Abstract

The rapid growth of digital financial services especially during the COVID-19 outbreak, is a factor accelerating the use of online loan applications that inevitably require the knowledge of digital finance. This study used the behavior change theory and digital financial literacy to identify relevant and correlated variables to confirm positive motivational factors on digital financial skills and capability. Structure equation modeling (SEM) and path analysis were applied to find the correlation and confirm the proposed hypotheses presented. There were 400 samples of small entrepreneurs from different provinces, and online questionnaires were used for data collection. The findings showed that the knowledge and motivation variables were related and had a positive effect. It contributes to continuously building up the skills and capabilities of small entrepreneurs who need to develop their capabilities in digital financial literacy adequately in line with the changes in business and technology after the outbreak of COVID-19. This concept can apply to online loan policy for small entrepreneurs trained with motivating courses who accepted digital finance literacy's usefulness.

Keywords: Digital financial literacy, Digital financial capability, Motivation factor, Online loan, I-change model, Behavior change theory

1. Introduction

The rapid evolution of the digital finance landscape has led to increased complexity and heightened security requirements across various financial platforms. However, the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019 prompted a significant change in the accessibility and utilization of digital financial services [1]. This shift has been marked by a predominant reliance on mobile applications for financial transactions, intended to reduce in-person contact. Because most of the financial transactions are on the application to reduce contact for offline transactions [2]. Especially during the pandemic, digital financial transactions, whether receiving welfare from the Government payment for products and services, including various loans, will be online, which inevitably causes more use of digital financial services.

Thailand stands out as a nation that provides significant support for entrepreneurial loans. In line with earlier research and as indicated by the economic analysis conducted by the Bank of Thailand, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) play a pivotal role in propelling the country's economy, contributing to 35.6% of the gross domestic product (GDP) [3]. Small entrepreneurs, particularly those who primarily operate via online platforms, are instrumental in stimulating economic growth [4]. This raises the questions: Why do numerous small entrepreneurs seek assistance in accessing digital financial services, despite the availability of multiple digital financial support agencies? What factors can facilitate the development of digital financial competencies, and how can the government enhance the accessibility of digital financial services for small entrepreneurs in Thailand as the economy expands? Acquiring proficiency in digital finance remains challenging due to the uneven distribution of knowledge. Furthermore, merely possessing knowledge may not suffice, as the ability to apply it to acquire new skills and behaviors is also vital. Consequently, the motivational aspect emerges as a critical determinant when evaluating the success of small entrepreneurs [5].

Nonetheless, service users are still required to acquaint themselves with intricate digital financial services [6]. Changing the behavior of people who need to do activities on technology devices to go online is challenging [7]. It is important to note that digital financial services serve as a critical driver of business operations and the overall sustainability of the economy [8]. Hence, possessing adequate financial literacy skills becomes a prerequisite for safely accessing such advanced services [9]. Proficiency in the fundamentals of digital finance empowers individuals to navigate technological devices, opt for applications, complete registration processes, verify their identity, and securely submit loan applications [10]. Users gain the ability to select financial services or products tailored to their business needs, perform intricate calculations involving interest rates and payment methods, especially when accessing online loan services, which entail numerous steps and processes, including identity verification, financial documentation submission, and credit assessment. All of these factors significantly influence the decision-making and behavior of applying for online loans. This research consequently raises the question of how small entrepreneurs can be incentivized to enhance their competence in digital financial literacy.

Digital financial literacy encompasses the utilization of software or applications on personal digital devices to access financial services and products. It derives from digital literacy and digital finance, which are the competencies that are pivotal for effectively operating and expanding within the grassroots economy of developing nations [11]. An online loan, a fundamental digital financial service, plays a crucial role in fortifying financial stability and promoting business growth, offering the advantage of lower interest rates compared to conventional loan applications. Additionally, it provides accessibility, time-saving, benefits, streamlines procedures, and facilitates rapid financial status assessment. Nevertheless, a deficiency in workforce proficiency poses limitations on both digital and financial skills [12]. Thereby impacting decisions regarding financial and security service selection. Such limitations can lead to operational stagnation and even business dissolution. Previous research has underscored the significance of appropriate knowledge and motivation in the development of new skills and behaviors [13]. The acquisition of these knowledge and competencies empowers small entrepreneurs to access digital financial service platforms.

Numerous sectors are invested in the advancement of entrepreneurial endeavors, with the financial sector, primarily government-sponsored, serving as a key proponent of this support. As a result, there are diverse sources of funding available for entrepreneurs to comprehensively utilize financial services. However, the proficiency of small entrepreneurs has not evolved adequately to keep pace with the evolving landscape of digital financial platforms [14]. Furthermore, small entrepreneurs have historically been compelled to rely on informal funding sources characterized by elevated interest rates and rigorous repayment requirements. In addition, prior research has indicated that solely providing digital financial literacy training to small entrepreneurs may prove insufficient in cultivating new competencies and behaviors in the realm of digital financial literacy [15]. The acquisition of these skill sets would empower small entrepreneurs to navigate and utilize financial products within digital financial service platforms.

In addition to addressing digital financial literacy, the primary objective of this study is to stimulate entrepreneurs to acquire the requisite skills and enhance their capabilities in line with the evolving landscape of financial technology [16]. The motivational elements encompass facets related to attitude and self-efficacy. Small entrepreneurs must cultivate a positive attitude towards digital finance literacy, coupled with a belief in their capacity to proficiently utilize technological devices [17]. This entails the development of skills tailored for online systems and the acquisition of fundamental knowledge concerning digital finance. They must also become adept in utilizing technological tools to manage applications, complete registration processes, verify their identity, and securely submit loan application documents online. Also, customers are recommended to select financial services or products aligned with their business needs which would help them navigate the complexity of interest rate calculations and payment methods [18]. In this study, a comprehensive review of previous literature was conducted to identify factors related to digital financial literacy, alongside relevant theories and models to elucidate behavioral changes in the context of digital financial literacy development. Additionally, structural equation modeling statistics were employed to discern the relationships among these variables.

This study aims to construct a conceptual model elucidating the interplay of variables and the factors associated with the enhancement of digital financial competencies. It pursues its objectives through two distinct avenues. Firstly, this research underscores the significance of digital finance literacy and the pivotal motivation factors that drive the development of proficiencies among small entrepreneurs, thereby enabling them to access online loans, and ultimately impacting Thailand's economic growth exponentially. Secondly, this study establishes a nexus between digital financial literacy and motivation, facilitating the continual and sustainable cultivation of skills and behaviors among small entrepreneurs, imperative for them to stay aligned with technological advancements. It also opens up the prospect of enhancing the digital financial capabilities of small entrepreneurs who need to concurrently nurture their digital technology and digital finance aptitudes. This inquiry is centered on small entrepreneurs in Thailand who already possess access to digital technology but seek to acquire digital financial competencies across numerous online platforms.

2. Theoretical background

2.1. Behavior change and KAB model

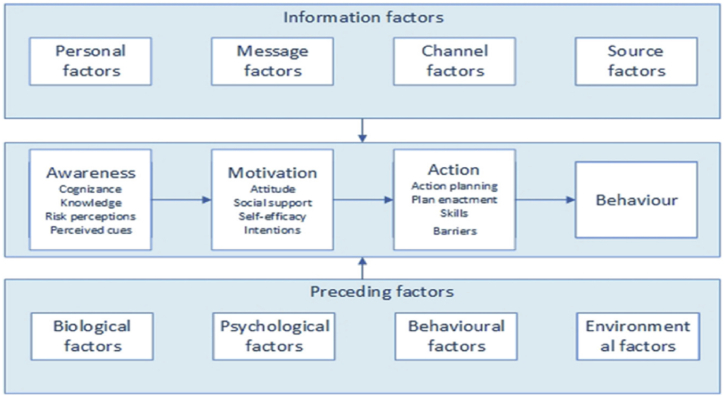

In this study, we use the I-Change Model or Integrated Model to explain changes in financial behavior [19]. From the development of knowledge and motivational factors until the development of digital financial skills and capabilities, there is an assessment before and after the training in digital financial literacy. It is a theory that combines the concepts of Bandura's Cognitive Theory, HBM, Planned Behavior Theory, Prochaska Theoretical Model, and Goal Setting Theory [[20], [21], [22], [23]]. The I-Change Model defines three stages of behavioral change: before motivation or perception, motivation, and after motivation or action [24]. Previous research has defined the I-Change Model as a behavioral change model derived from a self-efficacy model that influences social attitudes, which states motivation or intention of a person defines covert and overt behavior in some actions that are driven by perceived factors (e.g., knowledge, perception of risk) [25]. The order of perception of motivation, action, and behavior depends on the person's primary factors (e.g., biological, psychological, and pre-behavior) [26]. Social and environmental factors and information (e.g., message, channel, source) [27]. It was positively correlated with one's attitude and self-efficacy. It affects entrepreneurs' positive correlation of behavior after acquiring knowledge and competence in digital finance see Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The I-change model factor to analysis and synthesis variable.

Source: De Vries H.,(2017) [28].

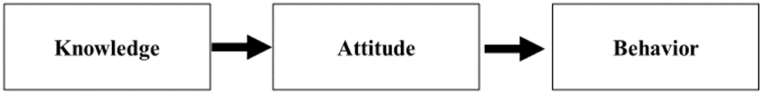

Previous studies on the Knowledge Attitude Behavior Model (KAB) were applied to studies with Bloom's theory [29]. Continuing to study how data processing models are viewed as particularly suitable for health promotion campaigns, careful study is recommended in health promotion situations [30]. On the other hand, finance is used to study the relationship between financial knowledge, financial attitude, and financial behavior, for example, studying the financial literacy level of high school students in the Netherlands with variables of knowledge, attitude and behavior, examining the relationship of financial literacy with credit card use behavior [31]. Both of which were concluded, the corresponding conclusion is financial knowledge has a positive effect on financial attitudes, and financial attitudes have a positive effect on financial behavior see Fig. 2. The relationship between these three dimensions—knowledge, attitude, and behavior—is dynamic and sometimes interchangeable, therefore beneficial.

Fig. 2.

Knowledge, attitude, and behavior model.

Source: P. G. Schrader and K. A. Lawless.,(2004) [29].

2.2. Digital financial literacy as knowledge

Previous research has defined digital financial literacy in different ways. For example, they measured problem-solving ability in a new, digital-enriched environment in the OECD Adult Skills Survey, a program for assessment [32]. International Adult Talent (PIAAC) is born from the degree to which digital technology communication tools and networks are used to obtain and assess interpersonal and practical information [33]. Financial ability and digital knowledge the experience of AFI network members shows that the concept of DFL extends to awareness/and knowledge of the Digital Financial Service (DFS) and the ability to use the relevant DFS independently [34]. Awareness/knowledge of the risks associated with the relevant DFS, the ability to prevent these risks when using DFS, and awareness/knowledge of the relevant consumer protection and restitution mechanisms. The ability to seek the same when needed [6].

Although previous research has not explicitly examined the impact of DFL on digital financial capability (DFC) behavior, insights into the effects of financial literacy on DFC behavior can be used to explain the relationship between DFL [19]. First, on the DFC's incentives, actions, and behaviors in defining digital financial literacy (DFL), it is necessary to review the general literature on financial literacy (FL). There is no widely accepted definition for DFL or Standard methods of digital financial literacy measurement tools [18]. However, they are internationally recognized [[3], [4], [5],13,19,[35], [36], [37], [38]]. This study aims to fill the knowledge gap in digital finance and motivation for developing digital financial literacy and skills to safely access digital financial services through online loan applications for small entrepreneurs who need knowledge and digital financial skills to access digital financial services securely Table 1. showing that represents previous research in the definition of DFL, where the researcher analyzed and synthesized it to find gaps in the research.

Table 1.

A summary of Digital Financial Literacy Definition (DFL).

| Author | Definition |

|---|---|

| OECD (2019) | DFL is the ability of an individual to make informed decisions on basic financial practices. |

| Alliance for Financial Inclusion AFI, (2021) | DFL is a multi-dimensional concept that integrates financial literacy, financial capability, and digital literacy. |

| Anna Lo Prete et al. (2019) | DFL is the use of software applications through personal digital devices to access financial services and products, the so-called fintech, which has offered new investment opportunities as well as risks for individual investors in direct control of their finance. |

| Josephine Kass-Hanna et al. (2022) | Financial literacy is recognized as an essential instrument for cultivating the financial awareness, knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behaviors necessary for individuals to effectively access and use these services. |

| Carlin et al., 2019; Vogels and Anderson, 2019 |

DFL is effective for individuals participating in the digital economy, they need to have the knowledge and skills to perform digital financial transactions and operate digital devices such as mobile phones, smartphones, and tablets |

| Lyons and Kass-Hanna (2021) | DFL is also a necessary catalyst for facilitating access to and usage of digital financial products and services. DFL is defined as a combination of both FL and DL, which includes basic financial knowledge and basic digital skills. |

| Azeez NP Abdul et al., 2019 | Digital financial literacy is boosting communication with the modern world and better access to professional opportunities, major sections of our society are still deprived of these positive changes or the changes are at a much slower pace among these sections of the society. |

Source: Author Own (2023)

The multidimensional concept of the DFL combines financial literacy. Financial capability and digital literacy [3]. Digital literacy involves acquiring knowledge, techniques, attitudes, and personal qualities [27,37]. Finance literacy refers to the level of understanding of small entrepreneurs in using technology to access financial services [14]. There are opinions that digital financial literacy has a positive effect on attitudes [22]. Self-efficacy and digital financial capability respectful use of technology and financial literacy have fueled these assumptions [18].

Hypothesis H1a

Digital financial literacy positively correlated with digital attitudes and financial attitudes.

Hypothesis H1b

Digital financial literacy positively correlated with the self-efficacy of using financial applications.

2.3. Motivation factor

In another example, Hagger, & Chatzisarantis integrated the theory of planned behavior and the theory of self-determination [38]. They found that the role of self-determination motivation, the primary factor, could influence almost all of one's attitudes and self-efficacy [28]. The study explored the role of digital attitudes and knowledge in achieving self-efficacy. Previous studies have indicated that attitude is a vital learning influence [39]. However, students' attitudes toward online distance education differ from their attitudes to face-to-face teaching [40].

In the same way, Digital literacy is a significant influence on learning [41]. Indeed, digital literacy is associated with learner independence [42]. Significant influence on learning, but no attempt was made to link these factors to self-efficacy. Previous research has shown that people acquire financial literacy through formal educational networks and interactions with socialization agents such as friends, family, and the media [43]. Money attitudes (such as the perception of money as a reward for treatment efforts or goals) can also significantly increase motivation for gaining more knowledge about financial management [44]. Moreover, different perceptions of money are related to financial knowledge and behavior [45,46].

Attitudes are key to understanding and developing human behavior [45]. Therefore, predicting digital financial literacy, beliefs, perceptions, assessments, or technology usage attitudes is an important complement to digital literacy, financial, technology, and application of Digital technology skills [46]. This study analyzed the attitudes toward small entrepreneurs' financial literacy to develop digital financial skills and capabilities. A positive attitude toward digital finance literacy will also positively correlate with digital finance skills and capabilities [47]. Therefore, we hypothesize.

Hypothesis H2

A attitude toward digital financial literacy positively correlated with skills digital and financial.

Self-efficacy is an essential part of self-concept [48]. High self-efficacy is closely related to feelings of independence and the ability to control self-learning processes [49]. Thus, cognitive abilities can influence financial behavior through self-efficacy and self-efficacy [50]. Competency fields refer to the skills required for making appropriate financial decisions, such as data processing and problem-solving abilities, Memory function, and mathematical skills [51]. Therefore, cognitive abilities can be expected to reflect differences in individual capacities and help explain the variability of financial results [52]. About self-efficacy channels, an individual's cognitive abilities and subsequent success can significantly impact people's belief in their ability to control and influence aspects of life, namely, self-efficacy [53]. People with lower self-confidence expect less benefit from their current efforts showing less patience with financial problems [54]. Consequently, fewer financial goals are achieved, and lower-quality financial decisions are obtained [20,[55], [56], [57], [58], [59]].

High self-efficacy is closely associated with feelings of autonomy and the ability to self-regulate a learning process [49]. In this study, self-efficacy was Defined as the ability to use digital financial services on digital platforms; it was found that self-efficacy contributed to the development of digital financial literacy skills and digital financial performance. We hypothesize.

Hypothesis H3

Self-efficacy has a positive correlation between the development of financial digital literacy skills and digital financial performance.

2.4. Digital financial skills and digital financial capability

Technological advancement and digital transformation have increased the need to develop certain skills to make prudent decisions. A report by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development states that skills are required to reap the advantages of the digital revolution, protect oneself from the impending risks involved in digital financial services, understand complex information, and make informed financial choices [60]. Some consider having better skills and basic financial knowledge as prerequisites for proper financial transactions [61]. More specifically, elevated levels of cognitive skills, such as learning rate and reasoning ability, lead to fewer financial errors, low payment default, and portfolio diversification, all of which are outcomes of rational financial decisions [62]. The origins of this concept lie in self-efficacy theory, in which individual cognitive abilities and subsequent accomplishments can significantly affect people's belief in their ability to influence various aspects of life [63].

This study paper explores how skills related to budgeting, analysis, and financial expertise have an impact on determinants of sound financial decision-making (FDM), namely, DFL and financial autonomy [7]. Concerning the constituents of the skills re-viewed, analytical thinking refers to the identification of patterns and discrepancies, and the ability to manage funds and allocate them across a specific period to the right purpose is called budgeting skill [64]. In the context of sound financial decision-making (FDM), having financial acumen is crucial. Financial acumen refers to essential financial skills that enable one to assess the financial connections and consequences of different financial choices and understand their impact on overall financial well-being (FWB) [65]. Financial acumen is a vital precursor to sustainable individual and social development as it leads to financial comfort due to sustainable decision-making [66].

We contend that skills related to budgeting, analysis, and financial expertise serve as the foundation for improved reasoning and confidence in utilizing digital financial tools. Individuals equipped with the necessary mathematical, critical, and analytical abilities and financial acumen are better positioned to comprehend, assess, employ, and compare the array of online financial products and services available in today's intricate financial environment [60]. Furthermore, the combined influence of these skills results in subconscious self-empowerment and a positive outlook on managing financial choices autonomously, thereby facilitating the attainment of financial independence [67]. However, extant research overemphasizes financial literacy [68,69] and downplays the integrated effect of analytical, budgeting, and financial acumen as more of a practice approach than an intellectual process that creates the context for dealing with financial behavior [7].

This study presents information on digital and financial literacy for small entrepreneurs. The OECD Survey of Adult Skills measures proficiency in problem-solving in a technology-rich environment as the level of skills needed to use digital technology, communication tools, and networks to acquire and evaluate information, communicate with others, and perform practical tasks [[68], [70], [71]]. Accordingly, adults (15–65 years old) are digitally literate if they are at least able to use ICT tools and applications to achieve a goal (e.g., fill in an online form). In this study, small entrepreneurs' digital finance literacy skills and motivation factors by attitude and self-efficacy variables, directly correlate with their digital financial capability in accessing digital financial services [69]. Digital financial skills and abilities are part of the behavior of small entrepreneurs. Therefore, we hypothesize that.

Hypothesis H4

digital finance literacy skills positively correlated with the digital finance capability of small entrepreneurs.

Financial capability constitutes a comprehensive concept encompassing individuals' knowledge and skills to comprehend their financial circumstances, coupled with the motivation to take proactive steps. Financially capable consumers engage in effective planning, understand information acquisition, discern the appropriate moments to seek advice, and has the ability to comprehend and act upon such advice. This proficiency leads to heightened engagement in financial services, fostering greater participation in the financial market [72]. Our focus lies in the definition and measurement of digital financial capability (DFC), a factor that exerts significant influence on small entrepreneurs, affecting their innovation and financial performance [5]. Furthermore, this investigation delineates the pathways through which DFC impacts these entrepreneurs’ performance, encompassing sales, borrowing, and investment activities. Additionally, the study on DFC holds promise for vulnerable populations, particularly those residing in rural or underdeveloped regions [73]. Notably, financial competence markedly differs from financial literacy, as it places emphasis on behavior, incorporating tangible interactions with the financial environment. Given the potential challenges in translating knowledge into action, pioneering research has explored financial competence as an alternative approach [4]. Rather than providing a simplistic definition, this study deliberate on the rationale for prioritizing financial competence over financial literacy and elucidate the constituent elements of financial capability. In this context, we encompass five domains of DFC knowledge, skills, and behavior: Achievement, Tracking, Planning, Product selection, and Being informed [74].

3. Method

3.1. Research design

This study examines the factors affecting the development of small entrepreneur capacity in developing countries. The research methodology is structured in three key components: The first part involves conducting a Systematic Literature Review, where existing research is comprehensively examined to identify factors or models pertinent to this study. In the second part, we delve into a Literature Review encompassing relevant theories, such as Grounded Theory, Behavioral Change Theory, and Technology Acceptance Model, which serve as guiding frameworks to elucidate the research question. The third part entails the exploration of interrelationships among variables through the application of a statistical technique known as the Structural Equation Model (SEM), involving path analysis to discern the presence of positive and consistent relationships among the variables in this research. This approach has been chosen after a thorough review of the literature, indicating its superior suitability for addressing the research inquiries compared to alternative methods.

Based on a literature review using Digital Literacy and Financial Literacy as the main keywords in this study, it was found that research on digital literacy behavior and use of technology [[75], [76]]. Most studies are on technology adoption to predict continued usage and use theories related to technology adoption, such as Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT), Social Cognitive Theory (SCT), and Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [28,[77], [78],79,80]. In research of behavioral health technology, Health Believe Model (HBM), application use, website, and sensors to intervene in patient behavior [21]. In research of financial, Knowledge Attitude Behavior (KAB) theory describes the factors that affect each other for financial literacy behavior. The attitude and behavior of financial literacy study examined interventions in financial literacy behavior with behavioral change theory [29,31]. The researcher has reviewed the previous literature to apply financial literacy theory and behavior change theory to find the relevant variables in the development of digital financial capability as shown in Table 2. It was concluded that the I-change model, which is the appropriate model to study with the theoretical model in this study.

Table 2.

The DL, FL, and DFL variables were summarized in previous studies to determine their relationship in behavior change theory and technology acceptance models.

| Behavior Change Theory |

Acceptance Model |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literacy areas | Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) | Health Belief Model (HBM) | I-change Model | Transtheoretical Model (TTM) | Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) | The technology of Acceptance Model (TAM) | Unified Technology of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) |

| 1. Digital Literacy | – | * | * | * | – | * | * |

| 2. Financial Literacy | – | – | * | – | – | – | * |

| 3. Digital Financial Literacy | * | * | * | * | * | – | – |

Source: Author Own (2023)

This research was designed according to the principle of Theory-Development Design. It used quantitative methods and SEM-path analysis to correlate whether Digital finance literacy and motivation factors affect skills and digital financial capability (new behavior) see Fig. 3. The correlation of statistical variables can be used theoretically to explain the correlation of variables to create an explanatory conceptual model. The phenomenon of capability development in digital financial literacy occurred.

Fig. 3.

The conceptual model. Note(s): This figure is provided based on prior studies and relevant literature.

Source: Authors own (2023)

3.2. Data gathering

Systematic reviews of previous literature and an analysis of theoretical variables from previous research related to digital financial literacy and behavior change theory [5,36,[80], [81], [82]] were conducted. The correlation of the theoretical variables involved was identified and the results were summarized in the form of a table, including research gaps. Theoretical gaps Include the determination of relevant variables to the research. Research hypotheses were determined. From the conceptual model of the research, 5 hypotheses were set to show the path (direction) and examine the relationships of variables in the conceptual model.

This study identifies the research sample group, where sample group in this study is small entrepreneurs in the metropolitan area. The researcher calculated the sample size by the Taro-Yamane formula for the sample size of this study of 400 samples to avoid errors that may occur from incomplete questionnaires. The researcher, therefore, collected 20 sets of backup questionnaires, totaling 420 sets of questions. Determine research tools (Research Tools), The researcher has used a questionnaire through the website with the Google Form tool that has been trusted and accepted. Have the ability to collect data and access target groups conveniently and quickly by using a checklist questionnaire, which is a score measurement based on the Five Point Likert Scale.

We designed a two-phase data collection to confirm that the ideas we derived from the research review were theoretically correct as they were collected. Phase 1 models were examined by experts in digital finance literacy, such as professors in the Department of Finance and Accounting, Finance academics and professionals, and digital finance experts. A focus group interview was conducted to examine dependent variables, causal variables, observed variables, and the theoretical relationship of each variable. using questions related to variables, including statistical relationships among variables.

The research was designed according to the principle of Theory-Development Design through quantitative methods and SEM-path analysis to correlate whether Digital finance literacy and motivation factors affect skills and digital financial capability (new behavior. The correlation of statistical variables can be used theoretically to explain the correlation of variables to create an explanatory conceptual model. The phenomenon of capability development in digital financial literacy then occurred.

3.3. Measurement and scale

In this study, a survey method was used to understand the digital financial literacy capability of the target group. The tools used by the researchers were adapted from previous papers and research. First, Digital Financial Literacy (DFL) was measured with four items by Refs. [36,75];. Secondly, Motivation factors consisted of attitude (ATT), calculated by three references [30,49,[83], [84]]; self-efficacy (SEF), calculated by three references [41,60,85]; and thirdly, skills (SKI), calculated by three items from Refs. [4,9,86] and finally, digital financial capability (DFC) was measured by three items by Refs. [1,10,74]. A total of 16 observed variables were included (see Table 3). Respondents were asked questions about their level for each item of the criterion, Linkert scale comprised of 1 (strongly disagree) and 5 (strongly agree). This study's proximity of data analysis operates SEM with Path Analysis.

Table 3.

Measuring scale.

| Measuring Scale | Observed variables | Source(S) |

|---|---|---|

| Digital Financial Literacy | DFL1-4 | Angela C. Lyons and Josephine Kass-Hanna (2021), Anna Lo Prete (2022) |

| Attitude | ATT1-3 | Fishbein & Ajzen's Theory (1977), Ng (2012) |

| Self-Efficacy | SEF 1-3 | Bandura (1989), Shen et al.'s (2013) |

| Skills | SKI 1-3 | UNESCO (2018), DigComp (2018) |

| Digital Financial Capability | DFC 1-3 | Johnson & Sherraden, (2007) |

Source: Author Own (2023)

3.4. Data analysis

This study presents information on digital and financial literacy for small entrepreneurs. The OECD Survey of Adult Skills measures proficiency in problem-solving in a technology-rich environment as the level of skills needed to use digital technology, communication tools, and networks to acquire and evaluate information, communicate with others, and perform practical tasks [68]. Accordingly, adults (30–65 years old) are digitally literate if they are at least able to use ICT tools and applications to achieve a goal (e.g., fill in an online form) [86]. In this study, small entrepreneurs' digital finance literacy skills, motivated by attitude and self-efficacy variables, directly affected their digital financial capability in accessing digital financial services. Digital financial skills and capabilities are part of the behavior of small entrepreneurs.

3.5. Ethical approval

The study has been approved by Mahidol University Central Instructional Review Board (MU-CIRB), Certificate of Approval COA No. MU-CIRB 2023/089.0903, date of approval 29 March 2023. Moreover, collect informed permission from participants for the study. To this end, to collect data per research ethics, a formal written request was sent to the chosen university for informed consent. In April 2023, the Google Form implementation, the finalized tool, will be published to the intended preview online.

4. Results

4.1. Demographic

The respondents in this study were small entrepreneurs in the provinces of Thailand (Excluding Bangkok). The province is chosen because it is an area with many small entrepreneurs respectively. We offered 400 questionnaires using Google Forms, which were given to participants via social medias, i.e., Line and Facebook to collect the data. The study was conducted from April to June 2023. Respondents in this study were asked to remain anonymous and provided only initials. This study only has been set up to study variables related to the capability development of small entrepreneurs; This has been provided to meet ethical issue clearance. In addition, the specifics of the respondents are shown in (Table 4).

Table 4.

The demographic of participants that shows all relevant data for the respondents in this study. Small entrepreneurs with small businesses have an average of more than three years of various work experience, mostly in food and beverage sales. The table found that 26.75 % graduated with a bachelor's degree, had an average income of about 20,000–30,000 baht, and used two or more loan applications up to 50.75 %. From this population data Shows that this is a population with a bachelor's degree. and have a moderate level of income There is one or more financial applications. However, the lack of digital financial literacy and sufficient motivation to utilize the various financial services currently available is a significant obstacle.

| Demographic | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 172 | 43.00 |

| Female | 228 | 57.00 | |

| Business Scope | Food and Beverage | 127 | 31.75 |

| Retail | 62 | 15.50 | |

| Service | 90 | 22.50 | |

| Agriculturist | 121 | 30.25 | |

| Business Experience | >3 years | 338 | 84.50 |

| 1–3 years | 160 | 40.00 | |

| <1 year | 37 | 9.25 | |

| Educational Qualification |

Elementary school | 86 | 21.50 |

| Secondary school or diploma | 91 | 22.75 | |

| Bachelor's degree | 107 | 26.75 | |

| Master's degree | 81 | 20.25 | |

| Higher than a master's degree | 35 | 8.75 | |

| Monthly Income | >40,000 baht | 64 | 16.00 |

| 30,000–40,000 baht | 87 | 21.75 | |

| 20,000–30,000 baht | 111 | 27.75 | |

| 10,000–20,000 baht | 62 | 15.50 | |

| >10,000 baht | 76 | 19.00 | |

| Number of Online loan Application | More than 3 applications | 156 | 39.00 |

| 1 or more applications | 203 | 50.75 | |

| Not have | 41 | 10.25 | |

Source: Author Own, 2023

4.2. Results of correlation analysis

Table 5 presents the results of path analysis conducted using the AMOS program to assess the relationship between the dependent and independent variables, examining the Total Effect, Direct Effect, and Indirect Effect, ultimately yielding a validity index. The model's consistency is indicated by the following metrics: Chi-Square = 115.092, df = 71, p = 0.001, CFI = 0.991, TLI = 0.984, RMSEA = 0.039, and RMR = 0.09. These consistency indices align with predefined criteria, with CFI and TLI surpassing 0.95, while RMSEA and RMR remain below 0.05, thus confirming the model's robustness [87]. The analysis concludes that the developed Digital Financial Capability (DFC) model is congruent with the empirical data. Upon closer examination, it becomes evident that the variables Digital Financial Literacy (DFL), attitude, self-efficacy, skills, and DFC collectively account for 80.0 % of the variance in the outcome. Furthermore, all four variables exert a positive influence on DFC, with skills exhibiting the most substantial impact on the outcome, followed by attitude and self-efficacy, respectively. The path analysis reveals that the relationship between DFL and attitude exhibits a stronger statistical association compared to the path between DFL and self-efficacy. This underscores the direct impact of both motivational factors on the development of digital financial knowledge, skills, and capabilities, aligning with the Behavior Adjustment Theory and the I-change Model. These findings are consistent with prior research exploring the interplay of DFL and attitude, as well as DFL and self-efficacy [13,82,88,89], and also underscore the role of skills in shaping the capabilities of small entrepreneurs, which is in harmony with the core research inquiries [18,31,82,84,90,91].

Table 5.

The Standardized Total, Indirect, and Direct Effects variable.

| Dependent variable | ATT | SEF | SKI | DFC | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variable | TE | DE | IE | TE | DE | IE | TE | DE | IE | TE | IE | DE |

| DFL | 0 .928** | 0.928** | – | 0.966** | 0.966** | – | – | 0.810** | 0.810** | – | ||

| ATT | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.374* | 0.374* | – | 0.327** | 0.327** | – |

| SEF | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.608** | 0.608** | – | 0.523** | 0.532** | – |

| SKI | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.875** | – | 0.875** |

| R-square | .933 | .861 | .918 | .766 | ||||||||

| Chi-Square = 115.092, df = 71, p = 0.001, TLI = .984, CFI = .991, NFI = .977 | ||||||||||||

| RMSEA = 0.39, SRMR = 0.09 | ||||||||||||

Source: Author Own 2023

4.3. Model fit

Characteristics of different fit indices Demonstrating of Goodness of fit (GOF) number of sample = N > 250 and number of observation variable 12<m < 30 [92], test results can be seen from the value of Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) < 0.09, and then the model will be considered suitable or appropriate. Then, the Normal Fit Index (NFI) value produces a value between 0 and 1. The closer to 1, the better or following the model built. The SRMR value in Table 5 shows the number 0.09. This value is less than 1.10 or 0.08, so the model is considered appropriate. Next is the NIF value, which shows the number 0.977, which is getting closer to 1, meaning that it can be stated that the model is considered appropriate.

4.4. Hypothesis testing

Structural equation modeling is used to test model hypotheses. The t-statistic was used for bootstrapping and the researchers present all data using a 400-bootstrap sample. As shown in Table 6 and see Fig. 4, the five hypotheses proposed in this study met the criteria with t-values ranging from 3.500 to 20.152 (>1.96) for each relationship.

Table 6.

Hypothesis testing.

| Hypotheses | Relationship | T-value | P-values | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | DFL → ATT | 13.555 | 0.000 | Confirmed |

| H1b | DFL → SEF | 14.387 | 0.000 | Confirmed |

| H2 | ATT → SKI | 3.500 | 0.000 | Confirmed |

| H3 | SEF → SKI | 5.691 | 0.000 | Confirmed |

| H4 | SKI → DFC | 20.152 | 0.000 | Confirmed |

Note(s): DFL = digital financial literacy, ATT = attitude, SEF = self-efficacy, SKI = skills., DFC = digital financial capability.

Source: Authors own (2023)

Fig. 4.

The structural equation model calculations.

Source: Authors own (2023)

4.5. Path analysis

Path coefficients are also used to evaluate the inner model. T-statistics were estimated using a bootstrap resampling procedure. The bootstrap procedure is a non-parametric approach used to estimate the accuracy of the SEM-PLS estimation. Bootstrapping results show the stability of the study. In this study, the data were run using 400 bootstrap samples. As shown in Table 6 and Fig. 4, there are four accepted hypotheses considering the p-value for each relationship is at a value of 0.000 less than 0.05.

5. Discussion

This study employs the KAB theory and the Behavior Change Theory to elucidate the knowledge and behavior related to digital finance among small entrepreneurs. According to the KAB theory, knowledge aligns with fostering a positive attitude. However, this research extends this by including the factor of self-efficacy, which catalyzes the development of new skills and behaviors, contributing to the enhancement of digital financial capability. This aligns with the I-change model, which delineates three stages of behavioral change: pre-motivation or perception, during motivation, and post-motivation or action [24]. These stages collectively foster digital financial literacy, ultimately culminating in new behaviors and digital financial capability among small entrepreneurs.

The study commences with an assessment of current digital finance knowledge among entrepreneurs, combining digital financial education with a positive attitude and self-efficacy to gauge small entrepreneurs’ abilities and their progress in developing digital financial literacy and capability. Motivation emerges as a pivotal factor in encouraging micro-entrepreneurs to accept and recognize the advantages of digital financial knowledge. Furthermore, the results of this study demonstrate that a positive attitude serves as a catalyst for small entrepreneurs to acknowledge the benefits, even when their technological proficiency is limited. A favorable attitude toward digital finance is strongly correlated with attitudes that positively impact digital finance [5,13], fostering experimentation with applications with confidence and an ongoing commitment to enhancing technology usage.

These findings are in alignment with prior research indicating a positive connection between digital literacy and self-efficacy [18,31,39,53]. It is clear that the COVID-19 pandemic has influenced this situation, restricting small entrepreneurs’ options for accessing online credit services. Many providers of online credit services have temporarily closed, leading to increased reliance on applying for loans through applications. However, the application process remains intricate and necessitates robust security measures, considering the sensitivity of personal information.

Consequently, these findings underscore the necessity for motivational factors in cultivating the skills and augmenting the capabilities of small entrepreneurs, particularly the importance of fostering a positive attitude towards skill development. There is a discernible connection between Digital Financial Literacy (DFL) and the motivation factor required by small entrepreneurs. Knowledge exhibits statistical significance through the motivation factor, indicating that the association between knowledge is more robust when mediated by attitude and self-efficacy, as opposed to motivation in isolation. Ultimately, digital financial competence, and by extension, digital financial capability, is an evolving and continuous process.

Given the complexities of applying for online loans and the high security requirements for accessing personal information, this study offers practical guidelines for two main components. First, policy support from the government for small entrepreneurs’ credit, particularly those who have developed knowledge, motivation, and skills. These individuals could be considered for higher credit limits compared to general small entrepreneurs. Second, knowledge dissemination through the organization of motivating courses for small entrepreneur keen on advancing their digital financial literacy. Such initiatives should be accessible through diverse channels, both online and offline. Encouraging small entrepreneurs to recognize the importance and benefits of applying for loans to enhance their businesses is crucial, especially given the complex verification processes and resource requirements associated with online loan applications.

6. Conclusion

The principal aim of this study is to examine the association between behavior change theory in financial contexts and the I-change model, with a particular focus on investigating factors that incentivize the development of small entrepreneurs’ capabilities. This research explores the relationship between digital financial literacy and the competencies of small entrepreneurs and presents several hypotheses, of which four have been substantiated. The findings reveal that digital financial literacy, along with self-efficacy, attitudes, and perceptions, exerts a positive impact on the skills of small entrepreneurs, even when their financial literacy levels are not as high as initially anticipated [7]. Consequently, the enhancement of digital financial literacy and capabilities has seen notable progress [73]. Additionally, the research delves into previously investigated variables such as attitudes toward digital technology and financial attitudes to elucidate the rationale behind the importance of entrepreneurs possessing a favorable attitude toward digital finance. Such attitudes significantly influence the development of entrepreneurial skills [44,89,90]. The section addressing self-efficacy builds upon prior research that emphasizes self-utilization of digital technology and access to digital financial services for managing financial transactions [82]. These factors play a pivotal role in influencing the skills and capabilities of small entrepreneurs as they navigate various complex financial platforms securely [[93], [94]].

The outcomes of this research offer a foundation for stakeholders to place heightened emphasis on enhancing the capabilities of small entrepreneurs in the domain of digital financial literacy. This will underscore the significance of digital financial literacy and small entrepreneur capabilities in the contemporary digital era. It is important to note that the limitations of this study pertain to the exclusivity of variables within the behavior change theory (I-change model), with a primary focus on the main factor [28,54]. Future studies could potentially expand upon this by incorporating additional relevant variables for a more comprehensive analysis.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Wasan Uthaileang: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Resources. Supaporn Kiattisin: Conceptualization, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Contributor Information

Wasan Uthaileang, Email: wasan.uta@student.mahidol.ac.th.

Supaporn Kiattisin, Email: supaporn.kit@mahidol.ac.th.

References

- 1.Cenamor J., Parida V., Wincent J. How entrepreneurial SMEs compete through digital platforms: the roles of digital platform capability, network capability and ambidexterity. J. Bus. Res. 2019;100:196–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.03.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Billari F.C., Favero C.A., Saita F. Online financial and demographic education for workers: experimental evidence from an Italian Pension Fund. J. Bank. Finance. 2023;151 doi: 10.1016/j.jbankfin.2023.106849. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MDES-ONDE-MIL-Survey-2019-ภาพรวมประเทศ.pdf, (n.d.).

- 4.Atkinson A. vol. 75. Oecd; 2017. (Financial Education for MSMEs and Potential Entrepreneurs). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luo Y., Peng Y., Zeng L. Digital financial capability and entrepreneurial performance. Int. Rev. Econ. Finance. 2021;76:55–74. doi: 10.1016/j.iref.2021.05.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aziz A., Naima U. Rethinking digital financial inclusion: evidence from Bangladesh. Technol. Soc. 2021;64 doi: 10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101509. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar P., Pillai R., Kumar N., Tabash M.I. The interplay of skills, digital financial literacy, capability, and autonomy in financial decision making and well-being. Borsa Istanbul Rev. 2023;23:169–183. doi: 10.1016/j.bir.2022.09.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lyons A.C., Kass-Hanna J. A multidimensional approach to defining and measuring financial literacy in the digital age. Routledge Handb. Financ. Lit. 2021:61–76. doi: 10.4324/9781003025221-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andreou P.C., Anyfantaki S. Financial literacy and its influence on internet banking behavior. Eur. Manag. J. 2021;39:658–674. doi: 10.1016/j.emj.2020.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lo Prete A. Digital and financial literacy as determinants of digital payments and personal finance. Econ. Lett. 2022;213 doi: 10.1016/j.econlet.2022.110378. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yue P., Korkmaz A.G., Yin Z., Zhou H. The rise of digital finance: financial inclusion or debt trap? Finance Res. Lett. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2021.102604. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Z., Li A., Bellotti A., Yao X. The profitability of online loans: a competing risks analysis on default and prepayment. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023;306:968–985. doi: 10.1016/j.ejor.2022.08.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azeez N.P.A., Akhtar S.M.J. Digital financial literacy and its determinants: an empirical evidences from rural India. South Asian J. Soc. Stud. Econ. 2021;11:8–22. doi: 10.9734/sajsse/2021/v11i230279. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hilal B., Abdul Rahim N.F., Iranmanesh M. The conceptual framework of SMEs financial success in sultanate of Oman. J. Gov. Integr. 2020;3 doi: 10.15282/jgi.3.2.2020.5307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neumeyer X., Santos S.C., Morris M.H. Overcoming barriers to technology adoption when fostering entrepreneurship among the poor: the role of technology and digital literacy. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2021;68:1605–1618. doi: 10.1109/TEM.2020.2989740. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eniola A.A. The entrepreneur motivation and financing sources. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021;7:1–17. doi: 10.3390/joitmc7010025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wardana L.W., Narmaditya B.S., Wibowo A., Fitriana, Saraswati T.T., Indriani R. Drivers of entrepreneurial intention among economics students in Indonesia. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2021;9:61–74. doi: 10.15678/EBER.2021.090104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farrell L., Fry T.R.L., Risse L. The significance of financial self-efficacy in explaining women's personal finance behaviour. J. Econ. Psychol. 2016;54:85–99. doi: 10.1016/j.joep.2015.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beristain Iraola A., Álvarez Sánchez R. User centered virtual coaching for older adults at home using SMART goal plans and I-change model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2021;18 doi: 10.3390/ijerph18136868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991;50:248–287. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90022-L. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Houlden S., Hodson J., Veletsianos G., Reid D., Thompson-Wagner C. The health belief model: how public health can address the misinformation crisis beyond COVID-19. Public Heal. Pract. 2021;2 doi: 10.1016/j.puhip.2021.100151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prochaska J.O. Flaws in the theory or flaws in the study: a commentary on “The effect of Transtheoretical Model based interventions on smoking cessation,”. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009;68:404–406. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Locke E.A., Latham G.P. Elsevier; 2015. Breaking the Rules: A Historical Overview of Goal-Setting Theory. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moreau M., Gagnon M.P., Boudreau F. Development of a fully automated, web-based, tailored intervention promoting regular physical activity among insufficiently active adults with type 2 diabetes: integrating the i-change model, self-determination theory, and motivational interviewing compon. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2015;4:1–24. doi: 10.2196/resprot.4099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kasten S., Van Osch L., Candel M., De Vries H. The influence of pre-motivational factors on behavior via motivational factors: a test of the I-Change model. BMC Psychol. 2019;7:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s40359-019-0283-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Broekhuizen K., Van Poppel M.N.M., Koppes L.L., Kindt I., Brug J., Van Mechelen W. No significant improvement of cardiovascular disease risk indicators by a lifestyle intervention in people with Familial Hypercholesterolemia compared to usual care: results of a randomised controlled trial. BMC Res. Notes. 2012;5 doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheung K.L., Hors-Fraile S., De Vries H. Elsevier Inc.; 2020. How to Use the Integrated-Change Model to Design Digital Health Programs. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Vries H. An integrated approach for understanding health behavior; the I-change model as an example. Psychol. Behav. Sci. Int. J. 2017;2 doi: 10.19080/pbsij.2017.02.555585. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schrader P.G., Lawless K.A. The knowledge, attitudes, & behaviors approach how to evaluate performance and learning in complex environments. Perform. Improv. 2004;43:8–15. doi: 10.1002/pfi.4140430905. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bettinghaus E.P. Health promotion and the knowledge-attitude-behavior continuum. Prev. Med. 1986;15:475–491. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(86)90025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amagir A., Groot W., van den Brink H.M., Wilschut A. Financial literacy of high school students in The Netherlands: knowledge, attitudes, self-efficacy, and behavior. Int. Rev. Econ. Educ. 2020;34 doi: 10.1016/j.iree.2020.100185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scandurra R., Calero J. How adult skills are configured? Int. J. Educ. Res. 2020;99 doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2019.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allen J., van der Velden R., Helmschrott S., Martin S., Massing N., Rammstedt B., Zabal A., von Davier M., Ferrari A., Wayrynen L., Behr D., Upsing B., Goldhammer F., Schnitzler M., Baumann R., Johannes R., Barkow I., Rölke H., Jars I., Latour T., Plichart P., Jadoul R., Henry C., Wagner M. Platform Development; 2013. Survey of Adult Skills Technical Report Section 1: Assessment and Instrument Design Section 2. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Note G. Digital financial literacy. 2021:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cordray R. 2014. Financial Literacy Annual Report Message from. [Google Scholar]

- 36.21st-Century Readers. OECD; 2021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jannah S.M. Analysis level of digital literacy of digital natives: how the impact on their self-regulated learning? Ekspektra J. Bisnis Dan Manaj. 2019;3:173–185. doi: 10.25139/ekt.v3i2.1756. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hagger M.S., Chatzisarantis N.L.D. Integrating the theory of planned behaviour and self-determination theory in health behaviour: a meta-analysis. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2009;14:275–302. doi: 10.1348/135910708X373959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Vries H., Mesters I., Van De Steeg H., Honing C. The general public's information needs and perceptions regarding hereditary cancer: an application of the Integrated Change Model. Patient Educ. Couns. 2005;56:154–165. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Agnew S., Harrison N. Financial literacy and student attitudes to debt: a cross national study examining the influence of gender on personal finance concepts. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2015;25:122–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2015.04.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Knutsson O., Blåsjö M., Hållsten S., Karlström P. Identifying different registers of digital literacy in virtual learning environments, Internet High. Educ. Next. 2012;15:237–246. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2011.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ting Y.L. Tapping into students' digital literacy and designing negotiated learning to promote learner autonomy, Internet High. Educ. Next. 2015;26:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2015.04.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hilgert M.a., Hogarth J.M., Beverly S.G. Household financial management: the connection between knowledge and behavior, fed. Reserv. Bull. 2003;106:309–322. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Edwards R., Allen M.W., Hayhoe C.R. Financial attitudes and family communication about students' finances: the role of sex differences. Commun. Reports. 2007;20:90–100. doi: 10.1080/08934210701643719. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lilian A. Motivational beliefs, an important contrivance in elevating digital literacy among university students. Heliyon. 2022;8 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e11913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Imd I.M.D. 2022. World Digital Competitiveness Ranking 2022; p. 180.https://www.imd.org/research-knowledge/books/world-competitiveness-yearbook-2020/ [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oggero N., Cristina Rossi M., Ughetto E., di Torino P., Carlo Alberto C. vols. 1–42. Soc. Ital. Degli Econ; 2012. https://siecon3-607788.c.cdn77.org/sites/siecon.org/files/media_wysiwyg/oggero-rossi-ughetto-33.pdf (Entrepreneurial Spirits in Women and Men. The Role of Risk Propensity and Financial Literacy). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tang N. Cognitive abilities, self-efficacy, and financial behavior. J. Econ. Psychol. 2021;87 doi: 10.1016/j.joep.2021.102447. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bernard R.M., Abrami P.C., Lou Y., Borokhovski E., Wade A., Wozney L., Wallet P.A., Fiset M., Huang B. How does distance education compare with classroom instruction? A meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Rev. Educ. Res. 2004;74:379–439. doi: 10.3102/00346543074003379. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Amagir A., Groot W., van den Brink H.M., Wilschut A. Financial literacy of high school students in The Netherlands: knowledge, attitudes, self-efficacy, and behavior. Int. Rev. Econ. Educ. 2020;34 doi: 10.1016/j.iree.2020.100185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chong K.F., Sabri M.F., Magli A.S., Rahim H.A., Mokhtar N., Othman M.A. The effects of financial literacy, self-efficacy and self-coping on financial behavior of emerging adults. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2021;8:905–915. doi: 10.13106/jafeb.2021.vol8.no3.0905. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rai K., Dua S., Yadav M. Association of financial attitude, financial behaviour and financial knowledge towards financial literacy: a structural equation modeling approach. FIIB Bus. Rev. 2019;8:51–60. doi: 10.1177/2319714519826651. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Senkbeil M., Ihme J.M. Motivational factors predicting ICT literacy: first evidence on the structure of an ICT motivation inventory. Comput. Educ. 2017;108:145–158. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2017.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Andreou P.C., Anyfantaki S. Financial literacy and its influence on internet banking behavior. Eur. Manag. J. 2021;39:658–674. doi: 10.1016/j.emj.2020.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bandura A. The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1986;4:359–373. doi: 10.1521/jscp.1986.4.3.359. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bandura A. 1994. Social Cognitive Theory and Exercise of Control over HIV Infection; pp. 25–59. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Geller K., Lippke S., Nigg C.R. Future directions of multiple behavior change research. J. Behav. Med. 2017;40:194–202. doi: 10.1007/s10865-016-9809-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kuhnen C.M., Melzer B.T. Noncognitive abilities and financial delinquency: the role of self-efficacy in avoiding financial distress. J. Finance. 2018;73:2837–2869. doi: 10.1111/jofi.12724. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Asebedo S., Payne P. Market volatility and financial satisfaction: the role of financial self-efficacy. J. Behav. Financ. 2019;20:42–52. doi: 10.1080/15427560.2018.1434655. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.OECD . 2017. G20/OECG INFE Report on Adult Financial Literacy in G20 Countries; pp. 1–80. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Valaskova K., Bartosova V., Kubala P. Behavioural aspects of the financial decision-making. Organizacija. 2019;52:22–31. doi: 10.2478/orga-2019-0003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cole S., Paulson A., Shastry G.K. Smart money? the effect of education on financial outcomes. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2014;27:2022–2051. doi: 10.1093/rfs/hhu012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nabavi R.T. Univ. Sci. Cult.; 2012. Theories of Developmental Psychology: Bandura ’ S Social Learning Theory & Social Cognitive Learning Theory; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mutegi H.K., Njeru P.W., Ongesa N.T. Financial literacy and its impact on loan repayment by small and medium enterprenuers: an analysis of the effect of book keeping skills from equity group foundation's financial literacy training program on enterpreneurs' loan repayment performance. Int. J. Econ. Commer. Manag. 2015;3:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rey-Ares L., Fernández-López S., Castro-González S., Rodeiro-Pazos D. Does self-control constitute a driver of millennials' financial behaviors and attitudes? J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 2021;93 doi: 10.1016/j.socec.2021.101702. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tomar S., Kent Baker H., Kumar S., Hoffmann A.O.I. Psychological determinants of retirement financial planning behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2021;133:432–449. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xu B., Li S., Afzal A., Mirza N., Zhang M. The impact of financial development on environmental sustainability: a European perspective. Resour. Policy. 2022;78 doi: 10.1016/j.resourpol.2022.102814. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.OECD/INFE . 2019. OECD/INFE Report on Financial Education in APEC Economies. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kass-Hanna J., Lyons A.C., Liu F. Building financial resilience through financial and digital literacy in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.ememar.2021.100846. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lusardi A. Financial literacy and the need for financial education: evidence and implications. Swiss J. Econ. Stat. 2019;155:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s41937-019-0027-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zulaihati S., Susanti S., Widyastuti U. Teachers' financial literacy: does it impact on financial behaviour? Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020;10:653–658. doi: 10.5267/j.msl.2019.9.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hoelzl E., Kapteyn A. Financial capability. J. Econ. Psychol. 2011;32:543–545. doi: 10.1016/j.joep.2011.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Luo Y., Zeng L. Digital financial capabilities and household entrepreneurship. Econ. Polit. Stud. 2020;8:165–202. doi: 10.1080/20954816.2020.1736373. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lyons A.C., Kass‐Hanna J. A methodological overview to defining and measuring “digital” financial literacy. Financ. Plan. Rev. 2021;4:1–19. doi: 10.1002/cfp2.1113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Noh Y. A study on the effect of digital literacy on information use behavior. J. Librariansh. Inf. Sci. 2017;49:26–56. doi: 10.1177/0961000615624527. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lyons A., Kass-Hanna J. A methodological overview to defining and measuring “digital” financial literacy. SSRN Electron. J. 2021;1 0–27. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Akinnuwesi B.A., Uzoka F.E., Fashoto S.G., Mbunge E., Odumabo A., Amusa O.O., Okpeku M., Owolabi O. A modified UTAUT model for the acceptance and use of digital technology for tackling COVID-19. Sustain. Oper. Comput. 2022;3:118–135. doi: 10.1016/j.susoc.2021.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Eastin M.S., LaRose R. Internet self-efficacy and the psychology of the digital divide. J. Comput. Commun. 2000;6 doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2000.tb00110.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Brennan C., O'Donoghue G., Hall A.M., Keogh A., Matthews J. A systematic review of the intervention characteristics, and behavior change theory and techniques used in mother-daughter interventions targeting physical activity. Prev. Med. 2021;153 doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sinaise M.K., Tran A., Johnson H.M., Vedder L.S., Hoppe K.K., Lauver D. Concepts from behavioral theories can guide clinicians in coaching for behavior change. Patient Educ. Couns. 2023;106:188–193. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2022.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hazra A., Ahmad J., Mohanan P.S., Supriya, Verma R.K., Sridharan S. Testing theory of change assumptions of health behavior change interventions: a blended approach exploring local contexts. Eval. Progr. Plann. 2023;98 doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2023.102258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Prior D.D., Mazanov J., Meacheam D., Heaslip G., Hanson J. Attitude, digital literacy and self efficacy: flow-on effects for online learning behavior, Internet High. Educ. Next. 2016;29:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2016.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Potrich A.C.G., Vieira K.M., Coronel D.A., Bender Filho R. Financial literacy in Southern Brazil: modeling and invariance between genders. J. Behav. Exp. Financ. 2015;6:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jbef.2015.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wamuyu P.K. Bridging the digital divide among low income urban communities. Leveraging use of Community Technology Centers, Telemat. Informatics. 2017;34:1709–1720. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2017.08.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tang N. Cognitive abilities, self-efficacy, and financial behavior. J. Econ. Psychol. 2021;87 doi: 10.1016/j.joep.2021.102447. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yu T.K., Lin M.L., Liao Y.K. Understanding factors influencing information communication technology adoption behavior: the moderators of information literacy and digital skills. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017;71:196–208. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Schumacker R.E., Lomax R.G. 2015. A Beginner's Guide to Structural Equation Modeling. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wardana L.W., Ahmad, Indrawati A., Maula F.I., Mahendra A.M., Fatihin M.K., Rahma A., Nafisa A.F., Putri A.A., Narmaditya B.S. Do digital literacy and business sustainability matter for creative economy? The role of entrepreneurial attitude. Heliyon. 2023;9 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e12763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Allagui B. Factors underlying students' attitudes towards multimodal collaborative writing. Heliyon. 2023;9 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e12725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Jeon J., Kim S. The mediating effects of digital literacy and self-efficacy on the relationship between learning attitudes and Ehealth literacy in nursing students: a cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ. Today. 2022;113 doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2022.105378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Liu L., Zhang H. Financial literacy, self-efficacy and risky credit behavior among college students: evidence from online consumer credit. J. Behav. Exp. Financ. 2021;32 doi: 10.1016/j.jbef.2021.100569. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hair J.F., Anderson R.E., Tatham R.L., Black W.C. Multivariate data analysis, multivariate data analysis. Book. 2019;87:611–628. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bejaković P., Mrnjavac Ž. The importance of digital literacy on the labour market. Employee Relat. 2020;42:921–932. doi: 10.1108/ER-07-2019-0274. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ramalho T.B., Forte D. Financial literacy in Brazil – do knowledge and self-confidence relate with behavior? RAUSP Manag. J. 2019;54:77–95. doi: 10.1108/RAUSP-04-2018-0008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]