Abstract

The utilization of thermally activated delayed fluorescence (TADF) materials in highly proficient organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) has attracted much attention. Based on TADF material TPA-QNX(CN)2, a series of three-dimensional donor-acceptor (D-A) triptycenes have been designed via structural modification of D-fragment. The influences of different D-fragments with various electron-donating strengths on the singlet-triplet energy gap (ΔEST), emission wavelength (λem), and electron/hole reorganization energy (λe/λh) are extensively studied by applying density functional theory (DFT) coupled with time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT). The computed results imply that as the electron-donating strength of the D-fragments increases, the ΔEST value decreases and λem is red-shifted for the molecules using the same acceptor units. Analogously, the 1CT‒3CT state splitting (ΔEST (CT)) is also decreased by enlarging the twist angle (β) between the phenyl ring and alternative D-fragment. Therefore, efficient color tuning within a broad emission range (434–610 nm), as well as small ΔEST (CT) values (0.01–0.05 eV), has been accomplished by structural modification of the D-fragments. The greater electron-donating strength, the smaller ΔEST, and the smaller λh for PPXZ-QNX(CN)2 make it the best candidate among all the designed molecules.

Keywords: Triptycenes, Thermally activated delayed fluorescence, Singlet-triplet energy gap, Optimal Hartree-Fock, Density functional theory, Time-dependent density functional theory

1. Introduction

Since the first report by Chihaya Adachi and coworkers in 2009 [1,2], the utilization of thermally activated delayed fluorescence (TADF) materials in highly proficient organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) has attracted much attention [[3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9]]. Through the efficient reversible inter-system crossing (RISC) method from the lowest triplet (T1) to the lowest singlet (S1) excited state combined with fluorescence from the S1 state, TADF materials can harvest nearly 100 % non-radiative triplet excitons for light emission [[10], [11], [12], [13], [14]]. However, the RISC generally increases with decreasing energy gap (ΔEST). Thus, a small ΔEST plays a main role in TADF, which can be realized by splitting the spatial partition of the highest occupied molecular orbitals (HOMOs) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbitals (LUMOs) [[15], [16], [17], [18], [19]]. A typical approach adopted to achieve the spatially partitioned HOMO-LUMO is to employ a D-A system, among which D and A are directly connected with twisted geometry [[20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26]].

However, recently Swager [27] and co-workers have found an alternative approach to create small ΔEST values for TADF materials with a through-space interaction in D-A triptycenes. Triptycenes are a group of structurally distinct chemical compounds made up of isolated aromatic rings separated by bicycle [2.2.2] octatriene bridgeheads. The homoconjugation between HOMO-LUMO on different fins of the three-dimensional D-A triptycenes was estimated to be around 20–30 % of the regular conjugation [28]. Thus, the relatively small intramolecular orbital overlap realized by homoconjugation endows D-A triptycenes a small ΔEST and TADF characteristics. Moreover, the intrinsically high thermal stability displayed by many triptycene derivatives is a key factor for OLED manufacturing and operation. Two D-A triptycenes including TPA-QNX(CN)2 and TPA-PRZ(CN)2 designed by Swager and co-workers [27] showed smaller ΔEST values (0.111 and 0.075 eV, respectively) and blue-green fluorescence. OLEDs engineered employing these two molecules as emitters exhibit electroluminescence with high efficiencies, especially for TPA-QNX(CN)2 with an external quantum efficiency (EQE) value of 9.4 %. Hence, it is keenly anticipated to tune the emission color of the novel triptycenes TADF emitters for a wider application in OLEDs by further modifying their structures.

In this study, using TPA-QNX(CN)2 as the parental compound, a series of substituted derivatives were devised by changing the D-moiety to tune the emission color. As shown in Fig. 1, all the designed molecules, PhCz-QNX(CN)2, PPXZ-QNX(CN)2, and DMPA-QNX(CN)2 have the same dicyanoquinoxaline (QNX(CN)2) acceptor unit, but different D-units including the N-phenylcarbazole (PhCz), N-phenylphenoxazine (PPXZ) and 9,9-dimethyl-10-phenylacridine (DMPA).

Fig. 1.

Structures of the parent molecule TPA-QNX-(CN)2 and the substituted derivatives.

2. Computational methodology

To calculate the ground state (S0) and excited state geometries (S1) of these triptycene derivatives, we employed DFT and TD-DFT calculations, respectively. The S0 geometry optimization of TPA-QNX(CN)2 was carried out with B3LYP [[29], [30], [31], [32]] exchange-correlation functional and 6-31G* [33,34] basis set by Swager and co-workers applying Q-Chem 4.1 software as shown in Table S1 [12]. However, five more different functionals were employed to perform the same optimization to get the correct structure geometry for TPA-QNX(CN)2, including TPSSh [35], PBE0 [36], M06-2X [37], ωB97XD [38] and CAM-B3LYP [39]. The main calculated structural parameters of TPA-QNX(CN)2 were listed in Table S2, together with their difference values deviating from the comparable crystallographic data. It is seen that the M06-2X functional provided more reasonable descriptions of the molecular structure. Thus, M06-2X functional with a 6-31G* basis set was particularly efficient to reproduce the S0 state geometries of the investigated molecules.

We know the S1 state optimization for intramolecular-charge-transfer (ICT) molecules is susceptible to Hartree-Fock percentage (HF%) in exchange-correlation functionals (XC). Neglecting the long-range columbic attraction for non-hybrid functionals underestimates the CT transition energies while the electron correlation problems of pure HF functionals overestimate the excited energy. In the end, the configuration interaction description (CI) of the S1 transitions as well as the vertical absorption and emission energy (EVA and EVE) calculation also strongly depend on the XC functional [9,40,41]. Given that the optimal HF% (OHF) is ascertained by the charge transfer amount (q) from the D to A part by an empirical relationship of OHF = 42q, the Multiwfn software [42] was employed to calculate the q values based on HOMO-LUMO dispersion [[43], [44], [45]]. Based on S0 geometry, the vertical absorption energies for singlet EVA (S1) as well as triplet EVA (T1) were computed using TD-DFT. Different functionals including B3LYP, PBE0, MPW1B95 [46], BMK [47], M06-2X and M06-HF [48] having different HF% of 20 %, 25 %, 31 %, 42 %, 54 % and 100 %, respectively, were employed with 6-31G* basis set. Afterward, the vertical excitation energy EVA (S1, OHF) was determined from the best fit straight line of the double log plots of EVA (S1, T1) against HF% as seen in Fig. 2, S1, and S2 [49]. Then we calculated the zero-zero transition energy (E0-0) as well as ΔEST values according to the given formulae of Adachi et al. as follows [49,50].

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

Fig. 2.

Dependence of vertical absorption energy for singlet (EVA (S1)) and triplet (EVA (T1)) on the HF% in TD-DFT for the parent as well as substituted molecules plotted on a log-log scale. 1CT, 3CT, 1LE and 3LE represent charge transfer singlet, charge transfer triplet, locally excited singlet and locally excited triplet states, respectively.

Here, stokes-shift energy (ΔEstokes) loss is supposed as 0.09 eV, and the vibrational energy level difference between zero-zero transition (E0-0) and vertical transition (ΔEV) is around 0.15 eV for conjugated molecules. Parameter C is the correction factor whose value is 1.10 (BMK), 1.18 (M06-2X), and 1.30 (M06-HF), respectively. Afterward, the S1 state geometries were optimized via functional having HF% value close to the OHF (%) value. The BMK functional was selected for S1 state geometry optimization for all the studied compounds as the OHFs were determined to be closest to 42 % as seen in Table 1. The result of emission wavelengths (λem) calculated via the traditional method using different DFT functionals is also displayed in Fig. S3 just for the comparison of the two methods.

Table 1.

Calculated EVA (S1), EVA (T1), CT amount (q), OHF%, E0-0 (1CT), E0-0 (3CT) and E0-0 (3LE) of the studied molecules based on M06-2X optimized geometries employing 6-31G* basis set and various exchange-correlation functionals.

| Parameter | Functional | TPA-QNX(CN)2 | PhCz-QNX(CN)2 | PPXZ-QNX(CN)2 | DMPA-QNX(CN)2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

EVA (S1) (eV) |

B3LYP | 2.2457 | 2.4333 | 1.7801 | 1.9485 |

| PBE0 | 2.4381 | 2.6595 | 2.0131 | 2.1730 | |

| MPW1B95 | 2.6452 | 2.8906 | 2.2819 | 2.4317 | |

| BMK | 3.0395 | 3.3440 | 2.7769 | 2.9213 | |

| M06-2X | 3.4347 | 3.7041 | 3.2931 | 3.4195 | |

| M06-HF | 3.6835 | 3.6829 | 3.6761 | 3.6796 | |

|

EVA (T1) (eV) |

B3LYP | 2.1491 | 2.3933 | 1.7760 | 1.9449 |

| PBE0 | 2.3281 | 2.6084 | 2.0081 | 2.1686 | |

| MPW1B95 | 2.5331 | 2.8329 | 2.2772 | 2.4273 | |

| BMK | 2.9042 | 3.1379 | 2.7700 | 2.9140 | |

| M06-2X | 3.2423 | 3.2905 | 3.2532 | 3.2853 | |

| M06-HF | 3.2843 | 3.2775 | 3.2697 | 3.2739 | |

|

E0-0 (3LE) (eV) |

M06-2X | 2.66 | 2.70 | 2.67 | 2.69 |

| M06-HF | 2.44 | 2.43 | 2.43 | 2.43 | |

| Average | 2.55 | 2.56 | 2.55 | 2.56 | |

| CT amount (q) | 0.873 | 0.880 | 0.886 | 0.888 | |

| OHF% | 37 | 37 | 37 | 37 | |

| EVA (S1, OHF) (eV) | 2.87 | 3.13 | 2.57 | 2.72 | |

| E0-0 (1CT) (eV) | 2.63 | 2.89 | 2.33 | 2.48 | |

| E0-0 (3CT) (eV) | 2.51 | 2.84 | 2.32 | 2.47 | |

Based on optimized S0 and S1 state geometries, the absorption wavelengths (λab), as well as emission wavelengths (λem), were computed, respectively, using the BMK/6-31G* theory in cyclohexane solvent employing polarized continuum model (PCM) [51]. Besides, the electron-hole distributions of the S1 state for these molecules were analyzed using Multiwfn software to realize the transition character of the hole and electron as displayed in Fig. S7. The main calculations are performed with the Gaussian-09 package [52].

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Molecular geometries

For the optimized S0 and S1 state geometries, geometrical parameters like bond length between atoms 25 and 31 (l1, or l2 between atoms 26 and 32) and twisting angle between atoms 23, 25, 31, and 33 (β1, or β2 between atoms 24, 26, 32 and 34) are portrayed in Fig. 3 and are recorded in Table 2. The S0 state-optimized geometries of these investigated compounds are also illustrated in Fig. S4. In the S0 geometry, it's interesting to find that the twisting angles (β1 and β2) enlarge with the increase of the rigidity for the alternative D-fragment. The β1/β2 values for the designed molecules PhCz-QNX(CN)2, PPXZ-QNX(CN)2, and DMPA-QNX(CN)2 are 51.8°, 80.1°, and 88.8°, respectively, larger than that of the parent molecule (36.5°). It can be inferred that the designed substituents will have slightly less orbital overlap between D-A fragments than the parent molecule does. The larger twisting angle for DMPA-QNX(CN)2 and PPXZ-QNX(CN)2 is because of steric hindrance caused by bulky substituents/atoms on the ring. This twisting angle helps alleviate repulsive forces and allows the molecule to adopt a more stable conformation. The smaller twisting angle in PhCz-QNX(CN)2 is due to relatively lower steric hindrance, and mild strain making it energetically more favorable for the molecule to adopt a relatively planar conformation.

Fig. 3.

The l1, l2, β1, and β2 for the investigated molecules at their S0 and S1 states. Color code: gray (carbon), blue (nitrogen) and white (hydrogen). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Table 2.

Calculated twisting angles (β1 and β2) and bond lengths (l1 and l2) of all the investigated compounds in S0 and S1 optimized geometries.

| Molecule | S0 geometry |

S1 geometry |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| l1 (l2) (Å) | β1 (β2) (°) | l1 (l2) (Å) | β1 (β2) (°) | |

| TPA-QNX(CN)2 | 1.41 | 36.5 | 1.41 | 39.4 |

| PhCz-QNX(CN)2 | 1.41 | 51.8 | 1.41 | 49.8 |

| PPXZ-QNX(CN)2 | 1.43 | 80.1 | 1.44 | 84.9 |

| DMPA-QNX(CN)2 | 1.43 | 88.8 | 1.44 | 85.0 |

As shown in Table 2, the l1/l2 differences of all the investigated compounds between the S0 and S1 states are within 0.01 Å, while the β1/β2 differences between the S0 and S1 states are below 5°, indicating the possibility of effectively non-radiative decay suppression from S1 → S0.

3.2. Frontier molecular orbitals (FMOs)

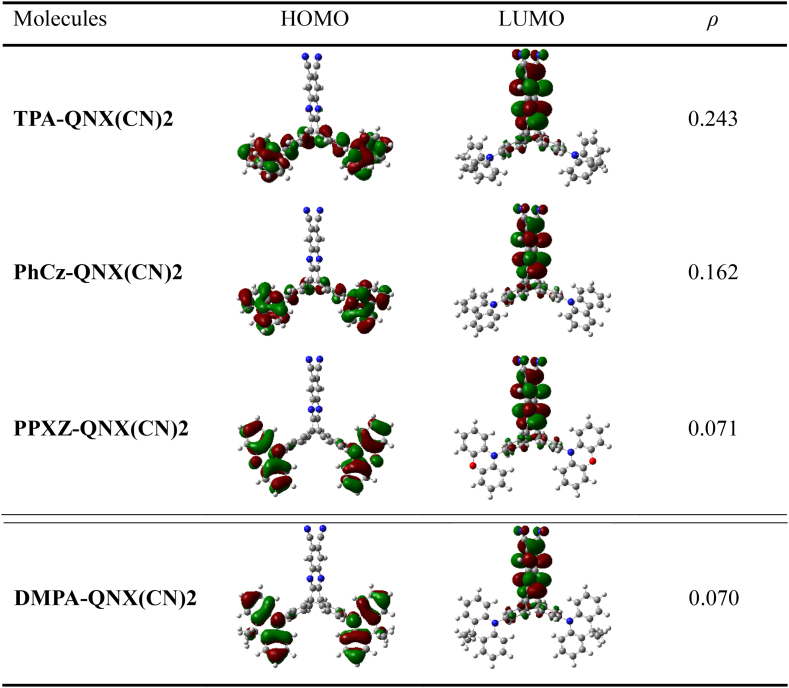

The FMOs are recognised to give important information regarding the TADF nature. We have illustrated, in Fig. 4, the HOMO-LUMO electron density plots in the S0 states. The HOMO-LUMO overlap (ρ) was computed using Becke's grid-based integration method using a given formula in the Multiwfn software [42].

| (4) |

Fig. 4.

The HOMO-LUMO electron density plots and the overlap between them in whole space for these investigated compounds in the S0 states.

As is obvious, the LUMOs are predominantly dispersed on the A-moiety while the HOMOs are chiefly localized on the D-moiety. The HOMO distribution on the phenyl rings of the D-moiety is decreasing in the order of TPA-QNX(CN)2 > PhCz-QNX(CN)2 > PPXZ-QNX(CN)2 > DMPA-QNX(CN)2, on account of more twisting geometries of the molecules. Notably, this rule is also applicable for the calculated orbital overlap ρ, suggesting smaller ΔEST values of designed molecules compared with parent molecule TPA-QNX(CN)2.

To support the impact of HOMO-LUMO separations, we have also explored the density of state (DOS) spectrum and population analysis as shown in Fig. S5, Tables S3, S4, and S5). We know that the D-fragments possessing higher energy levels of the HOMO tend to be more electron-donating [23,53,54]. The HOMO energy levels (EHOMO) of the separate D-fragments and the HOMO-LUMO energy gaps (ΔEH–L) of the corresponding molecules are shown in Fig. 5. As shown by the EHOMO energy levels of the D-fragments, following the sequence: PPXZ > DMPA > TPA > PhCz, the electron-donating strength also follows the same order. Similarly, the ΔEH–L of the studied molecules follow the same tendency as the electron-donating strength of the corresponding individual D-moiety both in the S0 state and S1 state: PPXZ-QNX(CN)2 > DMPA-QNX(CN)2 > TPA-QNX(CN)2 > PhCz-QNX(CN)2: (shown in Fig. 5 and S6). The import of D-fragments with different electron-donating strengths may affect the λab and λem spectra of the investigated molecules since △EH-L is connected to the λab and λem. In general, the greater the electron-donating strength of the Donor, the smaller the △EH-L which corresponds to longer wavelengths.

Fig. 5.

The energy levels of the HOMOs and LUMOs for the individual D-fragments and the corresponding molecules in the S0 states.

3.3. Singlet-triplet energy gap

Using the Multiwfn program, the E0-0 (S1), E0-0 (3CT), as well as E0-0 (3LE) are attained based on the computed q values (Table 1). At first, double log plots of EVA (S1) versus HF% for the compounds under investigation were plotted (Fig. 2). Then the E0-0 (S1), E0-0 (3CT), as well as E0-0 (3LE) of these designed substituents were computed using equations (1), (2), (3) as seen in Table 3. The hole-electron distributions for the S1 state, calculated via Multiwfn software, confirmed that the S1 states of all the compounds are 1CT in nature as displayed in Fig. S7. To further confirm the charge transfer nature of S1 states and electronic excitation processes, we have shown the transition density matrix maps as in Fig. S8. The computed E0-0 (3CT) state and E0-0 (3LE) states turn out to have the least energy levels when discussing the lowest T1 state [40]. The 1CT-3CT splitting is denoted by ΔEST (CT), while the difference of energy between the lowest T1 and S1 state is denoted by ΔES1-T1 [31,55]. Table 3 shows that the T1 states for TPA-QNX(CN)2, PPXZ-QNX(CN)2, and DMPA-QNX(CN)2 are all 3CT states, which is beneficial for effective RISC. While for PhCz-QNX(CN)2, the T1 state is a 3LE state, 0.28 eV lower than E0-0 (3CT). The calculated ΔEST (CT) value using the optimal HF method for TPA-QNX(CN)2 is 0.12 eV, which is not far from the 0.11 eV as estimated by Swager et al. While ΔEST (CT) values for the designed molecules PhCz-QNX(CN)2, PPXZ-QNX(CN)2, and DMPA-QNX(CN)2 are 0.05, 0.01, and 0.01 eV, respectively. Their much smaller ΔEST (CT) values than that of the parent molecule suggested they are superior candidates for TADF materials. Even though PhCz-QNX(CN)2 has a lower 3LE state, reverse internal conversion from the 3LE state → the 3CT state, followed by a RISC from the 3CT state → the 1CT state, can result in the efficient TADF process [56,57]. The extremely small ΔEST (CT) values for the designed molecules result from the small orbital overlap (0.070–0.162) between HOMOs and LUMOs. That is to say, the introduction of more rigid fragments to the D-moiety accounts for enlarged β values and efficient HOMO-LUMO separation, hence smaller ΔEST values.

Table 3.

Calculated ΔEST (CT) as well as ΔES1-T1 values for the studied molecules.

| Molecules | E0-0 (1CT) (eV) | E0-0 (3CT) (eV) | E0-0 (3LE) (eV) | ΔEST (CT) (eV) |

ΔES1-T1 (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPA-QNX(CN)2 | 2.63 | 2.51(T1) | 2.55 | 0.12 | 0.12 |

| PhCz-QNX(CN)2 | 2.89 | 2.84 | 2.56(T1) | 0.05 | 0.33 |

| PPXZ-QNX(CN)2 | 2.33 | 2.32(T1) | 2.55 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| DMPA-QNX(CN)2 | 2.48 | 2.47(T1) | 2.56 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

It is noted that the order of the ΔES1-T1 values for these investigated molecules is as follow: PhCz-QNX(CN)2 > TPA-QNX(CN)2 > PPXZ-QNX(CN)2 = DMPA-QNX(CN)2. With increased electron-donating strength of D-units, the ΔES1-T1 value therefore drops. As a result, using strong electron-donating fragments as the D-units helps to increase the 3LE energy levels and decrease ΔES1-T1 values.

3.4. Optical properties

The absorption (λab) as well as emission wavelengths (λem) of the investigated molecules computed at the TD-BMK/6-31G* level under cyclohexane solvent using the PCM model are listed in Table 4, S6 and are portrayed in Fig. 6. The calculated λab and λem values for TPA-QNX(CN)2 are 417 and 507 nm which are close to the experimental values of 428 and 487 nm, respectively. The designed molecules showed λem peaks lying in the range of 434–610 nm with LUMO → HOMO transition ranging from 97 to 99 %. Owing to its lower electron-donating strength, PhCz-QNX(CN)2 exhibits a blue emission centered at 434 nm with a hypsochromic-shift of about 73 nm compared with that of parent molecule TPA-QNX(CN)2. However, due to the higher electron-donating strength of PPXZ-QNX(CN)2, the λem of this material (610 nm) was red-shifted by approximately 103 nm in comparison to that of TPA-QNX(CN)2. The DMPA-QNX(CN)2 (518 nm) shows green emission with a slight bathochromic-shift of about 11 nm. Moreover, the sequence of λab, as well as λem values, also agrees with the trend of the electron-donating strength of the D-fragments in the S0 and S1 states, respectively, suggesting an alternative way to tune the emission wavelength of molecules.

Table 4.

Calculated absorption (λab), and emission wavelength (λem) and main configuration of all the molecules.

| Molecules | Absorption |

Emission |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| λab (nm) | Main CI expansion/coefficient | λem (nm) | Main CI expansion/coefficient | |

| Exp. | 428 | 487 | ||

| TPA-QNX(CN)2 | 417 | HOMO→LUMO (0.97) | 507 | LUMO→HOMO (0.98) |

| PhCz-QNX(CN)2 | 371 | HOMO→LUMO (0.96) | 434 | LUMO→HOMO (0.97) |

| PPXZ-QNX(CN)2 | 437 | HOMO→LUMO (0.98) | 610 | LUMO→HOMO (0.99) |

| DMPA-QNX(CN)2 | 419 | HOMO→LUMO (0.98) | 518 | LUMO→HOMO (0.99) |

Fig. 6.

Absorption and emission wavelengths (λab and λem) of all the studied molecules computed at the TD-BMK/6-31G* level under cyclohexane solvent using PCM Model.

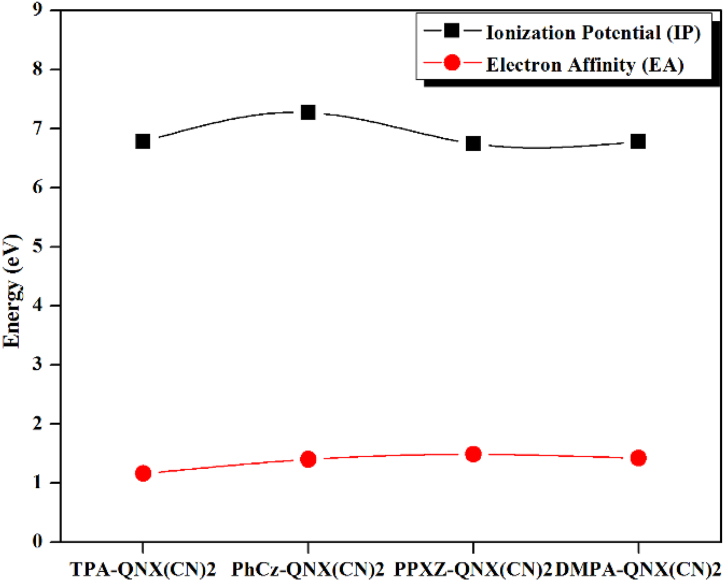

3.5. Charge injection and transport analysis

To explore the charge injection and transport capacities of the investigated molecules, which influence the device performance of OLEDs significantly, we estimated the vertical ionisation potentials (IPv), adiabatic ionisation potentials (IPa), vertical electron affinities (EAv), adiabatic electron affinities (EAa), electron extraction potential (EEP), and hole extraction potential (HEP) as recorded in Table 5. In general, smaller IP and greater EA encourage the infusion of holes and electrons into emitters. The EAv and EAa values of PhCz-QNX(CN)2, PPXZ-QNX(CN)2 and DMPA-QNX(CN)2 are higher than TPA-QNX(CN)2, suggesting better electron injection abilities. Besides, PPXZ-QNX(CN)2 also exhibits better hole injection ability for its lower IPa value than that of TPA-QNX(CN)2 as shown in Fig. 7. Despite this, the low reorganization energy (λ) is the main parameter for the charge transfer rate according to the semi-classical Marcus theory. The λ is associated with geometric relaxation escorting charge transfer. The λ is a significant element that governs the efficiency of OLED materials and links the electronic structures and the charge transport properties. The internal hole/electron reorganization energies (λh/λe) can be expressed by the following equations [[58], [59], [60]]:

| (5) |

| (6) |

where E(M‾) and E(M+) are the energies of neutral species at the optimized charged state, and E‾(M‾) and E+(M+) are the energies of charged molecules at the optimized charged state.

Table 5.

DFT estimates of IPv, IPa, EAv, EAa, HEP, EEP, λh and λe (energies in eV).

| Molecules | IPv | IPa | EAv | EAa | HEP | EEP | λh | λe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPA-QNX(CN)2 | 6.779 | 6.730 | 1.162 | 1.436 | 6.667 | 1.692 | 0.112 | 0.530 |

| PhCz-QNX(CN)2 | 7.277 | 7.245 | 1.402 | 1.626 | 7.204 | 1.844 | 0.073 | 0.442 |

| PPXZ-QNX(CN)2 | 6.750 | 6.562 | 1.485 | 1.702 | 6.688 | 1.909 | 0.062 | 0.424 |

| DMPA-QNX(CN)2 | 6.782 | 6.742 | 1.423 | 1.639 | 6.710 | 1.844 | 0.072 | 0.421 |

Fig. 7.

Ionisation potentials (IPv) and electron affinities (EAv) values for all the investigated molecules.

As we can see from Fig. 8, the calculated hole reorganization energies (λh) of the designed molecules are in the range of 0.062–0.073 eV, which are lower than the parent molecule (0.112 eV) as well as lower from the typical hole transport material TPD (0.29 eV). Especially, the designed molecule PPXZ-QNX(CN)2 exhibits extremely small λh values (0.062 eV), indicating good hole transport abilities. On the other hand, although, the calculated λe values (0.421–0.442 eV) for all the derivatives are larger than the classical electron transport material tri(8-hydroxyquinolinato) aluminum (III) (0.28 eV) but still smaller than the parent compound (0.530 eV). Moreover, the λh is found to be lower compared with λe, demonstrating that the hole transport capacity of these designed materials is superior to electron transporting ability.

Fig. 8.

Reorganization energies for holes and electrons (λh and λe) for all the investigated molecules.

4. Conclusions

In summary, three novel D-A triptycenes adopting dicyanoquinoxaline QNX(CN)2 as the acceptor fragment and N-phenylcarbazole, N-phenylphenoxazine, and 9,9-dimethyl-10-phenylacridine as the D-fragments, respectively, have been designed for highly effective TADF materials based on TPA-QNX(CN)2. The optimal HF% (OHF) method was adopted in our study which has been confirmed to be reliable to calculate the ΔEST and λem values. It is found that for the molecules with the same acceptor fragment, the ΔES1-T1 values reduce with increasing electron-donating strength of the D-fragments, following a tendency: PhCz-QNX(CN)2 (0.33 eV) > TPA-QNX(CN)2 (0.12 eV) > PPXZ-QNX(CN)2 (0.01 eV) = DMPA-QNX(CN)2 (0.01 eV). Besides, the investigated molecules possess higher 3LE states than 3CT states except for PhCz-QNX(CN)2, whose 3LE state is lower than 3CT. However, the ΔEST (CT) values seem to be sensitive to the β values. Thus, PhCz-QNX(CN)2 (0.05 eV) shows a smaller value of ΔEST (CT) than that of TPA-QNX-(CN)2 (0.12 eV). Moreover, the λem values of these molecules changes following the same order of the electron-donating strength. PhCz-QNX(CN)2 exhibits a hypsochromic-shifted λem value (434 nm) compared with that of TPA-QNX(CN)2, promising to be efficient blue TADF materials. While PPXZ-QNX-(CN)2 and DMPA-QNX(CN)2 displaying green and yellow-red emissions centered at 518 and 610 nm, respectively, are also excellent TADF candidates. The EAv and EAa values of all the designed molecules are higher than TPA-QNX(CN)2, suggesting better electron injection abilities. Besides, PPXZ-QNX(CN)2 also exhibits better hole injection ability for its lower IPa value than that of TPA-QNX(CN)2. The calculated λh values of the designed molecules (0.062–0.073 eV) are lower than the parent molecule (0.112 eV) as well as lower than the typical hole transport material TPD (0.29 eV). Moreover, the λh values are found to be lower compared with λe, demonstrating that the hole transport capacity of these designed materials is superior to electron transporting ability. The greater electron-donating strength, the smaller ΔEST, and the smaller λh value for PPXZ-QNX(CN)2 make it the best candidate among all the designed molecules. We believe that our theoretical investigation provides hints for the design of unique and high-performance TADF-based OLEDs.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Aftab Hussain: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Ahmad Irfan: Validation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation. Farah Kanwal: Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Mohamed Hussien: Visualization, Validation, Resources. Mehboob Hassan: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. Saifedin Y. DaifAllah: Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Wang Jing: Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Muhammad Abdul Qayyum: Software, Resources, Project administration. Shamsa Bibi: Software, Resources, Formal analysis. Aijaz Rasool Chaudhry: Software, Resources, Project administration, Investigation, Funding acquisition. Jingping Zhang: Supervision, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments and funding statement

A. Irfan extends his appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University for funding through large research groups program under grant number R.G.P.2/267/44. The authors from University of Bisha extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at University of Bisha for funding through the general research project under grant number (UB-GRP-70 -1444). We are also thankful to the School of Chemistry, University of the Punjab for providing research facilities.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e21571.

Contributor Information

Aftab Hussain, Email: aftab.chem@pu.edu.pk.

Ahmad Irfan, Email: irfaahmad@gmail.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Endo A., Ogasawara M., Takahashi A., Yokoyama D., Kato Y., Adachi C. Thermally activated delayed fluorescence from Sn4+–porphyrin complexes and their application to organic light emitting diodes — a novel mechanism for electroluminescence. Adv. Mater. 2009;21:4802–4806. doi: 10.1002/adma.200900983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balijapalli U., Nagata R., Yamada N., Nakanotani H., Tanaka M., D'Aléo A., Placide V., Mamada M., Tsuchiya Y., Adachi C.J.A.C.I.E. Highly efficient near‐infrared electrofluorescence from a thermally activated delayed fluorescence molecule. 2021;60:8477–8482. doi: 10.1002/anie.202016089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee S.Y., Yasuda T., Komiyama H., Lee J., Adachi C. Thermally activated delayed fluorescence polymers for efficient solution-processed organic light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 2016;28:4019–4024. doi: 10.1002/adma.201505026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cui L.-S., Nomura H., Geng Y., Kim J.U., Nakanotani H., Adachi C. Controlling singlet–triplet energy splitting for deep-blue thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;56:1571–1575. doi: 10.1002/anie.201609459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tao Y., Yuan K., Chen T., Xu P., Li H., Chen R., Zheng C., Zhang L., Huang W. Thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials towards the breakthrough of organoelectronics. Adv. Mater. 2014;26:7931–7958. doi: 10.1002/adma.201402532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang M., Jiang B., Xie G., Yang C. Highly efficient solution-processed deep-red organic light-emitting diodes based on an exciplex host composed of a hole transporter and a bipolar host. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2017;8:4967–4973. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.7b02326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Z., Ni F., Wu Z., Hou Y., Zhong C., Huang M., Xie G., Ma D., Yang C. Enhancing spin-orbit coupling by introducing a lone pair electron with p orbital character in a thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitter: photophysics and devices. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2019;10:2669–2675. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.9b00937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeon Y.P., Kong B.K., Lee E.J., Yoo K.-H., Kim T.W. Ultrahighly-efficient and pure deep-blue thermally activated delayed fluorescence organic light-emitting devices based on dimethylacridine/thioxanthene-S,S-dioxide. Nano Energy. 2019;59:560–568. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu T., Deng C., Duan K., Tsuboi T., Niu S., Wang D., Q.J.A.A.M. Zhang . 2022. Interfaces, Zero–Zero Energy-Dominated Degradation in Blue Organic Light-Emitting Diodes Employing Thermally Activated Delayed Fluorescence. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu L., Wu Z., Xie G., Zhong C., Zhu Z., Cong H., Ma D., Yang C. Achieving a balance between small singlet-triplet energy splitting and high fluorescence radiative rate in a quinoxaline-based orange-red thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitter. Chem. Commun. 2016;52:11012–11015. doi: 10.1039/c6cc05203g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaji H., Suzuki H., Fukushima T., Shizu K., Suzuki K., Kubo S., Komino T., Oiwa H., Suzuki F., Wakamiya A., Murata Y., Adachi C. Purely organic electroluminescent material realizing 100% conversion from electricity to light. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8476. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tu Z., Han G., Hu T., Duan R., Yi Y. Nature of the lowest singlet and triplet excited states of organic thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitters: a self-consistent quantum mechanics/embedded charge study. Chem. Mater. 2019;31:6665–6671. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhan L., Chen Z., Gong S., Xiang Y., Ni F., Zeng X., Xie G., Yang C. A simple organic molecule realizing simultaneous TADF, RTP, AIE, and mechanoluminescence: understanding the mechanism behind the multifunctional emitter. Angew. Chem. 2019;58:17651–17655. doi: 10.1002/anie.201910719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wada Y., Nakagawa H., Matsumoto S., Wakisaka Y., Kaji H.J.N.P. Organic light emitters exhibiting very fast reverse intersystem crossing. 2020;14:643–649. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shiu Y.-J., Cheng Y.-C., Tsai W.-L., Wu C.-C., Chao C.-T., Lu C.-W., Chi Y., Chen Y.-T., Liu S.-H., Chou P.-T. Pyridyl pyrrolide boron complexes: the facile generation of thermally activated delayed fluorescence and preparation of organic light-emitting diodes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:3017–3021. doi: 10.1002/anie.201509231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santos P.L., Ward J.S., Data P., Batsanov A.S., Bryce M.R., Dias F.B., Monkman A.P. Engineering the singlet–triplet energy splitting in a TADF molecule. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2016;4:3815–3824. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Obolda A., Peng Q., He C., Zhang T., Ren J., Ma H., Shuai Z., Li F. Triplet–polaron-interaction-induced upconversion from triplet to singlet: a possible way to obtain highly efficient OLEDs. Adv. Mater. 2016;28:4740–4746. doi: 10.1002/adma.201504601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freeman D.M.E., Musser A.J., Frost J.M., Stern H.L., Forster A.K., Fallon K.J., Rapidis A.G., Cacialli F., McCulloch I., Clarke T.M., Friend R.H., Bronstein H. Synthesis and exciton dynamics of donor-orthogonal acceptor conjugated polymers: reducing the singlet-triplet energy gap. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:11073–11080. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b03327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiao Y., Đorđević L., Mao H., Young R.M., Jaynes T., Chen H., Qiu Y., Cai K., Zhang L., Chen X.-Y.J.J.o.t.A.C.S. A donor–acceptor [2] catenane for visible light. Photocatalysis. 2021;143:8000–8010. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c01493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rajamalli P., Senthilkumar N., Gandeepan P., Huang P.-Y., Huang M.-J., Ren-Wu C.-Z., Yang C.-Y., Chiu M.-J., Chu L.-K., Lin H.-W., Cheng C.-H. A new molecular design based on thermally activated delayed fluorescence for highly efficient organic light emitting diodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:628–634. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b10950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan K.-C., Li S.-W., Ho Y.-Y., Shiu Y.-J., Tsai W.-L., Jiao M., Lee W.-K., Wu C.-C., Chung C.-L., Chatterjee T., Li Y.-S., Wong K.-T., Hu H.-C., Chen C.-C., Lee M.-T. Efficient and tunable thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitters having orientation-adjustable CN-substituted pyridine and pyrimidine acceptor units. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016;26:7560–7571. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matulaitis T., Imbrasas P., Kukhta N.A., Baronas P., Bučiunas T., Banevičius D., Kazlauskas K., Gražulevičius J.V., Juršėnas S. Impact of donor substitution pattern on the TADF properties in the carbazolyl-substituted triazine derivatives. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2017;121:23618–23625. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oh C.S., Pereira D.S., Han S.H., Park H.J., Higginbotham H.F., Monkman A.P., Lee J.Y. Dihedral angle control of blue thermally activated delayed fluorescent emitters through donor substitution position for efficient reverse intersystem crossing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2018;10:35420–35429. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b10595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olivier Y., Sancho-Garcia J.C., Muccioli L., D'Avino G., Beljonne D. Computational design of thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials: the challenges ahead. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2018;9:6149–6163. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.8b02327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li W., Li B., Cai X., Gan L., Xu Z., Li W., Liu K., Chen D., Su S.J. Tri-spiral donor for high efficiency and versatile blue thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials. Angew. Chem. 2019;58:11301–11305. doi: 10.1002/anie.201904272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang S.-Y., Wang Y.-K., Peng C.-C., Wu Z.-G., Yuan S., Yu Y.-J., Li H., Wang T.-T., Li H.-C., Zheng Y.-X.J.J.o.t.A.C.S. Circularly polarized thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitters in through-space charge transfer. on asymmetric spiro skeletons. 2020;142:17756–17765. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c08980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawasumi K., Wu T., Zhu T., Chae H.S., Van Voorhis T., Baldo M.A., Swager T.M. Thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials based on homoconjugation effect of donor-acceptor triptycenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:11908–11911. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b07932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qian R., Tong H., Huang C., Li J., Tang Y., Wang R., Lou K., Wang W. A donor-acceptor triptycene-coumarin hybrid dye featuring a charge separated excited state and AIE properties. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016;14:5007–5011. doi: 10.1039/c6ob00822d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Becke A.D. Density‐functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:5648–5652. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Irfan A., Aftab H., Al-Sehemi A.G. Push–pull effect on the geometries, electronic and optical properties of thiophene based dye-sensitized solar cell materials. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2014;18:914–919. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hussain A., Yuan H., Li W., Zhang J. Theoretical investigations of the realization of sky-blue to blue TADF materials via CH/N and H/CN substitution at the diphenylsulphone acceptor. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2019;7:6685–6691. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu R., Song Y., Zhang K., Pang X., Tian M., He L.J.A.F.M. Intrinsically ionic, thermally activated delayed fluorescent materials for efficient, bright, and stable. Light‐Emitting Electrochemical Cells. 2022;32 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hariharan P.C., Pople J.A. Accuracy of AH n equilibrium geometries by single determinant molecular orbital theory. Mol. Phys. 1974;27:209–214. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frisch M.J., Pople J.A., Binkley J.S. Self‐consistent molecular orbital methods 25. Supplementary functions for Gaussian basis sets. J. Chem. Phys. 1984;80:3265–3269. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Staroverov V.N., Scuseria G.E., Tao J., Perdew J.P. Comparative assessment of a new nonempirical density functional: molecules and hydrogen-bonded complexes. J. Chem. Phys. 2003;119:12129–12137. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adamo C., Barone V. Toward reliable density functional methods without adjustable parameters: the PBE0 model. J. Chem. Phys. 1999;110:6158–6170. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao Y., Truhlar D.G. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2008;120:215–241. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chai J.-D., Head-Gordon M. Long-range corrected hybrid density functionals with damped atom-atom dispersion corrections. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008;10:6615–6620. doi: 10.1039/b810189b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yanai T., Tew D.P., Handy N.C. A new hybrid exchange–correlation functional using the Coulomb-attenuating method (CAM-B3LYP) Chem. Phys. Lett. 2004;393:51–57. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiang Y., Hu Z., Zhou B., Zhong C., Sun Z., Sun H. Accurate prediction for dynamic hybrid local and charge transfer excited states from optimally tuned range-separated density functionals. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2019;123:5616–5625. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang C., Zhou K., Huang S., Zhang Q. Toward an accurate description of thermally activated delayed fluorescence: equal importance of electronic and geometric factors. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2019;123:13869–13876. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu T., Chen F. Multiwfn: a multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012;33:580–592. doi: 10.1002/jcc.22885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang S., Zhang Q., Shiota Y., Nakagawa T., Kuwabara K., Yoshizawa K., Adachi C. Computational prediction for singlet- and triplet-transition energies of charge-transfer compounds. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 2013;9:3872–3877. doi: 10.1021/ct400415r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang Q., Kuwabara H., Potscavage W.J., Jr., Huang S., Hatae Y., Shibata T., Adachi C. Anthraquinone-based intramolecular charge-transfer compounds: computational molecular design, thermally activated delayed fluorescence, and highly efficient red electroluminescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:18070–18081. doi: 10.1021/ja510144h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cai X., Li X., Xie G., He Z., Gao K., Liu K., Chen D., Cao Y., Su S.-J. Rate-limited effect” of reverse intersystem crossing process: the key for tuning thermally activated delayed fluorescence lifetime and efficiency roll-off of organic light emitting diodes. Chem. Sci. 2016;7:4264–4275. doi: 10.1039/c6sc00542j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao Y., Truhlar D.G. Hybrid meta density functional theory methods for thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, and noncovalent interactions: the MPW1B95 and MPWB1K models and comparative assessments for hydrogen bonding and van der Waals interactions. J. Phys. Chem. 2004;108:6908–6918. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boese A.D., Martin J.M. Development of density functionals for thermochemical kinetics. J. Chem. Phys. 2004;121:3405–3416. doi: 10.1063/1.1774975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhao Y., Truhlar D.G. Density functional for spectroscopy: No long-range self-interaction error, good performance for rydberg and charge-transfer states, and better performance on average than B3LYP for ground states. J. Phys. Chem. 2006;110:13126–13130. doi: 10.1021/jp066479k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang Q., Li B., Huang S., Nomura H., Tanaka H., Adachi C. Efficient blue organic light-emitting diodes employing thermally activated delayed fluorescence. Nat. Photonics. 2014;8:326–332. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fan J.-z., Lin L.-l., Wang C.-k. Decreasing the singlet–triplet gap for thermally activated delayed fluorescence molecules by structural modification on the donor fragment: first-principles study. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2016;652:16–21. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cossi M., Barone V., Cammi R., Tomasi J. Ab initio study of solvated molecules: a new implementation of the polarizable continuum model. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1996;255:327–335. [Google Scholar]

- 52.H.B.S. G. W. T. M. J. Frisch. Scuseria G.E., Robb M.A., Cheeseman J.R., Scalmani G., Barone V., Mennucci B., Petersson G.A., Nakatsuji H., Caricato M., Li X., Hratchian H.P., Izmaylov A.F., Bloino J., Zheng G., Sonnenberg J.L., Hada M., Ehara M., Toyota K., Fukuda R., Hasegawa J., Ishida M., Nakajima T., Honda Y., Kitao O., Nakai H., Vreven T., Montgomery Jr J.A., Peralta J.E., Ogliaro F., Bearpark M., Heyd J.J., Brothers E., Kudin K.N., Staroverov V.N., Kobayashi R., Normand J., Raghavachari K., Rendell A., Burant J.C., Iyengar S.S., Tomasi J., Cossi M., Rega N., Millam J.M., Klene M., Knox J.E., Cross J.B., Bakken V., Adamo C., Jaramillo J., Gomperts R., Stratmann R.E., Yazyev O., Austin A.J., Cammi R., Pomelli C., Ochterski J.W., Martin R.L., Morokuma K., Zakrzewski V.G., Voth G.A., Salvador P., Dannenberg J.J., Dapprich S., Daniels A.D., Farkas O., Foresman J.B., Ortiz J.V., Cioslowski J., Fox D.J. 2009. Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cheng M., Yang X., Zhang F., Zhao J., Sun L. Tuning the HOMO and LUMO energy levels of organic dyes with N-carboxomethylpyridinium as acceptor to optimize the efficiency of dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2013;117:9076–9083. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kumar C.H.P., Ganesh K., Suresh T., Sharma A., Bhanuprakash K., Sharma G.D., Chandrasekharam M. Influence of thermal and solvent annealing on the morphology and photovoltaic performance of solution processed, D-A-D type small molecule-based bulk heterojunction solar cells. RSC Adv. 2015;5:93579–93590. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang D.D., Suzuki K., Song X.Z., Wada Y., Kubo S., Duan L., Kaji H. Thermally activated delayed fluorescent materials combining intra- and intermolecular charge transfers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019;11:7192–7198. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b19428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang Q., Li J., Shizu K., Huang S., Hirata S., Miyazaki H., Adachi C. Design of efficient thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials for pure blue organic light emitting diodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:14706–14709. doi: 10.1021/ja306538w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lu J., Zheng Y., Zhang J. Computational design of benzo [1,2-b:4,5-b′] dithiophene based thermally activated delayed fluorescent materials. Dyes Pigments. 2016;127:189–196. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hussain A., Kanwal F., Irfan A., Hassan M., Zhang J. Exploring the influence of engineering the linker between the donor and acceptor fragments on thermally activated delayed fluorescence characteristics. ACS Omega. 2023;8:15638–15649. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.3c01098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hutchison G.R., Ratner M.A., Marks T.J. Hopping transport in conductive heterocyclic oligomers: reorganization energies and substituent effects. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:2339–2350. doi: 10.1021/ja0461421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li Y., Zou L.-Y., Ren A.-M., Feng J.-K. Theoretical study on the electronic structures and photophysical properties of a series of dithienylbenzothiazole derivatives. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2012;981:14–24. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.