Abstract

Cadmium (Cd) is one of the most toxic heavy metals for human health. It can be present in multiple food products, including cocoa cultivated in regions with high soil Cd concentrations. A strategy to minimize Cd uptake by cacao trees is using cadmium-tolerant bacteria (CdtB) and filamentous fungi (CdtF) to reduce Cd availability in soils. We isolated culturable CdtB and CdtF from different locations in a cocoa-producing region in central Colombia. A total of 42 CdtB and 30 CdtF morphotypes were isolated from locations with varying natural Cd concentrations. In vitro characterizations showed that in addition to their resistance to Cd, bacteria and fungi are involved in the nutrient cycling of N, P, and C in the soil. Bacterial morphotypes from genera Pseudomonas and Burkholderia grew in concentrations up to 140 mg kg−1 Cd. Among the isolated fungi, P. igniaria, Metarhizium sp., and Annulohypoxylon sp. were the most resistant, with the highest average Cd bioaccumulation, Cd remotion, and tolerance. We present new information about the native culturable bacterial morphotypes associated with cacao plants and, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of Cd-TF associated with cacao crops. Our results expand the knowledge about culturable CdtB and CdtF in cacao-cultivated soils and their interaction with key soil elements, with the potential to develop integrated soil management strategies.

Keywords: Heavy metal, Cellulose, Phosphorous, Nitrogen, Soil remediation, Bioaccumulation

1. Introduction

Cadmium (Cd) is a prevalent agent in soils with toxic effects on microorganisms, plants, and humans. Cd occurs naturally in soils as a product of volcanic eruptions, burning of vegetation, soil evolution [1,2], and solubilization from minerals such as Greenockite (CdS), Otavite (CdCO3), Cadmoselite (CdSe), Monteponite (CdO), and Metacinnabar Cd ([Hg, Cd]S) [2]. The presence of Cd in soils also depends on anthropogenic activities such as mining; manufacturing of plastics, paint pigments, and batteries; agricultural practices such as the application of phosphate-based fertilizers that could contain traces of Cd up to 130 mg kg−1 [3], and irrigation with untreated wastewater [4,5]. The distribution and availability of Cd in the soil vary depending on the physical-chemical properties (e.g. texture, pH, organic matter composition, effective cation exchange capacity, total metal content), microbial community, and climate conditions [6].

The presence of Cd in plant edible organs is related to both the ability of the plant to extract, transport, and accumulate Cd in its tissues; and the availability of Cd in the soil [7]. Cd has been detected in several crops [8], including cocoa beans and derived products [1,[9], [10], [11], [12]]. Cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) is considered a traditional exportable commodity with a global production of 5.76 million tons in 2020 [13], of which 68 % comes from developing countries [5,14]. Concentrations of Cd in cacao-based chocolate and raw cacao beans above the maximum limits (0.1–0.8 mg kg−1 Cd in dry matter) established by the European Union (Commission Regulation (EU) No. 488/2014, 2014) [15] have been reported in some South and Central American countries [10,16] representing a major concern because of the potential impacts on human health [17], food safety, and the cocoa industry [5].

Agronomic and postharvest strategies have been explored to reduce Cd contents in cocoa beans and their derivates [18]. Using soil microorganisms with the ability to adsorb, bioaccumulate and biotransform Cd is an attractive approach for carrying out bioremediation processes of contaminated soils [19]. Soil bacteria have several biochemical tolerance mechanisms to overcome toxic levels of Cd, such as biosorption, intracellular sequestration (bioaccumulation), extracellular binding (bioleaching), complexation (biotransformation), biodegradation, chemisorption, and bioweathering [20]. A reduction of Cd uptake by plants using Cd tolerant bacteria (CdtB) and Cd tolerant plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) has been reported in wheat and maize [21], rice [22], mustard [23], tomato [24], pea [25], and soybean [26]. Among CdtB with the potential to reduce the availability of this heavy metal at the interchangeable soil phase, Pseudomonas aeruginosa [27], Pseudomonas putida [28], Serratia spp. [29], Burkholderia spp. [30], Halomonas spp. [31] and Enterobacter spp. [32] have been commonly reported in several environments.

Soil filamentous fungi represent another valuable group for bioremediation because of their role in nutrient cycling and their ability to adapt to extreme pH conditions, nutrients, and other physicochemical parameters, including the presence of heavy metals [33,34]. Fungi have developed tolerance mechanisms to heavy metals by altering multiple cellular processes and regulating gene expression [35,36]. These mechanisms include reduced metal intake or increased extracellular flow, the immobilization of metals by adsorption in the cell wall or by storage in the vacuole, and extracellular metal sequestration by exopolysaccharides and other metabolites [37]. Bioaccumulation occurs in living cells and comprises processes dependent on metabolisms such as the production of enzymes and organic acids, transmembrane transport, and the sequestration of metals inside the cell in the vacuole or the cytoplasm using proteins such as metallothionein proteins [38]. In contrast, through biosorption, metals bind the fungal biomass (living or inactive) without energy [39]. The tolerance level of fungi to heavy metals has been associated with environmental factors, soil physicochemical properties, type of metal and concentration, and the isolated strain [40]. Multiple soil fungi such as Aspergillus spp., Paecilomyces spp., Microsporum sp., Cladosporium sp. [41], Fusarium spp. [42], Lentinula edodes [43], Agaricus blazei [44], Laccaria bicolor [45], and Trichoderma spp. [46] have shown the potential to bioaccumulate Cd. Therefore, using CdtF is a promising tool for reducing the bioavailability of this element in cocoa-cultivated soils [47].

In Colombia, where the spatial distribution and concentration of Cd in cacao-cultivated soils have been mainly associated with a geogenic origin [48,49], CdtB belonging to a few genera have been isolated from cacao-cultivated soils [50]. Recently Cáceres et al. [51] explored the bacterial community associated with cocoa plantations in Colombia, and Sandoval-Pineda et al. [52] studied the presence of mycorrhizal fungi. However, no studies have been conducted on the isolation and characterization of culturable Cd tolerant filamentous fungi (CdtF) and additional characterization of CdtB. In this study, we carry out a morphological and molecular identification of CdtB and CdtF isolated from cacao-cultivated soils. We characterize the in vitro activity of the isolated microorganisms related to carbon, phosphorus, and nitrogen; we evaluate the effect of Cd on the growth of isolated morphotypes and their ability to bioaccumulate and tolerate Cd. Our results are primary inputs for future basic and applied research aimed at studying the mechanisms of Cd tolerance in microorganisms and reducing Cd in crops with applications in cocoa crops.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study area and sampling

Soil samples were obtained from two municipalities of Cundinamarca, Colombia: Nilo (NC) 4°18′25°N - 74°37′12′O, and Yacopí (Y) 5°27′35°N - 74°20′18′O, previously studied in soil Cd concentrations [48]. These regions have average temperatures of 26.5 °C and 21 °C with annual precipitation of 1292 and 1500 mm, respectively. Three cacao-producing farms were sampled in Y and one in NC (Fig. 1). In each sampling site, three producing trees were randomly selected, and four bulk soil sub-samples (0.5 Kg each) were collected 0.5 m from the trunk base and at a depth of 0.3 m. Sub-samples were mixed to get a composite sample per farm. These samples were transported to the laboratory in polystyrene containers at 4 °C. One fraction of the sample was used for the determination of physical and chemical properties, taxonomic classification, and the other for microbiological analysis.

Fig. 1.

Location of sampling sites. Each dot represents a cacao farm where soil cadmium levels were previously documented In Cundinamarca, Colombia.

2.2. Soil cadmium determination

Composite samples were used to quantify the total Cd and potentially available Cd. Total Cd was determined by digestion of 1 g of soil sample with 7 ml of HNO3 65 % (v/v) and 1 ml of HCl 37 % (v/v). Samples and acids were mixed using a single reaction chamber UltraWAVE (ECR; Milestone, Shelton, CT). The temperature rose from 20 °C to 220 °C in 20 min and was maintained for 10 min for a total digestion time of 30 min. After digestion, 10 ml of deionized water was added, and samples were filtered using 0.2 μm × 47 mm sterile Swinnex filters (Merck-Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). Potentially available Cd was quantitatively determined with DTPA extraction solution [0.005 M diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA), 0.01 M calcium chloride dihydrate (CaCl2 2H2O), and 0.1 M triethanolamine (TEA)] in a 1:2 proportion (w/v).

Determinations were performed using an Agilent 700 series Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-OES) spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Inc., CA, USA) with 5 mL of the digested sample and a running time of 90 s per sample. The ICP Expert II software was used to analyze raw ICP data. A standard curve was created using CdCl2 aliquots (Sigma-Aldrich Corp., 99 % purity w/w, CA) in eight concentrations ranging from 0 to 500 mg L−1; Fig. S1). Additionally, aliquots of the reference material WEPAL-ISE-997 (Sandy soil with 0.400 mg kg−1 of Cd2+, obtained from the Wageningen evaluating program for analytical laboratories (Wageningen Agricultural University, the Netherlands) were included [50].

2.3. Isolation and identification of Cd-tolerant bacteria and fungi

Bacteria and fungi were isolated by plating out serial dilutions of soil as previously described [53]. Briefly, 50 g of sifted soil (2 mm) were suspended in 450 ml of 0.85 % NaCl, mixed with vortex for 10 min, and 1 ml of the dilution was transferred to a new assay tube with 9 ml of NaCl and remixed for 1 min. The process was made up to 10−7 dilution and 100 μl of the dilutions 10−3, 10−5, and 10−7 (only for bacteria) were plated out on Mergeay agar [54] pH 7 with 6 mg kg−1 of Cd from CdCl2. Three technical replicates for each dilution were incubated at 37 °C for three days for bacteria, and at 28 °C for ten days for fungi. Following incubation, the colony-forming unit (CFU) was calculated per gram of dry soil as an indirect measure to determine total abundance by location [55]. Morphotypes with differential morphological characteristics were subcultured in Mergeay agar with 6 mg kg−1 of Cd and were preserved in glycerol stocks at - 80 °C. All the strains were deposited and are publicly available at the Colombian Bank of Strains and Genes of the Biotechnology Institute of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia (IBUN, Spanish acronym). The bank is registered in the Unique National Registry of Collections administered by the Humboldt Institute, Colombia.

Micro and macro morphological characterizations were performed on each isolated assessing colony color (Pantone scale), shape, margins, surface appearance, elevation, surface appearance, and consistency. When applicable, Gram-stain and endospore stain with malachite green dye in contrast with safranin were performed.

DNA was extracted according to Chen and Kuo [56] for bacteria and using a CTAB protocol for fungi [53]. Molecular identification was performed by amplification and sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene with the universal primers 27F and 1492R in bacteria, and the ITS1, 5.8S, and ITS2 regions with the universal primers ITS1- 4 for fungi [53]. All sequences were submitted to the GenBank at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI).

The phylogenetic trees were inferred using the Muscle multiple alignment method and Neighbor-joining algorithm [57]. The evolutionary distances were computed using the p-distance method, and nodes are supported in the bootstrap method using 1000 pseudoreplicates [58]. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7 [59].

2.4. Qualitative functional characterization associated with C, P, and N

The cellulolytic potential of isolated morphotypes was assessed in LB agar with carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) as the unique carbon source and staining with Congo red [60]. Phosphate solubilization activity was assessed in SMRS agar [61], and the solubilization factor (SF) was calculated using bromocresol purple. Hydrolysis and solubilization factors establish the ratio of degradation or solubilization diameter and colony growth diameter [62]. For bacteria, atmospheric nitrogen fixation activity was observed on Rennie agar [63] with bromothymol blue as an indicator, through growth and color variation of this medium that lacks N. Three technical replicates per morphotype were used for each functional group (C, P, N).

2.5. Effect of Cd on bacterial and fungal growth

Tolerant morphotypes previously isolated on Mergeay agar with 6 mg kg−1 of Cd were tested at higher Cd concentrations. Bacteria were inoculated in LB agar with 12 and 18 mg kg−1 of Cd, and fungi with 12, 18, and 24 mg kg−1 Cd. For growth and bioaccumulation characterization, bacteria tolerant to 18 mg kg−1 of Cd and five fungal morphotypes growing at 24 mg kg−1 Cd were selected. Pathogenicity and previous reports were considered for the selection of the fungal morphotypes.

Bacterial growth curves were analyzed in LB broth with 18 mg kg−1 of Cd and without Cd in two independent experiments. Media were inoculated with 0.1 % (v/v) of bacterial cultures of 18 h-old, and incubated at 37 °C with constant shaking at 200 rpm [64,65]. With three replicates for each morphotype, optic density at 600 nm (OD600) was determined every 2 h for 36 h using a NanoDropTM ONE spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA).

Fungal morphotypes were grown in potato dextrose agar (PDA) plates with (50 mg kg−1) and without Cd using a 5 mm diameter disk from a 10-day old pure culture in PDA with no Cd [41] and incubated at 28 °C. After 10 days post-inoculation (dpi) radial growth was measured. Each morphotype had three replicates, and four diameter measurements per replicate were recorded subtracting the diameter of the initial disk (5 mm). The tolerance index (TI) was calculated based on radial growth by dividing the diameter of the colony in media with Cd by the diameter of the colony grown in media without Cd.

To determine the fungal biomass accumulation and phases of growth [41], morphotypes were grown in 50 mL of Sabouraud Dextrose liquid medium (pH 5.5) with 50 mg L−1 of ampicillin and with (50 mg kg−1) or without Cd (control). Cultures were inoculated with a 5 mm diameter disk from a 10-day-old pure culture in PDA (no Cd) and incubated at 28 °C with constant agitation at 150 rpm. Every three days and for 15 days, fungal mycelium was collected using filter paper Whatman ® No. 1 and a vacuum pump coupled to an Erlenmeyer filter flask. The remaining culture medium was removed with two washes with a known volume of sterile distilled-deionized water. The collected fungal biomass was dried at 100 °C until constant weight and dry weight were recorded. For each morphotype, three replicates per sampling point were included.

2.6. Cd bioaccumulation and minimum inhibitory concentration

Cd bioaccumulation was determined in two independent experiments at different times. Bacteria were inoculated into LB broth containing 18 mg kg−1 of Cd and incubated at 37 °C with shaking (200 rpm) with three replicates per bacteria. The bacterial cells were harvested at 18 h after inoculation by centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 15 min, then washed with sterile deionized water to remove free heavy metal ions, and cell pellets were dried at 100 °C until constant weight. In fungi, Cd bioaccumulation was determined from the collected biomass in each growth phase for the five selected morphotypes (described above). In both cases, the supernatants were sterilized by filtration with a 0.22 μm membrane filter (MILLIEX®GP Millipore Express®). Media with no Cd or inoculation were used as standards during Cd determinations.

The concentration of Cd in supernatants was measured by Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometry (AAS; PerkinElmer AAnalyst 300, USA). Cd bioaccumulation (q, mg g−1) in bacterial pellets and fungal biomass was calculated using equation (1) and for fungi, removed Cd (RCd, mg) was determined using equation (2) [41,66], considering the dilution factors.

| (1) |

| (2) |

where q (mg g−1) is the Cd bioaccumulation of bacteria or fungi, Ci and Cf (mg L−1) are the initial and final Cd concentration, respectively, m is the dried weight of cell pellet/fungal biomass (g) and V is the volume of the culture medium (L).

For minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), bacteria were grown in 15 mL conical bottom tubes with 7 mL of LB broth supplemented with 18, 24, and 30 up to 200 mg kg−1 of Cd (intervals of 10 mg kg−1 of Cd) and 20 μl of a bacterial culture of 18 h were inoculated and incubated at 37 °C with constant agitation at 200 rpm for 18 h. Following incubation, turbidity was observed. In fungi, Sabouraud Dextrose liquid media were supplemented with 50, 100, 200, 400, 600, 800, 1000, 1500, 2000, 3000, 4000, 5000, and 6000 mg kg−1 of Cd from CdCl2, and were inoculated with a 5 mm diameter disk from a 10-day old pure culture in PDA without Cd. Cultures were grown at 28 °C and 150 rpm, and the growth was evaluated at 15 dpi. The minimum Cd concentration at which bacterial or fungal morphotypes did not show growth was considered as its MIC.

2.7. Data analysis

Data from hydrolysis and solubilization factors and Cd bioaccumulation were analyzed using a completely randomized design (CRD) with a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) in SAS v9.4 statistical software (SAS Institute Inc., USA). Shapiro-Wilk normality test and Bartlett homogeneity of variance tests were made, and media were compared using Tukey's test (p<0.05).

3. Results

3.1. Soil properties

Soils from the four locations showed mainly clay textures with pH values between 4.2 and 6.25. In mineral contents, the highest variation was found for Ca (1.96–28.20 meq/100g), P (4.14 – >116 mg kg−1), Fe (133.21–580.60 mg kg−1), Mn (0.7–31.7 mg kg−1), and Zn (1.78–78.90 mg kg−1) (Table S1). In Colombia, no reference values for soil Cd are available for agricultural production. In non-polluted soils, Cd concentrations range from 0.01 to 1.1 mg kg−1 with an average of 0.41 mg kg−1 [67]. According to this, in this study total Cd levels in the four locations were categorized as medium (>1.1–5.0 mg kg−1) and high (>5.0 mg kg−1; Table 1). Despite no correlation being performed due to the small sample size, the effective cation exchange capacity (CEC), and Ca and Zn content showed an apparent positive relation with both total and available Cd.

Table 1.

Location, soil taxonomy, and total and potentially available Cd concentrations in sampling sites in Nilo (NC) and Yacopí (Y). Medium (>1.0–5.0 mg kg−1) and high (>5.0 mg kg−1) total Cd level. E.C.E.C: Effective cation exchange capacity.

| Location | Natural region | Soil Taxonomy | pH | E.C.E.C | Cd level | Total Cd (mg Kg−1) | Available Cd (mg Kg−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC | Dry Tropical Forest | Dystric Eutrudepts | 5.87 | 11.94 | Medium | 1.68 | 1.28 |

| Y1 | Tropical Premontane Moist Forest | Typic Udorthents | 4.18 | 12.13 | Medium | 1.74 | 0.20 |

| Y2 | Typic Udorthents | 6.25 | 14.39 | Medium | 4.24 | 2.12 | |

| Y3 | Typic Hapludands | 6.11 | 30.7 | High | 27.21 | 21.18 |

3.2. Isolation, morphological characterization, and identification of Cdt morphotypes

A total of 30 CdtB and 42 CdtF morphotypes were isolated from the different locations in culture media with 6 mg kg−1 Cd (Fig. S2). In general, location Y3 had the highest number of CdtB and CdtF (15 and 21, respectively) and had unique morphotypes that were not present in other locations, particularly in bacteria.

Wide variation in color, shape, margin, consistency, and appearance of the colonies were observed for bacteria and fungi (Tables S2 and S3). 90 % of the isolate bacteria samples (n = 27) were Gram-negative and the remaining 10 % (n = 3) were Gram-positive (Table S2). Based on the BLAST search results of the 16S rRNA gene, we identified eight bacteria genera: Burkholderia, Pseudomonas, Enterobacter, Serratia, Bacillus, Halomonas, Herbaspirillum, and Rhodococcus (Table S4).

The phylogenetic analysis showed that 90 % (n = 27) of the isolated bacteria belong to the phylum Proteobacteria, 6.7 % to Firmicutes (n = 2), and 3.3 % to Actinobacteria (n = 1) (Fig. S3; Table S2). In the phylogenetic tree, Rhodococcus sp. GB17, Bacillus flexus YB22, and Bacillus sp. GB18 were used as an outgroup due to its relationship with the other isolated morphotypes.

In fungi, 95.2 % (n = 40) of the morphotypes belonged to the division Ascomycota and the remaining (4.8 %) to the division Basidiomycota and Zygomycota. The two latter were represented by the genera Rhodotorula and Absidia, respectively (Fig. S4; Table S5). The 42 isolated morphotypes were represented by 12 orders, 21 families, and 27 genera, where the orders Hypocreales and Pleosporales presented the highest relative frequencies with 57 and 11.9 %, respectively (Fig. S3).

3.3. Qualitative functional characterization associated with C, P, and N

Some isolated bacteria and fungi presented functional activities related to C, P, and/or N, in addition to their Cd tolerance. In bacteria, 46.7 % (n = 14) of the isolated morphotypes were able to degrade cellulose, including strains such as Enterobacter sp. YB11, Pseudomonas sp. GB86, Herbaspirillun sp. GB90 and Burkholderia sp. GB68 with hydrolysis factors above 2.5 (Table 2). 53 % of morphotypes were able to solubilize phosphates (n = 16) compared with other functional groups analyzed. Bacteria from the genera Enterobacter, Burkholderia, and Serratia showed high solubilization factors ranging from 1.56 to 4.39 (Table 2). Finally, atmospheric nitrogen fixation ability was observed in half of the isolated morphotypes.

Table 2.

Cellulose hydrolysis and phosphate solubilization factors, and free nitrogen-fixing activity of CdtB. Letters in the same columns represent significant differences (p < 0.05) between strains according to Tukey's multiple comparison test. + and – indicate the presence or absence of growth/fixation on Rennie agar at 3 days post-inoculation (dpi).

| No. | ID | NCBI ID | Loc. | Morphotype | Growth at |

Cellulose hydrolysis factor | P solubilization factor | N fixation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 mg kg−1 | 18 mg kg−1 | ||||||||

| 1 | NB2 | MN719036.1 | NC | P. aeruginosa | + | + | – | – | – |

| 2 | NB10 | MN719037.1 | NC | Burkholderia sp. | + | + | 2.04 ± 0.28 abcd | 3.31 ± 0.55 abc | + |

| 3 | NB40 | MN719038.1 | NC | Halomonas sp. | + | – | – | – | – |

| 4 | NB58 | MN719039.1 | NC | Enterobacter sp. | + | – | – | – | – |

| 5 | NB59 | MN719040.1 | NC | Serratia sp. | + | – | – | – | – |

| 6 | NB61 | MN719041.1 | NC | Serratia sp. | + | – | – | <1.00 | – |

| 7 | NB80 | MN719042.1 | NC | Serratia sp. | + | – | 1.92 ± 0.23 bcd | <1.00 | – |

| 8 | YB11 | MN719043.1 | Y1 | Enterobacter sp. | + | – | 3.25 ± 0.28 a | 3.83 ± 0.48 ab | + |

| 9 | YB30 | MN719044.1 | Y1 | S. marcescens | + | – | – | 4.39 ± 0.49 a | + |

| 10 | YB42 | MN719045.1 | Y1 | S. marcescens | + | – | – | – | – |

| 11 | YB43 | MN719046.1 | Y1 | Serratia sp. | + | – | 0.99 ± 0.01 d | <1.00 | + |

| 12 | YB5 | MN719047.1 | Y2 | Enterobacter sp. | + | – | 1.53 ± 0.30 cd | 1.56 ± 0.21 c | + |

| 13 | YB13 | MN719048.1 | Y2 | Pseudomonas sp. | + | – | – | – | – |

| 14 | YB22 | MN719049.1 | Y2 | Bacillus flexus | – | – | – | – | – |

| 15 | YB48 | MN719050.1 | Y2 | Enterobacter sp. | + | – | 2.00 ± 0.08 bcd | 2.02 ± 0.18 bc | + |

| 16 | GB13 | MN719051.1 | Y3 | Burkholderia sp. | + | – | – | <1.00 | + |

| 17 | GB16 | MN719051.1 | Y3 | Burkholderia sp. | + | – | 1.04 ± 0.13 d | <1.00 | + |

| 18 | GB17 | MN719053.1 | Y3 | Rhodococcus sp. | + | – | 1.01 ± 0.04 d | <1.00 | + |

| 19 | GB18 | MN719054.1 | Y3 | Bacillus sp. | + | – | – | – | – |

| 20 | GB58 | MN719055.1 | Y3 | Burkholderia sp. | + | – | 1.07 ± 0.11 d | – | – |

| 21 | GB66 | MN719056.1 | Y3 | Burkholderia sp. | + | – | 1.20 ± 0.02 d | <1.00 | + |

| 22 | GB67 | MN719057.1 | Y3 | Burkholderia sp. | + | – | – | – | – |

| 23 | GB68 | MN719058.1 | Y3 | Burkholderia sp. | + | – | 2.73 ± 0.58 abc | 3.46 ± 0.46 abc | + |

| 24 | GB71 | MN719059.1 | Y3 | Pseudomonas sp. | + | – | – | <1.00 | + |

| 25 | GB73 | MN719060.1 | Y3 | Pseudomonas sp. | + | + | – | – | – |

| 26 | GB78 | MN719061.1 | Y3 | P. putida | + | + | 1.18 ± 0.01 d | <1.00 | + |

| 27 | GB82 | MN719062.1 | Y3 | Burkholderia sp. | + | – | – | – | – |

| 28 | GB86 | MN719063.1 | Y3 | Pseudomonas sp. | + | – | 3.12 ± 0.43 ab | <1.00 | + |

| 29 | GB88 | MN719064.1 | Y3 | Pseudomonas sp. | + | – | – | – | – |

| 30 | GB90 | MN719065.1 | Y3 | Herbaspirillum sp. | + | – | 2.77 ± 0.21 abc | – | + |

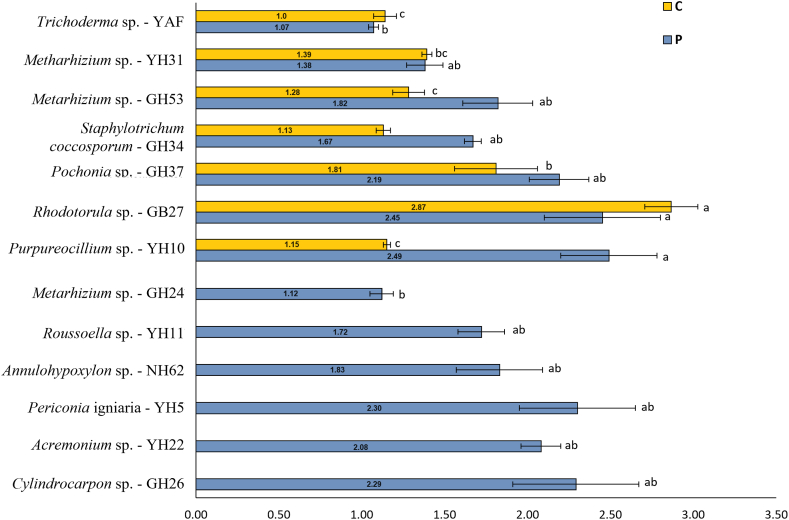

In fungi, the qualitative evaluation of enzymatic activities showed that 14 (33.3 %) out of the 42 isolated morphotypes can degrade cellulose, 34 (80.9 %) solubilize phosphates, and 13 (30.9 %) can carry out both functions (Table S5). The most relevant morphotypes were Rhodotorula sp. GB27 which had significantly higher cellulose hydrolysis (2.87 ± 0.16), and Purpureocillium sp. YH10 with the highest phosphate solubilization factor (2.49 ± 0.29) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Cellulose hydrolysis and phosphate solubilization factors of the top CdtF. Bars represent the typical error (n = 3). Bars with different letter are significantly different (p < 0.05) according to Tukey's multiple comparison test.

3.4. Effect of Cd on bacterial and fungal growth

Among the 30 isolated CdtB morphotypes, only Pseudomonas sp. GB73, Burkholderia sp. NB10, P. aeruginosa NB2, and P. putida GB78 grew on media with 18 mg kg−1 Cd, and the last three were considered for further analysis. The effect of Cd on the growth curve varied among the assessed strains. In the presence of 18 mg kg−1, P. aeruginosa NB2 showed an average reduction of more than one unit of OD600 during the log phase from 14 h after inoculation compared to control without Cd (Fig. 3A). In contrast, P. putida GB78 did not show any difference in OD600 with and without Cd during all growth phases (Fig. 3B). Burkholderia sp. NB10 had a slight reduction of OD600 with Cd from 2 to 20 h post-inoculation, however, from 20 h the OD600 of bacteria grown with Cd reached similar magnitudes to culture without Cd (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Growth of A) P. aeruginosa NB2, B) P. putida GB78 and C) Burkholderia sp. NB10 in the presence and absence of 18 mg Kg−18 of Cd. The bars represent the standard error (n = 6 from two independent experiments). Means with different letters indicate significant differences by Tukey's test (p < 0.05).

In fungi, macroscopic changes in the morphology and radial growth were observed in the five selected morphotypes Trichoderma sp. YAF, Periconia igniaria YH5, Annulohypoxylon sp. NH62, Rousoella sp. YH11, and Metarhizium sp GH24 (Fig. 4A–E). The main changes associated with Cd included a reduction of the radial growth, changes in colony morphology and appearance, and changes in colony pigmentation. Regarding the TI, Metarhizium sp. GH24 and Annulohypoxylon sp. NH52 had TI significantly higher (p < 0.05) (0.99 and 0.97, respectively) than the other morphotypes. Rousoella sp. YH11, P. igniaria YH5, and Trichoderma sp. YAF had TI between 0.71 and 0.82 without significant differences between them (Fig. 4F).

Fig. 4.

Effect of Cd on growth of (A) Trichoderma sp. YAF, (B) P. igniaria YH5, (C) Annulohypoxylon sp NH62, (D) Rousoella sp. YH11, (E) Metarhizium sp GH24 at 10 dpi, and (F) tolerance index of the selected morphotypes. Bars represent typical error (n = 3). Bars with a different letter are significantly different (p < 0.05) according to Tukey's multiple comparison test.

Fig. 5 shows the biomass accumulation curve of the selected fungi in the presence and absence of Cd. Overall, P. igniaria YH5, Rousoella sp. YH11, and Metarhizium sp. GH24 showed a Lag phase (0–2 dpi) and a short acceleration phase (2–4 dpi). In contrast, Trichoderma sp. YAF, and Annulohypoxylon sp. NH62 did not have a Lag phase and accelerated growth was observed from 0 to 4 dpi. Most of the morphotypes reached the exponential phase between four and nine dpi and a deceleration phase from nine dpi. In Trichoderma sp. YAF, P. igniaria YH5 (medium without Cd), and Annulohypoxylon sp. NH62 the stationary phase was observed from 12 dpi.

Fig. 5.

Biomass accumulation of (A) Trichoderma sp. YAF, (B) P. igniaria YH5, (C) Annulohypoxylon sp NH62, (D) Rousoella sp. YH11. and (E) Metarhizium sp GH24 with and without Cd. The values in mg under the curves are the average dry weight of each fungus during the 15 days of evaluation in the presence of 50 mg kg−1 of Cd, on the weight in the absence of Cd. Bars represent typical error (n = 6 from two independent experiments). Bars with a different letter are significantly different (p < 0.05) according to Tukey's multiple comparison test.

Cd affected biomass production in most of the fungal morphotypes. Biomass accumulation decreased significantly (p < 0.05) in Trichoderma sp. YAF (Fig. 5A), Rousoella sp. YH11 (Fig. 5D), and Metarhizium sp. GH24 (Fig. 5E) with average dry weight reductions of 40.8 %, 42.9 %, and 31.0 %, respectively. Nevertheless, Rousoella sp. YH11 did not show significant differences in biomass at 15 dpi compared to the control. Interestingly, in P. igniaria YH5, and Annulohypoxylon sp. NH62, Cd-induced a higher dry weight with increases of 57 % and 12.6 %, respectively, with respect to the control, although no significant differences for most of the sampling moments were observed (Fig. 5B and C). In the presence of Cd, the highest biomass accumulation was evidenced in Annulohypoxylon sp. NH62 (229.8 mg); and Metarhizium sp. GH24 had the highest dry weight in control conditions (281.7 mg). Periconia igniaria YH5 had the lowest biomass accumulation with (112.6 mg) and without (71.7 mg) Cd (Fig. 5B).

3.5. Cd bioaccumulation and minimum inhibitory concentration

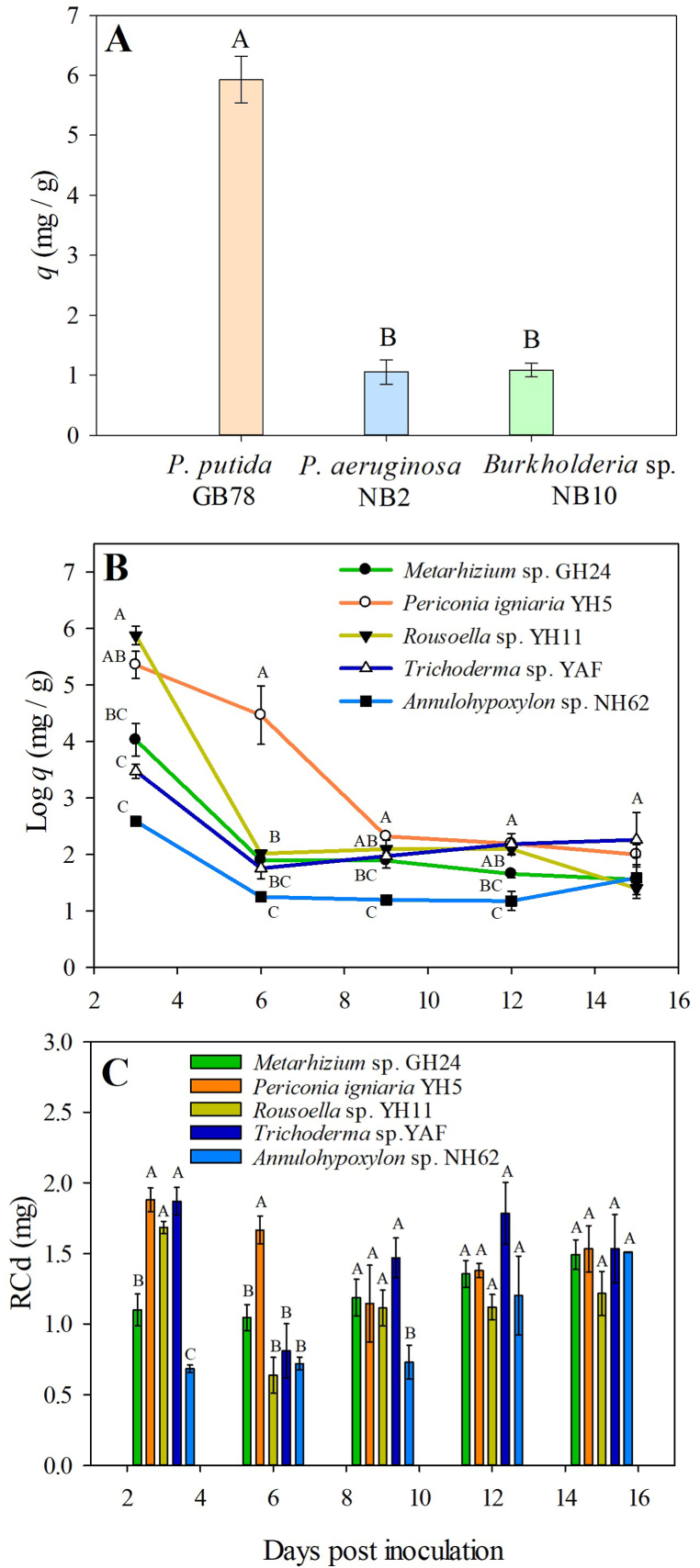

In bacteria, P. putida GB78 accumulated 5.92 mg g−1, which was significantly higher than P. aeruginosa NB2 and Burkholderia sp. NB10 accumulation (around 1 mg g−1; Fig. 6A). For fungi, the evaluation of q, expressed as Log q (mg g−1), over the 15 days of the evaluation showed a tendency to decrease during the three to six dpi for all morphotypes (Fig. 6B). At three dpi, Rousoella sp. YH11 had the highest q (356.6 mg g−1), followed by P. igniaria YH5 (211.4 mg g−1), Metarhizium sp. GH24 (56.2 mg g−1), Trichoderma sp. YAF (32.2 mg g−1), and Annulohypoxylon sp. NH62 (13.3 mg g−1). For all the morphotypes evaluated, q showed values between 3.2 and 10.2 mg g−1 from 6 to 15 dpi, without significant differences. Compared to the other morphotypes, P. igniaria YH5 showed a slower decrease in q, and at six dpi had a significantly higher q (Fig. 6B). In general, P. igniaria YH5 had the highest average bioaccumulation between six to 15 dpi (28.39 mg g−1), followed by Metarhizium sp. GH24, Trichoderma sp. YAF, and Rousoella sp. YH11 (5.82–7.86 mg g−1), and finally Annulohypoxylon sp. NH62 (3.73 mg g−1; Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Bioaccumulation of Cd (q) in (A) Cd-tolerant bacteria at 18 h of growth on media with 18 mg kg−1 of Cd and (B) Cd-tolerant fungi, and (C) removed Cd (RCd) in Cd-tolerant fungi. Bars represent typical error (n = 6). Bars with a different letter are significantly different (p < 0.05) according to Tukey's multiple comparison test.

Given the tendencies observed in q for all morphotypes and considering that q values are a function of biomass development in the fungus, removed Cd (RCd) was calculated from the volume of the growth medium and the initial and final concentration of Cd (Fig. 6C). At three dpi, RCd was significantly higher in P. igniaria YH5, Rousoella sp. YH11 and Trichoderma sp. YAF (1.68–1.88 mg), compared to Annulohypoxylon sp. NH62 and Metarhizium sp. GH24 (0.68 and 1.10 mg, respectively). At six dpi P. igniaria YH5 had a higher Cd removal (1.67 mg) and at nine dpi, Annulohypoxylon sp. NH62 showed the lowest RCd (0.73 mg) compared to the other morphotypes (1.11–1.47 mg). No differences were observed at 12 and 15 dpi. Metarhizium sp. GH24 and Annulohypoxylon sp. NH62 showed gradual increases in RCd throughout the evaluation period and Rousoella sp. YH11 y P. igniaria YH5 showed a decrease at six and nine dpi, respectively, followed by a continuous increase in the amount of removed Cd (Fig. 6C). During the evaluation time, P. igniaria YH5 showed the highest ability to remove Cd from the growing medium with an average of 1.52 mg, followed by Trichoderma sp. YAF with 1.49 mg, Metarhizium sp. GH24 with 1.24 mg, Rousoella sp. YH11 with 1.15 mg, and Annulohypoxylon sp. NH62 con 0.97 mg.

Burkholderia sp. NB10 and P. aeruginosa NB2 showed a MIC of 140 mg kg−1, which is 1.5 times higher than the MIC recorded for P. putida GB78 (90 mg kg−1). In fungi, the MIC varied between 100 and 6000 mg kg−1. Metarhizium sp. GH24 and Annulohypoxylon sp. NH62 were the most tolerant strains with MIC of 6000 and 2000 mg kg−1, respectively, followed by P. igniaria YH5 and Rousoella sp. YH11 with 1000 mg kg−1, and Trichoderma sp. YAF with a MIC of 100 mg kg−1.

4. Discussion

4.1. Soil properties

Soil properties and taxonomy for NC and Y were consistent with the soil survey of the district of Cundinamarca, Colombia, carried out by the Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi [68]. A high ECEC has been associated with higher availability of Cd [69] and high concentrations of Cd are commonly accompanied by high concentrations of Zn [70] which agrees with our results. Linear correlations between Cd and Ca have also been reported in tropical soils in Brazil [71], and Colombia [72]. However, knowledge about the interaction between Cd and Ca is still scarce and further studies with larger sample sizes would be valuable to complement the observed trends.

4.2. Isolation, morphological characterization, and identification of Cdt morphotypes

The soils from Y3 had a higher Cd concentration compared with other samples from Y and NC. The presence of unique and a higher number of morphotypes isolated from soils with higher concentrations of heavy metals have been previously reported [73]. This may be explained because microorganisms that are more sensitive to heavy metals are suppressed by the toxic element and replaced in their ecological niche by more tolerant ones [74].

The morphological characterization showed that 90 % of the bacterial morphotypes corresponded to Gram-negative bacteria. Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria respond differently to the presence of heavy metals [75,76]. Bruins et al. [76] assert that some Gram-negative bacteria (genus Pseudomonas) can tolerate 5 to 30 times more Cd than Gram-positive bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus, S. faecium, Bacillus subtilis). This differential response can be explained due to the composition of the cell wall and the tolerance mechanisms used. Gram-positive bacteria have a thick layer of peptidoglycan (20–80 nm) in which they fix acids, proteins, and polysaccharides. This layer forms a barrier to avoid the entry of heavy metals into the cell, favoring passive tolerance mechanisms such as adsorption [76,77]. In contrast, Gram-negative bacteria have thinner walls (5–10 nm) that allow the influx and efflux of heavy elements and force the bacteria to evolve active mechanisms or flow systems for coping with heavy elements, and to have higher protein synthesis in the presence of Cd [76].

Nevertheless, both types of bacteria can present passive and active tolerance mechanisms to Cd and other heavy metals at the same time [78,79]. This indicates that tolerance depends also on other factors such as type of strain, type, and concentration of the heavy metals, physicochemical properties of soil, and environmental conditions [78]. Most of the isolated morphotypes (90 %) in this study corresponded to the Proteobacteria phylum. This phylum represents the largest and most diverse group of prokaryotes and comprises most Gram-negative bacteria studied to date [80]. It is the phylum most frequently reported in studies related to heavy metals, so strains belonging to several genera have been isolated, characterized, and their metal tolerance characterized [81]. Additionally, Chen et al. [82] highlight that the Proteobacteria phylum together with Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes harbor the most extensive set of heavy metal tolerance genes.

Burkholderia, Pseudomonas, Enterobacter, and Serratia were the most frequently isolated genera. These genera have been reported in the management of cultivated soils. Strains of Burkholderia spp. have the potential to promote plant growth, biocontrol pathogens, and biodegrade toxic molecules [83]. For instance, Enterobacter spp. can improve bioremediation processes of soils contaminated with heavy metals [84,85], and within the genus Pseudomonas, growth-promoting strains have also been reported with the ability to mitigate stress in plants caused by the presence of heavy metals such as Cd and Pb, and metals such as Zn that are toxic at high levels [86,87]. Serratia sp. has been reported as a bacterium that can confer tolerance to heavy metal stress in cereals [21]. Additionally, genera found less often, such as Halomonas and Herbaspirillum, have been involved in the bioremediation processes of Cr and Sr both in symbiosis with algae, and acting alone [[88], [89], [90]], with the potential to fix nitrogen, and chelate heavy metals such As, Pb, and Cu [91,92].

In fungi, Fusarium sp., Trichoderma sp., Clonostachys sp., Metharrizhium sp., Penicillium sp., and Pochonia sp., were the genera with the highest number of isolated morphotypes with the potential to be used in biocontrol, and soil bioremediation or biofertilization. In previous studies, it has been reported that Fusarium spp. can remove heavy metals such as Cr from polluted environments [93]; Trichoderma spp. can remove Cd from regions with low pH [94,95]; and it has been shown that Penicillium sp. has bioremediation activity in soils polluted with hydrocarbons and that strains from this genus have been used for the production of fungal biomass to adsorb heavy metals in soils [96,97]. In Pochonia, genes involved in resistance mechanisms to metals such as Cd and Zn have been reported [98]. Clonostachys sp. has been used as a biocontrol agent for the main cocoa diseases moniliasis, caused by Moniliophthora roreri; witches’ broom, caused by Moniliophthora perniciosa; and black pod, caused by Phytophthora palmivora [99]. Finally, Metarhizhium sp. has shown entomopathogenic activity in several agroecosystems [100].

The soil microorganisms isolated in this study, constitute a potential resource of native microorganisms to manage Cd in cacao-cultivated soils and a resource for future basic and applied research. Further studies are needed to characterize and evaluate the performance of bacteria in the field and their interaction with plants.

4.3. Qualitative functional characterization associated with C, P, and N

Cellulolytic potential, free nitrogen fixation, and phosphate solubilization are desired characteristics in strains that could be potentially used to manage heavy metals in agricultural soils. These properties may enhance nutrient cycling, decrease the use of chemical fertilizers, and increase the environmental sustainability of the crop. In agroforest production systems such as cacao, some interactions, and processes favor nutrient cycling, as a result of the decomposition of organic matter from crop residues and pruning such as litter in the crop, and stems, among others [101]. The decomposition of cellulose increases the levels of organic matter, and carbon can be used as a source of energy for edaphic processes and plant physiology [102]. Organic matter is a fraction to which heavy metals such as Cd can bind and be adsorbed by chelates or other substances. Therefore, when levels of organic matter increase in soil, the bioavailability of Cd for plants can be reduced [103].

The solubilization of phosphates and the promotion of plant growth have been reported for the genus Enterobacter isolated from soil [104]. The primary cellular mechanism through which bacteria solubilize phosphates is the production of organic acids such as gluconic acid, 2-keto gluconic acid, lactic acid, isovaleric acid, isobutyric acid, and acetic acid [104]. These molecules have a negative charge and, therefore can form complexes with metal cations in solution and be involved in the chelation of Cd [105]. The bacteria involved in atmospheric nitrogen fixation (ANF-B) may also play a paramount role in the remediation of Cd-polluted soils [106]. Ivishina et al. [107] showed that ANF-B can secrete extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) and various organic acids and amino acids that may alter the Cd availability in the soil by adsorbing and trapping metals due to the presence of many anionic functional groups.

In fungi, hydrolysis factors around 1.74 have been reported for Fusarium oxysporum and Aspergillus terreus isolated from soybean roots and are considered promising for testing on an industrial scale [108], highlighting the potential of the isolated morphotypes in the present study. Furthermore, Fikrinda et al., (2020) reported rhizospheric fungi with factors up to 2.6. Our results are consistent with these previous results and we isolated strains with even higher hydrolysis factors (up to 2.87). Regarding phosphates solubilization, Purpureocillium sp. YH10 was the morphotype with the highest factor (2.49), and the found factors are also similar to previous reports [109].

The management of Cd-polluted agricultural soils is a complex issue where the Cdt microorganisms could have an important function not only to decrease the Cd availability but also to improve soil fertility. The presence of activity associated with C, P, and N cycling in CdtB is an advantage within holistic crop soil management strategies. Additional analyses that quantify the activity of the enzymes involved and determine the effect of bacteria and fungi on plant growth and physiology would be valuable.

4.4. Effect of Cd on bacterial and fungal growth

Depending on the organism, Cd has multiple effects on growth and development by altering physiology, metabolisms, and molecular processes [110]. Heavy metals affect bacterial growth by causing multiple metabolic alterations such as DNA damage, decreasing protein synthesis, respiration and cell division disruption, and amino acid biosynthesis [32]. These effects explain the growth decrease of P. aeruginosa NB2 at 18 mg kg−1 of Cd during the growth phases (Fig. 4A). In Burkholderia sp. NB10, a reduction of the growth was also detected in the lag and log phases (Fig. 4C); however, the cells were able to adapt and resume growth at the stationary phase. This may be due to the repair of cadmium-mediated cellular damage and adjustment of the cell physiology to limit the distribution of toxic ions in the cell [111].

Bacteria have different Cd tolerance strategies dependent and independent of intracellular accumulation [19,79]. Tolerance mechanisms include metal efflux systems, transportation, precipitation, transformation, and sequestration by metallothionein proteins and thiol compounds such as glutathione [112]. Our results show that the tolerance mechanisms of P. putida GB78 are efficient enough to resist 18 mg kg−1 of Cd without affecting its growth. These results can also be explained based on the difference between the efficiency of tolerance mechanisms of strains. Chen et al. [113] suggest that bacteria can activate tolerance mechanisms such as metal efflux bombs at particular moments which results in a depletion of intracellular Cd content.

The morphological changes in colony shape and pigmentation are some of the common strategies observed in fungi in response to heavy metals [37,114] (Fig. 4A–E). Variations in colony color can be attributed to the induction of melanin synthesis, which is a typical response in some fungi to increase the binding points of Cd to the cell wall, increase the levels of biosorption, and thus prevent the entry of Cd into the cells [37,115,116].

The tolerance index (TI) is a helpful indicator of the response of organisms to adapt and overcome heavy metal stress [41]. According to Oladipo et al. [34], a TI higher than 0.8 denotes strains with a high tolerance level, which was observed for Metarhizium sp. GH24, Annulohypoxylon sp. NH62, and P. ignaria YH5 (0.83–0.99). In this study, Cd had a significant effect on Metarhizium sp. GH24 biomass accumulation (Fig. 5E), but it did not affect its radial growth (high IT). These results suggest that in response to Cd, Metarhizium sp. GH24 reduced its biomass, which may allow it to have available resources for a longer time without affecting the growth rate [114].

In cells, Cd replaces essential minerals such as Zn and induces oxidative stress by increasing reactive oxygen species (ROS) that can cause damage to the DNA and reparation mechanisms, and disequilibrium in cell cycle and metabolism [117]. Together, the different effects caused by Cd reduced growth and biomass accumulation [110]. These effects explain the reduction in biomass accumulation in Trichoderma sp. YAF, Rousoella sp. YH11 and Metarhizium sp. GH24 (Fig. 5). Notably, at 15 dpi, Rousoella sp. YH11 increased in biomass in the presence of 50 mg kg−1 Cd, although no significant differences with the control culture were detected. This suggests a toxic effect of Cd during the first 12 dpi and subsequent acclimatization in Rousoella sp. YH11. However, further evaluations are needed to determine if the increase of biomass is prolonged over time.

The reductions in biomass accumulation in Trichoderma sp. YAF, and Annulohypoxylon sp. from nine and 12 dpi, respectively, are attributed to fungi death because of the presence of Cd, and the declining of resources and space in the medium [118]. These results show that, under in vitro conditions, these fungi had a faster decline in biomass accumulation compared to the other fungi. In the design of management strategies based on fungi, conditions that prevent or delay fungi death must be studied.

The increase of dry weight observed in P. igniaria YH5 and Annulohypoxylon sp. NH62 (Fig. 5) in response to Cd is consistent with previous reports on mycorrhizal and endophytic fungi [[119], [120], [121]]. This phenomenon has been attributed to hormetic effects that are specie and strain-dependent [121,122]. Hormetic responses in fungi have been reported in the presence of metals such as Nickel [123], Mercury [124], Iron, Copper, and Zinc [125].

4.5. Cd bioaccumulation and minimum inhibitory concentration

Cd bioaccumulation (q) is specie and strain-dependent [41,66] and is a measure of the potential of microorganisms to be used in bioremediation processes and management of toxic concentrations of heavy metal in agricultural soils [126].

In bacteria, a higher q detected in P. putida GB78 suggests that this strain favors intracellular accumulation processes (Fig. 6A). In contrast, Burkholderia sp. NB10 and P. aeruginosa NB2 showed a lower q, which may be attributed to greater efficiency in extracellular Cd outflow mechanisms. The MIC is an indication of the tolerance capacity that a microorganism has to grow in the presence of Cd and highlights its potential for applications at different heavy metal concentrations in soils [127]. We find a higher tolerance in Burkholderia sp. NB10 and P. aeruginosa NB2 (140 mg kg−1) compared to P. putida GB78 (90 mg kg−1). Different Pseudomonas and Burkholderia species have been widely reported for their tolerance to Cd, other heavy metals such as Cu and Pb, and high concentrations of Zn [30,128]. Others have found MICs from 100 to 190 mg kg−1 for P. putida [129,130], up to 900 mg kg−1 for P. aeruginosa [131], and 200 mg kg−1 for Burkholderia sp. [132]. These values show the wide variation in the tolerance level in bacteria. Overall, the bacterial growth and the MIC results suggest that 18 mg kg−1 of Cd is not a limiting concentration for P. putida GB78. However, it can resist up to 90 mg kg−1 of Cd by favoring intracellular bioaccumulation. On the contrary, Burkholderia sp. NB10 and P. aeruginosa NB2, with a MIC of 140 mg kg−1 of Cd, showed growth rate reductions that may be an acclimatization strategy to maintain viability for a longer time and activate tolerance mechanisms such as efflux systems (lower q).

In fungi, the evaluation of q and RCd over 15 dpi showed that despite a small biomass development during the first days, fungi accumulated considerable amounts of Cd (RCd) with specific tendencies for each morphotype (Fig. 6).

When considering q and RCd together, reductions in q at six dpi can be attributed to the rapid dry weight gain of the fungi during phases lag, acceleration, and part of the log phase between three and six dpi (Fig. 5). This may suggest a specific dynamic of q over time, as well as a putative basal or minimum amount of RCd for each strain. This minimum amount is maintained over time from three dpi and can vary depending on the tolerance and acclimatization strategies deployed by the fungus. After 15 dpi, RCd may increase depending on biomass development and available resources in the surrounding environment. However, further evaluations are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

The averages q from six to 15 dpi are similar to previous results obtained by An et al. [121] who reported values between 3.01 and 7.89 mg g−1 and Rose and Devi [133] who found up to 7.13 mg g−1 in species from the genus Aspergillus. Nonetheless, q and RCd recorded for P. igniaria YH5 (28.39 mg g−1 and 1.52 mg, respectively) were considerably higher, which denotes a great potential of this strain to reduce the Cd availability in soils. Regarding the MIC, our results agree with previous reports where values above 1000 mg kg−1 were obtained by Woldeamanuale [36] in fungi isolated from industrial waste.

Overall, a higher dry weight in the presence of Cd, the TI, and the MIC for Annulohypoxylon sp. NH62 and P. ignaria YH5 suggest a high level of tolerance for these strains. However, P. igniaria YH5 had a higher q, and RCd compared to Annulohypoxylon NH62 which had the lowest values. Different dynamics of resistance can be outlined for these fungi. In P. igniaria YH5 a higher biomass accumulation may have allowed a higher Cd collection, and so a lower MIC compared to Annulohypoxylon NH62. In contrast, in Annulohypoxylon NH62 a higher biomass accumulation resulted in a better survival with a lower Cd accumulation, and a higher MIC (2000 mg kg−1). As described here, an inverse relationship between the tolerance level and Cd accumulation has been reported [41,110].

5. Conclusions

Cacao-cultivated soils harbor culturable Cd-tolerant fungi and bacteria with additional functional activity associated with the cycling of C, P, and N. Bacterial and fungal strains are differentially affected by the presence of Cd in soil. Burkholderia spp., Pseudomonas spp., Metarhizium sp. GH24, Annulohypoxylon sp. NH62 and P. ignaria YH5 showed high tolerance ability and strain-specific responses to Cd with MIC up to 140 Kg−1 of Cd for bacteria and 2000 Kg−1 of Cd for fungi. Our results provide new resources for further basic and applied research on cadmium management in cacao-cultivated soils. The isolation and in-vitro evaluations we conducted are initial steps for future applied experiments. Further in-vivo studies will determine the potential reduction of Cd availability and uptake by plants when using the isolated morphotypes.

Funding

This work was supported by the Cundinamarca-Colombia government (Contract No. 2 Framework Derivative Agreement of Agro-industrial Technological Corridor (No. 395 - 2012), and the Research Division of the Bogotá-Campus (DIB) and the Faculty of Agricultural Science at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia for the internal grant for research project. This work was conducted under Ministerio de Ambiente, Vivienda y Desarrollo Territorial (MAVDT) collection permit 0255, March 14, 2014.

Data availability

Has data associated with your study been deposited into a publicly available repository?

Yes. Genetic sequences of the 16S rRNA and ITS regions sequencing results are available at the NCBI according to GenBank accession numbers. Accession numbers are described in the manuscript and supplementary material. All the available data is included in either the manuscript or supplementary material. Raw datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Ethics declarations

Informed consent was not required for this study because no human or animal subjects or samples were involved in the study.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Henry A. Cordoba-Novoa: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Jeimmy Cáceres-Zambrano: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Esperanza Torres-Rojas: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Esperanza Torres Rojas reports financial support was provided by the Government of Colombia Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the cacao farmers and Yacopi technical Unit of Federación Nacional de Cacaoteros (FEDECACAO) for the sampling logistics. We thank the Cundinamarca-Colombia government (Contract No. 2 Framework Derivative Agreement of Agro-industrial Technological Corridor (No. 395 - 2012), the Research Division of the Bogotá-Campus (DIB), and the Faculty of Agricultural Science at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia for funding this research. The authors thank the Ministerio de Ambiente, Vivienda y Desarrollo Territorial (MAVDT) for the collection permit No. 0255 (March 14, 2014).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e22489.

Contributor Information

Henry A. Cordoba-Novoa, Email: henry.cordoba@mail.mcgill.ca.

Esperanza Torres-Rojas, Email: etorresr@unal.edu.co.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

References

- 1.Gramlich A., Tandy S., Gauggel C., López M., Perla D., Gonzalez V., Schulin R. Soil cadmium uptake by cocoa in Honduras. Sci. Total Environ. 2018;612:370–378. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.08.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cullen J., Maldonado T. In: Sigel A., Sigel H., Sigel R., editors. II. 2013. Biogeochemistry of cadmium and its release to the environment; pp. 31–62. (Cadmium: from Toxicity to Essentiality). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siripornadulsil S., Siripornadulsil W. Cadmium-tolerant bacteria reduce the uptake of cadmium in rice: potential for microbial bioremediation. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2013;94:94–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kirkham M.B. Cadmium in plants on polluted soils: effects of soil factors, hyperaccumulation, and amendments. Geoderma. 2006;137:19–32. doi: 10.1016/j.geoderma.2006.08.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maddela N.R., Kakarla D., García L.C., Chakraborty S., Venkateswarlu K., Megharaj M. Cocoa-laden cadmium threatens human health and cacao economy: a critical view. Sci. Total Environ. 2020:720. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amari T., Ghnaya T., Abdelly C. Nickel, cadmium and lead phytotoxicity and potential of halophytic plants in heavy metal extraction. South Afr. J. Bot. 2017;111:99–110. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2017.03.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taki M. In: Imaging and Sensing of Cadmium in Cells. Sigel A., Sigel H., Sigel R., editors. 2013. pp. 99–114. (Cadmium: from Toxicity to Essentiality). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quezada-Hinojosa R., Föllmi K.B., Gillet F., Matera V. Cadmium accumulation in six common plant species associated with soils containing high geogenic cadmium concentrations at Le Gurnigel, Swiss Jura Mountains. Catena. 2015;124:85–96. doi: 10.1016/j.catena.2014.09.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gramlich A., Tandy S., Andres C., Paniagua J.C., Armengot L., Schneider M., Schulin R. Cadmium uptake by cocoa trees in agroforestry and monoculture systems under conventional and organic management. Sci. Total Environ. 2016;580:677–686. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chavez E., He Z.L., Stoffella P.J., Mylavarapu R.S., Li Y.C., Moyano B., Baligar V.C. Concentration of cadmium in cacao beans and its relationship with soil cadmium in southern Ecuador. Sci. Total Environ. 2015;533:205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.06.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mounicou S., Szpunar J., Andrey D., Blake C., Lobinski R. Concentrations and bioavailability of cadmium and lead in cocoa powder and related products. Food Addit. Contam. 2003;20:343–352. doi: 10.1080/0265203031000077888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arévalo-gardini E., Arévalo-hernández C.O., Baligar V.C., He Z.L. Heavy metal accumulation in leaves and beans of cacao (Theobroma cacao L .) in major cacao growing regions in Peru. Sci. Total Environ. 2017;605:792–800. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.122. –606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.FAOStatistical Database . 2022. Food and Agriculture Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 14.International cocoa organization . 2018. Quarterly Bulletin of Cocoa Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 15.European Commission . Vol. 9. Official Journal of the European Union; 2014. (Commission Regulation (EU) No 488/2014 of 12 May 2014 554 Amending Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006 as Regards Maximum Levels of Cadmium in 555 Foodstuffs). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bertoldi D., Barbero A., Camin F., Caligiani A., Larcher R. Multielemental fingerprinting and geographic traceability of Theobroma cacao beans and cocoa products. Food Control. 2016;65:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2016.01.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clemens S., Aarts M.G.M., Thomine S., Verbruggen N. Plant science: the key to preventing slow cadmium poisoning. Trends Plant Sci. 2013;18:92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rai P.K., Lee S.S., Zhang M., Tsang Y.F., Kim K.H. Heavy metals in food crops: health risks, fate, mechanisms, and management. Environ. Int. 2019;125:365–385. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.01.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ashraf M.A., Hussain I., Rasheed R., Iqbal M., Riaz M., Arif M.S. Advances in microbe-assisted reclamation of heavy metal contaminated soils over the last decade: a review. J. Environ. Manag. 2017;198:132–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.04.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bravo D., Braissant O. Cadmium‐tolerant bacteria current trends and applications in agriculture. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2021:1–23. doi: 10.1111/lam.13594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahmad I., Akhtar M.J., Zahir Z.A., Naveed M., Mitter B., Sessitsch A. Cadmium-tolerant bacteria induce metal stress tolerance in cereals. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2014;21:11054–11065. doi: 10.1007/s11356-014-3010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Treesubsuntorn C., Dhurakit P., Khaksar G., Thiravetyan P. Effect of microorganisms on reducing cadmium uptake and toxicity in rice (Oryza sativa L.) Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2017:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s11356-017-9058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sinha S., Mukherjee S.K. Cadmium-induced siderophore production by a high Cd-resistant bacterial strain relieved Cd toxicity in plants through root colonization. Curr. Microbiol. 2008;56:55–60. doi: 10.1007/s00284-007-9038-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Madhaiyan M., Poonguzhali S., Sa T. Metal tolerating methylotrophic bacteria reduces nickel and cadmium toxicity and promotes plant growth of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum L.) Chemosphere. 2007;69:220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2007.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Safronova V.I., Stepanok V.V., Engqvist G.L., Alekseyev Y.V., Belimov A.A. Root-associated bacteria containing 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate deaminase improve growth and nutrient uptake by pea genotypes cultivated in cadmium supplemented soil. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 2006;42:267–272. doi: 10.1007/s00374-005-0024-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo J., Chi J. Effect of Cd-tolerant plant growth-promoting rhizobium on plant growth and Cd uptake by Lolium multiflorum Lam. and Glycine max (L.) Merr. in Cd-contaminated soil. Plant Soil. 2014;375:205–214. doi: 10.1007/s11104-013-1952-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chakraborty J., Das S. Characterization and cadmium-resistant gene expression of biofilm-forming marine bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa JP-11. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2014;21:14188–14201. doi: 10.1007/s11356-014-3308-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Y., Wu Y., Wang Q., Wang C., Wang P. Biosorption of copper, manganese, cadmium, and zinc by Pseudomonas putida isolated from contaminated sediments. Desalination Water Treat. 2014;52:7218–7224. doi: 10.1080/19443994.2013.823567. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sarma B., Acharya C., Joshi S.R. Characterization of metal tolerant Serratia spp. isolates from sediments of uranium ore deposit of domiasiat in northeast India. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India B Biol. Sci. 2016;86:253–260. doi: 10.1007/s40011-013-0236-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jin Z.M., Sha W., Zhang Y.F., Zhao J., Ji H. Isolation of Burkholderia cepacia JB12 from lead- and cadmium-contaminated soil and its potential in promoting phytoremediation with tall fescue and red clover. Can. J. Microbiol. 2013;59:449–455. doi: 10.1139/cjm-2012-0650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Asksonthong R., Siripongvutikorn S., Usawakesmanee W. Evaluation of harmful heavy metal (Hg, Pb and Cd) reduction using Halomonas elongata and Tetragenococcus halophilus for protein hydrolysate product. Functional Foods in Health and Disease. 2016;6:195–205. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen Y., Chao Y., Li Y., Lin Q., Bai J., Tang L., Wang S., Ying R., Qiu R. Survival strategies of the plant-associated bacterium Enterobacter sp. strain EG16 under cadmium stress. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016;82:1734–1744. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03689-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zafar S., Aqil F., Ahmad I. Metal tolerance and biosorption potential of filamentous fungi isolated from metal contaminated agricultural soil. Bioresour. Technol. 2007;98:2557–2561. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2006.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oladipo O.G., Awotoye O.O., Olayinka A., Bezuidenhout C.C., Maboeta M. Heavy metal tolerance traits of filamentous fungi isolated from gold and gemstone mining sites. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2018;49:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.bjm.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Puglisi I., Faedda R., Sanzaro V., Lo A.R., Petrone G., Cacciola S.O. Identification of differentially expressed genes in response to mercury I and II stress in Trichoderma harzianum. Gene. 2012;506:325–330. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.06.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woldeamanuale T.B. 2017. Evaluation of Cadmium Tolerant Fungi in the Dying Staff and Their Removal Potential; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gadd G.M., Rhee Y.J., Stephenson K., Wei Z. Geomycology: metals, actinides and biominerals. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2012;4:270–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2011.00283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sácký J., Beneš V., Borovička J., Leonhardt T., Kotrba P. Different cadmium tolerance of two isolates of Hebeloma mesophaeum showing different basal expression levels of metallothionein (HmMT3) gene. Fungal Biol. 2019;123:247–254. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2018.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kulshreshtha S., Mathur N., Bhatnagar P. Mushroom as a product and their role in mycoremediation. Amb. Express. 2014;4:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s13568-014-0029-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li X., Xiao K., Ma H., Li L., Tan H., Xu H., Li Y. Mechanisms into the removal and translocation of cadmium by Oudemansiella radicata in soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2019;26:6388–6398. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-4042-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mohammadian M., Soleimani N., Mehrasbi M., Darabian S., Mohammadi J., Ramazani A. Highly cadmium tolerant fungi: their tolerance and removal potential. J Environ Health Sci Eng. 2015;13:19. doi: 10.1186/s40201-015-0176-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raspanti E., Olga S., Gotor C., Romero L.C., García I. Chemosphere Implications of cysteine metabolism in the heavy metal response in Trichoderma harzianum and in three Fusarium species. Chemosphere. 2009;76:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao R., Guo W., Bi N., Guo J., Wang L., Zhao J., Zhang J. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi affect the growth, nutrient uptake and water status of maize (Zea mays L.) grown in two types of coal mine spoils under drought stress. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2015;88:41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2014.11.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang L., Li H., Wei H., Wu X., Ke L. Identification of cadmium-induced Agaricus blazei genes through suppression subtractive hybridization. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2014;63:84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2013.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reddy M.S., Prasanna L., Marmeisse R. 2017. Differential Expression of Metallothioneins in Response to Heavy Metals and Their Involvement in Metal Tolerance in the Symbiotic Basidiomycete Laccaria Bicolor; pp. 2235–2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cacciola S.O., Puglisi I., Faedda R., Sanzaro V., Pane A., Lo Piero A.R., Evoli M., Petrone G. Cadmium induces cadmium-tolerant gene expression in the filamentous fungus Trichoderma harzianum. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2015:98–100. doi: 10.1007/s11033-015-3924-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dhankhar R., Hooda A. Fungal biosorption – an alternative to meet the challenges of heavy metal pollution in aqueous solutions. Environ. Technol. 2011;32:467–491. doi: 10.1080/09593330.2011.572922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rodríguez Albarrcín H.S., Darghan Contreras A.E., Henao M.C. Spatial regression modeling of soils with high cadmium content in a cocoa producing area of Central Colombia. Geoderma Regional. 2019;15 doi: 10.1016/j.geodrs.2019.e00214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bravo D., Benavides-Erazo J. The use of a two-dimensional electrical resistivity tomography (2D-ERT) as a technique for cadmium determination in Cacao crop soils. Appl. Sci. 2020;10 doi: 10.3390/APP10124149. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bravo D., Pardo-Díaz S., Benavides-Erazo J., Rengifo-Estrada G., Braissant O., Leon-Moreno C. Cadmium and cadmium-tolerant soil bacteria in cacao crops from northeastern Colombia. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2018;124:1175–1194. doi: 10.1111/jam.13698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cáceres P.F.F., Vélez L.P., Junca H., Moreno-Herrera C.X. Theobroma cacao L. agricultural soils with natural low and high cadmium (Cd) in Santander (Colombia), contain a persistent shared bacterial composition shaped by multiple soil variables and bacterial isolates highly resistant to Cd concentrations. Curr Res Microb Sci. 2021;2 doi: 10.1016/J.CRMICR.2021.100086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sandoval-pineda J.F., Pérez-moncada U.A., Rodriguez A., Torres-rojas E. High cadmium concentration resulted in low arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi community diversity associated to cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) Acta Biol. Colomb. 2020;25:333–344. doi: 10.15446/abc.v25n3.78746. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Avellaneda-Torres L.M., Sicard T.L., Castro E.G., Rojas E.T. Potato cultivation and livestock effects on microorganism functional groups in soils from the neotropical high andean Páramo. Rev Bras Cienc Solo. 2020;44 doi: 10.36783/18069657rbcs20190122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mergeay M. Heavy metal resistances in microbial ecosystems. Molecular Microbial Ecology Manual. 1995:439–455. doi: 10.1007/978-94-011-0351-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bressan M., Trinsoutrot Gattin I., Desaire S., Castel L., Gangneux C., Laval K. A rapid flow cytometry method to assess bacterial abundance in agricultural soil. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2015;88:60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2014.12.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen W., Kuo T. A simple and rapid method for the preparation of gram-negative bacterial genomic DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21 doi: 10.1093/nar/21.9.2260. 2260–2260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Saitou N., Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Society for the Study of Evolution Stable. 1985;39:783–791. doi: 10.2307/2408678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kumar S., Stecher G., Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Avellaneda-Torres L.M., Guevara C.P., Torres E. Assessment of cellulolytic microorganisms in soils of Nevados Park, Colombia. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2014;45:1211–1220. doi: 10.1590/s1517-83822014000400011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Paul N.B., Sundara W.V.B. Phosphate-dissolving bacteria in the rhizosphere of some cultivated legumes. Plant Soil. 1971;35:127–132. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Paul N., Rao W. Vol. 132. Indian Agricultural Research Institute; 1971. pp. 127–132. (Phosphate-dissolving Rhizobacteria in the Legumes of Some Cultivated, Division of Microbiology). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rennie R.J. A single medium for the isolation of acetylene-reducing (dinitrogen-fixing) bacteria from soils. Can. J. Microbiol. 1981;27:8–14. doi: 10.1139/m81-002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ivanova E.P., Kurilenko V.V., Kurilenko A.V., Gorshkova N.M., Shubin F.N., Nicolau D.V., Chelomin V.P. Tolerance to cadmium of free-living and associated with marine animals and eelgrass marine gamma-proteobacteria. Curr. Microbiol. 2002;44:357–362. doi: 10.1007/s00284-001-0017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cristani M., Naccari C., Nostro A., Pizzimenti A., Trombetta D., Pizzimenti F. Possible use of Serratia marcescens in toxic metal biosorption (removal) Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2012;19:161–168. doi: 10.1007/s11356-011-0539-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Micheletti E., Colica G., Viti C., Tamagnini P., De Philippis R. Selectivity in the heavy metal removal by exopolysaccharide-producing cyanobacteria. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2008;105:88–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.03728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kabata-Pendias A., Pendias H. fourth ed. CRC Press; Boca Raton.: 2011. Trace Elements in Soils and Plants. [Google Scholar]

- 68.IGAC . Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi - IGAC, Bogotá D.C.; 2000. Estudio general de suelos y zonificación de tierras del departamento de Cundinamarca. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Eruola A., Azike N. Assessment of the effects of cadmium and lead on pH and cation exchange capacity of soil under different plant canopt in the tropical wet-and dry climate. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;6(11):951–952. 4. 2013–2015. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rolka E., Wyszkowski M. Availability of trace elements in soil with simulated cadmium, lead and zinc pollution. Minerals. 2021;11 doi: 10.3390/min11080879. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nogueira T.A.R., Abreu-Junior C.H., Alleoni L.R.F., He Z., Soares M.R., dos Santos Vieira C., Lessa L.G.F., Capra G.F. Background concentrations and quality reference values for some potentially toxic elements in soils of São Paulo State, Brazil. J. Environ. Manag. 2018;221:10–19. doi: 10.1016/J.JENVMAN.2018.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bravo D., Leon-Moreno C., Martínez C.A., Varón-Ramírez V.M., Araujo-Carrillo G.A., Vargas R., Quiroga-Mateus R., Zamora A., Rodríguez E.A.G. The first national survey of cadmium in cacao farm soil in Colombia. Agronomy. 2021;11:1–18. doi: 10.3390/agronomy11040761. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tipayno S.C., Truu J., Samaddar S., Truu M., Preem J.K., Oopkaup K., Espenberg M., Chatterjee P., Kang Y., Kim K., Sa T. The bacterial community structure and functional profile in the heavy metal contaminated paddy soils, surrounding a nonferrous smelter in South Korea. Ecol. Evol. 2018;8:6157–6168. doi: 10.1002/ece3.4170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Azarbad H., Niklińska M., Laskowski R., van Straalen N.M., van Gestel C.A.M., Zhou J., He Z., Wen C., Röling W.F.M. Microbial community composition and functions are resilient to metal pollution along two forest soil gradients. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2015;91:1–11. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiu003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Limcharoensuk T., Sooksawat N., Sumarnrote A., Awutpet T., Kruatrachue M., Pokethitiyook P., Auesukaree C. Bioaccumulation and biosorption of Cd2+ and Zn2+ by bacteria isolated from a zinc mine in Thailand. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2015;122:322–330. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2015.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bruins M.R., Kapil S., Oehme F.W. Microbial resistance to metals in the environment. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2000;45:198–207. doi: 10.1006/eesa.1999.1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mounaouer B., Nesrine A., Abdennaceur H. Identification and characterization of heavy metal-resistant bacteria selected from different polluted sources. Desalination Water Treat. 2014;52:7037–7052. doi: 10.1080/19443994.2013.823565. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sharma R.K., Archana G. Cadmium minimization in food crops by cadmium resistant plant growth promoting rhizobacteria. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2016;107:66–78. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2016.05.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Etesami H. Bacterial mediated alleviation of heavy metal stress and decreased accumulation of metals in plant tissues: mechanisms and future prospects. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018;147:175–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2017.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Spain A.M., Krumholz L.R., Elshahed M.S. Abundance, composition, diversity and novelty of soil Proteobacteria. ISME J. 2009;3:992–1000. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2009.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Xiao S., Zhang Q., Chen X., Dong F., Chen H., Liu M., Ali I. Speciation distribution of heavy metals in uranium mining impacted soils and impact on bacterial community revealed by high-throughput sequencing. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:1–15. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chen Y., Jiang Y., Huang H., Mou L., Ru J., Zhao J., Xiao S. Long-term and high-concentration heavy-metal contamination strongly influences the microbiome and functional genes in Yellow River sediments. Sci. Total Environ. 2018:1400–1412. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.05.109. 637–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Castanheira N., Dourado A.C., Kruz S., Alves P.I.L., Delgado-Rodríguez A.I., Pais I., Semedo J., Scotti-Campos P., Sánchez C., Borges N., Carvalho G., Barreto Crespo M.T., Fareleira P. Plant growth-promoting Burkholderia species isolated from annual ryegrass in Portuguese soils. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2016;120:724–739. doi: 10.1111/jam.13025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Qiu Z., Tan H., Zhou S., Cao L. Enhanced phytoremediation of toxic metals by inoculating endophytic Enterobacter sp. CBSB1 expressing bifunctional glutathione synthase. J. Hazard Mater. 2014;267:17–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2013.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Marteinsson V., Klonowski A., Reynisson E., Vannier P., Sigurdsson B.D., Ólafsson M. Microbial colonization in diverse surface soil types in Surtsey and diversity analysis of its subsurface microbiota. Biogeosciences. 2015;12:1191–1203. doi: 10.5194/bg-12-1191-2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rojjanateeranaj P., Sangthong C., Prapagdee B. Enhanced cadmium phytoremediation of Glycine max L . through bioaugmentation of cadmium-resistant bacteria assisted by biostimulation. Chemosphere. 2017;185:764–771. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.07.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lin X., Mou R., Cao Z., Xu P., Wu X., Zhu Z., Chen M. Characterization of cadmium-resistant bacteria and their potential for reducing accumulation of cadmium in rice grains. Sci. Total Environ. 2016:569–570. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.06.121. 97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Achal V., Pan X., Zhang D. Bioremediation of strontium (Sr) contaminated aquifer quartz sand based on carbonate precipitation induced by Sr resistant Halomonas sp. Chemosphere. 2012;89:764–768. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gupta P., Diwan B. Bacterial Exopolysaccharide mediated heavy metal removal: a Review on biosynthesis, mechanism and remediation strategies. Biotechnology Reports. 2017;13:58–71. doi: 10.1016/j.btre.2016.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Murugavelh S., Mohanty K. Bioreduction of hexavalent chromium by free cells and cell free extracts of Halomonas sp. Chemical Engineering Journal Journal. 2012;203:415–422. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2012.07.069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]