Abstract

Background

Hepatic stellate cells (HSC) are the key mediators of fibrosis development in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Hepatic inflammation induced by high-fat diet activates HSCs, which differentiate to myofibroblasts and produce extracellular fibrillar matrix. HSC activation during hepatic fibrogenesis is modulated by cytokines and growth factors produced by stressed hepatocytes and macrophages. SOCS1 is a negative feedback regulator of certain cytokines and growth factors implicated in liver fibrosis.

Aim

The goal of this study was to understand the regulatory functions of SOCS1 in HSCs during NAFLD-induced liver fibrosis.

Methodology

Mice lacking SOCS1 specifically in HSCs (Socs1ΔHSC) and control Socs1-floxed (Socs1fl/fl) mice were fed choline-deficient L-amino acid-defined high-fat diet (CDA-HFD) or normal control diet for 14 weeks. Body weight gain was regularly monitored. Serum alanine aminotransferase levels and liver weight were assessed at the endpoint. Fibrosis development was evaluated by Sirius red staining and hydroxyproline content, and myofibroblast differentiation by immunohistochemistry. Expression of genes encoding pro-fibrogenic factors, cytokines, growth factors and chemokines, and the phenotype and numbers of intrahepatic leukocytes were evaluated.

Results

Socs1ΔHSC mice showed increased liver/body weight ratio and displayed increased collagen deposition and myofibroblast differentiation. Induction of Acta2, Col1a1, Pdgfb, IL1b and Ccl2 genes was significantly elevated in Socs1ΔHSC mice compared to Socs1fl/fl controls fed CDA-HFD. Tgfb gene induction was comparable between the two groups, however, Socs1ΔHSC livers displayed increased SMAD3 phosphorylation. The fibrotic livers of Socs1ΔHSC mice showed increased inflammatory cell infiltration, and flow cytometry analysis revealed elevated numbers of myeloid cells, granulocytes and myeloid-derived dendritic cells. Socs1ΔHSC livers harbored increased numbers of Ly6ChiCCR2+ pro-inflammatory macrophages, largely comprised of Ly6ChiCCR2+CX3CR1+ cells, suggesting impaired transition to anti-inflammatory macrophages.

Conclusion

Our findings show that SOCS1 exerts non-redundant regulatory functions in HSCs that are critical for attenuating high-fat diet-induced inflammatory response and liver fibrosis development.

Keywords: NAFLD, liver fibrosis, CDA-HFD, hepatic stellate cells, SOCS1

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a chronic inflammatory condition of the liver resulting from obesity and metabolic syndrome.1,2 The prevalence of NAFLD has been steadily increasing over the past three decades and has become an important healthcare and socioeconomic burden in developed and developing nations.3 Without lifestyle, nutritional and medical interventions, NAFLD can progress towards non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), fibrosis and cirrhosis. The clinical outcome of NAFLD is largely determined by the degree of fibrosis, which increases the risk of mortality.4 Liver fibrosis associated with NAFLD also promotes the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), a major cause of cancer-related mortality.5 While dietary and pharmacological interventions are used to treat NAFLD, restraining the progression towards fibrosis and HCC requires development of strategies for non-invasive detection of early fibrosis and to restrain the hepatic fibrogenic response.6,7

In NAFLD, fat accumulation and oxidative stress cause hepatocyte damage, resulting in the activation of liver-resident Kupffer cells and hepatic stellate cells (HSC) to initiate an inflammatory response that is further amplified by recruited inflammatory cells, leading to NASH.2,8, 9, 10 Cytokines and growth factors released by stressed hepatocytes and activated macrophages promote HSC activation, cell proliferation, myofibroblast differentiation and induction of fibrogenic genes and production of extracellular matrix (ECM) components such as collagens. These events, intended to repair the damage tissue, become chronic and result in the accumulation of abnormal ECM, fibrosis development and its progression towards cirrhosis. Efforts to control activated HSCs and retard fibrosis progression in NAFLD has not yet been successful.9,10 These efforts can be strengthened by understanding the molecular mechanisms that regulate HSC activation during obesity-associated fibrosis development and identification of new actionable molecular targets.

HSC activation and survival are modulated by cytokines and growth factors.9, 10, 11, 12 Indeed, targeting cytokines, chemokines and growth factors that promote HSC activation is a key strategy for therapeutic intervention of liver fibrosis.13 Suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 (SOCS1), which is induced by diverse cytokines and growth factors, is an endogenous negative feedback regulator of cytokine-induced Janus kinase signaling and growth factor-induced receptor tyrosine kinase signaling pathways in various types of immune and parenchymal cells.14,15 SOCS1 expression in myeloid cells has been shown to confer protection in mice against inflammation and hepatic insulin resistance via inhibiting LPS and palmitate-induced TLR4 signaling in macrophages and restraining the production of IL-6, TNFα and CCL2.16 In human patients with chronic liver disease, low SOCS1 expression correlates with increased fibrosis.17 We have previously shown that SOCS1-deficient mice are highly susceptible to CCl4-induced liver fibrosis and that SOCS1 attenuates cytokine responses in macrophages during hepatic fibrogenic response.18,19 In the current study, we ablated the Socs1 gene specifically in HSCs and examined liver fibrosis induction by choline-deficient L-amino acid-defined high-fat diet (CDA-HFD)20 to understand the regulatory functions of SOCS1 in HSCs during diet-induced liver fibrosis.

Materials and methods

Mouse Strains

The Socs1fl/fl mouse strain backcrossed to C57BL/6 mice for more than ten generations has been previously described.19 Mice lacking SOCS1 expression in HSCs (Socs1ΔHSC) were generated by crossing Socs1fl/fl mice with LratCre mice obtained from Dr. C. Österreicher (University of Vienna).21 LratCre mice express the Cre recombinase under the promoter of lecithin retinol acytransferase (LART), which is expressed only in HSCs and not in hepatocytes, cholangiocytes or endothelial cells of the liver.21,22 Only female LratCre mice were used for breeding as the Lrat promoter is expressed in spermatozoa. Mice were housed in specific pathogen-free conditions with 12 h day/night cycle. All experiments were carried out with the approval of the Université de Sherbrooke Ethics Committee for Animal Care and Use (Protocol ID: 2018-2083).

Induction of Liver Fibrosis

To model liver fibrosis associated with fatty liver, 6-week-old mice were fed ad libitum CDA-HFD (Cat # A06071302; 60% energy from fat and 0.1% methionine), or the corresponding normal control diet (NCD; Cat #D11112201; 15% energy from fat), purchased from Research Diets (New Brunswick, NJ, USA). The CDA-HFD rapidly induces progressive liver fibrosis.20 After 14 weeks of CDA-HFD or NCD regimen, mice were euthanized, and serum and liver tissues collected.

Measurement of Serum ALT and Liver Hydroxyproline Content

A kinetic assay kit from Pointe Scientific Inc. (Brussels, Belgium) was used to measure serum alanine transaminase (ALT) levels following manufacturer's instructions. Collagen content in liver homogenates was quantified by measuring hydoxyproline levels, as previously described.18

Histology

Liver tissues fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight were paraffin embedded following standard methods. Formalin-fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) liver sections (5 μm) were stained with Sirius red or hematoxylin and eosin as previously described.18 A NanoZoomer Digital Pathology (NDP) slide scanner was used to acquire digital images of stained sections. Images were analyzed using the NDP.view2 software (Hamamatsu Photonics, Japan). The Image J software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) was used to quantify Sirius red staining areas. Twenty randomly selected fields from three to five mice in each group were used for quantification.

Immunohistochemistry

Myofibroblasts were identified by immunohistochemical (IHC) staining of alpha smooth muscle actin (αSMA) in liver sections as previously described.18 Deparaffinized tissue sections were blocked with 5% BSA in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 20% Tween-20 (TBS-T) and then incubated with αSMA antibody (Abcam; #ab7817) at 4 °C overnight before applying horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary Ab for 1 h and developed with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Sigma–Aldrich). The sections were counterstained with hematoxylin and mounted with a coverslip. Digital images of the stained sections were acquired using a Nanozoomer Slide Scanner and analyzed by the Nanozoomer Digital Pathology software (Hamamatsu Photonics, Japan). The ImageJ software was used to quantify αSMA staining intensity.

Gene Expression Analysis

RNA extracted from liver tissues were processed for cDNA preparation and gene expression analysis by RT-qPCR as previously described.18 All RT-qPCR primers (Table 1) showed a single melting curve with more than 90% efficiency. Expression levels of the housekeeping gene Rplp0 (36B4) was used to normalize the expression levels of specific genes within each experimental group. Fold induction of specific mRNA in mice fed CDA-HFD diet was calculated by comparing to Socs1fl/fl littermate controls fed NCD.

Table 1.

List of RT-qPCR Primers Used in this Study.

| Gene name | Gene ID | Sense primer | Anti-sense primer | Amplicon Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acta2 | NM_007392.3 | AGTAATGGTTGGAATGG | GTGTCGGATGCTCTTCAGG | 146 |

| Ccl2 | NM_011333.3 | CAGGTCCCTGTCATGCTTCT | GTGGGGCATTAACTGCAT | 144 |

| Ccl5 | NM_013653.3 | TGCAGAGGACTCTGAGACAGC | GAGTGGTGTCCGAGCCATA | 129 |

| Col1a1 | NM_007742.4 | CTCCCAGAACATCACCTATCAC | ACTGTCTTGCCCCAAGTTCCG | 150 |

| Cx3cl1 | NM_009142.3 | TCTTCCATTTGTGTACTCTGCT | GGACTCCTGGTTTAGCTGATAG | 128 |

| Il1b | NM_008361.4 | TCCTGTGTAATGAAAGACGGC | ACTCCACTTTGCTCTTGACTTC | 139 |

| Il6 | NM_031168.2 | AGTCCGGAGAGGAGACTTCA | TTGCCATTGCACAACTCTTT | 150 |

| Mmp2 | NM_008610.3 | CAAGTTCCCCGGCGATGTC | TTCTGGTCAAGGTCACCTGTC | 91 |

| Pdgfb | NM_011057.4 | CCTGCAAGTGTGAGACAGTAG | CTTTCGGTGCTTGCCTTTG | 146 |

| Timp1 | NM_011593.2 | TTGCATCTCTGGCATCTGG | TGGTCTCGTTGATTTCTGGG | 136 |

| Tgfb1 | NM_011577.2 | ATACGCCTGAGTGGCTGTCT | CTGATCCCGTTGATTTCCA | 124 |

| 36B4 (Rplp0) | NM_007475.5 | TCTGGAGGGTGTCCGCAA | CTTGACCTTTTCAGTAAGTGG | 148 |

Western blot

Proteins were extracted from snap frozen liver tissue samples using a bead mill (MM400; Retsch, Hann, Germany) tissue homogenizer and protein concentration estimated as previously described.18 Thirty μg of total proteins were separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gels, transferred to PVDF membrane and immunoblotted using primary antibodies from Cell Signaling Technology: α-SMA (# 19245 S), β-actin (# 4970 S), Phospho-ERK1/2 (# 4377), ERK1/2 (#9102), phospho-SMAD2 (# 3108 L), SMAD2 (# 3103 S), phospho-SMAD3 (#9520 S), SMAD3 (# 9513 S); SantaCruz Biotechnology: MMP2 (sc-13595), TIMP1 (sc-21734); SOCS3 (sc-73045); or Abcam: Collagen 1 (#15200). The protein bands were revealed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies and enhanced chemiluminescence reagents from GE Healthcare Life Sciences (Pittsburg, PA). The VersaDOC 5000 imaging system (Bio-Rad) was used to capture the western blot images.

Isolation of Intrahepatic Leukocytes (IHLs) and Flow Cytometry

IHLs were isolated using a four-step protocol optimized to enrich IHLs from fatty and fibrotic livers.23 Briefly, after collagenase digestion of the liver tissue using the GentleMACS tissue dissociator (Miltenyi Biotech), IHLs were separated from hepatocytes by differential centrifugation, fatty debris was removed by Percoll density gradient centrifugation, and hematopoietic cells were enriched using anti-CD45 magnetic beads and resuspended in PBS containing 2% fetal bovine serum. Aliquots of IHLs were stained for flow cytometry analysis using two panels of fluorochrome conjugated antibodies (Table 2) to characterize myeloid and lymphoid cells as previously described.23 The CytoFlex flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter) was used for data acquisition that was analyzed using the FlowJo software (BD Biosciences).

Table 2.

Antibodies Used for Flow Cytometry.

| Antibody | Fluorochrome | Source | Clone | #Cat. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A) Myeloid cell panel | ||||

| Viability Dye | e-fluor 780 | ebiosciences | 65–0865 | |

| CD45 | Brillian Violet 510 | Biolegend | 30-F11 | 103138 |

| CD11b | eFluor450 | ebiosciences | M1/70 | 100353 |

| Ly6G | Peridinin-Chlorophyll-Protein (PerCP) | Biolegend | 1A8 | 127654 |

| Ly6C | Fluorescein isothiocyante (FITC) | eBiosciences | HK1.4 | 53-5932-82 |

| CD11c | Alexa Fluor 700 | ebiosciences | N418 | 5016869 |

| CCR2 | Phycoerythrin (PE) | R&D Systems | 475301 | FAB5538P |

| CX3CR1 |

Allophycocyanin (APC) |

Biolegend |

SA011F11 |

149008 |

|

B) Lymphoid cell panel | ||||

| CD45 | Brilliant Violet 605 | Biolegend | 30-F11 | 103140 |

| CD3ε | Brilliant Violet 510 | Biolegend | 145-2C11 | 100353 |

| TCRβ | PE/Dazzle594 | Biolegend | 109240 | H57-597 |

| CD4 | Alexa Fluor 700 | ebiosciences | GK1.5 | 5016851 |

| CD8α | eFluor450 | ebiosciences | 53–6.7 | 48-0081-82 |

| CD62L | APC | ebiosciences | MEL-14 | 17-0621-83 |

| CD44 | FITC | Biolegend | IM7 | 103006 |

| CD69 | PE-Cy7 | Biolegend | H1.2F3 | 104512 |

| NK1.1 | APC-Cy7 | Biolegend | PK136 | 108724 |

| GalCer:CD1d | PE | Biolegend | L363 | 140506 |

Statistical Analyses

The data were analyzed using Prism V9.3.1 software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA) to plot graphs and to calculate statistical significance. p values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

SOCS1 Deficiency in HSCs Promotes Liver Fibrosis Induced by CDA-HFD

HSCs are key drivers of liver fibrosis that respond to fibrogenic cytokines and growth factors produced by inflammatory macrophages while SOCS1 is a potential regulator of some of these fibrosis-promoting mediators.9, 10, 11, 12 Therefore, we studied the regulatory functions of SOCS1 in HSCs during liver fibrosis induced by CDA-HFD using HSC-specific SOCS1-deficient mice. Provision of CDA-HFD ad libitum for 14 weeks from 6 weeks of age caused a steady increase in body weight in both Socs1ΔHSC and Socs1fl/fl control mice (Figure 1A). Even though the body weight gain was appreciably lower in Socs1ΔHSC mice than in Socs1fl/fl controls, this difference was not statistically significant. However, CDA-HFD increased the liver to body weight ratio more significantly in Socs1ΔHSC mice than in Socs1fl/fl control mice (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

SOCS1 expression in HSCs attenuates the severity of liver fibrosis induced by CDA-HFD. Six weeks old male Socs1ΔHSC and sex matched Socs1fl/fl littermate controls were fed ad libitum choline-deficient L-amino acid-defined high-fat diet (CDA-HFD) or normal control diet (NCD) for fourteen weeks to induce obesity and NAFLD. (A) Body weight was measured twice a week to evaluate body weight gain. Mean ± standard error of mean (SE) from five to eight mice per group from two independent experiments are shown. (B) Liver weight was measured at the endpoint and liver to body weight ratio was calculated. (C) Serum ALT levels (mean ± SE). (D) Sirius red staining of liver sections from the indicated groups of mice. Representative data from three mice for each group are shown. (E) Quantification of Sirius red staining areas. (F) Hydroxyproline content of liver tissues. Mean ± SE from six to eight mice per group from two independent experiments. Statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparison test. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001.

Serum ALT levels were equally elevated in CDA-HFD-fed Socs1ΔHSC and Socs1fl/fl mice compared to corresponding NCD-fed control groups (Figure 1C), indicating that SOCS1 expression in HSCs does not impact hepatocyte damage induced by high-fat diet. Evaluation of liver fibrosis by Sirius red staining of collagen fibers in FFPE sections revealed a marked increase in staining in both Socs1ΔHSC and Socs1fl/fl mice on CDA-HFD regimen compared to NCD-fed groups (Figure 1D). Quantification of the Sirius red stained areas revealed a more significant increase in Socs1ΔHSC mice than in Socs1fl/fl mice (Figure 1E), indicating increased liver fibrosis in the absence of SOCS1 in HSCs. This notion is further supported by significantly increased hydroxyproline content in the fibrotic livers of Socs1ΔHSC mice compared to Socs1fl/fl mice fed CDA-HFD (Figure 1F). These data indicated that SOCS1 expression in HSCs is critical to attenuate liver fibrosis induced by high-fat diet.

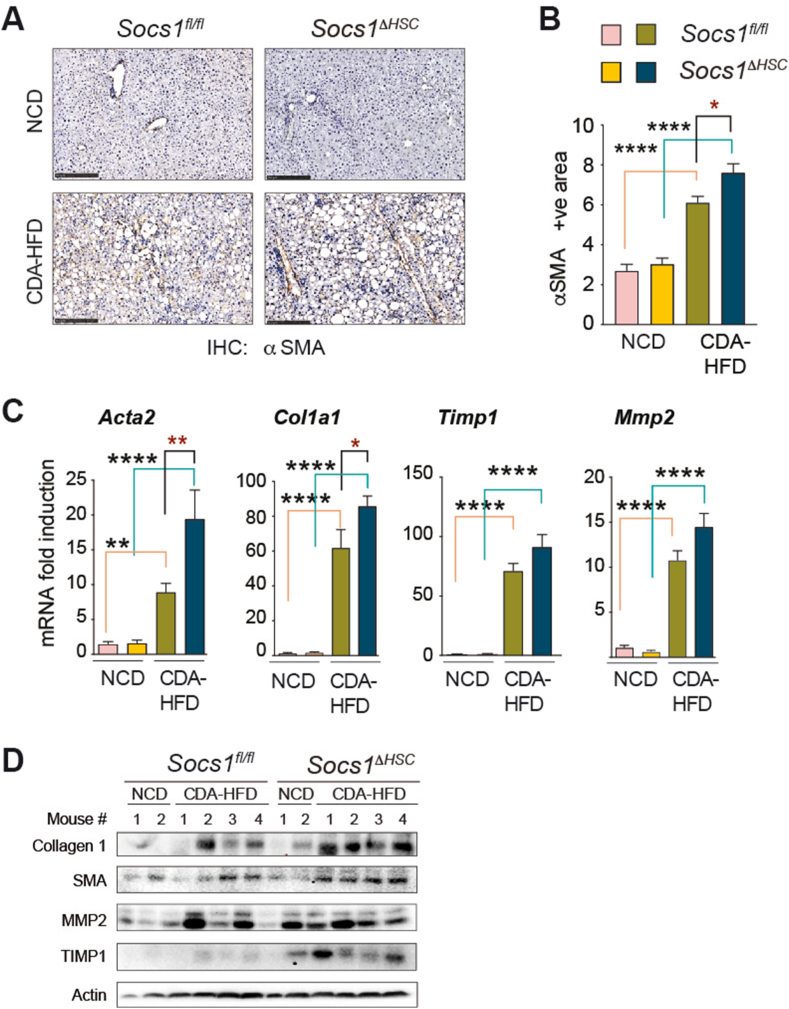

SOCS1 in HSCs Regulates Myofibroblast Activation During CDA-HFD-induced Liver Fibrosis

Next, we evaluated the effect of SOCS1 deficiency in HSCs on myofibroblast differentiation by immunohistochemical staining of αSMA in the fibrotic livers. As shown in Figure 2A, Socs1ΔHSC mice fed CDA-HFD showed appreciably increased αSMA staining compared to Socs1fl/fl mice and this increase was found to be significant by quantification of the staining area (Figure 2B). The fibrotic livers of mice fed CDA-HFD showed a significant increase in the expression of Acta2 and Col1a1 genes coding for αSMA and collagen 1, and this increase was significantly higher in Socs1ΔHSC mice than in Socs1fl/fl mice (Figure 2C). In agreement, expression of αSMA and collagen 1 proteins was discernibly increased in the fibrotic livers of Socs1ΔHSC mice (Figure 2D). CDA-HFD-induced liver fibrosis was associated with elevated expression of the antifibrotic matrix metalloproteinase 2 (Mmp2) and tissue inhibitor of MMPs 1 (Timp1) genes in both Socs1ΔHSC and Socs1fl/fl mice (Figure 2C). Evaluation of protein expression revealed similar increase in MMP2 in both groups of CDA-HFD-fed mice, although the expression of TIMP1 was noticeably increased in Socs1ΔHSC mice (Figure 2D). These findings indicated that SOCS1 expression in HSCs is critical to restrain HSC activation and myofibroblast differentiation induced by high-fat diet.

Figure 2.

Increased myofibroblast activation and ECM production in the fibrotic livers of Socs1ΔHSCmice. (A) IHC staining of αSMA in liver sections from Socs1ΔHSC and Socs1fl/fl control mice. Data shown are representative of four mice in each group. (B) Quantification of the αSMA staining area. Mean ± SE from three (NCD group) or four (CDA-HFD group) mice from two experiments. (C) RT-qPCR evaluation of the expression of Acta1, Col1a1, Mmp2 and Timp1 genes associated with hepatic fibrogenic response in four CDA-HFD and two NCD-fed groups of mice. n = 6–8 mice per group from two independent experiments. (D) Western blot evaluation of collagen 1 and αSMA proteins in the liver tissues of four CDA-HFD-fed and two NCD-fed Socs1ΔHSC and Socs1fl/fl mice. β-actin was used as a loading control.

Increased Fibrogenic Cytokine Production and Signaling in Socs1ΔHSC Mice fed CDA-HFD

HSC activation and myofibroblast differentiation is driven by cytokines and growth factors, especially TGFβ and PDGFB, which are key inducers of fibrogenic genes and myofibroblast proliferation, respectively.24,25 Tgfb gene expression is significantly induced by CDA-HFD in Socs1ΔHSC and Socs1fl/fl mice to a similar extent (Figure 3A). Evaluation of the SMAD phosphorylation, which occurs downstream of TGFβ signaling, revealed that CDA-HFD-induced SMAD2 phosphorylation was comparable Socs1ΔHSC and Socs1fl/fl mice, however SMAD3 phosphorylation was appreciably increased in Socs1ΔHSC mice (Figure 3B). The Pdgfb gene coding for PDGFB is only modestly increased in Socs1fl/fl mice fed CDA-HFD but is significantly upregulated in Socs1ΔHSC mice (Figure 3A). Phosphorylation ERK1/2, which occurs downstream of growth factor receptor tyrosine kinases, was consistently increased in Socs1ΔHSC mice (Figure 3B). Among the genes coding for the proinflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-1β, Il6 is only modestly elevated whereas Il1b is significantly induced by CDA-HFD and to a significantly higher level in Socs1ΔHSC mice than in Socs1fl/fl mice (Figure 3A). SOCS3, which is a key regulator of IL-6 signaling,26 was upregulated in the liver of Socs1ΔHSC mice fed CDA-HFD (Figure 3B). These data indicated that SOCS1 expression in HSCs plays a crucial role in regulating fibrogenic gene induction by high-fat diet.

Figure 3.

Increased PDGFB expression and TGFβ signaling in the fibrotic livers of CDA-HFD-fed Socs1ΔHSCmice. (A) RT-qPCR evaluation of the expression of key fibrogenic (Tgfb), growth factor (Pdgfb) inflammatory cytokine (Il6, IL1b) genes in the livers of the indicated groups of mice. Mean ± SE of data from 6 to 8 mice per group from two independent experiments. One-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparison test. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001. (B) Western blot evaluation of phosphorylated and total SMAD2, SMAD3 and ERK1/2 proteins and SOCS3 expression in the liver tissues of four CDA-HFD-fed and two NCD-fed Socs1ΔHSC and Socs1fl/fl mice.

SOCS1 in HSCs Controls Inflammatory Cell Infiltration in Liver Fibrosis Induced by CDA-HFD

Hepatic inflammation induced by high-fat diet is initiated by liver resident macrophages and HSCs and perpetuated by infiltrating inflammatory cells.8, 9, 10,27 Comparison of hematoxylin and eosin-stained liver sections revealed increased inflammatory cell infiltration in Socs1ΔHSC mice compared to Socs1fl/fl controls fed CDA-HFD (Figure 4A), indicating that SOCS1 expression in HSCs is crucial to control hepatic inflammatory response induced by high-fat diet. In support of this idea, the Ccl2 chemokine gene that encodes macrophage chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1/CCL2) was strongly induced by high-fat diet in Socs1fl/fl mice and this increase was further augmented by SOCS1 deficiency in HSCs (Figure 4B). On the other hand, the Ccl5 (RANTES) and Cx3cl1 (Fractalkine) genes were similarly upregulated by CDA-HFD in Socs1ΔHSC and Socs1fl/fl mice livers (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

SOCS1 deficiency in HSCs increases inflammatory cell infiltration following fibrosis induction by CDA-HFD. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin-stained liver sections of Socs1fl/fl and Socs1ΔHSC mice fed NCD or CDA-HFD. Representative images from three to four mice per group are shown. A higher magnification images of livers from fed mice are shown in right panels. (B) RT-qPCR evaluation of Ccl2, Ccl5 and Cx3cl1 chemokine gene expression in the livers of indicated groups. Mean ± SE from 6 to 8 mice per group from two independent experiments. One-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparison test. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001.

Accumulation of Inflammatory Macrophages During CDA-HFD-induced Liver Fibrosis in Mice Lacking SOCS1 in HSCs

MCP1/CCL2 is strongly chemotactic for monocytes and granulocytes to inflammatory sites. Therefore, we compared the myeloid cell populations in the livers of Socs1ΔHSC and Socs1fl/fl mice on CDA-HFD or NCD regimen by flow cytometry analysis of intrahepatic leukocytes, using a recently established protocol for IHL isolation and cell phenotype analysis.23 CDA-HFD regimen elicited a strong influx of CD45+CD11b+ myeloid cells and CD11b+Ly6G+ granulocytes. This inflammatory cell infiltration was significantly increased in Socs1ΔHSC mice with respect to Socs1fl/fl controls (Figure 5A). The number of CD11b+CD11c+ myeloid dendritic cells (DC) was also significantly enhanced in the fibrotic livers of Socs1ΔHSC mice on CDA-HFD regimen, whereas the increase in the number of plasmacytoid DCs were comparable between Socs1ΔHSC and Socs1fl/fl mice (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Loss of SOCS1 HSCs promotes accumulation of inflammatory macrophages during CDA-HFD-induced liver fibrosis. Intrahepatic leukocytes isolated from the indicated groups of mice were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies indicated in Table 2A to characterize myeloid cell populations by flow cytometry. The number of cells within specific populations were calculated from their relative proportion, total cell yield and the liver weight. (A) The numbers of CD11b+Ly6G− myeloid cells and CD11b+Ly6G+ granulocytes within CD45+ gated hematopoietic cells. (B) The numbers of CD11b+CD11c+ myeloid DCs and CD11bloCD11c+ plasmacytoid dendritic cells. (C) Numbers of Ly6ChiCCR2+ pro-inflammatory, Ly6CloCX3CR1+ anti-inflammatory and Ly6ChiCCR2+CX3CR1+ intermediate macrophages within the CD11b+Ly6G− myeloid cell gate. Pooled data from four to seven mice per group are shown (mean ± SE). One-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparison test. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001.

Next, we segregated the macrophage population within the CD45+CD11b+Ly6G− gate based on the expression of Ly6C and CCR2, the key markers of inflammatory macrophages.28 The fibrotic livers of both Socs1ΔHSC and Socs1fl/fl mice harbored increased numbers of Ly6ChiCCR2+ pro-inflammatory macrophages, and the abundance of these cells was significantly elevated in the livers of mice lacking SOCS1 in HSCs (Figure 5C). Pro-inflammatory macrophages become anti-inflammatory macrophages that promote fibrosis resolution and tissue regeneration,28 a transition that is accompanied by downregulation of Ly6C and upregulation CX3CR1. The fibrotic livers of mice on CDA-HFD regimen also contained increased numbers of Ly6CloCX3CR1+ pro-resolution macrophages but this increase was comparable between Socs1fl/fl and Socs1ΔHSC mice (Figure 5D). Our analysis revealed that the number of Ly6ChiCCR2+ cells also expressing CX3CR1 was markedly upregulated during CDA-HFD-induced liver fibrosis, with numbers markedly increased in Socs1ΔHSC mice as compared to Socs1fl/fl controls (Figure 5E). These results indicated SOCS1 expression in HSCs is critical to control inflammatory macrophage infiltration and their differentiation towards anti-inflammatory, pro-resolution phenotype.

Impact of HSC-specific SOCS1 deficiency on lymphoid cells during CDA-HFD-induced liver fibrosis

Analysis of the lymphoid cell compartment in the livers of Socs1fl/fl and Socs1ΔHSC mice revealed that the numbers of CD3+TCRβ+ total T cells, NK1.1+CD3− natural killer (NK) cells, NK1.1+CD3+ NKT cells and NK1.1+GalCer:CD1d+ invariant NKT (iNKT) cells were all increased by the CDA-HFD regimen (Figure 6A). The increase in these cell numbers were comparable between Socs1fl/fl and Socs1ΔHSC mice for total T, NK and NKT cells, whereas iNKT cells showed a much higher increase in HSC-specific SOCS1-deficient livers. Segregation of T cells into CD4+ and CD8+ subsets, and their activation and differentiation towards effector (CD69+), effector memory (CD44hiCD62Llo) and central memory (CD44hiCD62Lhi) subpopulations revealed significant increases in the numbers of these T cell subsets in CDA-HFD fed mice (Figure 6B, 6C). Most of these cell number increases were comparable between Socs1fl/fl and Socs1ΔHSC mice except CD8+ CD44hiCD62Lhi central memory cells, which were further increased in the fibrotic livers of Socs1ΔHSC mice.

Figure 6.

Effect of SOCS1 deficiency in HSCs on lymphoid cell subsets during CDA-HFD-induced liver fibrosis. Intrahepatic leukocytes isolated from the indicated groups of mice were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies indicated in Table 2B to characterize lymphoid cell populations by flow cytometry. The number of cells within specific populations were calculated from their relative proportion, total cell yield and the liver weight. (A) The numbers of CD3+TCR+ T lymphocytes, NK1.1+CD3− NK cells, NK1.1+CD3+ NKT cells and NK1.1+ CD1:GalCer tetramer+ iNKT cells within CD45+ gated hematopoietic cells. (B) The numbers of total CD4+ T lymphocytes and CD69+ effector, CD44+CD62Llo effector memory and CD44+CD62Lhi central memory subsets. (C) The numbers of total CD8+ T lymphocytes and CD69+ effector, CD44+CD62Llo effector memory and CD44+CD62Lhi central memory subsets. Pooled data from four to seven mice per group are shown (mean ± SE). One-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparison test. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001. For iNKT and CD8+ central memory T cells, exact P values of the difference between CDA-HFD-fed HSC-specific SOCS1-deficient and control mice are indicated.

Discussion

HSCs, macrophages and the crosstalk between these two cell types via cytokines, growth factors and chemokines are intricately intertwined in liver fibrosis development and its resolution.8, 9, 10,27,29 We have earlier shown that SOCS1 is a critical regulator of macrophage activation during liver fibrosis induced by CCl4.19 In the present study, we examined the role of SOCS1 in regulating HSC activation during fibrosis associated with NAFLD induced by CDA-HFD diet. For this purpose, we ablated the Socs1 gene specifically in HSCs using the LratCre deleter mouse, which has been used in several recent studies to investigate the role of HSCs in liver fibrosis and HCC development.30, 31, 32, 33 Our findings show that SOCS1 plays an indispensable role in HSCs to regulate hepatic fibrogenic response and modulate the recruitment and differentiation of inflammatory macrophages during high-fat diet-induced liver fibrosis (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Potential regulatory functions of SOCS1 in HSCs during liver fibrosis development associated with NAFLD. Following hepatocyte stress and damage induced by lipid overload, quiescent HSCs are activated directly or by mediators released by activated macrophages, undergo differentiation towards myofibroblasts, which secrete ECM to facilitate tissue repair. Liver resident and recruited macrophages secrete TGFβ and PDGFB, which promote fibrogenic gene expression and cell proliferation, respectively. Production of CCL2 by macrophages and HSCs amplify inflammatory cell recruitment and further HSC activation. Data shown in the present work indicates that SOCS1 expressed in HSCs controls the expression of PDGFB and CCL2, pro-inflammatory macrophage recruitment and differentiation, and thereby restrains the overall hepatic fibrogenic response induced by CDA-HFD.

As the serum ALT levels were similarly elevated in Socs1fl/fl and Socs1ΔHSC mice following CDA-HFD feeding (Figure 1C), the increased liver fibrosis observed in Socs1ΔHSC mice results from exaggerated fibrogenic response in the absence of SOCS1 in HSCs rather than from increased hepatocyte damage. Potential mechanisms by which SOCS1 could regulate HSC activation during NAFLD could be both direct and indirect. First, SOCS1 is well known feedback negative regulator of many cytokines that signal via the JAK-STAT pathway.14 However, only a few cytokines that use the JAK-STAT pathway as the main signaling mechanism are directly implicated in NAFLD-associated fibrosis.10 IL-6 is a JAK-STAT signaling cytokine implicated in hepatic fibrogenic response, but studies on Il6 knockout mice have reported controversial anti- or pro- fibrotic roles, possibly due to its impact on hepatocyte survival.34,35 Nonetheless, IL-6 was reported to induce Acta2 and Col1a gene expression in human HSCs,36 and IL-6 was the first cytokine known to be regulated by SOCS1.14 We found that Il6 gene expression was only modestly upregulated and to a comparable extent in the fibrotic livers of CDA-HFD-fed Socs1fl/fl and Socs1ΔHSC mice (Figure 3A). Moreover, SOCS3, which was found to be the key regulator of IL-6 signaling in vivo,26 was highly induced in the livers of CDA-HFD-fed Socs1ΔHSC mice, presumably as a mechanism to compensate for the loss of SOCS1-dependent regulatory functions. Overall, the SOCS1-dependent control of JAK-STAT signaling pathway is unlikely to be the main regulatory mechanism of HSC activation during high-fat diet-induced liver fibrosis.

Second, SOCS1 is also known to regulate growth factor signaling via receptor tyrosine kinases.15,37 Among the growth factors, PDGF is strongly implicated in liver fibrosis.10 PDGFB is a potent paracrine and autocrine mitogen for HSCs and signals via the PDGFRα and PDGFRβ receptor tyrosine kinases to activate ERK and AKT signaling pathways.38 Genetic deletion of Pdgfb in HSCs attenuates liver fibrosis whereas its transgenic expression promotes CCl4-induced liver fibrosis.24,39 SOCS1 was previously reported to interact with PDGFR and we have shown that PDGFB stimulation induces strong proliferation in SOCS1-deficient primary HSCs.18,40 The increased expression of Pdgfb gene and increased ERK1/2 phosphorylation in the fibrotic livers of Socs1ΔHSC mice fed CDA-HFD (Figure 3A, 3B), suggest that regulation of PDGFB production, likely by inflammatory macrophages, and attenuation of PDGFR signaling could be important regulatory mechanisms of SOCS1 in HSCs.

Another potential regulatory mechanism of SOCS1 on HSC activation during NAFLD-induced liver fibrosis could be regulation of TGFβ stimulation in HSCs. While the Tgfb gene expression is similarly upregulated in the livers of Socs1fl/fl and Socs1ΔHSC mice on CDA-HFD regimen, SMAD3 phosphorylation is increased in the fibrotic livers of Socs1ΔHSC mice (Figure 3A, 3B). SMAD3 mediates the pro-fibrogenic effect of TGFβ.25,41 SOCS1 may regulate TGFβ signaling in HSCs both directly and indirectly. TGFβ has been reported to activate JAK1-STAT3 signaling, which synergizes with the SMAD3 pathway.42 Gut dysbiosis caused by obesity promotes toll like receptor 4 (TLR4) signaling in hepatic cells including HSCs.10 TLR4 signaling induces NF-κB activation, which is implicated in downmodulating BAMBI, the TGFβ pseudoreceptor that negatively regulates TGFβ signaling.43 SOCS1 attenuates TLR4 signaling in macrophages,44,45 and promotes ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation p65RelA, a component of NF-κB.46 Hence, it is not unlikely that SOCS1 could also potentiate the BABMI-dependent control of TGFβ signaling. Further studies using purified HSCs or cell lines are needed to test the above hypotheses.

SOCS1 expression in HSCs appears to control amplification of the inflammatory response by regulating the pro-inflammatory macrophage compartment, possibly via regulating mediators produced by HSCs. The fibrotic livers of Socs1ΔHSC mice harbored elevated numbers of Ly6ChiCCR2+ pro-inflammatory macrophages (Figure 5C), likely recruited from circulating monocytes by chemokines. In support of this idea, the Ccl2 chemokine gene that codes for macrophage chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1) is strongly upregulated in Socs1ΔHSC mice (Figure 4B). CCL2 is produced not only by inflammatory macrophages, but also by HSCs. Activated HSCs in CDA-HFD fed mice are reported to upregulate Ccl5 expression of CCL5 (RANTES), which is chemotactic for T lymphocytes and other immune cells including monocytes, and promotes steatosis.47 We also found increased Ccl5 expression in CDA-HFD-induced fibrotic livers but the induction levels were comparable between Socs1fl/fl and Socs1ΔHSC mice (Figure 4B). The inflammatory macrophages that are recruited by CCL2 and accumulate in the fibrotic livers of Socs1ΔHSC mice could engage in a crosstalk with HSCs to further perpetuate the hepatic fibrogenic response.48,49 This heightened inflammatory setting may also interfere with the differentiation of the inflammatory macrophages towards Ly6CloCX3CR1+ restorative macrophages that promote fibrosis resolution28 as evidenced by the accumulation of Ly6ChiCCR2+CX3CR1+ in the fibrotic livers of Socs1ΔHSC mice (Figure 5E). Clearly, further studies are needed to fully characterize the crosstalk between SOCS1-deficient HSCs and macrophages.

Recent studies indicate that HSCs are heterogenous in phenotype and functions.32,50 Notably, single cell RNA sequencing studies on HSCs from the livers of mice with western diet-induced NASH identified four distinct HSC subpopulations displaying classic fibrogenic myofibroblast, proliferative, inflammatory or intermediate phenotypes.50 Similarly, dichotomous HSC populations of cytokine-producing and myofibroblast phenotypes were observed in other liver fibrosis models.32 Given the evidence for increased TGFβ and PDGF signaling and inflammatory macrophage accumulation in the fatty livers of Socs1ΔHSC mice, it would be meaningful to dissect how the loss of SOCS1 expression affects the trajectory of HSC differentiation and their heterogeneity in NAFLD and in other liver fibrosis settings.

As fibrosis development in NAFLD patients is associated with bad prognosis,4,51 deactivation of HSCs in NASH is considered a potential therapeutic avenue.9,10 The therapeutic candidates that are being tested in several ongoing clinical trials include inhibitors of chemokine signaling (CCR2/CCR5 inhibitors), collagen polymerization (LOXL2 inhibitors) and inhibition of TGFβ production (integrin α5β1 inhibitors), drugs that promote the quiescence or inactivated state of HSCs (PPAR agonists) and general antifibrotic agents (obeticholic acid, pirfenidone) at various stages of clinical testing. However, only a few of these agents such as pirfenidone have shown promising histologic and clinical improvement. Given this scenario, greater understanding of the NASH-associated fibrogenic mechanisms and endogenous regulators within HSCs is crucial to identify additional druggable molecular targets. In this context, our findings using a genetic model establish the crucial regulatory functions of SOCS1 in HSCs in attenuating high-fat diet-induced liver fibrosis. Moreover, our findings indicate that SOCS1 exerts its antifibrotic effect by attenuating TGFβ and PDGFB signaling, as well as via regulating pro-inflammatory macrophage recruitment and interfering with their differentiation toward a fully restorative macrophage phenotype. Elucidating the molecular mechanisms by which SOCS1 exerts these functions in HSCs could identify new actionable molecular targets that could complement other therapeutic avenues that are being tested.

Credit authorship contribution statement

SI conceived the idea. SI and AM obtained funding. SI, RK, AM and SR designed the experiments and analyzed data. SI wrote the manuscript with help from RK. AM and SR revised the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

Funding

This study was supported by a Project grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) to SI and AM (PJT-153255). RK received a doctoral stipend from Fonds de Recherche du Québec-Santé (FRQS).

References

- 1.Byrne C.D., Targher G. NAFLD: a multisystem disease. J Hepatol. 2015;62:S47–S64. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loomba R., Friedman S.L., Shulman G.I. Mechanisms and disease consequences of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Cell. 2021;184:2537–2564. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen A.M., Lazarus J.V., Younossi Z.M. Healthcare and socioeconomic costs of NAFLD: a global framework to navigate the uncertainties. J Hepatol. 2023;79:209–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ekstedt M., Hagstrom H., Nasr P., et al. Fibrosis stage is the strongest predictor for disease-specific mortality in NAFLD after up to 33 years of follow-up. Hepatology. 2015;61:1547–1554. doi: 10.1002/hep.27368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michelotti G.A., Machado M.V., Diehl A.M. NAFLD, NASH and liver cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:656–665. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parlati L., Regnier M., Guillou H., Postic C. New targets for NAFLD. JHEP Rep. 2021;3 doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2021.100346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedman S.L., Pinzani M. Hepatic fibrosis 2022: unmet needs and a blueprint for the future. Hepatology. 2022;75:473–488. doi: 10.1002/hep.32285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Machado M.V., Diehl A.M. Pathogenesis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1769–1777. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zisser A., Ipsen D.H., Tveden-Nyborg P. Hepatic stellate cell activation and inactivation in NASH-fibrosis-roles as putative treatment targets? Biomedicines. 2021;9 doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9040365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wiering L., Subramanian P., Hammerich L. Hepatic stellate cells: dictating outcome in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;15:1277–1292. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2023.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pradere J.P., Kluwe J., De Minicis S., et al. Hepatic macrophages but not dendritic cells contribute to liver fibrosis by promoting the survival of activated hepatic stellate cells in mice. Hepatology. 2013;58:1461–1473. doi: 10.1002/hep.26429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsuchida T., Friedman S.L. Mechanisms of hepatic stellate cell activation. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:397–411. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trautwein C., Friedman S.L., Schuppan D., Pinzani M. Hepatic fibrosis: concept to treatment. J Hepatol. 2015;62:S15–S24. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alexander W.S. Suppressors of cytokine signalling (SOCS) in the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:410–416. doi: 10.1038/nri818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kazi J.U., Kabir N.N., Flores-Morales A., Ronnstrand L. SOCS proteins in regulation of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling. Cell Mol Life Sci : CM. 2014;71:3297–3310. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1619-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sachithanandan N., Graham K.L., Galic S., et al. Macrophage deletion of SOCS1 increases sensitivity to LPS and palmitic acid and results in systemic inflammation and hepatic insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2011;60:2023–2031. doi: 10.2337/db11-0259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoshida T., Ogata H., Kamio M., et al. SOCS1 is a suppressor of liver fibrosis and hepatitis-induced carcinogenesis. J Exp Med. 2004;199:1701–1707. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kandhi R., Bobbala D., Yeganeh M., Mayhue M., Menendez A., Ilangumaran S. Negative regulation of the hepatic fibrogenic response by suppressor of cytokine signaling 1. Cytokine. 2016;82:58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2015.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mafanda E.K., Kandhi R., Bobbala D., et al. Essential role of suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 (SOCS1) in hepatocytes and macrophages in the regulation of liver fibrosis. Cytokine. 2019;124 doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2018.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsumoto M., Hada N., Sakamaki Y., et al. An improved mouse model that rapidly develops fibrosis in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Int J Exp Pathol. 2013;94:93–103. doi: 10.1111/iep.12008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Österreicher C.H., Lemberger U.J., Mahon R., Rülicke T., Trauner M., Casanova E. O147 Hepatic stellate cells are the major source of collagen in murine models of liver fibrosis. J Hepatol. 2014;60:S61. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mederacke I., Hsu C.C., Troeger J.S., et al. Fate tracing reveals hepatic stellate cells as dominant contributors to liver fibrosis independent of its aetiology. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2823. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kandhi R., Variya B., Ramanathan S., Ilangumaran S. An improved method for isolation and flow cytometric characterization of intrahepatic leukocytes from fatty and fibrotic liver tissues. Anat Rec. 2023;306:1011–1030. doi: 10.1002/ar.25039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Czochra P., Klopcic B., Meyer E., et al. Liver fibrosis induced by hepatic overexpression of PDGF-B in transgenic mice. J Hepatol. 2006;45:419–428. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dewidar B., Meyer C., Dooley S., Meindl-Beinker A.N. TGF-Beta in hepatic stellate cell activation and liver fibrogenesis-updated 2019. Cells. 2019;8 doi: 10.3390/cells8111419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Croker B.A., Krebs D.L., Zhang J.G., et al. SOCS3 negatively regulates IL-6 signaling in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:540–545. doi: 10.1038/ni931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higashi T., Friedman S.L., Hoshida Y. Hepatic stellate cells as key target in liver fibrosis. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2017;121:27–42. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2017.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krenkel O., Tacke F. Liver macrophages in tissue homeostasis and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17:306–321. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang D.Y., Friedman S.L. Fibrosis-dependent mechanisms of hepatocarcinogenesis. Hepatology. 2012;56:769–775. doi: 10.1002/hep.25670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poole L.G., Pant A., Cline-Fedewa H.M., et al. Liver fibrosis is driven by protease-activated receptor-1 expressed by hepatic stellate cells in experimental chronic liver injury. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2020;4:906–917. doi: 10.1002/rth2.12403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu X., Xu J., Rosenthal S., et al. Identification of lineage-specific transcription factors that prevent activation of hepatic stellate cells and promote fibrosis resolution. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1728–1744 e1714. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Filliol A., Saito Y., Nair A., et al. Opposing roles of hepatic stellate cell subpopulations in hepatocarcinogenesis. Nature. 2022;610:356–365. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05289-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamberger F., Mederacke Y.S., Mederacke I. An inducible model for genetic manipulation and fate-tracing of PDGFRbeta-expressing fibrogenic cells in the liver. Sci Rep. 2023;13:7322. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-34353-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kovalovich K., DeAngelis R.A., Li W., Furth E.E., Ciliberto G., Taub R. Increased toxin-induced liver injury and fibrosis in interleukin-6-deficient mice. Hepatology. 2000;31:149–159. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bansal M.B., Kovalovich K., Gupta R., et al. Interleukin-6 protects hepatocytes from CCl4-mediated necrosis and apoptosis in mice by reducing MMP-2 expression. J Hepatol. 2005;42:548–556. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.11.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kagan P., Sultan M., Tachlytski I., Safran M., Ben-Ari Z. Both MAPK and STAT3 signal transduction pathways are necessary for IL-6-dependent hepatic stellate cells activation. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gui Y., Yeganeh M., Donates Y.C., et al. Regulation of MET receptor tyrosine kinase signaling by suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene. 2015;34:5718–5728. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bonner J.C. Regulation of PDGF and its receptors in fibrotic diseases. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2004;15:255–273. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kocabayoglu P., Lade A., Lee Y.A., et al. beta-PDGF receptor expressed by hepatic stellate cells regulates fibrosis in murine liver injury, but not carcinogenesis. J Hepatol. 2015;63:141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De Sepulveda P., Okkenhaug K., Rose J.L., Hawley R.G., Dubreuil P., Rottapel R. Socs1 binds to multiple signalling proteins and suppresses steel factor- dependent proliferation. EMBO J. 1999;18:904–915. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.4.904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Uemura M., Swenson E.S., Gaca M.D., Giordano F.J., Reiss M., Wells R.G. Smad2 and Smad3 play different roles in rat hepatic stellate cell function and alpha-smooth muscle actin organization. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:4214–4224. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-02-0149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tang L.Y., Heller M., Meng Z., et al. Transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) directly activates the JAK1-STAT3 Axis to induce hepatic fibrosis in coordination with the SMAD pathway. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:4302–4312. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.773085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seki E., De Minicis S., Osterreicher C.H., et al. TLR4 enhances TGF-beta signaling and hepatic fibrosis. Nat Med. 2007;13:1324–1332. doi: 10.1038/nm1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kinjyo I., Hanada T., Inagaki-Ohara K., et al. SOCS1/JAB is a negative regulator of LPS-induced macrophage activation. Immunity. 2002;17:583–591. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00446-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mansell A., Smith R., Doyle S.L., et al. Suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 negatively regulates Toll-like receptor signaling by mediating Mal degradation. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:148–155. doi: 10.1038/ni1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Strebovsky J., Walker P., Lang R., Dalpke A.H. Suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 (SOCS1) limits NFkappaB signaling by decreasing p65 stability within the cell nucleus. FASEB J. 2011;25:863–874. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-170597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim B.M., Abdelfattah A.M., Vasan R., Fuchs B.C., Choi M.Y. Hepatic stellate cells secrete Ccl5 to induce hepatocyte steatosis. Sci Rep. 2018;8:7499. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-25699-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tacke F. Targeting hepatic macrophages to treat liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2017;66:1300–1312. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carter J.K., Friedman S.L. Hepatic stellate cell-immune interactions in NASH. Front Endocrinol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.867940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rosenthal S.B., Liu X., Ganguly S., et al. Heterogeneity of HSCs in a mouse model of NASH. Hepatology. 2021;74:667–685. doi: 10.1002/hep.31743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Torres D.M., Harrison S.A. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: fibrosis portends a worse prognosis. Hepatology. 2015;61:1462–1464. doi: 10.1002/hep.27680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]