Abstract

Introduction

Sphenoid sinuses, air-filled cavities in the sphenoid bone, develop between the 3rd and 4th year and mature by 12 to 16 years. Understanding their anatomy is vital for safe transsphenoidal surgeries because of nearby vital structures. They exhibit variable pneumatization and often have an intersinus septum. This case emphasizes the importance of understanding sphenoid sinus anatomy, particularly in the context of transsphenoidal surgeries. It also introduces a novel case involving a congenital roof defect, previously unreported in medical literature.

Case presentation

A 52-year-old male presented with left cheek swelling that progressed to the eyelid, accompanied by low visual acuity, nasal symptoms, and a high temperature. Clinical examination revealed purulent discharge. A CT scan indicated opacity in the left maxillary sinus and a roof defect in the left sphenoid sinus. However, endoscopic surgery revealed the sphenoid sinus to be normal. This indicates that the defect is congenital. A biopsy from the maxillary sinus lesion confirmed lymphoma, and he was sent to the oncology hospital. There was no extension of the maxillary sinus lesion into the sphenoid sinus. This unique case had no history of drainage, taste issues, meningitis, or pituitary surgery.

Discussion

The complete absence of the sphenoid sinus roof is a unique and rare anatomical anomaly with significant implications for surgical procedures. Transsphenoidal surgery, which benefits from endoscopic advancements, provides enhanced visualization but also poses risks due to the proximity to critical structures. Pneumatization of the sphenoid sinus typically reaches maturity during adolescence, with individual variations in extent, Septations, extensions, and asymmetry are common in sphenoid sinus anatomy. This underscores the need for surgeon awareness and adjusted surgical approaches in such rare instances.

Conclusions

We emphasize the importance of a thorough anatomical understanding through precise radiological study before any sinus surgery due to the possibility of unexpected anatomical abnormalities.

Keywords: Sphenoid sinus, Anatomical variations, Congenital defect, Absence of roof, Computed tomography (CT) scan, Functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS)

Highlights

-

•

The sphenoid sinuses have great anatomical variation and are unpredictable.

-

•

In our report, we present a case of a previously undescribed case of a sphenoid sinus roof defect.

-

•

We emphasize the role and importance of radiography and radiological studies before any surgical intervention on the sinuses.

-

•

The complete absence of the sphenoid sinus roof presents a potential risk during transsphenoidal surgeries due to the proximity of vital structures.

-

•

Understanding the implications of anatomical variations is crucial in reducing complications during surgical interventions and interpreting imaging results accurately.

1. Introduction

Sphenoid sinuses are air-filled cavities located within the sphenoid bone. They can be identified in the 3rd-4th year of life and typically reach their final shape between 12 and 16 years of age [1]. The sphenoid sinus has important adjacent neurological and vascular structures, such as the internal carotid artery, optic nerve, and pituitary gland. Therefore, a thorough understanding and knowledge of the anatomical variations of the sphenoid sinus are crucial to reduce complications in transsphenoidal surgeries [2]. The sphenoid sinus is considered to be the most variable cavity in the human body and is of great relevance regarding surgical access to the pituitary gland [3]. It has a variable pneumatization pattern, with 86 % well pneumatized (sellar), 11 % pneumatized only to the anterior face of the sella (presellar), and 3 % poorly pneumatized (conchal) [4]. The sphenoid sinuses, both on the right and left sides, are usually divided by a significant intersinus septum. This septum is found in at least 70 % of patients and, in nearly 50 % of cases, extends laterally from the midline [4].

Through our review of medical literature, we observe that despite the significant variation in the anatomy of the sphenoid sinus, most of what is mentioned is limited to variations in pneumatization patterns and the intersinus septum. In this report, we present a case of a man with a congenital defect in the roof of the sphenoid sinus. According to our review of the medical literature, we did not find a similar case.

This work is also reported in line with SCARE criteria which helped to improve the transparency and quality of this case report [5].

2. Case presentation

A 52-year-old male presented at the ENT emergency department with complaints of swelling in his left cheek almost two months ago. The swelling has been gradually increasing and has extended to the left eyelid, with low visual acuity. The patient suffers from nasal symptoms such as a stuffy nose, discharge (sometimes bloody), headaches, and pain in the face in the sinus area. The patient's temperature measures 40 °C, with no other accompanying systemic symptoms present. The patient has no known medical history, no history of medication usage, and no history of surgery. During the clinical examination, purulent discharge was observed in the middle meatus.

The clinical suspicion centered around the patient having sinusitis complications and, to a lesser extent, invasive fungal sinusitis. A computed tomography scan (CT) of the sinuses was performed.

The CT scan showed the presence of opacity in the left maxillary sinus, but what was striking was the presence of a defect in the roof of the left sphenoid sinus with density within it (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

: CT with coronal plane. The defect appears clearly in the roof of the sphenoid sinus.

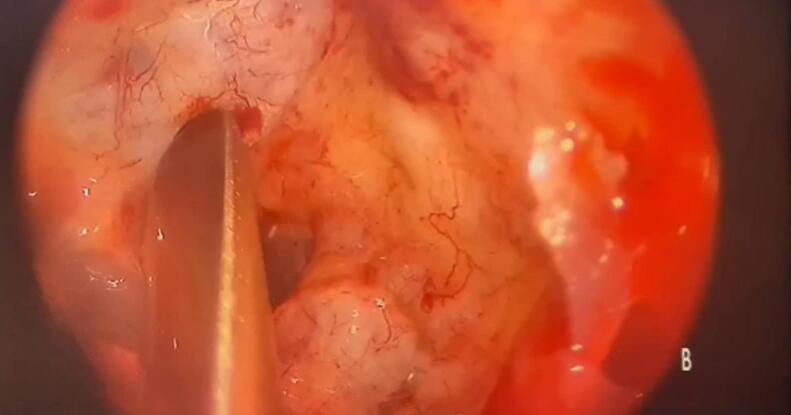

The patient was then prepared for endoscopic sinus surgery and for a biopsy to be performed. During the surgery and after entering the sphenoid sinus, It appeared entirely normal, with no lesions, normal mucosa, and no signs of inflammation. This suggests that the density seen within the sphenoid sinus on the CT scan is, in fact, mucous secretions. Upon careful examination of the site of the defect in the roof of the sinus, only normal mucosa was observed, separating the sinus from the pituitary gland location (site of the bony defect). This was clearly evident when pressure was applied to the defect location (Fig. 2). From this, it can be inferred that this bony defect is congenital.

Fig. 2.

: View during endoscopy. The sphenoid sinus appears with the location of the defect in its roof, where the instrument points.

The surgery was completed, a biopsy was taken from the maxillary sinus lesion, and it was sent for histological examination. The histological results later indicated that the maxillary sinus lesion was a lymphoma. The patient was referred to the oncology hospital for treatment. It is important to note that the patient had no history of drainage from the nose (rhinorrhea), a salty taste in the throat, meningitis, pituitary gland surgery, or endoscopic sinus surgery.

Additionally, it is worth mentioning that the maxillary sinus lesion did not extend into the sphenoid sinus, as indicated by both imaging and endoscopic surgery.

3. Discussion

This case is exceptionally uncommon, as it involves the complete absence of the roof of the sphenoid sinus. Typically, the roof of the sphenoid sinus forms a protective barrier separating it from adjacent important structures. However, in this very rare scenario, the roof is entirely absent, leading to a unique anatomical variation. This anomaly may have significant implications for the patient's surgical procedures.

The sphenoid sinus is located within the sphenoid bone and serves as a separation between the pituitary gland and the nasal cavity. It is surrounded by important neurovascular structures such as the cavernous sinus, internal carotid artery (ICA), and cranial nerves II, III, IV, V, and VI. The development of the sphenoid sinus is congenital, with limited pneumatization in early childhood that reaches its full extent during adolescence [6]. The introduction of endoscopes in trans-sphenoid surgery has greatly improved the surgeon's ability to visualize the surgical field. The use of angled endoscopes provides multidirectional views, allowing for a better understanding of the anatomical relationships between the sella and important structures like the internal carotid arteries (ICAs) and optic nerves. However, there is a potential risk associated with this approach, as the wide opening of the sellar floor can bring the surgeon very close to these vital structures. Therefore, it is crucial to accurately estimate the safety margin when opening the sellar floor, both before and during the surgery. Experience, specialized training, and thorough preoperative planning are essential for the safe and effective use of this technique [7]. Compared to transcranial procedures, trans-sphenoid surgery has lower rates of complications and mortality. The pneumatization of the sphenoid sinuses can be observed as early as 2 years of age on a high-resolution CT scan. Pneumatization progresses in a downward and backward direction. The mature sphenoid sinus typically extends to, but not beyond, the spheno-occipital synchondrosis. By the age of 14, the sinus reaches its full size. The extent of pneumatization can vary greatly. The sella turcica, which appears as a prominence in the roof of a well-pneumatized sphenoid sinus, is an important surgical landmark on the sellar floor [8].

Anatomic variations in the sphenoid sinus are not uncommon and can vary in terms of shape, size, and position.

The sphenoid sinus can be divided into multiple compartments by bony or membranous partitions called septations. These septations can vary in number, size, and location within the sinus. The sinus may have recesses or extensions that project into neighboring structures. For example, the Onodi cell is an extension of the sphenoid sinus that can protrude into the posterior ethmoid air cells or even the optic canal [9]. Furthermore, it can exhibit asymmetry, where one side may be larger or more developed than the other. The degree of pneumatization can vary among individuals. Some may have extensively pneumatized sphenoid sinuses, while others may have less pneumatization [9].

The study conducted by Orhan et al. investigated the absence of sphenoidal sinuses (SS) in adult cadavers, focusing on the agenesis of various sinuses including the sphenoid, maxillary, ethmoid, and frontal sinuses. The researchers observed that the SS were missing bilaterally in a 50-year-old male cadaver. Instead of the usual SS Openings on the lateral wall of the nasal cavity. They found multiple small mucosal grooves between the sphenoidal rostrum and the superior nasal turbinates. However, there was no absence of other paranasal sinuses. The authors emphasize the importance for surgeons to be aware of the possibility of sphenoidal agenesis when performing transsphenoidal hypophysectomy, as it may impact surgical planning and approach. This condition is considered rare and may require additional considerations during the procedure [10].

4. Conclusions

It is important to note that anatomic variations can have clinical significance, as they may impact surgical procedures, imaging interpretation, and the management of sphenoid sinus-related conditions. We emphasize the importance of a thorough anatomical understanding through precise radiological study before any sinus surgery, because of the possibility of unexpected anatomical abnormalities.

Ethical approval

Ethics clearance was not necessary since the University waives ethics approval for publication of case reports involving no patients' images, and the case report is not containing any personal information. The ethical approval is obligatory for research that involve human or animal experiments.

Funding

N/A. We received no funding in any form.

Sources of funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Guarantor

The corresponding author takes the full responsibility of the work.

Registration of research studies

This case report is not a first time of reporting, new device or surgical technique. So I would not need a Research Registry Unique identifying number (UIN).

Consent of patient

Patient's consent was taken for publishing this case and the images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Declaration of competing interest

The Authors disclose no conflicts.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2023.109089.

Appendix A. Video

The following are the supplementay data related to this article.

Data availability

All data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The case has not been presented at a conference or regional meeting.

References

- 1.Jaworek-Troć J., et al. The total number of septa and antra in the sphenoid sinuses - evaluation before the FESS. Folia Med. Cracov. 2018;58(3):67–81. doi: 10.24425/fmc.2018.125073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Unal B., et al. Risky anatomic variations of sphenoid sinus for surgery. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2006;28(2):195–201. doi: 10.1007/s00276-005-0073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teatini G., et al. Computed tomography of the ethmoid labyrinth and adjacent structures. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1987;96(3 Pt 1):239–250. doi: 10.1177/000348948709600301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ezzat S., et al. The prevalence of pituitary adenomas: a systematic review. Cancer. 2004;101(3):613–619. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agha R.A., Franchi T., Sohrab C., Mathew G., Kirwan A., Thomas A., et al. The SCARE 2020 guideline: updating consensus surgical case report (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2020;84(1):226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chougule M.S., Dixit D. A cross-sectional study of sphenoid sinus through gross and endoscopic dissection in North Karnataka, India. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2014;8(4) doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/7947.4243. p. Ac01-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Unlu A., et al. Endoscopic anatomy of sphenoid sinus for pituitary surgery. Clin. Anat. 2008;21(7):627–632. doi: 10.1002/ca.20707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamid O., et al. Anatomic variations of the sphenoid sinus and their impact on trans-sphenoid pituitary surgery. Skull Base. 2008;18(1):9–15. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-992764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fadda G.L., et al. Risky anatomical variations of sphenoid sinus and surrounding structures in endoscopic sinus surgery. Head Face Med. 2022;18(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s13005-022-00336-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orhan M., Govsa F., Saylam C. A quite rare condition: absence of sphenoidal sinuses. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2010;32(6):551–553. doi: 10.1007/s00276-010-0623-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The case has not been presented at a conference or regional meeting.