Abstract

Background

Children with decompensated cirrhosis (DC) awaiting LT suffer from infection linked to high pediatric end-stage liver disease (PELD) scores and mortality. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) therapy has shown promising results in adult DC. Our study investigated G-CSF as an optimizing treatment for pre-transplant DC, exploring its effect on cytokine activity.

Methods

An open-label, randomized controlled trial included DC patients aged 3 months-12 years. The intervention group (n=26) received 12 G-CSF courses injected subcutaneously (5 μg/kg/day) plus DC standard medical treatment (SMT). The control group (n = 24) received SMT. We obtained PELD scores, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-10, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), CD34+ mobilization, liver function, leukocyte and neutrophil counts. Infection and side effects were documented.

Results

There was no significant difference in PELD scores between the groups after 3 months G-CSF treatment. Decreased TNF-α (p < 0.001) and increased IL-10 and HGF (p = 0.003 for both markers) were shown 1 month following G-CSF treatment. Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels improved significantly (p = 0.038). Significant increase in leucocyte and neutrophil counts (p < 0.001) and a lower incidence of sepsis (p = 0.04) were shown after intervention. There was no significant difference in survival (p = 0.372).

Conclusion

Following 3 months of G-CSF treatment, PELD scores did not show significant improvement. G-CSF reversed the cytokine profiles in DC, resulting in reduced TNF-α and increased IL-10. HGF significantly improved, indicating hepatic regeneration. Significantly decreased occurrence of sepsis following G-CSF treatment indicated improved clinical outcome.

Keywords: G-CSF, cytokine, pediatric cirrhosis

Globally, the mortality rate of cirrhosis in adults is 2.1%. The data in children remain unknown. Liver transplantation (LT) remains as the only definitive therapy in adult and children with cirrhosis.

Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) stimulates bone marrow to produce hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and proliferation and differentiation of neutrophils released into the systemic circulation.1,2 G-CSF treatment for liver cirrhosis has been studied broadly, mainly in severe alcoholic hepatitis and in acute or chronic liver failure, in the adult population.3 These studies showed varying results, from promising potentials to negative outcomes.4, 5, 6, 7

Cirrhosis-associated immune dysfunction (CAID) associated with immunological derangement in liver cirrhosis patients is one of the leading causes of infection, sepsis, multiorgan failure, and death.5,8 Bacterial translocation in cirrhosis increases systemic circulating of inflammatory mediators that further causes tissue damage. This results in impairment of neutrophil function, which is one of the factors in innate immunity.

Multiple studies regarding G-CSF use have been conducted previously; however, studies of G-CSF within the pediatric population remain limited. This study remains as one of the few that focuses on the effects of G-CSF on cytokine changes and aims to evaluate the clinical outcomes of G-CSF administration in pediatric decompensated cirrhosis (DC), along with cytokine activity alterations of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-ɑ, interleukin (IL)-10, and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF). This study is part of a previous clinical trial conducted, which was a preliminary study that highlighted the effects of G-CSF therapy in pretransplant DC pediatric patients with a smaller sample size, and here we present data that have not yet been published, specifically regarding cytokine activity and innate immunity.9

Methods

Study Design

Our study was a prospective, open-labeled, randomized trial. Subjects registered between 2019 and December 2021 in the national referral hospital were recruited based on history-taking with parents or guardians, physical examinations, and laboratory and radiological findings.

Sample Size

The sample size calculation was based on standard equation for the comparison of two means as follows: , (Zɑ: is the value of normal distribution assuming a confidence interval (CI) of 95%, ɑ: 0,05 and a critical value of 1.96, and Zβ: assumes a power of 80%, β: 0,2 and a critical value of 0,84). The standard deviations (SDs) of both groups were based on the pediatric end-stage liver disease (PELD) score changes of from the liver transplant list enrolled between January 2017 and December 2018 who have previously been given a standard treatment. For the purpose of calculating sample size, it was assumed that the SD of both groups was equal (SD = 6.17). The sample size was calculated based on a PELD score difference (, based on authors clinical experience and judgment reflecting a marked improvement in the patient's overall clinical condition. The sample size target was a minimum of 24 subjects per group.

Patients

We enrolled 50 patients awaiting LT, randomized into 26 participats in the intervention group and 24 in the control group.

Inclusion criteria were clinically decompensated liver cirrhosis, confirmed with biopsy and/or imaging regardless of the etiology, age between 3 months and 12 years, PELD scores between 10 and 25, conscious, and a compromised nutritional status. Nutritional status was categorized based on the World Health Organization for children younger than 5 years Arm-Circumference-for-Age Chart and the Centers for Disease Control growth curve for patients older than 5 years. The exclusion criteria were malignancy, history of any transplantation procedure, acute liver failure, organ failure other than liver, encephalopathy, severe infection, and refusal to participate in the study. Parents/guardians of patients were informed of the overall protocol and standard treatment for intervention and control group prior to randomization and provided written informed consent.

Randomization

Randomization was achieved by computer-based block randomization to categorize subjects into one of the two groups. Subjects were informed at the beginning of the study that they may be allocated to either group.

Treatment

G-CSF was administered in the intervention group (Leucogen®, Kalbemed Pharmaceutical, Indonesia), given at 5 μg/kg body weight for five consecutive days, continued by an intermittent administration of the same dose every 3 days up to a total of 12 doses. Both groups received standard treatment of ursodeoxycholic acid (30–50 mg/kg/day) for 3 days, vitamin E (1 × 50 mg), vitamin A (1 × 5000–25,000 International Units [IU]), vitamin C (1 × 800–5000 IU), vitamin K injection (0.2 mg/kg/month), and enteral nutrition catered to the patient's nutritional evaluation. The nutritional treatment was closely followed-up with monthly evaluations and supplementation of medium-chain triglyceride milk formula orally.

CD34 Examination

CD34+ mobilization was calculated, based on flow cytometry stained with CD34+ antibody. Samples obtained from peripheral venous blood samples were stored in 3-mL ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid anticoagulated (EDTA) tubes. Following the International Society of Hematotherapy and Graft Engineering protocol, the enumeration was obtained using the following formula:

Interleukin-10, TNF-ɑ, and HGF Evaluation

The cytokines measured were IL-10, TNF-ɑ, and HGF. The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits used (R&D Systems, Inc., USA) quantified the level of each respective cytokine by the sandwich enzyme immunoassay technique. Plasma samples obtained through peripheral venous blood samples, stored in EDTA tubes, were centrifuged and prepared prior to immunoassay. The samples were pipetted into wells onto microplates specific for IL-10, TNF-ɑ, and HGF. After washing, an enzyme-linked monoclonal antibody specific to IL-10, TNF-ɑ, and HGF, respectively, was added to each microplate. After washing was complete, a substrate solution was added to the wells, and color change was measured at 450 nm. Each sample and cytokine immunoassay was duplicated and tested twice. The concentrations of IL-10, TNF-ɑ, and HGF were determined based on the average duplicate readings compared to the standard optical density curve.

Data Collection and Follow-up

Patients were observed for 3 months, with periodic subjective assessments, physical examinations, laboratory examinations and nutritional evaluations. Physical examination, anthropometric data (weight, height, mid-upper arm circumference), triceps skinfold thickness, peripheral blood count, neutrophil count, liver function test, procalcitonin level, and PELD score was calculated using an online calculator developed by the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network at the beginning of the study. An anthropometric evaluation was performed monthly on days 0, 30, 60, and 90 to assess the patients’ recommended daily allowance (RDA) and prior monthly intake. Laboratory examinations were performed prior to the study and followed up on days 0, 6, 18, 30, 60, and 90. HGF, IL-10, and TNF-ɑ levels were assessed based on peripheral blood collected on days 0 and 30, whereas CD34+ mobilization was measured on days 0, 6, and 30 by flowcytometry.

Outcome

The primary outcome was the PELD score. Secondary outcomes were HGF, IL-10, and TNF-α levels. Additionally, we assessed liver function tests, CD34+ cell mobilization, nutritional status, and leukocyte and neutrophil changes. Adverse effects of G-CSF treatment intervention were systematically reported, alongside survival and sepsis occurrence within 3 months.

Ethical Approval

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of our institution (reference 19-07-0943), and all procedures adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1977. The study has been registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (number NCT04113317). The sponsor of the trial (NKB-180/UN2.RST/HKP.05.00/2020) was the Indonesian Ministry of Research and Technology.

Statistical Analysis

Data were presented as means ± SD for normally distributed data and as medians and ranges for skewed data. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to determine normality distribution. Mann–Whitney or independent t-test was conducted to compare between two groups. Repeated measures were analyzed using the analysis of variance test to compare trends between the intervention and control groups. Two-tailed statistical analyses were conducted, with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS software version 25. All results shown were calculated based on an intention-to-treat.

Results

We screened 102 patients with DC for the study between September 2019 and December 2021, of whom, 52 were enrolled based on the inclusion criteria. Two paticiapants dropped out due to inability to continue (Figure 1). Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of both groups, which showed no significant difference. Randomization divided participants into 26 patients in the intervention group and 24 participants in the control group. Within the intervention group, 5 participants were unable to complete the G-CSF administration protocol. Four patients missed the scheduled regimen due to episodes of acute infection, and one was unable to attend at the time of the scheduled treatment.

Figure 1.

Study flow.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics.

| Intervention Group (n = 26) | Control Group (n = 24) | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male:female)b | 11:15 | 13:11 | 0.402 |

| Diagnosis | 0.423 | ||

| Biliary atresia | 18 | 14 | |

| Alagille's syndromea | 4 | 6 | |

| PFIC type IIIa | 3 | 0 | |

| Caroli's diseasea | 0 | 1 | |

| Choledocal cysta | 1 | 3 | |

| Age (month) | 23 ± 31 | 17 ± 14 | 0.992 |

| Body weight (kg)d | 8.2 ± 4.3 | 7.3 ± 1.7 | 0.954 |

| Height (cm)d | 73 ± 16 | 70 ± 7.5 | 0.838 |

| MAC (cm)d | 11.44 ± 1.42 | 10.67 ± 1.33 | 0.137 |

| Nutritional status | 0.874 | ||

| Severely malnourish | 20 | 18 | |

| Undernourished | 6 | 6 | |

| RDA (%) | 104 ± 31 | 92 ± 24 | 0.147 |

| PELD scorec | 18 ± 4 | 17 ± 4 | 0.456 |

| Hb (g/dL)c | 9.3 ± 1.2 | 8.9 ± 1.5 | 0.260 |

| Platelet ( × 103/μL)c | 188,231 ± 79,257 | 236,708 ± 107,036 | 0.074 |

| Leukocyte ( × 103/μL)d | 10880 ± 5279 | 11627 ± 5838 | 0.281 |

| Basophil (%)d | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 0.449 |

| Eosinophild | 2.5 ± 2.1 | 1.6 ± 0.9 | 0.109 |

| Neutrophil (%)c | 47.5 ± 14.5 | 51.6 ± 11.9 | 0.290 |

| Lymphocyte (%)c | 41.6 ± 15.2 | 38.8 ± 12.1 | 0.474 |

| Monocytec | 7.75 ± 2.17 | 7.51 ± 2.28 | 0.708 |

| ANCd | 5151.05 ± 3161.80 | 6471.26 ± 3547.57 | 0.140 |

| Prothrombin time (second)c | 12.8 ± 1.5 | 13.0 ± 1.7 | 0.655 |

| INRd | 1.23 ± 0.17 | 1.25 ± 0.17 | 0.409 |

| AST (U/L)d | 249 ± 143 | 206 ± 180 | 0.057 |

| ALT (U/L)d | 139 ± 92 | 120 ± 126 | 0.087 |

| Albumin (g/dL)c | 2.93 ± 0.46 | 3.00 ± 0.37 | 0.545 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL)d | 19.73 ± 7.00 | 20.64 ± 8.20 | 0.641 |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dL)d | 15.32 ± 5.79 | 15.86 ± 6.48 | 0.698 |

| Indirect bilirubin (mg/dL)c | 4.71 ± 1.99 | 4.78 ± 2.01 | 0.901 |

| GGT (U/L)d | 317.92 ± 309.42 | 336.63 ± 399.78 | 0.977 |

| TNF-αd | 1.47 ± 0.20 | 1.47 ± 0.19 | 0.938 |

| IL-10d | 0.49 ± 0.13 | 0.48 ± 0.11 | 0.801 |

| HGFd | 0.41 ± 0.08 | 0.41 ± 0.10 | 0.627 |

PFIC = progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis; MAC = mid-arm circumference; RDA = recommended dietary allowance; PELD = pediatric end-stage liver disease; Hb = hemoglobin; ANC = absolute neutrophil count; INR = international normalized ratio; AST = aspartate aminotransferase; ALT = alanine aminotransferase; GGT = Gamma-glutamyl transferase, TNF-α = tumor necrosis factor-α, ΙL-10 = interleukin-10, HGF = hepatocyte growth factor.

categorical data calculated as oen group.

n.

normally distributed data.

Skewed data

Primary Outcomes

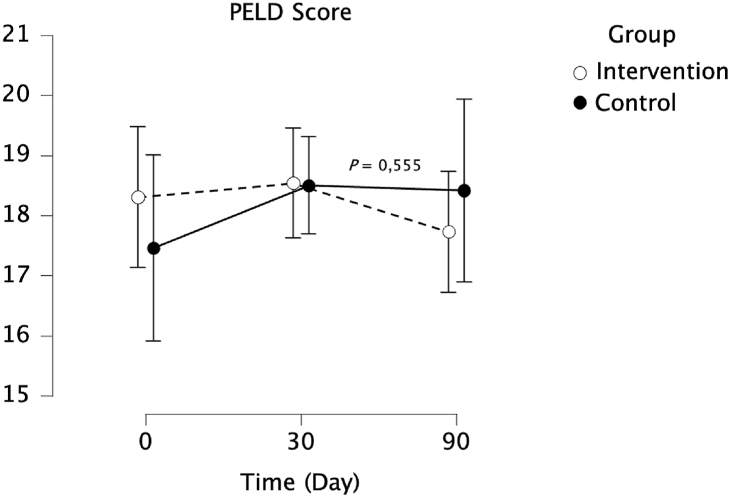

Effect of G-CSF Administration on PELD Score

The study showed there was no significant difference in PELD score between the intervention and control groups (P = 0.555). However, there was a greater decrease in PELD score from day 30 to day90 in the intervention group compared to the control group (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

PELD score changes in intervention and control groups.

Secondary Outcomes

Effect of G-CSF Administration on TNF-α, IL-10, and HGF

One of the secondary outcomes assessed in this study was cytokine changes, marked by TNF-α, IL-10, and HGF levels, as a result of G-CSF administration. TNF-α showed a decreasing trend from day 0 to day 30 in both groups (Figure 3). There was a statistically significant difference (P < 0.001) between the groups. IL-10 and HGF increased from day 0 to day 30 that was statistically significant in the intervention group (P value for each = 0.003) (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Effects of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor administration on cytokine changes.

Table 2.

Effect of Granulocyte Colony-stimulating Factor Administration to Tumor Necrosis Factor-α, Interleukin-10, and Hepatocyte Growth Factor.

| Intervention group (n = 26) | Control group (n = 24) | P-value∗ | P-value∗∗ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α | ||||

| Day 0a | 1.47 ± 0.20 | 1.47 ± 0.19 | 0.938 | |

| Day 30 | 1.10 ± 0.40 | 1.37 ± 0.26 | 0.006 | 0.001 |

| IL-10 | ||||

| Day 0a | 0.49 ± 0.13 | 0.48 ± 0.11 | 0.801 | |

| Day 30 | 0.84 ± 0.28 | 0.63 ± 0.21 | 0.004 | 0.003 |

| HGFa | ||||

| Day 0 | 0.41 ± 0.08 | 0.41 ± 0.10 | 0.627 | |

| Day 30 | 0.90 ± 0.38 | 0.63 ± 0.29 | 0.007 | 0.003 |

∗P-value for independent t-test (normally distributed data)/Mann–Whitney test (skewed data) showed the comparison between intervention and control group.

∗∗P-value for analysis of variance test showed the comparison between repeated measures.

TNF-α = tumor necrosis factor-α, ΙL-10 = interleukin-10, HGF = hepatocyte growth factor.

Skewed data.

Effect of G-CSF Administration on the Mobilization of CD34+

CD34+ represents hematopoietic stem cell mobilization within peripheral blood circulation. The mobilization of CD34+ was calculated based on the difference between CD34+ from day 0 until day 6 and from day 6 until day 30. From day 0 until day 6, there was a higher change in the intervention group than in the control group (P = 0.296). From day 6 to day 30, there was also a higher change in CD34+ in the intervention group than in the control group (P = 0.576). Evidence of increased mobilization of CD34+ was noted by the higher difference in CD34+ amount on day 30 than on day 0, with the intervention group changing by 12.05 and the control group changing by 8.11. Despite these changes, there was no significant difference in the mobilization of CD34+ between both groups.

Effect of G-CSF Administration on Liver Function Test

G-CSF administration resulted in lower alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level by significantly lowering the ALT value in the intervention group compared to the control group (P = 0.038) (Figure 3). On the contrary, G-CSF did not improve aspartate aminotransferase (P = 0.102), total bilirubin (P = 0.396), and albumin levels (P = 0.757) in the intervention group (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of Granulocyte Colony-stimulating Factor Administration to Liver Function Tests.

| Intervention group (n = 26) | Control group (n = 24) | P-value∗ | P-value∗∗ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AST | ||||

| Day 0a | 249 ± 143 | 206 ± 180 | 0.057 | |

| Day 6a | 211 ± 100 | 204 ± 181 | 0.153 | |

| Day 18a | 257 ± 202 | 213 ± 166 | 0.264 | |

| Day 30 | 257 ± 145 | 172 ± 93 | 0.018 | |

| Day 60 | 212 ± 101 | 193 ± 110 | 0.525 | |

| Day 90 | 198 ± 101 | 187 ± 108 | 0.720 | 0.102 |

| ALT | ||||

| Day 0a | 139 ± 92 | 120 ± 126 | 0.087 | |

| Day 6a | 118 ± 64 | 120 ± 128 | 0.180 | |

| Day 18a | 141 ± 114 | 125 ± 118 | 0.277 | |

| Day 30a | 131 ± 72 | 106 ± 96 | 0.109 | |

| Day 60a | 113 ± 53 | 119 ± 99 | 0.541 | |

| Day 90a | 111 ± 56 | 115 ± 94 | 0.683 | 0.038 |

| Albumin | ||||

| Day 0 | 2.93 ± 0.46 | 3.00 ± 0.37 | 0.545 | |

| Day 6 | 3.06 ± 0.41 | 3.19 ± 0.38 | 0.271 | |

| Day 18 | 2.96 ± 0.40 | 3.03 ± 0.39 | 0.538 | |

| Day 30 | 3.00 ± 0.41 | 2.98 ± 0.44 | 0.903 | |

| Day 60 | 2.90 ± 0.36 | 2.94 ± 0.43 | 0.732 | |

| Day 90 | 2.98 ± 0.39 | 2.90 ± 0.51 | 0.9524 | 0.757 |

| Bilirubin Total | ||||

| Day 0a | 19.73 ± 7.00 | 20.64 ± 8.20 | 0.641 | |

| Day 6a | 19.64 ± 7.67 | 21.03 ± 8.48 | 0.351 | |

| Day 18a | 19.70 ± 7.41 | 19.99 ± 7.82 | 0.816 | |

| Day 30a | 20.95 ± 7.85 | 20.61 ± 8.28 | 0.961 | |

| Day 60 | 21.93 ± 8.77 | 20.22 ± 8.53 | 0.488 | |

| Day 90 | 21.66 ± 8.89 | 2183 ± 9.30 | 0.948 | 0.396 |

∗P-value for independent t-test (normally distributed data)/Mann–Whitney test (skewed data) showed the comparison between intervention and control group.

∗∗P-value for analysis of variance test showed the comparison between repeated measures.

ALT = alanine aminotransferase; AST = aspartate aminotransferase.

Skewed data.

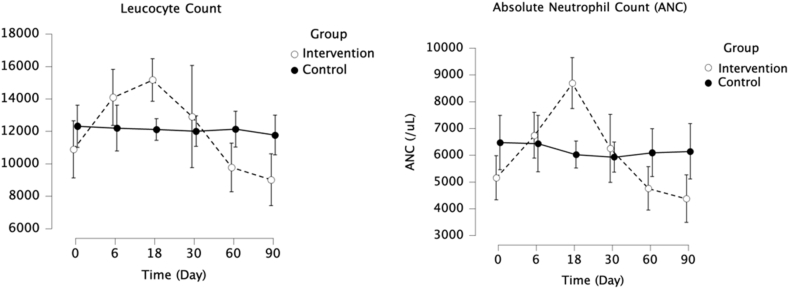

Effect of G-CSF Administration on Leukocyte and Neutrophils

G-CSF significantly increased leukocyte and neutrophil counts in the intervention group compared to the control group (P < 0.001 for both). Within the intervention group, both leukocyte and neutrophil counts peaked on day 18 and gradually reduced until the completion of the study (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Effect of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor administration on leukocyte and neutrophil counts.

Effect of G-CSF Administration on Nutritional Status

At the baseline, both groups presented with most patients with 73% and 75% in the intervention and control groups, respectively, classified as severely malnourished with a MUAC per age z-score less than −3. Within three months, there was a slight improvement in the nutritional status of the intervention group compared to the control group. On days 30 and 60, less individuals in the intervention group had a z-score <−3 than on day 0. Meanwhile, the control group showed an increase in the number of patients with a z-score <−3 from day 0 to day 30 and 60 (Table 4). However, there was no statistical difference in nutritional status between the intervention and control groups.

Table 4.

Effect of Granulocyte Colony-stimulating Factor Administration on Nutritional Status.

| Nutritional Status | Day 0 |

Day 30 |

Day 60 |

Day 90 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention (n) | Control (n) | P value | Intervention (n) | Control (n) | P value | Intervention (n) | Control (n) | P value | Intervention (n) | Control (n) | P value | |

| MUAC z-score | ||||||||||||

| Z < −3 | 19 | 18 | 0.877 | 18 | 19 | 0.424 | 18 | 19 | 0.424 | 17 | 17 | 0.488 |

| −3 < Z ≤ -2a | 6 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 5 | ||||

| −2 < Z ≤ -1a | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| −1 < Z ≤ 1a | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| TST z-score | ||||||||||||

| Z < −3 | 13 | 10 | 0.555 | 13 | 11 | 0.768 | 12 | 11 | 0.982 | 12 | 10 | 0.749 |

| −3 < Z ≤ -2a | 4 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 4 | ||||

| −2 < Z ≤ -1a | 5 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | ||||

| −1 < Z ≤ 1a | 4 | 6 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 6 | ||||

| 1 < Z ≤ 2a | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

P-value for Pearson Chi-Square analysis.

TST = triceps skinfold thickness; MUAC = mid-upper arm circumference.

Calculated as one group.

Infection and Adverse Events

A total of 14 patients had incidents of infection that required hospitalization. The intervention group recorded five infection events within the first month due to fever, pneumonia, upper respiratory tract infections, urinary tract infections, measles, and acute gastroenteritis. There were 9 infection events recorded within the control group due to cytomegalovirus, fever, pneumonia, coronavirus disease-19, tuberculosis, and acute gastroenteritis. Five patients from the control group developed sepsis, but none was reported from the intervention group. The difference in sepsis occurrence between the groups was statistically significant, as analyzed with Fisher exact's test (P = 0.04).

The adverse effects recorded in the intervention group included fever, epistaxis, cough, and leukocytosis. The most common adverse effect reported by 42% of the subjects was low-grade fever (37.5–38.5 °C).

Survival

A total of 8 patients died, three from the interventional group and five from the control. Patients within the intervention group who died had already completed their injection protocol. Causes of death were hepatic encephalopathy and rupture of esophageal varices. Within the control group, causes of death were refractory hypovolemic shock, sepsis, and respiratory failure. Based on the Kaplan–Meier method, there was statistically no significant difference in survival between the intervention and control groups (P = 0.372).

Discussion

LT has been the only well-established cure for DC in children, with biliary atresia as the most common cause at our center.5,8 Liver-donor allocation is determined by the PELD score, whereby higher scores warrant a higher priority in receiving the organ, based on the mortality risk. In developing countries, liver cirrhosis in children is commonly underdiagnosed in early stages. Upon arrival at our referral center, 78% of them are at an age lower than 2 years, with a myriad of complications that make them ineligible for the definitive procedure,10 necessitating alternative therapies to optimize their condition and decelerate liver injury.

Our study explored the effects of G-CSF on PELD score and cytokine levels (TNF-α, IL-10, and HGF) in children with DC awaiting LT. G-CSF did not significantly improve the PELD score and showed high levels of proinflammatory and low anti-inflammatory cytokines prior to the intervention. G-CSF stimulated reversal of these cytokine profiles and the induction of HGF as a marker of hepatic tissue regeneration. High CD34+ in the intervention group indicated mobilization.

Cirrhosis is a chronic condition that results from a reactive orchestra of the immune components of the liver. Regardless of the etiology, the pathophysiology begins with inflammation of the hepatocytes.5,8 Progressive tissue necrosis, proinflammatory cytokines activation, and reactive oxidation species through hepatic stellate cells disrupt the local immune surveillance function and systemic immune response prevails.8,11 The resulting complication, described as CAID by Albillos et al.,8 stimulates a chaotic immune reaction, episodically and excessively activating proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IL-2, 4, 6, and 8), known as the cytokine storm, released by necrotic liver cells and leaky gut. The turning point is a systemic inflammation followed by immunodeficiency, clinically manifested in stable cirrhosis patients and decompensated or acute on chronic liver failure, respectively.8,11 There is a 30–60% occurrence of sepsis in cirrhosis patients, with a 3- to 5-times increase in the risk of infection compared to the general population.12 Restoration of the proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory balance has been postulated as a potential pathway to reverse the liver injury.13, 14, 15 We detected high baseline levels of TNF-α in control and treatment groups, verifying that circulating of cytokines in cirrhosis of congenital origin is equally evident, confirming findings of other studies in DC and acute on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) in adults.16,17

Recent data have shown that G-CSF can repair damaged cells and tissues, demonstrated in animal and human studies, through HSCs mobilization marked by CD34+ cells, indicating a promising therapy in regenerative medicine.18,19 G-CSF use in adults with ACLF and DC had prolonged survival, nutrition, and reducing infection rates.4, 5, 6, 7 At the commencement of this trial, no studies of G-CSF for chronic liver conditions in children have been reported. To the author's knowledge, there has not been any study that explored the level of cytokine changes after G-CSF therapy in children with chronic liver disease.

To explore G-CSF as a potential bridging therapy prior to LT, we observed the effect on PELD score. Our result is similar to that of Sharma et al.20 which demonstrated insignificant improvement in PELD score after a year following G-CSF treatment in children with ACLF. No other study to date reported the effect of G-CSF on PELD score. In adults, G-CSF has been reported to improve MELD and CTP scores.4,21

A month following G-CSF therapy, TNF-α as a pro-inflammatory cytokine reduced and a rise of HGF and IL-10 as anti-inflammatory cytokines in the intervention group. TNF-α is a pivotal pro-inflammatory cytokine produced by Kupffer cells that stimulate hepatic stellate cells, contributing to fibrosis and matrix remodeling.13,22 HGF increase through CD34+ mobilization and HPC proliferation stimulated by G-CSF administration was reported by Spahr et al.23 in patients with alcoholic steatohepatitis.23 Although HGF induction was successful in our study, little is established about its regenerative capacity on decompensated liver cirrhosis and the relatively unchanged clinical liver parameters observed.

The exact mechanism of improvement of innate immunity remains unexplored. Administration of G-CSF activates proliferation, differentiation, and mobilization of neutrophils in the peripheral blood and HSCs from the bone marrow to the hepatic tissue, marked by elevated CD34+ in the peripheral blood, though statistically insignificant (Figure 5.). HSCs may enter the hepatic tissue, stimulating cytokine changes through a paracrine mechanism, Kupffer cells, and other immune cells to reduce TNF-α and release IL-10, subsequently activating liver sinusoidal endothelial cells to secrete HGF that induces hepatocyte regeneration and produces functional hepatocytes, reflected by reduced ALT level.

Figure 5.

Proposed mechanism of hematopoietic stem cell mobilization by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor treatment in improving innate immunity.

The dose of G-CSF given at 5 mcg/kg/day given for five days consecutively and a single dose every three days for 12 doses was clinically safe and tolerable. Leukocytosis with neutrophilia was observed postinjection in the intervention group. The most common adverse event reported in this study was low-grade fever. Adverse events reported were mild and manageable with conservative treatment. Other adverse events that were expected as a result of G-CSF treatment included malaise and bone pain; however, the patients were unable to be evaluated for those symptoms as the pediatric patients were unable to communicate those symptoms.24 In older patients, who could be asked about those symptoms, no incidence of malaise or bone pain was reported. Hypersplenism was also a concern after G-CSF therapy; however, no patients presented with an enlarged abdomen after the intervention. Within this study, there were no major adverse events reported that resulted in the cessation of intervention protocol.

In this study, the number of patients who experienced infections from both the intervention group and the control group was not significantly different; however, when viewed based on the degree of infection severity, no sepsis events were evident in the intervention group. Meanwhile, in the control group, 5 patients experienced sepsis. The mortality rate in the control group was higher than in the intervention group, with the most common cause of death in the control group being sepsis. There was evidence of improved innate immunity characterized by a decrease in the proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α and an increase in the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10, neutrophils, and leukocytes. Together with innate immunity, they explain the results that fewer patients developed sepsis in the intervention group than in the control group. The causes of death of two patients in the intervention group were esophageal variceal hemorrhage and hepatic encephalopathy. The aetiologies related to the intervention group's deaths are unlikely due to G-CSF treatment as it occurred more than a month after the patient’s last G-CSF treatment. The peak concentration of G-CSF is at 4 h after administration, a half-life of approximately 8 h, and a clearance rate of 0.6 mL/min/kgBW.25,26

Following three months of G-CSF therapy, ALT decreased, whereas other liver function tests showed insignificant changes. This may indicate a probable transient optimization of patients awaiting LT, though not clinically apparent. Verma et al.4 showed an improved albumin level in ACLF/DC liver disease in adults receiving G-CSF after 6 and 12 months of follow-up.4 A longer follow-up on these liver parameters with varying doses of G-CSF may need to be observed.

No changes in nutritional parameters following treatment with G-CSF was observed. This finding contrasts with the data that revealed a substantial improvement in MUAC.4 In children with DC, factors other than the state of hypermetabolism, such as higher demand of required daily intake (up to 130–150%), malabsorption, disorderly utilization of absorbed nutrients, and compromised appetite are challenging to counteract. Parents face the economic burden of purchasing nutritious milk and the challenging dietary care that requires discipline and perseverance.

Cirrhosis is a disease that is orchestrated by a dysfunctional immunity, especially the innate system. The rate of infection and absence of sepsis in our intervention group may indicate a potential effect on managing infection and preventing sepsis prior to performing LT and deserves further exploration. Although G-CSF did not improve the PELD score, our findings suggest an improvement in the immunity. The effort in restoring a balance between proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines may be a potential key strategy in understanding and achieving liver injury reversal. Our study clinically emphasized the immune biomarker profile in the occurrence of CAID and that G-CSF therapy achieved reversal of these cytokine levels. This study is the first to observe these changes in children with decompensated liver disease. Further trials are warranted to discover how these findings translate to the bedside aspect to discover the potential novel treatment for chronic liver diseases.

Credit authorship contribution statement

Conceptualization: Tri Hening Rahayatri, Aria Kekalih, Alida Harahap, Aryono Hendarto, Hanifah Oswari, Zakiudin Munasir, Rianto Setiabudy, Akmal Taher; Methodology: Tri Hening Rahayatri, Aria Kekalih, Alida Harahap, Hanifah Oswari, Rianto Setiabudy, Akmal Taher; Formal analysis and investigation: Tri Hening Rahayatri, Aria Kekalih; Writing - original draft preparation: Tri Hening Rahayatri; Writing - review and editing: Tri Hening Rahayatri, Aria Kekalih, Alida Harahap, Aryono Hendarto, Hanifah Oswari, Zakiudin Munasir, Rianto Setiabudy, Akmal Taher; Funding acquisition: Tri Hening Rahayatri; Supervision: Aryono Hendarto, Hanifah Oswari, Zakiudin Munasir, Rianto Setiabudy, Akmal Taher.

Conflicts of interest

There is no conflict of interest nor competing interest reported by the authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Enago (www.enago.com) for the English language review.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Research Technology and Higher Education (NKB-180/UN2.RST/HKP.05.00/2020).

Clinical trials registration

Consent to participate

A written informed consent was obtained from every legal guardian of the research participant.

Consent for publication

A written informed consent of publication without disclosing personal information was obtained from every legal guardian of the research participant.

Availability of data and material

Digital raw data and materials are available from the corresponding author upon request, should they be required to be reviewed.

References

- 1.Dale D.C., Crawford J., Klippel Z., et al. A systematic literature review of the efficacy, effectiveness, and safety of filgrastim. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26:7–20. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3854-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang L., Baser O., Kutikova L., et al. The impact of primary prophylaxis with granulocyte colony-stimulating factors on febrile neutropenia during chemotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:3131–3140. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2686-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jindal A., Jagdish R.K., Kumar A. Hepatic regeneration in cirrhosis. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hepatology. 2022;12:603–616. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2021.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verma N., Kaur A., Sharma R., et al. Outcomes after multiple courses of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and growth hormone in decompensated cirrhosis: a randomized trial. Hepatology. 2018;68:1559–1573. doi: 10.1002/hep.29763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chavez-Tapia N.C., Mendiola-Pastrana I., Ornelas-Arroyo V.J., et al. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor for acute-on-chronic liver failure: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Hepatol. 2015;14:631–641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simonetto D.A., Shah V.H., Kamath P.S. Improving survival in ACLF: growing evidence for use of G-CSF. Hepatol Int. 2017;11:473–475. doi: 10.1007/s12072-017-9834-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duan X.Z., Liu F.F., Tong J.J., et al. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor therapy improves survival in patients with hepatitis B virus-associated acute-on-chronic liver failure. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:1104–1110. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i7.1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albillos A., Lario M., Alvarez-Mon M. Cirrhosis-associated immune dysfunction: distinctive features and clinical relevance. J Hepatol. 2014;61:1385–1396. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rahayatri T.H., Harahap A., Hendarto A., et al. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor therapy as a bridging treatment for pediatric decompensated liver cirrhosis prior to liver transplantation: an open-label randomized clinical trial. Bali Med J. 2022;11:1250–1258. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oswari H., Rahayatri T.H., Soedibyo S. Pediatric living donor liver transplant in Indonesia's national referral hospital. Transplantation. 2020;104:1305–1307. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000003154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Irvine K.M., Ratnasekera I., Powell E.E., et al. Causes and consequences of innate immune dysfunction in cirrhosis. Front Immunol. 2019;10:293. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Premkumar M., Anand A.C. Overview of complications in cirrhosis. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2022;12:1150–1174. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2022.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mannaa F.A., Abdel-Wahhab K.G. Physiological potential of cytokines and liver damages. Hepatoma Research. 2016;2 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dirchwolf M., Podhorzer A., Marino M., et al. Immune dysfunction in cirrhosis: distinct cytokines phenotypes according to cirrhosis severity. Cytokine. 2016;77:14–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilasco M.I.A., Uribe-Cruz C., Santetti D., et al. IL-6, TNF-alpha, IL-10, and nutritional status in pediatric patients with biliary atresia. J Pediatr. 2017;93:517–524. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2016.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernsmeier C., van der Merwe S., Périanin A. Innate immune cells in cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2020;73:186–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lange C.M., Moreau R. Immunodysfunction in acute-on-chronic liver failure. Visc Med. 2018;34:276–282. doi: 10.1159/000488690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piscaglia A.C., Shupe T.D., Oh S.H., et al. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor promotes liver repair and induces oval cell migration and proliferation in rats. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:619–631. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yannaki E., Athanasiou E., Xagorari A., et al. G-CSF-primed hematopoietic stem cells or G-CSF per se accelerate recovery and improve survival after liver injury, predominantly by promoting endogenous repair programs. Exp Hematol. 2005;33:108–119. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma S., Lal S.B., Sachdeva M., et al. Role of granulocyte colony stimulating factor on the short-term outcome of children with acute on chronic liver failure. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2020;10:201–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2019.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baig M., Walayat S., Dhillon S., et al. Efficacy of granulocyte colony stimulating factor in severe alcoholic hepatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cureus. 2020;12 doi: 10.7759/cureus.10474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Philips C.A., Augustine P., Rajesh S., et al. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor use in decompensated cirrhosis: lack of survival benefit. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2020;10:124–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2019.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spahr L., Lambert J.F., Rubbia-Brandt L., et al. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor induces proliferation of hepatic progenitors in alcoholic steatohepatitis: a randomized trial. Hepatology. 2008;48:221–229. doi: 10.1002/hep.22317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lambertini M., Del Mastro L., Bellodi A., et al. The five "Ws” for bone pain due to the administration of granulocyte-colony stimulating factors (G-CSFs) Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2014;89:112–128. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rathi S., Hussaini T., Yoshida E.M. Granulocyte colony stimulating factor: a potential therapeutic rescue in severe alcoholic hepatitis and decompensated cirrhosis. Ann Hepatol. 2020;20 doi: 10.1016/j.aohep.2020.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sveikata A., Gumbrevicius G., Sestakauskas K., et al. Comparison of the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of two recombinant granulocyte colony-stimulating factor formulations after single subcutaneous administration to healthy volunteers. Medicina (Kaunas) 2014;50:144–149. doi: 10.1016/j.medici.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Digital raw data and materials are available from the corresponding author upon request, should they be required to be reviewed.