Abstract

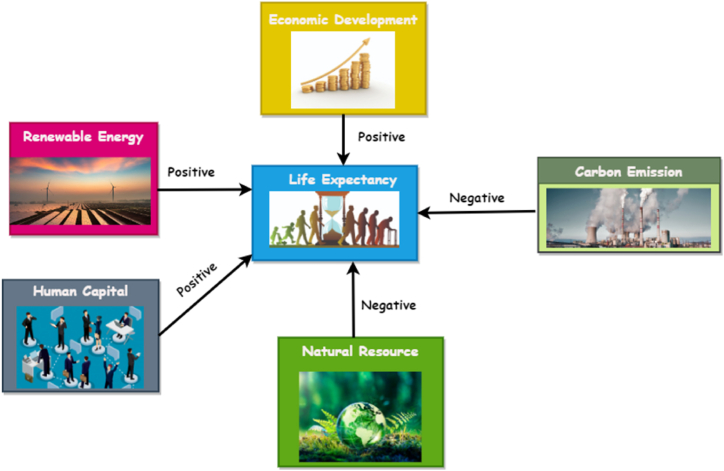

Life expectancy (LEX) has gained relevance among health and environmental scholars due to the current upsurge in carbon emissions. As a result, this article examined the impact of economic development (ECD), air pollution (AIP), human capital (HUC), natural resources (NRR), and renewable energy consumption (REC) on LEX in the MINT countries. The DSK estimation approach was used to estimate the variables’ long-term interaction. The following are the main empirical findings from the analysis. First, the research discovered a positive, significant, and favourable nexus between ECD, HUC, REC, and LEX. Second, AIP and NRR have a detrimental and significant impact on LEX. Third, the causation analysis revealed a one-way link between economic development, renewable energy consumption, and LEX. This empirical research gives policy-makers unique ideas on using human capital, renewable energy, and economic growth as strategic tools to promote life expectancy. Therefore, MINT nations must employ the appropriate strategies to boost economic growth, human capital and renewable energy to improve life expectancy. On the other hand, these countries should enhance natural resource utilization and reduce carbon emissions to achieve a longer lifespan.

Keywords: Air pollution, Economic development, Human capital, Life expectancy, Natural resources, Renewable energy

1. Introduction

Environmental degradation jeopardizes human health, mainly through air pollutants, primarily from fossil fuels, which reduces the average lifespan globally by almost two years [1]. In addition, millions of individuals die from air pollution each year and have shorter life expectancies, raising severe concerns for researchers, think tanks, environmentalists, and global policy-makers. For instance Ref. [2], reported that almost 8 million fatalities globally occur yearly due to breathing contaminated air from burning fossil fuel. This alarming figure represents approximately one in five of all global mortality. Moreover, life expectancy (LEX) is the most crucial indicator of an economy's health status [3]. LEX encompasses mortality across a person's lifespan and details a population's average death rate [4]. A nation's health status is essential in defining LEX, well-being, and overall quality of life among its citizenry [5].

Most economies recently faced the problem of overreliance on traditional power sources. Prior studies have revealed that it causes higher levels of air pollution [6,7]. At the same time, economies around the globe are facing various challenges, such as an ageing population, higher mortality rate and reduction in life span [8,9]. Moreover, most economies in the world face financial inequality, efficient utilization of natural resources, and overreliance on non-renewable energy and human resources, which have an adverse effect on LEX [8]. recounted that rising carbon emission is not only responsible for climate change, upsurge in sea level and global warming but is also associated with problems such as higher mortality rate and morbidity due to air pollution. Likewise [10], espoused that the ensuing impact of carbon emission transcends the destruction of the ecological system to reduce the quality of life. Therefore, the impact of air pollution on LEX needs further research. Hence, the current study explores factors affecting MINT economies’ life expectancy.

Aggregate LEX disparities between and among countries present a significant challenge to international organizations. It has garnered considerable and broader significance due to the growing environmental, political, and economic interest. For instance, a report by the United Nations Development Programme [11] asserted that nations could adopt various actions to improve the quality of their populace even in challenging circumstances. Despite slight GDP growth, many countries have made significant advancements in health and education. In contrast, some countries with long histories of good economic performance have failed to experience the same dramatic improvements in LEX, educational attainment, and general living standards. The United nations launched Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to achieve a healthy lifestyle, well-being, and lifespan by 2030 [12]. The SDGs focus on battling environmental deterioration and ensuring access to renewable energy for every country, in conjunction with economic growth, modernization, and strong institutions. Moreover, SDGs 3, 8, and 15 focus on “well-being and good health,” “economic growth and decent jobs,” and “life on earth,” respectively. These SDGs aim at improving the LEX of humanity. In addition [13], asserted that, in contemporary societies, the length of life or standard of living is crucial; the more advanced a society is, the greater its citizens live. Thus, LEX is among the most substantial health indices influencing human well-being and economic growth.

The relationship between air pollution and life expectancy is well-established and profoundly concerning for scholars, stakeholders and government [14,15]. Prolonged exposure to high levels of air pollution, particularly fine particulate matter and toxic gases like nitrogen dioxide and carbon emission, has been linked to various serious health issues, including respiratory diseases, cardiovascular problems, and even cancers [9,16]. Over time, these health effects can significantly reduce an individual's life expectancy. Additionally, air pollution disproportionately affects vulnerable populations, such as children, the elderly, and those with pre-existing health conditions, further exacerbating health disparities and lowering life expectancy in affected communities [17]. Efforts to reduce air pollution through clean energy transitions, stricter emissions regulations, and urban planning that promotes cleaner transportation options are essential for safeguarding public health and improving overall life expectancy and quality of life. Extant studies have indicated air pollution adversely influences human health and causes a decline in life span [5,5,18,18,19].

The central focus of the study is evaluating the drivers of LEX among Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria, and Turkey (MINT). The MINT bloc was formed in 2011 among these emerging countries with common features such as demographics, large populations, and developing economies [20]. The geographical positioning of these countries is significant for such studies. Thus, Mexico is ideally situated on the borders of Latin America and the United States. Indonesia is positioned in central Asia and is close to rich source nations such as China and Australia. Nigeria is also located in Africa and has rich natural resources [20]. Turkey also sits on the edge of the European Union and serves as the gatekeeper for entry into Africa and Asia. Environmental pollution in the MINT nations has become an increasingly pressing issue in recent years. These rapidly developing economies have experienced significant industrial growth and urbanization, leading to higher levels of pollution across various fronts [21]. Air pollution from industrial emissions and vehicular traffic has led to deteriorating air quality in many urban centres, posing health risks to their populations. Water pollution, often from inadequate waste management and industrial discharge, threatens the MINT nation's freshwater sources and marine ecosystems [22]. Deforestation and land degradation have also strained natural habitats and exacerbated biodiversity loss. While these countries are making efforts to address these challenges through policies and initiatives focused on sustainable development and pollution control, the scale of the problem underscores the urgent need for comprehensive and coordinated environmental strategies to protect the health of their citizens and the planet.

In addition, the pollution level of the MINT nations faces hazards from non-renewable energy consumption and [24] asserted that the wastage in energy production and consumption in the MINT bloc reflected in the rise in carbon emission, rapid draining of energy resources and high cost of energy products. In addition, the over-reliance on conventional energy sources has accounted for about a 7 % rise in global fossil from the MINT region. Hence, the MINT economies are dispersed throughout the continents of the world. The study targeted the MINT countries because, in recent times, these have contributed significantly to global economic growth. For example [23], opined that the MINT countries contribute to almost 2 % of global economic development. In addition, it is predicted these economies will face environmental concerns and depletion of natural resources due to globalization and speedy growth among these countries. Hence, the most crucial question is how the MINT improve their economic growth without causing danger to their citizens’ life expectancy. To answer this question, the current study explores the effect of economic growth, air pollution and natural resources on LEX.

To begin with, prior studies have demonstrated LEX is regarded as an integral health component that affects economic development (ECD) and the well-being of economies [[25], [26], [27]]. An exponential rise in LEX can be linked with an increase in the income of the citizens of a country [26]. demonstrated that an upsurge in ECD reflects an economy with a higher level of LEX. Various economies must consider investment in enhancing social parameters such as food supplies, pension programs, education, and a quality environment for their citizens [5]. claims that a sound healthcare system is essential to ensuring a long-term ECD and sustainable production system. Thus, a strong labour force ensures increased productivity and higher economic per capita income.

In addition, recent environmental scholars have revealed that carbon dioxide emission (CO2) or air pollution (AIP) plays an influential role in determining LEX [5,18,28]. Even though these empirical studies have espoused the effect of ARP on healthcare and LEX, many emerging economies, such as MINT, have not provided decisive efforts and actions against ecological deterioration. These economies have focused on increasing ECD and, as a result, exert enormous pressure on natural resources [29]. highlighted that strong environmental laws have a long-term positive impact on ECD and health, but excessive environmental degradation prevents some countries from realizing this. The AIP caused by the carbon emission phenomenon is a global challenge, and its effect is detrimental to the LEX [30]. [29] revealed that some studies had evaluated the influence of AIP on LEX, particularly from the MINT bloc. Reducing AIP is still a significant issue, warranting further study to determine its specific impact on health [31]. This motivates the researchers of this study to investigate to fill the literature gap.

Given the preceding discourse on the connection between AIP-LEX, it is evident that strategic investment into human capital (HUC) can help improve low LEX [10]. posited that HUC can be used as a strategic mechanism to enhance life expectancy. Thus, the study revealed that persons with greater educational levels have better health and live longer than those with a low level of education. The established theoretical justification for LEX's beneficial impact on ECD relies heavily on the belief that investment in HUC is strengthened by a sound health system [32,33]. Some studies argue that there is a positive connection between HUC and longevity or LEX [10,[34], [35], [36]]. Consequently, the current study explores how HUC influences the level of LEX in MINT countries.

Moreover, one essential variable to consider in such a discussion is energy consumption. In contemporary times, global energy policies have shifted from non-renewable power sources, including gas, oil, and coal, to renewable energy consumption (REC) desired for future energy-related planning [1]. contended that more focus should be emphasized on REC because it dissipates AIP and improves the LEX and people's health. Hence, to sustain higher LEX among the MINT economies, REU and improved environmental health are variables that might play an integral role. Likewise [31], opined that safeguarding the ecology and reducing AIP requires government and private investment in REU and technologies. Investment in REU is a central component of policies designed to achieve a sustainable energy transition in the MINT economies [37].

Moreover [38], reported that it is difficult to overstate the importance of natural resources (NRR) to human existence, the environment, and economic progress. Most economic activities today, including transportation, home appliances, and production, depend heavily on NRR. In environmental literature, much focus has been challenged on the influence of NRR on ECD [[39], [40], [41]], AIP [[42], [43], [44]], with less emphasis on the LEX. Thus, less attention has been focused on the connection between NRR and LEX. Recent empirical data analysis from different jurisdictions has tried to connect NRR dependency to various indices of LEX and health outcomes [45,46]. Accordingly, this study examines the effect of NRR on LEX among the MINT nations. The principal objective of this analysis was to explore the impact of ECD, AIP, HUC, REC, and NRR on LEX in the MINT nations. More specifically, the core aims of this paper are as follows: (1) To determine the role of ECD, AIP, HUC, REC, and NRR on LEX at birth among the MINT economies. (2) To explore and understand the causality connection between the regressors variables and LEX at birth. (3) To provide essential policy measures that can help improve LEX in the MINT countries.

Therefore, to provide a comprehensive understanding of the dynamic connection among the variables, the study applied an econometric approach and provided empirical analysis based on panel data. This study's topic is novel and provides an enormous contribution and practical approach to solving environmental, energy, and health issues. The contributions of this paper to policy-makers and literature are discussed as follows: First, the findings of this study are anticipated to provide stakeholders, policy-makers, and various governments in the MINT bloc with valuable insight and discussion points regarding the effect of ECD, AIP, HUC, REC, and NRR on the longevity or lifespan of citizens in these countries. Second, it is worth noting that scanty analyses have examined how these factors influence LEX in the MINT countries. Moreover, existing studies that have analyzed determinants of LEX have mainly focused on single countries. Thus, the influence of these variables on LEX among the MINT remains unclear. Third, this study provides an empirical outcome that reveals the effect of AIP, REC, and economics on LEX. Nevertheless, previous analysis has overlooked the potencies of these factors on LEX and has not provided conclusive findings on this debate. Fourth, this analysis used the most current estimating methods considering panel data issues like cross-sectional dependence (CSD) and slope homogeneity test (SHT). Moreover, to investigate the stationarity among the study indicators. Finally, thorough assessments are used to corroborate the modelling techniques, providing proof of long-term correlations between the variables and producing useful empirical findings that are highly plausible for policy implications.

2. Literature review

2.1. Economic growth and life expectancy nexus

The economic progress of developed or emerging regions aims to set out policies to improve the wellness of its communities. This is corroborated in the investigation of [25] in Indonesia on the affiliation between economic growth and life expectancy. The results from the data analysis illustrated that ECD and LEX had a favourable material connection. In addition, the study's findings found a short-term unidirectional causality between ECD and LEX. The cointegration outcome revealed a long-term connection between economic growth, air pollution and LEX. Likewise, employing the Bayesian model in 134 nations [27], explored the spatiotemporal level of LEX and ECD. The findings exhibited that the lower communities in Africa and South-East Asia regions had poor economic progress, leading to low life expectancy. Practically, the study proposes that governments, as a matter of urgency, should outline public policies to enhance air quality and dissipate the health ramifications caused by AIP [47]. recent investigation on the top five carbon emission regions for 1975–2015. The results from the cointegration analysis depicted that Russia and Japan had the weakest nexus between economic progress and mortality and LEX. The theoretical assumption supporting this study outcome is that there is a low mortality rate and vaccine coverage is high, contributing to the overall improved lifespan. Moreover, Japan, for instance, has initiated various approaches and programs to enhance its citizenry's public health and well-being. These policies include universal healthcare coverage captured under the National Health Insurance system. The government has also invested in preventive health care measures, including promoting and educating about healthy eating habits and physical activities, which are likely contributing to improving LEX. Adding to the literary work on economic development and life expectancy [26], examined the ASENA communities with the ARDL bounds test approach. The findings confirmed that economic progress significantly influenced life expectancy in the short run. Concluding on research in emerging states on panel data from 1992 to 2017 [28], elaborated on the affiliation between economic progress and life expectancy. The results from the ARDL model demonstrated that economic progress, health spending, and population ageing had a favourable material link to life expectancy. The study further espoused that nations need to consider increasing their expenditure on the health industry to improve the longevity of their citizens.

2.2. Human capital and life expectancy nexus

The nexus between human capital and life expectancy is not a new field for researchers. From an empirical perspective, the literature has reported mixed findings on the relationship between HUC-EXP. For instance, some studies argue that there is a positive connection between HUC and longevity or LEX [10,[34], [35], [36]]. [48] elaborated on the human capital progress and life expectancy of 19 MENA regions. They analyzed data sets from 1980 to 2020 with the feasible GLS model. The findings demonstrated that LEX was the most material factor for human capital progress. Their studies further highlighted that if primary education or human capital is prioritized with the required funding, it can help reduce the inequality gap and improve the quality of life. In addition, improving HUC can increase people's productive capabilities and economic opportunities, ultimately enhancing living conditions and LEX. Likewise [49], explored panel data of BRICS nations on HUC, innovation, and quality of health. Their conclusions indicated that appreciation of human capital and innovation positively affects LEX. Their result further indicated that HUC investment raises information and awareness about people's well-being, which in return helps improve the level of LEX. In addition, the HUC theory forecasts a longer LEX because human capital is an essential input of the health outcome. Human LEX can rise due to developments in cleanliness, inexpensive housing, HUC, medicine, and efficient use of these resources. In this regard, it is noted that individual health improvements are now possible thanks to technology advancements, which contribute to an increase in life expectancy. The level and percentage of LEX have increased to at least 70 years in several nations. Better diet, better healthcare facilities, improved public health, and—most importantly—technical breakthroughs are all responsible for these notable gains [49]. Adding to an association between the indicators [35], studied 141 developed and emerging economic human capital progress. The results revealed that HUC could positively link LEX in developing regions. This phenomenon can be explained by the fact that in advanced countries, where life expectancies are already higher, a sizable elderly population is becoming a drag on economic growth, or that these nations have attained an optimum level of higher life expectancies where investing more in extending them will divert resources from other crucial sectors. Other previous articles have shown a significant affiliation between the variables [36,49,50].

2.3. Air pollution and life expectancy nexus

With the rapid increase in production and consumption of fossil fuel, the emission output continues to depreciate the life and health of nations. In West Africa [51], investigated Nigeria's air pollution and life expectancy for the quarters 1981Q1 – 2019Q4. The research employed different econometric models and the granger causality test. The findings illustrated a unidirectional interplay between air pollution and LEX. The article recommended governments in rich resource nations should make environmental policies. More specifically, their research indicated that nations should apply a more stringent anti-air pollution mechanism that would lead to higher LEX. In addition, HUC, in the form of education, should be considered an efficient strategic tool to improve LEX. In the United States [52], collected data from three States on older adults. The empirical results depicted that the observed population of 3000–5000 has a 0.1 % depreciation LEX. Likewise [53], Hong Kong developed an econometric model of 8.5 million years of life lost. The results of the non-linear approach depicted that PM2.5 accounted for 5.2%. The article concluded that appropriate policies could increase women's LEX to 64 or 65 years. Moreover [10], explored the connection between carbon emission and LEX among some selected Africa countries. The study employed panel data from 1980 to 2019, and the CCEMG approach was employed as the estimation technique. The empirical outcome concluded that fossil energy and AIP reduce LEX. The reason for this outcome was supported by the fact that in Africa, a report by the WHO indicated that approximately 2.2 million fatalities are connected to environmental-related illnesses. Furthermore [29], investigated the determinants of LEX among the most polluted countries worldwide. Their research revealed that AIP in the form of carbon emission inversely affect LEX. The inference from their outcome highlighted that outdoor AIP causes several chronic illnesses that increase the death rate in these nations. Their study is averse that air quality adversely affects the lifespan of older citizens, especially those suffering from comorbidities [54]. also empirically tested the long-run effect of greenhouse gas, carbon emission, methane and global warming on LEX. Their research used panel data from 1990 to 2016 and employed the generalized linear model. The findings from the study indicated that greenhouse gas, carbon emission, methane and global warming have a detrimental influence on lifespan in Pakistan.

2.4. Renewable energy and life expectancy nexus

REC has become the alternative for non-REC to reduce emissions to achieve a low carbon emission target by 2050. In a more affiliated investigation to the current research [31], investigated panel data of 29 European communities from 2005 to 2018. The empirical model analysis demonstrated that NOx, PM10, and PM2.5 had an inverse affiliation with LEX at birth. The outcome of their study espoused that investment in REC substantially influences health production, thereby improving the potential of LEX. This finding provided policy-makers and the government the opportunity to encourage the expansion of renewable energy projects, which has a long-lasting solution to improve the environment. However, renewable energy has a positive association with life expectancy. Using a global panel dataset [19], elaborated on 155 renewable energy and health regions. The findings show that REC causes an appreciation in LEX. Also, health and mortality were improved with cleaner energies. A possible explanation for their research outcome can allude to the fact that substituting traditional energy sources with green technologies enhances ecological Sustainability through the dissipation of carbon emissions. Hence, the loss of life and spread of air-borne diseases can be reduced through calculated investment in REC. Furthering the research context in China [55], explored the affiliation between health cost, renewable energy, and life expectancy. The econometric model of VECM was employed to analyze the dataset from 2000Q1 up to 2020Q4. The findings exhibited that investment in health and renewable energy appreciated the life expectancy in China.

2.5. Natural resource rent and life expectancy nexus

The global economy is diligently trying to preserve the Sustainability of the ecosystem in the face of several contaminants that threaten its safety and the peaceful coexistence of humanity [45]. assessed the non-linear affiliation between the exits between NRR and LEX for the period 1990–2011. The study adopts the fixed effect and panel-corrected standard errors approach. The results demonstrated a fishhook-like nexus between the NRR and LEX. In a cross-country panel investigation for 1970–2015 [15], they explored NRR and LEX at birth and proxying NRR as a global commodity price. The results indicated a 6.72% appreciation in NRR leads to 2.01%. The most regions with the effects were in the Sub-Saharan African communities. Likewise [38], conducted studies on NRR and longevity of selected African communities from 1980 to 2019. The findings demonstrated that coal, gas, and fossil fuels negatively influenced longevity. Happiness and resource cure were investigated by Ref. [56] with a dataset of 149 nations. The empirical results elaborated that natural resource rent hinders happiness and life expectancy. Similarly, resources such as gas and oil were high but lower in resource rent like the forest. The current research contributes to the literature by employing yearly time series from 1990 to 2020 to investigate how ECD, REC, NRR, HUC, and AIP affect life expectancy among the MINT countries. Thus, the literature reviewed so far has demonstrated that fewer studies have analyzed the determinant of LEX among the MINT nations. Therefore, the study's findings will contribute significantly to the environment-energy-economic literature. The empirical evidence outlined in this research has crucial policy implications that government, scholars and environmental scientists can follow to help improve LEX in the MINT and other emerging countries.

3. Data and methods

3.1. Theoretical background

The theoretical underpinning of the study focused on the human capital theory opined by Ref. [57], which suggested that strategic HUC investment helps promote a healthy economy and improves the lives of a society [1,32]. The study further elaborated this assumption by Ref. [58] healthcare model. The notion of this theory lies in the fact that health is regarded as a sustainable capital that produces an output of LEX of a nation's population. In this scenario, the formation of HUC can be linked to various significant components that may be considered an integral aspect of LEX or human health status [29]. These elements may include air pollution, economic development, renewable energy, and government expenditure on health-related matters. Hence, envisioning the [57,58] health models, this paper identifies these variables as a catalyst that can influence LEX among the MINT nations. Accordingly, the rationale for selecting the variables under examination in this study is supported by the previous studies and the availability of sufficient data. The indicator for LEX at birth was selected based on the analysis by Refs. [5,27,29]; ECD [[25], [26], [27]]; HUC [36,49,50]; AIP [10,29,54]; REC [31,59,60] and NRR [38,45]. Following these prior studies, equation (1) will be used to determine the function of the antecedents of LEX.

| (1) |

Such that Equation (1) outlines the mathematical function of the connection between economic development (ECD), human capital (HUC), air pollution (AIP), renewable energy consumption (REC), natural resource (NRR), and Life expectancy (LEX). As suggested by prior studies, representing the variables in their logarithm forms helps to overcome heteroscedasticity and helps produce accurate estimates among the panel data set [22,61]. To overcome challenges with small data observation, the study used the quadratic match-sum method to adjust the yearly frequency data to logarithm form. This approach helped improve the data quality and normalized it for efficient analysis. The logarithm method is favoured over other interpolation techniques because it considers the data structure's seasonality when it changes from low to high frequencies [62]. Hence, the logarithm function among the variables has been presented in equation (2).

| (2) |

where identifies the constant of the function, and the coefficient of the regressors is indicated with the terms . The function's coefficients show how much the outcome variable has changed concerning the independent factors. The term depicts the logarithm structure for the variable, and refers to the error term of the function. Also, illustrates the MINT nations, and identifies the timeframe for the research.

3.2. Data source and management

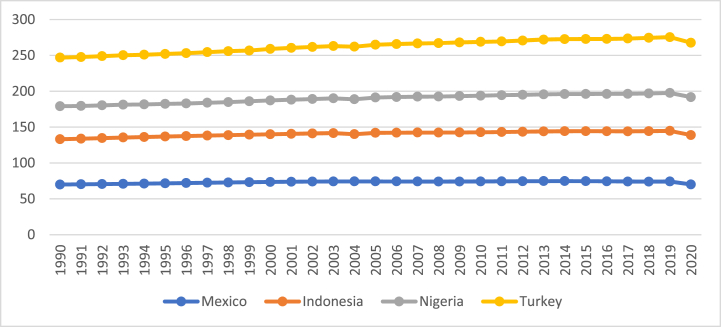

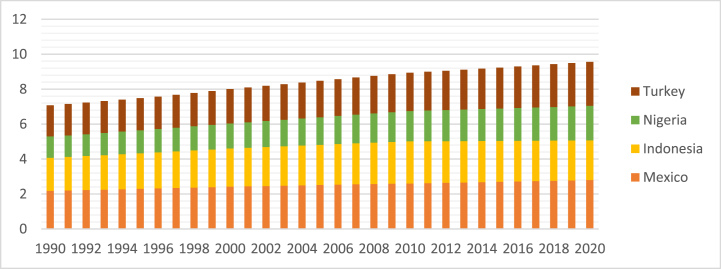

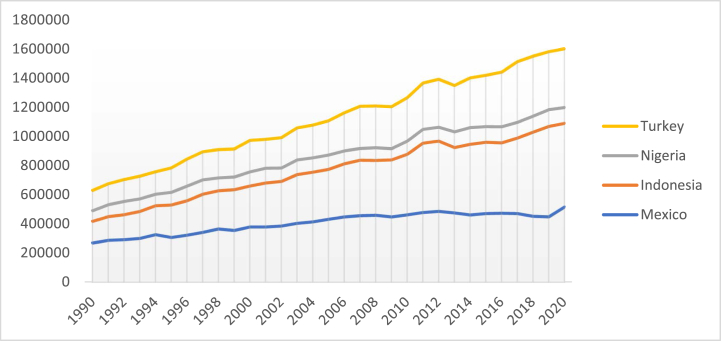

The research explored data from 1990 to 2020 for all the MINT nations (Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria, and Turkey). The study period was selected based on data availability for these countries. The graphical representation of the various indicators explored in this study is illustrated in Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6. The reason for selecting the MINT nations for this research is that, as indicated in Fig. 4, there is an upsurge in carbon emissions for all the MINT countries. Moreover, the data analysis revealed that there had been an ascending trend in terms of economic growth, natural resources, renewable energy and human capital development but with increasing levels of carbon emission. According to a survey by Ref. [63], air pollution kills almost 33,000 Mexicans yearly. Thus, nearly 20,000 of these mortalities result from higher pollution in major cities and the remaining 13,000 are from pollutants caused by households, cooking with wood and other solid fuel.

Fig. 1.

Trend assessment of life expectancy in the MINT economies.

Fig. 2.

Trend assessment of economic development in the MINT economies.

Fig. 3.

Trend assessment of human capital development in the MINT economies.

Fig. 4.

Trend assessment of air pollution (CO2) in the MINT economies.

Fig. 5.

Trend assessment of natural resources in the MINT economies.

Fig. 6.

Trend assessment of renewable energy in the MINT economies.

In addition, a recent report by Ref. [64] indicated that in Nigeria, there was a high death rate of more than 60,000 in 2019 among children under five years due to air pollution-related pneumonia. The report further asserted that most air pollution emanated from open fires or cookstoves used for household activities. Similarly, in Turkey, as it stands now, the issue of air pollution has become a prominent topic among stakeholders and various government agencies. The country has witnessed almost 30,000 fatalities as a result of air pollution, and this percentage contributes to almost 8 % of all mortalities nationwide [65]. Lastly, in Indonesia, the research by Ref. [61] revealed that the average Indonesia can anticipate losing 2.5 years of LEX at the recent pollution levels because the air quality fails to meet the WHO guideline for a concentration of delicate particulate matter. The discussion so far has provided an overview of the effect of air pollution on LEX among all the MINT nations. These arguments provide a strong foundation for selecting these countries in this paper. LEX estimates longevity at birth in total years and is used to gauge each nation's health status. This has been recognized as a prevalent and reliable indicator of overall health [66]. A summary explanation of all the variables and sources of data is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of variables.

| Series | Symbols | Variable Description | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Life Expectancy | LEX | LEX indicated the expected lifespan at birth (Total years) | [73] |

| Economic Development | ECD | EXP indicates the per capita income based on (constant USD 2015) | [73] |

| Renewable Energy Consumption | REC | REC indicates solar, geothermal, biomass, wind, and other renewable power supply (TWh) | [74] |

| Human Capital | HUC | HUC measures the aggregation of education, health, and better living standards of people (Index) | [75] |

| Air Pollution | AIP | CO2 was used as a proxy for air pollution (metric per capita) | [73] |

| Natural Resource | NRR | NRR estimates Natural resource rent % GDP | [73] |

Note: WID: World Development Indicators, UNDP: United Nations Development, OECD: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Programme, TWh: Terawatt hour.

LEX is a vital measure that reflects the average years a person can expect to live based on various factors such as birth year, gender, and socioeconomic conditions. It is a critical indicator of a society's health and well-being [5,67]. Over the past century, life expectancy has seen remarkable improvements, primarily due to healthcare, sanitation, and nutrition advancements. These gains have contributed to longer, healthier lives for individuals across the globe [68]. However, disparities in life expectancy still exist, with significant variations between regions and populations. Efforts to further increase life expectancy involve addressing these disparities, promoting healthy lifestyles, and continually advancing medical and technological innovations to ensure that people can live longer and enjoy a higher quality of life as they age.

Air pollution measured in terms of carbon emissions is a critical lens through which we can understand today's environmental and health challenges. Carbon emissions from burning fossil fuels in transportation, industry, and energy production contribute significantly to the atmospheric pollutants that degrade air quality [69]. These emissions release harmful compounds like particulate matter, sulphur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and volatile organic compounds, which pose serious health risks to humans, including respiratory problems, cardiovascular diseases, and even premature death [70]. Moreover, carbon emissions are a leading driver of climate change, with far-reaching consequences such as rising temperatures, extreme weather events, and disrupted ecosystems [71]. Addressing air pollution through reducing carbon emissions is essential for protecting human health, mitigating the global climate crisis, and ensuring a sustainable and cleaner environment for future generations [72]. Climate change, fuelled by carbon emissions, brings about extreme weather events, food and water shortages, and the spread of diseases, further threatening life expectancy. Therefore, addressing carbon emissions and transitioning towards cleaner, sustainable energy sources benefits the environment and plays a crucial role in promoting longer and healthier lives for current and future generations.

3.3. Descriptive assessment of study variables

The descriptive qualities of the variables investigated in the study are presented in the first section of Table 2. The findings from that study revealed that the MINT economies have an average LEX of 65.697. In addition, other indicators such as ECD (26.952), REC (3.050), HUC (0.723), AIP (12.371), and NRR (1.189), respectively. With regards to the standard deviation, the outcome highlighted LEX (3.240), ECD (0.595), AIP (0.624), HUC (0.202), REC (0.365), and NRR (1.426) accordingly. The results proved that AIP and NRR are inversely correlated with LEX, while ECD, HUC, and REC are positively connected to LEX. The last aspect of Table 3 provides the coefficient for the variance inflation factor (VIF). The VIF assessment was tested to evaluate the multicollinearity issues among the series. The VIF analysis also discovered that all the series had VIFs lower than the specified cut-off threshold 10 [6]. This finding demonstrates that multicollinearity is unrelated to the variables being investigated. In addition, the study presented significant statistics on all the indicators. When conducting experiments or analyzing data, researchers calculate statistical tests, often p-values, to assess the significance of their findings. As outlined in Table 2, the findings indicated that all the variables were significant at 1 %. Additionally, Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6 shows the graphical trend for each series among the MINT economies.

Table 2.

Descriptive analysis, correlation, and VIF.

| Variables | LEX | ECD | AIP | HUC | REC | NRR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 65.697 | 26.952 | 12.371 | 0.723 | 3.050 | 1.189 |

| Median | 69.571 | 26.959 | 12.570 | 0.780 | 3.042 | 1.595 |

| Maximum | 77.832 | 27.858 | 13.337 | 1.028 | 3.832 | 3.458 |

| Minimum | 45.487 | 25.689 | 11.195 | 0.198 | 2.339 | 1.968 |

| Std. Dev. | 3.240 | 0.595 | 0.624 | 0.202 | 0.365 | 1.426 |

| Skewness | −0.909 | −0.488 | −0.431 | −0.882 | 0.243 | −0.625 |

| Kurtosis | 19.704 | 2.395 | 1.774 | 3.128 | 2.289 | 2.228 |

| Jarque-Bera | 0.000 | 6.808 | 11.614 | 16.182 | 3.836 | 11.148 |

| Probability | 0.000*** | 0.033*** | 0.003*** | 0.000*** | 0.000*** | 0.000*** |

| Observations | 124 | 124 | 124 | 124 | 124 | 124 |

| Correlation Test | ||||||

| LEX | 1 | |||||

| ECD | 0.625*** | 1 | ||||

| AIP | 0.831 | −0.344*** | 1 | |||

| HUC | 0.807 | 0.244 | 0.791*** | 1 | ||

| REC | 0.876 | 0.306 | 0.885 | 0.951*** | 1 | |

| NRR | −0.292 | −0.340 | −0.553 | −0.551 | −0.601 | 1 |

| VIF Analysis | ||||||

| VIF | 1/VIF | |||||

| LEX | 2.877 | 0.347 | ||||

| ECD | 3.952 | 0.253 | ||||

| AIP | 2.601 | 0.384 | ||||

| HUC | 4.881 | 0.204 | ||||

| REC | 3.342 | 0.299 | ||||

| NRR | 4.792 | 0.208 | ||||

Note: *** implies a 1 % significance level, LEX: Life expectancy, ECD: economic development, HUC: Human capital, AIP: Air Pollution, REC: Renewable Energy Consumption, NRR: Natural Resource.

Table 3.

Results of CSD and SHT test.

| Variables | Bias-Corrected Scaled LM | Pesaran scaled LM | Breusch-Pagan LM | Pesaran CD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LnLEX | 37.020*** | 37.087*** | 134.475*** | 11.454*** |

| LnECD | 48.939*** | 49.004*** | 175.757*** | 13.256*** |

| LnAIP | 33.499*** | 33.566*** | 122.276*** | 10.816*** |

| LnHUC | 45.000*** | 45.078*** | 162.118*** | 12.701*** |

| LnREC | 22.917*** | 22.984*** | 85.620*** | 9.184*** |

| LnNRR | 33.648*** | 33.714*** | 145.581*** | 8.845*** |

| SHT test | ||||

| 12.689*** | ||||

| 13.355*** | ||||

Note: *** implies a 1 % significance level, LEX: Life expectancy, ECD: economic development, HUC: Human capital, AIP: Air Pollution, REC: Renewable Energy Consumption, NRR: Natural Resource.

3.4. Econometrics approach

3.4.1. CSD and SHT

The validation of stationarity and cointegration among the series is essential in panel data estimation analysis. Hence, the testing of the CSD and SHT helps solve this challenge. In addition, panel data problems are easier to recognize and fix when using CSD and SHT because of overlapping residual interrelatedness, unexplained components, and spatial distribution that may exist among the research variables [76]. Equation (4) provides the general mathematical function for the CSD. The mathematical expression for the [77] -LM is provided in equation (3).

| (3) |

The CSD test by Ref. [78]-scaled LM is represented in equation (4) as:

| (4) |

Another CSD test suggested by Ref. [78] CSD, which is applied in which the time frame is less than the size of the cross-sections, is mathematically expressed in equation (5).

| (5) |

similarly, the study applied the newest CSD test proposed by Ref. [79], which is presented in equation (6).

| (6) |

Where, signifies the determination from the ordinary least square for i and j countries (MINT bloc). N implies the study period, and T determines the cross-section. The null hypothesis suggests “no CSD” among the study variables, while the alternate hypothesis considers the existence of CSD in the panel data.

Aside from testing the CSD, the study applied [80] to test SHT. Equations (7), (8)) outline the method for estimating the SHT.

| (7) |

| (8) |

such that SHT indicates the delta of the SHT and represents the adjusted SHT.

3.4.2. Panel stationarity test

The two most recent second-generational stationarity strategies proposed by Ref. [78], which comprised CADF and CIPS, were applied to explore the stationarity among the parameters. When analyzing and resolving the CSD abnormalities in the panel dataset, these stationarity methods perform better than the traditional methods [72,81,82]. Furthermore, relative to first-generation unit root tests, it has been demonstrated in prior erstwhile studies that these stationary approaches produce reliable and robust estimates [76,81]. In equations (9), (10)), computations for both assessments are given.

| (9) |

Such that determines the disparities between the variables, refers to the series investigated in this paper.

| (10) |

Such that represents the study period, implies the cross sections.

3.4.3. Cointegration test

The multivariate cointegration procedure proposed by Ref. [83] was utilized in the study, which offers precise and effective calculations while considering the cross-section drawback. This cointegration mechanism has the main advantage of reducing and controlling the SHT and CSD restrictions in the study model. In addition [57], cointegration specifies four different testing modalities, including the panel examination test ) and the group evaluation test . Equations (11), (12), (13), (14)) show the statistical foundation for these tests.

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

| (14) |

where, Indicates how speed changes from short to long-term stability.

3.4.4. Long-term estimation approach

The study applied the [84] standard error (DSK) estimation method to assess the long-run correlation among the dataset. The study employed this estimation model based on the following reasons. First, this econometric approach resolves all the challenges that may influence the predictions due to autocorrelation, multicollinearity, and cross-sectional dependence. Second, the DSK technique is a flexible, non-parametric method that accommodates a more significant time period and can deal with missing values [1]. Third, the DSK method is suitable and appropriate for examining balanced and unbalanced datasets [85]. Fourth, extant studies have demonstrated that the DSK estimation model generates robust, consistent, and correlation estimates [86,87]. Hence, premised on the above explanation, the study used the ordinary least square method to estimate the DSK formulae, presented in equation (15).

| (15) |

where, shows the explanatory variable (LEX), indicates the regressors (ECD, HUC, AIP, REC, and NRR). In addition, refers to the error term of the function. Also, illustrates the MINT nations, and identifies the timeframe for the study.

3.4.5. Robustness assessment

The augmented mean group (AMG)- [88] and commonly correlated effect mean group (CCE-MG)- [89] were employed in the analysis to validate the DKS method's sturdiness and robustness. These methods identify serial correlation non-stationarity, CSD, and SHT like the DKS. Moreover, the AMG and CCE-MG tend to generate accurate estimations. With panel data, these techniques also handle the problems of serial correlation, autocorrelation, and unobserved heterogeneity [61,90].

3.4.6. Causality test analysis

The study evaluated the causative links between the factors using the [91]-D-H causality test. This approach is novel, and earlier studies employed the D-H process to examine the relationships between panel data sets’ causation [92,93]. This D-H approach is mathematically represented in Equation (16).

| (16) |

where m represents the lag structure and determines the autoregressive condition of the regressors.

4. Results and discussions

4.1. Results of CSD and SHT

The results of all four CSD have been summarized in Table 3. The empirical findings of all the CSD assessment approaches significantly reject the null hypothesis of “no CSD” in the panel dataset. The implication of this finding indicates that any change to one nation within the panel would also affect other economies. Likewise, the SHT tests at the bottom of Table 3 reject the null hypothesis of slope homogeneity. Thus, the findings support the existence of SHT among the study variables.

4.2. Results of the stationarity test

This analysis used two (CADF and CIPS) panel unit root test approaches to establish the stationarity connection between LnLEX and LnECD, LnAIP LnHUC LnREC, and LnNRR. The paper verified the stationarity among the series in the first difference phase of the testing process. The findings have been provided in Table 4, and the outcome delineated from the study uncovers that all the parameters are stationary at the order of integration I (1).

Table 4.

Stationarity test outcome.

| Variables | Order of Integration | CADF Level First difference |

CIPS Level First difference |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LnLEX | (1) | −0.390 | −6.677*** | −2.107 | −7.422*** |

| LnECD | (1) | −1.826 | −6.791*** | 0.441 | −6.134*** |

| LnAIP | (1) | −2.537 | −7.873*** | 1.126 | −6.983*** |

| LnHUC | (1) | 1.063 | −5.513*** | −0.467 | −9.701*** |

| LnREC | (1) | 1.212 | −8.927*** | −0.827 | −9.863*** |

| LnNRR | (1) | −0.690 | −10.241*** | −0.676 | −9.660*** |

Note: *** implies a 1 % significance level, LEX: Life expectancy, ECD: economic development, HUC: Human capital, AIP: Air Pollution, REC: Renewable Energy Consumption, NRR: Natural Resource.

4.3. Panel cointegration assessment

Before analyzing the long-term effects of LnLEX and LnECD, LnAIP LnHUC LnREC, and LnNRR on LnLEX, it is critical to determine cointegration in the research model is a possibility. As shown in Table 5, the results demonstrated that the series had long-term cointegration. As a result of this observation, the null hypothesis that “no cointegration” exists should be rejected at a 1 % significance level. Both categories— for group statistics and — for panel analysis were confirmed according to this test. Thus, the study can conclude that the series under investigation are long-term connections.

Table 5.

Outcome of the cointegration test.

| Value | Z-Stats. | Robust P-Stats. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| −3.253 | 1.527 | 0.035 | |

| −8.781*** | 3.008 | 0.000 | |

| −3.548 | 1.236 | 0.712 | |

| −5.341*** | 3.552 | 0.000 |

Note: *** implies a 1 % significance level, LEX: Life expectancy, ECD: economic development, HUC: Human capital, AIP: Air Pollution, REC: Renewable Energy Consumption, NRR: Natural Resource.

4.4. Outcome of the DSK model

The current analysis employed the DSK technique to examine the dynamic influence of economic development, human capital, renewable energy consumption, air pollution, and natural resources on LEX. The findings from the DSK approach for the MINT economics have been provided in Table 6.

Table 6.

Results of the DSK model.

| Variables | Coefficient | Std. Error | Prob |

|---|---|---|---|

| LnECD | 0.302*** | 0.026 | 0.004 |

| LnAIP | −0.343*** | 0.016 | 0.002 |

| LnHUC | 0.709*** | 0.106 | 0.000 |

| LnREC | 0.542*** | 0.057 | 0.000 |

| LnNRR | −0.279*** | 0.047 | 0.001 |

| Constant | 3.927*** | 0.724 | 0.000 |

| Diagnostic Test | |||

| R2 | 0.927 | Jarque Bera test | 8.359 (0.531) |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.917 | Wald test | 211.872 (0.000) |

| F-statistics | 275.281*** | Wooldridge test | 622.080 (0.972) |

| Prob (F-statistics) | 0.000 | ||

Note: *** implies a 1 % significance level, LEX: Life expectancy, ECD: economic development, HUC: Human capital, AIP: Air Pollution, REC: Renewable Energy Consumption, NRR: Natural Resource.

The coefficient estimate of ECD is 0.302, which is substantial and positive at a 1 % significance level, implying that a 1 % upsurge in ECD enhances LEX by 0.302 % in the MINT economies. The inference from this outcome is that improvement in ECD may help the MINT nations’ health sector and government to expand their public health expenditure. Thus, through an increased ECD, governments in these countries can provide health infrastructure, insurance packages, and financial commitments that can result in affordable and accessible healthcare to their citizenry. Through these actions and initiatives, the longevity of people in this region can be stimulated. Another possible explanation for this finding is that an increase in ECD means that the income level of citizens will be on the rise; this can provide financial stability and enable people to pay for proper medical care to remedy specific illnesses and prolong lives [29]. Similar to these results [26], reported that an improvement in income and ECD is essential in making citizens more health-conscious, influencing their living standards, and ultimately improving their LEX. The finding from this analysis complies with the results from erstwhile studies that revealed that ECD positively impacts LEX [[25], [26], [27], [28],94]. However, the outcome contradicts earlier findings demonstrating that ECD negatively affects LEX [[95], [96], [97]].

In addition, the empirical findings from the DSK revealed that AIP measured with CO2 has an inverse nexus with LEX. The finding confirmed that an uprise in AIP by 1 % will lead to a decline in LEX by 0.343 %. The inference from this outcome is that environmental pollution caused by CO2 emissions is detrimental to people's health and shortens LEX. The possible explanation for this outcome is as follows. First, this analysis's results confirm that air pollution continues to be one of the most pervasive components that seriously affect human health. This supports the arguments for why AIP has been declared the most challenging and divisive global problem affecting LEX. Second, the worsening AIP has been connected to severe diseases [98,99]. Third, several environmental degradation factors, such as water and air pollution, have been analytically connected to escalating infection rates and fatalities, risks to people's well-being, and limitations on lifespan, which, by application, derides the achievement of a significant number of the SDGs outlined by the [12]. Therefore, the various dangerous gases emitted in the atmosphere due to carbon emissions continue to be significant barriers to a healthy way of life. The research by Ref. [100] also reported that CO2 is harmful to human health in Ukraine. In addition, it is essential to note that air pollution might increase due to harmful substances such as ash, dust, heavy metals, diesel, chemical products and gasoline produced from transport, combustion, industries and incineration. These harmful substances affect the respiratory system of the individuals. Not taking care can lead to a higher mortality rate, eventually affecting LEX in the MINT nations. The outcome of this study supports several other empirical works that found an inverse interaction between AIP and LEX [10,18,27,31,47,101,102].

One core focus of this analysis is to evaluate the influence of HUC on LEX in the MINT countries. The results from the DSK methodology indicated that HUC significantly and positively impacts LEX. More specifically, a 1 % improvement in HUC causes an improvement in LEX by 0.709 %. This result implies that an upsurge in HUC through training and education causes a positive influence on the LEX of citizens in the MINT economies. Hence, we can deduct from this finding that when individuals are provided with quality education, they have a higher propensity to esteem activities that improve their lives. In addition, this study's findings support the human capital-health models suggested by Refs. [58,103]. Thus, the outcome enriches these theories by demonstrating that HUC is a determinant of LEX. The average LEX can be improved with increased education, environmental awareness, and affordable housing. Moreover, people are becoming more conscious of better health issues, which tend to expand with the advancement and growth of their educational level.

Additionally, education increases people's awareness of various health issues and provides a way to achieve a higher quality of life [104,105]. The overall health problems of individuals can be enhanced through top-notch educational programs geared toward expanding the knowledge and abilities obtained by doctors and other medical professionals. This can be accomplished by extensive investment in infrastructure and services connected to health [49]. Given these arguments, this paper enormously contributes to prior studies and supports the arguments that HUC can positively tilt individual LEX [36,49,50,106].

Furthermore, the empirical results from the DSK model highlighted that REC has a beneficial and significant influence on LEX in the MINT countries. Thus, the findings indicated that a 1 % improvement in REC increases LEX by 0.542 % in these economies. This suggests that renewable energy offers many ecologically beneficial facilities, preventing environmental harm and contributing to a longer life span. This outcome implies that REC is a strategic mechanism to improve LEX. A proportionate rise in cleaner power components, including solar, geothermal, biomass, waves, wind, and ocean currents sources of power, stimulates LEX. Besides, non-REC has adverse health consequences because of CO2 pollution emitted during this energy structure production. This is because every step of the non-REC manufacturing process produces contaminants that jeopardize human life. Several other studies have confirmed a positive connection between these REC-LEX [1,31,59,60]. Nevertheless, these findings do not support these studies’ outcomes [107,108].

Moreover, the empirical findings from the DSK approach disclosed that NRR has an inverse interplay with LEX in the MINT region. Thus, the study outcome revealed that a 1 % rise in the extraction of NRR leads to a decline in LEX by 0.279. Intuitively, the findings suggest that over-exploitation of NRR without proper measures in place among the MINT countries impedes LEX. For example, relying on the usage of conventional and outmoded technology in the extraction of NRR, such as gold, diamond, oil, and timber, could result in the dilapidation of the environment, which could have a detrimental effect on people's lives. Empirical results from Ref. [38] confirmed this viewpoint by suggesting that NRR decreases LEX among countries heavily dependent on NRR, such as gas and fossil fuel. The results of this paper correlate with the findings from these studies [15,67,109].

Lastly, the diagnostic techniques outlined in the paper were the normality test, R-squared and modified R-squared, Jarque Bera test, Wald test, and Wooldridge test. The evaluation method is statistically fit, as indicated by the results of these evaluation tests, highlighting that policy-makers and decision-makers can depend on this research to provide appropriate strategies to expand LEX in the MINT nations.

4.5. Robustness assessment

Table 7 and Fig. 7 demonstrate that the AMG and CCEMG outcome coefficient estimates are consistent with the DSK technique's empirical findings. The results support the study's findings regarding the key elements impacting LEX in the MINT economies.

Table 7.

Result of robustness analysis (CCEMG and AMG model).

| Variables | CCEMG | AMG | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | P-value | Coefficient | P-value | |

| LnECD | 0.709*** | 0.000 | 0.295*** | 0.000 |

| LnAIP | −0.215*** | 0.000 | −0.350*** | 0.000 |

| LnHUC | 0.140*** | 0.001 | 0.067*** | 0.000 |

| LnREC | 0.026*** | 0.000 | 0.744*** | 0.006 |

| LnNRR | −0.062*** | 0.012 | −0.201*** | 0.000 |

| R-squared | 0.916 | |||

| Adjusted r-squared | 0.922 | |||

Note: *** implies a 1 % significance level, LEX: Life expectancy, ECD: economic development, HUC: Human capital, AIP: Air Pollution, REC: Renewable Energy Consumption, NRR: Natural Resource.

Fig. 7.

Graphical representation of the study's outcome.

4.6. Causality analysis

The importance of association provided by the estimation approaches such as DSK, AMG, and CCEMG does not depict the causality relationship among the variables. As a result, to estimate, a causality test must be performed to see whether strategy ramifications established for one macroeconomic measure can affect variability in another. The study explored the causality tests using the D-H approach to estimate the path of causal interactions among the series. Table 8 presents the causality analysis of the paper. The study's findings proved unidirectional causality from ECD, REC, and NRR to LEX. This outcome implies that any policy interventions targeted at ECD, REC, and NRR will have a far-reaching influence on LEX in the selected economies. Moreover, the study findings delineated a bi-directional causality between air pollution, human capital, and longevity. The inference is that any policy strategies outlined by stakeholders regarding AIP and HUC should have an alternative approach to improve LEX since a bidirectional association exists among these indicators.

Table 8.

Results of the D-H Causality test.

| Null Hypothesis | W-stats. | Zbar- Stats. | P-Stats. | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LnECD ⇎ LnLEX | 6.899*** | 3.947 | 0.000 | ECD LEX |

| LnLEX ⇎ LnECD | 2.457 | 0.348 | 0.529 | |

| LnAIP ⇎ LnLEX | 10.573*** | 7.022 | 0.000 | AIP LEX |

| LnLEX ⇎ LnAIP | 5.879*** | 3.109 | 0.000 | |

| LnHUC ⇎ LnLEX | 6.117*** | 3.287 | 0.000 | HUC REC |

| LnLEX ⇎ LnHUC | 5.716*** | 2.953 | 0.000 | |

| LnREC⇎ LnLEX | 6.497*** | 3.611 | 0.000 | REC LEX |

| LnLEX ⇎ LnREC | 2.751 | 0.479 | 0.632 | |

| LnNRR ⇎ LnLEX | 7.126*** | 4.352 | 0.000 | NRR LEX |

| LnLEX ⇎ LnNRR | 1.325 | 0.459 | 0.338 |

Note: *** implies a 1 % level of significance, ⇎ does not granger cause, ⟷ bi-directional and → unidirectional LEX: Life expectancy, ECD: economic development, HUC: Human capital, AIP: Air Pollution, REC: Renewable Energy Consumption, NRR: Natural Resource.

5. Conclusions and policy directions

5.1. Conclusions

The issue of LEX has been significant among health and environmental scholars because of the recent spike in carbon emissions. In addition, as proposed in the SDGs by the [12], these millennium goals focus on improving the Sustainability and longevity of people on earth. As a result, researchers have actively evaluated the drivers and determinants of LEX. Hence, this paper examined the interplay between ECD, AIP, HUC, NRR, and REC on LEX in the MINT economies using a panel data set from 1990 to 2020. The current study applied various econometric approaches to estimate the long-term interaction among the variables. An initial assessment confirmed the presence of CSD, SHT, stationarity, and cointegration among the study parameters. Accordingly, the paper implements the DSK estimation method to estimate the long-term connection between the regressors and LEX. The following are the critical empirical outcomes that emanated from the study. (1) The paper found a beneficial and significant association between ECD, HUC, REC, and LEX in the MINT economies. Thus, ECD, HUC, and REC promote longevity. (2) the effect of AIP and NRR negatively and substantially impedes LEX. (3) The causality assessment illustrated a one-way causality from economic development, REC, and natural resources to LEX. (4) A two-way causality exists between human capital, AIP, and LEX in the MINT countries.

5.2. Policy directions

The policy recommendations based on the findings from the study are highlighted as follows. First, the findings from that study revealed that economic expansion increases life expectancy. Economic prosperity allows economies to build and provide high-quality treatment services, including modern hospitals, cutting-edge medical technology, and efficient medications. Therefore, it is ideal for governments to establish monetary and fiscal strategies as the leading economic tools to improve life expectancy projections for the MINT nations.

Second, the deduction from this study's outcome highlighted that investment in REC positively affects LEX. This outcome has significant policy ramifications for health and environmental measures. As a result, this proposes that the MINT implements legislative measures to promote the deployment and development of REC. The energy structure of these economies should focus more on producing cleaner power sources rather than on non-REC. Moreover, considering that there is a global advocate for the transition to REC, it is prudent for the governments in the selected nations to provide subsidies for organizations that adopt REC in their business operations. Thus, the promotion and expansion of REC can be achieved by diverting the subsidies allocated to traditional power sources to REC to make them accessible and affordable to companies and inhabitants in these countries.

Third, the findings proved that AIP reduces the lifespan of people. This study recommends enforcing these countries’ environmental measures, rules, and regulations. As a practical measure, individuals, companies, or agencies that oppose these environmental measures should be punished accordingly to serve as a deterrent to others. In addition, several other strategies, such as carbon-tax Policy and enforcement of industries to adopt carbon treatment technology. Moreover, incorporating the many global climate agreements (such as the COP26, SDGs, and Paris Agreement) with coordinated efforts to implement them is still crucial to developing a sustainable environment in these countries and achieving carbon neutrality.

Fourth, the results from the research revealed that HUC is an efficient instrument for improving the MINT region's citizens' lifespan. Thus, through education, individuals become aware of environmental challenges and find innovative ways to minimize them. Therefore, this research proposes that governments, policy maker and environmental protection agencies promote (i) educate citizens to build and maintain a cleaner environment in their surroundings, (ii) spread awareness regarding the preservation of the ecosystem through social media platforms, (iii) consumption of green products (iv) initiatives such as green schemes can be devised to promote green initiative among people and (v) promotion of pro-environmental behaviour among citizens.

Moreover, the empirical results demonstrated that NRR inversely affects LEX. Accordingly, this study suggests initiatives, policies, and strategies that discourage people from exploiting NRR without due process. In addition, since most people who exploit these natural resources use traditional and outdated techniques, it is advised that training programs should be organized for local miners and extraction companies. Moreover, government and stakeholders can provide subsidies for cleaner energy sources, step up public awareness campaigns about the risks associated with resource depletion, and launch capital projects that will give people access to increased incomes that will enable them to switch from fossil fuels to REC affordably. From a broader perspective, this research suggests that governments and policy-makers should outline better strategies and policies to promote ecological stability and economic growth simultaneously to improve life expectancy. The improvement in ecological stability and economic growth have proved to enhance the lifespan of people. It is also proposed that countries should invest in cleaner energy sources that generate the most negligible emissions. Companies and government agencies are urged to adopt strategies that improve the use of ecologically friendly machines, equipment and vehicles to reverse and prevent rising air pollution.

5.3. Limitations and future direction

The research is limited by the availability of panel data that spans a more extended period. In additional, the research did not include other factors such as the general living conditions of inhabitants, birth rate, population growth, nutrition, and government expenditure in the research model. Hence, the researcher suggests that future analysis should include other essential determinants of LEX, such as the general living conditions of inhabitants, birth rate, population growth, nutrition, and government expenditure on health services. In addition, future studies could expand the period and data by examining how these factors influence LEX from other jurisdictions, such as the G7 economies, the following 11 countries, or African countries.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Oziegbe Simeon Ebhota: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis. Yao Hongxing: Project administration, Resources, Supervision. Agyemang Kwasi Sampene: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Contributor Information

Oziegbe Simeon Ebhota, Email: simtrice@gmail.com.

Yao Hongxing, Email: hxyao@ujs.edu.cn.

Agyemang Kwasi Sampene, Email: akwasiagyemang91@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Ma M., Alam K. Life expectancy in the ANZUS-BENELUX countries : the role of renewable energy, environmental pollution, economic growth and good governance. Renew. Energy. 2022;190 doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2022.03.135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewis S. research shows - CBS News; 2021. Fossil Fuel Air Pollution Causes Nearly 1 in 5 Deaths Worldwide Each Year.https://www.cbsnews.com/news/fossil-fuel-air-pollution-emissions-1-in-5-deaths-worldwide-each-year/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shahbaz M., Shafiullah M., Mahalik M.K. The dynamics of financial development, globalisation, economic growth and life expectancy in sub-Saharan Africa. Aust. Econ. Pap. 2019;58(4):444–479. doi: 10.1111/1467-8454.12163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roser M., Ortiz-Ospina E., Ritchie H. Our world data; 2013. Life Expectancy. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azam M., Uddin I., Saqib N. The determinants of life expectancy and environmental degradation in Pakistan : evidence from ARDL bounds test approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023:2233–2246. doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-22338-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sampene A.K., Li C., Khan A., Agyeman F.O., Brenya R., Wiredu J. The dynamic nexus between biocapacity, renewable energy, green finance, and ecological footprint: evidence from South Asian economies. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s13762-022-04471-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cai L., Kwasi Sampene A., Khan A., Oteng-Agyeman F., Tu W., Robert B. Does entrepreneur moral reflectiveness matter? Pursing low-carbon emission behavior among SMEs through the relationship between environmental factors, entrepreneur personal concept, and outcome expectations. Sustainability. 2022;14(2):808. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Das S., Debanth A. Impact of CO2 emission on life expectancy in India: an autoregressive distributive lag (ARDL) bound test approach. Futur. Bus. J. 2023;9(1) doi: 10.1186/s43093-022-00179-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aziz G., Waheed R., Sarwar S., Khan M.S. The significance of governance indicators to achieve carbon neutrality: a new insight of life expectancy. Sustain. Times. 2023;15(1):1–20. doi: 10.3390/su15010766. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ibrahim R.L. Beyond COP26: can income level moderate fossil fuels, carbon emissions, and human capital for healthy life expectancy in Africa? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-21872-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.United Nations Development Programme . vol. 21. 2010. http://hdr.undp.org/en/media/HDR_2010_EN_Complete_reprint.pdf (Human Development Report 2010 the Real Wealth of Nations : Pathways to Human Development). [Online]. Available: [Google Scholar]

- 12.United Nations . 2016. Sustainable Development Goals Launch in 2016.https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2015/12/sustainable-development-goals-kick-off-with-start-of-new-year/ [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization . 2014. ‘Ageing Well’ Must Be a Global Priority.https://www.who.int/news/item/06-11-2014--ageing-well-must-be-a-global-priority [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li C., Wu J., Li D., Jiang Y., Wu Y. Study on the correlation between life expectancy and the ecological environment around the cities along the belt and road. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2023;20(3):2147. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20032147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lyatuu I., Loss G., Farnham A., Winkler M.S., Fink G. Short-term effects of national-level natural resource rents on life expectancy: a cross-country panel data analysis. PLoS One. 2021;16(5 May 2021):1–13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0252336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mohmmed A., et al. Driving factors of CO2 emissions and nexus with economic growth, development and human health in the Top Ten emitting countries. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019;148:157–169. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.03.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anu A., Sonia G.L., Ismail K. Effect of climate change on health in older persons. Wits J. Clin. Med. 2023;5(2):79–84. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rjoub H., Odugbesan J.A., Adebayo T.S., Wong W.-K. Investigating the causal relationships among carbon emissions, economic growth, and life expectancy in Turkey: evidence from time and frequency domain causality techniques. Sustainability. 2021;13(5):2924. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Majeed M.T., Luni T., Zaka G. Renewable energy consumption and health outcomes: evidence from global panel data analysis. Pakistan J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 2021;15(1):58–93. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adibe Jideofor. MINT, re-based GDP and poverty: a commentary on the identity crisis in Africa’s “largest” economy. Afr. J. Bus. Econ. Res. 2014;9(1):119–134. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adebayo T.S., Rjoub H., Saint Akadiri S., Oladipupo S.D., Sharif A., Adeshola I. The role of economic complexity in the environmental Kuznets curve of MINT economies: evidence from method of moments quantile regression. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022;29(16):24248–24260. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-17524-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li C., Sampene A.K., Agyeman F.O., Brenya R., Wiredu J. The role of green finance and energy innovation in neutralizing environmental pollution: empirical evidence from the MINT economies. J. Environ. Manag. 2022;317 doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.115500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noshaba Ian, Raza A., Jermsittiparsert K. The role of natural resources, globalization, and renewable energy in testing the EKC hypothesis in MINT countries: new evidence from Method of Moments Quantile Regression approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021;28(11):13454–13468. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-11540-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agbede E.A., Bani Y., Azman-Saini W.N.W., Naseem N.A.M. The impact of energy consumption on environmental quality: empirical evidence from the MINT countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021;28(38):54117–54136. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-14407-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bashir A., Hidayat A. The relationship between air pollution, economic growth, and life expectancy : empirical evidence from Indonesia. Signifikan J. Ilmu Ekon. 2022;11(December 2021):125–144. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hendrawaty E., Shaari M.S., Kesumah F.S.D., Ridzuan A.R. Economic growth, financial development, energy consumption and life expectancy: fresh evidence from ASEAN countries. Int. J. Energy Econ. Pol. 2022;12(2):444–448. doi: 10.32479/ijeep.12670. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang S., Ren Z., Liu X., Yin Q. Spatiotemporal trends in life expectancy and impacts of economic growth and air pollution in 134 countries: a Bayesian modeling study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022;293(December 2021) doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaari M.S., Mariadas P.A., Abidin N.Z. The relationships between CO 2 emissions, economic growth and life Expectancy. J. Asian Finance. Econ. Bus. 2021;8(2):801–808. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mafizur M., Id R., Rana R., Khanam R. Determinants of life expectancy in most polluted countries : exploring the effect of environmental degradation. PLoS One. 2022:1–16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0262802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matthew O.A., et al. Carbon emissions, agricultural output and life expectancy in West Africa. Int. J. Energy Econ. Pol. 2020;10(3):489–496. doi: 10.32479/ijeep.9177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rodriguez-Alvarez A. Air pollution and life expectancy in Europe: does investment in renewable energy matter? Sci. Total Environ. Oct. 2021;792 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Becker G.S. University of Chicago Press; 2009. Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hazan M. Longevity and lifetime labor supply: evidence and implications. Econometrica. 2009;77(6):1829–1863. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hansen C.W. Life expectancy and human capital: evidence from the international epidemiological transition. J. Health Econ. Dec. 2013;32(6):1142–1152. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2013.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sultana T., Dey S.R., Tareque M. Exploring the linkage between human capital and economic growth: a look at 141 developing and developed countries. Econ. Syst. 2022;46(3) doi: 10.1016/j.ecosys.2022.101017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vu T.V. Heal. Econ. (United Kingdom); 2022. Life Expectancy and Human Capital: New Empirical Evidence; pp. 395–412. December 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li C., Kwasi A., Oteng F., Brenya R., Wiredu J. The role of green finance and energy innovation in neutralizing environmental pollution : empirical evidence from the MINT economies. J. Environ. Manag. 2022;317(June) doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.115500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Julius O.O., Lanre R., Bello K. Exploring the dynamic impacts of natural resources and environmental pollution on longevity in resource-dependent African countries : does income level matter. Resour. Policy. 2022;79(June) doi: 10.1016/j.resourpol.2022.102959. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li L. Commodity prices volatility and economic growth: empirical evidence from natural resources industries of China. Resour. Policy. 2023;80 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jie H., Khan I., Alharthi M., Zafar M.W., Saeed A. Sustainable energy policy, socioeconomic development, and ecological footprint: the economic significance of natural resources, population growth, and industrial development. Util. Policy. 2023;81 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu C., Moslehpour M., Tran T.K., Trung L.M., Ou J.P., Tien N.H. Impact of non-renewable energy and natural resources on economic recovery: empirical evidence from selected developing economies. Resour. Policy. 2023;80 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang S.Z., Sadiq M., Chien F. The impact of natural resource rent, financial development, and urbanization on carbon emission. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-16818-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mehmood U., Agyekum E.B., Uhunamure S.E., Shale K., Mariam A. Evaluating the influences of natural resources and ageing people on CO2 emissions in G-11 nations: application of CS-ARDL approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2022;19(3) doi: 10.3390/ijerph19031449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li J., Dong K., Wang K., Dong X. How does natural resource dependence influence carbon emissions? The role of environmental regulation. Resour. Policy. 2023;80 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Madreimov T., Li L. Natural-resource dependence and life expectancy: a non-linear relationship. Sustain. Dev. 2019;27(4):681–691. doi: 10.1002/sd.1932. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gani A. Natural resource effect on child health outcomes in a multifactor health production model in developing countries. Int. J. Soc. Econ. Jan. 2022;49(6):801–817. doi: 10.1108/IJSE-06-2021-0332. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li J., et al. Sustain.; 2023. The Relationship between Energy Consumption, CO 2 Emissions, Economic Growth, and Health Indicators. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adeleye B.N., Bengana I., Boukhelkhal A., Shafiq M.M., Abdulkareem H.K.K. Does human capital tilt the population-economic growth dynamics? Evidence from Middle East and North African countries. Soc. Indic. Res. 2022;162(2):863–883. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hu G., Yao L. Do human capital investment and technological innovation have a permanent effect on population health ? An asymmetric analysis of BRICS economies. Front. Public Heal. 2021;9(July):1–9. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.723557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Adeleye B.N., Osabohien R., Lawal A.I., de Alwis T. Energy use and the role of per capita income on carbon emissions in African countries. PLoS One. 2021;16(11):1–17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0259488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nwani Stanley Emife. Air pollution trajectories and life expectancy in Nigeria. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2022;49(7):1049–1070. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Murray C.J., Lipfert F.W. Air pollution, mortality, at-risk population, new entry and life expectancy of the frail elderly in three US cities. Stud. Non-linear Dyn. Econom. 2021;25(4):135–142. [Google Scholar]