Abstract

Cirrhosis patients have poor health-related quality of life (HRQoL). To enhance medical care and therapeutic approaches, it is crucial to identify factors that alter HRQoL in patients with cirrhosis. The present study aims to identify the potential factors affecting and promoting HRQoL in patients with liver cirrhosis. Four databases were extensively searched, including PubMed, Scopus, Embase, and Google Scholar. All original articles with liver cirrhosis and factor-altering HRQoL were included. The present study showed that elderly age, female gender, low family income, low body mass index (BMI), presence of anxiety and depression, presence of cirrhosis complications including ascites, hepatic encephalopathy (HE), and abnormal endoscopic findings, high disease severity score, presence of sarcopenia, disturbed sleep pattern, muscle cramps, poor sexual health, and increased levels of bilirubin, prothrombin time, and albumin-bilirubin ratio were the significant factors associated with lower HRQoL scores. Meanwhile, physical exercise, liver transplant, stem cell therapy, mindfulness, and the use of probiotics, rifaximin, and lactulose were associated with increased HRQoL scores. The present study recommends more prospective or randomized control trials with interventions including health education, yoga, psychotherapy, and other potential factors promoting HRQoL in patients with liver cirrhosis. The present study also emphasizes that the treating physician should consider taking HRQoL into account when prescribing medical therapy.

Keywords: HRQoL, liver cirrhosis, factor affecting, factor promoting

Liver cirrhosis is one of the chronic diseases associated with significant mortality and morbidity, affecting 845 million people globally with an annual mortality rate of two million.1 Liver cirrhosis is one of the top 20 factors associated with disability-adjusted life years and years of life lost.2 Health-related quality of life in patients with chronic liver disease (CLD) is severely impacted due to disease complications, including gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, hepatorenal syndrome, and hepatic encephalopathy.3,4 In addition to these disease complications, fatigue, muscle and joint pain, sleep disturbances, loss of self-esteem, and the inability to work also negatively affect the health-related quality of life (HRQOL). Disease management with repeated paracentesis and band ligation also significantly alter the HRQOL in patients with CLD.

Health-related quality of life is a broad term that reflects the perception of individuals on how the effects of disease and treatment impact their emotional health, physical health, functional status, and social status.5,6 Depression has been recognized as one of the factors associated with patients with CLD, with an estimated prevalence of 15% among patients waiting for liver transplants and 57% of patients with liver cirrhosis. Physicians generally consider the severity of liver disease an important prognostic factor. Few studies have suggested the role of disease severity on HRQOF. 3,7 With the recent advances in disease management, long-term survival in patients with CLDis improved.8,9 Health-related quality of life plays an essential role beyond clinical endpoints, including mortality and incidence of complications. Therefore, the present study aims to identify factors affecting and promoting HRQOF in patients with CLD.

HEALTH-RELATED QUALITY OF LIFE (HRQOL)

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines health as the state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being. Quality of life (QoL) becomes an essential part of healthcare practice and research. Most definitions of HRQoL focus on two key components. First, it is a multidimensional concept that describes the social, psychological, physical, and role-functioning facets of well-being and functioning. It can be thought of as a latent construct.10 Second, unlike QoL, HRQoL incorporates both objective and subjective viewpoints within each domain.11 Decisions about alternative treatments or the efficacy of interventions at the level of patient groups can be guided by HRQoL outcomes. HRQoL has long been disregarded as an outcome in clinical research trials, but this has drastically changed over the past ten years. In 2006, a guidance tool by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) marked a significant step towards a more structured and frequent use of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in drug development. This explains how the FDA assesses PROs, such as HRQoL, for efficiency endpoints in clinical trials (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2006).12 This advice reinforces the importance of considering HRQoL independently of medical effectiveness. When evaluating each patient individually, HRQoL can help patients and medical professionals decide on the best course of treatment.

TOOLS USED TO MEASURE HRQOL IN CIRRHOSIS

Health-related areas are typically the focus of QoLoutcome instruments used in healthcare that measure HRQoL. Physical function, psychological health, subjective symptoms, social function, and cognitive function are frequently evaluated areas. The result of HRQoL instruments provides a non-disease-specific outcome measure and reflects the patient's own experience of improved (or worsened) HRQoL. Generic HRQoL tools provide an overview of QoL and include a range of domains that can be applied to different patient populations withchronic diseases. The benefit of using generic questionnaires is that they allow the relative impact of different diseases to be compared, which is helpful to health policymakers. However, a major drawback is that generic instruments lack sensitivity and do not include disease-specific domains that may be crucial to establishing clinical changes. Disease-specific tools provide greater specificity and sensitivity, as they were created to be valid only for a specific disease.

The World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief Version (WHOQOL-BREF) is a generic tool that measures QoL over four domains: physical, psychological, social and environmental aspects. It is easy to administer and is validated among chronic conditions in primary care settings.13 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36) is a self-administered tool that measures domains of physical function, mental health, social function, role physical, role emotional, pain, vitality, and general health.14 The Sickness Impact Profile (SIP)15 covers 12 categories of activities of daily living and is a lengthy tool due to the wide range of topics it covers. The SF-36 is sensitive to a wider range of disability levels, from patients with severe levels of disability to the general population. The Nottingham Health Profile (NHP)16 is known to be less sensitive to changes in conditions where effects are relatively mild because it focuses on more severe levels of disability. EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale (EQ VAS) assesses health in the domains of mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression.17

As advanced cirrhotics have a multitude of symptoms with systemic complications, the application of disease-specific HRQoLtools helps in management and provids better care for those patients. Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire (CLDQ) is a brief questionnaire that measures domains of fatigue, emotional function, abdominal symptoms, worry, activity, and systemic symptoms. It is a widely used, validated tool for cirrhotics and is translated across various languages.18 Another tool Liver Disease Quality of Life (LDQOL) measures symptoms of liver disease and the effects of liver disease over nine domains and correlates highly with SF-36 scores.19 The Liver Disease Symptom Index 2.0 (LDSI 2.0)20 is an upgraded version that measures symptom severity and symptom hindrance in the past week and is translated into various languages. Concerning liver transplant, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDKK) quality of life questionnaire21,22 was developed for patients undergoing liver transplantation and assesses domains of liver disease symptoms, physical function, health satisfaction, and overall well-being. Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) is a model that uses computerized adaptive measurement system thatoffers a tailored yet comprehensive appraisal of various HRQOL domains. It has been validated among patients with cirrhosis.23

FACTORS AFFECTING HEALTH-RELATED QUALITY OF LIFE

Demographic Factors and Etiology of Cirrhosis

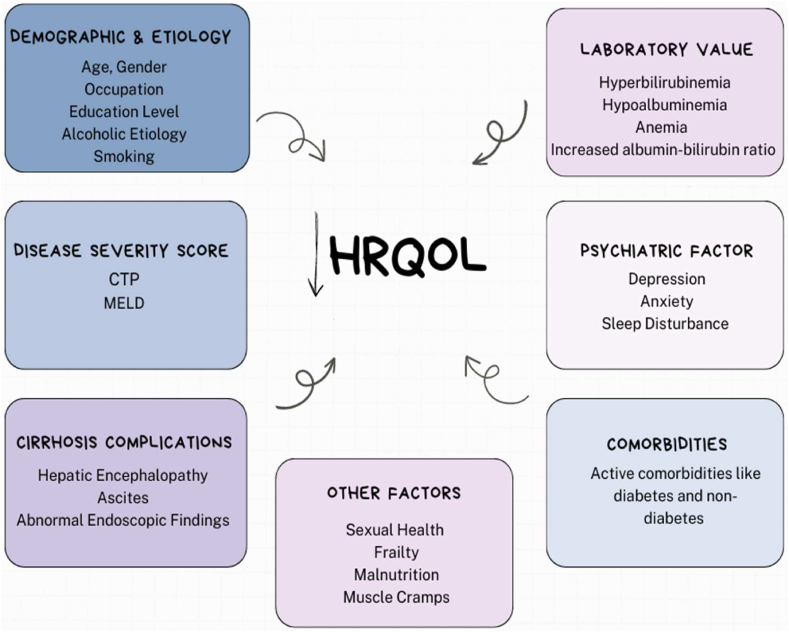

Few studies have reported the association between demographic factors (age, gender, education, BMI, and employment) and the etiology of cirrhosis in HRQoFin patients with liver cirrhosis. Janani et al. 201824 reported a significant relationship between age and adecreased HRQoL score. Meanwhile, Labenz et al., 201925 showed a significant relationship between the female gender and a decreased HRQoL score. Thiele et al., 2013,26 reported a significant association between BMI and HRQoL in liver cirrhosis patients independently in the presence of ascites. Meanwhile, Nouh et al., 201527 reported a significant relationship between education and occupation with lower 36 item short form survey (SF-36) scores. Similarly, Pradhan et al. 202028 reported a significant association between employment and higher annual income and an improved HRQoL score. Concerning etiology, Thiele et al. 201326 reported a positive association between the non-alcoholic etiology of cirrhosis and a low HRQoL score. However, Marchesini et al.,20017 showed no significant relation between HRQoL and the etiology of cirrhosis (Table 1 & Figure 1).

Table 01.

Factors Affecting Health-Related Quality of Life in Liver Cirrhosis.

| Author name | Study type | Sample size | HRQoL tool | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Factors and Etiology of Cirrhosis | ||||

| K Janani24 | Prospective | 149 | SF-36 and CLDQ |

|

| Christian Labenz25 | Prospective | 218 | CLDQ |

|

| Maja Thiele26 | Prospective | 92 | CLDQ |

|

| Mohamed Alaa Eldin Nouh27 | Prospective | 200 | SF-36 |

|

| Ravi R Pradhan28 | Prospective | 60 | SF-36 |

|

| G Marchesini7 | Prospective | 544 | SF-36 and Nottingham Health Profile questionnaires |

|

| Beverley Kok33 | Prospective | 402 | CLDQ and EQ-VAS |

|

| Winfried Hauser39 | Prospective | 255 | CLDQ and SF-36 |

|

| Disease Severity Score | ||||

| Maja Thiele26 | Prospective | 92 | CLDQ |

|

| Mohamed Alaa Eldin Nouh27 | Prospective | 200 | SF-36 |

|

| Ravi R Pradhan28 | Prospective | 60 | SF-36 |

|

| K Janani 201824 | Prospective | 149 | SF-36 and CLDQ |

|

| Domenica Gazineo29 | Prospective | 254 | SF-12 and NHP |

|

| Sammy Saab31 | Prospective | 150 | SF-36 and CLDQ |

|

| Cirrhosis Complications | ||||

| Katherine C Barboza26 | Prospective | 43 | SF-36 and CLDQ |

|

| Sammy Saab31 | Prospective | 150 | SF-36 and CLDQ |

|

| Ravi R Pradhan28 | Prospective | 60 | SF-36 |

|

| Christian Labenz25 | Prospective | 218 | CLDQ |

|

| Ru Gao32 | Prospective | 392 | SF-36 |

|

| Beverley Kok33 | Prospective | 402 | CLDQ & EQ-VAS |

|

| Laboratory Values | ||||

| Ru Gao32 | Prospective | 392 | SF-36 |

|

| Beverley Kok33 | Prospective | 402 | CLDQ and EQ-VAS |

|

| Christian Labenz25 | Prospective | 218 | CLDQ |

|

| Akira Sakamaki34 | Prospective | 89 | CLDQ |

|

| Psychiatric Factors | ||||

| Silvia Nardelli35 | Prospective | 60 | SF-36 |

|

| T Dang37 | Prospective | 304 | CLDQ and EQ-VAS |

|

| T Dang38 | Prospective | 304 | CLDQ and EQ-VAS |

|

| Katherine C Barboza30 | Prospective | 43 | SF-36 and CLDQ |

|

| Winfried Hauser39 | Prospective | 255 | CLDQ and SF-36 |

|

| Co-Morbidities | ||||

| Winfried Hauser39 | Prospective | 255 | CLDQ and SF-36 |

|

| K Janani24 | Prospective | 149 | SF-36 and CLDQ |

|

| Hospitalization | ||||

| Beverley Kok18 | Prospective | 402 | CLDQ and EQ-VAS |

|

| Other Factors | ||||

| Fasiha Kanwal40 | Prospective | 203 | LDQOL 1.0 |

|

| Beverley Kok33 | Prospective | 402 | CLDQ and EQ-VAS |

|

| T Dang37 | Prospective | 304 | CLDQ and EQ-VAS |

|

| T Dang38 | Prospective | 304 | CLDQ and EQ-VAS |

|

| Christian Labenz25 | Prospective | 218 | CLDQ |

|

| Yangyang Hui41 | Prospective | 227 | EuroQol Group 5 Dimension (EQ-5D) |

|

Abbreviation:AS: Abdominal Symptoms; BP: Bodily Pain; CLDQ: Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire; CTP: Child-Turcotte-Pugh; EQ-5D: EuroQol Group 5 Dimension; EQ-VAS: EuroQoL Group-visual analog scale; HE: Hepatic Encephalopathy; HRQoL: Health Related Quality of Life; MCS: Mental Component Score; MELD: Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; NHP: Nottingham Health Profile questionnaires; SF_36: 36-Item Short Form Survey.

Figure 1.

Factors affecting health related quality of life.

Disease Severity Score

In clinical settings, the severity of liver cirrhosis is measured by the Child-Turcotte-Pugh score, a model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score. Few studies have reported the positive association of CTP and MELD with HRQoL in patients with liver cirrhosis. Thiele et al. 201326 reported a significant association between an increase in CTP and decreased HRQoL in liver cirrhosis patients. Similarly, Nouh et al. 201527 and Pradhan et al. 202028 reported a significant decrease in HRQoL with an increase in CTP score. Janani et al. 201824 showed a direct and significant association between MELD and HRQoL scores. However, Gazinea et al.,29 2021, showed no association between MELD and HRQoL score (Table 1 & Figure 1).

Complications of Cirrhosis

In the long run, cirrhosis due to hepatic dysfunction in the long run, can result in portal hypertension. Both of these, in combination or alone, can lead to many complications, including ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, hepatocellular carcinoma, and coagulopathy. These complications not only affect survival but also decrease HRQoL. Barboza et al. 201630 showed a significant relationship between the presence of hepatic encephalopathy (HE) and decreased general and disease-specific HRQoL scores. Similarly, Saab et al. 200531 showed a significant association between ascites and HE with a decreased HRQoL score. Pradhan et al. 28 reported a significant decrease in HRQoL in patients with ascites and abnormal upper GI endoscopy findings (Table 1 & Figure 1).

Serological Markers

Serological markers are used to determine the patient's overall health and well-being. Few studies have reported the role of lab parameters in HRQoL in patients with liver cirrhosis. Gao et al. 201232 reported a significant decrease in HRQoL with increased bilirubin levels and prothrombin time. Kok et al., 202033 reported a significant decrease in HRQoL scores with a decrease in serum albumin levels. Correspondingly, Labenz et al., 201925 studied the role of c-reactive protein (CRP) and hemoglobin (Hb) in cirrhosis patients. The study reported a significant decrease in HRQoL with increased CRP levels in cirrhotic patients with a disease severity score of CTP A. However, lower Hb was significantly associated with decreased HRQoL in cirrhotic patients with a disease severity score of CTP B or CTP C. Sakamaki et al. 2022,34 described the role of albumin–bilirubin. The study showed a significant decrease in HRQoL with an increase in the albumin–bilirubin score (Table 1 & Figure 1).

Psychiatric Factors

Psychiatric factors are essential in determining HRQoL in patients with liver cirrhosis. Most studies have suggested the indispensable role of psychiatric factors like depression, coping mechanisms, and anxiety in HRQoL in cirrhotic patients. Nardelli et al. 201335 and Banerjee et al. 202036 reported a significant decrease in HRQoL score in cirrhotic patients with depression and anxiety. Similarly, Dang et al. 201837 and Dang et al. 202238 reported a significant relationship between anxiety and decreased HRQoL scores in cirrhotic patients (Table 1 & Figure 1).

Co-Morbidities

Co-morbid conditions like diabetes and hypertension were found to be significant factors affecting HRQoL in patients with liver cirrhosis. Hauser et al. 200439 reported a significant relationship between a number of co-morbidities and decreased HRQoL scores. The study also reported decreased SF-36 mental scores in patients with active cardiovascular disease. Similarly, Janani et al. 201824 showed no significant difference in HRQoL scores in diabetic cirrhosis patients with or without other co-morbid conditions. Nevertheless, the author reported no significant relationship between non-diabetic co-morbid conditions in lower HRQoL scores in the physical domain (Table 1 & Figure 1).

Hospitalization

A person's HRQoF can be significantly impacted by hospitalization and the seriousness of the underlying medical condition. HRQoL is independently associated with increased mortality or unplanned hospitalizations among cirrhotic patients. Additionally, HRQoL may be impacted by the length of hospitalization. Longer stays could cause more stress, discomfort, and disruption to daily routines, influencing how the patient perceives well-being. Kok et al., 202033 reported that an increase in CLDQ and EuroQoL Group-visual analog scale (EQ-VAS) by one point and 10 points decreased the likelihood of hospitalization and mortality by 30% and 13%, respectively. Routine measurement of HRQoL in the outpatient setting, when combined with other variables including sarcopenia and frailty, is likely to further improve prognostication among cirrhotic patients.

Other Factors

Apart from the major factors (as mentioned above), a few more trivial factors were studied and were found to be associated with the decrease in HRQoL in patients with liver cirrhosis, including malnutrition, sarcopenia, sleep disturbance, frailty, sexual health, and muscle cramps. Kanwal et al. 200440 reported a significant association between increased CTP scores and sexual health and functioning. Kok et al. 202033, Dang et al. 2018,37 Dang et al. 202238, and Labenz et al. 201925 reported a significant decrease in HRQoL scores in cirrhotic patients with frailty. Similarly, Hui et al. 202241 reported a significant association between sleep disturbance and frailty and a decreased HRQoL score. Gutteling et al. 2007 reported a significant association between pruritus, joint pain, abdominal pain, muscle cramps, fatigue, depression, and anxiety and decreased HRQoL scores (Table 1 & Figure 1).

FACTORS PROMOTING HEALTH-RELATED QUALITY OF LIFE

Physical Exercise

The majority of chronic liver disease patients have sedentary lifestyle, little physical activity, and malnutrition as additional complication. As a result of these, cirrhotic patients frequently exhibit frailty and sarcopenia, which are important indicators of higher morbidity and mortality. Few studies have shown the beneficial effect of exercise on patients with liver cirrhosis. A randomized controlled study by Sirisunhirun et al. 2022,42 studied the benefits of a home-based exercise training program. An experimental group of compensated cirrhotic patients was subjected to 12 weeks of home-based exercise training that included several aerobic/isotonic moderate-intensity continuous trainings. The study showed significant improvement in the fatigue domain of the CLDQ. Similar results were observed in the study by Zenith et al. 2014.43 The study showed significant improvement in fatigue scores among cirrhotic patients undergoing 8 weeks of supervised aerobic exercise training. Interestingly, a study by Rodriguez et al. 201644 reported no significant association between supervised physical exercise and HRQOL, as assessed by the CLDQ. (Table 2 & Figure 2). Physical exercises improve frailty by increasing muscle mass, increasing anabolism, and having an effect on sarcopenia.

Table 2.

Factors Promoting Health-Related Quality of Life in Liver Cirrhosis.

| Author name | Study type | Sample size (case: control) | HRQoL tool | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Exercise | ||||

| Pavapol Sirisunhirun42 | RCT | 40 (20:20) | CLDQ |

|

| Zenith L43 | RCT (pilot study) | 9:10 | CLDQ |

|

| Ricardo U Macías-Rodríguez44 | RCT | 14:15 | CLDQ |

|

| Eva Román81 | RCT | 8:9 | SF-36 |

|

| Liver Transplant | ||||

| Carmen Pantiga45 | Prospective | 150 | PLC |

|

| Rosario Girgenti46 | Retrospective | 82 | MQOL |

|

| Gen-Shu Wang82 | Prospective | 60 with LT 55 with CLD 50 as HI |

SF-36 |

|

| Mahasen Mabrouk83 | Prospective | 103:50 | LDQOL 1.0 and SF-36 |

|

| John P Duffy84 | Prospective | 293 | LDQOL and SF-36 |

|

| Jasmohan S Bajaj47 | Prospective | 45 | SIP |

|

| Probiotics | ||||

| Vibhu Vibhas Mittal49 | Prospective | 322 | SIP |

|

| Eva Román50 | RCT | 18:18 | NHP |

|

| Jane Macnaughtan51 | RCT | 33:35 | SF-36 |

|

| Stem Cell Therapy | ||||

| Hosny Salama53 | RCT | 50:50 | SF-36 |

|

| Mehdi Mohamadnejad54 | Phase 1 Study | 4 | SF-36 |

|

| Pharmacological Therapy | ||||

| Srinivasa Prasad55 | RCT (Lactulose – 30–60 ml in 2 or 3 divided doses for 3 months) | 31:30 | SIP |

|

| A Sanyal56 | RCT (Rifaximin 550 mg BD for 6 months) | 101:118 | CLDQ |

|

| Shinya Sato57 | Prospective (l-carnitine – 1800 mg/day for 6 months) | 30 | Self-report questionnaire |

|

| Eileen L Yoon58 | RCT (l-carnitine – 2 g/day for 24 weeks) | 75:75 | SF-36 |

|

| Mindfulness | ||||

| Jasmohan S Bajaj47 | Prospective | 20 | SIP |

|

Abbreviation: CLD: Chronic Liver Disease; CLDQ: Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire; HI: Health Individuals; HRQoL: Health related quality of life; LDQoL: Liver Disease Quality of Life; LT: Liver transplant; MQoL: McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire; NHP: Nottingham Health Profile; PLC: Profile of Quality of Life in the Chronically; RCT: Randomized control trial; SF-36: 36-Item Short Form Survey; SIP: Sickness Impact Profile.

Figure 2.

Factors promoting health related quality of life.

Liver Transplant

For patients with end-stage liver disease, liver transplantation (LT) is the standard of care, witht 1- and 5-year survival rates of more than 90% and 70%, respectively. Few studies have reported the positive role of LT and changes in HRQOL. Pantiga et al. 200545 reported a significant improvement in HRQOL in cirrhotic patients with liver transplants compared to non-cirrhotic patients. However, the HRQOL score does not reach the level of healthy individuals. Girgenti et al. 202046, reported a high mean score of HRQoL in patients who underwent a liver transplant. Similar results were reported by Bajaj et al. 2017.47 The study reported a significant improvement in HRQoL in liver cirrhosis patients after liver transplantation (Table 2 & Figure 2).

Probiotics

Infections are more likely to occur in CLD patients due to their immune-compromised states. In healthy individuals, bacteria that are typically present and restricted to the bowel can enter the bloodstream and cause serious infections that are frequently fatal and have a terrible impact on liver function. This is attributed to issues with the body's immune defense system and an imbalance of beneficial and harmful bacteria in the bowel. Probiotics, or “bio-friendly” food supplements, have been shown by researchers to alter gut flora and have a variety of positive effects on cirrhosis. These include reducing markers of liver damage and the functioning of vital immune cells.48 Mittal et al. 201149 performed a randomized control trial with probiotics, lactulose, and no treatment. The study reported significant HRQoL score improvement secondary to improvement in hepatic encephalopathy in patients with probiotics with liver cirrhosis. However, a randomized control trial by Roman et al. 201950 showed no significant improvement with probiotics. Nonetheless, a trend toward improvement in social isolation was observed in the probiotic group. Similar results were reported by Macnaughtan et al., 2020.51 The study reported no significant change in the HRQoL score in the probiotic group compared to the control group (Table 2 & Figure 2).

Stem Cell Therapy

Cell therapy with embryonic, fetal, mononuclear, and mesenchymal stromal cells is the most advanced field of modern biotechnology and medicine.52 Few studies have reported the potential role of stem cell therapy (SCT) in patients with liver cirrhosis. Salama et al. 201253 performed a randomized control trial with SCT. The study reported significant improvement in HRQoL scores with the use of SCT in the case group compared to the control group. Similar results were reported by Mohamadnejad et al. 2007.54 The study reported a significant improvement in HRQoL scores on follow-up (Table 2 & Figure 2).

Pharmacological Therapy

One of the main goals of symptomatic therapies in patients with liver cirrhosis is to improve health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Prasad et al. 200755 reported a significant improvement in HRQoL secondary to an improvement in hepatic encephalopathy with lactulose compared to the no-treatment group. Sanyal et al. 201156 reported a significant improvement in HRQoL secondary to improvement in hepatic encephalopathy with the use of rifaximin compared to a control group. Sato et al. 202057, and Yoon et al. 202258, reported a significant improvement in HRQoL score secondary to improvement in hepatic encephalopathy with l-Carnitine in patients with liver cirrhosis (Table 2 & Figure 2).

Mindfulness

A short mindfulness and supportive group therapy program significantly improves patient-reported outcomes (PRO) and caregiver burden in cirrhotic patients with depression. This non-pharmacological method could be a promising approach to alleviating psychosocial stress in patients with end-stage liver disease. Bajaj et al. 2017,59 reported a significant improvement in HRQoL in cirrhotic patients with mindfulness-based stress reduction therapy (Table 2 & Figure 2).

Caregiver Stress and HRQoL

Patients with cirrhosis require extensive caregiving; many cannot drive to their frequent doctor appointments due to frailty and hepatic encephalopathy, and up to one-third of them have difficulty with daily living activities due to frailty and cognitive impairment. As a result, a typical cirrhotic patient needs 9 h per week of informal care from friends and family.60,61 This places a heavy burden on these caregivers, resulting in lower quality-of-life scores than the general population.60,62 Interestingly, a surprising number of cirrhosis patients experience symptoms typically associated with end-stage cancer. Nguyen et al. 201563 reported that primary caregivers of patients with advanced liver disease have significantly lower HRQoL scores. Similarly, Bajaj et al. 201164 reported that the presence of HE, higher MELD score, and cognitive dysfunction were the significant factors associated with caregiver burden. Miyazaki et al. 201065 reported that a higher MELD score (>15) was the significant factor associated with caregiver burden. Furthermore, the study also reported that caregivers of patients with an alcoholic etiology had significantly higher burden, stress, and depression compared to the patients with other etiologies (Table 3) (Figure 3).

Table 3.

Caregiver Stress.

| Author name | Study type | Sample size | HRQoL tool | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Douglas L Nguyen63 | Prospective | 50 | SF-36 | Significant decrease in HRQoL scores. |

| Jasmohan S Bajaj64 | Prospective | 104 | ZBI | Previous HE, higher MELD scores, financial status, and cognitive dysfunction were the significant factors associated with caregiver burden. |

| Eliane Tiemi Miyazaki65 | Prospective | 61 | CBS | Alcoholic etiology and higher MELD scores were the significant factors associated with caregiver burden. |

| Zachary M Saleh85 | Prospective | 25 | ZBI, DT and CCI | HE and strict nutrition and diet were the significant factors associated with caregiver burden |

Abbreviations: CBS: Caregiver Burden Scale; CCI: Caregiver Captivity Index; DT: Distress Thermometer; HE: Hepatic Encephalopathy; HRQoL: Health related quality of life; MELD: Model For End-Stage Liver Disease; ZBI: Zarit Burden Interview.

Figure 3.

Factors associated with caregiver burden.

PALLIATION IN CIRRHOSIS

Management of Pain

Acute or chronic pain from various causes may develop in patients with liver disease. Patients with cirrhosis frequently experience pain. Patients with advanced liver disease may also experience gynecomastia (leading to mastalgia) and ascites, which can cause lower back and abdominal pain. It is paramount to understand the cause of pain, as pain due to ascites responds to paracentesis. In a systematic review of five studies, the prevalence of pain in patients with end-stage liver disease ranged from 30 to 79 percent. In a large database study of cirrhosis patients from the Veterans Health Administration, annual opioid prescriptions rose over time from 36% in 2005 to 47% in 2014.66

Among patients with cirrhosis, where liver function declines, they are vulnerable to the negative effects of various drugs due to altered pharmacokinetics and hemodynamic changes.67 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are linked to a higher risk of variceal hemorrhage, decreased renal function, and the emergence of diuretic-resistant ascites. As a result, NSAIDs (including aspirin) should generally be avoided by people with cirrhosis. Selective COX-2 inhibitors have lower rates of GI and renal toxicity. They have, however, been linked to a higher incidence of harmful cardiovascular events. At present, additional safe data are lacking to support the use of COX-2 inhibitors in patients with liver cirrhosis. In patients with advanced liver disease, the use of opioids should be in a controlled environment.68 When administered to patients with mild hepatic dysfunction, fentanyl appears to be safe. With lower doses, hydromorphone, oxycodone, or morphine can be administered over longer periods of time. Tramadol might be risk-free, but there is not much data to support it. Any opioid may become tolerable with repeated use, necessitating higher doses and raising the risk of hepatic encephalopathy.69 The medication has to be started in low doses, using short-acting drugs wherever possible and monitored carefully for potential precipitation of hepatic encephalopathy.

Pruritus

Though cholestatic hepatitis causes pruritus more commonly, it can also be seen among patients with cirrhosis to some extent. Potential reasons include the dysregulated metabolism of “pruritogens” such as bile salts, lysophosphatidic acid, and autotaxin hormonal changes associated with cirrhosis; nutritional deficiency; dry skin; drug induced; skin changes; and dehydration.70 General measures that help with pruritus include topical emollients, avoidance of hot baths, cool, humidified air, loose-fitting clothes, and minimizing the use of soap and fragrances. Patients who experience moderate to severe pruritus may benefit from pharmaceutical treatments. One option for treatment is a bile acid sequestrant (colestipol or cholestyramine). The cautious use of rifampin or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (sertraline) for patients who do not respond to or cannot tolerate a bile acid sequestrant could be considered.71 However, gabapentin can be considered in cases where uremia induces pruritus.72

Muscle Cramps

Cirrhosis patients may experience painful muscle cramps, which can be debilitating. The cause is incompletely understood. Other causes (such as electrolyte abnormalities, acute kidney injury, etc.) for patients with muscle cramps should be ruled out. Treatments like taurine (2–3 g once daily), zinc repletion (for patients with low levels), and vitamin E (200 mg three times daily) may be beneficial.73 Tapper et al. 202274 performed a Pickle Juice Intervention for Cirrhotic Cramps Reduction (PICCLES) trial to assess pickle juice's effectiveness in patients with liver cirrhosis. A study reported significant improvement in muscle cramps. However, the study did not show significant improvement in sleep or HRQoL. Similar results were reported by Angeli et al. 199675 with albumin infusion. A study reported significant improvement in muscle cramps in cirrhotic patients on albumin compared to placebo.

Sleep Disorders

Cirrhosis of the liver frequently causes sleep-wake disturbances, which are linked to a lower quality of life. Sleep-wake inversion, excessive daytime sleepiness, and insomnia are the most frequent abnormalities closely associated with hepatic encephalopathy. The underlying pathophysiological mechanisms for sleep disturbances in cirrhosis are complicated and may include altered ghrelin secretion profiles, altered melatonin and glucose metabolism, and changes in thermoregulation.76 Lactulose and lactitol are effective in improving HE and QoL.77 Treatment of sleep disorders should be targeted at correction of HE, treatment of associated depression and anxiety, avoiding stimulants such as coffee and nicotine at night, and complete avoidance of alcohol. Pharmacologic treatments include the use of antihistamines such as hydroxyzine controlled use of benzodiazepines with safer profiles such as clonazepam and zolpidem.

Palliative Care in Cirrhosis

Patients with end stage liver disease (ESLD) have a profound level of discomfort and often have substantial suffering. HRQoL, which is compromised by associated complications, deteriorates with increasing disease severity3,78,79 According to the Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments (support), ESLD patients have moderate to severe pain towards the end of life comparable to those of patients with lung or colorectal cancer. Most patients in this study expressed a preference for dying rather than living in a coma or on prolonged life support, suggesting the importance of understanding patients' preferences for care, especially for end-of-life approaches. Some may view palliative care and liver transplantation as mutually exclusive. But given the difficulties with end-of-life communication in patients trying to maintain hope for a cure in the face of a serious illness and the high rate of symptom burden in this population, patients awaiting liver transplantation for ESLD are likely to benefit from palliative care.80

Credit authorship contribution statement

Siddheesh Rajpurohit: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing Review and Editing.

Balaji Musunuri: Writing Review and Editing, supervision.

Pooja Basthi Mohan: Writing Review and Editing, visualization.

Ganesh Bhat: Writing Review and Editing, supervision.

Shiran Shetty: Writing Review and Editing, supervision.

Conflicts of interest

None to Declare.

Acknowledgment

None to declare.

Funding

No funding was received for the present study.

References

- 1.Byass P. The global burden of liver disease: a challenge for methods and for public health. BMC Med. 2014;12:159. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0159-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asrani S.K., Devarbhavi H., Eaton J., Kamath P.S. Burden of liver diseases in the world. J Hepatol. 2019;70:151–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Younossi Z.M., Boparai N., Price L.L., Kiwi M.L., McCormick M., Guyatt G. Health-related quality of life in chronic liver disease: the impact of type and severity of disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2199–2205. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bao Z.J., Qiu D.K., Ma X., et al. Assessment of health-related quality of life in Chinese patients with minimal hepatic encephalopathy. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3003–3008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i21.3003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Souza NP de, Villar L.M., Garbin A.J.Í., Rovida T.A.S., Garbin C.A.S. Assessment of health-related quality of life and related factors in patients with chronic liver disease. Braz J Infect Dis. 2015;19:590–595. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2015.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mancina R.M., Pagnotta R., Pagliuso C., et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms of and psychosocial changes in inflammatory bowel disease: a nursing-led cross-sectional study of patients in clinical remission. Medicina. 2020;56:45. doi: 10.3390/medicina56010045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marchesini G., Bianchi G., Amodio P., et al. Factors associated with poor health-related quality of life of patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:170–178. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.21193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orr J.G., Homer T., Ternent L., et al. Health related quality of life in people with advanced chronic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2014;61:1158–1165. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhanji R.A., Carey E.J., Watt K.D. Review article: maximising quality of life while aspiring for quantity of life in end-stage liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46:16–25. doi: 10.1111/apt.14078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quality of Life Assessments in Clinical Trials. By B. Spilker. (Pp. 470; illustrated.) Raven Press: New York 1990. Psychol Med. 1990;vol. 20 doi: 10.1017/S0033291700037247. 1010-1010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Testa M.A., Simonson D.C. Assessment of quality-of-life outcomes. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:835–840. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603283341306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.U.S. department Of health and human Services FDA center for drug evaluation and research, U.S. Department of health and human Services FDA center for biologics evaluation and research, U.S. Department of health and human Services FDA center for devices and radiological health. Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims: draft guidance. Health Qual Life Outcome. 2006;4:79. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.WHOQOL - Measuring Quality of Life| The World Health Organization. Accessed July 19, 2023. https://www.who.int/tools/whoqol.

- 14.Coons S.J., Rao S., Keininger D.L., Hays R.D. A comparative review of generic quality-of-life instruments. Pharmacoeconomics. 2000;17:13–35. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200017010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bergner M., Bobbitt R.A., Carter W.B., Gilson B.S. The Sickness Impact Profile: development and final revision of a health status measure. Med Care. 1981;19:787–805. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198108000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hunt S.M., McKenna S.P., McEwen J., Williams J., Papp E. The Nottingham Health Profile: subjective health status and medical consultations. Soc Sci Med. 1981;15(3 Pt 1):221–229. doi: 10.1016/0271-7123(81)90005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng Y., Parkin D., Devlin N.J. Assessing the performance of the EQ-VAS in the NHS PROMs programme. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:977–989. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0537-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Younossi Z.M., Guyatt G., Kiwi M., Boparai N., King D. Development of a disease specific questionnaire to measure health related quality of life in patients with chronic liver disease. Gut. 1999;45:295–300. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanwal F., Spiegel B.M.R., Hays R.D., et al. Prospective validation of the short form liver disease quality of life instrument. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:1088–1101. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Plas S.M., Hansen B.E., de Boer J.B., et al. The liver disease symptom index 2.0; validation of a disease-specific questionnaire. Qual Life Res. 2004;13:1469–1481. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000040797.17449.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim W.R., Lindor K.D., Malinchoc M., Petz J.L., Jorgensen R., Dickson E.R. Reliability and validity of the NIDDK-QA instrument in the assessment of quality of life in ambulatory patients with cholestatic liver disease. Hepatology. 2000;32:924–929. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.19067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gross C.R., Malinchoc M., Kim W.R., et al. Quality of life before and after liver transplantation for cholestatic liver disease. Hepatology. 1999;29:356–364. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cella D., Riley W., Stone A., et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005-2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:1179–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janani K., Jain M., Vargese J., et al. Health-related quality of life in liver cirrhosis patients using SF-36 and CLDQ questionnaires. Clin Exp Hepatol. 2018;4:232–239. doi: 10.5114/ceh.2018.80124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Labenz C., Toenges G., Schattenberg J.M., et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with compensated and decompensated liver cirrhosis. Eur J Intern Med. 2019;70:54–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2019.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thiele M., Askgaard G., Timm H.B., Hamberg O., Gluud L.L. Predictors of health-related quality of life in outpatients with cirrhosis: results from a prospective cohort. Hepat Res Treat. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/479639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nouh M., Badawy A.M., Mohamed H.M., El-Kashash S.A.E.A. Study of the impact of liver cirrhosis on health-related quality of life in chronic hepatic patients, menoufia governorate. Afro-Egyptian Journal of Infectious and Endemic Diseases. 2015;5(3):177–182. doi: 10.21608/aeji.2015.17827. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pradhan RR, Kafle Bhandari B, Pathak R, et al. The assessment of health-related quality of life in patients with chronic liver disease: a single-center study. Cureus. 12:e10727 doi:10.7759/cureus.10727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Gazineo D., Godino L., Bui V., et al. Health-related quality of life in outpatients with chronic liver disease: a cross-sectional study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021;21:318. doi: 10.1186/s12876-021-01890-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barboza K.C., Salinas L.M., Sahebjam F., Jesudian A.B., Weisberg I.L., Sigal S.H. Impact of depressive symptoms and hepatic encephalopathy on health-related quality of life in cirrhotic hepatitis C patients. Metab Brain Dis. 2016;31:869–880. doi: 10.1007/s11011-016-9817-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saab S., Ibrahim A.B., Shpaner A., et al. MELD fails to measure quality of life in liver transplant candidates. Liver Transplant. 2005;11:218–223. doi: 10.1002/lt.20345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gao R., Gao F., Li G., Hao J.Y. Health-related quality of life in Chinese patients with chronic liver disease. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/516140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kok B., Whitlock R., Ferguson T., et al. Health-related quality of life: a rapid predictor of hospitalization in patients with cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:575–583. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakamaki A., Takamura M., Sakai N., et al. Longitudinal increase in albumin–bilirubin score is associated with non-malignancy-related mortality and quality of life in patients with liver cirrhosis. PLoS One. 2022;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0263464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nardelli S., Pentassuglio I., Pasquale C., et al. Depression, anxiety and alexithymia symptoms are major determinants of health related quality of life (HRQoL) in cirrhotic patients. Metab Brain Dis. 2013;28:239–243. doi: 10.1007/s11011-012-9364-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Banerjee A., Jana A.K., Praharaj S.K., Mukherjee D., Chakraborty S. Depression and anxiety in patients with chronic liver disease and their relationship with quality of life. Annals of Indian Psychiatry. 2020;4:28. doi: 10.4103/aip.aip_46_19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dang T., Mitchell N., Farhat K., et al. A183 anxiety impacts health-related quality of life and hospitalizations in patients with cirrhosis. J Canadian Assoc Gastroenterl. 2018;1(suppl l_2):271–272. doi: 10.1093/jcag/gwy009.183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dang T.T., Patel K., Farhat K., et al. Anxiety in cirrhosis: a prospective study on prevalence and development of a practical screening nomogram. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;34:553–559. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000002301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hauser W, Holtmann G, Grandt D. Determinants of Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Chronic Liver Diseases. Published online 2004. doi:10.1016/S1542-3565(03)00315-X. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Kanwal F., Hays R.D., Kilbourne A.M., Dulai G.S., Gralnek I.M. Are physician-derived disease severity indices associated with health-related quality of life in patients with end-stage liver disease? Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1726–1732. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hui Y., Li N., Yu Z., et al. Health-related quality of life and its contributors according to a preference-based generic instrument in cirrhosis. Hepatology Communications. 2022;6:610–620. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sirisunhirun P., Bandidniyamanon W., Jrerattakon Y., et al. Effect of a 12-week home-based exercise training program on aerobic capacity, muscle mass, liver and spleen stiffness, and quality of life in cirrhotic patients: a randomized controlled clinical trial. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22:66. doi: 10.1186/s12876-022-02147-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zenith L., Meena N., Ramadi A., et al. Eight weeks of exercise training increases aerobic capacity and muscle mass and reduces fatigue in patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1920–1926.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Macías-Rodríguez R.U., Ilarraza-Lomelí H., Ruiz-Margáin A., et al. Changes in hepatic venous pressure gradient induced by physical exercise in cirrhosis: results of a pilot randomized open clinical trial. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2016;7:e180. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2016.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pantiga C, López L, Pérez M, et al. Quality of Life in Cirrhotic Patients and Liver Transplant Recipients.

- 46.Girgenti R., Tropea A., Buttafarro M.A., Ragusa R., Ammirata M. Quality of life in liver transplant recipients: a retrospective study. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2020;17:3809. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17113809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bajaj J.S., Fagan A., Sikaroodi M., et al. Liver transplant modulates gut microbial dysbiosis and cognitive function in cirrhosis. Liver Transplant. 2017;23:907–914. doi: 10.1002/lt.24754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.ISRCTN - ISRCTN62619436: Prevention of infection in patients with cirrhosis with probiotic Lactobacillus casei Shirota.doi:10.1186/ISRCTN62619436.

- 49.Mittal V.V., Sharma B.C., Sharma P., Sarin S.K. A randomized controlled trial comparing lactulose, probiotics, and L-ornithine L-aspartate in treatment of minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:725–732. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32834696f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Román E., Nieto J.C., Gely C., et al. Effect of a multistrain probiotic on cognitive function and risk of falls in patients with cirrhosis: a randomized trial. Hepatology Commun. 2019;3:632–645. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Macnaughtan J., Figorilli F., García-López E., et al. A double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial of probiotic lactobacillus casei shirota in stable cirrhotic patients. Nutrients. 2020;12:1651. doi: 10.3390/nu12061651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lazebnik L.B., Golovanova E.V., Slupskaia V.A., Trubitsina I.E., Kniazev O.V., Shaposhnikova N.A. [Realities and prospects for the use of cell technologies for the treatment of chronic diffuse liver diseases] Eksp Klin Gastroenterol. 2011:3–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Salama H., Zekri A.R.N., Ahmed R., et al. Assessment of health-related quality of life in patients receiving stem cell therapy for end-stage liver disease: an Egyptian study. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2012;3:49. doi: 10.1186/scrt140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mohamadnejad M., Alimoghaddam K., Mohyeddin-Bonab M., et al. Phase 1 trial of autologous bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis. Arch Iran Med. 2007;10:459–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Prasad S., Dhiman R.K., Duseja A., Chawla Y.K., Sharma A., Agarwal R. Lactulose improves cognitive functions and health-related quality of life in patients with cirrhosis who have minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatology. 2007;45:549–559. doi: 10.1002/hep.21533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sanyal A., Younossi Z.M., Bass N.M., et al. Randomised clinical trial: rifaximin improves health-related quality of life in cirrhotic patients with hepatic encephalopathy - a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:853–861. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sato S., Namisaki T., Furukawa M., et al. Effect of L-carnitine on health-related quality of life in patients with liver cirrhosis. Biomed Rep. 2020;13:65. doi: 10.3892/br.2020.1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yoon E.L., Ahn S.B., Jun D.W., et al. Effect of L-carnitine on quality of life in covert hepatic encephalopathy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Korean J Intern Med (Engl Ed) 2022;37:757–767. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2021.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bajaj J.S., Ellwood M., Ainger T., et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction therapy improves patient and caregiver-reported outcomes in cirrhosis. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2017;8:e108. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2017.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rakoski M.O., McCammon R.J., Piette J.D., et al. Burden of cirrhosis on older Americans and their families: analysis of the health and retirement study. Hepatology. 2012;55:184–191. doi: 10.1002/hep.24616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lai J.C., Rahimi R.S., Verna E.C., et al. Frailty associated with waitlist mortality independent of ascites and hepatic encephalopathy in a multicenter study. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:1675–1682. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Volk M.L. Burden of cirrhosis on patients and caregivers. Hepatol Commun. 2020;4:1107–1111. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nguyen D.L., Chao D., Ma G., Morgan T. Quality of life and factors predictive of burden among primary caregivers of chronic liver disease patients. Ann Gastroenterol. 2015;28:124–129. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bajaj J.S., Wade J.B., Gibson D.P., et al. The multi-dimensional burden of cirrhosis and hepatic encephalopathy on patients and caregivers. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1646–1653. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Miyazaki E.T., Dos Santos R., Miyazaki M.C., et al. Patients on the waiting list for liver transplantation: caregiver burden and stress. Liver Transplant. 2010;16:1164–1168. doi: 10.1002/lt.22130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rogal S.S., Beste L.A., Youk A., et al. Characteristics of opioid prescriptions to Veterans with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:1165–1174.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dwyer J.P., Jayasekera C., Nicoll A. Analgesia for the cirrhotic patient: a literature review and recommendations. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:1356–1360. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Krčevski Škvarč N., Morlion B., Vowles K.E., et al. European clinical practice recommendations on opioids for chronic noncancer pain - Part 2: special situations. Eur J Pain. 2021;25:969–985. doi: 10.1002/ejp.1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tegeder I., Lötsch J., Geisslinger G. Pharmacokinetics of opioids in liver disease. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1999;37:17–40. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199937010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pate J., Gutierrez J.A., Frenette C.T., et al. Practical strategies for pruritus management in the obeticholic acid-treated patient with PBC: proceedings from the 2018 expert panel. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2019;6 doi: 10.1136/bmjgast-2018-000256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rogal S.S., Hansen L., Patel A., et al. AASLD Practice Guidance: palliative care and symptom-based management in decompensated cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2022;76:819–853. doi: 10.1002/hep.32378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Eusebio-Alpapara K.M.V., Castillo R.L., Dofitas B.L. Gabapentin for uremic pruritus: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:412–422. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Baskol M., Ozbakir O., Coşkun R., Baskol G., Saraymen R., Yucesoy M. The role of serum zinc and other factors on the prevalence of muscle cramps in non-alcoholic cirrhotic patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:524–529. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000129059.69524.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tapper E.B., Salim N., Baki J., et al. Pickle juice intervention for cirrhotic cramps reduction: the PICCLES randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117:895–901. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Angeli P., Albino G., Carraro P., et al. Cirrhosis and muscle cramps: evidence of a causal relationship. Hepatology. 1996;23:264–273. doi: 10.1002/hep.510230211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ghabril M., Jackson M., Gotur R., et al. Most individuals with advanced cirrhosis have sleep disturbances, which are associated with poor quality of life. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1271–1278.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rajpurohit S., Musunuri B., Null Shailesh, Basthi Mohan P., Shetty S. Novel drugs for the management of hepatic encephalopathy: still a long journey to travel. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2022;12:1200–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2022.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brown J., Sorrell J.H., McClaren J., Creswell J.W. Waiting for a liver transplant. Qual Health Res. 2006;16:119–136. doi: 10.1177/1049732305284011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Martin S.C., Stone A.M., Scott A.M., Brashers D.E. Medical, personal, and social forms of uncertainty across the transplantation trajectory. Qual Health Res. 2010;20:182–196. doi: 10.1177/1049732309356284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Walling A.M., Asch S.M., Lorenz K.A., Wenger N.S. Impact of consideration of transplantation on end-of-life care for patients during a terminal hospitalization. Transplantation. 2013;95:641–646. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318277f238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Román E., Torrades M.T., Nadal M.J., et al. Randomized pilot study: effects of an exercise programme and leucine supplementation in patients with cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:1966–1975. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang G.S., Yang Y., Li H., et al. Health-related quality of life after liver transplantation: the experience from a single Chinese center. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2012;11:262–266. doi: 10.1016/s1499-3872(12)60158-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mabrouk M., Esmat G., Yosry A., et al. Health-related quality of life in Egyptian patients after liver transplantation. Ann Hepatol. 2012;11:882–890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Duffy J.P., Kao K., Ko C.Y., et al. Long-term patient outcome and quality of life after liver transplantation: analysis of 20-year survivors. Ann Surg. 2010;252:652–661. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181f5f23a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Saleh Z.M., Salim N.E., Nikirk S., Serper M., Tapper E.B. The emotional burden of caregiving for patients with cirrhosis. Hepatol Commun. 2022;6:2827–2835. doi: 10.1002/hep4.2030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]