help at the beginning of the treatment for reduction confirmation and follow-up during and after the use of a spica cast.

Radiography

The interpretation of a neonatal hip radiograph can be a challenge. However, from the 6 th month of life onwards, it gets easier, and it is essential for DDH follow-up.

Although some question the radiation from this examination, it does not seem to be associated with a neoplastic risk. 32 A single anteroposterior incidence can be requested to reduce the radioactive dose in follow-up visits. 33 Gonadal protectors are difficult to place in girls. They can be used even though they can hinder the visualization of anatomical parameters. 34

Properly position the radiograph with the limbs in extension. Considering femoral anteversion, the visualization of the femoral neck at its greatest length requires 15 to 20° of medial rotation of the femurs to avoid the false appearance of joint subluxation or coxa valga. In young children, the hand of the examiner holds the knees to compensate for the flexion contracture of the hips. 35

For interpretation, draw the Hilgenreiner line, the Ombrédanne-Perkins line, the Menard and Shenton line, the acetabular index (AI), and the center-edge (CE) angle of Wiberg.

Check the radiograph for errors in pelvis rotation and tilt that could prevent the actual AI measurement. The pelvic rotation quotient 35 is the relation between the transverse diameters of the right and left obturator foramina. Its reference value ranges from 1.8 to 0.56. For the Ball and Komenda pelvic tilt index, divide the vertical diameter of the obturator foramen by the distance between the pubis and the Hilgenreiner line. Its reference value ranges from 0.75 to 1.2. The normal AI depends on the age of the child and on the form of measurement, which can use the acetabular margin 35 or the sourcil 36 as a lateral point. Therefore, we believe that the standardization of measurements is crucial for clinical monitoring.

The Köhler teardrop is often present from the 4 th to 6 th months of life. Its absence from that age onwards may indicate abnormal development of the acetabular cavity. In the case of femoral head lateralization, this sign becomes enlarged or V-shaped. After treatment, it may regain its normal shape, narrow and rounded at the end, due to acetabular remodeling. 35

Treatment

According to the Graf classification, type I hips are healthy, and type IIA (+) are immature. There are controversies regarding the need for treatment of IIA (-) hips (alpha angle < 55° in the 6 th week of life). Most of these hips can evolve to spontaneous resolution. 37 However, girls require special attention due to the persistence of potential dysplasia. 25 Hips classified as IIB, IIC, D, III, and IV require treatment regardless of age.

Developmental dysplasia of the hip treatment requires maintaining a concentric reduction between the femoral head and the acetabulum, positioning the hip in 90 to 110° of flexion and 30 to 65° of abduction while respecting the safety zone. 38

It is important to note that using two or more diapers creates a false sense of security for parents. However, diapers are inefficient in keeping the hips in the correct position. 39 They do not control hip extension and may act as a fulcrum between the lower limbs, functioning as levers for lateralization of the femoral heads. Therefore, this technique is not recommended.

Hip hyperflexion can result in inferior dislocation. Especially in most severe cases, when combined with knee hyperflexion, it can lead to femoral nerve praxis. 40 Femoral neuropraxia leads to a higher rate of treatment failure and complications, particularly if recovery takes longer than 3 days. 41 Excessive abduction causes osteonecrosis (avascular necrosis [AVN]) of the femoral head.

Orthoses

The most used orthosis for DDH treatment is the Pavlik harness, often kept up to the 6 th month of life. The Pavlik harness can reduce neonatal cases with persistent femoral head dislocation. However, this treatment should not occur for > 2 or 3 weeks because of the risk of femoral head vascular compromise and joint deformities resulting from the pressure of the head against the acetabulum.

The anterior straps of this orthosis maintain hip flexion, while the posterior straps limit adduction. Please note that abduction results from a gravitational action and the way the child is carried and that the straps should not force it.

The main error occurs when the anterior straps, which should align with the anterior axillary line, are positioned medially, favoring hip adduction. Another common mistake is to wrap the leg with the strap, which should be just below the popliteal fossa. A strap too close to the ankle causes knee hyperflexion, and an anterior and posterior bowstring mechanism results in inadequate control of the hip position. 42 ( Fig. 3A-B ).

Fig. 3.

A) Correctly positioned Pavlik. B) Pavlik with the anterior harness too medial and the leg strap positioned distally leading to improper positioning of the hips and knees. Adapted from Mubarak S, Garfin S, Vance R, McKinnon B, Sutherland D. Pitfalls in the use of the Pavlik harness for treatment of congenital dysplasia, subluxation, and dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1981;63(8):1239–1248.

In cases with greater instability, the posterior strap can pass through the anterior one before returning to its original position as an auxiliary method. 43

The Tubingen orthosis gains importance from the 3 rd month of life onwards. Abduction control is deemed 44 superior due to the pull-up bar. In addition to preventing excessive abduction, the child can roll over at night and sleep in a lateral position. Its use is controversial in Graf type IV cases. 44 45

The orthoses regimen ranges from 23 to 24 hours per day. It must continue until complete acetabular normalization (Graf type I), which usually occurs in 6 to 12 weeks. The continuation of the treatment for an additional period, as well as weaning, remains a controversial issue, with several protocols. Recently, a comparative study of 1-year-old patients submitted or not to weaning from the Pavlik harness revealed no significant differences in the AI. 46

Reduction and cast

From the 3 rd month of life, in case of orthosis failure or delayed diagnosis of dislocation, we indicate a closed reduction and immobilization in a spica cast in flexion and abduction.

A previous skin traction, rarely performed today, and an adductor longus tenotomy can collaborate in the reduction and increase the safety zone. Older children with high dislocations are more prone to complications such as AVN, dislocation, and residual dysplasia. The absence of ossification of the femoral head nucleus should not delay treatment even though some authors list it as a risk factor for AVN.

A pneumoarthrography can aid the intraoperative evaluation of the reduction, but it is not an essential procedure in all cases. The difficult radiographic interpretation in the postoperative period is attributed to the presence of plaster and to the two-dimensional nature of the assessment. Radiographs in an inlet position can help. 47 Ultrasound follow-up, although feasible, requires a space at the cast for this purpose and an adequate transducer. Computed tomography (CT) is easily accessible and can be performed selectively (with fewer sections) to reduce the amount of radiation. A rapid protocol of nonsedation and noncontrast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is effective for reduction follow-up and detection of joint interpositions. 48 49

The cast is kept for 3 to 4 months and then replaced with an orthosis. The age for this treatment is controversial but it usually considers 18 months as a limit.

We indicate an open reduction via medial or anterolateral approach in children from 9 months old onwards presenting joint interposition or when closed concentric reduction is impossible. A medial approach is an option for young children, usually < 12 months old 50 (maximum age of 18 months old), allowing to address the structures preventing reduction. Its advantage is the cosmetic surgical scar. However, capsuloplasty cannot occur through this approach, and there is a risk of arterial injury. The anterolateral approach has the advantage of not being limited by age. In addition, it can be associated with capsuloplasty, which favors stabilization, 51 avoids greater abduction by the cast, and allows an acetabuloplasty when necessary.

Pelvic Osteotomies

Acetabular remodeling is directly related to stability and age at institution of treatment. It is slower in children > 12 months. From 18 months old onwards, we recommend a pelvic osteotomy with a hip reduction procedure. 52 53

In children with post-treatment residual dysplasia, the decision on the need for pelvic osteotomy is more complex, as the normalization of the acetabular index over time is more likely in hips that are reduced and stable before the age of 2. In a dislocated hip with persistent dysplasia, an MRI can help define the need for intervention according to the appearance and amount of cartilage. 54 55

The surgery proposed by Salter 56 consists of a transverse osteotomy of the ilium in the innominate line to redirect the acetabulum with the fulcrum in the pubic symphysis. It is usually indicated from 18 months to 9 years old. It is possible to obtain coverage of up to 25 degrees anteriorly and 15 degrees laterally. 57 Apparently, there is no acetabular retroversion in the follow-up period. 58

The osteotomy described by Pemberton 59 is incomplete and the triradiate cartilage is its fulcrum. In addition, it can provide anterolateral coverage. This is a good technique when the acetabulum is wide and disproportionate in size to the femoral head because it reduces the diameter and increases the depth of the acetabular cavity.

The osteotomy attributed to Dega was initially described as semicircular, 1 cm proximal to the bone roof, and sparing the medial wall of the ilium to avoid unwanted medialization. A subsequent description reviewed the technique, which became transiliac and had a fulcrum in the intact bone part close to the sciatic notch. 60 The redirection of the acetabulum allows for anterior, lateral, and posterior coverage depending on the positioning of the bone graft. For this reason, it is frequently used in dysplasia with a neuromuscular etiology.

Older children and adolescents with open triradiate cartilage may require further acetabular redirection through triple osteotomies including the ilium, the pubis, and the ischium.

Salvage osteotomies, including the shelf and the Chiari technique, have a role when concentric reduction is not feasible.

The need for femoral shortening, rotation, or both to avoid a varus deformation is an intraoperative decision more frequent in children > 3 years old.

Final Considerations

The prognosis of DDH relates directly to the age of the child at diagnosis. As such, all children must undergo a hip examination for DDH at the nursery and subsequent visits. We suggest establishing a surveillance protocol according to the local reality, aimed at infants with clinical signs, those born in breech presentation, or with affected first-degree relatives.

Guidance on correct postnatal positioning, avoiding “cigar-shaped” bandages, and focusing on physiological positions can play a significant role in maturing hips and preventing late dysplasia.

Hip ultrasound remains the ideal diagnostic test for children up to 4 or 6 months old. Remember, however, that the orthopedist must have experience and training in image evaluation and establish a clinical correlation with the examination report. After the 6 th month of life, due to the probable secondary ossification of the femoral head nucleus, radiography is the optimal test.

Monitor treated children throughout their growth due to the risk of late dysplasia so, if required, they can receive treatment at the appropriate time.

Funding Statement

Suporte Financeiro O presente estudo não recebeu nenhum suporte financeiro de fontes públicas, comerciais, ou sem fins lucrativos.

Financial Support The present study received no financial support from either public, commercial, or not-for-profit sources.

Conflito de Interesses Os autores declaram não haver conflito de interesses.

Estudo desenvolvido no Departamento de Ortopedia e Traumatologia da Santa Casa de Misericórdia de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brasil.

Study developed at the Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology of Santa Casa de Misericórdia de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

Referências

- 1.Musielak B, Idzior M, Jóźwiak M. Evolution of the term and definition of dysplasia of the hip - a review of the literature. Arch Med Sci. 2015;11(05):1052–1057. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2015.52734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loder R T, Skopelja E N. The epidemiology and demographics of hip dysplasia. ISRN Orthop. 2011;2011:238607. doi: 10.5402/2011/238607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barlow T G. Early diagnosis and treatment of congenital dislocation of the hip. Proc R Soc Med. 1963;56(09):804–806. doi: 10.1177/003591576305600920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guarniero R, Montenegro N B, Vieira P B, Peixinho M. Sinal de Ortolani: resultado do exame ortopétido em 9.171 recém-nascidos na Associaçäo Maternidade de Säo Paulo. Rev Bras Ortop. 1988;23(05):125–128. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Motta G GB, Chiovatto A RS, Chiovatto E D, Duarte M L, Rodrigues N VM, Iared W. Prevalence of Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip in a Maternity Hospital in São Paulo, Brazil. Rev Bras Ortop (Sao Paulo) 2021;56(05):664–670. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1736407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Håberg Ø, Foss O A, Lian ØB, Holen K J. Is foot deformity associated with developmental dysplasia of the hip? Bone Joint J. 2020;102-B(11):1582–1586. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.102B11.BJJ-2020-0290.R3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oh E J, Min J J, Kwon S S et al. Breech presentation in twins as a risk factor for developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Pediatr Orthop. 2022;42(01):e55–e58. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000001982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koob S, Garbe W, Bornemann R, Ploeger MM, Scheidt S, Gathen M, Placzek R.Is Prematurity a Protective Factor Against Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip? A Retrospective Analysis of 660 Newborns Ultraschall Med 2022. Apr;4302177–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sidharthan S, Kehoe C, Dodwell E.Post-Natal Positioning through Babywearing: What the Orthopaedic Surgeon Needs to KnowJPOSNA® 2020;2(03). Available from:https://www.jposna.org/ojs/index.php/jposna/article/view/131

- 10.Ulziibat M, Munkhuu B, Bataa A E, Schmid R, Baumann T, Essig S. Traditional Mongolian swaddling and developmental dysplasia of the hip: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pediatr. 2021;21(01):450. doi: 10.1186/s12887-021-02910-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siddicky S F, Wang J, Rabenhorst B, Buchele L, Mannen E M. Exploring infant hip position and muscle activity in common baby gear and orthopedic devices. J Orthop Res. 2021;39(05):941–949. doi: 10.1002/jor.24818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.TASK FORCE ON SUDDEN INFANT DEATH SYNDROME . Moon R Y. SIDS and other sleep-related infant deaths: evidence base for 2016 updated recommendations for a safe infant sleeping environment. Pediatrics. 2016;138(05):e20162940. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Beirne J G, Chlapoutakis K, Alshryda S et al. International Interdisciplinary Consensus Meeting on the Evaluation of Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip. Ultraschall Med. 2019;40(04):454–464. doi: 10.1055/a-0924-5491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biedermann R, Eastwood D M. Universal or selective ultrasound screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip? A discussion of the key issues. J Child Orthop. 2018;12(04):296–301. doi: 10.1302/1863-2548.12.180063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee J, Spinazzola R M, Kohn N, Perrin M, Milanaik R L. Sonographic screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip in preterm breech infants: do current guidelines address the specific needs of premature infants? J Perinatol. 2016;36(07):552–556. doi: 10.1038/jp.2016.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Imrie M, Scott V, Stearns P, Bastrom T, Mubarak S J. Is ultrasound screening for DDH in babies born breech sufficient? J Child Orthop. 2010;4(01):3–8. doi: 10.1007/s11832-009-0217-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brusalis C M, Price C T, Sankar W N. Incidence of acetabular dysplasia in breech infants following initially normal ultrasound: the effect of variable diagnostic criteria. J Child Orthop. 2017;11(04):272–276. doi: 10.1302/1863-2548.11.160261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Antoniak K, Lee C, Goldstein R Y, Abousamra O. Is radiographic imaging necessary for identifying late developmental dysplasia of the hip in breech infants with normal ultrasounds? Glob Pediatr Health. 2021;8:1–5. doi: 10.1177/2333794X211040977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joiner E R, Andras L M, Skaggs D L. Screening for hip dysplasia in congenital muscular torticollis: is physical exam enough? J Child Orthop. 2014;8(02):115–119. doi: 10.1007/s11832-014-0572-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.International Hip Dysplasia Institute (IHDI) . Harper P, Joseph B M, Clarke N MP et al. Even Experts Can Be Fooled: Reliability of Clinical Examination for Diagnosing Hip Dislocations in Newborns. J Pediatr Orthop. 2020;40(08):408–412. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000001602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ortolani M. Un segno poco noto e sua importanza per la diagnosi precoce di prelussazione congenita dell'anca. Paediatria. 1937;45:129–136. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Humphry S, Thompson D, Price N, Williams P R. The ‘clicky hip’: to refer or not to refer? Bone Joint J. 2018;100-B(09):1249–1252. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.100B9.BJJ-2018-0184.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hart V L. Congenital dislocation of the hip in the newborn and in early postnatal life. J Am Med Assoc. 1950;143(15):1299–1303. doi: 10.1001/jama.1950.02910500001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris L E, Lipscomb P R, Hodgson J R. Early diagnosis of congenital dysplasia and congenital dislocation of the hip. Value of the abduction test. J Am Med Assoc. 1960;173:229–233. doi: 10.1001/jama.1960.03020210009003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ömeroğlu H, Tatlici E, Köse N. Significance of Asymmetry of Groin and Thigh Skin Creases in Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip Revisited: Results of a Comparative Study. J Pediatr Orthop. 2020;40(08):e761–e765. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000001531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Graf R. Fundamentals of sonographic diagnosis of infant hip dysplasia. J Pediatr Orthop. 1984;4(06):735–740. doi: 10.1097/01241398-198411000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graf R, Lercher K, Scott S, Spieß T. São Paulo: Pasavento; 2021. Fundamentos da ultrassonografia do quadril infantil: segundo a técnica de Graf. Tradução de Giovanna Braga Motta e Susana dos Reis Braga. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sari A S, Karakus O. Is experience alone sufficient to diagnose developmental dysplasia of the hip without the bony roof (alpha angle) and the cartilage roof (beta angle) measurements?: A diagnostic accuracy study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99(14):e19677. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000019677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Terjesen T. Ultrasound as the primary imaging method in the diagnosis of hip dysplasia in children aged < 2 years. J Pediatr Orthop B. 1996;5(02):123–128. doi: 10.1097/01202412-199605020-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morin C, Harcke H T, MacEwen G D. The infant hip: real-time US assessment of acetabular development. Radiology. 1985;157(03):673–677. doi: 10.1148/radiology.157.3.3903854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Douveren F Q, Pruijs H E, Sakkers R J, Nievelstein R A, Beek F J. Ultrasound in the management of the position of the femoral head during treatment in a spica cast after reduction of hip dislocation in developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85(01):117–120. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.85b1.12665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bone C M, Hsieh G H. The risk of carcinogenesis from radiographs to pediatric orthopaedic patients. J Pediatr Orthop. 2000;20(02):251–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hudak K E, Faulkner N D, Guite K et al. Variations in AP and frog-leg pelvic radiographs in a pediatric population. J Pediatr Orthop. 2013;33(02):212–215. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e31827e8fda. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumar A, Chau W W, Hung A L, Wong J K, Ng B KW, Cheng J CY. Gonadal shield: is it the Albatross hanging around the neck of developmental dysplasia of the hip research? J Child Orthop. 2018;12(06):606–613. doi: 10.1302/1863-2548.12.180133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tönnis D. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1987. Congenital dysplasia and dislocation of the hip in children and adults. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Novais E N, Pan Z, Autruong P T, Meyers M L, Chang F M. Normal percentile reference curves and correlation of acetabular index and acetabular depth ratio in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2018;38(03):163–169. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000000791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roovers E A, Boere-Boonekamp M M, Mostert A K, Castelein R M, Zielhuis G A, Kerkhoff T H. The natural history of developmental dysplasia of the hip: sonographic findings in infants of 1-3 months of age. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2005;14(05):325–330. doi: 10.1097/01202412-200509000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ramsey P L, Lasser S, MacEwen G D. Congenital dislocation of the hip. Use of the Pavlik harness in the child during the first six months of life. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976;58(07):1000–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Pellegrin M, Damia C M, Marcucci L, Moharamzadeh D. Double Diapering Ineffectiveness in Avoiding Adduction and Extension in Newborns Hips. Children (Basel) 2021;8(03):179. doi: 10.3390/children8030179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sierra-Silvestre E, Bosello F, Fernández-Carnero J, Hoozemans M JM, Coppieters M W. Femoral nerve excursion with knee and neck movements in supine, sitting and side-lying slump: An in vivo study using ultrasound imaging. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2018;37:58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.msksp.2018.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murnaghan M L, Browne R H, Sucato D J, Birch J. Femoral nerve palsy in Pavlik harness treatment for developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(05):493–499. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mubarak S, Garfin S, Vance R, McKinnon B, Sutherland D. Pitfalls in the use of the Pavlik harness for treatment of congenital dysplasia, subluxation, and dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63(08):1239–1248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maclean J G, Hawkins A, Campbell D, Taylor M A. A simple modification of the Pavlik harness for unstable hips. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25(02):183–185. doi: 10.1097/01.bpo.0000149865.42777.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lyu X, Chen T, Yang Z et al. Tübingen hip flexion splint more successful than Pavlik harness for decentred hips after the age of three months. Bone Joint J. 2021;103-B(05):991–998. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.103B5.BJJ-2020-1946.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ran L, Chen H, Pan Y, Lin Q, Canavese F, Chen S. Comparison between the Pavlik harness and the Tübingen hip flexion splint for the early treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2020;29(05):424–430. doi: 10.1097/BPB.0000000000000667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bram J T, Gohel S, Castañeda P G, Sankar W N. Is There a Benefit to Weaning Pavlik Harness Treatment in Infantile DDH? J Pediatr Orthop. 2021;41(03):143–148. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000001753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Massa B SF, Guarniero R, Godoy R M, Jr, Rodrigues J C, Montenegro N B, Cordeiro F G. Use of inlet radiographs in the assessment of reduction after the surgical treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip. Bone Joint J. 2017;99-B(05):697–701. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.99B5.37687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ranawat V, Rosendahl K, Jones D. MRI after operative reduction with femoral osteotomy in developmental dysplasia of the hip. Pediatr Radiol. 2009;39(02):161–163. doi: 10.1007/s00247-008-1071-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosenbaum D G, Servaes S, Bogner E A, Jaramillo D, Mintz D N. MR imaging in postreduction assessment of developmental dysplasia of the hip: goals and obstacles. Radiographics. 2016;36(03):840–854. doi: 10.1148/rg.2016150159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Herring J A.Developmental Dysplasia of the hip In: Tachdjian's pediatric orthopaedics: from the Texas Scottish Rite Hospital for Children. 5 th ed. Philapdelphia: Elsevier; 2014483–579. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kotlarsky P, Haber R, Bialik V, Eidelman M. Developmental dysplasia of the hip: What has changed in the last 20 years? World J Orthop. 2015;6(11):886–901. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v6.i11.886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lindstrom J R, Ponseti I V, Wenger D R. Acetabular development after reduction in congenital dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1979;61(01):112–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kothari A, Grammatopoulos G, Hopewell S, Theologis T. How does bony surgery affect results of anterior open reduction in walking-age children with developmental hip dysplasia? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474(05):1199–1208. doi: 10.1007/s11999-015-4598-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wakabayashi K, Wada I, Horiuchi O, Mizutani J, Tsuchiya D, Otsuka T. MRI findings in residual hip dysplasia. J Pediatr Orthop. 2011;31(04):381–387. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e31821a556e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Walbron P, Müller F, Mainard-Simard L, Luc A, Journeau P. Bone maturation of MRI residual developmental dysplasia of the hip with discrepancy between osseous and cartilaginous acetabular index. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2019;28(05):419–423. doi: 10.1097/BPB.0000000000000581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Salter R B. Innominate osteotomy in the treatment of congenital hip dislocation and subluxation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1961;43(03):518–539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rab G T.Biomechanical aspects of Salter osteotomy Clin Orthop Relat Res 1978(132):82–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Airey G, Shelton J, Dorman S, Bruce C, Wright D M. The Salter innominate osteotomy does not lead to acetabular retroversion. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2021;30(06):515–518. doi: 10.1097/BPB.0000000000000821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pemberton P A. Pericapsular osteotomy of the ilium for treatment of congenital subluxation and dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1965;47:65–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Czubak J, Kowalik K, Kawalec A, Kwiatkowska M. Dega pelvic osteotomy: indications, results and complications. J Child Orthop. 2018;12(04):342–348. doi: 10.1302/1863-2548.12.180091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]