Abstract

Background

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has a benign course in several patients; however, a serious form of this disease can turn into liver failure, liver cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma.

Aim

This study aims to estimate the prevalence of NAFLD in Iran.

Method

We searched the following databases from January 2000 to December 2022: Scopus, Pubmed/Medline, Embase, Web of Sciences, the Cochrane Library, and Google Scholar also a number of Iranian databases, namely MagIran, SID, and Elmnet. Additionally, the quality of the included studies was evaluated through the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. We estimated heterogeneity between studies using the I2 statistic. Furthermore, we performed a synthesis of prevalence estimates through the random-effects DerSimonian and Laird model across the included studies with a 95% confidence interval. To assess the publication bias, we also used Egger's test.

Results

Thirty-one studies were eligible for inclusion. The overall number of participants in the present study was 41,971. The overall prevalence of NAFLD in Iran was 33% [CI: 27–37%], with I2 = 99.7% (P < 0.01). The prevalence was 35% [CI: 27–43%] and 37% [CI: 27–47%] in males and females, respectively. We used Egger's test, and no significant publication bias was identified in the overall prevalence (P = 0.45).

Conclusion

According to the results of this study, the prevalence of NAFLD in Iran is not only high but alsoa growing trend. Effective strategies for changing lifestyles, changing eating habits, and encouraging physical activities among Iranians are recommended. Also, providing screening tests, especially among high-risk groups, has a significant effect on early diagnosis and NAFLD control.

Keywords: non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, Iran, prevalence, met-analysis, systematic review

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a significant challenge for health systems worldwide and accounts for an important part of liver problems.1 NAFLD has a benign course in several patients; however, a serious form of this disease can turn into liver failure, liver cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).2 Also, NAFLD is linked with extrahepatic conditions, namely type 2 diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, dyslipidemia, chronic kidney diseases, cardiovascular diseases, and obesity.3,4 Recent data has revealed that NAFLD has been increasing worldwide over the past few years, which has subsequently led to increased economic costs for health systems.5 In this regard, research has demonstrated that poor lifestyle, inactivity, high carbohydrate and high fat intake, and poor diet are positively related to the prevalence of NAFLD.6

Despite the high rate of NAFLD worldwide, its prevalence seems to be heterogeneous from one country to another.7 The rate of NAFLD soared from about 391 million cases in 1990 to about 882 million cases in 2017, and its prevalence increased from 8.2 to 10.9, with North Africa and the Middle East having the highest prevalence.8 In the same vein, NAFLD has been a health challenge in Iran; in this regard, various studies have investigated the causes and prevalence of NAFLD in Iran. Having updated knowledge regarding the trend and epidemiological information of the disease might help Iranian health policy-makers and stakeholders understand the disease burden better and predict its process; this way, they would implement programs and policies needed to prevent and control NAFLD. Given the numerous challenges imposed by NAFLD on the Iranian health system, we conducted the present study to examine the prevalence of NAFLD in Iran. The purpose of this study is to investigate the prevalence based on the published studies conducted on the prevalence of NAFLD in Iran.

Main text

Methods

In the present systematic review, we followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Appendix).9 Also, we registered the protocol of this review in PROSPERO (CRD42022363598)10; the protocol was also approved by the Review Ethics Board of Iran University of Medical Sciences (IR.IUMS.REC.1401.383).

Search Strategy

Two authors of the present paper independently searched the following databases: Scopus, Pubmed/Medline, Embase, Web of Sciences, the Cochrane Library, and Google Scholar, as well as Iranian databases MagIran, SID, and Elmnet, from January 2000 to December 2022. Also, we used Boolean operators with the following related keywords: (Prevalence OR Epidemiology OR Frequency OR Incidence) AND (Non-alcoholic fatty liver OR Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease OR non-alcoholic fatty OR nonalcoholic fatty liver OR nonalcoholic fatty liver disease OR nonalcoholic steatohepatitis OR non-alcoholic steatohepatitis OR MAFLD OR NAFLD OR non-alcoholic) AND (Iran). In addition, two researchers (MaB and SS) from the present study independently reviewed the reference lists of articles to find more related studies. We resolved any discrepancy between the two researchers by consulting a third researcher (SPT) on our team.

Inclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria in the present study are as follows:

-

1.

Observational studies that reported the prevalence of NAFLD in different populations.

-

2.

Studies published in Farsi and English.

-

3.

Studies that investigated patients who resided in Iran.

-

4.

Studies with sufficient data to calculate prevalence.

-

5.

Studies published in peer-reviewed journals.

-

6.

Studies that focused on patients who were diagnosed with serum-based indicators, imaging, liver biopsy, and ultrasound.

-

7.

Studies that had no gender or age restrictions.

Exclusion Criteria

Also, we followed the exclusion criteria below.

-

1.

Studies whose designs were controlled trials, case series, and case reports, as well as books, posters, oral presentations, letters to the editor, and opinion articles.

-

2.

Studies with alcoholic patients.

-

3.

Studies with patients who resided outside of Iran.

-

4.

Studies that had insufficient data.

-

5.

Studies whose data were replicated.

-

6.

Studies whose full texts were not available.

Data Extraction

We developed a data extraction form including the following information: the first author's name, publication year, mean or range age of participants, place where the study was conducted, study design, test used for diagnosing NAFLD, number of patients, reported prevalence, and the number of NAFLD patients according to their gender. In the next step, two researchers (SA and NLB) from the present study independently extracted the data from the selected studies and entered it into the data extraction form. We resolved discrepancies between the two reviewers by consensus or by consulting a third researcher (MM) from this study.

Quality Assessment of the Included Studies

The quality of included studies was evaluated through the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS),11 which has three domains: selection, comparability, and outcome. Based on the NOS scores, we classified the selected studies into three groups as follows: scores ranging from 7 to 9 were considered low risk of bias (high quality), scores of 4–6 were moderate risk of bias (fair quality), and scores of 1–3 were considered high risk of bias (low quality). Two authors (MeB and AR) of this study independently reviewed each study to assess the risk of bias. Any disputes among the reviewers are resolved by consensus or via consulting with a third author (SJE).

Statistical Analysis

We analyzed the data using Stata Software (version 12), with the statistical significance set at P < 0.05. Also, we estimated heterogeneity between studies using the I2 statistic. Meanwhile, we performed a synthesis of prevalence estimates using the random-effects DerSimonian and Laird model across the included studies with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Furthermore, we used Egger's test to assess for publication bias. We also performed a sensitivity analysis to ensure the stability of the results. In order to evaluate the causes of the heterogeneity of the included studies, we included the participants' gender, type of participants, sample size, year of publication, diagnostic test, setting, obese and non-obese populations, risk of bias, and geographic region of the subgroup. Also, we performed the meta-regression test according to the year of publication, sample size, and mean age.

Results

Study Selection

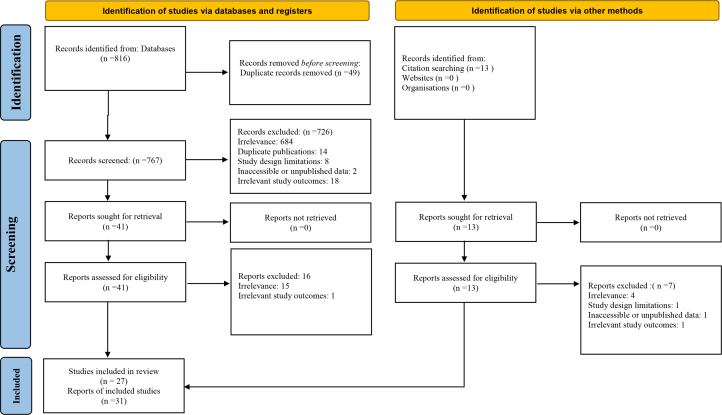

A total of 829 records were identified in the comprehensive search. After the exclusion of duplicates and non-relevant records, thirty-one studies were included in the review.12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42 Figure 1 gives more details regarding the selection process for the included studies.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Characteristics of the Included Studies

The overall number of participants in the included studies was 41,971, with a sample size ranging from 34 to 7723 participants. Also, all the studies had a cross-sectional design. In addition, an ultrasound test was used to diagnose the NAFLD patients. Table 1 presents the characteristics of the included studies.

Table 1.

The Main Characteristics of the Included Studies.

| First author | Year | City | Mean or range age | Sample size | Diagnostic test | Prevalence (%) | Conditions of participants | Setting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Savadkoohi F | 2003 | Zahedan | 43.6 ± 8.9 | 247 | Ultrasound | 32.8 | Population based | OPD visitors |

| Hosseinpanah F | 2007 | Tehran | 60 ± 9 | 76 | Ultrasound | 82.9 | Type 2 diabetes | Hospital based |

| Alavian SM | 2008 | Tehran | 41.61 ± 12.04 | 1120 | Fatty liver index or hepatic steatosis index | 9.5 | School-aged children and adolescents | Public health centers |

| Jamali R | 2008 | Golestan | 40.59 ± 14.69 | 2049 | Ultrasound | 2.04 | Population based | OPD visitors |

| Merat S | 2009 | Tehran | 56.56 ± 10.5 | 172 | Ultrasound | 55.8 | Type 2 diabetes | Hospital based |

| Adibi A | 2009 | Isfahan | 12.59 ± 3.25 | 949 | Ultrasound | 16.9 | Overweight and obese children | Hospital based |

| Alavian SM | 2009 | Tehran | 15 ± 2.3 | 966 | Ultrasound | 7.1 | Hepatitis B patients | Blood transfusion Center |

| Rafeey M | 2009 | Tabriz | 6.53 ± 3.07 | 1500 | Ultrasound | 2.3 | Children | OPD visitors |

| Tazhibi M | 2010 | Isfahan | 6–18 | 1107 | Ultrasound | 16.9 | Children and adolescence | Public health centers |

| Sohrabpour AA | 2010 | Tehran-Hormozgan-Golestan | 36.1 ± 13.1 | 5589 | Fatty liver index or hepatic steatosis index | 2.9 | Population based | OPD visitors |

| Shahbazian HB | 2011 | Ahvvaz | 51 ± 10 | 272 | Ultrasound | 70 | Type 2 diabetes | Hospital based |

| Hosseini SM | 2011 | Isfahan | 12.57 ± 3.3 | 962 | Ultrasound | 16.8 | Children and adolescence | OPD visitors |

| Razavizade M | 2012 | Kashan | 41.63 ± 11.46 | 245 | Ultrasound | 78.4 | Population based | OPD visitors |

| Lahsaee S | 2012 | Kerman | 31.76 ± 11.31 | 1993 | Fatty liver index or hepatic steatosis index | 16 | Population based | Blood transfusion Center |

| Shiasi Arani K | 2013 | Kashan | 9.55 ± 2.3 | 306 | Ultrasound | 55.3 | Children and adolescence | Public health centers |

| Bagheri Lankarani K | 2013 | Shiraz | 43.1 ± 14.1 | 819 | Ultrasound | 21.5 | Population based | Hospital based |

| Eshraghian A | 2013 | Shiraz | 48.20 ± 12.32 | 832 | Ultrasound | 15.3 | Population based | Public health centers |

| Montazerifar F | 2014 | Zahedan | 16 ± 2 | 34 | Ultrasound | 44.11 | Obese adolescant | Public health centers |

| Saki F | 2014 | Shiraz | 10.57 ± 3.04 | 102 | Ultrasound | 54.9 | Obese Children | OPD visitors |

| Jafarian A | 2014 | Tehran | 33 | 116 | Fatty liver index or hepatic steatosis index | 12 | Cadaveric Organ Donor Population | Hospital based |

| Amirkalali B | 2014 | Amol | 45.35 ± 15.87 | 5023 | Ultrasound | 43.8 | Population based | Public health centers |

| Karimi-Sari H | 2015 | Tehran | 33.96 ± 9.92 | 114 | Fatty liver index or hepatic steatosis index | 16.7 | Sleeve Bariatric Surgery | Hospital based |

| Taghavi Ardakani A | 2015 | Kashan | 9.07 ± 1.88 | 200 | Ultrasound | 59 | Obese Children | OPD visitors |

| Ostovaneh MR | 2015 | Amol-Zahedan | 37.27 ± 0.40 | 7723 | Ultrasound | 35.2 | Population based | Public health centers |

| Adibi A | 2017 | Isfahan | 45.53 ± 8.92 | 483 | Ultrasound | 39.3 | Population based | Public health centers |

| Rabiee B | 2017 | Amol | 48.15 ± 13.41 | 5052 | Ultrasound | 21.4 | Population based | Public health centers |

| Heidari Z | 2017 | Zahedan | 50.79 ± 10.49 | 255 | Ultrasound | 86.6 | Type 2 diabetes | Public health centers |

| Namakin K | 2018 | Birjand | 12 to 18 | 200 | Ultrasound | 54 | Overweight and obese children | OPD visitors |

| Hosseini Ahangar B | 2019 | Tehran | 43.28 ± 14.03 | 999 | Ultrasound | 19.6 | Population based | Hospital based |

| Etminani R | 2020 | Isfahan | 45.5 ± 8.6 | 413 | Ultrasound | 39.3 | Middle-Aged | Public health centers |

| Amirkalali B | 2021 | Amol | 16 to 65 | 2308 | Ultrasound | 46·7 | Lean and non-lean populations | Hospital based |

OPD, outpatient department.

Overall Prevalence of NAFLD

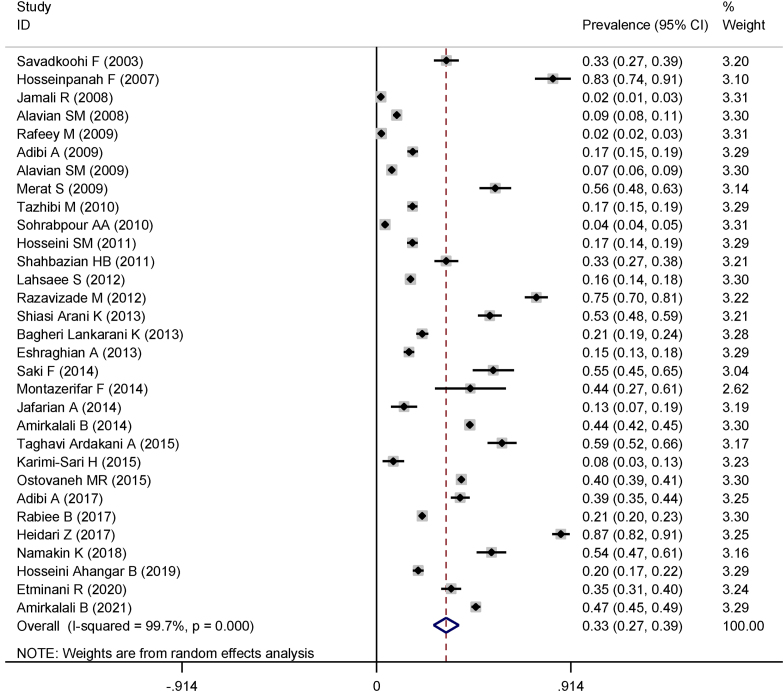

According to the random model, the overall prevalence of NAFLD in Iran was 33% [CI: 27–39%], with I2 = 99.7% (P < 0.01). The prevalence was 35% [CI: 27–43%] and 37% [CI: 27–47%] in males and females, respectively. Figure 2 shows the overall prevalence of NAFLD in Iran.

Figure 2.

NAFLD prevalence in Iran.

Risk of Bias

Table 2 shows the NOS quality assessment scores of the included studies, with a mean score of 6.65. According to the results, 20 studies were considered high quality (low risk) and 11 were moderate (fair risk). The prevalence was 32% [CI: 24–40%] and 34% [CI: 24–44%] in high-quality (low risk) and moderate (fair risk) studies, respectively.

Table 2.

Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment.

| First author | Year | Representativeness (0,1,2) | Sample size (0,1) | Diagnostic tool (0,1,2) | Comparability of study population (0,2) | Outcome assessment (0,1) | Statistical test (0,1) | Total score (0–9) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Savadkoohi | 2003 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Hosseinpanah | 2007 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Alavian | 2008 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Jamali | 2008 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Merat | 2009 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Adibi | 2009 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Alavian | 2009 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Rafeey | 2009 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Tazhibi | 2010 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Sohrabpour | 2010 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Shahbazian | 2011 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Hosseini | 2011 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Razavizade | 2012 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Lahsaee | 2012 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Shiasi Arani | 2013 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Bagheri Lankarani | 2013 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Eshraghian | 2013 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Montazerifar | 2014 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Saki | 2014 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Jafarian | 2014 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Amirkalali | 2014 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Karimi-Sari | 2015 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Taghavi Ardakani | 2015 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Ostovaneh | 2015 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Adibi | 2017 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Rabiee | 2017 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Heidari | 2017 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Namakin | 2018 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Hosseini Ahangar | 2019 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Etminani | 2020 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Amirkalali | 2021 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

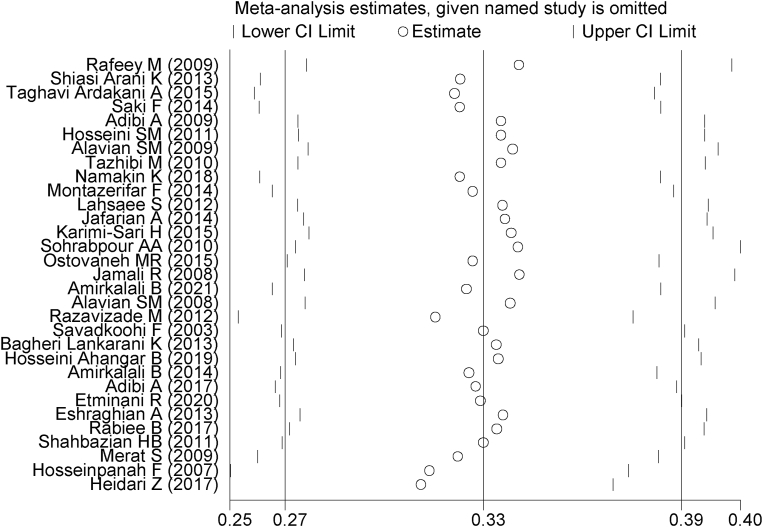

Also, Figure 3 shows the results of the sensitivity analysis, confirming that the findings were stable. In addition, we conducted a subgroup analysis. Table 3 shows the prevalence by obesity status, publication year, geographic region, setting, type of participants, diagnostic test, sex, and sample size in the included studies.

Figure 3.

Sensitivity analysis.

Table 3.

Results of Subgroup Analysis.

| Variables | Prevalence (CI 95%) | I2 (%) | Number of studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Obesity status (Total) | |||

| Overweight and obese | 33 (15–51) | 99.9 | 7 |

| Non-obese | 32 (27–38) | 99.6 | 24 |

| Year of publication | |||

| 2000–2005 | 33 (27–39) | 0 | 1 |

| 2006–2010 | 18 (14–22) | 99.1 | 9 |

| 2011–2015 | 35 (27–43) | 99.3 | 14 |

| 2016–2022 | 43 (28–58) | 99.5 | 7 |

| Regional | |||

| West | 2 (2–3) | 0 | 13 |

| East | 52 (30–73) | 99.2 | 5 |

| North | 26 (17–34) | 99.8 | 12 |

| South | 34 (27–42) | 98.7 | 1 |

| Participants | |||

| Children | 28 (19–36) | 99.6 | 22 |

| Adults | 35 (27–43) | 99.7 | 9 |

| Diagnostic test | |||

| Ultrasound | 32 (25–38) | 99.7 | 26 |

| Others | 39 (18–61) | 99.6 | 5 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 35 (27–43) | 99.4 | 19 |

| Female | 37 (27–47) | 99.6 | 19 |

| Sample size | |||

| Sample size ≤1000 | 39 (30–48) | 99.2 | 21 |

| Sample size >1000 | 20 (11–30) | 99.9 | 10 |

| Health status | |||

| Without disease | 28 (22–34) | 99.7 | 27 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 65 (37–92) | 98.8 | 4 |

| Obesity status (Children) | |||

| Non obese | 11 (3–18) | 98.9 | 4 |

| Overweight and obese | 48 (26–69) | 98.8 | 5 |

| Obesity status (Adults) | |||

| Non obese | 25 (10 61) | 99.8 | 2 |

| Overweight and obese | 34 (26–43) | 94 | 20 |

| Level of quality of studies | |||

| Low risk of bias (high quality) | 32 (24–40) | 99.5 | 20 |

| Moderate risk of bias (fair quality) | 3424, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44 | 96.9 | 11 |

| Setting | |||

| OPD visitors | 57 (42–73) | 99.7 | 9 |

| Hospital based | 61 (58–84) | 99.8 | 9 |

| Public health center | 71 (60–82) | 99.7 | 11 |

| Blood transfusion Center | 53 (44–97) | 90 | 2 |

OPD, outpatient department

The prevalence of NAFLD was found in both obese or overweight patients (33%), and non-obese individuals (32%). However, the prevalence varied based on the year of publication, with studies published between 2000 and 2005 reporting a prevalence of 33%, studies published between 2011 and 2015 reporting a prevalence of 18%, and studies published between 2016 and 2020 reporting a higher prevalence of 43%. When considering geographical regions, we observed that the prevalence of NAFLD in the west, east, north, and south of Iran was 2%, 52%, 26%, and 34%, respectively. Additionally, we found that the prevalence of NAFLD was higher in studies with smaller sample sizes (39% in studies with a sample size of ≤1000) compared to those with larger sample sizes (20% in studies with a sample size >1000). Furthermore, the prevalence of NAFLD varied based on the data collection method. Studies based on outpatient department (OPD) visitors reported a prevalence of 57%, while studies based on hospital-based data reported a prevalence of 61%. Studies based on public health centers reported the highest prevalence of NAFLD at 71%.

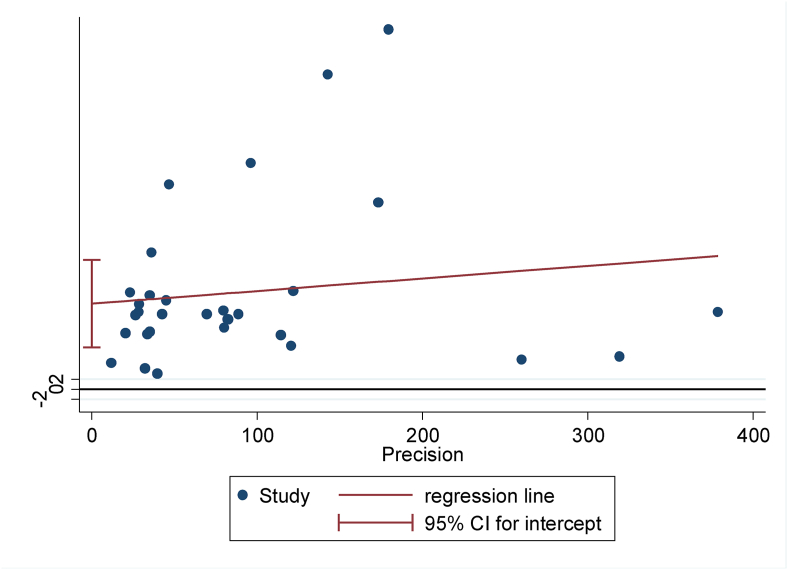

According to the publication year (P = 0.19) and age of participants (P = 0.25), meta-regression increased; however, it decreased based on the sample size (P = 0.21). But none of them was statistically significant. Also, the results of Egger's test show no significant publication bias in the overall prevalence (P = 0.45) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Publication bias.

In some of the included studies, participants had comorbidities such as type 2 diabetes, hepatitis B, and other diseases. Additionally, some studies included children as participants, which limits the generalizability of the results to the overall population. To address this issue, we performed an analysis using population-based samples only. The overall prevalence was 43% [CI: 31–55%].

Discussion

We investigated the prevalence of NAFLD in Iran in the present study. Results revealed that the overall prevalence of this disease was 33%, with prevalences of 34% and 31% in adults and children, respectively. In this regard, the prevalence of NAFLD in Iran is lower than in Chile (39.4%),43 India (38.6%),44 South Korea (51.4%),45 and Turkey (48.3%).46 However, Younossi et al.47 reported a lower prevalence of NAFLD (25.24%). Also, compared to other studies conducted in Israel (30%)48 and Italy (20%),49 the prevalence of NAFLD in Iran was higher. We think that this difference in prevalence across countries might be because of lifestyle, demographic characteristics, and health services related to treatment, as well as the studied populations and methods for diagnosing fatty liver.50

Results also showed that ultrasound was used in 84% of studies for diagnosing NAFLD. Also, the prevalence of NAFLD based on the ultrasound test was 32%, and other methods were 39%. In addition, the ultrasound method has been reported to be non-invasive, accurate, detailed, painless, accessible, and safe for all patients.51 In Iran, the ultrasound diagnostic method is also commonly used because of its high sensitivity and specificity, easy access, and appropriate insurance coverage.52

In recent years, the lifestyle in Iran has changed, and people have become less active. Also, the consumption of carbonated drinks and sweets, the use of fatty foods, and fast foods have become common in Iran, leading to a dramatic increase in obesity that might justify the increasing trend of NAFLD in Iran in recent years.53 In this regard, about 29 million Iranians are suffering from obesity and overweight, and 85% of the population was sedentary at the time of writing this manuscript.54

Our findings showed that the prevalence of NAFLD was higher in obese and overweight people, which was consistent with the findings of other studies.46, 47, 48, 54 Also, various studies have shown that there is a positive correlation between obesity and NAFLD;55,56 therefore, controlling obesity through public education and lifestyle modification could be a sound measure.57

The findings of our study revealed that the highest prevalence of NAFLD was observed on the western side of the country, with a rate of 52%. The western provinces of Iran are the most important sources of livestock breeding and red meat production, and their consumption is also very high in these provinces. In this regard, Hashemian et al. argued that the prevalence of NAFLD is positively related to the amount of red meat consumption.58 Alongside, this several studies reported that red meat consumption is associated with an increased risk of NAFLD.59,60 Red meat can accelerate obesity, and as a result, people will be prone to various diseases, including NAFLD.61 Therefore, a change in eating habits and reducing the amount of red meat consumption might be effective in decreasing the prevalence of NAFLD.62,63

In the present study, the prevalence of NAFLD was higher in women than men which is consistent with the findings of Summart et al.64 The high prevalence of NAFLD in women can be attributed to fat distribution, their physiology, and sex hormones.65 In this regard, nutritionists argue that the hormonal changes in women after menopause and lack of estrogen and progesterone hormones increase the appetite in women that might lead to obesity.66,67 In the same vein, most Iranian women's obesity is due to eating habits as well as being inactive.68 Also, obesity after pregnancy is pervasive in Iran.42

Although NAFLD affects people of any age, even in children,69 the findings of the present study show that the prevalence of NAFLD in adults was higher than that in children, which is in alignment with the findings of precursory studies.70, 71, 72 In this regard, it has been argued that lack of proper physical activity, accumulation of fat in the body, smoking, and various diseases can increase the potential risk of NAFLD in adults, especially in the adults.73

Also, the findings of our study show that the prevalence of NAFLD in type 2 diabetic patients is 2.3 times higher compared to healthy people, which is consistent with the results of studies conducted in other countries.46,64 Due to the fact that the management of type 2 diabetes is very difficult when it coincides with NAFLD, we thus recommend screening type 2 diabetic patients for NAFLD thoroughly.74 It is noteworthy to mention that the prevalence of type 2 diabetes in Iran in people over 40 years old is about 24%, which might be a further cause of the prevalence of NAFLD.75

To reduce the prevalence of NAFLD in Iran, the following policies and programs have been implemented: raising taxes on fast foods, sugary foods, and soft drinks; food labeling; financial supports for factories that produce healthy food; and the establishment of a public sports federation to encourage people to be more physically active.76

Limitations and further research

The present study has two limitations. First, the included studies did not have a homogeneous population under investigation. Second, the diversity of diagnostic tests used, different age groups, and risk factors examined can also be the cause of the heterogeneity in the present study. As Iran has a variety of geographical regions and social classes and, in some provinces, no valid study on the prevalence of NAFLD has yet been conducted, we believe that more research is needed in this area.

The results of the present study demonstrated that the prevalence of NAFLD in Iran is not only high but also growing. Also, the cost of NAFLD epidemics might be very damaging to the health system; thus, we argue that a comprehensive NAFLD management program is required. In this regard, effective strategies for changing lifestyles, changing eating habits, and encouraging physical activities among Iranians are recommended. Also, providing screening tests, especially among high-risk groups, can play an important role in early diagnosis and NAFLD control.

Credit authorship contribution statement

SPT, MaB, MeB, MS, and SA: Conceptualiz and design. MaB, and SA: Data curation. MaB, SA and NLB: Formal analysis. AR, MM, SS, AS, AT and MaB: Investigation. SPT, NLB and MaB: Methodology. SPT, MaB: Project administration. MeB, AR, SA, MM, SS, AS, AT and MaB: Resources. MaB, and NLB: Software. SPT and MaB: Supervision. MeB, AR, SA, MM, SS, AS, AT and MaB: Validation. MeB and SPT: Visualization. MeB and SPT: Roles/Writing - original draft. MaB, AR, SJE and NLB: Writing - review & editing. None: Funding acquisition.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocol was also approved by the Review Ethics Board of the Iran University of Medical Sciences (IR.IUMS.REC.1401.383).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jceh.2023.06.009.

Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

References

- 1.Liu J., Tian Y., Fu X., et al. Estimating global prevalence, incidence, and outcomes of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease from 2000 to 2021: systematic review and meta-analysis. Chin Med J. 2022;135:1682–1691. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000002277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li J., Zou B., Yeo Y.H., et al. Prevalence, incidence, and outcome of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Asia, 1999-2019: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4:389–398. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30039-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byrne C.D., Targher G. NAFLD: a multisystem disease. J Hepatol. 2015;62(1 suppl l):S47–S64. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Behairy M.A., Sherief A.F., Hussein H.A. Prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease among patients with non-diabetic chronic kidney disease detected by transient elastography. Int Urol Nephrol. 2021;53:2593–2601. doi: 10.1007/s11255-021-02815-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee J., Kim T., Yang H., Bae S.H. Prevalence trends of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease among young men in Korea: a Korean military population-based cross-sectional study. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2022;28:196–206. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2021.0371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saha M., Hossain M.Z., Gope S., et al. Prevalence of sonologically detected non-alcoholic fatty liver disease among school children of sylhet city. Mymensingh Med J. 2022;31:412–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kang S.Y., Kim Y.J., Park H.S. Trends in the prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and its future predictions in Korean men, 1998-2035. J Clin Med. 2020;9:2626. doi: 10.3390/jcm9082626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ge X., Zheng L., Wang M., Du Y., Jiang J. Prevalence trends in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease at the global, regional and national levels, 1990-2017: a population-based observational study. BMJ Open. 2020;10 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-036663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G., PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Behzadifar M., Bragazzi N.L., Tabaeian S.P. 2022. The Prevalence of Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Iran: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42022363598 [Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lo C.K., Mertz D., Loeb M. Newcastle-Ottawa Scale: comparing reviewers' to authors' assessments. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Savadkouhi F., Hosseini Tabatabaei S., Shahabi Nezhad S. The frequency of fatty liver in sonography of patients without liver diseases background and its correlation with blood cholesterol and triglyceride. Tabib-e-Shargh. 2003;5:177–183. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hosseinpanah F., Rambod M., Sadeghi L. Predictors of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in type 2 diabetes. Internet J Endocrinol. 2007;2:61–69. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alavian S., Ramezani M., Bazzaz A., Azizabadi Farahani M., Behnava B., Keshvari M. Frequency of fatty liver and some of its risk factors in asymptomatic carriers of HBV attending the tehran blood transfusion organization hepatitis clinic. Iranian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2008;10:99–106. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jamali R., Khonsari M., Merat S., et al. Persistent alanine aminotransferase elevation among the general Iranian population: prevalence and causes. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:2867–2871. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.2867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adibi A., Kelishadi R., Beihaghi A., Salehi H., Talaei M. Sonographic fatty liver in overweight and obese children, a cross sectional study in Isfahan. Endokrynol Pol. 2009;60:14–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alavian S.M., Mohammad-Alizadeh A.H., Esna-Ashari F., Ardalan G., Hajarizadeh B. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease prevalence among school-aged children and adolescents in Iran and its association with biochemical and anthropometric measures. Liver Int. 2009;29:159–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merat S., Yarahmadi S., Tahaghoghi S., et al. Prevalence of fatty liver disease among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients and its relation to insulin resistance. Middle East J Dig Dis. 2009;1:74–79. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rafeey M., Mortazavi F., Mogaddasi N., Robabeh G., Ghaffari S., Hasani A. Fatty liver in children. Therapeut Clin Risk Manag. 2009;5:371–374. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.s4467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sohrabpour A., Rezvan H., Amini-Kafiabad S., Dayhim M., Merat S., Pourshams A. Prevalence of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in Iran: a population based study. Middle East J Dig Dis. 2010;2:14–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tazhibi M., Kelishadi R., Khalili Tahmasebi H., A.A., et al. Association of lifestyle with metabolic syndrome and non-Alcoholic fatty liver in children and adolescence. Bimonthly Journal of Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences. 2010;14:115–123. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hosseini S.M., Mousavi S., Poursafa P., Kelishadi R. Risk score model for predicting sonographic nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children and adolescents. Iran J Pediatr. 2011;21:181–187. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shahbazian H.B., Hashemi S.J., Latifi S.M., Lashkarara G., Alizadeh Attar G. Prevalence of fatty liver disease and its risk factors in type 2 diabetic patients. Iranian Journal of Diabetes and Obesity. 2011;3:83–87. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lahsaee S., Ghazizade A., Yazdanpanah M., Enhesari A., Malekzadeh R. Assessment of NAFLD cases and its correlation to BMI and metabolic syndrome in healthy blood donors in Kerman. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2012;5:183–189. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Razavizade M., Jamali R., Arj A., Talari H. Serum parameters predict the severity of ultrasonographic findings in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2012;11:513–520. doi: 10.1016/s1499-3872(12)60216-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bagheri Lankarani K., Ghaffarpasand F., Mahmoodi M., et al. Non alcoholic fatty liver disease in southern Iran: a population based study. Hepat Mon. 2013;13:e9248. doi: 10.5812/hepatmon.9248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eshraghian A., Dabbaghmanesh M.H., Eshraghian H., Fattahi M.R., Omrani G.R. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in a cluster of Iranian population: thyroid status and metabolic risk factors. Arch Iran Med. 2013;16:584–589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shiasi Arani K., Haghshenas M., Talari H.R., et al. Prevalence of fatty liver disease in obese children and adolescents who referred to pediatric clinic of kashan university of medical Sciences, Iran (2012-2013) J Babol Univ Med Sci. 2013;15:77–83. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amirkalali B., Poustchi H., Keyvani H., et al. Prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and its predictors in north of Iran. Iran J Public Health. 2014;43:1275–1283. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jafarian A., Ebrahimi A., Azmoudeh Ardalan F., et al. NAFLD prevalence in a young cadaveric organ donor population. Hepat Mon. 2014;14 doi: 10.5812/hepatmon.21574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Montazerifar F., Karajibani M., Ansari Moghaddam A. Relationship between fatty liver disease and biochemical factors in obese adolescents. Rawal Med J. 2014;39:15–18. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saki F., Karamizadeh Z. Metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance and Fatty liver in obese Iranian children. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16 doi: 10.5812/ircmj.6656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karimi-Sari H., Mousavi-Naeini S.M., Ramezani-Binabaj M., Najafizadeh-Sari S., Mir-Jalili M.H., Dolatimehr F. Prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in morbidly obese patients undergoing sleeve bariatric surgery in Iran and association with other comorbid conditions. Jundishapur Journal of Chronic Disease Care. 2015;4 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ostovaneh M.R., Zamani F., Ansari-Moghaddam A., et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver: the association with metabolic abnormalities, body mass index and central obesity--A population-based study. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2015;13:304–311. doi: 10.1089/met.2014.0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taghavi Ardakani A., Sharif M.R., Kheirkhah D. Fatty liver disease in obese children in Kashan, Iran. Caspian J of Pediatr. 2015;1:17–21. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adibi A., Maleki S., Adibi P., Etminani R., Hovsepian S. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and its related metabolic risk factors in isfahan, Iran. Adv Biomed Res. 2017;6:47. doi: 10.4103/2277-9175.204590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heidari Z., Gharebaghi A. Prevalence of non alcoholic fatty liver disease and its association with diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:OC04–OC7. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/25931.9823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rabiee B., Roozafzai F., Hemasi G.R., et al. The prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and diabetes mellitus in an Iranian population. Middle East J Dig Dis. 2017;9:86–93. doi: 10.15171/mejdd.2017.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Namakin K., Hosseini M., Zardast M., Mohammadifard M. Prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and its clinical characteristics in overweight and obese children in the south east of Iran. Hepat Mon. 2018;18 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hosseini Ahangar B., Rezaei B., Bahadori M., Ebrahimi A., Krasniqi R., Shahverdi E. Significant burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with advanced fibrosis in Iranian population: a cross-sectional analysis. Acta Med Iran. 2019;57:653–657. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Etminani R., Manaf Z.A., Shahar S., Azadbakht L., Adibi P. Predictors of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease among middle-aged Iranians. Int J Prev Med. 2020;11:113. doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_274_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amirkalali B., Khoonsari M., Sohrabi M.R., et al. Relationship between dietary macronutrient composition and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in lean and non-lean populations: a cross-sectional study. Publ Health Nutr. 2021;24:6178–6190. doi: 10.1017/S1368980021001762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pettinelli P., Fernández T., Aguirre C., Barrera F., Riquelme A., Fernández-Verdejo R. Prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and its association with lifestyle habits in adults in Chile: a cross-sectional study from the National Health Survey 2016-2017. Br J Nutr. 2023:1–30. doi: 10.1017/S0007114523000028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shalimar Elhence A., Bansal B., Gupta H., et al. Prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in India: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2022;12:818–829. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2021.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee J.Y., Kim K.M., Lee S.G., et al. Prevalence and risk factors of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in potential living liver donors in Korea: a review of 589 consecutive liver biopsies in a single center. J Hepatol. 2007;47:239–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Değertekin B., Tozun N., Demir F., et al. He changing prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in Turkey in the last decade. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2021;32:302–312. doi: 10.5152/tjg.2021.20062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Younossi Z.M., Koenig A.B., Abdelatif D., Fazel Y., Henry L., Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64:73–84. doi: 10.1002/hep.28431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zelber-Sagi S., Nitzan-Kaluski D., Halpern Z., Oren R. Prevalence of primary non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in a population-based study and its association with biochemical and anthropometric measures. Liver Int. 2006;26:856–863. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2006.01311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bedogni G., Miglioli L., Masutti F., Tiribelli C., Marchesini G., Bellentani S. Prevalence of and risk factors for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: the Dionysos nutrition and liver study. Hepatology. 2005;42:44–52. doi: 10.1002/hep.20734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ahmed M.H., Noor S.K., Bushara S.O., et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Africa and Middle East: an attempt to predict the present and future implications on the healthcare system. Gastroenterol Res. 2017;10:271–279. doi: 10.14740/gr913w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hernaez R., Lazo M., Bonekamp S., et al. Diagnostic accuracy and reliability of ultrasonography for the detection of fatty liver: a meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2011;54:1082–1090. doi: 10.1002/hep.24452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aeenparast A., Farzadi F., Maftoon F., Zahirian Moghadam T. Feasibility of estimating cost of diagnostic radiology and sonography services by using activity based costing. Payesh. 2015;14:15–23. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rahmani A., Sayehmiri K., Asadollahi K., Sarokhani D., Islami F., Sarokhani M. Investigation of the prevalence of obesity in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis study. Acta Med Iran. 2015;53:596–607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pasdar Y., Niazi P., Darbandi M., Khalvandi F., Izadi N. Effect of physical activity on body composition and quality of life among women staff of kermanshah university of medical Sciences in 2013. JRUMS. 2015;14:99–110. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Polyzos S.A., Kountouras J., Mantzoros C.S. Obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: from pathophysiology to therapeutics. Metabolism. 2019;92:82–97. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2018.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Polyzos S.A., Goulis D.G., Giouleme O., Germanidis G.S., Goulas A. Anti-obesity medications for the management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Curr Obes Rep. 2022;11:166–179. doi: 10.1007/s13679-022-00474-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sarwar R., Pierce N., Koppe S. Obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: current perspectives. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2018:533–542. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S146339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hashemian M., Merat S., Poustchi H., et al. Red meat consumption and risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in a population with low meat consumption: the golestan cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:1667–1675. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Peng H., Xie X., Pan X., et al. Association of meat consumption with NAFLD risk and liver-related biochemical indexes in older Chinese: a cross-sectional study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021;21:221. doi: 10.1186/s12876-021-01688-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zelber-Sagi S., Ivancovsky-Wajcman D., Fliss Isakov N., et al. High red and processed meat consumption is associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and insulin resistance. J Hepatol. 2018;68:1239–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim M.N., Lo C.H., Corey K.E., et al. Red meat consumption, obesity, and the risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease among women: evidence from mediation analysis. Clin Nutr. 2022;41:356–364. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2021.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Godfray H.C.J., Aveyard P., Garnett T., et al. Meat consumption, health, and the environment. Science. 2018;361 doi: 10.1126/science.aam5324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ekmekcioglu C., Wallner P., Kundi M., Weisz U., Haas W., Hutter H.P. Red meat, diseases, and healthy alternatives: a critical review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2018;58:247–261. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2016.1158148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Summart U., Thinkhamrop B., Chamadol N., Khuntikeo N., Songthamwat M., Kim C.S. Gender differences in the prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the Northeast of Thailand: a population-based cross-sectional study. F1000Res. 2017;6:1630. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.12417.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ayonrinde O.T., Olynyk J.K., Beilin L.J., et al. Gender-specific differences in adipose distribution and adipocytokines influence adolescent nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2011;53:800–809. doi: 10.1002/hep.24097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Venetsanaki V., Polyzos S.A. Menopause and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a review focusing on therapeutic perspectives. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2019;17:546–555. doi: 10.2174/1570161116666180711121949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ballestri S., Nascimbeni F., Baldelli E., Marrazzo A., Romagnoli D., Lonardo A. NAFLD as a sexual dimorphic disease: role of gender and reproductive status in the development and progression of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and inherent cardiovascular risk. Adv Ther. 2017;34:1291–1326. doi: 10.1007/s12325-017-0556-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Amiri Parsa T., Khademosharie M., Hamedinia M., Azarnive M. Evaluation of the factors associated with overweight and obesity in 30- to 50-year-old women of sabzevar. irje. 2014;9:75–83. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Golabi P., Paik J., Reddy R., Bugianesi E., Trimble G., Younossi Z.M. Prevalence and long-term outcomes of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease among elderly individuals from the United States. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019;19:56. doi: 10.1186/s12876-019-0972-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Park S.H., Jeon W.K., Kim S.H., et al. Prevalence and risk factors of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease among Korean adults. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21(1 Pt 1):138–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.04086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Amarapurkar D., Kamani P., Patel N., et al. Prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: population based study. Ann Hepatol. 2007;6:161–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Koehler E.M., Schouten J.N., Hansen B.E., et al. Prevalence and risk factors of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in the elderly: results from the Rotterdam study. J Hepatol. 2012;57:1305–1311. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bertolotti M., Lonardo A., Mussi C., et al. Onalcoholic fatty liver disease and aging: epidemiology to management. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:14185–14204. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i39.14185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hazlehurst J.M., Woods C., Marjot T., Cobbold J.F., Tomlinson J.W. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and diabetes. Metabolism. 2016;65:1096–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Haghdoost A.A., Rezazadeh-Kermani M., Sadghirad B., Baradaran H.R. Prevalence of type 2 diabetes in the Islamic Republic of Iran: systematic review and meta-analysis. East Mediterr Health J. 2009;15:591–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Moslemi M., Kheirandish M., Mazaheri R.N.F., et al. National food policies in the Islamic Republic of Iran aimed at control and prevention of noncommunicable diseases. East Mediterr Health J. 2020;26:1556–1564. doi: 10.26719/emhj.20.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.