Abstract

The bone marrow contains peripheral nerves that promote haematopoietic regeneration after irradiation or chemotherapy (myeloablation), but little is known about how this is regulated. Here we found that nerve growth factor (NGF) produced by leptin receptor-expressing (LepR+) stromal cells is required to maintain nerve fibres in adult bone marrow. In nerveless bone marrow, steady-state haematopoiesis was normal but haematopoietic and vascular regeneration were impaired after myeloablation. LepR+ cells, and the adipocytes they gave rise to, increased NGF production after myeloablation, promoting nerve sprouting in the bone marrow and haematopoietic and vascular regeneration. Nerves promoted regeneration by activating β2 and β3 adrenergic receptor signalling in LepR+ cells, and potentially in adipocytes, increasing their production of multiple haematopoietic and vascular regeneration growth factors. Peripheral nerves and LepR+ cells thus promote bone marrow regeneration through a reciprocal relationship in which LepR+ cells sustain nerves by synthesizing NGF and nerves increase regeneration by promoting the production of growth factors by LepR+ cells.

Subject terms: Haematopoietic stem cells, Stem-cell niche

Gao et al. report that leptin receptor+ stromal cells sustain nerves in the bone marrow by producing nerve growth factor. After myeloablation, nerves promote marrow regeneration by increasing the production of multiple growth factors by leptin receptor+ cells.

Main

Peripheral nerves promote the regeneration of diverse tissues, but in most cases little is known about the mechanisms by which they promote regeneration1–5. The bone marrow contains peripheral nerves, including sympathetic6, parasympathetic7 and sensory8,9 nerve fibres. Lumbar sympathetic nerve transection depletes sympathetic nerve fibres and Schwann cells in the bone marrow, leading to haematopoietic stem cell (HSC) depletion5. Sympathetic denervation with systemic 6-hydroxydopamine does not affect HSC frequency or function under steady-state conditions4, but systemic ablation of both sympathetic and sensory nerves depletes bone marrow HSCs8. Nerve fibres regulate the circadian mobilization of haematopoietic stem/progenitor cells into the blood6,8,10,11 and the regeneration of haematopoiesis after myeloablation by irradiation or chemotherapy4,7,12,13. Nerve fibres promote haematopoietic regeneration and changes in haematopoiesis during ageing by activating β adrenergic receptors4,14,15, though the mechanism by which β adrenergic receptors promote haematopoietic regeneration, and the cells in which they act, are unknown.

Leptin receptor-expressing (LepR+) stromal cells in adult mouse bone marrow synthesize growth factors that promote the maintenance of haematopoietic stem and progenitor cells16–21 as well as osteogenesis22,23 and vascular regeneration24,25. LepR+ cells promote the maintenance of HSCs and early restricted progenitors by synthesizing stem cell factor (SCF)16,18,21, CXCL12 (refs. 17,26), IL7 (ref. 19), pleiotrophin20 and Csf1 (refs. 27,28). Analysis of SCF16 and CXCL12 (refs. 17,26) reporter genes, as well as single-cell RNA sequencing29–32, has shown that LepR+ cells are the major source of these factors in adult bone marrow. LepR+ cells also promote vascular regeneration by producing Angiopoietin-1 (ref. 25) and VEGF-C24.

LepR+ cells also include skeletal stem and progenitor cells that form the adipocytes and osteoblasts that arise in adult bone marrow33–35. The osteoblasts formed by LepR+ cells contribute to the maintenance and repair of the adult skeleton33,34,36 and secrete factors that promote osteogenesis22,23. The adipocytes that arise from LepR+ cells in adult bone marrow promote the regeneration of HSCs and haematopoiesis after myeloablation by synthesizing SCF35. LepR+ cells and adipocytes also promote HSC maintenance and quiescence by secreting adiponectin, which suppresses inflammation37. In this article, bone marrow nerve fibers were found to be maintained by NGF synthesized by LepR+ cells and, in turn, nerves promote haematopoietic and vascular regeneration by secreting adrenergic neurotransmitters that activate β2/β3 adrenergic receptor signaling in LepR+ cells.

Results

Nerve growth factor is mainly synthesized by LepR+ cells

Peripheral nerves require neurotrophic factors for their maintenance38, but the source of such factors in the bone marrow is unknown. Analysis of published microarray data16 (National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) accession number GSE33158) suggested that nerve growth factor (Ngf) was the only neurotrophic factor detected in adult bone marrow (Fig. 1a). Ngf expression was detected in Scf–GFP+CD45−Ter119−CD31− stromal cells, nearly all of which are LepR+(ref. 33), but little or no Ngf was detected in osteoblasts, endothelial cells or unfractionated whole bone marrow (WBM) cells (Fig. 1a). Similar results were obtained by RNA sequencing22 (NCBI accession number PRJNA914703), which detected Ngf in PDGFRα+CD45−Ter119−CD31− stromal cells, nearly all of which are LepR+(ref. 33), but not in endothelial cells or WBM cells (Fig. 1b).

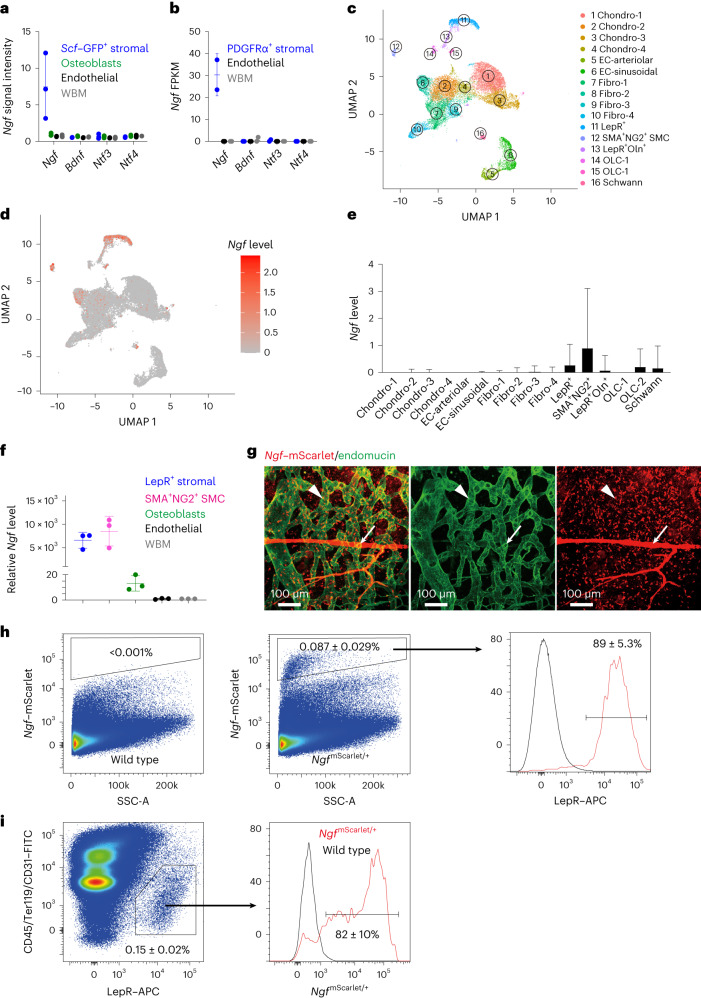

Fig. 1. Ngf is mainly expressed in the bone marrow by LepR+ stromal cells.

a,b, The expression of neurotrophic factors by microarray analysis16 (a) and RNA sequencing22 (b) in bone marrow stromal cells (isolated on the basis of expression of Scf–GFP (a) or PDGFRα (b) staining, both of which are nearly completely overlapping with LepR expression33), VE-cadherin+ bone marrow endothelial cells, Col2.3–GFP+CD45−Ter119−CD31− osteoblasts, and WBM cells (three mice in a and two mice in b, from three or two independent experiments, respectively). c, Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) plot showing clustering of single-cell RNA sequencing analysis of 4,209 non-haematopoietic cells from enzymatically dissociated bones/bone marrow in 8-week-old mice39. d, Ngf is mainly expressed by Lepr+ stromal cells (cell cluster 11 in c) and smooth muscle cells (cell cluster 12). e, Ngf expression by all cell clusters shown in c (cells were obtained from four mice and analysed in three independent experiments). f, Ngf expression by qRT–PCR in LepR+CD45−Ter119−CD31− stromal cells, NG2–DsRed+ smooth muscle cells, Col1a1–GFP+ osteoblasts, VE-cadherin+ endothelial cells and unfractionated cells from the bone marrow of 2-month-old mice (three mice from three independent experiments). g, Deep imaging of femur bone marrow from adult NgfmScarlet/+ mouse: the Ngf–mScarlet+ cells were found around endomucinhigh sinusoids (arrowhead) as well as around endomucinlow arterioles (arrow; the images are representative of five mice). h,i, Flow cytometric analysis of enzymatically dissociated bone marrow from NgfmScarlet/+ mice: 89% of Ngf–mScarlet+ cells were LepR+, and most LepR+ cells were Ngf–mScarlet+ (four mice from four independent experiments). SSC-A, side scatter area. All data represent mean ± standard deviation.

Single-cell RNA sequencing of enzymatically dissociated cells from the femurs and tibias of 8-week-old mice showed that most Ngf-expressing cells in adult bone marrow were LepR+ cells (Fig. 1c,d; NCBI accession number PRJNA835050)39. Ngf was also expressed by a much smaller number of SMA+NG2+ smooth muscle cells, and by rare osteoblasts (OLC-2 cells), Schwann cells and fibroblasts (Fig. 1c–e). Little or no Ngf was detected in endothelial cells, chondrocytes or other stromal cells (Fig. 1c–e). Quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) confirmed that Ngf was highly expressed by LepR+CD45−Ter119−CD31− stromal cells and SMA+NG2+ smooth muscle cells, with approximately 100-fold lower expression by Col2.3–GFP+CD45−Ter119−CD31− osteoblasts and no expression by endothelial cells or WBM cells (Fig. 1f). LepR+ cells and smooth muscle cells were thus the main sources of NGF in the bone marrow.

To identify the location of Ngf-expressing cells in adult bone marrow, we generated an Ngf–mScarlet (NgfmScarlet) knock-in reporter allele (Extended Data Fig. 1a–c). Confocal imaging40 of cleared femurs from adult NgfmScarlet/+ mice showed that Ngf–mScarlet was expressed by stromal cells surrounding Endomucinlow arterioles as well as Endomucinhigh sinusoids (Fig. 1g). While the peri-arteriolar staining appeared more prominent, the abundance of sinusoids throughout the bone marrow meant that most of the Ngf–mScarlet staining was peri-sinusoidal. The peri-arteriolar staining probably reflected Ngf–mScarlet expression by both peri-arteriolar LepR+Osteolectin+ cells36 as well as SMA+NG2+ smooth muscle cells (Fig. 1e).

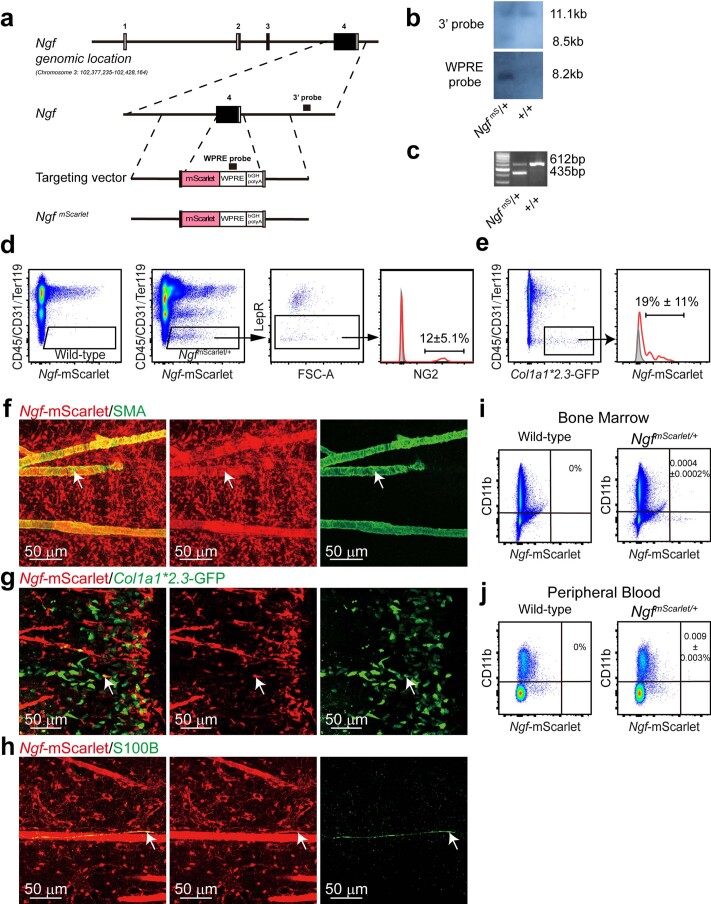

Extended Data Fig. 1. Generation and characterization of the NgfmScarlet mouse reporter allele.

(a-c) The mouse Ngf gene was modified by inserting an mScarlet-WPRE-pA cassette after an alternative ATG start codon in exon 4, replacing most of the coding sequence in exon 4. Open boxes indicate untranslated regions and black boxes indicate translated regions of Ngf. The correctly targeted founder mouse (F0) was identified by southern blotting (b) using 3’ and WPRE probes (black bars in a) (representative of three independent experiments). (c) PCR genotyping of genomic DNA confirmed germline transmission of the Ngf mScarlet allele. Mice were backcrossed at least three times onto a C57BL/Ka background before analysis (representative of three independent experiments). (d) Flow cytometric analysis showed that 12% of Ngf-mScarlet+ bone marrow stromal cells were NG2+ smooth muscle cells in enzymatically dissociated bone marrow cells. (e) When bones were crushed and enzymatically dissociated, 19% of osteoblasts were Ngf-mScarlet+ (4 mice from 4 independent experiments). (f-h). Deep imaging of femur bone marrow from 2-8 month-old Ngf mScarlet/+ mice. The Ngf-mScarlet+ cells included SMA+ periarteriolar smooth muscle cells (arrow, f), a subset of Col1a1-GFP+ osteoblasts associated with trabecular bone in the metaphysis (arrow, g), and S100+ Schwann cells associated with nerve fibers in the bone marrow (arrow, h) (each panel reflects data from three mice from three independent experiments). As in Fig. 1, most of the Ngf-mScarlet+ cells in these images were LepR+ perisinusoidal stromal cells. (i, j) Flow cytometric analysis showed that only rare macrophages in the bone marrow (i) or blood (j) were Ngf-mScarlet+ (3 mice from 3 independent experiments).

Flow cytometric analysis of enzymatically dissociated bone marrow cells showed that 0.087 ± 0.029% of bone marrow cells were Ngf–mScarlet+ (Fig. 1h). Consistent with the single-cell RNA sequencing (Fig. 1d), 89 ± 5.3% of bone marrow Ngf–mScarlet+ cells were LepR+ (Fig. 1h) and 82 ± 10% of all bone marrow LepR+ cells were Ngf–mScarlet+ (Fig. 1i). The remaining ~10% of Ngf–mScarlet+ cells that were negative for LepR within the bone marrow were mainly SMA+NG2+ smooth muscle cells (Extended Data Fig. 1d,f). There were also rare osteoblasts (Extended Data Fig. 1e,g), Schwann cells (Extended Data Fig. 1h) and macrophages (Extended Data Fig. 1i,j) that were Ngf–mScarlet+. The flow cytometry gates used to sort each cell population characterized in this study are shown in Extended Data Fig. 2.

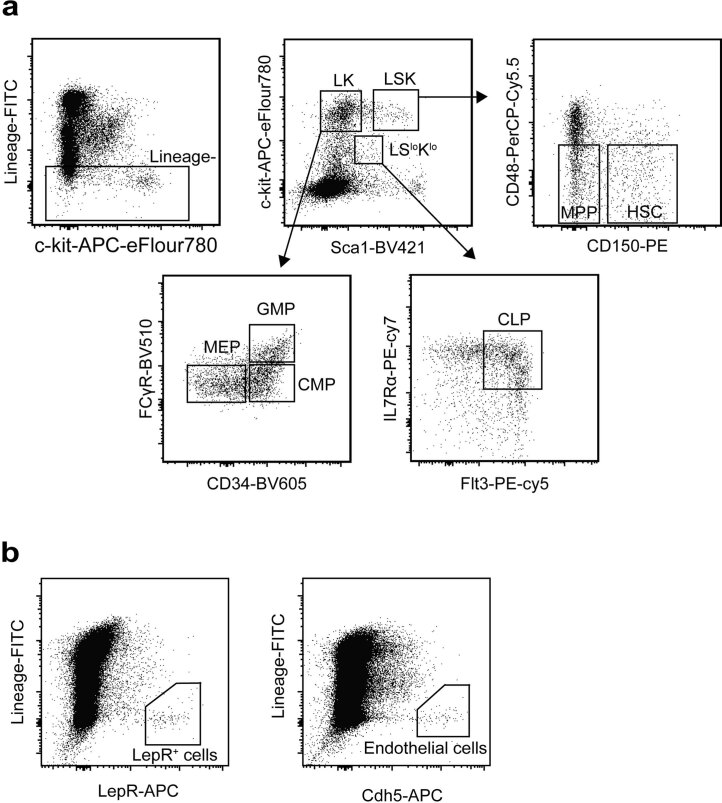

Extended Data Fig. 2. Flow cytometry gating strategy for the isolation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell populations, LepR+ cells and endothelial cells.

(a) Representative flow cytometry gates used to isolate hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell populations from bone marrow. (b) Representative flow cytometry gates used to isolate LepR+ cells and endothelial cells from bone marrow.

NGF from LepR+ cells is required for bone marrow innervation

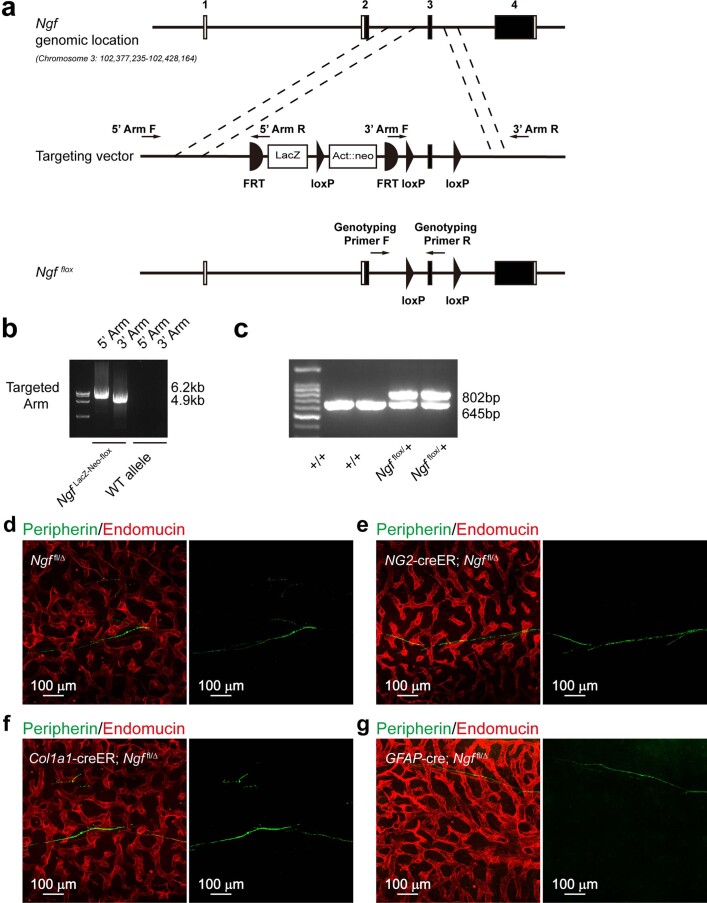

To test if NGF is required for bone marrow innervation we generated mice with a floxed Ngf allele (Extended Data Fig. 3a–c). We conditionally deleted Ngf in LepR+ cells using Leprcre, in smooth muscle cells using NG2–creER, in osteoblasts using Col1a1–creER, and in Schwann cells using GFAP–cre. Deletion from smooth muscle cells, osteoblasts or Schwann cells had no significant effect on bone marrow NGF levels (Fig. 2a) or the number of nerve fibres in adult bone marrow (Fig. 2b and Extended Data Fig. 3d–g). Therefore, smooth muscle cells, osteoblasts and Schwann cells were not significant sources of NGF for nerve maintenance in bone marrow.

Extended Data Fig. 3. Generation of the Ngfflox mouse allele.

(a) LoxP elements were inserted on either side of exon 3 of Ngf such that Cre-mediated recombination eliminates exon 3 and introduces a frameshift. Open boxes indicate untranslated exon sequences and black boxes indicate translated sequences. The insertion sites were selected to avoid disrupting conserved intron sequences. The Ngf LacZ-Neo-flox targeting vector was obtained from the European Conditional Mouse Mutagenesis Program (EUCOMM), linearized, and electroporated into C57BL-derived Bruce4 ES cells. Chimeric mice were generated by injecting ES clones into blastomeres and were bred with C57BL/Ka mice to obtain germline transmission of the Ngf LacZ-Neo-flox allele. (b) Ngf LacZ-Neo-flox mice were bred with Flpe mice55 to remove the LacZ-Neo cassette. Successful removal of the LacZ-Neo cassette was confirmed by PCR primers spanning the FRT sites, as shown by arrows on the targeting vector in panel a. (c) PCR genotyping of genomic DNA confirmed germline transmission of the Ngf flox allele using the genotyping primers shown in panel a. Mice were backcrossed at least five times onto a C57BL/Ka background before analysis (images in panels b and c are representative of three independent experiments). (d-g) Deep imaging of peripherin+ nerve fibers in the bone marrow of 6-8 month-old Ngf fl/∆ control (d), NG2-CreER; Ngf fl/∆ (e), Col1a1-CreER; Ngf fl/∆ (f), and GFAP-Cre; Ngf fl/∆ (g) mice. Images are representative of a total of 4 mice per genotype from 4 experiments.

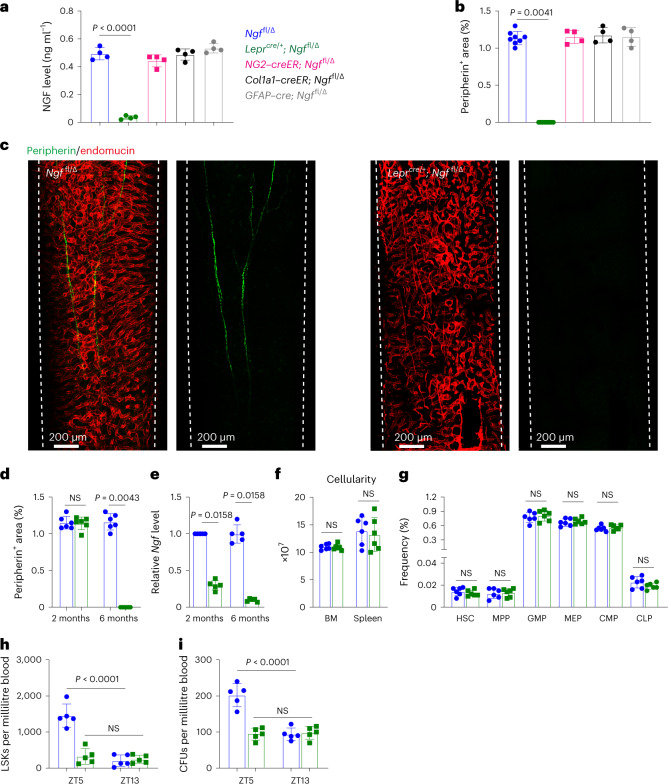

Fig. 2. NGF from LepR+ cells is necessary to maintain nerve fibres in the bone marrow.

a,b, NGF protein levels in bone marrow serum (a) and the area occupied by peripheral nerves in bone marrow (b) from 6–8-month-old Ngffl/∆ control (n = 8), Leprcre/+; Ngffl/∆ (n = 8), NG2–creER; Ngffl/∆ (n = 4), Col1a1–creER; Ngffl/∆ (n = 4), and GFAP–cre; Ngffl/∆ mice (n = 4) (four to eight mice per genotype from four independent experiments). c, Deep imaging of femur bone marrow from 6–8-month-old Leprcre/+; Ngffl/∆ and Ngffl/∆ littermate control mice (images are representative of three experiments with one mouse per genotype per experiment). d,e, Peripheral nerves were present in normal numbers in the bone marrow of 2-month-old Leprcre/+; Ngffl/∆ mice but were absent from the bone marrow of 6-month-old Leprcre/+; Ngffl/∆ mice (n = 6) (d) when the efficiency of Ngf deletion was more than 90% (n = 5) (e) (five to six mice per genotype per age from five to six independent experiments). f,g, Bone marrow and spleen cellularity (f) and haematopoietic stem and progenitor cell frequencies in the bone marrow (g) of 6–8-month-old Leprcre/+; Ngffl/∆ and Ngffl/∆ littermate control mice (six mice per genotype from six independent experiments). h,i, Defective circadian regulation of haematopoietic stem/progenitor cell mobilization into the blood of Leprcre/+; Ngffl/∆ mice based on numbers of LSK cells (h) and colony-forming progenitors (i) per millilitre of blood at different Zeitgeber times (ZT5, late morning; ZT13, just after nightfall; five mice per genotype from five independent experiments). All data represent mean ± standard deviation. The statistical significance of differences among treatments was assessed using a one-way ANOVA (a) followed by the Dunnett’s multiple comparisons adjustment, a Kruskal–Wallis test (b) followed by the Dunn’s multiple comparisons adjustment, Mann–Whitney tests (d and e) or Student’s t-tests (f and g) followed by the Holm–Šidák’s multiple comparisons adjustment, or matched samples two-way ANOVAs (h and i) followed by the Šidák’s multiple comparisons adjustment. All the statistical tests were two-sided. Not significant (NS): P > 0.05.

Adult Leprcre/+; Ngffl/∆ mice were born in expected numbers and did not differ from littermate controls in terms of gross appearance (Extended Data Fig. 4a), body length (Extended Data Fig. 4b) or body mass (Extended Data Fig. 4c). LepR+ cells from Leprcre/+; Ngffl/∆ mice had Ngf transcript levels that were approximately 30% of control levels at 2 months of age and less than 10% of control levels at 6 months of age (Fig. 2e). Deletion of Ngf from LepR+ cells profoundly depleted NGF from the bone marrow by 6 months of age (Fig. 2a).

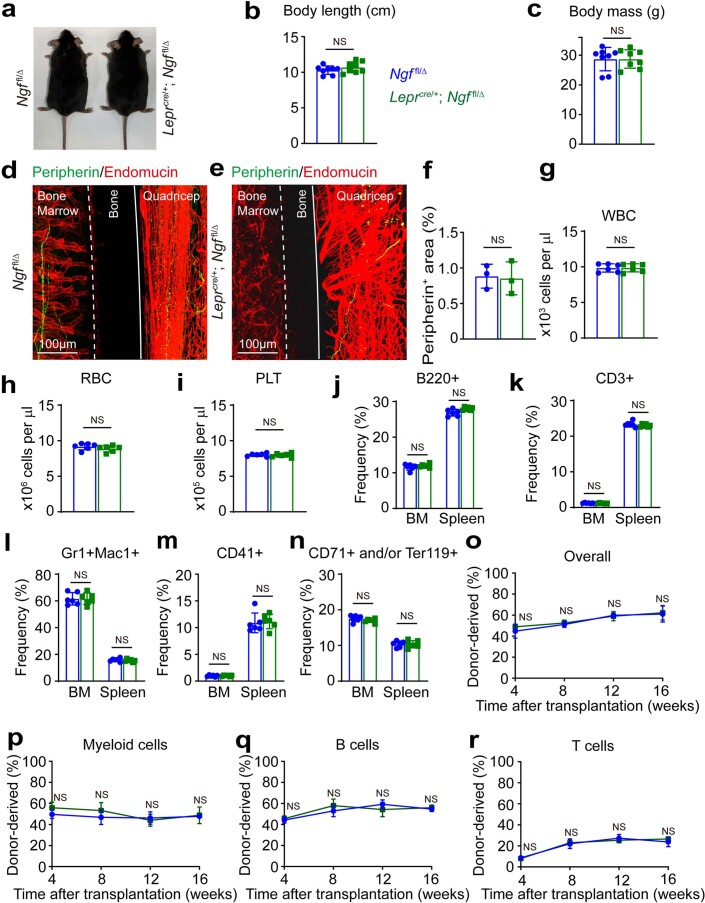

Extended Data Fig. 4. Leprcre/+; Ngffl/∆ mice developed normally, had normal numbers of peripheral nerves outside of bones, and bone marrow innervation was dispensable for hematopoiesis in adult bone marrow.

(a-c) Six month-old Leprcre/+; Ngf fl/∆ mice were grossly normal in size and appearance as compared to Ngf fl/∆ littermate controls (a), with similar body length (b) and body mass (c) (a total of 8 mice per genotype from 8 independent experiments). (d-f) Immunofluorescence analysis of nerve fibers in longitudinal femur sections from 6 month-old Leprcre/+; Ngf fl/∆ (d) and Ngf fl/∆ littermate control mice (e), showing the presence of nerve fibers outside bone marrow in both Leprcre/+; Ngf fl/∆ and control mice but nerve fibers were only present inside the bone marrow of control mice (d). (f) Nerves in the quadriceps of 6-8 month-old Leprcre/+; Ngf fl/∆ and littermate control mice appeared to be comparable in numbers (3 mice per genotype from 3 independent experiments). (g-i) Blood cell counts in 6 month-old Leprcre/+; Ngf fl/∆ mice and littermate controls. (j-n) 6 month-old Leprcre/+; Ngf fl/∆ and littermate controls exhibited no significant differences in the frequencies of B220+ B cells (j), CD3+ T cells (k), Gr-1+Mac-1+ myeloid cells (l), CD41+ megakaryocyte lineage cells (m), or CD71+/Ter119+ erythroid lineage cells (n) in the bone marrow and spleen (panels g-n reflect a total of 6 mice per genotype in 6 independent experiments). (o-r) Bone marrow cells from 6-8 month-old Leprcre/+; Ngf fl/∆ and littermate control mice gave similar levels of donor cell reconstitution upon competitive transplantation into irradiated mice (bone marrow cells from 5 donor mice per genotype were transplanted into a total of 5 recipients per donor in 5 independent experiments). All data represent mean ± standard deviation. Statistical significance was assessed using Student’s t-tests (b, c, and f), t-tests followed by the Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparisons adjustment (g-n), or matched samples two-way ANOVAs followed by the Sidak’s multiple comparisons adjustment (o-r). All statistical tests were two-sided. Not significant (NS): P > 0.05.

No bone marrow innervation defect was apparent in Leprcre/+; Ngffl/∆ mice during development as the number of nerve fibres in the bone marrow was normal in 2-month-old Leprcre/+; Ngffl/∆ mice (Fig. 2d). However, by 6 months of age, when recombination in LepR+ cells was nearly complete, we observed virtually no nerve fibres in the bone marrow of Leprcre/+; Ngffl/∆ mice (Fig. 2b–d). Peripheral nerves appeared to be present in normal numbers in the quadriceps of 6-month-old Leprcre/+; Ngffl/∆ mice (Extended Data Fig. 4d–f). Nerve fibres thus grew into the bone marrow normally during development in Leprcre/+; Ngffl/∆ mice but became depleted within the bone marrow, but not outside of the bone marrow, by 6 months of age, when NGF was depleted to less than 10% of control levels in the bone marrow.

Consistent with prior studies4,6,11, loss of nerve fibres from the bone marrow did not have any gross effect on steady-state haematopoiesis. Six-month-old Leprcre/+; Ngffl/∆ mice did not differ from littermate controls in terms of bone marrow or spleen cellularity (Fig. 2f), or the frequencies of HSCs, multipotent haematopoietic progenitors (MPPs), granulocyte–macrophage progenitors (GMPs), megakaryocyte–erythroid progenitors (MEPs), common myeloid progenitors (CMPs) or common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs) in the bone marrow (Fig. 2g). There were also no differences in blood cell counts (Extended Data Fig. 4g–i) or in the frequencies of B220+ B cells, CD3+ T cells, Gr1+Mac1+ myeloid cells, CD41+ megakaryocyte lineage cells or CD71+/Ter119+ erythroid lineage cells in the bone marrow or spleen (Extended Data Fig. 4j–n). Finally, WBM cells from 6-month-old Leprcre/+; Ngffl/∆ mice and littermate controls did not differ in their capacity to reconstitute myeloid, B or T cells upon competitive transplantation into irradiated mice (Extended Data Fig. 4o–r). Bone marrow nerve fibres thus appear to be dispensable for normal adult haematopoiesis.

In agreement with earlier studies6,11, we did observe a defect in the circadian mobilization of Lineage−Sca1+c-kit+ (LSK) haematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (Fig. 2h) and colony-forming progenitors (Fig. 2i) into the blood during midmorning (Zeitgeber Time 5) in 6-month-old Leprcre/+; Ngffl/∆ as compared with littermate control mice.

Bone marrow innervation promotes haematopoietic regeneration

To test for haematopoietic regeneration defects, we lethally irradiated (1,080 rads) and transplanted a radioprotective dose of 1,000,000 WBM cells into 6-month-old LeprCre/+; Ngffl/∆ mice and littermate controls. While all control mice survived, 41% (9 of 22) of LeprCre/+; Ngffl/∆ mice died between 10 and 18 days after irradiation, consistent with haematopoietic failure (Fig. 3a). The LeprCre/+; Ngffl/∆ mice exhibited significantly lower white blood cell (WBC, Fig. 3b), red blood cell (RBC, Fig. 3c) and platelet (PLT) counts (Fig. 3d) as well as bone marrow cellularity (Fig. 3e) and LSK cell numbers (Fig. 3f) at 14 and 28 days after irradiation. At 28 days after irradiation, HSC numbers were much lower in the bone marrow of LeprCre/+; Ngffl/∆ as compared with littermate control mice (Fig. 3g). We thus observed broad reductions in blood and bone marrow cell counts as well as the numbers of haematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in LeprCre/+; Ngffl/∆ mice at 14–28 days after irradiation.

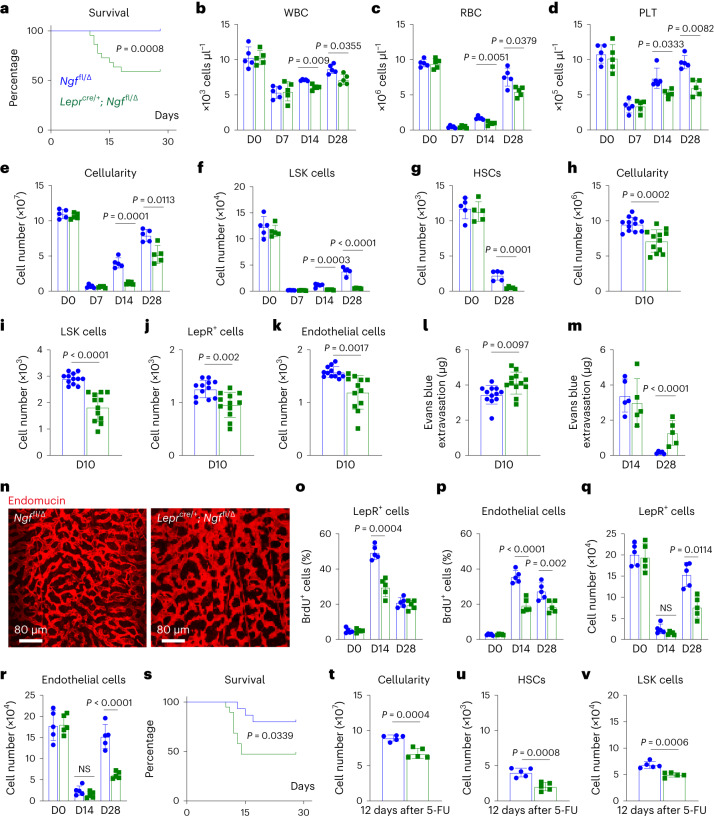

Fig. 3. Leprcre/+; Ngffl/∆ mice exhibit defects in haematopoietic and vascular regeneration after irradiation.

a, Survival of Leprcre/+; Ngffl/∆ and Ngffl/∆ littermate control mice after irradiation and transplantation of wild-type bone marrow cells (22 mice per genotype from 3 independent experiments). b–d, WBC (b), RBC (c) and PLT (d) counts from Leprcre/+; Ngffl/∆ and littermate control mice before (D0) and 7, 14 and 28 days after irradiation. e,f, Bone marrow cellularity (e) and LSK cell numbers (f) from 6-month-old Leprcre/+; Ngffl/∆ and littermate control mice on day (D)0, D7, D14 and D28 after irradiation. g, Numbers of HSCs in bone marrow (always one tibia and one femur) from Leprcre/+; Ngffl/∆ and littermate control mice before and 28 days after irradiation. h–k, Cellularity (h) and numbers of LSK cells, (i) LepR+ cells (j) and endothelial cells (k) in the bone marrow of Leprcre/+; Ngffl/∆ and littermate control mice on D10 after irradiation (a total of 12 mice per genotype from 3 independent experiments). l,m, Leakage of intravenously injected Evans blue dye into femur bone marrow at D10 (l), D14 and D28 (m) after irradiation of Leprcre/+; Ngffl/∆ and littermate control mice. n, Endomucin staining of the vasculature in the bone marrow of Leprcre/+; Ngffl/∆ and littermate control mice 28 days after irradiation (representative of three experiments). o,p, The percentages of LepR+ cells (o) and endothelial cells (p) from Leprcre/+; Ngffl/∆ and littermate control mice that incorporated a 48-h pulse of bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) 28 days after irradiation. q,r, Numbers of LepR+ cells (q) and endothelial cells (r) in the bone marrow 28 days after irradiation. s, Survival of 6-month-old Leprcre/+; Ngffl/∆ and Ngffl/∆ littermate control mice after 5-FU treatment (19 Leprcre/+; Ngffl/∆ mice and 15 Ngffl/∆ mice in 3 independent experiments). t–v, Cellularity (t), numbers of HSCs (u) and LSK cells (v) in bone marrow from 6-month-old Leprcre/+; Ngffl/∆ and littermate control mice 12 days after 5-FU treatment. Unless otherwise specified, each panel shows five mice per genotype from five independent experiments per timepoint. All data represent mean ± standard deviation. Statistical significance was assessed using log-rank tests (a and s), two-way ANOVAs (m and p) or matched samples two-way ANOVAs (b and d) followed by the Šidák’s multiple comparisons adjustment, Student’s t-tests (h, l and t) or Student’s t-tests (c, e–g, o, q, r, u and v) or Welch’s t-tests (i–k) followed by the Holm–Šidák’s multiple comparisons adjustment. All statistical tests were two-sided. Not significant (NS) means P > 0.05.

We also assessed vascular and stromal cell regeneration in LeprCre/+; Ngffl/∆ and littermate control mice. At 10 days after lethal irradiation and transplantation, we observed significantly reduced numbers of bone marrow cells (Fig. 3h), LSK cells (Fig. 3i), LepR+ stromal cells (Fig. 3j) and endothelial cells (Fig. 3k), as well as increased vascular leakage (Fig. 3l) in the bone marrow of LeprCre/+; Ngffl/∆ mice as compared with littermate controls. At 28 days after irradiation, blood vessels were patent in control mice but remained leaky (Fig. 3m) and morphologically abnormal (Fig. 3n) in LeprCre/+; Ngffl/∆ mice. LeprCre/+; Ngffl/∆ mice had significantly less proliferation by LepR+ cells at 14 days after irradiation (Fig. 3o) and by endothelial cells at 14 and 28 days after irradiation (Fig. 3p). In this experiment we observed trends towards reduced numbers of LepR+ cells and endothelial cells at 14 days after irradiation and significant reductions in the numbers of these stromal cells at 28 days after irradiation (Fig. 3q,r). The loss of nerve fibres from the bone marrow in LeprCre/+; Ngffl/∆ mice was thus associated with broad defects in the regeneration of haematopoietic, stromal and vascular cells at 10–28 days after irradiation.

To test if defects in haematopoietic regeneration were also evident after sublethal irradiation, we administered 650 rads to 6-month-old LeprCre/+; Ngffl/∆ and littermate control mice. The LeprCre/+; Ngffl/∆ mice exhibited significantly reduced survival from 12 to 15 days after irradiation (Extended Data Fig. 5a) as well as reduced bone marrow cellularity (Extended Data Fig. 5b), HSC numbers (Extended Data Fig. 5c) and LSK cell numbers (Extended Data Fig. 5d) as compared with littermate controls at 28 days after irradiation.

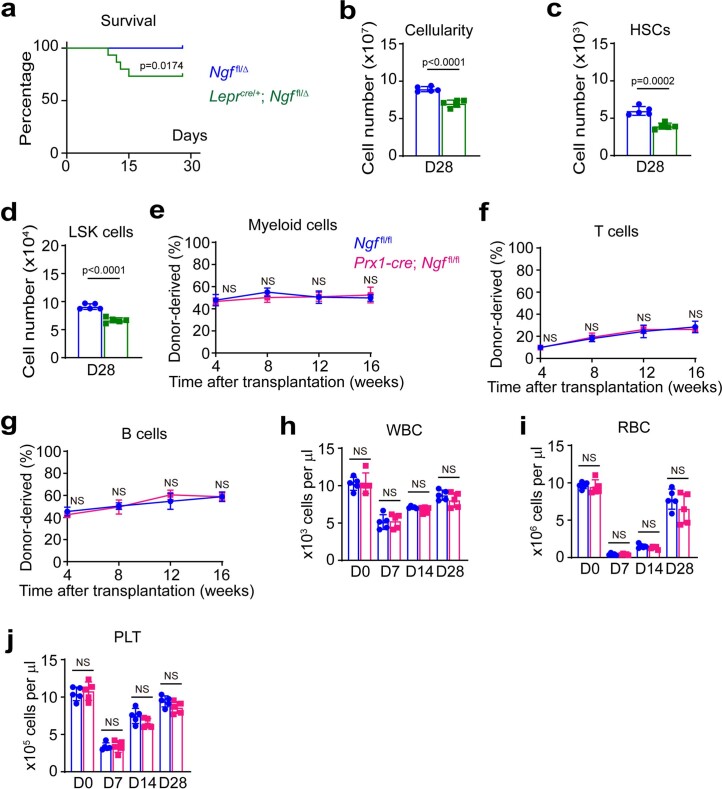

Extended Data Fig. 5. Nerve fibers promote hematopoietic and vascular regeneration after lethal and sublethal irradiation but are not required under steady-state conditions.

(a) Survival of 6-8 month-old Leprcre/+; Ngf fl/∆ and Ngf fl/∆ littermate control mice after sublethal irradiation. (b-d) Cellularity (b), numbers of HSCs (c) and LSK cells (d) in bone marrow (one tibia and one femur) from of 6 month-old Leprcre/+; Ngf fl/∆ and Ngf fl/∆ littermate control mice at 28 days after sublethal irradiation (5 mice per genotype from 5 independent experiments per time point). (e-g) Bone marrow cells from femurs of non-irradiated 2 month-old Prx1-cre; Ngf fl/fl mice and Ngf fl/fl littermate controls gave similar levels of myeloid, T cell and B cell reconstitution upon competitive transplantation into irradiated recipients (bone marrow cells from 5 donor mice were transplanted into a total of 5 recipients per donor in 5 independent experiments). (h-j) White blood cell (h), red blood cell (i), and platelet (j) counts from 2 month-old Prx1-cre; Ngf fl/fl and Ngf fl/fl littermate control mice before (D0) and 7, 14, and 28 days after irradiation and transplantation (5 mice per genotype from 5 independent experiments per time point). All data represent mean ± standard deviation. The statistical significance of differences among treatments was assessed using long-rank test (a), Student’s t-test (b), t-tests followed by the Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparisons adjustment (c, d, and h-j), or matched samples two-way ANOVAs followed by the Sidak’s multiple comparisons adjustment (e-g). All statistical tests were two-sided. Not significant (NS): P > 0.05.

To test if defects in haematopoietic, vascular and stromal cell regeneration were evident after chemotherapy, we treated LeprCre/+; Ngffl/∆ and littermate control mice with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU). The LeprCre/+; Ngffl/∆ mice exhibited significantly reduced survival from 12 to 15 days after irradiation (Fig. 3s) as well as reduced numbers of bone marrow cells (Fig. 3t), HSCs (Fig. 3u) and LSK cells (Fig. 3v) as compared with littermate controls at 12 days after 5-FU treatment. Impaired haematopoietic regeneration was thus observed in LeprCre/+; Ngffl/∆ mice irrespective of whether myeloablation was induced by 5-FU treatment, sublethal irradiation or lethal radiation.

NGF acts locally to promote nerve maintenance in bone marrow

Neurotrophic factors act locally to promote the survival of innervating neurons41,42. To test if NGF acts locally within the bone marrow to promote nerve fibre maintenance, we deleted Ngf using Prx1–cre. Prx1–cre recombines in limb mesenchymal cells, including in LepR+ cells that form in the bone marrow of limb bones, but not within the axial skeleton33,39,43. Two-month-old Prx1–cre; Ngffl/fl mice exhibited a lack of nerve fibres in femur bone marrow but normal innervation of vertebral bone marrow (Fig. 4a–c). This demonstrates that NGF acts locally within the bone marrow to promote nerve fibre maintenance.

Fig. 4. Prx1–cre; Ngffl/fl mice exhibit a loss of nerve fibres as well as defects in haematopoietic and vascular regeneration in long bones but not in vertebrae.

a,b, Nerve fibres (green) were visible in femur (a) and vertebra (b) bone marrow from Ngffl/fl control mice and in vertebra bone marrow (b) from 2-month-old Prx1–cre; Ngffl/fl mice but not in femur bone marrow (a) from Prx1–cre; Ngffl/fl mice (representative of three independent experiments). c, The area occupied by peripherin+ nerve fibres in bone marrow sections from 2-month-old Prx1–cre; Ngffl/fl and littermate control mice. d–f, Under steady-state conditions, 2-month-old Prx1–cre; Ngffl/fl mice did not significantly differ from littermate control mice in terms of spleen, femur bone marrow or vertebral bone marrow cellularity (d), the frequencies of haematopoietic stem and progenitor cell populations in femur bone marrow (e) (six mice per genotype from six independent experiments in c–e), or the levels of donor cell reconstitution upon competitive transplantation into irradiated mice (f, femur bone marrow cells from five donor mice were transplanted into a total of five recipients per donor per genotype in five independent experiments). g–k, At 28 days after irradiation, Prx1–cre; Ngffl/fl and littermate control mice did not significantly differ in terms of bone marrow cellularity (g) and the numbers of HSCs (h), LSK cells (i), LepR+ cells (j) or endothelial cells (k) in the vertebrae, but all of these parameters were significantly lower in femur bone marrow (six mice from six independent experiments). l, Leakage of intravenously injected Evans blue dye into femur and vertebra bone marrow 28 days after irradiation (five mice from five independent experiments). All data represent mean ± standard deviation. The statistical significance of differences among treatments was assessed using Mann–Whitney tests (c), Student’s t-tests (d, e and l) or Welch’s t-tests (i) followed by the Holm–Šidák’s multiple comparisons adjustment, or matched samples two-way ANOVAs (f–h, j and k) followed by the Šidák’s multiple comparisons adjustment. All the statistical tests were two-sided. Not significant (NS): P > 0.05.

Consistent with the phenotype observed in LeprCre/+; Ngffl/∆ mice, Prx1–cre; Ngffl/fl mice exhibited normal bone marrow haematopoiesis under steady-state conditions but impaired haematopoietic and vascular regeneration in limb bones. Compared with littermate controls, Prx1–cre; Ngffl/fl mice exhibited normal femur bone marrow, vertebral bone marrow and spleen cellularity (Fig. 4d), and normal frequencies of HSCs and restricted haematopoietic progenitors (Fig. 4e) in femur bone marrow. WBM cells from the femurs of Prx1–cre; Ngffl/fl mice and littermate controls did not differ in their capacity to reconstitute myeloid, B or T cells upon competitive transplantation into irradiated mice (Fig. 4f and Extended Data Fig. 5e–g).

To assess the regeneration of haematopoiesis after irradiation, we lethally irradiated (1,080 rads) and transplanted a radioprotective dose of 1,000,000 WBM cells into 2-month-old Prx1–cre; Ngffl/fl mice and littermate controls. At 28 days after irradiation, the regeneration of bone marrow cellularity (Fig. 4g), HSCs (Fig. 4h), LSK cells (Fig. 4i), LepR+ cells (Fig. 4j) and endothelial cells (Fig. 4k) were all significantly impaired in femur, but not vertebral, bone marrow in Prx1–cre; Ngffl/fl mice. Consistent with this, femur, but not vertebral, bone marrow blood vessels in Prx1–cre; Ngffl/fl mice were leaky at 28 days after irradiation (Fig. 4l). Blood cell counts did not significantly differ between Prx1–cre; Ngffl/fl and littermate control mice before or after irradiation (Extended Data Fig. 5h–j), consistent with the observation that haematopoietic regeneration was impaired only in limb bones. NGF thus acts locally within the bone marrow to promote haematopoietic, stromal and vascular cell regeneration.

Nerve sprouting increases regeneration factor expression

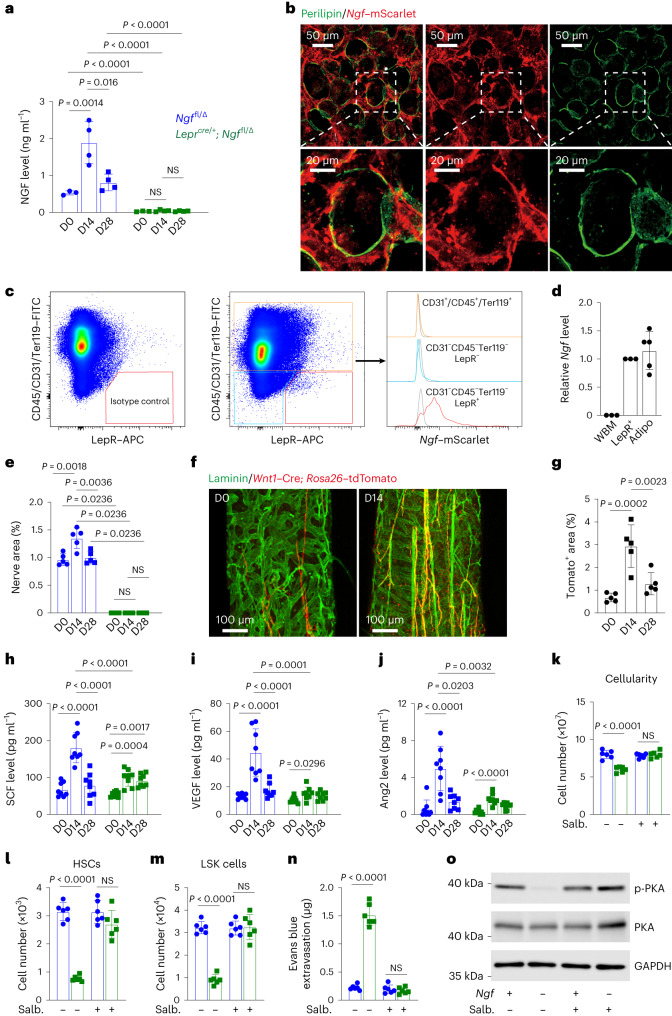

When compared with non-irradiated bone marrow, we observed a significant increase in NGF levels at 14 days after irradiation in 6-month-old control mice but not in 6-month-old LeprCre/+; Ngffl/∆ mice (Fig. 5a). In the bone marrow, Ngf–mScarlet was mainly expressed by adipocytes (Fig. 5b) and LepR+ cells (Fig. 5c and Extended Data Fig. 6a) at 14 days after irradiation. Little or no Ngf–mScarlet expression was observed among haematopoietic/endothelial cells or LepR negative stromal cells in the bone marrow (Fig. 5c). By qRT–PCR, Ngf levels were similar in adipocytes and in LepR+ cells (Fig. 5d).

Fig. 5. NGF from LepR+ cells and adipocytes promotes nerve sprouting after irradiation, increasing the expression of regeneration factors.

a, NGF in bone marrow serum from 6–8-month-old Leprcre/+; Ngffl/∆ and Ngffl/∆ littermate controls before (n = 3 mice per genotype), or 14 (n = 4) or 28 (n = 4) days after irradiation and transplantation of radioprotective wild-type bone marrow cells (three to four independent experiments per timepoint). D, day. b, Perilipin+ adipocytes in a 30-µm-thick section from NgfmScarlet/+ femur bone marrow were positive for Ngf–mScarlet (representative of three experiments). There are also Ngf-expressing LepR+ cells in this image (Extended Data Fig. 6a). c, Flow cytometric analysis of enzymatically dissociated bone marrow from NgfmScarlet/+ mice 14 days after irradiation (four mice from four independent experiments). d, Ngf expression by qRT–PCR (three mice (WBM or LepR+ cells) or five mice (adipocytes) from three independent experiments). e, The area occupied by peripherin+ nerve fibres in bone marrow sections from 6–8-month-old Leprcre/+; Ngffl/∆ and littermate control mice (five mice per genotype per timepoint from five independent experiments). f,g, Representative images (f) and quantification (g) showing that nerve fibres (red) in femur bone marrow sections from 6–8-month-old Wnt1–Cre; Rosa26tdTomato mice before or at 14 or 28 days after irradiation (five mice per timepoint from five independent experiments). h–j, SCF (h), VEGF (i) and Ang2 (j) in bone marrow serum from 6–8-month-old Leprcre/+; Ngffl/∆ and littermate control mice (eight mice per genotype per timepoint from eight independent experiments). k–n, The β2 agonist salbutamol (Salb.) rescued the regeneration of bone marrow cellularity (n = 6) (k) and the numbers of HSCs (n = 6 mice per treatment) (l) and LSK cells (n = 6) (m) as well as the patency of the vasculature (n = 5) (n) in 6–8-month-old Leprcre/+; Ngffl/∆ mice at 28 days after irradiation (five to six independent experiments). o, Western blot of protein from LepR+ cells isolated from Leprcre/+; Ngffl/∆ and littermate control mice at 14 days after irradiation and transplantation (representative of three independent experiments). All data represent mean ± standard deviation. Statistical significance was assessed using two-way ANOVAs followed by Tukey’s (a and h) or Šidák’s (k–n) multiple comparisons adjustments, Mann–Whitney (e) or Student’s t-tests (i and j) followed by Holm–Šidák’s multiple comparisons adjustments for comparisons between mutants and controls, or one-way ANOVAs (e, g, i and j) followed by Šidák’s multiple comparisons adjustments for comparisons between timepoints. All statistical tests were two-sided. Not significant (NS): P > 0.05.

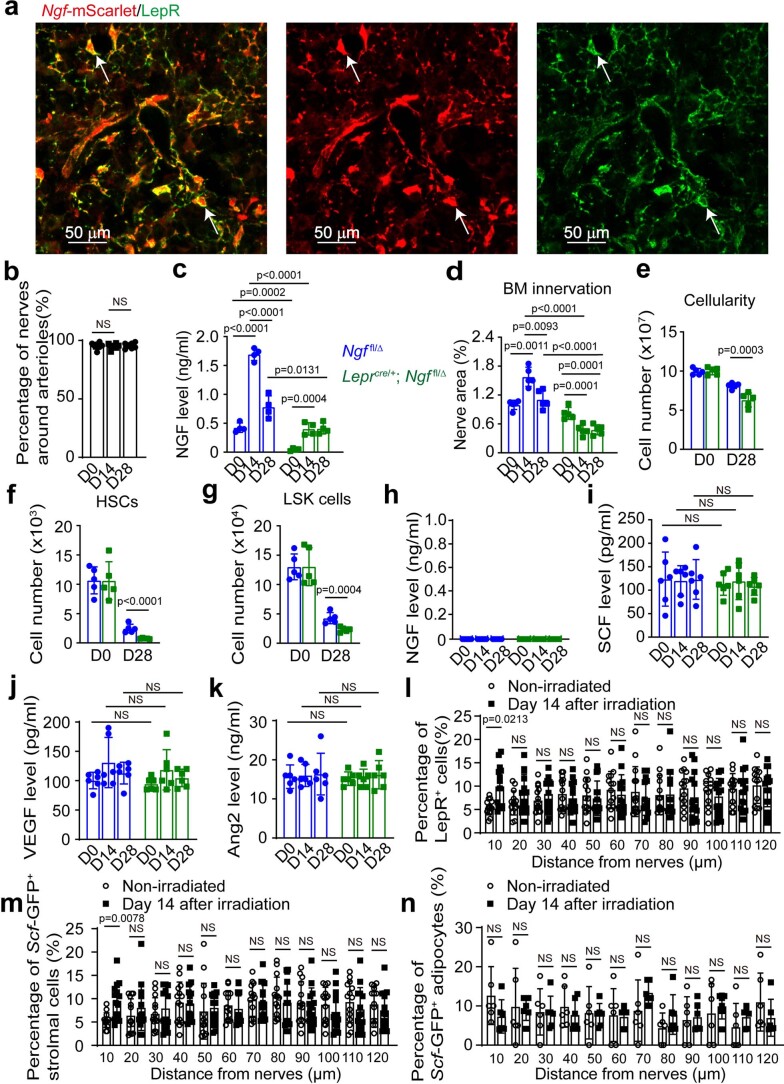

Extended Data Fig. 6. Bone marrow nerve sprouting after myeloablation increases hematopoietic regeneration and growth factor production.

(a) LepR+ cells were positive for Ngf-mScarlet in sections from Ngf mScarlet/+ femur bone marrow at 14 days after irradiation and bone marrow transplantation (representative of 3 experiments). (b) The percentage of nerve fibers in the bone marrow that were within 10 µm of arterioles in Ngf fl/∆ control mice before (D0), or 14 or 28 days after irradiation and transplantation (7 mice from 7 independent experiments per time point). (c) NGF levels in bone marrow serum from 4-5 month-old Leprcre/+; Ngf fl/∆ and Ngf fl/∆ littermate control mice before, or 14 or 28 days after irradiation and transplantation (4 mice per genotype from 4 independent experiments). (d) The area occupied by peripherin+ nerve fibers in bone marrow sections from 4-5 month-old Leprcre/+; Ngf fl/∆ and littermate controls before, or 14 or 28 days after irradiation and transplantation. (e-g) Cellularity (e), number of HSCs (f) and LSK cells (g) in bone marrow (one tibia and one femur) from 4-5 month-old Leprcre/+; Ngf fl/∆ mice and littermate controls 28 days after irradiation and transplantation (a total of 5 mice per genotype from 5 independent experiments in panels d-g). (h-k) Blood serum levels of NGF (n = 5) (h), SCF (n = 6) (i), VEGF (n = 6) (j), and Ang2 (n = 6) (k) from 6 month-old Leprcre/+; Ngf fl/∆ mice and littermate controls before, or 14 or 28 days after irradiation and transplantation (5-6 independent experiments). (l-n) The distance from LepR+ cells (n = 14 mice per treatment) (l), Scf-GFP+ stromal cells (n = 14) (m), and Scf-GFP+ adipocytes (n = 6) (n) to the nearest nerve fiber before or 14 days after irradiation and transplantation (6-14 independent experiments). All data represent mean ± standard deviation. The statistical significance of differences among treatments was assessed using a one-way ANOVA followed by the Sidak’s multiple comparisons adjustment (b and c), Student’s t-tests (c, i-m) or Mann-Whitney tests (n) followed by the Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparisons adjustment, or two-way ANOVAs followed by the Tukey’s (d) or Sidak’s (e-g) multiple comparisons adjustment. All the statistical tests were two-sided. Not significant (NS): P > 0.05.

We observed significantly increased nerve fibre density in control bone marrow after irradiation but not in the bone marrow of 6-month-old LeprCre/+; Ngffl/∆ mice (Fig. 5e). We irradiated Wnt1–cre; Rosa26–tdTomato mice, which express Tomato in neural crest-derived cells, including nerve fibres and Schwann cells44. Nerve fibres were much more abundant in the bone marrow at 14 days after irradiation as compared with non-irradiated controls (Fig. 5f,g). Nerve fibres were closely associated with arterioles under steady-state conditions and after irradiation (Extended Data Fig. 6b). By 28 days after irradiation, when NGF levels in the bone marrow returned nearly to normal (Fig. 5a), the density of nerve fibres also returned nearly to normal (Fig. 5g).

To test if the increase in NGF levels in the bone marrow after irradiation caused nerve fibre sprouting, we examined 4–5-month-old LeprCre/+; Ngffl/∆ mice. These mice had lower levels of NGF in the bone marrow as compared with littermate controls (Extended Data Fig. 6c). They had a normal density of nerve fibres in the bone marrow before irradiation but, unlike control mice, did not exhibit an increase in nerve fibres 14 days after irradiation (Extended Data Fig. 6d). These 4–5-month-old LeprCre/+; Ngffl/∆ mice exhibited delayed regeneration of bone marrow cellularity (Extended Data Fig. 6e), HSCs (Extended Data Fig. 6f) and LSK cells (Extended Data Fig. 6g) as compared with littermate controls. Therefore, the sprouting of nerve fibres in the bone marrow after irradiation occurs in response to increased NGF production by LepR+ cells, and the adipocytes they give rise to, and this accelerates haematopoietic regeneration.

We hypothesized that bone marrow nerve fibres increased the production of growth factors that promote haematopoietic and vascular regeneration. We found by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay analysis that SCF (Fig. 5h), VEGF (Fig. 5i) and Ang2 (Fig. 5j) levels increased significantly in the bone marrow of control mice at 14 days after irradiation but to a significantly lesser extent in the bone marrow of 6-month-old LeprCre/+; Ngffl/∆ mice. By 28 days after irradiation, when NGF levels and nerve fibre density had returned to normal in control mice (Fig. 5a,e), SCF, VEGF and Ang2 levels had also returned to normal (Fig. 5h–j). Each of these factors is necessary for normal haematopoietic35 or vascular regeneration45,46. In contrast to what we observed in the bone marrow, the levels of NGF, SCF, VEGF and Ang2 in the blood did not significantly differ before versus after irradiation, or between LeprCre/+; Ngffl/∆ and littermate control mice (Extended Data Fig. 6h–k).

To test if stromal cells regenerated immediately adjacent to nerve fibres or throughout the bone marrow, we assessed the distances of LepR+ cells, Scf–GFP+ stromal cells and Scf–GFP+ adipocytes to nerve fibres in non-irradiated mice and mice 14 days after irradiation. In both cases, most LepR+ cells, Scf–GFP+ stromal cells and Scf–GFP+ adipocytes were distant from nerve fibres and the percentages of cells in each cell population that were at least 20 µm from nerve fibres did not significantly change between non-irradiated and irradiated mice (Extended Data Fig. 6l–n). This suggested that nerve fibres promoted regeneration throughout the bone marrow, not just immediately adjacent to nerve fibres. On the other hand, the percentages of LepR+ cells and Scf–GFP+ stromal cells that were within 10 µm of nerve fibres were significantly higher in irradiated as compared with non-irradiated mice. Thus, regeneration may have been somewhat enhanced immediately adjacent to nerve fibres.

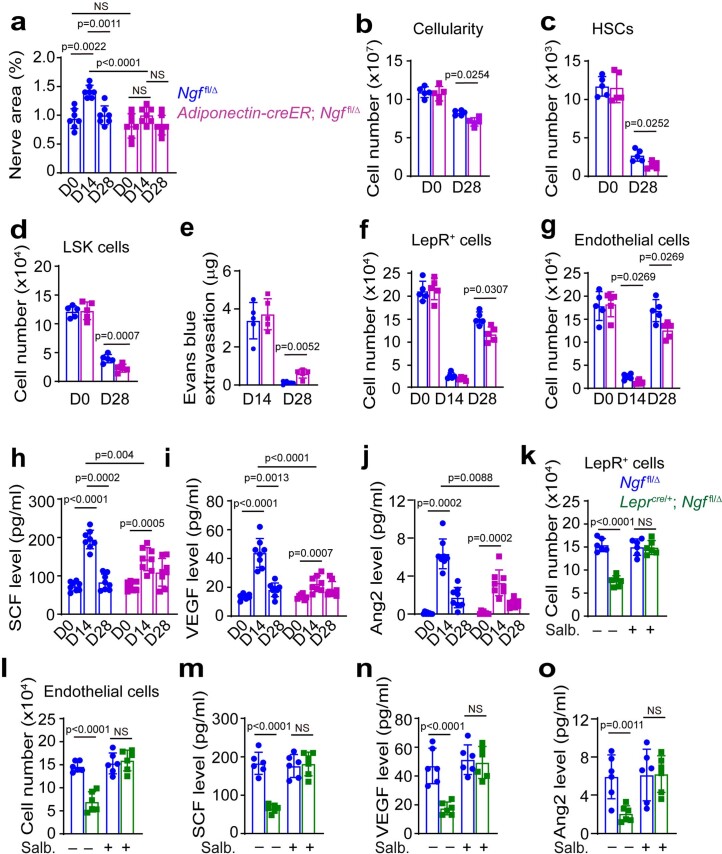

We also used Adiponectin–creER to delete Ngf from LepR+ cells and the adipocytes they gave rise to after irradiation. Nearly all LepR+ cells and adipocytes express Adiponectin and recombine with Adiponectin–creER, including the skeletal stem cells in adult bone marrow34. Tamoxifen was administered to Adiponectin–creER; Ngffl/∆ and littermate control mice at 2–3 months of age, then 2 weeks later the mice were irradiated and transplanted with a radioprotective dose of 1,000,000 WBM cells. At this early timepoint, these mice still had normal numbers of nerve fibres in the bone marrow but they did not exhibit the increase in nerve fibres after irradiation that was observed in control bone marrow (Extended Data Fig. 7a). The Adiponectin–creER; Ngffl/∆ mice also exhibited impaired regeneration of haematopoietic cells (Extended Data Fig. 7b–d), increased vascular leakiness (Extended Data Fig. 7e), reduced numbers of LepR+ cells and endothelial cells (Extended Data Fig. 7f,g) and lower levels of bone marrow SCF, VEGF and Ang2 (Extended Data Fig. 7h–j) after irradiation. Thus, 2–3-month-old Adiponectin–creER; Ngffl/∆ mice phenocopied 4–5-month-old LeprCre/+; Ngffl/∆ mice with reduced nerve fibre sprouting as well as impaired haematopoietic and vascular regeneration as compared with control mice.

Extended Data Fig. 7. Adiponectin-creER; Ngffl/∆ mice exhibit defects in nerve fiber sprouting and hematopoietic and vascular regeneration after irradiation.

(a) The area occupied by peripherin+ nerve fibers in bone marrow sections from 2-3 month-old Adiponectin-creER; Ngf fl/∆ and Ngf fl/∆ littermate controls before, or 28 days after irradiation and transplantation (7 mice per genotype per time point from 7 independent experiments). (b-d) Cellularity (b), numbers of HSCs (c) and LSK cells (d) in bone marrow (one tibia and one femur) from Adiponectin-creER; Ngf fl/∆ and littermate control mice before and 28 days after irradiation and transplantation. (e) Leakage of intravenously-injected Evans blue dye into femur bone marrow at the indicated time points after irradiation and bone marrow transplantation. (f, g) Numbers of LepR+ cells (f) and endothelial cells (g) in the bone marrow before, or 14 or 28 days after irradiation and bone marrow transplantation (5 mice per genotype from 5 independent experiments in panels b-g). (h - j) SCF (h), VEGF (i) and Ang2 (j) in bone marrow serum from 2-3 month-old Adiponectin-creER; Ngf fl/∆ and littermate control mice before, or 14 or 28 days after irradiation and transplantation (a total of 8 mice per genotype per time point from 8 independent experiments). (k-o) When administered to Leprcre/+; Ngf fl/∆ mice after irradiation, the b2 agonist salbutamol rescued the regeneration of bone marrow LepR+ cells (k) and endothelial cells (l) at 28 days after irradiation, as well as bone marrow SCF (m), VEGF (n), and Ang2 (o) levels 14 days after irradiation (6 mice per genotype per treatment from 6 independent experiments). All data represent mean ± standard deviation. Statistical significance was assessed using matched samples two-way ANOVAs followed by the Tukey’s (a, h, and i) or Sidak’s (b, d, f, and k-o) multiple comparisons adjustment, Student’s t-tests (c, e, and g) or Mann-Whitney tests (for genotype comparisons of j) followed by the Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparisons adjustment, or Friedman tests followed by the Dunn’s multiple comparisons adjustment (for time-point comparisons of j). All statistical tests were two-sided. Not significant (NS): P > 0.05.

Nerves activate β adrenergic receptors in LepR+ cells

Sympathetic nerves in the bone marrow release adrenergic neurotransmitters that promote haematopoietic regeneration by activating β2 and β3 adrenergic receptors4. These receptors also modulate myelopoiesis and megakaryopoiesis in ageing bone marrow14,15. Consistent with these results, when we administered salbutamol, a β2 agonist, to LeprCre/+; Ngffl/∆ mice that lacked bone marrow nerve fibres, it rescued the regeneration of bone marrow cellularity (Fig. 5k), HSCs (Fig. 5l), LSK cells (Fig. 5m), vasculature (Fig. 5n), LepR+ cells (Extended Data Fig. 7k) and endothelial cells (Extended Data Fig. 7l).

β adrenergic receptors signal through protein kinase A (PKA) to increase the expression of VEGF by cancer cells47. Consistent with this, LepR+ cells from LeprCre/+; Ngffl/∆ mice had lower levels of phosphorylated PKA (Fig. 5o) and reduced levels of SCF, VEGF and Ang2 as compared with LepR+ cells from control mice at 14 days after irradiation (Extended Data Fig. 7m–o). Treatment of irradiated mice with salbutamol rescued PKA phosphorylation in LepR+ cells from LeprCre/+; Ngffl/∆ mice (Fig. 5o) as well as SCF, VEGF and Ang2 levels in the bone marrow (Extended Data Fig. 7m–o). These data suggest that β adrenergic receptors in LepR+ cells increase the expression of growth factors by promoting PKA signalling.

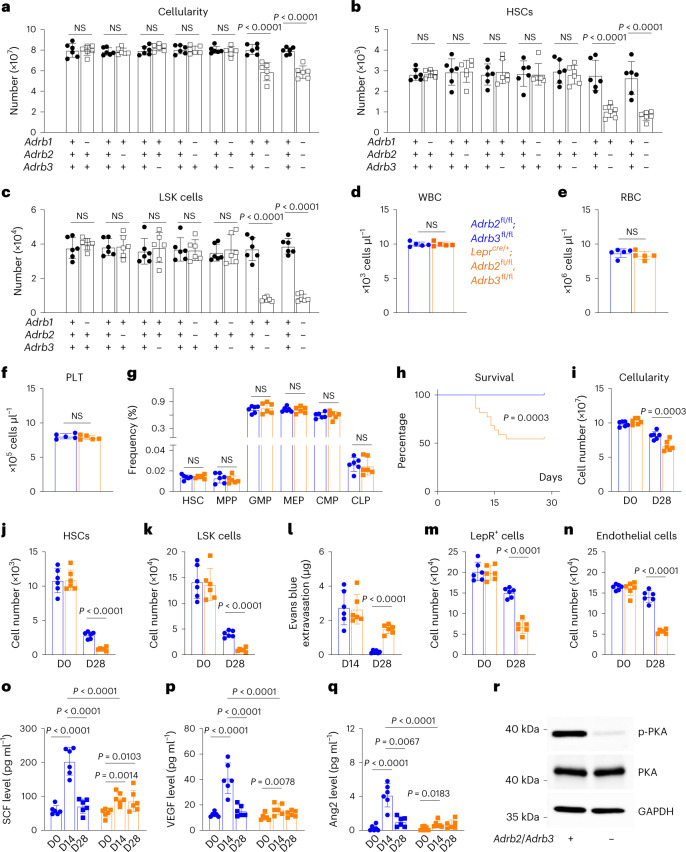

Single-cell RNA sequencing29 showed that Adrb1 was not expressed by bone marrow stromal cells (Extended Data Fig. 8a). Adrb2 and Adrb3 were mainly expressed by LepR+ cells in the bone marrow (Extended Data Fig. 8b,c). By qRT–PCR, we did not detect Adrb2 and Adrb3 expression in unfractionated bone marrow cells but found that Adrb2 and Adrb3 were expressed at similar levels in LepR+ cells and adipocytes (Extended Data Fig. 8d,e). Deficiency for either of these receptors did not significantly impair haematopoietic regeneration (Fig. 6a–c); however, deficiency for Adrb2 and Adrb3 did significantly impair haematopoietic regeneration (Fig. 6a–c). Therefore, β2 and β3 adrenergic receptors both promote haematopoietic regeneration while β1 adrenergic receptor is dispensable.

Extended Data Fig. 8. β-adrenergic receptors are expressed by LepR+ stromal cells and adipocytes in the bone marrow.

(a-c) The expression patterns of Adrb1 (a), Adrb2 (b), and Adrb3 (c) (which encode the β1, β2, and β3 adrenergic receptors, respectively) among non-hematopoietic bone marrow cells based on single cell RNA sequencing from ref. 29. (d-h) Adrb2 (d), Adrb3 (e), Scf (f), Vegf (g), and Ang2 (h) transcript levels by qRT-PCR in unfractionated cells, LepR+ cells, and adipocytes from adult mouse bone marrow 14 days after irradiation and transplantation of a radioprotective dose of bone marrow cells (a total of 3 mice (for unfractionated cells and LepR+ cells) or 5 mice (for adipocytes) from 3 independent experiments). All data represent mean ± standard deviation. (i-l) Generation of Adrb2 flox and Adrb3 flox mouse alleles. (i) The Adrb2 flox allele was generated by inserting loxp elements on either side of exon 1. The insertion sites were chosen to avoid disrupting intron sequences that are conserved among species. Using the Adrb2 flox allele, Cre recombination removed exon 1, which contains the entire Adrb2 coding sequence. (j) PCR genotyping of genomic DNA with the primers shown in panel i confirmed germline transmission of the Adrb2flox allele (representative of three independent experiments). Mice were backcrossed at least five times onto a C57BL/Ka background before analysis. (k) The Adrb2 flox allele was generated by inserting loxp elements on either side of exon 2. The insertion sites were chosen to avoid disrupting intron sequences conserved among species. Cre recombination removed exon 2, which contains the start codon, generating a frameshift mutation. (l) PCR genotyping of genomic DNA with the primers shown in panel k confirmed germline transmission of the Adrb3flox allele (representative of three independent experiments for j-l). Mice were backcrossed at least five times onto a C57BL/Ka background before analysis. All data represent mean ± standard deviation.

Fig. 6. Nerve sprouting after irradiation increases the expression of regeneration factors by activating β adrenergic receptors in LepR+ cells and their progeny.

a–c, Two- to 4-month-old mice, with adrb1, adrb2 and/or adrb3 deficiency, were irradiated and transplanted with radioprotective wild-type bone marrow cells; then the cellularity (a) and numbers of HSCs (b) and LSK cells (c) in the bone marrow (always one tibia and one femur) were analysed 28 days later. d–f, White blood cell (d), red blood cell (e) and platelet (f) counts from non-irradiated 2-month-old Leprcre/+; Adrb2fl/fl; Adrb3fl/fl mice and Adrb2fl/fl; Adrb3fl/fl littermate controls (a total of five mice per genotype from five independent experiments). g, Haematopoietic stem and progenitor cell frequencies in the bone marrow of non-irradiated 2-month-old Leprcre/+; Adrb2fl/fl; Adrb3fl/fl and littermate controls. h, Survival of 2-month-old Leprcre/+; Adrb2fl/fl; Adrb3fl/fl and littermate controls after irradiation and transplantation (22 mice per genotype in 3 independent experiments). i–l, Cellularity (i) and numbers of HSCs (j) and LSK cells (k) in the bone marrow and leakage of intravenously injected Evans blue dye into femur bone marrow (l) of 2-month-old Leprcre/+; Adrb2fl/fl, Adrb3fl/fl and littermate controls at 14 or 28 days after irradiation. D, day. m,n, Numbers of LepR+ cells (m) and endothelial cells (n) in the bone marrow 28 days after irradiation. o–q, SCF (o), VEGF (p) and Ang2 (q) in bone marrow serum from 2-month-old Leprcre/+; Adrb2fl/fl, Adrb3fl/fl mice and littermate controls before (D0) or 14 or 28 days after irradiation (a total of six mice per genotype per timepoint from six independent experiments in a–c, g and i–q). All data represent mean ± standard deviation. r, Western blot of protein from LepR+ cells isolated from Leprcre/+; Adrb2fl/fl, Adrb3fl/fl and littermate control mice 14 days after irradiation (representative of three independent experiments). All data represent mean ± standard deviation. The statistical significance of differences among treatments was assessed using two-way ANOVAs (a–c and i–n) or matched samples two-way ANOVAs (d–f) followed by Šidák’s multiple comparisons adjustment, Student’s t-tests followed by Holm–Šidák’s multiple comparisons adjustments for comparisons among genotypes (g and q), a log-rank test (h), two-way ANOVAs (o and p) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons adjustment, or a one-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons adjustment for comparisons among timepoints (q). All statistical tests were two-sided. Not significant (NS): P > 0.05.

To identify the cells in which β2/β3 adrenergic receptors signal to promote haematopoietic regeneration, we made floxed alleles of Adrb2 and Adrb3 (Extended Data Fig. 8i–l) and conditionally deleted Adrb2 and Adrb3 from LepR+ cells using LeprCre. Two-month-old LeprCre/+; Adrb2fl/fl; Adrb3fl/fl mice had normal vasculature and haematopoiesis under steady-state conditions, including normal blood cell counts (Fig. 6d–f), and frequencies of HSCs and restricted progenitors (Fig. 6g) in the bone marrow. However, when these mice were lethally irradiated and transplanted with radioprotective wild-type bone marrow cells, they were less likely to survive (Fig. 6h), and exhibited impaired regeneration of bone marrow cellularity (Fig. 6i), HSCs (Fig. 6j), LSK cells (Fig. 6k), vasculature (Fig. 6l), LepR+ cells (Fig. 6m) and endothelial cells (Fig. 6n) as compared with littermate controls. LeprCre/+; Adrb2fl/fl; Adrb3fl/fl mice also exhibited significantly reduced levels of SCF (Fig. 6o), VEGF (Fig. 6p) and Ang2 (Fig. 6q) in the bone marrow as compared to littermate controls, as well as reduced PKA phosphorylation in LepR+ cells (Fig. 6r) at 14 days after irradiation. Adipocytes in the bone marrow 14 days after irradiation and transplantation expressed levels of Scf, Vegf and Ang2 that were comparable to LepR+ cells (Extended Data Fig. 8f–h). Bone marrow nerve fibres thus promote regeneration by activating β2/β3 adrenergic receptors in LepR+ cells, and potentially their adipocyte progeny, increasing the production of growth factors by these cells.

Discussion

Nerve fibres in the bone marrow are known to promote haematopoietic regeneration after myeloablation4, but little is known about the mechanism by which nerve fibres are maintained in the bone marrow or how they promote regeneration. Our results reveal a reciprocal relationship between LepR+ stromal cells and nerve fibres in which nerve fibres are maintained by NGF produced by LepR+ cells and, in turn, promote haematopoietic and vascular regeneration by secreting adrenergic neurotransmitters that activate β2/β3 adrenergic receptors in LepR+ cells (see model in Extended Data Fig. 9). Adrenergic receptor activation in LepR+ cells increases the production of multiple growth factors by LepR+ cells, and the adipocytes they give rise to, that promote haematopoietic and vascular regeneration. LepR+ cells, and the adipocytes they give rise to after myeloablation, are the major sources of SCF and VEGF for haematopoietic and vascular regeneration in the bone marrow24,35.

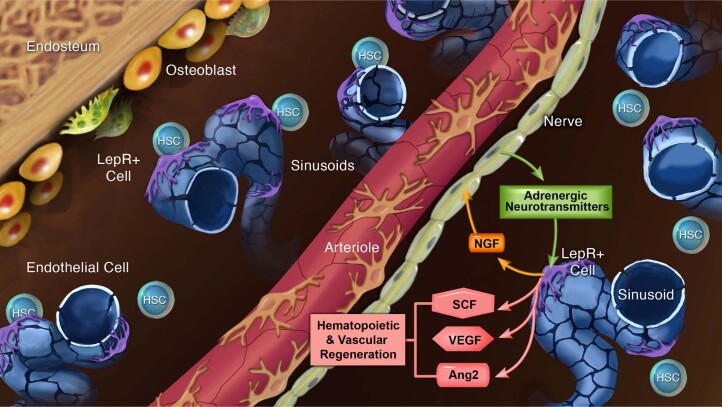

Extended Data Fig. 9. Schematic illustrating a reciprocal relationship between LepR+ stromal cells and nerve fibers in the bone marrow.

The nerve fibers are maintained by NGF produced by LepR+ cells and, in turn, promote hematopoietic and vascular regeneration by secreting adrenergic neurotransmitters that activate β2/β3 adrenergic receptors in LepR+ cells and the adipocytes they give rise to after myeloablation.

Some prior studies of the effects of peripheral nerves on haematopoiesis depended on systemic ablation of sympathetic nerve fibres, such as with 6-hydroxydopamine, raising the question of whether the observed effects reflected local loss of nerve fibres within the bone marrow or more systemic effects. These studies showed that sympathetic nerves regulate circadian variation in HSC mobilization into the blood, as well as the effects of G-CSF on mobilization, by influencing the expression of CXCL12 by stromal cells6,11. Nociceptive nerve fibres promote HSC mobilization by releasing calcitonin gene-related peptide, which activates receptors expressed by HSCs8. In agreement with these studies6,11, we observed that circadian mobilization of haematopoietic progenitors is dependent on bone marrow innervation (Fig. 2h,i), suggesting that this reflects a local effect within the bone marrow.

Nerve fibres localize exclusively around arterioles in both irradiated and non-irradiated mice (Extended Data Fig. 6b) but appear to promote the regeneration of LepR+ cells throughout the bone marrow. The ability of nerve fibres to promote regeneration throughout the bone marrow may be enhanced by the sprouting of nerve fibres after myeloablation. Peripheral nerves also release adrenergic neurotransmitters through non-synaptic volume transmission in which neurotransmitters can diffuse considerable distances away from nerve fibres48,49. LepR+ cells have long processes that allow them to interact with cells that are not adjacent to the LepR+ cell body. Thus, nerve sprouting, volume transmission, long LepR+ cell processes and perhaps other mechanisms that propagate signals among LepR+ cells may enable nerve fibres around arterioles to promote regeneration throughout the bone marrow.

Peripheral nerve fibres are depleted by chemotherapy50 and in diabetes mellitus51. Our results raise the question of whether peripheral neuropathy undermines engraftment in people who receive bone marrow, or other forms of HSC, transplants. Moreover, many people take drugs that block the signalling of β2/β3 adrenergic receptors, such as for heart conditions. Our results raise the question of whether β blockers delay haematopoietic regeneration after transplantation. Another interesting question for future studies is whether nerve fibres also promote the regeneration of non-haematopoietic tissues by sprouting after injury and by promoting the β adrenergic receptor-mediated expression of regeneration factors.

Methods

Mice

All mouse experiments complied with all relevant ethical regulations and were performed according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at UT Southwestern Medical Center (protocol 2017-101896) and the National Institute of Biological Sciences, Beijing (NIBS2022M0024). All mice were maintained on a C57BL/6 background, including Leprcre (ref. 52), Adiponectin–CreER (ref. 53), NG2–DsRed (ref. 54), NG2–CreER (ref. 55), Col1a1–CreER (ref. 56), GFAP–Cre (ref. 57), Rosa26–CAG–loxp–stop–loxp–tdTomato (Ai14; ref. 58), Rosa26–CAG–loxp–stop–loxp–EGFP (Ai47; ref. 59), Col1a1*2.3–EGFP (ref. 60), ScfGFP (ref. 16), Adrb1 null (ref. 61), Adrb2 null (ref. 61), Adrb3 null (ref. 62) and Ngf null mice (ref. 63).

To generate NgfmScarlet mice, CleanCap Cas9 messenger RNA (TriLink) and single guide RNAs (transcribed using MEGAshortscript Kit (Ambion) and purified using the MEGAclear Kit (Ambion)), and recombineering plasmids were microinjected into C57BL/Ka zygotes. The coding sequence for the monomeric red fluorescent protein (mScarlet) was as described64. Chimeric mice were genotyped by restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis and insertion of the mScarlet sequence into the correct locus was confirmed by Southern blotting and sequencing of the targeted allele. Founders were mated with C57BL/Ka mice to obtain germline transmission then backcrossed with wild-type C57BL/Ka mice for at least three generations before analysis.

To generate the Ngf floxed allele, the targeting vector was obtained from The European Conditional Mouse Mutagenesis Program, linearized, and electroporated into C57BL-derived Bruce4 ES cells. Successfully targeted clones were expanded in culture then injected into C57BL/6-Tyrc-2J blastocysts. Chimeric mice were bred with C57BL/Ka mice to obtain germline transmission. The LacZ and neocassette was removed by mating with Flpe mice65 and backcrossed for five generations onto a C57BL/Ka background before analysis.

Genotyping primers

Primers for genotyping NgfmScarlet mice were 5′-GTG TTC TAC TTT GGG TAT TGA ATC C, 5′-CTC CAA CCC ACA CAC TGA CAC TGT C, 5′-GCT TAT AGT AGT CGG GGA TGT CGG C and 5′-CAC TGT GAA AAG ACA GAA GGC ACA ACT AGA G. Primers for genotyping Ngfflox mice were 5′-CTT GTT TTC CAT CAT AGA GTT GGC TTG TT, 5′-CTT ACC TCA CTG CGG CCA GTA TA. Primers for genotyping Adrb2 flox mice were 5′-ACT GCT CCA AGA AGC AGA CTC TG, 5′-GTC GTT GTC ATC ATC ATC ACT GTG. Primers for genotyping Adrb3 flox mice were 5′-AAG ATG TAG ATG GGG GTG CGG TG, 5′-AAA CTA GAG GCG ACC AGA GAG GTC AG.

Flow cytometry

Bone marrow haematopoietic cells were isolated by flushing the long bones using Ca2+- and Mg2+-free Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) (HBSS-free) with 2% bovine serum. Spleen cells were obtained by crushing the spleen between two glass slides. The cells were dissociated into a single cell suspension by gently passing them through a 25-gauge needle and then filtering through 70 μm nylon mesh. HSCs were isolated using anti-CD150 (TC15-12F12.2), anti-CD48 (HM48-1), anti-Sca1(E13-161.7) and anti-c-kit (2B8) along with the following antibodies against lineage markers: anti-Ter119, anti-B220 (6B2), anti-Gr1 (8C5), anti-CD2 (RM2-5), anti-CD3 (17A2), anti-CD5 (53-7.3) and anti-CD8 (53-6.7). Haematopoietic progenitors were isolated with the lineage markers anti-Ter119, anti-B220, anti-Gr1, anti-CD2, anti-CD3, anti-CD5 and anti-CD8 as well as additional antibodies against CD34 (RAM34), CD135 (FLT3) (A2F10), CD16/32 (FcγR) (clone 93), CD127 (IL7Ra) (A7R34), CD43 (1B11), CD24 (M1/69), IgM (II/41),CD44 (IM7), CD41 (MWReg30), CD105 (MJ7/18), CD11b (M1/70), CD71 (R17217) and CD25 (PC61.5). All antibodies were used at 1:200 for flow cytometric analyses, unless otherwise specified. PE–Cyanine7 streptavidin was used at 1:500. DAPI (5 µg ml−1) was used to exclude dead cells.

For flow cytometric analysis of stromal cells, WBM was flushed using HBSS-free with 2% bovine serum then enzymatically dissociated with type I collagenase (3 mg ml−1), dispase (4 mg ml−1) and DNase I (1 U ml−1) at 37 °C for 30 min as described previously23. Samples were then stained with antibodies and analysed by flow cytometry. Goat-anti-LepR-biotin (AF497), BV421 streptavidin (used at 1:500), anti-CD45 (30F-11), anti-CD31 (clone 390) and anti-TER119 antibodies were used to isolate LepR+ stromal cells that were negative for haematopoietic and endothelial markers. For analysis of bone marrow endothelial cells, mice were intravenously injected with 10 µg per mouse of eFluor660-conjugated anti-VE-cadherin antibody (BV13, eBiosciences). Ten minutes later, the long bones were removed and bone marrow was flushed, digested and stained as above. Samples were analysed using FACSAria Fusion or FACSCanto II flow cytometers and FACSDiva (BD) or FlowJo v10.6.1 (Tree Star) software. The flow cytometry gating strategy used for the isolation of haematopoietic stem and progenitor cell populations, LepR+ cells and endothelial cells is shown in Extended Data Fig. 2.

Deep imaging of half bones

Femurs were longitudinally cut in half, then stained, and imaged as described40. The staining solution contained 10% dimethyl sulfoxide, 0.5% IgePal630 (Sigma) and 5% donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Half bones were stained for 3 days at room temperature with primary antibodies. Then specimens were washed three times in PBS at room temperature for 1 day and put into staining solution containing secondary antibodies for 3 days followed by a 1-day wash. Antibodies used for whole mount staining included goat-anti-LepR-biotin (AF497, used at 1:200), rabbit-anti-peripherin (Abcam, used at 1:250), goat-anti-tdTomato (LSBio, used at 1:250), rabbit-anti-mCherry (Takara, used at 1:200), goat-anti-endomucin (R&D Systems, used at 1:250), rabbit-anti-laminin (Abcam, used at 1:250), rabbit-anti-S100B (Abcam, used at 1:250), rabbit-anti-perilipin (Sigma, used at 1:1,000), chicken anti-GFP (Aves Labs, used at 1:250), anti-SMA-FITC (Sigma, used at 1:250), Cy3-conjugated AffiniPure Fab fragment donkey anti-rabbit IgG (used at 1:250), Alexa Fluor-488-conjugated AffiniPure F(ab′)2 Fragment Donkey Anti-chicken IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch, used at 1:250), Alexa Fluor 488-AffiniPure F(ab′)2 Fragment Donkey Anti-Rabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch, used at 1:250) and 555-conjugated donkey anti-goat antibody (Life Technologies, used at 1:250). Images were acquired using Leica SP8 or Leica Stellaris confocal microscopes.

qRT–PCR

For qRT–PCR, cells were flow cytometrically sorted from enzymatically dissociated bone marrow into Trizol (Invitrogen). RNA was extracted and reverse transcribed into complementary DNA using SuperScript III (Invitrogen) and random primers. Quantitative PCR was performed using a Roche LightCycler 480. The primers used for quantitative PCR analysis included mouse Ngf: 5′-CCA AGG ACG CAG CTT TCT ATA C-3′ and 5′-CTG CCT GTA CGC CGA TCA AAA-3′; Actb: 5′-GCT CTT TTC CAG CCT TCC TT-3′ and 5′-CTT CTG CAT CCT GTC AGC AA-3′.

Irradiation and competitive reconstitution assays

Adult recipient mice were irradiated using an XRAD 320 X-ray irradiator (Precision X-Ray) or Cesium-137 Gammacell 1000 irradiator (Best Theratronics) with two doses of 540 rad at least 4 h apart (1,080 rads total). C57BL/Ka (CD45.1/CD45.2 heterozygous) mice were used as recipients. A total of 500,000 unfractionated bone marrow cells from donor (CD45.2) and competitor (CD45.1) mice were mixed and injected intravenously through the retro-orbital venous sinus. Recipient mice were bled from 4 to 16 weeks after transplantation to examine the levels of donor-derived myeloid, B and T cells in their blood. RBCs were lysed with ammonium chloride potassium buffer before antibody staining. The antibodies used to analyse donor chimerism in the blood were anti-CD45.1 (A20), anti-CD45.2 (104), anti-Gr1 (8C5), anti-Mac1 (M1/70), anti-B220 (6B2) and anti-CD3 (KT31.1). For sublethal irradiation, mice were irradiated using a Cesium-137 Gammacell 1000 irradiator (Best Theratronics Ltd.) with one dose of 650 rads.

Bone marrow adipocyte isolation

Bone marrow from mice at 14 days after irradiation and bone marrow transplantation was enzymatically dissociated with DNase I (200 U ml−1), Collagenase type I (3 mg ml−1) and Dispase (2 mg ml−1) at 37 °C for 30 min. Centrifugation was performed at 104g for 5 min at 4 °C, pelleting most cells, including haematopoietic cells and most stromal cells. The floating cells containing mostly adipocytes were transferred to a new tube, washed twice with HBSS, then lysed with Buffer RLT plus before RNA extraction using the Qiagen RNeasy Plus Micro Kit.

Evans blue extravasation assay

As previously described25, mice were retro-orbitally injected with 200 μl of 0.5% Evans blue in PBS and sacrificed 15 min later. Femurs and tibias were collected, crushed, and then Evans blue was eluted in 200 μl of PBS. After a brief centrifugation to pellet cells and debris, the concentration of Evans blue in the supernatant was measured using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific) at a wavelength of 610 nm. Femurs and tibias from mice without Evans blue injection were used as negative controls.

Statistics and reproducibility

In each type of experiment, the number of mice analysed and the number of independent experiments is indicated in the figure legend. Mice were allocated to experiments randomly and samples processed in an arbitrary order, but formal randomization techniques were not used. Data collection and analysis were not performed blind to the conditions of the experiments. Samples sizes were not pre-determined on the basis of statistical power calculations but were similar to those used in prior publications35,36. No data were excluded.

Before analysing the statistical significance of differences among treatments, we tested whether data were normally distributed and whether variance was similar among groups. To test for normality, we performed the Shapiro–Wilk tests when 3 ≤ n < 20 or D’Agostino Omnibus tests when n ≥ 20. To test whether variability significantly differed among groups we performed F-tests (for experiments with two groups) or Levene’s median tests (for experiments with more than two groups). When the data significantly deviated from normality or variability significantly differed among groups, we log2-transformed the data and tested again for normality and variability. If the transformed data no longer significantly deviated from normality and equal variability, we performed parametric tests on the transformed data. If log2 transformation was not possible or the transformed data still significantly deviated from normality or equal variability, we performed non-parametric tests on the non-transformed data.

When data or log2-transformed data were normal and equally variable, statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t-tests (when there were two groups), one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) (when there were more than two groups) or two-way ANOVAs/matched samples two-way ANOVAs (when there were two or more groups with multiple cell populations, tissues or timepoints). When the data or log2-transformed data were normally distributed but unequally variable, statistical analysis was performed using Welch’s t-tests (when there were two groups). When the data or log2-transformed data were abnormally distributed, statistical analysis was performed using Mann–Whitney tests (when there were two groups), Kruskal–Wallis tests (when there were more than two groups) or Friedman tests (when there were more than two groups and samples were matched). After ANOVAs, P values from multiple comparisons were adjusted using Dunnett’s (when there were more than two groups and comparisons were between a control group and other groups), Šidák’s (when there were more than two groups and planned comparisons) or Tukey’s method (when all the pairwise comparisons were performed). After Kruskal–Wallis tests or Friedman tests, multiple comparisons were adjusted using Dunn’s method. Holm–Šidák’s method was used to adjust comparisons involving multiple Student’s t-tests, Welch’s t-tests or Mann–Whitney tests. Log-rank tests were used to assess the statistical significance of survival differences. All statistical tests were two-sided. All data represent mean ± standard deviation. Statistical tests were performed using GraphPad Prism V10.0.0.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Portfolio reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at 10.1038/s41556-023-01284-9.

Supplementary information

Source data

Statistical source data.

Statistical source data.

Statistical source data.

Statistical source data.

Statistical source data.

Unprocessed images.

Statistical source data.

Unprocessed images.

Statistical source data.

Unprocessed images.

Unprocessed images.

Statistical source data.

Statistical source data.

Statistical source data.

Statistical source data.

Statistical source data.

Unprocessed images.

Acknowledgements

S.J.M. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) Investigator, the Mary McDermott Cook Chair in Pediatric Genetics, the Kathryn and Gene Bishop Distinguished Chair in Pediatric Research, the director of the Hamon Laboratory for Stem Cells and Cancer, and a Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas Scholar. This study was supported partly by funding from the National Institutes of Health (DK118745 to S.J.M.), the Josephine Hughes Sterling Foundation (to S.J.M.), the Kleberg Foundation (to S.J.M.), and the Moody Medical Research Institute (to S.J.M.). B.S. was supported by startup grants from the National Institute of Biological Sciences, Beijing, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82272563). S.F. was supported by startup grants from China Pharmaceutical University (3150140001) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82203653). A.T. was supported by the Leopoldina Fellowship Program (LPDS 2016-16) of the German National Academy of Sciences and the Fritz Thyssen Foundation. We thank the BioHPC high performance computing cloud at UT Southwestern Medical Center for providing computational resources and the Moody Foundation Flow Cytometry Facility. This article is subject to HHMI’s Open Access to Publications policy. HHMI lab heads have previously granted a non-exclusive CC BY 4.0 licence to the public and a sublicensable licence to HHMI in their research articles. Pursuant to those licences, the author-accepted manuscript of this article can be made freely available under a CC BY 4.0 licence immediately upon publication.

Extended data

Author contributions

B.S. and S.J.M. conceived the project, designed and interpreted the experiments. B.S. performed most of the experiments, with technical assistance and discussions from C.E., A.T., J.M.U., G.M.C. and S.F. J.G.P. and M.M.M. discovered that NGF deletion in LepR+ cells led to bone marrow denervation. M.M.M. developed a deep imaging protocol that enables immunofluorescence analysis of nerve fibres during bone marrow regeneration. X.G. generated and characterized the Ngf–mScarlet allele and the β adrenergic receptor floxed mice with assistance from Y.N., M.Y., Y.Z. and J.G. N.K. performed single-cell RNA sequencing. Z.Z. performed bioinformatic and statistical analyses. B.S. and S.J.M. wrote the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Cell Biology thanks John Chute, Daniel Lucas and Meng Zhao for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Data availability

Microscopy and flow cytometry data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contacts upon reasonable request. Published microarray data that were re-analysed in this study are available in the NCBI GEO database under accession code GSE33158. Published bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing data that were re-analysed in this study are available in the NCBI BioProject database under accession codes PRJNA914703 and PRJNA835050. Source data are provided with this paper. All other data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Bo Shen, Email: ShenBo@nibs.ac.cn.

Sean J. Morrison, Email: Sean.Morrison@UTSouthwestern.edu

Extended data

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41556-023-01284-9.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41556-023-01284-9.

References

- 1.Kumar A, Godwin JW, Gates PB, Garza-Garcia AA, Brockes JP. Molecular basis for the nerve dependence of limb regeneration in an adult vertebrate. Science. 2007;318:772–777. doi: 10.1126/science.1147710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mahmoud AI, et al. Nerves regulate cardiomyocyte proliferation and heart regeneration. Dev. Cell. 2015;34:387–399. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fukuda T, et al. Sema3A regulates bone-mass accrual through sensory innervations. Nature. 2013;497:490–493. doi: 10.1038/nature12115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lucas D, et al. Chemotherapy-induced bone marrow nerve injury impairs hematopoietic regeneration. Nat. Med. 2013;19:695–703. doi: 10.1038/nm.3155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamazaki S, et al. Nonmyelinating Schwann cells maintain hematopoietic stem cell hibernation in the bone marrow niche. Cell. 2011;147:1146–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katayama Y, et al. Signals from the sympathetic nervous system regulate hematopoietic stem cell egress from bone marrow. Cell. 2006;124:407–421. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fielding C, et al. Cholinergic signals preserve haematopoietic stem cell quiescence during regenerative haematopoiesis. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:543. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-28175-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao X, et al. Nociceptive nerves regulate haematopoietic stem cell mobilization. Nature. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-03057-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tikhonova AN, Aifantis I. Pain-sensing neurons mobilize blood stem cells from bone marrow. Nature. 2021;589:520–521. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-03577-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lucas D, Battista M, Shi PA, Isola L, Frenette PS. Mobilized hematopoietic stem cell yield depends on species-specific circadian timing. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:364–366. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mendez-Ferrer S, Lucas D, Battista M, Frenette PS. Haematopoietic stem cell release is regulated by circadian oscillations. Nature. 2008;452:442–447. doi: 10.1038/nature06685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Y, et al. Dopamine signaling regulates hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell function. Blood. 2021;138:2051–2065. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020010419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park MH, et al. Neuropeptide Y regulates the hematopoietic stem cell microenvironment and prevents nerve injury in the bone marrow. EMBO J. 2015;34:1648–1660. doi: 10.15252/embj.201490174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ho YH, et al. Remodeling of Bone Marrow Hematopoietic Stem Cell Niches Promotes Myeloid Cell Expansion during Premature or Physiological Aging. Cell Stem Cell. 2019;25:407–418.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2019.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maryanovich M, et al. Adrenergic nerve degeneration in bone marrow drives aging of the hematopoietic stem cell niche. Nat. Med. 2018;24:782–791. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0030-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]