Summary

Background

Traditionally, infectious diarrhoea has been the major cause of lower GI symptoms across the developing world. Increasing urbanization has been implicated for the rising IBD cases despite very limited data in the rural setting. We aimed to assess the relative proportion of IBD and other intestinal diseases among symptomatic patients from rural and urban India.

Methods

Patients with lower GI symptoms attending urban out-patient clinics and/or specially conducted mobile rural health camps were evaluated using basic laboratory parameters, abdominal ultrasound and colonoscopy. Data including patient demographics, symptom profile, rural/urban residence and final diagnosis were analyzed. Current data was compared with previous rural survey in 2006.

Findings

Of 32,021 patients investigated, 30,835 with complete dataset [67% male; 21% (6362) rural median 44 years:6–78 years] were included. Predominant symptoms were chronic abdominal pain (55%), change in bowel habit (45%), rectal bleeding (16%), chronic diarrhoea (13%), un-intended weight loss (9%) and anaemia (3%). Final diagnoses included IBD: (1687; 5.4%; 2.2% ulcerative colitis (UC), 3.2% Crohn’s disease, CD), intestinal tuberculosis (364; 1.2%), infective colitis (1427; 4.6%), colorectal cancer (488; 1.6%) and polyps (2372; 7.7%). Proportions of UC (2.1% rural, 2.3% urban, p = 0.66) and CD (3.5% rural, 3.1%,urban, p = 0.12) were similar in both groups. There was no rural-urban divide in the relative proportion of other intestinal diseases.

Interpretation

IBD accounts for more than 5% of patients presenting with lower GI symptoms, a rate that is higher than that of infectious colitis. The proportion of IBD cases was not different between the rural and urban populations. These data appear to indicate the changing disease prevalence patterns in India that require further research.

Funding

The study was funded by Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust.

Keywords: Inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn’s disease, Ulcerative colitis, India, Colonoscopy

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

The increasing incidence and prevalence of IBD in the Asia-Pacific region including India over the last two decades is well documented. 70% of the Indian population stay in the villages. We searched the “Pubmed” from 1965 to 2022 using the keywords (epidemiology) and (inflammatory bowel disease) and (India) and (rural). We found very limited data on the prevalence of IBD in rural population. Study in 1990 in more than 0.4 million population showed only 74 case of IBD with high prevalence of infectious diarrhoeas.

Added value of this study

This is the first study to compare the relative proportion of IBD in rural and urban India based on a large community colonoscopic evaluation of more than 30,000 symptomatic patients. IBD accounted for more than 5% of patients presenting with lower GI symptoms, a rate that was higher than that of infectious diarrhoeas. The relative proportion of IBD cases was not different between the rural and urban populations.

Implications of all the available evidence

The results indicate a declining infectious diarrhoeas and increasing relative prevalence of IBD over the last few decades. With increasing IBD in the rural populations, the healthcare infrastructure and screening programs may need to be modified to ensure early diagnosis. The possible etiology of this increasing incidence including environmental risk factors requires further evaluation and research.

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) was traditionally a disease of the western world. The rapid increase of IBD in the incidence and prevalence of IBD in the newly industrialized nations of Asia over the last two decades has been attributed to environmental factors including the increased adoption of westernized lifestyles.1, 2, 3 For the same reason, IBD has always been considered a disease of the urban environment.4

Rural India constitutes nearly 70% of the Indian population. In India, with improving socio-economic conditions, changing dietary practices and lifestyle even in the villages, it might be expected that there would be an increase in rural IBD.5 However, the prevalence of IBD in rural India has not been evaluated.

We conducted a large screening program for IBD amongst all symptomatic patients attending the hospital as well as specially conducted rural camps. These services were available free of cost to patients living below the poverty line and those who did not have medical insurance. The rural outreach program included a marketing campaign to raise awareness and on site medical camps to increase recruitment of potential patients.

The primary aim of this initiative was to understand a) the relative proportion of CD and IBD compared to other colonic diseases in the symptomatic population, b) any rural-urban divide in the relative proportion of IBD in symptomatic patients. We also wanted to compare the current data with our previous rural survey done more than a decade ago (2006).6

Methods

Study settings and defining the study population

The study was conducted by the IBD Center of the Asian Institute of Gastroenterology (AIG), located in Hyderabad, India. AIG is one of the largest centres for Gastrointestinal diseases in Asia, with more than 150,000 registrations and 60,000 endoscopic procedures performed annually. This IBD diagnostic project to facilitate the early diagnosis of Crohn’s disease was initiated in March 2020 was supported by the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust, New York, USA to increase diagnostic awareness of Crohn’s in low resource countries.

The study population was subdivided into rural and urban, based on the Government of India census guidelines (https://censusindia.gov.in/2011census/Listofvillagesandtowns.aspx), irrespective of where clinical assessment or procedures were performed. Accordingly, we considered urban areas as having a population of more than 5000 with a density of not less than 400 persons per square kilometer. Urban areas were further categorized into “towns” (with fewer than 100,000 population), and “cities” (with greater than 100,000 population).7 Metropolitan cities were those with a population of 1 million and above. All areas other than urban were referred as rural, with villages as the basic unit. The residence status of individual patients over the last 5 years was considered. More recent migrants were excluded from the analysis.

The IBD diagnostic programme

Project work flow

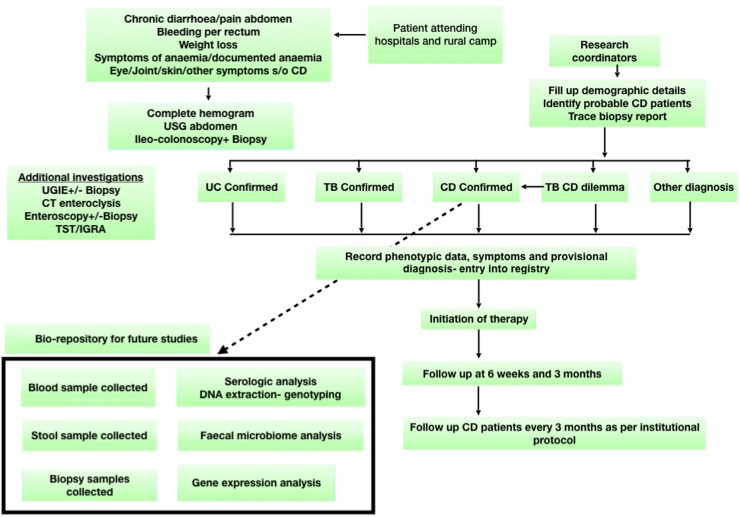

Patients with symptoms of diarrhoea, rectal bleeding, abdominal pain and/or weight loss were enrolled into the programme after informed consent regarding the diagnostic services and data collection, including a separate consent for colonoscopy requiring sedation (Fig. 1). Consent for minor (<18 years) was taken from the guardian. The institutional ethics committee (AIG/lEC38/06.2020-01) approved the study. Patients with a BPL (Below Poverty Line) card and patients without medical insurance underwent all investigations including diagnostic colonoscopy and relevant histopathology free of charge.

Fig. 1.

Colonoscopic screening project workflow. CD-Crohn’s disease, CT-computed tomography, DNA-Deoxyribonucleic acid, IGRA-interferon gamma release assay, TST-tuberculin skin test, TB-tuberculosis, USG-ultrasound, UGIE-upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, UC-ulcerative colitis.

A brief clinical consultation was followed by a check on basic laboratory parameters (full blood count, liver function tests and creatinine, faecal calprotectin), and an abdominal ultrasound. Colonoscopy was arranged after clinical exclusion of intestinal obstruction and after fitness assessment for sedation. Most procedures in hospital settings were performed under propofol sedation. Onsite rural health camp procedures were performed without sedation after standard preparation of 2 L of polyethylene glycol. Elderly (>60 years), pediatric including sicker patients were referred to the hospital for the procedure. The preference was also given to other patients who preferred procedure under sedation. Patients with poor or inadequate preparation were offered a repeat colonoscopy on the subsequent day after adequate preparation.

Patients with suspected isolated small bowel Crohn’s disease on ultrasound or suggestive symptoms and an elevated faecal calprotectin, underwent computed tomography enterography (CTE) or magnetic resonance enterography (MRE) followed by single balloon enteroscopy (SBE) or novel motorized spiral enteroscopy (NMSE) available at the hospital. These were performed free of charge for the BPL and uninsured patients.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Symptomatic patients between the ages of 6–80 years were considered for colonoscopy. The study population included symptomatic patients presenting with chronic diarrhoea (≥3 bowel movements daily for ≥4 weeks duration), bloody diarrhoea (of any duration), rectal bleeding, chronic abdominal pain (≥3 months), recent change in bowel habit, unintentional weight loss (≥5% of usual body weight in the last 3 months), or anaemia (haemoglobin <100 g/L). Patients with a prior diagnosis of IBD, history of intestinal resection, or colonoscopy for any other condition, patients with intestinal obstruction, severe co-morbid illness including chronic kidney disease (CKD) or chronic liver diseases (CLD), were excluded from the study (Table 1).

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria |

|

| Exclusion criteria |

|

Recruitment of patients

Patients attending the hospital

AIG is a high volume referral center for gastrointestinal diseases across the region. All symptomatic patients attending the hospital were screened for IBD after informed consent.

Additionally, we advertised about the screening campaign at the hospital via placards and display screens so that patients visiting our hospitals could see and refer other symptomatic patients in their locality for free diagnostic screening.

The rural outreach program

We conducted GI health camps in the villages of Ranga Reddy, Sangareddy and Vikarabad districts of Telangana (Fig. 2). The local administration office (Panchayat) was contacted for logistic assistance. A daily medical camp was set up at the village panchayat office or the school premises. Diagnostic evaluation of all symptomatic patients were done with lab investigations, ultrasound and colonoscopy. A specially designed mobile endoscopy/colonoscopy van was used to conduct endoscopic procedures in the villages. The rural outreach programme team included two gastroenterologists, two physicians, one radiologist, three nursing staff, three research associates, one lab technician, two endoscopy technicians, and supporting staff (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Geographical representation of rural area covered in the colonoscopic evaluation project. The map of India is on the left showing location of Telangana and panel on right showing districts of Telangana where various villages were covered.

Fig. 3.

Rural outreach program. A. The rural outreach team en route to their destination. B. The Mobile endoscopy van. C. Patient screening in out patient basis organized in a school in one of the villages. D. Abdominal ultrasound is being performed in rural camp. E. Mobile laboratory at work in the rural camp. F. Endoscopy being performed in the mobile endoscopy van.

By way of preparation and advertising, leaflets regarding the camps were distributed in advance to the villages, highlighting the availability of free diagnostic services. A marketing campaign for the program was launched via billboards and displays in the rural districts of the region, to increase recruitment and ensure the services were available to the underprivileged.

Data collection and follow up

Demographic, phenotypic data and symptoms were collected digitally on a data management software (Google form, Google, India) or on paper format for villages with no internet access. Colonoscopy findings including the histopathology and the provisional diagnoses were recorded. All data were entered into excel by research associates on a daily basis. Provisional diagnoses based on clinical features, laboratory results, abdominal US and colonoscopy. Additional investigations including fecal calprotectin, CTE, endoscopy or enteroscopy were performed as clinically indicated for suspected small bowel CD. The histopathological diagnosis of CD was considered confirmed if any two of 3 histological features (chronic inflammation, discontinuous inflammation, architectural distortion), or non-caseating micro-granulomas were present, as defined by a specialist pathologist [AS]. In cases of doubt a second specialist pathologist reviewed the specimens. Intestinal tuberculosis (ITB) was excluded by considering any history of exposure, careful examination for extra-intestinal manifestations, together with colonoscopic, radiologic, histopathologic and other relevant findings. A diagnosis of ‘ITB/CD’ was made for patients in whom a confirmed diagnosis was not possible despite investigation. All newly diagnosed CD, probable CD and ITB/CD were followed up for at least 6 months to allow a diagnosis to be adjusted or confirmed by response to treatment.

Ulcerative colitis was diagnosed based on symptoms, colonoscopic picture and histologic evidence of chronic inflammation with or without architectural distortion. Additional biopsy specimens of patients with suspected IBD based on colonoscopy findings were collected from ileum, cecum and rectum and preserved at −80 °C soon after endoscopy for future research. Blood and faecal samples of all patients where the colonoscopist strongly suspected IBD were stored in the bio-repository at −80 °C. Faecal sample DNA was extracted using the DNA Isolation Kit for storage. Blood samples included whole blood EDTA, serum and heparinized plasma, to enable future genetic, proteomic, serological, and metabolomic analysis.

A registry for the diagnostic project was established in an excel read sheet maintained by research associates (AK, SM, YA, SK) including demographics, phenotype, results of diagnostic tests and histopathology. Treatment of newly diagnosed patients with IBD was initiated according to European Crohn’s Colitis Organisation (ECCO) guidelines and a follow up visit scheduled at 6 weeks, 3 months and 6 months to enable us to confirm diagnosis based on response to treatment.8,9 All enrolled patients with IBD were subsequently followed up in the IBD center as per protocol (Fig. 1).

Statistical analysis

All data were exported to Microsoft Excel and analyzed by statistical package for social sciences (SPSS version 26, IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA). Continuous variables are expressed as median (range) or mean (standard deviation) based on normality of distribution. Normality of distribution was ascertained by Shapiro–Wilk and Kolkogorov–Smirnov tests. Categorical variables are expressed as number (n) and percentage (%). Chi-square/Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables and Mann–Whitney test was used to compare continuous variables between the two groups. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant, without correction for multiple comparisons. Uni and multi-variable logistic regression analyses examined the association of a confirmed diagnosis of CD with symptoms and demographic factors. Factors with a value p < 0.05 in the univariate analysis were included in multivariable analysis. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis derived the most accurate cut-off points for symptoms associated with CD. Number of symptoms was entered as test variable and presence of CD was considered as state variable for ROC analysis. Youden’s index was calculated to assess the association between cut-off levels and CD.

Role of funding source

None.

Results

Rural health camps

Daily rural camps with weekly mobile endoscopy and ultrasound camps were conducted from March 2020 to May 2022 covering 32 villages in rural areas of Telangana.

Basic demographics of the study population

32,021 patients were assessed between March 2020 and May 2022 (26 months). Of these, 30,835 patients had a complete dataset. Among them, 3238 colonoscopies were done in the rural camps (Supplementary Fig. S1). All these patients who were recruited from mobile camps were rural inhabitants. Among total patient population, 6362/30,835 (21%) were from rural and 24,473 (79%) from urban areas. There was an overall male predominance 20,752 male: 67%; median age 44 years: 6–78 years, range-33–56), which differed significantly between rural and urban areas (rural areas had more male predominance) (Table 2, Table 3). There was a history of appendicectomy in 861 (2.8%, 3.5% CD, 1.3% UC). Current or ex-smoking history was present in 2052 (total 6.6%, 5.2% current smoker).

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of the population.

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Number of cases | 30,835 |

| Male [n (%)] | 20,752 (67.3) |

| Rural [n (%)] | 6362 (20.6) |

| Age [median (range)] in years | 44 (6–78) |

| Educational status [n (%)] | |

| Illiterate | 946 (3) |

| Primary education | 7123 (23) |

| Secondary education | 14,181 (46) |

| Tertiary education | 8585 (28) |

| Smoking | |

| Current smoking [n (%)] | 1609 (5.2) |

| Past smoking [n (%)] | 443 (1.4) |

| History of appendectomy | 861 (2.8) |

Table 3.

Distribution of various colonoscopic findings in rural and urban subgroups undergoing colonoscopic screening.

| Rural [n (%)] | Urban [n (%)] | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total numbers | 6362 (20.6) | 24,473 (79.4) | |

| Male | 4362 (68.5) | 16,386 (66.9) | 0.01 |

| Age [median (range)] in years | 44 (8–72) | 44 (6–78) | 0.3 |

| Smoking | 452 (7) | 1600 (6.5) | 0.5 |

| Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) | 358 (5.6) | 1329 (5.4) | 0.54 |

| Crohn’s disease | 224 (3.5) | 768 (3.1) | 0.12 |

| Ulcerative colitis/IBD-unclassified | 134 (2.1) | 561 (2.3) | 0.37 |

| Intestinal tuberculosis | 73 (1.1) | 291 (1.2) | 0.78 |

| Infective ileitis/colitis (including parasitic and protozoal infections) | 279 (4.4) | 1148 (4.7) | 0.3 |

| Carcinoma Colon | 108 (1.7) | 380 (1.6) | 0.41 |

| Colorectal polyps | 511 (8) | 1861 (7.6) | 0.25 |

| Diverticulosis | 91 (1.4) | 565 (2.3) | 0.0001 |

Indications of colonoscopy

More than one symptom could present in individual patients. Chronic diarrhoea in 4039/30,835 (13%), rectal bleeding in 5026 (16%), chronic abdominal pain 16,928 (55%), change in bowel habit 13,906 (45%), un-intentional weight loss in 2898 (9%) and anaemia in 894 (3%). Median duration of symptoms was 5 months (IQR: 2–12 months). The cecal intubation rate was 92.3% (78.5% in un-sedated compared to 93.4% in sedated colonoscopy).

Diagnostic profile of symptomatic patients

IBD was diagnosed in 1680/30,835 patients (5.4%) of which 992 (3.2%) were CD and 688 (2.2%) were UC. The ratio of CD to UC was 1.44:1. IBD-Unclassified (IBD-U) was present in only seven patients. Intestinal tuberculosis (ITB) was diagnosed in 364/30,835 (1.2%) and other infective ileocolitis indicated on biopsy in 4.6% (1427/30,835) patients, although no specific organisms could be identified in the majority. Colorectal cancer was diagnosed in 488/30,835 (1.6%) (Table 3) and polyps in 2372/30,835 patients (7.7%). Other findings included diverticulosis 565 (2%), haemorrhoids 965 (3%), anal fissures 479 (2%), angioectasia 103 (0.3%), non-specific ileitis/colitis 1085 (4%) and solitary rectal ulcer/mucosal prolapse in 356 (1.2%). Rest of the colonoscopies ere normal.

Symptom profile of patients with IBD cohort

CD symptom distribution

Abdominal pain was the most common symptom in patients with CD 694/992, 70%), chronic diarrhoea in 303/992 (31%), change in bowel habit in 327/992 (33%), rectal bleeding in 188/992 (19%) and anaemia 87/992 (9%) (Supplementary Table S1). The location of CD at diagnosis was ileal (248/992, 25%), colonic (258/992, 26%), ileocolonic (446/992, 45%) and upper GI (60/992, 6%). Isolated small bowel CD was seen in 11% (109/992). Perianal disease was seen in 9% (89/992). Stricturing and/or fistulizing CD was seen in 29% cases (288/992) and rest 71% (704/992) were inflammatory.

UC symptom distribution

Among patients with UC, bloody diarrhoea was the most common symptom and was present in 659/688 (96%). Abdominal pain and unintentional weight loss were seen in 382/688 (56%) and 122/688 (18%) patients respectively. Anaemia (<100 g/L) was present in 29/688 (4%) cases (Supplementary Table S1). The distribution of UC based on extent were: proctitis (172/688, 25%) left-sided colitis (289/688, 42%) and extensive colitis (227/688, 33%).

Pre-colonoscopy prediction of Crohn’s disease based on symptom profile

The symptom profile of patients with a normal colonoscopy was compared to patients with a definitive diagnosis of CD. All symptoms except a recent change in bowel habit were significantly more common in patients with CD. Diarrhoea, weight loss and anaemia had the highest odds of having CD whereas abdominal pain and rectal bleeding had lower odds. The highest odds ratio for single symptoms was 4.36 (95% CI 3.43–5.5, anaemia), but for two symptoms it increased up to 13.23 (95% CI 8.75–20.01, anaemia and weight loss) and when a patient had 4 or all 5 symptoms, the OR was approximately 30 (Supplementary Table S2).

On logistic regression analysis, symptoms like weight loss, diarrhoea, anemia, abdominal pain and anemia were significantly associated with having CD with highest odds for anemia followed by weight loss and diarrhoea on multi-variable analysis (Table 4).

Table 4.

Items independently associated with Crohn’s disease diagnosis derived from logistic regression with backward selection using the likelihood ratio test.

| P value | OR | 95% C.I. |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Univariate analysis | ||||

| Abdominal pain | <0.0001 | 2.139 | 1.822 | 2.512 |

| Diarrhoea | <0.0001 | 2.583 | 2.176 | 3.067 |

| Weight loss | <0.0001 | 3.595 | 3.023 | 4.276 |

| Anemia | <0.0001 | 4.452 | 3.303 | 6.001 |

| Blood in motions | <0.0001 | 1.576 | 1.288 | 1.928 |

| Altered bowel habits | 0.943 | 1.006 | 0.846 | 1.197 |

| Smoking | 0.822 | 1.066 | 0.611 | 1.858 |

| Appendectomy | 0.657 | 1.088 | 0.750 | 1.578 |

| Multi-variable analysis | ||||

| Abdominal pain | <0.0001 | 2.137 | 1.821 | 2.507 |

| Diarrhoea | <0.0001 | 2.588 | 2.181 | 3.072 |

| Weight loss | <0.0001 | 3.594 | 3.022 | 4.273 |

| Anemia | <0.0001 | 4.443 | 3.296 | 5.988 |

| Blood in motions | <0.0001 | 1.573 | 1.285 | 1.924 |

In the ROC analysis, subjects having ≥2 symptoms were significantly more likely to have CD (AUC:0.691, 95% CI 0.673–0.710, p < 0.0001). Sensitivity and specificity for a diagnosis of CD with two symptoms were 45% and 85% respectively (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Rural-urban distribution

The proportions of patients with CD (3.5% rural and 3.1% urban, p = 0.12) were no different in rural and urban populations. The same applied to UC/IBD-U (2.1% rural vs 2.3% urban, p = 0.66), Infective ileitis/colitis (rural 4.4% vs urban 4.7%, p = 0.3) and intestinal TB (rural 1.1% vs urban 1.2%, p = 0.78) were also no different. There was also no difference in the proportion of patients with colorectal polyps (8.0% rural vs 7.6% urban, p = 0.63) or carcinoma (1.7% rural and 1.6% urban, p = 0.41), although. The proportion of patients with diverticulosis was lower in the rural population (1.4%) than the urban population (2.3% (p = 0.0001).

Comparative analysis with rural health care project (2006)

By way of comparison, in 2006 the AIG conducted a rural GI health survey covering 4837 villages in Andra Pradesh/Telangana states with a population of over 10 million people.6 Colonoscopy was performed in a total 1540 patients, but only 2 cases of IBD were diagnosed (Table 5). The rural population in our study (2020–2022) showed a significantly higher proportion of patients with IBD (p < 0.001). The number in infectious ileitis/colitis (amoebic and tubercular) were significantly lower.

Table 5.

Comparison of colonoscopic diagnoses in the current study with the Asian Institute of Gastroenterology (AIG) rural gastrointestinal health survey performed in 2006.

| Village (2006) | Village (2020–2022) | p | Odds ratio | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of procedures | 1540 | 6362 | |||

| IBD | 2 (0.1%) | 358 (5.6%) | <0.0001 | 45.9 | 11.4–184.3 |

| Intestinal tuberculosis | 29 (1.9%) | 73 (1.1%) | 0.03 | 0.6 | 0.4–0.9 |

| Amoebic colitis | 31 (2.3%) | 8 (0.1%) | <0.001 | 0.06 | 0.3–0.13 |

| Polyps | 28 (1.8%) | 511 (8.0%) | <0.0001 | 4.7 | 3.2–6.9 |

Discussion

This study aimed to assess the relative proportion of IBD including Crohn’s disease (CD) and other intestinal diseases in symptomatic patients undergoing colonoscopy from rural and urban India. We performed more than thirty thousand colonoscopies over 2 years for all symptomatic patients with chronic abdominal pain (≥3 months), chronic diarrhoea (>4 weeks), rectal bleeding, a change in bowel habit, unexplained weight loss (>5% in 3 months), or anaemia (<100 g/L). We made a definitive diagnosis of IBD in 5.4% out of 30,835 patients. CD (3.2%) was more common than ulcerative colitis (2.2%, ratio CD:UC 1.44:1). There was no significant differences for a diagnosis of CD or UC between rural and urban populations. This potential significance of this analysis should not be over-interpreted, but the lack of population-based registries in this part of the world put it into context. We found the relative proportion of CD to be similar to infectious diseases including ITB, consistent with a rising trend of IBD in a region where infectious diseases have traditionally predominated.5 These results from 2020 to 22 can be contrasted with the original rural outreach programme conducted by AIG in 2006, when only 2 cases of IBD were identified in 1540 colonoscopies performed in rural population.

These results illustrate the pace of change in the occurrence of CD and IBD as a whole. The last two decades have seen an increasing incidence and prevalence of IBD in the Asia-Pacific region.3 Asian countries including Japan and Korea, which experienced rapid industrialization after World war II, have reported a rising prevalence.10,11 India appears to be in an acceleration phase, with a rapidly increasing incidence but still with a low prevalence. When countries such as India and China, each with a population of more than 1 billion people, experience such an increase in chronic inflammatory gut diseases, then the total number of patients affected is likely to exceed those in the West over the next decade.12 This has significant implications for healthcare policy and expenditure in the region.

If a chronic inflammatory gut disease such as IBD is a feature of industrialization, then living in an urban environment is likely to increase the risk of developing CD.13,14 There has been speculation that migration of the population from rural areas to cities is responsible for the increasing incidence of IBD in Asia.15 Data from rural populations has, however, been lacking. This study, which investigated 6362 patients with defined symptoms, who had lived in rural villages for at least 5 years, found no difference in the relative proportion of IBD compared to 24,473 patients from urban areas. CD was more prevalent than ulcerative colitis even in rural India.3 The differences in diagnoses in 2022 and an earlier (2006) study from our institute are stark.6 Infectious diseases are less common, while the relative proportion of IBD has changed from 0.1% to >5% (Table 5).

Urbanization may, of course, have reached the villages with changing environments, dietary practices (fast food outlets are often blamed) and availability of processed foods, together with easier access to diagnostic services. Our rural health camps were designed to provide diagnostic services at the doorstep, with colonoscopy performed in the specially designed mobile van (Fig. 3).

There are otherwise few data on GI disorders in the rural Indian population. A survey of GI disorders among nearly 0.4 million patients attending mission hospitals in rural India in 1990, reported that most presented with bloody diarrhoea (n = 12,272) followed by amoebiasis (n = 7310), enteric fever (2,113), or intestinal tuberculosis (n = 872). Inflammatory bowel disease (n = 74) was the least common, but UC was 3 times more common than CD. Our study shows a reversal of this diagnostic profile, with CD now being more common than UC even in rural India.16 Our 2006 colonoscopy-based study indicates that this does not simply represent access to diagnostic services.6 Although these data are not comparable to the current study, we used the data for comparison as the principle behind the health camps (to provide access to specialist care and endoscopy in rural India) was the same in 2006 and 2020 and there are no other comparable data available.

Nevertheless, access to colonoscopy is the key for early diagnosis of CD, IBD and all colonic disease, which is still lacking in rural areas. The ratio of gastroenterologists to the population in India is very low, with just one gastroenterologist per 5 million population.5 The AIG rural outreach programme provides diagnostic services at the doorstep to people with poor access to healthcare and has enabled us to identify IBD particularly CD emerging in the rural population of India. Nearly 90% percent of CD and almost all with UC can be diagnosed by colonoscopy and histopathology. The model of a low-cost mobile gastroenterology van enables earlier diagnosis of IBD and is transferrable to other low resource countries.17 The symptom-based model that we have adopted, where 2 or more out of 5 suggestive symptoms (Fig. 2) has a high likelihood (85% sensitivity) of diagnosing CD.

Our study was novel in that it combined an epidemiological study with a social service providing free of charge diagnostic services to the underprivileged. Bio-samples including blood, stool and tissue for genetic testing and microbiome analysis were obtained in almost 1000 newly diagnosed cases of IBD. Follow up of this cohort regarding outcomes, together with analysis of genetic, environmental and microbial factors may provide insights into the development of IBD. The missing data was less than 5%. This was possible by doing rigorous weekly meeting to track the status of patient recruitment. The colonoscopy findings and biopsy reports of preceding week were discussed every week to maintain the robust data. Although COVID-19 pandemic affected the patient recruitment to only just more than 1000 in 6 months during peak of the pandemic, later the recruitment was accelerated recruiting highest 11,540 patients in last 6 months (November–May 2022).

Limitations of this study should also be acknowledged. This was not a true population-based survey. Hence the results are neither generalizable nor conclusive, although indicative of trends. That two thirds of patients were male is likely to represent cultural factors that influence access to health care and it can be hoped that continued provision of the outreach programme will overcome such barriers. Consequently selection bias cannot be excluded. To overcome these challenges, we are currently conducting a large house-to-house survey in a well-defined district on the outskirts of Hyderabad in rural Telangana, to extract population-based data on the incidence and prevalence of CD and UC.

IBD is today a global disease that is accelerating in emerging nations. If industrialization is the catalyst, then the environmental precipitants of IBD have already (2022) reached rural communities. Rural healthcare policies should include liberal detection strategies for early diagnosis and management of CD and other inflammatory bowel disease. These data highlight the need for research into the factors driving the development of CD. Low resource countries need to develop innovations in health-care to manage this complex, lifelong disease, since Western models of care are unlikely to be transferrable.

Contributors

Concept and design: RB,PL; Administrative support: RB, DNR; Provision of study material/patients: RB, PL; Collection or assembly of data: AK, SM, YA, SK; Performing colonoscopy: RP, SG, PP, RB; Colonoscopic screening data collection: NP, SJ, SK; Data Analysis and interpretation: PL, RB; Rural outreach program: AK, AG, DM; Critical review: ST; Manuscript writing: All authors; Approval of final manuscript: All authors.

Editor note

The Lancet Group takes a neutral position with respect to territorial claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Declaration of interests

None of the authors has a conflict of interest related to this paper.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to all the members of Rural Outreach program, GI fellows, radiologists and the support staffs who helped in the hospital based colonoscopic evaluation program in the project.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lansea.2023.100259.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary Fig. S1.

Supplementary Fig. S2.

References

- 1.Ouyang Q., Tandon R., Goh K.L., Ooi C.J., Ogata H., Fiocchi C. The emergence of inflammatory bowel disease in the Asian Pacific region. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2005;21(4):408–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ng S.C., Shi H.Y., Hamidi N., et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st Century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet. 2017;390(10114):2769–2778. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32448-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaplan G.G., Windsor J.W. The four epidemiological stages in the global evolution of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18(1):56–66. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-00360-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soon I.S., Molodecky N.A., Rabi D.M., Ghali W.A., Barkema H.W., Kaplan G.G. The relationship between urban environment and the inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:51. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-12-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banerjee R., Pal P., Mak J.W.Y., Ng S.C. Challenges in the diagnosis and management of inflammatory bowel disease in resource-limited settings in Asia. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(12):1076–1088. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30299-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Talukdar R., Reddy D.N. Making endoscopy mobile: a novel initiative for public healthcare. Endoscopy. 2012;44(2):186–189. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1291612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Onda K., Sinha P., Gaughan A.E., Stevens F.R., Kaza N. Missing millions: undercounting urbanization in India. Popul Environ. 2019;41(2):126–150. doi: 10.1007/s11111-019-00329-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Torres J., Bonovas S., Doherty G., et al. ECCO guidelines on therapeutics in Crohn's disease: medical treatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14(1):4–22. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raine T., Bonovas S., Burisch J., et al. ECCO guidelines on therapeutics in ulcerative colitis: medical treatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2022;16(1):2–17. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwak M.S., Cha J.M., Lee H.H., et al. Emerging trends of inflammatory bowel disease in South Korea: a nationwide population-based study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;34(6):1018–1026. doi: 10.1111/jgh.14542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murakami Y., Nishiwaki Y., Oba M.S., et al. Estimated prevalence of ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease in Japan in 2014: an analysis of a Nationwide Survey. J Gastroenterol. 2019;54(12):1070–1077. doi: 10.1007/s00535-019-01603-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kedia S., Ahuja V. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in India: the great shift east. Inflamm Intest Dis. 2017;2(2):102–115. doi: 10.1159/000465522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ng S.C., Kaplan G.G., Tang W., et al. Population density and risk of inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective population-based study in 13 countries or regions in asia-pacific. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(1):107–115. doi: 10.1038/s41395-018-0233-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rajbhandari R., Blakemore S., Gupta N., et al. Crohn's disease among the poorest billion: burden of Crohn's disease in low- and lower-middle-income countries. Dig Dis Sci. 2022;68(4):1226–1236. doi: 10.1007/s10620-022-07675-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benchimol E.I., Kaplan G.G., Otley A.R., et al. Rural and urban residence during early life is associated with risk of inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based inception and birth cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(9):1412–1422. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Probert C.S., Mayberry J.F., Mann R. Inflammatory bowel disease in the rural Indian subcontinent: a survey of patients attending mission hospitals. Digestion. 1990;47(1):42–46. doi: 10.1159/000200475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Banerjee R., Pal P., Girish B.G., Reddy D.N. Risk factors for diagnostic delay in Crohn's disease and their impact on long-term complications: how do they differ in a tuberculosis endemic region? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47(10):1367–1374. doi: 10.1111/apt.14617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.