Abstract

pdxK encodes a pyridoxine (PN)/pyridoxal (PL)/pyridoxamine (PM) kinase thought to function in the salvage pathway of pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP) coenzyme biosynthesis. The observation that pdxK null mutants still contain PL kinase activity led to the hypothesis that Escherichia coli K-12 contains at least one other B6-vitamer kinase. Here we support this hypothesis by identifying the pdxY gene (formally, open reading frame f287b) at 36.92 min, which encodes a novel PL kinase. PdxY was first identified by its homology to PdxK in searches of the complete E. coli genome. Minimal clones of pdxY+ overexpressed PL kinase specific activity about 10-fold. We inserted an omega cassette into pdxY and crossed the resulting pdxY::ΩKanr mutation into the bacterial chromosome of a pdxB mutant, in which de novo PLP biosynthesis is blocked. We then determined the growth characteristics and PL and PN kinase specific activities in extracts of pdxK and pdxY single and double mutants. Significantly, the requirement of the pdxB pdxK pdxY triple mutant for PLP was not satisfied by PL and PN, and the triple mutant had negligible PL and PN kinase specific activities. Our combined results suggest that the PL kinase PdxY and the PN/PL/PM kinase PdxK are the only physiologically important B6 vitamer kinases in E. coli and that their function is confined to the PLP salvage pathway. Last, we show that pdxY is located downstream from pdxH (encoding PNP/PMP oxidase) and essential tyrS (encoding aminoacyl-tRNATyr synthetase) in a multifunctional operon. pdxY is completely cotranscribed with tyrS, but about 92% of tyrS transcripts terminate at a putative Rho-factor-dependent attenuator located in the tyrS-pdxY intercistronic region.

Pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP) is the active form of vitamin B6 and acts as an essential, ubiquitous coenzyme in many aspects of amino acid and cellular metabolism (3, 7, 10). PLP is synthesized de novo in Escherichia coli by a pathway that is thought to condense 4-phosphohydroxy-l-threonine (4PHT) and d-1-deoxyxylulose to form pyridoxine 5′-phosphate (PNP) (9, 12, 18–21, 25, 41, 45–47). PNP is then oxidized by the PdxH oxidase to form PLP, the active coenzyme (Fig. 1) (4, 24, 26, 27, 38, 48). In addition, PLP can be synthesized by a salvage pathway that utilizes pyridoxal (PL), pyridoxine (PN), and pyridoxamine (PM) taken up from the growth medium (Fig. 1) (20, 44). In the salvage pathway, PL, PN, and PM are first phosphorylated by kinases to form PLP, PNP, and pyridoxamine 5′-phosphate (PMP), respectively (Fig. 1). PNP and PMP are oxidized by the PdxH oxidase, which functions in both the salvage and de novo pathways (20, 26, 29, 48). Similar salvage pathways are present in mammalian cells, which lack a de novo PLP biosynthetic pathway (5, 6, 17). In mammalian cells, PLP homeostasis is further maintained by the offsetting activities of PL kinases and a PLP-specific phosphatase (13–15). A cytoplasmic PLP phosphatase activity has been detected in E. coli K-12, but it has not yet been determined whether this phosphatase is specific for PLP (43).

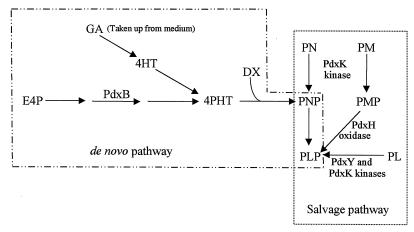

FIG. 1.

De novo and salvage pathways for PLP biosynthesis in E. coli K-12. The de novo pathway illustrates that the intermediate 4PHT is synthesized from erythrose 4-phosphate (E4P) by a series of steps, one of which is catalyzed by the PdxB dehydrogenase (9, 25, 32). 4PHT can be produced in pdxB mutants from GA or 4HT by alternative pathways that normally do not contribute to de novo PLP biosynthesis (12, 20, 46). PNP, which is the first B6 vitamer synthesized by the de novo biosynthetic pathway, is formed by the condensation of 4PHT and d-1-deoxyxylulose (DX) (18, 20, 21, 46). PNP formation from the de novo pathway does not require the activities of PL and PN kinases, which phosphorylate PL, PN, and PM taken up from the environment. The PNP/PMP oxidase PdxH functions in both the de novo and salvage pathways. As shown here, PdxY is a PL kinase in vivo, whereas PdxK is a PN kinase that can also phosphorylate PL and PM. See the text for additional details.

We recently reported the identification of the pdxK gene, which encodes a PN kinase (44). Previously, a PN kinase with additional PL and PM kinase activities was purified from E. coli, and it is likely that pdxK encodes this PN/PL/PM kinase (39). This was the first identification of a gene encoding a PN/PL/PM kinase in any organism and led to the rapid identification of a gene encoding a PL kinase in humans (17). A reverse genetics approach was used in the protozoan Trypanosoma brucei to identify a gene encoding a PL kinase, which showed significant homology to E. coli PdxK (34).

We showed previously that a pdxK null mutant lacks PN kinase activity but still contains PL kinase activity that is detectable in bacteria in which de novo PLP biosynthesis is blocked (44). This finding led to the hypothesis that E. coli K-12 contains at least one other PL kinase that converts PL to PLP. Here we confirm this hypothesis by identifying the pdxY gene, which encodes a novel PL kinase whose function is confined to the B6 vitamer salvage pathway. We show further that pdxY is located in a multifunctional operon that contains the gene for the PdxH PNP/PMP oxidase, which functions in both the de novo and salvage pathways of PLP synthesis (Fig. 1), and the essential tyrS gene, which encodes aminoacyl-tRNATyr synthetase.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Restriction endonucleases, T4 DNA polymerase, T4 DNA ligase, T7 RNA polymerase, SP6 RNA polymerase, RQ1 DNase, and Wizard Miniprep DNA Purification Systems were purchased from Promega Corp. (Madison, Wis.). Some restriction endonucleases, Vent DNA (exo+) polymerase, and 10× PCR buffer were purchased from New England Biolabs, Inc. (Beverly, Mass.). PN, PL, PM (98% pure), PLP, glycolaldehyde (GA), antibiotics, hydroxylamine, and zinc chloride were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.). RNase T2 and custom DNA oligomers were purchased from Gibco-BRL, Inc. (Gaithersburg, Md.). 4-Hydroxy-l-threonine (4HT) was a generous gift from Ian Spenser (McMaster University, Hamiton, Ontario, Canada). Bacto-Agar was obtained from Difco Laboratories (Detroit, Mich.). [3H]PN substrate was synthesized by reduction of PL with sodium [3H]borohydride as described previously (44). [α-32P]CTP (10 mCi/ml; >4,000 Ci/mmol) used to radiolabel RNA probes was purchased from Amersham Corp. (Arlington Heights, Ill.).

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and media.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Strains isogenic to NU426 were constructed by generalized transduction with P1vir bacteriophage (28, 35). Cloning and genetic manipulations were performed by standard methods (31).

TABLE 1.

E. coli K-12 strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmida | Genotype or descriptionb | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| DH5α | F− φ80dlacZΔM15 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 (rK− mK+) supE44 relA1 deoRΔ(lacZYAargF) U169 | Lab stock |

| JC7623 | recB21 recC22 sbc-15 ara arg his leu pro thr | A. J. Clark (23) |

| JM109 | endA1 recA1 gyrA96 thi hsdR17 (rK− mK+) relA1 supE44 Δ(lac-proAB) [F′ traD36 proAB lacIqZΔM15] | Promega, Inc. |

| NU426 | W3110 prototroph [W3110 sup(Am); probably W1485E] | C. Yanofsky (2) |

| NU402 | NU426 pdxB::ΩKanr | Lab stock (1) |

| NU816 | W3110 tnaA2 ΔlacU169 | C. Yanofsky (2) |

| NU1018 | NU814 pdxB::mini-Tn10Tetr | Lab stock used in cross |

| TX2768 | NU816 pdxH::ΩCmr | Lab stock (26) |

| TX3632 | NU426 pdxB::ΩKanrpdxK::mini-Tn10Cmr | Lab stock (44) |

| TX3634 | NU426 pdxB::ΩKanrpdxK::mini-Tn10Cmr | NU402 × P1vir(TX3632) |

| TX3689 | NU426 pdxK::mini-Tn10Cmr | NU426 × P1vir(TX3632) |

| TX4015 | NU426 pdxB::mini-Tn10Tetr | NU426 × P1vir(NU1018) |

| TX4016 | NU426 pdxB::mini-Tn10TetrpdxK::mini-Tn10Cmr | TX3634 × P1vir(NU1018) |

| TX4017 | JC7623 pdxY::ΩKanr | JC7623 × linear pTX623 |

| TX4021 | NU426 pdxY::ΩKanr | NU426 × P1vir(TX4017) |

| TX4022 | NU426 pdxB::mini-Tn10TetrpdxY::ΩKanr | TX4015 × P1vir(TX4017) |

| TX4023 | NU426 pdxK::mini-Tn10CmrpdxY::ΩKanr | TX3689 × P1vir(TX4017) |

| TX4024 | NU426 pdxB::mini-Tn10TetrpdxK::mini-Tn10CmrpdxY::ΩKanr | TX4016 × P1vir(TX4017) |

| Plasmids | ||

| pHP45-ΩKanr | Plasmid carrying ΩKanr cassette | P. Prentki and H. M. Krisch (30) |

| pTX303 | 0.57-kb AvaI-SacII fragment from pTX281 cloned into the BamHI site of pGEM3Z; source of RNA probes 1 and 1o | Lab stock (24) |

| pTX485 | pdxK+ clone in pGEM3Z vector; pdxK transcription direction opposite to that of lacZ | Lab stock (44) |

| pTX608 | 1.1-kb minimal pdxY+ clone in pUC19 vector; pdxY transcription in same orientation as lacZ | This work |

| pTX618 | 1.6-kb pdxY+ clone in pUC19 vector; pdxY transcription in same orientation as lacZ | This work |

| pTX623 | pTX618 pdxY::ΩKanr | This work |

| pTX628 | 1.5-kb AvaI-EcoRV fragment from pNU217 (24) cloned into AvaI and HincII sites of pGEM3Z; source of RNA probes 2 and 2o | This work |

| pTX629 | 0.60-kb EcoRI-PstI fragment from pTX630 cloned into EcoRI and PstI sites of pGEM3Z; source of RNA probes 5 and 5o | This work |

| pTX630 | 1.6-kb pdxY+ clone in pGEM3Z vector; source of RNA probes 4 and 4o | This work |

| pTX632 | Self-ligation of 2.7-kb fragment from the AvaI and BamHI double digestion of pTX628; source of RNA probes 3 and 3o | This work |

See Materials and Methods for additional details about strain and plasmid constructions.

Kanr, Tetr, and Cmr, resistance to kanamycin, tetracycline, and chloramphenicol, respectively. Besides the antibiotic resistances indicated, all plasmids also imparted resistance to ampicillin (Apr).

Vogel-Bonner minimal salts (1 × E) plus 0.4% (wt/vol) glucose medium (MMG) was supplemented with 1 μM PN, 1 μM PL, 1 μM PM, 1 mM GA, or 6 μM 4HT where indicated. Solid medium contained 1.5% (wt/vol) Bacto Agar. Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (10 g of NaCl per liter) was prepared from capsules purchased from Bio 101, Inc. (Vista, Calif.). Antibiotics were added to MMG and LB at the following concentrations where indicated: kanamycin, 12.5 and 50 μg per ml, respectively; chloramphenicol, 20 and 25 μg per ml, respectively; tetracycline, 10 μg/ml; and ampicillin, 50 to 100 μg per ml.

Cloning of pdxY.

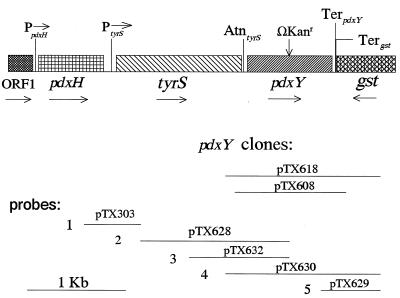

Putative genes encoding pyridoxal kinases were identified by Blast searches of the complete E. coli genome for homologs of pdxK (see Results and Discussion). A hypothetical reading frame (f287b) of 287 amino acids was found to encode PL kinase and was designated pdxY. It was amplified on 1.1- and 1.6-kb fragments from E. coli genomic DNA by using standard PCR with Vent (exo+) DNA polymerase. The primers used to amplify pdxY on the 1.1- and 1.6-kb fragments were S1 (5′-AGAAGCTTGTCTGTTTGGTCGTTTTA-3′ in tyrS)/S2 (5′-AACTGAATTCGGAAGGGTTAGAGCAC-3′ in gst) and L1 (5′-TGCAAGCTTCCCGTGGTCAGGCA-3′ in tyrS)/L2 (5′-CCTGAATTCCTGCTGGATGACGGTA-3′ in gst), respectively. The S1 and L1 or S2 and L2 primers contain HindIII or EcoRI sites, respectively. The PCR fragments were ligated into the HindIII and EcoRI sites of vector pUC19 to form plasmids pTX608 and pTX618 (Table 1; Fig. 2). The orientation of the pdxY reading frame was the same as that of the lacZα segment in the pUC19 vector, and isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) induced pdxY expression (see Results and Discussion).

FIG. 2.

Structure and transcription of the region surrounding the pdxY gene at 36.9 min in the chromosome of E. coli K-12. The figure is drawn to scale. The orientations of the reading frames of pdxH (encoding PNP/PMP oxidase), tyrS (encoding tyrosine aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase), and gst (encoding glutathione S-transferase) and the location of the pdxY::ΩKanr insertion constructed herein are indicated by arrows. Locations of the PpdxH and PtyrS promoters are from reference 24, and the Rho-factor-dependent AtntyrS attenuator and TerpdxY and Tergst terminators were localized as described in the text. Horizontal lines represent the pdxY+ inserts, generated by high-fidelity PCR, used to construct plasmids pTX618 and pTX608 (minimal pdxY+ clone) and the inserts in the indicated plasmids used to synthesize RNA probes 1 to 5 and 1o to 5o for mapping of in vivo transcripts by RNase T2 protection assays (see the text and Materials and Methods).

Culture growth, preparation of S150 crude extracts, and enzyme assays.

Five milliliters of starter cultures containing LB medium, the supplements indicated, and appropriate antibiotics were grown overnight at 37°C with vigorous shaking. One to two milliliters of the overnight cultures was inoculated into 200 ml of fresh LB containing the indicated supplements. Antibiotics were omitted from final cultures except for maintaining plasmids, in which case 50 to 100 μg of ampicillin per ml was added. The cultures were grown with shaking at 37°C to a turbidity of 70 Klett (660 nm) units (≈6.1 × 108 cells per ml) and were harvested by centrifugation at 4,420 × g for 15 min at 4°C. Cells were resuspended in 20 ml of cold 20 mM KPO4 buffer (pH 7.2) and were collected by centrifugation. Following a second round of washing, pellets were resuspended in 2 ml of cold 40 mM KPO4 buffer (pH 7.2) containing 1 mM dithiothreitol. Cells were disrupted by passage through a French pressure cell (20,000 lb/in2), and suspensions were centrifuged at 150,000 × g for 60 min. The S150 supernatants were assayed for PL and PN kinase activities.

PL kinase activity in S150 crude extracts was measured by a fluorometric assay as described in reference 36. Briefly, reaction mixtures (3 ml) contained 40 mM KPO4 (pH 7.2), 0.1 mM PL, 1 mM ATP, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 mM zinc chloride, and about 2 mg of S150 crude extract. Reactions were started by addition of the S150 crude extract, and reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 60 min. Hydroxylamine was then added to a final concentration of 1 mM, and fluorescence intensity (excitation wavelength, 380 nm; emission wavelength, 450 nm) was determined 90 s later to maximize the signal-to-background ratio of hydroxylamine adducts of PLP over PL. The combined fluorescence intensities of control reaction mixtures lacking either crude extract or PL were subtracted for each sample. Protein concentrations were determined by using a Bradford Protein Assay Kit with bovine serum albumin as the standard (Bio-Rad, Inc., Torrance, Calif.). The linearity of the PL kinase assay was confirmed for incubations of at least 60 min and for reaction mixtures containing 1 to 4.5 mg of S150 crude extract (data not shown).

PN kinase activity in S150 crude extracts was determined by conversion of [3H]PN to [3H]PNP as described before (44), except that the specific activity of the [3H]PN substrate was decreased to 3.8 mCi/mmol.

Construction of a pdxY::ΩKanr mutant.

pTX618 was digested with EcoRV, which cuts in the middle of the pdxY reading frame (Fig. 2). An ΩKanr cassette was isolated from a BamHI and ScaI digestion of plasmid pHP45ΩKanr (30), and the BamHI ends of the cassette were made blunt by filling them in with T4 DNA polymerase. A ligation mixture containing the digested pTX618 and ΩKanr cassette was used to transform strain DH5α, and transformants were selected on LB medium containing ampicillin and kanamycin. Restriction analysis of plasmid pTX623 purified from one transformant confirmed the location of the ΩKanr cassette in the middle of the pdxY gene.

The pdxY::ΩKanr insertion mutation was crossed into the bacterial chromosome by transforming strain JC7623 with pTX623 that was linearized by digestion with EcoRI (2, 40). One transformant, designated TX4017 (Table 1), that grew on LB medium containing kanamycin contained no plasmids and was sensitive to ampicillin. The location of the pdxY::ΩKanr insertion at the expected location in the chromosome (36.92 min) (Fig. 2) was confirmed by TX2768 (pdxH::ΩCmr) × P1vir(TX4017) crosses which showed that the Kanr marker was 100% linked to the Cmr marker in pdxH. The pdxY::ΩKanr cassette insertion mutation was moved from TX4017 into strains NU426, TX3689, TX4015, and TX4016 by P1vir transduction to form strains TX4021, TX4023, TX4022, and TX4024, respectively (Table 1).

RNase T2 protection assay.

Total RNA was purified from 15-ml cultures grown in LB medium at 37°C to a turbidity of 50 Klett (660 nm) units. RNase T2 protection assays were performed as described before (37). RNA probes 1 to 5 and complementary probes 1o to 5o (Fig. 2) were synthesized in vitro by using the following phage RNA polymerases (RNAP) and linearized plasmid templates: for probe 1, T7 RNAP and pTX303 cut with HindIII; for probe 1o, SP6 RNAP and pTX303 cut with EcoRI; for probe 2, SP6 RNAP and pTX628 cut with EcoRI; for probe 2o, T7 RNAP and pTX628 cut with HindIII; for probe 3, SP6 RNAP and pTX632 cut with EcoRI; for probe 3o, T7 RNAP and pTX632 cut with HindIII; for probe 4, T7 RNAP and pTX630 cut with HindIII; for probe 4o, SP6 RNAP and pTX630 cut with EcoRI; for probe 5, T7 RNAP and pTX629 cut with HindIII; and for probe 5o, SP6 RNAP and pTX629 cut with EcoRI. Protected regions of probes were analyzed by electrophoresis on gels containing 7 M urea and 6% polyacrylamide (37). No self-protection of any probes was detected for control hybridizations that contained tRNA instead of mRNA. Radioactivity in bands on dried gels was measured directly by using an Instant Imager (Packard Instrument Co., Meriden, Conn.). Sizes of protected fragments were estimated from standard curves of mobility versus size for RNA standards of known lengths, as described before (37).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Identification of pdxY encoding PL kinase.

We ran Blast searches of the recently reported E. coli genome to identify homologs of pdxK that might encode a missing PL kinase. These searches turned up three candidates: f287b (at 36.92 min; encoding a product 30% identical and 42% similar to PdxK over its whole length); yeiI (at 48.49 min; encoding a product 19% identical and 29% similar to PdxK over its whole length), and yeiC (at 48.63 min; encoding a product 20% identical and 35% similar to PdxK over its whole length). We amplified each of these reading frames by PCR under conditions that minimize errors and cloned them downstream of the Plac promoter in the high-copy-number vector pUC19. We induced expression of these reading frames by addition of IPTG to cultures of cells containing the clones, and we determined PL kinase specific activity in cell crude extracts of several different clones of each construct (Table 2) (Materials and Methods). Minimal clones, such as pTX608 (Table 1; Fig. 2), containing the f287b reading frame in a 1.1-kb fragment and clones containing f287b in a slightly larger, 1.6-kb fragment, such as pTX618 (Table 1; Fig. 2), increased PL kinase specific activity 8- to 11-fold (Table 2, JM109 strains). This result suggested that f287b encoded a PL kinase, and we renamed the reading frame pdxY. Clones containing the yeiI and yeiC reading frames did not have increased PL kinase specific activity (data not shown) and were not studied further.

TABLE 2.

PL and PN kinase specific activities in strains overexpressing the PdxY and PdxK proteins and in pdxK, pdxY, pdxY pdxK, and pdxH mutantsa

| Strain | Genotype or description | PL kinase sp act (pmol of PLP formed/min/mg of protein)b | PN kinase sp act (pmol of PNP formed/min/mg of protein)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| TX3977c | JM109(pUC19) | 45 ± 9 | ND |

| TX3981c | JM109(pTX608 pdxY+) | 371 ± 58 | ND |

| TX4002c | JM109(pTX618 pdxY+) | 488 ± 21 | ND |

| NU426d | pdxB+ pdxK+ pdxY+ parent | 72 ± 6 | 74 ± 16 |

| NU402e | pdxB pdxK+ pdxY+ | 76 ± 15 | 75 ± 16 |

| TX4015f | pdxB pdxK+ pdxY+ | 74 ± 6 | 86 ± 3 |

| TX3634e | pdxB pdxK pdxY+ | 80 ± 5 | 4 ± 1 |

| TX4022f | pdxB pdxK+ pdxY | 26 ± 4 | 82 ± 6 |

| TX4024f | pdxB pdxK pdxY | 16 ± 1 | 1.5 ± 0.2 |

| TX3636e | TX3634(pTX485 pdxK+) | 270 ± 41 | 320 ± 13 |

| TX4037c,f | TX3634(pTX608 pdxY+) | ND | 57 ± 6 |

| NU816g | pdxB+ pdxK+ pdxY+ pdxH+ parent | 63 ± 8 | ND |

| TX2768g | NU816 pdxH::ΩCmr | 47 ± 4 | ND |

See Materials and Methods for growth conditions and description of PL and PN kinase assays.

All values were determined by duplicate or triplicate assays of two or more independent cultures. Experimental errors are expressed as standard errors of the mean. ND, not determined.

IPTG was added to a final concentration of 1 mM when the final cultures reached a density of 20 Klett (660 nm) units.

GA (2 mM) or PL (2 μM) was added to overnight starter, and final cultures were assayed for both PL and PN kinase activities.

PL (2 μM) was added to overnight starter, and final cultures were assayed for both PL and PN kinase activities.

GA (2 mM) was added to overnight starter, and final cultures were assayed for both PL and PN kinase activities.

PL (100 μM) was added to overnight starter, and final cultures were assayed for PL kinase activity.

pdxY functions as a PL kinase in vivo.

We inserted an omega cassette into the pdxY reading frame and crossed the pdxY::ΩKanr insertion mutation into the E. coli K-12 chromosome (Materials and Methods). We then moved the pdxY::ΩKanr mutation into the isogenic strains listed in Tables 2 and 3. pdxY, pdxK, and pdxY pdxK mutants were not auxotrophs (TX3689, TX4021, and TX4023 [Table 3]). This result shows that the de novo pathway of PLP biosynthesis functions in the absence of the PN/PL/PM kinase PdxK and the PL kinase PdxY and is consistent with the model in which these kinases function solely in the salvage pathway (Fig. 1) (see below). In this model, the phosphate ester group of PNP, which is the first B6 vitamer synthesized de novo, is provided by the intermediate 4PHT (46).

TABLE 3.

Growth properties of pdxB, pdxK, and pdxY single, double, and triple mutants on supplemented MMGa

| Strain | Supplement added to MMG

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | PN | PL | GA | 4HT | |

| NU426 (parent) | + | + | + | + | + |

| TX3689 (pdxK) | + | + | + | + | + |

| TX4021 (pdxY) | + | + | + | + | + |

| TX4023 (pdxK pdxY) | + | + | + | + | + |

| TX4015 (pdxB) | − | + | + | + | + |

| TX4016 (pdxB pdxK) | − | − | + | + | + |

| TX4022 (pdxB pdxY) | − | + | + | + | + |

| TX4024 (pdxB pdxK pdxY) | − | − | − | + | + |

Bacteria were streaked from LB plates containing 1 mM GA and appropriate antibiotics onto freshly prepared MMG plates containing the indicated supplements. Plates were incubated at 37°C for about 40 h before growth was scored. Supplements were added at the following final concentrations: PN, 1 μM; PL, 1 μM; GA, 1 mM; 4HT, 6 μM. Commercial PM is only about 98% pure and gave the same results as PL (data not shown). +, confluent growth in heavily streaked areas and formation of single colonies; −, no single-colony formation.

We next tested the growth requirements of pdxY and pdxK mutants in strains containing a pdxB mutation, which blocks the de novo PLP biosynthetic pathway upstream of 4PHT (Fig. 1). pdxB mutants can synthesize 4PHT only when supplemented with GA or 4HT by an alternative pathway involving ThrB homoserine kinase (12, 46). The pdxB pdxK pdxY+ mutant grew when supplemented with 1 μM PL, but not when supplemented with 1 μM PN, as shown previously (TX4016 [Table 3]) (44). Given that the B6 vitamers are present in E. coli in relatively small amounts and need to be added as supplements (8, 9), this result confirms the conclusion that the PdxK gene product is the major PN kinase in E. coli K-12. Addition of 100 μM PN allowed growth of the pdxB pdxK pdxY+ mutant; however, this result cannot be interpreted, because our high-performance liquid chromatographic analyses demonstrated that commercial PN contains a contaminant that could be PL at very low levels (data not shown). Likewise, growth tests with PM were inconclusive, because commercial PM is contaminated with as much as 2% (wt/wt) PL. The pdxB pdxK+ pdxY mutant grew when supplemented with PN or PL (TX4022 [Table 3]), consistent with the previous conclusion that the purified PdxK enzyme possesses PL, as well as PN, kinase activity (39). Most significantly, the PLP requirement of the pdxB pdxK pdxY triple mutant was not satisfied by PN, PL, or PM, and the triple mutant grew only when supplemented with GA or 4HT (TX4024 [Table 3]). This result shows that PdxK and PdxY are the only physiologically significant PL, PN, and PM kinases in E. coli. Moreover, growth of the pdxB pdxK pdxY triple mutant on GA and 4HT, but not on PL, PN, or PM, strongly supports the model in which B6 vitamer kinases participate only in the salvage pathway of PLP biosynthesis (Fig. 1).

PL and PN kinase assays of crude extracts (Table 2) gave results consistent with the conclusions from the growth experiments (Table 3). The pdxB pdxK+ pdxY+ mutant had the same PL and PN kinase specific activities as the pdxB+ parent strain (NU426, NU402, and TX4015 [Table 2]). The pdxB pdxK pdxY+ double mutant lacked significant PN kinase activity but contained unchanged PL kinase specific activity (NU426 and TX3634 [Table 2]). Compared to the pdxB pdxK+ pdxY+ parent, the PL kinase specific activity was reduced about threefold in the pdxB pdxK+ pdxY double mutant, which still had full PN kinase activity (TX4015 and TX4022 [Table 2]). Finally, the pdxB pdxK pdxY triple mutant lacked PN kinase activity and contained reduced PL kinase activity compared to the pdxB pdxK+ pdxY double mutant (TX4015, TX4022, and TX4024 [Table 2]). The apparent residual PL and PN kinase activities in the pdxB pdxK pdxY triple mutant were not physiologically significant, because the triple mutant failed to grow when supplemented with PN, PL, or PM (Table 3 and data not shown). These residual activities may simply reflect background in the enzyme assays containing crude extracts. In particular, the PL kinase assay has a high background, because hydroxylamine forms fluorescent oxime adducts at a slower rate with the PL substrate than with the PLP product (36). A residual background could result if the formation of PL-oxime was slightly greater in reaction mixtures containing crude extract than in control mixtures lacking extract. Alternatively, other carbohydrate kinases, which are evolutionarily related to PdxK and PdxY (39), may use PL and PN at low levels in in vitro enzyme assays. Consistent with this notion, bacteria containing suppressors of the pdxB pdxK pdxY triple mutant readily appear on MMG plates supplemented with PN, PL, or PM at 37°C (43).

We further tested the conclusion that PdxK functions as both a PL kinase and a PN kinase by overexpressing the PdxK protein. The PN and PL kinase specific activities in crude extracts increased 80- and 3-fold, respectively, in the strain overexpressing PdxK from plasmid pTX485 compared to the pdxB pdxK pdxY+ strain lacking the plasmid (TX3634 and TX3636 [Table 2]). We also tested whether the PdxY kinase possessed a low-level PN kinase. Overexpression of PdxY did increase PN kinase about 10-fold over the background level in the pdxB pdxK pdxY+ strain (TX3634 and TX4037 [Table 2]) and allowed growth on MMG containing 2 μM PN (data not shown). However, the PdxY PN kinase activity was not physiologically significant under the growth conditions tested, because a pdxB pdxK pdxY+ mutant failed to grow when supplemented with PN (Table 3). Thus, the combined amino acid homology, growth, and enzyme assay data support the conclusions that pdxK encodes a PN kinase with moderate PL kinase activity and pdxY encodes a PL kinase with a low level of PN kinase activity that can be detected when PdxY is overexpressed.

Comparisons of PdxY and PdxK with other B6-vitamer kinases.

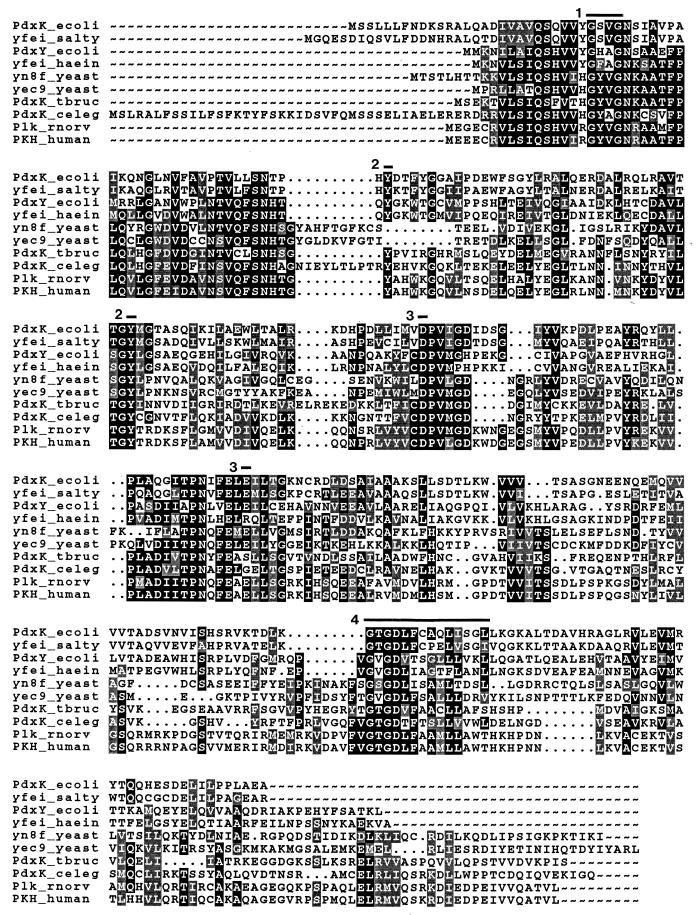

Previously, we made the observation that the PdxK kinase was a member of a superfamily of carbohydrate kinases that includes phophofructokinases and ribokinases (44). This finding was unexpected because of the different structures of the carbohydrates and the substituted pyridine ring of the B6 vitamers. Figure 3 presents an updated alignment that includes the E. coli PN/PL/PM kinase PdxK and the E. coli PL kinase PdxY, PL kinases from humans and T. brucei (17, 34), and proteins from Haemophilus influenzae, Caenorhabditis elegans, Rattus norvegicus, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and Salmonella typhimurium that likely are PL or PN kinases. This alignment indicates conserved motifs that may be involved in substrate binding or catalysis, including signature motifs found in the PfkB superfamily of carbohydrate kinases (regions 1 and 4) (42, 44); degenerate P-loop motifs (regions 1 and 4), which may be involved in ATP binding (34); candidate tyrosine residues (marked 2), one of which cannot be modified following PL binding (33); candidate aspartic and glutamic acid residues (marked 3), which may act as general bases in phosphate transfer (34); and a region (marked 4) that is affinity labeled by the bisubstrate analog adenosine tetraphosphate in the PL kinase isolated from sheep brain (11). A degenerate Walker B motif located in the T. brucei PdxK kinase (near region 3 in the third panel of the alignment) was speculated to play a role in Mg2+ binding (34) but is not well conserved in the different B6-vitamer kinases.

FIG. 3.

Amino acid alignments of the E. coli PN/PL/PM kinase PdxK and the E. coli PL kinase PdxY with homologs from other organisms. Kinase activities have been demonstrated directly only for E. coli PdxK and PdxY (see the text) (44), human PKH (human homolog of pyridoxal kinase) (17), and T. brucei PdxK (34); the other sequences are putative homologs identified by Blast searches. The sequences have the following database accession numbers: E. coli PdxK (PdxK_ecoli), GenBank U53700; S. typhimurium Yfei (yfei_salty), SW P40192; E. coli PdxY (PdxY_ecoli), DDBJ D90807 cds10; H. influenzae Yfei (yfei_haein), SW P44690; S. cerevisiae Yn8fp (yn8f_yeast), SW P53727; S. cerevisiae Yec9p (yec9_yeast), SW P39988; T. brucei PdxK (PdxK_tbruc), GenBank U96712; C. elegans PdxK (PdxK_celeg), GenBank AF003142; R. norvegicus Plk (Plk_rnorv), GenBank AF020346; and human PKH (PKH_human), U89606. Conserved motifs that may be involved in substrate binding or catalysis are overlined and discussed in the text. Solid background, identical amino acids; shaded background, similar amino acids.

Dendrogams, phylograms, and cladograms of these sequences compiled by different evolution programs in the University of Wisconsin Genetics Computer Group package all suggest that the eukaryotic and the H. influenzae proteins are more closely related to PdxY than to PdxK, whereas the S. typhimurium protein, which is encoded from an analogous region of the chromosome, is more closely related to PdxK than to PdxY. Presumably, S. typhimurium contains an unidentified homolog of PdxY. The existence of PdxK and PdxY in E. coli raises the possibility that PN- and PL-specific kinases are present in other eubacteria and in eukaryotes. This possibility has implications for current efforts to exploit B6 vitamer kinases in the uptake of selectively toxic analogs for the treatment of certain parasitic diseases (34). For example, it may be possible to exploit one of the two B6 vitamer kinases present in some organisms to enhance the selectivity of drug uptake. Finally, it was recently communicated to us that the E. coli PN/PL/PM kinase PdxK also possesses a hydroxymethylpyrimidine kinase activity and therefore may function in thiamine (vitamin B1) biosynthesis (22). It remains to be determined whether other PL and putative B6 kinases (Fig. 3) have these dual functions that possibly allow cross talk between the vitamin B6 and B1 pathways.

Structure and expression of pdxY.

pdxY is located at 36.9 min in the E. coli chromosome in the same orientation immediately downstream of pdxH (encoding PNP/PMP oxidase [Fig. 1]) and tyrS (encoding tRNATyr-aminoacyl synthetase) and in the opposite orientation to gst (encoding glutathione S-transferase) (Fig. 2). Previously, we showed that pdxH and tyrS are transcribed from separate promoters in vivo, but about 20% of tyrS transcripts are present as pdxH-tyrS cotranscripts (24). No Rho-factor-independent terminators are obvious in the sequences of the tyrS-pdxY or pdxY-gst junctions (Fig. 2), and previously we did not detect transcription termination between pdxH and tyrS (24). Therefore, we mapped the pdxY transcript by RNase T2 protection assays (see Table 1 and Fig. 2 for probes) in order to determine the transcription relationship of these genes and to learn whether pdxH and pdxY are somehow cotranscribed.

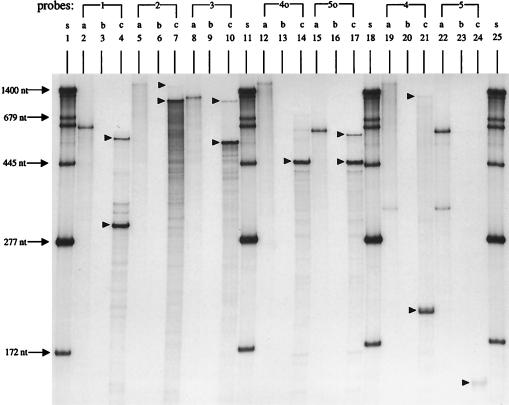

Consistent with earlier results, hybridization to probe 1, corresponding to the pdxH and tyrS noncoding strand, showed two bands of 297 and 560 nucleotides (nt) (Fig. 4, lane 4), representing transcription from the PtyrS and PpdxH promoters, respectively (Fig. 2). Hybridization to probes 2 and 3, corresponding to the tyrS and pdxY noncoding strands, each gave a large, faint, protected band and a much more intense, smaller, protected band followed by degradation products (Fig. 4, lanes 7 and 10). The large, faint, protected bands are smaller than the undigested probes, which contain linker regions (Fig. 4, lanes 5 and 8), and represent contiguous tyrS-pdxY cotranscripts. Because probes 2 and 3 end at the same place in pdxY (Fig. 2), the intense, shorter 1,050- and 530-nt bands observed with probes 2 and 3, respectively, must correspond to terminated tyrS transcripts. The sizes of the bands place the termination point in the tyrS-pdxY intercistronic region about 20 nt downstream from the translation termination codon of tyrS (Fig. 2). No bands were detected in hybridizations with probes 1o, 2o, and 3o, corresponding to the pdxH, tyrS, and pdxY coding strand, indicating that there is no antisense transcription of tyrS and pdxY in vivo and no DNA contamination in our total-RNA preparations (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

RNase T2 protection assays of transcripts from the pdxH-tyrS-pdxY-gst region of the E. coli K-12 chromosome. Total RNA was purified from strain NU426 growing exponentially in LB medium at 37°C, and RNase T2 protection assays were performed as described in Materials and Methods. The positions of RNA probes 1 to 5 used for this assay are indicated in Fig. 2. Probes 1 to 5 correspond to the pdxH, tyrS, and pdxY noncoding strands and hybridized with pdxH, tyrS, and pdxY transcripts. Probes 4o and 5o are complementary to probes 4 and 5, respectively, and hybridized to gst transcripts. See the text for additional details. a, unhybridized RNA probes; b, RNA probes hybridized with 50 μg of tRNA (self-hybridization control); c, RNA probes hybridized with 50 μg of total cellular RNA; s, RNA size standards (see Materials and Methods) (37); arrowheads, protected RNA species described in Results and Discussion.

Using probe 1, 2, or 3, we did not detect any protected band that would indicate the presence of an independent pdxY promoter. Therefore, tyrS and pdxY seemed to be cotranscribed, and the terminator between tyrS and pdxY (AtntyrS; Fig. 2) functioned as an attenuator to decrease pdxY expression relative to that of tyrS. To test further the transcription linkage between tyrS and pdxY, we tested whether a polar omega-cassette insertion mutation in pdxH decreased expression of the PdxY gene product. Previously we showed that blockage of transcription from PpdxH by a pdxH::MudI-8 insertion reduced the tyrS transcript amount by about 20% (24). We found that a pdxH::ΩCmr insertion also reduced PL kinase activity by about 25% (NU816 and TX2768 [Table 2]). This result is consistent with the interpretation that all pdxY transcription originates at the PpdxH and PtyrS promoters and that there is a low level of coupling between the transcription of pdxH and that of pdxY. Finally, quantitation of the radioactivity in gel bands indicated that about 92% of tyrS transcripts terminate at the AtntyrS terminator and only about 8% read through into pdxY. Since there is no Rho-factor-independent terminator structure in the tyrS-pdxY intercistronic region, AtntyrS is likely a Rho-factor-dependent transcription terminator.

The tyrS-pdxY cotranscript is terminated at a terminator (TerpdxY; Fig. 2) located in the pdxY-gst intercistronic region. Hybridization to probe 4, corresponding to the pdxY noncoding strand, gave 202- and 1,120-nt protected bands (Fig. 4, lane 21), which represent terminated tyrS transcripts at AtntyrS and tyrS-pdxY cotranscripts at TerpdxY, respectively. Hybridization to probe 5, corresponding to the pdxY noncoding strand, gave a faint 148-nt protected band (Fig. 4, lane 24) consistent with the location of TerpdxY, which is about 35 nt downstream from the pdxY translation stop codon (Fig. 2). Last, we located termination of the oppositely transcribed gst transcript at Tergst in the pdxY-gst intercistronic region about 4 nt downstream from the gst translation stop codon (Fig. 2). Hybridization to probes 4o and 5o, corresponding to the gst noncoding strand, gave 450-nt protected fragments representing termination at Tergst (Fig. 4, lanes 14 and 17). We also detected some (≈12%) readthrough of the Tergst terminator (Fig. 4, lane 14, series of bands above the 450-nt protected fragment, and lane 17, upper band), which would produce an antisense pdxY transcript. However, as determined by the length of the read-through transcripts, this antisense transcription did not extend past the last quarter of the pdxY reading frame. This is consistent with our observation that no antisense pdxY transcript was detected with probes 1o, 2o, and 3o (see above). Thus, it is unlikely that an antisense pdxY transcript extends to the pdxY ribosome binding site. As is the case for AtntyrS, no Rho-factor-independent structures are obvious for TerpdxY and Tergst, and these terminators may be Rho factor dependent.

Detailed molecular genetic analyses have shown that genes encoding aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases are regulated by a variety of mechanisms in E. coli, including transcription (Ala-tRNA synthetase) and translation (Thr-tRNA synthetase) autoregulation and transcription attenuation (Phe-tRNA synthetase) (reviewed in reference 16). Currently, the regulation of tyrS in E. coli is largely unknown. Precedents from genes encoding other aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases in E. coli suggest that tyrS may be regulated positively by growth rate and by tyrosine limitation (16, 24). The cotranscription of pdxY and tyrS demonstrated here may provide a point of genetic integration that coordinates incorporation of amino acids into proteins with PLP coenzyme supply. Ongoing studies are aimed at elucidating the regulation and expression of the pdxH-tyrS-pdxY multifunctional operon and the roles of the PL kinase PdxY and the PL/PM/PN kinase PdxK in maintaining PLP homeostasis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the colleagues cited in Table 1 for bacteria and bacteriophage stocks, Ian Spenser for generously providing 4HT and sharing information about PLP biosynthesis, and T. Begley, D. Cane, and D. Downs for helpful discussions about the role of kinases in PLP and thiamine biosynthesis.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant GM37561 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arps P J, Marvel C C, Rubin B C, Tolan D A, Penhoet E E, Winkler M E. Structural features of the hisT operon of Escherichia coli K-12. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:5297–5315. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.14.5297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arps P J, Winkler M E. Structural analysis of the Escherichia coli K-12 hisT operon by using a kanamycin resistance cassette. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:1061–1070. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.3.1061-1070.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bender D A. Amino acid metabolism. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi J-D, Bowers-Komro D M, Davis M D, Edmondson D E, McCormick D B. Kinetic properties of pyridoxamine (pyridoxine)-5′-phosphate oxidase from rabbit liver. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:840–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi S-Y, Churchich J E, Zaiden E, Kwok F. Brain pyridoxine-5′-phosphate oxidase: modulation of its catalytic activity by reaction with pyridoxal-5′-phosphate and analogs. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:12013–12017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Churchich J E, Kim T Y T. Pyridoxal kinase structure and function. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1990;585:357–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb28068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dakshinamurti K, editor. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 585. Vitamin B6. New York, N.Y: New York Academy of Sciences; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dempsey W B. Control of vitamin B6 biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1971;108:415–421. doi: 10.1128/jb.108.1.415-421.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dempsey W B. Synthesis of pyridoxal phosphate. In: Neidhardt F C, Ingraham J L, Low K B, Magasanik B, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: cellular and molecular biology. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1987. pp. 539–543. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dolphin D, Poulson R, Avramovic O. Vitamin B6 pyridoxal phosphate: chemical, biochemical, and medical aspects. New York, N.Y: Wiley Interscience; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dominici P, Scholz G, Kwok F, Churchich J E. Affinity labeling of pyridoxal kinase with adenosine polyphosphopyridoxal. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:14712–14716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drewke C, Notheis C, Hansen U, Leistner E, Hemscheidt T, Hill R E, Spenser I D. Growth response to 4-hydroxy-l-threonine of Escherichia coli mutants blocked in vitamin B6 biosynthesis. FEBS Lett. 1993;318:125–128. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80005-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fonda M L. Purification and characterization of vitamin B6-phosphate phosphatase from human erythrocytes. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:15978–15983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao G J, Fonda M L. Identification of an essential cysteine residue in pyridoxal phosphatase from human erythrocytes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:8234–8239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao G J, Fonda M L. Kinetic analysis and chemical modification of vitamin B6 phosphatase from human erythrocytes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:7163–7168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grunberg-Manago M. Regulation of the expression of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases and translation factors. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 887–901. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanna M C, Turner A J, Kirkness E F. Human pyridoxal kinase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:10756–10760. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.16.10756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hill R E, Himmeldirk K, Kennedy I A, Pauloski R M, Sayer B G, Wolf E, Spenser I D. The biogenetic anatomy of vitamin B6: a 13C NMR investigation of the biosynthesis of pyridoxol in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:30426–30435. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.48.30426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hill R E, Sayer B G, Spenser I D. Biosynthesis of vitamin B6: incorporation of d-1-deoxyxylulose. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:1916–1917. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hill R E, Spenser I D. Biosynthesis of vitamin B6. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 695–703. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kennedy I A, Hill R E, Pauloski B, Sayer B G, Spenser I D. Biosynthesis of vitamin B6: origin of pyridoxine by the union of two acyclic precursors, 1-deoxy-d-xylulose and 4-hydroxy-l-threonine. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:1661–1662. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kinsland, C. L., J. Reddick, and T. Begley. 1997. Personal communication.

- 23.Kushner S R, Nagaishi H, Clark A J. Indirect suppression of recB and recC mutations by exonuclease I deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1972;69:1366–1370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.6.1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lam H M, Winkler M E. Characterization of the complex pdxH-tyrS operon of Escherichia coli K-12 and pleiotropic phenotypes caused by pdxH insertion mutations. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6033–6045. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.19.6033-6045.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lam H M, Winkler M E. Metabolic relationships between pyridoxine (vitamin B6) and serine biosynthesis in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6518–6528. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6518-6528.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Man T K, Zhao G, Winkler M E. Isolation of a pdxJ point mutation that bypasses the requirement for the PdxH oxidase in pyridoxal 5′-phosphate coenzyme biosynthesis in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2445–2449. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.8.2445-2449.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCormick D B, Merrill A H. Pyridoxamine (pyridoxine) 5′-phosphate oxidase. In: Tyrfiates G P, editor. Vitamin B6: metabolism and role in growth. Westport, Conn: Food and Nutrition Press; 1980. pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller J H. A short course in bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Notheis C, Drewke C, Leistner E. Purification and characterization of the pyridoxal 5′-phosphate:oxygen oxidoreductase (deaminating) from Escherichia coli. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1247:265–271. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(94)00235-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prentki P, Krisch H M. In vitro insertional mutagenesis with a selectable DNA fragment. Gene. 1984;29:303–313. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schoenlein P V, Roa B B, Winkler M E. Divergent transcription of pdxB and homology between the pdxB and serA gene products in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:6084–6092. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.11.6084-6092.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scholz G, Kwok F. Brain pyridoxal kinase: photoaffinity labeling of the substrate-binding site. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:4318–4321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scott T C, Phillips M A. Characterization of Trypanosoma brucei pyridoxal kinase: purification, gene isolation and expression in Escherichia coli. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1997;88:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(97)00077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silhavy T J, Berman M L, Enquist L W. Experiments with gene fusions. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sussmane S, Koontz J. A fluorometric assay for pyridoxal kinase applicable to crude cell extract. Anal Biochem. 1995;225:109–112. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsui H-C, Pease A J, Koehler T, Winkler M E. Detection and quantitation of RNA transcribed from bacterial chromosomes. In: Adolph K W, editor. Methods in molecular genetics: molecular microbiology techniques, part A. Vol. 3. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1994. pp. 179–204. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wada H, Snell E E. The enzymatic oxidation of pyridoxine and pyridoxamine phosphates. J Biol Chem. 1961;236:2089–2095. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.White R S, Dempsey W B. Purification and properties of vitamin B6 kinase from Escherichia coli B. Biochemistry. 1970;9:4057–4064. doi: 10.1021/bi00823a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Winans S, Elledge S J, Krueger J H, Walker G C. Site-directed insertion and deletion mutagenesis with cloned fragments in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1985;161:1219–1221. doi: 10.1128/jb.161.3.1219-1221.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wolf E, Hill R E, Sayer B G, Spenser I D. 4-Hydroxy-l-threonine, a committed precursor of pyridoxol (vitamin B6) J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1995;1995:1339–1400. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu L F, Reizer A, Reizer J, Cai B, Tomich J M, Saier M H. Nucleotide sequence of the Rhodobacter capsulatus fruK gene, which encodes fructose-1-phosphate kinase: evidence for a kinase superfamily including both phosphofructokinases of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:3117–3127. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.10.3117-3127.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang, Y., and M. E. Winkler. 1997. Unpublished results.

- 44.Yang Y, Zhao G, Winkler M E. Identification of the pdxK gene that encodes pyridoxine (vitamin B6) kinase in Escherichia coli K-12. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;141:89–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao G, Pease A J, Bharani N, Winkler M E. Biochemical characterization of gapB-encoded erythrose 4-phosphate dehydrogenase of Escherichia coli K-12 and its possible role in pyridoxal 5′-phosphate biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2804–2812. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.10.2804-2812.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao G, Winkler M E. 4-Phospho-hydroxy-l-threonine is an obligatory intermediate in pyridoxal 5′-phosphate coenzyme biosynthesis in Escherichia coli K-12. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;135:275–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao G, Winkler M E. An Escherichia coli K-12 tktA tktB mutant deficient in transketolase activity requires pyridoxine (vitamin B6) as well as the aromatic amino acids and vitamins for growth. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6134–6138. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.19.6134-6138.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhao G, Winkler M E. Kinetic limitation and cellular amount of pyridoxine (pyridoxamine) 5′-phosphate oxidase of Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:883–891. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.4.883-891.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]